HEFNER DIED.

IN HIS BED, OF COURSE

Hugh M.

Hefner, 1926 - 2017

Hugh Hefner

died on Wednesday, September 27. He was 91. Celebrated as the founder of Playboy magazine, which, with fold-out photos of barenekkidwimmin, revved a cultural

revolution that freed the sex lives of Americans from their Puritan bondage,

Hefner was a wannabe cartoonist whose magazine showcased and advanced the art

of the single-panel magazine cartoon, publishing full-page cartoons in

sumptuous color. His departure from this vale of tears was, gratifyingly,

heralded by many cartoonists (albeit of the political ilk), once potential

colleagues.

Although

Hef (as he was known since he adopted the nickname in high school in an effort

to seem cooler than he was) appeared in a dapper suit when hosting his Playboy

tv series, he was most often photographed in later years wearing a silk robe

and pajamas, which everyone supposed meant that he was taking a brief respite

from canoodling with one (or more) of the several voluptuous women he kept on

hand at the ready in the Playboy Mansion. But the real reason he was in his

pj’s was that he was so eager to get to work in the morning when he arose that

he didn’t bother to get dressed. Hef was a workaholic, and he often didn’t go

to bed at all. If he could stay awake for 24 hours to edit his magazine, he

would. Sometimes, fueled by dexedrine and Pepsi Colas, he made it to 40 hours

straight.

In

other words, the nation’s foremost exemplar of a life of “play” actually worked

all the time and seldom “played.”

Before

he thought of publishing a magazine, Hef aimed to be a cartoonist. He drew

cartoons in high school and in college at the University of Illinois, where he

also edited an issue of the off-campus humor magazine, Shaft, espousing

the liberating ideas about sex upon which Playboy was founded. All

through his youth, he drew an autobiographical comic book, and after college,

he published a book of his cartoons about life in Chicago, That Toddlin’

Town.

Hef

wanted cartoons to be a major component in Playboy, saying: “I once

commented that without the centerfold, Playboy would be just another

literary magazine. The same can be said for the cartoons. Playboy’s visual humor has helped to define the magazine.”

He

was a keen student of the cartoon medium and therefore a superlative editor of

them. Cartoonists published in Playboy all spoke of the excellence of

his insightful editorial guidance.

In

2016, Hef, still active in editing the magazine he founded, and his editors,

hoping to compete with a growing number of laddie magazines and realizing that

the Web offered more pictures of naked ladies than Playboy could ever

hope to cram into its pages, eliminated unabashed female nudity from the magazine.

(See Opus 349 for details.) That didn’t last long: within a year, naked wimmin

were back, sashaying through the magazine’s pages in unadorned splendor as of

yore.

The

new regime that published pictures of artfully draped rather than naked ladies

also decided Playboy no longer needed cartoons and stopped publishing

them. Alas, cartoons did not return to Playboy with the nudes.

With

his magazine no longer publishing cartoons, we could say, with a vaguely poetic

flourish, that Hefner’s life had lost its original meaning. And so he stopped

living.

At

the notice of Hef’s death, the supermarket’s most energetic tabloid, the National

Enquirer, leaped forward with a bushel of scandalous factoids about him and

his supposed last days. “In life,” asserted the newspaper, “Hugh Hefner knew a

million lovers and rarely—if ever—slept alone. In death, he was a bankrupt and

wrinkled recluse, withered to a skeletal 90 pounds, and cut off from even those

he most loved.”

The Enquirer claimed inside knowledge about “the tortured final days of

America’s most legendary Lothario.” The end, it was revealed, “was nothing like

the life Hef lived” according to “a Hollywood insider.”

At

the end, “he lived in shocking, urine-soaked squalor. He had to be lifted into

and out of a wheelchair. Hef was desperate to hide his true condition. He

wanted so badly to have his memory preserved as the swashbuckling playboy he

was in youth ... the virile stud with millions of hot girlfriends.

“The

truth is he became a modern-day Howard Hughes—alone, refusing to see guests,

his fingernails overgrown, his breath a putrid stench, the air around him

suffocating and musty.”

The

official cause of death was cardiac arrest. But the Enquirer reported

that he was “cancer ravaged.”

In

short, the Enquirer was having the time of its life making up stuff

about the man the tabloid doubtless secretly salivated over for his satyric

lifestyle, details of which might’ve crammed the paper with juicy copy for

years. But didn’t.

Now,

the Enquirer had the opportunity to make up about Hef’s last days

whatever lurid poetic justice it thought appropriate. So it did.

Reactions

through the so-called news media were mixed. Others in the same vein of fiction

as the Enquirer included Ross Douthat at the New York Times, who

wrote: “Hef was the grinning pimp of the sexual revolution with quaaludes for

the ladies and viagra for himself—a father of smut addictions and eating

disorders, abortions and divorce and syphilis, a pretentious huckster who

published Updike stories no one read while doing flesh procurement for

celebrities, a revolutionary whose revolution chiefly benefitted men like

himself. ...

“Early

Hef had a pipe and suit and a highbrow reference for every occasion; he even

claimed to have a philosophy, that final refuge of the scoundrel. But late Hef

was a lecherous, low-brow Peter Pan, playing at perpetual boyhood—ice cream for

breakfast, pajamas all day—while bodyguards shooed male celebrities away from

his paid harem and the skull grinned beneath his papery skin.”

Not

everyone was quite so vitriolic. But Katha Pollitt at The Nation comes

close, calling Hefner “a creep” and a “toxic bachelor. ... You have to ignore a

lot of human suffering to buy the notion that ‘Hef’ was a fun-guy genius who

brought us sexual liberation.”

Pollitt

quotes Bette Midler: “Why lionize Hugh Hefner, a pig, a pornographer and a

predator too? I once went to the ‘Mansion’ in ’68 and got the clap walking

through the door.”

“What

brought us whatever sexual liberation we now possess,” says Pollitt, “was

reliable contraception, legal abortion, and, yes, feminism. It was feminism

that encouraged women to consider their own pleasure, cut through the Freudian

nonsense about vaginal orgasms and ‘frigidity,’ mainstream female masturbation

as a way to learn about one’s body, and pointed out, insistently, that women

are not objects for male consumption ...

“Why,”

she continues, “is it so hard to ask what kind of world we make when we hail as

heroic a man who saw women as a pair of implanted breasts with a sell-by date

of their 25th birthday? It’s a conversation that Hugh Hefner did a

great deal to suppress. It’s too late for Marilyn [Monroe], but not for us. Now

that he’s dead, let’s talk.”

Peggy

Dexter at CNN leaves out most of the vitriol: “The terms of [Hefner’s]

rebellion undeniably depended on putting women in a second-class role. It was

the women, after all, whose sexuality was on display on the covers and in the

centerfolds of his magazine, not to mention hanging on his shoulder,

practically until the day he died.”

But

the president and CEO of GLAAD (a media-monitoring organization that has grown

out of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) put the vitriol back

in, albeit using a vocabulary somewhat more sophisticated than Douthat’s. Sarah

Kate Ellis criticized the news media’s coverage of Hefner’s passing:

"It's

alarming how media is attempting to paint Hugh Hefner as a pioneer or social

justice activist because nothing could be further from reality," she said.

