FIDDLEFOOT: A COMIC STRIP THAT NEVER WAS, ALMOST

A Shamelessly Self-indulgent Spasm Demonstrating

How the Happy Harv Invented a Comic Strip and Failed To Get It Syndicated

WARNING NOTE. What follows is such an extravagant indulgence that it is sure to be a model of tedious, boring exposition. It is likely to be of interest (assuming such a thing is at all possible) only to other cartoonists—if that. No other brand of being will be even remotely interested or nearly as fascinated by this plethora of detail as I am, revisiting the scenes of my own grippingly mundane past. Okay: you’ve been warned. Onward.

HERE HE

IS—the Fabulous Fiddlefoot, soldier of fortune, globe-trotting trouble-shooter,

rescuer of damsels, neighborhood knight errant, buckler of swashes—in short,

the personification of a mockery of adventure comic strips everywhere. Also, a

resounding failure of a strip. Well, maybe not so resounding; more like a

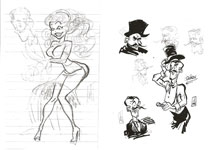

whimpering failure.  But as you can see in the accompanying portrait, Fiddlefoot is a

dashing comeuppance, failure or not. He has the jaunty air of a Hollywood hero,

a make-believe personal, more let’s-pretend than let’s-go-get-’em, a

role-player with his bon vivant role flung casually, albeit flamboyantly, over

his shoulders but not fully donned: the sleeves are empty but his arms are

free. Probably if I were to draw this picture today, I’d give him a slouchy

fedora to tip, not a toweringly comical top hat. But in those distant days of

aspiring yore, I liked funny tall top hats with decorative hat bands. Besides,

the hat and the Jack Davis feet gave him a comedic flare: he was a figure of

fun as well as a poseur par excellence.

But as you can see in the accompanying portrait, Fiddlefoot is a

dashing comeuppance, failure or not. He has the jaunty air of a Hollywood hero,

a make-believe personal, more let’s-pretend than let’s-go-get-’em, a

role-player with his bon vivant role flung casually, albeit flamboyantly, over

his shoulders but not fully donned: the sleeves are empty but his arms are

free. Probably if I were to draw this picture today, I’d give him a slouchy

fedora to tip, not a toweringly comical top hat. But in those distant days of

aspiring yore, I liked funny tall top hats with decorative hat bands. Besides,

the hat and the Jack Davis feet gave him a comedic flare: he was a figure of

fun as well as a poseur par excellence.

Fiddlefoot is the name of the comic strip and its protagonist, both concocted years ago—in the early 1960s, while I was still in the U.S. Navy, bounding over the heaving main (and vice versa). (I can’t remember which: it was, after all, but a fleeting thing.) Fiddlefoot is my fondest creation, a child of my yearning young heart, born when I fully expected to become a newspaper comic strip cartoonist, the culmination of my lifelong dream. I don’t remember when, exactly, I came up with the name Fiddlefoot. I probably saw it somewhere and thought it was perfect for the hero of an adventure strip parody I persisted in imagining. “Fiddlefoot” evoked “footloose,” implying carefree vagabondery but with a lamination of silliness. Just right for parody, methought.

“Parody” is perhaps not the most accurate word for the strip I was dreaming about: “parody” implies satirical intent, and my intention in conjuring up FF (as I dubbed him) and his band of luckless merry men was to do a humorous adventure strip. Not exactly Li’l Abner (which was laden with satire); more like Cecil Jensen’s Elmo, the tale of a simple-minded but good-hearted chap.

My Fiddlefoot was also a little simple-minded: he wanted to be a hero, and he and his closest cohort, a diminutive rolling stone named Threadbare (another name I borrowed from some forgotten source), thought the heroing business was largely a matter of rescuing damsels. Otherwise unemployable, FF and Threadbare lurked along the byroads of the mind, looking for distressed young women. That was floating in my mind as I floated the blue Mediterranean aboard the USS Saratoga (CVA-60, as they say).

The floating went on for over three years, albeit in other places as well as the Med. And all that time, I was thinking about Fiddlefoot, his pals, his locale, his desires, his plans, his assorted fates and frolics. He was a presence in my life: if not at my side, at least inside. He lived with me longer than any other cartoon character I invented—hence, my favorite creation.

I daydreamed about Fiddlefoot and his misadventures in my spare moments, and I spent many happy hours sketching him—depicting a gamut of facial expressions, imagining different uniforms or costumes (a different one for every adventure, I mused). Much to my stupefaction, I recently discovered a cache of these notations, tucked away in a box of naval memorabilia. And here are some of them.

|

|

|

|

IN CREATING THE CHARACTER, as you must suppose, I started with his face, and the face went through several evolutions before I arrived at the one I liked the best. You’ll notice right away a startling feature that made Fiddlefoot look different from any other comic strip hero: his hairline is receding, the front rapidly approaching the rear (a metaphor, perhaps, for his every endeavor?). He’s definitely losing his hair. So was I, but not (at that time) as noticeably, so I was not the model for FF. Besides my baldness followed a different pattern.

At first, as you can see, Fiddlefoot’s was a somewhat square-jawed visage, but the square soon evolved into a lantern, and about the same time, the only lock of hair on top of his skull took less and less space, exposing more baldness, and that solitary wisp of hair became a little unruly, waving frantically in the breeze. The more I drew him, the looser the sketches became, embodying a visual energy that I have always wished I could preserve in inking such lively pencils. I’ve seldom managed to achieve this fond goal as persistently as I wished for it.

I can look at these drawings now, fifty years after making them, as if they are the work of someone else. They aren’t mine. As anyone who draws for publication can tell you, when a drawing graduates into print, it loses its personal aura: it is no longer connected to its maker, nor he (or she) to it: it becomes an alien fabrication, a foreign object dropped into print, willy nilly, fugitive from a distant planet, not from your drawing board. And so you can gaze upon your creation dispassionately, with complete detachment, seeing flaws that weren’t so obvious when you first made the picture. Seeing, too, virtues and successes of symmetry in composition or vibrancy in line where before you saw only solutions to visualizing problems. Thus, everyone who draws for publication quickly becomes his or her own worst critic. And, often, their own best admirer, too.

And if we add fifty years between the time of doing the drawing and the time of perceiving its publication here in the digital ether, the disconnect is almost complete. When I say I like these lively pencil lines, they’re not my lines anymore. And because these drawings are no longer psychologically “mine,” I can admire their triumphs and animating nuances unabashedly, without the sort of hesitation that a becoming modesty would otherwise impose. And so I can admire that vivacious pencil line I mentioned—its kinetic excitement, its vigorous flourish. And I invite you to do the same as we pour over the physical evidence of Fiddlefoot’s history. (This display is excessive, I realize; but it’s my website, and I get to do what I want to do. Besides, I warned you that this installment was shamelessly self-absorbed. So put on your big boy pants and read on without further ado.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

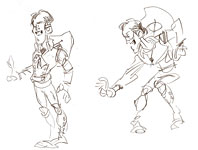

I DREW FIDDLEFOOT IN A VARIETY OF POSES and wearing many costumes. Although he appears sometimes in a suit, I liked him in skin-tight leggings rather than trousers. And his most frequent wardrobe was inspired by the leatherstocking garb of antique western characters. Dunno why I always imagined my heroes (FF was not the first, kimo sabe) playing the piano, but I did. An odd conjuration because I do not myself play the piano. Only my heroes do. Rachmanoff and Beethoven, mostly.

FF’s facial expressions were placid most of the time—good-hearted but vacuous, I’d say—but I was careful to develop a fierce crime-fighting frown, too, with FF glowering out at the bad guys. As I sketched Fiddlefoot cavorting across the page, my storytelling engine was idling, and I heard him speaking—soliloquizing sometimes, sometimes talking to Threadbare or snarling at cads or yelling at evil-doers. He was coming alive in my head.

To complete his role as a trouble-shooter, I developed an insignia, which might’ve been emblazoned on the chest of his jacket—but never was. Maybe later.

