|

QUICK,

HENRY—THE FLIT!

The Flitting

Life of Dr. Seuss

“Flit.” That

simple monosyllable earmarks one of the most celebrated advertising campaigns

of the 1930s. “Flit” was the brand name of an insecticide that had been

concocted in 1923. In those days before air-conditioning (which permits us to

keep all windows closed and bugs outside), every home faced summer with open

windows (for cooling breezes) and a bug-spray dispenser with a supply of spray.

Flit supplied both of the latter.

Flit

became famous in the next decade after Theodore Seuss Geisel had been

contracted to draw cartoons that illustrated with hysterical exaggeration some

insect-threatening situation in which the menaced person calls for rescue by

yelling: “Quick, Henry—the Flit!”

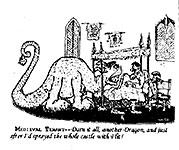

In

the late 1920s, Geisel was drawing cartoons for the humor magazine, Judge, signing

his work “Dr. Seuss” (because, he explained, he was “saving the name Geisel for

the Great American Novel”). In the January 14, 1928 issue of the magazine, one

of his cartoons depicted a medieval knight, sprawled in bed, a snarling dragon

looming over him. Said the knight: “Darn it all—another dragon. And just after

I’d sprayed the whole castle with Flit!”

The

wife of the advertising executive handing the Flit account saw the cartoon in Judge at her hairdresser’s and urged her husband to contact the cartoonist and sign

him up. (Geisel said it was bald-faced luck: “It wasn’t even her regular

hairdresser. He was booked that day, so she went someplace else. Her regular

hairdresser was much ritzier and would never have had a copy of Judge in

his salon.”)

Geisel’s

contract lasted for the next seventeen years and presumably supplied him with

enough income (at one time, $12,000 a month) that he could spend a lot of his

time away from cartooning, devising, instead, the children’s books that made him

famous as a doctor without a degree. Not that he gave up cartooning. He

continued cartooning for Judge and expanded his client list to include

the old Life humor magazine and College Humor and Liberty magazine

until the early 1930s, when his contract with Flit prohibited such expeditions.

His

Flit drawings permitted him to exercise his most inventive cartooning

exaggerations. On one occasion, he showed a convict attacked by mosquitoes in

the middle of a prison break; in another, a seance is interrupted by a genie

emerging amid a swarm of bugs. In every case, the victims of the buggy attack

yell the four-word cry for help: “Quick, Henry—the Flit!”

Judith

and Neil Morgan in their Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel indicate the

pervasiveness of the Flit advertising campaign:

“The

phrase ‘Quick, Henry—the Flit!’ entered the American vernacular” and became a

punchline everywhere in the culture. “A song was written about it, and Geisel’s

cartoons spread from the pages of Judge and Life to newspapers,

subway cards and billboards. Comedians Fred Allen and Jack Benny used the tag line over the radio networks for dependable boffs, and across

America, the folksy mention of a bug spray evoked laughter. Flit sales

increased wildly. No advertising campaign remotely like it had succeeded before

on such a grand scale. The series found its way into histories of advertising

and was compared with the Burma Shave series of ubiquitous roadside rhymes. The

nearest thing to criticism was an agency warning that sometimes the bugs Geisel

drew were too lovable to kill.”

The

Flit campaign made Geisel an icon in the realm of advertising. “The campaign

was so successful,” said Phil Nel in his Dr.Seuss: American Icon, “that

Flit remains one of the primary ways in which Dr. Seuss is remembered. ... It

was the first major advertising campaign to be based on humorous cartoons.”

Despite

the nation-wide acceptance of his Flit cartoons, Geisel had no high opinion of

his work, according to Nel, confessing on more than one occasion that he could

not draw. “I still can’t draw,” he would say. “I always get the knees in wrong,

and the tails. I’m always putting in too many tails. I just can’t draw, I

guess. People like the Grinch. I started out to draw a kangaroo and it turns

out to be a Grinch. I don’t know, all my creatures seem to turn out catlike.”

Nel,

however, is quite aware of Geisel’s talent, particularly as manifest in the

books he wrote for children. “To appreciate Seuss’s artistic talents,” Nel

writes, “one must first examine the relationship between his art and the story.

It is the balance of words and pictures that makes the books work. As John Cech

observed after seeing the exhibition ‘Dr. Seuss from Then to Now,’ ‘when

pictures from Seuss’s books are displayed on museum walls [without the text],

one sees how utterly tied most of them are to the printed page and thus to

Seuss’s texts. For Seuss is a true artist of the picture book, a brilliant

master of that bimedial form, more than he is an artist whose visual works can

(or are designed to) stand alone.’ Though Seuss has created art that stands

alone ... the picture-book art is always interdependent with his text.”

Geisel,

in other words, is a cartoonist. Not a writer. Not an artist. But a

cartoonist, a storyteller who conjures up his visions in a perfect blend of

words and pictures. In each of his masterworks, Dr. Seuss achieved by creative

instinct a mutual dependency in which neither the words nor the pictures makes

as much sense alone without the other as they do together.

And

that talent is easily evident in his Flit ads—as you can readily tell from our

concluding array (which we begin with Seuss’s self-caricature wearing the

famous cat’s hat).

Return to Harv's Hindsights |