WHY MANKOFF LEFT THE NEW YORKER

And What That Was Really About

So why, actually, did Bob Mankoff leave The New Yorker as cartoon editor after a couple decades on the job? Just got tired of it? Not of cartooning, not of editing—selecting—cartoons. Upon leaving The New Yorker, he immediately, the next day, joined the staff of Esquire as cartoon editor. So he didn’t leave The New Yorker because of job fatigue. Why then?

At the time of Mankoff’s departure at the end of April 2017, editor David Remnick did nothing but praise him:

“He has brought everyone’s best work to the table and managed a complicated balancing act with grace,” Remnick said of Mankoff in a staff note that also praised the outgoing editor’s careful buildup of a stable of fresh, diverse cartooning voices.

And Mankoff responded accordingly:

“What I absolutely take satisfaction in is that, as I leave as cartoon editor, I leave The New Yorker and my successor with a bumper crop of new and talented cartoonists who came in under my tenure,” Mankoff told the Washington Post’s Michael Cavna.

“To

name a few,” he went on, “—Liana Finck, Emily Flake, Drew Dernavich, Paul Noth,

Harry Bliss, Edward Steed,” Mankoff says, before wryly deciding to name more

than a few: “Alex Gregory, David Sipress, Joe Dator, Zachary Kanin, Farley

Katz, Pat Byrnes, Ben Schwartz, Tom Toro, Chris Weyant, Matt Diffee, Amy Hwang

— well, you get the idea.”

Mankoff also shepherded the daily presence of cartoons on the magazine’s website, growing its digital audience.

No evidence in that of why he left.

But then, two years later, Mankoff got pretty specific all of a sudden. The Esquire job had evaporated in a revamp of the magazine, which ultimately turned Esquire into nothing more than a men’s fashion magazine without cartoons or any noticeable sense of humor. It had started as a men’s fashion magazine when it was launched in October 1933. But it had cartoons then. (And cartoons—full-page cartoons in color—“undoubtedly accounted more than any other [factor] for the magazine’s sensational success” according to Arnold Gingrich, one of the magazine’s founders.)

In 2019 when introducing his online Cartoon Collections, Mankoff said this on November 18—:

“Hi, All— In another lifetime ago, actually just back in 2017, I was cartoon editor of The New Yorker. I really liked that job but not so much that I wanted to stay on, especially after I was asked to leave. I really had to go then or I would have been arrested.”

Mankoff could easily double as a stand-up comedian. Any time he stands up before a few people, the comedian quickly surfaces, and everyone else is promptly overshadowed. As they are here, as we’ve just seen. But he gets serious as he continues—:

“But why was I asked to leave? I like to think it was for appropriate behavior: selecting the cartoons that I thought were the best regardless of the identity of those who did them. I still think that’s the best way to increase diversity without sacrificing quality.

“Now this might sound like sour grapes, but it’s not, anyway not now, because leaving that great job has given me the opportunity to do something I could have never done while there. So those grapes are turning out to be quite sweet.”

The sweet grapes, Cartoon Collections, worked like Cartoon Bank (which he’d invented and then sold to The New Yorker twenty years ago on the condition that he be appointed the magazine’s cartoon editor). Cartoonists submit their rejected cartoons, hoping they’d be purchased through Cartoon Collections by businesses that wanted cartoons for their newsletters, brochures, or catalogues or by teachers for use in the classroom or by individuals as birthday cards or some such.

Most of the rejected cartoons were perfectly fine. They weren’t rejected because they were bad cartoons: they were rejected because there weren’t enough places for them to be published.

The market for single-panel cartoons had been shrinking for decades. The New Yorker is most of what remains; the big magazines that published cartoons died off (Saturday Evening Post, Saturday Review, Collier’s)—except, for a time, Playboy. Only a few of the smaller (lower-paying) magazines remained— Modern Maturity, Parade. And they published cartoons at the rate of only a couple every other issue. Something like that. The New Yorker published about 15 cartoons in an issue, and that was the biggest market. And cartoonists produced a lot more cartoons every month than The New Yorker could publish.

Mankoff also had on file in Cartoon Collections cartoons that had been published in all those steadily evaporating markets— Wall Street Journal, Wired, Barron’s, Weekly Humorist, Good Housekeeping—as well as vintage cartoons that had been published years ago in magazines that no longer existed.

