BAM! WOW! COMIC BOOKS AREN’T JUST FOR KIDS ANYMORE

Fifty—sixty, even seventy—years ago, this headline screamed across the tops of newspaper pages every once in a while, announcing what the writer perceived as another advance in civilization. Comicbooks were Art. They were Literature. Every few years, the same headline appeared again. And again a few years after that.

Every generation, it seemed, had to discover this new truth for itself.

And so it is without any sense of fresh discovery that I put that headline at the top of this essay, which attempts to prove, once again, that comicbooks aren’t just for kids anymore.

They’re also for adults. And for art students. And for students of literature.

And that’s because comicbooks are Art. They are Literature. They aren’t just garishly colored pictures in rows inside magazine-like publications.

What are the signs of this newly emerging medium?

Perhaps the most obvious—the artwork.

The artwork is better.

That came about as publishers let lapse their requirement that a “house style” be adopted by every artist drawing comicbooks for that publisher. When artists could draw in their own unique manner, they drew better because they could be identified by their work. And when they were allowed to sign their work, that increased the impulse to do good work.

EC Comics could have started the latter trend in the 1950s—letting artists sign their work. We all knew the EC artists—Jack Davis, Wallace Wood, Will Elder, Graham “Ghastly” Ingels, Harvey Kurtzman, Johnny Craig, Jack Kamen, Joe Orlando, and B. Krigstein. And their styles were distinctive, each to his own manner.

But EC died too soon, and with its death, so too the tendency towards identifying artists faded for a time.

But it returned. And with it, improvement in the quality of the art—because the artists signed their work.

And as the quality of the art improved, the comicbook medium began attracting artists who would not, earlier, have worked in comics. But now they did because they could do their best work in the medium.

They also began working in comics because there was no other outlet for illustrators in American popular culture. The big general interest magazines of yore— Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s—which had published romantic fiction that required illustration had died off by the mid-sixties. Nothing left for the illustrator but comicbooks.

And

so we find in comicbooks artists like Neal Addams, George Perez, Jim Steranko,

Frank Miller, Art Spiegelman, Frank Thorne, Los Bros Hernandez, Dave Gibbons,

and, later, Greg Smallwood, Eduardo Risso, Phil Hester, Mike Mignola. Some of

them— Risso for example— producing uniquely rendered illustration (Risso’s

distinctively shadowed pages).

Apart from improved artwork, another thing that happened matured the comicbook. The kind of story being published has changed. Superheroes in colorful longjohns are still found in comics, but the kind of story they act in has changed. Thanks, mostly, to Marvel for giving its superheroes “personalities,” the superheroes have personal problems, crises, that need attending to. And Frank Miller’s treatment of Batman in 1986 enhanced the tendency, virtually setting a new grim fashion for superheroic adventures. The emergence of underground comix that told stories no one previously would touch also influenced the content of comics.

Comicbooks are no longer simply display cases for figure-drawing, for depicting human musculature in tights.

Comicbooks would probably not have survived in the 1930s and through the 1940s were it not for superheroes. Without Superman coming out every month in an increasing number of titles—without Captain Marvel, ditto—comicbooks probably wouldn’t have lasted.

Serial publication established the form. But once the form is established, what can you do with it?

The adolescent readers to whom comicbooks were aimed at first were perfectly happy with superhero stories. But as those readers grew up and went to college, some of them continued to buy and read comics —increasingly in the 1960s and 1970s— and they needed something more than superheroics in star-spangled tights.

A few comicbook publishers tried to hold onto those maturer readers with nostalgic appeals. They revived those readers’ superheroes for new adventures—Fawcett’s Captain Marvel of yore, for instance. And DC also tried to bring Plastic Man to life again.

But that gesture was not enough to hold older readers. It wasn’t enough to hold writers either.

SOME OF THOSE who began writing comics in the seventies saw comicbook writing as training for writing in a more sophisticated medium, motion pictures. (And in fact, inceasingly over the years, movies were “storyboarded” before the cameras rolled; and storyboards were, in effect, comics.) Writers aspiring to greater things wanted to explore more complicated themes than the superhero genre would support. The limited run series was introduced: in a predetermined number of issues, a given title would examine a theme other than crime-fighting. And the stories had beginnings, middles, and ends. They ended! That focused attention on content in a new way.

As more accomplished illustrators started doing comicbooks, the stories were told differently. In early comicbooks, the stories were told with words, mostly—words written as captions that the pictures above the captions illustrated. As the twentieth century closed, many comicbook stories were exploiting the visual aspect of the medium: artists and writers told stories visually—the information contained in the pictures became aspects of the narrative, their imagery and sequencing often told parts of the stories without words at all. Page layout and narrative breakdown into panels became more integral to storytelling.

The last step (for now) was the graphic novel. At first just several issues of a comicbook title bound together between hard covers, graphic novels pretty quickly became long stories written expressly for book publication. And with that, the themes started multiplying.

In their latest manifestation, graphic novels adapted serious verbal literature to the visual-verbal medium. Tasia Bass in mentalfloss.com recently offered a list of eleven adaptations, to wit—:

1. A Wrinkle In Time by Madeleine L'Engle and Hope Larson; $13

2. The Odyssey by Homer and Gareth Hinds; $15

3. Jane by Charlotte Brontë, Aline Brosh McKenna, and Ramón K. Pérez; $25

4. To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee and Fred Fordham; $18

5. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Key Fitzgerald, Fred Fordham, and Aya Morton; $17

6. Anne Frank's Diary by Anne Frank, Ari Folman and David Polonsky; $16

7. Animal Farm by George Orwell and Odyr; $13

8. Marvel Classics by Various; $92

Around a dozen classic tales, all written and illustrated by some of Marvel's best talent from the '70s, like Uncanny X-Men visionary Chris Claremont, then Doug Moench, and Bill Mantlo. The stories here are all reprints from Marvel Classics Comics, an ongoing series dedicated to combining timeless literature with the company's flashy comic book style. You'll find pop-art interpretations of The War of the Worlds, Ivanhoe, Treasure Island, The Odyssey, A Christmas Carol, and more.

9. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley and Gris Grimly; $18

10. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, Laurence Sach, and Rajesh Nagulakonda; $17

11. The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Dixon, and David Wenzel; $17

To which I can add a couple more — Heart of Darkness, Animal Farm (the pictures are all paintings), and Slaughterhouse-Five. The Great Gatsby has at least two more adaptations than Bass lists. Even John Milton’s great Paradise Lost has a graphic novel version. And these additions to Bass’s list by no means completely count a rapidly increasing number.

The graphic novel format is also used to examine various aspects of the human condition— Queer As All Get Out, Gender Queer, The Times I Knew I Was Gay, Menopause, and About Betty’s Boobs (breast cancer; all pictures, no words).

Adapting existing literary works to the visual-verbal medium is not usually very successful. The Great Gatsby was created as a prose novel—as a verbal narrative with a first person narrator—for a reason. The Gatsby graphic novel adaptations I’ve seen do not convey the aspiring aspect of Nick Carroway’s personality as well as prose does. The graphic novel “story” is not the same as the novel “story.”

And Paradise Lost is poetry. Poetry is the special venue of language with words deployed for sound and tone as well as meaning. Graphic novels can’t do justice to poetry. They cannot even approach poetry.

Not poetry in the usual sense of the term. But poetry in another sense is doubtless possible: blending words and pictures in comics fashion can achieve its own kind of poetic aura. Examining that phenomenon, however, is not our task at the moment.

SHEDDING SOME LIGHT on that task is The Adoption, a graphic novel by Zidrou, drawn by Arno Monin (144 8.5x11-inch pages, color; 2020 Magnetic Press hardcover, $24.99). This is an exquisitely rendered story about love—love dormant and love awakened. At its center is Gabriel, an elderly, grandfatherly-looking man with a white beard and only a few hairs on his head. His quiet retired life is suddenly disrupted when his son Alain and daughter-in-law Lynette adopt a four-year-old orphan girl, a survivor of a horrendous earthquake in Peru.

Gabriel does not approve of the adoption: he thinks Alain is too old at 47 to have his first child. Everyone else in the circle of family and friends is delighted with the little girl named Qinaya. But Gabriel holds off; his life with his family was never much because he worked all the time and was away from home at his butcher shop (where he was famous for his delicious pate).

Still, he observes the child’s cuteness. And by page 50, he’s not only accepted her: he does so affectionately.

Then during party one evening, the police arrive and arrest Alain and Lynette—for kidnaping! It seems that in adopting Qinaya, they overlooked certain irregularities in the adoption procedure, and what they ended up doing was illegal. Alain takes the blame and the rap, three years in prison.

And Qinaya is taken by a social worker and returned to her still living parents in Peru.

Then Gabriel hires a detective in Lima to find Qinaya and to guide him to her.

Once in Lima, Gabriel finds himself in a little room waiting for Qinaya to appear; in the room with him is another older man who speaks no English. When Qinaya shows up, she runs toward the two of them, shouting “achachi,” which means “grandfather.” She runs into the arms of the other man.

For the moment, Gabriel wants to return home. Unfortunately, he can’t: all the air traffic in the right direction is fully booked so he can’t change his flight to leave earlier. But a man named Marco has heard him discussing his plight with the ticket agent. Marco wants to stay in Peru longer than his ticket permits, so he offers to trade with Gabriel.

Gabriel has a couple days to wait for his new departing flight, so he and Marco go sight-seeing together. Marco is in town to find his daughter’s body; she was killed in the earthquake. Talking together one evening, they tell each other’s family histories. Gabriel, answering Marco’s question, says he doesn’t have a son.

Later, however, he confesses that he does have a son, who’s now in jail.

Gabriel realizes, finally, that he’s in the wrong country.

“A child does need me,” he says. “But not here. Not in Peru.”

He’s thinking of Alain, in jail. He leaves Peru and returns home.

Then he visits Alain, somehow getting permission to use the jailhouse kitchen, where he makes his famous pate and, later, shares it with Alain in the prison cafeteria. The book ends with the visit, a long, six-page silent sequence, ending with the two exchanging only a couple words.

And then, as they sit there, in the cafeteria, we see Qinaya, sitting on her trike and watching them. She’s a hallucination, of course. But her presence on the page as the adopted —and accepted!—child runs parallel to Gabriel’s final acceptance—adoption—of his own son, whom he had disowned.

It’s a nicely complex narrative. The parallels emphasize the book’s theme of love, but the impact of the final sequence with Qinaya an echo of Alain, or vice versa, is achieved only through our gradual acquaintance with Gabriel, who moves from a cold, withholding emotionally isolated personality to genuine loving fatherhood. The child had awakened in him paternal feelings that he had suppressed all his life. And he has adopted a warmer, loving personality.

With that adoption, as we see in the book’s final pages, life is better.

With that adoption, as we see in the book’s final pages, life is better.

Monin’s visual storytelling is adept, and his drawings are exquisite. The style in renderingpeople is not quite photographic realism. It’s cartoony but not bigfoot. However his detailed rendering of backgrounds and locales is about as photographic as simple linework can achieve. He’s a delight to watch.

The Adoption is about humanity, the things that bind us together. And with the silent panels that end the story in the prison cafeteria, Monin and Zidrou give pictures the final say in their novel.

WE FIND ANOTHER ASPECT of mature storytelling in the comicbook That Texas Blood. In the first issue we meet the sheriff of Ambrose County, Joe Bob Coates, who we encounter as he awakens next to his wife on the morning of his seventieth birthday. His wife, Martha, tells him he must get from her sister Ruth a casserole dish that she needs in order to fix his birthday dinner.

Chris Condon and Jacob Phillips have contrived to make this issue all about tone. The tone is mundane, everyday, a little downbeat.

We watch as Joe Bob goes through his day, every episode of it a low-key tonal exercise. He’s called to kill a rattlesnake on someone’s front porch. He stops at Ruth’s house to get the casserole, but she won’t come to the door. She says she’s feeling poorly, but Joe surmises that she’s probably just been beaten by her husband, Ray, and doesn’t want him to see the bruises or black eye. But her story is that she can’t give him the casserole yet because she must wash it first. She says she’ll send it later; Ray will take it to Martha.

Joe Bob, agreeing to the plan, says, “Well.” He says “well” a lot in this story. The minimal discourse defines him.

Joe Bob stops at a candy store and deliberates before buying snacks—beef jerky

and dried fruit. The episode reveals something of Joe Bob’s character and it

maintains the issue’s quiet mundane tone. Driving a little outside of town, Joe Bob marvels at a beautiful

red Texas sky over the buttes. Then he sees his brother-in-law Ray speeding by

him. He follows Ray and stops him. When he approaches Ray’s side of the car,

Joe Bob sees that Ray has a pistol. Ray puts it under his chin and shoots.

Driving a little outside of town, Joe Bob marvels at a beautiful

red Texas sky over the buttes. Then he sees his brother-in-law Ray speeding by

him. He follows Ray and stops him. When he approaches Ray’s side of the car,

Joe Bob sees that Ray has a pistol. Ray puts it under his chin and shoots.

Joe Bob, splattered somewhat with Ray’s blood, sees a covered dish on the seat beside Ray. It’s also blood-splattered.

|

|

We don’t find out in this issue why Ray killed himself. But we find something else.

“Well,” says Joe Bob, “I found the casserole dish.”

The concluding narrative is mostly pictures, which gives every sequence the same sort of mundane plodding tone that has prevailed throughout Joe’s day, episode after episode. We learn that Joe is a methodical sort of fellow.

Each episode is like the tick of a clock—methodical, slow-moving. Narrative breakdown sets the pace: one mundane step at a time. The pictures are detailed, every visual aspect rendered in a painstaking realistic manner. Normally, I don’t like such detailed treatment, but here, it’s crisply, beautifully done, and the realism underscores the tone.

Subsequent issues of the book are about crimes committed and culprits apprehended. But Joe Bob’s quiet, unruffled manner lurks throughout. He never rushes into anything; and he’s usually successful in solving crimes and enforcing the law. This title is about personality, character, another of the mature themes comicbooks often traffic in these days.

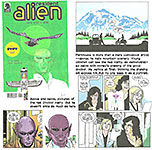

EVEN SCIENCE FICTION has something beneficial to say about the human condition. I say “even,” but almost all sf reveals something about the human condition—sometimes, something we don’t want to hear. The best sf I’ve been reading lately is Resident Alien, written by Pete Hogan and drawn by Steve Parkhouse. We’re up to the sixth graphic novel of this title, and there’s a syfy tv series based upon the characters and the circumstance that’s into its second season. Resident Alien might be with us for a while.

The stories center on Harry Vanderspeigle, the doctor in a small town named Patience in backwoods Washington state. What nobody in town realizes is that Harry is actually from another planet: he got stranded on Earth when his spacecraft crashed while he was reconnoitering the planet on a mission for his government. Now, he’s stuck; he hopes his government will send a rescue team through space. But he’s not sure it will ever actually arrive.

In the meantime, he must avoid revealing to humans his real identity as a freakish-looking creature—as an alien from another planet. To keep himself sane while awaiting rescue, he works as the town doctor, which he is able to do because creatures of his native planet are many times as intelligent as humans, so he can teach himself human anatomy and medicine in a matter of hours.

Harry also indulges a fascination for criminal puzzles, helping the local police solve crimes. He’s good at it because he knows what people are thinking—another alien trait. If someone lies to him, he knows it immediately.

His career as an amateur detective began with the first issue of the title. The previous town doctor is found murdered in his clinic. The sheriff of Patience needed a doctor to examine the corpse, and he knew the man who lived in a lakeside cabin some distance outside town was a doctor. That’s Harry. So the sheriff asked Harry to perform the autopsy.

Harry did. And then he was inveigled into taking the town doctor job—“temporarily” until a new permanent replacement for the old doctor could be found. Alas, it appears, now—after six issues of the title—that Harry is stuck as the town doctor.

Hogan manages to introduce into this ordinary circumstance some chances for threatening complications.

First,

Harry the alien doesn’t look at all like any human. He has huge dark eyes, gray

skin, large pointy ears, and his hands have only three fingers. But he

nonetheless moves through human society easily. He has the ability to mask his

appearance so he looks like everyone else; the wrinkle— only one or two

in a million humans can see the real Harry through his disguise. Unhappily for

Harry, several of those exceptional beings live in Patience. One is a small

child, who, as she grows older, loses the ability to see the authentic Harry.

Two others, however, are adults; they are Native Americans and because of that

are able to see the real Harry.

And Harry can be photographed with a normal camera.

One of the Native Americans is Asta Twelvetrees, who works as a nurse in the town clinic. She gets to know Harry in their workplace. She doesn’t actually see the authentic Harry: but she doesn’t see the face he’s put on as a disguise either. All she sees is a blur where Harry’s face is. Her father, on the other hand, sees the real Harry. He has no reason to disclose Harry’s identity, and the two become friends.

The other complication hovering over the adventures Harry is having is the FBI. They know a mysterious space craft has landed on Earth somewhere in western United States. And they trying to find it. They also suspect an alien pilot left his space craft and is wandering Earth. They want to find him/it. Somehow, they have acquired a photograph with Harry in it, and the photo reveals him in his real appearance. He is talking to a young woman, and they think if they can identify her, they can locate Harry. The woman is Asta, and she’s wearing a jacket of distinctive Indian designs which the FBI now tries to find.

Every issue of Resident Alien brings in some aspect of the things that threaten Harry. Someone “seeing” him. The FBI getting another clue. But each issue is otherwise devoted to the mystery that the local sheriff asks him to help solve.

After finding the murderer of the erstwhile town doctor, Harry solves the mystery of a blonde’s suicide and of the authorship of a favorite series of novels. He goes to New York City to find a missing painter and, later, explains the death of an old man who wanders into Patience.

Parkhouse’s pictures are fun to watch. His line is nearly unvarying in width, resulting in pictures that are sharp-edged and crisp. The line would be delicate were it not deployed with such confidence and determination. He can draw anything, and people in any conceivable position or pose. He particularly enjoys drawing rugged older characters like the sheriff or the mayor, with whom Harry spends a good deal of his time.

Lots of pages are parades of talking heads—mysteries to be explained, motives to be explored, and so on. So Parkhouse is expert at visual storytelling, changing perspective or camera angle from panel to panel, producing with visual effects the appearance of visual energy.

|

|

The longer the mysteries last, the more time Harry and Asta spend together. And that raises all sorts of questions of inter-species romance. Beyond that, however, are insights into the nature of relationships between beings—an issue that surfaces bluntly at the end of the sixth Resident Alien graphic novel.

The sixth series of “chapters” is entitled “Your Ride’s Here.” In the sixth issue of that series, Harry’s rescue team arrives from his home planet. But after several pages of discussion, Harry tells his rescuers that he won’t be coming with them.

They take off in their flying saucer as Harry watches, saying: “It’s over. And I’m free now. I’m not being hunted anymore.”

Asta wants to know why he doesn’t go with his rescuers “back home.”

“Because I don’t fit there,” he says.

Acknowledging that he doesn’t “fit” on Earth either, he refers to “all the friends” he’s made on Earth, the work he does, the lives he’s touched.

“It’s all a part of me now,” he goes on, “—and I couldn’t give it up.”

Then Asta says she wants to have “a talk” with him. She admits to not knowing what they’re doing, the two of them, but she also says she wants to know him better.

“It’s just ... could we take things slowly?” she says. “Just see how it goes?”

“Of courses,” Harry says. “I’d like that.”

And the last half-page panel in the issue—at night, against a rising moon— shows them walking off, hand-in-hand.

“Not really the end,” a closing caption tells us.

In the next issues, we will presumably find out something about the nature of love. Is it an exclusively human condition? Or are other species afflicted with it too?

Ponderable questions provoking mature thought. Not the usual stuff of comicbooks.

HARRY’S ROLE in the syfy series of television’s “Resident Alien” is taken by Alan Tudyk, who, with a flair for comedy, plays the part with a telltale smirk. He is particularly adept at the part of an alien from outer space. His facial expressions, in variety and subtlety, are wonderful to watch and particularly useful in this version of the story, which goes for chuckles as well as suspense. Tudyk can be remembered for his roles as Tucker McGee in “Tucker & Dale vs. Evil,” Hoban ‘Wash’ Washburne in the space western series “Firefly” and the film “Serenity,” and Steve the Pirate in “Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story.”

AND THEN, there’s Ed Brubaker who, with Sean Phillips drawing for him, tells a decidedly different kind of story. Their stories are noir and gritty, and sometimes brutal but not without feeling. Brubaker calls his books “crime noir.” And they’re certainly “noir” but sometimes the crime part is only on the fringes. Take, for example, Friend of the Devil, the second graphic novel in his series starring Ethan Reckless, a former FBI agent who currently makes a living as a paladin for hire.

When not working a case, Reckless can be found watching old movies in a shuttered movie theater that he owns and lives in, thereby enacting one of Brubaker’s fantasies: “If I could own a movie theater and live out of it and not let anyone else in, I would totally do that.” In Reckless’s case, his living situation “gets to his isolation from the rest of humanity. He’d rather be in a cold theater with just one friend, watching an old movie, than anywhere else.”

While tracing a missing person, Reckless meets and falls in love with Linh Tran, a library clerk, and when he finds out she has a lost sister, Maggie, who vanished into Hollywood fleshpots years before, he agrees to help find her. When he sees Maggie in the background of a crummy exploitation flick, Reckless starts “pulling at the tangled threads of a seedy operation,” as Publishers Weekly puts it, “and unravels a seedy tale” of low-budget sex films, and in one of them about a sex-suicide cult, he sees Maggie being killed on film as part of the story. He tells Linh, and she watches, horrified, the movie of her sister’s death.

This is clearly not the sort of thing that the old timey Comics Code would have approved.

Destroy All Monsters is the next in the Reckless series. In this tale, Reckless is hired by Isaac Presley to avenge his father by ruining Gerald Runyan, a man who ruined Isaac’s father. Midway into the case, Runyan is exposed as a bad guy, and Isaac gets public acclaim for exposing him—all of which leaves Reckless’s revenge operation hanging in mid-air.

But much of this book’s story content is focused in Anna, Reckless’s assistant, a young woman who lives in Reckless’s movie theater. Theirs not a romance: Reckless rescued Anna when she was a teenager, and now she’s in her twenties; Reckless is in his forties. But he objects when Anna has a boyfriend about whom she is apparently serious. This creates a rift between Anna and Reckless.

Anna’s research in the Presley case uncovers Runyan’s evil side, and he comes for her, taking her captive, tying her up in the old movie theater, and setting fire to the building. He has also captured and tied-up Reckless. But Anna frees herself, gets a gun, and shoots Runyan, rescuing Reckless and saving the theater.

Reckless and Anna reconcile, sort of. Reckless restores the old movie theater and gives Anna title to it. And she starts screening for herself old movies.

Again, not a Code-approval candidate. But the maturer preoccupations of comicbook and graphic novel makers these days certainly supports such fictions. And Brubaker’s stories a gripping tales, usually narrated by one of the principals.

Brubaker and Phillips have produced together a couple dozen books of the noir kind. At first, they were published serially as comicbooks. Then the comicbooks were bound together to make graphic novels (which they were designed as from the start). Lately, Brubaker has abandoned comicbooks altogether and publishes graphic novels outright.

Said Brubaker: “The switch to graphic novels has been a big hit for us. I personally love having the extra room to let scenes come to life a bit more and being able to play around with structure more. Sean is always trying new things, even new inking techniques, and these books rally give him an expansive canvas to play on.”

Phillips

is a past master of his craft. He fills his panels with telling details and

never shirks on complicated backgrounds. He always shadows his pictures

heavily, and in the most recent titles, his shadowing with a brush has become

more relaxed (you could say “sloppy” but it works just fine).

How these two comicbook creators met and began working together is a mystery to me. Brubaker lives in California, and Phillips lives in England’s Lake District.

Their earlier titles—including Criminal, Incognito, Fatale, and The Fade Out— have been translated around the world to great acclaim (it sez here). The next Reckless book, The Ghost in You, is due in April, and it appears from its cover than Anna will play a significant part in the story.

AND HOW FAR can comicbooks go in whatever new direction occurs to their makers? Take Decorum series for example. Written by Jonathan Hickman and drawn by Mike Huddleston, the books are part text, part diagram, and only a few pages of comicbook storytelling. The text and diagrams and numerous almost blank pages set out to describe life on the Preserves, self-repairing, autonomous terraformed bubbles, over ten thousand of them, most of which died out or were destroyed during the crusades of the Singularity.

After

a text introduction that makes only marginal sense, we get several pages of

comicbook panels that display life on one of the Preserves, but since the

beings depicted are not all humanoid and their speech balloons are filled with

symbols not words, we can scarcely understanding what’s happening here except

that we are being shown life on one of the Preserves.

The book is bigger than most comicbooks—52 pages. Halfway through, we meet a human-looking woman, Neha, who is a courier negotiating with a frog-like being. After four pages, she agrees to deliver the packet, whereupon the book once again descends into high-fallutin’ text and diagram.

The

rest of the book, Chapter Three—all in black-and-white comicbook pages with red

accents— introduces us to a tall, severe-looking woman who speaks in a

convoluted high-fallutin’ argot that reminds me of pretentious academic thesis

writing.  . Named

Imogen Smith-Morley, she is conversing with a man-like being who is awaiting

the packet Neha is bringing. The man, Doman, has committed some sort of sin,

and the Syndicate has sent Imogen to punish (i.e., kill) him.

. Named

Imogen Smith-Morley, she is conversing with a man-like being who is awaiting

the packet Neha is bringing. The man, Doman, has committed some sort of sin,

and the Syndicate has sent Imogen to punish (i.e., kill) him.

When

Neha arrives, Imogen opens the package and removes a large red sort-of gem,

which is a weapon that Imogen uses to wipe out Doman and his henchmen in two

pages of bloodless killing.

Then Imogen turns to Neha and says, “What are we going to do with you?”

The book then ends with three blank pages, the bottom of the last inscribed “Next Issue.”

This is undoubtedly the strangest comicbook I’ve ever beheld.

The only sequences in the book that are complete and comprehensible are those introducing Neha and then, later, Imogen on her punishing errand. Neha emerges as a thoroughly likeable human with a determined inclination. Imogen proves to be effective despite the lofty pretension of her lingo.

We want to know what will become of Neha now that Imogen has turned her unforgiving eyes upon her. But whether all the off-world trappings of blank pages and diagrams and text explanations are essential to our enjoyment is a matter of personal taste. And mine is convinced that all those pages herein are a waste.

But I applaud the complex effort to create with pictures, diagrams, and text a scientific-looking world through which to romp with a story. A noble effort and, as far as I can tell, a successful one albeit one I can’t quite figure out.

UNTIL DECORUM, the most impressive performance in the medium was Jason Lutes’ 600-page graphic novel, Berlin. Even after Decorum, Berlin is the most impressive performance in the medium. But while Decorum plays with the nature of the medium, Berlin exploits its traditional function. It does so at a massive scale, and the achievement is equally massive.

And

so is the actual book, which is gigantic enough without reading a word of it

except the words on the cover. It’s not exactly a door-stopper of a book; with

pages measuring 8x10 inches, it’s not compact enough. But with nearly 600 of

those pages, it comes close.

Berlin, like Decorum, has no central character. Or, rather, it has lots of central characters. Artists, factory workers, policemen, newspapermen, prostitutes, orphans, and cabaret performers—ordinary citizens during a tumultuous time, 1928 to 1933, in the last years of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Adolf Hitler.

At first, the book seems focused on two lives. A young artist, Marthe Muller, who leaves her sheltered life in Cologne to go to Berlin, where she gets involved with the cynical, disillusioned journalist Kurt Severing.

Rob Spillman at guernicamag.com takes up the thread: “She is trying to make her way in the bright lights, studying drawing and, in the rest of her time, the city’s decadent underbelly: jazz clubs and cabarets, open queerness and drug-fueled sex parties thrown by the rich. Severing works for the very real newspaperman Carl von Ossietzky, who was arrested for his reporting on the abuses of the Nazi party, received the Nobel Peace Prize while in prison in 1935, and died a year later under Gestapo supervision. Marthe and Kurt both struggle with their crafts, not believing they are sufficient to match the brute forces ruling the streets.”

But Marthe and Kurt are not the only characters Lutes focuses on. He attends to at least a dozen others, telling fragments of their stories. Almost none of them meet any of the others. So what we have is a collection of individual life fragments.

Says Spillman: “What emerges from all of it is the texture of a moment on the cusp. There are no inevitabilities. There is constant flux and tumult. There are arguments about politics, but also about aesthetics and the use of art, the grotesquery of the realists versus those trying to capture an increasingly rare vision of beauty. And always the futility of words and images against the jackboot and the mob. Marthe and Kurt collaborate to draw and document Berlin’s ordinary citizens, much like Lutes himself, all the while wondering what good it is doing when people are being gunned down in the street. ...

“But, as the Nazis move ever closer to consolidating their power, Marthe and Kurt are not so clear, unsure of how to resist the tide of tyranny. Kurt flirts with the idea of joining the street-fighting Communists, while Marthe considers giving up on her dream of being an artist to return to Cologne, and a quiet domestic life near her family. It was a moment to choose sides, or even to opt out, to flee for the countryside or leave the country altogether. This dilemma— whether to stay and fight for what one believes, but in so doing to face the very real threat of death—is heartbreakingly played out by a Jewish family that takes in a factory worker’s orphan. We know what they do not: Kristallnacht is just around the corner. ...”

Despite the time Lutes has chosen for his graphic novel, we are not conscious of the rise of Nazi Germany in Berlin. We are conscious of the lives of Lutes’ characters. That those lives take place at a pivotal time in a pivotal place seems almost incidental as you are reading the book.

Marthe eventually does return to Cologne. But most of the other characters Lutes abandons. In their brief moments in the narrator’s spotlight, they have served their purpose: they help tell the story of Berlin, a city on the cusp of change.

It took Lutes 22 years to complete the book. “It is an incredible feat of concentration and sustained storytelling,” Spillman says, “— with compelling, complicated characters from beginning to end. Berlin ends with a lack of certainty or conclusion that is nevertheless satisfying. History’s hammer is about to descend, but we know how that story goes. The characters have made their choices. We can imagine how they lived, or didn’t, with their choices.”

Remarkably, Lutes had no plan for his tale. His method is jazz-like. He improvises, following his muse without knowing where it will take him.

In an interview with Zack Smith at newsarama.com, Lutes says: “A lot of it is improvised from panel to panel. That’s a truly jazz-like way of doing comics. ... That’s where comics come alive for me as a writer—I don’t want to know what happens next because that’s what keeps me engaged in the story. I’m curious about what my characters will do. If I knew every single thing that was going to happen, I wouldn’t want to write: it’d become dead.”

Lutes did a spectacular amount of research, delving into the history of the period and the place.

“But the goal is not to retell history,” he says. “The goal is to retell human experience.”

The extent of Lutes’ research into history is only hinted at in the people’s stories he tells. His research into the appearance of things is evident on every page.

His drawings are meticulously executed. Panels are crammed with telling details. On the pages of Berlin, we are as close to photographic realism as line drawings can come. This kind of drawing proclaims this book a serious tome that must be taken seriously. Berlin, in effect, is the announcement that comics are both literature and art.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lutes is already at work on his next graphic novel. This one, entitled Arizona 1865, is set in the American West. In his 2018 interview with Smith, Lutes said he’s completed most of the research and has outlined 3/4 of the story. And he’d drawn the first page of the story.

“I’m drawing smaller,” he said, “I’m drawing simpler. I want it to be in color, [so] the drawing style is going to be different from what I used in Berlin.”

I can’t wait to see it.

HOWARD CHAYKIN is, without quibble, one of the most imaginative, inventive comicbook producers around. He’s worth a long lingering look any time we consider how far comicbooks have come as art and literature in recent years. But in one of his most recent efforts, his inventiveness runs away with itself and leaves the comicbook a little shy of a full narrative load. In Hey Kids! Comics, Volume II: Prophets & Loss, he returns with a scatological version of comicbook history. This time, happily, he refrains from deploying on every other page as many racial and ethnic slurs as he can think of. But his characters—in their inaugural outing—are as cynical and grasping and self-serving and venal as ever.

We must conclude, from this evidence, that Chaykin is powerfully resentful of the way he was treated in the early days of his career. And he is consequently determined to make those who ran the business then as nasty as possible by way of exacting revenge. Either that or he’s just become a champion cynic.

Set mostly in the 1950s, the first issue begins with the industry’s reactions to the news that a publisher has lost a lawsuit brought by another publisher and has consequently gone out of business— AND various discussions about how to sustain and/or create a readership when television is undermining newsstand sales of comics.

In short, the comics business is in trouble—just as it was in the actual 1950s. And then come the censors, the Fredric Werthams, the would-be death knell for the business. One of the characters herein is a Wertham stand-in. The publishers talk endlessly about how to rescue their business.

Chaykin’s target is the destruction of the comic book industry as brought about by would-be censors who create the Code; the familiar seal even appears on one page. And, judging from the cynicism that pervades Chaykin’s version of the comicbook publishing industry, it deserves to be destroyed.

And there’s no episode that is wholly complete in itself. Instead, we have a series of vignettes. Rather than move through a narrative of cause-and-effect (like most stories), Chaykin piles up incidents from which we are to derive an over-all meaning.

To help us sort through all this, Chaykin has provided a chart on the inside front cover that depicts, names, and describes 21 individual characters—creating the temptation, as we read, to flip back and forth between wherever we’re reading and the inside front cover to identify the speakers we encounter as we go through the book. It’s more like a puzzle than a comicbook. And it’s distracting: it interferes with reading the story.

His

attention to detail is impressive to the point of overwhelming. Even if much of

the detail is achieved through digital effects rather than actual drawing,

attending to those in the kind of detail Chaykin produces is awesome.

Backgrounds, for instance, seem to be linear reproductions of photographs of

scenes.

Alas, he can’t quite produce individually recognizable faces for all his cast (twenty-one!), but in the attempt, he’s admirable.

Alas, we don’t see enough of any single character to rescue the book from being simply a parade of talking heads. There is no central character; hence, no one for us to like or identify with.

If anything here will bring you back to buy the second issue, it’s Chaykin’s razzle-dazzle pages rather than anything in the story or its characters.

Chaykin attends especially to page layouts, but he uses the same layouts over and over: 19 of 28 pages are duplicates of each other. Seven page layouts use two overlapping close-ups to finish each page; 12 pages feature headshots excerpted from the accompanying larger scene.

Both

of these maneuvers deploy close-ups as punchlines, as the rhetorical

“conclusion” of a page’s action. In devising this treatment, Chaykin displays

his inventiveness, which, as I said, is impressive. But the using the same layouts again and

again dilutes their impact, and they eventually bore rather than excite.

But the using the same layouts again and

again dilutes their impact, and they eventually bore rather than excite.

And Chaykin lacks the sheer artistic ability to bring it all off. His anatomy is sometimes stiff and unrealistic, and few of his faces look the same in different poses, a serious deficiency in a book of talking heads.

Despite the failings of this Chaykin title, his determination to try different kinds of maneuvers in storytelling is inspirational. That dedicated inventiveness is another aspect of contemporary comicbook production that makes today’s comics vastly different than yesterday’s.

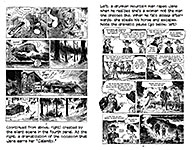

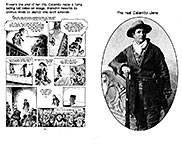

IN THE CATAGORY OF BIOGRAPHY, here’s Calamity Jane: The Calamitous Life of Martha Jane Cannary, 1852-1903 by Christian Perrissin (writer) and Matthieu Blanchin (artist); translated by Diana Schutz and Brandon Kander. This treatment of the life of Calamity Jane could well serve as a model for how the graphic novel form can be deployed as biography. Too many “graphic biographies” are little more than illustrated prose narratives, a series of disconnected pictures under which a text provides the only continuity by reciting events in the subject’s life. But in this book, Perrissin and Blanchin rely upon long stretches of out-and-out comics storytelling—in the best manner of comics, blending words and pictures with pictures carrying the heavier load—to dramatize and highlight episodes in Calamity’s life, resorting to illustrated text only to summarize the life she was probably leading between episodes.

The authors are aided and abetted by the nearly mythical character of Calamity’s actual life, about which very little can be ascertained for certain. We know for certain that she existed, that she usually wore men’s clothes, that she drank and swore and gambled, that she had some sort of relationship with Wild Bill Hickok (but probably not marriage, despite what she stoutly maintained), and that she drifted in and out of Deadwood and other western locales, never settling down anywhere for long. Calamity produced an autobiography, but she was as famous for telling tall tales as she was for swearing and drinking and wearing men’s clothes. Whatever she says about herself is open to question.

Perrissichin

(to portmanteau the authors’ names) begin their tale with illustrated text

describing life in the West at the time Martha Jane Cannary was born and grew

up, 1852-67. Then they create a comics narrative about her life after the death

of her parents, when she wanders alone for the next 40 pages.

We see her on horseback, hunting, camping, muttering to herself—all things anyone can be imagined doing. Many of the comics sequences are like this, picturing the activities of ordinary life, any life, not necessarily Calamity’s. But we know she must’ve done everyday things like those depicted. Such sequences lend substance to the Calamity Jane legend. They flesh out the story Perrissichin is telling, and they are not exactly fiction even though nothing in the recorded life of Calamity tells us she did these things.

Dressed

as a man, she is taken for one. En route to Fort Bridger and Fort Laramie,

Calamity’s horse runs away. Afoot, she finds shelter in a mountain man’s cabin;

drunk, he rapes her when he finally realizes that she’s female. As he sleeps it

off, she steals his horse and escapes.

The

book skips over a few years or months, and the comics narrative resumes when

Calamity meets Hickok and joins him in fighting some outlaws. Later, while she

is staying with Hickok, she reveals her sex by removing her shirt, and ol’ Wild

bill promptly jumps her bones. They stay together in a cabin for some romantic

months, and a itinerant preacher, a friend of Hickok’s, performs a marriage

ceremony for them, uniting them in wedlock. Or so Calamity maintains for the

rest of her life, but any relation she claims with Hickok is a highly dubious

claim.

Calamity works as a rider on the Pony Express and then drifts around Montana and Wyoming, always returning to the Blackhills and Deadwood, where she’s usually drunk and brawling.

She

finishes the rest of her life wandering from town to town, enjoying celebrity

and always drunk. Perrissichin finishes the story with a dream-like sequence in

which an aged Calamity mounts a horse that she imagines is the one that ran off

years ago, and she rides off the page and into history.

Most of Calamity’s story is produced in the comics form, sequences of blended pictures and words. Blanchin deploys a lively pen to render events in a sketchy manner, sometimes so sketchy that we can’t tell one character from another. Calamity in particular appears different on almost every other page. But this breezy manner is perfectly suited to depicting action sequences in which the figures sometimes move rapidly with a cartoony feel. And when he draws scenery, the wash he habitually uses enhances the scenic effect wonderfully. It’s a treat to watch the story unfold at his hands.

ROUGHNECK is fictional biography by Jeff Lemire, but it focuses on only a small part of the title character’s life, and Lemire makes the best use of the medium. Derek Ouelette was forced out of a promising hockey career because he was too violent; he now whiles away his time in a remote Canadian community, drinking too much and fighting anyone who ruffles his feathers. He works as a cook in a fast-food diner and lives in the janitor’s locker room at the local rink. Then his little sister, Beth, shows up with a black eye.

Derek had left her behind and homeless more than ten years ago to pursue his career on the ice. She’s run away from an abusive boyfriend named Wade. And, it turns out, she’s a junkie. Derek goes after the thugs who sold her the oxycontin and beats them up, nearly killing them. He’s a tough cookie with his fists.

Derek takes Beth to an isolated cabin in the woods where she can get clean. She tells Derek she’s pregnant. He stays with her, encourages her to kick the habit and to decide whether to have the baby. She gets better, no longer craves oxy. The two become closer although the increasing mutual affection is conveyed more in pictures than in words.

Then Derek finds out Wade has come to town to get Beth. Derek wants to go after him, to punish him as he did the oxy-sellers; Beth pleads with him not to. But he goes tearing off to find Wade. Beth begs their cop friend Ray to take her into town after Derek: “He’s going to kill Wade,” she says.

In town, Derek finds Wade and picks a fight with him, but when Wade attacks, Derek doesn’t fight back. Wade pounds him repeatedly and knocks him down. Beth arrives and kneels next to Derek, prone on the ground and bleeding.

“Derek,” she says, “—what did you do?”

“I let it go, Bethy,” he says. And then dies.

The book jacket flap says this is the “story of family, heritage, and the desire to break the cycle of violence at any cost.”

Family and heritage, yes. But it’s not all that evident that Derek wants to break the cycle of violence “at any cost.” Beth, yes; but not Derek. He may be thinking about giving up his thug life, but he never says anything about it until he does it. Then dies.

We watch, however, as he assumes the role of care-giver to Beth, becoming thoughtful and kind. So when he says “I let it go,” it isn’t entirely a surprise. The sense of family has asserted itself with him.

Lemire’s storytelling is very cinematic. Dialogue is minimal, and the narrative is frequently carried by the pictures alone, pages of the silent images. Lemire moves his story forward, slowly, the pictures closing in for close-ups, then dropping back, increasing the distance by degrees, panel after panel. Derek is often pictured alone, outside, smoking by himself with picturesque forest wilderness as a backdrop. Lots of silent close-ups of faces as the characters think and ponder their situation.

Lemire’s drawing style is crude here, intentionally rough; the raw linework is almost sketchy but too bold for that. The narrative is told with black lines, tinted blue with a wash. Except when Lemire lets his characters remember something; then the pictures are in color.

Lemire is clearly conscious of the medium’s capabilities, and he exploits them deftly.

|

|

|

A dog serves as a thematic device in the book. After Derek’s victorious brawl in a bar, he goes outside and urinates, and a dog shows up, panting and wagging its tail. Derek says, “What are you looking at?” And the dog goes away.

The dog shows up again when Derek and Beth move to the cabin in the woods. Again, Derek scowls at the creature, and it runs off.

The dog reappears when Derek is thinking about how he almost killed (or perhaps did) that hockey-player from an opposing team. And when Beth remembers how her mother died in an auto accident, a dog appears, licking the blood that drips from her mother’s body in the wreck. And when Derek goes after Wade, he’s accompanied by a barking dog.

Derek’s death, lying on the ground, is followed by facing pages of solid black.

Then there’s a silent sequence of 8 pages. A couple panels show Beth being taken somewhere by a friend, Al; she’s shown holding her pregnant belly, so we assume they’re going to the hospital. Several panels show Derek walking alone. Then he comes upon a dog. This time, he kneels and beckons the dog, which comes up to him and licks his face.

The last page in the book shows Derek walking into the woods, followed by the dog. The picture is partly colored.

The subtlety of the closing sequence would never have been attempted in the comicbooks of yore. But nowadays, it is not wholly unexpected.

TODAY’S COMICBOOK is a far cry from the infant form of the 1930s through the 1950s. The books are written and drawn by serious artists, intent on producing works that expand the potential for the artform both thematically and pictorially.

In our brief tour of recent efforts we can see a growing maturity. The range of topics, the breadth of themes, help to mature the medium. And with maturity comes artistic aspiration and achievement. Now a literary art as well as a visual one, comicbooks justify serious analytical attention. And they’re getting it.