|

The

Blackhawk Mysteries

Will

Eisner, Chuck Cuidera, and Reed Crandall

Chuck Cuidera

rolled down the aisle in Artists Alley on the first day of the 2001 San Diego

Comic Convention. He had attended his first Con just two years before. Then, he

had been walking; now, he was in a wheelchair, having lost a foot to one of the

maladies that afflict the older organisms. And Chuck was one of them: he was

86, and, just a month later, he would die. But now, on Thursday morning, July

19, he was looking forward to seeing and being seen by Golden Age fans whose

existence he had only recently discovered.

In

this milieu, he found at long last the respect, even veneration—a regard almost

reverential—that his work as a young man should have earned him sixty years ago

but didn’t because then comic books were seen as cheap, gaudy juvenile junk

entertainment whose artisans were, mostly, anonymous. Now in his ninth decade,

he had learned, much to his astonishment, that the artistic endeavors of his

generation of comic book cartoonists were enthused over by rhapsodic devotees

whose number, while not legion, was considerable and whose passion was

unmistakable. That Chuck enjoyed the attention is evident in his having made

the journey all the way across the country from his home in Florida, an arduous

journey for anyone his age but triply so if encumbered by a wheelchair. That he

deserved the attention is beyond dispute.

As

he rolled by the table where I was setting up, I greeted him.

“I’m

Chuck Cuidera,” he responded. “I did the Blackhawks.”

“Yes,”

I said. “I know.”

He

was pleased that I knew. My knowing established his identity with me, and,

since he didn’t have to perform the tedious ritual of credentialling his

bonafides, he could plunge ahead into conversation about the only thing that,

he figured, would be of interest to someone at the Sandy Eggo Con. Blackhawk.  We talked

a little about Everett A “Busy” Arnold, the publisher whose Quality Comics

fostered such memorable characters as Plastic Man, Uncle Sam, The Ray, and The

Spirit as well as Blackhawk. Did he know Arnold? We talked

a little about Everett A “Busy” Arnold, the publisher whose Quality Comics

fostered such memorable characters as Plastic Man, Uncle Sam, The Ray, and The

Spirit as well as Blackhawk. Did he know Arnold?

“I

was his art director,” Chuck said proudly with the air of a man making a

revelation.

But

that had been after World War II. Cuidera had gone into the Army Air Corps in

1942, after producing only the first eleven adventures of Blackhawk and his

airborne minions, the Blackhawks, for Arnold’s Military Comics,

beginning in August 1941. And when he returned to Quality Comics after the War,

another artist, Reed Crandall, had become so closely identified with the

Blackhawks that Cuidera was assigned to a different character, Captain Triumph.

He

continued to work for Arnold, sometimes on Blackhawk stories and, for a time,

as art director, until DC bought the Quality titles in 1956; thereafter,

Cuidera worked for DC, inking Dick Dillon’s pencils on Blackhawk and doing

other art chores. In 1970, he left comics and became a city planner for Newark,

New Jersey. When he retired, he and his wife went to Florida.

I

had steered our conversation to Arnold rather than to the more obvious

conversational destination of the Blackhawks because I didn’t want to get into

the touchy area of who had created Blackhawk. Will Eisner, who was “Busy”

Arnold’s partner in those years of yore, is usually credited with inventing the

character, but when Cuidera surfaced a few years ago in an interview in Comic Book Marketplace (No. 68, May 1999), he had rather loudly denied

Eisner’s role, saying that he and Bob Powell, another artist in the Eisner

shop, had conjured up the quasi-military troupe while Eisner was off hunting

somewhere in the South.

“I

created Blackhawk,” Cuidera said. “Bob Powell helped me write the first story.

As a matter of fact, he did most of it. I had completed [the artwork of] the

whole first Blackhawk story when [Eisner] got back [from his hunting trip]. I

didn’t have every character then, but I had the story done.”

