|

THE UNFORGETTABLE JANE Who Seldom Blushed Regardless of Provocation

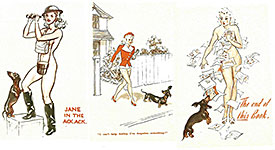

The British comic strip Jane was dubbed “the strip that teased,” and during World War II, the strip and its heroine, frequently flouncing through the panels in her frilly underthings, were the first thing soldiers turned to in London’s Daily Mirror, the newspaper for which Jane had been created. Jane teased but, according to legend, she never appeared naked—until a particularly significant day in 1944. Jane began cartoon life on December 5, 1932 in a feature entitled Jane’s Journal, subtitled “The Diary of a Bright Young Thing,” in which Jane and her pet dachshund Otto (also named Fritz) go about their daily business. Jane’s creator, Norman Pett, enjoyed showing off his character’s lithe figure but only insofar as an ordinary wardrobe displayed it; there was no outright nudity—although, given the clinging female fashions of the day, it was apparent that Jane was naked under her clothing. She was sometimes depicted in shorts while engaged in some athletic endeavor, but that was about the only time any leg was bared. At first. For several years. Mildly exciting but still pretty tame, in perfect tune with the depressed times. Then in 1938, Pett saw a petite young blonde woman modeling naked for an art class he was visiting, and he was smitten: “That’s Jane!” he is supposed to have exclaimed, and he hired her on the spot to model for him, chaperoned, always, by Pett’s wife, who had been the cartoonist’s first model for Jane. Pett’s new model, Chrystabel Drury (Chrystabel Leighton-Porter after marrying an RAF pilot), posed for Pett in the nude because that’s what female models did: that’s how they were able to assist artists to an understanding of female anatomy sufficient for depicting it even when it was fully clothed. The Jane Legend has it that every picture Pett drew of his oft dis-dressed heroine was drawn from life, from Chrystabel posing. About the time she arrived, Pett evidently decided that his strip needed a little more in the way of spice, and so he began depicting Jane either dressing or undressing, either way, in her scanties much of the time. When she wasn’t dressing or undressing, she was often experiencing some minor household disaster that resulted in an expanse of leg being exposed, usually up to the garter.

Pett also began working with a writer, Don Freeman, who assisted him in concocting situations that required pictures of Jane “scantily clad, clothes askew, skirts ripped and legs akimbo.” According to the Jane Legend, Pett and Freeman held story conferences in the pubs around Fleet Street, most frequently in the White Swan, where many of the cartoonists of the day imbibed—Lunt Roberts, Illingworth, Leo Dowd, Rowland Davies and Giles among them. Over flagons of stout, mild and bitter, or beakers of Scotch, the duo plotted Jane’s dis-dress. As Freeman later recalled: “We must have had the best jobs in Britain, Norman and I. Our whole purpose in life, our raison d’etre, was to think up ridiculous ways in which to get the clothes off a gorgeous woman; in fact, the woman who was probably desired by the majority of red-blooded males in the entire world! And, the best of it was that we were getting paid for it!” Jane increased in popularity as her clothing decreased its coverage, and publicity about the strip began mentioning Chrystabel, albeit without mentioning that she posed naked: nude modeling was so scandalous an avocation in those days that it was a carefully guarded secret in the Chrystabel-Jane newsstories that ensued. By the time War broke out at the end of the decade, Jane was the sweetheart of the British armed forces, many of whom believed that the comic strip character was based wholly upon a real person, so persuasive had the publicity about Chrystabel been. But Jane in the strip was still, comparatively speaking, somewhat circumspect in the display of her epidermis. According to the Jane Legend, she didn’t appear naked until the Allies invaded France, the celebrated day when “Jane Gives All,” as reported in Round-Up, an American serviceman’s newspaper. “After years of teasing and lingerie,” Paul Gravett reports in Great British Comics, “artist Norman Pett had finally caught his character in one panel in the altogether, drying herself with a towel the morning after June 6. That day was D-Day, when a great armed armada had swept across the Channel to take the Normandy beaches. What better way for Jane to congratulate the troops following that historic day and boost their morale further?” Jane’s “inspirational impact upon the British Tommy,” Gravett assures us, was no exaggeration. The Round-Up summed up: “Well, sirs, you can go home now. Right out of the blue and with no one even threatening her, Jane peeled a week ago. The British 36th Division immediately gained six miles, and the British attacked in the Arakan. Maybe we Americans ought to have Jane, too.” The Americans had Miss Lace, the central figure (so to speak) in Milton Caniff’s wartime strip for U.S. military newspapers, Male Call. Lace was enormously popular, but she never peeled. Jane, however, peeled plenty, and on several occasions before June 7, the ecstasies of the Jane Legend to the contrary notwithstanding.

