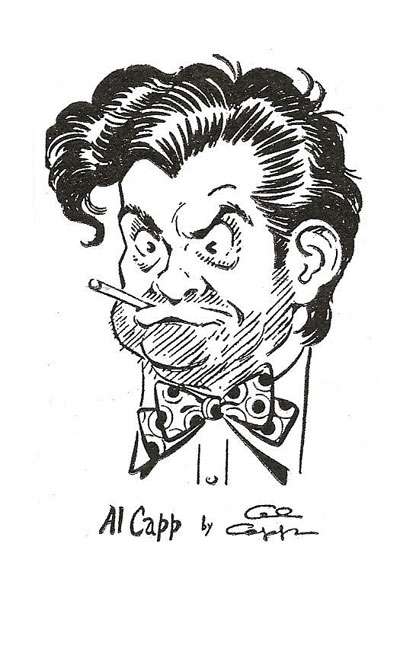

HUBRIS AND CHUTZPAH

How Li’l Abner Kayo’d Joe Palooka and Both Their Creators Came to Grief

The story of Al Capp and Ham Fisher, two cartooning geniuses, their rise to celebrity and their furious interaction with each other, is the stuff of epic adventure fiction;

but here, it is fact.

At the peak of their careers in the 1950s, they were superstars:

Capp reached 90 million readers and earned $500,000 a year ($4 million in today's dollars); Fisher, 100 million readers and $550,000 (over $4.5 million in today's dollars).

Their creations were in movies and on stage.

Shamed by his colleagues at the height of his career, Fisher died by his own hand;

Capp died in obscurity, disgraced by the sensational news of

his sexual escapades.

Preamble

HE WASN’T LIMPING: HE WAS LURCHING. He swung his left leg out sideways, almost dragging it forward for each step, and his stride had a practiced rhythm, a rolling gait punctuated by a profound dip every time he transferred his weight to his left leg, the wooden one. But it wasn’t the lurch that attracted the attention of the man in the limousine so much as it was the sheaf of paper in a blue wrapper that the tottering stroller had tucked under his arm. The man in the limousine was a cartoonist, and he thought he recognized the blue wrapping paper: it was, he believed, the paper his syndicate used to wrap rejected artwork in when returning it to hapless supplicants.

“Pull up alongside that fellow,” the man said to his chauffeur. And he turned to the woman seated next to him and said: “I bet that guy is a cartoonist.”

The subject of this wager, the young man rolling along the sidewalk on Eighth Avenue near Columbus Circle, was a somewhat shabby specimen, who, despite the chill of the spring day, was hatless and nearly coatless. But he didn’t need a hat: he had a shaggy mop of thick black hair. He had been in New York only a few weeks, and the six dollars he’d arrived with had long since evaporated. If it hadn’t been for the kindness of his landlady, whose boundless faith in her tenant’s artistic skill prompted her to stake him to his assault on the citadels of the mass media, he would have been back in his native Boston. She let him stay in her attic without paying and even gave him a little money every day for food.

He noticed the limousine slowing down as it pulled alongside him, and he watched as the rear window rolled down, and he saw the man in the back, seated next to a well-dressed woman. The man looked at him and said:

“I’ve bet my sister that you’re a cartoonist. Are you?”

He was. Or, rather, that’s what Alfred G. Caplin aspired to be that spring of 1933. And he had even sold a few cartoons from time to time, both in New York and in Boston. The year before, he had been in New York drawing a syndicated cartoon feature about a pompous young blowhard, but his heart hadn’t been in it, so he gave it up and returned to Boston and his new wife. And now, six months later, he was back in the Big Apple for another try at fame and fortune. It wasn’t a good time to be looking. The nation was firmly in the grip of what would later be called “the Great Depression.” Nationwide, fourteen million were out of work. In New York, 82 breadlines filled a million jobless bellies, but 29 New Yorkers would die of starvation that year. So when the man in the limousine offered him ten dollars to do some drawing for him, Caplin took him up on it.

And that’s how Al Capp, as he would later sign himself, met Ham Fisher, who, in the spring of 1933, was the famed creator of Joe Palooka, a comic strip about a somewhat simple-minded prize fighter who had, by accident, become the heavyweight champion of the world. It was a fateful encounter, as fraught with impending event as anything in the cliffhanging comic strips of the day’s newspapers. Capp earned his ten bucks by finishing a Sunday Palooka, and he performed well enough that Fisher hired him as his assistant at $22.50 a week. Or thereabouts. Capp did the Sunday strips, and within a few months, he was writing as well as drawing the them. But before the year was out, he would leave Fisher to devote his energies to creating his own comic strip, and in the summer of 1934, he, too, became a syndicated cartoonist with the debut of Li’l Abner. He would become as famous and feted as Fisher.

Two giants in their field, and yet when they came together, each was brought low, undone, by the same lie. And then each would destroy himself. And in their self-destruction, they would share a star-crossed fate as surely as if joined at the hip on the day they met on Eighth Avenue near Columbus Circle.

Chapter One

HAM FISHER IS THE MOST CELEBRATED CARTOONIST ever to have been drummed out of the National Cartoonists Society. He may not be the only cartoonist to be so defrocked. But his is surely the most famous case in the annals of the Society. His exit was noisy. For a brief while. And then, all fell silent.

Fisher was dead. He committed suicide within a year of the disgrace of his banishment. His name hasn’t been mentioned much since. And the silence is only one of the strange elements in this ignoble episode.

It was the notorious feud between Fisher and Capp that precipitated events resulting in Fisher’s ouster from the ranks of the Society. The story of the feud is juicy with the sort of morbid sensation that enlivens supermarket tabloids— vicarious sex, scandalous accusation, denials and attempted cover-ups, high dudgeon, and low humor. And the aforementioned disgrace and death. But there is high drama in the tale, too, in the impulse to self-destruction. And there are also contradictory aspects in the traditional rehearsal of the story, puzzles never quite solved. So it seemed to me a story worth exhumation, one of those legends that begs for careful inspection.

I didn’t always hold this conviction. But several years ago, sometime in the 1990s, I met cartoonist Morris Weiss, and over dinner with Weiss and his wife Blanche at a little place near his home in Florida, he started talking about the various places the path of his career had crossed the path of Ham Fisher’s. Weiss speaks with an admirable precision, clipping his words into a lilting syntax as he goes. No, he said in answer to my question, he didn’t think of himself as a particular friend of Fisher’s. Fisher was not a nice man, he said. Not the sort of man you’d be the friend of. But Fisher hadn’t been treated fairly, Weiss said.

My curiosity piqued, I decided to look into the sordid tale of the feud between Fisher and Capp. And when I did—when I picked up the puzzles that lay around and looked at them closely—I found in the contradictions truths that, it seemed to me, had long been overlooked.

Morris Weiss’s connection with Fisher, an admittedly tangential one, began early and ran late. Weiss spent most of his cartooning career with one or the other of two newspaper comic strips, Mickey Finn and Joe Palooka. Joe Palooka was Ham Fisher’s creation, but Weiss didn’t work on the strip with Fisher. By the time Weiss arrived at the strip, Fisher had been dead for years.

At the age of nineteen, Weiss entered the profession by lettering Ed Wheelan’s Minute Movies. After similar stints on with Pedro Llanuza on Joe Jinks and with Harold Knerr on The Katzenjammer Kids, Weiss began assisting Lank Leonard in 1936 just as the latter launched Mickey Finn, a strip about a kindly young work-a-day policeman and his Irish family. Following service in the Army in World War II, Weiss resumed his career by doing comic books for Stan Lee at Timely. Then in 1960, Weiss rejoined Leonard, eventually taking over Mickey Finn in 1968 and continuing the strip until it ceased in 1977. For about the same period, he also wrote Joe Palooka, which was then being drawn by Tony DiPreta, who would draw the strip until it ended November 4, 1984.

While still a teenager attending the High School of Commerce in New York City, Weiss visited many cartoonists in their studios, seeking advice about how to enter the profession. Among those he visited was Ham Fisher. It was about 1932 or 1933, very early in the run of Joe Palooka, and Fisher had an apartment in the Parc Vendome, a posh apartment building in Manhattan.

“Ham had moved into the Parc Vendome to live in the same building with James Montgomery Flagg,” Weiss told me. “Ham was very much conscious of celebrities; he wanted to meet the celebrities and mingle with them. So he befriended Flagg and moved into the same apartment house as he lived in. Ham was very nice when I saw him back then. He gave me a drawing. And then I didn’t see him until many years later.”

