FRANQUIN, GASTON LaGAFFE AND DIE LAUGHING

Biography, Book Reviews, and Some History

Mind the Goof!

By Andre Franquin

46 8.5x11-inch pages, color; 2017 Cinebook English translation of Gaston: Gare aux gaffes, paperback, $11.95

I’VE BEEN WAITING for this one for almost 60 years. Gaston LaGaffe in English. And now it’s here. My love affair with Franquin began in about 1962 in France when I was still bounding over the heaving main (or vice versa) whilst in the U.S. Navy.

On liberty one day when we were anchored at Marseilles, I was strolling along the waterfront when I noticed a bookstore. It was on the corner, facing, on one side, the waterfront, the other, a street with a tree-lined meridian. A quiet, peaceful looking venue. I didn’t go into bookstores much in those days: mostly, the books in them were in languages I didn’t read well, so I concentrated on restaurants and bars. (Bars more often than restaurants.) But for some reason I can’t recall, I went into this one.

Browsing along the shelves, I came upon a table piled with books that had cartoon characters on the covers. “Album” they said on their spines. I picked one up and thumbed it. Comic characters abounded within. Both cartoony and realistic strips, a couple pages of each title. There were other features—illustrated text articles on various subjects (how to fly a kite, submarine adventures), some with photographs. Each album, I decided, was made by binding together numerous back issues of a magazine. I liked the cartoony strips I saw, so I bought two of the albums. Since then, I’ve bought 3-4 more at various times in various places.

I was buying the pictures. I don’t speak or read French well enough to follow the stories. Despite this linguistic shortcoming, I remember spending an entire afternoon at a sidewalk café in Paris, ordering in French the whole time. “Un vin rouge,” I began. And then, later, “Encore” and then again “Encore,” “Encore,” “Encore.” The entire afternoon. All in French.

But I digress.

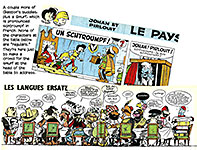

Back to the albums.

Among the strips that caught my eye in the albums I bought were Lucky Luke by Morris (a pen-name that is an alternate spelling of Maurice De Bevere’s first name) and Rene Goscinny, a somewhat more realistically rendered Gil Jordan by Maurice Tillieux, Johan and Peewit by Peyo (wherein the Smurfs first appeared; Peyo is the pen-name of Pierre Culliford), and Boule and Bill (about a boy and his dog) by Jean Roba. And Franquin’s Gaston LaGaffe, Anglesized to “Gomer the Goof” for the book at hand, but he’ll always be Gaston LaGaffe to me. There were also some realistic adventure strips, but I wasn’t interested in them.

|

|

I eventually realized that Spirou was the name of the magazine the issues of which were bound into these albums. (This was in 1962, kimo sabe, and American consciousness of European cartooning was still a few years in the future.) Published by Editions Dupuis, Spirou magazine had been founded in April 1938 in order to print the adventures of a youthful character named Spirou, who appeared, at first, as an elevator operator in the Mosquito Hotel (an allusion to the publisher’s main magazine, Le Moustique). Spirou wore a red bellhop uniform, which he continued to wear long after he ceased being a bellhop.

Drawn

originally by Francois Robert Velter (pen-name Rob-Vel), who had been a

bellhop himself at the tender age of 16, the strip by 1943 was being produced

by Joseph Gillain (Jije), who introduced a new character, Fantasio, who

became Spirou’s best friend and co-adventurer.  Jije had many other artistic and editorial

tasks at the magazine, and he delegated much of his work. In 1946, he handed

the Spirou comic strip to Franquin.

Jije had many other artistic and editorial

tasks at the magazine, and he delegated much of his work. In 1946, he handed

the Spirou comic strip to Franquin.

Franquin was 22 at the time. He’d worked in animation with Jacques Eggermont, Morris, Eddy Paape, and Peyo. When the studio closed, Morris introduced him to Jije, who opened the door to both Franquin and Morris. With Jeje as inspiration and tutor, Franquin, Morris and another pen-named cartoonist Will formed the famed “gang of four,” with Franquin “undoubtedly the grandmaster of the so-called ‘School of Marcinelle,’” a style of drawing and storytelling epitomized in the Spirou magazine in the 1950s and 1960s. Marcinelle was an area on the outskirts of the industrial city of Charleroi, south of Brussels, where the magazine’s publisher was situated at the time.

The young cartoonists worked in the same room together, and they often spent their off-hours together—particularly at the end of the week. Saturday was partying day. No one brought fresh artwork in on Mondays because everyone was still hungover.

According to St. Wikipedia, Franquin was “a true legend in the world of comics,” earning “countless fans, both for his series in general as well as his dynamic, energetic and vivid drawing style. ... [On the Spirou comic strip] he enriched the franchise by creating longer, more complex and ambitious narratives. ... He also introduced several characters still used by his successors, including ... one of the world’s strangest animals, the Marsupilami, [a leopard-spotted monkey-like creature with a tremendously long, prehensile tail] who’d inspire a successful spin-off series of its own.

|

|

“Franquin

is unanimously regarded as the best artist Spirou ever had. Above all,

he was a comedic genius, crafting some of the funniest gag comics ever. ...