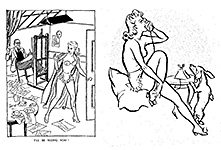

True, on D-Day + 1 she was unabashed and full-frontal bare naked, and neither she nor Pett did anything to shield her charms or to frame their revelation in terms of accidental dishabille. Unprecedented. But she’d been bared before in the strip. One enterprising British journalist, Margot Bennett, did an exhaustive inventory of Jane’s happy happenstances of near and absolute undress in 260 issues of the Daily Mirror: Jane, she reported, “shows her legs to a distance of at least nine inches above the knee 83 times. She dresses, undresses or is undressed forcibly to reveal the brassiere 14 times, the panties 13 times and both brassiere and pants 51 times. She is also shown full-length behind some inadequate substance such as steam, a nightgown, bathing costume or towel in 24 picture. She has her clothes blown off by a bomb in 4, takes a bath in 5, falls by parachute in 9 and sits up in bed in 5. She has a double who is shown twice bathing, 6 times in brassiere and pants. There is also a girl called Gladys, who is shown wholly in underwear 13 times and sectionally 3 times. This makes an astonishing total of 232 exposures, partial or complete, in 260 issues of the Daily Mirror.” So

popular was Jane that she was briefly exported to U.S. newspapers. There,

Gravett says, readers of “family-friendly funny pages would be far less

tolerant than their supposedly reserved British counterparts of daring glimpses

of nipples, breasts, bottoms, and states of undress,” and so Pett was persuaded

to doctor his artwork to remove such affronts to America’s Puritan sensibilities.

These adjustments, given Jane’s proclivity for shedding raiment, consumed vast reaches of time. As a result, Pett fell behind in meeting his British deadlines and Jane once dropped out of the paper for several days, inspiring a desperate outcry among the populace. Finally, she reappeared in a single panel composed for the occasion, naked but clutching a couple of curtains for the sake of modesty and saying: “In reply to all your many inquiries as to what has happened to me—Give me a break. I can’t find my panties!” Andy Saunders in his book Jane: A Pin-up at War (176 8x9-inch pages, b/w with lots of photos of Chrystabel; 2004 Pen & Sword hardcover) regales us with the inevitable sequel: “The effect was immediate, and literally quite overwhelming. If the staff at the Daily Mirror had been surprised by the response when Jane had initially been dropped, then nothing could have prepared them for what happened next. [The street in front of the newspaper office] was blocked with mail vans and delivery boys—all of them bringing hundreds upon hundreds of letters, most of them containing pairs of undies. The question, of course, was what to do with them?” The answer, during wartime, was comparatively simple, Saunders explained. His book, my source for much of what is transpiring here, is as much about the model who posed for cartoonist Pett as it is about the comic strip character. Always interested in the theater, Chrystabel had made a career being Jane’s alter ego: in addition to modeling for Pett, she appeared during the War in theatrical revues aimed at boosting soldiers’ morale. What with the wartime rationing of various kinds of fabrics, lacy feminine undergarments were in short supply. Chrystabel gathered up basket-loads of panties at the Daily Mirror office and distributed them to chorines-in-need at the revues where she worked.