The next time Weiss encountered Fisher was in 1944, when Weiss was in the Army and home in New York on furlough. “I dropped in at the McNaught Syndicate [which distributed Mickey Finn as well as Joe Palooka] for some reason or other, and Ham was there, and we left together and shared a cab to where he was going. I recall he was telling the cabbie stories of the things he was doing for the soldiers through the comic strip and with chalktalks in hospitals and things like that. And when the cabbie heard everything Ham had to say—apparently the cabbie was already a veteran, and he started to tell Ham stories about his army life, and at that point, Ham lost interest.”

Clearly, Weiss implied, Fisher was too wrapped up in himself to listen to anyone else’s life story. At this time in his career, Fisher was a national celebrity of “Roman self-esteem,” as Time put it (November 6, 1950; 77), and around New York City, he was a well-known denizen of fashionable night life. “He lived like a lord,” writes Jay Maeder in “Fisher’s End,” published in Hogan’s Alley no.8 (Fall 2000), “and he always had the best seats at the races and the prizefights and the musicals, and he played golf with Bing Crosby and boasted about it” (92).

Fisher was widely-known and liked in the sporting world. He watched every notable prize fight from the press box, and the fans were reportedly as eager to see him as they were to see the fight. He was welcome in every training camp and fight gym. He was a member of the Boxing Writers Association, and he spent much of his time outside his studio at training camps, “picking up ring color and even sparing with the fighters,” reported Newsweek (December 12, 1939; clipping, n.p.).

Joe

Palooka was without

question one of the most popular comic strips of the period. Depicting the

adventures of a good-hearted if somewhat simple-minded prize fighter

(ostensibly, the world’s heavyweight champion), the strip consistently placed

among the top five comic strips in readership surveys in the forties and early

fifties. According to a 1950 report in Time, Fisher’s strip was right

up there with Blondie, Little Orphan Annie, Dick Tracy,

and Li’l Abner (clipping, n.d., n.p.).

Fisher told action-oriented adventure stories, full of exotic incident as well as a healthy dose of humor. And he was expert at prolonging the agonies he inflicted upon his characters, creating suspense-filled storylines the equal of any contrived by his cohorts in the cliffhanger game. His cast included Joe’s long-suffering and voluble manager, Knobby Walsh, who loves Joe but has an eye always on gate receipts, too. Reportedly a blend of the personalities of several prominent fight personalities, notably Jack Bulger (once handler of Mickey Walker) and Doc Kearns (Jack Dempsey’s manager) and Tom Quigley (a Wilkes-Barre boxing promoter), Knobby is often supposed to be Fisher’s alter ego in the strip, a supposition Fisher himself fostered. The other principal character is Joe’s fiancé, the beauteous blonde Ann Howe, whom the champ finally marries on June 24, 1949, after an eighteen-year engagement. (It was in the air. Dick Tracy married Tess Trueheart on Christmas Eve, 1949; and Li’l Abner married Daisy Mae on March 29, 1952.) To this group, Fisher added redheaded Jerry Leemy, Joe’s excitable wartime Army buddy, and, later, the hugely comic heavyweight, Humphrey Pennyworth, a 300-pound village blacksmith with a heart of gold who is probably the only person who we are certain could defeat Palooka in the ring, and, later still, the homeless waif Max, a diminutive monument to unadulterated (which is to say cloying) sweetness, always attired in cast-off shoes too large for him and wearing an out-sized hat. The inspiration for Max, according to William C. Kashatus in Pennsylvania Heritage (Spring 2000), was Max Bartikowsky, a kid who lived in Fisher’s old Wilkes-Barre neighborhood who would sometimes dress up in his mother’s floppy hats and his father’s big shoes and go running up and down the street. Said Bartikowsky: “I guess that left an impression with Fisher” (28).

As for Joe himself, it isn’t quite accurate to say he is simple-minded. But how else do you describe such an uncomplicated character?

To begin with, he’s big and strong. He is, after all, a professional boxer. His shoulders are broader than anyone else’s in the strip. Except those of his opponents in the ring. He’s also entirely, doggedly, wholesome. He’s thoughtful, compassionate, and completely loyal. And humble, relentlessly humble. He embodies clean living, clean talking, and clean thinking, not to mention honesty, courage, tolerance, and devotion to duty, country, mother, and apple pie. You see what I mean by “uncomplicated”?

Even his face is uncomplicated: it’s absolutely plain, completely open and unassuming. Manly lantern jaw, tiny nose, gigantic shock of forelock, wide-open eyes. It’s the sort of face you expect on a man incapable of dissembling. Or of compromise. Or of anything mean, small, or even remotely unkind. With Joe Palooka, what you see is what you get. Simply stated, he is an ideal. An American ideal of manhood. Or of knighthood, for that is what he is—a kindly, gracious knight, righter of wrongs, defender of truth, beauty, justice, and the American way.

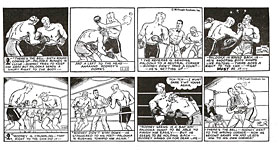

While the artwork in Palooka is distinctive and well done, it isn’t of the caliber of Alex Raymond or Hal Foster or Milton Caniff in Flash Gordon, Prince Valiant or Terry and the Pirates. It’s the stories rather than the artwork that grip and hold the reader of Fisher’s strip. There are, for example, plenty of boxing matches, and Fisher made engrossing stories out of them. Fisher’s sequences in the boxing ring are enthralling to witness. They are skillfully and realistically choreographed, every move carefully plotted. And every move that is depicted is given significance in the story, too; no wasted motions here. Every picture is accompanied by a “voice over” narrative—the voice of a radio announcer describing to his audience what he sees. In those golden days of yesteryear before television, we “watched” such athletic contests as boxing matches through the eyes of a radio announcer. So Fisher’s device enhanced the illusion of reality in the strip.

Here’s the announcer in a sequence in 1938: “Everyone is expecting Palooka to come out in the second [round] and kayo Red Rodney ... there’s the bell ... Palooka jabbed but missed Rodney, who retaliated with a beautiful left hook to the side of Palooka’s head ... Palooka danced away ... they’re sparring now. ...”

It’s Joe’s first fight against a left-hander, and he’s baffled by what his opponent does with his left hand. The announcer explains the problem as he describes the action:

“Palooka

can’t seem to evade that terrible left of Rodney’s,” the announcer says, the

picture showing Rodney landing a left hook that staggers the champ. And

then—“Palooka has changed his stance ... he’s leading with his right, southpaw

style. Will it work?” Next caption: “It didn’t ... Red feinted Joe and then

whipped in a fierce left hook. Palooka has lost every round so far.”

The fight goes on for two weeks. It was a typical Fisher performance: the fights were always deliciously long, every pugilistic nuance lovingly attended to. Finally, Joe figures out how to fight the left-hander: while in a clinch, he notices that Rodney’s left isn’t any good at short range. Joe moves in close:

“Rodney tried to spar him off but Palooka crowded him ... there’s a right to Rodney’s breadbasket ... and a left ... wow! ... it caught Red on the cheek ... he’s down ... Rodney’s on one knee ... the count is six—but there’s the bell—the round’s over.”

In Joe’s corner, his trainer marvels: “Dawggone—whut did yo’ do?”

“It’s simple,” Joe says. “I foun’ out that crowdin’ ’im dint give ’im a chanct t’ use a left—then I started usin’ a straight right.”

Joe talks like that. And his language reveals his humble nature. Fisher’s homely locutions, the merciless contractions that infest his hero’s utterances, suggest a soft-spoken manner of address. And that, in turn, reflects Joe’s essential humility, his “just folks” origins, his redeeming lack of sophistication, his wholly unpretentious personality.

There’s nothing “elegunt” (as Fisher would have him say) about his speech. He says things like: “Kin ya ’magine?” “Honist.” “I been insalted.” “I wish I could go somewheres and jist be fergot.” And when he’s excited, “Tch, tch”—his most fervent expletive. And, always a model of good manners, “Than-kyou.”

Throughout his run on the strip, Fisher reflected the beliefs of his audience. Joe Palooka was, above all else, a sentimental strip. But it was unabashed, traditional American sentiment, born and bred in the custom and aspiration of the American spirit. Its raw sentimentality may undermine our interest these days; but during the years of World War II—and for a period both before and after—the strip was in perfect step with the times. Coulton Waugh, whose venerable 1947 work The Comics successfully shaped comics criticism for decades, says this about Fisher’s strip:

The great quality that lifts the strip to the very top is simply the heart in it, the human love. All people ... know that it is love that makes men rank above the brutes, but it is exceedingly difficult to write about or speak of this precious business without assuming the righteous attitude, the smallest hint of which sends the public scampering. ... In this respect, Ham Fisher resembles Milton Caniff: neither spoils his work with preachiness.

Things just happen in the life of Joe Palooka; he doesn’t go out of his way to be good, it’s just in him. He reacts with greatness because he can’t help it. ... Simple people [took] as an ideal the big, graceful guy with thunder in his fist and with humility in his heart. ... He was one of them (283).

