Fostering the Adventure Strip

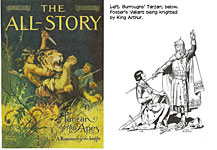

With Tarzan and Prince Valiant

Every year

comes chuck full of anniversaries of one sort or another, and this year’s no

exception. Two of 2012's anniversaries are fraught with implications for the

emergence of the newspaper adventure strip: one hundred years ago, Edgar

Rice Burroughs, after failing at various professions (cowboy, cavalryman—Teddy

Roosevelt rejected his application for the Rough Riders—retail sales, mining),

finally found his metier as the chronicler of a jungle lord with the

publication of “Tarzan of the Apes” in All Story magazine for October

1912; and Prince Valiant, one of the world’s most beautifully drawn

comic strips, started 75 years ago in February.  Both of these watershed events have in

common one iconic figure: Hal Foster, the creator of Prince Valiant,

also drew Tarzan in comic strip form. Foster was the first artist to

draw Tarzan for newspapers; he was also the third artist on the feature.

His work on the adventures of Burroughs’ Ape Man effectively established the

techniques of realistic illustration for the funnies page; and his subsequent

conjuring of the days when knighthood was in flower showed what quality artwork

could do to enhance the narrative of adventure comic strips.

Both of these watershed events have in

common one iconic figure: Hal Foster, the creator of Prince Valiant,

also drew Tarzan in comic strip form. Foster was the first artist to

draw Tarzan for newspapers; he was also the third artist on the feature.

His work on the adventures of Burroughs’ Ape Man effectively established the

techniques of realistic illustration for the funnies page; and his subsequent

conjuring of the days when knighthood was in flower showed what quality artwork

could do to enhance the narrative of adventure comic strips.

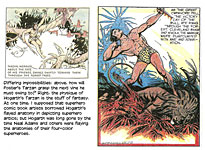

Foster’s reputation is secure enough, after all these years, that it can stand comparison with that of another of Tarzan’s stewards, Burne Hogarth, who was the fourth artist on the newspaper feature. And Foster has often been confronted by Hogarth because they both made their reputations with Tarzan. There, however, the similarity almost ceases—to the credit of both artists.

Hogarth took over the Tarzan Sunday page from Foster in May 1937, left it for about eighteen months in late 1945, and returned for a final three-year tour, abandoning the Ape Man for good in 1950. And because Foster was Hogarth’s immediate predecessor, comparisons between the work of the two were inevitable then as they are now. The most helpful comparison is the one made by Thomas A. Pendleton in an article published by the Journal of Popular Culture in the spring of 1979, “Tarzan of the Papers.”

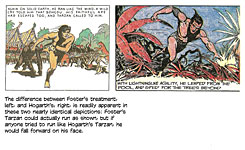

The thing Pendleton made me realize about Foster and Hogarth is that while Foster’s Tarzan was supremely realistic, Hogarth’s was triumphantly supra-realistic. If Foster’s Tarzan is heroic, Hogarth’s is unquestionably superheroic. And this evaluation is to the detriment of neither artist.

The realism of Foster’s Tarzan, Pendleton demonstrates, is of a particular breed. Foster may portray Tarzan doing something impossible, something simply beyond human capability, but he draws Tarzan in a way that persuades us that if it were possible to do the stunt being depicted, this is the way it would be done. “Thus, when Foster presents Tarzan performing one of his remarkable feats, there is always the sense that the feat is being performed with the limited means of the human body.”

While it is Foster’s meticulously realistic depiction of human anatomy in action that achieves the rhetorical purpose in his Tarzan, in Hogarth’s Tarzan we find the visual rhetoric pitched at an extremity. Hogarth’s anatomy and postures seem realistic, but they often are not. Hogarth goes beyond realism. No human being could take the positions that Hogarth’s Tarzan takes. But since Hogarth’s much touted (mostly by Hogarth himself) “dynamic anatomy” is rooted in actuality, his exaggeration of its capabilities seems possible. We are persuaded to accept this possibility by Hogarth’s drawings, by the tension he imparted to his Tarzan’s musculature—the body flayed of a layer of skin to show muscles bunched and ready, coiled to spring into violent activity.

