STEVE DITKO, STAN LEE AND THE CREATION OF SPIDER-MAN

And What That Tells Us About Their Creative Process

ONE OF THE THINGS that haunts the histories of Marvel is the question of who created Spider-Man, the character that would, many believe, surpass Superman as a best-selling comicbook superhero and thereby establish Marvel as DC’s most threatening rival on the newsstand. The contestants are Stan Lee and Steve Ditko.

The relationship between Lee and Ditko deteriorated over the years until, utterly exasperated, Ditko quit Marvel and went into hiding. But their co-creator bond was, apparently, always strained, even from the start.

At one point, however, the two were speaking to each other enough to produce a 3-page story about how they do Spider-Man. It appeared in Amazing Spider-Man Annual No.1 in 1964.

The tale is a remarkable spoof of the working alliance between Lee and Ditko. The pictures and speech balloons in the story are from Ditko’s point-of-view; the captions, from Lee’s, but it’s Ditko’s interpretation of Lee, not Lee’s. Taken all together, words and pictures, the story reveals just how disgruntled and resentful Ditko was about the conditions of his working situation.

|

|

Two years later, Ditko would stalk off the job without explanation. Perhaps this story is sufficient to that task.

The faux collaboration in this story, however, still leaves unexplained who created Spider-Man in the beginning. Both Ditko and Lee claim key roles in the creation even though the roles are interdependent. What with the testy relationship between the two, neither can be relied upon to reveal the actual facts of the matter.

STEVE DITKO HAS LONG ENJOYED the reputation as comics' J.D. Salinger, said Chris Arrant at robot6.comicbookresources.com, “—rarely releasing new work and eschewing the modern notion that creators should engage with fans and press. Stan Lee, he's not,” Arrant concludes with what I imagine must be a satirical sneer. Ditko, who had more to do with creating the Spider-Man character than Lee, quit Marvel ostensibly because he could no longer get along with Lee, who, Ditko realized, was claiming all the creative credit for the Marvel Universe. Since then, Ditko has maintained a stoic silence on his life and his career at Marvel.

But recently, Arrant reports, “Ditko has written several essays about Spider-Man in various independent publications. ... Earlier this year, Ditko published an essay called ‘The Knowers & The Barkers’ in his comic book #17: Seventeen, and a second essay just popped up in the comic fanzine The Comics Vol. 23 No.7, published by Robin Snyder, Ditko's former editor at Charlton and Archie. This second essay, ‘The Silent Sel-Deceivers,’ reportedly runs a page and a half and features Ditko addressing the creation of Spider-Man.

“In this essay,” Arrant continues, “Ditko discusses the original take on Spider-Man by Jack Kirby before Ditko was asked to come up with his own interpretation of Lee's idea for a spider-based hero. The Kirby pages, which Ditko says number five in total, have never been published or seen on the original art market. Lee, in a 2000 interview for Greg Theakston's The Steve Ditko Reader, said he rejected Kirby's work as ‘too heroic.’ On several occasions, Kirby later claimed he contributed many ideas that ended up in the character's formal debut in 1962's Amazing Fantasy No.15. Ditko talks about that in this essay, as well as Lee's own contributions to the Spider-Man concept.”

Ditko’s fugitive essays, which promise much, are often disappointing. I’ve read a smattering of these over the years in Snyder’s newsletter, and Ditko employs a high-fallutin’ vocabulary of abstract expressions and arcane buzz words that he often fails to fasten securely to the actualities he seems to be discussing—like what, exactly, was his contribution to the invention of Spider-Man. He garbles on about “art” and “creativity,” championing both and sometimes asserting, through a generous deployment of these terms, that he was the creative artist on Spider-Man. I don’t question that, but I always hope he’ll say as much in unequivocal, ordinary language, minus Ayn Randian locutions.

But each installment of Ditko's version of Marvel and Spider-Man history labors somewhat under the freight of the author's proselytizing fervor: nearly ever incident he relates and every argument he makes is tailored to a philosophical purpose. As a one-time fan of Ayn Rand myself, I am deeply sympathetic, and it is beyond question that to work for a corporate entity like Marvel is to submerge individuality in the conglomerate goo, a demeaning exercise for any creative personality but even more insulting if you are attempting, in your own life, to champion Randian self-centered pragmatism.