Year after year, Fisher told a riveting story. And his stories gave his readers something to admire, to emulate. And so why don’t we hear more about Ham Fisher and Joe Palooka in these days of revived interest in the cultural artifacts of newspaper comic strips in their Golden Age?

True, the strip’s often cloying mawkishness makes it a little less than congenial reading nowadays in the culturally sophisticated 21st Century. But there’s more to it than that. There’s also Ham Fisher himself. And to understand the near disappearance of Joe Palooka from the pantheon of comic strip greats, we have to know something more about Ham Fisher.

Chapter Two

HAMMOND EDWARD FISHER BECAME A CARTOONIST against all odds. All the odds that swayed fate anyway. Born September 24,1900 (or 1901) in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, the son of a Jewish scrapyard dealer, Fisher, to hear him tell it, surmounted the most formidable obstacle any cartoonist could have faced:

I was five years of age when I declared that I was going to do a comic strip and no amount of frustrating circumstances ever deviated me from my course. My course was set, and though I encountered many more than my share of storms, I was determined to find a harbor one day: a drawing board, a bottle of India ink, a goodly supply of Strathmore, plenty of 290 pens and—a deadline.

[But] my father objected strenuously and I could spell strenuously “s-t-r-a-p”! He despised my ambition. He wanted me to be a businessman, hence his disgust at my aesthetic taste. I wasn’t allowed to draw a picture in the house. I hid in the attic behind boxes and trunks to copy the pen lines of James Montgomery Flagg or study the composition of the great [Clare] Briggs or H.T Webster.

Young Ham was saved by his mother, as he concludes the foregoing description of his birthright in an autobiographical essay in Number 4 of a 1954 correspondence course, Illustrating and Cartooning, from Art Instruction, Inc. of Minneapolis, Minnesota:

My mother was a very literate woman and our house was filled with fine books, good paintings and the wonderful illustrations of Gustave Dore and Sir John Tenniel. These were my Heaven (5).

Ham was

focused so exclusively on drawing that he “was thrown out of every class in

school for paying no attention.” Once Fisher was safely launched on his Joe

Palooka career and the accompanying speaking tours, he enlisted a friend,

Anne Parenteau, to write a biography to be used by newspapers in promoting his

appearances. She,

quoted by the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Post to publicize Fisher’s

talk there in August 1931, continues his life story:

She,

quoted by the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Post to publicize Fisher’s

talk there in August 1931, continues his life story:

He graduated from high school in a class by himself. No one else came so close to being left [behind] as he did, so they put him in a class by himself. ... After graduation, Ham went to college for two weeks. They were two marvelous weeks spent principally in cabarets (clipping, August 20, 1931; n.p.).

Then he returned home to drive a truck for his father until the family business failed soon thereafter. He worked as a salesman for a time and then embarked upon a military career during the First World War, but, Parenteau noted, it was as short-lived as his college career had been:

The war and Ham’s first love affair both hit him at one swoop. He went to Camp Lee in Virginia and arrived at the same time that the Armistice did. This was a terrible disappointment because he had always wanted to be a hero and felt that he had lost his great opportunity to “show” before his lady love. But he got over the love affair and the disappointment and at the age of 20 got his first newspaper job as cartoonist and roving reporter for the Wilkes-Barre Record.

In his own account of his life, Fisher was profuse in thanking “a good and gracious God for letting me be on my way at last.” He produced a daily column (“Cousin Ham’s Corner”) with caricatures of local celebrities and drew a cartoon or two, sports or political. After a year, he left the Record to join the staff of the city’s other paper, the Times-Leader, he explained—:

because they let me put my name bigger on the cartoon. That’s a fact. All we cartoonists are hams and my name especially fits me. But boy, it was great. I was a personage in our city. If I hadn’t been a cartoonist do you think that judges, mayors, the governor—well, in fact everybody—would have sought me out? I had a position of influence and power, but not too much affluence. Soon I was toast-mastering at banquets, getting good money as an after dinner speaker with nice little political plums thrown my way (6).

He confessed that he even drew political cartoons for both the Democrat and Republican parties. And then, he said, “came a mistake.” He joined a friend in launching a new newspaper. It lasted only about a year, but its collapse (due to the effects of a strike in the local industry, coal mining) was undoubtedly a blessing in disguise for Fisher. A couple of years before, in about 1920, he had been smitten with an idea for a comic strip, and if the newspaper had succeeded, his comic strip might never have germinated, and the pugilistic world would have been poorer.

In his autobiographical essay, Fisher recounts the moment of inspiration that is part of the Fisher legend:

One day, while passing around the public square in Wilkes-Barre, I saw a chap whom I knew well. He was a boxer with very light blond hair which persisted in sticking straight up in the air—sort of a crew haircut without the haircut. His name was Joe [Hardy], and I knew him as a very nice guy with a lethal right hand; in other words, he was a hunk of TNT in the ring and as nice a gentleman outside the squared circle as I have ever known.

As I approached him, he noticed me and greeted me with “Hi, Ham! Hey, why don’ I an’ youse have a game of golluf at the new Muneesippal Golluf Stadium?”

I give you my word, a bolt of lightning stuck me. Within an infinitesimal part of a second I knew I had what I had prayed for all my life: the idea for my comic strip,

something out of the ordinary, the saga of a real American boy whose life gave him an opportunity for high adventure and uncommon experience. No humdrum existence, his, and I knew what he would be—he would be all the things I wished I could be, a fighter for the worthwhile things democracy teaches, a clean living champion of democracy. He would be unbeatable in physical combat, the sport of prize fighting to which fate had directed him through Knobby Walsh, his first employer, and outside of the ring he would be a gentle knight, courteous and kind, with a deep conviction of democratic principles (7).

Even Fisher admitted in the next sentence that not all of Joe Palooka came to him in that “infinitesimal part of a second.” He was writing in 1953 with the benefit of 23 years of the strip’s growth and development behind him. His description of his “gentle knight” was of Joe Palooka in 1953, not at the moment of inspiration in the early 1920s. At that moment, Fisher was envisioning a good if somewhat stupid youth whom he called Joe Dumbelletski at first when he wrote and drew the inaugural three weeks of the strip that day, back at the offices of the Times-Leader. But Fisher’s brain child didn’t see print until 1930, and by then Joe had a new last name: “palooka,” a term often used to describe a less-than-distinguished athlete, especially a prizefighter. In Joe’s case, it would be an ironic name choice. The story of the launching of Joe Palooka is another of cartooning’s legends.

Fisher went to New York in the early 1920s to sell his strip but no syndicate was interested. For the rest of the decade, Fisher kept trying, going back and forth from Wilkes-Barre (where he’d rejoined the Times-Leader after the demise of his newspaper venture) to New York. In 1927, he stayed in New York working in the advertising department of the New York Daily News. All the while, he kept peddling Palooka.

Finally, he ran into Charles McAdam, general manager of McNaught Syndicate, who promised to give Palooka a try the next year. Fisher insisted on going out himself to sell his strip to newspaper editors. To prove his ability as a salesman, he undertook to sell one of McNaught’s losers, Dixie Dugan, a strip about a would-be show girl. It had been offered around before but only two papers had bought it. Paying his own expenses, Fisher went on the road and sold the strip to thirty-nine papers in forty days.

“It was the biggest sales record in syndicate history,” Fisher claimed later in his autobiographical essay, continuing—:

Boy, I was in solid. I hadn’t cost the syndicate a dime of expense. My commissions ran into huge figures, and I was flattered all over the lot. Charley and I became great pals (he’s still my best friend), and he bragged that he had the best salesman in the country. I hadn’t told him that every editor and publisher I had seen had been given a promise by me that I’d bring back the greatest feature they’d ever seen, and I’d give them first crack at it.

When I told Charley I was now going to take Palooka out, he told me I was crazy. Why do that, when I had a great future already assured as syndicate salesman. McAdam went away on a long trip to the tropics, and I started out with Palooka. Just as I started, the market crash rocked the country. Business went to the dogs. Syndicates were swamped with cancellations. Editors called me an idiot for daring to try to sell an new feature. But in spite of the fact that this was the most terrible of all financial panics, I sold Palooka to twenty-four leading papers in as many cities in eighteen days (8).

Or maybe it was just twenty papers in three weeks. Or eighteen in 22 days. Or maybe it was 22 papers in 18 days. Or 30 in three-and-a-half weeks. The numbers, as is their wont in legends, change from one telling to the next. In any case, Fisher’s strip was at last nationally syndicated. It was 1930; Joe Palooka had been gestating for nearly ten years.

