PERPETUAL BLONDIE

Chic Young’s Forever American Family

Blondie, Chic Young’s monument to syndicated

newspaper comics, began as a "flapper" strip about a dizzy young

blonde named, with unrelenting perspicacity, Blondie. This was Young's fourth

pretty girl strip: starting October 31, 1921, he'd done The Affairs of Jane at

NEA. for six months until March 18, 1922; and then he'd come to New York and

done Beautiful Bab for Bell Syndicate for almost a year (July 10, 1922 -

April 14, 1923) before joining the King Features art department in 1923 and,

after a suitable apprenticeship, creating Dumb Dora on June 30, 1924. Dora proved popular enough to last longer than its forerunners, and when the 1929

stock market crash wiped out his savings, Young, thinking he had leverage,

lobbied for more money.

But he met immediately a parsimonious obstacle in Joseph V. Connolly, King's energetic and imaginative general manager, who was not inclined in the direction of salary increases. Young threatened to quit; Connolly still resisted. So Young packed himself and his wife off to the French Riviera to make his point. When Connolly wired, pleading him to return, Young consented—but only for a bigger piece of the action and ownership of the new strip he would concoct. Connolly agreed, provided Young could come up with an acceptable creation. Returning to New York, Young spent the summer of 1930 devising a new strip. It was yet another pretty girl feature so it couldn’t have taken that much devising, but this one would reign as one of the world's most widely circulated strips for longer than just about anybody. But, as we shall see anon, it did not achieve this prominence as a pretty girl strip.

By the time Young got to Blondie, he had honed his drawing style. Although the mannered manikin poses persisted in his renderings of his heroine, his line was a little freer, lighter, better suited for limning Blondie’s lithe winsome figure. His spotting of solid blacks gave the pictures a pleasant, eye-appealing accent, and his deployment of gray tones molded figures while imparting visual variety to the passing scenes. And Blondie’s wardrobe had achieved a frilly femininity that Dora’s only hinted at. Some of the daintiness slowly disappeared over the years, but Young and his assistants always turned out a fashionably attired and physically appealing Blondie, perhaps the sexiest comic strip character in the funnies. In the 1950s, the stylistic tropes of Young’s drawings assumed iconic status: it was as unthinkable to alter the number of curls on Blondie’s head as it was to eliminate Dagwood’s antenna. The characters in the strip were always rigorously “on model.” But Blondie’s figure had expanded somewhat: as Liberty Meadows’ Frank Cho observed (while fighting to preserve Brandy’s figure), Blondie’s bust was the stuff of Playboy centerfolds.

As a limner of the curvaceous gender, Young had unlikely roots. Although born in Chicago in 1901, he grew up in south St. Louis where his family moved early in the century. The south side of St. Louis was an enclave of German-Americans so Chic’s Lutheran father, a shoe salesman, felt at home, and his children inherited such stolid Teutonic neighborhood traits as stubbornness, dedication, and frugality. Nothing artistic inherent in that mix, but art dominated in the family milieu. Chic’s mother was a painter who encouraged artistic expression in her children. Her daughter was a commercial artist before she married; Chic’s older brother, Lyman, would make a life’s work out of a boys adventure strip, Tim Tyler’s Luck; and another brother, Walter, painted. Lyman encouraged Chic (whose actual name was Murat Bernard) to pursue drawing, and Chic dutifully scribbled away. In high school, his pictures decorated the yearbook. But his father’s practicality urged him into other pursuits as a way of earning money. (His father, reported Rick Marschall in Blondie and Dagwood’s America, “never quite understood how artists could think they were doing honest work.”) After school, the teenage Chic worked as a postal clerk on weekdays, and on Saturday, he worked in his father’s shoe store.

After graduating from high school, Chic went to Chicago where he found a job as a stenographer while attending night classes at the Chicago Art Institute. Chicago at the time was a hotbed of cartooning talent, all on the cusp of fame—Billy DeBeck (Barney Google), Elzie Segar (Popeye), Frank King (Gasoline Alley), and Carl Ed (Harold Teen); all drew in a kindred manner that came to be called “the Chicago school.” One of Chic’s classmates, Edgar Martin (creator, later, of Boots and Her Buddies) was hired by the Newspaper Enterprise Association in Cleveland and encouraged Chic to join him there.

