INSIDE THE 24-HOUR COMIC: The Ordeal and the Ecstasy

Featuring the Boring Blow-by-Blow Account

of How I Tried to Scale Everest but

Got Only as Far as the Matterhorn,

Cheating on the Way but Didn’t Meet the Challenge

A Mini Meta-Maus with Mutt and Jeff Instead

(If It Works for Art Spiegelman, It Works for Me)

Plus: A Self-fulfilling Prophecy Fulfilled

IT’S BEEN ABOUT 30 YEARS since I abandoned an incipient career as a magazine gag cartoonist, and about all the cartooning I have done since is an anyule greeting card—all single panel stuff with no sequencing or storytelling of the typical comics sort. Years ago, cartoonist Scott McCloud told me about the 24-hour comics challenge, and I was intrigued but never wanted to take the time to do it. When the challenge was issued in Denver in early October at the comics shop I frequent, I had the time—and the inclination—so I jumped in.

My 24-hour comicbook story, “Waiting for Gotcha,” appears down the scroll after a turn or two; and we’ll get to the ordeal of producing it in a trice. Before that, let’s review what a “comic” is; and before that, we must acknowledge Scott’s invention.

Scott’s father was an inventor, and Scott is proud of carrying on in the paternal tradition. He invented a theory about comics that he has elaborated into several books, beginning with Understanding Comics in 1993. Scott’s theory begins with his definition of comics: juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence.

About the same time that Scott was writing his book, I was writing one of my own, The Art of the Funnies, in which I offered my definition of comics. As it subsequently evolved, I described comics as consisting of pictorial narratives or expositions in which words (often lettered into the picture area within speech balloons) usually contribute to the meaning of the pictures and vice versa. A pictorial narrative uses a sequence of juxtaposed pictures (i.e., a “strip” of pictures); pictorial exposition may do the same—or may not (as in single-panel cartoons—political cartoons as well as gag cartoons).

My definition (admittedly more tediously long-winded than Scott’s admirably succinct formulation) includes some products of the cartoonist’s artistry that Scott’s does not—those single-panel cartoons. His definition includes things that mine does not—the Bayeux Tapestry, Mexican codices, the Stations of the Cross. The essential element of Scott’s definition is sequence; the essential aspect of mine is blending. In Scott’s, almost any sequence of images qualifies as comics; in mine, words and pictures blend to achieve a meaning neither alone without the other conveys.

Scott’s

definition relies too heavily upon the pictorial character of comics and not

enough upon the verbal ingredient. Comics uniquely blend the two. No other form

of static visual narrative does this. Scott includes verbal content (words, he

allows, are a kind of imagery), but it’s the succession of images that is at

the operative core of his definition. In the accompanying visual aid, I try to

make the distinction visually by elaborating upon the logotype that Scott

developed to illustrate his definition—the little man, who tips his hat in a

sequence of two pictures.  I rush in to note, however, that regardless of emphasis,

neither sequence nor blending inherently excludes the other.

I rush in to note, however, that regardless of emphasis,

neither sequence nor blending inherently excludes the other.

In the expression “24-hour comic,” the word comic takes on another shade of meaning: it refers to a comic book as distinct from, say, a newspaper comic strip. The 24-hour comic, then, is a long-form comic strip, a paginated version of sequenced blends of words and pictures.

Another of Scott’s inventions is the 24-hour comic. In fact, he probably invented the 24-hour comic before he invented his theory of comics. The moment of inspiration occurred in the summer of 1990 as he was watching his friend Steve Bissette, also a comic book artist, doing sketches at a book signing in a Cambridge bookstore. Steve is notoriously slow at producing comic book art—allegedly taking a whole month to do one page—but he was astonishingly fast at doing sketches for fans. Scott watched and marveled: “Why would this guy have troubles with deadlines? He’s an incredible draftsman! I’ll bet he could do a full-length comic in a day if he wanted to.”

The lightbulb went off over Scott’s head: “Suddenly, I knew what Steve needed to do. And I knew that I could get him to do it only if I did it, too. Thus the deal was struck: Steve and I made a mutual vow that we would each do a complete 24-page comic in a single day at some point before August 31.”

