Revisiting

the Maturing of the Comic Book:

A Quick

Eccentrially Skewed Tour of The Crucial 1970-1990s

FROM FIGURE

DRAWING TO STORYTELLING

From

Corporate Creation to Individual Expression

BY THE END OF

THE EIGHTIES, the situation in mainstream comic book production had changed greatly.

In addition to being paid set fees per page, creators could earn royalties

based upon the sales of the their comic books and sometimes a percentage of the

ancillary revenue generated by merchandising the characters. They also

retained ownership of their original art (a development originating in the

underground), and they sometimes owned the characters they concocted. As the

1990s dawned, the economy of the comic book industry had been so violently

altered that a cartoonist producing comic books could become very wealthy.

Indeed, some, riding the crest of momentary fan adulation, became millionaires

overnight.

While

underground comix were revolutionizing the comic book economy in this country

in the late 1960s and early 1970s, they were also influencing content abroad.

European comics blossomed under an arrangement quite different from the

American system. Newspaper feature syndication doesn't exist; newspaper comic

strips are produced for individual publications only. Most cartooning on a national

scale takes place in magazine format. Cartoonists draw for weeklies that print

multiple-issue stories in 4-6 page installments. After the initial printing in

serial form, the pages are collected and re-issued in hardbound

"albums." Comic books in Europe are, therefore, real books, not

magazines. And they have a cultural status that American comic books would not

achieve for years. Moreover, the production values in European comics were

much higher: the colors are applied in a painterly fashion, not mechanically

by overlays (as in the U.S.), and the full-color art is printed on high quality

coated stock. Comic book art in Europe is beautiful to look at because the

visual character of the work is carefully created and then enhanced by the

manner of publication.

European

cartoonists were as astonished and liberated by American underground

cartoonists as those cartoonists had been by Harvey Kurtzman and Mad. Mad, in fact, was as much an inspiration overseas as it had been in the

U.S. (Kurtzman's connection to the European cartooning community was even more

direct. Rene Goscinny, who had created the mildly satirical and

internationally popular Asterix series with Albert Uderzo and had

founded Pilote magazine in 1959, was a friend and admirer of Kurtzman's.

Goscinny had spent several years in America, and during most of them, he worked

out of the studio Kurtzman and Will Elder operated in the late 1940s.)

The weekly magazines in Europe were produced chiefly for young readers. The

American underground cartoonists showed that comics produced for a mature

readership could be financially viable. Soon, Europe's albums of comics began

to address adult themes in very sophisticated terms.

Meanwhile,

on the American side of the Atlantic, underground cartoonists were becoming

introspective, their treatments calmer, their subjects more varied. Perhaps

their purely rebellious energy had been spent in the orgy of sex and drugs

comix that reached peak production in the early 1970s. Perhaps they had grown

wary. A tide of censorship had washed over the land in the mid-seventies.

In

June 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a new ruling on obscenity that gave

local governments the power to determine what was pornographic. Comix had been

sold almost exclusively through the "head shops" that had grown up in

large metropolitan areas to sell drug paraphernalia— bongs, papers, roach

holders, etc.— as well as exotic clothing and the other psychedelic trimmings

of the counterculture. These outlets, already operating on the legal fringes

of their communities, stopped carrying comix for fear authorities would use

local obscenity laws to shut them down. The market for comix eventually

revived, but it was never as flush with product as it had been before the

Supreme Court ruling. And in the interim, cartoonists had discovered less

blatantly offensive subjects.

Robert

Crumb, one of the seminal figures in the underground movement, had always

been a character in his own comix. He had developed other characters— Fritz

the Cat, Mr. Natural— but he eventually wearied of them all. Only his Crumb

creation, his alter ego, commanded his unflagging interest. (For a more

detailed examination of Crumb and other cartoonists who created similarly

autobiographical works, odysseys in private exploration, sometimes searing in

their self-revelatory themes, consult a book of mine, The Art of the Comic

Book.) With Crumb as exemplar, comix increasingly became personal artworks,

individually expressive reflections of the interests of their creators rather

than products of a publisher's tradition or market research. Paralleling this

development were the ground-level comic books of the alternative press in which

cartoonists examined slices of ordinary life, searching for the daily drama of living.

