|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 421 (September 7, 2021). We’ve packed a lot into this posting in order to showcase Rancid Raves for visitors during Open Access Month when even non-$ubscribers can wander the environs. (And after you have, we hope you’ll $ubscribe.) This could be dubbed our Book Review Issue: we examine 19 of them, including Scoop Scuttle and His Pals, Two-Volume Biography of Basil Wolverton, Invisible Men: Black Artists of Comic Books, Marvel: The First 80 Years, DC Through the ’80s, The Joker: 80 Years of the Clown Prince of Crime, Stan Lee’s How To Draw Superheroes, and Steranko: The Self-Created Man. We also look at August’s editoons (over 50 of them), examine some newspaper funnies, and admire Preview’s pin-ups. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order (the longest entries are marked with an asterisk* — a reader’s guide to help you decide where to spend your time)—:

NOUS R US Reuben Nominees Comic-Con Museum To Open Ginger Meggs Gets Postal Stamp Great Places Crazy Anti-vaxxers Baker Honored Stan Lee Biographies Again

ODDS & ADDENDA Where Is Elizabeth Montague in The New Yorker

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of—: Groo Meets Tarzan No.1 Seven Swords No.1

EDITOONERY * Editoons on Cuomo, Afghanistan, the Vaccine and More

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Antics In the Funnies * Funky Winkerbean Sex in Blondie

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Previews Pin-Ups

Some More Gorey

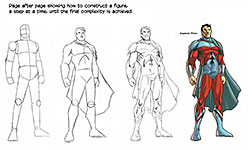

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews Of—: Scoop Scuttle and His Pals * Two-Volume Biography of Basil Wolverton Invisible Men: Black Artists of Comic Books I Think He’s Crazy: The Comics of B.K. Taylor Secret History of Marvel Comics The Marvel Vault: A Visual History Marvel Greatest Comics: 100 Comics Marvel: The First 80 Years Captain America: The First 80 Years Marvel Comics in the 1970s: Issue by Issue DC Through the ’80s The Joker: 80 Years of the Clown Prince of Crime Totally Awesome: The Greatest [Animated] Cartoons of the Eighties Stan Lee’s How To Draw Superheroes Draw Comics Like a Pro by Al Bigley Introduction to Cartooning by Richard Taylor Terry Moore’s How To Draw

BOTTOM LINERS * The Illusion of a Cartoon New Yorker Style

BOOK REVIEWS Long Essay about—: * Steranko: The Self-Created Man

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em.

But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics. AND— “If we can imagine a better world, then we can make a better world.”

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

National Cartoonists Society Announces Five Nominees for This Year’s Cartoonist of the Year Reuben ◆ Ray Billingsley’s comic strip, Curtis is syndicated

in more than 250 newspapers worldwide. The strip portrays the daily life of a

middle-class Black family living in an unnamed large American city, especially

that of the eponymous main character. It frequently chronicles aspects of

African American culture and history. Curtis has been compared to Li'l

Abner, which Billingsley cites as his favorite comic strip, in style. (In

content, I can’t see much to compare it to Li’l Abner; but what do I

know?) Billingsley’s excellent craftsmanship coupled with his ability to

connect his characters and readers has provided an indispensable element to

newspaper comics sections. ◆ Bill Griffith is a pioneer of the underground “comix” movement. His career has spanned decades and he has left an indelible mark across the entire comics idiom — comic books, syndicated comic strips and graphic novels. His comic strip Zippy stars Zippy the Pinhead and is recognized worldwide and is celebrated as equally absurd and profound. With his graphic novels, Invisible Ink, Nobody’s Fool, and his forthcoming graphic biopic of Ernie Bushmiller, Griffith has continued to cement his place in the pantheon of comics greats. See Harv’s Hindsight for July 2011 for the whole story (which includes the unusual circumstance of Zippy’s initial syndication). ◆ Terri Libenson (pronounced LEE-ben-son) is a New York Times bestselling children’s book author and award-winning cartoonist of the syndicated daily comic strip about family life, The Pajama Diaries, which was launched with King Features in 2006 and ran in hundreds of newspapers internationally until its retirement in January, 2020. The strip has been nominated four times for the Reuben Division Award for Best Newspaper Comic Strip and won in 2016. ◆ Hilary B. Price’s comic strip, Rhymes With Orange, is not about poetry. Drawing from her deep appreciation of classic magazine gag cartoons, comic strips, and picture books, Price has created something wholly original and forever made newspaper comic sections richer. It has been a stand-out for more than 25 years and has been nominated for a Reuben several times. ◆ Mark Tatulli is a comic strip writer/artist, animator and television producer, known for his syndicated comic strips Lio and Heart of the City (which latter he discontinued doing himself a year or so ago; the former, an exercise in weirdness, continues apace). Tatulli is also the author/illustrator of the middle-grade novel series, Desmond Pucket. Three books in the series were released: Desmond Pucket Makes Monster Magic (2013), Desmond Pucket and the Mountain Full of Monsters (2014/2015), and Desmond Pucket and the Cloverfield Junior High Carnival of Horrors (2016). He released a biographical graphic novel, Short and Skinny in 2018. It chronicles a summer in middle school in which he was inspired by the original Star Wars to make his own parody of the film, while dealing with navigating relationships with bullies, friends, parents and body image. It’s worth noting that this year’s list of nominees includes two women cartoonists. In an organization so determinedly masculine that all members were at first required to be “male,” a single female nominee would be cause for applause and cheering; two inspires a marching band. And the nominees this year include an African American, another circumstance not routinely encountered. But NCS continues to ignore whole vistas of cartooning—comicbooks and graphic novels among them—in its nominees. This year, as usual throughout its 75-year history, the nominees are all creators of syndicated comic strips. The winner of the Reuben will be announced on the weekend of October 15th 2021 on NCSFest.com.

COMIC-CON MUSEUM TO OPEN San Diego Comic Convention, the non-profit organization that produces the annual popular arts and culture celebration, has announced the start of construction on the new Comic-Con Museum in San Diego’s Balboa Park with the opening and daily operations set to begin November 26, 2021. The event will coincide with Comic-Con Special Edition, a reduced-sized fall version of the Comic-Con held each summer in San Diego. Said a news release: “The Comic-Con Museum will allow fans and the public to see exciting and fun exhibits, art, and images connected to comics and related popular art while serving as a meeting place for the community of fans and lovers of popular art in all its unique forms.” “Comic-Con may be a San Diego institution,” said San Diego Mayor Todd Gloria, “but people from around the world have eagerly anticipated this year-round home to celebrate the popular arts they love. With the Museum’s construction underway, we’re closer than ever to welcoming a global audience to get a taste of the Comic-Con experience in the middle of our City’s crown jewel, Balboa Park.” Two “classrooms” will open in November, and the Museum will continue to expand its interior display space and educational area over the next several months leading to a grand opening scheduled for July 2022.

A Scamp on a Stamp! Brand New Ginger Meggs Centenary Stamps from Australia Post In September, the Australia Post issued a commemorative stamp celebrating 100 years of the comic strip adventures of the much-loved mischievous, red-headed schoolboy, Ginger Meggs, who is still recognizably Australian in today’s globalized world. The stamp features the work of three of the cartoonists who have drawn Ginge since he made his entry onto the pages of Sydney’s Sunday Sun in 1921— Jimmy Bancks, James Kemsley and Jason Chatfield.

Young Ginge appears not just in the stamp designs but also in a host of philatelic products, including a minisheet, stamp pack, first day cover, a maxicard set and two stamp and coin covers, housing coins produced by the Royal Australian Mint.

GREAT PLACES With its August 2/9 issue, Time published its third annual list the World’s 100 Greatest Places. Of that number, 20—a fifth of the World’s greatest places— are in the U.S.: Savanah, Georgia (riverfronts), New York City (Broadway, Greenwich Village, and everything else), Napa Valley, *Houston (diverse city), Orlando (Walt Disney World), Las Vegas (excess), *Sarasota, Florida (cultural capital), New River Gorge (West Virginia), Island of Hawaii, Los Angeles (movie capital), Santa Fe (monument to the Southwest), New Orleans (Big Easy), *Philadelphia (artistic growth), *St. Louis (the arch?), *Indianapolis (bottle service?), Talkeetna (Alaska), *Hudson Valley (country charm), Memphis (music legacy), *Seattle (visions of the future), Big Sky, Montana—and, surprise!—Denver. Seven of them (marked with an asterisk) I question: Is Sarasota, Florida really that great a place? Compared, say, to New York City or some of the other places in the world— Loire Valley, France; Tuscany, Italy; Bangkok; Berlin; Christchurch, New Zealand; Tokyo; Athens; London (English history, an artistic incubator), Venice. To which, I’d add Barcelona and Cannes. And is Denver—my hometown and world headquarters of the Rancid Raves intergalactic wurlitzer—that great a place? Mostly because of craft beer and restaurants, it sez here. And that seems odd to me. Barely mentioned were the spectacular ranges of mountains just west of the city to which Denver is the gateway. Oh, well. They didn’t ask me. My list of great American places is only 12 or 13 places long. Rejoice and enjoy.

SO—WHAT DO YOU EXPECT, CRAZY ANTI-VAXXER? From New York Times, Sydney Ember and Coral Murphy Marcos—: For more than two months, Vincent Taranto, 31, was among the only employees at work required to wear a mask at his job because he was unvaccinated. Though he was wary of the vaccine and skeptical that he was at risk of getting seriously sick, he was concerned that his decision to avoid the shot had left him eposed to judgment from collegues. “I don’t’ want to look like the crazy anti-vaxxer to my co-workers,” he said.

BAKER HONORED France's presidential palace confirmed that Josephine Baker, a U.S.-born dancer and civil rights activist who became a French citizen in 1937, will be laid to rest in the Pantheon alongside other French heroes like Voltaire, Victor Hugo, and Marie Curie, according to The Week. Baker, who died in Paris in 1975 and is currently buried in Monaco, will be the first Black woman and first entertainer buried in the Pantheon, and only the fifth woman to earn that honor, alongside 72 men. Baker was born Freda Josephine McDonald in St. Louis, and she moved to Paris in 1925, largely to escape racial discrimination in the U.S. She became one of France's biggest cabaret stars, earning huge fame at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees then Les Follies Bergères for her songs and dance routines, notably her "banana skirt" dances. Baker joined the French Resistance during World War II, earning medals of honor for her work as an ambulence driver and intelligence agent. "Amid other missions, she collected information from German officials she met at parties and carried messages hidden in her underwear to England and other countries, using her star status to justify her travels," the Associated Press reports. Her civil rights advocacy included joining Martin Luther King Jr. on stage in 1963 during the March on Washington. See Opus 402 for a review of her biography in graphic novel form.

STAN LEE MAKES THE BIG APPLE REVIEW Two Stan Lee biographies—True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee by Abraham Riesman and Stan Lee: A Life in Comics by Liel Leibovitz —were reviewed in August 19 issue of The New York Review of Books by J. Hoberman. “Riesman and Leibovitz cover much the same ground,” says Hoberman, “but to read their books simultaneously is to invite whiplash.” He goes on, comparing the two: “Leivbovitz, who draws heavily on Lee’s autobiographical writing, is worshipful. Riesman is relentlessly debunking, if not desecrating. Leibovitz credits Lee with reawakening ‘America’s moral imagination.’ Riesman hammers on the notion of Lee as a credit thief. “Stan Lee’s life was nearly over, yet his time had come. There is a sense in which the so-called Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is the culmination of a trend that is close to half a century old. ... “The cultural cynicism associated with Vietnam and Wategate subsided. Reenchantment—the restoration of the ancient world’s gods and demons—ruled. Fantasy qua fantasy, which is to say the magic of special effects, was the movie industry’s new reality. ... Computer animation and revivals of Superman and Batman dominated the box office for the first dozen years of the new millennium. “In 2009 the Walt Disney Company purchased Marvel for $4 billion ... and set about elaborating Marvel’s nascent ‘cinematic universe,’ the movie equivalent of the cross-referenced comic books and self-enclosed world of Marvel’s reputation.” Hoberman is impressed with Marvel’s box office success. Three MCU productions—“Avengers: Endgame” (2019), “Avengers: Infinity War,” and “The Avengers”—are among history’s top ten highest-grossing films, with another two—“Avengers: Age of Ultron” (2015) and “Black Panther”—ranking eleventh and twelfth. Another three—“Iron Man 3" (2013), “Captain America: Civil War” (2016)l, and “Captain Marvel” (2019)—have each grossed over $1 billion. “Perhaps Lee was the Jewish Walt Disney, an internationally known brand whose associated characters lived on beyond the life of their skillful promoter. But a half-century after his death, Disney represented much more than Mickey Mouse or Disneyland. As the Disney Company all but cornered the market in American popular culture—something perhaps beyond Lee’s wildest imaginings—it became so voracious that, like the planet-devouring Galactus, it swallowed the Marvel universe whole.”

ODDS & ADDENDA In May 2020, the Washington Post conducted a mild celebration when The New Yorker published four cartoons by Elizabeth Montague, who was denominated the first Black female cartoonist to be published in the rigorously selective magazine; since then, I have noticed no Montague cartoons.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, who covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these three other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com (now operated without Gardner by AndrewsMcMeel, D.D. Degg, editor); and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO Trying to be happy by accumulating possessions is like trying to satisfy hunger by taping sandwiches all over your body.—Buddhist scholar Roger Corless

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

HOW IS GROO

GOING TO MEET TARZAN, I wondered when I saw that title crop up. It promised to

be visually unique— exciting— with Groo drawn by Sergio Aragones in his

usual manic manner and Tarzan drawn realistically by Tom Yeates, the

current artist on Prince Valiant. If I’d seen the earlier (2014) Groo

vs Conan by Aragones and Yeates, I would have expected the two styles to be

integrated in every panel, Groo and his crazy cast drawn by Sergio; Tarzan, by

Yeates—as the two did in the Conan book. Alas, fun as that sounds, pages integrating the two drawing styles were wholly absent from the first issue of Groo Meets Tarzan. The book offers three plotlines, each separate from the others. The pages telling of Groo’s search for the greatest cheese dip in the world and pages detailing Sergio’s and writer Mark Evanier’s comic-con adventures are drawn by Sergio. Pages about Tarzan’s angry search for a slave ship to destroy it are drawn by Yeates. The separation of styles ends in the next issue, the second, wherein we see pages drawn in both styles when Groo actually meets Tarzan. But in the first issue, Sergio and Yeates are separated. Hereabouts we’ve posted sample pages in their assorted styles.

The biggest treat in the book is the two-page spread aerial view of a comic-con exhibit floor, crammed with tiny Sergio characters doing their individual things as comic-con attendees are wont to do.

I ORDERED Seven Swords No.1 because I’ve missed cinematic sword fights lately. There haven’t been any, and I thought, surely, there’d be some good ones in a book with swords in the title. And, indeed, there are at least two herein. But sword fights in the static form of a comicbook are no match for duels in film. One of the best sword fights in movies is the one in “Scaramouche” with Steward Granger in the title role: he fights Mel Ferrer for six long minutes on the screen, the longest swordfight in movies. Most sword fights in movies take only two or three minutes: it’s difficult to find enough for duelists to do in a fight without repeating themselves too much and becoming, thereby, boring. This famously long duel takes place in a theater, and Granger and Ferrer move from the seats in the audience to the stage and back again a couple times, leaping in and out of box seats occasionally, too. Seven Swords offers more than one complete episode. In fact, there are too many episodes in this book: it’s difficult to reconcile them into a coherent story. The central thread is being unraveled by D’Artagnan, the fourth musketeer in Alexander Dumas’ iconic Three Musketeers. The other members of the trio—Porthos, Athos, and Aramis—are apparently dead, and D’Artagnan has spent the last five years looking for Cardinal Richelieu, who is responsible for their deaths. Treville, the captain of Dumas’ musketeers, thinks D’Artagnan is up to the job but not by himself: to take on Richelieu, D’Artagnan will need to recruit the best sword fighters in the world—which is what he’ll be doing in the forthcoming second issue. This much of the “story” dribbles out in a succession of episodes, punctuated by other episodes, which take place in different countries. This smattering of seemingly unconnected stories foreshadows the nation-hopping D’Artagnan will do in No.2 whilst recruiting the seven best swordsmen in the world (which group will include such celebrated swordsmen as Cyrano de Bergerac and Don Juan, who in their literary incarnations did not live at the same time). Writer Evan Daughtery, incidentally, does no better than Dumas at clearing up the presumed confusion inherent in a book about swordfighters: the three musketeers were members of a military group that fought with muskets, not swords. Like Dumas, Daughtery just ignores the problem. And, sure enough, it goes away. Another thing that goes away is D’Artagnan’s military career. In Dumas, D’Artagnan stays in the musketeers and eventually becomes captain and then marshal, the highest rank. In the midst of the confused tangle of different story fragments, D’Artagnan finds time for a romp in the hay with a couple of bawds, an episode concocted solely to give artist Riccardo Latina the opportunity to draw nekkid ladies. Which he does very well but the incident contributes nothing to the accumulating tangle.

