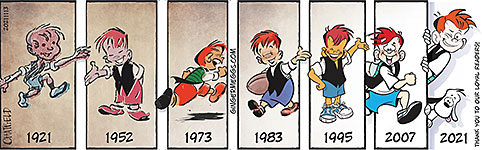

A CENTURY OF GINGER MEGGS

We Celebrate on the Anniversary Date

If you’re reading this on the day it was posted, November 13, you’re seeing Ginger Meggs on his 100th anniversary. Not bad for a cartoon character.

Ginger

Meggs, about the

eponymous red-headed larrikin kid who never gets old, is Australia’s

longest-running comic strip. It’s the fourth longest-running comic strip in the

world—after The Katzenjammer Kids (a Sunday strip that began December

12, 1897), Gasoline Alley (November 24, 1918, Sundays and dailies), and Barney

Google and Snuffy Smith (which began as Barney Google, June 17,

1919, Sundays and dailies).

The prime minister of Australia once called Ginger "Australia's Peter Pan,” saying: "Most of us can recognize in him our own youth, but unlike him, we had to grow up."

Often dubbed Australia’s most-loved comic character, “Ginge,” as the character is affectionately known, was created in 1921 by James C. “Jimmy” Bancks in a strip entitled Us Fellers that, at first, inexplicably, starred a girl.

On October 9, 1921, the Sunday Sun in Sydney introduced a children’s section edited by the author Ethel Turner. Called Sunbeams, it contained a collection of stories, poetry, drawings and letters. And comics.

The latter arrived about a month later, much to Turner’s surprise—a four-page section of “funnies” aimed at the adult readership of the paper. According to Lindsay Foyle’s “More Than A Little Bit of Ginger,” Turner was angered and tried to have the comics removed. She did not succeed.

The idea for the Sunday Sun’s comics had come from Monty Grover, a former editor of the paper. He was fascinated with comics. His two favorites came from America, The Katzenjammer Kids and The Captain and the Kids (which were two versions of the same strip; see Opus 297 for explanation). He was convinced an Australian version of these comics would work “down under” (as they say).

Grover wrote a script for a comic and asked a number of artists to try out to draw it. The concept featured a young girl, Gladsome Gladys, who would accompany a gang of boys on their adventures and extricate them from the various predicaments they got themselves into. The comic was called Us Fellers and was one of the comics introduced to the Sunbeams section on November 13, 1921. The drawings Grover chose to publish were by Jimmy Bancks, who was working for the Bulletin and freelancing cartoons for the Sun.

In that first episode, Ginge was a 10-year-old bit player named Ginger Smith, based, some say, upon Bancks’ childhood friend, Charles Somerville. Within a year, in April 1922, Ginge had acquired a new surname. Nobody knows where, exactly, “Meggs” came from, but there is one attractive theory—namely, that it arrived as a quirk, a sort of linguistic error.

[In

the strip for February 19, 1922, Ginger, trying to catch a ball during a game

of street cricket,trips over a basket of eggs his mum told him to take to the

grocer’s, exclaiming as he does, “Gee Gosh!! Me’Eggs.”

[In

the strip for February 19, 1922, Ginger, trying to catch a ball during a game

of street cricket,trips over a basket of eggs his mum told him to take to the

grocer’s, exclaiming as he does, “Gee Gosh!! Me’Eggs.”

[As often happens with inadvertent but utterances, the picturesque exclamation sticks where it wasn’t intended. Ginge’s mates started calling him “Me’Eggs.”

[The first use of Meggs as Ginge’s surname happens on April 23, 1922, when Gladys talks to his mum, calling her “Mrs. Meggs.” That did it. The redhead was Ginger Meggs thereafter], and, as the irrepressible schoolboy, he soon assumed the lead role in the strip.

|

|

|

Gladys

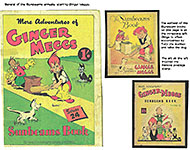

soon disappears forever, and Us Fellers had moved to the front page of Sunbeams and had become a weekly feature. In addition to appearing in the weekly

strip, Ginge was also the featured player in the annual Sunbeams Book: More

Adventures of Ginger Meggs, which was published from 1924 until 1959 (with

the exception of 1952).