Scott did his on August 31, having procrastinated as long as the calendar permitted; Steve did his on August 36th (i.e., September 5).

Dave Sim, who was self-publishing his own comic book Cerebus from Kitchener, Ontario, was sent copies of the two 24-hour comics. Intrigued, he did a 24-hour comic of his own and published “previews” of his and Scott’s and Steve’s in an issue of Cerebus. The word spread, and more and more cartoonists bellied up to their drawingboards to try to meet the challenge: to create a complete 24-page comic book in 24 continuous hours. A very simple rule.

“That means everything,” Scott elaborated in his 2004 compilation, 24-Hour Comics, “—story, finished art, lettering, colors (if you want ’em), paste-up, everything! Once pen hits paper, the clock starts ticking; 24 hours later, the pen lifts off the paper never to descend again.” No advance preparations are permitted—no sketches, designs, plot summaries or the like.

But there are loopholes for fudging. Although the 24 hours are continuous, consecutive, naps are permitted. Visits to nearby restaurants likewise. But the clock goes on ticking. “If you get to 24 hours and you’re not done,” Scott advises, “either end it there (the Gaiman Variation) or keep going until you’re done (the Eastman Variation).”

Neil Gaiman hadn’t drawn anything in 14 years when he made his attempt. More writer than artist, he filled lots of panels with lettering, which was time-consuming for a person not recently versed in the skill, and when he saw his time was almost up, he concocted a conclusion on his thirteenth page. Kevin Eastman couldn’t finish in 24 hours: he went on for another 26. Scott considered both such efforts “Noble Failure Variants,” true 24-hour comics in spirit because their perpetrators “sincerely intended to do the 24 pages in 24 hours at the onset.”

I managed both variants—I went beyond 24 hours with fewer than 24 pages. The noblest failure of all.

I HADN’T DONE ANY STORYTELLING in cartoon form for over 40 years, so I was hesitant about whether I could manage a story—or, for that matter, even think one up. So I decided to use Samuel Beckett’s celebrated absurdist play Waiting for Godot as a narrative framework: it’s open ended and permits walkons by any number of extraneous characters so it could host any stray notion that might waft through my head. Nothing happens in Beckett’s play at various intervals that effectively consume the whole thing, so if I was unable to think of anything to happen in my mock-Godot, no one could complain: in fact, I’d be perceived as successful in the midst of failure, always an admirable objective.

Once I’d landed on Godot, I knew I could work political allusions into the story: Beckett denied a frequent interpretation of Godot as “God,” but Godot is at least “the one” being waited for—akin to whatever magician the Republicans might finally choose to unseat Barack Obama. Obama was also dubbed “the one” by Oprah in the 2008 campaign. As the 2012 race for the White House heated up on GOP turf, there seemed to me to be plenty of candidates that could walk on stage and be mistaken for Godot.

But I didn’t want to use “Godot”; so I modified the name to allude to what might be the ending of the tale—the “gotcha” that comes when you’ve fooled someone into paying attention or looking to see if his fly is open.

At first, I thought I’d use characters from the unsold comic strips I’d devised in the 1960s to enact the roles of Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon (Didi and Gogo). But then I hit on the notion of using slap-dash impersonations of Bud Fisher’s iconic Mutt and Jeff. I also thought I’d include other famous comic strip characters—Blondie, for instance; although at the time I started toying with the idea, I didn’t know what her role might be.

That’s about all I had in my head to start with—Vladimir and Estragon (Jeff and Mutt) and the barren tree they sat under in the midst of a blasted plain, a political walkon or two, perhaps a menacing monster (in the tradition of superhero comics), the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm and Barack Obama up to his knees in a puddle. And the brick.

I thought of using the brick because the hurled-missile-to-the-head was first deployed in Mutt and Jeff , not in Krazy Kat as popularly supposed, and that led me to Krazy—and the history lecture on page 3. At this point in this harangue, you should probably stop reading these painfully expository paragraphs and read “Waiting for Gotcha,” which starts right chere.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IN DEVISING HIS FAMED BRICK DEVICE, cartoonist George Herriman was importing into his comic strip a vaudevillian maneuver: in the stage routines of comedian duos, one comic often expressed exasperation at his partner’s idiocy by hitting him with a slapstick or a fist. Maybe that’s where we get the term “punchline.” The fist to the top of the head could just as well be a pie in the face or a brick to the noggin. So when Herriman’s Ignatz the mouse kreases Krazy Kat’s kranium with a brick, he’s enacting a theatrical ritual.

But the ritual in comic strips was first performed by Mutt, who hit little Jeff on the head anytime Jeff said something silly (which, being a fugitive from an insane asylum, Jeff often did). I wanted to get this little corrective scrap of comics history into my 24-hour comic.

On Saturday morning, October 1, I took my drawing equipment (pencils, rollerball pens, gray markers, a pad of drawing paper and a ruler) to the I Want More Comics shop, where the gaming room had been set aside for us 24-hour conquistadors, numbering about a dozen. (Another dozen paladins assembled at another Denver-area comics shop, Enchanted Grounds; altogether 28 people made the attempt, and 22 completed the exercise, although not all of them finished 24 pages. The Colorado Alliance of Illustrators, a not-for-profit organization, was running the event, which was otherwise sponsored by CGX Publishing Solutions, which printed a book of the comics done during the weekend, and the two store sites plus Quiznos Subs of Northglen, Gypsygirl Press, and Squid Works, the book’s publisher and sales outlet at www.squidworks.com.)The Squid Works’ Stan Yan, who convened the IWMC bunch, explained to me the rules (the nuances of which I hadn’t previously known), and I started a few minutes after noon.

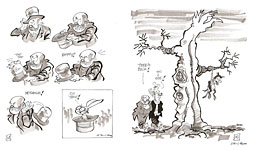

I’d already composed my first page in my head—a splash panel scene-setter, then a couple panels introducing Jeff and Mutt in the “nothing is happening” mode of Waiting for Godot. When I finished, I looked at my watch and was alarmed to see that it was now 1:15 p.m.: it had taken me 65 minutes. At this rate, I’d be working all 24 hours to complete the comic. And I’d planned to go home that evening and get a night’s sleep, thinking, with the arrogance of age and vaunted experience, that I could do 24 pages in less than 24 hours. If I still wanted to do that, I’d have to speed up.

Alas, I was never able to do much better: almost every page took me an hour to complete, from pencil to inks to gray tones.

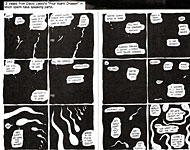

As I drew the opening page, I was still pondering how I’d get to the brick on the next page. I knew I wanted to get Krazy’s brick into the story by having it thrown across panel borders, but I couldn’t think of a way to fit that action into the layout of a single page. I needed a setup that would prompt either Jeff or Mutt to throw a brick at the other in exasperation. Beckett’s characters were periodically afflicted by doubt about the impending arrival of Godot, and that circumstance seemed sufficient to my needs. I picked Jeff to be the provoked one who would throw the brick because he was the smaller of the pair and therefore echoed Ignatz the mouse’s role in Herriman’s masterwork.

But I still couldn’t think of an arrangement on a single page that would permit me to have the thrown brick cross panel borders on that page. For that to happen, the brick in flight would have to intrude into a panel of the setup sequence, and I couldn’t think of any sensible explanation for the intrusion. Moreover, I was running out of room on that page. So, plunging ahead (the clock was ticking by now), I finally thought of ending the sequence with the brick being tossed from one page to the next.

Until that moment of inspiration, I didn’t know how I’d get into the story an explanation of Mutt and Jeff’s inaugural brick. But once the brick left one page for the next, I had a scene-changer (the end of a page in a comic book often serves that function) that seemed to provide an opening for insinuating myself into the story. How or why that occurred to me, I dunno. I hadn’t imagined a part for me to play in the tale until this moment. Perhaps I “arrived” on the scene like this: since it was “I” who wanted to discuss the Mutt-Jeff precedent, it was therefore inescapably logical that “I” show up to do the discussing in the comic.

As a plot device, the maneuver clanked wonderfully in keeping with the Godot ambiance, and as we moved from one page to the next, it seemed (by some comic book cogency) natural that we’d move from the realm of the imaginary (Mutt and Jeff’s Gogo and Didi realm) to the realm of the “real”—me in my “studio.” And to emphasize visually the change in venue, I didn’t use any gray tones as much in rendering the “real.”

The rabbit, by the way, is my dingbat, a signature device like editoonist Pat Oliphant’s penguin, Punk; I call the bunny Cahoots, but that’s not his name. His name, as anyone who remembers the James Stewart movie will realize, is Harvey. He gets all the best laugh lines.

I gave myself a pipe as a prop for the lecture itself: I don’t smoke a pipe anymore, but by sticking one in the sequence, I provided some visual interest (lighting the pipe) to accompany the dull verbiage—then I thought of the “fog” as a punchline, a visual-verbal joke. And that led to the last panel on the page. Having established my character’s penchant for self-important pontificating, I’d set the stage for Krazy to make a cameo appearance: he’d do what his nemesis Ignatz usually did—express exasperation at my sermonizing by hitting me with a brick.

That ended the sequence, and the turning of the page moved us into a different scene, a return to Mutt and Jeff and the lonesome tree.

BY THE TIME I FINISHED the third page—three hours into the 24—my back had started aching, and when I tried to stand up, I staggered. My legs were almost numb. At the age of 74, I shouldn’t have been surprised that I get stiff if I stay in one position too long, but I was nonetheless surprised, so deeply was I engaged in my Beckettean world.

And nothing distracted me from my profound emersion. I had supposed that this temporary atelier would bubble with boisterous exchanges among the participants and be filled with loud music, flung erasers and, even, the singing of bawdy songs. But no—it was instead the quietest place I’d been all week. Tomb-like. One other artist came by and looked over my shoulder while I was doing the third or fourth page, murmured that he liked my style, then returned to his labors. Otherwise, we all toiled away in complete and isolated silence. Well, some of the others were plugged into iPods or other audio amusements, but they weren’t dancing or gesticulating in rhythm, so silence prevailed. Eerie.

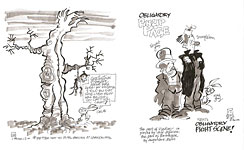

I don’t know how I decided to give the dead-seeming tree a leaf, but it was a useful momentary diversion, and putting Mutt and Jeff under the tree got us back to the main thread of the Godot narrative, which was my rationale for this page; the leaf arrived at the last minute. Page 5 seems somewhat wasted, an irrelevance, but it re-establishes the Godot atmosphere and thereby sets up for the arrival of Roy Crane’s Captain Easy on page 6.

The Captain Easy legacy was another aspect of comics history I wanted to expose. Soon after Easy arrived in Crane’s Wash Tubbs in May 1929, the jut-jawed soldier of fortune stole the show from pint-sized Wash. Easy was popular enough by the mid-1930s when Jerry Seigel and Joe Shuster were producing their comic book feature “Slam Bradley” that Shuster aped his physiognomy when designing Slam. Slam Bradley also had a pint-sized sidekick, echoing the Easy-Wash relationship. Then when Shuster designed Clark Kent/Superman, he simply re-tooled Slam, combing his unruly hair whenever Superman assumed the guise of Clark.

The crow at the bottom of the page is the remnant of an idea I abandoned when I realized I was running out of time. He was going to morph into a huge beaked monster for a couple pages, and I’d lavish quantities of gaudy artwork on the pages by way of emphasizing the visual nature of storytelling in the medium. But by the time I got to Sunday morning, I was too tired to contemplate doing all that much drawing.

I had to get Easy out of there, and I resorted to lame wordplay to do it. By then, I’d thought of a way Blondie could be worked into the sequence: I’d planned, vaguely, to put a pin-up into the story, and she filled the bill. A cartoonist friend of mine, Frank Cho, had devised a comic strip with a voluptuous heroine, and his syndicate kept telling him to de-emphasize her figure. Cho usually responded by telling his editors to look at Blondie, who, as any examination reveals, has a chest that is more than adequate for a demure housewife. I took Frank’s observation to a gaga extreme. Then ended her walkon by having her choke on the mic, something it always seems to me about to happen to performers who have their mics so close to their tonsils when singing.

