Cartoonist As God

John Held,

Jr.,

Creator of an Age

John Held, Jr. is arguably the most powerful

cartoonist the print medium has ever seen. He co-created, it is often alleged,

an entire decade of American history. The period of exuberant decadence that

has entered American mythology yclept “the roaring twenties” was conjured up,

according to ample testimony on the matter, by F. Scott Fitzgerald, a novelist,

and Held, a cartoonist. Fitzgerald’s 1920 novel, This Side of Paradise, captured the spirit of disillusioned ennui

and impertinent disregard for convention that infected the joy-riding Younger

Generation in post-World War I America. And Held’s drawings of spindle-shanked

flappers and bell-bottomed sheiks of a few years later became the iconography

of what Fitzgerald had christened the Jazz Age. No novelist, and certainly no

cartoonist, had ever done the like before. Or since. Together, they put into words and pictures the feelings and tendencies then

bubbling to the surface in American life. They gave to the airy nothings of

such insubstantialities the imagery that completed the birth process.

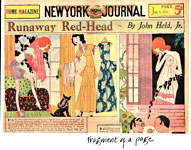

And if there is any single image that epitomizes the era it is not the gangster or the funereal Mr. Dry in Rollin Kirby’s anti-Prohibition editorial cartoons; it is that effervescent bundle of giddy self-assurance, girlish laughter, and unabashed sex appeal—the flapper. The visual symbol of the flapper did not appear widely until she was an accepted type—that is, until about 1922 or so; but she had become a familiar social phenomenon long before then. The typical flapper was a nice girl who was a little fast (“brazen and at least capable of sin if not actually guilty of it,” as Shelly Armitage says in her biography of Held). The flapper offended the Older Generation because she defied accepted conventions of decorous feminine behavior. Women’s hair had always been long; the flapper wore hers short—“bobbed.” She used make-up (which she often applied in public!). She wore tight, short dresses which bared her arms and her legs from the knees down; underneath, she wore as little as possible. But she did more than symbolize the revolution in feminine fashion and mores: she also embodied the spirit of the times in a way no other figure did.

|

|

And

John Held, Jr., a mere cartoonist, did more to create this revolutionary icon

than anyone else. And in the brevity and brilliance of his career, he enacted

in his life the meteoric character of the Age of Flaming Youth that he so

deftly illustrated with his pen.

Held

was born

In

their off hours, the two sometimes toured the Stockade, the city’s red light

district, where they acquired an education in the seamier side of society. In

this, they may have followed in the footsteps of Held’s uncle Pierre, who first

introduced young John to the Stockade.

In

1908, Held married the Tribune’s society editor, Myrtle Jennings, and sold his first cartoon to the humor

magazine Life. Two years later, he

left

When

Myrtle joined him, she transformed his life. She saw commercial value in the

comic sketches he made after hours, and she took them around to magazines and

sold them to Vanity Fair, Life, Smart

Set, and Judge. From 1912 until

1916, Held’s cartoons in Vanity Fair were signed “Myrtle Held” or “Babette” because editor Frank Crowninshield

mistakenly supposed she had drawn the cartoons she was peddling—and she, rather

than give a tedious explanation about her diffident husband, had played along,

signing her name to Held’s unsigned work.

In

1913, Held joined the art department at John Wanamaker Company, continuing at

the same time to freelance illustrations and cartoons to various magazines,

resulting, in 1915-16, in a series of covers for Smart Set. In 1916, he made a trip to

By

the time he returned (probably in the fall), his marriage was on the rocks;

Held took a room with four other youths in a rooming house on West 37th

Street—Red Smith (but not the sports writer), Hal Burrows, Paul Perez, and Marc

Connelly. Connelly later wrote of their adventures in a piece entitled “The

Doings at Cockroach Glades,” the name of the place inspired by the non-paying

residents that shared the accommodations.

There

were sleeping facilities for only four persons, but since Smith worked nights,

he slept days, leaving the beds free for the remaining quartet at night. “When

I joined the Glades’ inhabitants,” Connelly wrote of that cold winter, “John

and Hal were using the room in the daytime as a studio. Bundled up with scarves

and sweaters, the two young men sat by the drafty windows, their drawing boards

propped against the kitchen table between them, both engaged in making colored

portraits of onions, asparagus, tomatoes, and ears of corn for a seed company’s

catalogue. John’s vegetables brought him enough livelihood to allow him time to work on sculpture. As I remember, he won one or two modest

prizes offered in contests for animals and human figures carved from cakes of

Ivory Soap. I thought John’s were beautiful.”

When

the

“We

can paint battle ships in such a way that at sea they seem invisible a mile

away—or even less,” Connelly quotes Haskell as saying. “We’re also devising

camouflage for artillery concealment and even uniforms.”