In

a way, it was the underground that opened the way to a new marketplace. The

counterculture's head shops had enabled comix to survive— even thrive— and in

doing so, they proved that general newsstand distribution was not essential to

economic vitality. The direct sale comic book shops that sprouted up all over

the country in the 1980s represented a merchandising network much like that

which had been established by the head shops. Comix alone could not have

supported the national circuit of direct sale shops specializing only in comic

books. But once that network was in place, the market for the personal works

of underground and unconventional cartoonists was ready. And the publication

of such works was no longer confined to the alternate press.

The

success of the direct sales network had freed major mainstream publishers from

their traditional economic bondage to an antiquated distribution system.

Marvel and DC contemplated the direct sales shops and saw dollar signs. And

before long, even these faceless corporate funnybook factories began to produce

comic books that reflected the personal visions of their creators.

The

earliest forays into this new territory took the form of "relevant"

comics that touched on social issues like poverty and drug use, and the first

of these in the early 1970s preceded the direct sales market. The most

astonishing effort of the decade, however, was Steve Gerber's Howard

the Duck, a send-up of the Marvel Universe that graduated into social

satire and then turned inward to evolve an intensely personal statement.

Artistic

expressiveness of a highly individualistic sort had never been particularly

welcomed by traditional comic book publishers. The corporate mind, ever

focussed on the bottom line of the balance sheet, favored bland "house

styles" of rendering and committee-generated stories, neither of which,

given the compromise inherent in the process, would be likely to offend

potential buyers. But the medium had always attracted creative people, and

they had lived and worked within its commercial constraints, sometimes happily,

sometimes restively. And as direct sale shops began to prove their viability,

the economics of the industry seemed beckoning to more adventurous, more

personal, endeavors. Still, the route to individual expression in mainstream

publishing was a long and tortuous one; it was, in fact, not one route but

several, each a tributary that followed a different course to a seemingly

different objective, but some culminated in the 1980s in an artistic

renaissance that found its impetus in all of the creative impulses of the

diverse endeavors. And the renaissance flowered in the fertile economic garden

of the direct sale shops.

For

the sake of discussion, let me simplify the progression by positing that there

are two traditions in comic book creation— the figure drawing tradition and the

storytelling tradition. Neither is wholly exclusive of the concerns of the

other, but each pursued its emphasis with slightly different results. Jack

Kirby belongs at the beginning of the figure drawing tradition. The

artistic preoccupation is rendering the human figure, and the comics were all

anatomy and the figure in action. Kirby was not so absorbed in this endeavor

that he neglected storytelling; that's one of the things that made him unique.

Lou

Fine was another of the early comic book artists who focused on the figure.

For Fine, his heroes’ costumes were virtually non-existent: to enable his

rendering of anatomy in loving detail, he almost ignored costumes, with the

result that they seemed, on Fine’s figures, to be painted on the bodies. Fine

did not originate skin-tight costumes for superheroes, but in his hands,

skin-tight reached its apotheosis.

Artists

like Kirby and Fine helped to establish the importance of figure drawing in the

superhero genre of comic book, and many of those who followed in their

footsteps were polished artists without being storytellers at all. Others were

both storytellers and graphic artists. Such artists as Gil Kane and Curt

Swan and Murphy Anderson belong in the figure drawing tradition.

The

figure drawing school may be said to have reached its apogee in the early 1970s

in Neal Adams, whose skill and subtlety in rendering the human form in

action was extraordinary. Kirby and Adams set the mold for house styles:

those who began drawing for comic books after them were often directed to

imitate their styles. Bill Sienkiewicz and John Byrne were, for

a time, Adams clones. And to a lesser extent so were George Perez and Jose

Luis Garcia Lopez. Sienkiewicz eventually changed his style radically;

Byrne didn't, but when he began writing his own stories, he stepped from the

figure drawing tradition into the storytelling tradition and stood there, a

formidable foot in each camp. The figure drawing tradition would culminate in

the poster pages of Image Comics, where, for a time, picture reigned supreme

almost to the complete exclusion of story. But Image Comics would not have

been possible without the effusions of the more individualistic storytelling

tradition.