Soon after arriving in the NEA bullpen, Young created The Affairs of Jane. Jane, Brian Walker explains (in Chic Young’s Blondie: The Complete Daily Comic Strips from 1930-1931), was a conniving female: “A highschool dropout who was courted by a string of hapless suitors, Jane concocted get-rich-quick schemes in a desperate attempt to escape from her modest, small-town circumstances and had a brief career as a film actress.” But Young got into a salary dispute with his bosses, and both Jane and her creator were shortly thereafter terminated. Then Young went to New York, where, as we’ve noted, he created two more pretty girl strips before inventing Blondie in the aftermath of another salary dispute.

Blondie Beginnings. Before Blondie debuted, it enjoyed a legendary promotional campaign that began (as Walker tells us) when newspaper editors around the country were sent an announcement of the engagement of Dagwood Bumstead to Blondie Boopadoop. This was followed by a letter from the Bumstead attorney, who alleged the engagement announcement was “a pure fabrication of fancy, if not a malicious attempt on the part of this Miss Blondie Boopadoop.” After which came a handwritten note from Blondie herself, protesting her innocence and saying she’d soon arrive to explain “in person.” She also said she was sending her luggage on ahead: “When you get it, hold it for me and don’t peek inside.”

A few days later, a cardboard suitcase was delivered to editors’ offices, with a note from Blondie, admonishing: “Don’t peek into it.” It being a blatant promotion, everyone peeked. The suitcase contained women’s clothing—for a paper doll. Next, as promised, Blondie herself arrived—a cut-out paper doll in her lingerie. With a note: “Here I am, just like I told you I’d be. Only, please, Mr. Editor, put some clothes on me quick. I sent them on ahead, you remember my pink bag. I’m so embarrassed! Blondie.”

Those were the halcyon days of syndicate promotions.

“In spite of King Features’ ambitious promotion,” Walker writes, “Blondie sold only moderately. It debuted on September 8, 1930, in a few small city newspapers [but didn’t] appear in Hearst’s New York American [until] September 15. New [subscribing newspapers] usually ran the first twelve episodes to fill their readers in on the background story and then picked up the continuity from there.”

Yes,

continuity: the first years of Blondie were storytelling years, the

story of a courtship. Dagwood introduces Blondie to his grumpy father, a

railroad tycoon, in the very first strip, but the two lovers don’t marry until

February 17, 1933.

For the intervening two-and-a-half years, the couple struggles to get Dagwood’s parents to consent to his marrying this very pretty but not, seemingly, too smart young woman who might well be a gold-digger, out after the Bumstead billions. While the impending nuptials are held in abeyance, Blondie, displaying a scatterbrain practicality, flatters the parental Bumsteads to earn their approval and almost wins them over when she inherits money until they find out the amount is $283. She even works for the Bumstead company for a time and becomes Mrs. Bumstead’s social secretary briefly. And occasionally, when off-duty, she entertains visits from young male admirers.

The flock of males that hovers around Blondie is not as numerous in the daily sequences as it is in the Sunday strips, which are not part of the daily continuity. In the dailies, Blondie displays more constancy. Although she enjoys the affections of an extraordinarily handsome neighbor, Gil McDonald, for a brief time (June through mid-October 1932), when her engagement to Dagwood has been called off—and is even engaged to Gil for a few weeks—Dagwood is never far away and is always, it seems, in her flighty young heart.

But as a pretty girl strip, Blondie was about to fade away after a couple years until Young and syndicate officials hit upon a way to resuscitate their somewhat dingy blonde. They decided to marry her off, and they picked Dagwood Bumstead, heir to the billions generated by the Bumstead Locomotive Works.

Dagwood goes on a hunger strike to wear down his parents’ resistance to his marrying Blondie, a stunt that attracted considerable press at the time and, naturally, stimulated circulation. Starting on January 3, 1933, the strike lasted until January 30 (official time—28 days, 7 hours, 8 minutes and 22 seconds), with a count-down posted every day in the strip as Dagwood wastes away. (Later, when he finally arises from his bed, we see heaps of dishes under the covers. Perhaps he’s been eating all the time? Ah, young love.)

His parents finally consent to the marriage, but Dagwood's father disinherits his son, a callous strategy perhaps, but one that opened the way for Blondie and Dagwood to become The American Newlyweds, then The American Young Mother and Father, and, ultimately, The American Family, a niche the strip has enjoyed for most of its 82-year history. The newlyweds take up housekeeping in much the same state as every other couple getting married during the Depression—virtually penniless. Which necessitated that Dagwood find employment. And that led eventually to his boss, Mister Dithers. And being late to work. And so on.