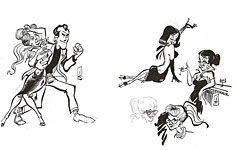

And Fiddlefoot’s friends and companions began to coalesce around my drawings of him. The perpetual innocent Threadbare was first. Then the swaggering Dunston Barswig (an incarnation of Cumshaw; see below), then the W.C. Fields lookalike, and the diminutive wise guy, a bellhop named Buttons (who changed his name later to Two-Bits). And the villains, moustachioed and leering.

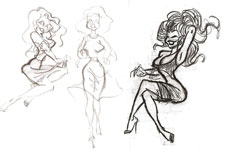

And girls. Of course, girls. There had to be damsels to rescue. Cute and wholesome. But some of them were menaces rather than muenchs. Villainesses, femmes fatales. And one, the perky one with glasses, was, perhaps, another cohort, a canny newspaper reporter possibly.

Eventually, as Fiddlefoot came more and more alive, I was less and less amused in confining his activities to sketches on my desk. At the time, I was drawing a full-page comic strip (sometimes 2-3, even 4, pages long) for the ship’s monthly magazine. It starred a laggard sailor named Cumshaw, whose name—meaning “to obtain through unofficial channels”—thoroughly and succinctly describes him, his personality and his goals in life.

|

|

|

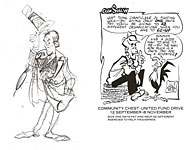

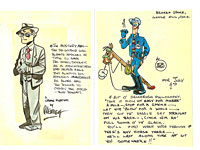

Sometimes

instead of the Cumshaw strip, I drew Cumshaw panel cartoons. And

sometimes I was called upon to produce public service advisories like the page

near here about how to behave when ashore in a foreign country.

For this full-page multi-panel cautionary playlet, I drafted Fiddlefoot, giving Cumshaw a day off. (Oh—the BB in Cumshaw’s company is, of course, Brigit Bardot, celebrated French sex kitten of the sixties. How Cumshaw attracted her attention—well, that’s Cumshaw for you.)

The ever effervescent comics critic in me (as opposed to the shy, retiring cartoonist in me) draws attention (rather than pictures) to the verbal-visual blending on this page: the pictures add a layer of meaning to the words that the words do not intend. I was entirely conscious of this counterpoint when doing it: that was, of course, the comedy of the piece. But cartoonists are not always perfectly aware of the convolutions of what they’re doing.

I

roped FF into this production because I wanted to see how he looked in print.

It was for this effort that I did the drawing that began this disquisition.

How I

managed to flop the pencil, reversing the picture, I can’t remember. Tracing it

in reverse, I suppose; digital machinery of the sort that does the job nowadays

didn’t exist then. I like particularly the way the folds in the coat fell into

place. Almost effortlessly it would seem: this appears to be the first draft of

the picture, and I don’t see many lines searching for resolution. The flare of

the coat collar—it all worked, amazing me now, five decades later; I’m amazed

because I would not have thought, without evidence, that I was good enough to

get the thing done so deftly. I think of myself as a much clumsier cartooner.

(And nowadays, I am.)

How I

managed to flop the pencil, reversing the picture, I can’t remember. Tracing it

in reverse, I suppose; digital machinery of the sort that does the job nowadays

didn’t exist then. I like particularly the way the folds in the coat fell into

place. Almost effortlessly it would seem: this appears to be the first draft of

the picture, and I don’t see many lines searching for resolution. The flare of

the coat collar—it all worked, amazing me now, five decades later; I’m amazed

because I would not have thought, without evidence, that I was good enough to

get the thing done so deftly. I think of myself as a much clumsier cartooner.

(And nowadays, I am.)

Sometimes, with Cumshaw back on duty, the public service aspect of his work was of the traditional sort—fund raising for worthy causes, as we see in the poster for the Community Chest-United Fund drive next to the penciled Fiddlefoot in this visual aid.

I

was still impatient to begin Fiddlefoot’s adventures even though I was fully

employed aboard ship, and I finally surrendered and drew a single strip, Fiddlefoot

Fables No.1, that I used as a letterhead on letters home.