I

put Will Eisner and Kurtzman at the headwaters of the storytelling

tradition. Their preoccupation was less with drawing and more with story, with

content. Their drawings were composed to serve the narrative, to time its

events for dramatic effect; similarly, panel composition aimed at intensifying

the impact of aspects of the story.

And their work was also highly

individualistic; it was therefore unsuited to anything so homogenized as a

"house style." Those who were inspired by the work of Eisner and

Kurtzman or who worked in the storytelling tradition produced comparatively

idiosyncratic works, which, in turn, stimulated others of similar persuasion.

We can see the process at work in tracing Kurtzman's effect on underground

cartoonists and on European cartoonists. But the storytelling tradition found

champions in the American mainstream, too.

At

Marvel in the late sixties, Jim Steranko was renovating the rhetoric of

comic books with a flashy array of special visual effects. Many of these were

gimmicky devices— color holds and hallucinatory optical effects— but Steranko's

splash pages often showed Eisner's influence, and in some of his sequences we

find the kind of pacing for dramatic effect that distinguished the work of both

Eisner and Kurtzman.

Special visual effects intrigued several of Steranko's

cohorts.

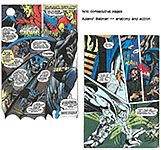

Neal

Adams did elaborately symbolic page layouts sometimes— once shaping his

panels in the profiles of his characters, once drawing a wavy grid of panel

borders the seeming undulation of which reflected his hero's momentary

disorientation, another time superimposing the grid upon a full-page rendering

of a face so that each panel focussed our attention on a separate expressive

feature of the visage.

Walt

Simonson in the early 1970s used typography in decoratively dramatic ways

in his Manhunter series for DC; and he regularly discarded the conventional

grid layout of pages in order to arrange panels of different size and shape in

ways that would give dramatic emphasis to the events of his stories. Comic book

pages began to have the quality of graphic designs. Of this development, Howard

Chaykin is a particularly avid proponent.

Chaykin

left comic books for a few years in the late seventies to do "visual

novels" for Byron Preiss. For Empire (1978) and The Stars My

Destination (1979), he produced fully painted illustrations— several to a

page in the fashion of comic book panels— that shared the narrative with the

original author's accompanying text. When he returned to comic books in 1983

with his American Flagg! series for First Comics, Chaykin brought with

him a heightened sense of design, and the pages of Flagg! are laid out

like posters, panels alternating with full-figure renderings or lobby-card

close-ups against a plain white ground.  Typography also plays a dramatic role in the page

designs and in the narrative itself, different type faces evoking a variety of

emotional responses. Typography also plays a dramatic role in the page

designs and in the narrative itself, different type faces evoking a variety of

emotional responses.

The

pronounced design quality of Chaykin’s pages gives sheer imagery a narrative

role; there is little continuity of action in the usual manner of comics. The

reader absorbs the story as a series of visual impressions, and Chaykin

heightened the sense that the narrative progressed by imagistic fits and starts

with a storyline that is extremely elliptical, jumping from one incident to the

next and landing his readers, often, in the midst of the action with little or

no preamble. And he employed the cinematic maneuver of the voice-over: in the

last panel of a sequence, the speech balloons of the next sequence frequently

appear, making the bridge between scenes. When more elaborate connective

tissue was needed, he used television as his narrator: TV commentators supply

explanatory background with their reports and analyses of the

"news."

In

subject, Chaykin's story is gritty and vulgar: it plunges through street gang

violence in a futuristic multiplex with Reuben Flagg's sexual dalliances as a

leitmotif. In treatment, American Flagg! is sophisticated and

intellectually intriguing, often in the manner of puzzle-solving. Emotionally,

however, the tales are seldom engaging; none of Chaykin's characters are

sympathetic enough to make us like them. Still, Chaykin's comics are for

adults: they are mature in theme and in manner of presentation.