In The Adventurous Decade, Ron Goulart reveals something of the secret of Fisher’s success as a salesman. He quotes from the autobiography of Emile Gauvreau, editor of the New York Graphic before becoming editor of William Randolph Hearst’s New York Mirror: “I bought my last comic strip one New Year’s Eve when Ham Fisher ... befuddled me with a rare bottle of bourbon during a hilarious celebration. When I woke the next day, I found I was sponsor of Joe Palooka, an exemplary character who never drank or smoked and was good to his mother” (166-67).

According to Weiss, Fisher was a success as a salesman because his behavior was so outrageously ingratiating that a customer would buy his product just to get him out of the office.

Weiss told me the story of how Fisher “got to” Charles McAdam:

Lank Leonard told me this. He was with the George Matthew Adams Syndicate when he was a sports cartoonist, and Ham Fisher went to the George Matthew Adams Syndicate and he saw Frank Marky. Frank Marky was a top syndicate salesman. He had been one of the top salesman for the Chicago Tribune Syndicate; and now he was the top salesman for the George Matthew Adams Syndicate. And Ham went and saw Marky and tried to sell him the Joe Palooka strip. And Fisher was all over him, telling him how great he was and so on. Marky never saw any human dynamo to equal Ham Fisher trying to sell him Joe Palooka.

So Marky said, “I tell you what I want you to do: I want you to go over the McNaught syndicate and see Charlie McAdam, and I’ll call McAdam and tell him to see you.”

And Ham said, “Not the great Charles V. McAdam?”

“Yes, and he’ll see you”

And Ham left.

When he left, Marky called up McAdam and said, “I want you to see this character who’s coming in with a comic strip, Ham Fisher. The comic strip is nothing but you’ve never in your life seen a character like this; I want you to see him.”

Ham went in and saw McAdam, and he was all over him— on the desk, over his shoulder. And finally, McAdam said:

“Now I want you to sit in that chair and stop jumping up and down. Look,” he said, “this comic strip, this fighter, stinks. Nothing there. But I want you to go out and sell some features for me. I’m giving you expense money. But don’t use my expense money to sell this piece of garbage of yours.”

And when Ham left, a couple of guys came in and said, “What was that tornado that just blew in?”

And McAdam said, “Listen, they’re going to buy his features just to get the guy the hell out of the office.”

Joe first appeared

on April 21, 1930: he walks into a Wilkes-Barre haberdashery run by Knobby

Walsh, looking for work. Knobby hires him, but one afternoon when Knobby’s off

playing cards with his cronies, Joe permits a bunch of local toughs to loot the

store, believing they have charge accounts. Knobby is ruined, but he soon

finds a way for Joe to help him recoup. As it happens, the current heavyweight

champion comes to town, and his manager puts out the word that he’s looking for

someone to fight in an exhibition contest for $200. Knobby talks Joe into

doing it. Joe, who knows nothing about boxing, takes a drubbing for the first

four rounds, but then, when Knobby tells him that his opponent was the leader

of the looters, Joe is enraged. He charges out at the other fighter, yelling,

“You un-honist crook!” He floors him with a single blow and finds himself the

heavyweight champion.

Boxing was a popular sport in the 1930s and 1940s, and Joe Palooka was popular in consequence. Fisher soon found himself something of a celebrity. Before long, he was hobnobbing with stellar figures in sports and in other arenas of public life. As Robert H. Doyle notes in “A Champ for All Time” in Sports Illustrated (April 19, 1965), these personages Fisher often drew into the strip in cameo appearances ring-side during one of Joe’s fights—boxers Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney; politicos “Big Jim” Farley and New York’s one-time “midnight mayor” of the jazz age, Jimmy Walker; Walker’s idiosyncratically stalwart successor, Fiorello LaGuardia; movie stars like Clark Gable, Bing Crosby, and Claudette Colbert. Occasionally, a regular character in the strip would be modeled on someone in real life ... [such as] rotund Humphrey Pennyworth, for whom Toots Shor is supposed to have served as inspiration” (126).

Among the famous people Fisher cultivated was one of the most celebrated and flamboyant illustrators of the age, James Montgomery Flagg. A neighbor in the same apartment building, the cartoonist was Flagg’s frequent visitor and companion. Why a man of Flagg’s sophistication and talent would tolerate—nay, even enjoy—the company of a man of Fisher’s comparatively limited social and artistic abilities is something of a puzzle. Perhaps, as Weiss suggested to me, Flagg enjoyed having a herald, someone to precede him into restaurants and announce his coming to maitre d’s and managers.

Capitalizing on the public’s interest in boxing, Fisher imbued his stories with realistic touches. He spent as much energy in the strip building up to a big fight as real-life promoters did for real-life contests. And Joe’s training camp reeked of authenticity. But all the realism created a problem. Fisher’s cartooning ability was of the big-foot comedic school. His skill was on a par with many of his contemporaries—Sidney Smith, for instance, Harold Gray; even some of the early work of Chester Gould. But that kind of primitive realism couldn’t create the aura that presumably Fisher was now seeking. So Fisher did what many cartoonists did then (and still do): he hired an artist more talented than he to do the drawing. The first of these (and the one with the longest tenure on the strip) was another Wilkes-Barre refugee, Phil Boyle.

Because so much of the run of the strip was ghosted by others, rumors persist in the cartooning community (particularly, as Goulart reports, among older cartoonists) that Fisher

never drew the strip: even the sample strips that launched the feature, according to this tradition, were drawn by a ghost (a highschool student, so the story goes). I suspect not, but it is true—without cavil or question—that most of the years of Joe Palooka were drawn by others.

Moe Leff was one of the ghosts. In the introduction to Clark’s Classic Comic Strips Joe Palooka volume, “A Ticket to Palookaville,” Ron Goulart says that Fisher hired Leff away from Al Capp in the mid-thirties, speculating that this maneuver gave Capp “yet another reason to loathe Fisher” (12).

Leff was the principal graphic force in Joe Palooka for about twenty years. And Fisher was effusive in acknowledging his debt to Leff and Boyle. “It would be impossible to do the job without the magnificent assistance of the two great guys who help me, Phil Boyle and Moe Leff,” he wrote in his 1954 autobiographical essay. “Both of them are the very tops as artists, and Leff, especially, is a bundle of TNT who is capable of doing as great a strip as any man in the business. I’m a lucky guy to have found these two whizzes. We work as a team on every phase of the many facets of what today is a vast enterprise. And I’m ashamed to say,” he added in an earlier, much more widely circulated article for Collier’s (October 16, 1948), “they usually sit in the background while I take the bows” (28).

According to the Fisher legend, Fisher always drew the faces of Joe and Knobby; Leff left blank ovals on the illustration board, and Fisher deftly filled them in. Considering that the faces of Joe and Knobby were rendered very simply compared to the visages of other characters in the strip, this contention is probably true.

Another of Fisher’s assistants, for a short time in 1933, was, as we’ve said, Al Capp.

Chapter Three

AL CAPP WAS

BORN ALFRED GERALD CAPLIN on September 28, 1909, in New Haven, Connecticut, of

East European Jewish heritage. His parents had come from Latvia to New Haven in

the 1880s. “My mother and father had been brought to this country from Russia

when they were infants,” Capp wrote in 1978 (quoted in Wikipedia). “Their

fathers had found that the great promise of America was true—that it was no

crime to be a Jew.” Alfred was the eldest son of Otto Caplin, a chronically

unsuccessful salesman, and Matilda Davidson, a woman with a fierce survivor

instinct who shepherded her family through a persistently penurious existence.

William Furlong explains how (in The Saturday Evening Post, Winter 1971):

“She tutored her children in the techniques of living on nothing at

all—wheedling stale bread from bakers, refusing to deal with grocers who

wouldn’t hire one of her sons, leading the children on rubbish raids that might

turn up a few usable items of clothing or even an unused piece of coal” (45).

Whenever she ran out of rent money, the family moved, first to Bridgeport and

then from one rented house to another in Boston.

As a child, Capp (the pen name he adopted as his legal name in 1949) had been a prodigious reader. He'd read Joseph Conrad, Anthony Trollope, Charles Dickens, and all of Shakespeare. And he'd read all of Bem,rnard Shaw—at the age of thirteen. He'd done a lot of reading during his youth because he couldn't be physically active. He'd lost his left leg when he was almost nine. One hot afternoon in August 1918, he'd hopped a horse-drawn ice wagon to pinch a shard of ice. A trolley car was only a few feet behind the ice wagon when Capp jumped off, stumbled, and fell under the streetcar's wheels. "When they took me to the hospital," he recalled, "I had no identification and so they roused me and I looked at the leg, and it was a mess—like scrambled eggs. There was just nothing that you could call a 'leg' left of it." They amputated above the knee.