I was happy with this little enterprise: it enthused the antic joy I wanted in the strip, embodying, at the same time, a gleeful self-deprecating parodic satire. Again, as in “Conduct Ashore,” the verbiage is contradicted by the pictures, hence the comedy. In case you can’t read the captions in this less-than-satisfactory reproduction, they are: Here the mighty Fiddlefoot—knight errant and globe-trotter—brooding with his motley band of ne’er-do-wells ... here, the damsel fair, menaced by villain foul ... here is the bold rescue with trumpets sounding ... and here is the happy ending as damsel fair gratefully melts into the strong arms of hero bold (who is saying, “Such adoring [ouch] gratitude ... such defenseless femininity...”; as she yells, “Put me down!”). The moralizing conclusion: Beware the damsel whose distress is only skin deep.

I like the trumpet. I always like the trumpet.

I like all the pictures. Fiddlefoot’s jaw is still a little in the squared condition, and his costume is more in the vein of Wally Wood’s Mad spoof of Blackhawk, but it suits the occasion. Cumshaw/Dunston is dressed as a hill bandit here; he wouldn’t again don this garb. The villain is appropriately villainish; I like the way his striped trousers work. And I like the girl lifting her skirt, too; but even more, her roundhouse swing in the next panel, the speed lines tracing the arc of the swing and smokin’ en route. I also like the tight skirt

With this effort, my exploration of the Fiddlefoot psyche ceased for a time. But I still drew a few pictures of him for shipboard service publications, as we see hereabouts.

|

|

The public relations officer aboard ship produced pamphlet guides to the ports where we anchored from time to time; and I used Fiddlefoot to decorate some of the covers. When we anchored at Livorno, I nodded at Bill Mauldin with the visual, but at most other ports of call, I seized the opportunity to examine the indigenous curvaceous gender’s curvaceousness. We visited Cannes twice, and on the second visit, I repeated the situation depicted here but with Fiddlefoot wearing a 1900s bathing costume that covered up everything from clavicle to knee-cap. I don’t think I had anything at hand as a model for the camel, so I’m amazed that I could conjure up the beast’s typical splay-footed stance and toothy grin.

When the Saratoga’s Mediterranean tour was over, we were “relieved” by another aircraft carrier, and all Sara’s departments produced documents intended to acquaint the new bunch with the intricacies of operations in the Med. These documents were called “turn-over files” because in them, we turned over to the new crew the information we’d gleaned over the previous 6-8 months. I’m particularly fond of the cover I did for the Supply Department’s Turn-Over File. And in the department’s division chapters, I deployed Cumshaw as the know-it-all sailor with Fiddlefoot playing the part of a somewhat less savvy supply officer.

Apart from such cameo appearances, I didn’t draw FF much more while in the Navy. And I didn’t cast him in the comic strip role I imagined for him until I got out of the Navy and went to live with my parents for a short time.

I wanted the time—full-time, every day—to develop the comic strip, and since I’d saved enough money that I didn’t need to find gainful employment right away, I retired to my studio in the basement of my parents’ home and pretended I was doing Fiddlefoot full-time. The question was: could I produce a comic strip a day, the minimum required of a syndicated cartoonist. After a few weeks, I knew I could do it.

I prepared what was then called a “presentation booklet”—a multi-page pamphlet designed to sell the comic strip to syndicate officials. I’d seen one such confection years before and understood it to be typical. Adopting it as a model, I produced my own, including six weeks of the comic strip, prefaced by pages that introduced the characters. Herewith, the whole enchilada, page by page, punctuated only occasionally by comments and explications on the sidelines or between the strips. Only nine of the 36 strips are finished art. The purpose of the booklet was to demonstrate that I could tell a story (or jokes), and six weeks’ worth of strips should be adequate to the task, I thought. But those strips needn’t all be finished art in order to demonstrate that I could tell a story or a joke: rough sketches could do that, and so, to save myself some labor, I did roughs for all but the nine aforementioned strips. And those would demonstrate that I could draw respectable pictures.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

