|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 413 (news thru January 29, 2021). Herein, we admire the work of Dan DeCarlo (particularly cute sexy babes) and T.S. Sullivant (particularly anthropomorphic animals) in new books about them, and we take a long loving look at Bud Blake’s Tiger. We review the Kent State graphic novel and six first issue comicbooks and speculate about DC’s Future State with superheroes’ inner lives; plus news and editoons from the last month and lists of comic strips ending in 2020, comic strips starting, and cartoonists dying. And a list of R.C. Harvey’s 17 books and all of his Trumpet cartoons. And more. So much more that we’re providing a reader’s guide. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order (the longest entries are marked with an asterisk* a reader’s guide to help you decide where to spend your time)—:

NOUS R US Syndicate Pulls Pearls Under the Mask, the Next Batman Will Be Black FCBD Is Back New Yorker On Strike Jack Kirby’s Son Upset by Rioters’ Captain America R.I.P. Julie Strain Satire in Pogo on Display A Riot That Revealed U.S. Hypocrisy Fulcrum Gives Up on Graphic Novels Paper Swears Off Editoons Award Winners Odds & Addenda Roosevelt Hotel Closed COUNTERPOINT Editooning Right and Left

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews Of—: Wolverine Black, White & Blood, No.1 Barbalien, No.1 Punchline, No.1 DC Future State Marvel Voices Indigenous Voices, No.1 Wonder Woman, No.1 Kara Zor-el Superwoman, No.1

Stan and Dan and My Friend Irma

TRUMPERIES The Antics and Idiocies of Our Bloviating Buffoon in Chief The Trumpet on the Covers Jim Carrey’s Farewell Portrait of “the Worst First Lady”

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy **Selected Editoons from the Past Month

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Focus on Tiger by Bud Blake

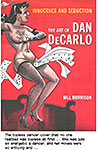

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Review Of—: *Innocence and Seduction: The Art of Dan DeCarlo

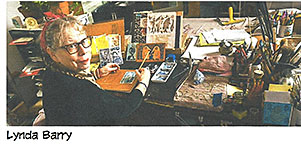

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews Of—: Making Comics by Lynda Barry This Is the End: The Trump Years by Patrick Chappatte

BOOK REVIEWS Long Reviews Of—: **A Cockeyed Menagerie: The Drawings of T.S. Sullivant *Stan Lee: A Life in Comics

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Reviews Of Graphic Novels *Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY The Thing of It Is ... What Did the Trumpet Actually Accomplish? A Personal Note

17 BOOKS BY R.C. HARVEY

Passin’ Through Larry King Comic Strip Departures This Year (2020) Cartoonists Who Died This Year New Comic Strips This Year

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em.

But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics. AND—

“If we can imagine a better world, then we can make a better world.”

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

SYNDICATE PULLS PEARLS In his Pearls Before Swine comic strip, Stephan Pastis regularly tells jokes that are likely to offend some of his readers. That’s his schtick—seeing whether he can get away with it, this time. But when his distributing syndicate, Andrews McMeel, pulled a week’s worth of the strips scheduled to run in 850 subscribing newspapers in January, that was a surprise. Five of the week’s strips depicted a military coup, and the syndicate felt too many of the Pearls readers would think that sequence was intended to comment on the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. But it wasn’t. Like all newspaper comic strips, the Pearls strips are drawn weeks before publication dates in order to gives syndicates time for processing and distribution. These (possibly) offending strips were produced long before the outrageous events of January 6. “The syndicate almost never stops any strips I run, so this is really unusual,” Pastis said in an email interview. “But these are unusual times.” The strips were scheduled to start January 18, reported Dan Taylor at pressdemocrat.com, and run during the week of the U.S. presidential inauguration. On Friday, January 8, two days after the mob riot at the Capitol, the syndicate sent a notice to subscriber newspapers that strips for the week of January 18 would be replaced with substitutes already created by Pastis. The strips haven’t been killed but merely delayed, said Andy Sareyan, the syndicate’s chief executive officer. “We’ll run the strips when things calm down,” Sareyan said. “To run them now just seemed like bad timing. They were about to come out at the time when tensions are running so high in the country.” Pulling the strips for now seems sensible, given our culture's easily offended segments. That they ought not to be offended is another question. Seems that the syndicate, instead of pulling the strips, could have provided a text footnote for all subscribing papers to print along with the strips. Educating the American public is always a noble enterprise— albeit futile.

UNDER THE MASK, THE NEXT BATMAN WILL BE BLACK For months, DC Comics has spread the word that a new Batman will premiere in January. “They also teased that underneath the costume of the new caped crusader would likely be a person of color,” reported George Gene Gustines at nytimes.com. “The identity of the new hero was revealed when DC released a cover of the second issue of the new comic: he is Timothy Fox, one of the sons of Lucius Fox, a business associate of Bruce Wayne, the original Batman.” Timothy Fox will debut as the title hero in “Future State: The Next Batman,” a four-issue series written by John Ridley, the screenwriter of “12 Years a Slave,” with art by Nick Derington, Laura Braga and others. Said Gustines: “The four-issue series will arrive in comic stores in January and February and is part of a two-month event that puts DC’s regular series on hold and replaces them with new ones that look to the future of the DC Universe. “The leap forward has fresh faces taking on the roles of familiar heroes: in addition to Timothy Fox as Batman, Jonathan Kent, the son of the Man of Steel, is Superman, and Yara Flor, who is from Brazil, is Wonder Woman. Some of these future characters are already having ripple effects. The new Wonder Woman, who was created by the writer and artist Joëlle Jones, will be getting a Wonder Girl series set in the present following the event. The character is also being developed as a series for the CW.” In a recent interview, Ridley talked about the target audience for his Batman story: his sons. “They appreciate the things that I do,” he said. “They’re happy for me. They’re great supporters. But they would much rather see ‘Black Panther’ than ‘12 Years a Slave,’ let’s be honest. So to be able to write the next Batman, for them to know that this next Batman is going to be Black, everybody else on the planet can hate it, have a problem with it, denigrate it, but I have my audience and they already love it.”

FCBD IS BACK Free Comic Book Day returns to everyone’s calendar as a single date this year—Saturday, August 14, 2021. FCBD began in 2002 as a marketing stunt designed to draw customers into comicbook shops. It was the result of retailer Joe Field of Flying Colors Comics in Concord, California, brainstorming the idea in the August 2001 issue of Comics & Games Retailer magazine. The day has a three-fold purpose: to thank current comic book readers for their support, to introduce new readers to the joys of comic book reading, and to call back those who may have loved comic books in the past but have been away from them for awhile. Coordinated by the industry's single large distributor, Diamond Comic Distributors, the event has spread to countries in Asia, Europe, and Australia. For the first years, retailers bought regular titles that they then gave away, usually limiting customers to 3-5 comics each. After a year or so, though, comicbook publishers began producing special comics for FCBD—often abbreviated versions of regular titles, sometimes “introductory” issues intended to promote a future title. Again, comicbook shops bought these special editions expressly to give them away. Presumably, the price of these “preview” issues for retailers was much lower than the usual cover price in order to make the exercise financially viable for retailers. For the first several years, FCBD managed to take place on the spring weekend that the year’s first block-buster superhero flick debuted. Gradually, that connection deteriorated to the first Saturday in May. And that’s when it was supposed to occur last year, but the pandemic cancelled the May date. Later, as the terror of Covid-19 subsided somewhat into ordinary fear, FCBD 2020 was reconstituted to spread over several Wednesdays during the final months of the summer. While this maneuver was well-received by fans and retailers around the world, reported Marty Grosser in the Previews catalog, the “big event” feeling was lost. So this year, Diamond and the rest of the retailing industry have revived the one-day tradition. Said Grosser: “We’re all hoping that by August, things will be getting back to normal, and safe for large gatherings of people”—including larger than normal crowds at comicbook shops on FCBD. Here’s hoping.

NEW YORKER ON STRIKE Roughly 100 staffers of The New Yorker magazine walked off their jobs on Thursday, January 21, to protest inequities in pay. Starting at 6 a.m., the walkout included copywriters, web production staff and other union employees; it lasted 24 hours until 6 a.m. Friday. Bylined staff writers were not involved because they are not members of the union. The strike comes after two years of negotiations failed to arrive at salaries both sides deemed fair. The

protest will doubtless interrupt production of the prestigious title (including

its digital platform) helmed by longtime editor-in-chief David Remnick. The

immediate causes of the walkout are the publication of a survey revealing

inequities in the magazine’s pay scales and sharply conflicting salary

proposals. The NewsGuild union released a survey on Wednesday that suggested a wide pay disparity among non-writer editorial staffers at the magazine, particularly women of color. On average, the union claimed, the magazine pays its female staffers $7,000 a year less than their male counterparts. After two years of negotiations, the union said, it proposed a base salary of $65,000 a year with gradual pay hikes so that all editorial workers could survive in New York City, where the magazine is based. The magazine management’s counter-offer was “an offensive and unacceptable response to the Guild’s wage proposal.” The company offered a $45,000 base salary, which the union said is only $3,000 more than the lowest current full-time salaries. Negotiations continue.

JACK KIRBY’S SON UPSET BY RIOTERS’ CAPTAIN AMERICA Mike Lynch, at his Facebook page, reports on January 15 that Jake Tapper (one-time cartoonist; now a CNN commentator) said the following on his Twitter account: "Neal Kirby, the son of Captain America co-creator Jack Kirby, was distressed to see some of the January 6 terrorists/rioters wearing shirts with versions of his dad’s creation corrupted by the image of the outgoing president.” He then provides the following link to Neal’s remarks: https://www.facebook.com/Mike.Lynch.Cartoons/posts/10158065178179397

R.I.P. JULIE STRAIN Heavy Metal model and B-movie actress Julie Strain, a frequent presence at the magazine’s San Diego Comic-Con booth and at other comic conventions, passed away on January 10 after a long battle with dementia, the company announced. She was 58. Strain began appearing in B movies and modeling in the early 1990s, said Milton Griepp at ICv2.com. Her first claim to fame she earned by taking her clothes off: she was Penthouse Pet of the Month in June 1991 (when she was 29) and Pet of the Year in 1993. She appeared in over 100 movies, enough to earn her the title “Queen of the B-movies.” She modeled for numerous artists whose work appeared in Heavy Metal, including Olivia de Berardinis, Simon Bisley, Louis Royo and others.

Strain was married to Heavy Metal publisher Kevin Eastman from 1995 to 2006. I’ve often wondered how that romance got started, Eastman being sort of your average comicbook nebbish and Strain being a statuesque model, 6 feet 1 inch tall (“and worth the climb” as one of the magazines published by Eastman proclaimed). Eastman is co-creator with Peter Laird of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, an amateur comicbook series that began in 1984. The two creators launched a canny promotion campaign, distributing press kits all across the country. That prompted more issues of the comicbook, plus a tv series in 1987, five live-action films (starting in 1990), and merchandising galore. Eastman started his own publishing firm, Tundra, in 1990, and although it produced many notable products, the enterprise did not take off like the Ninja Turtles did. It never turned a profit, saith St. Wikipedia, and required regular funding from Eastman’s bank account. Then in 1992, Eastman heard Heavy Metal magazine was looking for a buyer, so he bought it. Publisher of a major sf and fantasy magazine. Now that could attract the attention of a 6-foot model. And it apparently did. Here’s how Strain describes their meeting and subsequent marriage: “I

met my husband, co-creator of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, at the Golden

Apple Comic Book Store in Hollywood. He stood in line to meet me and joined my

fan club. He bought a Polaroid picture with me and a photograph that he still

keeps on his desk; the inscription reads, ‘Kevin you make me smile. Julie

Strain.’ I’ve been smiling ever since. “Being married to him is the greatest joy. He is my soul mate. We wed on Martha’s Vineyard, barefoot on a beach at sunset.” These remarks are quoted from a book of her photographs published by her husband’s company: Julie Strain’s Greatest Hits, published in 2001, midway through their marriage. On the title page, the last word is overprinted by another, “Tits.” From that you can tell she has a sense of humor, which is also revealed in many of her facial expressions in otherwise seductive poses. That may explain a lot. At one time, the Eastmans had homes in Los Angeles, Massachusetts, and Arizona and worked on “a million projects” together. They have a son, Shane, born in 2006, the same year they divorced. Strain’s dementia was believed to be connected to a horseback riding injury she suffered in her 20s. She had been in hospice care since at least 2018.

SATIRE IN POGO ON DISPLAY The political and social satire in Walt Kelly’s comic strip Pogo will be showcased from January 30 through October 31, 2021 in an exhibition curated at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio. Admission is free. A press release from the Ireland describes the exhibit: “Kelly tackled many of the political issues of the world in which he lived, from the Red Scare to civil rights, the environment, scientific exploration and consumerism. We celebrate Walt Kelly and his social commentary through the joyous, poignant and occasionally profound insights and beauty of the alternative universe that is Pogo. Working in the mid-twentieth century, Kelly drew on the legacy of earlier generations of newspaper cartoonists and then became a major influence on his successors.” The Museum will be temporarily closed April 19 - June 11. The Ireland Library & Museum houses the world’s largest collection of materials related to cartoons and comics, including original art, books, magazines, journals, comic books, archival materials and newspaper comic strip pages and clippings. BICLM is located in Sullivant Hall at The Ohio State University, 1813 N. High Street, Columbus, OH 43210. Explore the collection online at cartoons.osu.edu.

How they see us: A RIOT THAT REVEALED U.S. HYPOCRISY "The city on the hill has lost its shine," said Konstantin Kosachev at Rossiyskaya Gazeta (Russia). The political system that is supposedly the envy of the world was stripped of "its sacredness" on January 6 when a mob of Trump supporters assaulted the U.S. Capitol, killing a police officer and endangering lawmakers as they certified Joe Biden's election win. American politicians and pundits decried the violent protest as a horror, even though they routinely praise such displays in other countries as valid outpourings of anger against undemocratic regimes. U.S. democracy is forever tainted, said Yevgeny Shestakov, also at the Gazeta. The November election that ostensibly went for Biden was "opaque," because numerous states changed voting rules on a whim. No wonder President Donald Trump's supporters feel cheated. From now on, any party that loses an election will be able to plausibly claim that the "results were rigged." The U.S. has lost its right to criticize other countries that quash riots, said Ai Jun at the Global Times (China). Remember when Hong Kong protesters broke into the city's legislative building in 2019? At the time, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called the scene "a beautiful sight," while Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said the U.S. stood with the activists and supported their "freedom of expression." Yet when the very same thing occurs in the U.S., they "define it as lawlessness" and call it "unacceptable." Unlike their American counterparts, Hong Kong police never fatally shot a protester. What's particularly shocking, said Jafar Blori at Kayhan (Iran), is that the U.S. is now muzzling both the protesters and the president. Facebook and Twitter, under pressure from Congress, erased Trump from their sites and purged many of his followers. " Yes, you heard right, the biggest pretender to democracy and freedom of expression in the world, the one that censures others for supposedly attacking the free press, "overnight became the biggest censor in the world!" Democracy is "America's most important brand," said Oray Egin at Haberturk (Turkey), and Trump has damaged it, perhaps fatally. ... America is now an object of pity and disdain, and nobody is more delighted than Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has long insisted that the U.S. political system is just as flawed and corrupt as Russia's.

FULCRUM GIVES UP ON GRAPHIC NOVELS Colorado book publisher Fulcrum Publishing will sell its line of graphic novels as well as its gardening, natural history, and travel books—126 titles in all— to rival publisher, Chicago Review Press, a publishing subsidiary of the distributor IPG. The transaction, reports Calvin Reid at publishersweekly.com, includes several yet-to-be-published books. Fulcrum has decided to specialize in books on the American West, the environment, conservation, Native American culture, education, self-help, American history, and civics. Fulcrum told Publisher's Weekly that, after expanding into categories such as the graphic novel and gardening, it wanted to refocus on its original mission. Fulcrum Publishing had added nonfiction graphic novels to its line in the last ten years, focused on history, with a strong emphasis on diversity, and had been publishing at least three nonfiction graphic novels a year, marketed to general readers and to comic shops, libraries, and schools. Graphic novels included Matt Dembecki's Trickster; District Comics: An Unconventional History of Washington, DC; Wild Ocean: Sharks, Whales, Rays, and Other Endangered Sea Creatures, Jason Rodriguez's three-volume anthology Colonial Comics, Joel Christian Gill's multiple-volume Strange Fruit, Robert Smalls, Bessie Stringfield and Tales of the Talented Tenth, as well as Captain Of Friendly Cove.