After that, Capp hobbled along on crutches until he was fitted with an artificial leg. But his father, working mostly as a traveling salesman, couldn't afford to replace the leg often enough to keep pace with his son's growth. For most of his youth, Capp's wooden leg was too short, and he'd never learned to walk properly. He limped more pronouncedly than many people with artificial limbs. But he didn't complain; nor did he want sympathy.

When he wasn't reading as a kid, Capp was drawing. His father, who had trained to be a lawyer, was something of an artist, and his drawings for his family's amusement inspired his son.

“My father’s real talent was drawing,” Capp said in Furlong’s article. “He was a most naturally gifted comic artist. I grew up watching my father do comic strips on brown paper bags with my mother and himself as the two principal characters. He always triumphed over her in those strips. But only in them. Never in real life” (45).

When he was twelve, Capp read about Bud Fisher making $4,000 a week drawing Mutt and Jeff, and he decided forthwith to become a cartoonist. And in Brooklyn, to which the family moved for six months about that time, he sold his first drawings. In Cartoonist Profiles, no. 48 (December 1980), his brother Elliott tells the story of Al’s career in school:

They put him in a class of retarded children because he wasn’t normal—he was a “cripple” in the school’s parlance; he had only one leg. Of course, it was a brutal class with a bunch of real young criminals, and the only way he could survive in this terrible, physically-threatening atmosphere, was through his talent: he drew pictures. So instead of beating him up, they began to admire him and request drawings. Mostly they wanted pictures of their teacher—nude! So he survived because he could draw Miss Mendelsohn nude (81).

Capp charged twenty-five cents a piece for the pictures. But when he retold the story in his memoirs, My Well Balanced Life on a Wooden Leg, he left out the part about being in a class for retarded children. In his memory, the entire student body of P.S. 62 in the Brownsville “(or Murder, Inc.)” section of Brooklyn consisted of the retarded—“subnormals, petty thieves, rapists and thugs,” he said (19). Miss Mendelsohn became Miss Mandelbaum, and because she taught drawing, she recognized young Capp’s talent “and showed great interest in my work, coming in every day, bending over my desk to watch me draw and coaching me as I went along. My classmates showed a great interest in Miss Mandelbaum’s coaching, mainly because of what happened to her neckline when she bent over to coach me” (25).

One day when Miss Mandelbaum realized what kinds of pictures her protégé was making of her, Capp said, “she screamed a terrible scream of anguish and betrayal ... and ran out of the room. She never came back. My father’s business [in Brooklyn] failed, we moved back to Massachusetts, and my career as a professional artist didn’t get going again for ten years” (28). In Capp’s retelling, he was drawing Miss Mendelbaum in a one-piece bathing suit, not in the nude.

As a teenager, Capp often absented himself from the family hearth to wander off into unexplored climes. “At 13 or 14,” his brother Elliott wrote in the 1980 Cartoonist Profiles article, “he’d take off with his friends for Atlantic City or for Vermont” (81). One summer, after telling his mother he was going out to get a pack of cigarettes, he disappeared for two weeks. Thumbing a ride to the store, Al and a friend stopped a car the driver of which said he was going to Memphis, Tennessee. The boys promptly changed their plans: they, too, they said, were going to Memphis. And they did. By a less than direct route.

In Memphis, they stayed with Al’s Uncle George Baccarat, an orthodox rabbi, for a few days, until, as Elliott described it in his Al Capp Remembered, they managed to outrage the relatives with “their quaint toilet habits and relentless pursuit of the daughters of Uncle George’s parishioners” (63).

En route to Memphis, the youths passed through the Cumberland Mountains, and Al encountered his first hillbillies, an experience he later said inspired his creation of Li’l Abner, exaggerating the simplicity of the hill folk into a burlesque masterpiece. The hillbilly encounter, Elliott delicately implied, was part of the Li’l Abner “mythology”: “After the strip had become a success, Alfred felt that it needed a historian as the Trojan War needed a historian. And Alfred become his own Homer.”

Following an incomplete highschool career distinguished mostly by his truancy, Capp entered a succession of art schools, including the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Boston Museum School of Fine Arts, and the Designers Art School, where he met Catherine Wingate Cameron, whom he married in 1932. Explaining the litany of art schools, Capp joked that since he couldn't afford tuition, he left them one after the other when the bills came due.

At the end of this parade of art courses, Capp decided to assault the citadel of professional cartooning: he went to New York, capital of cartooning in the U.S. He eeked out a living for a while by selling advertising cartoons, but he also prevailed upon another uncle, Harry Resnick, an agent of sorts, to help him find something better. Resnick called the Associated Press and asked if someone would look at his nephew's drawings. The editor of AP’s feature service, Wilson Hicks, looked, and a short while later, he called Capp and gave him Colonel Gilfeather, a panel cartoon continuity that had been staggering along under the rather clumsy pen of Dick Dorgan. Dorgan was the younger brother of the legendary "TAD," who had made comic capital from his "low life connections."

Thomas Aloysious Dorgan, who signed his cartoons with his initials and thereby rechristened himself, had come to New York from San Francisco in 1907. He drew sports cartoons for Hearst, but he prowled backstages, streets, alleys, poolrooms, all-night beaneries, and gyms in his search for raw material. And "raw" it was for much of proper society: anyone who engaged in professional sports, from baseball players to boxers, jockeys to gamblers, sports writers to cartoonists, was regarded with disdain. If the sports pages tainted the comics—because so many of them originated in that section of the paper—TAD helped remove the taint by making people flock to his banner, eagerly looking for a chuckle. He turned aloof disdain into comradely laughter with his cartoons.

He also enriched the language by popularizing the slang of those who haunted his haunts—even minting a few new coins of phrase himself whenever he sensed a needy void in the lexicon. A drunk was a "barfly" to TAD; eggs were "cackle berries"; eye glasses, "cheaters." A restaurant was a "beanery" or a "one-arm joint," and by the same token, waitressing was "dealing off the arm." In cartoons with titles like Indoor Sports and Outdoor Sports, TAD perpetuated that breed of conversational panel cartoon in which hangers-on in the background comment, often derisively but always with comic results, on the foreground action, a format started by Clare Briggs and H.T. Webster and subsequently perpetuated by Jimmy Hatlo. And by Gene Ahern in Our Boarding House, which now TAD's brother aped in Colonel Gilfeather, a reincarnation of Ahern’s blowhard protagonist, Major Hoople. Dick Dorgan, however, did not have his brother's gift, and Hicks felt Gilfeather was failing and needed new blood. Al Capp would supply the transfusion.

Capp came to New York in the early spring of 1932 and confronted Gilfeather. It was not a felicitous encounter. His stewardship on the feature was, as it proved, a doomed undertaking. Capp was struggling to master his craft, and he had to start by imitating Dorgan. The idea was to make the shift gradually from Dorgan's style to his own. But Capp, as yet, barely had a style. He admired the pen-work of Phil May, a British cartoonist of the late nineteenth century whose economy of line anticipated modern cartoon graphic technique by thirty years. Capp had seen a book of his cartoons in the library. Capp scorned Dorgan's work, and he hated Colonel Gilfeather. Nonetheless, he slaved over it. In an attempt to whip up his interest in the feature, he shifted the focus from Colonel Gilfeather to his younger brother and retitled the cartoon Mister Gilfeather. Gilfeather the Younger was as much a blowhard as his brother, but rather than inventing money-making schemes, he spent most of his energies chasing girls, enjoying a somewhat happier prospect than the Colonel’s.

Capp lived in a succession of what he called “airless rat-hole rooms” in Greenwich Village and stalked the streets every day, reading menus in the windows of restaurants until he found a place he could afford. He was paid $52 a week for Gilfeather, enough to live on in New York, but he sent part of it to his new bride, Catherine. She was living with her parents in Amesbury, Massachusetts, because he had too little money to afford an apartment for them both. Capp kept irregular hours at the AP office, and when he came in, it was usually in the afternoon, and he worked into the evening. That’s when he met Milton Caniff, and the two formed a life-long friendship.

Caniff had just arrived in New York from Columbus, Ohio, and he worked evenings, too, and he got to know Capp very well. "He was a kind of sad sack in those days," Caniff told me. "He could be very difficult if he didn't like you. Not a charming person unless he chose to be." But Milton was charming and sympathetic. He made a good listener.

"In the daytime," Caniff reflected, "we would probably have never spoken a word to each other, but at night we talked. In an empty office like that, you talk about things you wouldn't talk about when other people were there. He and I got along fine right off the bat. I realized he was struggling—to do Gilfeather, to make it.”

By late summer, Capp had had enough. Faced with incompatible material, separated from his new wife and struggling to subsist from day to day, Capp doubtless felt the job wasn't worth the strain. Whatever the case, he quit the AP and went back to Boston, where he studied at the Museum of Fine Arts for several months before returning to give New York another try.