"Hefner was a not a visionary. He was a misogynist who built an empire on

sexualizing women and mainstreaming stereotypes that caused irreparable damage

to women's rights and our entire culture."

OF THE POSTHUMOUS

EVALUATIONS of Hefner, I prefer those of Camille Paglia, a pro-sex feminist and

cultural critic, who defiantly rejects the notion that Hefner is a misogynist.

“Absolutely

not!” she said in an interview with Hollywood Reporter’s Jeanie Pyun.

“The central theme of my wing of pro-sex feminism is that all celebrations of

the sexual human body are positive. Second-wave feminism went off the rails

when it was totally unable to deal with erotic imagery, which has been a

central feature of the entire history of Western art ever since Greek nudes.”

About Playboy’s cultural impact, Paglia said: “Hefner reimagined the American

male as a connoisseur in the continental manner, a man who enjoyed all the fine

pleasures of life, including sex. Hefner brilliantly put sex into a continuum

of appreciative response to jazz, to art, to ideas, to fine food. This was

something brand new.

“I

have always taken the position that the men's magazines — from the glossiest

and most sophisticated to the rawest and raunchiest — represent the brute

reality of sexuality. Pornography is not a distortion. It is not a sexist

twisting of the facts of life but a kind of peephole into the roiling,

primitive animal energies that are at the heart of sexual attraction and

desire.”

She

adds: “It must be remembered that Hefner was a gifted editor who knew how to

produce a magazine that had great visual style and that was a riveting

combination of pictorial with print design. Everything about Playboy as

a visual object, whether you liked the magazine or not, was lively and often

ravishing. ... I would hope that people could see the positives in the Playboy sexual landscape — the foregrounding of pleasure and fun and humor. Sex is

not a tragedy, it's a comedy! (Laughs.)”

The

rest of our celebration of Hef’s life is based upon Laura Mansnerus’ obit in

the New York Times, augmented by Matt Schudel’s report in the Washington

Post, plus a couple of Hefner biographies (Bunny by Russell Miller

and Mr. Playboy by Steven Watts), various other cullings I’ve collected

over the years, and other sources named as they crop up in the ensuing

paragraphs.

PLAYBOY FOUNDER Hugh Hefner enjoyed the image

of himself that he carefully crafted as the pipe-smoking hedonist whose

magazine stampeded the sexual revolution in the 1950s. He also built a

multimedia empire of clubs, mansions, movies and television, symbolized by

bow-tied women in scanty costumes with cotton tails on their butts.

Cooper

Hefner, his son and Chief Creative Officer of Playboy Enterprises, was thinking

less of the latter than of the empire when he summarized his father’s

achievements just after he’d died: “My father lived an exceptional and

impactful life as a media and cultural pioneer and a leading voice behind some

of the most significant social and cultural movements of our time in advocating

free speech, civil rights and sexual freedom. He defined a lifestyle and ethos

that lie at the heart of the Playboy brand, one of the most recognizable and

enduring in history. He will be greatly missed by many, including his wife

Crystal, my sister Christie and my brothers David and Marston, and all of us at

Playboy Enterprises.”

As

much as anyone, Hefner helped slip sex out of plain brown wrappers and into

mainstream conversation, said Andrew Dalton at the Associated Press. In 1953, a

time when states could legally ban contraceptives, when the word “pregnant” was

not allowed on tv’s “I Love Lucy,” Hefner published the first issue of Playboy, featuring the celebrated calendar photo of Marilyn Monroe (taken years

earlier when she was an unknown aspiring starlet) sprawled naked on red satin

and an editorial promise of “humor, sophistication and spice.” The Great

Depression and World War II were over and America was ready to get undressed.

Playboy soon became forbidden fruit for teenagers and a bible for men with time and

money, primed for the magazine’s prescribed evenings of dimmed lights, hard

drinks, soft jazz, deep thoughts and deeper desires. Within a year, circulation

neared 200,000. Within five years, it had topped 1 million.

By

the 1970s, the magazine had more than 7 million readers and had inspired such

raunchier imitations as Penthouse and Hustler. Competition and

the internet reduced circulation to less than 3 million by the 21st Century,

and the number of issues published annually was cut from 12 to 11. In March

2016, Playboy ceased publishing images of naked women, citing the

futility of competing with the proliferation of nudity on the Internet.

But

Hef and Playboy remained brand names worldwide.

Asked

by the New York Times in 1992 of what he was proudest, Hefner responded:

“That I changed attitudes toward sex. That nice people can live together now.

That I decontaminated the notion of premarital sex. That gives me great

satisfaction.”

For

decades Hef cultivated the image and persona as the silk-pajama-wearing host of

a constant party with celebrities and Playboy models. By his own account,

Hefner had sex with more than a thousand women, including many pictured in his

magazine.

“I

had probably made love to more beautiful women than any other man in history,”

he once said, demurring immediately to add, “—now, I’m very sure this probably

isn’t true.”

He

flew from place to place on a private DC-9 dubbed “The Big Bunny,” which

boasted a giant Playboy bunny emblazoned on the tail. But he didn’t leave his

mansion much: there, he had at least three (and sometime more) live-in

girlfriends with whom he had sex regularly twice a week on rigidly designated

nights.

Censorship

for his magazine was inevitable, starting in the 1950s, when Hefner

successfully sued to prevent the U.S. Postal Service from denying him

second-class mailing status. Playboy has been banned in China, India,

Saudi Arabia and Ireland, and 7-Eleven stores for years did not sell the

magazine.

Women

were warned from the first issue: “If you’re somebody’s sister, wife, or

mother-in-law,” the magazine declared, “and picked us up by mistake, please

pass us along to the man in your life and get back to Ladies Home

Companion.”

HEFNER

PURPORTED TO LIVE THE LIFESTYLE that his magazine promoted: “We enjoy mixing up

cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the

phonograph and inviting in a female acquaintance for a quiet discussion on

Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.”

“Hef

excels at being his own best casting director,” wrote Bill Zehme in a Playboy article about Hef and his girlfriends, “—because he has long understood and

perfected the epic protagonist character he alone was born to portray,” going

on to quote the Man Himself:

“It

wasn’t difficult to figure out that the most successful sex object I’d created

was me,” Hef once proclaimed. “It was a role I was very comfortable playing. I

have built here [in the Mansion] what could be viewed as a perpetual women machine.”

“By

which,” Zehme explains, “he means—due to the nature of his work—there would be

no paucity of incoming prospective co-stars to audition as meaningful love

interests.”

“I’m

living a grown-up version of a boy’s dream, turning life into a celebration,”

Hefner told Time magazine in 1967. “It’s all over too quickly. Life

should be more than a vale of tears.”

Hefner

the man and Playboy the brand were inseparable. Both advertised themselves as

emblems of the sexual revolution, an escape from American priggishness and

wider social intolerance. Both were derided over the years — as vulgar, as

adolescent, as exploitative, and finally as anachronistic. But Hef was a

stunning success from his emergence in the early 1950s. His timing was perfect.

“Hefner

was, first and foremost, a brilliant businessman,” David Allyn, author of Make

Love, Not War: The Sexual Revolution, an Unfettered History, told the Washington

Post in an interview. “He created Playboy at a time when America was

entering a period of profound economic and social optimism. His brand of sexual

liberalism fit perfectly with postwar aspirations.”

