Bob Montana’s Archie Newspaper Comic Strip

And Who, Actually, Invented Archie

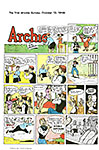

THE COMIC BOOK Archie is so durable an American cultural artifact that it is surprising to discover that the newspaper comic strip version is nearly its equal. The daily began February 4, 1946; the Sunday, later the same year on October 13. And it’s still going—albeit in reruns since June 2012. The comic book character debuted in Pep Comics No.22, cover-dated December 1941. And is still going. That’s 80 years for the comicbook; 65 for the strip. And Bob Montana drew the newspaper strip from the beginning until he died at age 54 on January 4, 1975, of a heart attack while cross-country skiing; he is last credited on the daily of March 1, 1975.

We can see Montana’s handiwork in Archie’s Sunday Finest: Classic Newspaper Strips from the 1940s and 1950s (156 10x13-inch pages, color; 2012 IDW hardcover, $49.99) and in Archie: The Complete Daily Newspaper Comics, 1946-1948 (302 9x11-inch landscape pages, b/w with occasional color; 2010 IDW hardcover, $39.99).

The first-named of these two volumes reprints selected Sunday strips, beginning with the first and concluding with September 24, 1950. Reproduction is excellent; the page size generous enough to show off Montana’s manner. And it’s Montana, not John Goldwater, who invented Archie, Jughead, Betty and Veronica and all the rest of the Riverdale gang.

|

|

|

At Archie Comics, they steadfastly maintain that Archie was the creation of Goldwater, one of the trio that founded the company. But that is not true. Montana explains in his interview with Jud Hurd, publisher of Cartoonist PROfiles, in No.6 (May 1970).

Soon after joining MLJ Magazines, Montana told Hurd, he was approached by Goldwater, who “said they’d like me to try and create a teenage strip.”

At first blush, it looks like Goldwater was the creative impetus. On second blush, it gets complicated.

Like many who have had a role in the early history of comics and who have survived their contemporaries, Goldwater doubtless exaggerated somewhat his claims to fame. In recounting the events of his early life, for instance, Goldwater customarily recollected various of his romantic adventures with the fairer sex that paralleled Archie’s life with Betty Cooper and Veronica Lodge and therefore seemed to support the claim that Goldwater had been Archie’s creator because he had lived in his youth a similar life from which he took inspiration. By the early 1980s, no one was around anymore who could contradict him. It seemed wonderfully pat.

But I contacted Bob Montana’s daughter (through their family website), and I was able to incorporate their version of how Archie was created into my version. Here, then, is my unofficial history of John Goldwater, knitting together as many of the known facts and reasonable testimonies as I can—in as charitable and sympathetic a construction as possible with a conspicuous lamination of some likely alternative interpretations. (You may wish to visit Harv’s Hindsight for summer 2001, which offers more details about Goldwater.)

JOHN GOLDWATER was born February 14, 1916, in New York, New York, son of Daniel Goldwater and Edna Bogart Goldwater. About that, only the date is disputed. In tcj.com, Steve Rowe, responding to an earlier version of this essay, claims Goldwater shaved ten years off his age by claiming a 1916 birthdate. “And so he was married for the first time at age 11? Well no. There are other disputes about his early life as well.... From this we know he was a good storyteller.”

Goldwater’s arrival, whether 1906 or 1916, was (according to Goldwater) accompanied by melodrama enough to be a credit to an aspiring dramatist. According to various sources (for which Goldwater supplied the information), his mother died during childbirth, and the father, overcome by grief, abandoned the child and died soon afterward. Growing up in a foster home, Goldwater attended the High School of Commerce where he developed secretarial skills and some facility as a writer.

At seventeen, he hitch-hiked across country, stopping first in Kansas at the little town of Hiawatha in the northeast corner of the state where he found a reporting job on the local newspaper. In later years, Goldwater said he was fired because he got into a scrap over a girl with the son of the paper’s biggest advertiser.

According to Goldwater, girl trouble was prominent in his young working life. Everywhere he worked on his travels across the country—Kansas City, Grand Canyon National Park, San Francisco—everywhere he went, to hear him tell it, his life was as complicated as that of Archie Andrews—and all because of girls. He’d get interested in a girl (or a pair of them), and he’d be fired because of it.

After about a year, Goldwater returned to New York via the Panama Canal, en route becoming involved (again), he says, with two girls (a blonde and a brunette) in a shipboard romance that went nowhere else.

Back in New York, he worked for various publishers and then became an entrepreneur, buying unsold periodicals, mainly pulp magazines, from publisher Louis H. Silberkleit and exporting them for sale abroad. Observing the success of the Superman character in the infant comic book industry in 1939, Goldwater joined with Silberkleit and Maurice Coyne to launch a publishing firm with himself as editor (while continuing as president of Periodicals for Export, Inc.), Silberkleit as publisher, and Coyne as bookkeeper.

MLJ Magazines (named with the first-name initials of the partners) produced its first comicbook, Blue Ribbon Comics, with a cover date of November 1939. Top-Notch Comics followed in December, then Pep Comics in January 1940, and Zip Comics in February. These titles featured a cast of heroic characters similar to those in other comic books of the period—The Shield (the first patriotic comic book superhero), The Black Hood, Steel Sterling, Mr. Justice, The Comet, The Rocket, Captain Valor, Kardak the Mystic Magician, Swift of the Secret Service, and so on. None of the MLJ costumed crime fighters achieved the success enjoyed by rival publishers with Superman, Batman, Captain Marvel, and Captain America.

And then in late 1941, MLJ published the first story about the character who would make the company’s fortune. Archie Andrews, the irrepressible freckle-faced carrot-topped teenager, debuted in the back pages of Pep Comics with issue No. 22, and, almost simultaneously, in Jackpot Comics No. 4, both titles dated December 1941.

Drawn by cartoonist Bob Montana, Archie quickly became the most popular character in the MLJ line-up and would eventually become the archetypal American teenager. Within a year, he was starring in his own comic book title, and on May 31, 1943, the radio program, “The Adventures of Archie Andrews,” began (to continue, on different networks, until September 1953). A newspaper comic strip version, produced by Montana, started in February 1946 and ran through the rest of the century and, as we’ve seen, into the next.

In 1946, the publishing company officially became Archie Comics Publications. Archie subsequently appeared in a television animated cartoon series (1969-77) and in two live-action television movies. For a brief time in the 1970s, the character lent his name to a chain of restaurants.

In early 1950s, as the nation experienced an increase in juvenile crime, an assortment of critics, psychiatric and literary and political, charged that comic book stories bred youthful miscreants. Alarmed as the critics appeared to enlist greater and greater public support (particularly in governmental bodies with the power to produce controlling legislation), comic book publishers formed an organization to censor their product of objectionable content. The Comics Magazine Association of America was incorporated in September 1954 with Goldwater as President.

“I was its prime founder,” Goldwater said. “Its purpose was to adopt a code of ethics to eliminate editorial and advertising material which was inimical to the best interests of the comic book industry as well as its readers. I . . . succeeded in cooperation with industry leaders to quell the uproar and eliminate legislation which it is said could have put the comics industry in dire straits if not out of business altogether” (quoted in Mary Smith’s The Best of Betty and Veronica Summer Fun).

The CMAA’s chief function was to review in advance of publication every page of every comic book produced by its member publishers to assure that all comic books obeyed the Comics Code. Goldwater was one of the principal authors of the Code, which consisted of forty-one prohibitions concerning the portrayal of crime, violence, religion, sex, horror, nudity, and the like in both editorial and advertising pages. (“No unique or unusual methods of concealing weapons shall be shown”; “Profanity, obscenity, smut, vulgarity, or words or symbols which have acquired undesirable meanings are forbidden.”)

The Comics Code soon drove out of the industry several comic book publishers whose product could not pass the review and still retain its essential appeal. (The most celebrated of these was EC Comics, which had inaugurated an industry-wide trend of horror comic books. Bill Gaines, EC’s publisher, more than once rather strenuously suggested that it was to put EC Comics out of business, more than any other motive, that inspired Goldwater, who was, if we are to judge from Gaines’ remark, the prime censorship mover that he claimed he was.)

Goldwater served as CMAA president for twenty-five years until he voluntarily relinquished the office, whereupon the board of directors created the position of Chairman of the Board, in which capacity Goldwater served for several years.

ALTHOUGH THE QUESTION of who created Archie is clouded by rival claims from Montana and Goldwater, it may be that both contributed to the conception of the character that became the cornerstone of the publishing company. In Archie Comics own version of its history, Goldwater is credited with inventing the characters and Montana with visualizing them.

Goldwater usually pointed to his teenaged experiences in Hiawatha, Kansas, as the foundation for his vision of teenage life: as reporter for the local paper, he covered the high school athletic contests, which, in small town Hiawatha, were among the chief entertainments of the citizenry.

Montana, on the other hand, points to his high school career at Haverhill, Massachusetts, where he encountered many people who later became characters in Archie. And the Thinker statue outside Archie’s Riverdale High School is a direct borrowing from Haverhill High.

Goldwater says the “catalyst” for Archie was Superman. “Archie was created,” he told Mary Smith, “as the antithesis to Superman—ordinary believable people with a background of humor instead of superheroes with powers beyond that of any normal being. Innumerable sleepless nights, dreaming and writing and rewriting characters that could catch the public’s fancy as Superman had was not just an ‘idea’ but a conscious appraisal of my experiences in the Middle West, California, and elsewhere. I had gone to school with a boy named Archie who was always in trouble with girls, parents, at school, etc.”

This notion seems at pretty severe odds with the usual supposition (mine, and I’m not alone) that Archie was an attempt to cash in on the popularity of such contemporary teenage heroes as Andy Hardy in the movies (sixteen of them, 1937-1948) and Henry Aldridge on radio (1939-1953). Still, MLJ hadn’t had any success with the superhero genre, so Goldwater might well have been looking into other more ordinary crannies for inspiration.

To suppose, for the nonce, that in this dispute, as in most such contests, each side has possession of a part of the truth, we can construct a situation that gives both sides credit for some part of the creation. Perhaps it went something like this:

Montana (according to his daughter quoting her mother) had been sketching ideas for a teenage comic strip for some years before he began freelancing with MLJ Comics in 1941. He presented his idea for a strip about four teenage boys to Goldwater, who was looking for a feature about teenagers (probably inspired, as I say, by the popularity of Andy Hardy and Henry Aldrich).

Goldwater then suggested that the cast be reduced to two boys, Archie and Jughead (Forsythe P. Jones), and, ostensibly drawing upon his own youthful adventures in the West with the opposing sex, he directed Montana to add a romantic interest, who was Betty Cooper. Vic Bloom reportedly wrote the first story, perhaps guided somewhat by the Popular Comics character, Wally Williams, who had a sidekick named Jughead. (Ron Goulart told me that Wally Williams was written by a Vic Boni, who, he supposes, could have been Bloom writing under another name.) (Or vice versa.)

Veronica was missing from the initial appearances of the feature, but subsequently, after the first or second story, we may suppose that Goldwater recommended that Archie’s love-life be complicated by a rival to Betty (again, as Goldwater implied, relying upon his memories of his own escapades with blondes and brunettes in tandem). This was Veronica Lodge, a dark-haired vamp in contrast to Betty’s blonde wholesomeness. She was named after a movie star, Veronica Lake, who was a blonde, not a brunette, and famously combed her hair so it covered one eye and that half of her face.

With the arrival of Veronica in April 1942, the stage was set for what became the feature’s chief plot mechanism—the competition between the two girls for Archie’s favors, a canny reversal of the traditional competition in which two men vie for one woman. (The sort of reversed configuration that Goldwater—again according to Goldwater—had apparently found himself in frequently. Known out West, he says, as “Broadway” because of his New York origins, he seemingly regularly attracted the affections of at least two girls at the same time.) In the comics, Archie complicated the reversal by not being able to make up his mind which of the girls he desired most.

Maybe, however, it was nothing like this. I asked around in various places to find out if any living witnesses could be found who recalled the creation of Archie and company. Jay Maeder kept my request in mind and was able, eventually, to provide the following:

“Met a gent named Joe Edwards at a cartoonist function yesterday, and, as he turned out to be a very early MLJ guy who said he'd been around at Archie's creation, I picked his brain a little. And he sez: One day he and Bob Montana were called in by John Goldwater and instructed to whip up something new, market-wise, something totally unlike all the costumed-superhero stuff flooding the stands. Whereupon he and Montana sat down and created Archie and the whole cast of characters. This was the entire sum and substance of Goldwater's contribution. In short, Goldwater had nothing to do with it. Not only did he not specify an Archie-like character, he never even specified teenage humor. All he wanted was non-superhero.

“RE the story Goldwater told about his having hitchhiked around the country and gotten into some small-town trouble over the local Indian babes, this ostensibly being the genesis of Reggie [and of Betty and Veronica]: Edwards says he's heard that story many, many times, and it's a total crock. How self-serving Edwards' own version might be, I can't say. He didn't seem to be a braggart or a blusterer (unlike JG, for example), and his Bails listing supports the career history he gave me. Anyway, for what it's worth, here's a primary-source reminiscence for ya.”

David Allen’s introduction to the Archie Sundays book repeats the company line, saying: “Goldwater told the young Montana of his Archie character and asked him to develop the visuals.”

In the PROfiles interview, Montana goes along with this, crediting Goldwater with conceiving of a comic book feature about teenagers. But this 1970 interview was published whilst Montana was still, in effect, an employee of Archie Comics—and Goldwater was very much alive— so he must needs quote the company line or risk losing his job.

Said Montana: “John thought of the name ‘Archie,’ and together we worked it out. I created the characters and developed it.”

He’s still allowing for the company line but coyly glossing over who created what—“together we worked it out.” Having allowed as much as he did to Goldwater, he then takes the greater credit: “I created the characters and developed it.”

I don’t think there’s any doubt that Montana invented Archie and the Riverdale gang. Or, to put it another way, I don’t think there’s much but doubt about the Goldwater version of the creation of Archie et al.

Montana greatly enjoyed his high school years, and he admits that he perpetuated them in Archie.

“In Archie,” he told Hurd, “I’ve drawn heavily on teachers and characters I met at that time. I’ve never admitted this though—I wouldn’t want to get sued.”

MONTANA WAS BORN INTO VAUDEVILLE on October 23, 1920: his mother was a Siegfeld Follies dancer and his father did a cowboy and banjo act in which the young Montana and his sister sang harmony. “I did rope tricks, and she did a buck-and-wing.”

From the age of four, Montana traveled with his family on vaudeville’s Keith Circuit. Impressed by Frederic Burr Opper’s Happy Hooligan and George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, he drew cartoons from an early age. “I would draw a lot in order to while away the long hours we spent on the train [going from place to place on the Circuit] and in dressing rooms. My parents encouraged me.”

When vaudeville died in 1929, the family went into the restaurant business in Boston. “I did murals on the walls of a night club we ran,” Montana told Hurd.

Montana took some courses in art but nothing in cartooning.

While traipsing around the Circuit, Montana said, “my schooling consisted of taking the Calvert Course, which was a correspondence course for professional children traveling on the road. My mother worked with me on the lessons, which went up to the ninth grade.”

Later, he studied sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts School in Boston.

“This was at a point where I got sidetracked from cartooning and thought I wanted to be an illustrator.”

But that didn’t last long. After his father’s death, Montana went to New York and put himself through the Phoenix Art Institute on Madison Avenue. In addition, he went to the Art Students League and took Life Drawing and other “serious” courses.

But his interest in cartooning re-emerged, and, realizing at last that he had to make a living, he found a position at MLJ Magazines. “You see, I had to eat,” he explained.

And soon after that, Goldwater supposedly directed him to develop a feature about teenagers.

Montana left MLJ Magazines in late 1942 for military service in World War II.

“Archie had become a hit and they kept it going while I was away,” he recalled. “I was at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, and at Astoria, making training films. I worked with various Walt Disney animators and our colonel was Frank Capra, the famous movie director.

“I also drew for the camp newspaper, as so many other cartoonists did during the War. It was during this period that I met Peggy, the girl who later become my wife. She was the secretary to the captain. And I was a sergeant.”

When Montana returned to civilian life and MLJ in 1946, it was deemed time to introduced Archie to newspaper readers and Montana was given the job. While Montana was solely responsible for the newspaper comic strip version of Archie until his death in 1975, Goldwater continued to oversee the operation of Archie’s fate in an ever-lengthening list of teenage comic book titles from Archie Comics.

Montana

described to Hurd his routine. He wrote the strip in the mornings—all six of

the dailies one morning; the Sunday on another. “Following that,” he continued,

“it usually takes me from one to  two days to pencil the six daily strips. I

pencil the Sunday page, as a rule, the same day that I write it.

two days to pencil the six daily strips. I

pencil the Sunday page, as a rule, the same day that I write it.