Much of Ditko's version of Spider-Man history has demonstrated, repeatedly, that the creative impulse at Marvel was continually bent to serve the demands of fans or corporate moguls— persons essentially outside the creative realm, who, for that reason, should have no say in the creative process.

In one issue, however, Ditko turns directly to the question that has animated the Stan Lee-Steve Ditko "dispute" for years: who, exactly, "created" Spider-Man?

DITKO'S CASE, which he argues better than he does many of his evangelical exercises, is that Spider-Man was "co-created" by him and Lee. Only "true believers" who are motivated by faith rather than evidence are likely, Ditko feels, to buy Lee's contention that Spider-Man was alone his, Lee's, creation because Lee was the one who had the idea of making a superhero with the powers of a spider.

Ditko visualized the idea, gave it physical presence, and is therefore entitled to be called "co-creator." As Ditko unfurls his argument, he manages to cast doubt upon even Lee's claim to having had the idea first.

"For me," Ditko writes, "the Spider-Man saga began when Stan called me into his office and told me I would be inking Jack Kirby's pencils on a new Marvel hero, Spider-Man. I still don't know whose idea was Spider-Man."

Ditko refers to Lee's interview some years ago on "Larry King Live" during which King reminded us of Lee's claim that he started thinking of a spider when he saw a fly on the wall.

"You know," Lee said, "I've been saying it so often, for all I know it might be true."

(Later in that interview, by the way, Lee insists that he was always assisted in the creation of Marvel heroes by the artists he worked with—a confession that didn’t distinguish his earliest comments on the matter.)

Ditko continues: "A leap from a fly to a spider is like from man to a cannibal. Stan never told me who came up with the idea for Spider-Man or for the Spider-Man story that Kirby was pencilling. Stan did tell me Spider-Man was a teenager who had a magic ring that transformed him into an adult hero — Spider-Man. I told Stan it sounded like Joe Simon's character, the Fly (1959), that Kirby had some hand in, for Archie Comics. Now here is a fly-spider connection. ... Stan called Kirby about the Fly; I don't know what was said in that call."

Later, the Kirby-pencilled pages were discarded—and so were the magic ring idea and the notion that Spider-Man would be an adult. Had the original plan been followed—if Ditko had said nothing about the Fly—what sort of Spider-Man might have emerged, Ditko asks.

"There would be lots of nots: Not my web-designed costume, not a full mask, no web-shooters, no spider-senses, no spider-like action, poses, fighting style and page breakdowns, etc." As far as I'm concerned, Ditko has made his case.

But Ditko’s version of how it happened is scarcely the whole story. Other parts of the story are related in Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story (488 6x9-inch pages, no pictures; Harper hardcover, $26.99; for the full review, see Opus 303).

A HISTORY THIS IS NOT. Howe’s book is anecdotal rather than documentary. At best, it is a book of gossip; at worst, it is inaccurate. All history is gossip so we can scarcely fault Howe for spreading lots of it in this book. But recognizing the book as more gossip than ascertainable fact is a good way to prepare for reading it. Despite this debatable shortcoming, The Untold Story received favorable reviews hither and yon, mostly because (a) Marvel is big in the entertainment biz; no longer merely a simple publisher of funnybooks, (b) many of those doing the reviews don’t know much about Marvel so this tome seems gloriously juicy with insight, and everyone dotes on gossip, the nastier the better.

Howe is not particularly nasty although he does manage to make Marvel into a sort of simmering stew of fights, feuds, squabbles, power plays and bad feelings fostered by a boss, Stan Lee, who appears increasingly more concerned with promoting himself rather than Marvel Comics. Several times (enough to be monotonous), Howe records the departure of a Marvel staffer by saying: “His feelings about Marvel would never fully recover.” Or words to that effect. Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Roy Thomas—in short, anyone important to the creative processes of making comic books eventually leaves Marvel with a bad taste in his/her mouth.

Howe’s sourcing is impressive, but however scholarly the apparatus, he is relying largely upon the testimony of writers and other factotums at Marvel and very little on artists. On the one hand, this practice is fruitful: writers, in particular, are articulate about their experiences and their views of what was transpiring at the “House of Ideas.”

On the other hand, writers, particularly those who create works of fiction, are, by nature, tempted to make things up—or to emphasize selected instances for dramatic effect. In short, since writers make their living by fabricating the best tales they can, isn’t it likely that they’ll deploy their talent during interviews about their, and Stan Lee’s, past? They’re not lying exactly, but they aren’t telling the whole truth either.

