|

Bill Hume

and Babysan

Unknown

and, Until Now, Unheralded

When Bill

Hume died at 93 on June 27, 2009, the lead paragraph in the obit published in

his hometown newspaper, the Columbia Daily Tribune, rolled out a list of

his many talents—sculptor, artist, actor, playwright, magician, ventriloquist,

author, clown, newspaper man, husband and father, photographer, animator, TV

and film producer, corporate art director and cartoonist.

When

I first came across Hume, all I knew was that he was a cartoonist who had drawn

a book of cartoons about Babysan, a toothsome young Japanese woman who

entertained U.S. occupation troops in the early 1950s. I’d found the book, a

tidy 5x7-inch paperback, in a used book shop on Fifteenth Street in downtown

Denver in 1954. The book was, then, not used. It was brand new, just published

in May.

It

would be a year before I first encountered Playboy (the August 1955

issue covered by a mermaid barely attired in strategically arranged

seaweed)—just 18 months into its run—but my adolescent hormones were already

sufficiently alert that I could scarcely ignore the cover of Hume’s book,

which, under the title Babysan’s World: The Hume-n Slant on Japan,

depicted one of the curvaceous gender with a Bettie Page hair-do, thrusting her

chest out at two servicemen, each offering her a cigarette.  She was fully clothed, reflecting the mores of the time, not yet battered

into accepting vast stretches of naked female epidermis on the covers of

general circulation books and magazines. But she was irresistibly cute,

standing there, modestly attired in long-sleeved sweater and calf-length skirt. She was fully clothed, reflecting the mores of the time, not yet battered

into accepting vast stretches of naked female epidermis on the covers of

general circulation books and magazines. But she was irresistibly cute,

standing there, modestly attired in long-sleeved sweater and calf-length skirt.

Standing

in the shop, I thumbed the book’s pages quickly and saw an unusual interior:

every right-hand page was a cartoon, and on every facing page was illustrated

text explaining some aspect of Japanese life, custom or lingo that seemed to

have inspired the cartoon. The drawings displayed delectable brushwork—a

supple, undulating line that waxed thick and waned thin, modeling volume with

every stroke’s variation.

And Hume

deployed an impressive array of techniques: he achieved tonal values sometimes

with Zip-a-tone, sometimes with Craftint duotone (a chemically treated paper

that could produce two tones of gray); some of the cartoons and many of the

illustrations on the facing pages were drawn and delicately shaded with pencil.

A bravura performance throughout the book’s 128 pages.

On

the back cover was this (quoted here in italics):

Babysan’s

back! This time she brings with her the artist who created not only her but

also the other lovable gals and guys who helped make Babysan a real Far East

bestseller. This Hume’n Slant on Japan explains a lot about Babysan and

her world. ... This volume is really more than a hilarious cartoon book—though

it’s that, too! It is an artist’s eye view of Japan and its everyday culture.

...

That’s

all I knew about Bill Hume until several years ago when I acquired a second

book of Hume’s Babysan cartoons—Babysan: A Private Look at the Japanese

Occupation—which explained the character a little more.

In

1945, in the early days of the Occupation of Japan, it was a common sight to

see American servicemen giving candy to some little boy or girl they encountered

toddling along the street. Most of the Japanese kids were shy and this friendly

gesture helped win the youngsters over to the side of the Americans. As the

years passed, those kids, naturally, grew up. The little boy grew up to be a

boy-san, and the little girl grew up to be—like Babysan.

The

name Babysan reveals the blend of cultures that distinguishes the cartoons.

"San" may be assumed to mean "mister," "missus,"

"master," or "miss." "Babysan," then, can be

translated to mean "Miss Baby," an expression that combines the

Japanese compulsion for politeness with the American GI's passion for

informality. Instead of greeting a girl with, "Hey, baby," the

servicemen added a respectful "san." It took them quickly beyond the

introductions.

Created

as a local pin-up to help boost the morale of servicemen in Japan, the Babysan

cartoons made their first bid for fame on the Navy aircraft hanger’s

bulletinboard at Oppama. From the bulletinboard to a weekly feature in the

pages of the Far East edition of the Navy

Times, Babysan scored an immediate hit. Her graceful lack of sophistication,

her frank sayings—”If I not here tomorrow, I out with other boyfriend”—made

for surefire cartoon entertainment.

A

carefree and utterly charming girl, Babysan never forgot the Americans’ acts of

kindness she’d enjoyed as a child. She decided, in fact, to devote herself to

the cause of the American serviceman in Japan. She would make his stay in the

land of the cherry blossoms a pleasant one, and—well, the way she figured

it—the more GIs the merrier. There wasn’t much sense in restricting her charms

to one.

The

format of this volume—which, I discovered, had been published the year before

the other one—was the same: a page of explanatory text facing a cartoon about

the aspect of Japanese culture that was explained in the prose. No

illustrations this time, just the text.

By

the time the second Babysan book arrived on my desk, I knew enough comics

history to wonder why I’d never run across Bill Hume’s name or work anywhere

else. Except for these two small volumes, Bill Hume seemed never to have

existed.

And

that was, to a chronicler of the medium like me, alarming. Judging from the two

books, Hume was as active as a cartoonist-in-uniform as, say, George Baker or

Dave Breger had been during World War II. And he evidently specialized in

pretty girls. Given all the press attention that was showered on Baker and

Breger not to mention Bill Mauldin and, especially, Milton Caniff with Miss

Lace in Male Call, it was baffling to me that Hume had evaded attention

so thoroughly. Maybe, I thought, he was better known on the West Coast. Dunno.