Chapter Four

CAPP RETURNED TO THE BIG APPLE with six bucks in his pocket and had no luck, so when Fisher stopped him that spring day on Eighth Avenue near Columbus Circle (or maybe it was on 42nd Street just outside the Daily News building; legends differ) and offered him a job, Capp eagerly accepted. For several years thereafter, both cartoonists told the same story about their initial meeting, but by 1950 when the feud was bubbling to a boil, there were two versions of that encounter—Fisher’s and Capp’s. Both versions were rehearsed in Maclean’s Magazine (April 1, 1950; clipping, n.p.). Here’s Fisher’s version:

I was driving with my sister Lois when I saw a fellow carrying a roll of paper along the street. He looked unkempt and was limping. I pulled over and said, “What kind of drawings have you in there, buddy?”

“How’d you know they’re drawings?”

“I work at the Mirror and see lots of comic strips come in wrapped in that kind of paper,” I said.

“Nobody’ll buy my drawings. I’m headed for the river,” he said.

I said, “Hop in and we’ll go to my house for lunch.”

His name was Al Capp. I didn’t tell him mine. I asked him, “What’s your favorite strip?” To my delight, he said, “Joe Palooka.”

Capp saw on my wall a portrait of me by James Montgomery Flagg, inscribed “To Ham.” Capp said: “Why, it’s you. You’re Ham Fisher.”

He begged me for a job. I had an assistant, and I couldn’t see how I could afford another one. But I took pity on him and gave him a job lettering and inking-in. Many months later, I was going on a week’s vacation. Capp came up just as I was leaving and demanded a $50-a-week raise, and sneered that I wouldn’t be able to go away if he refused to work. I blew up. I fired him and took the work with me.

When I returned, Capp called incessantly, begging for his job back. I got him a job with United Feature Syndicate where he started a hillbilly strip called Li’l Abner. It was so similar to the hillbillies I had originated in Joe Palooka that I protested to the syndicate. Capp apologized to me and promised to change the characters. He has never fully done so. He now claims he originated the cartoon hillbillies. Despite his present-day claim, Mr. Capp has stated several times earlier in interviews that I taught him what he knows.”

Capp, to whom James Edgar, the writer of the Maclean’s piece, showed Ham’s story, made a few corrections:

Fisher’s story about picking me up in his car, after accosting me in a New York street, is true [Capp said]. Fisher’s wrong when he says I was hired to “letter” for him. I was an artist—good enough the year before to do a syndicated cartoon for the Associated Press. Fisher would have been a highly impractical man to restrict a competent artist and writer to simple lettering.

Fisher cannot draw at all, except for a few simple chalktalk tricks, so when he says he “took the drawings with him,” it is a pathetic claim. I never told him Joe Palooka was my favorite strip. It’s the kind of strip I deplore, a glorification of punches and brutishness.

I was making $19 a week, later $22, while working for Fisher. For the period I was employed by Fisher, I drew in their entirety all his Sunday pages, created all the characters therein, and wrote every line. The time he went away was for six weeks, not one. He didn’t leave me any money when he went, and we had to live on what my wife was making.

I had time on my hands and whipped up Li’l Abner and sold the cartoon to United Feature Syndicate. The part where he says he got me a job with United is the part I am most bitter about. When he found out I was with United, he threatened to sue. For three years, he tried everything to get me fired.

To which Fisher responded:

I never had six weeks’ vacation in my life. When Capp worked for me, I never had more than a week. I’m amazed at Capp’s effrontery. His entire statement is false. As for suing United—that’s a gross exaggeration of a complaint I made when I learned he was spreading the lie that he had created some of the Palooka sequences. United Feature apologized to me.

Fisher’s self-aggrandizing embroideries betray his version as somewhat fictional—his generously offering lunch to an impoverished stranger, Capp’s naming Joe Palooka his favorite strip, Fisher’s taking pity on the poor lad and creating a job for him. Later in the article, Edgar quotes Fisher claiming to have “started the trend of comic strips away from vaudeville skits toward continuous adventure stories”; in fact, by 1930, Roy Crane at Wash Tubbs was well into telling adventure stories that continued from day to day. Fisher also told Edgar that he

“innovated the use of current events as story backgrounds”; I suspect Caniff was a little ahead of Fisher with Terry and the Pirates set in China.

According to the Capp clan’s version of the events of his employment on Joe Palooka, Fisher, after a few months, went off to London on a trip with Flagg—just disappeared, Capp said. Interviewed by Carol Oppenheim at the Chicago Tribune on the occasion of his retiring from Li’l Abner in November 1977, Capp said while Fisher was gone, the syndicate phoned and asked for four more weeks of the Sunday strip.

“Out of loyalty,” Capp said, “I didn’t mentioned Fisher’d vanished. I wrote the strip myself. But I wasn’t going to have anything to do with that stupid prizefighter; so I put in my own characters—the hillbillies. They were hilarious. But when Fisher came back, he fired me” (n.d. but context indicates November 1977; n.p.).

Capp maintained that he’d conjured up the hillbillies from his memory of those he’d seen in his youth on that fabled trip through the South; he took Joe Palooka into the hills and staged a match between the champ and the meanest of the hillbillies, a ribaldly uncouth character named

Big

Leviticus. This episode became the bone of contention between Fisher and Capp,

giving rise eventually to the most scandalous incident in the profession’s

short history.

In the Fisher version of these events, Fisher had the idea for Big Leviticus and wrote the story, leaving the illustration of it to Capp. In other words, he followed his usual practice in producing the strip.

The Big Leviticus story ran on Sundays in November 1933. Capp quit working for Fisher soon thereafter. He’d been working up a comic strip idea at home in the evenings, and by late winter, he was taking samples around to syndicates. In an interview with Rick Marschall in Cartoonist Profiles no. 37 (March 1978), Capp related his selling adventure:

I brought the Abner samples up to King Features, and they offered me 250 bucks a week, which is the equivalent of a thousand—even more—today. But the big guy there—[Joe] Connolly—said, “Great strip, great art, yes sir. A couple of things, though. That Abner’s an idiot. Make him a nice kid with some saddle-stripe shoes on him. And Daisy Mae’s pretty, but how about some pretty clothes? As a matter of fact, why not forget the mountain bit and move them all to New Jersey; and that Mammy—she’s got to go. You need a sweet, white-haired lady.”

Well, I thought all about it, and I realized that [he was describing] Polly and Her Pals. But I had 250 bucks a week, didn’t I? Well, I was pretty sick about it. I walked up to United Feature—[Monte] Bourjaily was the head of it then—and they looked at it, showed it to Colin Miller and the other salesmen, were amazed by it and wanted to take it out just as it was. They offered me 50 bucks a week—which was the lowest—and I grabbed it and forgot King Features because I was now able to do my own strip exactly as I wanted to. Later on, of course, they paid me $5,000 a week because there was no way they could get out of it (14).

Capp was ever after unhappy with his relationship with United. He was continually fighting for more editorial freedom. In 1947, he sued the syndicate for $14 million, alleging breach of contract, but settled out of court for an undisclosed amount. And in 1964, just after he acquired ownership of the strip, he took Li’l Abner to another syndicate, the Chicago Tribune-Daily News, where he negotiated a better deal.

Marschall continues his recounting of the story of Li’l Abner’s sale, saying Capp had told the story thousands of times. “Capp’s late Uncle Harry related to me that the problem at King Features simply was that they took too long to respond. I’m sure the truth is in both recollections. Capp’s brother Elliott told me that Al’s straight biography and his embellished versions of it are equally fascinating” (14).

Capp, a professional storyteller, knew a good story when he heard one, and to such a storyteller as he, a good story was a great improvement upon whatever mundane facts might be lying around. He often laminated his autobiographical comments with variations that improved the story or supplied a satisfying punchline.

As a matter of documented history, in June 1934, Capp signed a contract with United Feature, and Li’l Abner started in eight newspapers on August 13 (by Christmas, according to some accounts, it was in 400 papers; eventually, 900-1,000). Abner’s debut was less than a year after the Big Leviticus episode in Joe Palooka. Judging from the sequence of events, Fisher assumed that Capp had found his inspiration for a comic strip about hillbillies in the Big Leviticus story.

Catherine Capp, who had joined her husband in New York once he was on Fisher’s payroll, wrote an introduction to Volume One of the Kitchen Sink Press Li’l Abner reprint series in which she remembers inspiration striking in another way:

One night while Al was working for Fisher, we went to a vaudeville theater in Columbus Circle. One of the performances was a hillbilly act. A group of four or five singers/musicians/comedians were playing fiddles and Jews harps and doing a little soft shoe up on stage. They stood in a very wooden way with expressionless deadpan faces and talked in monotones, with Southern accents. We thought they were just hilarious. We walked back to the apartment that evening, becoming more and more excited with the idea of a hillbilly comic strip. Something like it had always been in the back of Al’s mind, ever since he had thumbed his way through the Southern hills as a teenager, but that vaudeville act seemed to crystalize it for him. ...