When

the first issue of Playboy appeared in late 1953, Hefner was 27 years

old, a new father married to, by his account, the first woman he had slept

with. He and his wife had only recently moved out of his parents’ house, and he

had left his job at Chicago-headquartered Children’s Activities magazine.

Hefner

was reviled, first by guardians of the 1950s social order — J. Edgar Hoover

among them — and later by feminists. But Playboy’s success was

irrefutable. Long after other publishers made the magazine’s nude Playmate

centerfold look more sugary than daring, Playboy remained the most

successful men’s magazine in the world. Hefner’s company branched into movie,

cable and digital production, sold its own line of clothing and jewelry, and

opened clubs, resorts and casinos.

The

brand faded over the years, and by 2015 the magazine’s circulation had dropped

to about 800,000 — although among men’s magazines it was outsold by only one, Maxim, which was founded in 1995. Hefner remained editor in chief even after agreeing

to the magazine’s startling decision in 2016 to stop publishing nude

photographs. (Well, the models were nude, but they were profusely draped or

turned coyly away from the camera so their nudity teased rather than

tormented.)

Playboy was born more in fun than in anger. Hef’s first publisher’s message, written at

the kitchen table in his parents home in Chicago, announced, “We don’t expect to

solve any world problems or prove any great moral truths.”

The

nude pictures grabbed public attention, but the substance and variety of the

magazine’s other features — interviews, cartoons, serious journalism and

fiction — set Playboy part from other skin magazines. Hefner rejected

tawdry advertising to cultivate a more sophisticated, worldly image.

He

soon engaged a large staff of editors and artists who brought literary

sophistication and visual dash to the pages of Playboy, but there was

never any doubt that the guiding vision behind Playboy was Hef’s, and

his alone.

Hefner

wielded fierce resentment against his era’s sexual strictures, which he said

had choked off his own youth. The notorious 1948 Kinsey Report on Sexual

Behavior in the Human Male opened his eyes, and he was determined to open

everyone else’s eyes.

A

virgin until he was 22, he married his longtime highschool girlfriend, Millie

Williams. Her confession before their marriage to an earlier affair, Hefner

told an interviewer almost 50 years later, was “the single most devastating

experience of my life.” He said that the revelation shattered any illusions he

held about the virtue of women. “I’m sure that in some way, that experience set

me up for the life that followed.”

In

“The Playboy Philosophy,” a mix of libertarian and libertine arguments that Hef

wrote in 25 installments starting in 1962, his message was simple: society was

to blame. His causes — abortion rights, decriminalization of marijuana and,

most important, the repeal of 19th-century sex laws — were daring at the time.

Ten years later, they would be unexceptional.

“Hefner

won,” Todd Gitlin a sociologist at Columbia University and the author of The

Sixties, said in a 2015 interview. “The prevailing values in the country

now, for all the conservative backlash, are essentially libertarian, and that

basically was what the Playboy Philosophy was.

“It’s

laissez-faire. It’s anti-censorship. It’s consumerist: let the buyer rule. It’s

hedonistic. In the longer run, Hugh Hefner’s significance is as a salesman of

the libertarian ideal.”

The

Playboy Philosophy advocated freedom of speech in all its aspects, for which

Hefner won civil liberties awards. He supported progressive social causes and

lost some sponsors by inviting black guests to his televised parties at a time

when much of the nation still had Jim Crow laws.

Writing

in her book, Playboy Laughs, Patty Farmer elaborates: “Hefner opened the

Playboy Clubs in 1960, but he had the ‘Playboy Penthouse’ tv show in 1959. I

really think Hugh Hefner is one of the most colorblind people you’d ever meet.

He, over and over, hired the best talent. As the great comedian Dick Gregory

said, ‘Hef didn’t care if you were black, white, or purple, if you could sing a

song or tell a joke or swing an instrument.’ With the tv show, he integrated.

This was all pre-1964 Civil Rights Act. He had Nat King Cole on, sitting down

talking to a white woman, and the phones just exploded. Networks threatened to

pull the show. Sponsors threatened to pull their advertising because he had

done that. He was shocked that people would be so small-minded.

“When

he opened the Clubs in 1960, he had Dick Gregory, a great, young black

comedian. He went on in front of an all-white audience and even the audience

was shocked. Not only were they white, they were a bunch of meatpackers from

Alabama. But once Dick went into his routine they wouldn’t let him off. The

head of the Club actually went up to the Playboy Mansion to get Hugh Hefner and

said ‘You have to come over to the Club because history is being made.’ By the

time they got back, Gregory had been onstage for three hours. Comedians are a

bunch of hams. You give then a stage and an audience and nobody’s telling them

to get off and they’ll stay on forever. But the audience really loved him.”

In

the magazine, Hef brought nudity out from under the counter, but he was more

than the emperor of a land with no clothes. From the beginning, he had literary

aspirations for Playboy, hiring top writers to give his magazine cultural

credibility. It became a running joke that the cognoscenti read Playboy “for

the articles” and demurely averted their eyes from the pages depicting

bare-breasted women.

He

commissioned articles by some of the world’s most celebrated writers — Norman

Mailer, James Baldwin and Joyce Carol Oates, to name a few. Among the works

that first appeared in Playboy were excerpts from Alex Haley’s “Roots,”

Larry L. King’s “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas,” Cameron Crowe’s “Fast

Times at Ridgemont High,” John Irving’s “The World According to Garp” and Bob

Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s “All the President’s Men.”

The

magazine was a forum for serious in-depth interviews, the subjects including

Bertrand Russell, Jean-Paul Sartre and Malcolm X. In the early days Hef published

Ray Bradbury (Playboy bought his “Fahrenheit 451” for $400), Herbert

Gold and Budd Schulberg. It later drew, among many others, Vladimir Nabokov,

Kurt Vonnegut, Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, and John Updike.

The

interviews with leading figures from politics, sports and entertainment —

including Muhammad Ali, Fidel Castro and Steve Jobs — often made news. One of

the magazines’s most newsworthy revelations came in 1976, when presidential

nominee Jimmy Carter admitted in a Playboy interview, “I’ve looked on a

lot of women with lust. I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times.”

The

magazine’s formula of glossy nudes, serious writing and cartoons, coupled with

how-to advice on stereos, sex, cars and clothes, changed little through the

years and was meant to appeal to urban, upwardly mobile heterosexual men. But Playboy also had a surprisingly high readership among members of the clergy — who

received a 25 percent subscription discount — and women.

HUGH MARSTON

HEFNER was born on April 9, 1926, the son of Glenn and Grace Hefner,

Nebraska-born Methodists who had moved to Chicago. Decades later, he still told

interviewers that he grew up “with a lot of repression,” and he often noted

that his father was a descendant of William Bradford, the Puritan governor of

the Plymouth Colony. “There was no drinking, no smoking, no swearing, no going

to movies on Sunday,” he recalled in a 1962 interview with the Saturday

Evening Post. “Worst of all was their attitude toward sex, which they

considered a horrid thing never to be mentioned.”

Though

father and son reached an accommodation — the elder Hefner became Playboy’s accountant and treasurer — neither changed moral compass points. Glenn Hefner,

who died in 1976, said he had never looked at the pictures in the magazine.

As

a child, Hefner spent hours writing horror stories and drawing cartoons. At

Steinmetz High School, he said, “I reinvented myself” as the suave, breezy

“Hef,” newspaper cartoonist and party-loving leader of what he called “our

gang.” After serving in the Army 1944-46, he enrolled in the University of

Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. With an IQ of 152, he graduated in two-and-a-half

years with a BA in psychology and a double minor in creative writing and arts.

While there, he edited an issue of an off-campus humor magazine, Shaft, in

which he introduced a photo feature called “Co-ed of the Month,” which set the

wholesome “girl next door” mold he would fill in Playboy. (For more

about Shaft, see “Playboy’s First Cartoonist” in Harv’s

Hindsight for September 2008.)

Upon

marrying Millie Williams in 1949, Hefner began what he described as a deadening

slog into 1950s adulthood. He took a job in the personnel department of a

cardboard-box manufacturer. (He said he quit when asked to discriminate against

black applicants.) He wrote advertising copy for a department store, and then

for Esquire magazine. He became circulation promotion manager of a

children’s magazine.

Meanwhile,

he was plotting his own magazine, which was to be, among other things, a vehicle

for his own slightly randy cartoons. The first issue of Playboy was

financed with $600 of his own money and several thousand more in borrowed

funds, including $1,000 from his mother. But his biggest asset was the famous

nude calendar photograph of Marilyn Monroe.

Hef

had chanced upon the photo by accident. One morning at breakfast, he’d been

scanning the pages of Advertising Age and saw an article about the

calendar that mentioned it had been printed by a Chicago firm, John Baumgarth

Company in Melrose Park. He dropped his toast and set off for Melrose Park.

When

Marilyn Monroe posed nude for the calendar in 1949, she was “just another

hopeful, out-of-work actress hanging around Hollywood,” said Miller in Bunny. “Photographer Tom Kelley persuaded her to do the photo session at a time when

she badly needed the money. He paid her $50.” There were three nude photos and

a number of semi-nude poses.

Kelley

sold the lot to Baumgarth for $500. Baumgarth, which specialized in printing

calendars of all sorts, was well-stocked with pin-up pictures and didn’t use

the Monroe photos until 1951, when the iconic picture was published in a Golden

Dreams calendar, “a giveaway promotion for garages, haulage contractors,

engineering companies and the like.” Monroe was just becoming noticed as a

result of her enticing walk-away from the camera in John Huston’s “The Asphalt

Jungle” in 1950, and when she admitted, upon being questioned by the press,

that the calendar picture was of her, her star rose even more rapidly—particularly

when she confessed that she’d had “nothing on but the radio” during the shoot.

A

nude picture was pretty hot stuff in those days, and the photo of Monroe’s

naked epidermis had not been appreciatively circulated even though it had

appeared as a tiny two-color photograph in Life’s April 1952 article

about the actress.

When

Hefner showed up at Baumgarth’s on June 13, 1953, John Baumgarth showed him all

three of the nude photos. Hef liked the one that had never been used. Baumgarth

agreed to take $500 for the magazine rights and “offered to throw in the color

separations, which would save Hefner considerable processing costs. Hefner was

delighted with the deal,” Miller concluded.

Plenty

of other men’s magazines showed nude women, but most were unabashedly crude and

forever dodging postal censors. Hefner aimed to be the first to claim a

mainstream readership and mainstream distribution.

Hef

had begun promoting his magazine, which he’d named Stag Party, to

newsstand wholesalers, and he was delighted when the journal American

Cartoonist ran an article about his a-borning periodical, alerting its

cartooning readers to a new outlet for their efforts. But the publicity

prompted an unwelcomed development.

He

was putting the finishing touches on the first issue when he got a letter from

a New York attorney representing the publishers of Stag magazine. The

attorney complained that the name of Hefner’s magazine was so close to that of

his client’s that potential readers were sure to confuse the two—and his client’s

magazine was about hunting and fishing. Hef was asked to cease and desist using

the name Stag Party.

Hefner

hadn’t the resources to fight for the name—and he’d become increasingly unhappy

with it anyway—so he held a meeting with his wife and a few friends, including

a salesman he’d met when they were both in high school, Eldon Sellers, to

brainstorm a new name. They rejected Gent, Gentry, Gentleman, Pan, Satyr and

others when Sellers said: “How about Playboy?”

Mille

thought it sounded outdated and would make people think of the 1920s.

“Hefner

liked it immediately,” recorded Miller. “It had a Scott Fitzgerald flavor, he

said, and conjured up just the image he wanted to project.”

Namely,

wrote Steven Watts in Mr. Playboy, “high living, parties, wine, women

and song—the things he wanted the magazine to mean.”

Hefner

contacted a designer he’d been working with, Art Paul, and asked him to create

a new symbol for the magazine—“something like the little ‘Esky’ figure that

cavorted through the pages of Esquire.” Paul had been toying with a stag

design, but for the new title, Hef suggested a rabbit in a tuxedo as being

‘cute, frisky, and sexy’ and thus embodying the personality of the magazine.”

Of

the iconic mascot, Hef said in a 1967 interview: “The rabbit, the bunny, in

America has a sexual meaning; and I chose it because it’s a fresh animal, shy,

vivacious, jumping — sexy.” He liked the “humorous sexual connotations.”

Paul

re-drew the stag cartoon he’d prepared for the first issue, changing the head

from antlered to long-eared. Later, he spent about half-an-hour designing the

famous rabbit-head emblem. “There was,” he said, “simply no time to spend on

it.”

He

was a better designer of emblems than he was a cartoonist, as amply evidenced

by a comparison of the streamlined symbol to the mascot character he’d

re-touched.

By

the 1970s, Playboy’s rabbit head logo was so popular that readers could

simply draw a rabbit head on an envelope and were assured that their message

would reach the desired destination. Hefner has a rabbit subspecies named after

him, "sylvilagus palustris hefneri.”

When Playboy reached newsstands in December 1953, its press run of 51,000

sold out. Marilyn was on the cover—clothed —as well as inside. Also on the

cover was a cavorting cartoon woman by Vip (Virgil Partch), signifying the

other amusements within.

The

publisher, instantly famous, would soon become a millionaire; after five years,

the magazine’s annual profit was $4 million and its rabbit logo was recognized

around the world.

Hef ran the

magazine and then the business empire largely from his bedroom, working on a

round bed that revolved and vibrated. At first he was reclusive and frenetic,

powered past dawn by amphetamines and Pepsi-Cola.

In

the early days when he had a bedroom constructed to adjoin his office at the

magazine’s Chicago headquarters, he was known to work 40 hours straight on the

magazine, choosing just the right pose for the Playmate, tinkering with cartoon

captions, and so on. In later years, even after giving up dexedrine, he was

still frenetic, and still fiercely attentive to his magazine.

His

own public playboy persona emerged when he left his wife and children, Christie

and David, in 1959. That year his new syndicated television series, “Playboy’s

Penthouse” (1959-61), put the wiry, intense Hef, pipe in hand, in the nation’s

living rooms. The set recreated his mansion on North State Parkway, rich in

sybaritic amusements, where he greeted entertainers like Tony Bennett, Ella

Fitzgerald and Nat King Cole, and intellectuals and writers like Max Lerner,

Norman Mailer and Alex Haley, while bunches of glamorous young women milled

around. (A later tv show, “Playboy After Dark,” was syndicated 1969 - 1970.)

Friends

described Hef as both charming and shy, even unassuming, and intensely loyal.

“Hef was always big for the girls who got depressed or got in a jam of some

sort,” the artist LeRoy Neiman, one of the magazine’s main illustrators for

more than 50 years, said in an interview in 1999. “He’s a friend. He’s a good

person. I couldn’t cite anything he ever did that was malicious to anybody.”

(For more about Neiman and his invention of Playboy’s Femlin, consult a

review of his book of that name at Opus 215, December 2007.)

At

the same time, Hefner adored celebrity, his and others’. Neiman, who sometimes

lived at the Playboy mansion, said: “It was nothing to breakfast there with

comedians like Mort Sahl, professors, any kind of person who had something on

his mind that was controversial or new. At the parties in the early days, Alex

Haley used to hang around. Tony Curtis and Hugh O’Brian were always there. Mick

Jagger stayed there.”

The

glamour rubbed off on Hefner’s new enterprise, the Playboy Club, which was

crushingly popular when it opened in Chicago in 1960. Dozens more followed. The

waitresses, called bunnies, were trussed in scanty satin suits with cotton

fluffs fastened to their derrières.

One bunny

briefly employed in the New York club would earn Hefner’s lasting enmity.

She

was an impostor, a 28-year-old named Gloria Steinem who was working undercover

for Show magazine. Her article, published in 1963, described exhausting

hours, painfully tight uniforms (in which half-exposed breasts floated on

wadded-up dry cleaner bags) and vulgar customers.

Despite

the titillation of bosomy young women in skimpy outfits bending over to serve

drinks, Playboy Clubs were models of decorum and propriety. Hefner wanted at

all costs to avoid accusations that he was running hookers in the afterhours.

The bunnies were just to look at: rules prohibited them from dating customers.

I visited the New York Club one summer with a Bible-collecting friend of mine,

who was in New York with his pastor. The pastor declined to join us at the

Club, but he could have without the slightest compunction: the place was as

tame as an afternoon tea at an old ladies book club.

A

feminist critic, Susan Brownmiller, debating Hefner on Dick Cavett’s television

talk show, asserted, “The role that you have selected for women is degrading to

women because you choose to see women as sex objects, not as full human

beings.” She continued: “The day you’re willing to come out here with a

cottontail attached to your rear end, then we’ll have equality.”

Hef

had no comment at the time. But he responded in 1970 by ordering an article on

the activists then called “women’s libbers.” In an internal memo, he wrote:

“These chicks are our natural enemy. What I want is a devastating piece that

takes the militant feminists apart. They are unalterably opposed to the

romantic boy-girl society that Playboy promotes.”

The

commissioned article, by Morton Hunt, ran with the headline “Up Against the

Wall, Male Chauvinist Pig.” (The same issue contained an interview with William

F. Buckley Jr., fiction by Isaac Bashevis Singer and an article by a prominent

critic of the Vietnam War, Senator Vance Hartke of Indiana.)

Over

time, some women came to view Playboy with greater acceptance, if not

respect. When “Sex and the City,” the television series about four sexually

adventurous women in New York, premiered in 1998, the lead character played by

Sarah Jessica Parker wore a necklace with the Playboy bunny pendant.

Camille

Paglia was not as alarmed by the Playboy bunny costume as many feminists were.

“Feminists of that period were irate about it — they felt that it reduced women

to animals. It is true it's animal imagery, but a bunny is a child's toy, for

heaven's sake! I think you could criticize the bunny image that Hefner created

by saying it makes a woman juvenile and infantilizes her. But the type of

animal here is a kind of key to Hefner's sensibility because a bunny is utterly

harmless. Multiplying like bunnies: Hefner was making a strange kind of joke about

the entire procreative process. It seems to me like a defense formation —

Hefner turning his Puritan guilts into humor. It suggests that, despite his

bland smile, he may always have suffered from a deep anxiety about sex.

“Hefner

created his own universe of sexuality,” she added, “—where there was nothing

threatening. It's a kind of childlike vision, sanitizing all the complexities

and potential darkness of the sexual impulse.

She

continued: “Hefner's bunnies were a major departure from female mythology,

where women were often portrayed as animals of prey — tigresses and leopards.

Woman as cozy, cuddly bunny is a perfectly legitimate modality of eroticism.

Hefner was good-natured but rather abashed, diffident, and shy. So he recreated

the image of women in palatable and manageable form. I don't see anything

misogynist in that. What I see is a frank acknowledgment of Hefner's fear of

women's actual power.

Hefner

said later that he was perplexed by feminists’ apparent rejection of the

message he had set forth in the Playboy Philosophy. “We are in the process of

acquiring a new moral maturity and honesty,” he wrote in one installment, “in

which man’s body, mind and soul are in harmony rather than in conflict.”

In

1955, the magazine published author Charles Beaumont's, "The Crooked

Man," a short story about problems a straight man faces in a fictional

homosexual society. This created a public outcry, to which Hef's response was,

"If it was wrong to persecute heterosexuals in a homosexual society, then

the reverse was wrong, too."

Of

Americans’ fright of anything “unsuitable for children,” he said, “Instead of

raising children in an adult world, with adult tastes, interests and opinions

prevailing, we prefer to live much of our lives in a make-believe children’s

world.”

Many,

of course, questioned whether Playboy’s outlook could be described as

adult.

Harvey

G. Cox Jr., the Harvard theologian, called it “basically antisexual.” In 1961,

in the journal Christianity and Crisis, Cox wrote: “Playboy and

its less successful imitators are not ‘sex magazines’ at all. They dilute and

dissipate authentic sexuality by reducing it to an accessory, by keeping it at

a safe distance.”

In

a 1955 television interview, a frowning Mike Wallace asked Hefner: “Isn’t that

really what you’re selling? A high-class dirty book?”

Such

scolding sounded quaint by the time crasser competitors like Penthouse and Hustler appeared in the 1960s and 1970s. Playboy began showing pubic

hair on its models, while the others doubled the dare with features on kinkier

sexual tastes and close-up gynecological photos. Hef would decide, after

furious debate among the staff, not to compete further.

Playboy

Enterprises still prospered, and in 1971 went public to finance resorts in

Jamaica, Lake Geneva, Wis., and Great Gorge, N.J., and gambling casinos in

London and the Bahamas.

OUR HODGE-PODGE

HISTORY of Hefner and Playboy cries out for a Miscellany Department, so

here it is—:

In

1963, an issue of Playboy featured nude pictures of American actress

Jayne Mansfield. It was deemed too vulgar and obscene, which led to Hefner's

arrest. The problem was one photograph that showed naked Mansfield in bed with

a man. But he was fully clothed and seated on the bed, not so much “in it” with

Mansfield as just “on it.” Charges were dropped against Hef after the jury was

unable to reach a verdict.