Admittedly,

the "Occupation" referred to here was not a world-wide phenomenon

like World War II. It was confined to the American military occupation of Japan

that took place after World War II. The corn-cob pipe smoking General Douglas

MacArthur ran the Occupation. A virtual dictator, MacArthur supervised the

recovery of the Japanese society, its conversion to peace-time economy, and the

establishment of the present form of democratic government in Japan. For the

period of the Occupation, American soldiers and sailors were plentiful

residents of the Japanese islands.

One

of the sailors, Bill Hume, drew cartoons about the adventures of servicemen in

this unfamiliar culture—concentrating mostly on their relationships with the

feminine outcropping of the population. Babysan probably didn’t get around as

much as Caniff’s Miss Lace or Mauldin’s Willie and Joe, but in occupying the

GIs while they were occupying her country, she was obviously popular enough to

make it into two book collections.

So

why hadn’t Bill Hume and/or Babysan showed up anywhere in the chronicles of

cartooning? It was a mystery, exactly of the sort to pique my interest.

The

second of the two books had press releases from the publisher stuffed into the

pages. From these, I learned all that I would know about Bill Hume for several

ensuing years. Here, in italics, by way of elucidation, are some pertinent

paragraphs from one of the press releases.

Like

the famed cherry blossoms that come with the Japanese springtime, Babysan came

with the Occupation. Babysan is the heroine of Hume's Oriental flavored brush

and ink sketches and humorous commentary on the mutual problems of the Japanese

and American peoples in their first chance to become intimate since the days of

Admiral Perry.

By

September 1951, when Navy Reservist Bill Hume arrived in Japan, having been

recalled to serve with Fleet Aircraft Squadron 120, the infant baby-sans of

1945 had grown up to become fascinating, fun-loving Japanese girls, influenced

by American customs and trying their best to become Westernized. From his

observation of such incongruous antics as Japanese jitterbugging, American as

apple pie, yet Oriental as a rice paddy, a new personality was born—Babysan.

And from the brush of the talented sailor, life fairly burst into the

personality.

Babysan

speaks an international language—broken American and chopped Japanese—and

quickly learns the expressions of American servicemen in the Far East. She

often bewilders her new boyfriend by her dubious command of the English

language. He can't help thinking that there is another American love in her

life—someone who teaches her a Yankee word or two. Babysan assures him that

such a thing could, to coin a phrase, never hoppen.

Americans,

too, learn a new language. Almost immediately, they learn words like

"sayonara," which means "goodbye"; "sukoshi,"

which means "little"; "takusan," which means

"much"; and "stinko," which means the same in any

language.

The

antics of the fun-loving Babysan, many of which are recorded on the pages of

the book Babysan, are fast becoming a well-loved legend in the history of the GI Dynasty in

Japan—sometimes called the American Occupation.

Here

we see in bold comic relief the Japanese impact on the bewildered and

enthusiastically curious young Americans who suddenly find themselves

surrounded by Oriental culture.

Making

a Japanese brush behave in American style, Hume has depicted situations that

have already had servicemen in Japan roaring with laughter. His cartoons have

appeared on the bulletinboards of navy hangers, in The Navy Times, Stars and Stripes, The

Oppaman, and have been clipped to decorate lockers, desks, and service

clubs.

The

Babysan words and pictures are, of course, strictly for entertainment, but

beneath their light-hearted appearance lies an understanding and the influence

of the Japanese peoples. Babysan is not a travel bureau impression; she is not

to be found in movie travelogues; she is a phase of Japanese-American life

hitherto untouched. Here in a poignant cartoon story, the Japanese, freed from

the domination of the warlords, are seen to be a kind-hearted, amiable people,

with a keen sense of humor and with a basically democratic spirit.

To

those who served with the American forces in Occupied Japan, this book will

bring many a chuckle in recalling the happiness some little Babysan brought

into their lives. To others, this book will prove a fascinating account of the

serviceman's varied and amusing social life in the Far East. To Americans

everywhere, this significant first book by the talented Bill Hume will be

sure-fire cartoon entertainment.

Press

release Number One ends here. There is a tinge of racism (not to mention

sexism) in both the press release and the cartoons, no doubt. But in the

context of the times, the humane understanding embodied in both was noteworthy.

World

War II began for Americans with the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, an

infamous act of international treachery that thoroughly shaped American

attitudes about the Japanese for a generation—a generation that included Bill

Hume and his shipmates. It was the same generation that, at the close of

hostilities, discovered how brutally the Japanese had treated prisoners of

war. (This was, you may recall, a cultural thing: surrendering was

unthinkable to the Japanese soldier of that time, so they regarded anyone who

did as subhuman and treated them accordingly—hence, the Bataan Death March, for

instance.)

With

all that history fairly fresh in the American collective consciousness, the

press release can be seen as a nearly heroic gesture at reconciliation between

the two cultures.

And

Hume's cartoons made the same gesture. Indeed, the humor of his cartoons is

often based upon the clash of American and Japanese cultural habits, a clash

that creates comic incongruity. Many of these explanatory text passages were

penned by a shipmate of Hume's, John Annarino, who launched and edited The

Oppaman, the base newspaper in which Babysan regularly appeared.

THE SECOND

PRESS RELEASE tucked into the volume was a biography of Hume. Born William

Stanton Hume on March 16, 1916, in Hinton, Missouri, and, except for his

sojourn in the military, he never strayed far from the Show Me State. He was a

precocious kid, graduating from high school at the age of 15.

In

high school and subsequently at the University of Missouri in Columbia, Hume

performed as a stage magician, but he paid his way through college doing

posters and publicity art for the drama department, where he stayed for a year

after graduating in 1936 with a degree in journalism and advertising.