From early on, Ginge was joined in his suburban escapades by a muff-wearing girlfriend named Minnie Peters, mates Benny and Ocker, and faithful companions Mike the dog and Tony the monkey. Ginge lives with his Mum and Dad, and his younger brother Dudley in an Australian suburb where he has his adventures with his friends and troubles with his ever-exasperated teachers, school bully Tiger Kelly, and the rival for Minnie’s affections, Eddie Coogan.

Character-driven, the comic appealed to its young and adult readers as much for its narrative bent and comic wit as for its pictures. It has also been persistently attuned to the events, preoccupations and tone of its time, capturing a distinctly Australian spirit and vernacular.

All the aspects of the strip that Bancks had introduced found favor with the readers and Ginger Meggs soon became the most popular boy in Sydney. In Australia, comic strips are associated with newspaper rather than with syndicates, and when Bancks moved his strip to another paper, 80,000 readers followed him. And the paper he left went into bankruptcy.

[By the time Us Fellers changed its Sunday Sun title to Ginger Meggs in November 1939, the strip had reached audiences in England and the United States as well as throughout Australia, and had been translated into French and Spanish for readers of La Presse in Montreal and El Muno in Buenos Aires. Plans to introduce the strip into Europe were largely thwarted by the outbreak of World War II, but it reached the Pacific via Guinea Gold, issued by the Australian Army. On visits overseas, Bancks met fellow cartoonists, including Walt Disney; and in 1948, Ginger appeared on American television.]

In John Ryan’s history of Australian comics, Panel by Panel, Ryan writes about Bancks and Ginge: “Drawing on his own boyhood, Bancks was able to capture all the character, warmth and charm of a typical Australian boy. Ginge’s homespun philosophy and observations on life were a delight and represented an aspect of the strip that was never duplicated by his many imitators. For Ginge, life was meant for playing sport, going to the movies, attending birthday parties or picnics, and for gobbling down ice cream, cakes and fruit. He viewed school homework and helping around the house as diabolical plots intended to deprive him of the real pleasures of living.” And many of those pleasures he arranges himself by playing tricks on his friends.

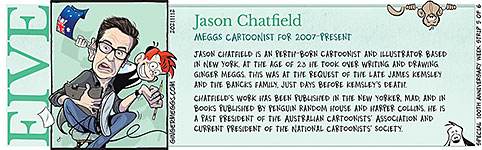

GINGER IS PUBLISHED in 34 countries, including a few U.S. newspapers, and these days, he is written and drawn by Jason Chatfield, 37, an Aussie who moved to the U.S. seven years ago and, unlikely as it seems, is now president of the National Cartoonists Society. He also served a term as president of the Australian Cartoonists’ Association (2010-2012). He’s the youngest cartoonist to hold both presidencies. Chatfield is also a stand-up comedian whenever he can break away from the drawing board and stand up.

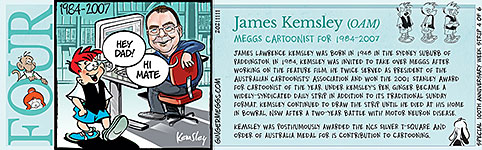

Chatfield is the fifth cartoonist to bring Ginger Meggs to life. His immediate predecessor was James Kemsley, who turned the strip over to Chatfield in 2007 after consulting with the Bancks family, which owns the strip.

|

|

|

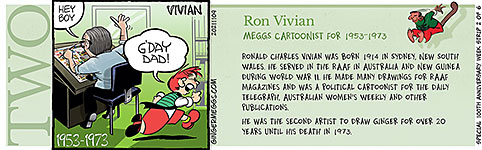

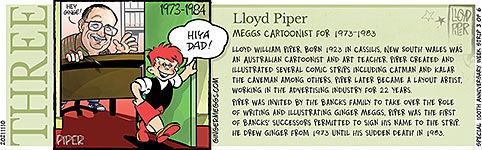

Others who’ve penned Ginge into life are: Ron Vivian (1953-1973), Lloyd Piper (1973-1982) and, of course, Bancks (1921-1952).

Kemsley used to joke about his term on the strip. Bancks unexpectedly died at 63 after 31 years on the strip; Vivian, after 20 years; Piper, after 10. Noting the steady progression downwards in these terms, Kemsley quipped: “So when I was offered the job in 1984, they gave me a 5-year contract.”