Jane was easily the most famous British comic character in World War II, more celebrated, even, that political cartoonist David Low’s Colonel Blimp, a self-mocking blow-hard; see Blimp section below. But once the hostilities were over and the Tommys returned to the domesticity of home and hearth, Jane’s purpose in the world faded. Pett retired in 1948 to start another strip about a pretty young thing undressing, Susie; but lacking the fevered morale-building function of the wartime Jane, Susie foundered. Meanwhile, Jane was continued by Pett’s erstwhile assistant, Mike Hubbard, who prolonged it until October 10, 1959, when Jane finally married her beau, the patient Georgie, with whom she sailed off into the sunset—in a rowboat. Before long, the Page Three Girl invaded tabloid Britain, and female nudity from the navel up was all at once so amply displayed as to render Jane’s earlier antics nearly antiseptically quaint. Quaint but charming. And historic, very historic. A vast amount of Jane strips (plus some color pin-ups, a color adventure series and the fictional first meeting of Chrystabel and Pett in a three-page sequence, which we post nearby) have been reprinted in The Misadventures of Jane (160 8x10-inch pages, 2009 Titan Books, $19.95).

All of the Jane wartime strips from Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on September 3, 1939 through the unconditional surrender of Japan on August 14, 1945 have been reprinted in Jane at War (480 8x10-inch pages, b/w; 1976 Wolfe Publishing paperback).

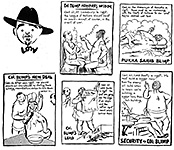

About Colonel Blimp: In the mid-1930s, Britain’s most celebrated editoonist, David Low, created this fatuous character in order to typify “the current disposition to mixed-up thinking, to having it both ways, to dogmatic doubleness, to paradox and plain self-contradiction. This sort of thing: ‘We need better relations between Capital and Labor. If the trades unions won’t accept our terms, crush ’em.’ Or, ‘What the country wants is more economy. Our fellows should fight Russia and China and damn the expense.’” Low had been allotted an entire page in the Saturday issue of his newspaper, and he created Colonel Blimp as a single-panel cartoon to help fill up the space. Recalling the final moments in the gestation of the character in his autobiography (entitled, with admirable exactitude, Low’s Autobiography), Low said he was in a Turkish bath, “ruminating on a name” for his character, when he happened to overhear a couple “pink sweating chaps of military bearing” talking nearby. “They were telling one another that what Japan did in the Pacific was no business of Britain.” At the same time, Low was thinking about an article in the newspaper that morning in which “some colonel or other had written to protest against the mechanization of cavalry, insisting that even if horses had to go, the uniform and trappings must remain inviolate and troops must continue to wear their spurs in the tanks.” This

was just the thing, Low realized: his character should be a military man,

puffed up with his own sense of importance and certitude. And so the Colonel

Blimp series began: Low put himself into the picture, so Colonel Blimp would

have someone to pontificate to, and the cartoonist put them both in a Turkish

bath “performing our ablutions or exercising, he uttering to me a blatantly

self-contradictory aphorism.” The series continued every Saturday until the end of the decade, when, due to the onset of war in 1939-40, a shortage of newsprint eliminated Low’s page. Thereafter, he concentrated on his purely political cartoon, but Colonel Blimp showed up occasionally, and the character eventually starred in a movie, “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp.” Some who saw the movie were scandalized, outraged because of “their simple belief that, in political or social fantasy, hateful ideas must always be represented by hateful characters,” so they thought Colonel Blimp was supposed to be hateful—even though he wasn’t. When the film arrived in the U.S., the character had assumed another dimension altogether in publicity materials. Apparently misapprehending the type that Blimp represented, American flacks depicted him as a near cousin of Esky, the leering roue mascot of Esquire magazine, bug-eyed in admiration of whatever female leg came into his field of vision. After World War II, Low retired Colonel Blimp: he had become too closely identified with the War to fit into the new age. For a review of a collection of Colonel Blimp cartoons and the full story of Blimp and Low, re-visit Rants & Raves, Opus 320 (January 30, 2014). |

|||||||||||||