CARTOONS MAGAZINE

A Historic Periodical, 1912-1921

ENCOUNTERING A PUBLICATION NAMED CARTOONS MAGAZINE, you’d think it would be full of cartoons. And you’d be right. But the word “cartoons” in the early years of the 20th century did not include newspaper comic strips or comic books, the former just starting to emerge and the latter as yet unforeseen. “Cartoons” to this magazine’s founder, H.H. Windsor, meant editorial cartoons.

Cartoons

Magazine started as a

8.5x11-inch monthly magazine in January 1912, but within a couple years, it

reduced its page size to a more congenial 7x9.5 inches. Windsor, according to

David E.E. Sloan in his landmark American Humor Magazines and Comic

Periodicals (1987), was committed to the notion that the editoon was a

serious journalistic form. His magazine was jammed with editorial cartoons, but

not just editorial cartoons: the cartoons were surrounded by text, articles

that provided background and interpreted the events and social issues upon

which the cartoons commented. We’ve posted near here images of what the average

page in the magazine looked like.

Cartoons were grouped in thematic chapters with such titles as “The Railroads’ Toll of Death” or “The New Styles” or “Things That Never Happen” or “Rousing the Ire of Ireland” or “Bolshevism in America” or “Under the Big Dome” (politics in Washington, D.C.). Accompanying text elaborated upon those themes but without referring to any of the editoons.

Eugene Zimmerman, the great “Zim,” conducted a column called “Homespun Phoolosphy,” mostly humorous observations decorated by his drawings on such topics as “Wimin.” And Ralph Barton also wrote and illustrated a column under varying titles.

By the summer of 1917, the period covered by the bound volume I have in the Rancid Raves Book Grotto, most of the articles and the cartoons accompanying them were focused on the war raging in Europe, chapters thematically entitled “Giving Aid and Comfort to the Enemy” or “Berlin’s Political Pillow Fight” or “Getting On with the War” or “Hindenburg Still Lures Them On” or “Crucial Days in Russia.”

The war began in Europe in the summer of 1914, and Windsor took up the subject of war immediately. In his November issue that year, “The War in Cartoons Magazine” was on the cover, and inside articles dealt with the Napoleonic Wars in caricature and a wide coverage of war issues on the freshly opened hostilities in Europe. The first article was “The New Religion,” meaning “the worship of the gun”; it had the force of a Cartoons editorial. I doubt that we’ve moved much away from that religion.

From July through December 1917, the magazine covered the war even though the U.S. wouldn’t get into it until the next year. Congress had declared war on Germany April 6, 1917, but the American army was too tiny to go into war immediately. American troops didn’t get into battle until the summer of 1918, when they began arriving at the rate of 10,000/month.

But the U.S. was effectively in the conflict almost as soon as it had declared war. American supplies and armaments began reaching France and Britain in May 1917 just as those countries had exhausted their means of financing the war.

Although America’s greatest contribution to the war effort was in supplies and money, the arrival of American troops was an incalculable boost to British-French morale. The belligerent pen-and-ink efforts nearby are from the summer of 1917 in the magazine. The first two show a suitably angry and determined Uncle Sam; the other two focus on the war as seen by the belligerents.

|

|

In December, an editorial reprinted from another magazine commented that the cartoon has become “an established feature of modern journalism: [the cartoons] have humor in them, of course, but it is a grim, sardonic, bitter humor ... the bewildered surprise of those who are looking on the unbelievable.”

“Other features,” says Sloane, “dealt with Daumier and the Franco-Prussian War, America’s unreadiness for war, the national elections, and an array of war-related topics.”

The magazine’s periodical coverage of leading world and national social and political events often produced issues of 150 pages. T.C. O’Donnell became Windsor’s managing editor in the later teens. He edited an informal column, but he did not set as serious a tone as Windsor had at the outbreak of the war. “The Roaring Twenties,” observes Sloane, “may have proved hard on the serious side of the magazine.”

Windsor died in 1924, but by then he’d given up the magazine, and its content had shifted to lighter matters and its title and publisher had changed. The last issue of Windsor’s magazine is dated December 1921.