He actually completed 23 years, dying in December 2007. He worked harder than any of his predecessors on the strip: he inaugurated the daily Ginger Meggs in 1993.

Kemsley also started the tradition of lettering some wise or ridiculous quip into one of the strip’s panels every day. It began quite innocently: once, Kemsley was out-of-town and would miss the practice session of his cricket team (or some such), so he lettered this “news” in code into the strip for that day, expecting his team-mates to see it and act accordingly.

Thereafter, readers expected (and demanded) these “extras.” And Kemsley complied. [He eventually dubbed them ‘graffiti,’ and he was fond enough of the term to entitle an ensuing collection of strips When You’re Into Graffiti, the Writing’s On the Wall (1998). The graffiti offered a way to connect with readers, who would send in their favorite old quips and witticisms and wait eagerly to see if they’d be included in a subsequent strip. At one point, it was thought that 50% of the readers read Meggs for the graffiti, and the other 50% for the strip itself.

A book celebrating the 100th anniversary was published in May of 2021. Bancks’ Ginger Meggs consists of text stories (“4 brand new stories”) with over 80 illustrations by Chatfield. The stories are by Tristan Bancks, the great great grand nephew of the strip’s creator.

Bancks is a “very successful children’s book author in Australia,” says Chatfield, “and we were very lucky to get him attached to the book project: he already knows all the characters and the Ginger Meggs universe, he’s aware of the Meggs ‘canon’ as it were, and he is very passionate about keeping the character relevant to contemporary readership.”

I have two other Ginger Meggs books: a strip reprint volume, When You’re Into Graffiti (1998), which was given to me by Kemsley years ago when he was in this country attending the National Cartoonists Society Reubens weekend. He made the trip as often as he could to celebrate with his NCS colleagues, as Bancks had done decades earlier. Kemsley was posthumously awarded the NCS Silver T-Square in 2009.

The other is another collection of text stories, illustrated with pictures of Ginge, The Infamous Adventures of Ginger Meggs (1987). The book claims the pictures are by Kemsley, but they look more like Bancks’ style. Chatfield, however, assures me that Kemsley is the illustrator.

“The Infamous Adventure,” Chatfield added, “is the first book I ever read, cover to cover, as a kid in the fifth grade.”

[As the story goes, Chatfield was wasting time in the 5th grade, drawing in the library when he was supposed to be roaming the aisles, picking out a book to read for a book report two weeks later. His teacher, Mrs. Richards, plopped a book down in front of him and said, “If you’re not going to pick one out, I’ll pick one for you. Here!”

[Chatfield let the book sit in his school bag for the next two weeks until the book report was due. Then in true Ginger Meggs style, he got up in front of the class to present his oral book report and made up what the book was about on the spot, based on what he saw on the cover. He got a C+.

Weeks later, he actually opened the book, began reading and couldn’t put it down. He quickly became captivated by the character and gobbled up every strip and book about Ginger he could find.]

Ginge stars in many more books than the ones on my shelf.

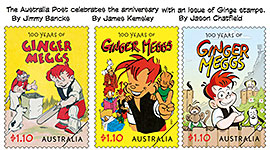

The centenary continues in

two other media. The headline for one, “A Scamp on a Stamp,” announces

Australia Post’s special commemorative Ginger Meggs stamps that feature the

work of three of the cartoonists who have drawn Ginge— Jimmy Bancks, James

Kemsley and Jason Chatfield.

Ginge appears not just in the stamp designs but also in a host of philatelic products, including a minisheet, stamp pack, first day cover, a maxicard set and two stamp and coin covers, housing coins produced by the Royal Australian Mint.

The coins are being sold in two coin sets: one aluminum, one 1/2-ounce silver. The silver set is limited to 5,000 and comes with a certificate of authenticity.

To celebrate the release of the coins, the Mint is offering some lucky Australian the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be drawn into a Ginger Meggs strip: there will be a drawing the winner of which will join Ginge in a future strip.