Foster shows us how, in some considerable detail, an action might be accomplished; Hogarth ignores the actual physical performance of the act. He shows us Tarzan in motion, in the midst of a flurry of apparently strenuous activity. His depiction of Tarzan’s muscles assures us of the strenuousness of an action, and that, in turn, convinces us that Tarzan has actually done it—or is doing it. Hogarth doesn’t show us how something is done so much as he persuades us that it could be done, or has been done, by performing this visual slight of hand. We think we’ve seen it, but we haven’t, actually. Hogarth communicated a sense of power; Foster, a vision of reality.

|

|

|

But

even Foster, passionate realist that he was, sometimes rather obviously dropped

the ball. On his Tarzan page for December 13, 1931, for instance, he

shows us the Lord of the Jungle swinging, as was his wont, through the trees,

from vine to vine to vine. After eighty years of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ telling

us about this stunt, we are so jaded by familiarity with the routine that we,

today, don’t notice the impossibility that Foster has foisted off on us. But surely

some of his readers back then, newer to the ritual, must’ve noticed that Tarzan

was carrying a spear in his right hand as he swung through the trees, thereby

making his vine-to-vine progress virtually impossible. Think about it: how does

he grab the next vine if one of his hands is fully committed to another task?

Foster rarely slipped so blatantly. But in those early months on the feature, he was, as he often said, just “scratching them out.” His scorn for the medium was barely contained. When he began receiving fan mail, however, he realized that readers scarcely shared his low opinion of the product he was manufacturing. They loved it. And once Foster came to appreciate their devotion, he, too, became more devoted to his work. And the realism he exercised in the jungles of Africa turned out to be good practice for depicting another world, one that never actually existed at all.

HAROLD RUDOLF FOSTER was born in 1892 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, the son of Edward Lusher Foster and Janet Grace nee Rudolf (hence the cartoonist’s middle name). The father died when Harold was four, and his mother remarried, a man named Cox, whose passion for hunting and fly-fishing and the outdoor life his stepson acquired and, in later years, often displayed in Prince Valiant. Cox went broke in 1906, and the family moved to Winnipeg, where Harold began working as an office boy, then learned shorthand and typing and became a stenographer. He disliked office work, however, and in 1911, he found employment as an artist, illustrating mail-order catalogues. He worked for a succession of printing concerns and agencies in Winnipeg, establishing himself as a competent illustrator. During periods of low demand for his work as an artist, he served as a professional guide for hunting expeditions. On August 28, 1915, he married Helen Lucille Wells, an American from Kansas; they spent their honeymoon in a canoe, exploring unmapped lakes no white woman had ever seen before. There were, eventually, two sons.

In 1921, feeling he had reached a professional plateau in Winnipeg, Foster went with a friend to Chicago—a thousand miles by bicycle. He took a position with Palenske-Yount, an advertising studio, for which he did general illustration (ads and magazine covers); at the same time, he did work for Jahn & Ollier Engraving Company. In 1922, he began taking evening classes at the Chicago Art Institute, continuing, 1925-27, at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. And then he was discovered by a client’s salesman, Joseph Neebe.

Neebe had hopes for a publishing enterprise he called Famous Books and Plays, and he made a deal with Burroughs to adapt Tarzan of the Apes. When Burroughs’ cover artist, Allen St. John, was not interested, Neebe approached Foster, whom he knew through a mutual engagement in advertising. Foster took the assignment and, using a script adaptation by R.W. Palmer, did the first volume of Neebe’s series. When the book didn’t fare well, Foster was asked to convert Tarzan into newspaper comic strip format, launching Neebe’s newest scheme, producing illustrated serialized literature for syndication to newspapers.

In form, the product looked much like a comic strip albeit without speech balloons: a “strip” of individual illustrations beneath which ran narrative typeset text abridging the book. In this effort, Neebe joined other entrepreneurs of the time who were doing much the same—among them, a certain Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, a one-time cavalry officer who would, a scant half-dozen years later, produce another kind of illustrated literature when he started publishing comic books.

Foster

produced 300 panels to illustrate a 10-week serialization of Burroughs’ novel.

Then he went back to advertising. The serial began in England in November 1928;

in the U.S., it started on January 7, 1929, and concluded March 16. Rex Maxon

continued the serialized Tarzan, illustrating The Return of Tarzan,

and when the feature proved popular enough to prompt interest in a Sunday

version in color, Maxon inaugurated that in March 1931. Meanwhile, Foster’s

daily series had been re-issued in book form by Grosset & Dunlap in August

1929.

Burroughs, who was something of a cartooning artist himself, had appreciated and prized Foster’s work. And Burroughs was not happy with Maxon, who he believed made Tarzan look ridiculous. Neebe sought out Foster again, and by then, Foster needed a way to make a living. By 1931, the Depression had whittled away at the advertising dollar, and Foster was suffering. On September 27, 1931, Foster replaced Maxon on the Sunday Tarzan, and for the next six years, Foster “ate ape,” as he put it, earning, at first, $75 a week.

Unhappy with the quality of the scripts he was getting, Foster began revising them; and he took pains with the artwork, detailing the foliage of Tarzan’s jungle setting as well as the Ape Man’s anatomy. Foster also began using cinematic techniques—close-ups, panoramic scenes, shifting the camera angles—to intensify the drama of the stories. Tarzan soon emerged as the best-drawn feature in the comics. But Foster began to feel the need for greater creative freedom.

Tarzan was tightly controlled by Burroughs, and by 1934, Foster was feeling frustrated.

Burroughs, clearly valuing Foster’s effort, urged the syndicate, United Feature, to raise Foster’s salary again in order to keep him. But even an increase to $125 wasn’t enough. The bug had bitten. Foster yearned for a character of his own whose fate he could dictate himself without restriction. Foster started toying with the idea of a story about knights in armor, and by the fall of 1936, he was actively working on the project. At about this time, too, King Features, impressed with Foster’s increasingly stunning work on Tarzan, was courting him.

Foster told Joseph V. Connolly, president of King, that he had an idea but hadn’t polished it. “Connolly said, You don’t really need a story at all; come with us and we’ll provide a story. Well, that’s just what I didn’t want,” Foster said. “I wanted my own story.”

He picked the Medieval period because, he said, it “gave me scope.” It also gave him freedom, the poetic license that is possible when there are very few written records to contest the tales he would tell.

At first, Foster thought he might tell a story about a young man going on one of the great Crusades of the middle ages. He soon realized that this conception imposed a limitation: after the Crusade, what would his hero do? Foster finally decided on a legendary past rather than a historical one, choosing Camelot and the days of King Arthur’s Round Table.

To evade the distractions of life in the big city, he and his wife moved in the summer of 1936 from Chicago to Topeka, Kansas, where she would tend her ailing grandmother while Foster devised his new strip. He first produced enough Tarzan pages to get four months ahead of his deadline schedule, then he devoted himself full-time to researching and developing the feature that would be called Prince Valiant.

In his quest for realism, Foster researched medieval history, art, and literature extensively, producing a convincing aura of authenticity in Prince Valiant. Ever since quitting school at the age of fourteen, Foster had been an avid reader and an enthusiastic devotee in the quest for knowledge, and he now indulged this passion in his work.

“The public does not know the amount of fact and data I get into Prince Val,” he once wrote. “I do it for my own pleasure, figuring that if I get a lot of pleasure doing something my own way all my working hours, it would be clear profit. If the public likes it and will pay for the pleasure of looking at it, why, that is an extra dividend.”

But Foster’s Camelot was not King Arthur’s. The Arthur of history and legend lived in about 450-500 A.D. Foster moved the time of his story forward about 500 years because the costumes and pageantry of the later period were more attuned to the popular idea of Arthurian knighthood, however mistaken that idea was historically. Within his chosen period, though, Foster was so thoroughly accurate that many of his readers regarded the strip as an educational adventure as well as a heroic one. For a brief time, Foster produced two other features: one, Medieval Castle, running at the bottom of the Prince Valiant page, was overtly educational; the other, a separate strip (1942) called The Song of Bernadette, was also more about life in the Middle Ages than it was about the titular heroine.

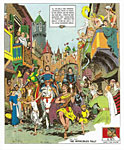

Writing as well as drawing Prince Valiant, Foster achieved an excellence in both story and illustration that would never be surpassed on the comics pages. Starting February 13, 1937, Prince Valiant traced the life of its protagonist, beginning with his youth in the fens, where he grows to manhood, learning to hunt and fish and to be resourceful as a warrior. He journeys to Camelot and becomes squire to Sir Gawain, and the two embark upon the first of many quests. By his valor in battle, Val wins the legendary Singing Sword and, eventually, his knighthood. He courts the beautiful Queen of the Misty Isles, Aleta; they are married and have several children.

Foster’s stories demonstrated his hero’s considerable ingenuity at all manner of enterprises not just warfare; and Foster varied the focus, shifting from the battlefield to the hearth for interludes of married bliss (which usually resulted in Aleta’s winning so many of her campaigns that Val went on another quest just to escape domesticity). The stories were suspenseful and inventive, by turns humorous and sentimental, violent and peaceful, action-packed and restful, romantic and pragmatic.

An admirer of the classic illustrative styles of Howard Pyle and E.A. Abbey, Foster was a brilliant draftsman, and his art was realistic, confident, and masterful. Before long, he began to vary the page layouts to give his story visual impact, producing magnificent vistas in spacious half-page panels—becalmed seascapes mirroring Viking vessels in the glassy surface, sprawling landscapes of fertile valleys dotted with medieval huts and castles, towering snow-capped mountain ranges, and teeming mob scenes with scores of people milling through the marketplace or manning siege machines outside walled cities. Like Tarzan, Prince Valiant was an illustrated narrative: Foster’s luxuriantly detailed pictures appeared above blocks of his terse, languid prose, and speech balloons never intruded into the illustrations.

WHILE FOSTER’S TALENT and dedication as an illustrator and storyteller undeniably elevated the quality of the Sunday funnies, his fathering of the adventure strip can be quibbled over. The adventure strip had emerged in the 1920s, most notably in Roy Crane’s Wash Tubbs, which, by the spring of 1929, had added the exotic and two-fisted Captain Easy to the rollicking fare. (For the whole fascinating history of this feature, consult Harv’s Hindsight for July 2002.) But Crane’s strip was not realistically rendered: while backgrounds were often realistic-looking, his characters were bigfoot cartoon creations. In the history of the more illustrative adventure strips, Foster usually shares paternity with two others, Alex Raymond and Milton Caniff. Both came after Foster’s impressive stint on Tarzan: Raymond in January 1934 with Flash Gordon, Secret Agent X-9, and Jungle Jim; Caniff in October that year with Terry and the Pirates.

Although Caniff’s early work was more basic cartooning than illustration, he eventually, under the influence of his studio mate, Noel Sickles, achieved a impressionistic illusion of reality through the judicious spotting of solid black for shadows, the so-called chiaroscuro technique. In his landmark biography of Foster, Harold Foster: Father of the Adventure Strip, Brian M. Kane credits Foster with introducing this technique in his 1929 daily Tarzan. And while Foster was clearly deploying shadow in the same manner as Sickles and Caniff, he was not the inspiration for their efforts. Sickles was recollecting his youthful study of French Impressionists and their use of light, and Caniff was imitating Sickles. In any event, Raymond was more in the Foster mold than Caniff: both Foster and Raymond worked in the “every wrinkle must show” tradition (as Caniff put it); and Sickles and Caniff tried to suggest rather than to show. After the mid-1930s, most cartoonists producing realistic strips drew in either the Foster-Raymond manner or in the Sickles-Caniff manner.

Foster admired Caniff’s work. During his last interview, granted when he was 87, Foster could recall when asked about his favorite fellow cartoonists the name of only one: “Milton Caniff. He wrote well, he knew how to be dramatic, and he had great artistic ability,” Foster told Arn Saba in an interview published in The Comics Journal.

