ALLEN BELLMAN

The Last of the Legendary Golden Age

BELLMAN, A COMICS LEGEND and one of the last great Golden Age artists, passed away at the age of 95, announced Chris Perez at cbr.com. Bellman died March 10, 2020.

At Bellman’s website, we learn that he was born in 1924 in Manhattan and studied at the High School of Industrial Arts.

At the Broward Palm Beach New Times website in an article about Bellman, we find his history with comics, which begins the moment Bellman spotted the first Superman comic and fell in love.

"I went to the junior high school in Williamsburg,” Bellman relates. “I was going home for lunch. I had a thin dime in my pocket. I went into Cheap Sam's Candy store — I remember the name — and there was a comic book, Action Comics, and on the cover a guy in blue underwear picking up a car. Now, originally, I was going to buy two candy bars. They were a nickel apiece. Instead, I bought that first issue of Superman."

A few years later, on Columbus Day 1942, Bellman spotted an ad in the New York Times that would mark his own entrance into the comicbook game: the main artist behind Captain America was looking for someone to work on the background imagery. After showing up to the office, Bellman was hired ten minutes later. He was eighteen. And it was Timely Comics (which would morph into Marvel Comics a few years later.)

"Stan Lee was not even there yet,” Bellman said, “— he was in the Army. In a short time, they were giving me my own scripts which I was penciling and inking. The first one I did was called The Patriot.

“I

became a staff artist at Timely during the Golden Age of comics,” Bellman

continued. “While still a teenager, I did the backgrounds for Syd Shores’ Captain

America in 1942, and eventually worked on titles such characters as The

Patriot, The Destroyer, The Human Torch, Jap Buster Johnson and Jet Dixon of

the Space Squadron, plus All Winners Comics, Marvel Mystery, Sub Mariner

Comics, Young Allies and so much more.

“My self-created back-up crime feature was ‘Let’s Play Detective.’ I also contributed to pre-Code horror, crime, war and western tales for Atlas. I worked in the comics field until the early 1950s.”

Churning out classic work hand-in-hand with Marvel chief Stan Lee once Lee returned from military service, Bellman claimed he was instrumental in the genre's golden years.

"I did whatever Stan Lee threw at me. We did war stories, crimes stories, cowboy stories, porn stories — no, just kidding," the wry Bellman said. "He was green, I was green. You fake it till you make it," he explains. "But he made Marvel comics; you have to give him credit. He had showmanship."

Bellman left comics in the mid-1950s. He began drawing for newspapers. After a dozen years or so in New York, he moved to South Florida where he joined the art department of a major daily newspaper, the South Florida Sun-Sentinel.

“After that, I went into photography,” he said. “I won many nationwide photography contests, winning out of more than 20,000 entries. Hundreds of my photos have appeared in hardcover books, have been on exhibit in museums in Florida and received great reviews in numerous newspapers.”

And then, Bellman retired. And then, after a few years of that, he discovered comic-cons.

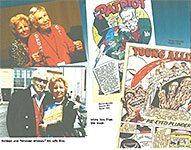

BILLED AT COMIC-CONS AS A COMICS LEGEND and one of the last great Golden Age artists who created Captain America, Bellman enjoyed his legendary status as he made the rounds of comic-cons, hitting 12-15 across the country every year, accompanied by his wife Roz.

How much Captain America work he did is questionable. Jerry Bails and Hames Ware in their watershed 4-volume series, Who’s Who of American Comic Books (1973 - 1976) have Bellman working on Timely/Marvel titles 1943-1946, Human Torch, Patriot; and on Gleason books (1950-51), crime and love. Had Bellman done any great number of Captain America titles, the entry after his name would be somewhat longer. As it is, Captain America isn’t mentioned.

So I developed a suspicion about Bellman’s actual history in the Golden Age.

And “great” is also a likely exaggeration. If he were great, why have we never heard of him before now?