IN 1917, THE YEAR OF MY BOUND COLLECTION, Cartoons Magazine was publishing a series of "how to" pages from famous cartoonists. Nearby are a few, all by Billy DeBeck. He had yet to invent Barney Google (which he did July 17, 1919) and instead was doing editorial cartoons.

|

|

|

In

the next visual aid, cartoonists had fun drawing themselves in their cars, and

on the page at the right, Carl Ed (who would later create the Harold

Teen comic strip, starting May 4, 1919) pictures himself ("the

cartoonist") at the drawing board, arranging matters so that the face of

the culprit is obscured.  This was a practice often indulged by his cohorts. Evidently

they thought that if their faces were revealed, it would destroy the illusion

that the world they created with pen and ink was a world as real as the actual

world. It's as if the orchestra conductor were to turn around and face his

audience, the symphony would disappear. A pleasant delusion that we should be

delighted to allow them.

This was a practice often indulged by his cohorts. Evidently

they thought that if their faces were revealed, it would destroy the illusion

that the world they created with pen and ink was a world as real as the actual

world. It's as if the orchestra conductor were to turn around and face his

audience, the symphony would disappear. A pleasant delusion that we should be

delighted to allow them.

Other tooners, however, were happy to show their faces. Maybe even eager.

|

|

|

Although not entitled “how to,” the series The Cartoonists’ Confessional covered some of the same ground. Apparently, cartoonists were invited to contribute a page of sketches that depicted their boyhood ambition, their idea of a “pretty girl” (the precursor of “good girl art”), the easiest person to caricature, and so on. Except for Sidney Smith and Daniel Fitzpatrick, the cartoonists at work on this series are virtually unknown today.

Frank King, on the other hand, is still a highly visible name, and he shows up more than once in Cartoons Magazine. He was drawing a Sunday strip for the Chicago Tribune called Bobby Make-Believe and a page of themed panel cartoons called The Rectangle, which he’d been doing since sometime in 1913. It was among those panel cartoons that he introduced the feature that made him a household name among comics afficionados: Gasoline Alley debuted as a panel cartoon on November 24, 1918, a year after the Cartoons Magazine specimens we’re about to look at.

Nearby is a two-page King spread on how to hide yourself done expressly for Windsor’s magazine.

|

|

Hiding in a pile of coal is one of the ways—provided you have dark skin. In 1917, shamefully, the word "nigger" was in common parlance and not regarded as a slur among white commoners who resorted to it occasionally. In his cartoon, King is referencing an old expression, not

|

|

inventing a new one, but it still rubs us modern enlightened readers the wrong way. It is, however, a part of our history, albeit a shameful part, and we cannot make it go away by ignoring it. By not ignoring regrettable aspects of our history, we remind ourselves of our impurities, thereby taking a small step in the direction of not ever committing the same sins again. Or so it is hoped.

Two more King pages tell avid readers and aspiring cartoonists “how to be a cartoonist” which you can achieve, seemingly, if you know and deploy the visual tricks King illustrates.

TO GET A BETTER IDEA of how Cartoons Magazine worked, we can start with sample covers (usually in color) followed by the table of contents for a couple issues.

|

|

|

|

The list of the contents was usually topped by an elaborate humorous drawing of the sort we see here, a different drawing for every issue. One of the magazine’s regular departments was What the Cartoonists Are Doing, the decorative heading of which we reproduce below the sample contents pages; it offered short newsy bits rather than comprehensive reportage.

While most of the cartoons in the magazine were editorial cartoons, occasionally Windsor (or, more likely, O’Donnell) published single panel gag cartoons. And the subjects of the editoons were not exclusively the European war. “Old King Coal” (lovely word play) was dominating economic news as it has ever since, one way or another. That’s Woodrow Wilson struggling with Old Coal.

Advocates for prohibiting commerce in alcoholic beverages were becoming more and more vocal in 1917: they’d succeed in introducing the Eighteenth Amendment in December 1917; it became law in the Constitution after 36 states ratified it in January 1919, taking effect a year later. The law, incidently, did not prohibit the consuming of alcoholic beverages: one could drink all he wanted as long as he didn’t manufacture, import, transport or sell booze.