In

1970, Playboy unveiled its braille version, becoming the first men's

magazine for the blind. I suppose we could manage a joke here about the braille

version enabling men to feel the Playmates. But it wouldn’t be a good joke.

The November 1972 issue of Playboy was

its best-selling, with 7,161,561 copies sold to date. It featured Pam Rawlings

on the cover, and the centerfold featured Lena Söderberg, whose face in the

photo was used in image processing research in 1973 ff. Commonly referred to in

computer circles as the “Lena,” the face eventually laid the foundation for

the JPEG and MPEG standards. In the ensuing decades, reported th Carnegie

Mellon University’s School of Compter Science, “no image has been more

important in the history of imaging and electronic communications, and today

the mysterious ‘Lena’ is considered the First Lady of the Internet.”

Pam

Anderson, the model and former "Baywatch" star, has graced the cover

of Playboy more than any other model, a record 14 times, starting with

the October 1989 issue.

Hefner's name is mentioned a couple of

times in the Guinness Book of World Records. The first mention is for

having the longest career as an editor in chief of the same magazine, and the

second mention is for possessing the largest collection of personal scrapbooks.

In over 3,000 leather-bound books, Hef kept a detailed account of everything

that happened behind the doors of the Playboy Mansion, including photos of its

very famous visitors as well as copies of every tweet and memo he ever sent,

and he recorded with pictures and prose his personal history since he was in

high school. He spent his Saturdays in a special scrapbooking room, and he had

a full-time scrapbook staff member to assist in creating and maintaining the

scrapbooks.

By 1961, the Chicago Playboy Club had

132,000 members, making it the busiest club in the world.

But

what about mob influence in the clubs? In her book Playboy Laughs, Patty

Farmer explains why the mob stayed away:

“The

two main clubs were in Chicago and New York, but if you owned a nightclub in

almost any city in the U.S. at that time, the mob was there in some form or

another. Hef did have members of a certain family sit down in his office and

say they really thought they should do some business together. Hef, in his laid

back manner, said: ‘I have the eyes of the Catholic Church and federal and

local government constantly on me. Do you really think I’m the right partner to

be in business with?’ Even though they were mobsters, they were smart enough to

realize it wasn’t anything they wanted to push because they were trying to stay

out of trouble themselves.”

In

1961, when independently owned Playboy Clubs in Miami and New Orleans refused

to admit African American members, Hefner bought back the franchises and issued

a sternly worded memorandum: “We are outspoken foes of segregation [and] we are

actively involved in the fight to see the end of all racial inequalities in our

time,” he wrote.

In

1980, Hefner was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. His star is

adorned with the image of a tv set, with rabbit ears.

A dedicated philanthropist, Hefner had

donated generously to charities and organizations over the years through the

Hugh M. Hefner Foundation. On February 12, 2012, he was honored as

"Humanitarian of the Year" by the organization Angelwish, which works

toward improving the lives of children living with chronic illnesses. Hefner is

also a strong advocate of same-sex marriage. And almost any avant garde

attitude about sex, race, you name it: Hef was for it.

At

the Playboy Mansion — first in Chicago and later in Los Angeles — Hef held

glittering parties that attracted Hollywood celebrities and scores of women who

eagerly shed their clothes. Outside the front door, a sign read, “Si non

oscillas, noli tintinnare” — a Latin phrase loosely translated as “If you don’t

swing, don’t ring.”

ANATOMY OF THE

PLAYBOY BUSINESS

Licensing: This is Playboy's

biggest revenue driver. The company says a deal with global fragrance giant

Coty tops $100 million in annual wholesale sales. Through a partnership with

Handong United and Bally's, Playboy distributes clothing, footwear and fashion

accessories globally, with more than a third of global revenue coming from

China. Playboy is mulling a $25 million-$50 million capital raise for a renewed

push into lingerie and swimwear.

Magazine: Founded in 1953, Playboy peaked with a circulation of 5.6 million in the

1970s and now distributes about 450,000 copies of each issue.

Television: After years of third-party management, Playboy Television and other video

assets are being managed in-house. This year, more than 20 series, including

some made by Playboy, were produced for the X-rated network, which is seen in

60-plus countries.

Digital: Playboy.com attracts roughly 4 million monthly unique visitors. (By comparison,

Esquire.com has 7 million.)

Nightclub

and Events: This year, 2017, a Playboy Club will open in New York,

joining properties in London, Hanoi, Bangkok and multiple cities in India. The

Playboy Jazz Festival, held at the Hollywood Bowl since 1979, sells about

35,000 tickets each year.

THE MAGAZINE

REACHED THE HEIGHT OF ITS POPULARITY in the early 1970s, with a circulation of

7 million (somewhat at odds with the number just cited). Hefner’s personal

fortune at the time was estimated at more than $200 million, and he traveled in

a black jetliner with the bunny-head symbol painted on the tail. The Harvard

Business School studied his formula for success.

The

heady mood broke in 1974, when Hefner’s longtime personal assistant, Bobbie

Arnstein, committed suicide. Arnstein had just been convicted of conspiracy to

distribute cocaine, and Hefner said bitterly that investigators had hounded her

to set him up.

The

1980s brought a huge retrenchment for Playboy. The company lost its London

casinos in 1981 for gambling violations and was denied a gambling license in

Atlantic City, partly because of reports that Hefner had been involved in

bribing New York officials for a club license 20 years earlier.

The

company shed its resorts and record division and sold Oui magazine, a

more explicit but less successful version of Playboy, while the

flagship’s circulation plunged. The Playboy Building in Chicago, its

rabbit-head beacon illuminating Michigan Avenue, was also sold, as was the

corporate jet with built-in discothèque. Bunnies were going the way of go-go

dancers, and the Playboy Clubs closed, the last of them, in 1991. They’ve since

experienced a resurgence; see the section above.

Hefner

relied more and more on his daughter, Christie, named company president in 1982

and then chief executive, a position she held until 2009. Hefner suffered a

stroke in 1985, but he recovered and remained editor-in-chief of Playboy, choosing the centerfold models, writing captions and tending to detail with an

intensity that led his staff to call him “the world’s wealthiest copy editor.”

AFTER HIS

DIVORCE FROM HIS FIRST WIFE, Hefner often said he would never marry again. He

had a long relationship in the 1970s and 1980s with onetime Playmate Barbi

Benton, but they did not marry. But then in 1989, Hef married again, saying he

had rethought Woody Allen’s line that “marriage is the death of hope.”

His

second wife was Kimberley Conrad, the 1989 Playmate of the Year, 38 years his

junior. They had two sons: Marston Glenn, born in 1990, and Cooper Bradford,

born in 1991. Cooper would assume control of the magazine and its empire in

2015.

The

couple divorced in 2010, and Hefner plowed into his work, including the editing

of The Century of Sex, a Playboy book. When a New York Times interviewer

later prodded him about the rewards of marriage, he replied, “Unfortunately,

they come from other women.” Meanwhile, to widespread snickering, he became a

cheerleader for viagra, telling a British journalist, “It is as close as anyone

can imagine to the fountain of youth.”

The

re-emerged Hef reveled in the new century. In 2005 he began appearing on

television on the E! channel reality show “The Girls Next Door,” which featured

his girlfriends who lived in the Mansion at Hef’s beck and call. It was fairly

tame stuff: Hef’s onscreen role consisted mostly of peering in while his three

young, blonde girlfriends planned adventures at the Mansion. When the three

original “Girls Next Door” went their separate ways after five seasons, Hef

replaced them with three others, also young and blonde — and shortly afterward

asked one of them, Crystal Harris, to marry him.

Five

days before 85-year old Hef was to marry the 25-year-old Harris in June 2011 —

the wedding was to have been filmed by the Lifetime cable channel as a reality

special — the bride called it off. Hefner, by this time a man of the

21st-century media, announced on Twitter, “Crystal has had a change of heart.”

Reportedly,

her change of heart had been prompted by her husband-to-be, who told her he

intended to continue to date and have sex with other women—just as he had when

she had been one of his in-house trio of love-birds.

Hef

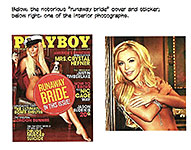

the magazine publisher was able to make this heart-breaking event a

circulation-builder. He turned it into a kind of self-deprecating joke.

Crystal

was scheduled to be featured inside and outside of Playboy’s July issue,

which would hit the stands just about the time of their scheduled June wedding.

Next to a picture of a nearly naked Crystal, the cover copy read: “American’s

Princess: Introducing Mrs. Crystal Hefner.”

Hef

arranged to have a sticker slapped on the cover over much of Crystal’s body.

The bright red sticker read: “Runaway Bride In This Issue!”

But

presumably Crystal had another change of heart—or Hef did— and the two married

on New Year’s Eve 2012. On their first anniversary, Hefner tweeted to his 1.4

million followers, “It’s good to be in love.”

Another

of the “Girls Next Door,” Holly Madison, offered a depressing version of the

girls’ life in the Playboy Mansion in a 2015 tell-all book. In the years when

Hef was calling her his “No.1 Girlfriend,” she wrote in Down the Rabbit

Hole, she endured a dysfunctional household of petty rules, allowances,

quarrels and backstabbing, all directed by an emotionally manipulative old man.

Her narrative is catty and snippy: no one ever “speaks” in the book: they

“sneer” or “spit” or “jeer” or “bark.”

Through

those years, however, the Playboy brand marched forward. In 2011, Hefner took

Playboy Enterprises  private again. Scott Flanders, after taking over as chief

executive of Playboy Enterprises in 2009, focused on the licensing business,

shrinking the company and raising its profits. The website, cleansed of any

whiff of pornography, enjoyed huge growth, while Hefner, who retained his title

and about 30 percent of the company’s stock, cheerfully tweeted news and

pictures of the many festivities at the Mansion, along with hundreds of

photographs from his past, in the glory decades of the ’60s and ’70s. He also

worked steadily on his scrapbooks. private again. Scott Flanders, after taking over as chief

executive of Playboy Enterprises in 2009, focused on the licensing business,

shrinking the company and raising its profits. The website, cleansed of any

whiff of pornography, enjoyed huge growth, while Hefner, who retained his title

and about 30 percent of the company’s stock, cheerfully tweeted news and

pictures of the many festivities at the Mansion, along with hundreds of

photographs from his past, in the glory decades of the ’60s and ’70s. He also

worked steadily on his scrapbooks.

IN 1971, HEFNER

MOVED FROM CHICAGO to Los Angeles, where he’d bought a Tudor-style mansion for

over $1 million from world-renowned chess player and engineer Louis D. Statham.

Soon outfitted with many of the features of the Windy City manse—plus a grotto

and grounds for a small zoo—the new mansion in Holmby Hills quickly acquired a

notorious reputation as a partying place where celebrities mingled with the

drinking and dancing throng and nubile young women, nearly naked and naked,

threaded their way through the crowd, smiling convivially all the way.

Throughout

his the five decades of life in the LA Playboy Mansion, Hef housed numerous

young blonde women in the building at the same time, including the first stars

of the E! reality tv series “Girls Next Door,” Holly Madison, Bridget Marquardt

and Kendra Wilkinson. The Girlfriends, as this bevy was called, usually

numbered three but at times was as populous as five or six. The membership

constantly changed as Girlfriends left and were replaced by fresh faces. (“Who

could forget,” Bill Zehme asks, “that name-rhyming trio made up of the

exquisite Brande Roderick and the wily twins Mandy and Sandy Bentley

[1998-90]?”)

Said

Hef: “I went to the multiple-girlfriend arrangement because a large number of

them can’t hurt you as much as one can.”

There

were six Girlfriends in December 2003 when Time asked Hefner if he

“really” slept with all six of them. Said Hef: “It’s just like an ordinary

relationship times six. A lot of single guys or women date more than one

person. The only thing that’s different here is we do whatever we’re going to

do together. It’s very nice, makes it like a little family.”

Group

sex, in other words—as we’ll see anon.

Holly

Madison lived in the Mansion for about seven years, most of the time as the

“No.1 Girlfriend.” As the first among equals, she didn’t have a bedroom of her

own as the others did: she stayed in Hef’s bedroom.

The

six-season E! reality series supposedly documented the lives of these playmates

and their relationship with Hefner inside the Mansion. The documentation was,

however, discretely incomplete. It left out the sex part.

It

also left out the regimentation. Hef’s leisure life rigidly followed the same

pattern, week after week, without deviation except when it was interrupted by

the convening of a large party on the premises—at Hollowe’en, for instance. The

rest of the time, the week broke down as follows:

◆ Monday, according to Holly Madison, was Manly Night. Hef

had guy friends over for a buffet dinner and a movie in the Mansion’s screening

room.

◆ Tuesday was Family Night. Hef’s second wife, Kimberly

Conrad, and his two sons by her (who for years until Cooper was 18 lived next

door in a house Hefner had purchased for them) would spend the evening

together.

◆ Wednesday and Friday were Club Nights, when the

Girlfriends went off with Hef for an evening of drinking and dancing at local

exclusive clubs, ending in Hef’s bedroom for ritual fucking.

◆ Thursday was Off Night for the Girlfriends (like Monday

and Tuesday).

◆ Saturday was a buffet dinner and a movie with Hef.

◆ Sunday was Fun in the Sun—a pool party during the day and

dinner and a movie at night.

Sex

nights, Wednesdays and Fridays, began about 10 o’clock when the Girlfriends—and

other female visitors, like Playmates who might be there for a shoot—would

climb into a limousine with Hef and go to one of his two favorite nightclubs,

where they all sat in a roped-off reserved section. They drank and danced until

about midnight, when Hef would take his little blue viagra pill. From then on,

the clock managed events: they had to leave the club in time to get back to the

Mansion just when the viagra took effect (about an hour after it is taken). If

they arrived too early—or too late—Hef would not be able to perform.

Upon

arrival at the Mansion, the Girlfriends went to their rooms and changed into

something more comfortable. Then they went to Hef’s bedroom where he awaited

them. If one of them didn’t want to have sex with Hef that night, she wore her

panties—a signal that it was the time of her period (“We had periods that went

on for months,” said one of the girls, “and when that excuse got old, we would

suddenly get yeast infections”) or that she otherwise didn’t feel up to

screwing. According to Isabella St. James, who wrote Bunny Tales about

Girlfriend life in the Playboy Mansion, Girlfriends were not “required” to have

sex with Hef: he always presented the recreational opportunity as optional. But

he encouraged it. And since the other Girlfriends all piled in, group

psychology took over and participation was almost always universal.

The

bedroom and the bed were large. The walls were adorned with photographs of

Playmates and Girlfriends, and there were two large tv projection screens

side-by-side. During sex night, pornographic movies were shown throughout the

festivities.

Hef

lay naked on his back on the bed and lathered himself with baby oil while the

Girlfriends joked and danced and drank and smoked weed. In her memoir, Sliding

Into Home, Kendra Wilkinson admitted that “I had to be very drunk or smoke

lots of weed to survive those nights—there was no way around it.” St. James

detailed what happened next.

“Holly

would start off the festivities by orally pleasuring Hef until he became erect.

... As soon as she got him hard, some new girl would be ready to screw him. ...

Hef was always on his back, so whoever screwed him would have to get on top.”

I’m

using the term “screw” here rather than St. James’ more delicate “have sex

with” because the evening was so rigidly structured and the act with Hef was so

mechanical that “sex” scarcely entered into the proceedings. Screwing was what

they were doing.

St.

James continues: “Even though Hef might screw three or four, or sometimes even

more, girls, it is important to realize that each of these experiences was

brief.”

Madison,

who recorded only her first experience in the bedroom, said, “Much to my

surprise, my turn was over just as quickly as it started.”

Each

girl straddled Hef’s cock, bounced a couple of times, and got off to let the

next girl have her turn. A few seconds with each girl—maybe a minute at most.

Wham, bam—and then it was on to the next girl.

“Brief

and uneventful,” said St. James, “—it’s almost as if he is doing it for show

and for his ego. It is all an illusion; an illusion that he is still a

swinger, a man with many women in his bed, a crazy orgiastic experience. It is

just not so in reality. ... Hef is trying to live out this fantasy he has been

selling to people since 1954. He wants to live up to the Playboy image he

created and the expectations people have of him; it wouldn’t be as cool if he

slept with only one girl once every few months, like all the other eighty-year-olds.”

Most

disappointing of all, there was no sense of intimacy. “There was no alone time

with Hef,” St. James said, “—therefore, nothing felt personal. And the sex,

more than anything, was impersonal. ... We never really kissed Hef either. ...”

So

why did the girls do it? At least two of them—the two whose memoirs I’ve

read—explained that while they were not necessarily passionately in love with

Hefner, they did love him, in the fond way that a young person might love an

older but kind and thoughtful person. (Although he was not always kind and

thoughtful: Madison detailed instances in which Hef’s desire to control

everything turned him into a tyrant.)

And

there were perks. Visits to the hair-dresser were paid for by Hef. So was

whatever plastic surgery the girls wanted—nose jobs, breast implants. Each of

the Girlfriends got a $1,000 weekly allowance. And some of the girls had gone

on into show business after their initiation with Hefner.

After

being straddled by three to six women, Hef treated them all to the grand

finale: “Hef masturbated while watching the porn on the screens in front of

him,” said St. James. “I never saw him come while screwing anyone; he always masturbated. And it was always the same: too much baby oil, his hand, and the

visual support of porn or the better alternative of a couple of the girls

making out. It was all over with the loud, dramatic ‘God damn it ... wow!’”

that he blurted out as he ejaculated.

“Lines

we knew so well,” said St. James, “that we would laughingly mimic them exactly

when they were being voiced.”

Supremely

fitting, somehow, that the man who produced the material that abetted

adolescent masturbatory exercises worldwide for at least three generations

would find sexual satisfaction in exactly the practice his magazine had so

successfully encouraged.

FOR DECADES,

THE AGELESS HEFNER embodied the “Playboy lifestyle” as the pajama-clad sybarite

who worked from his bed, threw lavish parties and inhabited the Playboy Mansion

with an ever-changing harem of well-turned young beauties. In January 2016, the

Mansion was sold for $100 million (or maybe it was $200 million; sources

differ) on the condition that Hefner could continue to stay there until he

died. The purchaser was Daren Metropoulos, co-owner of Twinkies maker Hostess.

Hefner

was buried in Westwood Memorial Park in Los Angeles, where he had bought the

mausoleum drawer next to Marilyn Monroe, who held a special place in Hef’s

heart because she was the first model to appear in his magazine. Hef clearly

intended to continue his relationship with the actress even after his death.

Asked

if there is anything of lasting value in Hefner's legacy, Camille Paglia took a

long view: “We can see that what has completely vanished is what Hefner

espoused and represented — the art of seduction, where a man, behaving in a

courtly, polite and respectful manner, pursues a woman and gives her the time

and the grace and the space to make a decision of consent or not. Hefner's

passing makes one remember an era when a man would ask a woman on a real date —

inviting her to his apartment for some great music on a cutting-edge stereo

system (Playboy was always talking about the best new electronics!) —

and treating her to fine cocktails and a wonderful, relaxing time. Sex would

emerge out of conversation and flirtation as a pleasurable mutual experience.

So now when we look back at Hefner, we see a moment when there was a fleeting

vision of a sophisticated sexuality that was integrated with all of our other

aesthetic and sensory responses.

“Instead,”

she went on, “what we have today, after Playboy declined and finally

disappeared off the cultural map, is the coarse, juvenile anarchy of college

binge drinking, fraternity keg parties where undeveloped adolescent boys

clumsily lunge toward naive girls who are barely dressed in tiny miniskirts and

don't know what the hell they want from life. What possible romance or intrigue

or sexual mystique could survive such a vulgar and debased environment as

today's residential campus social life?

“Today's

hook-up culture,” she went on, “— which is the ultimate product of my

generation's sexual  revolution—seems markedly disillusioning in how it has

reduced sex to male needs, to the general male desire for

wham-bam-thank-you-ma'am efficiency, with no commitment afterwards. We're in a

period of great sexual confusion and rancorright now. The sexes are very wary

of each other. There's no pressure on men to marry because they can get sex

very easily in other ways. revolution—seems markedly disillusioning in how it has

reduced sex to male needs, to the general male desire for

wham-bam-thank-you-ma'am efficiency, with no commitment afterwards. We're in a

period of great sexual confusion and rancorright now. The sexes are very wary

of each other. There's no pressure on men to marry because they can get sex

very easily in other ways.

“The

sizzle of sex seems gone,” Paglia concluded. “What Hefner's death forces us to

recognize is that there is very little glamour and certainly no mystery or

intrigue left to sex for most young people. Which means young women do not know

how to become women. And sex has become just another physical urge that can be

satisfied like putting coins into a Coke machine.”

HEF’S SON

COOPER EVENTUALLY BROUGHT BACK full-page color cartoons in Playboy; they

were missing for only about a year. But the art of the “new” Playboy’s cartoons,

compared to the graphic tradition Hef had so carefully established and

maintained for over sixty years, was pitifully lame. In place of the

exuberantly water-colored imagery of yore we had only outline drawings,

unimaginatively colored. Jack Cole, whose water-colors had established the

magazine’s cartoon tradition, is doubtless turning over in his grave. Ditto

Hef.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |