Ambassador

Extraordinaire

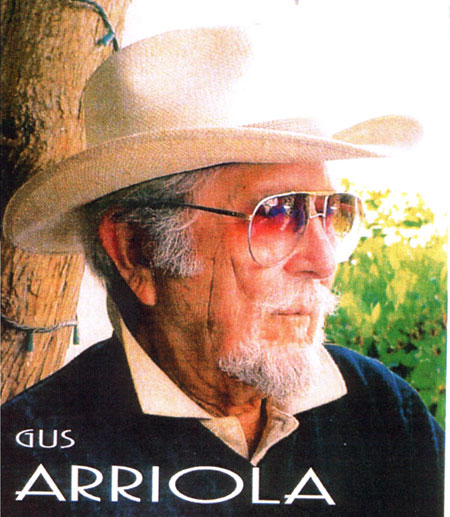

Gus

Arriola, 1917-2008

This

time, it’s personal: my friend Gus Arriola, creator of the

celebrated comic strip Gordo,

died on February 2 at 9:30 a.m. in his home in Carmel, California. At

the age of 90, plagued by Parkinson’s disease, fading health

and a growing cancer, he had declined further chemotherapy and for

the last couple of weeks was under hospice care. His wife of 65

years, Mary Frances, was with him.

Gordo, published in U.S. newspapers for forty-four years (1941-1985), was, during its run, the most visible ethnic comic strip in America and its creator the most visible American of Mexican descent working as a syndicated cartoonist. At its peak Gordo appeared in 270 newspapers and was the more widely circulated and longer-running of only two comic strips with a Mexican milieu. (The other was Little Pedro, a Sunday pantomime strip, by William de la Torre, which ran from about 1948 until 1955. It was offered by a small syndicate and never had very great circulation.)

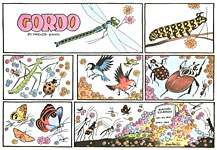

Gordo’s other distinction is that it was a stylistic tour de force, a triumph of design in cartooning. Arriola is revered (and envied) by other cartoonists and admirers of cartooning for the sheer quality of the art in the strip.

According to the late Jud Hurd, who, for thirty years, edited and published a quarterly journal about the cartooning profession, Cartoonist PROfiles, Arriola was enthusiastically envied by everyone in the inky-fingered fraternity. "He is one of the few cartoonists whose work other cartoonists drool over," Hurd once said.

Mort Walker agreed: "Gordo was an exceptional strip visually," said the creator of Beetle Bailey, Hi and Lois, and several other comic strips. "I was really charmed by his drawing," he went on. "And his Sunday page was a work of art. He seemed to indulge himself in creating new visual techniques to charm the eye. It was just a lot of fun to look at. I found myself not even reading it as much as enjoying the pictures. He is a superb artist."

Said Charles Schulz of Peanuts fame, "My admiration for the drawing that Gus puts into Gordo knows no bounds. Gus can draw anything. Better than that, Gus can cartoon anything, and there is a world of difference."

Hank Ketcham, creator of Dennis the Menace and a stylistic virtuoso himself, said this of his friend: "Gus is a terrific draftsman—and designer. His design was just so crisp and nice, and the color on Sunday was great. Today they've squeezed the Sunday size down to the nub, and it would be a shame to do that to his stuff."

Magazine and Mad cartoonist Paul Coker Jr.—another outstanding stylist—noted: "It's remarkable that without much art training, Arriola managed to make the strip far superior from the design and drawing standpoint to almost anything else in the papers."

The late Mark J. Cohen, a discriminating collector of original cartoon art, said: “When I’d read the Sunday comics, Gus’s work would leap off the page in a blaze of color and design reflecting the Mexican culture and art. Gordo is a celebration of life, a celebration of Latino culture, and a celebration of language. And Gus’s gentle humor was often loaded with social messages and comment without being preachy or political. I am in awe of Gus, not only as a cartoonist but as a human being.”