With their marriage, the strip became a domestic comedy, and readers encountered one of the most revolutionary of Young’s plot devices: Blondie and Dagwood sleep in a double bed, not twin beds, which was the fashion in entertainments of the repressive 1930s. According to an article in The Saturday Evening Post (April 10, 1948), Young “steadfastly refused” to be “bullied” by “skittish readers” into getting the Bumsteads twin beds. “He holds, and the fan mail he gets from clergymen sustains him, that twin beds constitute a major threat to the solidity of marriage. He is very stubborn about this.”

The solidity of the Bumstead marriage resulted in Baby Dumpling’s birth on April 15, 1934, and with that, the strip established itself as the pace-setter for its genre, inspiring almost as much merchandising in its heyday as Peanuts did in its. As a measure of its popularity: when Blondie and Dagwood produced a daughter in 1941 and Young ran a contest to name the new arrival, 431,275 people submitted suggestions. "Cookie" was the result.

Blondie was not much different from her predecessors, Jane, Bab and Dora—until she married. Like them, she was at first a witless flapper, but as a wife, her nonsense was often common sense (albeit uncommonly phrased or applied), and Dagwood emerged as the family flake. And then the iconic American domestic comedy began in earnest, raising the strip to hitherto unequaled popularity and soaring circulation for most of its run. So far. At the last tabulation I’m aware of (June 2002), Blondie was appearing in 2,000-plus newspapers, joining Dilbert and For Better or For Worse in the same bracket, behind only Garfield with 2,600 papers and Peanuts with 2,400. No other strips tallied more than 1,900 papers.

Sustaining the Icon. Chic Young undoubtedly created one of the medium's masterpieces. But he had expert help for most of Blondie's run. Ray McGill and Jim Raymond were assisting him in the 1940s. Raymond's stint on the strip began in tragedy. Young's first-born son, Wayne, died of jaundice in 1937 in the midst of the emerging popularity of Blondie and Dagwood's first-born, Alexander (aka Baby Dumpling). Unable to face doing gags about a toddler, Young and his wife took a sabbatical to Europe, leaving the strip in Raymond's care. Raymond continued to assist on the strip thereafter, taking over completely in about 1950 when Young’s eyesight began to fail. By the time he died in 1981, Raymond had possibly worked longer on the strip than Young—44 years (except for an interval in the late 1940s when he concentrated on Blondie’s Sunday topper, Colonel Potterby and the Duchess) compared to its originator’s 43.

Alexander, incidentally, was named for Raymond's older brother, who was one of Young’s assistants on Blondie for a time in early 1930s (he drew some of the wedding scene, for instance, and many of the supporting cast, such as Gil McDonald, who looks a little more a fashion plate than Dagwood and his comedic cohorts) but gained considerable more fame later as the creator of Flash Gordon, Secret Agent X-9, Jungle Jim, and Rip Kirby.

Jim Raymond's assistant, Mike Gersher, took over after Raymond's death, and when Gersher left the strip, he was followed by Stan Drake (1984-1997), who was assisted by Dennis Lebrun, who, in his turn, took over when Drake died in 1997 and was assisted by Jeff Parker for about nine years. Parker left when Lebrun did, in September 2005, and the strip then (and now) fell to John Marshall, who, in the custom of the strip’s management, is grooming an assistant to take over the drawing in some distant day in the future—Frank Cummings.

Stan Drake’s connection with Blondie was highly unusual. He’d made his name with The Heart of Juliet Jones, a soap opera strip that he drew in a superlatively illustrative manner. His work on Blondie, while thoroughly competent (and, in some respects—backgrounds, say—even realistic), always struck me as a little stiff (and sometimes excessively detailed for the style of the feature). His Blondie and Dagwood seemed wooden. But Lebrun revived the lively Raymond line, and the strip looked better under his hand than it had for years.

In fact, it looked better than a lot of its company on the comics pages. And still does. At a time when Cathybert and its ilk have made vacuous, stilted drawings the vogue, it’s refreshing to find a strip in which the characters change positions from panel to panel and register emotion and sometimes leap unrealistically up into the air, over high fences, into bathtubs, or race madly after disappearing buses, speed lines flaring, or trample postmen—behaving for all the world like characters in a comic strip (heaven forfend!).

Blondie is also one of the few strips with relatively complex drawings of characters

standing at their full height in virtually every panel, tightly drawn, every

detail in place, background figures completely rendered (including, often, the

entirely superfluous dog Daisy—perhaps the best cartoon dog ever—who reacts to

events like a miniature Greek chorus).

