PLAYBOY’S

FIRST CARTOONIST (September 2008)

What

Really Happened When Hugh M. Hefner Was Editor of Shaft

My

experience with Playboy is

almost as long as Hugh Hefner’s but not nearly as rewarding

either financially or recreationally. My first encounter with the

magazine was in Jerry’s, a downtown Denver newsstand, in

approximately June 1955, when Hef’s revolution in American

sexual mores had been going on for only about 18 months. My friend

Gary had dragged me, willingly, into Jerry’s to show me this

new publishing phenomenon. “Here,” he said, plucking the

August issue off the rack and thrusting it into my hands, “—what

do you think of this?” At the age of approximately eighteen, I

was not ready to do much thinking in the vicinity of Playboy. And I didn’t. Emotion was in complete control.

Fear, mainly. After thumbing furtively through a few pages of the

magazine, I quickly put it back on the rack, and Gary and I left

Jerry’s as quickly as we could, hoping to escape before we

attracted the attention of the proprietor, who, we imagined, would

doubtless disapprove of two adolescents giving their hormones a rush

in public. Despite the incomprehensible brevity of my introduction, I

remember vividly the cover of the first issue of Playboy I ever saw, described, in The

Playboy Book as having “achieved

notoriety when a strategically placed strand of seaweed mysteriously

slipped out of place sometime during the printing process.”

Here is the incriminating evidence, a copy of the salacious cover

itself.

That fall, now a freshman in college and free of any remnant of adult supervision whatsoever, I purchased my next issue of Playboy and was therefore able to inspect it at somewhat greater leisure. In those days, Playboy was widely celebrated as a “science-fiction magazine”: the pages devoted to hi-fi phonograph record players and other technological advances for the modern bachelor apartment comprised the “science” section; the rest of the magazine, went the quip, was “fiction.” Apart from rejoicing in the generous display of barenekidwimmin in the “fiction” department, I was impressed with the cartoons. Lots of them, and some in full color, like paintings. As a neophyte cartoonist, I was smitten. Admiring the cartoons became almost as consuming a preoccupation with every new issue of Playboy as admiring centerfolds and other evidences of nakedness. And in the months that Jack Cole was allotted several pages in order to treat some subject in depth, the airbrushed photos of female embonpoint took second place on my agenda. Well, almost second place.

My next notable experience with Playboy was in the fall of 1958, when, as a campus cartoonist attending a college journalism convention in Chicago, I had played hooky one afternoon to take some of my cartoons to the magazine's headquarters, then at 232 East Ohio Street. The building was one of those shotgun structures—narrow across the frontage but burrowing deep into the lot beyond. I walked into the first floor reception area, stated my business to a striking-looking blonde lady at the desk, and was directed to an elevator that would take me to the fourth floor. The elevator stopped at the second and third floors, and each time the door opened, I was treated to another blonde vision at a reception desk.

When

I told the blonde at the fourth floor desk my errand, she summoned

someone by phone. Another blonde appeared, looked over my drawings,

and then asked me to wait. I did. She returned shortly and escorted

me to the office of Jerry White, one of two assistants to art

director Arthur Paul. White, dark-haired, bearded, looked at my

drawings, made sympathetic sounds, and told me to keep at it because

they were looking for younger cartoonists who could bring to the

magazine a somewhat less jaded view than might be found in the work

of such mature cartoonists as Gardner Rea,

who was then in his mid-sixties. I remembered he mentioned Rea

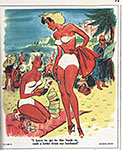

specifically.  The cartoon below Rea’s, just here, at your elbow, is one of

the cartoons I had in my portfolio. This is a copy. The original,

which I’ve lost track of years ago, was drawn in brown pencil,

enhanced with brush-applied black ink for some of the more crucial

delineation. I thought it arty enough for Playboy. White didn’t agree. I left with my portfolio

intact, my sales record unblemished.

The cartoon below Rea’s, just here, at your elbow, is one of

the cartoons I had in my portfolio. This is a copy. The original,

which I’ve lost track of years ago, was drawn in brown pencil,

enhanced with brush-applied black ink for some of the more crucial

delineation. I thought it arty enough for Playboy. White didn’t agree. I left with my portfolio

intact, my sales record unblemished.