PAPER SWEARS OFF EDITOONS Alexandria Times of Alexandria, Virginia started the new year on January 7 by announcing that it will drop editorial cartoons from their historic place on the editorial page. The Times has no staff editoonist but subscribes to a syndicate service for editoons, which are, of necessity, on national topics only. Alexandria, with a population of 120,000, is within the metropolitan vicinity of Washington, D.C., but despite its proximity to national government—or perhaps because of it— the Times is both hyper-local and stridently non-partisan, and consequentially the presence of a national-focused cartoon on its editorial page has always been an anomaly. And the Times recognized the strangeness in an editorial announcing the demise of its editorial cartoon: “We have heard from many of you through the years questioning our decision to run cartoons that focus on national issues. Our perhaps old-fashioned belief that an editorial cartoon completes opinion pages is what led us to keep running a nationally syndicated cartoon. The national nastiness of last year was part of the impetus to drop the cartoon now.” Another harbinger of the future for political cartoonists.

AWARD WINNERS This year’s Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning went to illustrator Barry Blitt for his New Yorker covers. Blitt claims he will not miss Donald Trump as a target. “I will not miss him, certainly not as a cartoonist. I’ve drawn him too many times, and spent too much time wringing obvious jokes out of him. I actually found him sort of amusing before he became president, but he ruined our relationship forever by getting into politics. “Every president is a big, fat target,” Blitt went on. “I don’t think Biden has been ripped into enough, owing to the comparative awfulness of his opponent.” Three finalists for the Pulitzer are Lalo Alcaraz, Matt Bors, and Kevin “Kal” Kalaugher. The Overseas Press Club picked Adam Zyglis for its award on international political cartoons. The award was once called the Thomas Nast Award, but then OPC learned that Nast was against Catholics and had committed other sins of that sort, so, in a fever of self-righteous purging of history, they took his name off the award. The Sigma Delta Chi award this year went to Clay Bennett. The Herblock Prize went to Michael de Adder, finalist Matt Lubchansky. J.D. Crowe won the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for editorial cartoons, and Pat Bagley was named editorial cartoonist of the year by the National Cartoonists Society.

ODDS & ADDENDA The historic Roosevelt Hotel in New York City closed permanently in December after nearly 100 years of operations. Owned by Pakistan International Airlines, the hotel cited the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing drop in business as the principal reasons it will cease operations. Located at 45 East 45th Street (between Madison Avenue and Vanderbilt Avenue) in Midtown Manhattan, the hotel was named in honor of President Theodore Roosevelt. It opened on September 22, 1924; it closed on December 18, 2020. I didn’t spend a lot of time in the Roosevelt, but I spent enough time in the bar there to necessitate a visit to the men’s restroom, which, I immediately discovered, had the most distinctive urinals I’d ever peed into. The urinals were almost as tall as a man—you had the sensation of walking into a small room—and they were stunning black marble.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, who covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these three other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com (now operated without Gardner by AndrewsMcMeel, D.D. Degg, editor); and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO A man is a success if he gets up in the morning and gets to bed at night and in between does what he wants to do.—Bob Dylan To die is poignantly bitter, but the idea of having to die without having lived is unbearbable.—American humorist Josh Billings

COUNTERPOINT He’s Fired Edition Written by Counterpointer Our future former president is loudly urging us to ignore the election results and continue ridiculing him for another four years. Alas, the Satirical College results are final. So now, Counterpoint dutifully prepares for the political obit of a uniquely cartoonish commander-in-chief. We’re no longer buying orange ink by the barrel. We’re rushing to execute cartoons of the lame duck president before he helicopters into the sunset. We’re redeploying critical resources as rapidly as a Fox News weekend anchor hastily recruited to run the Pentagon. Of course, we’ll yank our Warp Speed engines into reverse if Mike Pence declares he and his boss really won the election. But in the meantime, here’s Counterpoint.

For $7/month or $70/year, our email newsletter will land in your inbox five days a week, and will always feature an equal balance of left- and right-leaning ‘toons. Get 14 day free trial. And now, here’s the daily offering that came in over my transom on January 29—:

CLIPS & QUERIES Why is the truth called naked and not nude? Do fish get thirsty? I drink to make other people interesting. Do illiterate people get the full effect of alphabet soup? Why do people with closed minds always open their mouths?

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

IN YET ANOTHER introduction of the Wolverine character, Wolverine Black, White & Blood, No.1, we have a book whose title was doubtless determined by management’s desire to produce a comicbook in black-and-white, enlivened on every page by liberal splashes of red. Rather than a single continuity, we have three stories: “The Beast Within Them” (by writer Gerry Duggan drawn by Adam Kubert), “I Shall Be a Wolf” (by Matthew Rosenbserg and Joshua Cassara), and “Cabin Fever” (by Declain Shalvey, words and pictures). In the first tale, we see Wolverine as an experimental fighting machine, who is being tested in action; he sheds a lot of his opponents’ blood. In the second story, Wolverine is the bound and tied captive of the Grand Inquisitor of Hydra who is trying to get him to tell something; Wolverine does not comply but somehow tricks the Grand Inq into triggering a bomb that explodes and kills everyone, Inq and Wolvie among them.

Since Wolverine is a well-known character, we don’t need much to introduce him. In effect, each of the three tales is an episode, each revealing a different aspect of Wolverine’s blood-thirsty personality. No, not blood-thirsty: blood shedding. The artwork is spectacular, but I’m not sure we’re better off knowing that Wolverine delights in slicing and dicing people. I haven’t been keeping up with the X-men adventures lately, so I’m a little alarmed by Wolverine’s bloody propensity herein. Admittedly, the people he cuts up deserve death. But still—all that blood splattered around?

THE TITLE CHARACTER in Barbalien No.1 is a Martian sent officially to Earth to invade and report back. He apparently failed to do one or the other, and now that he’s back on Mars, he’s in court: they’re trying him for “species betrayal,” namely “wearing human skin and coupling with one of their males.” He’s found guilty and sentenced to death, but he has three months to live. Then we have a flashback to Barbalien’s sojourn on Earth. The skin Barbalien wore was that of a police officer. When he put his hand on his partner’s knee, the partner angrily objected. We don’t find out in this issue who Barbalien slept with, but we do see Barbalien and his partner get involved in calming down a bunch of AIDS protesters. They are protesting the government’s failure, for five years, to do anything about the AIDS epidemic. Then Barbalien saves the life of one of the protest leaders by shedding his human skin and, as a Martian, flying to catch the guy who is falling from a great height. The episode demonstrates Barb’s compassion, which apparently can overrule his desire to remain in disguise: but no one, even the guy he rescues, seemingly notices this breach. Later, Barb, on his time off and in civilian garb, goes down an alley and opens a door and finds himself in a gay bar. Writer Tate Brombal leaves him there, and then the rest of us all go back to Mars—and back in time, too. There, we meet Boa Boaz, a bounty hunter, who vows to capture Barbalien and return him to face justice in Mars. In other words, we’re in a time period different from either of those we’ve so far encountered; but this time shift is not very clearly indicated. Gabriel

Hernandez Walta’s art is wholly adequate. Nothing stylistically

distinguished about it; it does the job. Like many comicbooks these days, the story is told very cinematically: as in a movie, much of the narrative is revealed through pictures. It’s taken a long time for the producers of comicbooks to realize the narrative power of pictures in the medium they’ve chosen. And while this is an entirely commendable development in a visual medium, comics are not movies. One of the chief differences is that comics require more explanation than movies. For example, in movies we identify characters by sight and by sound, by the sound of their voices. And sometimes, sound tells us things that pictures can’t. Pictures can’t be sarcastic, for example. But the tone of the sound of speaking can. So in comics, the absence of sound requires that the creators pay more attention to captioning to help us identify and understand characters. And when the characters are often in deep shadow, obscuring their appearance, verbal ID is essential. And that is a problem in this book. It’s all too dark, visually. Barbalien’s ability to shift from one shape/identity to another is likewise not explained: we assume that’s what he’s doing because the pictures show him doing that. But don’t any of his Earth comrades notice this shape-shifting? Apparently not. We could use some verbal explanation here. Cinematic storytelling is welcome in comicbooks because it rightly shifts our attention to the visual aspect of the medium. But writers need to be aware that movies and comics aren’t the same; and each requires its own special storytelling treatment. Brombal seemingly doesn’t realize this.

AND NEITHER DOES James Tynion IV, who, with Sam Johns, wrote the first issue of Punchline. Tynion invented the character, and this book is her debut. Punchline is another crazed female character who is willingly preyed upon by the Joker: she craves his attention, and to get it, joins him in various of his criminal pursuits. But in this issue, we see little of that sort of action. Herein, Punchline, whose actual name is Alexis Kaye, is on trial: the book begins with her in a courtroom and ends with her in a courtroom. In between, it’s mostly talk—and not by Punchline. Most of the issue concerns Harper, who is sometimes a costumed superheroine named Bluebird, and her friend Cullen. Mid-way through the book, Cullen spends six pages musing about the Joker, all first-person interior monologue with no pictorial excitement at all. One of the pages depicts the screen of his laptop computer with a string of dialogue on it. This is visual excitement gone to the opposite extreme. Punchline finally shows up, a woman with a long black-hair ponytail and clown make-up, who begins another long musing about the Joker. She describes a good punchline—it plays against your expectations, subverts them, twists them. In an episode complete in the book, she witnesses a killing and is outraged that the dying person is not smiling, Joker-like, so she stabs him. The Joker shows up. Offers to help her make the joke better, but she refuses help, saying she can make people see the joke; she can make the entire city laugh, shake people up, make change real. In the last sequence in the book, Punchline is in police custody, in make-up, in costume, being escorted (in handcuffs) to the courtroom where she’s on trial. They walk by a crowd of people, all shouting to free Punchline. She is properly, modestly, appreciative of their attention and good wishes. One of the crowd is an orange-haired guy who we haven’t seen before (Bluff? his Internet tag?); he’s with a gray-haired girl, likewise (Rowrow?). Then we get a glimpse of someone in a half-face mask. Bluebird? End. In reading the book, nothing is as clear as I’ve just described. Punchline is not clearly identified more than by a passing remark a cop makes. Other characters are only casually identified: this is the cinematic manner, which, without benefit of verbal captions, depends for information on what people say, and for the sake of realism, people aren’t depicted as saying “Hello—I’m Alexis Kaye, otherwise known as Punchline.” The story unfolds over many pages, slowly putting characters’ faces with names. We eventually find out that Harper is Bluebird. But who is Cullen? Why does he have such a prominent role in the debut issue of Punchline? The most informative page in the book is the title page with the headline: “After the Joker War, Punchline Stands Alone!” Mirka Andolfo’s pictures are clean, clear-cut and edgy with a manga flavor in the rendering of faces.

Tynion and Andolfo in combination have created another cinematic production. And with it, most of its flaws. Among its flaws, a tendency to write too many words. Most of Cullen’s musings are self-indulgent: they help create his character, his personality, but too many words in a visual medium do not make for an outstanding specimen of the medium. And it would appear that we are headed in that direction.

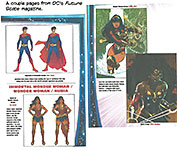

ABOUT EVERY EIGHT MONTHS (although it seems more often than that), first Marvel and then DC Comics—or vice versa— launches a massive re-do of their entire line of comicbooks. Or so they say. “Starting next month,” the blat begins, “everything will be different and brand new all over again.” And it’s starting again, this winter, 2021. At DC, “DC Future State takes you beyond tomorrow.” The big three—Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman—will undergo “new developments ... along with some new heroes” who will be “taking on those familiar roles. ... a new line-up of new yet familiar heroes: Jonathan Kent as Superman, new character Yara Flor as Wonder Woman, Far Sector star Jo Mullein as Green Lantern. ... massive changes.” And so on. DC even published a “free” magazine outlining all the vast, earth-shattering changes that are forthcoming.

The Future State Kal-El “is stripped down, literally and figuratively, to his cape and briefs.” Meanwhile, over at Marvel, it announced that its future plans are to continue doing what it’s always done—introduce new characters that will expand on the publisher’s well-known (??) tendency for diversity, racially and sexually. Instead of a mere tendency, in future we’ll have an emphasis. In a special introductory booklet, John Jennings quotes James Weldon Johnson’s “Negro National Anthem” that opens with “lift every voice” to make sure we know Marvel “has been striving to make room for everyone as well, little by little ... one panel at a time.” The first issue in this promised “new” Marvel Voices series, entitled Indigenous Voices, introduces Native American characters by listing

them all—Wyatt Wingfoot, Red Wolf, Thunderbird, Shaman, Snowbird, American Eagle, Mirage, Talisman, Black Crow, Warpath, Portal, Forge, Puma, Silver Fox, Risque, and Echo. No pictures yet; just names. Apparently, the “new” diversity—or expanded diversity being touted—will involve a vast number of Native American characters (with stereotypical names, Wingfoot, etc.). The stories that follow—just fragments, not complete narratives—deploy Echo, Mirage, and Silver Fox. Not enough to reveal much about any of the characters—or, in fact, what they’re up to. In short, a bad first issue.

BACK AT DC COMICS, in the first Future State issue of Wonder Woman, she’s deep in the Amazon rain forest, where she is fighting a giant dinosaur. After cutting off the head of the beast, she begins to muse about the distant past, and then she’s attacked by an 8-headed monster. As she fights it, she yells “Jerry!” several times, and when Jerry arrives, we see a flying horse; that’s Jerry. Wonder Woman climbs aboard and finishes off the multi-headed critter. Then a smallish girl/woman with lots of red hair shows up. WW calls her Caipora. They evidently know each other. WW says she’s going into the Underworld to rescue her “sister warrior,” but Caipora doesn’t like that idea, and, calling WW Yara Flor, she forbids the proposed action. But she says she’ll take WW into the Underworld, and she does. She engages in conversation with a kind of troll who is guarding the entrance to the Underworld, and as that goes on, WW breaks off part of the gate (which looks like one of those revolving handle gates in the New York subway), and she and Caipora, exchanging witticisms as they walk, enter the Underworld, which looks a lot like an airport with signs pointing to “gate” and “check-in.” Their “ride” shows up; it’s a skiff poled along by a skeletal ferryman, Charon, who silently demands payment, extending a boney hand.

Drawn as well as written by Joelle Jones, the book is very attractive visually, and Wonder Woman—excuse me, Yara Flor—is beautiful. And the storytelling is deft. But where is this going? WW is battling Greek mythology here, not 21st Century bad guys. So it’s a pleasantly exciting tale but nothing that engages us. There’s no reality for us here.

AND THE SAME THING happens in the first issue of another Future State title, Kara Zor-el Superwoman. Kara Zor-El, attractively attired in full skirt and blouse with elbow-length gloves rather than the usual super tights, is musing about her mission. She came to Earth to protect people but discovered someone else was already doing that. (Superman, Kal-El, we assume; nobody tells us.) So she left Earth and went to the colony on the moon, which is where she is now, musing. Then a spacecraft lands, and a young woman—teenager—emerges. A shape shifter, she engages with Kara, introducing herself as Lynari, a runaway from Lili’alo of the Starswamp asteroid. They go to Kara’s home/apartment and Lynari tells Kara more of her background: she carries in her head the Starfall Jewel, and if someone takes it from her, she’ll die. She’s trying to find herself, and Kara thinks she can help. Lynari is puzzled by Kara’s having given up her “birthright” to protect inhabitants of Earth. Kara explains that she’s given up violence and that’s what prompted her to come to the moon colony to help. Lynari hopes to evade “our ancestral enemies” who are coming to take the Jewel from her. Lynari is frustrated. She wants to feel at peace. Kara assures her that she, Lynari, is strong enough to control her own life. Then, miraculously, Lynari exclaims “I did it!” Whatever “it” is. Realizing her own strength? She soon concludes that she doesn’t belong with Kara on the moon, and she leaps into outer space. Kara then has a few moments of self-reflection, wondering what has become of “all the anger.” That’s about it. On the last page, Kara rages against the sky, sending power bolts from her eyes into space. As with the Wonder Woman book, this issue offers little in the way of peace-fostering action or life-saving action. Such matters sort of hover over it all, but mostly, what we have here is two introspective women talking about their lives and ambitions. What writer Marguerite Bennett has constructed is a story with no plot. A “story” can be described this way: something happens and then something else happens and then yet another something happens. In a plot, causation functions. What happens is caused by something—and, in turn, it causes something. About a plot, we can ask the question: why? About a story, no such question is possible. What we have in Bennett is talk. Interior lives. No explanation as to “why.”

