AN INTERVIEW

WITH THE HAPPY HARV

Harv was

asked to respond to a series of questions. And here we go.

Why am I

a cartoonist? Did I start drawing seriously before I was a teenager? Was I

encouraged to draw by parents, teachers? Did I develop my art abilities in

school?

That’s enough

to start. And before we’re done, we’ll have more than enough. More than is good

for you. Whoever said “less is more” never came by my place. If less is more,

think about how much more more is? Onward.

My

father was an excellent artist. After he retired, he took up watercolor

renderings of mountain scenery (he lived in Denver at the time). But, more to

the point, when I was a youngster, he used to amuse me by copying my favorite

cartoon characters on 8 ½ x 11-inch sheets, which he would then frame for me to

hang on the walls of my room. I’m including a couple near here.

One

evening when I was about seven, I was reading a comic book, and, excited by

what I saw therein, I asked him to copy one of the characters that I liked. He

was too busy at the moment, I guess, because he responded by saying: “Why don’t

you draw it yourself?”

And

so I did. And I kept on copying other people’s comic characters relentlessly

for the next decade or so.

This

was my “apprentice period.” Like artists of the Medieval times, I was copying

the masters—albeit without their knowing it.

The

more I drew, as you might expect, the better I got at it. Eventually, I stopped

copying complete drawings and invented a few of my own, copying only parts of

the techniques of cartoonists—the way this guy drew ears, the way the other guy

drew hands, and so on. By the time I graduated from high school, all the

piece-meal copying had evolved into what sympathetic observers might have

called a “style” of my very own.

My

parents encouraged me in this endeavor, although never in the excited ambitious

manner of, say, the parents of a potential Olympic athlete. Friends of the

family who learned I was drawing a lot, asked me what I wanted to be, and I’d

say, “An artist.” It wasn’t until a few years later, that I learned the kind of

“artist” I aspired to being was a “cartoonist,” and then when I answered family

visitors’ questions, I would say, “A cartoonist.” And they would say, “Oh,

you’re going to work for Disney?” And I would agree. But I never did.

I

lived in Edgewater, Colorado, a small town, and the schools there were small.

My highschool graduating class had 22 people in it. At that dimension, the

school couldn’t afford an art instructor. No art classes.

I

remain, essentially, self-taught. Although when I was in the first or second

grade, I drew a nurse in military uniform, striding along. (World War II was

still going on.) The teacher taught us to begin a drawing with

shapes—essentially, tubular shapes for arms and legs, big oval for the body,

then put clothes on them. No stick-figure skeletons to start with; and to this

day, I can’t draw stick figures as a way of roughing up a drawing. I use

shapes. But that was about all the art instruction I ever had.

In

high school, the typing teacher was sponsor of the school newspaper, and when I

demonstrated some proficiency at typing, she made me editor of the paper. I

learned about journalism from a little handbook she gave me. In the University

of Colorado in Boulder, I minored in journalism and worked on all the campus

publications—daily newspaper, yearbook, magazines, the latter, a good outlet

for cartooning. At first.

By

the time I was a teenager, I had learned that not all cartoonists worked for

Disney. The most influential cartoonists I apprenticed myself to were Dick

Sebald and Gus Arriola.

Sebald

produced a weekly black-and-white cartoon for the Denver Post’s Sunday

magazine. Called Sage, Sand and Salt, it featured the comical adventures

of a small-time rancher (he had only one cow) named Bailin’Wire Bill. I copied

ol’ Bill for most of 1949 when I was twelve. I learned how to draw horses from

Sebald. As far as I know, his strip didn’t appear any place except in the Denver Post. And it only lasted a year or so.

But

by then, I’d discovered Arriola’s Gordo, also in the Denver Post—but

7 days a week. Arriola had just started modifying the way he drew, substituting

a bold outline and simplified anatomy for what had been almost realistic

rendering. For the first time in my apprenticeship, I didn’t copy the

characters: instead, I tried to copy Arriola’s new drawing style. You might be

able to discern my attempts in the accompanying drawing of two characters I

invented my senior year in high school—Dupin and Dooley (the chubby one).

I

worked up a comic strip presentation booklet, hoping to interest the campus

newspaper in publishing Dupin and Dooley. They hadn’t the money for

that sort of enterprise—making plates was too expensive, they said; but the

editor said he was surprised that an entering freshman like me had captured the

essence of college life.

At

the CU, I started drawing cartoons for the campus humor magazine as soon as I

arrived on campus; the magazine was banned after two issues with my cartoons in

them. They say there was no connection, but much of the magazine was my

cartoons. (The entire sordid tale of my college so-called cartooning career is

laboriously examined elsewhere in Harv’s Hindsight —“Easter and

Other Rabbits,” for May 2017—celebrating 18 years of this online magazine.)

Freelancing—how

did I do that, and how long did I submit cartoons before selling any.

I didn’t do any

“commercial” cartooning in college—that is, I wasn’t doing any of it for money,

more the fool me. But immediately upon graduation in 1959, I headed for New

York to try freelancing magazine cartoons by taking them around to cartoon

editors in person. I knew I would be drafted before long (in those antique

times, the draft still existed), so I was simply taking a parting shot (so to

speak) at marketing my cartoons.

With

another CU grad, I found an apartment—on West 82nd, just a block

from Riverside Drive with a subway stop at 79th. I worked four days a week: I

tried to come up with gag ideas and suitable drawings on Thursdays, Fridays,

Mondays and Tuesdays. Saturday and Sunday, I went sight seeing. Once I walked

from 42nd Street to South Ferry, seeing things I was never able to

find again—namely, a restaurant that had a Russell Patterson painting in the

lobby. On Wednesday, I traipsed around town to magazine offices with a batch of

10-12 cartoons. Wednesday was called “look day”: editors held open house all

day just to screen cartoon submissions, and in those days, lots of magazines

that used cartoons had offices in New York City.

Because

I knew that none of the editors had ever seen my work, I didn’t submit roughs,

then the accepted practice (still is); I did finished art in order to show them

what my final drawings looked like. After maybe a month of making the rounds, I

finally sold one—to DuGent magazines. The cartoon editor, assuming my

submission had been a rough, asked if my final drawing would look a lot like

it. It would, I said. And he bought the so-called “rough.”

It

was rumored that after making the rounds on Wednesdays, freelancing cartoonists

would convene for lunch at the Palm or the Pen and Pencil. That’s what I’d

heard. And they probably did, but although I undoubtedly sat across from more

than one freelance cartoonist in the waiting room of an editor’s office, I was

too shy to introduce myself. So I missed all the conviviality and drunken

carrying on.

Years

later, I was assured by one who was there that no drunken carrying on was

carried on at these famed Wednesday lunches: everyone still had more editors to

meet in the afternoon, and they preferred not to present their work while

stewed.

After

a couple months in New York, I returned to Denver and Boulder to pick up some

belongings I’d left behind. I spent a month selling some advertising cartoons

in Boulder.

Then I went to Kansas City

to spend Christmas with my folks. By that time, I’d enlisted in the Navy as the

only sure way to avoid the draft.

I

went for officers’ training at Newport, Rhode Island, where I began my career

as a Navy cartoonist, drawing cartoons for the “cruise book” (the yearbook). I

then went to Supply Corps School in Athens, Georgia, became editor of the

weekly base newspaper and drew a comic strip for it, starring Beau Sandy (his

name was derived from BuSandA, the nautical shorthand for Bureau of Supplies

and Accounts, for which we all worked).

I

spent the remaining three years of my enlistment aboard the aircraft carrier

Saratoga (CVA60), where I drew a comic strip for the ship’s monthly magazine.

It was called Cumshaw after its protagonist; “cumshaw” is a Navy term that

alludes to materials obtained in an unofficial manner (i.e., vaguely illegal,

at least without paperwork). It’s also a verb: to cumshaw something is to

obtain it without going through official channels. Perfect name for a sea-going

con-man, which is what my hero was/is.

When

I departed the Navy (it was only a fleeting thing, after all), I prepared

presentation books for two comical adventure strips: Fiddlefoot and Heroes

League.

The

presentation books consisted of pages displaying about 4-6 weeks of daily

strips. For the first few pages, I did finished art to prove I could draw. The

rest of the strips were roughs, albeit fairly finished; they were to prove I

could tell a story with a gag at the end of every installment. Both these

strips were continuities at a time when continuity strips were swiftly dying

out. Neither sold.

I

worked up three other strips ideas (Remuda about a cowboy, Rundle about

a con man, Hinshaw about a mailman), but none of them inspired me, so I

gave up on each one in turn. Each was devised as a gag-a-day strip, and I

didn’t feel comfortable without a story.

The

first two strips I tried to sell while I was in New York during the summer,

taking courses at New York University towards a master’s degree. I took the

presentation books around to syndicate offices, dropping them off one week and

returning the next to get the verdict.

The

visit to King Features was memorable. I was sent up the elevator to the fifth

floor. There, I was met in the elevator alcove by someone I assumed to be an

editor (but not The Cartoon Editor; just some bullpen flunky). He looked at my

presentation books, said they looked fine, but that King was not buying any

strips at the time.

“It’s

like this,” he explained, “we have so many strips out there in newspapers, that

if we come in to an editor and sell a new one, chances are, the paper will drop

another King strip to make room for it.”

This

probably made sense at the time. Now, I wonder why a newspaper couldn’t just

keep adding good, new strips to its lineup as long as good, new strips showed

up. Why the arbitrarily imposed limit? But then, I never pretended to

understand editors even though I’d been one several times in college.

Fiddlefoot

was my fondest creation. He had been lurking in my head all during my Navy

career. I doodled him constantly.

His adventures shadowed me wherever I went.

I loved him. When he didn’t sell, some of the steam went out of my desire to be

a comic strip cartoonist. Besides, I had to make a living, and I turned to

teaching in high school.

But

after earning a Ph.D. in 1978, I returned to cartooning—freelancing magazine

gag cartoons. This time, I did it all through the mail, in my spare time.

Because

thinking up gags was harder work than drawing pictures, I let gag writers do

the hard labor. Can’t remember how I acquired their names and addresses

(probably from one of the trade journals at the time—maybe Gag Recap), but I eventually had a half-dozen or so. They’d send me jokes on slips of

paper, and I’d keep the ones I liked. When one sold, I sent the gag writer 15%

of the take. Later, I upped their percentage to 25%, hoping I’d get better

gags—first choice in a lineup.

I’d

work up roughs during my lunch hour at work (I was fully employed then as a

convention manager). On weekends, I’d produced the final art, which I did in

what I still suspect is a unique manner.

Laying

a piece of tracing paper over a rough pencil sketch, I used a pencil again,

this time tracing the final lines onto the tracing paper. I “scrubbed” the

lines, producing a ragged-edge line. Then I photocopied this pencil tracing,

inking it instantly. I’d later add shading and solid blacks.

This

procedure was prompted partly by rumors that I’d heard about some magazine

editors “losing” (or keeping) cartoons. Or spilling coffee on them. Or

otherwise rendering the work I’d submit unusable when it was returned to me. If

such a thing were to happen to any of my cartoons, I could pull out the pencil

tracing and produce new final inked version nearly instantly. The rumors were

probably wrong: I never had occasion to resort to this maneuver. Once, in fact,

an editor wanted the original of an illustration I’d done for an article in his

magazine, and he asked me how much he should pay for it.

The

other reason I drew cartoons in this two-step manner was that it was forgiving:

if I made a mistake inking solid blacks or shading (the usual place for

mistakes), I could easily throw the mistake away and take up another

photocopied “inked” drawing to add blacks and shading to. And tracing the

pencil sketch in pencil precluded making any grievous errors.

To

this day, I produce most of my cartoons (not many: I prefer writing to drawing)

the same way, inking by photocopying. Now, however, I’ve abandoned the raggedy

line. I trace the rough using a fine-line gel pen. Then when I get the

photocopy, I fatten up the lines wherever I think a bolder line is needed.

After

I had about 20 cartoons, I’d package them up and send them off to magazine

cartoon editors. The package contained the cartoons and a stamped

self-addressed return envelop. The first mailing for a new batch went to the

highest paying magazine on my list; the second mailing to the next highest

paying, and so on down a list of steadily diminishing pay rates. I kept a log

book, showing where each batch had been—and which cartoons had been sold. Every

cartoon carried a different code.

At

first, I did a batch of “general interest” cartoons and sent them off to

magazines of “general interest,” starting with the National Enquirer,

then the second top-paying general interest publication; The New Yorker was

first (and still is). Then I did a batch for men’s magazines, tailoring the

’toons for that interest—plenty of barenekkidwimmin, in other words. The

cartoons that went to men’s magazines sold better than the general interest

cartoons. Obeying the unwritten rules of the market, I started producing more

batches for men’s magazines than for general interest magazines. I became a

“girlie cartoonist.”

|

Batch10.jpg) |

With

the girlies, I did pretty well, as I recall. I sold maybe 50% of a batch by the

time it had made the rounds. The last ones sold were being gobbled up at $5

each at a magazine published in Texas called Sex to Sexty. I tried

selling to the top markets— The New Yorker, Playboy, Penthouse, Hustler, etc. I sold one eventually to Penthouse, but I didn’t crack any of the

other top markets.

I

did best at DuGent, which published Dude, Gent, Cavalier and a

couple others. They paid about $25 at the time. My last year freelancing, I was

doing a comic strip for one of their magazines. Entitled Leda’s Ugly Duck,

it featured a swan and a naked wood nymph named Leda, all inspired by Greek

mythology (if you can believe that): Zeus had an affair with Leda which he

conducted in the form of a swan. It was a good gig. I’d rough out a story and

send the rough off to the editor. He’d approve it (never made any changes that

I can recall), and then I’d do the final art—again, inking by photocopying

(doing a couple panels of the strip at a time and then pasting them up in page

format). It started as a one-page feature and graduated to four pages.

In

short, doing the strip was a “sure sale.” And while I was doing it, I did no

other new batches of single panel cartoons. I was making more on the strip

every month ($300 as I recall) than I’d ever made in a month by selling gag

cartoons “on spec” (speculation). Then the bottom dropped out of my little

cartooning universe: DuGent stopped publishing the magazine that my strip was

running in. And the strip wasn’t considered suitable for any of the other

DuGent magazines.

By

then, I was spoiled: I’d become accustomed to my “sure sale” comic strip and

didn’t want to return to the “spec” scheme.

And

I’d started writing about cartooning for fan magazines like The Comics

Journal and the old and revered Rockets Blast Comic Collector (RBCC).

I enjoyed writing more than drawing, so I gave up on the latter. Journalism won

out over cartooning.

Some

say I’m a comics “historian.” But I prefer “chronicler” instead of “historian”

because I deal in contemporary comics as well as historical ones.

I

remembered when closing in on the end of the 18th year doing the

online magazine Rants & Raves that when I graduated from

Colorado University, I’d dreamed of editing and publishing a humor magazine.

And now, oddly—after 58 years spent dabbling at other endeavors—I’m doing

almost just that, albeit online and with very little revenue. And it’s not a

humor magazine, but it permits me to talk endlessly about cartooning. Which, as

you by now realize, I can, indeed, do endlessly.

Now

back to the questions.

How many

books have I written on cartooning and cartoonists?

Thirteen. I’ve

written nine and edited another four. Most of them are described and sold

hereabouts. A few are not; I’ll describe them here. I edited three volumes of Cartoons

of the Roaring Twenties; two were published by Fantagraphics before they

discovered how poorly the first two volumes were selling and stopped before

doing the third; it will doubtless never see print. I don’t carry these at my

website.

Three

of my books are now out-of-print. I did a biography of comic book artist Murphy

Anderson, published by TwoMorrows. I say I “edited” it. Its genesis is unusual,

I think. I interviewed Murphy over the phone several times, but when he said he

didn’t want the Comics Journal to publish it, I was stuck: the Comics

Journal was my major outlet.

Then

TwoMorrows popped up and wondered if I could do a book on Murphy. I had all

this taped interview material, so I said, Yes. Then I had all the interviews

transcribed and went through them, removing all the questions and leaving only

Murphy’s answers. I arranged the answers in chronological order and—presto: a

biography that was autobiographical was done.

Another

out-of-print book is Not Just Another Pretty Face: The Confessions and

Confections of a Girlie Cartoonist. Mostly, this one collects my cartoons

about barenekkidwimmin and accompanies the pictures with some essays of

explication. Lost Art Books, the flagship series from Picture This Press, is

planning to publish an expanded version of this title someday (after the #MeToo

ballyhoo has subsided and men resume looking at naked wimmin cartoons again). I

had fun designing the cover to look like the old Saturday Evening Post covers,

coupling a strait-laced momento to a salacious picture. Another

out-of-print book is Not Just Another Pretty Face: The Confessions and

Confections of a Girlie Cartoonist. Mostly, this one collects my cartoons

about barenekkidwimmin and accompanies the pictures with some essays of

explication. Lost Art Books, the flagship series from Picture This Press, is

planning to publish an expanded version of this title someday (after the #MeToo

ballyhoo has subsided and men resume looking at naked wimmin cartoons again). I

had fun designing the cover to look like the old Saturday Evening Post covers,

coupling a strait-laced momento to a salacious picture.

Another

out-of-print tome is The Genius of Winsor McCay, a short monograph about

his life and career.

Who is

the most interesting cartoonist I ever met? The funniest in person? The

quietest?

