|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 423 (December 2, 2021): For this hare-raising episode, we report on the growing suppression of reading in schools, the death of gag cartooning at The New Yorker, and a famed novelist writing comics, plus the usual departments, including reviews of first issues of comics. In order to assist you in wading through all this plethora, we’re listing Opus 423's contents below so you can pick and choose which items you want to spend time on. An asterisk* marks the longest items. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order, beginning with the news of the day—:

NOUS R US Supression of Reading in Schools Books Restored to School Libraries Two More Back in Schools Pressure to Censor Grows Disney Sues to Control Marvel Characters Marvel Cancels Luke Cage Series Comic-Con Invasion from the North Groo to Get Animated Snoopy Bound for the Moon, Again Editoonist to Lead Newsroom *Geppi’s Gems on Display Funny Stuff in Our Lingo Breathed’s Estate for Sale at $6.875 Million Happy Harv in Humor Times *Cathy, 45 Years Later

**BOTTOM LINERS Death of Magazine Cartooning at The New Yorker Emma Allen’s Role According to Michael Cavna RCH Protests

Covering the New Yorker Five Good Ones

PLAGUE NEWS Vaccines and Masks

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of Number Ones Of—: Regarding the Matter of Oswald’s Body Human Target Cross To Bear The Magic 2 Order

*Novelist Walter Mosley Writes The Thing

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy Over the Last Couple Weeks. Whooop.

Elegance in Art Frank Pe’s Little Nemo Roberto Mandrafina’s Big Hoax Graphic Novel

**NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews Of—: Pickles Tales Pen and Ink (Frank Cho)

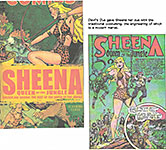

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Books In Need of Good Reviews—: Sheena Queen of the Jungle

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words

Annual Report: Year-End Tally

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

SUPRESSION OF READING IN SCHOOLS Books Restored to School Libraries. The Goddard school district of Kansas has reversed a decision that previously saw them remove more than two dozen books from circulation in the district's school libraries, including a number of graphic novels. Principals and librarians were told not to check out any of the books until the district had time to review the situation said Rich Johnston at bleedingcool.com "We're not banning these books or anything like that as a district," said a district official. "It was just brought to our attention that that list of books may have content that's unsuitable for children." As with the Texas challenge list, the Kansas list of books focuses on books by or about people of colour, feminists and feminism and LGBTQ content. The district has now sent a subsequent e-mail to parents detailing the reversal of the decision and the restoration of the titles below to the school libraries. Here is the list that the Kansas school district acted upon.

"#MurderTrending" by Gretchen McNeil "All Boys Aren't Blue" by George M. Johnson "Anger is a Gift" by Mark Oshiro "Black Girl Unlimited" by Echo Brown "Blended" by Sharon M. Draper "Crank" by Ellen Hopkins "Fences" by August Wilson "Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic" by Alison Bechdel "Gender Queer" by Maia Kobabe "Heavy" by Kiese Laymon "Lawn Boy" by Jonathan Evison "Lily and Dunkin" by Donna Gephart "Living Dead Girl" by Elizabeth Scott "Monday's Not Coming" by Tiffany D. Jackson "Out of Darkness" by Ashley Hope Perez "Satanism" by Tamara L. Roleff "The 57 Bus: A True Story of Two Teenagers and the Crime that Changed Their Lives" by Dashka Slater "The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian" by Sherman Alexie "The Bluest Eye" by Toni Morrison "The Girl Who Fell From the Sky" by Heidi W. Durrow "The Handmaid's Tale" by Margaret Atwood "The Handmaid's Tale: The Graphic Novel" adapted by Renee Nault "The Hate U Give" by Angie Thomas "The Perks of Being a Wallflower" by Stephen Chbosky "The Testaments" by Margaret Atwood "They Called Themselves the K.K.K.: The Birth of an American Terrorist Group" by Susan Campbell Bertoletti "This Book is Gay" by James Dawson "This One Summer" (graphic novel) by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki "Trans Mission: My Quest to a Beard" by Alex Bertie

And Two More Are Back in Schools. Two books listed above that were taken off the shelves of Fairfax County, Virginia, high school libraries in September are back on the shelves. “Gender Queer, A Memoir” by Maia Kobabe and “Lawn Boy” by Jonathan Everson were both the subject of complaints by parents concerned about the content of the books, reported John Domen at https://wtop.com/fairfax-county. But after a committee of school administrators, librarians, parents and students reviewed the books, they have decided the books should be reinstated. Their decisions were then upheld by Noel Klimenko, Fairfax County Public Schools’ assistant superintendent of the instructional services department. “Both books provide a narrative to students who may struggle to actually see themselves and their stories represented in other literature,” Klimenko said. “The committee found that it did not meet the definition of obscene, and that the entirety of the book did have merit.” The decisions on both books were unanimous, she said, and despite complaints otherwise, neither book condoned or promoted pedophilia. The decision to remove the books led to a two-month long review, as well as protests from Fairfax County students, who argued those stories help foster “validation, acceptance and self-affirmation of queer students.”

But Pressure Grows All Over to Censor Books in Schools. According to a New York Times report, inVirginia’s Spotsylvania County, new school board members talked of banning and burning books with “sexually explicit” material. And in Wyoming’s Campbell County, people tried to get the local prosecutor to charge library employees criminally for making sex education and LGBTQ-themed books available to young people. One of the highest-ranking members of the Georgia House of Representatives says she will push to get anti-obscenity legislation approved. The director of an anti-obscenity group testified in favor of legislation that would standardize and streamline the book-banning process. President of the Georgia Library Association says the anti-obscenity movement challenges the judgment of librarians and teachers trained to make educational decisions about content. “The concern is that it becomes a censorship issue and that it’s removing access for materials that have been selected by the professionals who work in the school,” she said.

DISNEY SUES TO RETAIN CONTROL OF MARVEL CHARACTERS Moving to defend its Marvel superhero franchises, the New York Times reported, “the Walt Disney Co has filed a flurry of lawsuits seeking to invalidate copyright termination notices served by artists and illustrators involved with marque characters like Iron Man, Spider-Man and Thor,” Black Widow, Dr. Strange and others. The move comes after heirs of five Marvel authors filed dozens of termination notices with the U.S. Copyright Office, reported Bob D'Angelo, Cox Media Group. “If the notices succeed, they would not prevent Disney from using the disputed Marvel characters. However, it would force Marvel Entertainment to share ownership of the characters and make payments to the heirs, according to Variety.” The five plaintiffs are heirs of Lawrence Lieber, 89, a comics writer and artist known for his 1960s-era contributions to key Marvel characters. Lieber’s older brother, Stan Lee, who died in 2018, was the chief writer and editor of Marvel Comics. Others doing the suing are the estates of comics illustrators Steve Ditko and Don Heck, and the heirs of writers Don Rico and Gene Colan, according to the New York Times. Rico is the creator of the Black Widow character. There have been other termination attempts; none successful. One case involved the estate of comic book legend Jack Kirby over whether he could terminate a copyright grant on Spider-Man, X-Men, The Incredible Hulk and The Mighty Thor, according to The Hollywood Reporter. In August 2013, the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a lower court’s ruling that determined Kirby’s heirs could not regain his share of rights to these characters because the former Marvel freelancer had contributed his materials as a work made for hire, the website reported. The same standard applies to the current litigation. The heirs are basing their complaint on a provision of the Copyright Revision Act of 1976, said D’Angelo, which allows authors or their heirs to regain ownership of a product after a given number of years, the Times reported.

MARVEL CANCELS LUKE CAGE SERIES By Taimur Dar at comicsbeat.com Earlier this year Marvel announced a 3-issue Luke Cage: City of Fire miniseries from writer Ho Ch Anderson and a rotating team of artists including Farid Karami, Ray-Anthony Height, and Sean Damien Hill. Originally scheduled for release in October, the first issue was delayed until December, not surprising given the current flux state of the comics industry with worldwide paper shortage and other supply chain disruptions. However earlier today through an Instagram post Anderson revealed that the entire miniseries had been canceled. Said Anderson: “Man plans, God laughs. No easy way to say this. I got the word Luke Cage got cancelled this morning [November 24], one month away from its premiere. The scripts are all written. The first issue is done and is a thing of absolute beauty. Issues 2 and 3 are deep into production. Covers have been drawn. People have gotten excited, and with good reason as far as I’m concerned. I remain as proud of this as any work I’ve ever done. Maybe someday it will be seen. But as of today this comic is dead in the water. If you want answers I am not the man to ask. My heart is broken. I’m taking a social media break to lick my wounds. Somewhere god is having a chuckle. Enjoy it.” Previous Luke Cage writer David F. Walker offered two possible reasons for the cancellation on Twitter: “Number One – pre-orders were too low to warrant the cost of printing; Number Two – someone high up on the Marvel/Disney food chain saw something in the series that didn’t sit well with them, and decided to kill it.”

COMIC-CON INVASION FROM THE NORTH Fan Expo HQ is a Canadian operation, and it is easing south of its border to acquire U.S. cons—f’instance, Megacon Orlando, Fan Expo Dallas, Denver Popular Culture Con, and a raft of other North American geek culture shows. Fan Expo has also bought six shows formerly operated by Wizard World and will relaunch them under the Fan Expo brand in 2022. The shows involved in the deal are Wizard World’s largest: Chicago, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Portland, St. Louis, and Cleveland. Fan Expo will honor “all prior commitments with fans, exhibitor, and artisans” at its rebranded shows, the companies said. Wizard World operated its Chicago convention this year, October 15-17. The deal with Wizard World will bring Fan Expo HQ’s North American geek culture show count to 17, which it says will make it the largest producer of fan conventions in the world. The company, a subsidiary of event giant Informa, has doubled down during the global Covid pandemic; it has announced a major new show at the Moscone Center in San Francisco for 2022. The Wizard World shows were built up over time, beginning with the acquisition of Chicago Comicon in 1997. The show launched in 1972 and is the second longest-running comic convention in the U.S. Sandy Eggo is the longest-running; started in 1970. The acquisition will put Fan Expo head to head with ReedPop, which operates C2E2, in the third largest market in the U.S. ReedPop appears to have ceded Philadelphia, at least for now; it has not scheduled any additional dates for its Keystone Comic Con, which it launched in 2018. Wizard Brands has been bleeding cash for years, losing $2.4 million in just the most recent quarter it reported. The company will continue to operate Wizard World Vault, which sells collectibles, and will participate at Fan Expo events.

GROO THE WANDERER ANIMATED ADAPTATION IN THE WORKS In Hollywood’s quest for comics property to adapt, the beloved Groo the Wanderer from world renowned cartoonist Sergio Aragonés is such a no-brainer, said Taimur Dar at comicsbeat.com. “It’s no surprise then that Aragonés’ has sold the Groo animation rights to entrepreneur Josh Jones and his production company, Did I Err Productions.” Dar continues—: “The landmark fantasy/comedy comic book series is the longest currently-running independent and “creator-owned” comic book property – outlasting many of the companies that published it over the last 40 years. Such publishers include Pacific Comics, Eclipse Comics (one special issue), Marvel Comics (under its Epic imprint), Image Comics and currently Dark Horse Comics.” From the official press release—: The Eisner Award-winning Groo the Wanderer, now in its landmark 40th year of publication, is the brainchild of Aragonés, who creates the stories along with wordsmith Mark Evanier. “After drawing and living with Groo for so many years, so many comics, so many pages, you can imagine I have drawn Groo in every position imaginable,” Aragonés explains. “Mark and I wondered so many times how he — Groo, not Mark — would look animated. We studied what we have seen on the screen by different animators and laughed plenty. Now, I know that we are going in the right direction and I can assure the fans that they will love Groo the way Mark and I do.” Said Jones: “I’ve loved Groo the Wanderer since I was eight years old, and to have the honor of bringing the character to on-screen life is, quite literally, a lifelong dream come true. Sergio’s style, the characters, the world, and especially the humor have always appealed to me. I just want to help bring what I’ve loved for so long to the next generation!” Aragonés is the most honored cartoonist on the planet, having won every major award in the field, including the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben Award and the Will Eisner Hall of Fame Award. His irresistible cartoons have appeared in MAD since 1963, including as the subject of “All-Sergio” special editions of the magazine. His artistic creations have been seen in DC Comics, Marvel Comics and just about every major publisher of funnybooks, and his work has been translated into more than 100 languages. Paperback collections of his work and graphic novels have sold into the millions. Evanier is renowned for his writing in several mediums. The Los Angeles native has written comic books for the characters of the Walt Disney Studios, Warner Bros Studios and Hanna-Barbera, and the three-time Emmy Award nominee’s robust resume of television writing for both live-action and animated series includes Welcome Back Kotter, That’s Incredible, Pryor’s Place, the Scooby-Doo franchise, Superman: The Animated Series, Thundarr the Barbarian, Dungeons & Dragons, Garfield and Friends, and The Garfield Show. One-time assistant to comics legend Jack Kirby, Evanier honored his one-time employer in 2008 by writing a book entitled “Kirby: King of Comics.” Evanier has earned several Eisner Awards and was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award for Animation Writing by the Writers Guild of America. For the uninitiated, Groo the Wanderer follows the exploits of a barbarian warrior who is invincible in battle, but negotiates his days with an I.Q. three points lower than a boulder. With his trusty canine sidekick Rufferto, he wanders an ancient land of mystery, magic and mayhem, looking only for a warm place to sleep, a few coins, or a taste of cheese dip. In preparation for the anticipated production(s), the franchise’s website – Groo.com – has been refreshed.

SNOOPY IS BOUND FOR THE MOON, AGAIN By Robert Z. Pearlman https://www.space.com/snoopy-nasa-artemis-zero-g-indicator The intrepid space explorer, who in 1969 became the world's first beagle to land on the lunar surface — at least in the Peanuts comic strips drawn by the late Charles M. Schulz — is set to fly for real aboard NASA's first Artemis mission in 2022. Snoopy, in plush form, will serve as the "zero-g indicator" on the Artemis 1 Orion spacecraft as it loops around the moon. Snoopy made a similar journey more than 50 years ago, flying with "Charlie Brown" as the call signs for the lunar and command modules that flew astronauts on a final dress rehearsal before the first moon landing. "I will never forget watching the Apollo 10 mission with my dad, who was so incredibly proud to have his characters participate in making space exploration history," Craig Schulz, son of cartoonist and producer of "The Peanuts Movie," said in a statement. "I know he would be ecstatic to see Snoopy and NASA join together again to push the boundaries of human experience." Aboard

Artemis 1, Snoopy will be dressed in a one-of-a-kind, miniature version of

NASA's Orion Crew Survival System (OCSS) pressure suit. The 10-by-7-inch

(25-by-18-cm) bright orange garment was made from the same materials as the

suits that will be worn by astronauts on future Artemis missions. During the planned three-week flight, Snoopy will leave Earth atop the first Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and travel farther into space than any human-rated spacecraft has flown before. As the zero-g indicator, the doll will float above the mission's seated and strapped-in "crew": an instrumented manikin named after an Apollo 13 engineer and two "phantom" human torsos that will be collecting data about the radiation and physical conditions aboard the Orion capsule. Snoopy will also be flying with four LEGO minifigures, which will be packed with other NASA-chosen mementos inside the Artemis 1 official flight kit, including a pen nib from Charles M. Schulz's Peanuts' studio wrapped in a space-themed comic strip. NASA's collaboration with Schulz and Peanuts Worldwide dates back to 1968, the year before Snoopy flew to the moon on Apollo 10. In the wake of a fire that claimed three astronauts' lives on the launchpad, NASA adopted Snoopy as a mascot and symbol for safety. Beginning with the Apollo 7 mission through this day, the agency has presented the "Silver Snoopy" award to employees and contractors whose work has ensured safe and successful human spaceflights. In 2018, NASA and Peanuts entered a new agreement to expand the use of the characters to promote the agency's deep space missions and efforts to engage students in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fields. In the three years since, Snoopy, clad in his orange spacesuit, has appeared on a new line of apparel and merchandise, in kids' books, on an Apollo TV+ series ("Snoopy in Space," now in its second season), as a McDonald's Happy Meal toy and a giant character balloon in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade (which returned this year on Nov. 25).

EDITOONIST TO LEAD NEWSROOM From D.D. Degg at dailycartoonist.com—:

As managing editor, Anderson is responsible for guiding Reform Austin’s efforts to give readers the unfiltered facts they need to hold Texas leaders accountable. Anderson’s original cartoons will be a regular feature on RA News. Until he was let go in a budget crunch, Anderson was the editoonist on the Houston Chronicle (2006-2017) where he was the last staff editoonist in the state. He won his Pulitzer in 2005 while editooning at the Louisville Courier-Journal. And hereabouts, we’ve posted samples of his current work.

GEPPI’S GEMS Stephen A. Geppi’s trove of vintage comics and collectibles is on view at the Library of Congress until mid-March. Long before costumed superheroes conquered Hollywood, reports Mark Jenkins in the Washington Post, they overran the comic book industry. So of course Superman, Captain America and Wonder Woman are represented in “Geppi Gems,” the Library of Congress exhibition of items donated by comic-book distributor Geppi. “But the show’s most intriguing entries are more novel, and often more eccentric, than well-preserved issues of Marvel and DC comics,” said Jenkins, whom we hereafter quote verbatim—: Geppi is a native of Baltimore who started his career as a postal worker who sold collectibles at weekend comics shows before opening a small chain of comic book stores. Since 1982, he’s run Diamond, the company that dominates direct distribution of comics in the United States, Canada and Britain. He’s a co-owner of the Baltimore Orioles which opened Geppi’s Entertainment Museum next to Oriole Park at Camden Yards in 2006. He closed the Museum 12 years later and donated much of its collection to the Library of Congress. According to a video interview with Geppi that’s part of the show, he gave the Library more than 3,000 items. These include things of interest to superhero buffs, of course. The show displays copies of two major movie precursors: the 1965 edition of “The Avengers” in which Captain America became the team’s new leader, and the first issue of “Black Panther,” published in 1977. The latter presaged “Icon” and “Static,” lesser-known Black champions introduced in 1993 by Milestone Comics, founded by four African American writers and artists. Those superheroes’ debut issues are here, too. There’s also a one-of-a-kind superhero illustration: A. Leslie Thomas’s prop drawing of the “Human Key Duplicator,” a device the Joker deployed against Batman — trussed-up, as usual — in two 1966 episodes of the campy TV show. Colored with gouache, the picture is much more vibrant than the washed-out comic books of the same era. Before the late-1960s boom in superheroes, there were many other comics genres: westerns, sports, horror, science fiction and funny animals are all represented in this array. (Not romance, though.) There’s even an oversize reproduction of the cover of an “all-sports” issue of Creepy, a black-and-white horror comic founded in 1964 and published intermittently until 2016. The show’s earliest items are newspaper comic strips from the 1930s, including a Popeye magazine the show describes as a “proto-comic.” Geppi is a Disney enthusiast and one of the many devotees of Carl Barks, the writer and artist known for his portrayal of Donald Duck and his clan, notably Scrooge McDuck. Featured here are several Disney mini-comics, featuring Micky, Donald, Goofy and the Seven Dwarfs. (Their creators are anonymous, as was usual for Disney.) Formally reintroduced in “The Avengers,” No.4 (1964), Captain America would take over the leadership of the Avengers in issue No.16 and has been associated with the team ever since. The oddest Geppi gem is a map of the United States produced by the alliance of Walt Disney and the Standard Oil Company of California. Designed to publicize those companies and the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco, the map is surrounded by panels from “Travel Tykes Weekly,” in which Mickey and Donald make stops on a transcontinental journey. This venerable promo piece seems cynical and innocent at the same time. It’s an amusing curiosity as well as a commentary on a nation that idealizes both the open road and an angry duck with a speech impediment.

FUNNY STUFF IN OUR LINGO And Other Moments of Mild Excitement Lately with all the fussing about abortion laws, we encounter a new terminology in news reports. Abortions, we read, are often sought by pregnant people. Pregnant people? No: sorry. Only women can be pregnant. So why the new term? Because transmen can become pregnant unless they’ve been surgically altered. Or something like that. And since we must always be both accurate and woke, “pregnant people” it is.

AND THEN WE HAVE the lately appearing LGBTQIA+ , a construction that is heaped up on LGB with other letters in an effort to become universally inclusive of every conceivable sexual orientation/practice. But seven letters will scarcely do it; see Opus 419a. So for whatever it’s worth (not much, due to Opus 419a), here’s the deciphered code: L - lesbian G - gay B - bisexual T - transgender Q - queer I - intersex; a term used to describe a person who is born with differences in their sex traits or reproductive anatomy that don’t fit typical definitions of female or male. There may be differences in regards to genitalia, chromosomes, hormones, internal sex organs, and/or secondary sex characteristics (e.g., pubic hair, breasts, facial hair, etc.). A - asexual, one who lacks sexual interest in other people + - everyone who has been left out of the preceding 7 categories

BREATHED’S ESTATE FOR SALE AT $6.875 MILLION By Mark David at https://www.dirt.com While not every writer or artist requires seclusion for focus and/or inspiration, it seems award-winning cartoonist and children’s book author Berkeley Breathed has benefitted well from the relative (if luxurious) isolation afforded him at his long-time mountaintop estate on the outskirts of Santa Barbara, California. Squirreled away at the end of narrow road that makes a dizzying wind up through the foothills, Breathed’s secluded spread is newly for sale through The Ebbin Group at Compass at $6.875 million. The cartoonist and children’s book author is best known for his seminal 1980s comic strip Bloom County, which at its peak appeared in 1,200 newspapers around the world and earned Breathed a Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1987. Bloom County ended in 1989 and was followed by the spin off strips Outland and Opus. Breathed effectively retired from cartooning in 2008 but revived Bloom County several years ago, and now regularly posts strips via Facebook.

Happy Harv in Humor Times

IT’S BEEN 45 YEARS SINCE WE FIRST MET “CATHY” By GoComics Team at gocomics.com Forty-five years ago—on November 22, 1976—we were first introduced to Cathy on the funny pages. The character was a diversion from those we typically saw in comic strips: a single woman perpetually driven to the brink by the “four basic guilt groups”: her mother, her dating life, her job, and her near-constant chocolate cravings. In the four-plus decades since, much has been written about Cathy and her reflection on women and feminism, but the connection fans feel to the characters, and to creator Cathy Guisewite, feel eternal. The original Cathy strip ran until 2010 when we saw the eponymous character announce her pregnancy to her own mother. Guisewite had officially retired. But, when the COVID pandemic hit in early 2020 she started drawing again. Cathy Commiserations was the result (recently compiled into the book called Scenes from Isolation), and it once again struck a nerve with all of us as we grappled with how to manage our lives and emotions during a global quarantine. Here, Guisewite tells about why she started drawing again, and looks back at 45 years of Cathy.

You mentioned you weren’t going to draw again after Cathy ended in 2010—but then, COVID. What about that isolation prompted you to pick up your pen again? When the pandemic hit, some found comfort in returning to their roots of baking and knitting. I found comfort in returning to my roots of dumping my angst on paper. Drawing Scenes from Isolation helped me keep my sanity and forced me to stop buying things online for at least a few hours a day while my hands were busy with colored pencils. I even found comfort in the self-imposed panic of putting myself on an almost daily deadline for awhile. Best, I found great comfort in connecting and commiserating with people without ever leaving my home or getting out of my pajamas. I never meant to pick up the story line where the comic strip ended—so the things I’ve posted on social media and GoComics are a real return to the roots of the strip: just one character sharing a moment.

I’ve read in past interviews that you didn’t really want to call the strip Cathy. What is your opinion on that now, 45 years later? Did I want readers to think the Cathy in the newspaper was a picture of myself wailing by a phone that didn’t ring and eating everything in the kitchen while waiting for Mr. Wrong to call? I did NOT! Did I want people to think it was some kind of ego trip to name a character after myself who had to call in sick for work because she couldn’t get her power suit zipped during the peak of the women’s movement? I did NOT! Do I think sharing the name helped women feel they had a real-life friend? I do. As gratifying as it was to connect so deeply with other women, did I still need to hide in the ladies' room some days when the strip came out? I DID!