[including] his signature series, Gaston LaGaffe [the blunder] about the

most incompetent office clerk who ever existed.  ... Franquin’s graphic style has been

imitated by countless artists, making him one of the most influential Belgian

comic artists of all time, next to Herge [Tintin] and Jije.”

... Franquin’s graphic style has been

imitated by countless artists, making him one of the most influential Belgian

comic artists of all time, next to Herge [Tintin] and Jije.”

Franquin’s influence can be seen in the work of nearly every cartoonist hired by Spirou magazine up until the end of the 1990s. Herge’s style, the famed “clear line” of static restraint was at the opposite end of the aesthetic spectrum from Franquin’s vigorous sense of movement, and Herge admired Franquin’s work: “Franquin is a great artist,” he said. “Compared to him, I’m but a mediocre cartoonist.”

After the Marsupilami, Gaston LaGaffe is Franquin’s most memorable creation. Conceived in 1957, the feature’s initial purpose was simply to fill up random empty spaces in Spirou magazine. The gimmick was that the comic strip pretended to be about the operation of the magazine, offering a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the Spirou office: Gaston was the chronically incompetent office boy. His arrival was anticipated for several months with blue footprints that appeared in the margins of the magazine. When he finally showed up on February 28 for a memorable job interview, he told a bemused Spirou that he didn’t remember with whom or for what he had been called.

|

|

|

Gaston was incompetent but he was also endlessly inventive. He was forever inventing machines that were supposed to perform certain functions—but never did. Fantasio also worked in the Spirou magazine offices, and he, tasked with the impossibility of getting Gaston to actually work, was the unwilling foil for Gaston’s bumbling.

At first, Gaston’s clumsy efforts were confined to single panels. That was soon expanded to strips, and in 1959, the strip was enlarged to a half-page, which lasted until the mid-1960s when it grew to a full page. By 1969, Franquin had tired of the Spirou adventures and passed the feature on to a then unknown young cartoonist, Jean-Claude Fournier, who for the next ten years modernized the feature, addressing current societal issues. Franquin, meanwhile, concentrated on Gaston LaGaffe.

Gaston is the “action hero of laziness,” said Cynthia Rose in introducing a collection of Franquin’s darker strips (which we’ll look at below). St. Wikipedia’s “Gaston” entry supplies an accurate overview—:

“The strip usually focuses on Gaston’s efforts to avoid doing any work, indulging instead in hobbies at the office or taking naps while all those around him panic over deadlines, lost mail and contracts. Initially, Gaston was an irritating simpleton, but he developed a genial personality and sense of humor. Common sense, however, always eludes him, and he has an almost supernatural ability to cause disasters (‘gaffes’) to which he reacts with his catchphrase: ‘M’enfin!’ (‘What the...?’).

“His job involves chiefly dealing with readers’ mail. The ever-growing piles of unanswered letters (‘courrier en retard’) and the attempts of Fantasio to make him deal with it or to retrieve missing documentation are recurring themes.

“Gaston alternates between phases of extreme laziness, when it is near impossible to wake him up, and hyper-activity, when he creates various machines or plays with office furniture. Over the years, the has experimented with cooking, rocket science, music, electronics, decorating, telecommunication, chemistry and many other hobbies, all with uniformly catastrophic results. His Peter Pan-like refusal to grow up and care about his work makes him very endearing, while ironically his antics account for half the stress experienced by his unfortunate co-workers.

“Gaston’s disregard for authority or even public safety are not confined to his office— he occasionally threatens the entire city. He is not above covering road signs with advertising posters or even snowmen, reasoning that it is the only decent use that they have, being oblivious to the chaos and accidents that covering the road signs cause.”

Gaston is invariably dressed in a tight polo-necked green jumper and blue jeans and worn-out espadrilles. But it isn’t his costume that so appeals to me. It’s the way he’s drawn, Franquin’s style. His characters have sausage fingers, doughy ears, spaghetti arms and legs and giant feet—perfect big-foot cartoony creations, caught with a flexing line that waxes thick and wanes thin, making the characters breathe as if they were real. And they’re always in motion. Lively, energetic.

|

|

|

“By the 1960s,” said Rose, “Franquin had created what graphic novel publisher, translator and editor Kim Thompson called ‘the most complete, the most alive, the most absolute cartooniness in comics history.’

“He had his own studio, home to eight colleagues and two full-time assistants. Yet, despite this refuge with its secret phone number, Franquin’s workload simply increased. In 1961, ill with hepatitis, he collapsed into serious depression.”

Franquin dropped Spirou but kept doing Gaston LaGaffe.