While all the fuss over a comic strip may seem excessive, it isn’t. Chatfield took the long view when the strip reached its 95th anniversary:

“By virtue of its longevity, the strip has inadvertently become a time capsule of sorts, capturing the zeitgeist of each decade in which it was written. Over each artist’s time working on the strip, you can see little social and historical aspects creeping into the plot.”

Naturally, Chatfield points out, the visuals change: “The interiors and exteriors changed, and the line and word-economy changed with the shrinking of comic strip sizes in newspapers, and the Australian English vernacular changed in the strip to evolve with the readership, particularly under Kemsley’s pen.”

And there are other changes to suit the times. “These days,” Chatfield continued, “no longer is Ginger seen violently fighting or putting on blackface and singing ‘Mammy’ (yes, that actually happened), but he is still likely to be seen enjoying a game of backyard cricket, running his bill cart down Deadman’s Hill, and skipping out on school to go fishing.”

In an effort to make Ginger Meggs a more accurate reflection of Australian culture today, Chatfield introduced three new characters a few years ago. Until they arrived, Chatfield said, “all of the characters were white, and all of their parents were married and happy families living in houses in the suburbs.

“That couldn't be further from the truth of what Australia looks like today,” he went on. “It is one of the most multicultural countries in the southern hemisphere. Many different immigrant cultures have contributed to the evolution of the overarching Australian culture.”

We met one of the new trio in our opening commemorative strip. That’s Rahul Jayasinha at bat. His father was born in Sri Lanka and his mother was born in India. They moved to Australia to start their own medical practice. Rahul loves nothing more than getting out in the sun and playing cricket—and giving Ginge a run for his money.

Both the other two new characters are girls. Gloria Tudehope is a bright and energetic young Aboriginal who loves nothing more than slipping on her running shoes and beating all the boys at races. She has a natural talent for music and can play almost any instrument she picks up.

Penny Chieng is a whip-smart Malaysian Australian girl whose single mother is a family lawyer who has taught Penny she can do anything she wants in life if she applies herself.

“I think Penny is the first

character in the strip to talk about being raised by a single parent,”

Chatfield noted, “—as I was, when I grew up in Australia in the 80/90/2000's.

“I think Penny is the first

character in the strip to talk about being raised by a single parent,”

Chatfield noted, “—as I was, when I grew up in Australia in the 80/90/2000's.

“It took many years for us to very delicately and carefully introduce the new characters,” he continued, “so is not to upset the loyalty of the century-long slew of loyal readers.”

You can meet more of the strip’s characters (and more about these three) at gingermeggs.com/characters

CHATFIELD REMEMBERED inheriting Ginger Meggs. “Kemsley asked me to take over Ginge only a matter of days before he died at 59 of motor neuron disease (ALS). He had been subtly coaching me for years as a mentor and friend when he was the President of the Australian Cartoonists Association (ACA). We would work on the club magazine, Inkspot, together every week; I would design it and have the printing company I worked for print it up and get it shipped out. He taught me all the little 'bits of business' you only learn by 'being' a cartoonist for many years.”

But Chatfield hadn’t been planning a career as a comic strip cartoonist.

He grew up in a little country town called Karratha in the remote northwest of Western Australia, and he did a lot of drawing.

“There was never much to do in this tiny town,” Chatfield said, “so all I did my entire childhood was draw. I didn't play sports or music. I was a weird, quiet kid who carried a clipboard full of paper with me everywhere I went and drew everything I saw.”

He just didn’t think of himself, yet, as a comic strip cartoonist. He just drew a lot.

Said Chatfield: “Making strangers laugh became a lifelong addiction that began when my History teacher asked me to draw a caricature of the school gardener for a retirement present. He paid me $20. He created a monster.

“I started freelancing as a caricaturist straight out of high school,” Chatfield continued, “— while working a hefty slew of dreadful jobs. Eventually, I got a job working 20-hour shifts for a newspaper doing everything from proofreading, subbing, laying out ads, writing stories, editing photos, to creating maps and graphics— oh, and the daily editorial cartoon (if I was still awake). I used to go to sleep at 7 a.m. with newsprint burned into my retinas. I did learn a lot about the newspaper industry, though.”

He was a big fan of Ginger Meggs growing up, and then at the tender age of 19, he met one of his idols and his subsequent cartooning mentor, James Kemsley. Over the years, working together on ACA projects, they became friends.