Elsewhere,

at Marvel a young artist named Frank Miller was mastering the rhetoric

of the medium and deploying it more and more expertly in each successive issue

of Daredevil. Miller devoured Eisner and Kurtzman and everyone else who

came under his questing eye. He put the lessons he learned to work as he

learned them. He seemed to move immediately, almost instantaneously, from mimicry

to mastery: he understood a technique he observed so thoroughly that he seemed

wholly in command of it the first time he employed it. And every device he

used, he improved upon.

And

Miller had an impact. Other comic book artists watched him. And, even more

importantly for the evolution of the medium in the commercial arena, his work

stimulated sales. Daredevil was one of Marvel's slow movers when Miller

was assigned to it in the spring of 1979; within months, Miller had made it a

best seller. And in the process, he had conducted a virtuoso demonstration of

an astonishing variety of storytelling maneuvers.

His

aptitude for storytelling by yoking the visual to the verbal was so fecund that

he soon left his writer behind; after only ten issues, he was writing his own

stories. He wrote Daredevil into the same shadowy, grimy underworld of petty

criminals that Eisner's Spirit had dwelt in; and he manipulated mood and time

with an adroit skill that evokes both Eisner and Kurtzman.

Miller's

success with Daredevil was emblematic of the last step in the evolution

of individualized expression in mainstream comics: with the emergence of the

artist-writer (the cartoonist), the committee-generated comic book went into

decline. John Byrne had also made the transition from artist to

artist-writer, but he drew in the conventional house style and so was neither

disruptive nor inspirational as a creative personality. Miller, on the other

hand, dazzled with technique and seemed to throw off innovations with every

page of his work.

Miller

left Daredevil and Marvel in late 1982 and produced a six-issue series

for DC called Ronin (1983-84). Set thirty years in the future, the story

brought the traditions of the masterless samurai into science fiction. But

more significant than the substance of the story was the manner of its

execution.

Miller

regarded the months he spent on the project as the most liberating of his

professional life. He broke all the rules. His breakdowns and page layouts

are startling departures. On some pages, all the panels are page-wide

horizontals; on others, all page-wide verticals. Sometimes whole pages were

devoted to a single drawing; some drawings take two pages, a double-spread.

Some pages have four panels; others, a score. He used color and imagery

rhetorically. And all these pyrotechnics served the narrative, giving it

emphasis and tone.

Finally,

Miller also broke with the traditional rendering style of superhero comics. He

both pencilled and inked Ronin, using a simple often delicate line. The

pictures are textured with hachuring as well as cross-hatching, but his figures

are frequently drawn in mere outline. In fact, the visual styling changes

subtly from scene to scene to suit the mood of the sequence being rendered. Ronin was a vivid and persuasive demonstration of the medium's new direction in the

mainstream: the story was drawn in a graphic style as personal in execution as

it was individual in conception.

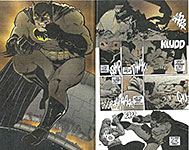

Freed

from the time-honored graphic conventions of the medium, Miller took the next

step with the spectacularly different visuals of his 1986 DC offering, The

Return of the Dark Knight. In this four-issue, square-bound paperback

series, Batman comes out of retirement, a rampaging psychotic.  And the startling

re-interpretation of this sacred superheroic icon was reinforced by Miller's

sometimes unorthodox graphic treatment. He often simplified his rendering of

the heroic figure into abstraction; the pictures, frequently almost

caricatures— cruel in their exaggeration— give the story a raw edge. With the

advent of Dark Knight, individual graphic styling invaded the sacred

precincts of the house style and laid it waste as nothing had before. And the startling

re-interpretation of this sacred superheroic icon was reinforced by Miller's

sometimes unorthodox graphic treatment. He often simplified his rendering of

the heroic figure into abstraction; the pictures, frequently almost

caricatures— cruel in their exaggeration— give the story a raw edge. With the

advent of Dark Knight, individual graphic styling invaded the sacred

precincts of the house style and laid it waste as nothing had before.

