CELEBRATING A HALF CENTURY OF DOONESBURY

By Looking at the Beginnings of Trudeau’s Strip

G. B. Trudeau has been producing his comic strip Doonesbury for over 50 years. It passed the half-century milestone two years ago, but being inattentive for several months at that moment, we choose to celebrate this year, Doonesbury’s 52nd.

In addition to cartooning, Trudeau has worked in theater, film, and television. In 2013, Trudeau created, wrote and co-produced “Alpha House,” a political sitcom starring John Goodman that revolved around four Republican U.S. Senators who live together in a townhouse on Capitol Hill.

Trudeau also has been a contributing columnist for the New York Times op-ed page and later an essayist for Time magazine. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. He lives in New York City with his wife, one-time television star Jane Pauley. They have three grown children, two are twins.

Garretson Beekman Trudeau starting drawing Doonesbury while he was a student at Yale in the late-'60s. The strip evolved from an earlier effort, called Bull Tales, that “gently but piquantly satirized campus life” through the prism of a cast of college characters, primarily a football jock named B.D., who was based on Brian Dowling, the Yale— and later professional— gridiron hero.

Initially, Bull Tales appeared in The Yale Record, an irregularly published campus humor magazine (edited, for a time, by Trudeau). Then starting September 30, 1968, Bull Tales appeared in the campus newspaper, the Yale Daily News.

Bull Tales caught the eye of a newspaper entrepreneur who wanted to start a comics distribution outfit, a syndicate. The a-borning syndicate’s editor, James F. Andrews, convinced the 20-year-old Trudeau to sign on to a wholly unproven distribution operation. Andrews urged changing the name of the strip to Doonesbury and Universal Press Syndicate began with the launch of the strip on October 26, 1970, after Trudeau had graduated (with a master’s in art).

Trudeau

got the title of his new strip by combining the word "doone" (which

St. Wikipedia says would translate as "dweeb" today; but I question

that etymology) with the name of his roommate, Charles Pillsbury. It's also the

name of the strip's putative central character, Michael Doonesbury, who back

then was a nebbish who could never get a girl, and who now is a divorced dad

and head of an Internet start-up that has just had an IPO.

Universal has undergone a couple name changes since its debut, but the circulation of Doonesbury continued apace to more than 1,400 newspapers internationally, and the syndicate added to its roster of offerings with Ziggy (launched 1971), Kelly & Duke (1972), Tank McNamara (1974), Cathy (1976), and For Better or For Worse (1979).

In 1975, Trudeau became the first comic strip artist to win a Pulitzer, traditionally awarded to editorial cartoonists (who behaved badly on this occasion, complaining that Trudeau wasn’t a legitimate member of the club and wasn’t, therefore, deserving). Trudeau was also a Pulitzer finalist in 1990, 2004, and 2005. Other awards include the National Cartoonist Society Newspaper Comic Strip Award in 1994, and the ultimate NCS recognition, the Reuben Award in 1995.

Within a few years of its starting, Doonesbury’s popularity had established, as Trudeau was wont to say, the legitimacy of bad drawing for comic strips—hence Drabble, Dilbert and Cathy (to mention a few of the barely drawn strips).

Trudeau was influenced by Jules Feiffer, who had attracted a cult following with the weekly badly drawn cartoon he had been doing for The Village Voice since 1956. Drawing in a simple, scrawly style, Feiffer specialized in the angst of modern America. His cartoon is mostly talk. His characters are psychotic about talk. In agonizingly introspective monologues and dialogues, they explore their psychological or sexual anguish, invariably tripping over their own shortcomings as they unintentionally reveal their personality disorders and character flaws in the progress of their discourse.

Visual-verbal blending is minimal in Feiffer's cartoon: although the pictures sometimes underscore the irony of the characters' self-revelatory remarks, they mostly serve to pace the talk. Feiffer had a good ear for the way people talk, and in capturing their speech and pacing it, he gave his cartoon a unique rhythm, a cadence that led inexorably to a punchline of revelation.

Trudeau drew in Feiffer's sketchy fashion, even eschewing speech balloons by clustering his characters' verbiage near their heads like Feiffer did. But his college kids did not whine in endless self-analysis. Instead, they commented, directly or indirectly, on aspects of campus life. Trudeau's humor was not of the bemused non-sequitur sort; it was attack comedy, sharp and barbed. Trudeau was incisive and witty, his insights often powerfully satirical and always irreverent.

It was an age of collegiate irreverence. It was the age of protest— against the Vietnam War, against the establishment, against authority of all kinds. The temper of the times fostered among some young cartoonists a revolutionary counter-culture, and they expressed their disdain for mainstream America in producing "underground comix," comic books that championed the drug culture and assaulted conventional sexual mores with graphic gusto.

Trudeau was not so blatant as his underground compeers, but he was every bit as perceptive and angry. As a syndicated feature, Doonesbury continued Trudeau's satiric attack but extended his range of targets to include society at large as well as campus life. And when Richard Nixon committed Watergate, Trudeau had a field day. Pogo was still being published, but it was on its last legs; Walt Kelly was mortally ill, and Trudeau unceremoniously donned his mantle as the most pungent political satirist on the comics page.

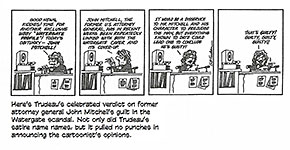

Unlike

Kelly, Trudeau used the real names of his targets. He didn't draw

pictures of Nixon, but he drew the White House and lettered outside its windows

speeches that only Nixon and his embattled aides could have uttered. In

one of the most famous strips of the period, Trudeau contrived for one of his

characters, radio personality Mark Slackmeyer, to pronounce John Mitchell

guilty on the air while at the same time pretending to allow the former U.S.

Attorney General the presumption of innocence.

For a long time, I was not much impressed by Trudeau's work. It was his drawing ability, or lack thereof, that turned me off. Yes, I am one of those art lovers who is distressed by ugly, amateurish artwork. In Trudeau's case, I was put off mostly by his habitually static visuals: panel after panel, the pictures stay the same while the political commentary drones on. Dull.

In a medium in which the visual and the verbal should blend, neither making complete sense without the other, it seemed to me that Trudeau's visuals did little more than establish the setting and identify the speakers. Scarcely high art.

But then I spent a weekend poring over The Doonesbury Chronicles, a reprint collection of strips from the feature's first four years, and the experience altered my opinion. While it is often true that once the setting is established by the opening panel, the sense of the words is largely independent of the pictures, there is a tension between word and picture that adds a layer of meaning to the strip.

Imagine a typical Trudeau sequence: a shot of the White House (repeated without alteration throughout the strip), or Michael Doonesbury watching TV motionlessly. To begin with, the unchanging pictures act to mute the impact of the words— the strip's only "action." Without much visual activity, the tone of the strip is rigorously restrained. And in those strips in which the last panel incorporates some minor visual change (Zonker looking helplessly out at the audience in frustration or Michael starting to smile), that change— however slight— gains greatly in dramatic import.

Since

the fourth panel alteration is the only thing "happening" in the

strip, it draws attention to itself way out of proportion to the intensity of

the "action" itself. Thus, a single fourth panel variation in

an otherwise repetitive series of panels becomes a powerful device for

Trudeau's editorializing. Under these circumstances, even a lifted

eyebrow can tell us how we are to interpret the verbal message:

ironically, seriously, mockingly, whatever.

A reverse effect is achieved in those strips in which the fourth panel presents no variation, in which all four panels are visually identical. In these strips, there is no editorial comment whatsoever. The verbal message is presented, and it has no effect, no impact, on the visuals. Nothing changes. Thus, there seems to be no relationship between the words and the pictures. And because we expect a relationship, its absence constitutes the message of the strip.

In such strips, the words may suggest some political or merchandising highjinx, some grossly self-serving enterprise. Because there seems to be no relationship between the words and the pictures, it is as if the strip is presenting us with two world views. The visuals portray "our" world; concrete details make it recognizable to us. The words suggest another world— the absurd extremity that results if we extend the logic of our politics or social customs or merchandising practices.

These worlds run parallel to each other, but neither seems to have any real effect upon the other. And that, in fact, is the existential message of the medium as practiced by Trudeau: the world we seem to create out of custom and mores has no bearing upon or relationship to the real world of concrete details in which we all dwell. The ideal to which our customs aspire has become absurdly out-of-touch.

Visually, the Doonesbury of this period was about as dull as it is possible for a comic strip to be. But to do as I had been doing (to look for a blending of word and picture in which the sense of each is dependent upon the other) was to fall short of grasping the whole meaning of Doonesbury.

Still the method does yield results— even if they are unexpected results. The words and the pictures in Doonesbury do work together. One comments on the other— while each retains an independent (albeit sometimes absurd) sense of its own. With this deployment of the resources of the medium, Trudeau has taken the art of the comic strip a step further. He has made the very nature of the medium— the relationship of word and picture— the vehicle of his humor and his comment. In a much more specific sense than in other strips, in Doonesbury the medium is message.

In daring, Trudeau is certainly Walt Kelly's equal. But he falls far short of Kelly's artistry. After all, despite the existential tension between word and picture in the static panel installments, Trudeau's strip is mostly a verbal exercise: it makes its satiric thrusts with words rather than by blending word and picture in fine-tuned concert. And the power of Doonesbury's humor is rooted in the strip's penchant for calling its political villains by their real names rather than by cloaking them in allegorical costume as was Kelly's practice. There's less art than audacity in Doonesbury.

Equally

audacious was the unprecedented 20-month sabbatical Trudeau took from January

1983 until September 1984, and when he returned, Doonesbury had a

slightly different look. Static panels were not trotted out as frequently

as before.  The artwork had a certain polish this time out, thanks in part to Don

Carlton, the artist who inked Trudeau's pencilled strips. Years earlier,

Trudeau had given up inking the strip; and in the 1980s, he faxed his pencilled

drawings to Kansas City, where Carlton created the inked version of the

strip. Together, Trudeau and Carlton sought greater visual variety in

every daily installment. They varied camera distance and angle and

spotted solid blacks dramatically.

The artwork had a certain polish this time out, thanks in part to Don

Carlton, the artist who inked Trudeau's pencilled strips. Years earlier,

Trudeau had given up inking the strip; and in the 1980s, he faxed his pencilled

drawings to Kansas City, where Carlton created the inked version of the

strip. Together, Trudeau and Carlton sought greater visual variety in

every daily installment. They varied camera distance and angle and

spotted solid blacks dramatically.

The appearance of the strip was much improved, but the existential message was forfeit. Too late. The previous years of static pictures had established the photocopied panel as a legitimate artistic mode. In graphic style as well as content, Trudeau had set a precedent that could not be recalled.

In celebrating five decades of Doonesbury, Andrews McMeel Publishing, an arm of Trudeau’s syndicate, produced one of the age’s modern miracles, Dbury @50: The Complete Digital Doonesbury.

The “book” is a box, and inside the box is a flash drive loaded with all 50 years of the strip, a searchable calendar archive, character bios, and a week-by-week description of the strip’s contents. Also in the box is a “user manual,” a 224-page book organized by year: every week’s developments are summarized with brief descriptive statements (“Zonker packs for med school”) for dailies and Sundays, preceded by a short essay that puts the week’s strips into their historical context (hence, revealing the satire) and includes sample panels from the week. A newly illustrated commemorative poster highlighting more than 50 prominent cast members completes this epic achievement.

The book’s text is supplied by David Stanford, who calls himself “duty officer”; but he could have more accurately described himself as a walking Doonesbury encyclopedia with highly perceptive vision and pleasingly glib verbal manner. His achievement herein is astonishing and commanding. And a pleasure to read.

Trudeau’s achievement is summarized by his syndicate’s Kathy Hilliard, who writes: “Trudeau’s ability to present such a wealth of insight and humor in the economy of a comic strip makes his accomplishments even more remarkable. Reviewed as a whole, Doonesbury@50 reveals an astonishing retrospective of characters, experiences, and significant signposts of the last 50 years —and enables us to appreciate the brilliance of the comic strip—and its creator—as a gift to readers for the past five decades.”