Foster and Caniff corresponded in the early years of Prince Valiant. And in 1940, they met when Foster came to New York. They had dinner one evening at the Palm, a former speakeasy that Caniff frequented. (He told me once that it was almost a “livingroom” for him and his wife during their early sojourn in New York, and when he returned to the city in the 1980s, he took an apartment just a block away.) The walls of the Palm had been decorated over the years by numerous cartoonists, who, after delivering their work to the nearby offices of King Features, retired to the Palm for liquid recreation. Following a certain period of lubrication, they fell to defacing the walls of the place. Andy Gump, Dumb Dora, Jiggs, Mary Mixup, Smitty, Pete the Tramp, and others, plus countless caricatures of cartoonists, cavorted on the plaster.

After

dinner, Caniff and Foster enhanced these merry murals by drawing their

principal characters toasting each other in terms of their syndicates. Caniff

drew Pat Ryan, lifting his glass and saying, “Gentlemen, to King.” And Foster

concluded the punning salute with a drawing of Prince Val, raising a ram’s horn

tankard and saying, “Merry—a nice Tribune” (Chicago Tribune/New York Daily News

Syndicate).

The pictures are still there, by the way, albeit obscured somewhat. In subsequent redecorations of the Palm, a wooden rack for waiters’ orders was hung over the pictures. But the curious art lover can usually prevail upon the bartender to remove the woodwork long enough to display the art.

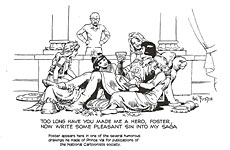

Foster once acknowledged the triumvirate of which he was a part, writing to Caniff: “If you and that other whipper-snapper—what’s his name? Alex Raymond—if the two of you were only to die or somehow disappear, I’d have the field to myself. And then I alone would receive the adulation of the multitudes as the best funny paper artist in the business.”

The ostentation lurking in this remark is a deliberate pose, a sort of masquerade Foster enacted in a parody of self-importance.

“A lot of people thought he was a conceited bastard,” Caniff told me. “He had this curious conceit. Understandably, he thought well of himself: he was so damn good. But I think people thought he was hopelessly and boringly conceited. But I don’t think that was it. I think it was his way—this was his joke. He would say these bald things about himself—so bald that you’d say, Oh shit. Then afterwards, you’d think, Well, maybe he was having me on, pulling my

leg. I think he was kind of shy. Very often, a shy person as famous as he was will be kind of flamboyant. I liked him. Admired his work, but I also liked him personally.”

Foster tipped his hand often in letters to Caniff. “This letter might go on indefinitely for I am on a subject I adore—telling about me,” he wrote once, “and there are so many nice things left unsaid that even I, strong man that I am, find my fingers flattening out at the ends from continuous pecking at this mechanical finger-dodger and must quit.”

On another occasion, he wrote: “On these pages, you will find Hal Foster naked. Rambling, slightly incoherent, addicted overmuch to the use of ‘I,’ verbose and steadfast in only one purpose: never to take anything overly serious, not even H. Foster.”

Foster became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1934, and in 1944, he moved to a six-ace farm in Redding, Connecticut, where he could hunt and fish on his own property. In 1971, he began to retire; he moved to Spring Hill, Florida, and hired John Cullen Murphy to draw Prince Valiant. Foster continued to write it until 1980 (his last page, February 10), when he relinquished the entire task to Murphy; he died two years later, July 25, 1982. In 2004, Murphy retired and was succeeded by Gary Gianni, who initially drew from scripts by Murphy’s son Cullen, who had written the feature since Foster’s retirement; subsequently, Mark Schultz took over the scripting.

Even if Foster didn’t invent the adventure strip (and he didn’t), in his Sunday pages—particularly in Prince Valiant—he gave the newspaper comics section class, and his illustrative style illuminated the possibilities for others, demonstrating on a grand scale what quality realistic illustration can do to enhance the narrative of storytelling comic strips: the more realistic—the better—the art, the more palpable the dangers and daring in the adventures being depicted. And here are pictorial testimonies to that.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|