Latina is a superlative artist, undertaking such daunting tasks as having D’Artagnan in a duel that takes place across the facade of Notre Dame, the details of which are complicated by a odd-angle composition. When I wonder why I’ve not encountered Latina before, I realize that he’s Italian and works in that country. I’ll be looking forward to No.2 to see who D’Artagnan will round up to join Cyrano and Don Juan in his crew of deadly swashbucklers.

DAUGHTERY’s D’Artagnon, the one romping in the hay with a couple ripe young women, reminds me of another D’Artagnan in the long literary history of the Three Musketeers. This one belongs to author Tiffany Thayer (1902-1959). Thayer wrote several novels, including the bestseller Thirteen Women which was filmed in 1932 and released by RKO Radio Pictures. Many of his novels contained elements of science fiction or fantasy. In the profile in Twentieth Century Authors, Thayer was described as "an atheist, an anarchist – in philosophy a Pyrrhonean – and regrets the legitimacy of his birth." He listed his hobbies as painting, fencing, and book collecting. Towards the end of his life, Thayer had championed increasingly idiosyncratic ideas, such as a Flat Earth and opposition to the fluoridation of water supplies. Among his novels is Three Musketeers (1939). But this Three Musketeers bears only the slightest resemblance to Dumas’ classic. It used many of the same characters, f’instance. But the resemblance just about ends there. I encountered Thayer’s musketeers while I was still in high school. I saw the title on the spine of a book in the school library, and, having a nodding acquaintance with Dumas’ characters, I pulled it off the shelf and opened it up. It fell open to page 144, whereupon D’Artagnan has a meeting the woman he will fall in love with, Constance Bonacieux. I knew nothing about their eventual relationship, however, upon reading the passage on page 144, to wit—: “I hope no one saw me come up your stairs,” worried the girl [Constance, not a “girl” exactly, as I soon found out]. “No one,” D’Artagnon assured her, plucking at the collar of her dress. Constance pushed his hands gently away. “Not now, monsieur. The Queen needs you.” “But not so much as I need you, madame. It must be now, before the others get here.” “Oh, you men!” said Constance, loosening her bodice for him. “You will spend half your lives compromising us so that the other half can be spent defending what you do.” “Sweet Constance,” said D’Artagnan, gazing at the breasts which lay like pink-nosed puppies in his palms, “would you have me do less than this?” The lady’s breath was shorter then. She did not answer him. Her fingers searched his hair as he leaned forward with parted lips. Softly, “You’re like a hungry boy,” she murmured. It was only a matter of seconds after that before D’Artagnan had done what little a man can do toward carving a niche in a woman’s memory.

RCH again: “Pink-nosed puppies”? Never in the ensuing 70 years of my existence so far have I forgotten that happy metaphor. I happened upon it, you’ll recall, when a teenager and thus particularly vulnerable to sexual metaphors. Or sexual similes. Or just rumors of sex. But the end-of-class bell rang just about then, and I put the book back on the shelf, and moved on to my next class. When I was next in the library (the next day), I’d forgotten, momentarily, the pink-nosed puppies. I remembered them again a few years later and resolved to find a copy of Thayer’s book for my own growing library. I eventually found and bought a copy (it was harder in those days to find a 30-year-old title even in the used book shops I frequented) in the attic floor of a bookstore in St. Louis. When I got it home, I inspected it. I found the pink-nosed puppies. And I also found on the first page of the book that the central character in Thayer’s Three Musketeers is not a musketeer: instead, it is Dumas’ villainess, the ravenously beautiful and thoroughly unprincipled Milady de Winter, who was “the vilest blonde on record,” who had been sent for her sins as a young woman to a convent, where, Thayer assures us, “She stood out. Her lips stood out. Her chin stood out ... Yes, yes ... Her confessor noticed them, too. Like half-grown melons, hard and energetic. The temptation was to test their ripeness with the fingers.” ... Melons and pink-nosed puppies. I have the book in my library. I’ve never read any more of it than I’ve just quoted here. Who needs more?

QUOTES & MOTS The earth is mostly just a boneyard. But pretty in the sunlight.—Larry McMurtry An onion can make people cry, but there has never been a vegetable invented to make them laugh.—Will Rogers Babies are such a nice way to start people.—Humorist Don Herold

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy IN THIS DEPARTMENT, we examine the ways editoonists manipulate images to give impact to their opinions. Take, for example, New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo, who resigned in disgrace because of allegations that he sexually harassed women. In

our first visual aid, Steve Sack offers a pair of images that show

people in rope lines waiting to use a microphone to express themselves on the

Cuomo issue. The images compare the two lines, which show that the line of

Democrantz wanting to condemn Democrank Cuomo is a longer line than the

non-existant line of Republicons who want to condemn the Republicon Trumpet for

the same offenses. By this measure, Republicons are clearly more partisan and

less objective in choosing objects to ridicule or complain about. Next around the clock, Dick Wright revives an antique image—a 19th century Thomas Nast picture of Boss Tweed as a bird of prey, crouched to pounce on his victims. For Wright, however, the bird preying is Cuomo, looking for women and the elderly to prey upon; his posture echoes that of Nast’s Boss Tweed. Thanks to the Nast image, Cuomo is condemned. The Biden presidency is coming in for a lot of Republicon criticism. Gary Varvel shows Biden confronting six different crises—and at each one, he’s waving a white flag of surrender. For Varvel, Biden is a loser. In somewhat the same way, Dick Wright is back again with a vivid image of Biden using a map to find his way—but his way leads off a cliff. And the Democrank donkey commiserates. The

U.S. departure from Afghanistan is the next topic, and Bob Englehart starts

us off with a picture of “dog days” (the last days of summer) in which Biden is

being pee’d on by various dogs—the GOP, the Democranks, and the news media—for

his policy of withdrawing from Afghanistan. Editoonist Rivers offers a fresh take on Biden’s exit strategy with Uncle Sam (all of us) pointing the way out for Biden—out of the picture. Gary Varvel’s interpretation of Biden’s exit strategy shows that it is no way out at all. Just an impassable brick wall. And those who can’t exit are, judging by their attire, Afghan civilians. Next, conservative Gary McCoy’s visual metaphor for the Afghans’ plight is a desert island, from which it is ludicrously impossible to reach the airport as Biden’s press secretary, Jen Psaki, advises. We’re

still leaving Afghanistan in the next array. Mike Luckovich’s image

shows Uncle Sam buried in Afghan quick sand with the American military trying

to pull him out. Next, Luckovich is back with another image for evacuation—this

time, Noah’s ark; or, rather, Biden’s ark, about which the news media is

forever complaining despite the obvious fact that many Afghans (pairs of

animals) are being safely evacuated. Then Jeff Danziger conjures a picture of ravenous Taliban and their plan for Afghan women and those who’d befriended and/or worked for American or allied forces. Next, Dick Wright’s image of a pathway over a mountain ridge shows Afghanistan taking women back to the 12th century by means of the restrictions the Taliban will place upon them. Still

on the evacuation of Afghanistan in the next display, Mike Luckovich returns

with a visual metaphor that reminds us of our departure from Vietnam via

helicopter from the roof of the American consulate. Then Joel Pett shows Uncle Sam leaving Afghanistan with cautionary advice that, ironically, applies equally to the U.S. Jimmy Margulies gets a little more specific on the same train of thought: with its new highly restrictive abortion law, Texas looks a lot like Afghanistan under Taliban rule. Saith cartoonist Darren Bell: “We spent 20 years propping up our puppet government in Afghanistan. Just weeks into our withdrawal, the Taliban is reportedly overrunning the country and may be on the verge of taking Kabul. This is strong evidence that we wasted $2 trillion, two decades and countless lives.” Bell is singing the national chorus. Those who comment on the loss of Afghanistan all say about the same: we wasted 20 years and blood and treasure there. Well, yes. And no. As The Week magazine points out (September 3): “Afghan cities are modern metropolises with educated workforces, thanks partly to U.S. investment of more than $144 million in Afghan reconstruction.” So the country is better off than it was 20 years ago. And the future is scarcely bleak. “More than three out of four Afghans are under age 25 and have no memory of life under the Taliban. These urbanites will not easily submit to [the Taliban’s] medieval rules and repression. The

other hot topic lately concerns the vaccine everyone should be taking in order

to help us all escape the Covid-19 virus. Mike Luckovich takes five

panels in comic strip format to lead an anti-vaxxer to his just desserts, which

he achieves by listening to and obeying Fox News. Finally, Luckovich attends to another aspect of the anti-vaxxer crusade with his visual metaphor of the three bears in a hospital ward. All members of the bruin trio are in need of care, but no care is available because the unvaccinated have selfishly taken up all the beds. If the unvaccinated had taken their shots instead, everyone would be in better shape. And now, it’s time to take a Break!

RIGHT! Time to

sit back and take a breather from all the agonizingly exhaustive analysis of

political image-making, and, Now, sit back and relax. Take your time. Some of these toons take a couple minutes to assess and understand. Enjoy.

BACK TO THE

FRAY where Mike Luckovich begins our next Editoonery exhibit with an

image of an emergency care facility. Surrounded by Covid-19 sufferers, the GOP

governor ignores the obvious danger to preach on a topic that doesn’t threaten

anyone in his venue. David Horsey lines up two for us. In the first, he ridicules two Republicon governors whose permissive policies about mask mandates create opportunity for the Delta Variant, which appears in the shape of Death in this editoon. In the next, a couple of Fox celebrities discover that the virus is “ripping through Red America”—killing their own audience. In

our next visual aid, Steve Sack’s visual metaphor of a traffic jam

condemns Florida governor DeSantis’ a-borning presidential campaign. The

traffic jam is caused by a plethora of hearses all bearing away the bodies of people

killed by Covid-19—evidence that DeSantis chooses to ignore so busy is he in

appealing to anti-vaxxers. (Yes, I know: there are two too many “the’s” in that

speech balloon.) Jeff Danziger’s back to school cartoon is a haunting

image of a dark and forboding forest that students enter hesitantly, not

knowing what to do about masks or vaccines or what. Flight attendants are being assaulted by anti-mask people who refuse to obey the air travel industry’s requirement that everyone wear a mask; something in the neighborhood of 3, 509 incidents so far this year, and Dave Granlund’s imagery demonstrates what is needed next—protective gear for the flight attendants. Then David Fitzsimons has a little fun with the popular image of Batman foe, the Joker, who is usually in pursuit of some scheme of uninhibited evil, at which the Joker giggles. The person the Joker is talking with is probably the governor of Arizona. Note Fitz’s mascot, a prairie chicken of some sort—who’s on the Web with Darth Vadar, another symbol of evil.

CLIMATE CHANGE

preoccupies the editoonists we’ve chosen for the next array. In the first, Jack

Ohman recognizes the fossil fuel industry as causing the forest fires that

are consuming the landscape in California and the Pacific Northwest. At the

same time, however, in Ohman’s fantasy, the fossil fuelers are providing a cure

for the fires. Next, Nick Anderson’s image of a nearly empty audience at a lecture about climate change includes two people who realize the futility of the program the speaker suggests. As a people, we’re not likely to “accept reality and work together for the common good.” Alas. In

our next display, we take up the matter of the January 6 insurrection. Mike

Luckovich offers vivid imagery of the kind of Republicons that House

minority leader Kevin McCarthy wants on the investigating committee. Just the

sort of people who are certain not to find any GQP culprits—in short,

participants in the insurrection itself. Then Mike Luckovich is back with three panels whose imagery shows how to disrespect the national flag. Our hero is shown taking possession of the flag and then, in the last panel, planting it forcefully on one of the Capital Police during the insurrection. Again, it is the Republicon hypocisy that is being ridiculed: whatever the GOP is against in one context, it approves of in a different context. Luckovich returns for the last editoon. I thought it was a clever idea even if I don’t know what it means. Did Liz Chaney lose her shoes during the January 6 insurrection? Dunno. The

infrastructure bill is the topic editoonists address in the next round of

editoons, beginning with Mike Luckovich and Charles Schulz. Luckovich

uses Schulz’s creations as images to comment on the miraculous passage of the

infrastructure bill. Usually, as Peanuts fans everywhere know, Charlie

Brown fails to kick the football because Lucy pulls it back just at the last

moment, and Charlie swings and misses—and falls on his back, a failure as

always. Lucy’s traditional maneuver fails this time, which underscores the

miraculousness of the situation. The miraculousness of the bill’s passage is again emphasized by Bud Plante, whose metaphor for the miracle is hell freezing over, a circumstance that has traditionally permitted all sorts of unusual things to happen. Then Barry Blitt characterizes the Republicon Party as full of toxic, lying, dishonest sexual predators—which, given the number of the accused, is probably as accurate as we can get in political circles. And then Mike Luckovich is back with the symbol of the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm drained of all color, its whiteness in stark contrast to the diversity of the general population, which is “more diverse than ever.” With that, we’ve come up on another Break!

PERHAPS THE

JOKES are self-evident except, maybe, the Donner Party gag. The Donner Party

got stranded in the Now, back to work.

IN KEVIN “KAL” KALAUGHER’s stunningly vertical 3-panel editoon, the Republicon elephant is

shown to be slavishly obedient to the will of the Trumpet. Next around

the clock, Nick Anderson addresses the Trumpet’s hopes for being

reinstated as Prez, come August. Instead, it’s the virus that is reinstated,

surging once again. Then Rivers (who declines having a first name) shows us a journalist rejoicing in his ability to mislead his readers/viewers with “fake” news. Next, Clay Bennett also deals with the “reinstatement” mythology, deploying as his metaphor characters from Charles Schulz’s Peanuts who are awaiting the arrival of the Great Pumpkin, Linus’s invented “holiday” that never happens. Although Schulz never made a big fuss in public about other cartoonists using his characters (once you’ve invented a national institution, you’ve lost control of it), he didn’t like it— chiefly because readers would assume the attitude “his” characters adopted in an editoon was Schulz’s attitude. And it often wasn’t. We

continue to thrash around in “miscellaneous” for the next exhibit as Dave

Whamond recognizes the space flight antics of three billionaires, Richard

Branson, Elon Musk, and Jeff Bezos, which he does without metaphor. Each of the

billionaires, seeking to avoid criticism for using their billions to entertain

themselves instead of helping the needy, offers to do something helpful. Phil

Hands’ image of two people up to their necks in 390 million guns reminds us

that gun violence is still with us. Yes, with that many guns in private hands,

violence is inevitable. We

start the next visual aid with a comic strip, untitled and unsigned. But I love

the drawling and the message. Bill Bramhall is next with an ironic image

of a thoroughly untoughened slob who has no right to be in the same room as a

tv set showing a picture Simone Biles let alone to offer her advice about

fitness. Next Lalo Alcaraz (left) and Jeff Danziger (right) take a look at the new Texas anti-abortion law. Alcaraz sees no difference when comparing Taliban Afghanistan and Republicon Texas on the way women are treated. And Danziger sees Texas as a rodeo in which a MAGA mounted cowboy chases after women with a lariat marked “abortion law.” Knowing,

as I do, David Horsey’s penchant for drawing the curvaceous gender, I

was not surprised by the editoon of his that kicks off our next display. I

don’t understand the cartoon; I don’t know what its target is. But it is an

adequate demonstration of Horsey’s ability to limn the ladies, so I’m including

it here chiefly as an excuse to make the preceding observation. And to

encourage Horsey in this vice. That’s all. Horsey takes up a more serious matter with the next editoon. Homelessness. The image shows the homeless guy definitely in the lady’s way with the heap of all his worldly belongings; but if she wants less clutter in the streets, she’ll have to do something to fix homelessness. Next, Joel Pett’s picture of a couple of homeless guys, one of whom is addressing the infrastructure issue even as he is camping out as a homeless person. Presumably, he is a conservative, opposed to camping out as a life style. But he’s forced into it even as he objects to “do-good liberal wish lists.” His ideology blinds him to the communal good that might be achieved. And that has become the story of the Republicon Party. It has demonstrated repeatedly of late a tendency to take political positions that are not supported by facts or any other representation of reality as the rest of us know it. Theirs is a fantasy world with fantasy factoids. And the positions the GOP is forced, by its ideology, to take are likely to make the rest of the world laugh and point. Except that the Republicons with their fantasies are in power in many states, building another reality that is an insult to rationale beings. Sad. Take, for example, Critical Race Theory. Critical Race Theory advocates teaching America’s racial history with all its shameful faults. So far, CRT is taught only in colleges and universities and law schools, not in the lower grades. But parents have got wind of it and are objecting in great number—even though CRT is not being taught in their children’s schools. Steve Sack offers an image of two silly-looking people busily erasing America’s race history in the belief that “if they can’t teach it, it never happened”; these are the people who object to CRT—or any history that does not conform to their happy beliefs. In

our final exhibit this time, we have David Horsey again, this time with

a picture of a telephone-using citizen being attacked by robocallers. Next, Bob Englehart musters a crowd of sign-holding protesters, the image and the messages on the signs showing what can happen next if schools agree to unmask the students. Banning masks is the first step and unbuckling their seat belts is the next. And after that? Jeff Koterba has concocted the a vivid image to describe America’s disorderly departure from Afghanistan with Uncle Sam struggling to sustain an “eXit.” Then Tom Stiglich, having run across two notables who actively advocate not bathing, resorts to Charles Sculz’s Peanuts, resurrecting Pigpen, the little kid who is always dirty, to poke fun at the anti-bathers. And we already know what Schulz thought of such piracies. And

now, to finish this Department this time, here are a few carton covers from the Washington Examiner, a staunch conservatives magazine with an excellent

cartoonist on staff. His caricatures are sometimes a little off the mark but

still Still, it’s better than The Week is doing lately. Long my magazine idol for its full-color painted political cartoon covers, the magazine has recently resorted to serious subjects like the fate of Afghans left behind—with accompanying serious illustration— no caricatures. My hope is that this situation will change soon, and that The Week will return to caricaturing for freedom.

READ & RELISH There are three sides to every story: your side, my side, and the truth.—Movie producer Robert Evans One of the difficulties of being alive today is that everything is absurd but fewer and fewer things are funny.—Alexandra Petri

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping Cartoonist Tom Batiuk returns frequently in his Funky Winkerbean strip to Lisa’s Story, a book both in real life (reprinting a sequence from the strip) and in the strip about the death of Les’s first wife, who died of cancer. The book (and Lisa) are always good story material (and the stories incidentally plug the real life book). This week, Les and his current wife are going to Los Angles to see the movie someone has made of Lisa’s Story. Today (August 4) we find out that they’re staying at the Chateau Marmont. Sure

enough, the Chateau is a real hotel on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles. Opening

in 1930, the hotel was modeled loosely after the Château d'Amboise, a royal

retreat in France's Loire Valley. The hotel has 63 rooms, suites, cottages, and

bungalows. And it’s expensive. The hotel is known as both a long- and short-term residence for celebrities – historically "populated by people either on their way up or on their way down" – as well as a home for New Yorkers in Hollywood. And the Chateau is notorious for some celebrity adventures that took place therein. John Belushi, for instance, died of a drug overdose in Bungalow 3 in March 1982. In 2020, the hotel announced plans to become a members-only hotel. So I don’t think the Chateau needs a plug in Funky Winkerbean to advance its fortunes. And the hotel is good story material (like Lisa’s Story) whether or not its presence in the strip amounts to a plug. But I don’t see why Les’s wife needs to go shopping again. And nothing in the strip so far has given readers any hints about what sort of place the Chateau is. Presumably, she needs a fancier wardrobe if she’s going to stay at the Chateau and hobnob with celebrities. Is there a movie in the works for Lisa’s Story? Dunno. But it wouldn’t surprise me if there were. The rest of the accompanying visual aid shows Les watching on television an excerpt from the movie “Lisa’s Story” and, below that, an exchange between Les and a highschool classmate.

THE NEXT Funky

Winkerbean strips are an overt plug for the health benefits that reading Lisa’s

Story could produce. (Health? Life or death, really.) The book, reprinting

the sequence from the strip about Lisa’s cancer, was widely applauded when it

was published—as was the strip when it published the original cancer storyline

that was subsequently made into the book. The last two strips here make the

case for the value of the book, something so self-evident that we assumed no

elaboration to be necessary. For our next display, we picked strips that demonstrate “only in the comics” can certain things happen. The first joke, in Chad Carpenter’s Tundra, pretty obviously couldn’t happen in any other medium. Ditto Liniers’gags in the two Macanudo strips that follow. Liniers pretty consistently exploits the nature of the medium for comedy. Robb

Armstrong’s Jump Start is here for a different reason: the verbiage

in the second panel has nearly crowded the picture out of existence. That’s a

risk anytime a cartoonist needs too many words for his joke. Armstrong’s risk

is higher, though, because his lettering is larger than the lettering in many

strips and therefore consumes more precious space. The two Pluggers panels by Rick McKee I clipped out because of their inherent “wisdom” or insight into our flawed but durable humanity. The byline names Gary Brookins but I don’t think he has much to do with the cartoon anymore: McKee inherited it.

FOR OUR NEXT

OUTING, we ponder Blondie, the deathless comic strip and what it means.

The first strip here self-consciously draws attention to the single large

button that has decorated Dagwood’s shirt front for decades. That button is a

remnant of the days when Dagwood, as scion of a wealthy family, usually wore a

tuxedo; the button conjured up the dress shirt he wore. Over the years, the

origin of the button slipped out of public consciousness, and Dagwood was

disowned by his father because he married a flapper, Blondie. Dean Young, who “manages” the strip (picking the gags), and John Marshall, who draws the strip, put Dagwood in the barber’s chair regularly—so they can make jokes about his cowlicks. I don’t know who Morelli the barber is named after, but I bet it’s a real life friend of Young’s. One of the regular gag situations in the strip involves the postman. In Dagwood’s town, the postman is still making his rounds, door-to-door, delivering the mail “in person” so to speak, on foot. In how many towns does that still happen? My guess—not many. Next,

we take up the subject of sex, sex appeal, and Bondie’s bosom. In the first

strip, notice that the shoulder strap of Blondie’s nightgown has slipped off

her shoulder. Very sexy. And you thought this strip was too clean-cut for sex.

Wrong. Sex has always played a part in the strip. Chic Young, the creator of Blondie, insisted from the beginning of the Bumstead marrige that Dagwood and Blondie share a double bed. In most movies of the period (early to mid-1930s), married couples slept in twin beds. Young would have none of that silly posturing. They were married; they’d share a double bed. More sex appeal as Dagwood outlines Blondie’s size and shape. And then, there’s Blondie’s bosom, generously displayed in the next strip. It was Frank Cho who drew my attention to Blondie’s generous endowment. Frank was getting some heat from his syndicate with his earliest strips featuring Brandy, the buxom beauty who is Liberty Meadows’ heroine. Her bosom was too, er, obvious. And the stretch wrinkles in her shirts indicated too obviously her better-than-average dimension. The syndicate insisted that Frank tone it down; so he did. But in discussing the matter with me, Frank pretended that he couldn’t understand his syndicate’s restrictive attitude about Brandy’s boobs. Other strips got away with healty hooters on their babes.“Look at Blondie!” Frank would say. “She’s pretty well developed.” And she is indeed. Why we never notice it, I can’t say. In the last strip, Dagwood’s boss’s wife appears, a happenstance I include here mostly to compare her bust size to Blondie’s. Mrs. Dithers is clearly more buxom in a middle-aged sort of way. But Blondie approaches the Dithers dimension albeit perkier. In the two preceding panels, notice Dagwood’s legs. Long from hip to knee; short from knee to ankle. Ditto Mr. Dithers—and, in fact, every male character who wanders through the panels has anatomy like this. And then—what’s that extra panel doing at the end of the strip? Well, it’s not part of this strip: it’s the concluding panel of another strip, and the two concluding panels are, as you can tell, identical. Clearly John Marshall was taking a shortcut by tracing that first last panel. That’s no sin, kimo sabe. If I were producing a comic strip with the kind of detailed backgrounds that Blondie offers, I’d be eager to take shortcuts, too. And that’s enough for this week.

TICS & TROPES From David Ignatius—: Biden is being flayed both for his decision and its sloppy execution. Many of us had warned that by withdrawing the small remaining force too quickly, without a transition plan, he was unwisely ending a low-cost insurance policy against the disaster now unfolding. Biden owns the final decision, for better or worse. But the hard truth is that this failure is shared by a generation of military commanders and policymakers, who let occasional tactical successes in a counterterrorism mission become a proxy for a strategy that never was. And it was subtly abetted by journalists who were scratching our heads wondering if it would work, but let the senior officials continue their magical thinking.

CLIPS & QUIPS What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult for each other?—George Eliot What’s the best way to prevent infection from biting insects? Don’t bite any. The harder you fall, the higher you bounce.

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words ONCE MORE, in the most recent issue of the Previews catalogue from Diamond, we have the pin-up section—namely, Dynamite, which publishes the industry’s most lavish collection of nearly barenekkidwimmin. The subject of day’s sermon, however, is the costuming of the pin-ups not their epidermises. The most venerable of the coverings is doubtless the bikini worn by Bettie Page, who is showing up lately in her own comicbook even though her clothing is so antique as to be positively discrete. Next in age is probably that worn by Elvira—a simple slit-skirt gown with a deeply plunging neckline. Then comes Red Sonja in a traditional bikini but one made of dimes. The separate parts of the bodice hang over her hooters, one at a time, covering enough for decency without concealing much.

Then we have Barbarella in a skin-tight body suit of lusty red. And Dejah Thoris—who is just plain naked. The most recent addition to the line-up is Jennifer Blood, whose gray costume is as skin-tight as Barbarella’s but with a plunging zippered neckline, which, unzipped to just below the breasts, speaks volumes about the costume and her anatomy: the costume is so tight that she can’t get it zipped up because her bosom is too ample for containment. The last pic on this display is, I confess, a drawing of mine, which permits—nay, demands—a diverting explanation.

LATE IN 1978—during my short career as a magazine gag cartoonist—Arv Miller, editor and publisher of Fling (a “men’s magazine” to which I’d sold an occasional girlie cartoon), asked if I’d be interested in doing a regular feature starring the magazine’s “mascot”—a sultan, whom Miller called “The King of Fling.” I made some sketches, envisioning a sort of dirty-old-man sultan who, despite his erotic yearnings, couldn’t keep up with his harem’s appetite for service. The fun would be in the juxtaposition of the worn-out old man and a bevy of ravenous near-naked beauties. I’d

settled on the fat old geezer shown at the lower right of our last visual aid

as the object of a harem girl’s passion So why, exactly, is this moment in my dissertation on Dynamite’s pin-ups the moment to discuss the Prince of Poon? It has nothing to do with content. I just had a fourth of a page to fill with an illustration and chose the worn-out old sultan drawing because I like the drawing. And that, of course, required all the rest of this highly informative detour. That’s now over. We’ve finished with it. Back to the previous discussion, so rudely interrupted—:

BUT THE MOST INVENTIVE of the Dynamite pin-ups pin-wear is Vampirella’s. She wears a specially tailored bikini-style garment with straps that leap up from their attachment to her bikini bottom to cover her breasts, separately, and then join at the back of the neck. This is entirely acceptable clothing for revealing anatomy without revealing the naughty bits. But it is also entirely impossible, as a quick examination will reveal.

The red straps that cover her boobs seem to be tucked in underneath each breast—in effect, the “weight” of the breast keeping the strap in place. No female garment can behave in this way. It would never stay in place. Our second Vampirella illustration argues for a much more realistic arrangement. Here, the straps simply stretch across the breasts, as our illustrations dramatically demonstrate. Better to be at least vaguely realistic in such monumental matters as mammaries.

SOME MORE GOREY The next couple of paragraphs you can find in Harv’s Hindsight on Edward Gorey, September 5, 2001. But as you wend your way downward you’ll find excerpts from The Admonitory Hippopotamus, which were not included in the original posting. Dunno why. So—for the eternal and immutable record, here they are. And following those, we’ve posted a sellection of Gorey artistry, more than the paltry few that decorate the Hindsight piece. Enjoy. The pictures in some of his books are as unembellished as Japanese prints, but Gorey’s characteristic manner is to garnish his drawings with meticulous hachuring and pointillist cross-hatching, so intensely applied as to be almost painful in its exquisite punctiliousness. (“It’s partly insecurity,” he once explained: “I mean, where do you leave off?”) This technique plunges his fictional milieu into deep fustian shadow, giving the stories a vaguely sinister, melancholy menace. Contributing to the ambiance is Gorey’s parallel text of hand-lettered laconic declarative sentences (sometimes in rhyme) that relate the most disturbing events in an almost elliptical fashion. In The Loathesome Couple (1977), the titular pair kidnap a young girl and spend the better part of a night “murdering the child in various ways.” The Curious Sofa (subtitled “A Pornographic Work”) includes the immortal line, “Still later Gerald did a terrible thing to Elsie with a saucepan.” In The Admonitory Hippopotamus (unpublished at the time of Gorey’s death), five-year-old Angelica playing in a gazebo suddenly sees a spectral hippopotamus “rising from the ha-ha.” “Fly at once,” commands the hippo; “all is discovered.” Returning as a chorus, the hippopotamus induces Angelica to act. “She remembered the novel with yellow covers at the bottom of the laundry bag. She jumped on a tram, and was noticed only at closing time in a distant cinema. Subsequently at other choruses, she remembers a packet of letters up the chimney, the emeralds in the cold cream, a screwdriver in the well, and broiled champignons veneneux on toast. She pedals off on a stolen bicycle, drives away in her host’s Panhard-Levassor, and follows an inflatable raft overboard. But at the end, “... she could not remember what it was he meant. Her body fell lifeless on the bed. Angelica road away on the back of the hippopotamus.” Gorey left this narrative without illustrations. Drawing a ha-ha was perhaps too much of a challenge.

As I mentioned in the last illustration, the Doubtful Guest, the mysterious visitor in one of Gorey’s books bearing the character’s name, has been immortalized in a pinch button by Arcane Vault. Just ten bucks. Search for ArchaneVault.com, then when you get there, click on Edward Gorey and then scroll through the merchandise until you get to the Doubtful Guest pinch button.

PITHY PRONOUNCEMENTS The dictionary site Merriam-Webster.com reported a 30,500 percent surge in searches for the German-derived word “schadenfreude” the day that Prez Trump tested positive for coronavirus. Merriam-Webster defines “schadenfreude” as “enjoyment obtained from the troubles of others.”

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. When Amy Coney Barrett made it to the Supreme Court, she was confirmed by GOP senators from states containing far fewer Americans (153 million) than those of the Democratic “minority” (168 million). The white, rural slant of the Senate, where Wyoming’s 58,000 residents have the same two votes as 39.5 million Californians, erodes the credibility of the Senate and the judiciary.

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. And that’s about what you’ll see here, beginning with—:

Scoop Scuttle and His Pals: The Crackpot Comics of Basil Wolverton Edited by Greg Sadowski 192 8x10-inch pages, color; 2021 Fantagraphics Books paperback, $29.99 NO SANE PERSON can be exposed to Wolverton comics for more than ten minutes without going blubberingly —happily— nuts. Wolverton litters his work with alliteration, and he delights in word play— bad rhymes and worse homophones and delicious puns, often in signage that plasters the panels— and sight gags, groaners all. The panels of a Wolverton comic are crammed with verbal contortions and visual exaggerations that overwhelm whatever “story” exists with endless prompts to laughter. And we love ’em. Sadowski, who has produced a two-volume, heavily illustrated biography of Wolverton (about which, more anon), has collected in this volume four of the most outlandish Wolverton creations—Scoop Scuttle (a reporter), Mystic Moot (a magician), Bingbang Buster (a cowboy lawman), and Jumpin’ Jupiter (space traveler). And Sadowski has helpfully dated and annotated wherever appropriate.

Knowing that is not enough Wolverton for would-be Wolverton fans, Sadowski has also included Wolverton’s article explaining sound effects; for instance—here is the sound of a pinheaded person pulling pate out of pop bottle, “Foink!” Here’s the sound of a glass eye falling into tomato soup: Ploop! Glass eye falling into clam chowder: Ploomp! Falling into a pitcher of thick syrup: Ploff! Or the sound of a man sitting on a small tack: Squinch! On a long tack: Squonch! Surely that’s enough. Need more? Read Wolverton.

If you want to know more about Wolverton, visit Opus 238 which reports on Wolverton’s Bible, and Opus 259 that discusses his other work and his life. And then there’s Sadowski’s massive biography of Wolverton, reviewed next, to wit—:

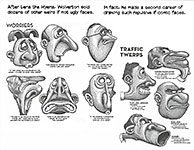

Creeping Death from Neptune: The Life and Comics of Basil Wolverton Volume One, 1909-1941 By Greg Sadowski 304 8x11-inch pages, color; 2014 Fantagraphics Books hardcover, $39.99 Brain Bats of Venus: The Life and Comics of Basil Wolverton Volume Two, 1942-1952 By Greg Sadowski 450 8x11-inch pages, color; 2014 Fantagraphics Books hardcover, $44.99 ONE OF THESE VOLUMES by itself is doorstop hefty; two together are massive, the stuff of alpine mountaineering. Each volume is divided into chapters, and in each chapter the narrative text is followed by “art pages” that reproduce the comics Sadowski references in the narrative; annotation supplies context for all the art. The narrative is also accompanied by illustrative matter to which, everywhere in the book, the page size gives ample display. For his narrative, Sadowski relies upon two sources. Wolverton kept the letters he was sent by editors to whom he submitted cartoons and comic strips, starting while he was a teenager. Alas, he did not keep copies of his own letters, so all we have is the negative side of his experience—the letters that rejected his work. The letters often provide detailed criticisms, and Sadowski quotes extensively from them, giving Wolverton’s life the career tilt that it enjoyed throughout: he was always concocting new characters, new situations, despite being regularly rejected (at first). Sadowski’s other chief source is a daily diary that Wolverton began in January 1941 when he was 32. In it, he reports his daily activities and keeps a record of sales and projects. Together, Sadowski’s two sources provide a detailed record, and by quoting from it at length, Sadowski gives this biography unequaled depth and insight. Quoting from the back covers of the two books: “Basil Wolverton was a commercial oddity, a one-man art factory, and a major influence on the underground comix movement. ... [These two volumes compile] Wolverton’s Golden Age science fiction, superhero, and humor stories, freelance illustrations, and unpublished artwork [and rehearse his childhood to adult life] as newspaperman, vaudevillian, cartoonist, broadcaster, persistent contest enterer, and local pastor of [Herbert Armstrong’s] Radio Church of God.” Growing up in the Pacific Northwest, Wolverton drew his first cartoons when he was four years old: he drew circles and ovals. He copied comic strip characters and wrote stories; Sadowski includes copies of scripts and sketches. At the age of 11, Wolverton sold copies of a weekly cartoon featuring a famous comic strip character; at 16, he tried to sell cartoons to a syndicate. He learned how to cartoon by copying—pretty much the way all cartoonists learn. At 19, Wolverton was a vaudeville performer, and he began a two-year career as a news reporter for the Portland News.

All the time, he was inventing comic strips and trying to sell them into syndication; none made it, but many he re-tooled for publication by the nascent comic book industry. In 1927, he’d concocted his first humor strip, Woozy Woofer, about a dog. His most famous creations of this period—Space Patrol and Spacehawk—were in print by the end of the 1930s. By 1938, Wolverton was doing Disk-Eyes the Detective, a somewhat wild comedic treatment of crime, punishment, and law enfarcement. And others. Always, and others.

He was always coming up with new features starring heroic characters—Meteor Martin, Hap Hunter, Crash Carver, Monsterman, Rockman, Dr. Dimwit, Dr. Slash, Bingbang Buster, Powerhouse Pepper. Wolverton’s science fiction strips were always cloaked in the evocative solid blacks of the stratosphere. And pictures of people are outnumbered by pictures of rocketry. Most of the people are talking heads; very few people are pictured at full-length.

Wolverton achieved lasting fame in the fall of 1946 when he won a contest Al Capp ran in Li’l Abner. Capp had introduced a character named Lena the Hyena, who was so horrifyingly ugly that Capp refused to draw her. Instead, he asked readers to send in their portraits of Lena. Wolverton, who had been drawing outlandish faces for quite some time, submitted seven, one of which won. And with that, Wolverton secured a niche in the history of cartooning that no one has matched. Naturally, Sadowski includes in Volume Two Wolverton’s portrait of Lena. And of numerous other alarming visages. Once he became known for weird faces, Wolverton’s future was made.

Both volumes are copiously illustrated with materials often on loan from champion collector Glenn Bray’s extensive Wolverton holdings. And Basil’s son Monte (himself a cartoonist— of the editorial variety) also contributed, making this two-volume work one of the most impressive cartoonist biographies around. Massive, as I said.

Invisible Men: The Trailblazing Black Artists of Comic Books By Ken Quattro; Introduction by Stanford W. Carpenter 248 8.x11-inch pages, color; 2020 IDW’s Yoe Books hardcover, $34.99 THIS BOOK EMBRACES the wonderful irony of Black comic book creators, who live on both sides of the color line, shifting back and forth between their lives in Black communities and their professions working as cogs in a very White machine “crafting fantastical stories” unattributed, “rendering their comings and goings all the more ... invisible,” saith cultural anthropologist Carpenter in his Introduction, which he concludes with yet another screaming irony when he speaks of “Black men making a living drawing idealized images of White women to satisfy the sexual desires of White men, some of whom would lynch a Black man for looking at an actual White woman” like those he drew. A more ambitious project than Dan Nadel’s Black Cartoonists in Chicago (see Opus 419), Invisible Men presents short biographies and sample art for nearly two dozen Black artists/cartoonists (only one of which Nadel mentions, Jay Jackson). In the line-up below—a complete list of the Blacks covered in Quattro’s book— I’ve identified at least one work by each of the persons named wherever possible; where not possible because Quattro doesn’t mention any such continuing title/character, I’ve noted simply their generic endeavors. In neither circumstance, however, are my notations by any means complete for the work of any of the artists/cartoonists. Matt Baker worked in mainstream comic books longer than any of the others named below. The list—:

Adolphus Barreaux Gripon (Adolph Leslie Barreaux), Sally the Sleuth Elmer Cecil Stoner, Blue Beetle Robert Savon Pious, editorial cartoons and comic book stories Jay Paul Jackson, Bungleton Green, Tisha Mingo (Black newspaper comic strips) Owen Charles Middleton, editorial cartoons and comic book stories Elton Clay Fax, They’ll Never Die (panel cartoon), posters George Dewey Lipscomb (writer), George Washington Carver, Target Comics stories Clarence Matthew Baker, Phantom Lady, Canteen Kate, Flamingo, Voodah Alvin Carl Hollingsworth, comic book stories Ezra Clyde Jackson, comic book stories Alfonso Greene, comic book stories Eugene Bilbrew, Jules Feiffer’s Clifford, Irving Klaw’s girlie pix Orin Evans, George Evans Jr., William H. Smith, Leonard Cooper, staff of All-Negro Comics John Terrell, Ace Harlem in All-Negro Comics Calvin Levi Msassey, Timely (Marvel) Comics, Warren In addition, in his preface, Quattro mentions E. Simms Campbell (see Harv’s Hindsight, May 2013), George Herriman (Krazy Kat; see Hindsight, November 2013) as well as Matt Baker briefly.

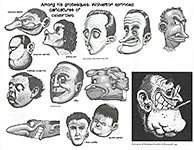

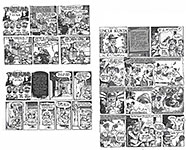

I Think He’s Crazy: The Comics of B.K. Taylor By B.K. Taylor; Foreword by Tim Allen; Backword by R.L. Stine 115 8.5x11-inch pages, b/w 4 pages in color; 2020 Fantagraphics hardcover, $22.99 TAYLOR PRODUCED THREE COMIC STRIPS for National Lampoon, starting in 1975 and running through the eighties and, perhaps, into the nineties. Because the magazine was a somewhat satirical effort, you might expect the comic strips to be satirical, too. But they aren’t. They are just, simply, outrageous with no redeeming social value whatsoever. The first strip was The Appletons with husband Norm, wife Helen and two kids, and it looks like a Norman Rockwell family. Except it isn’t. Norm is always playing practical jokes on people. He’s the kind of guy who disappears after dining with his family in a restaurant, leaving his wife to pay the bill, but his mother gets even in the next strip by throwing Norm over her shoulder and down the stairs. On another occasion, he waits until his wife is in the shower, then kidnaps her, ties her up and, putting a towel over her head to blindfold her, puts her in a taxi headed for the airport. We can only speculate at what happens when she gets there. Another strip, Timberland Tales, was set in Canada. It also had a family in it, but it starred a pre-adolescent orphan member of the family, Maurice, whose efforts to find himself often resulted in tragedy for someone, often a resident Canadian mountie named Tom. Then there was Uncle Kunta, which starred an elderly Black who, in the fashion of Uncle Remus, told stories to the neighborhood kids (who were white). This was the kind of satire that will get a cartoonist in trouble. The strips were usually full-pagers, and they were usually black-on-white, no color. They ran, Taylor tells us in his Introduction, alternately in the magazine from issue to issue. Hereabouts are samples from each of the strips.

MARVEL GETS CARRIED AWAY WITH ITS OWN HISTORY Marvel has published a lot of history books about itself. Herewith, 6 of them—:

The Secret History of Marvel Comics By Blake Bell and Michael J. Vassallo 304 7.5x10-inch pages, b/w with color; 2013 Fantagraphics hardcover, $39.99 THE “SECRET” in this book’s title is that Marvel publisher Martin Goodman got started in about 1932 by publishing pulp magazines (often sleazy, the “shudder pulp” and “light bondage” genres) such as Snafu, Gayety, Male, Joker, Stag, Man’s World, Screen Stars, Movie World, Focus, Amazing Detective, Best Western, Mystery Tales and the like. Comics didn’t come along until later although such titles as Joker featured cartoons as well as pin-ups and text jokes. (Oddly, Goodman’s jokey Humorama line is barely mentioned herein.) Marvel Comics No.1 came along in August 1939, marking Goodman’s entrance into the competitive comicbook publishing industry. Goodman cared not a whit for quality. “Goodman’s strength lay in circulation and distribution. For him, success meant jumping and pumping—jumping on a successful trend and pumping multiple similar titles through the pipeline as fast as possible in order to rake in as much profit as possible” before the trend fizzled out. Apart from divulging the “secret,” this book is full of illustrations—magazine covers but also short story illustrations by such comics luminaries as Jack Kirby, Joe Simon, Matt Baker, Syd Shores, Carl Burgos, Alex Schomburg and others. Samples of their work and short biographies (1-2 pages of them) occupy the last 178 pages of the book. Hereabouts are samples of the art in the book. Of the books reviewed under the Marvel history headline here, this one is the most fun and offers the most hard-to-find information, particularly the visual information culled from the early work of the artists just named.

The Marvel Vault: A Visual History By Roy Thomas and Peter Sanderson; Updated by Matthew K. Manning 208 10x11-inch landscape pages, b/w and color; 2016 Titan Books hardcover, $39.95 THE TEXT is pretty much straight-forward history, arranged chronologically, decade by decade—“sharing the insider’s story of Marvel Comics No.1 in 1939 to the bold new arena of the present day,” as the back cover blurb tells us. But the subhead on the cover—“visual history”—captures the essence of the book. Pictures. Lots of them. And the generous page size permits ample display of all imagery. The volume is “chock-full of historic images (early sketches of Sub-Mariner and the Human Torch, Bullpen birthday cards,” photographs of artists, stand-alone character portraits excerpted from the stories, and covers, dozens of covers, including the historic ones—Captain American hitting Hitler, Fantastic Four No.1, and pencil sketches for others). And the inside front cover is a huge envelope with a facsimile sketch of the early Sub-Mariner, a typewritten synopsis of the first Fantastic Four story, some trading cards, and the Marvel Convention program from 1975—treasures, all.

Marvel Greatest Comics: 100 Comics That Built a Universe By Melanie Scott and Stephen “Win” Wiacek 256 9x11-inch pages, b/w and color; 2020 DK Penguin Random House hardcover, $35 EACH OF 100 MARVEL COMICS is allotted just two pages that display the cover of that issue (with the names of the cover artist plus writer, penciler, inker, letterer, editor, editor-in-chief) and one large panel illustrative of the story plus a verbal description of that issue’s story that also tells us why it is so special as to rate an entry in the list of 100. These “commentaries” are produced by 15 writers and editors (among them, Peter David, Mark Waid, Chip Zdarskky, Tom Brevoort). The fabled hundred include Amazing Spider-Man No.33 (in which Spidey holds over his head a massive tonnage of steel, finally flipping it over his shoulder), Fanatastic Four No.48 (which introduces the Silver Surfer), Nick Fury, Agent of SHIELD No.1 and Captain America No.111 (both drawn by Jim Steranko, “a revolutionary writer-artist,” saith Mark Waid, “who opened Marvel up to psychedelia and op-art influences, combining comics and film media to create storytelling techniques still imitated but never surpassed”). Also Luke Cage, Hero for Hire No.1, the character’s debut title; Amazing Spider-Man No.121, in which Spidey, instead of saving his girlfriend Gwen Stacy accidentally kills her; and Iron Man No.128 wherein Tony Stark faces his alcoholism—and 93 more.

Marvel: The First 80 Years The True Story of a Pop-Culture Phenomenon By Fabio Licari, Marco Rizzo and, additional text and editing, Steve Behling 160 8x11-inch pages, b/w and color; 2020 Titan Magazines hardcover, $29.99 A SOMEWHAT SHORTER and less spacious version of The Marvel Vault, this book poses the question: why just another version of The Vault? It’s four years later, but The First 80 Years covers the same history. So how different? Not much. It’s the same history but not the same book. The history text has been rewritten with different emphases, and the illustrations are sometimes the same but mostly different—and they’re given less display space because the page size is smaller. Otherwise, this volume is as much a “visual history” as The Vault. The editors/writers (unnamed? why?) have added an intermittent timeline across the bottom of pages, noting various events both real and fictional (Stan Lee hired 1939, the debut of the Rawhide Kid in the Spring of 1955, the first issue of The Marvel Age in March 1983). Otherwise, the chief difference is the spectacular silhouette cover, front (seen near here) and back (also with silhouettes).

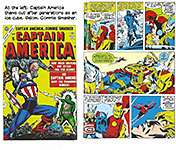

Captain America: The First 80 Years By Fabio Licari, Marco Rizzo and, additional text and editing, Steve Behling 192 7.5x11-inch pages, b/w and color; 2021 Titan Magazines hardcover, $29.99 THIS BOOK is

obviously a companion volume whose relation to Marvel: The First 80 Years is both in the decadent subtitle and in the cover design, another stunning

deployment of silhouette. If ever a comicbook character needed an entire book

devoted to him, it’s Captain America. The hapless Cap has died and come back to

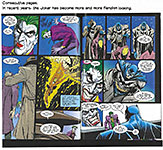

life so many times that we sorely need a road map. This book is the map. Steve Rogers retires Cap and takes up teaching in Lee High School in Connecticut. As revealed by writer Steve Englehart in Captain America Nos. 153-156, another duo—William Burnside and Jack Monroe— take over Cap and Bucky; this, I think, is the Commie Smasher Cap. They do Cap and Bucky through the 1950s. But they go mildly crazy amid the McCarthy era’s passion for catching Commies, and the government saves their sanity by putting them into suspended animation (to reawaken in the 1970s). Meanwhile, the real Cap is discovered in a block of ice in the North Sea, where he plunged after World War II; he is revived and assumes his trouble-shooter role in life. No, wait: what happened to Steve Rogers, the high school teacher? Well, he’s there somewhere. That’s why we need this book—to reconcile all these guises, retirements and revivals. Cap partners with the Falcon, becomes Nomad, fights the Red Skull over and over again. He even joins Hydra. All of which is explained in this handsome volume. Throughout the book are scattered brief bios of writers and artists— Gene Colan, Sal Buscema, Jim Steranko, John Romita, Steve Englehart, Mark Gruenwald. And the timeline device is deployed to trace historic moments. At the end of the book, as Cap approaches his 80th anniversary, he is written by Ta-Nehisi Coates, an African American who has lately become spokesman for his demographic. For Coates the super patriot is a peculiar challenge, saith Coates: “He is ‘a man out of time,’ a walking emblem of greatest-generation propaganda brought to life in this splintered postmodern time. Thus, Captain America is not so much tied to America as it is but to an America of the imagined past. ... “‘I am loyal to nothing except The Dream,’ [he says]. “Writing, for me, is about questions,” Coates continues, “—not answers. And Captain America, the embodiment of a kind of Lincolnesque optimism, poses a direct question for me: Why would anyone believes in The Dream? What is exciting here ... is the possibility of exploration, of avoiding the repetition of a voice I’ve tired of.” To write Captain America, Coates must assume the voice of The Dream, and yet, how can Coates, an African American, believe in The Dream that promises so much but delivers so little for Blacks?