“Next, I ink the heads or anything particularly important and then send the stuff to my assistant [whom he does not name] ... who inks the bodies, the backgrounds, etc., and delivers the finished strips to King Features.”

He added that in recent years, he’s started slipping a little satirical commentary into the strip. “I want it to say something,” he said. “I’m trying to make the strip more contemporary and am slyly injecting some social comment wherever I can.”

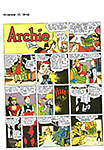

IDW’s COMPANION ARCHIE VOLUME for the daily strips prints three strips to a 9x11-inch page; facing pages thus make up a whole week, Monday through Saturday. The book prints all the strips consecutively, starting with the first Archie on Monday, February 4, 1946, and ending with the strip for Saturday, October 16, 1948. In appearance, the strips didn’t change much in this roughly two-and-a-half year stretch. Montana’s line was perhaps a little bolder in 1948 than it was in 1946, but not much: his pictures were always confidently rendered with a clean flexible line and no hachuring.

|

|

It

can be debated if the girls were a little more buxom (but not drastically) by

the end of the book; you’d notice this change only by comparing the strips at

the front of this volume with those at the end. A reader encountering the

strips day-by-day would notice no difference. While Archie’s wardrobe almost

never changes, it’s clear that Montana worked to keep Betty and Veronica

attired in the latest teenage fashions.

The strip was a gag-a-day venture, but initially Montana ran a storyline to string the gags together for at least a week of continuity, sometimes as much as a month. In the 1950s, he gave up on continuities and stuck to a gag-a-day.

The book ends with a long essay by Maggie Thompson about the pulp magazine industry out of which MLJ Magazines, Archie’s birthplace, developed. She concentrates on the career of Louis Silberkleit (the “L” in MLJ).

Touching briefly on the creation of Archie, she maintains the company myth that Goldwater created the character. Her essay is accompanied by rare illustrative material— including the splash page of a realistic comicbook mystery feature that Montana drew and a photograph of several of the MLJ artists.

In his Introduction to the volume, Greg Goldstein correctly notices the “kinetic energy” of the strips. Characters are always active physically, and the jokes often depend upon the pictures. Remembering Montana’s youth in vaudeville, Goldstein says it’s “clear that those early childhood influences of slapstick and pratfall defined his work.”

Goldstein goes on to note that “it is here in the daily strips that we see Archie and his gang evolve. Archie himself, at first, seems like he descended from the same family tree that Alfred E. Newman would ultimately emerge from. Within a few short months, however, he morphs into the more recognizable ‘every kid’ we know today.” (But I think Goldstein means Alfred E. Neuman, Mad’s mascot with a ‘u’ not a ‘w.’)

“Much of Montana’s genius is in his ability as a storyteller,” Goldstein says, “—he also packed each strip with a lot of funny sight gags. In the Cartoonist PROfiles article, Montana explains:

“The only way I could think of to compete with all the other great cartoonists would be to try to have as many things going for me in the strip as possible ... I would throw away gags throughout a Sunday page, for instance, and didn’t just concentrate on one gag at the end of the page.”

If anyone besides Dan DeCarlo, who established the visual style of Archie (Montana’s style), kept Archie alive all these years, it was Bob Montana, who also created the character. And we’ll stop with a few more samples of his work.

|

|

|

|

Bibliographic Details. Goldwater wrote a history of the CMAA, Americana in Four Colors: A Decade of Self-Regulation by the Comics Magazine Industry (1964) and collaborated on The Best of Archie (1980), chiefly a collection of reprinted comic book stories. The most complete biographical account was obtained by Mary Smith by interviewing Goldwater and is published in Smith’s The Best of Betty and Veronica Summer Fun (1991), a publication of the Archie Fan Magazine. The creation of Archie is rehearsed in Archie: His First 50 Years by Charles Phillips (1991). The story of the founding of MLJ is given in Over 50 Years of American Comic Books by Ron Goulart (1991), and the birth of the Comics Magazine Association of America and the criticism of comic books that prompted its creation are discussed at length in Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code by Amy Kiste Nyberg (1998). And Montana is interviewed by Jud Hurd in his Cartoonist PROfiles, No.6 (May 1970). Parts of the foregoing essay appeared in my Hare Tonic in The Comics Journal online, July 2011; this entire essay also appears in the online Journal (tcj.com) for May 12, 2021.