Promising to show them a raincoat that “a Heinie can’t recognize

two hundred yards away,” Haskell disappeared for a moment “and reappeared

wearing a doughboy helmet and a raincoat, both painted with a dadaistic

confusion of reds, greens, yellows, blues, and browns. He stood

six-foot-two and now gave the appearance of a nightmarish Pierrot,” Connelly

said. “While the rest of us stared at his weird appearance, Held stretched out

his hands like a man groping in the dark: My God! he exclaimed, Where’s Ernie?”

About

this time, Held was hired as an artist on a Carnegie Institute archeological

expedition to

Upon

his return to

Before

his trip to

Humorist

Corey Ford maintained that Held actually invented the flapper by supplying the

Young with a prototype: “Each new Held drawing was pored over like a

Without question, Held delineated the spirit of the 1920s. More than any other cartoonist, Held captured in his graphic abstractions the fashions and fads of the collegiate jazz age. His leggy flappers with noses in the air and hose rolled at the knee and his bell-bottomed sheiks with their hair plastered tight to cue-ball heads personified the Younger Generation to a nation of readers. Sophisticated and vaguely dissolute, his scantily skirted cuties were insatiable neckers, and their tuxedo-clad escorts inveterate social bootleggers, a flask on every hip. And the drawings were rendered with matching elan—delicate, thin lines in bold contrast against arresting solid blacks.

|

|

Susan

E. Meyer in America’s Great Illustrators notes that Held’s work was unique: he “knew no predecessors. ... His work was

idiosyncratic, bearing no stylistic resemblance to that of any other artist

before him.”

Walt

Reed, historian of American illustration, agreed: “Held is impossible to

pigeonhole. His style did not grow out of anybody else’s, and no one followed

him. He was unique. His style evolved steadily from the one-eyed doll-like

figures of 1919, growing into much more sophisticated creations. They remained

unique.”

But

Held’s great friend, the theatrical caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, saw “early

influences [in] pre-Columbian sculpture and the drawings on Greek vases, as

well as the highly stylized thin-line drawings in La Vie Parisienne, a profusely illustrated French weekly,” which,

“over the years,” Held developed into “his own thumb-print” style.

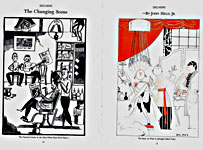

Held’s drawings appeared regularly throughout the Roaring Twenties in all the most popular magazines. He did cartoons, advertisements, covers. In 1924, Held started a weekly half-page comic strip called Oh! Margy! for United Feature Syndicate; lured away to King Features in 1927, Held continued the feature under an assortment of titles (Merely Margie, Luck Lady, Runaway Redhead, and Rah Rah Rosalie among others) until the mid-thirties.

|

|

And

in 1925, for Ross’s infant New Yorker, he began producing a series of woodcut-like drawings of the “gay nineties,” a

sharp departure in style from his more familiar style on display in nearly

every magazine of the day. The cartoonist was giving his old friend something

completely different, something entirely new, in the Held ouvre, but something

ironically a propos. Fashioned from his fond recollections of the demi-mond of

whores, pimps, gamblers, and lenient cops of turn-of-the-century

|

|

Held

was well-known and wealthy by 1921. He had moved to

His

domestic life, however, was not successful: he had divorced his first wife in

1919 and married Ada “Johnnie” Johnson, a woman animated very much by the

spirit of the Jazz Age, whose frequent demand for lavish and populous house

parties kept her husband working almost all the time. The work ethic of his

Mormon upbringing very much operative in his mind, Held was an absentee

merry-maker: while his wife and friends partied through the nights, he hunched

over his drawing board to earn the money that financed the fun. (It was to escape the milling of her throngs of house guests and

the commotion of her parties that led Held to purchase his second Connecticut

farm in 1924.)

At

the peak of his fame from 1923 until the end of the decade, Held could earn

thousands of dollars with a single drawing; editors begged for his work. “I

used to work all day, days and nights,” he recalled in a mid-1950s interview.

“Nobody believes me now, when I tell this, but people used to send me blank

checks to make drawings for them. I could write in my own price.”

Hirschfeld

tells of watching Held open his morning mail—each of twenty or thirty envelopes

containing a check for hundreds or thousands of dollars. But Johnnie was

apparently as proficient at spending it as Held was at earning it. Luckily,

Held was a fast worker. By mid-day at his studio in

Despite

the glitter of his daily routine, Held was a prisoner of his fame. Hirschfeld

recalled Held’s coming to see him off when he embarked on his first voyage to

“Gosh,

how I envy you, Al. I would give anything to just get up and go.”

Hirschfeld,

who had his life savings, $500, pinned to the inside of his jacket, couldn’t

imagine why Held didn’t just take off.

“You

could buy this tub and take it anywhere you wanted,” he said.

Held

stared at him.

“I

can’t do it,” he said. “I have a whole crew of people in

He

paused for a long time and then fixed his eye upon his friend and said: “Don’t,

for God’s sake, ever earn more than you need to live on. Try not to be too

successful.”

But

Held wasn’t always successful. His political career, for instance, after a

brilliant start, faltered. He was elected constable in Weston in 1922 and then,

in 1926, was persuaded to run as a Democrat for U.S. Congress from

Alas,

he was not elected. The Congressional

Record continued in its stodgy rut, and Held continued in his rut, too, a

much more gaily decorated one, and we are the richer as a culture for his

political failure.