I was putting time notations on each page, recording the time I started drawing the page and when I finished it. By page 7, the page before Blondie Gaga, I was into the evening and I was at home.

BY SIX O’CLOCK, I’d finished six pages. I was hungry. The pervasive silence was starting to get to me. I was in a room full of zombies. I had to get away. By then, I knew that I wasn’t going to be able to complete 2-3 pages an hour, which would have generated enough pages that I could take the evening off: with 15-16, even 18, pages done, I could go home, have dinner, watch tv and get a full night’s sleep and still finish the remainder of the 24 page requirement the next morning.

But as I worked through the afternoon, replicating the time-expensive experience of the first page, I was quickly persuaded that my assessment of my ability had been pretentiously inflated: I hadn’t done enough sustained cartooning in 40 years to impart accuracy to my prognostication. I was doing only a page an hour. At that rate, if I could keep it up, I’d finish 24 pages in 24 hours, but I knew I couldn’t stay up for 24 hours. Just six hours into the exercise, I was worn out and hungry.

So I went home and had dinner as I’d planned. But by then, I was also hooked on the challenge: I wanted to come as close to 24 pages as I could. I worked through the evening and into the wee hours. By 2 a.m., I had a terrific backache. My eyes had glazed over. My arm was in a sling and my fingers were in splints. My nose was running and my feet smelled.

And with that, I suddenly realized the problem: I was built upside down.

Moreover, I’d had run out of ideas. So I went to bed, planning to arise at 6:30 a.m. and finish what I could.

I had reached page 16, and I had the story’s conclusion in mind—the GOP elephant, caricatures of Mitch McConnell and John Boehner and Obama in the puddle, probably another 2-3 pages. But I couldn’t think of how to get to the elephant. Too tired. Head dead. I went to bed, knowing that I could probably finish the 20th page the next morning, but not the 24th.

HAVING ESTABLISHED THE WALKON as a plot device, I did another one on page 9. I had contrived a caricature of Mitt Romney a few days before so I used it here as an intimation of coming events: one politician on the scene would suggest that more were in the offing. I used Romney rather than any of the others because I had a Romney joke, which I appropriated from a radio talk show I’d been listening to a few days before. And my Romney caricature was better than Michele “Crazy Eyes” Bachman’s or Rick “Pecos” Perry’s.

Where the idea for the falling leaf came from I have no idea. It was never part of my initial concept, foggy though it was; neither did it occur to me when the leaf first showed up on page 4. But suddenly, the leaf was falling. That super-sensitive little Jeff would be alarmed seemed natural. As I drew page 10, I visualized the next page with Jeff being so upset by the leaf’s falling that he screams a silent scream. How to depict that?

Finger-pointing implied alarm without sound. Two fingers pointing emphasized the hysterical state of his mind. Not just “look” but “LOOK! LOOK!” At the last minute, I thought of using dashed lines for the emanata radiating from his head. (Emanata is a highly technical cartooning term invented by Mort Walker.) The broken lines seemed to suggest silence, hence, a scream trying so hard to become a shriek that it fails to make noise.

The tree falling down on page 12 was the inspiration of the moment: struggling with the silent scream, I thought, “What could happen next?” The tree, now denuded of its only leaf, was lifeless; dead, it should fall down. Logical. Dead things don’t stand up.

My only reservation: how to draw it? How to depict a suddenly falling tree? You see my solution. I think it works. I liked the timing, too: from Jeff’s silent scream at the falling leaf, we turn the page and—presto!—the whole tree falls. The maneuver makes dramatic use of the genre’s pagination: after ending one page, turning to the next is the equivalent of raising the curtain on the next scene, the more startling, the better.

The fallen tree surprises and distresses Jeff. With a gesture in the bottom panel, Mutt hopes to get Jeff to suppress any untoward emotional outburst: don’t move, don’t speak. That restraints Jeff momentarily, but then on page 13, he collapses on the tree trunk and weeps.

Incongruously, Mutt takes his boot off and looks into it. For what? Who knows? It’s taken directly from Beckett. As is Jeff’s looking into his hat on the next page. And having opted in this direction in imitation of Beckett, I knew my rabbit would pop out of that hat. The magical inspiration of an analogous train of thought: hats, magicians, rabbits. What else would you find in a hat?

I can’t remember when it occurred to me that Krazy would wind up hanging from the tree. But it was before the tree fell down, or maybe as it fell down. I realized at the time I decided to topple the tree that it would have to sprout up again in order to serve as Krazy’s gallows. How to manage that? Magic. Just have it return. “Tree’s back,” as Jeff says.

Days after I’d finished the story, it struck me that the magical reincarnation of the tree mimicked and hence ridiculed a common occurrence in superhero comicbooks: a fan favorite character dies amid much industry-wide ballyhoo, but then—six months later—the character comes back to life, accompanied by an elaborate pseudo-scientific explanation. The tree episode, then, would have been a brilliant satirical comment on superhero comicbooks. Maybe it still is. But that’s not how it came about. It came about because I needed the tree in order to hang Krazy from it.

Reaction to Krazy hanging there? Couldn’t think of anything funny, so Mutt just says, “So I see.” Laconic. Almost as if he doesn’t see the Kat korpse. And his obliviousness has a reverse effect: by not mentioning the obvious, he makes it more obvious. Or so it seems to me, now, in retrospect.

Cahoots’ comment on page 16 could have been made on page 15, but I decided to postpone it so the awful impact of Krazy’s hanging could sink in. Then the reason for his execution—which I didn’t think of until after drawing page 15—seemed another extension of the internal logic of the story. My wife protested my killing the Kat, but, again, that seemed somehow foreordained: Krazy konked me on the head earlier, and now, craven cartooner that I am, I’m wreaking revenge. A lame rationale, I suppose; but I couldn’t think of a “nine lives” gag that appealed to me. The one I gave to Cahoots to spout didn’t seem strong enough. Nor did it actually explain the hanging.

Besides, duplicating page 15's picture on page 16 was a fast way of toting up another page: I just traced the tree and the Kat. Took 15 minutes, as you can see from the time notation. Page 16 was the last page I did before falling into bed, exhausted. And you’ll notice (how could you not?) that I’m spending much less time on each page: I did 10 pages Saturday evening from 7:45 p.m. until 2 a.m.; 10 pages in 6-1/4 hours, or a page every 38 minutes. Better than the afternoon’s record.

But not good enough soon enough. Falling asleep, I decided to use a preliminary drawing of Mutt and Jeff that I’d done a day or so before the 24-hour challenge commenced. Page 17, then, is a cheat. I didn’t think it was cheating at the time. At the time, I was ticking away like the clock, and in the syncopation of the moment, I (as I too often do in such situations) lost my head while all those around me were keeping theirs. I forgot the rules of the game because I was thinking of something else: I wanted to get to 20 pages, which, divisible by 4 and by 2, would make a 5-signature booklet or 10 2-page spreads for my online magazine.

By then, I’d also envisioned pages 18 and 19, which would get me to the story’s political conclusion that I’d had in mind for several hours, and I’d discarded the idea of having a huge beaked monster appear to threaten hapless Didi and Gogo. I was too tired to do all the artwork that would justify the monster’s appearance.

AS I NODDED OFF TO SLEEP at two o’clock Sunday morning, the whole enterprise seemed a better achievement than it was. A 20-page comic! Done in a day! Big whoop! At the time—and, indeed, for several hours after finishing—I didn’t realize how the entire effort had deteriorated. Half of my comic book consisted of short-cuts: ten of the twenty pages were full-page gags.

Obviously (although not to me until, as I say, later), a page that’s just one drawing takes less time to complete than a page with several panels on it. The last six pages were all full-page drawings. Five of the ten full-pagers were pictures of the same blasted tree. No wonder I was finishing pages at the end faster than I’d been finishing them at the beginning.

At least eight of the ten full-pagers were entirely legitimate deployments of the form. A full-pager is an exclamation point, a shouted punchline, a startling visual development. Page 4's tree sprouting a leaf, page 8's Blondie Gaga, and the 2-page horror when Jeff watches the leaf fall, Obama’s sudden appearance, standing in the puddle—even pages 15 and 16—all are dramatic and therefore justifiable uses of the full-page narrative device. Moreover, the full-pagers of the first four instances just cited come at the turn of a page: after an appropriate setup, we turn the page and—Wham!—a revelation, a joke, a punchline! The two-page falling-leaf horror, with one page duplicating the page that faced it, emphasizes the visual drama by repeating it. In effect, it is a slow-motion sequence: slowing the action enhances the effect.

For these pages, I was clearly gripped in the momentum of the medium, going with the flow, plunging through the form, doing setups and exploding gags. No apologies needed for any of these. But by the time I got to the 3-page sequence beginning with the Obligatory Pin-up Page, I was rattled. I was spinning out full-pagers with my eyes on the clock. I wanted to get done.

Okay, portraying the big elephant probably justifies using a whole page, but the next page is a short-cut without excuse: it could have been combined with the elephant page, with the elephant larger, rampaging, bearing down on Jeff and Mutt. But that scene would require more careful drawing with perspective and scale. Separating the action into two full-pagers simplified the task. And it got me one page closer to the 20-page product.

I’m scarcely the only cartoonist who finished the 24-hour challenge in a flurry of short cuts. Gaiman’s tale in the 2004 24-Hour Comics book ends with a series of nearly blank panels (and Gaiman finished only 13 pages). Like Bissette, Gaiman also resorted to using solid black pages with minimalist white-line drawings. Nicely dramatic but, still, simple—fast!—full pagers.

|

|

|

SUNDAY MORNING, I got up at 6:30 a.m., had breakfast, and added gray tone to the 10 pages I’d finished the night before. I later decided that adding gray tone increased the time I spent on each page: patently obvious, I realize—any fool could see this humble truth (I saw it)—but I hadn’t realized it until after I was done. I was drawing, drawing, drawing—not thinking about logistics. In my imagination, adding gray tone took only a couple minutes; in actuality, it probably added 10-15 minutes to the time it took to do each page.

I’d slipped into using gray tone by accident: my original plan was to use gray markers in lieu of pencil for the preliminary sketches that I’d then ink. That would give an added dimension to the pictures. But after a couple of experiments in this direction, I saw I wasn’t getting the visual effect I wanted, so I went back to penciling but retained the gray-shading idea.

The other thing that was taking more time than I thought it would was inking. I was using a line that waxed thick and waned thin. Starting with the thin line, I fattened it up by going over the intended thick parts of it again and again with my pen. The pen took time. When I used a brush (on pages 9 and10), the inking went much faster. But I liked the double-line appearance of the pen-inked drawings, so I persisted with a time-consuming technique.

I penciled pages 18-20, then took everything back to the comics shop to finish. I got there at 11:30 a.m. Sunday morning and finished, as you can see, at 1:20 p.m. I’d failed the challenge. I did only 19 pages and, discounting the time I ate, slept, and drove back and forth to the comics shop, doing those pages took me only 18 1/4 hours, less than the target time, but I hadn’t finished within the prescribed 24 hours. Too few pages; too much lapsed time.

Had I stopped at the tick of the 24th hour, I would have achieved what McCloud calls “the Gaiman Variation”—an incomplete comic (less than 24 pages) but done within the time limit. But the resulting 18-page story would have had no proper ending. I chose to end the story, satisfying “the Eastman Variation”—a completed story but not done within 24 hours.

The time notations on the last three pages no longer indicate the time I spent on each page. I wasn’t completing each page before going on to the next: I penciled all three, then inked them at the comics shop. The notations, then, indicate when I started penciling each page and when I finished inking and toning.

Page 17, the cheat page, gave me a bridge to the rest of the “story”: the “obligatory pin-up page” is followed by the “obligatory fight scene.” And the fight is entirely subliminal: by introducing the GOP gang, I intimate the struggle with the Democrats. Page 18 had been lurking in my mind since the previous afternoon: I like drawing elephants and I wanted to use caricatures I’d been hacking away at for McConnell and Boehner. I’m still not entirely happy with the results, but I think I managed to get McConnell’s doughy visage approximately right; Boehner, who is quite handsome, is more difficult to caricature.

Page 19 ties all the previous threads in a knot that will tighten on the last page. The remnants of the monster reside in Jeff’s speech, and although the elephant doesn’t serve the purpose I’d envisioned for a beaked BEM, a pachyderm is, in a manner of speaking, a monster. Mutt revives the notion of “the one”—Godot and/or Oprah’s Obama—setting up for page 20.

Whereupon all the pieces come together in a mocking crescendo. “The one” is revealed as Obama. And we see at once that he cannot walk on water, expectations to the contrary notwithstanding. So maybe he’s not “the one” after all. I wasn’t sure that his inability to water walk would be evident so I had Cahoots say the obvious. Then I added a couple footnits and signed off, 25-1/4 hours after starting.

DRIVING HOME AFTER I FINISHED, I pondered the over-all implications of what I’d done, and it seemed to me that reversal is a dominant theme. I had no such notion at the start, but as I thought about it afterwards, I saw several reversals: the personalities of Mutt and Jeff are reversed, Mutt being the compliant one; and Jeff throws the first brick instead of Mutt; similarly, Krazy throws the brick instead of being hit by it, and Blondie is a flamboyant stripper/singer rather than a demure housewife (Blondie started as a flapper, after all—and it’s time someone acknowledged that her figure, despite her conservative wardrobe, is spectacular enough to go on stage).

Taking the reversal theme a step further, the cumulative implication is that if Obama is depicted as a failure, that, too, is a reversal: he’s actually a big success, or would be if it weren’t for the Repubs, whose only goal in governing is to deny him a second term.

As I say, I had no idea that a reversal theme would knit so many pieces together so handily (if, in fact, that’s what’s happening).

Although I’d failed to meet the 24-hour challenge (and blithely cheated en route), doing a comic book story from scratch, with only vague notions floating on the surface of my banal brainpan at the start, the experience was something of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Not surprisingly, given my biases and proclivities, it demonstrated afresh that conviction I’d long held about cartooning—that in comics, words and pictures blend to achieve a meaning (often humorous) that neither words nor pictures convey alone without the other.

This notion I’ve offered not so much as a criterion for measuring excellence (although many have taken it that way) but as a “way in” to appreciating comics: looking for the interdependence of the verbal and the visual nudges the observer into seeing the narrative function of the pictures, too often overlooked because the “story” (the sequence of events and actions) prevails. As it should. But looking for the ways words and pictures blend to tell the story seems to lead to an understanding of the artform as a visual as well as a verbal enterprise. We easily accept the literary notion that words tell stories; finding a verbal-visual blend in comics persuades us that pictures carry a share of the storytelling too. Many critics overlook this aspect of the art of comics. If they talk about the artwork at all, it is to rave about art as art, overlooking the storytelling that it does.

So I was happy to see how much of my story blended words and pictures for narrative as well as for comedic effect. Happy but not surprised. That’s how cartoonists think, after all—in blends of words and pictures—and I still fancy myself a cartoonist, despite all the verbal effusion of these paragraphs.

I was also delighted to realize that several of my pages perpetrated the story “silently,” with pictures alone. For me as a sometime cartoonist, making pictures has always been the reason I did cartoons.

I had a lot of fun cartooning again after a 30-year hiatus. Just as important, though, I learned a lot doing my 24-hour comic. Or maybe it was re-learning in a state of heightened awareness about how cartooning works. Storytelling in words and pictures creates a sequence that carries you along like a coursing stream: in its embrace, you lose all sense of everything around you: you are immersed in the story you’re telling and the verbal and pictorial means to that end. That’s what cartooning is all about.

Doing Waiting for Gotcha also reminded me anew that cartoon ideas are born in the drawing process. Ideas don’t necessarily come from the drawing itself, but from being engaged in the act of drawing. Drawing a character leads to thinking about the character, his/her personality, what he/she might do next, and the like. One thing leads unaccountably to another until you’re surrounded by a whole crop of visual-verbal ideas that you never anticipated having. They spring up like weeds. And if you’re like me, you have a great time running barefoot through the undergrowth. Here’s hoping my good time on these pages gave you a good time, too.

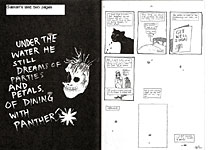

Assuming that might be true, maybe you, like me, are fascinated by how pictures come to be, so here are some of the pencil roughs that I made as I went along.

|

|

|

|

|

|