Cartoon Collections was, he said, the Google of single-panel cartoons. If you were looking for a cartoon for some purpose—to jazz up an advertisement, say— Cartoon Collections had one. It had virtually every cartoon ever published (slight exaggeration), all organized by topic.

But that’s not what attracted my attention in Mankoff’s announcement. He was “asked to leave” The New Yorker, he said. Ah, ha! So he was fired. But why?

HE SAYS it was for “appropriate behavior.” And “appropriate behavior” was “selecting the cartoons that I thought were the best regardless of the identity of those who did them.”

In those comments, we find a fairly broad hint about why Mankoff was fired. When we combine those comments with what the new cartoon editor said about cartoons and what she has been doing, we discover the reason for Mankoff’s firing.

The

new editor, a young woman named Emma Allen, was not, like Mankoff, also

a cartoonist.  Her understanding of cartoon humor was therefore not from the inside

out but, rather, from the outside in. At 29 years of age, Allen had been

working for a few years at The New Yorker, finding spot illustrations

for Talk of the Town and doing a little humor writing. For three years she

edited Daily Shouts, comic essays that have become one of the most popular features

on the magazine’s website.

Her understanding of cartoon humor was therefore not from the inside

out but, rather, from the outside in. At 29 years of age, Allen had been

working for a few years at The New Yorker, finding spot illustrations

for Talk of the Town and doing a little humor writing. For three years she

edited Daily Shouts, comic essays that have become one of the most popular features

on the magazine’s website.

“Her ability to find new voices for Daily Shouts is what first attracted Remnick’s attention. ‘She was bringing in people and things that I hadn’t heard before, and sometimes you need to reinvigorate parts of the magazine,’ he told Jason Zinoman at nytimes.com by phone, adding, ‘We need to have a deeper exploration of the web, as far as cartooning.’”

Allen graduated from Yale, where she wrote a humor column for the campus newspaper. But humor writing and humor cartooning are not the same.

When Zinoman asked how her taste in comedy differs from that of her predecessor, Allen said: “I think I have a slightly weirder sense of humor,” adding later, “As much as I like observational gags, I also like things that are more surreal.”

As the new cartoon editor of the magazine, Allen become a steward of The New Yorker’s long established tradition. But she was bent on changing it, too. She told Zinoman that “promoting the kind of refined wit the magazine has long been known for mattered less to her than publishing voices that are genuinely funny and representative of comedy today.”

“I don’t feel beholden to finding the next Benchley or a Benchley knockoff,” she said. “I like things that are witty. I also like dumb fart jokes. The high-low spread is much more interesting than trying to mummify a thing and keep presenting it all over and over again.”

Allen also said that she hoped to expand the kinds of cartooning online, and, in print, she wanted to try more work with multiple panels, and she wanted to pair joke writers with cartoonists on some projects.

Her interest in surreal comedy emerged almost at once in her tenure.

“Surreal”

originally was applied to an artistic movement of the early 1900 that had the

“intense irrationality of a dream.” Since then, the word has referred to “the

practice of producing fantastic or incongruous imagery or effects in art,

literature, film, or theater by means of unnatural or irrational  juxtapositions

and combinations.”

juxtapositions

and combinations.”

“Irrational juxtapositions and combinations.” That has distinguished the cartoons Allen has selected. And one of the most conspicuous incongruous juxtapositions can be found in the talking animal cartoons that have multiplied in profusion since she assumed the editorship.

In a winter issue of the magazine, there were 16 cartoons; 4 of them were talking animal cartoons. That’s 25% talking animals.

And that percentage is pretty constant from issue to issue. In another recent issue, 5 of 15 cartoons (5/15) were talking animals; 33%. Then 3/11 (27%), 4/11 (28%).

And even the cartoons with human speakers are surreal—combining incongruous elements.

|

|

Over the last six months or so, the new emphasis on “surreal weirdness” has undermined The New Yorker’s historic role as a commentator on our culture’s self-absorption. The magazine’s cartoons had usually made fun of the pseudo sophisticate in its urban environment. The comedic reference was to life in New York, to American society, and to politics (a little).

“With The New Yorker,” Russell Baker wrote, “American humor began to master the arts of understatement, to refine the crudities of old-fashioned burlesque into satire, to treasure subtlety and wit.”

In short, New Yorker cartoons until Emma Allen were satirical.

But Emma Allen’s choices of cartoons for the magazine are not satirical. She likes silly instead.

With the rise of silly at The New Yorker, the last great venue for single panel satirical cartoons in America has slowly evaporated. Satire is gone; silly is rampant.

And then there’s the matter of slowly deteriorating quality in the drawings themselves; but that’s a subject for another time.

What I think Remnick saw in Allen was the prospect of something he wanted.

What he wanted in the magazine was greater diversity among the contributing cartoonists plus some unspecified “newness”—something “fresh,” invigorating— in the formal nature of the cartoons themselves. Mankoff probably agreed with Remnick on these matters, but he wasn’t willing to devote much energy to a search for such things.

I can imagine heated discussions between Mankoff and Remnick on the issue. And Mankoff would say, “If we go after good cartoons, funny cartoons, the rest—new voices, diversity among contributors— will just come along with them.”

But Remnick wanted results faster than that, and he thought Allen could achieve them. She’d already demonstrated a talent for developing new invigorating approaches in Daily Shouts. To let Allen exercise this talent in the magazine’s cartoons meant Remnick would have to let Mankoff go. And that’s why Mankoff was fired.

We’ve reached this conclusion by consulting two sources: first, what Mankoff said at his leaving; second, from what has happened at the magazine since Allen’s elevation.

When Mankoff left, he went to some pains to list all the “new” cartoonists he’d brought into the magazine. He was shoving it in Remnick’s face:

“You want new talent? Look— I brought in new talent, plenty of it.

“You get the idea,” he finished, “—so why fire me?”

Emma Allen has also brought new cartoonists into the magazine—most notably, the first African American cartoonist. A female African American cartoonist!

Two years ago, Liz Montague was only 22, and while she was doing an autobiographical cartoon, Liz at Large, for the weekly Washington City Paper, she hadn’t quite decided on a career as a cartoonist.

She was looking at some New Yorker cartoons one day when she suddenly realized that all the people in the cartoons were white. And that meant, probably, that all the cartoonists were white, too. And the editors. So she wrote the magazine, expressing her dismay. Her e-mail was forwarded to Allen and landed on her desk at a propitious moment.

Said Allen: “I was amazed at how she so exactly expressed the frustrations I was grappling with as I sought both to support those cartoonists who had been contributing to the magazine for many decades and also to recruit and promote many of the fresh, eclectic, exciting voices working in the wider world of comics and graphic arts. In the e-mail exchange that followed, I asked her if she had ideas of cartoonists I should be looking at and publishing, and she said, ‘Me.’”

Said Montague: “I was, like, I could take a stab at this.”

So she did. She says she submitted 150 cartoons before one was accepted. Montague considers this a long courtship, but The New Yorker is legendary for rejecting cartoons and for rejecting new cartoonists. Through the magazine’s history, most of its cartoonists submitted cartoons for years before selling one. Years and thousands of cartoons.

Montague’s

first accepted cartoon appears at the upper right on the accompanying visual

aid.  It was

published in the magazine’s Instagram account. Since then, she’s had four more

published in the print magazine.

It was

published in the magazine’s Instagram account. Since then, she’s had four more

published in the print magazine.

Although Montague presumably brings a different perspective to her cartoons, she says (ironically) that if she’s learned anything in the past year, it’s that people aren’t that different.

“It’s made me realize,” she says, “that we’re all a lot more similar.”

Montague’s perspective is more that of a young person than of a Black person. In one of her published cartoons in the magazine two children stand next to a man tied to a chair. The caption: “Now show him projected sea levels on his golf course.”

Allen says she can’t be sure that Montague is the first Black cartoonist to be published in The New Yorker: she doesn’t know the racial identity of all the contributors. But about Montague, she and Remnick were certain. And they (I assume it was they) put out the news joyfully. The story was picked up by the Washington Post, ABC News, and websites Yahoo and In the Know.

How would Mankoff have handled Montague’s introductory e-mail? Who knows?

He says he’s always been guided by “appropriate behavior,” which means he tried to pick cartoons that were funny. In other words, he did not go looking for cartoonists in racial minority communities. He went looking for funny cartoons regardless of who drew them.

But he always kept his office door open to newcomers. I’d like to think her comment about the need for diversity would have prompted him to respond somehow.

As for something different in the cartoon medium, Mankoff promptly brought exactly that ingredient to the cartoons he selected as cartoon editor at Esquire.

UPON ARRIVAL at Esquire, Mankoff said he intended to invent an entirely new look and sensibility in cartooning “by upping the aesthetics and embracing a wide set of fresh voices,” said Esquire’s editor-in-chief Jay Fielden in introducing his cartoon editor.

Mankoff imagined that his new approach could “reinvigorate the ecosystem of magazine cartoons.”

He believed there’s a better way to nurture good cartooning that just leaving the office door open to all comers. “It’s important to use these editorial muscles that I’ve developed over all these years,” said he.

His new process would involve working closely with a handful of different cartoonists every issue. He’d suggest a topic to a cartoonist, and the two of them would develop a cartoon in collaboration. Mankoff wouldn’t work just with artists, but also performers:

“I want stand-up comedians to work with cartoonists, too, to [explore] what a stand-up sensibility could be in a magazine.”

And given today’s technology, collaboration can be achieved in “a virtual writers’ room” — one in which a stand-up like Pete Holmes, Mankoff says, might work with cartoonists like Alex Gregory and Matthew Diffee, who grew in prominence within the pages of The New Yorker.

“Combining different skill sets could be very powerful in … heightening the quality of humor,” Mankoff says. “That’s my ambition through collaboration, and that’s [new Esquire Editor in Chief] Jay Fielden’s ambition, too. ...

“ I look forward to working with new talent, too. It will be a commission process, essentially, like working together on an article. We will all have skin in the game, writers can be emboldened — and my door is open.”

While Mankoff’s plan seems novel, it actually isn’t all that new. As he observed himself, his idea harkens back to the way The New Yorker worked on its cartoons for the first 25-30 years. It was an approach “that began to lose favor in 1952, when William Shawn [became editor and] began encouraging the magazine’s artists to develop their own voice rather than to rely on gagwriters,” observed cartoonist Michael Maslin at his Inkspill blog.

“While using gagwriters is still an approach employed by a very small number of New Yorker cartoonists,” Maslin continued, “it has been largely out of favor at the magazine since the early 1970s. Roz Chast, in a brochure for an exhibit of New Yorker cartoons, wrote that she felt the use of gagwriters was ‘like cheating.’”

During the brief time he was Esquire’s cartoon editor, Mankoff didn’t find much new talent. The cartoonists he worked with were New Yorker cartoonists that he’d discovered while working at that magazine.

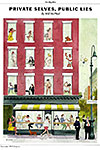

The

first cartoons developed with this process were not the traditional

single-panel cartoons. Conspicuously, they were full-page cartoons with a

whimsical sense of humor rather than a punchline.  One such specimen early on

was a cut-away cartoon of a building showing people inside rooms within doing

different things, all revealing something about daily life. Whimsical, as I

said. But not terribly funny.

One such specimen early on

was a cut-away cartoon of a building showing people inside rooms within doing

different things, all revealing something about daily life. Whimsical, as I

said. But not terribly funny.

And Emma Allen has been selecting similar cartoons for The New Yorker.

When she was appointed, she said she thought of cartoons as visual decorations intended to spice up The New Yorker’s pages of gray type. She also said she preferred “long form” cartoons—i.e., comic strips—rather than single-panel cartoons. And multi-panel visual “essays.” And we’ve been getting cartoons of that order more recently of late. Hereabouts, I’ve posted examples.

|

|

|

So, to return to our opening query—Why did Mankoff leave The New Yorker? The short answer: he was fired. The longer answer: he and editor Remnick couldn’t agree on a way to achieve Remnick’s objectives without, in Mankoff’s view, sacrificing the quality of the cartoons.

The New Yorker’s cartoons, under Emma Allen, are doing what Remnick wanted—experimenting with the form. The irony is that, in terms of cartoon form, Mankoff was doing pretty much the same thing during his short-lived stint at Esquire—re-invigorating the nature of magazine cartooning.

But Mankoff wasn’t searching for talent in racial minority communities. And racial diversity was apparently at the top of Remnick’s list of things he wanted in the magazine’s cartoonists. Because Mankoff wouldn’t agree to put that at the top of his list, he was fired.

I’m scarcely denigrating Remnick’s intention here. Clearly, in this day and age, The New Yorker needs to attend to a society larger than its traditional all-white venue. I wish only that Mankoff had been more agreeable to exploring this aspect of Remick’s charge: then we’d have racial diversity, formal experimentation, and satire. Instead of just silliness.

And an American cartoon institution would still be viable.