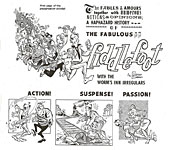

I ADMIRE THE TITLE PAGE of the booklet: the lettering of the Fiddlefoot logotype, the mob scene at the heels of FF, the trumpet held aloft. But more than that, I like the vignette panels across the bottom of the page. In the first, Fiddlefoot looks appropriately (comically) discombobulated by his surprising achievement; the second spoofs the traditional Perils-of-Pauline dilemma, with FF tangled in the ropes that bind the damsel, and the damsel seductive in her Daisy Mae blouse and form-fitting skirt. But the third panel, I dearly love: the girl, fetching in form and pose, is clearly the stronger of the two personages (I particularly like the way her toes turn inward as she braces herself to keep FF from falling to the ground); and the expression on Fiddlefoot’s face is exactly right for the sort of girl-shy do-gooder he is.

In

the opening sequence, two weeks’ worth of strips, I was clearly inspired by

Milton Caniff’s introductory Steve Canyon week. He went the whole week

without Steve Canyon showing up; readers didn’t see the title character until

the seventh day, Sunday. The strategy was to prolong suspense by delaying what everyone

expected; and with Steve Canyon, expectations were high because

publicity about Caniff’s leaving Terry to start a new strip had been

widespread. Understandably, given Terry’s popularity, everyone wanted to see

what the new Caniff hero would look like. Caniff was also toying with his fans:

he knew they’d been waiting for over a year, so he fiendishly decided to make

them wait yet another week. And he was expert enough at the craft that he could

get away with it.

The strategy was to prolong suspense by delaying what everyone

expected; and with Steve Canyon, expectations were high because

publicity about Caniff’s leaving Terry to start a new strip had been

widespread. Understandably, given Terry’s popularity, everyone wanted to see

what the new Caniff hero would look like. Caniff was also toying with his fans:

he knew they’d been waiting for over a year, so he fiendishly decided to make

them wait yet another week. And he was expert enough at the craft that he could

get away with it.

Impressions you may have formed to the contrary notwithstanding, I didn’t imagine myself the equal of Caniff at comic strip storytelling, but with the arrogance of youth, I couldn’t help but try his dodge. So I went Caniff one better: it isn’t until the eighth Fiddlefoot strip that we see the character who, by now—thanks to the effusive praises sung by his followers at Worm’s Inn—is fabulous (the stuff of fables) indeed.

Without FF on the scene, I knew I had to do something in the opening strips to attract and then hold reader interest. The first strip offers cute Threadbare but, even cuter, a toothsome damsel in flaring skirt and dipping decolletage, the latter, a motif continued in the third strip. As a sometime comics critic, I’m pleased to note that the words and pictures often blend for the comedy (often but not always; some of the jokes are entirely verbal).

The two strips leading directly to Fiddlefoot’s inaugural appearance—the seventh and eighth strips—are nice examples of words and pictures working in tandem, it seems to me. (But it would, wouldn’t it?) My homage to Caniff is evident as Fiddlefoot pushes through the Worm’s Inn’s swinging doors: he’s wearing the coat Steve Canyon wore on his painfully postponed debut in that seventh (Sunday) strip.

By the next strip—Fiddlefoot’s recitation of his Oriental adventure—I’m running off at the mouth: it’s entirely too verbal (in imitation of S.J. Perelman, a verbal not a visual whiz). But it also serves to display a variety of FF’s facial expressions. But adroit verbal-visual blending resumes with the next three strips.

I can readily identify Perelman as an inspiration for this passage, but I can’t tell where much of the rest of these opening strips—or those that follow—came from. I can’t tell because I don’t know. I don’t know in any specific Perelmaniacal way where the gags came from or how they came into being or why the plot unwinds between the hiccoughs of the daily punchlines. As I discovered when doing that 24-hour comic last fall, the ideas come out of the drawing—not the pictures but the process. You have a vague idea of the direction of your story, and as you draw pictures to take you down that route, you have incidental ideas; they sprout from the characters, from what they say and from how they interact. The jokes and plot twists arise as you do the strip.

But enough—enough blow-by-blow, enough idiotic introspection, enough verbal attitudinizing. Onward to our final flourishes.

So what became of this masterpiece? To begin with the obvious, it didn’t sell. None of the syndicates to which I showed it were interested. Generally speaking, the reaction was negative because syndicates at the time believed that continuity strips, strips that told a story that continued from day-to-day like Fiddlefoot, were no longer popular with newspaper editors. Since the advent of nation-wide television in the mid-1950s, editors believed that erstwhile continuity strip adherents were finding visual storytelling on tv, where they could get the entire story in thirty or sixty minutes. So why would they want to read a storytelling comic strip that took six weeks or more to tell its tale?

Instead of seeing the fallacy in this so-called reasoning, editors seemingly believed that spectators found greater pleasure in 30- to 60-minute doses and none at all in the serial form that took several weeks to unfold. Somehow, time and enjoyment were equated in a perverse rationale—as if quick copulation were more pleasurable than a prolonged fuck. (See the fallacy now?)

The popularity of endlessly continuing soap operas on daytime tv escaped their attention; it wasn’t until “Dallas” became the first prime-time serial show that some editors might have been persuaded to abandon their weird logic. By then—the 1980s—the damage had been done: the continuity comic strip was all but dead all over, surrendering its space in the comics section to strips that told a joke-a-day.

To be scrupulously fair, newspaper editors in the mid-1960s when I was trying to sell Fiddlefoot weren’t untrammeled idiots: they feared that newspapers would be replaced by television, and their fear was so great that they couldn’t see past it to the fallacy in their thinking. Eventually, editors lost some measure of their terror. Knowing they couldn’t beat television or join it, they began publishing tv schedules and articles about tv shows, making themselves essential to tv viewers by providing the ever-intriguing peripheral “news” about the rival medium.

I’m not sure newspaper editors have learned much by their experience. Today they are as terrified of the Internet as they were once boggled by television. But instead of making newspapers somehow essential for maximum enjoyment of the Web, newspapers are converting to websites themselves—effectively not just signing their own death warrants but writing them, too.

The continuity of Fiddlefoot was not the only strike against it, however. At the first syndicate to which I took it, Field Enterprises at the Chicago Sun-Times, the editor looking at the strip thought the art was too busy. He was doubtless right. In an age of 3-4 panel strips, I was producing 4-5 panel strips, and the drawings were thus crammed into smaller spaces than other strips, making the visuals seem busy. And I had also been smitten by a line of greeting cards then very popular: in them, cartoonists embroidered their drawings with decorative patterns, and when I did the same, say to Fenderfroth’s vest, it simply increased the visual complexity of the picture. I took this sort of criticism to heart and went home and devised another humorous adventure strip, Heroes League, which starred a Fiddlefoot-looking character but was drawn without embroidery and in 3-4 panels a day instead of 4-5. But that’s another story for another day.

Two other syndicate visits, both in New York, I remember clearly. At King, where the review of my presentation book took place while standing in an elevator lobby and was conducted by what I’ve since decided was probably a retouch factotum from the bullpen, the reviewer, after flipping a few pages of the booklet without reading, explained that King wasn’t buying strips:

“We have so many strips out there,” he explained, “that any new strip we would sell would result in one of our older strips being kicked out of the paper to make room for the new one. Why bother?”

Made sense to me, even if it wasn’t the real reason he was rejecting my strip.

THE OTHER VISIT I remember yields the Elaborate Explanation of the footnotes embedded among the strips. This was Bell Syndicate. As in other instances, I dropped off the presentation booklet one week and returned for the verdict the next week. (In between, I was taking graduate courses in English literature at New York University, should you be wondering how I filled my otherwise idle hours. But that’s another story for another day, too.)

When I returned to retrieve the presentation booklet, the editor who brought it out to me surprised me with a question:

“Have you ever seen the Spirit by Will Eisner?” he asked.

