|

EASTER AND

OTHER RABBITS

A Short

History of Origins and of My College Cartooning Career

(The Latter,

in Celebration of Completing the 18th Year of Rancid Raves)

SINCE I’VE BEEN

CARETAKER of one of the long-eared critters almost all my life (“almost”

because I still have some yet to live), you’d think the Easter Bunny would have

attracted my analytical attention before now. But it hasn’t. And yet every year

we pass through another Easter, dying eggs and indulging a species of

cannibalism by eating chocolate bunnies. We look forward every year to the

arrival of this holiday, hoping that this year, we’ll see the Easter Bunny

suitably attired in red short pants, white three-finger gloves, and giant

yellow shoes. Our hope, of course, is in vain: the cotton-tailed leporidae

re-appears faithfully in fur and only fur from head to paws. SINCE I’VE BEEN

CARETAKER of one of the long-eared critters almost all my life (“almost”

because I still have some yet to live), you’d think the Easter Bunny would have

attracted my analytical attention before now. But it hasn’t. And yet every year

we pass through another Easter, dying eggs and indulging a species of

cannibalism by eating chocolate bunnies. We look forward every year to the

arrival of this holiday, hoping that this year, we’ll see the Easter Bunny

suitably attired in red short pants, white three-finger gloves, and giant

yellow shoes. Our hope, of course, is in vain: the cotton-tailed leporidae

re-appears faithfully in fur and only fur from head to paws.

This

year, however, the Easter Bunny came in at the back door during my spasm of

outrage that my church has surrendered to a spurious but apparently fashionable

brand of political religious correctness: they’ve started calling Easter by

another name—Resurrection Sunday—because, I assume, Easter is a word with a

pagan (or at least non-Christian) history that the Rectitudinally Faithful wish

to disassociate their pure religion from.

Naturally,

I deem this effort as not only misguided but misbegotten. “Easter,” the word as

well as the holiday, has a history, and to consign the word to Limbo is to deny

history—which, in this case, seems to me like denying the religion it’s

associated with.

The

history of a religion tells us a lot about the people—the societies—in which

the religion flourished. And vice versa: we learn a lot about religion by

examining its history.

In

Greek mythology (as good a religion as any in its day), Zeus, the patriarch of

the pantheon, had many wives. Why? The reason is hidden in the history of the

religion.

In

the earliest times, Zeus was the god of nomads who roamed and conquered their

region. The other occupants in the vicinity were agricultural societies that

survived and thrived by planting and harvesting crops. They worshiped a goddess

because the female of the species, giving birth to others of the species from

time to time, was seen as mysterious (no one had yet explained how human reproduction

worked) and therefore powerful. Women represented the fertility of the soil and

the fecundity of Nature.

When

the nomads wandered into a farming valley and conquered its occupants, they

needed to deal with the local goddess in some way that would appease the

agriculturists without discrediting their goddess or belittling their belief.

The best way to manage this was to have the two gods marry. Since the nomads

conquered several agricultural communities in succession, Zeus wound up with

several wives.

Many

religions had to settle a similar problem. The Jews resolved the matter by

discrediting the goddess, turning her into Eve who was responsible for Adam

being banished from the Garden of Eden. As Christianity spread from the Mideast

throughout the known world, it picked up pieces of pre-Christian (i.e.,

pagan—or, gasp, heathen!) culture as it went along. And “Easter” is a remnant

of that evolution.

To

get to the Easter Bunny, we must first plow through fragments of the history of

Easter. St. Wikipedia is our guide throughout, and I’ve quoted nearly verbatim

from several entries without crediting anyone (just as St. Wikipedia often

does).

To

begin with the touchstone that orients us to Easter itself: the argument of the New Testament is that the resurrection of Jesus is a foundation of the

Christian faith, and the resurrection is what Easter celebrates. But Easter

originally had nothing to do with Christ (although it did have something to do

with resurrection—the rebirth or resurrection of all Nature in the spring of

every year).

In

a holdover from those primitive agricultural societies, European pre-Christian

religions celebrated the fertility goddess Eostre (Ostara in continental

Europe).

The

modern English term Easter, cognate with modern Dutch ooster and

German Ostern, developed from an Old English word that usually appears

in the form Ēastrun, -on, or -an; but also as Ēastru, -o; and Ēastre or Ēostre. The most widely

accepted theory of the origin of the term is that it is derived from the name of

a goddess mentioned by a 7th/8th-century English monk named Bede, who wrote

that Ēosturmōnaþ (Old English 'Month of Ēostre',

translated in Bede's time as "Paschal month") was an English month

corresponding to April, which he says "was once called after a goddess of

theirs named Ēostre, in whose honor feasts were celebrated in that

month."

However,

saith St. Wikipedia, it is possible that Bede was only speculating about the

origin of the term since there is no firm evidence that such a goddess actually

existed.

Well,

okay. But how come, then, so many entries about Easter mention her? Perhaps the

mentions themselves constitute all the “firm evidence” of her existence there

is. Stranger things have happened.

In

any event, the reports claim that Eostre/Ostara was celebrated by pre-Christian

religions on the first day of spring (vernal equinox) because that is when the

days are getting notably longer than nights and the nature “wakes up.” Since

Christian celebration of Christ’s resurrection was roughly coincident with the

celebration of Eostre, the customs started mixing: “waking up” and

“resurrection” became rough equivalents, each reinforcing the other. And so

pre-Christian notions slowly became Christian ones. Just as Jewish notions

slowly became Christian ones.

In

Greek and Latin, the Christian celebration was, and still is, called

Πάσχα, Pascha, a word derived from Aramaic

פסחא, cognate to Hebrew

פֶּסַח (Pesach). The word originally

denoted the Jewish festival known in English as Passover, commemorating the

Jewish Exodus from slavery in Egypt. Already in the 50s of the 1st century, the

apostle Paul (who did more to create the Christian religion than anyone),

writing from Ephesus to the Christians in Corinth, applied the term to Christ,

and it is unlikely that the Ephesian and Corinthian Christians were the first

to hear Exodus 12 interpreted as speaking about the death of Jesus, not just

about the Jewish Passover ritual.

In

most of the non-English speaking world, the feast is known by names derived from

Greek and Latin Pascha. Pascha is also a name by which Jesus himself is

remembered in the Orthodox Church, especially in connection with his

resurrection and with the season of its celebration.

Easter

is linked to the Jewish Passover by much of its symbolism, as well as by its

position in the calendar. In many languages, the words for "Easter"

and "Passover" are identical or very similar. Easter customs vary

across the Christian world, and include sunrise services, exclaiming the Paschal

greeting, clipping the church, and decorating Easter eggs (symbols of the empty

tomb). The Easter lily, a symbol of the resurrection, traditionally decorates

the chancel area of churches on this day and for the rest of Eastertide.

Additional customs that have become associated with Easter and are observed by

both Christians and some non-Christians include egg hunting, the Easter Bunny,

and Easter parades. There are also various traditional Easter foods that vary

regionally.

Easter’s

link to the Passover and Exodus from Egypt is recorded in the Old Testament through

the Last Supper and the sufferings and crucifixion of Jesus that preceded the

resurrection. According to the New Testament, Jesus gave the Passover

meal a new meaning, when, in the upper room during the Last Supper, he prepared

himself and his disciples for his death. He identified the matzah and cup of

wine as his body soon to be sacrificed and his blood soon to be shed. Paul

states: "Get rid of the old yeast that you may be a new batch without

yeast—as you really are. For Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed.”

This refers to the Passover requirement to have no yeast in the house and to

the allegory of Jesus as the Paschal lamb.

One

interpretation of the Gospel of John is that Jesus, as the Passover lamb, was

crucified at roughly the same time as the Passover lambs were being slain in

the temple, on the afternoon of Nisan 14. The scriptural instructions specify

that the lamb is to be slain "between the two evenings," that is, at

twilight. By the Roman period, however, the sacrifices were performed in the

mid-afternoon.

This

interpretation, however, is inconsistent with the chronology in the Synoptic

Gospels. It assumes that text literally translated "the preparation of the

passover" in John 19:14 refers to Nisan 14 (Preparation Day for the

Passover) and not necessarily to Yom Shishi (Friday, Preparation Day for the

Passover week Sabbath) and that the priests' desire to be ritually pure in

order to "eat the passover" refers to eating the Passover lamb, not

to the public offerings made during the days of Unleavened Bread.

The

first Christians, Jewish and Gentile, were certainly aware of the Hebrew

calendar. Jewish Christians, the first to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus,

timed the observance in relation to Passover.

Direct

evidence for a more fully formed Christian festival of Pascha (Easter) begins

to appear in the mid-2nd century. Perhaps the earliest extant primary source

referring to Easter is a mid-2nd-century Paschal homily attributed to Melito of

Sardis, which characterizes the celebration as a well-established one. Evidence

for another kind of annual Christian festival, the commemoration of martyrs,

begins to appear at about the same time as does evidence for the celebration of

Easter.

Easter

and the holidays that are related to it are moveable feasts which do not fall

on a fixed date in the Gregorian or Julian calendars that follow only the cycle

of the sun; rather, its date is determined on a lunisolar calendar similar to

the Hebrew calendar. The First Council of Nicaea (convened by Emperor

Constantine in A.D.325) established two rules, independence of the Jewish

calendar and worldwide uniformity, which were the only rules for Easter

explicitly laid down by the Council. No details for the computation were

specified; these were worked out in practice, a process that took centuries and

generated a number of controversies, but Christian dignitaries decided that

from then on, Easter will be celebrated on the first Sunday after the full moon

in spring (i.e., after spring solstice) or soonest after March 21, but

calculations vary. (Full moon? How pagan is that?)

After

Nicaea, Constantine sent a charming letter to all Church fathers who were not

present at Council explaining that this decision was necessary because “… it is

our duty not to have anything in common with the murderers of our Lord [i.e.,

Jews].” Clearly a sort of afterthought: however much Constantine wanted to

divorce the Christian celebration from the Passover celebration of the Jews,

the two holidays remain, to this day, often convergent. At that time there was

no written mention of eggs or bunnies being in any way related to Easter. But

that was coming along.

The

more cultures that embrace an idea or are embraced by it, the more universal

and relevant to humanity in general a religion becomes—hence the value of

histories of religion with their long-forgotten fragments of bygone beliefs and

traditions, pagan, heathen, whatever we call them. Mashed-up together, they

embody our commonality.

The

Easter Bunny (at last)

The Easter

Bunny (also called the Easter Rabbit or Easter Hare) is a folkloric figure and

symbol of Easter, depicted as a rabbit bringing Easter eggs.  Originating among German

Lutherans, the "Easter Hare" initially played the role of a judge,

evaluating whether children were good or disobedient in behaviour at the start

of the season of Eastertide. Originating among German

Lutherans, the "Easter Hare" initially played the role of a judge,

evaluating whether children were good or disobedient in behaviour at the start

of the season of Eastertide.

The

Easter Bunny is sometimes depicted with clothes. In legend, the creature

carries colored eggs in his basket, candy, and sometimes also toys to the homes

of children, and as such shows similarities to Santa Claus or the Christkind,

as they both bring gifts to children on the night before their respective holidays.

The custom was first mentioned in Georg Franck von Franckenau's De ovis

paschalibus (“About Easter Eggs”) in 1682 (other sources cite 1678),

referring to a German tradition of an Easter Hare bringing Easter eggs for the

children.

The

role of eggs in celebrating Easter is shrouded in a tradition having to do with

diet. Orthodox churches have a custom of abstaining from eating eggs during the

fast of Lent. The only way to keep the uneaten eggs from being wasted was to

boil or roast them, eating later when breaking the fast.

As

a special dish, they would probably have been decorated as part of the

celebrations. Later, German Protestants retained the custom of eating colored

eggs for Easter, though they did not continue the tradition of fasting. Eggs

boiled with some flowers change their color, bringing the spring into the

homes, and some over time added the custom of decorating the eggs.

Many

Christians of the Eastern Orthodox Church to this day typically dye their

Easter eggs red, the color of blood, in recognition of the blood of the

sacrificed Christ—and of the renewal of life in springtime. Some also use the

color green, in honor of the new foliage emerging after the long-dead time of

winter. The Ukrainian art of decorating eggs for Easter, known as pysanky,

dates to ancient, pre-Christian times. Similar variants of this form of artwork

are seen amongst other eastern and central European cultures.

The

idea of an egg-giving hare was transported to the U.S. in the 18th century.

Protestant German immigrants in the Pennsylvania Dutch area told their children

about the "Osterhase" (sometimes spelled "Oschter

Haws"). Hase means "hare", not rabbit, and in Northwest

European folklore the "Easter Bunny" indeed is a hare. According to

the legend, only good children received gifts of colored eggs in the nests that

they made in their caps and bonnets before Easter.

In

ancient times, it was widely believed (as by Pliny, Plutarch, Philostratus, and

Aelian) that the hare was a hermaphrodite. The idea that a hare could reproduce

without loss of virginity led to an association with the Virgin Mary, with

hares sometimes occurring in illuminated manuscripts and Northern European

paintings of the Virgin and Christ Child. It may also have been associated with

the Holy Trinity, as in the three hares motif. Eggs, like rabbits and hares,

are fertility symbols of antiquity. Since birds lay eggs and rabbits and hares

give birth to large litters in the early spring, these became symbols of the

rising fertility of the earth at the Vernal Equinox.

Rabbits

and hares are both prolific breeders. Female hares can conceive a second litter

of offspring while still pregnant with the first. This phenomenon is known as

superfetation. Lagomorphs mature sexually at an early age and can give birth to

several litters a year (hence the saying, "to breed like rabbits" or

"to breed like bunnies"). It is therefore not surprising that rabbits

and hares should become fertility symbols, or that their springtime mating

antics should enter into Easter folklore.

In his 1835 Deutsche Mythologie, Jacob

Grimm (yes, that guy, of the Brothers Grimm and folktales galore) states

"The Easter Hare is unintelligible to me, but probably the hare was the

sacred animal of Ostara." This proposed association was repeated by other

authors including Charles Isaac Elton and Charles J Billson. In 1961 Christina

Hole wrote, "The hare was the sacred beast of Eastre (or Eostre), a Saxon

goddess of Spring and of the dawn." The belief that Ēostre had a hare

companion who became the Easter Bunny was popularized when it was presented as

fact in the BBC documentary “Shadow of the Hare” (1993, which seems a little

late in the game). But the Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore says

"... there is no shred of evidence" that hares were sacred to

Ēostre, noting that Bede does not associate her with any animal.

So

how did eggs get associated with the Eostre bunny? An old Teutonic myth says

that one Winter day the goddess Eostre was passing through a forest and found a

bird dying in snow from hunger and cold. The goddess turned the bird into a

rabbit because they have a warm fur and can find food more easily than any

bird. And so our bunny survived the winter and when the spring came, the animal

started laying eggs because it was once a bird. The rabbit then decorated every

egg leaving them to Eostre as a sign of gratitude. Hence the Easter egg hunt –

“the bunny left the eggs the night before” (wink, wink).

Rabbits

in Culture and Literature, Folklore and Myth

Rabbits are

often used as a symbol of fertility or rebirth, and have long been associated

with spring and Easter as the Easter Bunny. The species' role as an animal of

prey also makes it a symbol of innocence, another Easter connotation. They

appear in folklore and modern children's stories, often but not invariably as

sympathetic characters. Additionally, rabbits are often used as symbols of

playful sexuality, which also relates to the human perception of innocence, as

well as its reputation as a prolific breeder. The rabbit often appears in

folklore as the trickster archetype, who uses his cunning to outwit his

enemies.

◆ A rabbit's foot carried as an amulet believed to bring

good luck is found in many parts of the world, and with the earliest use being

in Europe around 600 B.C.

◆ In Aztec mythology, a pantheon of four hundred rabbit gods

known as Centzon Totochtin, led by Ometotchtli or Two Rabbit, represented

fertility, parties, and drunkenness.

◆ In Central Africa, the common hare (Kalulu), is

"inevitably described" as a trickster figure.

◆ In Chinese folklore, rabbits accompany Chang'e on the

Moon. Also associated with the Chinese New Year (or Lunar New Year), rabbits

are one of the twelve celestial animals in the Chinese Zodiac for the Chinese

calendar.

◆ A Vietnamese mythological story portrays the rabbit of

innocence and youthfulness. The Gods of the myth are shown to be hunting and

killing rabbits to show off their power. The Vietnamese lunar new year replaced

the rabbit with a cat in their calendar, as rabbits did not inhabit Vietnam.

◆ In Japanese tradition, rabbits live on the Moon where they

make mochi, the popular snack of mashed sticky rice. This comes from

interpreting the pattern of dark patches on the moon as a rabbit standing on

tiptoes on the left pounding on an usu, a Japanese mortar.

◆ In Korean mythology, as in Japanese, rabbits live on the

moon making rice cakes (teok in Korean).

◆ In Jewish folklore, rabbits (shfanim

שפנים) are associated with cowardice, a usage

still current in contemporary Israeli spoken Hebrew (similar to English

colloquial use of "chicken" to denote cowardice).

◆ In Anishinaabe traditional beliefs, held by the Ojibwe and

some other Native American peoples, Nanabozho, or Great Rabbit, is an important

deity related to the creation of the world.

◆ Among English speakers, the rabbit may be invoked at the

start of the month out of apotropaic or talismanic superstition.

On

the Isle of Portland in Dorset, England, the rabbit is said to be unlucky and

speaking its name can cause upset with older residents. This is thought to date

back to early times in the quarrying industry, where piles of extracted stone

not fit for sale were built into tall rough walls (to save space) directly

behind the working quarry face; the rabbit's natural tendency to burrow would

weaken these "walls" and cause collapse, often resulting in injuries

or even death.

The

word “rabbit” is often replaced with words such as “long ears” or “underground

mutton,” so as not to have to say the actual word and bring bad luck to

oneself. It is said that a public house (on the island) can be cleared of

people by calling out the word “rabbit,” and while this was very true in the

past, it has gradually become more fable than fact over the past 50 years.

Just

before that—about 62 years ago—I invented Harvey the Rabbit.

WELL, NOT

EXACTLY. Harvey the rabbit was the invention of Mary Coyle Chase, and for her,

the rabbit was lower case, and her Harvey, like mine, did not make mochi on the

moon or burrow under stone walls. He was something of an innocent rather than a

trickster, and although he was not himself a drunk, he associated with one.

Born

in 1906, Chase became a newspaper woman on the Rocky Mountain News in

Denver during the roaring twenties while she was still a teenager. In those

halcyon days of journalistic yore, reporters lived up to (because they created)

the stereotypical reputation of working long hours, drinking hard, and stopping

at nothing to beat the competition to a story. Running around Denver with

photographer Harry Rhoads in a Model T Ford, Chase recalled, "In the

course of a day, Harry and I might begin at the Police Court, go to a murder

trial at the West Side Court, cover a party in the evening at Mrs. Crawford

Hill's mansion, and rush to a shooting at 11pm."

Writing

under her maiden name, Mary Coyle, she started on the society pages of the News, but soon became a feature writer, reporting the news from a sob sister,

emotional angle, becoming part of the news itself as a comic figure, "our

Lil' Mary." She was also engaged in producing a cartoon feature, funny,

flapper era pieces as part of a series of "Charlie & Mary"

stories, for which Charlie Wunder drew the cartoons and Mary wrote the text.

In

1928, she married Robert L. Chase, a fellow reporter at the News. Bob

was a seasoned, "hard news" reporter, having worked at the Denver

Express since 1922, covering the robbery of the U.S. Mint and fighting

against the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Colorado state and local politics. The Express eventually merged with the News, and Bob went on to a 47-year newspaper

career at the paper, becoming managing editor and then associate editor.

Mary

Chase’s passion, however, was the theater, and in 1930, she left the News after six years and began writing plays. Her fourth play was “Harvey,” whose

title character was a six-foot tall invisible white rabbit, who accompanied a

kindly dipsomaniac named Elwood P. Dowd wherever he went. Dowd, thoughtfully,

always carried Harvey’s hat and overcoat, flung over his arm.

Elwood

was a gentle, philosophical soul. “My mother,” he was wont to remember, “used

to say to me, ‘In this world, Elwood’—she always called me Elwood—she’d say, ‘In

this world, Elwood, you must be oh, so smart or oh, so pleasant.’ For years, I

was smart. I recommend pleasant. You may quote me.”

Elwood

may have been inspired by another Denver newspaperman, the somewhat eccentric

but talented, erudite and principled Lee Casey, who was a star reporter,

long-time columnist and even acting editor (for a couple of years) at the News. His obituary in 1951 when he died at 60, included this encomium:

“Whether

turning out hard-hitting—and courageously against the grain of the

times—columns defending the rights of Japanese Americans during World War II or

a 13-year-old Wyoming boy railroaded by the justice system, he wrote with a

power and direct simplicity that stemmed from a clear sense of right and wrong.

At the same time, he was an avid reader who could deliver beautiful pieces on

classical literature.”

He

was a regular at the Denver Press Club poker games and “couldn’t leave his

beloved job, or his beloved newspaper, behind, even after his death. His ashes

were interred in the marblework of the paper’s lobby in the building at 400 W.

Colfax Avenue. They were subsequently removed to Olinger Crown Hill Mortuary

and Cemetery when the News moved east to 101 W. Colfax in 2006.”

Chase’s

Elwood, however, was not a newspaperman. He was, as nearly as anyone can tell,

not employed. Except as a habitue of Charlie’s, a downtown saloon to which he

was apt at any moment to invite whomever he had just met to repair for a drink.

In these expeditions, Elwood was accompanied always by his imaginary friend

Harvey. Elwood explains:

“Harvey

and I sit in the bars and we have a drink or two and play the jukebox. Soon the

faces of the other people turn toward mine and smile. They are saying, ‘We

don’t know your name, Mister, but you’re a lovely fellow.’ Harvey and I warm

ourselves in all these golden moments. We have entered as strangers—soon we

have friends. They come over. They sit with us. They drink with us. They talk

to us.They tell about the big terrible things they have done. The big wonderful

things they will do. Their hopes, their regrets, their loves,

their hates. All very large because nobody ever brings anything small into a

bar. Then I introduce them to Harvey. And he is bigger and grander than

anything they offer me. When they leave, they leave impressed. The same people

seldom come back—but that’s envy. There’s a little bit of envy in the best of

us—too bad, isn’t it?”

Rumor

to the contrary notwithstanding, Chase’s Harvey is not, strictly speaking, a

rabbit. He’s a pooka. One of Chase’s characters looks up the definition:

“Pooka, from old Celtic mythology. A fairy spirit in animal form. Always very

large. The pooka appears here and there, now and then, to this one and that one

at his own caprice. A wise but mischievous creature. Very fond of rum-pots,

crack-pots ...”

The

plot of Chase’s play is simplicity itself. Elwood’s sister Veta, a somewhat

scatter-brained middle-aged woman, has wearied of living with her brother and

his imaginary friend, an eccentricity, she believes, that interferes with her

social life and that of her daughter, Myrtle Mae.

“With

that rabbit in the house, our friends never come to see us,” Veta complains.

“We have no social life. We have no life at all.”

She

decides to have Elwood committed to a rest home for the mentally infirm. She

takes Elwood to Chumley’s Rest, but an attendant misunderstands and thinks Veta

is the nutty one and takes her off for a nice warm bath.

The

mistaken identification is eventually resolved (Veta refers to the over-eager

attendant as a “white slaver” because of his behavior towards her and his white

coat—which she sees as the uniform of a white slaver), and Dr. Chumley offers

to inject Elwood with a serum that will cure him of his hallucination.

“You

won’t see this rabbit anymore,” Elwood is told. “You’ll see your

responsibilities, your duties...”

To

which Elwood responds: “I’m sure if you thought of it, Doctor, it must be a

very fine thing. And if I happen to run into anyone who needs it, I’ll be glad

to recommend it. For myself, I wouldn’t care for it.”

But

he soon agrees to the treatment because he always feels that Veta should have

everything she wants.

At

the last minute, however, she changes her mind because she can’t bear to alter

Elwood’s pleasant demeanor.

By

the end of the play, Elwood’s delusion has impinged upon the rest of the cast

to the extent that not only Veta but Dr. Chumley begin talking about Harvey as

if he were real and apparent to them.

Elwood

has won. As he has all along.

Earlier

in the play, one of Chumley’s assistants urges Elwood to face reality.

“Doctor,”

says Elwood, “I wrestled with reality for forty years, and I am happy to state

that I finally won out over it.”

In

the closing scene in the play, Elwood is by himself on stage, and the door of Chumley’s

office opens, seemingly by itself, and Elwood greets the invisible Harvey as he

(presumably) enters the reception area: “Where’ve you been? I’ve been looking

all over for you...”

They

walk out together.

And

we, like everyone else watching the proceedings, are convinced: Harvey is

there. Harvey is real.

COPYRIGHTED in

1943 as “The White Rabbit,” Chase’s play was copyrighted again as “Harvey” for

its opening on Broadway on November 1, 1944. It was a smash hit, running for

four and a half years, 1,775 performances, closing January 15, 1949. In the

history of Broadway productions (which stretches back to 1750 according to St.

Wikipedia), “Harvey” became the 35th longest-running show (musicals and plays);

if only plays are counted, the 6th longest-running play on Broadway, after

“Life With Father,” “Tobacco Road,” “Abie's Irish Rose,” “Deathtrap,” and

“Gemini.” A film version with James Stewart as Elwood debuted in 1950.

Frank

Fay, who originated the Elwood role, and Stewart were the most famous actors to

portray Elwood P. Dowd. Josephine Hull portrayed his increasingly concerned

(and socially obsessed) sister on Broadway originally, and won a Best

Supporting Actress Oscar in the film. Stewart was nominated for a Best Actor

Oscar but lost out to Jose Ferrer in the 1950 film version of "Cyrano de

Bergerac.”

In

1945, Chase won the Pulitzer Prize in Drama for “Harvey.” In a field dominated

by men, Chase was the 4th woman to win the award; from 1917 to 2013, only 14

women have won the Pulitzer in Drama.

All

of which would come to nothing here at Rancid Raves had I not seen the “Harvey”

movie with Jimmy Stewart while I was in high school. Before I left Denver for

Kansas City in 1959, I’d also seen Joe E. Brown play Elwood P. Dowd in a Denver

theater. And in Kansas City ten years later while I was teaching English in

high school, I took a class of my students to a special dress rehearsal of the

play at the Union Station Theater.

The

Theater offered free tickets to high school classes to attend the dress

rehearsal performance because actors perform better when they have an audience.

I’d phoned in my request for a dozen tickets. When I went up to the ticket

booth to pick up the tickets, the lady at the counter asked under what name the

tickets were being held. I said, “Harvey,” and she said, “Oh, sure.”

I

and my students were the entire audience. It was theater-in-the-round, so we

were asked to spread out around the stage. We did.

During

the intermission, the actor playing Elwood came over and talked to me. He

wondered why they were getting laughs at places they didn’t expect to get

laughs. I explained that Harvey is my name and that my students laughed every

time they heard someone say my name on stage.

So

you might say I’ve had a long history with Harvey.

But

the Harvey the Rabbit that I invented came about in the fall of 1955 when I

started drawing cartoons for the campus humor magazine, The Flatiron, at

the University of Colorado in Boulder, where I was commencing my college

so-called career.

Those

were the days, my friends, when nights were filled with revelry and life was

but a song.

CAMPUS HUMOR

MAGAZINES were all the rage back when the twenties syncopated and colleges got

their reputations as habitats of licentious partying in bathtubs of gin. The

University of Colorado’s first humor magazine started in 1919 or 1920, as

nearly as I have been able to find out. Called The Dodo after an extinct

bird, it became extinct itself in about 1948 or 1949. But campus humor in

magazine form was revived a year later, christened The Flatiron, a much

better name.

The

magazine was named after a geological formation that cropped up in the

foothills at the edge of Boulder. Here is a visual aid. .jpg) The photo at the top is

of the actual flatiron geological oddity that makes a mountainous backdrop for

the U. of Colorado campus; there are five or six flatirons, depending upon how

you count/imagine. The picture at the bottom of this display is, as you

doubtless can tell, a joke. The photo at the top is

of the actual flatiron geological oddity that makes a mountainous backdrop for

the U. of Colorado campus; there are five or six flatirons, depending upon how

you count/imagine. The picture at the bottom of this display is, as you

doubtless can tell, a joke.

They’re

called "flatirons" because that's what they look like: for those who

are too young to remember flatirons, that's what my grandmother used to press

clothing with, a flat triangular slab of iron, heated over the stove or

fireplace. When not actually pressing clothing, the flatiron was stood up on

its end, the square bottom of the triangle, assuming a posture recalled by the

geological formation we've been contemplating.

The

next flatiron on view is the cover of the magazine with that name, the alleged

“humor” magazine at CU.  It was named after the geological formation but not because of any

kindred appearance; there is no resemblance. “Flatiron” was just a good word,

unique to the CU environs. This was the first I ever saw of The Flatiron magazine, the September 1955 issue. It was named after the geological formation but not because of any

kindred appearance; there is no resemblance. “Flatiron” was just a good word,

unique to the CU environs. This was the first I ever saw of The Flatiron magazine, the September 1955 issue.

I

picked up that September “Registration” issue while going through registration

that fall. To the best of my recollection, I had never heard of a college humor

magazine until then. I volunteered immediately to draw cartoons for it. The

editor, Jim Schaffner, might’ve been delighted: he’d just lost the “campus

cartoonist,” Annette Goodheart (“Netnet”), who’d graduated the previous spring.

Most

of the cartoons in the magazine were stolen from other campus humor magazines.

“Stolen” seems the most reliable source of cartoons in that “Registration”

issue. University humor magazines at the time were all part of a vast exchange

network, so everyone had access to everyone else’s magazine. And they borrowed

freely from each other. The quality of the drawing varied greatly—from raw

amateur to arty abstraction and, sometimes, surprising professional competence.

In

his editorial for this first issue of the school year, published in time to be

sold during registration that September, Schaffner wrote about the previous

year’s adventures:

“It

was a close one, but we made it. Last year’s ups and downs made us fear for the

life of The Flatiron. What with the banning, the Life magazine

publicity, the Tempest in the coffee-pot, and the threatened libel suits, we

thought there was a good chance that we would be put down for moral turpitude

(or inturpitude, whichever) or get called in front of the House somewhat

questionable activities committee. But, like we said, we made it. We are back

on the campus—no censorship, no troubles (yet), and nothing but the best in

campus humor.”

His

reference to “the Tempest” is to the disturbance caused by the visit to the

campus of Tempest Storm, a Denver stripper with a very large chest. As best I

can remember (and this incident happened before I was on campus so it’s all

hearsay here), a student photographer, Bob Latham—whose work often appeared in The

Flatiron—invited Tempest Storm to visit the campus (presumably for an

interview and a shoot, although neither, eventually, materialized), and she

walked across the quadrangle from Old Main to the University Memorial Center

(UMC)—the student union, which had just opened the year or so before.

It

was quite a long walk, and as she sashayed her way, she attracted considerable

attention from the male student population, which quickly turned into a

ravening mob, scrambling along in her wake. She entered the UMC through the

coffee shop, and the mob was so enthusiastic that the doors were torn off their

moorings as they passed through the portal. And that, in fact, was probably the

highlight—and the end—of the episode.

Other

references to the preceding year include an allusion to the banning of the

magazine. At the end of 1954, The Flatiron was banned on

campus—briefly—and then reinstated. The pre-banning issue was December 1954;

the resurrected issue, probably January or February 1955. There were three

issues that spring, a total of 6 issues for the school year.

Why

was it banned? Too much sex, probably. The editors no doubt felt they must

compete with Playboy, which had just—in December 1953—appeared; and the

editors were older guys with more experience at sex than most college students.

Judging from photos, the editors were probably ex-servicemen going to college

on the GI bill.

The

banning attracted national attention. Life magazine did a story on the

pin-up photos in The Flatiron’s first issues that school year—girls in

bikinis (or, in one case, reclining in front of a fireplace wearing a towel).

In one of the issues, there was also a short story recounting some sexual

activity between a man and a woman—lots of caressing and heavy breathing

reported. The publicity of Life’s coverage was doubtless enough to

convince the University’s Board of Regents to ban the magazine.

Why

it was reinstated—what allowed it to be reinstated so soon— is another

unanswered question. The culpable editor was fired and a new one installed. A

scapegoat having been sacrificed, The Flatiron was permitted to

re-emerge. The content of the reinstated magazine was not markedly different

except that there were no scantily-clad co-eds—except in the first issue’s

feature lampooning the Life coverage, which published again the

incriminating pin-up photos. As a joke, this time.

The

“House” committee Schaffner mentions is the nefarious House of Representatives’

Un-American Activities Committee, which had been skewering innocent passersby

for alleged subversive plots since 1938. During the McCarthy scandals of the

early 1950s, HUAC achieved a fresh notoriety.

Schaffner

had been associate editor under both 1954 editors and ascended to editorship in

the fall of 1955. He, like others of The Flatiron editors of the last

couple years, was older than the rest of us. I think he was probably a Korean

War vet going to college on the GI Bill.

I

don’t remember much about my relationship to the editor and his other minions.

To the best of my recollection, we never met in the magazine’s offices on the

fourth floor of the UMC. Some of what I drew, illustrations for short stories

or articles, was foisted off on me by the editor; but lots of the rest seems to

be concoctions of my own, probably propounded in the solitude of my dorm room

and turned in on spec.

One

issue, probably the second (and last) one I worked on, was assembled in the

basement of the Sig Ep (Sigma Phi Epsilon) fraternity house on Broadway. One of

Schaffner’s inner circle was a member there; Schaffner, as far as I know, was

not a member of any fraternity. We sat around a table to do our work. I can’t

remember if I drew cartoons right there, on the spot, or not. I suspect not,

but too many of the cartoons seem remnants of our so-called “editorial

deliberations” committed while we sat at the table, so maybe I drew some of

them right there.

As

far as I know, nothing ever happened in the office of The Flatiron. I

was in it only once or twice. I think the business staff might’ve operated out

of it, but the “creative” staff—mostly Schaffner—didn’t.

Schaffner

used to hawk Flatirons himself. As soon as an issue was published, he’d

take a chair out of the magazine’s office in the student union and put the

chair at the intersection of two busy sidewalks outside the building. He’d put

a stack of Flatirons on the chair, then, tucking a couple under one arm

and holding another in his outstretched hand, he’d croak: “Flatiron.

Getcher Flatiron here. Flatiron.” And on and on.

None

of the rest of us actually sold the magazine.

I DEBUTED in

the “Homecoming” issue of The Flatiron with the cover drawing posted

here, at the elbow of your eye.  I never drew another picture like it. I was clearly

attempting a cartoon style akin to that on display on the cover of the

“Registration” issue. I didn’t think I was good at this style, so I reverted to

my customary manner in all the other cartoons in my inaugural issue. I never drew another picture like it. I was clearly

attempting a cartoon style akin to that on display on the cover of the

“Registration” issue. I didn’t think I was good at this style, so I reverted to

my customary manner in all the other cartoons in my inaugural issue.

Drink

was evidently a big deal for Homecoming: alcohol consumption persuaded our cover

personality to abandon all of Shakespeare. It was an apt if mischievous

interpretation of that year’s Homecoming theme that quoted the title of one of

the Bard’s plays, “As You Like It.” And that’s how we were presumed to like

Homecoming—dead drunk after a joyously inebriated weekend.

Until

I arrived at CU, I hadn’t much familiarity with alcohol. (Nor Shakespeare.)

Despite the rambunctious nature of my high school class, I hadn’t so much as

sipped a beer. That and other manifestations of my adolescent innocence would

disappear fairly fast, as you’ll see as we plunge ahead.

Among

my first contributions to the “Homecoming” issue of The Flatiron were

illustrations for articles, one of which we see nearby.

I’ve reproduced the

“Highway Hanagover” illo twice, the second time focusing on the drawing. And if

you peer just below the highway sign at the lower right, you’ll see a tiny

bespectacled rabbit, drinking from a bottle. That is the first appearance of

Harvey the Rabbit. I remember drawing this picture at my desk in my dorm room.

I

was rooming with Bert Benedick, who was a couple years older than I. He was a

very cool guy before cool was something everyone wanted to be. Very laid back.

How laid back? Well, herewith, an example.

I’d

pledged a fraternity that fall, Theta Xi, and in due course, I graduated from

pledge to active during the customary “Hell Week” initiation. During that week,

all us pledges lived at the fraternity house, where we were induced to perform

distasteful tasks and suffer other humiliations. And we lost a lot of sleep.

Come Saturday, I was desperate for sleep, so I cut my Saturday morning class

and went to my dorm room for nap.

The

dorm rooms were narrow and uniform. As you entered, you passed closets, one on

each side, right and left. Behind sliding doors, each closet had, in addition

to clothes rack, a small waist-high cabinet. Next, you passed a dresser on each

side, right and left; then beds. Then two desks next to the window.

I

stretched out on the bed and promptly fell asleep. A few minutes later, I was

awakened by voices seemingly coming down the hall to my room. In a drowsy

stupor, I thought I heard the voices of some of my fraternity brothers, who

were doubtless patrolling the dorms to find runaway pledges like me sneaking a

nap.

I

jumped out of bed and, desperate for a place to hide if they came into the

room, I made for my closet and slid open the sliding door. Alas, it opened not

on the clothes rack section but on the little cabinet section. Nothing daunted,

I climbed on top of the cabinet and was trying to close the sliding door on

myself when the door to the room opened and Bert walked in.

He

said nothing in recognition of the peculiar sight he saw—me, whom he hadn’t

seen for a week, crouched atop the cabinet in my closet, trying to shut the

sliding door on myself.

He

just walked by, nodded hello, and went to his desk. I sheepishly climbed off my

perch and shut the sliding door.

That’s

how cool Bert was. Imperturbable. Absolutely.

Another

cool time—:

He

and I went drinking in Denver one evening with a couple friends. We went to the

Outrigger, a bar in the Cosmopolitan Hotel that was patterned after South

Pacific island village dwellings—all bamboo and thatch decor. Trader Vic’s took

over the motif in countless locations across the nation, but at the time, the

Outrigger was its own invention.

Once

we were seated at a table, the waitress came by for our orders, and she started

by asking for ID. Panic. I was underage. Bert was not. He gave her his ID, she

looked at it and returned it, then proceeded around the table. As she worked

her way around, Bert, seated across from me, slipped me his ID, so when she got

to me, I gave her Bert’s ID.

This

was tricky. When she’d first inspected his ID when he’d given it to her, she

returned it and said, “Thank you, Bert.” When she returned it to me, she said,

“Thank you, Benedick.”

Undoubtedly,

she knew.

But

the story illustrates Bert’s unflappable as well as resourceful personality.

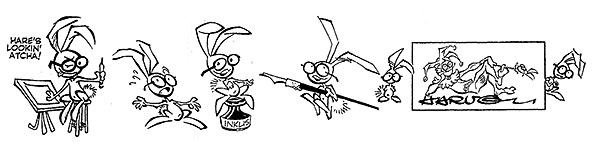

IT WAS BACK IN

OUR DORM ROOM at another time altogether that I’d first drawn Harvey the

Rabbit, deploying the tiny symbol as my “signature.” What had prompted me to

resort to a symbol instead of my name, I have no specific inkling.

Mary

Chase’s Harvey was clearly in my mind. And her play and the movie and the name

of the six-foot pooka were still high in public consciousness. So “Harvey the

Rabbit” was a phrase everyone was attuned to. Looking at a rabbit, you might

think “Harvey.”

That,

at least, was my strategy in adopting a rabbit with spectacles (because I wear

them) as my signature. But the steps in my thought processes arriving at this

device I cannot recall.

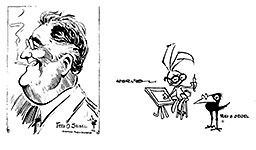

I

remember in the sixth grade being fascinated by Fred O. Seibel’s signature

crow. We were subjected to a current events newspaper called The Weekly

Reader (or some such), and most issues carried a political cartoon by

Seibel, who was the editorial cartoonist at the Richmond Times Dispatch,

and he signed his cartoons with a diminutive crow—“Jim Crow,” Seibel called it.

Later, once the civil rights movement began to move, he changed the crow’s name

to Moses.

Seibel’s

crow was probably in the back of my mind. But who knows for sure? Not me.

These

signature devices (technially termed “dingbats”) were often deployed by

editoonists. Perhaps the most famous is Pat Oliphant, whose dingbat is a

penguin named Punk. And you might be tempted to suppose my Rabbit was inspired

by Oliphant’s Punk. Not so. Oliphant, an Australian, worked at the Denver

Post, so proximity suggests that your supposition is logical. But

impossible: I had invented Cahoots in the fall of 1955, ten years before

Oliphant arrived at the Post in 1965. I met Oliphant years later, and on

the basis of my Rabbit, I persuaded him to draw Punk for me.

My

rabbit, whom I now call “Cahoots” (but that’s not his name: his name is still,

forever, Harvey, of course), did not appear on every cartoon I drew for the

“Homecoming” issue of The Flatiron that fall. I invented him halfway

through my labors for that issue. The issue’s cover, for instance, was drawn

after I’d happened on the Rabbit; so, he appears thereon.

While

he often appears as he does in that cover drawing—as a disembodied head—I tried

to use him at full diminutive figure in some way that commented on the action

of the cartoon he appeared in. And when I couldn’t think of anything for him to

do, I tried to hide him in some nearly conspicuous manner. Hereabouts are some

samples.

Among

them is another of my illustration assignments, a poem, “Sweet Ginny” by

someone called Metz. I don’t know where the poem came from or who Metz was/is.

Schaffner just handed me the poem, and I drew pictures of Sweet Ginny. And

stuck the Rabbit in amongst the crowd of her admirers.

At

last, among the accompanying examples, we get to the beating heart of the

exercise— drawing sexy babes, er, pretty girls. The excuse in one was

decorating a bookplate; the bookplate appeared amid several quarter-page ads

(genuine revenue-producing ads), and the supposition was that interested

parties could cut the bookplate out of the magazine and paste into their

textbooks. Probably my invention. But I certainly didn’t expect anyone to

actually scissor this overheated portrait out of the magazine. Bookplates were

not my chief preoccupation in doing this drawing. And in this Work of Art, the

influence of Mad’s Wally Wood is evident—legs and chest. In my

humble opinion, this is the best rendering of a pretty girl in this issue.

I

drew the cover and cartoons for the next issue of The Flatiron, too. It

was destined to be the last issue of the magazine. It was banned. Again. Beaten

to death by the Bored (as we said) of Publications, a faculty-student body.

Just as in that previous instance, it was banned presumably for its emphasis on

sex and alcohol. And I was carrying on in that nefarious tradition as you can

readily tell.

Because

of its scandalous history, The Flatiron was a lightning rod for criticism.

The reviewer on the campus newspaper, Roger Davidson, greeted this new Flatiron with this: “The nationally famed ‘folio of filth’ is filthier than ever as the

late lamented staff again has the notion that sex and humor are synonymous. ...

The failure of this Flatiron, as of all preceding issues, is the failure

of its staff to recognize and write real humor. The blatant fallacious

assumption that sex and humor are synonymous has merely been at the expense of

students who desire a good humor magazine on campus. We would advise students

to buy this issue, however, because it may be the last in a long time. Keep the

copies for a few years, and one may be able to get a good price from them as

relics!”

Prophetic,

as it turned out.

His

review of the previous issue—the one in which me and my Rabbit debuted—had

called it “clean as a bar of soap and fit to be displayed at a ladies’ aid

tea.” He might have added “and dull as dish water.” Roger had complimentary

things to say about some of the individual features of that issue, but in

summarizing, he wasn’t any happier over-all with this issue than he would be

with the next one. Said he: “One of the least objectionable issues in a long

time, it is also one of the least funny.”

He

also called “the work of rookie cartoonist Bob Harvey ... a bright spot in the

issue. Harvey’s evident mastery of the skill coupled with a wry sense of humor

contribute much to making the Flatiron almost worth a quarter.” Almost. And he

took notice of the Rabbit, which “distinguished” my work.

It

is the only time I can remember that my cartooning received a review. By name.

As

noted above, Roger did not mention either me or the Rabbit in condemning the

“Thanksgiving” issue as a “folio of filth.” (Roger, incidentally, eventually

married a cohort of mine, Nancy Davidson, whom you will meet in a trice.)

Others

on campus that fall of 1955 were less perturbed. One member of the student

governing body said: “I think it’s the best issue this year by a long shot.”

Another member of that august group agreed, sort of: “Even though it is a

little crude, this must be what the students want because it sold out.”

The Denver Post also slammed the “Thanksgiving” issue, calling it

“depressing” and adding:

“It’s

a sad effort and an utter waste of some nice, slik paper. The jokes (mostly

limericks and captions) are so hoary that grandpappy quit scribbling them on

the privy walls about the time he first went courtin’. Even so, they succeed,

along with Flatiron’s finger-painting caliber of art work, in being

stupidly gauche, even in misquotation or deliberate alteration. [The second

review of my cartooning but this time without naming names.]

“Nothing,”

the editorial went on, “is more pathetic than the adolescent trying to affect a

sophistication that is not yet his. That’s why The Flatiron, and its

sell-out, are both sad.”

The Post’s editorial went on to wonder whether the publication has not “put

the university itself in hazard” because it might inspire some kind of

disciplinary action. Probably should, in the Post’s estimation: “If this

is the literature, hardly of higher standard than the most berated comics, that

appeals to the taste of the C.U. student body, why is that student body itself

so tasteless?”

The

editorial finished by suggesting that Colorado taxpayers, once alerted to the

content of The Flatiron, may decide that their state-funded University

in fostering such a disgrace wasn’t worth their investment. “They may think

they are wasting their dough on a lot of young dolts who might better be

spending their time in army barracks and schools that train young ladies in how

properly to wait tables” instead of attempting to develop the youth of the

state into intelligent men and women ... citizens of more discrimination than

pool-hall loafers and hoodlums.”

After

that ejaculation, no wonder the magazine was banned. No public-funded

institution can long survive this kind of barrage.

At

the Colorado Daily on campus, reporter Duane Davidson wrote: “One of the

reasons for the abolition of The Flatiron was the embarrassment it had

caused the University recently, said Don Harlan, commission of publications. He

pointed out that embarrassing publicity of this type hampers the University’s

efforts in obtaining development funds.”

That

did it. The university’s reputation had been besmirched by its humor magazine.

And anytime you mention taxpayers in connection with a public university,

something happens.

In

the immediate aftermath of the Post editorial, members of the

university’s Board of Publications were non-committal in public. Maybe The

Flatiron would be banned; maybe not. But as soon as that body met, it

acted: it banned The Flatiron forever and ever, recommending that

“future Boards not approve the establishment of another magazine of this type.”

AT ONCE, THE

REDOUBTABLE EDITOR of that shameful rag, Jim Schaffner, philosophy major from

Highland Park, Illinois, responded. His reaction to Davidson’s criticism and to

the Post editorial was, in effect, to agree. But his agreement was a

rhetorical argument.

He

attended the Board of Publications meeting at which it was banned, and he

agreed with the Board’s decision. The “Thanksgiving” issue, he said, “stunk.”

“It

was a terrible issue,” he later explained. “I couldn’t put out a magazine that

would sell that I would be proud of.”

His

rhetoric implied a choice: publish an issue he could be proud of or an issue

that would sell. One or the other. Both were impossible.

He

pointed out that the “Homecoming” issue, a “clean” issue, sold only about 2,000

of its 3,500 press run. The “Thanksgiving” issue sold out. It was clearly “what

the students wanted.”

Soon

after the ban was announced, Schaffner let loose, continuing a long-running

feud with the university’s public relations guy, Jack Bartram.

“I

was charged with a responsibility that was impossible to discharge,” Schaffner

said. “I couldn’t please both Jack Bartram and the student body.”

Schaffner

charged that the magazine was banned as part of the University’s long-running

program of “education by public relations”:

“Bartram’s

job is to keep derogatory junk out of the Denver smut sheets so that the

legislature has a rosy view of things in Boulder.”

I’m

surprised, now—60-some years later—at how tough-minded Schaffner was. And how

out-spoken.

Of

the Post’s editorial that had probably precipitated the decision to ban

the magazine (the editorial was discussed at length at the Board meeting

although members of the Board said the editorial was not the reason The

Flatiron was banned), Schaffner said: “This University had great press

relations before Bartram was put to work as the moral FBI of the campus.

Obviously he alienates the press, provoking them to attacking the University.

It is easy to blame The Flatiron. It’s a patsy.

“We

suspect,” he went on, “that Bartram employed some mysterious coercion method to

the Board of Publications. There is no room for freedom of the press and

Bartram in the same place.”

Schaffner

had rubbed Bartram wrong the year before: “Last year I wrote a story blasting

Ward Darley [University President] for education by public relations. Soon

after I was brought to understand that this insidious trend at the University

is not Darley’s work. Darley is principled.”

Darley

issued a statement saying he had been “strongly in favor of banning The

Flatiron ever since the Thanksgiving issue came out.”

All

campus publications—the newspaper and the literary magazine, ept, enjoyed

freedom of the press. No faculty advisor sat in on editorial meetings to

approve or disapprove. In other words, no pre-publication censorship; but if a

publication produced something that earned the ire of the administration, it

could expect reprisals.

The

student governing body, the 13 commissioners of the Associated Students of the

University of Colorado (ASUC), backed the Board’s decision, but only after a

heated 3-hour debate over a resolution recommending that the University’s Board

of Regents review the banning decision and reinstate The Flatiron. The

resolution was introduced by Bill Hopkins, commissioner of entertainment and

the arts, who said his resolution was not intended as a defense of The

Flatiron but “a defense and a statement of our responsibility to defend the

rights and represent the wishes of the student body.”

He

questioned whether the Board of Publications had the right to ban a University

publication.

He

also pointed out that the magazine had sold out its “Thanksgiving” issue,

indicating that the content of that issue was what the student body wanted, and

it was therefore incumbent on ASUC, as elected representatives of the student

body, to recommend the magazine’s revival.

As

for the Board’s recommendation that it never approve in the future a magazine

of The Flatiron’s “type,” the commissioner of publications indicated

that a clarification would be issued. What was banned, he said, was The

Flatiron “as it is now. This does not mean that we can’t have a humor

magazine.”

Good

thing, too: as it eventuated, I was involved with two subsequent attempts to

revive a campus magazine. To gain approval, we steered clear of the word

“humor,” speaking only of a “general interest” magazine. But whatever we called

it, it would have cartoons—on the cover and within. But that’s a story for

another day (specifically, in Rants & Raves, Opus 366, later

this month; all part of our celebration at completing 18 years at this post).

Before we leave the premises, however, here’s a cartoon that appeared in the

first issue of the first revival. Clearly, The Flatiron was a long time

expiring. I’m surprised we got away with it. Good

thing, too: as it eventuated, I was involved with two subsequent attempts to

revive a campus magazine. To gain approval, we steered clear of the word

“humor,” speaking only of a “general interest” magazine. But whatever we called

it, it would have cartoons—on the cover and within. But that’s a story for

another day (specifically, in Rants & Raves, Opus 366, later

this month; all part of our celebration at completing 18 years at this post).

Before we leave the premises, however, here’s a cartoon that appeared in the

first issue of the first revival. Clearly, The Flatiron was a long time

expiring. I’m surprised we got away with it.

NO OFFICIAL

BODY (or unofficial one) claimed my cartoons were culpable. So I wasn’t to

blame for the banning. Not by name anyway. But I can’t help but think my cover

cartoon must’ve had something to do with it.  Not to mention others of my cartoons, two of

which are posted just a little further down this scroll. Thanks to the cover

drawing of the disrobing damsel, the cover oozes sex. But it’s a political

cartoon, not just a comedic one. Not to mention others of my cartoons, two of

which are posted just a little further down this scroll. Thanks to the cover

drawing of the disrobing damsel, the cover oozes sex. But it’s a political

cartoon, not just a comedic one.

The

ASUC had endorsed the idea of no curfew hours for senior women, an

unprecedented proposition. But sensible. Even in those distant days in which

educational institutions were severely in loco parentis, it was hard to justify

telling women who were 21 years old and older when they had to be in their dorm

rooms every night.

Once

the curfew for senior women was abandoned, senior women could stay out all

night if they wished. And it was assumed by all and sundry that senior women

would spent the night canoodling and sleeping around—the logical outcome if you

don’t make them come home at a decent hour at night. No hours = canoodling. The

cartoon visualizes the absurdity of this A=B equation, and, hopefully, by

visualizing it, ridicules it.

That,

in any case, is how I read it now.

Back

then, though, I bought the so-called logic of the equation: clearly, as anyone

looking at this cartoon could tell, if senior women had no curfew, they’d be

taking their clothes off and canoodling. The scales had fallen from my eyes,

and I saw, suddenly, the entire campus swarming with rutting students. Having

led an astonishingly innocent adolescence, I found this shocking. The cartoon

expressed my shock. And other cartoons in this, the “Thanksgiving” issue of The

Flatiron, did the same.

In

one of them— thankfully (for the “Thanksgiving” issue of The Flatiron)—

we get to a specimen that I think is funny. Well, the concept—a paperdoll

pin-up—is funny. And all the cut-out costumes actually fit over the “doll.” The

action progresses through the costumes, from the near nudity of the model to

the animated exaggerated lust of the guy at the lower left to the negligee of

the bedroom scene at the lower right—ending with my Rabbit (who has the

decency, alone among us, to blush).

It’s

easy to see why The Flatiron was banned as a result of this issue: the

Board of Publications was against sex. In common with most American adulthood,

they didn’t want us to know about sex. If we knew about it, we might (heaven

forfend!) do it. Meanwhile, I, coming from a small town at the western edge of

Denver (22 in my graduating class), was hearing more about sex than I’d heard

about before in my sheltered teenage life. It seemed to be everywhere. And so

it got into my cartoons, too.

I

marked the passing of The Flatiron with an editoon in the Colorado

Daily.

One

concluding note on the banning, and then I’ll abandon the subject forever. I

used to say, in jest, that while the banning oppressors of The Flatiron didn’t

say my cartoons contributed to the banning, it would be hard to deny that: of

the 32 pages of the magazine, 10 pages were ads, and of the remaining 22 pages,

17 were my cartoons. By the preponderance of the evidence, my cartoons

undeniably contributed to the downfall of The Flatiron.

But,

as usual, I was exaggerating.

The

“Homecoming” issue had 11 pages of advertising (counting full pages,

half-pages, and quarter pages); the “Thanksgiving” issue, 10 pages of ads.

In

the “Homecoming” issue—the “clean” issue— my cartoons (including the cover)

took 9 of the remaining 21 pages; in the “Thanksgiving” issue, the subsequently

banned issue, 7 1/4 of the remaining 22 pages. Of the editorial

(non-advertising pages), my cartoons were 42% of the “Homecoming” issue; 33% of

the banned “Thanksgiving” issue. By straight math, my cartoons contributed less

to the banned issue than they did to the preceding “clean” issue.

But

then, the Board of Publications wasn’t doing straight math. If it was doing

anything straight, it was straight crucifixion, and I’m sure my cartoons contributed

more than their numerical share to the provocation.

ONCE THE

FLATIRON WAS DEFUNCT, I was ostensibly out of business as a campus

cartoonist. But I found ways of soldiering on—drawing posters, for instance,

and doing Al Hirschfeld-like drawings about campus theatrical productions, and

covers for football programs and the season’s playing schedule, and other

events.

In

all of them, my Rabbit lurked. I seldom signed my name, but Cahoots was always

there. In one of the Homecoming football program covers, for 1956, the Rabbit

doesn’t appear, but the chubby waterboy is wearing a rabbit’s foot on his

keychain. Canny.

And

when I did the cover for the vest-pocket-size football schedule, I drew a

menacing buffalo football player charging along. The buffalo—the Golden

Buffalo—was the school mascot. No Rabbit in the drawing though: it would have

diminished the spectacle of the stampeding buffalo. I’d managed a nifty

anthropomorphization of the beast, I thought. And someone in the Athletic

Department apparently agreed: they used the drawing again the next year. After

that, it sank forever, never to surface again, leaving CU with only drab

silhouettes o personify the hump-backed mascot.

And

I drew a few cartoons for my fraternity’s magazine (and included the Rabbit). I

stopped after just a few because they were reproduced so small. Besides, I’d

found other ways to waste my time.

Chief

among them, writing columns for the Colorado Daily. The first was a

humor/gossip enterprise called Hare Today. And that led to my co-writing

the campus society/gossip column, Carousel, with Nancy Davidson. In

order to keep up on the latest social movements (which in those days, were

generally gauged by how high you raised your elbow), we tried to inspect as

many parties on Friday and Saturday nights as possible. For that purpose, I

invented an alter ego, Dunston Barswig, who wore a red-, white- and

blue-striped blazer as a disguise.

With

Dunston and the Rabbit on my record, it’s pretty clear that I was trying not to

be conspicuous because I was always hiding under another identity.

I

also ran for student government, the 13-person ASUC commission. But if you look

at the poster by which I promoted my candidacy, it’s pretty clear that the

Rabbit was running, not me. After all, he was better known than I. Because the

ballots were counted by an arcane method known as the Hare System, I didn’t

win. My fraternity brothers celebrated at lunch the next day, serandading me

with an a cappella rendition of a popular song of the day, “He was a big man

yesterday, but, ooooh, you oughta see him now.”

People

told me they enjoyed the Rabbit: one friend told me that looking for the Rabbit

in one of my cartoons was like watching for the Hitchcock appearance in one of

his movies.

The

Rabbit and I came out of supposed retirement a couple times after graduation

for class reunions (as celebrated among the cartoons posted above). For the 50th reunion, I had Cahoots looking in a hand-mirror and making a remark alluding to

mortality. The Rabbit made it to the final version, but his remark was excised

as being in bad taste. The people doing the excising were lots younger than me

and my classmates, who, due to increasing infirmities, were all more likely to

find humor in the Rabbit’s comment.

A

few months ago I ran across fragments of a memoir whose note about mortality I

jotted down and saved: "I’ve never felt quite this mortal. It’s a

beautiful word, ‘mortal,’ rhyming with ‘portal,’ which sounds optimistic. And

really, who wants to live forever? How tedious life would become. Mortality

makes everything matter, keeps life interesting. And that’s all I ask."

I gave

up the Rabbit when I started cartooning in the Navy; but that’s another story

for another time. (Briefly—Cahoots regarded the Navy as a fleeting thing and

wouldn’t commit to wearing a uniform for so meager a duration.)

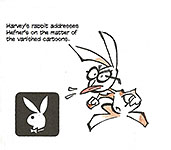

When

in 1978 I returned to gag cartooning for magazines, I abandoned Cahoots. I was

aiming to sell to all sorts of magazines—“general interest” on one hand, and,

on the other, “men’s” magazines. Among the latter, Playboy was the

highest payer. I always sent my cartoons to Playboy first; after being

rejected there (always), I sent them to the next highest-paying magazine, and

so on down a list of ever-diminishing monetary rewards until I finally reached Sex

to Sexty in Texas, which paid $5/cartoon.

I

didn’t have to be a rocket surgeon even in those pre-Sputnik days to suspect

that Playboy wouldn’t buy a cartoon signed with a rabbit: I would be

accused of trying to insinuate myself into the magazine by aping (or mocking?) Playboy’s institutional rabbit. If published, a rabbit-signed cartoon  would seem like

nepotism of some kind. Or incest. And if I tried to sell Rabbit-signed cartoons

to other magazines, all Playboy imitators, my submissions would

obviously make to headway at all. All of these alternatives strenuously implied

I shouldn’t sign my cartoons with my Rabbit. So I didn’t. would seem like

nepotism of some kind. Or incest. And if I tried to sell Rabbit-signed cartoons

to other magazines, all Playboy imitators, my submissions would

obviously make to headway at all. All of these alternatives strenuously implied

I shouldn’t sign my cartoons with my Rabbit. So I didn’t.

It

wasn’t until I launched this Website in 1999 that I again found employment for

Harvey the Rabbit as a sort of ethereal mascot. And then a couple years ago, I

found a special assignment for Cahoots, as you can see in our concluding

cartoon.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |