Chas

Addams with Macabre

And a Dash

of the Diabolical

The ensuing discussion and appreciation of Charles Addams, by report a warm gentle man with a fey sense of humor, his cartoons to the contrary notwithstanding, started as a review of Linda H. Davis’ biography of the cartoonist, but I found myself summoning to the task some of everything else I could find out about Addams. The review is still embedded in what follows, and my rehearsal of Addams’ career is often—and largely—dependent upon Davis’ book, but I’ve also gone beyond it a little here and there, enough so this essay is somewhat more than a book review.

CHARLES ADDAMS—who signed his cartoons of incongruous comedy “Chas Addams” and whose friends called him Charlie—would be pleased at the treatment he receives in Linda H. Davis’ Chas Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life (196 6x9-inch pages; Random House hardback, $29.95). She begins: “They say that Charles Addams slept in a coffin and drank martinis with eyeballs in them.” She continues with a litany of aberrant evidences of Addams’ peculiarity, citing the guillotine he was supposed to keep in his house, the chopped off fingers that fans sent him, and the monogrammed straitjacket he once received as a birthday gift, and then she describes the classic Addams cartoon, in which a ghoulish man shows up at the maternity ward to claim his offspring, telling the nurse, “Don’t bother to wrap it; I’ll eat it here.”

From the opening pages on, Davis perpetuates the legend of the macabre persona that Addams had created and assiduously cultivated for most of his life, earning him, as she says, “such sobriquets as ‘the Van Gogh of the Ghouls,’ ‘the Bella Lugosi of the cartoonists,’ ‘the graveyard guru,’ a purveyor of ‘American Gothic.’” Davis is Addams’ willing collaborator in this fond fraud, but she also points out, almost immediately, that the cartoonist never drew a cartoon with a ghoulish father contemplating his newborn offspring for dinner. “People swore that they had actually seen the maternity room cartoon,” Davis says, “but Addams had never drawn it.”

Much of Addams work was “funny without being dark,” she continues, “and marked by great sweetness,” but it was “the sinister stuff that had made him famous.”

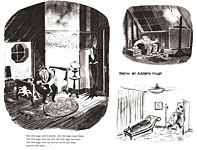

True; most of us remember Addams as specializing in a bizarre brand of comedy founded upon the inexplicable in nature and the anti-social in mankind. In one unsettling cartoon, a skin diver comes across a giant bathtub plug (with chain) in the bottom of the ocean. In another cartoon, vultures perch in a tree at the edge of a precipice atop which a sign reads, "Lover's Leap." In yet another, a couple strolling through the woods see a bird house the size of a garage. And then, waiting outside the delivery room, a cloaked and beady-eyed bald man with tiny fang-like teeth is told by the nurse, "Congratulations—it's a baby."

Addams' cartoon children often engage in fiendish amusements. In a shop class where boys are making bird houses, one child is putting the finishing touches on a small coffin. In an art class where students are making clay figurines in the image of their model, one boy is sticking pins in his figurine. The same boy is shown on another occasion in a bathroom, reaching up to the medicine cabinet to dip an arrow in a bottle marked "Poison."

Addams' drawing style is individualistic but unassertive. His sturdy line is perfect for picturing his people who are all a little stout and dumpy-looking. Sometimes even strange, alien. And a wash shrouds virtually every one of his pictures in somber hues of gray that seemed vaguely menacing.

Disconcerting,

yes; Addams’ “cartoons of diabolical mein,” as Brendan Gill called them, clearly

display a somewhat bent albeit engaging sense of humor. But as Davis’ book

unfolds her tale of his life, Addams emerges as more bon vivant than ghoul. He

assuredly fostered a reputation as the latter, but he lived the life of the

former.  And

Davis works diligently to keep the ghoul alive as a sort of puckish goblin

while introducing the affable and kindly man-about-town, sprinkling the book

generously, soaking it, with colorful anecdotes and Addams’ own quirky

comments.

And

Davis works diligently to keep the ghoul alive as a sort of puckish goblin

while introducing the affable and kindly man-about-town, sprinkling the book

generously, soaking it, with colorful anecdotes and Addams’ own quirky

comments.

Seated in a restaurant, Addams was approached by an attractive young woman who asked: “Aren’t you Charles Addams?”

“Well, I guess so,” he conceded in what we are assured is his early American Gothic voice.

“Don’t you spell that with two d’s?” she asked.

“Three d’s,” he told her.

Another time when he ran into photographer Tony Hollyman after having not seen him for a long time, Addams said: “Aren’t you still Hollyman?”

One of his numerous women friends told him that when people asked her about him, she told them he was very nice. Addams was appalled: “Lord, you’re going to ruin my reputation. Why don’t you describe me as having a faint scent of formaldehyde?”

Over lunch one day, fellow cartoonist Mort Gerberg asked Addams conversationally what he did over the weekend.

“Well, it was really such a nice day on Sunday,” Addams said, “I decided to take a friend for a drive—to Creedmore.” Creedmore is a state psychiatric facility in Queens.

“Gerberg wasn’t sure whether he was kidding,” Davis finished.

The book is rich with this sort of anecdotal insight, gleaned mostly, as 42 pages of notes at the end tell us, from the author’s interviews with Addams’ friends, scores of them.

Reporters frequently inquired into the conditions of Addams’ childhood, seeking the origins there of his fascination with the unusual. Addams admitted to a youthful interest in drawing skeletons and in roaming cemeteries, but apart from playing an occasional practical joke, his childhood, he insisted, was normal and healthy.

Davis gives us both, entitling her first chapter, “Arrested at the Age of Eight,” and then explaining in the next, “A Normal American Boy,” how young Charlie with some of his friends had broken into a deserted Victorian mansion in his neighborhood and committed several acts of minor vandalism, which brought the law on him in the person of a cop knocking at the front door of his home.

“I had never seen a policeman with his hat off before,” Addams said, recalling that his mother had invited the officer into the house. “They took me down to the local court with the other children. My father paid the damages. It wasn’t really an arrest, but I like to think of it as one,” he concluded, revealing, as he often did, the tireless publicity campaign that he waged.

Addams was born Charles Samuel on January 7, 1912, in Westfield, New Jersey, the son of Charles Huey Addams, manager of a piano company, and Grace M. Spear. His father, who had studied to be an architect, encouraged young Charles to draw, and he did cartoons for the student paper at Westfield High School. He entered Colgate University in 1929 but transferred after a year to the University of Pennsylvania, which he left the following year to enroll in the Grand Central School of Art in New York, where he spent the next year (most of it, he once confessed, just "watching people" walk through Grand Central Terminal).

When his father died unexpectedly in May 1932, Addams left school to help fill the family coffers. He embarked upon a career as an illustrator, taking a job as staff artist for Macfadden’s True Detective magazine where he dabbled in “gangster gore,” doing lettering, retouching photographs, and drawing diagrams of crime scenes for $15 a week. “It was just a job,” he said later, denying that it affected his outlook on life or his sense of humor: “It didn’t hurt me.” But he confessed that he liked the photographs un-retouched, “with just a tad more blood and gore.” More self-promotion.

At the same time, he started submitting cartoons to various magazines. The New Yorker bought a spot drawing from him in 1932 for $7.50. Soon thereafter, Addams was selling regularly enough that he quit his job at Macfadden ("the last and only job I ever had," he said) to earn his livelihood solely as a freelance cartoonist.

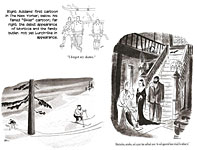

Although he sold cartoons to many magazines during the 1930s and 1940s, Addams is most closely associated with The New Yorker, where his autopsical sense of humor became a fixture. That magazine bought its first Addams cartoon in 1933—a picture of several hockey players, one of whom is standing on the ice in his stocking feet, saying sheepishly to a teammate next to him, "I forgot my skates." A relatively innocuous joke in the Addams oeuvre. Addams thought it slight and not funny and was surprised The New Yorker bought it and published it in the issue dated February 4.

The cartoonist's popularity, however, began with the publication in the magazine for January 13, 1940 of a cartoon showing the parallel tracks of a skier leading directly up to a tree and then going around it, one track on either side. No caption, but Addams put a second skier in the cartoon, pausing in his ascent up the slope to stare in seeming disbelief at the ski trail. Addams admitted that he never quite understood the cartoon himself, but he was delighted that a Nebraska mental institution used the drawing to test the mental age of its patients. "Under a fifteen-year level, they can't tell what's wrong," Addams said. The second skier in the drawing is key to its success, the cartoonist explained: without the witness on hand, “you’re not sure that it really happened, and I think he gives it a logic that it would not have otherwise,” bringing it “into reality,” so to speak.

The phenomenon of the tracks is so astounding that we seldom notice that the skier who made them is still in the picture, just downhill from the tree a bit, slipping off the picture into limbo. And because we seem to have forgotten, or never actually noticed, this skier, most of us are surprised to realize that the skier is a woman. Or so it would seem. That’s surely a hank of hair waving in the slipstream behind the skier’s head, not a scarf. So if it’s a woman that Addams drew there, what does that mean for the mystery? Addams, as I said, professed not to understand any of it. Neither does Davis, but she notes that Addams’ skier came along after the skiers in several cartoons by other New Yorker cartoonists.

Given the effect “the Skier” had on his subsequent career, it is surprising to note, as Davis does, that the idea was not Addams’ but, probably, a New Yorker staff member’s. Davis had access to Addams’ notebooks in which he recorded sales and the amounts earned as well as the names of gag writers with whom he shared the proceeds. For “the Skier,” no name appears in his notebook, which, I gather, is what happened when the idea was conjured up by a staff member—or, perhaps, by Addams himself. But Davis asserts that “someone had pitched the idea to him, and he had drawn it.”

The magazine’s staff members, chiefly E.B. White and James Thurber, were usually the contributors of ideas for the cartoons, a practice that continued until the 1950s, when William Shawn inherited Ross’ mantle and decreed that cartoons, henceforth, would be the product of the cartoonist alone, unassisted by writers. In the 1930s, drawings and gags were often submitted as separate, individual entities. A cartoon rough submitted by one cartoonist might be finished by another, whose style was better suited to the subject. If a gag idea needed a crowd scene, Davis says, Carl Rose was frequently picked to draw the cartoon because he did crowd scenes so well. If someone sent in a gag about a middle-class matron, Helen Hokinson might get the assignment—or Mary Petty. Although both managed convincing matrons, there was a difference: “A Mary Petty dowager,” Davis says, “was to a Helen Hokinson matron what a hothouse flower was to a garden perennial.”

In a career lasting over fifty years with The New Yorker, famed cartoonist George Price produced only one idea of his own for a cartoon, a cover drawing of store Santas commuting on the subway. Some of the magazine’s newer cartoonists initially felt disappointed when they learned that “the wizard wasn’t a wizard,” Davis reports—that Addams worked with purchased ideas. But they eventually came around to cartoonist Mischa Richter’s view: Addams, Richter felt, “was like ‘an actor doing a part’ written by another person.” Richard McCallister, a writer, and Herb Valen, an agent who found advertising commissions for cartoonists, were Addams’ chief idea men. But Addams’ most famous creations started, apparently, as his own inspiration.

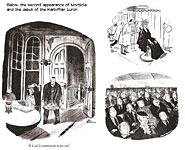

IN THE LATE 1930S, ADDAMS created the vaguely fiendish family for which he is usually remembered—“the Hallowe’en version of Norman Rockwell and Grand Wood,” as Wilfrid Sheed put it in his Foreword to The World of Chas Addams. The first to appear in the gloomy gothicky Victorian pile that writer Wolcott Gibbs called “a secret, dark and midnight manse” was the lady of the house, a spindle-shanked “glamour ghoul” (as critic John Mason Brown said) with lank locks and chalk-white skin in a hearse-black gown that melts into the floor. In the issue for August 6, 1938, Morticia, as she was christened later, has let a vacuum cleaner salesman into the house, and she watches as he demonstrates his product. “Vibrationless, noiseless, and a great time and back saver,” he says, “—no well-appointed home should be without it.” The appointments of Morticia’s home we see before us: a creaky-looking staircase with fringe-shaded lamps on the newel posts, cobwebs clinging to their shades and to the broken baluster we see on the second floor, a strange female-looking character peering down through the gaps between posts. A bat flits overhead, and next to Morticia stands a hulking, bearded retainer, silent, sinister.

At the time of inspiration, Addams had no intention of developing a series about the occupants of the foreboding manse. But Harold Ross, the irascible editor and canny founder of The New Yorker, encouraged Addams to do more in this vein. Still, Morticia didn’t make a second appearance until over a year later, in the November 25, 1939 issue. Now the retainer is the Frankensteinian butler who will eventually be called Lurch. Morticia is reading and Lurch approaches, noiselessly, with a tea tray, startling his mistress. “Oh!” she exclaims, “it’s you! For a moment, you gave me quite a start.”

The rest of the household accumulated slowly over the next few years: a necromantic Peter Lorre-like husband named Gomez and the baleful couple’s children, an undernourished girl with six toes on one foot and a little fat boy who foments explosives and poisons with his chemistry set, and a hag witch of a grandmother. In what may be their most celebrated appearance, the family is on the roof of their house, poised to reward a band of Christmas carolers below by tipping onto them a cauldron of what appears to be boiling oil. (Ross thought it was hot lead.)

Like the Skier cartoon, this one was not Addams’ invention. The drawing was originally conceived by cartoon editor James Geraghty and novelist Peter DeVries, then on The New Yorker staff, as a cover for the 1946 Christmas issue. Ross, when he saw it, was aghast. But Geraghty loved the idea and Addams’ execution of it—the lovingly detailed rooftop, the mansard windows, the wisp of steam emitted by the heated contents of the cauldron—and finally persuaded Ross to publish it inside the Christmas issue, dated December 21.

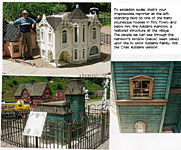

Christened “the Addams Family,” the ghastly ensemble became the touchstone Addams cartoon and created a pervasive image: "An Addams house, an Addams family, an Addams situation are archetypes that we see all around us," according to New York Times art critic John Russell; and Addams, Russell said, was "an American landmark, one of the few by which one and all have learned to steer."

The New Yorker’s pay scale was a multi-layered labyrinthian puzzle invented by Ross to incorporate a variety of considerations, some actual, some mystic: the size of the published cartoon (full-page cartoons were worth more), the productivity of the cartoonist, and other vagaries more peculiar to Ross’s opinion of the caliber of the cartoonist’s work than any objectively verifiable criteria. Addams was “a triple-A” in Ross’s private ranking, Davis says. Only Petty shared that ranking. But three others—Peter Arno, Hokinson, and Gluyas Williams—were “golden,” above all ranks. Double-A artists included Thurber, Whitney Darrow Jr., and George Price. In the A-rank was Sam Cobean, Rose, Otto Soglow, “and others.” In my private pantheon of New Yorker cartoonists, four stand above all the others: Arno, Hokinson, Price, and Addams. In my view, this quartet embodied New Yorker cartoon comedy: they defined, if they didn’t create, the humorous ambiance of the magazine. And none of them appeared very often anywhere else. I realize that describes Petty and Thurber, too, but—hey, opinions on such matters are usually highly personal and, as such, virtually indefensible. And that’s the case here.

Holding up for examination all sorts of morbid and vaguely sinister curiosities, Addams’ cartoons, it has been said, evince the repressed violence that lurks within normal people everywhere. Writing the Foreword to one of the thirteen collections of Addams cartoons, Addams and Evil, Wolcott Gibbs saw Addams' cartoons as "essentially a denial of all spiritual and physical evolution in the human race.” At the Saturday Review of Literature, John Mason Brown said: "His is a goblin world of bats, spiders, broomsticks, snakes, cobwebs, and bloodletting morons in which every day is Hallowe'en." Addams maintained that he arrived at his ominous ideas simply by observing people. One favorite observation point was near the William Tecumseh Sherman statue opposite the Plaza Hotel on fashionable Central Park South in New York. “After five minutes of looking at people there,” Addams said, “even my oddest drawings begin to look mild by comparison.”

But the alleged necropsical preoccupations of Addams’ cartoons abide more in the fervid imaginations of his fans than in the cartoons themselves. As cartoons, as humor, the Chas Addams cartoon is a somewhat simple and not at all spectral mechanism. Its supposed weirdness proves, under examination, not to be weird but quite conventional in dramatic terms. The comedy of the Addams Family proceeds quite logically, quite naturally—not preternaturally—from the characters. Once a vaguely sinister, morbidly preoccupied family of spooks, monsters and mad scientists has been conjured up, the rest follows as effortlessly as the eldrich night follows a gloomy dusk. If Morticia seems to be some sort of witch with death and dismemberment as amusements, it follows that if she goes next door to borrow an ingredient, the ingredient won’t be a cup of sugar. It will be, and was in Addams’ cartoon, a cup of cyanide.

In short, the celebrated necromantic wit of the Addams Family cartoons surfaces whenever the family members simply act “in character.” And so if they are all at the window observing dismally windy and rainy weather, one of them, the husband in this case, is bound to say, as he does: “Just the kind of day that makes you feel good to be alive.” And in another cartoon not involving any of the Addams menage but the witchy hag next door, the hag’s daughter would say, like any teenager under similar circumstances, “Mom, can I have the broom tonight?” Using the same unyielding logic, when Uncle Fester goes out to feed the birds, we see that they’re vultures.

A SIMILAR LOGIC OPERATES in most other Addams cartoons, many of which, as Davis notes, are not at all ill-omened. Here’s a shepherd surrounded by his flock as he knocks on the door of a cottage and asks the woman of the house: “Crop thy lawn, lady?” Once you have a shepherd with a flock of sheep who customarily eat grass, biting it off very close to the ground, why wouldn’t you expect the shepherd, as a purely logical matter, to take up lawn “cropping” as a way of earning a little extra cash?

Much of Addams’ humor results from extending the logic of a particular situation—and extending it and extending it. And so when a man in a restaurant introduces to a friend the woman he’s dining with, saying, “Miss Osborne poses for subway posters,” it is quite logical that Miss Osborne would have a moustache and a goatee as do most faces on posters in the subway. And it is equally logical that on a street of shops all of which have signs over their entryways depicting their product—a watch at a watch repair shop, a shoe at a cobbler’s—the mortician hangs a sign in the shape of a prone body wearing a tux. And when we see a small band of Boy Scouts crossing a log bridge carrying a flag proclaiming them the Beaver Patrol, it is quite logical that they all have prominent buck teeth and that the log they’re walking on is a freshly felled tree, leaving a gnawed-on stump at the river’s edge. Logically, If one fakir on a bed of nails turns to his comrade, also prone on a bed of nails, and proposes a pillow fight, the pillows will be bristling with nails.