Cartoon comedy involving Kaiser Bill was prevalent in the magazine, but other topics, even such domestic events as “Life’s Little Jokes,” infiltrated as well as the occasional poignancy of cartoons like the one over the heading “The Wealth of the Nation.”

By 1917, Jay Norwood Darling, who signed his cartoons “Ding” (a contraction of his name, D’ing), had left his first home at the Des Moines Register in 1916 and was in New York, working for the New York Herald Tribune, his second sojourn in the Big Apple. (But he liked Iowa better and returned to the Register in 1919 and stayed there for the rest of his long career. He died in 1962 at the age of 85. The Herald Tribune continued to carry his cartoons until 1949, when Ding retired) Ding appears in Cartoons Magazine almost often enough to be counted a regular feature.

|

|

Another regular cartoonist is John C. Argens, whose decorative black-and-white renderings of fashionable personages elevated to Art the pages upon which they appeared. He worked in San Francisco, but Google doesn’t know his name; so we know no more about him.

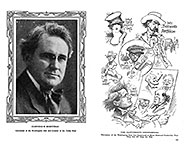

Nearly every issue carried a photo or two of a cartoonist in the What Cartoonists Are Doing department. Clifford Berryman also drew a self-portrait with a smattering of caricatures.

|

|

|

|

Ethel Plummer was among the mere half-dozen or fewer female cartoonists those days, and it’s doubtless in the nature of a self-deprecating feminist joke that for her portrait she donned the frilly garb of a female socialite. Her cartoon in one issue portrayed “Lions Among Ladies”—namely, the temperamental pianist, the interpretive dancer, and the Japanese poet, all of whom performed before women’s clubs.

Boardman Robinson, who did socially significant cartoons and illustrations, is here in “the only portrait of the artist which in his opinion does him justice,” a caption that sounds like his cartoons. And we also see what Paul Fung looks like. The “young Chinese cartoonist at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer” eventually outgrew that paper and took over the Dumb Dora syndicated comic strip when its originator, Chic Young, left to create Blondie, which started as another dumb flapper strip until Blondie married. Fung is often confused with his son, Paul Jr., who worked on Blondie comic books for 40 years.

Louis Raemaekers was a Dutch cartoonist who fled Europe as Germany began taking over. An interview with Raemaekers was excerpted in Cartoons Magazine, and I’ve lifted a couple paragraphs from it in which the cartoonist explains why he made his cartoons so “strong.”

Among my “finds” are two cartoons by Norman Anthony, a cartoonist who eventually became editor of the magazine Ballyhoo, the first humor magazine to include gag advertising in its pages. From that magazine, I knew he was a cartoonist but he never published any of his own work therein. And I have been unable to find sample of his cartooning until now.

|

|

Very realistic rendering.

By way of illustrating the range of Cartoons Magazine’s content, we have a political cartoon uncomplimentary about Woodrow Wilson by G. Brandt in Germany, a sample of Ralph Barton’s illustrations for his column, and a tender drawing of “Humanity” as a beautiful woman behind bars by Charles Henry “Bill” Sykes, whose caricatures of Kaiser Bill decorated the pages of Windsor’s magazine regularly making them virtually emblematic of Germany, as we’ve seen with other visual aids. Sykes’ use of grease crayon on grainy paper produced varying gray tones of “theatrical” effectiveness, as Richard Marschall put it.

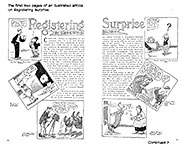

And we close this expedition by reprinting all six pages of Summerfield Baldwin’s faux erudite article discussing the use of symbols by which cartoonists register the surprise their characters experience.

|

|

|

Baldwin thought he was being serious, of course, but the extent to which he belabors the obvious qualifies the result as leaning in the direction of phoney rather than fact. Reminds me of me. This article is one of the very few that Cartoons Magazine published that is actually about cartoons.