Al and I conferred about the characters while he was drawing his samples. I’ll take credit for naming Daisy Mae and Pansy Yokum, although contrary to popular belief, I was not the model for Daisy. The closest I came to being a model in the strip happened later when Al used my hair for Moonbeam McSwine (4).

It wasn’t just her hair. Capp once said that Moonbeam was inspired by Catherine because she, disliking big city life, spent her time on the Capp farm, out in the country—among the cows and pigs, like Moonbeam who preferred livestock and hog wallow to social high life. (Or maybe Capp was merely improving upon a good story by giving it a fictional punchline.) Indirectly, Catherine also named the strip’s protagonist: “‘Abner,’” she wrote, “was what we had nicknamed the baby when I was pregnant; it’s what we called Julie before she was born.” For Abner’s appearance, Capp claimed to be inspired by Henry Fonda, an unlikely contention on the face of it: Fonda was scarcely a national figure at the time; his first movie was in 1935, at least months after Li’l Abner was launched. But it was Fonda’s character Dave Tollier in “The Trail of the Lonesome Pine” in 1936, Capp said, that gave him the “right look” for Abner.

Although it’s not clear from Catherine’s account whether the young couple witnessed the vaudeville act before or after the creation of the Big Leviticus episode, the hillbillies on stage undoubtedly excited Capp’s imagination, leading, eventually, to a strip featuring hillbillies as the central characters.

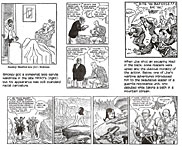

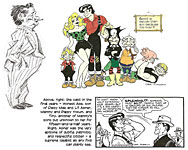

Li’l Abner Yokum is a red-blooded nineteen-year-old with the mature physique of a body-builder and the mind of an infant who lives contentedly with his diminutive mother, Pansy, the pipe-smoking matriarch of the family, and his simpleton Pappy in poverty-stricken Dogpatch, a backwoods community perched precariously on the side of Onnecessary Mountain (or, sometimes, languishing in its shadow). “Yokum,” supposedly a combination of “yokel” and “hokum,” was actually phonetic Hebrew, Capp once said—“joachim” means “God’s determination”; it was “a fortunate coincidence that the word would also pack a backwoods connotation” (Wikipedia).

The

only cloud in young Abner’s idyllic everyday blue sky is Daisy Mae Scragg, a

skimpily clad blonde mountain houri who is forever pursuing him with (“gulp”)

matrimony in mind; Li’l Abner, too stupid to realize even that he loves her,

shuns the nuptial bond as well as her embrace, imagining them as somehow

unmanly. Daisy Mae drags him before Marryin’ Sam at least once a year, but the

ceremony is invariably nullified by some groaning plot contrivance; when Capp

finally married them for good, he’d enjoyed eighteen years of dangling the

prospect before his readers. Li’l Abner’s shyness with women and his studied

reluctance to recognize sexuality at all is a satire on American puritanism:

if things were as puritans imagined, Abner wouldn’t be funny. But he is funny,

revealing that we all recognize at once how absurd the a-sexual repressiveness

is.

Capp’s Candide, Li’l Abner is fated to wander often into a threatening outside world, where he encounters civilization—politicians and plutocrats, mad scientists and cunning swindlers, mountebanks, bunglers, and love-starved maidens. By this device, Capp contrasts Li’l Abner’s country simplicity against society’s sophistication—or, more symbolically, his innocence against its decadence, his purity against its corruption. The comedy arises from this clash of cultures: we laugh to see Abner’s simple-minded struggle against the forces of civilization that seem to him so inexplicable, so utterly without practical foundation, and we roar with satisfaction when he eventually triumphs over the twisted insincerity of “high society,” his innocence, his ignorance, intact. Throughout, the humor is circumstantial, arising from the preposterousness of Abner’s predicament and his simplicity in dealing with it, rather than from carefully structured jokes. Capp’s effort was not so much to end his daily strips with punchlines as it was to finish with extravagant cliffhangers.

It was man and his society that comprised Capp’s primary targets. As a satirist, he ridiculed the pretensions and foibles of humanity—greed, bigotry, egotism, selfishness, vaulting ambition. All of man’s baser instincts, which the cartoonist saw manifest in many otherwise socially acceptable guises, were his targets. Li’l Abner is the perfect foil in this enterprise: naive and unpretentious (and, not to gloss the matter, just plain stupid), Li’l Abner believes in all the idealistic preachments of his fellowman—and is therefore the ideal victim for their practices (which invariably fall far short of their noble utterances). He is both champion and fall guy.

Capp’s vehicle was burlesque, a mode of satirical comment that allows no fine gray shadings—only stark blacks and whites. Painted only in these hues, the world he revealed was divided simply into the Good (the Yokums) and the Bad (almost everybody else). And Capp’s tactic was the shotgun: a single blast that obliterated his target without fuss or, usually, finesse.

His

criticism of American foreign aid, for instance, was contained in the creation

of Lower Slobbovia, a completely snowbound fifth-rate country whose

inhabitants, up to their chins in hostile environment, have no visible means of

support. Their favorite dish is “raw polar bear and vice versa.” Speaking in a

strange-sounding language fraught with not-so-faint echoes of Yiddish, the

natives survive entirely on the hope that the United States will provide

foreign aid. Beyond the joke of the Slobbovians’ helplessness and laziness and

their abject poverty and perpetual starvation, the satire goes nowhere. Having

taken his shot, Capp seemingly runs out of ammunition. The initial

conception—the Slobbovians and their impossible plight—is brilliant as a

criticism of American foreign policy; but Capp typically goes nowhere else with

the notion. His Slobbovian stories end but not with a sharply satirical barb

that turns on itself to sting.

In his interview with Marschall, Capp admitted that he was “so embarrassed by his endings that I try to forget them” (14). Many of his endings are thoroughly forgettable, but sometimes, often enough, Capp excelled.

Abner’s first adventure is a happily contrived satire ending with sting enough. In the first sixteen months of his life, Li’l Abner, the quintessential country hick, spends more time in New York City than in the hills of his home in Dogpatch. And in that circumstance is the flywheel of the strip’s satirical dynamic.

At the very point of our meeting Li’l Abner and his hillbilly entourage, Abner gets a letter from his rich Aunt Bessie, who invites him to spend time with her in New York society in order to acquire polish and to enjoy “the advantages of wealth and luxury.” Abner goes to the big city and stays there for the next four months.

In one episode of that sojourn, a phony baron (actually, a penniless confidence man) with an impressive beard goes after Aunt Bessie’s hand in marriage, his eye firmly focused on her fortune. Li’l Abner finds out that the baron’s intentions are less than honorable, but he’s helpless to do anything about it. His first instinct is to “smack the baron aroun’ somewhat an’ throw him outa th’ house,” but he recognizes that this behavior isn’t gentlemanly, and since his Mammy has sent him to Aunt Bessie to learn to be a gentleman, he dutifully refrains from taking this course of action.

And when he decides simply to go to Aunt Bessie and tell her what a lout the baron is, he learns that his aunt is in love. Rather than destroy her happiness, he says nothing to her about the mercenary intentions of her lover and soon-to-be-husband. It seems that Bessie is doomed to be duped.

At

the last moment—just before the wedding—Abner remembers a smattering of his

Mammy’s wisdom: “Anyone which is a skunk looks like one.” Putting this axiom

into practice, he gets a razor and forcibly gives the phony baron a shave.

Without his imposing chin whiskers, the con-man is revealed as a nearly

chinless simp. Bessie is no longer impressed, and she calls off the wedding.

The story is an insightful template for Capp satire, a handy guide to his method. Again and again over the next decades, he would perform this operation—stripping the pretensions away, revealing society (all civilization perhaps) as mostly artificial, often shallow and self-serving, usually avaricious, and, ultimately, inhumane and therefore without meaning. We laughed, but underneath the strip’s comedy, it wasn’t funny.

In his book America’s Great Comic Strip Artists, Marschall found a determinedly misanthropic subtext in the satire of Li’l Abner:

Capp was calling society absurd, not just silly; human nature not simply miguided, but irredeemably and irreducibly corrupt. Unlike any other strip, and indeed unlike many other pieces of literature, Li’l Abner was more than a satire of the human condition. It was a commentary on human nature itself (246).