Cartoonists generally would agree with Malcolm Whyte, founder of the San Francisco Museum of Comic Art, who told Wyatt Buchanan at the San Francisco Chronicle that "Arriola's Sunday strips were a tour de force of rich, vibrant color, lovely line work and dazzling artwork—stunning pieces of art."

|

|

And all of that is true. But what is seldom realized is how gifted a storyteller Arriola was. Most of his reputation rests on the "design quality" of the strip during its last three decades, when Gus was cracking jokes in the strip rather than telling stories. That’s what most people remember. But before 1960, the strip was a thorough-going storytelling strip, week after week, month after month, year after year; and Arriola's humorous yarns were tantalizingly intricate, tiny details complicating a tangled skein until, at last, the cartoonist unraveled the mess by tying all the loose ends into a single tidy knot to end the tale. And many of the narrative details were entirely pictorial, little insights into personality conveyed with body language, say. Arriola was more than a master designer: he was also a master storyteller in his chosen medium.

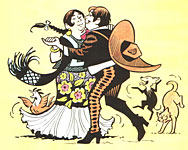

In the beginning, Gordo retailed the humorous adventures and amorous preoccupations of a portly Mexican bean farmer, Gordo Salazar Lopez, his perspicacious pint-sized nephew Pepito, the menagerie of their farm animals (Senor Dog, Poosy Gato, Cochito the Pig, and Popo—Popocatepetl—the gamecock), and the other citizens of their village. Among the latter were Juan Pablo Jones, a short fellow with a large nose and moustache and absolutely no desire to work; “the Poet,” Paris Juarez Keats Garcia, who shared Juan Pablo’s ambition; Pelon Pedilla, the owner of the cantina they all frequented; and the Widow Gonzalez, the most dangerous of the species—a classical Latin beauty.

Gordo’s avocation was chasing after the many beauteous senoritas of his village. And the Widow Artemisa Rosalinda Gonzalez’s self-imposed mission in life was to capture Gordo and lead him to the altar. As time went on, the Widow became wealthier and wealthier and therefore had more and more resources to pour into her periodic Gordo stalkings. She moved away from the village, but she returned every few years to prey again upon the hapless Gordo.

Another of the strip’s most popular characters was Halley’s Comet, the bus Gordo acquired early in the late 1940s. A hurtling semi-guided missile that brooked no obstacle, natural or man-made, in its path, Halley’s Comet was fueled with various kinds of alcohol, most of it potable.

Later,

Arriola added a equally formidable character in the person of Tehuana

Mama (Alicia Contreras de Ortiz), who became Gordo’s

housekeeper in whatever time she could spare from babysitting her

grandson, Trailing Arbutus.  Arriola had a gift for inventing memorable

names: a hip spider named Bug Rogers who spun decorative webs; a pair

of inebriated worms, Ponchito and Porfirio; the voluptuous Inocencia

de Ortiz, Trini the village witch doctor, the mute child Ponce de

Leon. The Poet’s burro was called, fittingly, Browning, and his

parrot was Kipling.

Arriola had a gift for inventing memorable

names: a hip spider named Bug Rogers who spun decorative webs; a pair

of inebriated worms, Ponchito and Porfirio; the voluptuous Inocencia

de Ortiz, Trini the village witch doctor, the mute child Ponce de

Leon. The Poet’s burro was called, fittingly, Browning, and his

parrot was Kipling.

Another stellar attraction was Mary Frances Sevier, a young girl from Texas to whom the cartoonist gave the name (and southern accent) of his own wife. The girl eventually employed a toweringly efficient butler named Ashmead (the name is that of a TV writer friend of Arriola’s, Ashmead Scott). About the comings and goings of this cast, the animal population (Arriola’s Greek chorus) always had somewhat satirical observations to make.

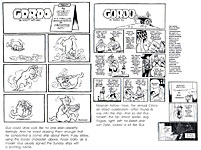

The strip had an unusual and interrupted history. Launched as a daily-only feature November 24, 1941, it was briefly discontinued on October 28, 1942, when Arriola entered the army. On May 2, 1943, Arriola started the strip again, this time only on Sundays. After the War, he resumed doing the dailies on June 24, 1946, and Gordo remained a seven-day strip until it ceased on March 2, 1985. Except for a brief 12-18 month period in the late 1940s, Arriola produced the strip single-handedly with only his wife as a sounding board for gag and story ideas. The run of the strip brackets almost 44 years, and Arriola’s seven-day servitude embraced 38 continuous, unassisted years. At the time of Arriola’s retirement, no one had matched his record; subsequently, only Schulz surpassed it.

When it started, Gordo was a comedic continuity, but in the late 1950s, Arriola began injecting long periods of gag-a-day runs between stories, and for the rest of the strip’s history, he alternated storytelling and joke-telling. Creating cunning continuities for a while and then gladsome gags for weeks, he achieved another distinction: no other strip had a publication pattern anything quite like it.

More by accident than by deliberate intention, Gordo evolved a cultural ambassadorial function, representing life in Mexico to its American audience. At first, Arriola’s depiction of his characters perpetuated the stereotypical imagery of Mexicans found in American popular culture and in Hollywood, where Arriola worked in animation after graduating from Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles in 1935. Eventually, however, Arriola realized his comic strip was one of the few mass circulation vehicles in the United States that portrayed Mexicans, and he began in the 1950s taking pains to reflect accurately the culture south of the border.

“Gordo

wasn’t my fault,” Arriola wrote in a newspaper article in

2006, “—not in the beginning.” Working in the

animation department at MGM, he had been assigned to develop some

characters for “The Lonesome Strange,” a spoof of the

Lone Ranger. “They wanted Mexican bandits, which were terrible

stereotypes then,” Gus continued. “One of them was a fat

fellow, which sort of influenced the kind of character I wanted to do

for the comic strip I was planning. I cleaned him up a bit, made him

a bean farmer and named him ‘Gordo,’ which is a nickname

I had heard for fat guys. I was going to do a Mexican Li’l

Abner. I was just going to be funny, then I

realized that I was depicting a real group of people here. I was

caught, and I had to go with what I had created.”

He gave Gordo a shave and slowly eliminated the pidgin lingo the characters all spoke. But that was only the beginning of the strip’s transformation. In the spring of 1959, Arriola converted Gordo from bean farmer to tour guide. It was a brilliant maneuver: by this single stroke, the cartoonist had opened up a vast source of gags for the strip. Henceforth, he regaled American readers with many aspects of Mexican folklore, history, and art in an informative but always entertaining fashion. The strip doubtless introduced many of its readers to such things as pinatas, frijoles and burritos not to mention a host of Spanish terms— amigo, adios, compadre, and so on.

|

|

Arriola was born into a Mexican family and culture: his father, raised on a hacienda in the Mexican state of Sonora, had come to the U.S. in the 1890s, settling in Florence, Arizona (as Gus usually said, “the northern part of Mexico now known as Arizona”). The family moved to Los Angeles when Gus was eight. As a child, he spoke only Spanish; he learned English by reading the funnies in the newspaper. But the cartoonist had never been to Mexico, and as soon as Gordo became a tour guide (whose clients were usually toothsome turistas from north of the border), Arriola felt particularly deprived.

He had researched the country in books for years: “I read everything I could,” he said. “Travel books, history books, all kinds of books on Mexico. It was a growing interest, a genuine, consuming interest.” But now he wanted to see it for himself.

He worked enough ahead on his deadlines to take a four-week trip to Mexico in 1960.

“When I went to Mexico for the first time, I saw the country that I had been representing all these years with a new eye. All my information had come out of books, but I knew some of the places I was seeing pretty well. I was visiting places I had written about. And I recognized them. I was fascinated, naturally, by the art. And I tried to work it all into the strip—the history, the culture, the folk art—as seen through Gordo’s eyes. It was fascinating to work it into continuities or into individual gags, so I did it as much as I could without becoming too educational with the strip.”

The

comic strip medium is uniquely suited to retailing the legends of the

culture: Arriola used images that evoked Mexican folk art, adapting

the glyphs of pre-columbian codices.

Enthralled by Mexican art, he and his wife operated an import business and shop in Carmel, selling Mexican crafts, art and artifacts from 1961 to 1963.

He won awards and accolades for his efforts. The National Cartoonists Society named Gordo the best humor comic strip in 1957 and again in 1965. Also in 1957, the Artists Club of San Francisco recognized “his pioneering in bringing design and color to a new high in the field of newspaper comic strips.” In 1983, he was named Citizen of the Year in Monterey’s Parade of Nations, and in 1999, he received the Charles M. Schulz Award (the Sparky) from the San Francisco Museum of Comic Art for lifetime achievement. In 2007, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by California State University - Monterey Bay. A week before his death, Arriola was honored again for lifetime achievement, this time by the Arts Council of Monterey County.

But Gordo was more than an ethnic goodwill emissary. The comic strip was profoundly about people and humanity, as San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen recognized:

“We all need families, our own and at least one other,” he once wrote. “For more years than I care to think about, my other family has been the singular creation of Gus Arriola—Senor Gordo and his extended menagerie of diverting humans and spectacular animals. Haven't we all wanted to live as Gordo does? One can only envy him his charmed life: the perfect village, the adorable senoritas, the easily survivable hangovers and heartbreaks, and the marvelous array of animals that give the comic strip—a term that seems inadequate—its several dimensions.

“Gus's are real people,” Caen continued, “the kind one can easily and happily live with for a quarter of a century. I know, because I have done it. As for Gordo himself, he is a literary contrivance of the first magnitude—buffoon as hero, great lover manque, a pen-and-ink Everyman whose triumphs and tragedies are our own. Long may he and his flock survive. Breakfast without them would be unthinkable.”

Because the animal (and, later, insect) characters in the strip had always been one of its chief attractions, Arriola was creatively positioned to stump for ecological concerns, and he was one of the earliest figures in popular culture to do so.

Arriola matched his literary achievement and quiet crusading with graphic wizardry. A supremely inventive stylist, he changed the way he drew twice during the run of the strip. He had graduated into newspaper syndication from the animation department of MGM, to which he had migrated after a year in the Mintz shop, and he rendered the strip at first with MGM visual mannerisms. By the late 1940s, however, he had nearly achieved pictorial realism. Then in the 1950s, he suddenly—virtually overnight (literally, over a weekend)—streamlined his style, adopting a bolder line and a simplified technique better suited to transforming his pictures with decorative patterns, shapes and textures. For the next three decades, he took the comic strip medium in exciting new directions with stunning fiestas of color and design unusual for a comic strip.

|

|

The late Eldon Dedini, whose spectacular watercolor cartoons have decorated Playboy magazine for decades, was a longtime friend of Arriola’s and admired his work: "He's more of an artist than 99 percent of the cartoonists. And the Sunday color was tremendous. He would make the color designations for the engravers; I don't think all cartoonists are that involved in selecting the color for their strips. For them, skies are blue, grass is green. But Gus would make red skies. The whole thing was designed, probably with a Mexican feeling."

Reflecting on the extracomedic content of the strip, Dedini went on: "Ecology and race relations were Gus's concerns long before they appeared in other strips." He paused. "And he made cartooning look so easy," he continued. "All by himself. He did it all by himself. No assistants, no gag men (except Frances, his wife). What you saw in Gordo was all Gus. He brought a sensitivity and insight to his cartoons that existed in no other strip. Unique. People knew it and felt it. And they honored him for it."

Asked once for a one-line comment on his friend, Dedini said: “Distilling a forty-year friendship into one line isn’t easy. What I said was, ‘Look up the word elegant in the dictionary and then look up all the synonyms—that’s Gus.’ That still feels right, but of course there is so much more. It became a cliche to say that Gus has all the appearance of a Spanish grandee. But it does have to be said again: he does look like a Spanish grandee! His goatee and moustache, his manner, his dignity, his conversation—it’s all there. From Central Casting! However, this is not casting: Gus is what you see and hear. All gentleman, well-read, astute observations, sly one-liners, often puns, and a great joke-teller with an actor’s nuances.”

Arriola is survived by his wife and a granddaughter. His only child, a son, Carlin, died after an automobile accident in 1980. In a way, Carlin’s death brought on the end of Gordo five years later. Carlin, who was born in 1946, inspired a lot of the shenanigans of Gordo’s nephew Pepito, and over the ensuing years, as Carlin grew older, so did Pepito, becoming, in some sense, the comic strip version of his real-life alter ego. Moreover, Carlin, growing into and through his teenage years, often consciously helped his father concoct gags for the strip.

“A lot of the fun went out of it when we lost our son,” Gus said. “He was a very funny boy. Frances had hoped for some time that I would stop doing the strip. She thought it was going to kill me. So, after forty-four years, it stopped. I stopped. I stopped because things stop. I stopped because it was over.”

But my affection for the strip was life-long and continued unabated even after it was no longer being published anywhere. When I met Gus in person in 1998, I was delighted to see that the idol of my youth had regular feet, not clay. And soon, we were talking about my writing a book about his life and work.

Since the late 1950s, Arriola lived in Carmel, California, and I visited him there several times as the book took shape. After retiring, he spent much of his time drawing for community projects. His great friend, Eldon Dedini, and he were often asked to draw for various local charities, and they invariably did. He also assembled several books of Gordo reprints; at least two, full of stylish Sunday strips about animals, were published: Gordo’s Critters and Gordo’s Cat. And he was involved in the weekly convening of a jazz appreciation club and seminar on Cannery Row in nearby Monterey, Doc's Lab (which is amply explained in the book). Carmel is an artists colony, and several cartoonists are numbered among its denizens. Regularly, once a week—on Tuesdays ("Toons-day")—he met for coffee at a local Carmel shop with other cartoonists in the area, Dedini, Ketcham, Dennis Renault (retired editoonist of the Sacramento Bee), Bill Bates, and other writers and at least one poet.

Said Bates: “He had a great sense of humor. I was at a gathering one time where he introduced me around as ‘the Father of Our Country’ because I have so many children.”

Working together on the book, Gus and I became good friends. After the book was published (Accidental Ambassador Gordo; more here), I’d send him copies of my bi-weekly website effusions and I phoned him every couple months. And I always stopped in Carmel for a day to visit him and his wife Frances on my way back from the San Diego Comicon every summer. I was always there for Toons-day’s weekly gathering. Last summer, he showed me a week’s worth of his comic strip about cats. He hadn’t mentioned it before. Gus was better at drawing cats, cartoon cats, than anyone: he deftly captured both their feline grace and their comic antics, and the strip he developed, Pussy Willow, featuring only cats, was named for one of the two principal characters. He developed the strip late in his career, but when he showed it to his syndicate, United Feature, they weren’t interested, he said.

|

|

Much to my surprise, my book brought him a certain recognition that had somehow evaded his attention until then—or so I judge from comments he made, expressing delight and appreciation at learning that he was not entirely forgotten, getting letters from his fans of long ago who were glad to know that he was still alive and well. I think he felt the book revived people's memories. I treasure the notes he sent me occasionally and the affectionate way he inscribed a few original strips that he gave me when I asked. He was a sort of father figure for me: as a teenager, I "apprenticed" under Gus Arriola.

Growing up in Denver, I started reading Gordo in the Denver Post when I was about twelve. Until then, I hadn’t paid much attention to it, thinking, like most of Gordo’s potential readers, that there was something vaguely “foreign” about the strip. And, of course, there was: it was set entirely in Mexico. But in the fall of 1949, I noticed one day a diminutive leprechaun in the strip’s panels. The tiny figure seduced my eye, and once I started reading the strip, I was converted. By the time Gordo started courting Rusty Gates in 1952, I was a teenager and the love story inflamed my adolescent imagination. It was a wonderful story of yearning and fulfillment. Just the thing to capture a young man’s fancy.

In preparing the biography forty-seven years later, I read the Rusty Gates romance again, and, as often happens when you revisit scenes from your past, it wasn’t the same. In fact, it is a much better story than I’d remembered. It has nuances that are so finely wrought they slipped by my youthful perceptions wholly unnoticed. And the stories featuring Shamus the leprechaun are better than I remembered, too. (And I remembered them as being awfully good.) In fact, all the stories I remembered are better than I remembered them.

When I was a teenager, Gus effected the last change in his drawing style, and suddenly, aspiring to be a cartoonist myself, I was fascinated by the new graphic mannerisms—bold flowing lines and chiseled corners. By then, Gus was inking with a brush, the advantages of which he had learned from another cartoonist in Phoenix, where Gus lived for about five years before fleeing the heat for the coastal cool of Carmel. Gus had been watching Walt Kelly’s deft brush at work in Pogo, and the smooth flowing line intrigued him. He met Kearny Edgerton, who was a staff cartoonist on the Arizona Republican. Edgerton did sports cartoons and spot illustrations. He drew exclusively with a brush, and his supple line attracted Arriola’s attention and admiration.

“He used a Number Two brush,” Arriola said. “I used to watch him at work, and he got the nicest line. I had never tried a brush before, but after watching Kearny, I started experimenting, and I quickly realized that I could get a lot more character to my line with a brush. It was more flexible—the brush and the line. So I started working with a brush, and I never went back to the pen again except for cross-hatching and shading and so forth.”

At about the time Arriola began using a brush, I was a most attentive eye witness to the experiment. Like most young people who want to be cartoonists, I had spent many hours carefully copying the work of my favorite practitioners. My favorite tended to change from month-to-month, even week-to-week, so I copied Walt Kelly for awhile, producing a mole character that looked suspiciously like Pogo, then I fell in love with the way Carl Ed drew a secondary character in Harold Teen, and for several weeks all my drawings starred a personage who looked like Harold’s buddy Shadow. A few weeks later, I discovered Bill Mauldin’s World War II cartoons in a book my father had, Up Front, and I copied Willie and Joe for a month or more. I drew a character who looked exactly like R. B. Fuller’s Oaky Doaks for weeks; then I devoted even more weeks to forging a crime fighter in the image of Will Eisner’s famed Spirit. Copying the work of the masters is the way neophyte artists have acquired their skill since at least medieval times. In those bygone days, the practice was even formalized: young artists were apprenticed to the studios of the masters who actually made a living with their art. Unbeknownst to Gus Arriola, I had apprenticed myself to him in 1953.

By then, I was old enough to realize that I wouldn’t make much of a career by copying the characters of cartoonists whose work I esteemed. I also realized that it was a favorite cartoonist’s way of drawing, his style, that I admired—his distinctive way of drawing a line or shadowing clothing or modeling anatomy—not the characters that he drew. And I was experienced enough at copying by then to be able to mimic the styles of the cartoonists without necessarily reproducing their characters, feature-for-feature. In Gordo, then, I was studying Arriola’s drawing style, the way he made lines. And when he started changing the way he made lines, I noticed immediately. And I was enthralled. I watched, fascinated, as he changed his manner of drawing, the detailed treatment that distinguished his realistic phase of the late 1940s and early 1950s giving way to a simpler, bolder style with an accompanying capacity for ornamental splendors.

And

so when I met Gus ten years ago, it was like arriving at the

destination of a lifelong pilgrimage. And to become friends, too—ah,

a dream come true. I'll miss the sound of his voice on the phone

(we're both hard-of-hearing, so we shouted at each other a lot), his

wit, his appreciation of artistry in cartooning—in Dedini, in

Ketcham—and elsewhere, in the illustrations of another gifted

artist friend, Al Parker. In writing my book about Milton Caniff, I

"lived" closer to Caniff than I did to Gus: I phoned Caniff

more often with questions, and writing the book took much longer. But

I'll miss Gus more. Thanks to Gordo, I’d

known him all my life.

************

Here’s a Gordo Gallery displaying some of the ways I came to know Gus as well as Gordo.

|

|

|

|

|

|