These cartoons all follow Groucho Marx’s prescription for professionalism as invoked by Sheed: “Groucho Marx once said that the difference between a professional comedian and an amateur was that if the script called for an old lady to crash down the hill and into a wall in her wheelchair, the professional insisted on using a real old lady. And this is what caused the sharp intake of breath with an Addams cartoon: this guy really means it, doesn’t he? He is using a real old lady. ... In a period when Disney and lesser functionaries had domesticated evil and almost rendered it cute, Addams went all the way with his ideas, crashing them into the wall and leaving them there bleeding.” That’s logic, the terrible comedic logic of the Chas Addams cartoon.

In other cartoons, Addams simply juxtaposed a conventional utterance and an unconventional setting; or vice versa, a time-honored cartoonist device. Here a landlord is showing an empty apartment to a man and woman who are obviously gangsters on the lam. The man stands at the side of the window, peering out furtively; the woman clutches a large violin case. The landlord says, as landlords do everywhere under these circumstances, “Any children?” And in the back of an opium den is the sign reading: “Occupancy by more than 31 persons is dangerous and unlawful.” And here’s a shepherd awakened by one of his sheep, which says, “Meow.”

But there is no explanation for the Skier.

Most of Addams’ humor can be analyzed with relative ease, but it was always humor of a particular, not to say peculiar, kind. He didn’t traffic in ordinary incongruities or everyday premortem comedy. His sense of humor, to which his gag writers carefully tailored their suggestions, was so distinctive that an Addams cartoon could achieve its comic effect just by being an Addams cartoon. In one such production, a man is watching television and drinking from what seems to be an ordinary soft drink bottle. His wife, who has just returned home and is standing in the doorway to the room, has asked a question to which the man replies, "I got it out of the refrigerator. Why?" The mere fact that Addams concocted this cartoon suggests that the bottle must contain something more depraved than a soft drink.

Once Addams achieved fame as a cartoonist, he sought a suitable notoriety as well, appearing at costume parties in odd robes, calling himself “a defrocked ghoul,” or pedaling a child's tricycle while smoking a cigar. On camping trips, he drove a van that he called "the Heap," the interior of which was outfitted with dignified plush furniture, a stuffed partridge and a stuffed grackle. It is somehow fitting that he collected medieval arms and armor, which he displayed in his home. He also had a coffee table made from an embalming table, and stuffed bats and skulls and an antique headsman’s axe were displayed in his abode. As Sheed observed: “In other words, Charles Addams was a consummate craftsman, or magician, who understood that it’s not a bad idea to keep the illusion going between tricks if it helps the tricks to work better.” More conventionally, he also enjoyed owning and driving vintage automobiles and sports cars—Astin Martins, Bugattis, Alfa Romeros, Bentleys.

DURING WORLD

WAR II, ADDAMS SERVED from 1943 to 1946 in the Army Signal Corps, illustrating

manuals and making animated training films warning against syphilis (his only

“job” other than the one he held at Macfadden). The Signal Corps Photographic

Center to which Addams was assigned was in Astoria, Queens, so he was never far

from the city, and he continued submitting cartoons to The New Yorker throughout the war. “For Addams,” Davis writes, “the Signal Corps was

cartoonist Sam Cobean,” whom Addams met in the Astoria shop and called

“one of the great comic artists of all time”—a dark, strikingly handsome man

who, Davis tells us, looked like Tyrone Power.  Addams and Cobean bonded, and Addams

introduced Cobean to The New Yorker. Ross bought the first cartoons

Cobean submitted. After the war, the two shared an office at The New Yorker, and when Cobean died in 1951 at the tragically early age of 38, swerving his

car to avoid another and running into a tree, Addams couldn’t believe it. “Sam

killed,” he wrote in his notebook, using a pencil, Davis says, “as if the entry

might be a mistake he would later erase.”

Addams and Cobean bonded, and Addams

introduced Cobean to The New Yorker. Ross bought the first cartoons

Cobean submitted. After the war, the two shared an office at The New Yorker, and when Cobean died in 1951 at the tragically early age of 38, swerving his

car to avoid another and running into a tree, Addams couldn’t believe it. “Sam

killed,” he wrote in his notebook, using a pencil, Davis says, “as if the entry

might be a mistake he would later erase.”

Addams was married three times and divorced twice. He married Barbara Day, a former model, May 29, 1943, having obtained a few days’ leave from the Signal Corps over the Memorial Day weekend. But Barbara wanted a child, and when Addams reneged on adopting one in 1951, she left him, with another man, a neighbor, in June 1951, just three weeks before Cobean was killed. Addams’ opinion of children might be derived from their numerous deranged appearances in his cartoons, but Addams liked children as long as they weren’t his own. His divorce from Barbara Day was finally achieved in October 1951, and Addams began playing the field with such enthusiastic abandon as to earn a reputation as one of New York’s “most sought-after men.”

Then in the spring of 1953, Addams joined some friends at a bar and met another Barbara, with the unlikely Hollywoodian sur-name Barb, who was apparently so smitten by the cartoonist that she showed up, uninvited, at his apartment, naked under a mink coat. She, like the first Barbara, was a slender brunette who reminded witnesses of Morticia, and Barbara, like Morticia, was somewhat fictional not to say fraudulent. She’d invented a personal history that seemed to her more glamorous than her actual biography, which was a pretty impressive success story. Despite a humble origin, she was a high-powered attorney, specializing in international law.

By September 1953, she was Addams’ almost constant companion; they married in December 1954, and trouble began almost immediately. She ferociously provoked fights with her husband, usually destroying property as she raged. Sometimes, she attacked Addams—once with a stiletto heel applied to his head so severely that he went to the hospital, once by pressing lighted cigarettes into his arm. Davis, who looks a little like Dorothy McGuire in “The Dark at the Top of the Stairs,” calls her “Bad Barbara,” continuing: “Her role in Addams’ life was that of the bad fairy at the christening.” Bad Barbara maintained throughout their marriage a “loving correspondence” with a titled British M.P., Lord Colyton, who she visited frequently and married right after Addams divorced her in October 1956.

Addams had known of her infidelity with the Englishman since the summer of 1955, but—as strange as his sense of humor—in order to get the divorce, he had signed away to her the rights to many of his cartoons and even, although apparently unwittingly, to the Addams Family, an arrangement that later plagued prospects for developing the characters in other media. Addams, almost right away, in December, met the woman who would be his third wife, Marilyn Matthews Miller, called Tee, another brunette and former Powers model who was, at that time, married to a friend, Bedford Davie, and lived with her husband in Nashville, Tennessee. She married Addams 24 years later after she had gone through another husband or so and Addams had dallied with every lusting female in New York (which included, as we’ll see anon, some surprising playmates). Their wedding on May 31, 1980 was held at Tee’s country place in her cemetery for pets; the bride wore a black dress and carried a black feather fan, saying that the groom "likes black and thought it would be nice and cheerful."