When

it was announced that Cuidera would be a guest at the Comic Con that summer,

just a few months after his revelation in Comic Book Marketplace, and

that he and Eisner would appear together in one of the Golden Age panels

moderated by Mark Evanier, speculation ran rampant about what, given Cuidera’s

unequivocal assertion and even somewhat belligerent stance (“Will Eisner and I

didn’t get along”), promised to be a colorful showdown between the disputants.

Evanier, however, was not about to stage manage a fight, and, if I recall

aright, he arranged a private confabulation between Cuidera and Eisner before

the panel assembled, and during that meeting, whatever strife existed was

smoothed over to each party’s satisfaction.

During the

panel presentation, Eisner cleared the air with a gentlemanly proclamation:

“I’ve

been wanting to say this for a long time, because I’ve done conventions a lot,

and there’s been a lot of talk about who invented what. It’s not important who

created it. It’s the guy who kept it going and made something out of it that’s

more important. Whether or not Chuck Cuidera created or thought of Blackhawk to

begin with is unimportant. The fact that Chuck Cuidera made Blackhawk what it

was is the important thing, and, therefore, he should get the credit.”

Eisner

was being both generous and canny. And accurate. Surely it is true that whoever

puts flesh on the bare bones of a embryonic concept should have the greater

share of the credit for creating the feature. While acknowledging that Cuidera

played the most significant part in perpetrating the Blackhawk mythos, Eisner

didn’t disown the creator’s role. He shifted the credit, but, by implication,

he retained his role as the inventor of the character. But later in the panel’s

discourse, the issue was clouded anew.

In

discussing the first Blackhawk story, Eisner remembered that it was a feature

called “The Death Patrol” that led to the creation of the Blackhawk team.

According to this recollection, Arnold, who apparently kept a close eye on what

transpired in the titles he was publishing, saw “The Death Patrol” and said he

wanted another feature like it.

“The

Death Patrol” was produced by Jack Cole, who joined the Arnold enterprise in

the late fall of 1940. He had been doing an imitation Spirit in Arnold’s Smash

Comics since the January 1941 issue (No. 18), and about the same time that

he produced the first Death Patrol story that spring, he also did the first

Plastic Man tale for the inaugural issue of Police Comics (cover-dated

August 1941). The Death Patrol, dubbed in the first story “a Foreign Legion of

the air,” was made up of a group of escaped convicts, all pilots, led by a

playboy aviator named Del Van Dyne. Eager to do something worthwhile in these

months before the U.S. entry into the War, they all go to England and join the

RAF effort as a sort of free-wheeling squadron against Hitler’s Luftwaffe.

Drawn in Cole’s customarily exuberant style, the first Death Patrol story is

packed with headlong action and odd-angle shots.

The

members of the Patrol are picturesque characters whose eccentricities make them

comedic: Slick Ward, an ex conman; Peewee the forger, whose giant physique

mocks his name; Hank the cowboy, former rustler; Butch O’Keefe, safe cracker

from Brooklyn; and an old timer named Gramps, who earned his way as a

pickpocket. This crew, animated by Cole’s exaggerated action style, gave a

humorous aura to the stories (more so here than in Cole’s other two Quality

efforts at the time), but every Death Patrol tale ended on a somber note: in

each adventure, one of the group dies in battle. With every issue of Military

Comics, a new recruit joins the Death Patrol and another member dies.

When,

at that 1999 panel discussion, Eisner allowed as how the Death Patrol had

inspired the Blackhawks, there was a tremor of puzzlement through the audience,

me included. Since the first Death Patrol story and the first Blackhawk story

appeared in the same August 1941 issue of Military Comics (No. 1), how

could one have inspired the other? Speculation at the time was that the

inspiration came to Arnold as he looked at the artwork for the first Death

Patrol before it was published. And that, doubtless, is what happened.

But

wouldn’t the first Blackhawk story have been in its final state just then

too—well along in the production cycle, rolling, deadline driven, at July

publication? And if so, how could the Death Patrol exert any influence?

Puzzling, but after DC published the first volume of the Blackhawk Archives,

we had a clearer view of the Blackhawk landscape.

With

the first 17 of the Blackhawk stories before us in the Archives,

particularly the first two tales, it seems entirely possible that the notion of

the Blackhawks as a merry band of aviating derring-doers was not part of the

original Blackhawk concept. We have for so long held in fond memory’s embrace

the images of these tumbling fist-fighting combatants, punching their way

across war-torn Europe and wise-cracking as they go, that we are unlikely to

think of Blackhawk without also thinking of his teammates. But little in the

first Blackhawk story in Military Comics No.1 overtly indicates that

Blackhawk will lead a footloose band of fighter pilots in future exploits. A

squadron perhaps, but not a team of idiosyncratic individuals, one from each of

the countries invaded by Hitler. The first Blackhawk story is an almost

straight-forward rehearsal of the title character’s origin without much

reference to any of his team.

The splash

page caption under a picture of Blackhawk striding toward us sets the scene:

“History has proven that whenever liberty is smothered and men lie crushed

beneath oppression, there always rises a man to defend the helpless, liberate

the enslaved and crush the tyrant. Such a man is Blackhawk—out of the ruins of

Europe and out of the hopeless mass of defeated people he comes, smashing the

evil before him.”

A

“man” not a “team.” And the story then reveals how a brave Polish pilot swore

to avenge the deaths of his brother and sister by destroying their killer, a

German flying ace named Von Tepp, and how he did exactly that. Virtually by

himself, without the aid of any teammates. The conclusion of the story promises

future adventures as “Blackhawk turns once again to the task destiny has

allotted him.”

The

story is not entirely without reference to a larger freelance military

enterprise. A caption mid-way through the story re-introduces the Polish flyer

who has now become Blackhawk and refers to “his men” who “swoop down out of

nowhere, their guns belching death and on their lips the dreaded song of the

Blackhawks.”

Seemingly,

a pretty detailed glimpse of the outfit we remember. But the team members are

not introduced in any formal way. They may exist, but they don’t exist as

individuals; they exist as a unit.

And,

more significantly, the caption itself, stretching across the width of the

page, takes an irregular shape to accommodate, I suspect, a late addition of

text—namely, the portion of the caption that I’ve just quoted, the part about

Blackhawk’s men and their battle hymn. My guess is that this part of the

caption was added after the artwork for the story had been completed—after

Arnold had seen the Death Patrol story and issued his demand for another

feature like it.

Until

then, I suspect Blackhawk was envisioned as a lone wolf, a knight errant of the

air, acting more-or-less single-handedly to right Nazi wrongs. Once the idea of

the Blackhawk team surfaced, the origin story was tinkered with to foreshadow

their introduction in the second issue of Military Comics. That

formality had to wait until then because the introductory tale of Blackhawk’s

origin had already been completed, and the artwork for the first issue of the

comic book was teetering on the doorstep, on the way out to the printer. There

wasn’t time, just then, to do anything drastic to incorporate Arnold’s dictum.

In

that first story, Blackhawk returns to an island stronghold, but this aspect of

the character’s legend could have existed quite independent of the team idea.

An aerial view of the island locates barracks, indicating that the island

(called “Blackhawk’s Island,” using a singular possessive, not “Blackhawk

Island” as it will be known later) is home base for more than a single fighter

pilot. But an airborne militia need not be a team of individual personalities,

which is what, eventually, distinguished the Blackhawk mythos.

We

hear a chorus of the Blackhawk song and we see Blackhawk’s squadron in action

in the first story, but the action is fairly passive. A couple of them have

been captured by Von Tepp, who lines them up before a firing squad. And then

Blackhawk shows up to rescue them—assisted by his black-uniformed cohorts, who

perch on the walls of Von Tepp’s mountaintop stronghold, surrounding the

hapless Nazi, “like blackbirds of prey.” A neat turn of phrase. But none of the

squadron does anything in particular. All the action is left to their leader.

Blackhawk

takes Von Tepp prisoner and returns to his island. There, he challenges the

German to a duel in the sky and eventually, in a three-page climactic battle,

defeats his nemesis. In short, the emphasis of the story is on Blackhawk, the

solo soldier of wartime fortune.

It

is entirely possible that the first Blackhawk story was written with the

Blackhawk team firmly in mind but only hinted at, as we’ve seen, in the final

product. But if that were the case, I’d expect to find, as we usually do in

similar cases throughout comics history, a more expansive reference to the team

in the inaugural tale.

Nope;

I believe instead that, as Eisner said during that memorable discussion in San

Diego, the team concept was added to the Blackhawk concept after Arnold saw the Death Patrol artwork. By that time, though, the Blackhawk story

was probably in final, inked and lettered, form, so the concept of a team of

individual pilots, like the Death Patrol gang, had to be suggested rather than

delineated. The suggestions were achieved by insinuating into the completed

artwork a couple of caption extensions and, perhaps, a replacement panel or two

(to introduce the Blackhawk song, say). But the basic story remained pretty

much the same, an origin tale about an aviating Lone Ranger. The elaboration of

the team idea was left to the next issue of the book.

In

the second issue of Military Comics, we meet the Blackhawk team members

on their island. That much of the concept had been conjured up before the first

story went to press, and the caption I mentioned had been added to pave the way

to the future.

The

team members we meet include only three familiar names—Andre the Frenchman,

Stanislaus the Pole, and Olaf the lantern-jawed giant Swede. Others who are

named—Boris, Seg, and Hendrick—soon fade from the scene. And Hendrick becomes

Hendrickson (and sometimes Henderson). We don’t meet the Chinese comic relief

character, Chop-Chop, until the third story.

Chop-Chop,

like Olaf, was inspired, Cuidera said, by Milton Caniff’s characters in Terry and the Pirates, the voluble cook Connie and the mute Big Stoop.

“Everyone stole from Milton Caniff back then,” Cuidera said. Chuck, the

American representative, doesn’t show up until No. 11. Since this is Cuidera’s

last pre-war story, I’d say the Blackhawk Chuck was introduced so that the

artist Chuck would remain with his creation by proxy even while away in the

Army.

Stanislaus

was reportedly named after Powell, whose given names were Stanley (for

Stanislaus) Robert. Of Polish descent himself, Powell also lent his national

origin to the title character. Later, this aspect of the character was blurred

and forgotten, and Blackhawk became an American.

Quite

apart from the history lesson afforded by Blackhawk Archives, Vol. 1, we

find a generous dose of Reed Crandall as he crested in artistic virtuosity.

In

Volume 2 of his History of Comics, Jim Steranko says without

qualification that “Crandall unquestionably was the finest artistic talent to

emerge from the world of comic illustration in the forties.” Certainly Crandall

ranks with Lou Fine and Creig Flessell as one of the best, all-around artists

of the period. And Crandall worked in comics longer than Fine and more steadily

than Flessell and supplied, thereby, a more accessible model for other artists

to study and imitate. (If they could.)

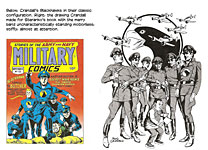

These

days, we veer off into rhapsodies about Crandall’s work for EC Comics in the

1950s and for Warren in the 1960s. And in these efforts, Crandall was

undeniably masterful. But his line had become brittle, his pictures heaped with

hay (cross-hatching and shading), his figures, comparatively speaking, stiff.

In his earliest Blackhawk work, his line was confident, more fluid and

flexible, his pictures uncluttered, and his figures were supple and sinewy. The

difference is readily apparent in Steranko’s book, which includes the Blackhawk

band as Crandall rendered them in their classic on-rushing configuration on the

cover of Military Comics No. 13 (reportedly Crandall’s first cover) as

well as another

cluster of the gang, standing woodenly, drawn in 1972 expressly for Steranko.

Said

Steranko: “Where Cuidera made Blackhawk a best-seller, Crandall turned it into

a classic, a work of major importance and lasting value.”

Cuidera,

while competent enough with anatomy and facial expression, was better on

equipment and backgrounds. Crandall, however, had mastered the medium in all

its nuances—anatomy, faces, equipage, locales, composition of panels and page

layouts. Cuidera was better than any average you might summon up; but Crandall

was superior in every department. And in DC’s archival Blackhawk, we can

see the difference. It is sometimes subtle (so expert is Cuidera); but it is

there.

With

No. 12, Crandall’s debut on the title, the linework is stronger and the shadows

more numerous and more deftly placed than in Cuidera’s work. And the women,

which crop up now more often, are stunningly beautiful. (Perhaps, in No. 12, due

to Alex Kotsky, who, according to Ron Goulart, did four of the eleven pages.

But beautiful femme fatales continue to appear on Crandall’s pages in Nos. 13,

14, and 17 herein.) Crandall also varied the camera angle more often than

Cuidera—upshots and downshots—all executed for the sake of sheer visual variety

rather than because a scene demanded a different perspective.

And

the search for pictorial diversity sometimes leads to dramatic emphasis. On

page 219 of the DC tome, for instance, in the first panel, a downshot

dramatically implies the fusillade from the aircraft that kills the villains:

shot from above, the picture shows the airplane overhead by means of a

silhouette in shadow, the gunfire with the sprays of sand kicked up by the

rounds, and the death of the bad guys with their contorted postures.

On

the same page, Crandall imparts velocity to a speeding automobile by shooting

up from below and in front, giving to the vehicle the aspect of a soaring

missile. And in the dramatic final panel on the page, he shoots again from

above, from Blackhawk’s perspective, as our hero drops into the fleeing car

from the plane overhead; from that angle, we can see the startled expressions

on the faces of the quarry as they look up to see Blackhawk plummeting towards

them.

But

Crandall’s signal contribution to the Blackhawk books—and the reason he is more

remembered for this title rather than just about any other single series

(except maybe Dollman)—derives from his ability to fill his pictures with

dynamic groupings of figures. Because of his sheer love of drawing and his

surpassing skill at it, he put more of the Blackhawks into more panels than

Cuidera did. Under Crandall’s hand, the stories were clearly, vividly, about a

group of men, a team, that dashed headlong through the panels and across the

pages, legs pistoning, fists swinging—an energetic display of all-out

hand-to-hand action that seemed more sport than deadly combat. And it is for this—for

creating the visual ambiance of a fighting group in action—that Crandall’s work

on the Blackhawks is so memorable.

By

the last issue, No. 17, in the Archives volume, every panel brims with

figures. Crandall almost never draws a picture of a single figure. But he is so

skillful in overlapping one figure with another, in foregrounding one and

backgrounding others, that none of the panels seems crowded. Every figure, it

seems, has plenty of elbow-room—even when the picture is filled with machinery

or background detail as well as personnel.

In

the same issue, we see the classic Blackhawk pose: chest out, arms hanging

loosely at his side, fists clenched, legs spread and knees locked back—a vivid

portrait of power poised like a coiled spring, radiating an athletic pride as

well as potency. It was this characteristic pose that Wally Wood so effectively

caricatured in his Mad take-off on the Blackhawks. It was pure Crandall,

Crandall giving Blackhawk his heroic stance.

|

|

By

the time Cuidera returned from military service, the Blackhawks were as much

Crandall’s as his. Crandall had been in the Army Air Corps, too, and, like

Cuidera, he returned to Arnold’s Quality Comics after the war. Crandall did

most of the Blackhawk titles thereafter until Arnold sold his line to DC. By

then, EC was gone, and Crandall was freelancing all around town, at Marvel and

Western. He returned, finally, to his Kansas hometown, where he attended to his

mother until she died and drew classics for Gilberton and other publishers for

a time, submitting his art by mail. His life, and probably his work, what

little he did towards the end, deteriorated, and he died in the fall of 1982

without ever basking in the adoration of his fans at a convention.

Cuidera

did, though. For a couple of years anyhow. People came by Chuck’s spot at the

table just down the row from mine in Artists Alley his last summer. Dave

Siegel, several times. And they smiled and told him they loved his Blackhawk.

His and Reed Crandall’s.

Return to Harv's Hindsights |