When Chic Young died in 1973, his son Dean took over writing the strip although he has probably ever since been relying upon gag writers (as, probably, did his father); for at least twenty years, Paul Pumpian was reportedly chief among them. In this practice, the Youngs share common ground with most of their inky-fingered brethren. Dean had been working with his father since the early 1960s before assuming the whole task of managing the verbal and visual comedy of Blondie. In recent years, he has attempted to bring the strip into contemporary suburban America by giving Blondie a catering business to run, but the focus of the strip remains pretty much what it has always been: the basic aspects of ordinary living—eating, sleeping, earning a living, and managing a household.

Dagwood and his family are ordinary folks, and most of Dagwood’s adventures begin normally enough. But before a strip reaches its punchline, a manic inventiveness, an impish perversity, inspires a zany deviation from the norm, and Dagwood, cowlicks akimbo, transcends the mundane and achieves the implausible. For those of us who lead similarly ordinary lives, the famous Dagwood sandwich is the emblem of this transition: even the humble sandwich can attain heroic, if lunatic, proportions. Thus, in the most common of our pursuits, the seeds of laughter germinate, threatening to redeem us from an unremitting sense of self-importance.

When being interviewed, Dean Young usually permits those who are talking with him to assume that he draws the strip as well as writing it. Asked during the online chat why Daisy's five pups never show up anymore, Young said: "I imagine they are somewhere in the neighborhood, but, in my tenure, I found that drawing five little puppies in each panel was more than I can bear."

He doesn't say, precisely, that he's drawing the strip—that is, "drawing" in this context could be taken to mean "pictures of five little puppies in each panel was more than I can bear to contemplate all the time." Usually, however, he refers to the art chores as something that "we" perform, nicely ambiguous. In fact, someone draws, and he, Dean, critiques the pictures. “We.”

We can scarcely fault Young for this coyness: comic strip cartoonists are notorious for keeping the names of their assistants under wraps (and, in many cases, even pretending that they have no assistants). Young mentioned none of his drawing partners in the online chat I've quoted from, but he revealed that he has been assisted by his daughter Dana for 16 years (i.e., 1989-2005). Said Young: "She's been working in a creative capacity, and I hope she'll be able to take it for the next 75 years." Reading the transcript of the chat, we would suppose that the "we" Young occasionally invokes is only he and his daughter. But hereabouts, we know better, eh?

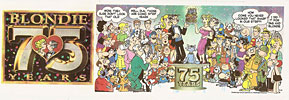

Anniversaries

Galore. This

September, Blondie is 82 years old. That doesn’t make it the oldest

still running daily comic strip (that’d be Gasoline Alley, which started

in November 1918; presently being written and drawn by Jim Scancarelli), but

octogenarian altitude is hard to ignore. Anniversaries are customarily

celebrated only when round figure are involved—25, 40, 60, etc.—but Blondie has

had enough of those to qualify for a few paragraphs here. The strip recognized

its 50th anniversary with the understated Sunday celebration we see

hear here. But when

the 75th anniversary approached, Dean Young pulled out all the stops

and pressed all the buttons.

But when

the 75th anniversary approached, Dean Young pulled out all the stops

and pressed all the buttons.

The

festivities began in July 2005, orchestrated for a September crescendo.

Ostensibly, the summer’s storyline concerned the couple’s wedding anniversary,

but that was in February, not September. In seeming defiance of this fact,

Dagwood and Blondie and their offspring, Alexander and Cookie, spent weeks that

summer planning a gala anniversary party. Meanwhile, other comic strip

characters alluded to the forthcoming event in their own strips—Garfield,

Zits, Mutts, Beetle Bailey, Hagar, For Better or For Worse, Mother Goose and

Grimm, B.C., Wizard of Id, The Family Circus, Marvin, Dick Tracy, Gasoline

Alley, Curtis, and Bizarro. And Young included these characters in Blondie. Then on September 4, all the other comic strip characters came to the party, as

we see in the accompanying exhibit.

Young chose September 4 rather than the historical date, September 8, because the 4th was a Sunday, and the celebration, as planned, needed the space that Sunday strips offer. That Sunday, almost four dozen characters from as many different comic strips convened in Blondie. Lebrun did all the art, a mob scene that includes, in addition to the visitors from other strips, the Bumstead family and six or seven other cast members, boosting the teeming throng scene to about fifty characters. Lebrun's mastery of mimicry runs a gamut from the simplicity of Ziggy and Dilbert to the more elaborately rendered Herman and, even, Flash Gordon. A stunning performance, and Lebrun's last on Blondie. But no signatures appear on this installment— probably because there are so many cartoonists represented by the picture. A grace note.

There are three gags in the celebration—one about comic strip aging, one about Beetle's dress uniform, and, a delicious sight gag, the anniversary "cake" is actually a Dagwood Sandwich with candles on it. Nice touch.

It's undeniably an epochal occasion: I can't think of any other time in comics history when so many comic strip characters from different strips appeared together in a single release. In the early 1900s, Happy Hooligan sometimes wandered into other strips and vice versa. Nothing on the scale we have here. But was it, as everyone supposes, a wedding anniversary?

Blondie herself had been pretty coy about it all along: on July 10, when the storyline began, she says to Dagwood: "I can't believe you still haven't figured out which anniversary we have coming up!" Dagwood is stumped, but Blondie finally tells him, "It was when we began our lives together!"

Blondie's right, of course. But she's being deliberately ambiguous. She's alluding not to their wedding day, which was February 17, but to the fabled first day of the strip, when Dagwood introduces her to his father. That's when their "lives together" began, after all.

Dagwood, however, thinks she's talking about their wedding anniversary. So when I first heard of this stunt, I suspected that the punchline of the story would hit Dagwood on September 4 when he'd find out it's not their wedding anniversary that he's been planning a party for all summer. To turn that circumstance into a joke would require "breaking the fourth wall," of course, but that happened in various installments during the two weeks prior to the party so it wouldn't do unprecedented violence to the fiction of the strip.

Young is perfectly aware that the entire storyline conflates the wedding anniversary and the strip's debut, but he chose not to acknowledge in the strip the dual nature of the celebration. And then the guest appearance notion probably took over and swept all other nuances aside.

Said Young: "It started when I was trying to decide what exactly I wanted to do for Blondie and Dagwood's anniversary party. Then the idea came to me that I wanted them to celebrate with the rest of their friends from the comics pages. When I realized that all these comic characters would be with the Bumsteads at their big anniversary party, the idea occurred to me that it would be a lot of fun if those characters showed up unexpectedly at the Bumsteads' house two weeks early. ... And then it got more legs right away when I started speaking to my fellow cartoonists, and all of a sudden we're into my colleagues in the industry doing references to the Bumsteads' big party in their strips."

Unusual—even unprecedented—as the event is, it didn't feel all that odd to Young. "It doesn't feel strange at all," he said during an online chat with fans. "They're all neighbors of the Bumsteads, a couple inches to the left or right, or a little up or down, so it's like the whole wacky, zany community that they live in. That's their world, so it actually feels real."

Some of the other cartoonists let Young in on what they were doing in their strips—and when they did, Young got his drawing partners to "tweak our characters, being the sticklers we are"—but Young was just as often kept in the dark and happily surprised by what he saw in other strips.

|

|

Besides the anniversary party, Young achieved a couple other historic moments in the strip. When Mother Goose's Grimm shows up on August 25, he invades the bathroom to drink from his usual appliance: we've seen the Bumstead bathroom thousands of times—Dagwood soaking in the tub or shaving at the sink—but this is the first time the toilet has been depicted.

And

on Sunday, August 28, the Prez of the U.S., GeeDubya, and his wife Laura make

an appearance.  The

caricatures of these two notables seem to me deftly done, better, in fact, that

we have a right to expect in the usual non-political milieu of a syndicated

comic strip. In this case, however, the cartoonist has had practice on

political personages: Jeff Parker, who, until the end of July, was one of the

cartoonists producing Blondie, is also the editorial cartoonist on Florida

Today. Parker also drew Grimmy with great elan, I thought. No surprise: his

other moonlighting gig is on Mother Goose and Grimm. Parker is obviously

expert at aping the graphic mannerisms of others: he also drew all the

characters from other strips who collected on the Bumstead lawn one day in

August.

The

caricatures of these two notables seem to me deftly done, better, in fact, that

we have a right to expect in the usual non-political milieu of a syndicated

comic strip. In this case, however, the cartoonist has had practice on

political personages: Jeff Parker, who, until the end of July, was one of the

cartoonists producing Blondie, is also the editorial cartoonist on Florida

Today. Parker also drew Grimmy with great elan, I thought. No surprise: his

other moonlighting gig is on Mother Goose and Grimm. Parker is obviously

expert at aping the graphic mannerisms of others: he also drew all the

characters from other strips who collected on the Bumstead lawn one day in

August.