The

series attracted national attention, proclaiming the literary and artistic

legitimacy of the comic book form, which, when in square-back format, began to

be termed “graphic novel.” And this success, both commercial and aesthetic,

established the validity of eccentric, highly stylized storytelling

techniques.

Miller's

other innovation, telling a story that dwelled on the dark side of Batman's

soul, ushered in a new era in superhero comic books: slowly at first then more

and more frequently, stories about the traditional superheroes got grimmer, the

streets meaner and grittier, and the personalities of the heroes more flawed.

Some of these colorfully clad avengers, mostly notably Batman, teetered on the

edge of sanity.

By

the early 1990s, some comics readers were beginning to complain about the

"darkening" of heroism: their heroes not only had feet of clay, they

had dirty hands, foul mouths, and the ideals of psychopaths. Distasteful

though this development was, it also signalled the emergence of a new artistic

freedom in the industry.

The

evolution of the medium was now virtually complete: the graphic novel was on

the cusp of establishing literary legitimacy, and both the stories and the

manner of storytelling could be extremely individual, even idiosyncratic.

Teaming

with Bill Sienkiewicz, Miller continued in this vein with Daredevil: Love

and War in 1986 and Elektra Assassin later in the same year.

Sienkiewicz abandoned conventional linear comic book illustrative methods

altogether for both books: the panels were painted in full color, shapes and

figures defined and modeled by hues and tones rather than by line. His

treatment of the human face and form was stylized, wrenched into abstract

caricatures of the personalities of the characters. And raw imagery played a

narrative role in both stories.

Printed

in full color on glossy paper and square bound, both books reflected a growing

European influence. Starting in the mid-1980s, the higher production values of

European albums were more and more to be found on the American side of the

Atlantic. And as the decade drew to a close, another European practice was

becoming almost commonplace: increasingly, publishers re-issued a best-selling

series of comic books in a single bound volume, an "album," often

between hard covers and printed on higher quality stock than the original

printing.

The

European influence was manifest even more directly in the eighties: British

writers began producing stories for American publishers. While Miller was

doing Dark Knight, Alan Moore was writing Watchmen for

fellow Briton Dave Gibbons to draw. A twelve-issue series that started

in September 1986, Watchmen was built on the conceit that if superheroes

and costumed crime-fighters were real, they would probably be outlawed as

vigilantes. Setting his tale slightly into the future, Moore crafted a

multi-layered, densely textured story, as laden with leitmotifs both visual and

verbal as a James Joyce novel. The complexity of the storytelling made the

series an intriguing read, but Moore's conclusion did not live up to the

promise inherent in his premise. Although ostensibly debunking the superheroic

mythology (albeit affectionately), Moore was at last driven by its conventions

to end his story in a nearly traditional way.

But

he and Gibbons had demonstrated as never before the capacity of the medium to

tell a sophisticated story in ways that could be engineered only in comics.

And perhaps even more significantly, this complex work had been published by a

newsstand publisher, DC Comics.

Watchmen's success (it was subsequently reprinted, several times, as an “album”)— coupled

to that of Miller's Dark Knight— opened even wider the door in

commercial publishing for expression of a creator's personal vision.

Neil

Gaiman, another Englishman, soon began writing The Sandman, a

haunting series of tales in which a modern version of Morpheus lurks around the

edges of people's lives, uttering angst-laden psycho-profundities about the

futility and meaninglessness of life. Gaiman worked with different artists but

his best effects are achieved verbally, in the poetic images and philosophical

metaphors of his prose.