In the story of the shmoo, Capp created what was probably the most sustained satire in the strip: this sequence had a beginning and an end, and all along the way, it supported and reinforced the satire. The shmoo, for those who missed it, is a soft, squishy-looking bowling-pin of a cuddly critter with two legs and feet but no arms, two eyes and one mouth but no nose, whose whole purpose in life is to make others happy, which it does by magically producing all sorts of foodstuffs and other useful items. They lay eggs “at the slightest excuse” and give milk and cheesecake; as for meat—broiled they make the finest steaks; fried, yummy chicken. They drop dead out of sheer ecstasy if you look at them hungrily. And there’s no waste: their hide makes the finest leather or cloth (depending upon how thick you slice it), their eyes make suspender buttons, and their whiskers, toothpicks. Moreover, they are available in endless supply because they breed more rapidly than fruit flies.

Li’l Abner stumbles onto shmoos in August 1948 and the world is subsequently on the brink of changing forever: once shmoos are loose in so-called civilization, humanity loses the motivation to go to war and to engage in every sort of capitalistic enterprise. Why bother? Shmoos provide everything one needs. And for that very reason, in Capp’s satirically warped mind, they had to be destroyed wholesale. Otherwise, they would “corrupt” society, demolishing the very things upon which civilization is founded—namely, greed and need. The character was such a happy satirical conception, so cute, and so popular (and so successfully merchandised), that Capp brought it back briefly in 1959, but without the merchandising success of its inaugural appearance.

Because he attacked the conventions of modern civilized society and because the most conspicuous upholders of those values were the wealthy and powerful members of the establishment and because America’s establishment was mostly political conservatives, most of the icons Capp smashed so exultantly were those of the political Right. Consequently, Capp was extremely popular with liberals.

A protean talent, Capp invented a host of memorable characters and introduced a number of cultural epiphenomena. His cast is populated with Dickensian eccentrics: the denizens of Dogpatch—Lonesome Polecat, the local Native American, and his partner in brewing Kickapoo Joy Juice, a hirsute giant named Hairless Joe; Earthquake McGoon, the neighborhood strongman; Barney Barnsmell, the “outside man” at the Skonk Works (the only indigenous industry), and his brother, Big Barnsmell, the “inside man”; the Wolf Gal, a rapacious wild girl; Senator Jack S. Phogbound; the voluptuous Moonbeam McSwine, who likes pigs better than people; and in the world beyond Dogpatch—Joe Btfsplk, a jinx whose influence was symbolized by the small raincloud that hovered always over his head; Evil-eye Fleegle, whose glance could fell an ox; Lena the Hyena, a woman so ugly Capp wouldn’t draw her; and Appassionata van Climax, an outrageously flagrant sex symbol (about which, Capp reported in surprise, no editor ever objected). Perhaps the most famous of his secondary characters is the one that threatened at times to take over the strip: introduced in August 1942, Fearless Fosdick is a razor-jawed parody of another comic strip character, Dick Tracy.

The most notorious of Capp’s contributions to popular culture is Sadie Hawkins Day, an annual November footrace (the precise date of which varies from source to source—and, doubtless, from year to year in Capp’s own mind) in which the unmarried women of Dogpatch pursue unmarried men across the countryside like so many hounds after the hare, marrying those whom they catch.

WHEN FISHER LATER CLAIMED that he created the first hillbillies on the funnies page, strenuously suggesting that his one-time assistant had stolen the idea from him, Capp, at first, treated Fisher’s claim with disdain. “I tried to ignore him,” he said in Newsweek (November 29, 1948). “I regard him like a leper; I feel sorry for him, but I shun him” (clipping, n.p.). That only enraged Fisher. He was determined to make his case. By 1954, in his autobiographical essay, Fisher had even invented a trip through the South that paralleled Capp’s legendary youthful trek. Wrote Fisher:

One great adventure in meeting people was on a selling trip at the age of eighteen when I spent several months among the hillbillies through the Great Smokey region of the South. Later, when I took Joe Palooka on a barnstorming tour, they came in mighty handy as the first hillbillies to appear in the comics. I dropped the hillbillies after several months, but they had made a hit, for many hillbilly comic strips sprung up the following year. Big

Leviticus, whom I originally called Li’l David, was a wild paranoiac character, and my great and good friend, the late John Custis, one of my publishers, tagged him as an unsavory specimen. His objection was that Leviticus was no fit company for a nice guy like Joe. You see, Leviticus had a bad habit of trying to kick Joe in the jaw while boxing (6).

The rhetoric of this contrivance is notable for its transparent argumentative ingenuity. Although seemingly a casual narrative of a mildly interesting incident in Fisher’s life, it is laced with attacks and defenses. He repeats his claim of being the originator of hillbillies in comics, and he adds that Leviticus was originally called Li’l David; from whence, clearly, Capp derived the “Li’l” of his Abner. Leviticus is an unsavory specimen; hence, so is Li’l Abner. John Custis, who could have verified this story, was conveniently dead.

That Fisher’s obsession about Capp had become utterly shameless can be deduced from the venue of the essay—an instruction booklet for a correspondence course in illustration and cartooning. Coulton Waugh, the author of the course in which Fisher’s essay is a part, asked Fisher to tell how he became successful rather than to supply a drawing lesson: Waugh’s expectation was that Fisher’s story would be inspirational to aspiring young illustrators and cartoonists. The hillbilly origin tale is wholly extraneous to the essay’s ostensible purpose—and to its running argument. But it is integral to what had, by this time, become Fisher’s absorbing preoccupation: that the hillbillies who were making Capp rich and famous appeared first in Joe Palooka.

And Fisher was right. In Al Capp Remembered, published in 1994, 15 years after Capp’s death, his brother Elliott wrote: “Alfred never quibbled about the obvious relationship between Big Leviticus and Li’l Abner. He freely admitted that his hillbilly was germinated in the Sunday pages of Joe Palooka” (72).

The essential fact was never in dispute. At issue was who created Big Leviticus. If Capp created Big Leviticus, he could scarcely be accused of “stealing” the hillbilly idea; he could, therefore, readily admit to the connection between Big Leviticus and Li’l Abner.

We’ll probably never know, with certainty, the truth about who created the hillbillies in Joe Palooka. But it is more than probable that each of the participants in the dispute has a piece of the truth on his side. Take the question of the “creation” of a comic strip character. In his mind, Fisher could legitimately claim to have created Big Leviticus and his obnoxious family even if all he actually did was to give Capp instructions to do a sequence about Joe Palooka fighting a roughneck hillbilly. The concept, as they might say these days in Hollywood and other suburbs in Lala Land, was Fisher’s. The execution might have been left entirely to Capp. And if Capp fleshed out the idea—gave personality to Big Leviticus and his entourage—he could legitimately claim to have “created” the character, too.

Weiss is certain that Fisher’s version of this episode is the truth. “I don’t know how it could be documented,” he told me. “I can only go by knowing Ham Fisher’s character—knowing what he was like—what he would do and what would be foreign to him. As far as the Leviticus thing is concerned, it would have been foreign to him to have let someone take over the strip at that time; it just wouldn’t have been done. And also, Ham Fisher showed me a letter once. And I don’t know what happened to it. But it was a letter that, during the feud, Al Capp wrote to [George] Carlin, the head of United Feature Syndicate, in which he said, he admitted, that Ham created Leviticus, and he’d like to put the matter to rest, and he would admit that it was not his character, that it was Ham’s. Well, what happened then was Ham got that letter and took it around to nightclubs and showed it to different people, and when Capp got wind of it, the feud was on all over again, hotter than ever.”

In their new biography, Al Capp: A Life to the Contrary, Michael Schumacher and Denis Kitchen allude to this mysterious note, but they didn’t find it either. Despite unprecedented access to Capp’s papers and the cooperation of his children and grandchildren, they are unable to be any more definitive than Weiss. No surprise: not everything in such a long and energetic life as Capp’s can be documented in writing (although the biographers found love letters to document Capp’s long affair with a singer in southern California.)

In their Big Leviticus scenario, Schumacher and Kitchen manage to favor both sides of the debate by knitting a few known facts together with a few reasonable speculations and adding some probably fictional connective tissue to create a cohesive story. They suppose that Capp brought the idea of hillbillies to story conferences with Fisher, but Fisher wrote the script for the Big Leviticus adventure. In support of this contention, the biographers cite a long-standing custom in the syndicate business that cartoonists submit scripts to their syndicates for approval before drawing the strips. In their narrative, Fisher did not go on vacation: he was present while Capp drew the sequence. Big Leviticus shows up again in the strip a few months later while Capp was still there, and it was during this time, they say, that Fisher went on vacation. In short, Schumacher and Kitchen find it highly unlikely that Fisher’s “brand new assistant” soloed on the Big Leviticus story so soon after joining Fisher (62-68).