Cathy Andrews’s name is partially after our (Andrews McMeel Universal) Kathy Andrews, who, in 1976, sifted through her husband Jim’s pile of submissions and voted in favor of your work. What’s your favorite memory of Kathy? My favorite memory of Kathy Andrews is her great, joyful, loving laugh. It was the laugh that encouraged me for years, and the laugh that launched my comic strip. When I sent my submission to Universal Press Syndicate in 1976, my “art” was the frantic scribbles of a frustrated 25-year-old who couldn’t draw. My “writing” was the humiliating AACK’s of a woman wrestling with love, career, and a carton of fudge ripple ice cream. Kathy’s husband, Jim—the creative head of the company—took my submission home the night it arrived to see if Kathy thought anyone could possibly relate. Kathy said YES! It was her laughing response to every page of my strange submission that was the reason Cathy became a comic strip. Her laugh is why Universal Press Syndicate stood behind the strip for those early years while I figured out what I was doing and Cathy gained a following. When Cathy needed a last name in the comic strip, I made it Andrews to honor the strip’s founding mother: Kathy Andrews and her beautiful laugh.

This has always been a personal curiosity of mine: Why is Cathy the only character with large eyes and no nose?

Recently, there’s been a spate of in-depth long-form pieces written about you and your work, along with a podcast called Aack Cast by Jamie Loftus that’s on many best-of lists. What’s your reaction to these think-pieces, and why do you think that you and Cathy are back in the cultural zeitgeist? I especially loved Jamie Loftus’s Aack Cast because of how passionately she urged listeners to consider Cathy beyond the unflattering memes and really read the words of the strip in the context of the years in which they were written. I love how she integrated Cathy into the history of the women’s movement. It helps explain my generation to the daughters and granddaughters of my generation. Many women in my age bracket have told me they’ve loved reconnecting with Cathy as a dear friend during these extremely frustrating, mashed-potato-filled months of COVID isolation. Some who used to hate the strip have told me they’ve come to appreciate it. Young women who were unfamiliar with the strip have told me how much they relate not only to the new one-frame cartoons I’ve been doing, but to classic strips posted on GoComics. The strips help them laugh at themselves and better understand their moms and grandmothers. So much has changed in the world….and lots and lots hasn’t.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, who covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these three other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com (now operated without Gardner by AndrewsMcMeel, D.D. Degg, editor); and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO Death is sort of an affront to American life. It’s so anti-aspirational.—Author Zadie Smith Familiarity breeds contempt—and children.—Mark Twain

BOTTOM LINERS Single Panel Magazine Cartooning Death of Magazine Cartooning at The New Yorker We’ve mentioned this unfolding tragedy before. And we’re about to mention it again, but before we do, we must give the Washington Post’s Comics Riffs’ Michael Cavna a voice in the matter, since he apparently thinks cartooning at The New Yorker is going along swimmingly these days. To be more than fair, we’re reprinting his entire stance on the issue before we unhorse him and his convictions. Here’s Michael on October 5—:

EMMA ALLEN IS REDEFINING WHAT A NEW YORKER CARTOON CAN BE Emma Allen sits in her Brooklyn home, her large rescue tabby cat Dante warming her feet, and waits for the cresting wave of emails to come in. By noon every Tuesday, she is up to her discerning eyes in a thousand attempts to make her grin. Allen,

the humor and cartoon editor for The New Yorker, culls through sketches,

separating laugh from chaff, and finds that the coronavirus era has brought odd

professional challenges beyond simply working from home. “Masks have not been good for gag cartoons,” Allen says wryly, noting that if a character dons a mouth covering, you can’t tell who’s speaking — be it a person or a pooch or a ficus. That can be a problem for the magazine’s typically caption-dependent cartoons. On the other hand: “It felt socially irresponsible to have people talking to each other without masks.” The tiniest line and the big picture. That is her purview since becoming only the fourth cartoon editor in the magazine’s near-century-long history — and the first woman to ascend to that lofty title — after succeeding Bob Mankoff four years ago. Allen, 33, is shaking up the popular notion of just what a New Yorker cartoon is, knowing that imitation is the sincerest form of apathy: “There was a vernacular shorthand of what a New Yorker cartoon looked like that people were copying — it was getting into a cycle of preexisting jokes,” which is “rarely the best way to go for a laugh.” As part of this shift, she wants the submission process to feel more encouraging and less insular, even recently publishing an online primer, “So You Want to Be a New Yorker Cartoonist.” She respects such longtime “heroes” of hers as George Booth and Sam Gross. Yet she is also introducing a wealth of fresh talent, including more women, cartoonists of color and LGBTQ artists — an initiative that began well before one staff archivist criticized the magazine’s decades-long diversity record last month in a viral Twitter thread. Allen knows what it’s like to laugh in the once-stock face of the status quo. As a kid raised on the Upper West Side, she would cut out New Yorker cartoons, keeping them in little green folders with all “this anal-retentiveness” of an editor — as well as the social awareness of a middle-schooler whose mother was a partner in a corporate law firm. Many of the cartoons at that time depicted “all these boardrooms and operating rooms with [only] White men,” she says, “which was clearly not the case.”

ALLEN READS AS MANY AS 1,500 CARTOON submissions weekly, culling the candidates to about 60 before she and editor David Remnick trim that by about one-third. Then as now, though, Allen could find different perspectives in the work of such cartoonists as Roz Chast (whose work hung in her family’s kitchen) and Liza Donnelly. On Saturday, Allen will moderate a virtual New Yorker Festival panel titled “Some Very Funny Ladies” featuring Donnelly, Chast, Liana Finck and Amy Hwang to “celebrate the history of women cartoonists” at the magazine. (The event’s title nods to Donnelly’s book, “Very Funny Ladies,” due out next month.) Sunday will be Allen’s twice-pandemic-postponed wedding to Alex Allenchey, an associate director at a Tribeca art gallery. “Emma is smart, she is funny and she knows and appreciates humor,” Chast says. “She’s pretty tactful, also. For instance, she has never called me up and said: ‘This batch is dreck! Why don’t you get a job in the box factory?!?’ ” Tongue removed from cheek, Chast adds: “This is going to sound corny, but I get the feeling she really cares about cartoons and about cartoonists, for which I am wholeheartedly grateful.” Allen acknowledges that her “greatest passion in all of this, and concern, is to make sure we keep the art form alive” — which requires balancing what has worked with where the magazine needs to innovate. After co-editing a humor-infused arts-and-living section at the Yale Daily News, Allen joined The New Yorker in 2012 as an assistant to articles editor Susan Morrison, who shepherds the magazine’s Talk of the Town and Shouts & Murmurs staples. Allen gradually became an associate editor on those features, grew the magazine’s humor portal online and continued to come up with new comedic ideas for multimedia. Her bosses took notice, and she became cartoon editor at 29. Whatever skepticism she faced, she learned to deflect with confident humor. “When I started in the role, I was young and I was a woman and I was not a cartoonist,” Allen says before waiting an expert beat. “James Geraghty, who was art editor from 1939 to 1973, was previously a lead miner and a truck driver, so I had probably a little more relevant experience.” “Emma’s been a godsend to The New Yorker,” David Remnick, The New Yorker’s editor, says by email, adding: “She has done a lot, in a relatively short time, to bring new voices — diverse voices, brilliant voices — to the forefront while nurturing cartoonists who have been around for a while. That demands a sense of wonder and tact and adventure — and she’s all that.” Such tactful nurturing is crucial during this kind of leadership transition. “Cartoonists are frail creatures; their humor DNA can be fickle,” says cartoonist Michael Maslin, who through his blog Ink Spill serves as a historian of New Yorker cartooning. “Emma came into a nervous room and calmed things down with her openness and good humor.” And Donnelly lauds how Allen “embodies a wonderful combination of silly and serious.” Her sensitivity toward contributors even comes down to punctuation. In New Yorker parlance, when the cartoon editor sends you an “ok” in the email subject line, that means you can chalk up your submission as a sale. The first time Allen replied to artists with an “o.k.” — using periods is house style, she says with a laugh — she heard back from eight inquisitive cartoonists about the change.

ON THE FLIP SIDE, recruiting new contributors requires honing her own style that looks outward, across many types of comedy and graphic arts. “Often the first stage in working with these contributors is [assuring them]: Don’t try to make it what you think the New Yorker will find funny. What is the New Yorker? It’s me. Make it be what you find funny,” says Allen, whose team includes associate cartoon editor Colin Stokes. “I came in from my role editing written Daily Shouts and trying to build out that platform [to] reflect the incredibly vast world of comedy I was seeing at clubs and on TikTok,” she adds. Allen has brought a new sensibility to cartoon selection, embodied in this nod to TikTok by Sarah Akinterinwa. (Sarah Akinterinwa/The New Yorker): Nearly 100 cartoonists have made their New Yorker debut during Allen’s tenure — about half of whom have been women, Maslin says, noting that as a significant increase. Allen has bought debut work from such top cartoonists of color as Ngozi Ukazu (“Check, Please!”), Keith Knight (“Woke”), Lonnie Millsap (“Bacon”) and Liz Montague (“Cyber Black Girl”). “The ‘comic industry,’ generally speaking, is very White, very male and caters to a certain age and income level,” Montague says of the traditional American market. “Prior to Emma becoming editor, New Yorker cartoons especially fell into that category. Emma has really made an effort to seek out different voices and perspectives and, in my case, take seriously a total random who happened to send her an email.” Montague cites Allen’s willingness to be bold: “I submitted a draft of someone getting their hand bitten off by a Black person’s hair with the caption, ‘I told you not to touch it,’ and was genuinely positive there was no way they would publish something like that — and they did! It was the shock of my life getting the email from Emma that they wanted that cartoon! That was the moment I realized: ‘Oh wow, she’s actually serious about this diversity thing.’ ” Allen published the magazine’s debut of Hartley Lin, the Chinese Canadian creator of “Pope Hats,” who sent in his first batch on a whim in 2018 and within weeks sold his first cartoon. She also brought in political cartoonist and graphic novelist Pia Guerra (“Y: The Last Man”), who identifies as ethnically mixed. Guerra likes how Allen “always picks our weirder submissions,” adding: “There are times we’re sure they’ll go with the more obvious gag, but then it’s the one we never thought they’d use.” Allen has hired such LGBTQ voices as Bishakh Som and Mads Horwath. “When I discuss the struggles of [an] oft-muted voice in cartooning on the national scale, I always follow up that it feels like I have had Emma in my corner this entire time,” says Horwath, a Chicago-based queer cartoonist and humorist. Som notes that Allen facilitated the artist’s inclusion in a “Funny Ladies” Society of Illustrators exhibit that was “a win for transgender cartoonists everywhere.” Mankoff, Allen’s predecessor, acknowledges in an email that during his editorship, 90 percent of the cartoons came from “40 or so” contract cartoonists, who "were a diverse group when it came to height and weight, but that’s about it.” He says Remnick encouraged him to pursue more diversity and that he believes he made progress. “Emma has done a great job continuing this mission,” he says, and she has “breathed new life into a beloved tradition.” Considering that Allen reads as many as 1,500 cartoon submissions weekly — cutting the candidates to about 60 before she and Remnick trim that by about one-third — she especially relishes what surprises her. “There’s nothing better than a cartoon that I immediately scan the situation and think: ‘I know where this is going,’ and being caught off-guard. “That is an instant ‘o.k.’ ”

Well-This-Is-More-Than-I- Can-Take-Sitting-Down Department Back with Yr Fthful Correspnt—: Yes, Emma Allen has changed cartooning at The New Yorker. But not, alas, for the better. Her preference, judging from the cartoons in the magazine, is for surreal humor—that is, humor that arises from coupling two otherwise unrelated elements. Or, to put it another way—silly humor. Surreal humor is not an advance in the history or manner of cartooning. Surreal humor destroys the essential nature of the gag cartoon which is that the caption “solves” (or “explains”) the picture, or vice versa. We laugh when we realize, suddenly, how the verbal-visual balance is achieved. In a silly cartoon the verbal component explains nothing because it’s silly. Her other preference is for talking animals. That’s a subset of surreal: talking and animals are unrelated but, here, coupled for a joke. Every issue features at least two talking animal cartoons; sometimes as many as four. Both of Allen’s preferences remove humor from the real world. Indulging her preferences has the effect of destroying gag cartooning in The New Yorker tradition in which the jokes were often comments on contemporary life. Satire sometimes but not necessarily. And since The New Yorker is the last bastion for gag cartooning in this culture, Allen’s destruction of it there is significant. If we take a look at the cartoons in a recent issue of the magazine, we can quickly see the effect of Allen’s choices. There were 14 cartoons in the October 11 issue, fewer, slightly, than usual; usually, the cartoons run to 15-16. But since this was the most recent issue at hand, I seized upon it. First, we have 4 talking animals cartoons. The dog and the stick cartoon made me laugh, but my laughter is inconsequential here, so we’ll just leave that laying there, squirming desperately. There were 4 surreal cartoons, all of which show up on our second visual aid posted nearby.

Moving onward, we judge 3 of this issue’s cartoons as “okay”: they attempt the magazine’s usual target: they all reference some aspect of contemporary society. Not strong satire but at least our world, not Allen’s. In the first at the upper left, the ritual of a trip to Europe is gently ridiculed. Next around the clock, limoges tea sets are the source of a giggle, enhanced by the allusion to the bull-in-a-china-shop axiom. And finally, smoothies get a passing jab.

Then

in the next display, we have two purely nonsensical cartoons. They appealed to

Allen’s sensitivities for the surreal, no doubt. Finally, here’s Roz Chast.

Chast is in nearly every issue of The New Yorker. Dunno why. She is

without categorical explanation. The proportions here are about the same in most issues of The New Yorker. Looking at some August issues that happened to be lying around, we see the following: August 2: 8 surreal, 1 talking animals, 2 nonsense, 3 okay August 9: 9 surreal, 2 talking animals, 2 nonsense, 1 okay; 1 Chast August 16: 9 surreal, 2 talking animals; 2 nonsense, 2 okay The number of “okay” cartoons—those that reference some aspect of contemporary life—is small; compared to the surreal, “minuscule.” And so the relevance of New Yorker cartoon humor to our lives as we live them is tenuous. Cartooning in The New Yorker is fast losing ground, and at this rate, it will doubtless disappear altogether err long.

COVERING THE NEW YORKER The covers of The New Yorker are another matter altogether. They are a screaming success. They are often virtually editorial cartoons commenting upon the passing scene, but lately the emphasis has shifted to purely design considerations. And the considerations are sensational and impressive. Nearby, we’ve posted a short collection of five that smited mine eye in the last couple months.

PLAGUE NEWS Twenty years on from the horrors of 9/11, we are now under attack by a different kind of enemy—Covid-19. With more than 1,500 Americans dying from the virus in a typical 24 hours, we are suffering a 9/11-size death toll every two days. ... Compared with what was asked of so many people two decades ago, the sacrifices required in this struggle are minimal. We don’t have to dig through smoking ruin with our bare hands or exchange fire with jihadists in the Tora Bora mountains; we simply need to roll up our sleeves and get vaccinated. Yet about one quarter of the vaccine-eligible population has so far failed to do this, with many insisting that it’s their right to risk catching and spreading this killer disease. September eleven was an attack by foreign extremists; the bodies now piling up in morgues are the victims of a domestic madness.—Theunis Bates, Managing Editor, The Week

ALL 50 STATES and the District of Columbia require the DTap vaccine (or another vaccine combination for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis) for kindergarten entry. All 50 states and DC require the IPV vaccine against polio for kindergarten entry. All 50 states and DC require the varicella vaccine against chickenpox for kindergarten entry, though some will accept proof of immunity instead of vaccination. And 49 states and DC require the MMR vaccine against Measles, Mumps, and Rubella for kindergarten entry. Iowa, the only state to not require the MMR vaccine, requires a measles and a rubella vaccine, but not a mumps vaccine. We dutifully accept all these vaccine obligations. Why not the Covid-19 vaccine?

IN COLORADO, MY HOME STATE, THE STATISTICS are piling up in favor of mask-wearing and shot-getting. Students in Colorado school districts without mask mandates are infected with Covid-19 at higher rates than in districts that have face-covering requirements. And cases of infection among school-age children are significantly higher in counties that have low vaccination rates. Statistics around the country for adults show about the same. Thus, if you wear a mask, you’re less likely to get infected; even more so if you get vaccinated. Conversely, if you aren’t vaccinated and don’t wear a mask, you’re more likely to get infected.

IRKS & CROTCHETS Man is the only animal that can remain on friendly terms with the victims he intends to eat until he eats them.—Samuel Butler I tell vegetarians, “Hey, vegetables are living things, too. They’re just easier to catch.”—Kevin Brennan I did not become a vegetarian for my health. I did it for the health of the chickens.—Isaac Bashevis Singer

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

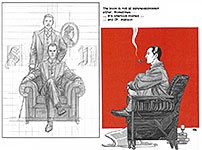

THE FIRST ISSUE of Regarding the Matter of Oswald’s Body is all about mystery and none about answers. Almost. It begins with a grisly full-page picture of a corpse in a coffin, about whose identity there seems to be a question. So in the following sequence, dated October 1981, the body is dug up, but we still know nothing about it/him. Next, we’re in early November 1963 during a bank robbery in progress. The bank has only $18, so that’s all the robber, Shep, gets. Shep checks into a motel, learns from the clerk that there’s been no word about his robbery in the news. But as he’s driving from the bank to his motel, the radio is on, and we hear that President Kennedy is going to fly from Fort Worth to Dallas. As Shep tries to fall asleep, Frank enters his room, and, introducing himself by way of persuading Shep to put his gun down, reveals also that he knows everything about Shep, who is a failure as a crook except that he never gets caught. On that basis, Frank offers Shep a job. No explanation. Next we meet Buck Willy, playing his guitar behind a fence in a saloon. The bartender offers him a free beer if he stops trying to play and just leaves. Buck does just that, and as he crosses the parking lot, Frank shows up and offers him a job, perhaps boosting a car. Buck doesn’t answer in our presence. Then we’re in a shooting gallery where a red-haired guy named Wainwright is practicing and proving himself a good shot. It’s now November 10, 1963, a day after Buck gets Frank’s offer. At home—a fancy, expensive looking place—Wainwright is confronted by his father who wishes the son were a college student and not a sharp-shooter. Wainwright goes to drown his sorrows in a nearby bar, and Frank arrives, offering him a job—“a senior position within the agency at the Mexico City station.” Wainwright is stunned. But silent. Now (“later that night”), we in a jail cell with Rose—“the Yellow Rose of Texas”—who is released because charges against her have been mysteriously dropped. Frank’s doing, no doubt; he’s there. He alludes to a job he has for her, and takes her to meet the rest of the gang—Shep, Buck Willy, Wainwright, plus Jack and Lou, who wears a police uniform. The “job” will use Shep to get in and get out, Buck behind the wheel, and Wainwright with the firepower. Rose will create forged documents that they’ll use to “get away clean.” We turn to the last page in the book, and there’s a picture of alleged Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald holding a rifle. Says Frank: “All you gotta do is find a guy who looks like this guy in the picture. ... That’s sit. That’s the whole deal.” The last page thus connects to the first page. Is the guy in the coffin Oswald? Or some look-alike? And that’s where writer Christopher Cantwell leaves us hanging. Well, not quite. A page of discursive text opens the book and closes it (after the picture of Oswald). The texts discuss doppelgangers or “doubles”—look-alikes. There’s also a sort of organization chart that links Shep, Buck, Rose, and Wainwright just before it drops to “decoy.” In the next issue perhaps, we will encounter the person and function of the “decoy”? The whole book is a demonstration of the function of episodic storytelling. Here, each episode introduces a character, his talents and his personality. Shep is a bank robber, but he isn’t successful at it, and he’s otherwise a wholly pleasant personality despite his using a gun in his line of work. And despite his accomplishment at the shooting gallery, Wainwright is a fairly timid guy. And so on with Buck and Rose. Except

for the scenes introducing Shep the bank-robber, all of Luca Casalanguida’s pictorial storytelling is masterfully rendered in a Caniffian manner, artfully

etched with defining shadows and other swatches of solid black. A As you can see from the two pages we’ve posted nearby, Casalanguida tells the story visually: the pictures carry at least half the narrative’s full weight. I’d sign up for the next issue based solely upon the visual mastery revealed here. But Cantwell’s storytelling is equally expert, and the cliff-hanger—who and what are they up to?—is enough by itself to bring me back. Was it Lee Harvey Oswald who was killed that day in a Dallas police station? Or some look-alike?

DC’s BLACK

LABELED HUMAN TARGET begins with an exquisitely rendered picture of a

cocktail glass. After someone drinks from it, we see that the drinker is a

dignified-looking guy in a business suit who is apparently sick. He coughs,

painfully. Then he lies down on the bed in his room and dies. He leaves a note

that says: “I love you,” explaining as he writes the note, “I was never any

good with words; she probably knows that by now.” Next, twelve panels trace the “story” from Day Twelve to Day One. Then we watch Lex Luthor step on stage to address a large audience. In the midst of his talk, someone shoots him. And a “mad bomber” comes on stage and threatens to blow up everything. Instead, he’s shot by Luthor, who gets up from being dead to do the shooting. After that, we are in Luthor’s office as he and the man we saw coughing at the beginning (his name is Christopher Chance) discuss the man’s assignment, which is to take Luthor’s place somewhere so that he can be killed, not Luthor. Chance is “the human target.” Chance pours himself a drink, then complains (to himself) that the drink tastes bad like some bad coffee and it is seeping as some kind of tin through his body—throat, chest, stomache. On the next page, he awakens, seemingly at the wheel of a speeding car; or is he at the wheel of a car that just crashed into a tree? Then Chance, after surviving the crash, is getting dressed after being examined by Dr. Midnight, who explains that the poison he’s ingested will take twelve days to kill him. The poison was in the coffee he drank just before going on stage as Luthor. Its lethal effects, however, were disrupted when Chance was hit by the assassin’s bullet while he was on stage: he had vomited, ridding himself of most of the poison but leaving enough to do its job—eventually. After twelve days. Going back to the assassination sequence, we can see all the evidence supporting the situation I’ve just described. But the disclosure has come piece-by-piece, none of it connected until just now, in the Dr. Midnight sequence. Later, when Chance is in his hotel room, lying down awaiting death, he gets a phone call from Dr. Midnight, who tells him that the poison probably came from a member of the Justice League. So are they trying to kill Luthor and mistakenly hit Chance? But Luthor hired him as a decoy for would-be assassins, so his getting shot isn’t a mistake: it’s what Luthor thought would happen. On the last page, we’re back where we started, with Chance lying on the bed in a hotel room, waiting to die. And now we know that the cause of death is poison. As in the Oswald book we just looked at, the story here is advanced through episodes, and each of them reveals something more about Christopher Chance, the human target. He has a wry sense of humor, and he accepts his role without question or demurer. The episodic structure enables writer Tom King to prolong the suspense—what is this story about anyway?—and he deftly capitalizes upon the opportunities his method offers. Greg Smallwood’s pictures are, as I’ve said, simply exquisite. He manner is thoroughly realistic but his realism is achieved with relatively simple linework, enhanced with crayon shading in places and with regularly deployment of close-ups, which always withhold more visual information than they impart. Color, sometimes administered in simple geometric swatches, likewise gives the visuals the illusion of more complexity than they actually have.

. The suspense that begins and ends the book is whether the human target is going to die. But since he signed on expressly to do just that, why the suspense? And that’s the question I’d look for an answer to in the next issues. But what, exactly, does the back cover illustration of a pin-up calendar have to do with the story? Well, the calendar with twelve number days. Of course. And this issue is the first day, crossed out because it’s done with. But I think Smallwood just surrendered to his desire to draw a good-looking babe in a brief swimsuit.

CROSS TO BEAR No.1 begins with a narrator in 1889's Boston musing about a “truth” no one wants to acknowledge anymore. He convinces “them” that he could do “it” (whatever “it” is) even though he knows the “truth.” Then we watch a band of assassins kill their prey. Perhaps the narrator was also involved: he has bloody hands in ensuing pages. Then, suddenly, we’re in Tombstone, Arizona, when a stagecoach arrives with a lady passenger disembarking. Simon—an Englishman in a derby, perhaps the narrator in the previous segment?—is looking around the town for another “limey,” and he goes into a saloon where the owner, a bearded old limey, is being beaten up for being a limey. Simon interferes and stops the beating, then the old guy, Edgar, orders the men who attacked him to leave the saloon. Edgar and Simon know each other; Simon’s in town searching for Edgar. In a discussion with Molly, Edgar’s wife, we learn that Simon and Edgar are members of “the Order.” Edgar left the Order because he didn’t like the killing part of it. As it develops, the “Order” seems to be an organization of medieval times with knights in armor. In the midst of their discussion, Simon suddenly realizes that he’s lost his “piers.” No other explanation. Edgar won’t do what Simon wants him to do, and the two part in anger. Then comes three pages of handwriting that seems to be about the “Order” and the need for piers and arches to maintain the architecture. There’s more mysteriousness in Marko Stojanovic’s story than we can be expected to sort out at the first sitting. Why must the story begin in Boston and then surface in Tombstone? Artist Sinisa Banovic adds to the confusion. He’s an excellent artist, but his portrayal of the narrator of the opening sequence is blurred by shadowy black solids, so we can’t be certain that Simon, in Tombstone, is the narrator. We assume it. Banovic

also varies perspective, sometimes wildly, in order to compensate for the excessively

wordy panels, but the Although there are episodes enough to help define personalities, since the identities of the characters are not clear, we learn nothing much of value from the episodes. Only old Edgar is clearly enough delineated (it’s the beard) to be recognizable page after page. But even if we assume that it’s Simon with whom he is talking in the closing pages, I don’t feel engaged by what they’re contemplating. When Simon stalks off, I don’t care. And when a reader doesn’t care, the story has failed.

THERE ARE TWO sensible—that is, “making sense”—sequences in the first issue of The Magic 2 Order. One at the beginning of the book; the other, about half-way through. And that’s not enough to create the milieu that writer Mark Miller seems to be aiming at. In the opening sequence, Victor Korne wants to leave his work at the end of the day but is detained until 5 o’clock, quitting time. He leaves and vows never to be delayed in this fashion again. He visits Aunt Brigitta, who demonstrates her supernatural power by causing two policemen nearby to shoot and kill a couple of civilians; then, “to tie up loose ends,” they turn on each other and kill themselves. Then comes an incident of burglary or house-call killing which Regan Moonstone is investigating. The mother and father have been killed; he rescues the child, a boy named Toby. We see the man without a face. (Just an open hole in the front of his head.) Regan gapples with an intruder, and Toby kills the intruder with a pair of scissors. Then in the book’s second sensible sequence, we see Cordelia Moonstone (Regan’s sister? Mother?) naked in bed with a teenager. He leaves to find the bathroom (a quite natural finish to a canoodling incident), and we see a marvelously fanciful scene of creatures of all sorts administering to an old, fat bearded guy— Santa Claus? Doesn’t matter; great picture. Meanwhile, Cordelia “crosses” into her sister’s birthday party, another collection of wonderful characters and creatures. Then we’re in France for the book’s fourth narrative segment, and there, Zhang arranges an airplane crash in which he is supposedly killed. (He’s not, of course.) And everyone wants the good old days to return. No, we don’t know who Zhang is. And Victor Korne doesn’t return. Neither does Regan Moonstone. None of these segments seem connected, but they must be or writer Miller would not have introduced them. And

that brings us to the book’s conspicuous flaw: namely, the lack of apparent

connection between its four segments. Without a connection, we don’t know which

of the characters in those segments are the one(s) we should be identifying Stuart Immonen’s pictures are a delight to watch. Lines that boldly wax and wane, details clearly rendered, no obscuring shadows of solid black. His Cordelia by herself is a good enough reason to buy the book. The story, alas, is not. But it edges up to the task enough to be tempting. The storytelling lets pictures carry their fair share of the narrative. Pictures and words together—no caption narrative. Nice.

WALTER MOSLEY WRITES THE THING All of a sudden, respected authors with established careers writing actual books (with hard covers and more than 50 pages) are writing comicbooks! Astonishing. The first to do this (as far as I know; and I haven’t researched it at all, so I’m just reporting a recent “discovery”) was Ta-Nehisi Coates, a Black writer who’d established himself as a writer about Race and all its accouterments. His first comicbook efforts were on the Black Panther series, which is about a superior Black culture in the middle of Africa. And then he took up Captain America. I found that development astonishing. Coates has written in various ways that he doesn’t think the American culture/society will ever solve its racist tendencies. Black people will never be at home in America. So if he believes that, how—to what purpose, really—does he deal with the champion of American values, Captain America? For Coates, I assume, Captain America will never succeed. Coates resolves this contradiction, if I recall aright, by establishing that Captain America is a symbol of “hope.” A hope, presumably, that will be forever frustrated. But a hope, nevertheless. An interesting proposition. Then in a recent issue of Previews that lists all the forthcoming comicbooks, I noticed that the current limited series (6 issues) of The Thing is being written by acclaimed mystery writer, Walter Mosley. Mosley has written over 40 prose books, many fiction; some, not. My first Mosley book was his first novel about Easy Rawlins, a hard-boiled Black private detective, who lives in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. In his first book, Easy finds himself forced into being a private investigator; the book, Devil in a Blue Dress, came out in 1990 and was made into a movie with Denzel Washington in 1995. I recently watched the movie, and I thought Washington (who is so young that he’s barely recognizable) did justice to Easy Rawlins. So how come we haven’t had any more Easy Rawlins movies? Probably because Washington very quickly became an admired movie actor and box office success, and both we and he aspired to greater things than mystery stories. Mosley has written 15 more about Rawlins, whose name is enough to get me to read the books. But Mosley has written other books about various characters. (Which I’ll go into a little here because I’m going to write about this in a forthcoming Rants & Raves.) One of the first featured Fearless Jones but Fearless plays a secondary role. The real hero is bookshop owner Paris Minton, who meets a beautiful new woman and before he knows it, he has been beaten up, slept with, shot at, robbed, and his bookstore burned to the ground. He's in so much trouble he has no choice but to get his friend, Fearless Jones, out of jail to help him. There are three books in this series. Mosley has written six books about Leonid McGill, a New York detective, and three books about Socrates Fortlow, a sixty-year-old ex-convict still strong enough to kill men with his bare hands who lives in L.A. Filled with profound guilt about his own crimes and disheartened by the chaos of the streets, Socrates calls together local people of all races and social stations and begins to conduct a Thinkers' Club, where all can discuss life's unanswerable questions. Years ago—early 1990s— Mosley enabled a convention program chair I was working for get out of a dilemma. The program chair was Jewish, and wanted to invite a Jew to be the keynote speaker at the convention. But he was under considerable pressure to invite an African American to fill that slot. Then I found out about Mosley. I phoned the program chair and told him what I’d found out: Mosley, who’s Black, identifies as both African American and Jewish, with strong feelings for both groups. The program chair promptly invited Mosley. (And Mosley spoke at the annual banquet.) Mosley explains his desire to write about "Black male heroes" saying "hardly anybody in America has written about Black male heroes... There are Black male protagonists and Black male supporting characters, but nobody else writes about Black male heroes." The Thing is not, so far as I can tell, black; he is orange, but that may be enough to attract Mosley’s attention on racial matters. We’ll see how far he gets.

QUOTES & MOTS In real life, I assure you, there is no such thing as algebra.—Fran Lebowitz Good taste is the worst vice ever invented.—Poet Edith Sitwell Our frustration is greater when we have much and want more than when we have nothing and want some.—Philosopher Eric Hoffer

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy YOU’D THINK WE’VE HAD ENOUGH EDITOONERY, what with featuring editoons in our last posting, Opus 422a. But life and the fakery of modern politics goes on, ever onward, and so we’ll pause here to see how a few selected editoonists use visual metaphors and other imagery to transmit their messages powerfully. The

image in Chris Britt’s image is that of a sort of clubhouse for gun

wielding extremists where “vigilante justice rules.” The occupants are

overjoyed to learn that Kyle Rittenhouse has been found not guilty. Next around the clock, Kevin “Kal” Kalaugher shows one likely situation that the Rittenhouse verdict might inspire: his imagery depicts bands of teenage boys (Rittenhouse was 17 at the time of his gunplay) who feel free to roam the streets “protecting” citizens, a prospect that ought to terrify ordinary people. Clay Bennett’s editoon is startling in its uncompromising imagery. Rittenhouse’s acquittal is a victory for the bloody hand of vigilantism, self-appointed law enforcers. I, too, was upset by the verdict, which seemed to license violent vigilantism. But then, when last week’s issue of The Week arrived, I learned somewhat more about the Rittenhouse circumstance—: Rittenhouse, an Illinois resident, went to Kenosha, Wisconsin along with dozens of other armed civilians and militia members in response to rioting that followed the shooting of a Black man by a white police officer. Carrying an AR-15 style rifle he was too young to legally purchase, Rittenhouse stood guard outside a car dealership, and then, after being chased by several protesters and scuffling with them, fired multiple shots, hitting three people, two of whom died. During the two-week trial, Rittenhouse sobbed on the stand when testifying and said he’d fired only after his victims chased him, hit him with a skateboard, grabbed for his gun, and aimed a pistol at him—assertions backed p by some witnesses and video evidence. The passages in red tell of things about the case that I was not aware of. It seems to me that a dedicated and judicious news media would have made some of this redline stuff widely known by including it in the various reports on the Rittenhouse affair. I haven’t read or watched every report on Rittenhouse, but I’m reasonably dutiful about keeping up on the news, and I have not, until this week’s The Week, read or heard of any of the redline stuff. If the press were doing its Constitutionally anointed job, I would have known all of the redline information. Knowing it, now, Rettenhouse’s acquittal seems entirely appropriate; without knowing it, it doesn’t. Still, I can’t overlook Kal’s point. And neither can those who heard a message in the acquittal: “You have a right to defend yourself. Be armed, be dangerous, be moral.”

THE SAME EXPLOSIVE MIX of racial and political division, gun culture, and self-defense laws was on display in the Georgia trial of the killers of Ahmaud Arbery. In a society filled with armed vigilantes, there will be more shootouts “at the OK Corral,” and it will become “increasingly impossible for the police to sort aggressors from self-defenders. Rittenhouse may be tried again, this time in a wrongful-death lawsuit by the victims’ families. And a civil jury might see evidence the judge excluded from the criminal trial, such as a video showing Rittenhouse celebrating the shootings at a bar with the far-right militia group the Proud Boys while wearing a T-shirt that read “Free as f–k.” A friend of mine and a sometime peruser of these paragraphs sent me the following: “I read an article by a prosecutor about the Rittenhouse judge. If you recall, the judge threw out the charges for Rittenhouse being illegally in possession of a gun. That offense was a minor misdemeanor so most people just blew by it. But as this criminal lawyer explained it, it was key to getting Rittenhouse off and certainly was done on purpose by the judge to help him. “If he had been found guilty of the weapons charge, which was undeniably guilty of, he would be seen by the law as a proven criminal as he went to Wisconsin. Therefore he couldn't plead self defense because he was in the act of committing a crime himself, while his victims were not. There was no evidence the three people he shot were indeed committing crimes. So the judge opened that door for him. A good basis for appeal if the DA has the stomach for it.” I looked at other articles that considered the reasons for the judge’s ruling. It’s confusing for a legal novice like me, but, to re-cast the argument in simple if somewhat inaccurate terms, he was trying to maneuver around a snare that a pair of conflicting laws on self-defense seemed to set. It’s more than I want to go into here; the gist is that in by-passing those laws—or in wriggling around them, whichever— he did what my friend described above: he made possible Rittenhouse’s self-defense argument. And he undoubtedly knew what he was doing. So was justice subverted? Okay. Onward. The last editoon on our first visual aid is by David Fitzsimmons, whose imagery of father and children playfully indicates the difference between childhood and adult-hood. In a word, Santa Claus.

IN

OUR NEXT EDITOON, we take up other matters—first among them, Joe Biden’s

apparent standing in public opinion polls about how he’s doing his job.

Generally speaking, he’s failing. And Dick Wright’s visual metaphor of

Biden as the clean-up gang behind a defecating woke wacko horse alludes to that

circumstance. All that horseshit to shovel away. But it is, after all, just

horseshit. Next, Tom Stiglich deploys a once-well-known symbol, the Morton Salt Girl, to indicate how well or badly Vice Prez Kamal Harris is doing. We haven’t seen or heard much of her, but I’m not sure Stiglich’s emblematic toon explains the reason. Morton Salt adopted the girl in about 1914 for the label on the package of its new “free flowing salt.” The package was round and blue with a patented pouring spout. Try-out advertising displays were solicited, a dozen or so. One of them attracted the attention of management. It showed a little girl holding an umbrella in one hand to ward off falling rain and, in the other hand, a package of salt tilted back under her arm with the spout open and salt running out. Sterling Morton, secretary of the newly-formed company, later explained his enthusiasm for the ad: “Here was the whole story in a picture – the message that the salt would run in damp weather was made beautifully evident.” All that was left to do was to create the verbal part of the message. The initially planned copy (“Even in rainy weather, it flows freely”) was appropriate but too long. “We needed something short and snappy,” said Morton. Other suggestions included “Flows Freely,” “Runs Freely,” “Pours” and then, finally, the old proverb, “It never rains but it pours.” The latter was rejected as being too negative and a more positive rephrasing resulted in the now famous slogan, “When It Rains It Pours.” The Morton Salt Umbrella Girl and slogan first appeared on the blue package of table salt in 1914. Throughout the years the girl has changed dresses and hairstyles to stay fashionable. She was updated in 1921, 1933, 1941, 1956, and 1968. In 2014, the Morton Salt Girl was refreshed one more time in celebration of her 100th year as the face of the brand. The Morton Salt Girl was successful in displaying the new salt’s most attractive aspect: it flowed freely even when the weather was dampish. How does that apply to Harris? She hasn’t been put in a position to succeed? If she’s an echo of the Morton Salt Girl, she’s succeeding as she walks by us. Harris may have legitimate complaint about her assignments not helping her to succeed as Vice Prez. But the Morton Salt Girl picture doesn’t make that point. Rick McKee’s picture of a polarized America deftly ties image to message. And if Uncle Sam is the turkey wishbone and the Left and the Right tug at his legs, he’ll never split right down the middle. And what will become of America then? That’s the question McKee’s imagery asks. Next is Gary Varvel who turns to Peanuts to make a point, using Charlie Brown’s scrawny Christmas tree to show how inflationary Biden’s economic efforts have been. The image works because Charlie Brown’s Christmas is so well-known. Varvel letters “apologies to Charles Schulz” in the corner of the cartoon, the traditional appeal for forgiveness as a credit for the initial creation. But I suspect Schulz himself wouldn’t be pleased. To the best of my knowledge, Schulz never objected publically to editoonists using his characters and creation to convey political messages. But he didn’t like it. Mostly, he felt readers would think he endorsed the opinion the editoonist was expressing. And Schulz wasn’t sure that he’d always agree. In fact, I suspect he thought he’d mostly disagree.

READ & RELISH Here at the Intergalactic Rancid Raves Wurlitzer. My grandmother began walking five miles a day when she was eighty-two. Now we don’t know where the hell she is.—Ellen Degeneres My grandfather is a little forgetful, and he likes to give me advice. One day, he took me aside ... and left me there.—Ron Richards

ELEGANCE IN ART The thing that engages me about comics is the artwork. The pictures. The drawing. I tend not to hover long over art that isn’t drawn. The lines of drawn art intrigue me. And just as we were getting ready to button up this Opus, two elegantly drawn works found their way onto my desk. The first is Frank Pe’s Little Nemo after Winsor McCay. Hereabouts are a few pages. Elegance. We’ll review the book next time. We haven’t time at the moment to do more than lay some of Pe’s beauties in front of you.

The other book is a graphic novel by Carlos Trillo as drawn by Roberto Mandrafina, The Big Hoax. Mandrafina’s juicy line knocks me over. It’s a treat to watch. But, again, we haven’t time to review the book at the moment, so we’ll just leave you with a few of his pages to marvel at, promising to return with an actual review next time.

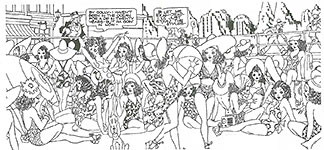

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping LET’S

START with comic strips the comedy of which couldn’t exist in any other mode.

In the Walkers’ Beetle Bailey at the top of our first visual aid,

the complete absence of landmarks is something we find only in a comic strip