As

noted, the Watchmen/Dark Knight success had a profound effect on the

treatment of the comic book industry's patented icons, the superheroes. While

some of them got "darker," they all began to reflect the individual

vision of writers and editors rather than the corporate policy. Instead of

producing stories the substance of which was controlled by licensing

operations, the major publishers frequently permitted imaginative

re-interpretations of the superhero ethos solely in the interest of telling

good stories. (A laudable tendency that would be undercut and abandoned when,

in order enhance comic book sales, comic book publishers began to ape the

emerging movie versions of their superheroes.)

DC

even permitted Superman to be killed in the fall of 1992 in order to

reinvigorate the Man of Steel legend, the manner of reincarnation being the

chief appeal to the imagination. And Marvel successfully combined both

ambitious production values and revisionist mythology in the 1993 series called Marvels: in masterful full-color paintings (watercolor and gouache), Alex

Ross rendered Kurt Busiek's inventive retelling of the origins of

the Marvel Universe from the point of view of a newsman.

By

the dawn of the nineties, the various currents of creativity in the

storytelling tradition had come together to revitalize the commercial medium.

The figure drawing tradition, on the other hand, had evolved into Image Comics,

which was founded by artists who wanted ownership of their creations, which, at

the time, was not possible with mainstream publishers.

"Image"

said it all: at first, these comics are all picture and no story. Image Comics

benefitted from the pulse of individuality that coursed through the

storytelling tributary: without the idiosyncratic styling of Miller and the

poster-page design of Chaykin there may not have been any Image Comics. But

what might have been the eccentricities of individual styles elsewhere became a

house style at Image: many of the founding artists— Rob Liefeld, Eric

Larsen, Marc Silvestri— drew the human figure in the same monumental manner

with refrigerator torsos, elephantine limbs, and tiny pinheads. Several of the

artists even modeled forms with the same fine spray of line fragments. The

stylization of anatomy culminated in a rendering of facial expression which

consisted almost entirely of a single teeth-bearing grimace of rage.

The

founding artists of Image Comics defied the traditions of the industry by

proclaiming they didn't need writers. And since the artists had little

experience in writing stories, the first books they produced reflected their

visual bias: they produced pages that were designed as posters rather than as

increments in a storytelling process. Some of the titles featured teams of

superheroes in the Kirby tradition, but the Kirby influence seemed to end with

the concept: the covers and interiors of many Image titles depicted groups of

colossally proportioned characters in monotonous heroic poses, but these

larger-than-life figures had no life, no personalities.

Eventually,

the Image founders turned to writers to assist in constructing stories, but the

compelling attraction of the company's earliest titles resided in the visual

stylings of the artists. The founders were all "hot artists,"

artists whose graphic quirks in Marvel Comics had attracted enthusiastic and

vocal followings. Image Comics was essentially a banner under which the

artists collected in loose aggregation to produce comic books featuring their

creator-owned characters, thereby catapulting their box office appeal into

healthy bank accounts virtually overnight— again, thanks to the network of

direct sale shops that fostered the feverish passions of the fanatic collectors

who hoarded titles by their favorite artists.

The

prospect of cashing-in on creator-owned properties attracted other artists and

writers to the banner, but the initial success of the enterprise seemed to rest

entirely on the popularity of this artist or that, and, given the fickle

attention span of the American consumer, the future of Image Comics was, at

first, scarcely certain. Over the years, Image Comics secured a place in the

market with stories that were solid as well as superbly drawn. Long before

that, however, the phenomenon of Image Comics demonstrated a new economic truth

about the comic book marketplace: the direct sale shop network could create

millionaires.

If

the artistic energy of the figure drawing tributary seemed diverted into the

eccentric eddy of Image Comics, at first a mere backwater of creativity, the

storytelling tributaries converged into a confluence of growing narrative

power, bending all of the medium's devices to the task of telling a story. In

exploring the potential of the medium, the storytelling cartoonists seemed on

much firmer footing than the figure drawing artists as the century wound to a

close.

Feetnoot. The foregoing essay is ripped, almost

entirely, from a chapter in my book, The Art of the Comic Book, which, you

might know, is for sale hereabouts. Just go back to the first page and scroll

down to the pictures of book covers.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |