THE LIFE AND DEDICATION OF ART YOUNG

An Impassioned Cartoonist of Uncompromising Principle

Newly Revised and Up-dated

ART YOUNG WAS

ONE OF THE MOST PICTURESQUE and highly regarded cartoonists of his generation,

one of the early masters of the medium. Usually forgotten these days, he was,

in his day, the subject of a certain amount of sensational news coverage. And

he can be credited with a couple of historic firsts, too.  But mostly, he was an artist of

principle at a time, the turn of the 19th into the 20th century and immediately thereafter, when cartoonists weren't yet particularly

noted for doing much more than making funny faces.

But mostly, he was an artist of

principle at a time, the turn of the 19th into the 20th century and immediately thereafter, when cartoonists weren't yet particularly

noted for doing much more than making funny faces.

Young was born on January 14, 1866, on a farm near Orangeville, Illinois. The family moved when he was a year old to nearby Monroe, Wisconsin, where his father operated the town's general store on the north side of the village square. It was a gathering place for local politicians and leading citizens, and the youth frequently amused himself by drawing caricatures of them, some of which were displayed in the window of the store and on the wall of the post office.

Passionate about drawing, he saw little value in a formal education and quit school a year before graduating. He clerked in his father's store for awhile, then worked as a photographer's helper, but when he sold a cartoon to Judge magazine in 1883, his career preference was confirmed. That fall, he went to Chicago where he enrolled in the Academy of Design (later merged with the Art Institute).

While attending classes, Young freelanced his humorous drawings to various local publications and was regularly published in the Nimble Nickle, a weekly wholesale grocery house paper, beginning in 1884, and, shortly thereafter, in American Field, a sportsman's magazine. After a year in the city, he started contributing to the Evening Mail, whose editor occasionally sent him out on reportorial assignments. In those days, artists who drew for newspapers often served in the way that photographers do these days: they were assigned to make sketches of the subjects of newsstories (such as murder scenes, trials, disaster scenes, and the like).

In June 1886, Young had his first brush with the kinds of social issues that would later claim his unswerving loyalty. He was sent to cover the trial of the so-called "anarchists" who were accused of setting off a bomb at a labor rally at Haymarket Square in Chicago. It was one of those "political trials": the defendants were convicted more because they were professed anarchists than because they were actually guilty (highly questionable) of exploding a bomb. Young's drawings attracted the attention of Melville E. Stone, editor of the Daily News, who subsequently hired the young cartoonist to work in the paper’s art department. It was Young’s first salaried job.

Young

left Stone's paper in the winter of 1888 to take a better paying position with

the Chicago Tribune but was let go within a few months. (The suspicion

remains that the Tribune had hired him away from Stone in order to put

him out of circulation.) But Young had had enough newspaper cartooning for the

nonce.  Having

saved some money, he went to New York to continue his art education by

enrolling in the Art Students' League, where he heard about art schools in

Paris and Munich. Then in the fall of 1889, he crossed the Atlantic to enter

the Academie Julien in Paris.

Having

saved some money, he went to New York to continue his art education by

enrolling in the Art Students' League, where he heard about art schools in

Paris and Munich. Then in the fall of 1889, he crossed the Atlantic to enter

the Academie Julien in Paris.

Six months later, he was stricken by pleurisy and almost died but for an operation financed by his father, who, never having gone much outside of Monroe, Wisconsin, traveled to Paris to minister his son’s needs. Art returned to Monroe to convalesce, and by the spring of 1891 was well enough to join two friends in producing a traveling show that featured his caricatures of well-known people, which he drew on stage to musical accompaniment.

In early 1892, Young joined the staff of the Chicago Inter Ocean, then one of the city's leading newspapers. He was hired to draw a front-page political cartoon every day; Walt McDougal had been doing a daily cartoon for the New York World since the summer of 1884, but Young was the first in the midwest to do the same.

McDougal, incidentally, was not the first to do a front page editorial cartoon for a daily newspaper, but he was the first to do one regularly, nearly every day. And the way he found himself on the front page of the World makes a fascinating tale, worthy of a digression here, I wont.

BY THE SPRING OF 1884, McDougal was successfully freelancing cartoons to Puck and other comic weeklies, and one day when he was on the way to a ball game, he stopped at the Puck office to see if a cartoon he'd left there had been purchased. It hadn't, so McDougal found himself on the street with a rolled-up cartoon under his arm. He didn't want to take the cartoon with him to the ball game, so on an impulse, he turned into the World building as he walked by it, thinking, momentarily, that the newspaper might buy the cartoon.

"I invaded the dingy dark counting room, found the twenty-two-caliber elevator in the rear— and then my courage oozed away," McDougal wrote years later. "The idea of offering a cartoon to a daily paper seemed to utterly absurd that I thrust the artwork into the hands of the elevator boy and stammered, ‘Give that to the editor and tell him he can have it if he wants it.’ Then," McDougal continued, "I went to the ball game to forget the cares, the hunger and the thirst of a poor country artist who tried to sell a picture once a month to a funny paper."

The World published the cartoon the next day— five columns wide on the front page. And it sold so many papers that Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the World, hired McDougal immediately.

All at once, McDougal said, "I was the World's cartoonist, rolling in luxury, eating three, sometimes four meals a day, smoking fifteen-cent cigars, and riding to Albany on an annual pass, with a daily production of from two to ten handmade pictures, each meticulously signed 'McD' in letters not larger than those on a modern taximeter dial. And all this was actually the result of pure ignorance and sheer luck combined. ... With a [private office] 'studio' all my own and a salary of fifty dollars per week, an enormous sum in the newspaper world at the time, I remained there for sixteen years."

McDougal also claims to have produced all the artwork for the World's first color Sunday supplement in September 1893. This production was not a comic supplement, though; that would be launched a year later and would be the occasion of Richard F. Outcault's first work for the World. But to tell that story here would constitute a digression within a digression, and I'm sure that would try the patience of even such passionate perusers as thou.

BACK TO ART

YOUNG. In September of 1892, the year he went to work for the Inter Ocean (in

case you've forgotten during that long apostrophe to McDougal), Young

participated in another inaugural event when he drew pictures for the Inter

Ocean's Sunday supplement, the nation's first newspaper Sunday supplement

to be printed in color. The "first color Sunday supplement" but,

like the World's first color Sunday supplement, not devoted entirely to

comics.

During

this period, Young worked with cartoonist Thomas Nast, who was briefly

associated with the Inter Ocean after leaving Harper's Weekly.

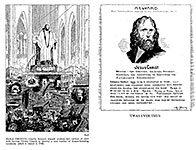

Late in 1892, Young published his first book of drawings and text, Hell Up to

Date, in which the cartoonist indulged his fascination with both Dante and

Dore by depicting various contemporary malefactors in torments appropriate to

their sins. The man who invented barbed wire, for instance (responsible for

the gashed and bleeding cattle Young had seen in his youth) is condemned to sit

naked on one of his fences for eternity.

On New Year's Day 1895, Young married Elizabeth North, a hometown girl, and soon after, the Inter Ocean's staff being cut back under a new owner, he left Chicago and went to work for the Denver Times in Colorado. He went alone in order to test the waters before bringing his wife West. While in Denver, he heard lectures by Christian Socialist minister Myron Reed and British labor leader Keir Hardie and began to question the social justice of capitalism.

In the fall of 1895, Young left Denver, collected his wife in Monroe, and took her with him to New York where he freelanced cartoons to the weekly humor magazines Puck, Judge, and Life. He also worked briefly as political cartoonist for Arthur Brisbane on William R. Hearst's Evening Journal where he joined the Hearst chorus in advocating war with Spain— a proposition he would regret having espoused all the rest of his life. Meanwhile, Young was agonizing about his marriage.

YOUNG'S ATTITUDE TOWARDS MARRIAGE is perhaps the most unusual aspect of his life. It is matched only by his unblinking frankness in recounting his failure as a husband.

Almost from the day of his wedding, Young had felt constricted by marital life: while not apparently in any way a libertine, he felt keenly the loss of the freedom he had previously enjoyed to pursue his art without regard to the daily "routines and binding extractions" (as he said) of married life, and his growing depression affected his work.

After a couple of years of marriage, he separated from his wife in order to be able to work and earn enough to support her. They reconciled in 1900, and the first of their two sons was born that fall. In 1905, they purchased a farm in the country near Bethel, Connecticut, but the pastoral life was not to salvage the union. They separated permanently later that year.

"I was simply no longer equal to the duties and courtesies of married life," Young wrote in his 1939 autobiography, Art Young: His Life and Times; "it had become impossible to combine domesticity and creative work.

“I could not adjust myself to the routine of domesticity. There was a feeling always that I was shut in—that I didn’t belong to myself. I missed my old solitude, the easy-going way of having my meals any time I wanted to, of going to bed at any hour and getting up when I liked—unless there was special reason to arise early to do some drawing for which an editor was waiting. Day after day this kind of living annoyed me. Why must I stop for lunch at twelve o’clock if I happened to be right in the swing of an absorbing cartoon? To be courteous? Which comes first—I kept asking myself—dutiful domesticity or draftsmanship and dreams?

“In our family relations, I seldom protested, for I preferred at all costs to avoid a scene. ... Yet these things continually irked me, and left scars, and I was envious of artists who could ‘let go’ when their emotions got pent up , who could raise hell if interrupted at their work by foolish questions. ...

“I began day-dreaming about open roads and fields—the soil, rippling streams, and the sunshine as I knew them in boyhood. If only I could go barefoot again, wade in a creek and feel the cool touch of plowed ground. If only I could let the warm sun soothe the back of my neck while I stood with naked feet on a grassy knoll. ... I would be well again mentally as well as physically.

“The fact that the bars which formed my cage were invisible made them no less real. I realized that something had happened inside of me when I married that had crippled me—nothing, of course, that one could describe in words.” He missed “the days when I was single, the days when I was not in constant fear of being thought selfish for thinking more of my work than of the household routine. My mind being troubled, my output suffered.”

Young may have been gay, although no one that I'm aware of has ever advanced this notion in explanation for the cartoonist's washout in marriage. If he was gay, it is entirely likely that Young was not, himself, fully aware of it. He may not even have known homosexuality exists.

More likely, Young was merely suffering from a repressive childhood. “My contacts with girls when I was a growing boy were of course necessarily superficial,” Young wrote. “However much I felt the need of some sex association, I was hemmed in on all sides by the religious, puritanical taboo that young people must not mate in advance of marriage. ... When I was about fourteen I heard a sermon by the Rev. Mr. Bushnell in the Methodist church on ‘carnal sin.’ Carnal was a new word to me, but there was no mistaking what he meant. He condemned the sexual act without qualification. Quoting the Bible, he skipped the pages where the tribes of Israel seemed to do nothing but ‘begat’ day and night. ...

“Despite all the apparent hypocrisy of certain leaders of moral conduct in our town [not to mention Mr. Bushnell, who had seven children], I was infected during those formative years with the thought that sexual union was really a sin. The grown folks said so—so it must be so.”

During his early years in Chicago while living in a rooming house, Young had his first sexual experience with a young woman in the next room. Said Young: “Knowing much more of life than I, she was unafraid, and her ecstasy was like wine to my senses. Here was romantic adventure about which I had wondered and for which I had often longed. But quickly thereafter, there was a letdown. ... Echoes of the Rev. Mr. Bushnell’s voice, thundering against the iniquity of carnal sin, swept in to haunt me.”

Young enjoyed the young woman several times, but in the aftermath every time, Bushnell returned— “taking my mind off my work.” Young resolved deliberately to forego any relationship with a woman. “I determined not to become involved in any other passion but the creating of pictures,” he wrote. “All else must be subordinated to that. ... I simply did not want to assume any emotional responsibilities other than that of pursuing my own artistic development; my career must not become sidetracked by a sentimental attachment.”

Young promptly packed up and went to New York.

Before he left, he had another long evening with his rooming house paramour. She raised no objections to his leaving. On the train to New York, he was “warmed by the thought of her laughter and her supreme self-assurance. I knew she was no more of a sinner than I—and that has been my attitude toward intimate relations between the sexes ever since.”

But an intellectual resolve is not enough to overcome years of repression. Bound by the ingrained conventions of a Victorian midwestern upbringing, perhaps the only way he could understand himself and his obvious uneasiness in a normal marital relationship was to think in terms of marriage and its spousal obligations, finding himself derelict in the latter and believing the cause of the dereliction to be his consuming interest in his art.

Whatever the case, Young's unabashed candor in discussing his failure is highly unusual for the day (for any day, I suppose), but it seems, nonetheless, of a piece with his political attitudes and his professional dedication as they were to emerge. In his principles, he was as uncompromising as he was unflinching about his having flunked married life. His wife soon moved with their two sons to California; Young continued to contribute to their support for the rest of their lives.

ABOUT THE SAME TIME as his marriage was dissolving, Young's political views were taking their final shape. In 1902, Young had returned to Wisconsin briefly to lend his pen to Robert La Follette's Progressive (Republican) campaign to be re-elected governor. But by 1905, Young had rejected the Republican politics of his heritage— including "all bourgeois institutions." And he had resolved never again to draw a cartoon whose ideas he didn't believe in.

|

|

|

Not all of Young’s cartoons were “political cartoons” in the current sense. He also drew cartoons that were simply humorous. And even his political cartoons were seldom of the modern sort, skewering politicians by name. Not at first. Instead, Young sent out barbed shafts aimed at general targets—bloated businessmen who ignored the plight of their workers. And it was for these that he declared his independence from any imposed point of view.

“I would no longer draw cartoons which illustrated somebody else’s will,” he wrote. “Henceforth it would be my own way of looking at things—right or wrong. I would figure things out for myself. If success came, well and good; but to win at the price of my freedom of thought—that kind of success was not for me. Though I perceived that much of life was compromise, in dealing with world affairs or with my own, I would have to sink or swim holding on to my own beliefs on questions of vital importance.”

In 1906, he graduated from Cooper Union where he had been taking courses in debate and public speaking. And in 1910, he realized that he belonged with the Socialists "in their fight to destroy capitalism."

“Speakers for the Social Democratic party provided me with much food for thought,” Young wrote. “They attacked the whole capitalistic system, showed how its different units combined to exploit the producing masses to the nth degree, and how the press distorted or suppressed news to protect this system, of which it was a part.

“Listening to lectures on the class struggle (after I discovered that such a struggle had been going on for ages), I found that I had a great deal in common with the everyday workers. ... I was living in a world morally and spiritually diseased, and I was learning some of the reasons why.”

Young became a socialist and sided with the working man.

“Henceforth, no one could hire me to draw a cartoon that I did not believe in. This had become an obsession.”

|

|

He once returned to Life magazine a check for $100 because after submitting a cartoon suggested to him by editor/publisher John Ames Mitchell, he decided that the idea expressed in the cartoon was not true.

“When I told Mr. Mitchell that I was returning his check and that I positively did not want Life to publish that drawing, he was a big peeved, but said, ‘All right, if that’s the way you feel about it.’”

Young thought that episode would finish him as a contributor to Life, but he found, on the contrary, that Mitchell seemed even more receptive to his work than before.

“Had it come to an argument, however,” Young wrote, “I felt now that I could hold my own. Because of the training I was getting in the Cooper Union debating class, I was more and more able to justify my point of view.”

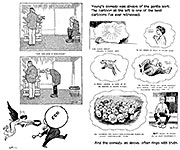

But Young could be funny in a purely comedic manner. Not often. Not at all extensively. Still, it’s too bad that most of his comedy has been overlooked in favor of his more principled social and political commentary. Admittedly, it’s the latter that Young is noted for whenever he’s noted at all. For the record, then, we’ve posted a few of his comical cartoons nearby.

|

|

|

|

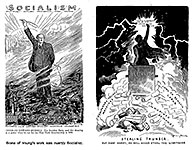

LATE IN 1910, Young joined Piet Vlag and others in launching The Masses, a radical magazine to which he regularly contributed "pictorial shafts" against the symbols of the corrupt system— chiefly, financiers and politicians.

Because of the magazine's precarious financing, Young, like most of the contributors, worked without pay to advance the cause. In 1912, he accepted a remunerative assignment with another radical publication, Metropolitan Magazine, to produce in words and pictures a monthly review of governmental action in Washington, D.C.

Saying "Congress is the best show in the country for a cartoonist," Young made regular trips to the nation's capital for the next six years while continuing his other work in New York. During the presidential campaign of 1916, his political cartoons were syndicated and distributed nationally to more than 200 papers by the Newspaper Enterprise Association.

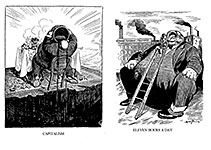

His mature drawing style was distinguished by its uncluttered simplicity at a time when most of his colleagues embellished their work with extensive hachering. Working in bold outline, Young created visual impact with solid black shapes contrasted against the open white areas of his pictures; sometimes, he shaded boldly with grease crayon.

He crusaded against sweatshops, firetrap tenements, child labor, racial segregation, and discrimination against women as well as the traditional industrial and political foes of Socialism. And he harped on about poverty and urban squalor. One of his most reprinted cartoons depicts two slum urchins staring up at the night sky, one declaring: "Chee, Annie— look at the stars, thick as bedbugs."

|

|

In another oft-quoted cartoon, a weary laborer returning home from a day's work, complains that he’s tired, which sparks a telling comeback from his wife. In yet another, Young depicts "Capitalism” as a bloated glutton at the dinner table.

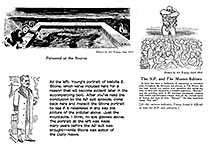

IN 1913, YOUNG

AND MAX EASTMAN, editor of The Masses, were indicted for criminal

libel by the Associated Press. The magazine contended that the AP had suppressed

news in its reporting of a coal miner's strike in West Virginia. Young's

offending cartoon was captioned "Poisoned at the Source" and showed a

man representing the AP polluting the reservoir of "The News" by

pouring into it toxic anti-news liquids.

The

indictment was dismissed a year later; by then, according to Young, the AP had

realized how vulnerable it was to the charges leveled at it. But Young wasn’t

ready to let the AP off easily. Once the AP had abandoned its case, Young did a

second version of the offending cartoon, which was published on April Fool’s

Day. In it, he sarcastically depicts the AP in angelic terms.

Oddly perhaps, the general manager of the Associated Press at the time was Melville Stone, Young’s first newspaper employer, who had admired Young’s cartoons enough in 1886 and hired him to cartoon for his paper. Stone became general manager of the AP in 1893, but none of the histories of the AP v The Masses mentions this coincidence. In fact, neither of two histories of the AP that I consulted mention the libel case. (From which we must conclude that the AP is still suppressing news.)

During World War I, Young lost his assignment with Metropolitan Magazine because it was pro-war and he wasn't.

In 1918, the cartoonist found himself in court again. He and several Masses contributors were charged under the Espionage Act with "conspiracy to obstruct the recruiting and enlistment service of the United States" by objecting to the war. One of Young's outspoken cartoons was called "Having Their Fling": it depicted an editor, capitalist, politician, and minister dancing with joyful abandon to the music played by an orchestra of canon and other weapons under the direction of Satan.

Called to the witness stand and asked why he drew anti-war cartoons, Young responded with simple eloquence, "For the public good."

Later, wearied by the technicalities of the proceedings and the warmth of the April weather, Young fell asleep at the defendants' table, a circumstance taken as a display of his utter indifference. Young later sketched himself asleep during the trial. The trial ended in a hung jury; ditto, a second trial in September.

|

|

Following the suppression of The Masses in 1917, Young and several colleagues started The Liberator, to which he contributed until it was merged with the Communist Workers' Monthly in 1924. In 1919, Young helped found another magazine, Good Morning, a weekly with a radical sense of humor. Within five months of its debut, Young had become editor and publisher—and the chief contributor of both words and pictures—in which capacities he continued until the jovial little magazine expired in October 1921; by then a semi-monthly, it (and Young) had simply run out of money.

|

|

Throughout the remainder of the decade, Young contributed to several publications, including Life and The New Yorker. Beginning in 1922, his were the first cartoons published in Nation magazine, and his cartoons were fixtures in the pages of the New Masses (born in 1926)

By the 1930s, plagued by the infirmities of old age, he produced much less work, and he was occasionally supported financially by his friends. In November 1934, they sponsored a testimonial dinner "not in any sense as charity but as a definite tribute to the enduring value of your work," which raised enough money to keep him comfortably the rest of his life.

A

portly and rumpled figure with wispy white hair and a shiney red "light

comedy nose" (his expression), Young was a familiar sight, strolling the

streets of Greenwich Village with his walking stick.

Young was a founder of the Dutch Treat Club, a luncheon group for artists and writers. And he twice took to the hustings as a politician. He ran unsuccessfully as a Socialist candidate for the New York assembly in 1913 and for the state senate in 1918.

At his death December 29, 1943, of a heart attack in the Irving Hotel on Gramercy Park in Manhattan, the New York Times noted editorially that "he was a lovable soul in spite of his sometimes heterodox opinions" in the advocacy of which "he had sacrificed the chance to accumulate a fair share of this world's goods."

That he was a kindly, thoughtful man, selfless and sincere, with simple but firmly held convictions is borne out by every page of his two autobiographies, On My Way, a sort of diary of musings and anecdotes published in 1928; and the aforementioned Life and Times, published 11 years later. I read both books at least 20 years ago. Maybe even longer. Dipping into them again to revise this essay, I chanced upon anecdotes and names that I probably didn’t realize the significance of when I first read the books. Now I know more and appreciate more.

Here’s a note from Louise Bryant, sent to Young a few weeks before she died: “I suppose in the end life gets all of us. It nearly has me now. ... Know always I send my love to you across the stars. If you get there before I do—or later—tell Jack Reed I love him.”

Twenty years ago, I didn’t know enough about John Reed and Louise Bryant to appreciate the poignance in her remark. Now I do. I think I should read Life and Times again; perhaps I’ll appreciate all of it more.

Observing in its obit that "in his crusading, Young was in deadly earnest," the New York Times called him "a good American" whose calm voice "will be missed."

Indeed. Even more so now in the new century, when the air is blue with political invective, half-truths, unsubstantiated innuendo and, lately, outright lies. But perhaps it was always thus, calm prevailing only in solitude at a drawingboard or keyboard.

|

|

|

|