In the last analysis, Howe’s method is no different than any historian’s. He is forced to rely upon questionable witnesses. As are we all. So is all history but the sum and substance of gossip? Probably. And we are therefore well advised to remember that.

Lee is not a bad man in Howe’s estimation; but he seems oblivious to the effect on artists and writers of his decisions that advance the fortunes of Lee—and, to be fair, also of Marvel— at the expense of creative enterprise. Much of the narrative is a litany of people who were so slighted or put upon by Lee or by corporate preoccupations that they quit the company, leaving behind a crushed and bleeding spor of shattered dreams and broken promises.

In some ways, Howe shows, Lee was as much a victim as any of his cohorts. When Marvel began to be noticed for producing comic books about unusual superheroes, longjohn legions “with problems,” Lee, as the editor of the line, would be interviewed by newspaper reporters and very often his enthusiasms led his interviewer to believe that Lee was the sole creative personality at Marvel. This is an old story. Kirby created the Silver Surfer, Howe says; but Lee has always referred to the character as his creation, not Kirby’s. Ditto with Spider-Man and Ditko. Only in his last 15-20 years did Lee pointedly acknowledged that the creative machinations at Marvel included artists at his elbow.

THE RELATIONSHIP between plotter/writer and artist, between Lee and Ditko—and that between Lee and Jack Kirby—epitomizes the “Marvel Method” of creating comic books. Lee conjured up a plot and outlined it orally to an artist, and the artist then drew the story and then passed the pages of visual storytelling, first in pencil then in ink, back to Lee, who then created speeches and captions that knitted the pieces together. (Although sometimes, as gossip has it, Lee couldn’t remember the plot when confronted by the pages it inspired. He made do, though—larding the tale with witticisms and quips, thereby, almost incidently, creating the Marvel mystique, his singular contribution to Marvel Comics.)

The “Method” served the purpose for which it was devised: by sharing the storytelling load, Lee was able to produce great quantities of comic book stories that he could not have created had he tried to write complete scripts for the artists, the practice followed by DC and most other comic book publishers in the early days. But the “Method” also fostered the notion that Lee was the creative engine at Marvel; artists were secondary. The actuality, however, was quite the reverse. And the artists understandably resented being shoved off into a creative backwater.

Ironically, Lee would probably sympathize with them. He talked once about how the Method worked with Kirby. Lee would give Kirby a plot outline, often little more than an oral precis. Then Kirby, according to Lee, would "draw the entire strip [comic book story], breaking down the outline into exactly the right number of panels, replete with action and drama. Then it remained for me to take Jack's artwork and add the captions and dialogue."

Who, then, created the story? Lee could say he did: he invented the plot and added the necessary explanatory verbiage at the end of the process. Kirby could say he did: not only did he give the plot and the characters a visual reality, he (in Lee's words) provided the action and drama.

Neither man is lying or stretching the truth. Both men are entirely correct. (For more in this vein, see “The Making of the Marvel Universe,” in Harv’s Hindsight, July 2003.)

Their manner of producing comic books was quickly institutionalized. Lee adopted the same procedure when working with other artists who succeeded Kirby on some of the new titles that soon came pouring out of Marvel.

The so-called Marvel Method, whether by design or accident, had the virtue of putting the control of storytelling in the hands of the artists, who tended to tell stories pictorially rather than verbally. For comic book artists like Gil Kane, this approach was the only approach that made any sense.

"[The Marvel Method] is the best thing in terms of writing and drawing and effecting a balance," said Gil Kane. "Just like a writer and a director get together when they are going to do a [movie] and discuss it, the point of view and the approaches, and then begin a basic storyline. It's best now, to do it that way, to turn out an outline, give that outline to the artist after it's already been discussed. And the artist then dramatizes it. That's what the artist is: he's a dramatizer. If the writer is in effect a structurer, the artist is a dramatizer, a storyteller.”

Working in the Marvel Method, artists did more than give the characters facial expressions and their poses body language: they did narrative breakdowns and layout, thereby determining the pace of the story and the visual emphases—and with that, the essential action and drama of the stories.