Then in 1975, he had a heart attack and disappeared for the next few years. But in 1977, he collaborated with Yvan Delporte, his former editor at Spirou, to produce The Illustrated Trumpet, a little magazine that was stapled into each week’s Spirou. It died after thirty issues, but “it had brought Franquin back to life,” said Rose.

He had drawn the magazine’s cover and contributed a strip. Entitled Idees Noires (“black ideas”), the strip (dubbed Die Laughing for English readers) was innovative in both its sense of humor and its graphic execution. Its black comedy gags targeted hypocritical clergymen, hawkish generals, existential fears, ecological woes, big game hunters, animal abuse, pollution, smokers, the death penalty, religion—all the foibles and ills of modern society that Franquin detested.

Some of the strips are fantasy-oriented and find humor in monsters or people in science fiction settings. “Others are more distrubing,” saith Lambiek.net, “because they take their inspiration from real-life fears, like horrific accidents, executions, suicides, being eaten by animals, epidemics, world war, the atomic bomb and mankind eventually destroying itself.

“The nihilistic tone is complimented by the black inked drawings which all feature silhouetted characters cast in shadowy settings.”

Franquin thought Gaston and Idees Noires were identical: “They’re both the same thing, the same kind of caricature. I always say Idees Noires is just Gaston dragged through the soot, and that’s exactly what it is.”

“The strip’s look came from one of Franquin’s oldest memories,” said Rose in her introduction to Die Laughing, a collection of Idees Noires strips in English (80 9x11-inch pages, b/w; 2018 Fantagraphics hardcover, merely $19.99). He remembered “a series he saw in the Saturday Evening Post—a faux period piece executed with black silhouettes. ... Franquin revived the concept. ‘When I started to think about what I could do for Trumpet, I reverted to that old idea of the silhouettes. Then I realized I could use ‘black’ in both senses. If I used a sinister style to tell sinister stories, that would be unconventional and it could work.’”

But the silhouettes in Idees Noires were not solid black. The black was flecked with white accents—characters’ eyes, collars and shirt cuffs, modeling lines on arms and legs. Franquin's technique of only partially silhouetting his figures permitted him to preserve telling portions of each picture (stress lines in clothing, facial expressions), retaining thereby the essential and characteristic comedic visual vitality of his drawing.

Franquin had used brushes and pens for most of his career, but for Idees Noires, he also used the Rotring pen.

“With this tiny instrument,” said Rose, “he filled vast swathes of black.” It was a labor-intensive method, and he deliberately left patches of white in his silhouettes. If he had used a brush to apply the black, all that minuscule white powder and sleet would have been lost in black.

“It takes hours and hours,” he said, “and the whole time, you’re yelling at yourself. But I love the grain I can get with that Rotring. It gives me the kind of moldy black you see in a film like ‘Nosferatu’ or in old engravings.”

|

|

|

Franquin insisted that he was not a “humorist.” Yet, for him, said Rose, “humor was essential to one’s life. He described laughter as the vice of his youth, saying, ‘I bought laughter just like people today buy drugs.’”

But the comedy wasn’t simply satirical: it was also therapeutic.

“Why do we draw horrible things?” he once said. “In my case, I draw them because I enjoy it. ... But if you look a little bit further, maybe you’ll find it’s my way of transforming certain things, of turning fears into jokes. Fear of aging, getting sick, fear of the actual coffin. ...”

Rose quotes author and critic Jose Louis Boucquet on Franquin: “The art, the understanding of gags, the understanding of rhythm— Idees Noires is everything Franquin learned in his whole career. Graphically, he went to the limits of his system here—and that system ranged from the totally pure to the hyper-detailed. The strips are a colossal work, the most difficult drawing Franquin ever achieved. But then, they are also almost modern art.”

After the collapse of Trumpet, Franquin took Idees Noires to another magazine, where it appeared through 1983.

“From 1966,” Rose said, “Franquin’s strips [Gaston and Idees Noires] grew more and more frenetic; in the 1970s, even his signatures were jokes.

“But, as the artist later confessed, ‘By always piling on none more story, one more detail, always hiding gags within gags, I was heading for an impasse ... for a place where everything overloads and the frequencies jam ... I’m not saying it led straight to my depression, just that there was a constant worry. Something was always haunting me.’”

Franquin’s activities declined in the 1980s, said Lambiek. Gaston made less frequent appearances in Spirou, and the artist’s social activism became clear in the latter years of Gaston LaGaffe. Perhaps Franquin missed the opportunity Idees Noires had offered for expression.

There’ve been over 20 48-page Gaston LaGaffe books, all in French (until 2017), and through the years, I’ve bought six or seven of them—unable to read a word but steeped in the pictures. Now I’ll be able to enjoy words and pictures— cartoons!

Franquin died January 5, 1997, but Gaston lives on, appearing, now—at last—in English translation; a second volume, It’s a Van Goof, is out, and a third, Gone with the Goof, is in the offing. Here we post a plethora of Gaston for you to feast your eyes upon. Enjoy.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|