Is that the shape of future superheroing in DC books? And then there’s Kara’s relationship with Krypto the super dog. The less said about that, the better (i.e., we aren’t told anything about this relationship.) The artwork in this issue goes hand-in-hand with the absence of any noticeable activity. Marguerite Sauvage’s color palette is the most remarkable part of the book. Colors are subdued, pastel shades of reds and blues mostly, accented with white highlights. The effect is very nice—dreamlike. And for a book whose “action” is mostly in the heads of its characters—their interiors—pastels are a perfect fit.

WHAT’S GOING ON HERE? I can only speculate, of course, but it seems the production of DC comicbooks has been taken over by writers, whose creative realm is different than artists’. Artists work in shapes and colors, lines and textures; writers work with words. Their make-believe realities are made verbally—either by what captions say or by what word balloons say. What we’ve seen in these two “future state” books is a world—or several worlds—made of speech balloon verbiage. And not much more. We see superheroes in various modes of self-reflection, struggling with their interior selves, not with external forces, looming monsters or threatening villains. These efforts seem a little more elaborate than the usual every-six-months reboot we’ve been subjected to all these years. And maybe they will be. But I’m not convinced. I’ve seen it all before, and it went nowhere else then. Just puffery, not substance. Why DC and Marvel feel compelled to perform this exercise every six months or so can be easily explained: they believe (a) that they must re-introduce their stable of characters to new readers by dragging out all the old origin tales and modifying them or (b) that only by varying the superhero formula from time to time can they hold the attention of faithful fans. Or maybe it’s just that the writers and artists get bored with their creations after a few months. Or maybe it’s just a publicity gimmick designed to boost sales. In any event, this maneuver smells like the trick it is. Superman will always wear blue tights and Batman an ear-y cowl. And if those things aren’t changing, then it’s all, as I say, a trick. Either it’s a trick, or DC has been taken over by writers, whose realities are verbal, not visual. And that translates to superheroes who don’t use their powers, which tend to be physical not mental, but who ponder and reflect and talk about “life.” And their place in it. If the new Future State DC will be anything like this analysis suggests, we’re in for an entirely different ride. And it will take place mostly in characters’ heads, not outside in the world where danger lurks, demanding superheroic action. If that transpires, then for once—for the first time ever—all the hype about “a new DC Comics” will be accurate. And over at Marvel? Nothing new at all. Just more of the same except this time with Native American heroes.

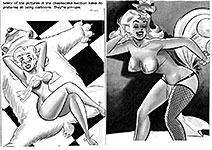

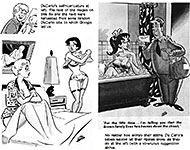

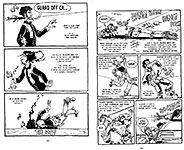

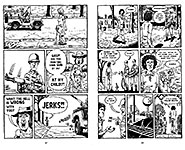

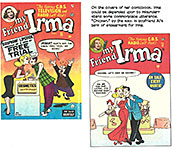

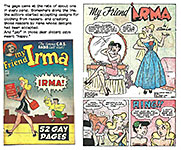

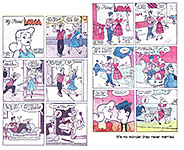

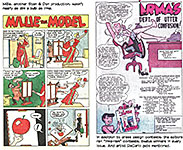

Stan and Dan and My Friend Irma A BIT FURTHER DOWN THE SCROLL, you’ll encounter a review of a good book about Dan DeCarlo and his cartooning of wholesome albeit sexy women. Whilst summoning up illustrations for that article, I dipped into my store of old comicbooks and found a dozen or so copies of My Friend Irma comics, and we’ll end this Funnybook Fan Fare segment with a glimpse into those vintage treasures. DeCarlo drew most (if not all) of these, and Stan Lee wrote the gags. Irma, played on radio and tv by actress Marie Wilson, was the original shapely dumb blonde, and Lee prolonged that character into comicbooks published by Atlas, one of the early corporate names of Marvel Comics. DeCarlo’s rendering of Irma became his stylized way of drawing a “pretty girl”; all his pretty girls (sexy young women) would be drawn in about the same way. I learned how to draw sexy cartoon women by copying DeCarlo (that is, I apprenticed myself to him for this purpose). Until I discovered Wallace Wood’s manner of drawing sexy cartoon women in Mad Comics (chiefly, the Dragon Lady in the spoof of Terry and the Pirates). My Friend Irma was always bylined “Stan Lee.” DeCarlo received no credit initially; throughout Stan Lee’s career, he had a proclivity for crediting writers (namely himself) for creating comics but not artists. Eventually, DeCarlo got a byline—“Stan and Dan” at first, and then, later, “Dan DeCarlo” as a credit separate from Stan Lee’s signature. Lee perpetuated the crediting of artists in the same sort of off-hand, barely consequential manner well into the emergence of Marvel Comics as exemplar of superhero stories. Yes, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko and the rest were credited, but at the top of the opening splash page of every Marvel comicbook, it said “Stan Lee Presents ....” Lee became famous for creating superheroes “with personalities”—character flaws and/or personality quirks. Before Stan Lee, superheroes were simply as super in personality as they were in deed. I see his flawed superheroes as an extension of his writing for humor comics— particularly My Friend Irma. As you’ll see, the gags come thick and fast, at the rate of one per panel, but not particularly insightful. Irma’s stupidity was simply her tendency to take every utterance she heard literally. That was the joke, over and over and over again. It was upon this device that Stan Lee honed his writing skills. And in Irma and Millie the Model and Sherry the Showgirl and the rest of this ilk, Lee’s corny sense of humor flourished. And it was—and is—corny, colossally corny. As I’ve said before, I believe that in developing his first Fantastic Four with personality quirks, Stan Lee set out to write a parody of superhero comics. Personality quirks became the superhero comics version of Irma’s corny tendency to take things literally and thereby to misunderstand everything. And to demonstrate the latter—as well as to show off DeCarlo’s surpassing skill in rendering the damsels —we have assembled the pages that ensue, herewith—:

QUOTES & MOTS “I think the value of the superhero is, and probably always has been, that of a thought experiment. A chance for people, at a very young age, to start asking themselves what it would take to set the world right and what that would entail. If they had the power, how would they use it? At least, that’s a lot more interesting to me than professional wrestling with characters who can fly.”—Mark Russell, writer of Billionaire Island and the second coming of Second Coming

TRUMPERIES The Antics and Idiocies of Our Bloviating Buffoon in Chief AS IS OUR

CUSTOM, we introduce this section with some magazine covers starring the

Trumpet. The first, however, is a mock Time magazine cover, not the real

one. Who did this and where, I dunno. But as a make-believe Time cover,

it is a perfect way to sum up the delusional presidency of the Trumpet in its

final moment as Trump leaves the World Stage.“Time [logotype] ... to

go,” it says, the typography surrounded by funereal black; and then at the

lower right, a tiny Trumpet walking through the exit. Nicely atmospheric, sad,

and, still, a little jab. And

then here’s The New Yorker’s favorite editoonist, Pulitzer-winning Barry

Blitt, he of the frail line and faintly realistic portraiture, showing

Trump being carried off by an [American] eagle. A portrait entitled, “A Weight

Lifted.” Indeed. While awaiting a companion cover to complete a pair, I ran across the cover of the next issue of Time, which I’ve posted next to The New Yorker cover. Here we see the newly anointed Commander-in-Chief standing in a trashed Oval Office, the litter alluding to the mess left behind by the previous administration, which must now be cleaned up. This was not a photograph but an illustration by longtime Time artist Tim O’Brien. A couple days later, my Trumperies cover project began to go seriously awry. I

received my copy of Time through the mails and was stunned to see that

the cover was not O’Brien’s painting of Joe Biden amid an Oval Office mess. No.

Instead, the cover was a photograph of Biden just as he was being sworn in as

Prez. Featured was a quote from his address: “Without unity, there is no

peace.” So where was the other cover? And where did it come from? Was it another faux Time cover like the funereal departure scene in black? I was not the only one confused. Over at Fox News, as reported by an unnamed over-the-Internet-transom journalist, “late Friday morning, at the end of an unusually busy news week, anchor Harris Faulker evidently ran out of things to be outraged about and turned her attention to Time magazine’s first cover of the Joe Biden era. “In Faulkner’s words, the cover ... shows Joe Biden in the Oval Office trashed by his predecessor as he looks out at the nation on fire.” Faulkner went on to posit that if the cover depicted a Republican president in a similar way, “mainstream media would be on fire about it, but with Joe Biden, it’s okay to do this?” Faulkner grew increasingly agitated, staring at the illustrated cover and shouting, “That’s not real! That picture isn’t real! I thought we were a nation who cared about the facts.” Over the course of Trump’s presidency, O’Brien’s artwork depicted Trump looking into a mirror and seeing a king, as well as one in which a wave appeared to be about to wash him away as he sat at the Resolute Desk. In neither of those cases was anyone confused. Everyone apparently realized the pictures were fictions created for satirical purposes. But Faulkner didn’t get it this time. Even when Faulkner’s on-air guest started to seem a bit perplexed about why they were spending so much time on an obviously satirical magazine cover and tried to pivot to the conversation to talk about “cancel culture,” the host couldn’t let it go. “Let’s see if others in the mainstream media have the gumption to call out the fact that that’s just a complete lie,” Faulkner added of the cover that no one in their right mind would think was a literal image of the Oval Office as Trump left it. Obviously, Faulkner, in this reporter’s analysis, wasn’t in her right mind. Then, all of a sudden, my copy of The Week magazine arrived in my mail box.

WHOA! ANOTHER

RENDERING of Biden cleaning up the Oval Office mess his predecessor had left

behind. Clearly, The Week’s cover artist, Howard McWilliam, was

on the same wave length as Time’s O’Brien. But neither, of course, knew

what the other was drawing—that is, until both covers were out there for

everyone to see. (O’Brien’s Time cover, I later found out, was for the

online edition of the magazine.) As I sat here, smiting my forehead in wonderment at the sheer poetry of the situation—two nearly identical cover illustrations, one sending Harris Faulkner off the rails, the other inspiring no comment at all, certainly no such tirade—along comes the cover of Vogue with VIP Kamala Harris on the cover. And it, too, raised a ruckus. The photo on the cover was initially supposed to be the one on the left in the visual aid nearby. In it, Harris is wearing a black pantsuit and Converse sneakers. Nicely casual. But fashion critics and the social media said it appeared poorly lit, and others suggested it was “disrespectful” to the Vice Prez. The Washington Post’s senior critic-at-large saw nothing inherently wrong with the picture, but Vogue, in selecting the more informal photo for its cover, “robbed Harris of her roses.” Others said the image made Harris’s skin appear “washed out” and was out-of-keeping with Vogue’s glamorous aesthetic. (If it made her look “white,” it was also out-of-step with the times.) The result? The magazine opted for another cover photo, the one seen hereabouts on the right. A much more dignified portrait of the new Vip. It was created for Vogue’s digital edition, but will now also appear on the cover of a “limited run” of the “special inaugural edition.” Before

we leave this arena of ire-arousing pictures, we pause a moment to glimpse

actor/cartoonist Jim Carrey’s farewell portrait of the departing First

Lady, Melania Trump. He doesn’t make her look good. In fact, she looks

downright ugly. On the picture, Carrey wrote: “Oh —and goodbye worst First

Lady. I hope the settlement can finance your life in the shallow end. Thx for

nothing!” “Settlement” alludes to rumors that the Trumps will divorce as soon as they’re out of the White House. Some Twitter users have shown support for the message, while others are not so keen, reported Naina Bhardwaj at Business Insider. Steve Weintraub tweeted: "That's actually a pretty good likeness. You've captured the apathy and vapidity." David Peterson added: "Jim Carrey has an incredible eye for art. He truly captures her pure essence in this work. Masterpiece." Others disagreed, calling the representation of the erstwhile First Lady bullying and sexist. Carol Howard said: "Absolutely appalling to attack the first lady who did her job with grace and dignity and got nothing but criticism from everyone on the left. And it's shameful that not one woman from the left defended another woman for these baseless attacks." Yeh, well. She didn’t do much as First Lady—that we know about. But since she probably didn’t want the job anyhow, she at least didn’t sully the office, so to speak. Her first concern was/is her son. And she did that well, I gather. And that’s good enough for me. Whoever was it who decided that the First Lady—unelected to the position—should become some sort of national symbol. I think it was Lady Bird Johnson. But playing that role isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. Onward. Back to Trumperies editoons.

AS ALWAYS, David

Fitzsimmons’ pictures command and hold my attention. Near here, we’ve

posted two multi-panel Fitz pix at a size somewhat larger than usual in order

to showcase the details of his unique manner. Both editoons feature his highly

stylized caricature of the Trumpet. And both have to do with books. In each

instance, Fitz needs several panels in order to pile up his comedic indictment

of the Trumpet. And in the case of the cartoon at the top of the page, the

parody of Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon needs the space that

several panels create in order to complete the parody in verses. In the second cartoon, two or three distortions of book titles sets the mood, which Fitz then carries on to complete the fun he pokes at Trump. In

the next display, we see Trump as he sees himself and then as others see him. Kevin

“Kal” Kalaugher’s Trumpet at the upper left depicts the Prez, fat and

jowly, presiding over his “court” jam-full of sycophants, from Jared Kushner to

Mitch McConnell. We don’t know who the bulldog is in the next editoon around

the clock, but the mutt is undoubtedly doing the bidding of its master, who Steve

Benson draws as an overweight frizz-top. Next, Henry Payne’s imagery dramatically demonstrates how Trump has diminished in stature through the years of his presidency. And then R.J. Matson’s visual metaphor records an historic moment—when Trump is deprived of the means he has successfully used to muster his multitudinous cultists, his Twitter account. Without it, he is speechless. With

his graveyard imagery in the next exhibit, Steve Sack continues the

ridicule of Trump’s fixation with Twitter: he mourns the loss of his account

more than the death of an officer in the Capitol Riot. Next, we have Signe

Wilkinson’s metaphor for the Trumpet’s administration in which the Prez

does little more than feed the flames that are so destructive of American

institutions. Finally, Michael de Adder resorts to the cliche image of beating a dead horse in order to signal the futility of Trump’s whipping up voter fraud to achieve a victory at the polls. And with that, we end what might be the last Trumperies department. If the Trump fades from public view—and since he’s no longer Prez, that may happen rather quickly—he will no longer be consequential enough to command public attention, or the attention of the nation’s editoonists.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy FOR THE MONTH since our last posting, the Trumpet has been almost all there is of national news. His ability to snare the attention of the nation’s news media is unsurpassed. Even though he was sulking in private over his failure to be re-elected, he managed to get his name in the headlines at least once a day. That wasn’t all due to Trump’s superior initiative: the news media have become accustomed to his providing a sizeable ration of the day’s headlines, so rather than dig up more complex news to report, they take the easy way: they print Trump. The

“big news” of the month was nothing “new” or unexpected. Quite the reverse in

fact: Trump is leaving the presidency, right on schedule. Rick McKee’s metaphor

for the Trumpet’s departure is a still-burning dumpster, emblem of all he’s

been doing and his manner of doing it, and McKee depicts it in silhouette

heading off into the setting sun with Trump aboard. The fate of the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm is another of McKee’s topics. He shows the GOP thoroughly hollowed out, nothing left. But, as the Trumpet cheerily reminds the devastated elephant, conservative justices now outnumber liberal ones on the Supreme Court. Then, Trump may be leaving, Nick Anderson’s imagery reminds us, but the extremism to which he appealed and fostered remains, an ugly blemish on our culture and institutions. In

our next visual aid, Kevin “Kal” Kalaugher shows us the Trumpet about to

“give herd immunity a shot,” herd immunity being the way to beat the pandemic

without actually doing anything. In Kal’s metaphor, the amunition that he is

about to catapult at Covid-19 is people: before we reach herd immunity, a

certain portion of the population must die. Next, the lettering on the handle of the sledge-hammer in Clay Bennett’s offering reads “Trump legacy.” And we can see that it has had little effect on Obama’s reputation, which Trump dearly wanted to diminish. Next, Petar Pismestrovic’s image belittles Trump by showing that all that is required to get rid of him is a flick of the finger. And in Gary Varvel’s visual metaphor, the news media and Big Tech join the Democrank party in painting over the Trumpet’s portrait, thereby obliterating his legacy. Trump

will go out with a “bang”—as the only U.S. Prez to be impeached twice. In our

next array, in Steve Benson’s imagery, impeachment is a monster

battering ram run by Speaker Nancy Pelosi, which forcefully ejects Trump from

office. Pelosi’s remark recalls Trump’s program to get a vaccine developed

fast. Matt Wuerker’s image is simply having a little fun at Trump’s expense. GeeDubya took up painting after leaving the White House, so the gift Trump gets here is just a reminder that he’s on his way “out.” We used John Darkow’s editoon before, and it is so apt, I can’t resist using it again. To decode the imagery: the exorcist will purge the presidency of the evils presently inhabiting it (i.e., Trump). Even

when we take up subjects other than the Trumpet, he bullies his way in. He

introduces the Biden presidency, f’instance. In our next display, Dave

Whamond’s visual metaphor for Biden’s assuming the presidency is a sailing

ship about to go over the falls—perhaps to its destruction—Trump’s legacy.