Dagwood’s encounter with the President echoes an actual event in Chic Young’s life. When he was working at NEA on Jane, he labored in “the monkey house,” a bullpen full of the syndicate’s cartoonists. Walker tells the tale: “Their boss sat at a desk in front, watching the hired hands closely while they toiled at their drawing boards. They had to raise their hands to ask permission to leave, and office pranks were the only way they could relieve the boredom. One day, the phone rang, and Chic answered it. The caller said he was an executive from a major syndicate and offered him a job for $10,000 a year. Convinced it was a practical joke by one of his co-workers, Young gave the man a phony address and hung up. He later discovered that this had been a real call from King Features talent scout Marlen Pew, and he had missed his first big break.”

Odd Looking Stuff. I exchanged a few e-mails with Parker, and he mentioned visual oddities in the strip other than those represented by the invaders from other strips. "There's an eye issue," he said: "Dag's two big ellipses are like no other character's eyes in the strip (apart from his clone, Alexander). Did they just morph out of the small ovals that he originally had? They always look very out of place to me since no one else in the strip sports big ovals for eyes."

Parker

also noted the strange whimsy that the Bumsteads' neighbor, Herb Woodley, and

the mailman, Mr. Beasley, look alike, "the only distinctions being that

Herb has a cleft chin and Beasley has a solid round chin-also, harder to notice

since the mailman is always wearing a hat, but Beasley has less hair than

Herb."

Dagwood’s eyes were for most of the first years of the strip not unique to him; while most other characters had eyes with lids, a few, like Dagwood, had dots, and the dots, in all of them (including his mother), gradually elongated; still, by the end of Blondie’s third year, Dagwood’s were the only large oval eyes in the strip. And they kept expanding vertically.

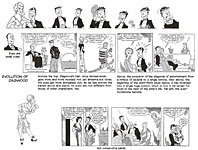

We cannot leave these premises without saying something edifying about the most conspicuous of the strip’s visual anomalies—Dagwood’s notorious antenna hair-do. But just as peculiar is the single button in the middle of his shirt front. Oh—and the graphic signal of astonishment, a lone exclamation point without a period that suddenly appears over the head of the astonished personage.

To take these matters in reverse order

(also the opposite of the way they are illustrated in the accompanying

exhibit): the single exclamatory mark of astonishment was once part of an

array, a halo of similar lines, as you’ll see at the bottom of our visual aid.

Young slowly eliminated all but one of the dagger-like diagonals.

Dean once explained that his dad joked that he drew a single big button on Dagwood’s shirt front because it was easier to draw than several little ones. Indubitably true. But it doesn’t really explain this aberration. Close inspection of some of Dagwood’s early appearances suggests that the button in question is the residual remnant of a shirt stud, the sort that you found in the thirties on the fronts of starched dress shirts worn by the men in the Bumstead circle when they were dressed formally for dinner in the evenings. At first, the “button” appeared only when Dagwood was wearing a tux; over time, Young just kept putting it on Dagwood’s shirt, apparently forgetting what it was originally.

Finally, Dagwood’s very strange hair-do simply evolved, a graphic distortion gone absolutely wacko. I’ve arranged a sequence of Dag portraits from the first years across the top of our handy visual aid. At first, his hair was parted in the middle and was thoroughly plastered to his skull in the fashion of the day; but when he was frustrated or frazzled, the hair came somewhat unplastered over his forehead, sprouting two untamed hanks of hair. After eighteen months, Dagwood’s head has not yet sprouted antenna; but, forelocks askew, he’s on his way. And as we’ll see in a trice, Young and his cohorts these days are not above making fun of this tonsorial oddity.

Another of the strip’s peculiarities involves the rendering of the male characters’ shoes. While Blondie’s wardrobe keeps up with the fashions of the day, the men are wearing shoes the way they were drawn a hundred years ago.

But

when the 75th anniversary celebration continued in Blondie in

September 2005, the Bumsteads went on a “second honeymoon”—in Hawaii. Blondie

in a bikini. Whoop!

Oh—almost forgot: Dumb Dora, which Chic Young abandoned in the spring of 1930, was continued first by Paul Fung until September 3, 1932; and then by Bil Dwyer until it ended in January 1936. It didn’t last as long as Blondie. But Dora never married.

And just so we end this pictorially rather than verbally, here are a handful of some memorable moments in the strip, beginning with evidence of Alex Raymond’s hand at work and concluding with a few glimpses of “today’s” Blondie.

|

|

|

|