Will Eisner is

probably the most interesting—chiefly because his career is so varied. He

started in comic books (effectively inventing aspects of the form), continued

with instructional comics (which he virtually invented), and finished by

promoting and developing the graphic novel form. Perhaps the greatest of

cartooning’s pioneering masters, he remained engaged and interested throughout

his career, always looking for new ways to apply his cartooning skills and

knowledge.

Years

ago, I substituted for Eisner at some sort of cartoon conference at a

midwestern college: he was scheduled to appear but got sick at the last minute

and couldn’t make it, so I did a presentation about Eisner’s cartooning life

and career.

Playboy/New

Yorker cartoonist Eldon Dedini was fascinating. He was an artist’s

cartoonist: the picture interested him more than the caption. He regularly

clipped pictures he liked from a host of magazines he subscribed to. He pasted

the pictures into scrapbooks, sometimes adding his visual interpretation to the

page and jotting gag ideas next to the pictures/drawings. And when looking for

inspiration for a cartoon for Playboy or The New Yorker, he would

browse through the scrapbooks.

Sometimes

he’d draw the picture for a cartoon—in full color, destined for Playboy—and

then put it into a frame and prop it up in his study or his bedroom, waiting

for it to “tell him” the caption.

Milton

Caniff was also highly interesting. When he invited me to do his biography, it

enabled me to talk with him about every aspect of his career—something I would

never have had the nerve to do otherwise—and his career spanned the history of the

newspaper adventure comic strip, from beginning to end.

And

Gus Arriola was a dream come true. I’d imitated his drawing style when I was a

teenager, and to meet this master and get acquainted with him on a friendly

basis was all I could have hoped for.

None

of these guys were particularly funny. And I can’t remember any cartoonist I’ve

met who was funny in person. On paper, yes; but not in person. Cartoon comedy

is different than stand-up.

What the

heck is going on in cartooning today? Is the Internet good for cartooning? Or

is it cheapening the art form? Do we have any choice about using it or not?

The Internet is

clearly one of the futures of cartooning. But since there are no gatekeepers

(like feature syndicates or cartoon editors), the quality of the work is iffy.

Some excellent stuff is being done. Sinfest, a daily strip by Tatsuya

Ishida, has been regaling us with its quirky humor since January 2000. And

there are a few others. Mostly, however, web comics are pretty sad graphically

speaking, and the humor evades me more often than not. (More my problem than

theirs, no doubt.) Still, the web is a good place to train, and it’s lively in

that apprentice function.

Magazine

cartooning has been fading ever since the collapse of the Saturday Evening

Post as a weekly publication in 1963. Other great venues for gag

cartooning—Collier’s, Look, Saturday Review, etc.—joined the SEP at about the same time, late 1950s–1960s. And when Playboy stopped

publishing cartoons in March 2016, that left only The New Yorker as a

major market for gag cartooning. Other markets exist (consult Gag Recap website

to get a start at a list), but the pay is so low I doubt anyone can make a

living cartooning for magazines.

The

liveliest place for good cartooning these days is comic books. And it’s not

just superhero antics by overwrought anatomies in tighty whities. All sorts of

adventuring and joking is going on, and new titles on different life styles pop

up every month; some don’t last long, but other new endeavors take their places

quickly. The gratifying growth of the graphic novel has further stimulated the

medium in both art and story.

The

fate of newspaper comic strips is tied to the fate of newspapers, and while the

prospects don’t seem, offhand, very encouraging, the situation is better than

it seems. I have inveighed against the fake death of newspapers elsewhere on

other occasions, so I won’t repeat myself here. But there are a couple more

things I can add to that.

First,

new comic strips continue to be created. Not as many as in the fond days of

yesteryear, but new strips signal that there is some life left in the medium.

Second,

newspaper circulation, which has been declining alarmingly since the advent of

the Web, is reviving and doing better than supposed.

Oddly,

the election of the Trumpet has resulted in a surge of newspaper subscriptions.

In the week after the election, the New York Times netted 41,000 new

subscribers, according to a Huffington Post report; in the two days after

Election Day, the Times website got record traffic, and readers spent

five times longer on the site than they normally did. The Wall Street

Journal had similar experience: the day after Election Day, new subscribers

spiked with a 300% increase. By the end of the month, the Times had

132,000 more subscriptions in its print and digital editions. And the Washington

Post reported that it experienced a steady increase in subscriptions

through 2016; ditto the Los Angeles Times.