Of course, I had. I’d had one single copy of Police Comics in my possession at the time, and I’d repeatedly savored the Spirit story within (“Beagle’s Second Chance” from The Spirit Sunday supplement, November 3, 1946; reprinted entirely in one of my books, The Art of the Comic Book). As you can tell from the Eisner Moments noted among the strips, I’d lifted the design of the window in Worm’s Inn from the Spirit’s underground lair in Wildwood Cemetery. And the design was so distinctive that anyone familiar with Eisner’s work would immediately recognize the theft. At the time that I was committing the crime, however, the Spirit had been off the radar (I supposed) for at least a decade; and in l963-64, fandom had yet to resurrect the Spirit or Eisner. So who would know I’d copied the window design? (I also copied the action in another panel, as noted; but that wasn’t as distinctive as the window design.)

And so I responded to the man’s question with a straight-forward:

“What? Who? The Spirit? What’s that? Eisner? Who’s he?”

Bald-faced evasion—well, a lie.

Little did I know that at that very moment, the president of Bell Syndicate was (insidious pause) Will Eisner.

The wages of sin—an unsold comic strip.

Years

later, when I met Will, I told him the story, and we both laughed. I doubt he

remembered the  incident; maybe he never even saw my presentation booklet.

incident; maybe he never even saw my presentation booklet.

So enamored of the Spirit was I in those days (and, even, now) that I copied the character himself every once in a while.I did better on the picture at the left: the mask is good. The earlier rendering on the right uses only the Spirit mask. Long after my encounter with Bell Syndicate, I sent Will copies of these pictures, just to show how sincere was my admiration: the sincerest form of flatter is, after all, imitation.

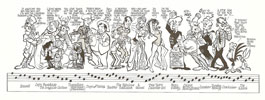

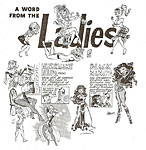

BY THE WAY, I mentioned earlier that Fiddlefoot was only one of several characters I invented over the years. Each of them served a different purpose. Here, at your elbow, they are gathered to perform an anyule ritual, the Christmas pageant (a greeting card of my own devising).Left to right, they are:

Yrs Trly, in Victorian carolers’ garb for the occasion.

Captain Broadside, the commanding officer of the ship to which Cumshaw was attached; modeled on famed actor Charles Laughton.

The Irregular Urchins, one of whom showed up in a Cumshaw Christmas strip and both in the final strip of the Fiddlefoot presentation book; but neither of these appealing youngsters ever appeared anywhere else.

Threadbare, who I liked so much that I gave him parts in several of my strip efforts: he was Nonfat (a reference to the milk that the Navy served) in the strip I did at Supply Corps School; and he was Blackbeard the pirate in Cumshaw.

Dupin and Dooley were created in my senior year in high school; I hoped to do a comic strip about them while in college. No luck. The names, incidentally, are Anglicized versions of French for bread and milk (du pan and du lait).

Two-Bits the bellhop was a character in Fiddlefoot, appearing in sketches as Buttons.

Fiddlefoot in his squarer jaw incarnation.

A damsel—for Fiddlefoot to rescue, what else?

And what else is This Year’s Calendar Girl? No Harvey artifact is complete without one.

Beau Sandy, the eponymous star of the Supply Corps School strip, his name evokes the Navy’s Bureau of Supplies and Accounts (abbreviated BuSandA) that governed the Supply Corps, but Beau, as befits a man with that name, is more interested in what fills short skirts than in filling out long forms.

Colonel Pendingbask is what’s left of the W.C. Fields character who, in Fiddlefoot, was named Wister Pendingbask Fenderfroth. Great name for a bumptious blow-hard of a personality. I loved him.

Cumshaw in dress blues for the holiday.

Dunston Barswig, whom many in college thought was merely me in my cups; maybe they where right.

Chanticleer was the “fighting cock,” mascot of the USS Saratoga, a character integral to the adventures of Cumshaw.

And the Rabbit. Well, we know he’s called Cahoots, but that’s not his name. His name, as we’ve explained before, is Harvey.