And the artists doubtless did more than that. If they participated in the plotting session with Lee, they surely contributed bits and pieces to the plot as Lee unfolded it. They worked together. And then, after the artists turned their work in to Lee, he captioned the work and gave the characters their speeches, adding color and personality (and, sometimes, comedy) to the proceedings—particularly if he couldn’t remember the plot.

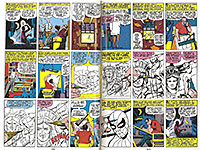

In the case of the creation of Spider-Man, we have even more telling testimony about how the character and the first story were created. The best revelation is not in the words or histories of either person, Lee or Ditko. Both are unreliable narrators. The best revelation is, rather, in the artwork of the first issue of Spider-Man.

ON A WEEKEND sojourn in Washington, D.C. for the convention of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists several years ago, I spent a couple of hours in the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress, looking at original art for the first Spider-Man story, which was donated by “an anonymous” person. (Ditko? And why should the donor be anonymous? More unanswered questions.)

Even if we didn’t have the authority of the 3-pager at the beginning of this essay, we can judge from the artwork evidence at hand that Ditko submitted his work to Lee first in its penciled state. In this inaugural two-part Spider-Man tale, Lee asked for three adjustments, two of which would have required re-drawing a panel or whiting-out visual elements. But the original art for the pages I contemplated featured no paste-overs and no white-out, which would have been visible if the adjustments had been made after the art had been inked. So Lee was looking at the penciled pages, which Ditko adjusted according to Lee’s directions when he inked. Or, as it happens, did not adjust.

Lee

made his suggestions in pencil in the margins. The notes have been erased but

they are still discernable. The first one occurs on page 3 of Part One. The

eighth panel shows a speeding automobile that almost runs over Peter Parker

because he is so absorbed in thought that he is oblivious to his surroundings.

The penciled art apparently included an arm protruding from the interior of the

car and out through a window, and that, Lee thought, implied that the car was

being driven recklessly, so he asked Ditko to remove the arm so as not to

suggest to young impressionable readers that reckless driving was acceptable.

And Ditko removed the arm, as we see in the accompanying illustration.

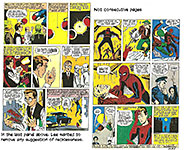

On the last page of Part Two (shown above), Lee’s comment focuses on the sixth panel. Here, he asks that Ditko “lift up” the second policeman’s head. In the original, apparently the second cop’s head is lower down in the panel—or perhaps just smaller. “Lifting it up” enhances its visibility, and Ditko complied with the suggestion.

But

the other comment Lee made, his third instruction, Ditko ignored. On page eight

of Part Two, Lee’s penciled comment is next to the third panel: “Steve, omit

crook! Show door slamming!” Ditko quite sensibly ignored this command.  He probably

ignored it because omitting the crook would remove the visual interest in the

panel: a vertical line indicating closed elevator doors is scarcely a dramatic

picture, and the scene demands some drama, coming, as it does, at the end of a

presumably heated pursuit.

He probably

ignored it because omitting the crook would remove the visual interest in the

panel: a vertical line indicating closed elevator doors is scarcely a dramatic

picture, and the scene demands some drama, coming, as it does, at the end of a

presumably heated pursuit.

Ditko may also have realized that the crook’s face, which establishes his identity at the end of the story (look again at the previous visual aid), needs a little more exposure than even the close-up of the next panel supplies. The figures of the crook in both second and third panels are small, but the heavy eyebrows provide a quick and certain means of identifying him. The profile in the fourth panel confirms in detail the distinctive eyebrows, but profiles, as a general rule, are not useful in identifying anyone except in profile; and the crook at the end of the story does not appear in profile.

Without page eight’s several exposures of the crook’s face, including the detailed profile, we might not be equipped to share Spider-Man’s moment of recognition at the end, and the story with its heart-rending moral lesson would be substantially spoiled. Ditko was right to ignore Lee’s dictum here.

Judging solely from these instances—perhaps the only “documentary evidence” we have—Lee, as editor and scripter, influenced how Ditko told the story that Lee plotted, but Ditko did the actual storytelling, enhancing its emotional highs and lows, and he didn’t always do what Lee wanted him to do pictorially.

Ditko is clearly the better storyteller; Lee’s advice is either off the mark or almost superfluous.

But both contributed to the finished story, each according to his ability and skills. And the artwork clearly shows us how. Spider-Man was obviously a collaborative creation.