Working

in the campus theater, Hume selected, produced, directed, and often wrote the

one-act plays presented at the University. His one-act play, “The Oracle,” was

judged one of the thirteen best one-act plays in the United States in 1937 and

was published by Noble and Noble of New York City in a book collection of the

outstanding one-act plays of the day.

In

1937, Hume moved to Stephens College in Columbia where he worked with famed

actress Maude Adams (1872-1953), who had achieved her niche in thespian annals

by playing Peter Pan, which, with other roles in J.M. Barrie plays, earned her

an annual income of over a million dollars during her peak years in the first

two decades of the 20th century. Adams put Hume in charge of costume

and scenery design for the productions she presented at the college. Their

association lasted for four years, but it had a bumpy beginning.

When

I finally met and interviewed the illusive Bill Hume, living in 2002 where he

had almost always lived, in Columbia, Missouri, he told me Adams began by

wanting to send him to New York to learn stage techniques.

Hume

said, “Miss Adams, if I go to New York and learn all there is to know about

stage, scenery and so forth, I’m not coming back to Stephens College. And she

said, Oh, Mr. Hume. You Missourians are all so stubborn.” Hume laughed.

“I

couldn’t take her for too long,” he continued, “so I went up to the Kansas City

Art Institute for a while.”

After

his service in World War II, though, Hume returned, briefly, to Stephens

College: “Their technical director quit in the first part of the year, so I

filled out his year there at what Stephens called The Playhouse, the Drama

department. I designed scenery.” But Adams was no longer there.

After

taking courses in commercial art at the Kansas City Art Institute and doing a

little of it on the side, Hume struck out on a freelance career, drawing for

trade publications and doing newspaper advertising illustrations. He spent a

summer in Lakeside, Ohio, where he did publicity for a theater. And he also

sought to continue in the editorial cartooning profession he’d dabbled in while

in college with Herblock his idol.

While

he was in Kansas City, he applied at a couple of papers, but before anything

came of either offer, the papers went out of business.

“I

was a jinx,” Hume said, laughing. “I got an offer from a St. Louis paper and

another for twelve dollars a week for some newspaper down in south Missouri,

and I turned it down. I turned down the one in St. Louis because it wasn’t

much better. And they went out of business, anyway. So I never fooled with

them very much.”

“I

met a couple of real swell guys at Kansas City Star,” he continued,

“—old boy by the name of Wood and S.J. Ray. They were both real nice guys, and

they were trying to help me. They couldn’t. Did their darndest but never made

it, any kind of way. I ran into the guy in Kansas City who published the Missouri Republican, a guy by the name of Hebert Nations. I did a few

editorial cartoons for him, and then I got called up. I had to go into the

Navy, and he says, ‘When you get out of the Navy, let me know right away. We’ll

go into Chicago and take you up to the owner of the Chicago Tribune,’

Robert McCormick. He said, ‘We’re good friends. We’ll see that you get

yourself started.’ Well, anyway, I got out of the Navy and I called Hebert

Nations. That’s a really good name: Hebert Nations. Good name. Anyway, I got

his secretary and she said that Hebert was sick, and that he wanted me to do a

cartoon on such-and-such. She said, ‘We’ll run it because I know Hebert, and

he trusts you.’ So I did some cartoons for him, and the next thing, I heard he

died. So that was the end of that. I’m a jinx.”

“I’m

not too good at editorial cartoon humor,” Hume finished. “I like humor, but

with editorial cartoons, you get to really smack some people between the eyes,

and I’m not like that.”

Hume

was inducted into the U.S. Navy in October 1942. The Navy, like all branches of

the U.S. military, was just learning how to conduct itself. Hume intended to

become a sonar technician, but he found he had trouble distinguishing different

tones. And then his paperwork was lost. But in two months of basic training in

Key West, Florida, the Navy finally found a place for the young artist: he

became an aircraft painter first class and was sent to Coco Solo Naval Base in

Panama.

Hume

found he had a certain amount of spare time after his duties “smearing paint

around” in the paint locker, so he presented himself at the base welfare office

and asked if they needed an artist—or a cartoonist. They did. Soon, he was

attached to Special Services, editing the base newspaper, Contact, and

drawing cartoons for it.

Most

of the cartoons retailed the adventures of a local fictional beauty named Kay

Pasa.

“You

know what that means?” Hume asked me.

“Yes—‘What’s

going on?’ ‘Que pasa?’”

“All

the sailors used that term,” he said, “—the answer’s ‘pasa de nada,’ or

‘nothing doing.’”

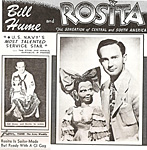

Hume

was also doing cartoons for Our Navy, but when the Panama Star Herald dubbed Hume "the U.S. Navy's most talented serviceman,” it was because of

the range and scope of the talent he displayed.

Special

Services produced stage shows to entertain the troops, and here, Hume’s

variegated experience blossomed. Before long he was writing skits and acting in

them as well as doing posters, designing costumes, and painting scenery. He was

master of ceremonies for the USO unit and revived his magic act. But he soon

gave that up to pursue another stage proclivity.

“Magic

was my hobby for a long time,” Hume said. “I quit that in Panama because when I

joined the USO troupe, we had a guy from the Army who was a very good

magician—a darned sight better than I was, at least. And he did the magic act,

so I switched to ventriloquism, which I’d also done in high school and college.

I didn’t have a ‘figure’ [what a ‘vent’ call his dummy],” Hume went on, “so I

made one.

He’d

made figures before. At the age of thirteen, he’d made his first one, which he

called Jean. He made four other Jeans at various times. Starting with a wire

coat hanger or something similar, he bent an armature into a skull shape,

applied plastic wood and molded the head and face, and then, after the wood

putty had set, he carved in facial details and sanded them smooth.

In

Panama, he used balsa wood to create a female figure.

“She

was mainly balsa wood, something I could carve quick,” Hume said. “And

lightweight. Very lightweight to carry around. I think she had some airplane

parts in her, with the mouth movements. And I think I may or may not have

invented something or other. You know, most hinges on the ventriloquist

figures are hinged with springs. I knew good and well I couldn’t trust a string

or rubber band, so I put the mouth movement on a weight, so she won’t work if

you turn her this way because the weight goes off. But the other way,

something pulls the weight down, and the mouth opens. And when you let go of

it, it automatically closes.”

His

figure was a feisty, flirty slightly risque dark-haired Panamanian show girl he

named Rosita.

“She

speaks very bad Spanish,” Hume said.

“Does

she speak very bad English too?” I asked.

“Well,

I could fake that,” he laughed. “I fake Spanish legitimately, my bad Spanish, I

mean.”

A

reporter for Yank, the serviceman’s weekly newspaper, came upon Rosita

in one of Balboa’s clubs, where he “overhead” her talking to a sailor while

sitting on his knee at the bar.

“‘Que

pasa?’ is the first thing she says,” the reporter noted. “After that, watch

out. Her tongue is sharp and the things she says would make you blush if you

could spare that much blood.” He then recorded the conversation:

“Have

you ever been in the United States?” the sailor asks her.

“I

was made in Panama,” she replied, narrowing her deep black eyes.

“You

mean you were born in Panama,” corrected the sailor.

“Brother,

you don’t know Panama,” cracked Rosita.

“This

sort of talk went on for ten minutes,” said the reporter. “Finally, the sailor

got up and left, carrying Rosita unceremoniously under one arm. Everyone

stamped and cheered. Bill Hume was the sailor.”

Hume

and Rosita averaged three shows a week, traveling to Nicaragua, Ecuador, the

Galapagos, and other islands and military backwaters. When Hume left the Navy

after the war, he took Rosita with him, but after a short career together, she

was retired to the Vent Haven Museum in Somerset, Kentucky.

In

1944, Hume was transferred to St. Simons Island, Georgia, where, for the pages

of the island's naval publication Tally Ho, he created another pin-up

cartoon personality—a Southern belle named Georgia, who, with her favorite

beau, was vaguely reminiscent of Daisy Mae and Li’l Abner.

“I

used the theme,” Hume said. “I tried to fake Al Capp’s style. But I don’t want

to get caught for plagiarism,” he joked.

In

1945 at the war's end, Hume was discharged and headed for the West Coast where

he freelanced for a while.

“When

I was a kid,” he told me, “I always thought I’d like to do a comic strip. My

favorite strip was a thing called Young Buffalo Bill. That was the big

thing, at least back in the thirties. So I decided to try one. I had an idea to

do a strip about a magician. I called it Padjama—awful name. And so I

went to see J.V. Connolly, the guy who was the head of King Features

Syndicate—he must’ve been out in California for a meeting or something. And I

asked him about my magician strip idea. ‘No,’ he said, ‘I don’t think it would

work.’ They already had some experience with a magician strip that came out of

St. Louis, he said. ‘We didn’t think it would last a week—it wouldn’t last a

year. It was just no good.’ And so he discouraged me as much as he could. I

later found out he was pushing Mandrake the Magician. Do you remember

that? It wasn’t a very good—”

I

laughed: “It didn’t last at all.”

“Right,”

Hume said with a grin. “Well, I had a magician friend out there in California

who was also a gag writer. And he found out I wanted to do a strip, and I

still had that magician thing in the back of my mind, so I worked with the gag

writer. We called it Swami Salami from Bombay, Indiana. Indiana, not

India. It ended up in a magic magazine called Genie, out of the West

Coast. And I let them have it for nothing because I couldn’t sell it anywhere

else. That was a big flop,” he finished with a laugh.

IN 1947, HUME

RETURNED to Columbia, Missouri, and on November 13, he married Mary Mason Clark

of Maysville, Kentucky, and he opened his art studio.

“It

was on the third floor of the Miller Building, right downtown,” Hume

remembered. “Had darn near the whole third floor, the most room I’ve ever had

and never had that much room since.”

Hume

was soon thriving. A son was born. David. A daughter was born. Elaine. And he

was getting plenty of commercial art jobs.

Then

in June 1950, the North Koreans invaded South Korea, and the U.S. was back at

war—in a United Nations “police action.” A year later, Hume was re-activated in

the Navy and shipped off to Oppama, Japan. He was there for less than a year,

assigned to “damage control.” His rate was still aircraft painter, but by 1951,

aircraft painters were included in Damage Control units. Hume’s job, however,

wasn’t painting aircraft. “They found out I was not a very good painter,” he

said.

He

worked in the technical library where he kept instruction manuals up-to-date by

inserting into loose-leaf technical volumes pages of newly revised

instructions, sent in a constant stream from the states. The task was endless,

and Hume was always behind. But he took time to draw cartoons, most featuring

fetching Japanese girls, and he posted them on a bulletinboard in the hanger.

Before long, he was art editor of the weekly base newspaper, The Oppaman, which

was edited, as we observed, by John Annarino, a journalism graduate of St.

Bonaventure University.

Annarino

was an aspiring writer: he contributed regularly to the Pacific Stars &

Stripes and to the Navy Times, and he wrote the highly successful

Far Eastern Navy show, “Damn the Torpedoes.” And he would do some writing for

Hume, too, as we’ll see in a trice.

Said

Hume: “When John left the Navy, he went to New York and worked at an ad agency

there. He ended up on the West Coast at Capitol Records. His claim to fame, I

think, is that he wrote the famous Volkswagen mini-bus ads which said:

‘Sportscar? You don’t think like that.’ He wrote the stuff. They paid him to

write two or three words.” Hume laughed. “He was that kind of a guy.”

Hume’s

pin-up cartoons were soon all about Babysan, and he also did cartoons about

everyone’s hoped-for return to civilian life, entitled When We Get Back Home.

This series and Babyson appeared not only in The Oppaman but in

the Pacific Stars & Stripes and in Navy Times.

After

putting in his months in Japan, Hume returned to Columbia and his freelance

commercial art studio. Then fans of Babysan persuaded him to collect his

cartoons about her in book form. Resorting to his file of clippings, he culled

some of his best Babysans but was unhappy with their appearance. He had

a photographer friend make photoprints of the cartoons, and then Hume touched

up the art.

“It

wasn’t redrawn,” he said, “but it was reworked.”

And

for the first Babysan book, Annarino produced explanatory text pieces

about each cartoon.

“John’s

contribution to Babysan was mainly almost what you’d call outlines,”

Hume told me. “He didn’t write any of the gag lines, but he would write a

little paragraph about every one of the cartoons, and I would expand it. That’s

the way we would work. I would draw a cartoon, and he would look at it and

write something about it. He would sit down at the typewriter and peck out a

whole paragraph. That was it. He didn’t do anything else. No corrections, no

nothing. Wonderful. I wish I could do that. Smart guy. In expanding on what

he’d written, I’d try to copy his style and I think, maybe, you could hardly

tell where one begins and the other ends.”

The

first Babysan book, Babysan: A Private Look at the Japanese Occupation, was published in 1953 by American Press in Columbia. Hume then compiled a book

of his When We Get Back Home oeuvre, published almost simultaneously;

Annarino again provided paragraphs of commentary about each cartoon.

Almost

at once, Hume began assembling material for the second Babysan book, Babysan’s

World. For this volume, he not only reworked the cartoons, he produced

illustrated explanatory material for the pages facing each cartoon. These pages

Hume called his “scrapbook.”

“I

did all that,” he said. “What little writing there is in it, I did that. John

did the Foreword, but he didn’t do anything else with the book.”

It

was published in May 1954 by Charles E. Tuttle Co., with offices in Rutland,

Vermont and Tokyo. A year later, Tuttle published another Hume volume, Anchors

Are Heavy, with cartoons about life in the Navy. This time, Annarino

produced a page of blank verse on nautical matters to face each cartoon.

The

Babysan books attracted the attention of Arv Miller, publisher of an early Playboy imitation called Fling.

“

I got a good spread,” Hume said. “He took the black-and-white drawings and he

colored them in.”

Then

Hume thought about getting Babysan into Playboy. He’d had a brief

one-way encounter with Hugh Hefner’s magazine in its formative days.

“Somehow

or other, I read that somebody was going to start a magazine called Stag

Party,” Hume said. “And I just got on my old typewriter and I wrote him a

note—‘Whatever you do, don’t use that name. Get another name quick,’” he

laughed.

“Anyway,

after the Fling thing,” he continued, “I went up to see Hefner in

Chicago to see if he wanted to do a spread on Babysan too, but he turned it

down. I had my photographer friend with me, and I asked Hefner if my friend

could get a picture of us together. And after that—doggone if that son of a

gun—he just sat there and talked and talked and talked. Spent the whole

afternoon doing nothing. He was sitting around, chewing on his pipe all this

time. He was the most friendly guy I think I ever ran into. And I didn’t look

like one of the girls at all,” he laughed.

“He

didn’t have girls around him then,” Hume continued. “He was just in an old,

beat-up office in the second or third floor of this building at the North Side

of Chicago. And he was a heck of a nice guy.”

BY THIS TIME,

HUME HAD ABANDONED his downtown art studio: in 1952, he had gone to work full

time in the printing and publishing department of the Missouri Farmers

Association, which was headquartered in Columbia. He now produced artwork for

ads, circulars, and the Missouri Farmer Magazine.

Before

his stint in Japan, he had over the years done various projects for MFA—including

designing the emblem for the MFA insurance company, a distinctive

red-white-and-blue shield. Its perfectly symmetrical shape, it turned out, was

not easy for others to copy on billboards and elsewhere.

“A

close copy is not enough,” he explained. Copies had to be perfect, so he

created a sign painter guide to assure that others would produce the emblem

exactly.

But

his chief assignment at MFA was producing animated cartoons to sell insurance

on television.

“Television

was new then,” Hume said. “A tv station had just opened up in town, and I had a

friend there who wanted me to do some art for them—black-and-white, all the

grays. And at the same time, I thought while I was doing that, I’d like to do

some animation. Back when I was at Stephens, some guy had a French camera that

took singles. He said, ‘I can take one frame at a time with this camera.’ And I

thought, ‘Well, that would be kind of fun. If you could take one picture at a

time, you could do animation very easily.’ Nothing ever happened about it at

the time. But it was just in the back of my mind then, for years. Until this tv

stationed opened up in town.

“I

bought myself a movie camera and taught myself to do animation. There were no

textbooks at that time—that was in the fifties. And at one time, I even applied

to work for Walt Disney. The letter back said they’d have to pass me by because

I didn’t know enough about anatomy.”

Hume

laughed. “Ironic, I think. I’m known for anatomy.” He laughed again. “But,

anyway, I got off on a tangent.”

He

continued: “When I got a chance to do animation, I enjoyed it, and I stayed

with it—33 years with an insurance company, of all things. People, I tell them

I work for an insurance company, they think I’m selling insurance. I don’t know

anything about insurance. But I thought I knew how to sell it on tv.

“Everything

came together at once,” he went on. “I was working in the printing and

publishing department, and I happened to show a guy in the insurance division

samples of the animation I was doing on my own at home. I’d set up what I call

‘the rig’ in my basement—a wooden rack to hold drawings in place under a 16-mm

camera so I could shoot one frame at a time. My photographer friend Andy Tau

and I designed the thing and built it. The camera mount was adjustable, and

sliding tracks permitted a variety of visual effects. So I showed some of my

animations to this guy, and he said, ‘We can use that.’ And he apparently

talked to the higher-ups, and they put me to work full time doing tv

commercials. For the next ten years, I did nothing but animation on my own.

Half of it, I did at home, and half of it, I did at the MFA shop.

“I

had to figure out some way to sell insurance,” Hume said. “This had never been

done before. Nobody had used cartooning for anything like that, to sell

insurance, of all things. They said animation was too facetious to sell

insurance. But the guy that hired me—Judd Wyatt, the advertising director—he

figured animated cartoons would sell, and they did.”

For

the first few years, Hume animated 30- and 60-second commercials, producing new

ones every 13 weeks to be used on a 23-station tv network. And he did all the

animation by himself.

And

then in 1956, he started work on a long film.

“It

was about bicycle safety for kids,” Hume said. “You see, they’d have these farm

meetings and they had to have some kind of entertainment. And so Wyatt decided

it would be a good idea to sneak safety films in and give a little lesson at

the same time. He’d been picking up old movies to show at these meetings. But

now he had this idea about safety films.”

The

idea came up and took shape on a road trip Hume and Wyatt took to Kansas City;

when they returned to the Columbia office, they converted their conversation to

a one-page script. And as Hume worked on the drawings, the project blossomed

into an office-wide enterprise: other MFA employees heard about the novel

undertaking, and they began bringing in ideas for segments. The single page of

the initial script multiplied.

Some

volunteered ideas were accepted; others rejected. Some were tried and then

discarded. One long sequence was re-done on the advice of the Missouri Highway

Patrol, with whom Hume worked all along.

By

the time Hume finished the film in mid-1958, it was a ten-minute extravaganza.

It took 14,400 individual drawings. And Hume did them all. By himself. All the

in-betweening, all the camera-work. Solo. Single-handed. A stupendous

individual feat in the quantity of labor alone, but the film had merit, too.

The

film won national awards—the Indie Award, the Oscar of the industrial film

business, another award for best use of animation, and the Best-in-Class Award

from Industrial Photography Magazine.

Entitled

“Fair Game,” it was called “Boone Crockitt” around the office. It tells the story

of a little girl named Shirley who encounters Boone Crockitt, a kid in a

coonskin cap who comes from an imaginary world to play with her. He knows

nothing of modern civilization, so Shirley teaches him how to function—and how

to survive, snatching him out from in front of on-moving cars in the street,

for instance. She also teaches him the correct way to ride a bicycle.

Later,

Hume did three or four industrial safety films, one of which—on fire—he wrote.

They were used by insurance agents, civic clubs, and law enforcement agencies

throughout the country.

By

then, MFA had hired some assistants for him.

Animated

commercials were replaced by live-action footage in the early sixties, but Hume

still had plenty to do. Most of his work the last years before he retired in

1985 was for the MFA marketing department—brochures, circulars, signs,

hand-lettered posters, detailed charts and graphs, and, occasionally, cartoons.

“In

this type of work,” he said, “you had to be pretty diversified, doing many

kinds of things and getting the job out on deadline. I never knew who was going

to come into my office or what their project was. They usually had a rough idea

or theme, and we developed it.”

Sometimes

“we” developed an idea way beyond the client’s expectations. While Hume

preferred drawing cartoons, his inner artist couldn’t resist the occasional

temptation to embroider an assignment with decorative ruffles and furbelows.

Once when asked to produce a chart that would compare agents’ relative

production, Hume did a large oil painting of mountains with a lake in the

foreground and ships sailing across it to indicate agents’ progress.

MOST OF WHAT

I’VE JUST REHEARSED of Hume’s career at MFA I learned from Hume, not from the

press release tucked into the Babysan book. But the mystery that had

provoked my interest in Hume and Babysan still remained unsolved: why hadn’t I

or any other comics historian I knew heard of him or her?

When

I found out that Hume lived in Columbia, a day’s drive from my home, then in

Champaign, Illinois, I phoned him and arranged a meeting for an interview,

hoping to unravel the mystery.

I

stayed overnight with Frank Stack, who was on the verge of retiring from the

University of Missouri’s art department, and he drew me a map, showing how to get

to Hume’s place, south of I-70 in a sleepy residential area just west of

Stadium Drive.

When

Hume came to the door, I was surprised to see that he was rather short, just a

little over five feet, I’d say. His manner was at first reserved, even diffident,

although he warmed to our subject the longer our conversation went on. And he’d

long ago given up the cigars that had been clenched between his lips in almost

every photograph I’d ever seen of him.

At

the time, the only thing I knew about Hume was that he’d drawn Babysan, so we

started with that.

“Have

you ever read a recent book called Memoirs of A Geisha?” he asked. “No?

Well, Babysan, now I realize, was an outgrowth of the geisha, who, as I say in

one of the books, were not prostitutes. They were well-educated, proficient in

the fine arts like music, dancing, art, social graces, dress, and sometimes

intricate customs and ceremonies of the country. Highly respected. In many

cases, they were live-in lovers. Babysan became that; she was a poor man’s geisha.

Geishas were wonderful things in other times; they were not immoral, as such.

They were entertainers and I found—maybe I was all wrong but— I didn’t consider

it as a moral issue.

“Babysan

kept a lot of guys out of trouble,” he went on, “— kept them preoccupied and

because, theoretically, you were Babysan’s friend, you were accepted in various

places as long as you were with her. You could go places you wouldn’t otherwise

be able to go. The babysans rode herd on guys, and I think they did kind of a service.

Now, maybe I’m all wrong, but a lot of people didn’t think so. I don’t know

whether the custom still exists or not. I don’t know, but I bet you it does in

a smaller way. That was the whole thing. All Japanese girls that I heard

about, they were all babysans. ‘Hey, Baby. Babysan.’ You know ‘san.’ It’s a

term of respect. I was ‘Bill San,’ so it was a sign of respect, in a way. You

might not get another name for a girl: they were all ‘babys,’ babysans.”

“Reading

the cartoons in the book,” I said, “I had the idea that Babysan was probably

intimate with some of her boyfriends. But that wasn’t all of it. It wasn’t an

overt thing. It was apparent, but it wasn’t overt, I guess you could say. She

was more companionable than sexual, somehow. But there was plenty of romance

going on in the cartoons, and certainly in my imagination.”

“Yes,”

Hume said. “That was it. Now, it didn’t have to be, but babysans could be

sisterly, but not necessarily.”

I

told him that I loved the attitude that the cartoons embodied. Babysan’s

World with its alternating explanatory pages was an obvious attempt to

acquaint American servicemen with Japanese customs, but beyond that, there was

Babysan, and she was such an accommodating, pleasant—and attractive—young

woman. She was wholly uninhibited, and in that lay her considerable charm.

I

said: “She was apparently free of any kind of Puritan hang-up that would

interfere with her activity, and so the cartoons conveyed a picture of

servicemen in Japan in very cheerful, generous, open romantic relationships

with the female natives. And I’m not sure that kind of relationship was real.

Was it?”

“I

think so,” Hume said. “As I said, I was there less than a year, and I picked

brains. I had to do it quick. And I’d sit around, in the paint locker, and

we’d be guys just talking. So they started giving me ideas, and especially one

officer who’s been there four or five years. It seems, however, that I was a

little too truthful in many respects.” Then he dropped a minor caliber IED:

“The book was banned in Tokyo.”

“What?!

That’s amazing!” I sputtered. “How could that—Babysan was published all over—in

the Navy Times, Stars & Stripes...”

“Yes,

that’s right,” Hume said. “But that didn’t matter much. One reviewer said,

‘Anybody who has ideas like these doesn’t deserve a book.’ You can see the

attitude there. I was getting a little too close to somebody or other. I was

just looking for the humor in the situation. But another critic said that the

book did more to promote good relations, or explain relations between the

Japanese and the Americans, than any other book they’d ever found. That was a

woman reviewer. Most people thought the cartoons were a little naughty.”

“Well,

yes,” I said, “but I thought there was a healthy kind of wholesome straightforwardness

about it. There wasn’t any shilly-shallying about the situation—none of the

sort of behind-of-the-hand secret smirking that implied that sex was evil or

bad for you or anything of that sort.”

“It

was an existing condition,” Hume said, “and I believed I might as well report

it the way it was. I know I didn’t try to make up anything. I didn’t have to. I

was doing more reporting than anything else. One guy, a sociology major in

college, said I should have been a sociologist. I never thought of being a

sociologist. I thought I was a cartoonist,” he laughed.

I

laughed, too: “Well, I think cartoonists are probably sociologists. At least

sociologists would think so.”

“I

guess so,” Hume said. “I was visiting in the hospital here in town one day, and

I was introduced to a doddering old man who was there. Not a patient but

visiting someone. He was Carter Blanton, who owned a chain of newspapers, and

he said, ‘Oh, you’re a cartoonist? What kind of a cartoonist?’ And I said,

‘Well, I’m a frustrated editorial cartoonist.’ He said, ‘If you weren’t

frustrated, you’d never make a good cartoonist.’” Hume laughed.

“And

he was right,” he finished. “You’ve got to be a little bit frustrated. And a

little bit of a sociologist.” He laughed again.

“And

I was frustrated with this Babysan thing,” he went on, “because people, even

the officers, they were panning the idea. They didn’t like the idea.

Naturally, the moralists wouldn’t like what were going on in the Babysan

world. And so I was taking swipes at a lot of people, just doing the

cartoons.”

In

cruel contrast to the idyllic but warmly comedic romance of Babysan’s world was

another, darker post-WWII Japan. Some years before I met Hume, I’d chanced on a

book about the Occupation in Japan which maintained that Japanese women were

pretty severely abused by American servicemen who were there. And not only the

women. When I asked Hume about it, he confirmed the report.

“There

was a lot of meanness going on,” he said sadly, “—like one little incident I

remember. I didn’t see it happen—someone told me what a ‘fun thing’ it was to

do. Get in a jeep, get a two-by-four, and put it across the jeep, side-to-side,

and then run through a crowd of Japanese on the street, knocking them down with

the two-by-four. Now that’s mean.”

“Mean,

right,” I said.

“But

that was one of the ‘fun’ things to do,” Hume said sarcastically.

“Well,”

I said, “the world that you portrayed was distinctly not a world like that.”

I

mentioned Milton Caniff’s Miss Lace, an obvious soul sister of Babysan’s, and

we talked a little about Steve Canyon’s Miss Mizzou, the lady wearing

nothing but a trenchcoat whose name Caniff borrowed from the University of

Missouri. The resulting publicity accruing to the University tempted the city

fathers, momentarily, to name Stadium Drive after the character, but wiser

heads ultimately prevailed; today, only a short street in a residential area

bears Mizzou’s name.

On

campus, she fares better. A huge, bigger than life drawing of Mizzou decorates

a wall inside the Alumni Building entrance; just outside is a sculpture of

Beetle Bailey, commemorating another cartoonist graduate, Mort Walker. No

statues of Babysan, though. No Babysan murals.

“I

missed Walker,” Hume said. “I never ran into him while he was here, just after

World War II.”

He

never met Caniff either; Caniff came to the campus often during Miss Mizzou’s

heyday. Nor did Hume meet Bill Mauldin during Mauldin’s brief visit to Oppama.

Said

Hume: “I wish I had because I always admired Mauldin. I thought he did a great

job during the war.”

At

one time or another, Hume briefly considered other avenues for his cartooning.

“I

made a few submissions to magazines every now and then,” he said. “I used to

have one of these brown envelopes full of rejection slips years ago. I remember

one of them: they said something like ‘this batch of cartoons did not wake us

up. Next time, try a bomb,’ he laughed. “That’s what I was sending

them—bombs.” He laughed again.

Recalling

his earliest submissions to magazines, Hume said: “Back in those days, they did

something which would be unthinkable now. I sent stuff to several magazines,

and at least one, maybe more, sent me back originals of other cartoonists to

study, to see, to improve my technique. Original art, complete with white-out

and everything. Nowadays, that’s unthinkable. I don’t know how they got away

with it. I guess in those days, the originals were throw-aways. Send them to

some budding artists and let ’em learn.” He laughed.

“I

never had any urge to do comic books,” Hume said when I asked about them. “I

used to read them, and I’d enjoy them—what an amazing amount of work that goes

into some of those things, gosh. Once I had kind of an urge to do illustrations

for science fiction stuff. There was one—I think it was called Marvel

Stories, or some fool thing like that. I liked the illustrations but I

didn’t like the stories. So I just up and wrote to the editor, and I’ve

forgotten what my point was, but I wrote him a letter, and he sent me a check

for fifteen bucks—just for writing the letter,” Hume laughed, “—which he said

was very useful. I was very happy about that. I think I spent fifteen bucks for

more copies of the magazine.

“In

those days,” he continued, “science fiction was, of course, a no-no. It was

just the lowest of lowest. Some of the illustrations were pretty darned good.

One guy in particular—Virgil Finlay. Beautiful ink drawings. They were the top

of the line.”

At

one point in our conversation, Hume got up and left the room. A few minutes

later, he returned carrying two dolls. They could have been vent’s

figures—their clothing was fabric—but they had no moving parts.

“I

call them leprechauns,” Hume said. “I make them to give away for birthdays and

such things. I put messages on them—a sign that says ‘Down With Girdles’ or

something like that. These things are not for sale, and I’ve never sold one.”

One

of the figures was a clown. The other was an extremely buxom vamp.

“I

gave this one to my son David and his wife gave it back to me,” he laughed.

I

said: “Well, she’s a generously proportioned creature. I love the feet too.”

They were extra large.

“The

feet are very important,” he said with a grin. “Otherwise, she’d fall over.”

“Well,

balance is a real problem here with the, er, upper story.”

Hume

laughed again. “Yes, balance is important. Like people, they fall over. She has

no name,” he went on. “She probably has a name, but I don’t know what it is.”

“This

one has a sign hanging on it,” I said, and I read the sign aloud: “I cannot

give you three wishes. Maybe you’ll want to bag a fortune guard and maybe he

will give you some happiness and a wee bit of good luck.”

“They’re

made out of wood putty,” Hume said. “And coat hanger wire—anything you can make

into an armature. After shaping the wood putty, you can carve, sand, do

whatever you want to. I tell everybody I work as long as I want to. When I get

tired of it, I just quit. None of them are really ever finished.”

The

mystery I’d come in with was beginning to dissipate. Hume slid below the national

horizon after returning from Japan partly because he had so many other

artistically interesting things that took him away from cartooning. And while

pursuing his professional activities and his hobbies, he was a founder of the

Columbia Art League.

“I

won’t say I was tired of doing Babysan books,” he said, “because I did start

another one, and I darned near finished it. I guess it needs a little polish,

and it’d be ready to go. But I got off on this tangent in animation. It was

something a little different and I loved it.”

“Did

you enjoy animation more than drawing still cartoons?” I asked.

“I

kind of think so,” he said. “Sure, there’s something about seeing a drawing

come to life and start moving—it becomes something different. Yeah, I guess that’s

the whole thing. I wanted to see them move. I wanted them to come to life. I

don’t know what I would do nowadays with computers, but that's an entirely

different world, in computers.”

“Yeah,

what about that?” I said. “Some computer animation is drawing and some of it is

almost three-dimensional painting.”

“‘Shrek’

is about the only one I’ve seen,” he said. “But you know, I came away from

there, I said, ‘If there’s anything that a man, a person, can imagine, think

of, it can be done.’ There was a time you couldn’t do this kind of thing

because it was too complicated. It would take a lifetime to do it. And now, if

they do it, it doesn’t take a lifetime.”

I

ended my interview with the most provocative question unanswered—even after I

asked it of Hume.

“Babysan

had to have been very popular during the time that it was being done,” I said.

“And yet, I have met almost nobody who has heard of Babysan or has heard of you

as a cartoonist.”

Hume

was nonplussed: “No,” he said.

“Why

is that?”

He

smiled. “I don’t know. Just didn’t have a good publicity department, I guess.”

He laughed. “Didn’t have the promotion.”

*****

Here’s a

gallery of Hume ’n Babysans, and some other illustrations of his life as an

artist and cartoonist.

Return to Harv's Hindsights

|