At

the end of last year, the Washington Post expected to hire more than 60

journalists this year. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos bought the Post in October

2013 and invested $50 million in the company last year—an investment, it turns

out, that’s paid off. At npr.com, Post’s publisher Fred Ryan said that

the paper is now “a profitable and growing company.” He said the Post’s online traffic has increased by nearly 50 percent in 2016 and new subscriptions

have grown by 75 percent, more than doubling digital subscription revenue.

By

the end of 2016, the New York Times had added 276,000 new paid digital

subscriptions, and digital advertising revenue rose almost 11% to $77.6 million

in 2016's last quarter.

The

phenomenon seems to be a direct result of the Trumpet’s casual regard for

facts. People subscribe to newspapers in print and digital in order to find out

what’s really going on—rather than believe, as an article of faith, whatever

the Trumpet says.

Termed

“the Trump bump,” the increase has enabled the New York Times to pass

the 3 million subscriptions threshold in the first three months of 2017. By the

end of March, saith thestreet.com, the Times will have “added 500,000

new net subscribers over a six-month period, unprecedented in U.S. history.”

The Washington Post is seeing “double digital subscription revenue in

the last 12 months, with a 75% increase in new subscribers.” Other large

regional papers report similar growth.

And

magazines are doing well, too. The New Yorker sold 250,000 new

subscriptions between Election Day and the end of January 2017, “up 230%

compared with the same three-month period a year ago. ... The magazine now has

its largest circulation ever, at more than a million.”

The

reported increases include paid subscriptions to both the publications’

Internet editions and to the print versions. Clearly, the daily newspaper is

not in its death throes just yet. And if newspapers are doing well, so will

comic strips.

Advertising

revenue is still the chief financial support of newspapers. Subscriptions never

produced enough revenue to do more than pay for printing. With the surge in

subscriptions, newspapers become more viable as advertising vehicles: more

people see the ads. But there’s more good news buried in this phenomenon.

As

subscriptions increase, newspapers become more dependent upon subscriptions—that

is, readers. Advertising is still important, but readership assumes a new

importance, and with that, newspapers must necessarily pay attention to what

readers want. And readers want comic strips.

Readership

surveys consistently show that comics rank among the top four in

popularity—front page, sports, obits and/or comics. So if newspapers wish to

maintain and/or increase subscriptions/readers, they’ll attend to the things

readers enjoy most. Comics.

This

line of reasoning is fraught with fallacious logic, no doubt; but I like the

conclusion, so I’m sticking with it.

Newspapers

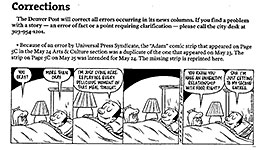

know the value of the comics to their bottom lines. They’ve always known. And

that knowledge has not faded. Recently, my hometown paper, the Denver Post,

provided a vivid demonstration of this prevailing wisdom. Through some

syndicate snafu, one of the installments of Adam @Home was missing for the

intended publication date, and the Post published the missing strip as

soon as it became available—on page 2 of the paper, not on the comics page. And

the Post explained why the strip appeared there. If that doesn’t

indicate a surviving priority, nothing does. Why make a big fuss over the event

if editors don’t know comics are important to readers? syndicate snafu, one of the installments of Adam @Home was missing for the

intended publication date, and the Post published the missing strip as

soon as it became available—on page 2 of the paper, not on the comics page. And

the Post explained why the strip appeared there. If that doesn’t

indicate a surviving priority, nothing does. Why make a big fuss over the event

if editors don’t know comics are important to readers?

Geez.

Did I really write all of this in response to a dozen questions? Well, yes,

obviously. But that’s what writers do: they write, relentlessly, endlessly.

I’m

glad someone asked. And I hope you are, too.

P.S. When

looking up another Harvey-centered Hindsight effort, I was astonished to realize how often

I’d written about myself and my cartooning career. Just to complete the

self-aggrandizement aspect of this entry, here’s a list of the other Harv

appearances in this department:

The Creation of

St. Jeff, February 2015; the mascot of “my” high school

Aged Interview,

January 2014; someone else asking the questions

It’s Not My

Fault, October 2012; how I got involved with cartooning history

The Story of

Zero, August 2012; my superhero comic and how it came to be

Fiddlefoot,

July 2012; ahhh, my fondest creation, a newspaper comic strip

Freelancing

Magazine Cartoons, February 2012; the ritual and how I did it

Critiquing the

Antique Happy Harv; February 2012; I examine and analyze my own cartoons

Return to Harv's Hindsights |