“Before I took over Ginge,” Chatfield remembered, “I was doing regular newspaper cartoons— political/editorial cartoons and illustrations, and commissioned caricatures. I had not done a comic strip before— hence my surprise when Kems asked me to take over when I was just 23!” [More details, Chatfield said, can be found in an interview from 2007: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OBz_u-h_hWE ]

“To be perfectly honest,” Chatfield went on, “my first response was to say No. I was dealing with crippling impostor syndrome as it was, working as an editorial cartoonist, and I really didn't know if I was up to the job of producing a daily, syndicated comic strip— much less an Australian icon.

“But Kemsley assured me that he had asked all the other cartoonists if they agreed that I was the right pick for the job, and they all shared his view that I was the best choice to carry on the strip.”

So he did.

Said Chatfield: “Kems had

been subtly mentoring me for a long time and assured me that I was ready for

the job. He did say he'd like to work closely with me and train me up to make

sure I knew how to do everything properly as far as the technical side of

things goes, but before we got the chance, he died. I had to figure it out on

my own, in the midst of the grief of losing my friend and mentor. It was a very

bittersweet honor to inherit such a huge legacy. I'm forever grateful to Kems

for the opportunity.

“Kems was himself a bit of a renaissance man,” Chatfield continued. “He hosted a TV show when he was younger, called ‘Cartoon Corner.’ He was Skeeter the Paper Boy and hosted the show on Channel 9 (back when there were only 4 channels). He was also an actor for a long time, and he loved cartooning. He was doing his own strip called Froggin' before he landed the job on Ginger Meggs in 1984. He was working on set of the Ginger Meggs movie in 1982 as a dialect and voice coach at the time.”

I thought it was strange that an Australian should be producing an Australian institution from New York City in the United States, and I asked Chatfield about it.

“Sadly, the opportunity for artists in Australia has dried up,” he said. “I can count the number of comic strip cartoonists in Australia on one hand, and still have fingers left over to give the peace sign. Sadly, there just wasn't anywhere else to go in Australia. I do resent it, truly. I wish the Australian government, and culture, valued cartoons, illustrations and comics more than they do. They'll gladly shell out a lot of money for music festivals and football matches, but when it comes to art, there's just no real career path in Australia. It is a sad reality in 2021.

“The U.S., despite having similar setbacks in the newspaper/publishing industry for traditional cartoonists, has so many more opportunities for cartoonists to make a living in other new and exciting ways. The innovation and creativity here is so much more alive, and to be here on the ground, to be part of the cultural movement while it's happening, is invaluable.”

Chatfield told me that Bancks always wanted Ginger to make it big in the U.S. market (after he saw the popularity of Percy Crosby’s Skippy, about which, see Harv’s Hindsight for April 2004, plus Opuses 333 and 276 for all the scandals).

“Back in the 1930's,” Chatfield said, “Bancks received a substantial offer to move to the United States and bring Ginger with him. Arthur J. Lafave wanted to syndicate the strip but believed it would be easier to market if Bancks was living in America. Bancks went to the U.S. at various times and was a guest on ‘The Tonight Show’ with Johnny Carson.”

Bancks almost made the move, too.

Said Chatfield: “Lafave wanted Bancks to do a daily version of the strip as well as his weekly edition. (At the time Ginger Meggs was just a Sunday strip). Bancks was about to make the move when Eric Baume, then editor of the Sunday Sun, offered Bancks a paycheck so big he had to stay.

“That paycheck made Jimmy Bancks the highest paid artist in the Southern Hemisphere,” Chatfield finished. “But he never got to expand Ginger Meggs' reach to the Americas outside of one or two papers. It wasn't until Kemsley took the reins and signed Ginger to a U.S. syndicate that Ginge made a splash into the bigger international markets.”

We conclude the Rancid Raves celebration of Ginge’s 100th with a selection of the older strips done by Bancks, the father of the feature who could not have known what he started a hundred years ago. We follow those with some special self-portraits of the Ginger Meggs cartoonists that have been resurrected to commemorate the centenary.

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Fitnoot. Jason Chatfield read this posting before it was posted, adding various picturesque anecdotes and correcting a couple erroneous citations. The material he added is set off with brackets, [like this].