And

then came the stock market crash in late 1929 and the

aftermath in which Held lost a fortune he had invested with Ivar Kreuger, the

Swedish match king. He would also soon lose his syndicate contract: in the

grimmer climate of the Depression, his silly flapper cartoons seemed

out-of-step. Magazine editors stopped commissioning covers. But the bills still

demanded payment. The accumulated pressure took its toll: by March 1931, Held

was in a

In

the 1930s, Held’s spherical-headed sheiks and

“The

long skirt imported from

Unable

to sell cartoons, Held began writing short stories about those bygone days of

Jazz Age, selling them to Scribner’s,

Harper’s, and College Humor. Between

1930 and 1937, he collected them in four volumes and wrote four novels, also

about life in the 1920s. Often bleak in the naturalistic manner, Held’s

narratives (some of which he also illustrated, sometimes with pictures not a little risque)

aimed at exposing the shallowness of the Flaming Youth of yesteryear.  Written in terse, spare

prose, his stories and novels display a fine eye for authentic detail, but they

are ultimately depressing, not amusing: here in naked prose, his satiric view

predominates and overwhelms while in his pictures of the previous decade, humor

outshines the satiric irony. Animated

chiefly by dialogue (the hallmark of the cartoonist), his prose fiction was

critically shunned and never achieved the popularity of his cartoons and

drawings.

Written in terse, spare

prose, his stories and novels display a fine eye for authentic detail, but they

are ultimately depressing, not amusing: here in naked prose, his satiric view

predominates and overwhelms while in his pictures of the previous decade, humor

outshines the satiric irony. Animated

chiefly by dialogue (the hallmark of the cartoonist), his prose fiction was

critically shunned and never achieved the popularity of his cartoons and

drawings.

In

the Smithsonian for September 1986,

Dorothy and John Tarrant record a telling episode from this, the nadir of

Held’s professional life:

One

day, Held ran into Russell Patterson, who had, by then, replaced Held at the

pinnacle of popular acclaim. Patterson offered to get Held the lucrative

assignment of designing Macy’s Christmas-toy window. Held, doubtless recalling

the advice he’d given Hirschfeld years before, declined, saying he had a room,

a coat, some shirts, trousers and a pair of shoes. That was all a man needed,

he said.

Patterson

said, “We’ll get together again. I’ll call.”

“I

have no phone,” said Held.

Less

than a popular success during the thirties, Held was to experience his greatest

artistic satisfaction during this and the following decade. He illustrated

several books, produced and hosted a collegiate talent radio program (“Tops

Variety Show”), designed sets for the successful Broadway comedy Hellzapoppin, and became (at last) a

serious artist in watercolor and bronze. His subjects in watercolor were

On

Held

occasionally did magazine illustrations, and he produced several children’s

stories. Before he died on the farm of throat cancer on

A

satirist whose comedy depended upon irony, Held’s career is itself riddled with

ironies. Aspiring to be a serious artist and sculptor, he achieved fame and

fortune beyond his most extravagant expectations with simple cartoon drawings,

undertaken initially to earn enough money to support his other artistic

ambitions. His success was so great that he was imprisoned by it; only economic

and personal disaster, a collapsing stock market and a nervous breakdown, freed

him to resume artistic pursuits.

The

supreme irony, however, was that his cartoons of the twenties, caricatures

which he intended as satirical comment on the faddish foibles of Youth, became

instead their fashion bible and brought him wealth and celebrity; but his

fiction of the thirties, satirical of the very era his cartoons had helped to

create, was scorned. His place in the pantheon of American cartoonists is

nevertheless secure: his cartoons virtually define that period now known as the

Roaring Twenties.

GALLERY OF HELD. Since Held’s images virtually define the Roaring Twenties, they have become a familiar part of the cultural heritage we all share. We recognize them because we carry them around in our heads. In selecting pictures for the essay above and the gallery below, I tried to avoid the cliche Held, and thanks to a revered ninety-year old cartoonist, I came into possession of some that I don’t think have circulated much. The photo of Held appeared in Vanity Fair in July 1930; he’s older and wiser after the stock market Crash that nearly wiped him out. The covers for McClure’s are a little more widely known, perhaps, but the two-page two-color cartoons for DAC News seem to me almost fugitives, long out of sight and consciousness. The fragments of full-page cartoons from the 1930s are likewise of a lesser-known sort, seems to me, as are the two-panel cartoons recording “Civilization’s Progress,” in which, by the 1930s, he was displaying both of the drawing styles he deployed in the 1920s—the woodcut manner he used in The New Yorker and his usual fragile line and solid blacks. After that, come several more of the pictures he drew to illustrate his novels and short stories in the 1930s, concluding with our End Piece, a 1925 cover for Life in which Held’s flapper wasn’t skinny and knobby-kneed. (Thanques, Gus.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|