I’m sure he did some work on Captain America. Maybe on one or two issues. Maybe backgrounds or minor characters. (Turns out, this assessment is dead wrong, as we’ll see later.)

Besides, Bellman wasn’t the author of the sobriquet “comics legend and one of the last great Golden Age artists who created Captain America.” It was comic-con organizers who draped that potent title on him.

In any case, once Bellman discovered comic conventions—or they discovered him—he was off and running, the last Captain America artist around. But his appearances at comic cons was more legendary than his work in comics.

At a couple early Denver Comic Cons, he was at a table in Artists “Valley” next to mine. Or, to be precise, his table was across the bottom of a U-shaped arrangement of tables; my table was around the corner of the U from his, but our chairs bumped each other. He posted Captain America pictures on a backboard behind him, and his table was awash with Captain America drawings—prints of sketches. (A “print” in comic-con lingo means a “photocopy” of something.)

|

|

|

I watched a continuous parade of fans go by his table and stop to talk and to take a photo of him. For photos, he assumes what he regarded as an appropriate Captain America pose—growling at the camera with his fists clenched and raised toward the camera in defiance.

I

took the photograph you see posted hereabouts. I also took a picture of the

handle of his cane: it was jaguar hood ornament. And I joked with him about it:

I

took the photograph you see posted hereabouts. I also took a picture of the

handle of his cane: it was jaguar hood ornament. And I joked with him about it:

“If you’re like me,” I said, “that’s as close to owning a jaguar as you’ll ever get.”

We both laughed and then went back to work.

We never talked much. He was too busy. But what little conversation we had, he proved to be genial and not at all as full of himself as his convention headlines imply he might be as the last Golden Age Comicbook creator. In short, he was a nice guy with a memory of great moments in the history of American comicbooks.

THEN, AFTER READING OF HIS DEATH, I ordered and read his autobiography— Timely Confidential: When the Golden Age of Comic Books Was Young. In it, Allen recalls growing up in Brooklyn, and commuting to the McGraw-Hill building (and later the Empire State Building) every morning to work at Timely Comics; friction between different divisions among artists and writers; brushes with celebrities; Martin Goodman's failed expansion into Broadway plays; Bellman’s departure from the comic industry in the 1950s; a second career as a graphic designer and photographer; a move from the New York City area, capital of publishing worldwide, to the Florida tropics; his return to the world of comic book fandom nearly six decades after leaving the field.

The book (2017 Bold Venture Press paperback, $39.95) is fairly slim, and the text is only about half its 166 pages. The rest of the book consists of comicbook stories that Bellman drew (40 pages) and a dozen pages of Bellman bibliography—lists of the stories in Timely/Atlas and Gleason comics that he drew—plus another dozen or so pages of color photographs and reproductions of comicbook story splash pages, which, together with miscellaneous artwork, are also distributed throughout the book. (The publication design is by Rich Harvey, no relation.)

Altogether,

the book is lavishly illustrated, often with rare material. Here’s a photograph

of Lev Gleason; never saw him before. A still from the 1940s “Captain America”

serial. A Gleason Christmas card that depicts the company’s chief comic book

characters surrounded by drawings of the faces of the staff.

An Epilogue is supplied by Mike Broder, an Afterword by Michael Uslan, and a Foreword by a New York dentist named Michael J. Vassallo. It is Vassallo’s research that supplies the bibliography of Bellman’s credits. No easy job: most of his work is unsigned and uncredited. Vassallo identified it by examining drawing style.

Vassallo is responsible for getting Bellman into the comic-con circuit. From another fan, Paul Curtis, Vassallo learned that Bellman, whose work was familiar to him because of all the research he was doing in Golden Age comicbooks, was still alive. Curtis gave Vassallo Bellman’s phone number, and Vassallo called him in early 1999.

“Are you the Allen Bellman who worked at Timely?” Vassallo asked.

“Yes,” said Bellman. “How’d you find me?”

They talked for quite some time, and Vassallo realized that Bellman liked to talk about his days at Timely. In 2001, Vassallo began interviewing Bellman for an Alter Ego article, which was finally published in No.32, January 2004.

The interview brought Bellman to the attention of local Florida comic-con planners, who invited him to the con and gave him a table.

Bellman knew nothing about comic-cons.

“I fell into the whole comic-crazed convention culture,” he said, “—completely unknown to me.”

In 2005, he made an appearance at the Orlando Con at the urging of his old friend Gene Colan.

“I had no clue what the convention scene was all about,” Bellman remembered. “Collectors came by and asked for my autograph and my advice.”

At the first couple cons he attended, all he had to bring to his table were a few copies of the issue of Alter Ego with the interview in it.

“I sold copies and signed them,” he said. “I didn’t even have a drawing pencil. Roz went over to see Gene Colan’s wife Adrienne ... who gave Roz some paper and a pencil, and I started drawing. I did a picture of the Human Torch. A guy came up and said he’d give me $20 for it. I said, ‘Okay’ and started drawing again.”

In mid-2006, Mike Broder was preparing for his first Florida Supercon. Someone told him Bellman lived in South Florida and suggested that Broder invite him to the con.

Broder did.

And when Bellman told him he had once worked for the Sun-Sentinel, Broder reached out to the newspaper, and it ran a big story about Bellman on the Sunday just before the con.

“It served as a giant advertisement for my show,” Broder remembered in Timely Confidential’s Epilogue.

And attendance at the show was far more than Broder had anticipated.

“That newspaper story and that show helped launch Allen back into the world of comicbooks,” said Broder.

After that, Bellman started contacting comic-con promoters, and he and his wife Roz began making the rounds, selling prints and autographing comicbooks.

In 2007, he was a guest at the San Diego Comic-Con and received an Inkpot award.

BELLMAN’S AUTOBIOGRAPHY is scarcely that. The biographical portion is startlingly short—maybe 12-20 pages in the aggregate. And not many dates. Clearly, the book was concocted to capitalize on his comic-con appearances. Apart from the scant biographical passages, the book is a hodge-podge assemblage of anecdotes about his career, the people he knew and worked with, celebrities he met (or didn’t)—exactly the kind of stories he told to fans who stopped by his table at comic-cons.

For example, Bellman reports that Martin Goodman supplied the artists with everything they needed to complete their drawing assignments. But he never came out of his office. “I can never remember him coming out and speaking to the staff—you know, to say, ‘How ya doin’?’ as a boss should do.”

But when Bellman acquired a movie projector and rented porno films to show, “all the guys stood around with me and we watched the porno movies, including Martin Goodman.”

The book is brimming with such anecdotes:

“Arthur Simek came to Timely, designing logos. On his first day, during lunch, he took out a harmonica and played liked a barnyard hayseed.”

And—:

“Never met Lev Gleason, the publisher. Bob Wood was a wonderful guy to work for. He seemed so calm, cool and collected. But one day, I noticed Wood came in with a black eye, and I began to realize he wasn’t exactly who I thought he was. Turned out he was an alcoholic who got into fights over the weekend. But it didn’t seem to affect his work. Bob was the nicest guy in the world to work with.”

Then Wood killed a woman in a hotel room. “He was sentenced, and released a few years later, but he never went back to comics. He got a job as a short order cook in a New Jersey diner. Somehow he got involved with the Mafia, and he was killed.”

Bellman tells us that he once had a chance to do the syndicated comic strip Scorchy Smith. To try out, he had to produce a week’s worth of strips, but he and his first wife got into an argument, and she tore up the work he had finished. He had time to produce only one strip, and he never got the job.

“One morning, during the war years,” Bellman said, “I delivered a story to Stan Lee. He was in his office talking to a young G.I. with a crew cut. Stan said, ‘Allen, I want you to meet Mickey Spillane, and Mickey, I want you to meet Allen Bellman.’

“I shook his hand. He was just another writer. He gave me a story about a character called Jap Buster Johnson.

“After I penciled the story, I inked it.”

He inked with a No.2 Windsor Newton brush that pulled a lot of ink out of the ink bottle, and to get rid of the excess, Bellman says he wiped the brush on the manuscript he had on his table.

“Not knowing that script could be a piece of history,” he said.

He’d defaced a Mickey Spillane manuscript that would have been worth a fortune on the collectors’ market some day.

Bellman is not above trying to find history in his life—close calls, anyhow, and near misses.

Once he drew up a crime story, “Spider of Paris,” from a script he’d been assigned. “It was inspired, I think, by The Spider, a pulp-fiction magazine character. I gave him a top hat, a cape and spats. ... At one point I drew up the word ‘Spiderman,’ like the Superman logo. I didn’t draw a character, but I brought the logo I drew to Stan.

“‘What can we do with this character?’ I asked. At the time, Stan just gave me a condescending smile and walked away.”

Then later—obviously— as Bellman needlessly points out, Spider-Man became famous. “Likely Stan doesn’t even remember the ‘Spiderman’ design I tried.”

But some of Bellman’s anecdotes are virtually meaningless.

He tells about working as a copyboy at the Associated Press as a teenager. He had the midnight-to-9a.m. shift. “During one of those wee morning hours,” he remembers, “I was walking for my ‘lunch’ break at three o’clock in the morning. A woman was passing me and said,’You wanna have a good time?’ Scared the hell outta me. I ran.”

Another one—:

Syd Shores took him to watch the Dodgers play at Ebbets field. Bellman saw a black player and was astonished: major league baseball teams didn’t have African American players. Bellman asked Shores who that was. It was Jackie Robinson. “I had the pleasure and honor of seeing Robinson playing his first year. It’s a wonderful memory.”

A “wonderful memory”? It was “an honor” to see him?

Later in both of their careers, Bellman and Shores shared a studio, each paying half the rent. But their earliest professional association was on Captain America. Shores was the main artist on Captain America through the forties. Bellman drew the backgrounds in Shores’ stories. And he drew other characters, and pages displaying his pictures (pencils and inks) are among the illustrations in the book.

THE BOOK INCLUDES some material that is not present in the Alter Ego interview that Vassallo conducted. And the interview includes things not carried over to the book. The circumstance moves probability to certainty that the book was assembled in an almost haphazard fashion. Even though Vassallo was one of the book’s editors, he failed to include telling anecdotes from the magazine interview he did.

One such tale is about Don Rico, the person who hired Bellman that day in 1942. And Rico was not a popular player.

“Martin Goodman called Don Rico ‘Rat Rico’ because Don and some of the other artists didn’t bother with Syd Shores, who was the unofficial bullpen director. Rico was the ringleader of the ‘ignore Shores’ group. He was always causing small problems in the office, and Goodman knew this, hence the name ‘Rat Rico.’”

In Alter Ego, Bellman tells a story about the send-off the staff gave him when he went into the Navy in 1943.

“They made a sign that said ‘We all agree that you’re the guy to knock the Axis for a loop. The best of luck to you, old pal, from all your friends at the Timely group!’”

If Bellman’s recalling the name of the candy store where he bought his copy of Action Comics No.1 doesn’t demonstrate his phenomenal memory, surely this tale does.

His stint in the Navy was short. He painted insignia in Ships Service, but in a few months, he received an honorable discharge due to illness. He doesn’t say what illness.

He talks about the sexism of the men in the office who made suggestive remarks when a young female staffer came through the bullpen. “This couldn’t happen today in an office,” Bellman notes.

He remembers Vince Alascia, the primary inker of Shores’ Captain America through the forties. “Vince was a very nervous type of guy, and he inked in that manner, in very short strokes.”

And he remembers matters of less significance to comics history. When Timely moved to the Empire State building, Bellman’s drawingboard was next to a window. “I remember seeing a shoe falling down—of a man who committed suicide by jumping out and landing on top of a parked car belonging to a diplomat. The roof of the car was crushed in.

“I remember when the plane hit the Empire State Building on a Saturday when we were off.”

He says it was nice working at Gleason where he went after Timely shut down its staff. “It was smaller at Gleason,” he said. “There were just a few artists on their staff. Bob Wood never really bothered anyone, and Charlie Biro was in and out of the office—mostly ‘out.’ I remember I and the staff, along with our wives, being invited to Wood’s penthouse for a Christmas party.”

Among Bellman’s celebrity citings is Rocky Marciano, the heavyweight prize fighter who became champion by knocking out the current champ, Joe Louis, in October 1951. Bellman met him briefly at a country club then later ran into him on the street in Manhattan. “He was carrying a small gym bag with him, and he recognized me and stopped to talk for about 20 minutes

“I ended up being late for work,” Bellman continued, “—but who cared! I’ll never forget that. He was a kind, soft-spoken person.”

Some of his stories are the same as those in the book. But when he tells of his try at doing Scorchy Smith, he ends the anecdote differently in Alter Ego. In this version, his wife doesn’t tear up his sample strips. They were still living together, but the sourness of their marriage left Bellman feeling alone and helpless. He had no one to share with.

“I did a single daily and I couldn’t go on,” he said.

Once in the Alter Ego interview, Bellman explains why he is doing the interview.

“A lot of things get left out of comics history,” Bellman observes. “That’s why these interviews in Alter Ego are so important. We’re all very old and many of us are gone or will be going soon. Not to be morbid, but I’ve been waiting 50 years to tell my story. I didn’t even know there were magazines that were interested in this stuff. It’s very gratifying to be remembered for what we did so long ago. I want to make my story as accurate as possible.”

But that’s not the whole reason.

He tells about searching second-hand book stores and flea markets in search of some of the comic books he’d drawn so he’d have something to show Roz and her two children (that he’d adopted when they married) who’d never seen any of his work.

“No one could help me,” he reported. “And to make matters worse, no one had even heard of me. It made me almost feel that I never really was a comicbook artist.”

Then he addressed his interviewer, Vassallo:

“You’ve given that all back to me and especially to Roz. It’s given my life and my later years a new fulfillment.”

But even that touching sentiment does not fully explain Bellman’s last years—his last twelve or thirteen years.

“Nowadays, when I’m on a panel, I say, ‘Hello, I’m Allen Bellman and I’m an alcoholic ... Oh, wrong meeting.’ And everybody laughs. I’ve been told I’m a hard act to follow. It makes me feel good about myself, a great thing for a guy who did not have a good image of himself for so many years—especially after I was destroyed by my first bad marriage.”

Bellman’s first marriage, when he was young, ended badly but produced two children. A second marriage, to Roz, in 1962 is still a love match. He calls her Wonder Woman.

“I’m trying to stay kicking as long as I can,” Bellman said. “I look forward to conventions—it’s my lifeline. I get there, and I’m all energized. They all look at me: ‘This old guy is kicking up a storm here.’ I don’t stand still. I talk to everybody. But you’ve gotta have it in you. You can’t force it.”

“I loved drawing,” he went on. “I still do, and comicbook conventions have become my lifeline. I get so energized. One kid looked at a $15 poster and said, ‘I have to think about it.’ I told him, ‘Young man, I don’t have time for you to think about it: I’m 93.”

“To get compliments at this age is wonderful,” he said. “It’s great to be loved and wanted.”

He may not have done more of Syd Shores’ Captain America than the backgrounds; but he did much more with other characters and in other titles. He was scarcely just a background artist.

But even if he exaggerates his role a little, I don’t mind: if I had the chance, I’d do the same. With wild abandon.

|

|

|