IN 1963, ADDAMS WAS APPROACHED by David Levy, an independent television producer, who wanted to bring the Addams Family to the small screen. By September, they’d worked out the details. Then Bad Barbara found out and sprung her surprise, revealing her ownership of the characters. In letter after letter from England, tantrum after tantrum, she demanded more and more. The prospect of the tv series was very nearly scuttled by her machinations, but at the last minute, Addams’ lawyers maneuvered a rescue, and “The Addams Family” debuted on ABC on September 18, 1964, a Friday, with Carolyn Jones playing Morticia; John Astin, her husband; and Ted Cassidy, Lurch. A week later, September 24, a Thursday, “The Munsters,” an obvious clone, started on CBS, with Yvonne DeCarlo paying the mistress of the manse, Lily Munster, and Fred Gwynne playing her husband, Herman, the Lurch counterpart in the series. Both shows lasted only two years, their final telecasts as nearly simultaneous as their debuts had been: “The Addams Family” on September 2, 1966; “The Munsters,” September 1.

The Addams Family members had acquired their names before the tv series began: a set of cloth dolls in production in the spring of 1963 needed names. Addams named them all except the gaunt six-toed daughter, who was christened Wednesday (for the child of woe) by the doll manufacturer. Consulting the phone book under “morticians,” Addams named his heroine. He offered two names for her spouse, Repelli or Gomez (an old family friend), and let actor Astin make the final choice. Gomez. Lurch was suggested by the Boris Karloff Frankenstein monster’s halting gait; Uncle Fester—“I just thought that up as befitting a rotten guy.” The homicidal son, Pugsley would have been called Pubert if Addams had achieved his wish; but the doll people thought it sounded dirty.

Addams wrote character analyses of his creations for Levy, who wanted a guide for the actors. The descriptions are promulgated in the most recent Addams book, The Addams Family: An Evilution (224 8x10-inch pages, b/w and color; Pomegranate hardcover, $19.95—a bargain), published on the eve of the 2010 opening of the Broadway musical based on the characters (with Nathan Lane playing Gomez; Bebe Neuwirth, Morticia). The book was assembled and its text written by H. Kevin Miserocchi, director of the Tee and Charles Addams Foundation, who notes that the cartoonist “relied primarily on his drawings” for his descriptions “although in a few instances he suggests intimate psychological and emotional qualities perhaps not portrayed in the actual works but evidently brewing in the creator’s imagination.”

Morticia, for instance, “the real head of the family,” is “the critical and moving force behind it. Low-voiced, incisive, and subtle, smiles are rare. This ruined beauty has a romantic side, too, and is given to low-keyed rhapsodies about her garden of deadly nightshade, henbane and dwarf’s hair.” Addams often mentioned, Miserocchi says, that “there was a bit of Gloria Swanson, the alluring film star of both the silent and silver screens, in his design of Morticia,” but Morticia is not a voluptuous vampire wife like Yvonnie Decarlo’s Lily Munster but “a weathered, even withered, beauty with no interest in ghoulish practices. She may have loved bats, but that did not make her one.”

Gomez, “dark and scruffy, even a bit greasy,” according to Miserocchi, was, Addams wrote, “sentimental and often puckish—optimistic, he is full of enthusiasm for his dreadful plots.” Pubert, Miserocchi thinks, was a better name than Pugsley: Addams saw the kid as “an energetic monster of a boy—a dedicated troublemaker,” and Pubert, “short and to the point, expressed exactly how Addams felt about the creativity and energy locked up in young” pre-pubescent boys. Despite his proclivity for murderous mayhem as amusement, the boy is “easily controlled by Morticia, though Lurch and Gomez keep their backs to the wall at all times when he’s around. His voice,” Addams added slyly, “is hoarse.”

Uncle Fester, who was the last of the family to show up, didn’t appear until January 18, 1941, and even then, he wasn’t, yet, depicted as a relative. Instead, he seems the husband of a “simple, dowdy wife” as he stands at the ticket office at a train station, asking a dismayed looking clerk for “a round trip and a one-way to Ausable Chasm,” where, we suppose, he will arrange for his mate to fall off the cliff. Fester is, Addams attested, “incorrigible and, except for the good nature of the family and the ignorance of the police, would ordinarily be under lock and key. His complexion, like that of Morticia, is dead white, the eyes are pig-like and deeply imbedded, circled unhealthily in black.” “Fester” seems perfect for such a man—suggesting an open wound, slowly decaying.

Another of the original cast, who appears behind the bar-like balustrades of the balcony in the first cartoon, is “the Thing,” about whom Addams said: “We don’t know quite who or what he is, but, whatever, he’s the soul of good nature—at least, he grins perpetually and may occasionally whimper.”

At The New Yorker, William Shawn refused to publish any more Addams Family cartoons once the tv series was launched—as if the Hollywood treatment had somehow “compromised Addams’ evils,” as Davis puts it. And Addams was bitter about it even though he wasn’t producing as many Addams Family cartoons as he had been. The show went into syndication and ran in various countries for the next twenty years, but Addams saw little income from the series. His last check came in 1974; it was for $179.

Bad Barbara, on the other hand, kept going to the bank. Her greed, however, sabotaged a number of other potentially remunerative deals, and her tactics—tears, flattery, tantrums, harassment by phone—were legendary in the entertainment industry. In 1991, three years after Addams’ death, “The Addams Family” motion picture arrived, starring Anjelica Huston and Raul Julia. “During the making of the movie,” Davis reports, “Paramount reportedly hired a woman whose sole responsibility was to take calls from Lady Colyton.” Tee, as Addams’ widow, shared in the earnings of the movie and its sequel, splitting $6 million with Bad Barbara.

Addams died of a heart attack suffered just as he parked his Audi in front of his Manhattan apartment on the morning of September 29, 1988. He was returning alone from a trip he’d made to Connecticut with cartoonist Frank Modell to see a house Modell was thinking of buying; the two had stopped overnight to visit another New Yorker cartoonist, James Stevenson. Each of chapters 23 through 25 of her 26-chapter book, Davis begins with portions of a prolonged narrative describing the trip, the detours Addams always took on such expeditions (“to find ‘historical sites and architectural landmarks,’ a typical Addams drive in which getting there was the real fun”), and the pleasant time the three cartoonists had shared, watching the Mets play the Phillies on tv, laughing and telling stories about people and cars—“they never, ever talked about cartoons”—and “pissing off the porch.”

Interspersed in the narrative are flashbacks to other Addams adventures and events in his life, a kind of scrapbook of miscellany that could have been fitted in elsewhere but isn’t. We know something is coming, though: Addams was “unusually talkative,” laughing “openly” (which he didn’t normally do). This elongated and episodic maneuver serves as a desultory and affectionate farewell to a person who Davis, as biographer, has come to know and love, perhaps even admire, and Addams’ death slips almost unobtrusively into the narrative at the end, with the dying part merely alluded to. “His was an easy death,” Davis says; “he was found slumped behind the wheel ... he had had a heart attack.”

The book is well but not amply illustrated with Addams’ cartoons. Most of them, despite Davis’ acknowledging that not all of his work was macabre, are of that sort. A modest array of sketches of Addams, mostly by Sam Cobean, and several photographs completes the illustrative content. Quite adequate.

DAVIS’ BOOK IS A VERY GOOD BOOK because she is a very good writer and a meticulous researcher and apparently a persistent interviewer. But her understanding of cartooning is fairly elementary. In a book about a less quirky personality than Addams, this shortcoming would be conspicuous and therefore disastrous. Fortunately, Davis can dwell on Addams’ personal history, which so satisfyingly fills the book’s pages that we scarcely notice that she says very little about the cartoonist’s life as a cartoonist.

I confess that my reservations about Davis’ ability to discuss cartooning began almost at once. On page 4, she describes Addams’ distinctive signature, his name “abbreviated in thick black ink.” I stopped at “thick.” It wasn’t the word I would have used. “Bold” maybe. And it wasn’t the ink that was bold, or thick, it was the line that made the letters of Chas Addams. About the thickness of the ink in Addams’ ink bottle we can only speculate. I would have said that Addams inked his signature with bold, black cursive script. Admittedly, word choices are not scientifically arrived at; these are stylistic matters, and Davis’ manner of describing Addams’ signature is probably perfectly understandable to the normal reader who is doubtless not obsessed by cartooning. But her word choices here put my teeth on edge a bit. You might say that I proceeded thereafter with a bias waiting to pounce.

And it didn’t take long. On page 43, describing Addams’ first macabre cartoon in the March 23, 1935 issue of The New Yorker, Davis reveals that her grasp of what makes a cartoon funny is either somewhat tenuous or her ability to isolate the key comedic element flawed: “Addams submitted a sketch of newspapers rolling off a printing press. In the midst of a line of Herald Tribunes a tabloid appears with the headline ‘Sex Fiend Slays Tot.’ The editors approved the idea but asked Addams to change the Tribune to The New York Times.”

The inexplicable here, the hideous hilarity, arises from the sudden incongruous appearance of a sensation-mongering tabloid coming off the same printing press as a cascade of dignified newspapers. How the tabloid achieved this impossibility is part of the comedy; the other part, however, requires that we understand that tabloids in 1935 were shriekingly alarmist rags compared to such dignified dailies as The New York Times. Davis realizes this because she mentions the change from the Herald Tribune (which, then and for decades thereafter, was highly regarded for the literate nature of its news stories but not necessarily any inherent dignity) to the Times, which The New Yorker editors knew was a more recognizable bastion of respectability for contrast with the tabloid and its sensational headline. Although the joke here is implicit in the aggregate of what Davis writes, she could have made it clearer: “In the midst of a line of dignified and respectable Herald Tribunes rolling off a printing press, a sensation-mongering tabloid appears with the headline ‘Sex Fiend ...’.” A trifling matter, surely, but Davis displays a similar laxity again within a few pages.

On

page 46, she refers to the famous early George Price cartoon series “of

a levitating man [that] ended with a gunshot. ‘He never knew what hit him,’ the

man’s wife tells the cops, with the smoking rifle still in her hand.” That’s

all Davis says. How can we tell, from this cryptic notation, that the

“levitating man” appeared in a series of cartoons that began August 13, 1932,

just two months after Price’s debut in the magazine, in which the cartoonist

depicted a man reclining in space, hovering about three feet over his bed,

being observed by his wife, who says to a visitor at her elbow in the doorway,

“He’s been up there a week.” The same picture is repeated several times over

the ensuing months, and at every appearance, his wife comments differently on

this weird circumstance to a visitor.

Davis isn’t writing a book about Price, so she probably didn’t feel the need to go into as much detail as I’ve mustered here. But why, then, refer to a cartoon in terms so cryptic that the joke isn’t apparent? She does it again twenty pages later, referring to an Addams Family cartoon “involving a squeaky trapdoor” which she apparently expects us to know all about even though the cartoon appears nowhere in the vicinity.

And she misses the black humor in the cartoon showing a “wretched girl skipping rope on a dark sidewalk [chanting], ‘Twenty-three thousand and one, twenty-three thousand and two, twenty-three thousand and three ....’” The little girl isn’t simply “wretched”; she’s gaunt, emaciated, starving slowly to death as she skips rope on and on without ceasing. It’s her imminent death by starvation that makes the cartoon funny in that convoluted way an Addams cartoon ridicules conventional proprieties by subverting them. But Davis misses it—either because she doesn’t see it or because she can’t articulate her understanding of it.

She doesn’t analyze Addams’ humor much at all, and you’d think she would. Addams didn’t and disliked the idea of doing it; so maybe she’s following his lead. Or maybe she doesn’t actually see the humor.

In discussing the first Addams Family cartoon, the one Addams in his logbook called “Vacuum Cleaner”—innocently unaware of what he had just conceived—Davis thinks the cartoonist might have been inspired by an earlier Richard Taylor cartoon depicting a couple who have just arrived at “a spooky place, where they are greeted by a sinister-looking man holding a candle, who says: ‘You’ll be surprised [by] the kind of service we give you at Wyvern Manor.’” In the background lurk spiders and “various creepy characters.” In short, a pretty good “Addams-style” cartoon. But Davis thinks the cartoon is “heavy-handed” and “unfunny”: “the gag got lost in the creepy style.” Her loyalty is evident but her discernment isn’t.

She manages to put up a pretty good front when admiring Addams’ mastery of wash drawing: “With talent and patience, he had learned how to manipulate the unpredictable medium of ink and water—how to tease and tame it to achieve the richness of color using a wide scale of black and white.” And yet she believes Addams’ wash drawings display “a novel drawing technique” despite having numerous other examples of expertly gray-toned cartoons before her in the pages of The New Yorker—Arno and Hokinson to name two of the most conspicuous.

In the same place, Davis describes Addams’ method of working but stops short of completing her description: “For Addams, the real work of cartooning went into the rough. Using a soft carbon pencil called a Wolff’s pencil, and a paper stump, he did his roughs on bond paper, typically spending a half an hour or so on each, filling in enough detail so that one could see what the finished cartoon would look like.” The detail—a Wolff’s pencil—is compelling; ditto when she supports her contention that Addams carefully researched his cartoons by seeing in “the streamlined upright vacuum cleaner” being demonstrated in “Vacuum Cleaner” a visual source in “the stylish Hoover Model 825 (Made in England from 1936 to 1938).” But what’s a “paper stump”?

Continuing her description of Addams’ method, Davis writes: “Once the rough was ‘okayed as an idea’ by The New Yorker, he would ‘just blacken the other side of the paper and trace it down and then refine it,’ he said with characteristic understatement.” It’s an understatement because it’s incomplete. The technique Addams alludes to is a common one among cartoonists of yesteryear. After “blackening the other side of the paper” (i.e., the reverse of the side on which the rough drawing appears), converting it to hand-wrought carbon paper, Addams placed the rough on top of another piece of paper, in his case, Whitman art board, blackened side down, and then with a pencil, he went over the lines of the rough, “tracing” them, pressing down enough to transfer those lines to the Whiteman board by the agency of the pencil-blackened back, which acted like the carbon paper of yore. Today, cartoonists resort to light boxes or light tables for their tracing.

Perhaps such laborious detail as this is not vital to our understanding of how Addams worked, but from Davis’ description, relying entirely on quoting Addams, I’m not sure she understands exactly what Addams was doing.

More seriously, she also gets some crucial dates wrong. Addams first New Yorker cartoon, the skateless hockey player, appeared in the issue for February 4, not January 4. The celebrated skier cartoon was published in the issue dated January 13, not January 12. These are trifling matters in the grand scheme of things, but they loom somewhat larger in a volume purporting to record historic moments in a cartoonist’s career. Davis’ recitation of Addams schooling seems confused about dates until I decided, without her telling me, that Addams had probably graduated from high school at age 17, not 18, the usual age these days.

Elsewhere, Davis seems baffled by Addams’ writing one of The New Yorker editors in the summer of 1935 to tell him that he was going out of town for a couple weeks and wouldn’t be submitting any cartoons for that period. “Why, as a freelancer,” Davis writes, “he felt the need to cover for a lack of submissions is uncertain.” But that’s exactly why—because he was a freelancer. To anyone who freelances, Addams’ conduct is perfectly understandable: he had just begun to sell regularly to the magazine and, feeling a growing sense of engagement, wanted to foster and sustain that sense of mutual commitment by staying in touch with the editors even when not submitting cartoons. But Davis doesn’t see that, revealing that her grasp of a freelance cartoonist’s lifestyle is nearly non-existent.

That makes her achievement in this book all the more remarkable. Admirable, even.

Regrettably, she doesn’t give us much about the relationship between Addams and Ross, the monumentally eccentric and inspired journalistic genius whose inarticulate quest for suitable content shaped The New Yorker and its cartoonists’ work. “Ross,” she writes, “had no training in art but had true instincts” and “pushed for cartoons that told the story without text—the ultimate in cartoon storytelling, which Addams came to prize in his own work.” She notes that Ross paid Addams at the top of the pay scale—no other cartoonist was paid as much—but that’s about all the insight we get into the relationship between the legendary editor and his equally famous cartoonist. Perhaps there is no more to say.

Ross surely understood that talent and publishing talent were essential to his magazine’s success. Thomas Kunkel in Genius in Disguise, his 1995 biography of Ross, says as much, adding: “Ross had a respect for creative people that bordered on veneration; everyone else, himself included, was meant to be in their service.” But Ross spent little time with cartoonists, Kunkel says, and it wasn’t until 1942 at a luncheon for his cartoonists at the Algonquin Hotel that Ross met Addams, who, by then, had been contributing to the magazine for eleven years.

After producing the biography, Kunkel edited a collection of Ross’s letters, Letters From the Editor, in 2000, and one of them is about Addams—only one—but it reveals Ross’s attitude about the cartoonist better than anything Davis finds to quote in her book. Cartoon editor Geraghty had told Ross that Addams wasn’t satisfied with his pay, and Ross wrote about it to Hawley Truax, his informal liaison to the business department of the magazine:

“Mr. Addams is a special problem, somewhat like Mr. Mitchell among the writers—excellent quality, low productivity. He has sold us only seventeen drawings this year [1946]. Ideas for him are scarce by their nature. We have been able to give him twelve ideas only. If he could do forty or fifty drawings a year, he would be sitting pretty, and so would we. Mr. Geraghty has tried to lead him into other kinds of work for us, but without much success to date. He doesn’t get much advertising work, etc., as do the other artists because of the limitations of his style [his sense of humor, I’d say]. He’s some kind of special proposition beyond question; and I recommend consideration him as such. I have no solution, no constructive thoughts at the moment.”

A special proposition indeed.

Ross was famously stand-offish with his cartoonists and writers because he didn’t want to get involved in what he saw as their messy personal lives. Most of the editor’s connection with his contributors was by notes directly to them or, more often, through intermediaries. So there is probably no more to the Ross-Addams “relationship” than I’ve so far cited. But given Ross’s fame and his legendary attention to detail in cartoons, Davis could have shown at least as much light as I’ve shed on how the two got along.

THE BOOK, AS I REFLECT ON IT, seems mostly about Addams’ social life—his affairs, his women, his trips with them to antique shops in Pennsylvania and favorite cemeteries en route, his marriages—and not much about his work life. With Addams, who apparently had a very energetic sex life and a bizarre sense of humor that Davis frequently refers to, this void is not so noticeable. It is probably impossible to trace the evolution of every cartoon idea in the detail she devotes to the “Sex Fiend” cartoon or the “Boiling Oil” cartoon, but she might have found a way to get us more deeply into Addams’ work methods or his life in The New Yorker offices or his relationship to Ross or other magazine staffers. Davis touches on these matters—a paragraph or two about Addams’ drawing tools and methods, a couple dozen nicely achieved passages scattered through the book about his daily routines—but not much of this has the inky-fingered feel of actual labor at the drawing board.

In contrast, her recitation of Addams’ adventures with the opposing sex seems as exhaustive in its catalogue of conquests as it must have been exhausting for Addams to live through. Addams dated a lot of women and had sexual relations with many even during his marriages. And in the twenty-four years between Barbara Barb and Tee Davie, he logged time with such notable actresses as Greta Garbo, who once traveled with him on a holiday in Barbados, and Jane Fontaine, who, it was widely rumored for a time, the cartoonist was destined to marry. He didn’t.

Addams’ datebook shows that he was squiring Jackie Kennedy around town three months after JFK’s assassination. He, however, was not rich enough to sustain that relationship. And she, it seems, was something of an insensitive snob. She never regarded him as husband material, Davis says. “Well, I couldn’t get married to you,” she exclaimed one time; “what would we talk about at the end of the day—cartoons?” It was a put-down that “crushed” Addams, Davis says.

Their relationship was probably not sexual, Davis thinks. But most of his women friends were in bed with him at one time or another. Astonishingly, they all knew of each other’s peccadillos with Addams and remained friends with him, and with each other. One exception involved a young woman named Megan Marshack, who lived in the same building as Addams. He’d noticed her but had done nothing until Nelson Rockefeller died. Scandalously, Rockefeller, it was slowly revealed, died of a heart attack while “visiting” Marshack, who was his assistant on various book projects. Addams was soon boasting to friends that he “was in the sack with Megan the day after Rockefeller died.” This relationship between the 67-year-old Addams and the 26-year-old Marshack continued for about a year until Tee Davie, who was becoming more and more indispensible to Addams’ happiness even though she traveled abroad a great deal, told him to cut it out. Within months, Marshack disappears from Addams’ life, and he and Tee were married.

Addams emerges in Davis’ narrative as a man who loves women in a companionable as well as sexual way. With Addams and women, it wasn’t just sex, according to Tee. “Charlie had a true interest in women as friends,” she said. “Where another man would be wondering, ‘Can I get her into bed?’ Charlie would be thinking, ‘Now here’s an attractive person. I wonder what her story is.’”

Davis returns often to Barbara Barb, the femme fatale and pervasive villainess in the book, because the woman haunted Addams after their marriage. When, on business, she came to this country from England, she often stayed with Addams. Or he with her in her hotel. All of this extra-conjugality took place despite her plundering of his life and fortune. Addams’ lawyers constantly warned him about documents that Barb presented for his signature, but he always signed them—even though he knew he was giving her things he shouldn’t. He seems a genuine patsy. Or, as I say, a man who loves women—in the case of Barbara Barb, too well.

Hampered by an inability to understand or to articulate an understanding about cartooning, Davis nonetheless has produced a highly readable and entertaining biography of one of the medium’s legendary practitioners. She quotes from Addams, his record books, and his friends’ recollections about his antics, and then—cherry-picking just the right bon mots to drop into her narrative at just the right moments to enhance its flavor, like nutmeg on high octane eggnog—she meticulously integrates all the fragments into a lively and cohesive story, as brilliantly illuminated by, as it revealing of, the personality of her subject. The narrative is so enlivened by quotations that it becomes a long conversation with Addams and his friends, a triumph at revelation. We get to know Addams pretty well, and we can’t ask much more of a biography (even though it would have been wonderful to know more about how Addams wielded a brush or interacted with other New Yorker regulars).

Davis reminds us more than once that Addams looked a lot like Walter Matthau, and by mid-way in the book, Addams was always Matthau in my mind’s eye, the Matthau in the movie “Hopscotch”—an easy smile, warm, supremely competent and self-assured, humorous and not macabre. I see him that way when reading Roger Angell’s farewell to Addams in The New Yorker:

“Charles Addams was a tall, quiet, silver-haired man with a commanding nose and a courtly manner. He was grave and gentle by habit, but when he laughed, his face caved in around a chasmed, V-shaped grin, and he shook [silently] with pleasure. He was not introspective about his cartoons, and he turned away from questions about his art—where it came from, how he did it, what it meant. He did his work with serene authority; there was no thrashing about artistically. He seemed shy, but he loved company and had a great many friends; men and women were drawn to him. ... He was elegant and uncontrived.”

Said Sheed, who knew Addams well: “If you had only the drawings to go on, you couldn’t imagine calling him Charlie; but if you ever met him, you couldn’t imagine calling him anything else. And if I had all day, I couldn’t describe him better than that.”

Addams was also, incontestably, the cartoonist who invented the Addams Family. Awful things were reportedly hilarious to him, and he tended to giggle at funeral orations. But he was mildly annoyed, Davis tells us, by people focusing, as Davis must, on the dark side of his humor. “I’m sick of people calling it macabre,” he said. “It’s just funny, that’s all.”

Okay: funny. That’s all.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bibliography. Most of the chief aspects of Addams' life are rehearsed in the obituary in The New York Times for September 30, 1988. Additional information can be found in Current Biography 1954, in The New York Star Magazine (September 19, 1948), in The Saturday Review of Literature (November 11, 1950), and in Brendan Gill's Here at the New Yorker (1975). His famous family of lovable monsters was turned into a television series, "The Addams Family," 1966-1968, and a movie, “The Addams Family” (1991) and its sequel, “Addams Family Values” (1993). A Broadway musical debuted in the spring of 2010. Addams' cartoons are reprinted in The New Yorker anthologies of drawings and in collections: Drawn and Quartered (1942), Addams and Evil (1947), Monster Rally (1950), Home Bodies (1954), Nightcrawlers (1957), Dear Dead Days (1959), Black Maria (1960), The Groaning Board (1964), The Charles Addams Mother Goose (1967, not so much reprints as original work created expressly for the title), My Crowd (1970), Favorite Haunts (1976), Creature Comforts (1982), and a posthumous compilation, The World of Charles Addams (1991), the contents selected and arrayed in chronological order by his widow. Most recently, an elegant volume from Pomegranate, The Adams Family: An Evilution (2010), relies upon the Foundation’s archive of original Addams art for cartoons, roughs, and miscellaneous drawings for a “history” of the Addams Family, arranged by character rather than chronology.