Trump says “it’s all yours, Joe” as he hands him the steering wheel, which, as

everyone knows, is not functional if detached, as it is here, from the ship’s

rudder. Next around the clock, Bill Bramhall resorts to the image of the White House to announce not “new” management, but just plain “management,” the parallel emphasizing the lack of management under the previous administration. Then Signe Wilkinson’s image shows that Biden’s arrival inspires joy and happiness and hand-holding all over. Gary Varvel, a more conservative voice, naturally disagrees: he dubs his assembly of Biden supporters the “worstcooks in America.” A line-up of great caricatures. Biden

is regarded almost as a savior of his country—due largely to the horribleness

of the alternative, that of his predecessor. Drew Sheneman captures the

mood with his portrait of Lincoln that begins our next collection of editoons:

the second after Biden takes the oath, Lincoln is celebrating with a bottle of

champagne. (Incidentally, Stephen Colbert made a playful discovery about

Biden’s Secretary of State: if Anthony Blinken uses only an initial for his

first name, he comes out “ab linken.” Say it aloud. Well. Probably not worth

noting.) Lincoln shows up again in Dave Fitzsimmons’ picture of Biden at the Oval Office desk. The eyes that History has on Biden are those of two of the most highly regarded presidents in our history—Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. As usual, Fitz’s caricatures are both edgy and accurate. And his Biden is likewise a triumph. And just below Fitz, David Hitch suggests the difficulty Biden faces in trying for “unity” in the country: he’s caught between two extremes, both of which are best described as “bullies.” As Biden’s first acts are to abolish some of the Trumpet’s policies by Executive Order, Bill Bramhall suggests with a series of images just how significant Biden’s actions are likely to be. The closing caption, “to be continued,” tells us that the imperminence of presidential policies by Executives Order is likely to be asserted again in successive presidencies. All of which suggests that the best way to achieve permanence in policies is to get Congress to pass laws about them.

AND NOW, a short breather. A quick gallery of gag cartoons. Not much to say about them. In choosing these, I looked for the blending of picture and words. Do the words “explain” the picture? And vice versa? If so, it’s a good gag cartoon. If not, not. Beyond that criteria for this selection, I was attracted to simply silly premises. The guy who can’t read his shirt in the mirror, f’instance, has two “narrative” elements. First, that whatever’s printed on the shirt front is bound to be backwards if looked at in a mirror. Second, the guy is dim enough not to realize this. As a reader, you arrive at the “joke” (the laugh) by running through both of these elements in your head as you de-code the cartoon. One more thing. Take another look at the pyramid cartoon. Would the cartoon be improved if the caption were in a speech balloon that hovered over the speaker’s head? I think not. I think it takes a tiny bit longer to find the caption and then to read it. That length of time, however minuscule, enhances the joke by prolonging the moment of realization, which, in turn, prompts the laughter. Now, back to the Real World of Political Cartooning.

IN OUR NEXT

VISUAL AID, Steve Sack has Biden still signing Executive Orders, and

the image of competing piles of paper suggests not only the nature of the

competition but the size of Biden’s job. Last on this page is Drew Sheneman with a laughable image of some of the right wingnut warriors who stormed the Capitol on January 6. Moving

next into other news of the past month, we come first upon the arrival (or not

quite) of life-saving vaccines to combat Covid-19. First in the line-up at the

elbow of your eye, Bob Gorrell offers a blunt and bleak assessment of

the success of the vaccine roll-out—a tangled mess. In the same spirit, the

image of a maze captured the imaginations of at least two editoonists— Matt

Davies and Dave Granlund. The difficulty in finding a way to take

the vaccine is aptly illustrated by this visual metaphor. (I’m in one of the

favored groups—the elderly; I’m 83. And I’ve already had my first of two Pfizer

shots, which I obtained when my doctor’s office phoned last week and wanted to

make an appointment for me to get inoculated. Well, surprise. I did nothing

except have a regular doctor.) Steve Sack brings us up-to-date on the status of the inoculation program. As his medieval archer discovers, we’re out of vaccine. Or will be soon. Or might never be. Whatever the actual situation (still disputed), it is certain that without vaccine, we can scarcely fight off Covid-19. The government’s so-called plan (devised under that model of ineptitude, the Trumpet) was nothing at all, and states, left to manage by themselves without the centripetal influence of a national government, couldn’t coordinate or keep on moving the vaccine into the state and around. Or some other manifestation of malfunction. Our

next exhibit takes up riots, protests (whatever), and underrepresented groups. David

Horsey starts us off with a two-panel cartoon that compares—contrasts!— the

“conservative movement” of today with the same movement a half-century ago. The

dignified gray of Barry Goldwater on the left can’t compare to the right

wing-nut hordes of January Just below Summers, David Fitzsimmons creates a bellowing image of the Republicon Party. Now in the service of the Trumpet, the GOP is little more than a monkey megaphone spewing forth his lies and delusions. Then Mike Luckovich creates two telling images: one of the muscled-up law enforcement for Black Lives Matter demonstrations —compared to no muscle at all for Trump’s June 6 riot. An indictment of law enforcement’s inbred racism.

At the New York Times, David Leonhardt reported on the state of affairs in the wake of the riot in the Capitol on January 6—: The worst pandemic in a century is becoming more severe, with a contagious new coronavirus variant spreading and thousands of Americans dying every day. The mass vaccination program is behind schedule. Almost 10 million fewer Americans have jobs than did a year ago. The U.S. president, with the backing of dozens of members of Congress, has tried to overturn an election result and remain in power. Hundreds of his supporters overwhelmed police officers and stormed the Capitol, one of the few times in history that an U.S. government building has been violently attacked. All the while, the country lacks a president who has both the power and willingness to reduce the death, illness and mayhem. Instead, President-elect Joe Biden is left to rue that President Trump is denying the new government access to important national security information — and to plead with Trump to renounce the violence. Trump, for his part, appears disengaged from the worsening coronavirus crisis.

VARIOUS

COMPLAINTS ARE AIRED in our next visual aid. The National Rambo Association

(NRA) got a kick in the groin when it was disclosed that it is going bankrupt

because its treasury has been steadily looted by its executive director, Wayne

“Drooley Mouth” LaPierre, who spent the money on personal fun and tourism. Steve

Benson creates a vivid image symbolizing these developments. If you play

with firearms, they might blow up in your face. (Well, no: that’s not a

translation of the cartoon.) Next, Ted Rall examines the implications of Amy Coney Barrett’s candidacy for a seat at the Supreme Court. It takes at least four panels to create the hypocritical context. Gary McCoy also uses a multi-panel format to make his case (that, and the well-known visage of the world most famous German tyrant)—namely, that there is something fascistic about Twitter’s control of public speech. The deployment of several panels makes McCoy’s argument a little more subtle than he usually is. And then that old quack, Mallard Fillmore, is back to observe the ludicrous insanity of programs aimed at “purifying” our history by removing public adoration of any personage who ever did something that the modern day “woke” folk disapprove of. This could go on forever: with each new generation, more verboten topics and people will emerge. Just yesterday, my copy of The Comic News arrived. A monthly tabloid, The Comic News publishes editorial cartoons from cover to cover; it’s one of my chief sources for our Editoonery department. I could not post this Opus without including at least some of its harvest, but I’d already finished this installment of Editoonery. So the topics of the next two displays will be out of order. But the editoons are too good to postpone until Opus 414. Most

of the next exhibit ponders the Election, but we begin with Nick Anderson’s visual

metaphor for the Trumpet’s neglect of the pandemic. He’s playing golf while

Covid-19 racks up deaths. Next is Matt Davies’ picture of Trump fighting

the fraudulent election—while neglecting other matters of security, like

Russia’s hacking, another kind of stealing that is taking the hacked loot out

the back door while Trump raves on. The Trumpet portrayed himself as the victim of this alleged rigged election, and to emphasize his self-proclaimed victimhood, Matt Wuerker shows the poor abused Prez nailing himself to a cross—aha! A crucified Christ for our times! Meanwhile, the impeachment trial looms. Or not (however the gutless Senate decides). And Matt Davies returns with blunt imagery about Trump’s fitness for the office. Facebook and Twitter have already decided that he’s unfit; but the Senate is dithering on the question, while leaving Trump with unfettered access to the button that can blow us all up. The

Trump’s treatment of his Attorney General, William Barr, is the opening topic

in the next array. I can’t resist Nick Anderson’s picture of the Prez’s

delight at being presented with Barr’s head—by Barr himself, an indisputable

testimony to Barr’s loyalty to Trump. This may be the only picture in the whole

wide world of Trump’s visage dissolved into a monster grin. But the rioting in the Capitol gets most of the attention in this display. Someone whose signature I can’t read produced an impressive symbol of the riot-ready MAGA gang: matches just waiting to be set aflame. Below that, Jack Ohman has a little fun with a pair of pictures: the first of the stealing of Nancy Pelosi’s Speaker’s Podium, a picture widely circulated in the wake of the Riot; the second image, by duplicating the first but putting the Presidential Seal on the podium that Trump is walking off with, accuses the Trumpet of theft with parallel imagery. And then Steve Sack shows us a Proud Boy—namely, the Trumpet directing the destruction of American institutions, which is, here, set to music. And that’s this posting’s culling from The Comic News. Subscriptions to the paper are $33 for 12 issues. Order at P.O. Box 8543, Santa Cruz, CA 95061; or online at thecomicnews.com. This is no upstart overnight success: The Comic News has been going “36 inexplicable years,” as the editors say. So when you subscribe, you’re joining a thoroughly operative enterprise.

AND THEN I

THOUGHT we’d take a break from heavy-duty seriousness to ponder various ways

editoonists said farewell to Larry King. Jeff Danziger manages to dispose

of two obituary ’toons with one drawing. Then Randall Enos produces a

King image that takes exaggeration to an extreme (albeit effective). Dave

Granlund’s caricature of King is very nearly a realistic portrait, but it

contains just enough exaggeration (shape of head, lower lip) to qualify. And

adding the potential interview with God carries on in the King manner, a

fitting tribute to his life and work. At the lower left, Steve Sack indulges himself in producing an image of autumn color that must’ve been satisfying to do. Finally (yup: we’re approaching the end), in our penultimate assembly, Steve Kelley takes partisan prejudice to a nicely comical conclusion, baffling not only the male snowman-maker but some of us readers, too. But some of us got over it soon enough to appreciate the cloak of absurdity that Kelley casts over such enterprises as purging our culture of its under-recognized evils. Mallard Fillmore is back with an acerbic observation about the prejudices of the visual news media. And Clay Bennett, immediately below the duck, provides a visual metaphor for the commencement of the Biden Administration—a nation-wide reset button. And

then two editoonists report on their own engagement in the nation’s evils, ills

and maladroitnesses. In the first, Bud Plante recognizes the addiction

that drawing the Trumpet fosters, and then Phil Hinds breathes a sigh of

relief. Trump, being such an overblown clown himself, nonetheless required more than the usual measure of imagination to engage: nearly everything he said or did was a joke, so how to make today’s joke (a) effective on a public issue and (b) not an overt swipe of the Prez’s ludicrous actions. And you hold your breath (figuratively

speaking) until you’ve resolved the tension between the two by making today’s editoon. And now, for some fun. Ann Telnaes drew and lettered the next editoon, which is so encyclopedic that it requires two pages in our file. Entitled “All the Republicon Rats,” it depicts by name the states’ attorneys general and the Congressmen who signed on to the Texas protest, claiming the election in the several named states was fraudulent. We admire not only the sentiment but the patience and inventive skill to which the dozens of differently rendered rats testifies.

CLIPS & QUIPS Santa Claus has the right idea. Visit people only once a year.—Victor Borge All men are born free: just not for long.—John le Carre What we’ve relearned in this traumatic year is that all we hold dear is fragile, and that science, community, and empathy light the road forward.—William Falk, editor-in-chief, The Week

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping TIME FOR A

RAMBLE, one of those seemingly pointless wanderings through successive topics

linked by otherwise imperceptible commonalities. This Ramble started out as a

simple sampling of how the once-verboten is now almost commonplace in

syndicated newspaper comic strips. F’instance, the joke in T Lewis’ Over

the Hedge is that Hammy, the squirrely squirrel, has been supplying pellets

(er, rabbit turds) for RJ’s new grill. Well, turds, be they

rabbit pellets or some other kind, were not mentioned in comic strips for

several generations. As we have matured as a society and culture, pellets and turds are more likely to be found even in polite discourse. Hence, the once-eschewed have become signs of progress and, hence, our interest in them. I sometimes clip strips that have what I regard as unusual comedic twists—or, sometimes, words of wisdom. That’s how Kevin Fagan’s Drabble got here this time. And Tom Batiuk and Dan Davis’ Crankshaft arrived because it deals memorably with a common occurrence and I didn’t want to forget the strip. (Yes, this online magazine sometimes serves as a scrapbook of memorabilia-in-training.) And then, all of a sudden last month, when, searching for an apt illustration, I picked up my copy of Harvey Kurtzman’s Hey Look book collection, a handful of old comic strips fell out. (I sometimes “file” newspaper articles and comic strips and gag cartoons in books that seem somehow related; that way, if I ever pick up the book for some purpose, all this related material will be at hand to refer to.) Shoe, the first of the strips on faintly yellowed paper, by Jeff MacNelly offered a word of wisdom, so I kept it. But it doesn’t seem to me related at all to Kurtzman’s Hey Look. And neither does Bob Thaves’ Frank and Ernest, featuring those two legless ambling lumps of protoplasm. But here it is anyhow. Ditto

a couple of the Samson’s (Art and Chip) Born Losers on the next

visual aid; but they’re of the wisdom ilk. Then here’s Johnny Hart’s B.C. with an unusual scrap of reality. But what really started me off on this

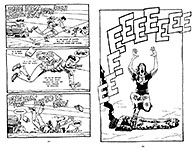

ramble are the two of Bud Blake’s Tiger strip. Blake is noted for his stunning deployment of solid blacks, but his style is distinguished by a sort of cobbled-up assembly of parts. His drawings of his characters look as if they were assembled from the feet upwards, piling up one anatomical body part (though fully clothed) on top of the previous one. And it all comes off beautifully. Another

of Blake’s stylistic achievements in Tiger may be described by terming

it “a-tumble.” The kids in his pictures are all “a-tumble”—small aggregations

of continual disorderly conduct, so to speak. An even better example of this

visual mannerism can be found on the covers of one of the two collections of Tiger in the Rancid Raves Book Grotto. An even more impressive example is in a marathon rendition of the chief Tiger characters, who sprawl across an 8x10-inch page in a stunning succession of wholly unrelated activities.

Another somewhat less spectacular ensemble is the cover of the first Tiger book collection, wherein the dog, Stripe, gets the punchline. And this cover illustration is accompanied by a line-up of the strip’s cast, taken from the book’s interior introduction. Two line-ups, actually. In the book, the two groupings depicted here appear in reverse order—that is, with Julian, Suzy, Bonnie and Hugo ahead of the other group, which concludes with Tiger and the dog, Stripe (again supplying the punchline). Scouring the Net for Bud Blake and Tiger, I eventually came to Rob Stolzer’s Inkslingers.ink blog. There, Stolzer raps occasionally about whatever is at the moment uppermost in his mind about cartooning. On a couple occasions, it was Bud Blake and Tiger. He describes Blake’s production of a strip:

“When

Bud drew his Sunday pages, he inked his rough version with a black marker,

coloring only the final panel as an Stolzer has several of the Sunday roughs with the final panel colored.Here are two—for July 11, 1999 and for October 12, 1997. When

fans wrote to Blake, asking for a drawing, “more often than not, Bud would clip