Due to the press of other adventures, I didn't try selling to Playboy again for two decades. In the late 1970s, I once again forayed out into the magazine cartoon market, alone and unafraid. My dubious ability to limn the curvaceous gender stimulated my sales to “men’s magazines,” so before long, I gave up trying to sell in the so-called “general” market (where any subject, as long as it was fully clothed, might sell—except, apparently, my cartoons) and concentrated on the “girlie” market (for which almost every girlie I drew was entirely unencumbered, the less, the better). I sold fairly well compared to the rumored industry standard—ten percent sales. I did better than that—except at Playboy. Following the custom of the profession, I mailed every batch (of 10-20 cartoons each) to every possible market, beginning with the highest paying and working my way down to the sleaziest of them all, Sex to Sexy, which paid five bucks a cartoon. I always inaugurated every batch by sending it to Playboy. Alas, nothing ever sold there. And today, my sales record at Hef’s magazine remains entirely virginal.

Cartoons have always been important in Playboy. In introducing one of the magazine’s several book celebrations of its fiftieth anniversary, Playboy 50 Years: The Cartoons, Hefner, the magazine's septuagenarian founder (still appearing in photographs, as always, grinning like the cat who's munched a particularly bountiful canary, the grin, in recent years, looking suspiciously frozen by Botox), says: "I once commented that without the centerfold, Playboy would be just another literary magazine. The same can be said for the cartoons. Playboy's visual humor has helped to define the magazine." I agree.

No

one, thumbing his way through any issue of the magazine, could doubt

that its cartoons have done much to establish the essential character

of the publication. From the start, Hefner set out to assemble a

stable of cartoonists whose work would be distinctive, unique, in

magazine cartooning and would appear almost exclusively in his

magazine. For this reason, he shunned

one of that day's most well-known cartooners of the feminine

form—Michael Berry. Berry's

flaxine-haired statuesque but vacuous beauties were everywhere in

magazines, advertisements as well as cartoons. And Hef (as he has

called himself for several generations) wanted a new "look,"

something not already on display everywhere. Berry, alas, was

everywhere.

In my view, Hef found what he hoped for in the luminous watercolors of Jack Cole. Cole's work started to appear in the fifth issue of Playboy, and his painterly excellence established a standard for Playboy cartoons. Cole, as every cartoon fanaddict knows, killed himself in the summer of 1958, but by then, his cartoons with their fleshy, zaftig cuties had set the mold. Not that Playboy cartoonists imitate Cole: they most emphatically do not. But they approach their work with an artist's color palette tools, not a cartoonist's pen and ink, and in that, they follow in Cole's footsteps. (A great deal more about Cole, including several of his cartoons, can be found in our Hindsight piece for November 2003.)

By the time Playboy had been published for a decade, it was one of the last redoubts of single-panel gag cartooning in America. The New Yorker is the other. All the other great magazine cartoon venues— The Saturday Evening Post, Look, Collier's, even True—had expired, leaving legions of magazine gag cartoonists scraping eraser crumbs off their drawingboards for sustenance. Hefner was not among them. And he was probably living on caviar as well as Pepsis, his famous drink of choice, not eraser crumbs. But if he’d achieved his first and fondly pursued professional desire, he would have been a cartoonist. Hef is a lifelong frustrated cartoonist, which may, in and of itself, account for the importance he has always attached to cartoons in the magazine.

All through high school in his hometown Chicago, Hefner drew cartoons. Between the ages of twelve and fourteen, as Russell Miller tells us in Bunny: The Real Story of Playboy, the youth produced more than seventy comic strips and gathered them together in bound volumes. At sixteen, he began his "Comic Autobiography," which chronicled, in cartoon form, his life through graduation from Steinmetz High School in 1944.

Knowing he would likely be drafted into the army, Hefner enlisted, and as soon as his superiors learned of his typing skills, he was assigned as company clerk and never made it overseas. He spent the remaining years of World War II writing letters home to his paramour, Mildred "Millie" Williams, and drawing cartoons for the base newspaper. Discharged in March 1946, Hef knocked around Chicago for a few months, and then, taking advantage of the G.I. bill, he enrolled that fall in the University of Illinois, where Millie had been in attendance since high school.

Frank Brady in his unauthorized biography, Hefner, says that while at college, Hef started a campus humor magazine called Shaft. But that's not true. Shaft, an off-campus publication, was launched in February 1947 by three other ex-G.I.s. John Davenport, Octavio Jordan, and Charlie Brown had been classmates in a California high school before the War and, until the hostilities commenced, had worked in newspapers and magazines, Davenport and Brown as reporters, Jordan as a cartoonist.

After their escape from the military early in the post-war period, the trio converged on the campus at Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, and soon, having "run out of war stories," they decided to publish what they called "a tabloid magazine." They named it Shaft, in remembrance, doubtless, of their military careers during which they had observed that all enlisted men routinely got it. Among their first contributions was a piece on sports by Gene Shalit, who soon became the publication's managing editor. "Managing editor" was, to this bunch, the top rung of the editorial ladder, the same, in other words, as "editor."

Shaft was successful. In June with No. 4, it ceased being a tabloid newspaper and became a saddle-stitched magazine. And with the next issue, in October, it was making use of a convenient service offered by the Camel and Chesterfield cigarette cartel. Without charge, the tobacco barons provided campus magazines all across the nation with slick cover stock, thereby enhancing the quality of the publications while also reducing their production costs. In exchange, the Camelfield folks got free advertising. The cover stock came with already imprinted full-page, full-color ads for Camelfield cigarettes on what would become the back and inside front covers of the magazine.

Hef's debut as a cartoonist for the magazine had occurred in the previous issue of Shaft, its third, published in April. His contributions were a single-panel cartoon and a half-page montage of comic commentary entitled "Our Answer to the Campus Female Shortage." His first full-pager appeared in the June issue. In the November issue, Hef's first (and only) unclothed cartoon cutie surfaced. Hef, we may say with confidence, was not Cole. No matter: he also did covers for the December and January issues. The feminine form, however, was not the subject of either.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The next issue, Volume 2, Number 1 dated February 1948, was the magazine's "first anniversary issue." Celebrating a full year of publishing, it was markedly different than any of its predecessors. And it was the one and only issue edited by Hefner.

In retrospect, this issue of Shaft is notable because it is an incipient Playboy. The cover is not, as it usually was, a cartoon: instead, it is a photograph of a pretty girl—a girl modestly attired in a dress that bares her shoulders and back but is gathered in front just below her chin. No decolletage whatsoever.

She's Carol "Candy" Cannon, "Shaft's Co-ed of the Month," a perfect incarnation of “the girl next door” to come. About this early manifestation, Hef writes: "No movie star this, just an average, run-of-the-mill coed at dear old Illinois." This discreet phantom of Hefner's decorous heavy breathing would, in five years, be reincarnated, but this time, without raiment.

The other remarkable thing about the only issue of the Shaft that Hef edited is that his editorial reveals his thinking on sexual matters already firmly in place—or, as you might say, his arrested development fully arrested. And in that, he was in perfect step with the rest of American manhood. Here's the whole thing:

"Sort of a personal retaliation, my become editor of Shaft. The first time this journalistic abortion printed my name, they misspelled it. [He was listed in the June 1947 issue as "Heff," with two ef's.]

"The other day I was thumbing thru what may be 1948's most important book— Sexual Behavior in the Human Male by Alfred C. Kinsey, professor of zoology at Indiana University. This 700-page volume is the first thorough examination of American sex behavior and attitudes—the result of nine years of study, during which Dr. Kinsey and his associates interviewed nearly 12,000 men. After considering this evidence, '48 magazine concluded: If American law were rigidly enforced, ninety-five percent of all men and boys would be jailed as sex offenders.

"What about college men? Well, as a group, they are decidedly less promiscuous than the average of the male population. They do indulge in more experiences with the girl they intend marrying, however. I don't know how you're making out, but my girl doesn't believe in surveys. [Millie, according to biographer Miller, did not succumb to Hef's amorous pleading until the ensuing summer, when the couple repaired to a motel in Danville thirty-five miles away.]

"We're waiting impatiently for the female study.

"On a serious note—Dr. Kinsey's book disturbs me. Not because I consider the American people overly immoral, but this study makes obvious the lack of understanding and realistic thinking that have gone into the formation of our sex standards and laws. Our moral pretenses, our hypocrisy on matters of sex have led to incalculable frustration, delinquency and unhappiness. One of these days, I'm going to do an editorial on the subject, but for now, we'll leave it to the Soc. classes and bull sessions."

Hefner would devote most of the rest of his life to the "editorial on the subject."

Hef's cartoon in this issue is a full-page, six-panel effort. The next issue is edited by Octavio Jordan, one of the founders. Hef is gone. He disappeared and never appears in the pages of Shaft again.

The caliber of Hefner’s college cartoons may have been small bore, but once he launched Playboy, he proved, over the years, a particularly canny cartoon editor, suggesting modifications and nuances to his cartoonists that most of them—including, for example, Jules Feiffer— regarded as brilliantly insightful.

Hef graduated a year later, in February 1949, two-and-a-half years after enrolling. He spent that spring producing a comic strip which he tried, unsuccessfully, to get syndicated; and he married Millie in June. He cranked out a vast quantity of cartoons over the next couple years while working at various jobs, including a stint writing promotional copy for Esquire magazine. In the winter of 1950-51, he cobbled together a paperback book of his cartoons about Chicago, That Toddlin' Town.

He was able, eventually, to dispose of all the books, flogging them in person to bookstores and newsstands. Hef was a hard-working salesman on his own behalf. He talked himself onto a local tv talk show, convinced a bookstore on South Michigan to put a display of his original cartoons in the window, and, later, after he and Millie set up housekeeping in their own apartment in 1952 (they'd been living in his parents' home), was able to persuade the Chicago Daily News to do a feature on the apartment, "How a Cartoonist Lives."

About Hef's cartoons in That Toddlin' Town, Miller writes: "They were crudely drawn and not particularly subtle (one man to another, passing a girl with her skirt blown up around her waist revealing her garters: 'I've really been looking forward to the chance to see the Windy City.')" Judging from the evidence at hand, Miller's assessment is accurate to a fault.

Esquire moved its offices to New York City in early

1952, and Hefner stayed in Chicago, finding a variety of other

employments (including promotion manager for a line of nudist

magazines and, incongruously, circulation manager of a magazine

called Children's Activities),

but by the fall of 1953, he was deeply engrossed in preparing the

first copy of the magazine for men that he initially called Stag

Party. It appeared on newsstands as Playboy in November (without a cover date so that it

could stay on the stands until it sold out). And a rabbit was its

symbol. Here’s the stag morphing into the rabbit.

One of the recurring advertisements in Shaft had been for an Urbana saloon called Bunny's, the attractions of which were extolled in an ad depicting several running rabbits, as depicted just below the stag/rabbit in this vicinity. But there's probably no connection. Bunny’s, incidentally, is still a landmark dive in a back alley in downtown Urbana. In another coincidence of no particular significance to our story, the January 1949 issue of Shaft —the one that appeared just as Hef was graduating—published a full page comic strip, unsigned (but not by Hefner), entitled Little Often Annie. It depicts the spunky waif dressing up as a grown-up woman, putting on make-up and an uplift bra, and then being attacked by Daddy Warbucks. Harold Gray's perpetually flat-chested adolescent heroine was frequently the subject of such cartoon fantasies, none of which led to a luxurious fully painted comic strip.

Hefner

apparently produced a cartoon or two for the first issues of Playboy.

I haven't seen them in their native haunt, but one, reprinted in this

vicinity, was reportedly on display at a memorial

exhibit of Playboy paraphernalia

in the fall of 2003. It depicts a couple of young men in an art

gallery, contemplating an abstract painting of a nude, and one of the

youths says, enthusiastically, "Man—is she stacked!"

Hef, wandering the exhibit in a reflective mood, came upon this

effusion of his apprenticeship, smiled, and said, "That says it

all."

Yes, it does. And Hef's "all" brings us back to cartooning and its place in the history of Playboy. The artistic skill of the cartoon also reminds us that if Hefner had been a better draftsman, he might have succeeded as a cartoonist and the world would have been deprived of a sexual revolution. We’re the better for his first career failure. Probably. Or not. Freer, less inhibited about sex. But whether our current obsession with sex consumes more or less psychic energy than repressing the urge altogether is, I suppose, debatable. And as long as the debate rages, we’ll not be certain about whether Hef’s revolution has improved our lives or not. Without a doubt, however, cartooning as an artform is more advanced due to Playboy’s influence. And for that, not to mention for the nonce barenekidwimmin, we’re a happier civilization.

FOOTNIT: The foregoing is a modified and somewhat enhanced version of an article I did for my Comicopia column in The Comics Journal, No. 263. More pictures here, and more text, too.