|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 409 (news thru October 27, 2020). The usual array of editoons covering the last month of the Presidential Campaign and unusual comic strips, plus five myths about Stan Lee, Trump and White Supremacy, comic strip anniversaries for Arlo and Janis and for Between Friends, and reviews of Black Heroes of the Wild West, Little Joe, and Brubaker’s Pulp and more. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order (the longest entries are marked with an asterisk* to help you decide where to spend your time)—:

NOUS R US Peanuts Is Seventy Tom Toles Bows Out DC Future State Open Letter on “Philip Guston Now” Rob Rogers Wins Award for Local Editooning 2020 AAEC Awards Sri Lankan Cartoonist Awarded for Courage Archie Thriving History Forthwith: For the Record Five Myths About Stan Lee

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of No.1s—: Negan Lives *Stillwater

THE EVAPORATING EDITORIAL CARTOON *A Modest Proposal by J.P. Trostle

*TRUMPERIES The Antics and Idiocies of Our Bloviating Buffoon in Chief The Election Super-Spreader Killing the Stimulus Relief Bill Trump Denounced White Supremacy (at least twice before) Mitch Wants Power; That’s All Editoons of the Trumpet

**EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy A Selective Survey of the Month’s Editoons

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping Pluggers Changes Creator Taboos and Other Naughtinesses in the Funnies Brenda Starr Is Back!

ANNIVERSARIES Between Friends, 30th Arlo and Janis, 35th

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Name-Dropping & Tale-Bearing Mae West Wrote Novels —Including Babe Gordon (The Constant Sinner)

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words George Lichtenstein (aka Lichty)

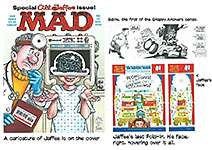

BOOK MARQUEE Tall Tales by Al Jaffee Jaffee Issue of Mad Black Heroes of the Wild West

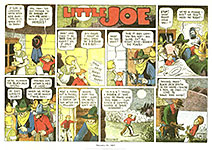

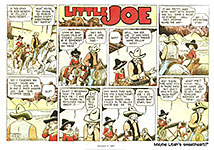

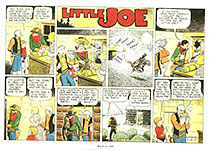

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets *Ed Leffingwell’s Little Joe

BOTTOM LINERS Single Panel Magazine Cartooning Roz Chast in The Comics Journal

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Called Graphic Novels for the Sake of Status *Pulp

Brubaker’s Near-Death Experience Influences His Books

WE’RE ALL BROTHERS, AND WE’RE ONLY PASSIN’ THROUGH Bob Weber Richard Lupoff Kai Shuman

FORTY-FIVE LIFE LESSONS

******

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em.

But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics. AND—

“If we can imagine a better world, then we can make a better world.”

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

PEANUTS IS SEVENTY Seventy years ago on October 2, 1950, Peanuts, a comic strip by then-obscure St. Paul, Minnesota, cartoonist Charles M. Schulz, made its debut in just seven newspapers around the world. In the seven decades years since then, Peanuts became one of the most beloved comic strips ever, with it's iconic characters appearing in thousands of newspapers as well as animated films, live stage shows and more. Charlie Brown and his imaginative beagle Snoopy are as familiar sights as Mickey Mouse, another iconic cartoon character. Santa Rosa's renowned Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center celebrates the comic strip's Platinum Anniversary and covers other timely topics with a fall season filled with public programs. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Schulz Museum will present the fall season entirely online, meaning Peanuts fans around the world will have the opportunity to join in the fun from the comfort of their own home. Fall 2020 at the Schulz Museum continues in November and December with more drawing classes and live conversations on topics such as the Black experience as told through graphic novels and comics. Advanced registration is required for all online events. Visit schulzmuseum.org to sign up for these events now. For other comic strip anniversaries lately, scroll down to Anniversaries.

TOLES BOWS OUT Eighteen years ago, Tom Toles slipped into the most envied editorial cartooning gig in the country— Herblock’s at the Washington Post. Herbert Block was among a handful of past masters at editooning, and the Post gave him a free hand for 55 years. After he died in 2001, the Post hired Toles to fill the slot. Surprisingly perhaps, given the legend whose shoes he aimed to fill, Toles did just fine, thank you—and became another legend in the process. Now, he’s retiring. The Herblock/Toles spot is open again, and the Post is looking to fill it. The thin ranks of America’s editoonists are doubtless quivering in anticipation. Toles’ last cartoon for the Post will be published on November 1. Whether he’ll return a couple days later for one final exit (in order to comment on the outcome of the Presidential Election) is anyone’s guess. Mine is that he will. Toles’ fifty year career as editorial cartoonist began at the University of New York at Buffalo and The Spectrum, the campus newspaper. After graduation in 1973, he cartooned at the Buffalo Courier-Express for 9 years, then 19 at the Buffalo News, which is where he was when the Post hired him in 2002. Since then, “he has been drawing six trenchant cartoons a week,” one of his editors wrote, saying the paper will “greatly miss Toles’ mordant skewering of environmental malpractice, presidential arrogance and Washington hypocrisies and pomposities of all varieties. Drafting four pencil sketches a day, five days a week, week in and week out, Tom set an almost unimaginable standard of consistent excellence.” He signed his cartoons with his name and, at the lower right-hand corner, seated at a drawingboard, a tiny self-caricature that uttered an ironic comment about the cartoon of the day. Toles

won the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1990 while at the Buffalo

News; and he won the National The Post will not be without an editoonist while looking for a replacement for Toles: “We are fortunate to be able to continue to publish the award-winning work of Ann Telnaes, our other regular cartoonist” (who has won both the Pulitzer and the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben as “cartoonist of the year”). The University of Buffalo maintains an archive of Toles’ early 1969-1973 work. While GoComics maintains a 25 -year archive of his later 1995-2020 work. And hereabouts, we’ve posted four recent efforts. If you have to enlarge the imagery in order to see and read the miniature Toles in the lower right corner, it’ll be worth your time and effort.

DC FUTURE STATE DC Comics dropped an annoucement of their forthcoming 2021 story arc DC Future State, a two-month event across the DC universe starting in January. The full title lineup will have a combination of monthly and twice-monthly oversize anthologies that give readers a glimpse into the DC superheroes in their future. In this story arc, the Multiverse has been saved from total annihilation, but in the process of saving it, the fabric of time and space was damaged. The final chapter of Dark Nights: Death Metal will kick off this uncanny future storyline. In other words, another fucking scheme to get us to buy every DC comicbook on the newsstand as soon as they appear. I’m confused enough as it is: I don’t need any more multiverses or alter ego superheroines.

OPEN LETTER: ON PHILIP GUSTON NOW (Over the Internet Transome; quoted verbatim here) We were shocked and disappointed to read the news that the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and Tate Modern, London, had postponed by four years their planned exhibition “Philip Guston Now,” which had already been delayed until 2021 by the Covid-19 lockdown. The reason for the postponement? The explanation given by the directors of the four institutions in their announcement expresses anxiety about the response that might be unleashed by certain paintings in which Guston depicts Ku Klux Klansmen, and their preference to “reframe [their] programming and … step back and bring in additional perspectives and voices to shape how [they] present Guston’s work to [their] public.” These institutions thus publicly acknowledge their longstanding failure to have educated, integrated, and prepared themselves to meet the challenge of the renewed pressure for racial justice that has developed over the past five years. And they abdicate responsibility for doing so immediately—yet again. Better, they reason, to “postpon[e] the exhibition until a time” when the significance of Guston’s work will be clearer to its public. The best riposte to the museum directors’ failure of nerve is conveyed by quoting Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer, as reported in the New York Times: “My father dared to unveil white culpability, our shared role in allowing the racist terror that he had witnessed since boyhood, when the Klan marched openly by the thousands in the streets of Los Angeles. “As poor Jewish immigrants, his family fled extermination in the Ukraine. He understood what hatred was. It was the subject of his earliest works. […] This should be a time of reckoning, of dialogue. These paintings meet the moment we are in today. The danger is not in looking at Philip Guston’s work, but in looking away.” Rarely has there been a better illustration of “white” culpability than in these powerful men and women’s apparent feeling of powerlessness to explain to their public the true power of an artist’s work—its capacity to prompt its viewers, and the artist too, to troubling reflection and self-examination. But the people who run our great institutions do not want trouble. They fear controversy. They lack faith in the intelligence of their audience. And they realize that to remind museum-goers of white supremacy today is not only to speak to them about the past, or events somewhere else. It is also to raise uncomfortable questions about museums themselves—about their class and racial foundations. For this reason, perhaps, those who run the museums feel the ground giving way beneath their feet. If they feel that in four years, “all this will blow over,” they are mistaken. The tremors shaking us all will never end until justice and equity are installed. Hiding away images of the KKK will not serve that end. Quite the opposite. And Guston’s paintings insist that justice has never yet been achieved. In the face of an action such as that taken by these four august institutions, we ask ourselves, as private individuals, what we can do. We can speak out, certainly. But we must do more. We demand that “Philip Guston Now” be restored to the museums’ schedules, and that their staffs prepare themselves to engage with a public that might well be curious about why a painter—ever self-critical and a standard-bearer for freedom—was compelled to use such imagery. That does not permit the museums to fall back on the old discredited stance: “We are the experts. Our job is to show you what’s of value in art and your part is to appreciate it.” It means that museums must engage in a reckoning with history, including their own histories of prejudice. Precisely in order to help take that effort of reckoning forward, the “Philip Guston Now” exhibition must proceed as planned, and the museums must do the necessary work to present this art in all its depth and complexity.

ROGERS WINS NATIONAL AWARD FOR LOCAL COMIC Rob Rogers’ Pittsburgh-Centric comic strip Brewed on Grant in the Pittsburgh Current won the Rex Babin Memorial Award for Excellence in Local Cartooning from the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. “I was shocked and totally, totally blown away by it,” Rogers said. “I was very honored.” Marc Murphy, a Kentucky cartoonist, was the finalist for the award; see the next report down the scroll. “It’s

truly an honor for the Pittsburgh Current to work with Rob and to

feature Brewed on Grant,” said Current Editor Charlie Deitch.

“Rob has a unique way of talking about what’s going on in Pittsburgh, both the

good and the bad, in a humorous and brutally honest way.” Because of the pandemic, said the Current’s Matt Petras, the judges awarded Rogers through a virtual event. “For decades, Rob Rogers has been a national leader in our profession, deftly satirizing not just national politicians, but also keeping a close watch on Pittsburgh politics and culture,” according to the AAEC judges. “He has been our AAEC president, and he is beloved for his manner and humor. He’s a courageous fighter for our profession, and at a critical moment stood up for his work and right to comment independently.” Brewed on Grant, a strip with musings on local politics and current events, originally ran for more than 20 years in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, starting out as black and white and later implementing full colors. After the Post-Gazette’s infamous decision to fire Rogers in 2018, the strip ended until Pittsburgh Current began publishing it in August 2019. The cartoon was also awarded the best in editorial cartooning this year by the Press Club of Western Pennsylvania. “Everybody said, ‘I’m so glad to see this back,’” Rogers said. “I had several people request copies of different ones.” Being awarded for local cartooning is especially exciting for Rogers because of the value he believes local cartooning has. “The cliche is that all politics are local, but that is really truly where changes can be made and where people’s lives are affected, is on the local level,” Rogers said. “I think it’s really important to have checks and balances on that level to keep a check on the people in power so that corruption doesn’t happen. “I really do think that we cannot underestimate the importance of local coverage.” (I think he means “overestimate.”—RCH)

2020 AAEC AWARDS The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists makes three awards each year, and usually joins with the Cartoonists Rights Network International in presenting a fourth one, the Courage in Cartooning Award. Here are this year’s winners—: The AAEC/John Locher Memorial Award to a student cartoonist for creativity in editoiral cartooning— Congrats to Catherine Gong! Catherine is a graphic designer, illustrator and cartoonist based in San Francisco who says that, in her covert rebellion against prejudice, her weapon of choice is satire. The 2020 judges said: “Catherine’s work demonstrates a range of commentary from strong and poignant to precise and funny, all skillfully drawn with a unique voice.” Cartoonist Tom Coute was named runner-up, and Emeka Perkins-Johnson, Sam Nakahira and Edward Wilson were also cited for their notable submissions. The AAEC Ink Bottle Award presented annually by the President of the AAEC “in recognition of dedicated service to the Association and distinguished efforts to promote the art of editorial cartooning”— This year’s recipients are Adam Zyglis, Ed Hall and JP Trostle, the trio of cartoonists who labored for several years to revamp the AAEC’s website, and update the look of the 64-year-old professional organization for the 21st century. The Rex Babin Memorial Award Excellence in Local Cartooning — Rob Rogers’ win is reported in the preceding story. Kentucky cartoonist Marc Murphy was named the finalist. Presented by Jack Ohman, JD Crowe, Kevin Kallaugher, the three judges had this to say about the finalist: “Marc

Murphy is a trenchant, sophisticated observer of Louisville and Kentucky,

and his work appears regularly in the Louisville Courier Journal—when

he’s not a practicing attorney and former elected official and activist. Marc’s

cartoons are The Robert Russell Courage in Cartooning Award — And last but not least, the AAEC is proud to stand with the Cartoonists Rights Network International in its choice for the 2020 Courage in Cartooning Award, Ahmed Kabir Kishore. More from CRNI Director Terry Anderson in the following report.

SRI LANKAN CARTOONIST AWARDED FOR COURAGE The Cartoonists Rights Network International presented its 2020 Courage in Cartooning Award to Ahmed Kabir Kishore. CRNI Director Terry Anderson had this to say in presenting the award: “Ahmed is a cartoonist and activist known to CRNI for over a decade. He campaigned bravely on behalf of the disappeared Sri Lankan cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda and jailed Bangladeshi cartoonist Arifur Rahman and identified as a CRNI ‘affiliate leader’ in the country, although doing so inevitably made him a target for accusations of aligning with foreign interests. This speaks to his courage, as do his public demonstrations for the human rights not only of cartoonists but also Hijra people and in defense of health and consumer rights and the Bengali language. “Through April and into May of this year Ahmed posted to Facebook a series of cartoons he entitled ‘Life in the Time of Corona,’ satirizing society’s response to, and critical of the government’s handling of public health during the pandemic.” “On May 5, 2020, Ahmed was among several people arrested under the Digital Security Act by personnel from the Dhaka division of the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB-3), the unit officially deployed against terrorists, drug lords and human traffickers but often accused of being an instrument of government suppression. Lawyers at the Ain-O-Shalish Kendra (ASK) legal aid organization have seen the charge sheet and tell us that Ahmed is alleged to have taken part in a ‘conspiracy, spreading rumors and misinformation against the prime minister Sheikh Hasina and her late father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.’ Ahmed is alleged to be an administrator on a Facebook page called ‘I am Bangladeshi,’ which is considered as the main subject of investigation by the authorities. “In the ensuing months of detention Ahmed has been denied a bail hearing on three occasions and subjected to periods of what’s described as ‘jail gate interrogation,’ this despite the ongoing and imminent threat to prison populations posed by corona virus COVID-19 and the release of literally thousands of criminally prosecuted people from jail in Bangladesh for precisely that reason. Ahmed is an insulin-dependent diabetic, meaning he should be afforded some extra protection from infection. “CRNI has petitioned the prime minister on Ahmed’s behalf along with ASK, Cartooning For Peace, Forum for Freedom of Expression, Bangladesh (FExB) and Reporters Without Borders. Our request for clemency has been ignored. “The intent of the Robert Russell Courage in Cartooning Award is to recognize the plight of a cartoonist experiencing a human rights violation — and in our view that is precisely what has happened to Ahmed, several times over — as well as raise their profile in the hope that doing so will help bring about a favorable resolution. 2020 has been an extraordinarily, exceptionally bad year. “We could have presented the ‘Robert Russell’ to European cartoonists whose censure was requested by Chinese diplomats, to a Jordanian cartoonist arrested for caricaturing the crown prince of the UAE, Brazilian cartoonists harassed by law enforcement, an Algerian cartoonist detained for ‘disrespecting’ the military or a Palestinian cartoonist subjected to mass internet trolling and death threats over a cartoon to which Saudi Arabians took offense. “Circumstances have been so bad that we were forced to make an emergency statement in the spring, warning that lasting and potentially irreparable damage would be done to the global community of cartoonists in 2020, due in large part to the license the pandemic has granted to authoritarian regimes. “Therefore Ahmed Kabir Kishore’s case is emblematic of the times in which we live; his freedom to express skepticism and dissent has been violated and that in itself would be sufficient to attract our attention, but for the last six months his life has been needlessly put at risk by detention in jail – universally recognized as an environment where corona virus is a higher risk – and despite his health condition – again, universally recognized as a contributing factor to illnesses such as COVID-19 “In presenting the Robert Russell Courage in Cartooning Award 2020 to Ahmed Kabir Kishore, we call for his immediate release, his total exoneration of all criminal charges and an independent investigation into his treatment while a detainee.”

ARCHIE THRIVING By Newsarama Staff Twenty-twenty has been a year no one expected, including Archie Comics. But they've rolled with the proverbial punches, and have made several announcements in the final months of 2020 as they prepare for Archie's 80th anniversary in 2021. In the past 30 days, they have: ● Made a deal for all their comics to debut day-and-date on comiXology Unlimited as it will in comic stores. ● Partnered with Webtoon to begin original Archie webcomics on the platform. ● Signed a deal with Spotify for a series of audio drama podcasts. ● Amazon Prime Day deals: see all the best offers right now! While its flagship title Archie remains on hiatus, the publisher has already made plans to resume the publication of new Archie Comics through the end of 2020 and into 2021. With everything going on, Newsarama reached out to Archie Comics' co-president Alex Segura to get a big picture look at the company, its plans, the impending 80th anniversary, and the hiatus of the main Archie title. What follows, Segura’s remarks culled from the interview with him—: The mentality during those early days of the shutdown was to hang on and be flexible. We tried to do the best we could, make sure we were putting out product that could entertain and distract during these extremely difficult times. ... Yes, Diamond is back and we're thankful for that, and we're extremely grateful to the comic shop retailers who are engaging with customers and selling the books we create. Running a comic shop has never been an easy job, and we're all blown away by their passion and perseverance during these unprecedented times. ... In terms of challenges— we have to be more judicious than ever before. ... It doesn't mean we don't take flyers: I think anyone can see that Archie, at least over the last decade under Jon Goldwater's leadership, has been all about taking risks and realigning how people perceive our iconic library of characters. So, the idea has been to spread out the publishing slate we'd planned for 2020, and let some of those books roll into 2021, with an eye toward back-checking those launches and making sure we're confident and comfortable before moving ahead. We're also rethinking how we engage with our backlist. We have almost 80 years of content, with new material being scanned and remastered every week. ... We've simultaneously expanded into new markets and retailer outlets that were previously unavailable to us— places like Costco or grocery store chains that hadn't stocked some of our products before. We continued to supply products through our webstore, selling directly to fans, and created new digital exclusive material to fill in some of the gaps in the schedule that opened up. We began publishing free stories on our social media pages which helped brighten the days of many fans during a difficult time. We had to think about how to serve our various readerships in ways that allowed us to stay nimble and responsive to not only the direct market, but publishing and distribution as a whole, and I think we did that well— it's a testament to how we came together as a company to stay focused and moving forward. Asked when he foresees returning to a schedule with more new, original material, ala prior to the April shutdown, Segura responded—: You're seeing it start to ramp back up already ... We just released our first-ever original graphic novel, Betty & Veronica: Bond of Friendship, in comic shops and bookstores last month. That right there is the new content equivalent of a five-issue mini-series, and we have an all-new Riverdale OGN launching in February. ... A new Madam Satan one-shot is launching in just a couple of weeks that we're very excited about, and that was in the works prior to the shutdown. During our New York Comic Con panel, we announced a new Riverdale Presents: South Side Serpents one-shot and two new digest series which will feature extended new lead stories in their debut issues. And new lead stories in the 'classic' Archie style are returning to our digest publications beginning this week. All of these decisions were made months ago - it just takes time to start to get things back in motion and out the door - especially now with a remote workforce. ... Archie is our longest-running series, and to many our flagship. ... We pivoted and did a "series of mini-series"— with Archie and Sabrina— followed by Archie and Katy Keene, all under the umbrella of the ongoing Archie book, but still with clear, Number-One-like jumping-on points for readers. That did well enough for us, but not so well that we felt confident riding out the shutdown publishing new issues. The end of Archie and Katy just dovetailed with the Diamond shutdown, so it gave us a minute to rethink and re-tool. There was a project that we had slated in for this summer that would have fit in this spot very nicely but we had to reschedule it. We'll have a few major announcements relating to the mainline Archie series fairly soon— keep an eye on this as we head into the new year. ... Next year is Archie's 80th anniversary, so you'll see a lot of content geared toward that— celebrating the past but also pointing to the future. Our new Archie 80th Anniversary Digest and World of Betty & Veronica Digest series are a part of that. ... We'll have a major, Archie-centric announcement in the coming months, plus some news on other properties that I can't get into now. Additionally, we'll continue our Archie Blue Ribbon line of original graphic novels with Riverdale: The Ties That Bind, by writer Micol Ostow and artist Thomas Pitilli, a new Riverdale Presents: South Side Serpents one-shot by David Barnett and Richard Ortiz, and a few other surprises. In addition to that, we just announced our partnership with Webtoon and that we'll be creating new comics content specifically for their platform in 2021. We're also building and expanding on the great successes we've had with current partners like Scholastic and Little Bee, who've brought greater awareness to our amazing characters in the YA and children's book markets. There's a lot to look forward to in 2021 and I'm eager to see how people respond to it.

History Forthwith: FOR THE RECORD Modern comics scholarship began, I believe, with All in Color for a Dime (1970) by Dick Lupoff and Don Thompson although an excellent case can be made for Jules Feiffer’s The Great Comic Book Heroes (1967); and, shortly thereafter, Jim Steranko’s Steranko History of Comics in 2 volumes (1970, 1972). The cluster of useful scholarship accumulated around the end of the 1960s and the early 1970s. The Penguin Book of Comics by George Perry and Alan Aldridge came out about then (1967 revised in 1971). Meanwhile, Reinhold Reitberger and Wolfgang Fuchs were at work in Germany on Comics: Anatomy of a Mass Medium, which was translated into English and published in this country in 1972. That same year, The Art of the Comic Strip, a collection of essays edited by Walter Herdeg and David Pascal, appeared. After which came Arthur Asa Berger's The Comic Stripped American (1973), followed by Ron Goulart's Adventurous Decade (1975). Then came a special comics section in the Journal of Popular Culture, Spring 1979—a collection of essays edited by M. Thomas Inge. I’m leaving out a couple of books that were essentially reprints of strips and/or comicbook stories without much scholarly text. The 1980s were barren, oddly—considering so much was happening in comicbook publishing (maturing stories and characters, new publishers, including alternatives). Not much happened until—: Comics as Culture (1990) by M. Thomas Inge The Art of the Funnies (1994) by Robert C. Harvey The Art of the Comic Book (1996) by R.C.H. Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art (1996) by Roger Sabin All of which is just for “the record.” I was attending a scholarly session at a convention a couple years ago, and one presenter recited the history of comics scholarship by listing early authors of comics-related tomes. I don’t remember that any of the people or works I just cited were among those he mentioned. Maybe Jules Feiffer and Jim Steranko. But probably not Lupoff and Thompson. Okay: I’m miffed because I was also overlooked. But more significantly, Tom Inge wasn’t mentioned. And he’s responsible for more comics scholarship than just about anyone. He was (and still is) consulting with the University Press of Mississippi and urged me to submit something—hence, both of my books above. (Which were submitted to the University Press as one book; they said it was too long for one book, and so it was published as two.) So you could say that of the thirteen earliest scholarly books on comics, Inge was responsible for four of them. That’s thirty percent. Someone should take note of that. For the record.

FIVE MYTHS ABOUT STAN LEE Scandal by Abraham Riesman, Washington Post Riesman is a journalist and the author of True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee, set to be released by Penguin Random House on February 16, 2021. In the following article, Riesman proves once again that all it takes is the death of some notable for the notable’s envious critics to come out from under the rocks where they usually dwell and smear the notable about whom the critics were too timid to assault while he lived. Here’s Riesman—: Stan Lee gained renown for co-writing and promoting the Marvel line of comic books in the 1960s, then went on to sell himself as a brand and media personality until the day he died, just shy of his 96th birthday. But as beloved as he is, his life and work are often poorly understood.

Myth No. 1 — Lee created the Marvel Universe. Lee has long been credited as the driving force behind the pantheon of Marvel superheroes that took the world by storm: Spider-Man, the Avengers, the X-Men, Black Panther and so on. His obituaries from news outlets such as NBC News and Reuters all characterized him as the comics’ “creator.” Others (such as The Guardian) that are a little less expansive with bestowing credit on him will say he co-created the characters with writer/artists Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. There is actually zero evidence that Lee had the initial ideas for any of these characters, other than his own claims. In his 2002 memoir, for instance, he said of Ditko: “I really think I’m being very generous in giving him ‘co-creator’ credit, because I’m the guy who dreamed up the title, the concept, and the characters.” The world has generally accepted that Lee had the initial notions for the characters, only then passing them off to Kirby or Ditko. But over the course of legal cases, painstaking historical debate and my own archival research, nothing has ever been turned up that proves — or even suggests — that Lee was the driving creative force. No presentation boards, no contemporary notes, no diary entries, no supporting accounts from anyone other than his wife. Nothing. (Maybe it’s a mistake to look for documentary evidence in such matters, particularly in the deadline-driven catch-as-catch-can creative world of comicbooks.—RCH) Meanwhile, Kirby and his defenders have asserted that Kirby was the characters’ sole creator, accurately pointing out that he had a far longer history of creating successful characters on his own. Same goes for Ditko. Because of the fly-by-night record-keeping practices of the mid-century comic-book industry, it’s unlikely that we’ll ever have a firm answer. But companies, journalists and historians can’t say with any certainty that Lee created (or even co-created) Marvel’s dramatis personae.

Myth No. 2— Lee loved comics and superheroes. Countless people take for granted that Lee was personally enthusiastic about comics. Geekdom and conventional wisdom assumed so; even the Library of Congress has characterized him as “Comics’ Champion.” He did perpetually talk up the power of comics, probably bolstering the perception that he was a fan: “Superhero movies are like fairy tales for older people,” he told The Washington Post in 2011. “I don’t think they'll ever go out of vogue.” According to private accounts from his archives and the words of those who knew him, Lee really couldn't stand — and didn’t read — comic books. In conversations with creatives such as Alain Resnais and Francis Ford Coppola, in his memoir and even in speeches to his colleagues, he spoke at length about how he had no innate love for the medium and had merely taken it up through happenstance. It was just a hustle for him, one he repeatedly tried to escape through schemes to make it big in movies, poetry, even encyclopedias. He spent much of his post-’60s career trying to pitch non-superhero ideas in various non-comics formats. According to his former manager and his former bodyguard, he loathed superhero movies and probably saw only about two of them in his life. (He typically left their premieres after walking the red carpet.) (So he didn’t like comicbooks. That’s no big deal.—RCH)

Myth No. 3— Lee wrote the comics he published at Marvel. Lee was nearly always credited as “writer” in the credits of his comics, with his writer/artists listed as “artist.” Examples abound of the public accepting this categorization, including in serious-minded outlets such as The Economist and New York magazine. But the publishing company produced comics through a strange process now known as “the Marvel Method,” whereby, typically, Lee would have a conversation of some kind with his writer/artist to discuss a few ideas. The writer/artist would take that prompt and write the story in visual form by drawing the pages and placing clarifications and dialogue suggestions in the margins. After that, Lee would add the dialogue and narration. He virtually never wrote actual scripts. And tossing around concepts with a writer/artist is the task of an editor, not a writer. (Sorry: I disagree. Admittedly, the artists did more “storytelling”—the usual function of a writer—than is commonly supposed. But that doesn’t mean Lee didn’t also function as a writer.—RCH.) Given that the writer/artists — most notably Kirby and Ditko, but also such titans as John Romita, John Buscema, Wally Wood and Don Heck — actually constructed the story, they should be considered the true, primary writers, with Lee doing embellishment (however crucial such embellishment may have been to the work’s success).

Myth No. 4— He was a political progressive. Left-leaning Marvel fans have often held Lee up as a hero for those who seek to fight inequality and bigotry, calling him a “progressive genius” and a “true ally for people of color.” Some point to the occasional moments when he would write short editorials vaguely decrying racism. Others offer interpretations of his heroes as underdogs who represent the downtrodden — particularly the X-Men, who have often been taken as allegories for Black or queer people (despite Kirby and Lee both saying they were primarily just a sci-fi concept about mutation). Lee couldn’t be called right-wing, but his politics had a conservative bent. He often wrote and spoke about how reactionaries and radicals were equally wrong and privately complained about how taxes in America were too high. In the midst of the anti-establishment riots of 1968, he convened a panel for a failed talk-show pilot in which he repeatedly denounced radicalism; asserted that Black people needed to respect the law; and said the Vietnam War may have been immoral, but had to continue for the greater good. These ideas were of a piece of the way he’d depict the hot issues of the day in the comics he co-wrote, particularly in stories about Spider-Man and Captain America confronting campus protests: They always featured good guys on both sides who succeeded by meeting in the middle. (So, he wasn’t just an “embellisher” after all: he was a co-writer.—RCH) And, of course, the vast majority of the characters he wrote for were white and male. All of this should give people pause when they tout him as a champion of the progressive politics of 2020. (For people of Lee’s generation, to be a “conservative” was not so much KKK as it is now.—RCH.)

Myth No. 5— Lee made a lot of money from Hollywood. Given that Marvel film and television adaptations have made tens of billions of dollars and that the company names Lee as one of the co-creators of the intellectual property underlying the franchise, one can be forgiven for assuming — as outlets such as the Daily Star and Playboy have — that Lee took home a huge chunk of that cash. “Did you at least get a [Tony] Stark-like helicopter in the deal?” an interviewer asked, after Disney bought the comics publisher. As a 2014 article in Comics Alliance observed, Lee often “worked hard” to project an image of himself as “a tremendously wealthy comic book mogul primarily responsible for the success of some of Marvel Comics’ most iconic — and profitable — superhero characters.” But Lee earned only a day rate for filming his cameos. Although Lee died with wealth (we should hesitate to estimate his exact net worth, but he claimed it was well below $100 million), much of it accumulated through various contracts with Marvel over the decades, it didn’t stem from film and television projects. Lee didn’t actually own Marvel Comics — it was created by his cousin-in-law Martin Goodman and went through a long succession of corporate parents, culminating in Disney today. Even more shocking, he didn’t have any ownership of the characters he was credited with creating. One of the great injustices of the comic-book industry is that the biggest publishers, Marvel and DC, treat their writers and artists as freelancers who do work for hire, and thus typically cede all rights for the characters they create to the company. As a result, Lee’s fortune was a microscopic fraction of the revenue that Marvel generated. (Well, then—where did Lee get all the millions he’s supposed to have in the bank? No one has assumed that he made a fortune with cameo roles in superhero movies. I thought he did ’em for free and for fame. As I understand it, once the Marvel movie industry got underway, he successfully re-negotiated his deal with Marvel so he’d get a suitable share of the revenue. But what do I know? Probably not much more than Reisman.—RCH)

ODDS & ADDENDA Kamala Harris’ life story is getting the comicbook treatment. TidalWave Comics is proud to announce the addition of Kamala Harris comicbook to its popular “Female Force” series focused on female empowerment. Female Force: Kamala Harris was released on October 21st in time for her birthday. In the fourth issue of Image’s Adventureman, the title character actually shows up—a remarkable occurrence because he and his adventures are entirely imaginary in the mind of, say, Claire, the hard-of-hearing bookshop owner. And the other remarkable thing about this issue is that it devotes two pages in the back to telling people how to register to vote (and listing the deadlines of every state). Yes, remarkable. Rob Stolzer, who teaches art in college and has been collecting cartoon works for 40 years (it sez here), has a great blog at inkslingers.ink/blog/. Among the postings are a couple of Bud Blake (Tiger) demonstrations of visual comedic genius (including pencil roughs) and a pre-Wonder Woman history of H.G. Peter, whose cartoons for the old humor magazine Judge (1881-1947) do not at all suggest the style he deployed later in comic books.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, who covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these three other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com (now operated without Gardner by AndrewsMcMeel, D.D. Degg, editor); and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO Here’s one to remember from a woman who posted it on her Facebook page: My dad died of Covid less than two weeks ago. He did not have access to a team of doctors and nurses or a helicopter at his beck and call. (And you won't either) He was not given experimental treatments and the best care in the country. If the president gets worse he will be able to have his family suited up in the same protective gear that healthcare providers wear to be with him, my father got to see us for a few minutes a day on Facetime. Both my husband and I also had Covid. I had a fever for 3 days and suffered from fatigue for much longer. Scott had a fever for more than 10 days, his oxygen levels started to dip low enough that I thought I would have to take him to the hospital. Luckily it didn't come to that. A month later and he is still tired and has a cough. I am angry that this president is making it seem that you can beat this virus if you are just determined enough. I agree that you should not be afraid of Covid, but you still need to take precautions, wear a mask, wash your hands and if you test positive don't take your infectious, mask-less ass out in public to infect others.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

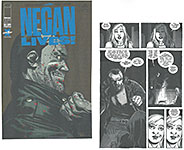

TO THE BEST of my knowledge, I never—not once, not ever—looked at anything Walking Dead. So the name of this comic book, Negan Lives, held no special meaning for me. In fact, the name Negan had no special meaning for me until after I’d read the book and enjoyed it, and, at the end of it, read an epilogue by the book’s writer, Robert Kirkman, in which he explains why he didn’t kill Negan off, as he’d planned to, in No.174 of The Walking Dead. I’m glad I didn’t know Negan was a character of Walking Dead renown because had I known that, I wouldn’t have bought the book and I would therefore have missed one of the most promising first issues around. As it happens, I bought the book because the cover intrigued me. Just the picture, not the name Negan. We encounter Negan as he picks flowers and talks to them for the first couple pages. It then emerges that he is apparently all alone by himself, the sole survivor perhaps of something that has killed his wife and everyone else in the world. And then this cute chick shows up. He soon realizes that she’s up to no good—and, right enough, two thug show up and try to kill Negan. He resists. So successfully that he kills them. (Well, one of them is killed by a couple of the walking dead, who show up and completely surprised me.) This episode shows that Kirkman and his illustrator, Charles Adlard, know how to develop both story and episode. It also reveals that Negan is no slouch.

What Negan will do in a world without much human populace except walking dead people, I dunno. But it’s a provocative premise, so I’ll go along Adlard’s drawings—all in black-and-white with gray tones—are crisp and clean and pleasant to look at. And he and Kirkman repeatedly demonstrate storytelling chops with pacing and panel composition, relying several times on silent (wordless) passages, the presence of which is almost always a tip-off: these guys understand the medium and deploy its capabilities expertly.

DANIEL WEST JUST GOT FIRED, so no one, certainly not his friend, Tony, who buys drinks for him, thinks the less of him for getting drunk. And then he gets a letter from a law office, telling him that he’s inherited money from a great grand aunt he never heard of. The letter doesn’t tell Daniel how much money, so he takes Tony with him, and they drive to the town where the law office is, Stillwater, hoping to find out more about his fortune there. Writer Chip Zdarskky names this comic book after the town Daniel and Tony drive to. And with good reason, as we soon learn. They stop for gas en route, and when they ask the station operator about Stillwater, she apparently has never heard of it. Since the town is only an hour away, that seems odd. But that’s not the end of odd with Stillwater. When they get to the town, they visit a diner to eat, and the waitress there says the lawyer they’re looking for hasn’t lived there for fifteen years. While they’re talking, Tony looks out the window and sees two kids on a rooftop, one of whom shoves the other off the roof, and the kid falls a couple stories to the ground. Daniel and Tony run out to attend to the kid, find he’s still alive, and take him to a doctor’s office on the corner. There, the kid miraculously recovers and abruptly leaves the premises. Daniel dashes out in pursuit, but the kid has disappeared. He roughly asks a citizen if he’s seen the kid. This attracts the attention of the local cop, but Daniel is having none of it: he takes a swing at the cop, who belts him in return, then breaks his arm. Summoning help, the cop and his helpers take custody of Daniel and Tony and take them out of town, to where one of the cop’s minions has built a huge fire. “I’ll kill you!” Daniel shouts in exasperated fury. “You can’t kill me,” the cop says. “You can’t kill any of us. I mean, you can out here—but past that fence,” he gestures back toward the town, “—in the borders of Stillwater? My home? Nobody dies. And I aim to keep it that way,” he adds, taking out his revolver. “But out here?” And he puts the muzzle of his gun up to Tony’s forehead and shoots. Just as he’s about to do the same with Daniel, a woman drives up, jumps out of her car, and yells, “Wait!” She runs up to Daniel and grabs his face. “My boy,” she says, “—you’re back, you’re back.” End of book. So Stillwater is a weird town within the borders of which no one dies. Remember the kid who fell off the roof? He’s fine.

Provocative enough for me. I’ll be back. Ramon K. Perez turns Zdarsky’s tale into imagery with a breezy, flexible line, and the two of them display a mastery of the medium, energetically pacing the action by changing the focus from panel to panel. The opening sequence with Daniel getting drunk twice shows our authors understand how to tell a story. Perez also draws the gun blast that kills Tony with visual aplomb and an able assist from colorist Mike Spicer.

QUOTES & MOTS

The recent demise of the new material print magazine was, he says, “mission accomplished. You know, there wasn’t much more it could do.”

THE EVAPORATING EDITORIAL CARTOONIST By J.P. Trostle Ever find something you completely forgot you drew or wrote? Tonight I went looking for an article I wrote some 15 years ago and — with the alt-weekly's site long obliterated — had to pull up the html files of a defunct personal site from a backup drive. In the folder was also a piece on editorial cartooning that I have no memory of writing. The fact that it never appeared in print might have something to do with that. The circumstances around it's creation are a bit muddy as well, but it is clear the Los Angeles Times quoted me in an news item [when Michael] Ramirez left the paper, and I felt the urge to respond. In retrospect it's a fairly shameless rip-off of Jonathan Swift — and it's obvious why the LA Times never ran it. But hey, you might find it, uh, amusing.

A Modest Proposal [The following was a guest column written for the Los Angeles Times in November 2005. It got killed at the last minute however, and never ran ... gee, I wonder why?] Two weeks ago, in an LA Times article announcing the axing of editorial cartoonist Michael Ramirez, several statistics from a piece I had written for Nieman Reports about disappearing cartoonist jobs at newspapers nationwide were cited. I had considered responding to the news at that time, but the outpouring of outrage and annoyance from readers said much of what I wanted to say. I might have included a few additional statistics, such as that numerous reader surveys in recent years have consistently placed the editorial cartoon, particularly by a paper's own staff cartoonist, as one of THE top items readers look for, or that in 2005, during a period when newspapers were hemorrhaging subscribers, one of the few papers in the country to actually grow in circulation was the News & Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina— and they added TWO MORE cartoonists to their roster this year. (A coincidence? I'll leave that up to you.) I could have asked what the Los Angeles Times intended to do with the space formerly occupied by the editorial cartoon. Did they really think an additional 12 column inches of text — the equivalent of one more letter to the editor, or, 250 more words by, say, a Jonah Goldberg— would have anywhere near the visceral impact or insight of a single Ramirez cartoon? Will simply providing more words stop the stampede of readers to other media? Or did they intend to use that open space to sell advertising? In many ways, this recent decision does come down to money (as Ramirez himself mentioned in the November 11 article), but does management believe they can keep up the paper's double-digit profits by getting rid of big name staff members? Does the Tribune Company, which owns the Times, really think that trimming the salary of a cartoonist will help them pay off the nearly $1 billion they may owe to the IRS? Apparently so. In the last two weeks, the Tribune Company has given take-it-or-leave buyout offers to at least two other staff cartoonists at prominent newspapers it owns, and are considering giving the same to three more [destined to depart] as part of a chain-wide reduction in newsroom employees. And as at the Times with Ramirez, it is widely considered these editorial positions will be eliminated entirely. Since it is clear now that the Tribune is targeting cartoonists, I would like to make a modest proposal. Sure, they can save some money by firing Ramirez and the others, but that's shortsighted; they're only using part of what editorial cartoonists have to offer. Do you have any idea what organs bring on the black market these days? A good heart and set of lungs can easily get you 50 grand. While our spleens may be shot from overuse, kidneys, livers and gall bladders are all in great shape. And do I really have to point out how prized the eyes of an artist might be? But you're right, simply harvesting our organs isn't going to be enough. Therefore you may as well be sporting about it and auction off hunting rights. There must be SCORES of politicians, public officials, and celebrities who would be happy to shell out big bucks for a shot at the editorial cartoonists who mocked them and made their lives miserable. Why, Pat Oliphant's head alone would be worth half a mil or more. (Granted, Paul Conrad —who won two Pulitzers for the Times — is getting up there in years, but if you gave him a 10-15 minute head start it would at least make things more interesting.) I know, I know, these are all short-term solutions— and Tribune executives will soon be asking about the next year, the next quarter. Well, there's always the features department.

J.P. Trostle is a cartoonist for The Chapel Hill Herald in North Carolina, and the editor of Attack of the Political Cartoonists. His article "The Evaporating Editorial Cartoonist" appeared in the Winter 2004 edition of Nieman Reports.

MOTS & QUOTES “A culture war is something only the other side fights. The side you are on is merely talking sense.”—Journalist Robert Shrimsley “Humor can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process, and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind.”—E.B. White “The secret of staying young is to live honestly, eat slowly, and lie about your age.”—Lucille Ball

TRUMPERIES The Antics and Idiocies of Our Bloviating Buffoon in Chief

The Election. As you read this, we are within a few days of the 2020 Presidential Election being concluded. The Trumpet has stubbornly refused to say whether he will go peacefully if he loses, and every indication is that he will lose. Of no other president facing re-election has the question ever been asked: Will you go quietly into that good night? The answer in Trump’s case (whether he is ready to admit it or not) is: Yes, I will. How do I know that? Because to do otherwise would take balls. And one thing we’ve always known about bullies is that they are, at heart, cowards. And Trump is a first-class bully. To deny the results of an election is not simply to refuse to accept the results. It is also to buck a couple centuries of democratic government and the culture thereof—and to thwart the expressed wishes of a huge segment of the society that surrounds him who voted for the other guy. Trump hasn’t the guts for that, kimo sabe. He’s tinkered with the norms of his office, and he’s frustrated many of us with respect to “how things are done.” But to bully his way past history and an entire culture? —that takes more courage than he has. Oh, he’ll stomp his feet and bluster about how the election is rigged. But he won’t actually do anything except shoot his mouth off. And we’ve become immune to that.

The

Trumpet Returns! On

Monday, October 5, the Trumpet returned to the White House after spending the

weekend at Walter Reed Medical Center being treated for Covid-19. On Monday, he

was still contagious and would remain so for maybe another ten days. Yet he

symbolically removed his face mask for a photo op. His gesture raised new

alarms: he undoubtedly did not intend to wear a mask inside the White House

while working, thereby hazarding the health of his staff, who would be working

around and near a contagious virus-spreading blowhard. And there are already

reports of several staffers who’ve tested positive. Thanks a lot, boss. In yet another thoughtless and reckless maneuver, the Trumpet announced to the world that no one should fear the virus: “Don’t be afraid of it,” he said. “You’re going to beat it. We have the best medical equipment; we have the best medicines.” His remarks were strong, a reporter noted—but he was taking deeper breaths than usual. Morever, he childishly believed his experience with the virus was typical for all Americans. Not so. “Trump’s experience with the disease has been dramatically different from most Americans, who do not have access to the same kind of monitoring and care. And he was given experimental drugs not available to the public.” That’s our Prez, kimo sabe. It’s all “me, me, ME.”

Trumpet Extortion. For a couple days last month, the Trumpet resorted, briefly, to extortion in order to win the Election. In another of his legislative power plays, the Trumpet ordered negotiators to stop discussing a new stimulus deal until after the election. Once he’s elected, he said, he’ll push through a magical relief bill that will make everyone rich beyond their wildest dreams. Oh, sure. Elect me, and I’ll reward you. I’ll release the hostage. His announcement sent stocks plunging and sparked new uncertainty among people in particularly hard-hit industries, like airlines. While Congress has butted heads for months over stimulus proposals, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin seemed to be mounting a strong new effort to get a deal done soon. But the Trumpet will have none of it. Then a couple days later, he reversed himself. He would do something to relieve the financial distress of many businesses and many millions of people on unemployment. He’d sign a bunch bills but not a single omnibus bill. Pelosi will have none of that. But Trump’s initial gambit—re-elect me, and I’ll reward you—is but another in an endless string of evidences of Trump’s ego-driven policies. Suddenly, relief for millions depended upon doing his bidding. It’s all “me,” and none of “thee.” In the same everlasting vein, Trump has refused CDC’s help in doing the contact tracing that should be done in connection with the Trumpet’s adventure with Covid-19. The White House says it has completed "all contact tracing" for positive Covid-19 cases among its ranks, but given the confusing and sometimes contradictory information released by the administration about the recent outbreak, doubt remains. Moreover, White House staff continues to report positive results in testing. So—once again, the Trumpet himself is the sole measure of policy and practice. To do a thorough job of contact tracing, Trump would have to tell the world when he last tested negative before testing positive. And he won’t let us know that much about his bout with the disease: it might affect the way people vote, and his own re-election is paramount to all other considerations. It’s all “me,” and none of “thee.”

White Supremacist. I asserted last time that the Trumpet had declared opposition to White supremacy at times during his presidency, but I failed to cite the times. So, to make up for that oversight, I’ll do it here. MSN.com remembers that two days after the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia—where, a couple days earlier, Trump had declared there were “very fine people on both sides”—Trump issued a statement condemning racism, specifically “the KKK, neo-Nazis, White supremacists and other hate groups that are repugnant to everything we hold dear as Americans.” And then, following mass shootings in Ohio and Texas in August 2019, Trump in prepared remarks said that “in one voice, our nation must condemn racism, bigotry and White supremacy. These sinister ideologies must be defeated. Hate has no place in America.” But Trump’s record is less declarative. He has been criticized for not being as forceful or persistent in condemning White supremacy as he has been about terrorism by Islamic extremists or crime by undocumented immigrants, and he has himself used dog whistle racist rhetoric. Still, we have two quotations definitely condemning White supremacy. So why is he so seemingly reluctant to repeat those sentiments on other occasions—like during the debate with Biden? Probably because he knows that White supremacists don’t take his condemnatory comments seriously: they know he must, on occasion, say such things. But they know that, secretly, he’s on their side. Trump just doesn’t want to remind these groups of his previous declarations against them. Why stir them up when both he and they are in agreement on so many issues? Why risk losing their support at the polls when it will count? So he avoids repeating his condemnations.

Trumpetoons. And now, as usual, we take

a look at how the nation’s editoonists are depicting the Trumpet. We begin with

magazine covers. Trump winds up on a lot of magazine covers because he’s Prez.

But some of the covers are more like editorial cartoons than they are old

fashioned cover portraits. Take, for instance, a recent issue of Time, which

shows, at the left, the Trumpet up to his neck in water, surrounded by the

emblem of the coronavirus. But

instead of draining the swamp, he has been slowly immersed in it. The other

cover image we’ve posted before. And it is a continuation of the underwater

image launched in previous covers. The Week magazine has the most fun with the Trumpet because the magazine’s cover is usually, by deliberate design, a political cartoon, and we have two stunning examples of that practice in our next visual aid.The cover cartoon on the left celebrates the Trumpet’s tax returns; on the right, the consequences to American institutions of four years of Trump. The

Nation gets into the act on our next display, which shows a cartoony

Trumpet holding on tightly to the Presidential Podium. We’ve added a current

version of a Trump Gold Coin (a souvenir no one should be without) and, at the

right, a portrait of the The

latest of Mitch’s adventures concerns the Covid-19 relief bill being negotiated

between Nancy Pelosi and the White House. Trump wants a deal before the

Election (or not, see The Election above), but Mitch is against it. A deal, he

warns, would divide the Republican Notice that Mitch said nothing about the merits (or lack thereof) of the bill itself. He is concerned only about dividing the Republican Senate. Why is that his overriding preoccupation? Because of the Republican senators are divided, they are no longer a solid majority in the Senate, and if the Republicans are not a solid majority, Mitch loses his power. His power depends entirely upon his ability to keep the Republican senators all together in one solid group —a group that, if solid, outnumbers the Democrats and thereby secures his power as majority leader. Just another power-mad politician. And what does Mitch want to do with all this power? Does he have a pet project or a cause? No. He has never used his power for anything except to maintain his grip on it. Neither heinous nor humanitarian concern animates him. Just having power. That’s it. As a matter of record, Mitch has never sponsored any legislation. The closest he’s come was when he attacked a bill that sought to limit campaign spending. And since his election has always depended upon spending vast amounts of money, he was, of course, against that bill. I attached a photo of Mitch smiling idiotically because we so seldom see him joyful. And then, just for the pure fun of it, I’ve posted various photographs of the Trumpet in various stages of array and disarray, concluding with examples of the caricatural efforts of a couple cartoonists who are not editorial cartoonists.

AND NOW, WE GET TO TRUMPTOONS, beginning with a charming full-page comic strip by Peter Kuper, who is invoking Winsor McCay’s famous Little Sammy Sneeze series from circa 1906. In every one of McCay’s Sammy Sneeze strips, the kid, after several panels of wheezing and gasping, sneezes—at such velocity and force that he destroys whatever is around him. We’ve included a couple McCay examples so that your appreciation of Kuper’s ingenuity can be properly appreciated.

As is our custom, we divide Trumperies into two groupings: first, the editoons that depict the Trumpet as he sees himself (huge, of course); second, the cartoons that portray him as he is. These are cartoons about personality rather than issues. We

begin, then, with Ed Wexler’s cartoon echoing R. Crumb’s emblematic

“keep on truckin’” image, quoting the Prez’s assessment of the pandemic and its

impact on American life—just the sort of carefree attitude that the Trumpet

arrays himself with. Finally, at the lower left, Walt Handelsman’s imagery is all in Dr. Fauci’s speech balloon, the words of which have been altered to flatter the Trumpet with Trump standing by, approvingly. And that’s precisely what happened with a Trump campaign ad that quoted Fauci. The ad proclaims that the country is “recovering” from coronavirus, after Trump “tackled the virus head-on, as leaders should.” To buttress this laughable lie, said Greg Sargent in the Washington Post, the ad quotes Fauci saying: “I can’t imagine that anybody could be doing more.” Fauci did indeed say that—but he was talking about “the efforts of federal public health officials”—not Trump. It is astonishing to me that Trump would promote himself with such a stupifying falsehood—tackling the virus head-on, as leaders should— which denies his well-known history of failure in meeting the challenges of the pandemic. A stupendous, colossal, towering lie, the alleged truth of which is easily disproven. And that Trump thinks he can get away with it—that vast numbers of American voters will believe it—is even more amazing. As Sargent says: “The staggering dishonesty on display here should only serve as a reminder of [the actual] history.” It should also serve as a lasting portrait of the Trumpet in all his misbegotten self-proclaimed glory. Our

next display ridicules the Trumpet in ways he would not approve of. Bill

Bramhall’s picture of an enlarged Trump, whose bulk dwarfs the White House,

shows that he has “grown in office.” But that’s not all. In the cartoon, Trump

has not just grown large: he has grown so large that he overwhelms the White

House. The office is now effectively Trump. And to be Trump, it must

perforce cease to be the White House and whatever that building embodies of

American democratic tradition. Next, John Darkow’s image strips the facade from Trump. That’s Uncle Sam walking through the doorway to discover, to his astonishment, that the building (labeled Trump and Trump Tower) is wholly fraudulent. At the lower right, John Danziger shows Uncle Sam on the verge of the Election, ready to cut the chord that binds him to the Trump hot air balloon. And then Darrin Bell shows us the bigot-ridden megaphone used to promote the Trumpet. The settings are “low” (subtle dog-whistle), “medium” (I’ll keep them out of your suburb), and “high” (they’re coming for your daughter). The brand on the megaphone is four T’s (the Trumpet times four), but the arrangement of the letters outlines a swastika. And the hand holding the megaphone has claws. Another Trumpery observation comes from editoonist David Horsey, who has a Trump advisor telling the Prez that it is a mistake to encourage people to vote twice because “voting twice is a felon.” To which the Trumpet says: “I’ll pardon them.” No image: the words are enough. In

the next visual aid, Tom Toles’ imagery plays with the old fairy tale

about princes and frogs, and the kissing of which turns which into what. In

this case, the finishing note is sounded by the Trump image: a “toady” is a

sycophant, and Trump’s verbiage works in two directions: it describes Attorney

General William Barr. And it also sheds revealing light on the Prez, who

expects to be surrounded by sycophants. Kevin “Kal” Kalaugher’s picture of a packed court refers to the court of a monarch, not the court of justices. And this image crams lots of sycophants into Trump’s court. Next, Toles takes two panels to show how Trump’s government runs: in this diagram, legislation begins in the Trump Hotel and its success depends upon how much the proposer of the legislation spends at Trump’s hotel in downtown Washington. And then at the lower left, Kal is back with an image of Uncle Sam wondering where the U.S.’s “high standing” as an inspirational democracy has fallen. The Statue of Liberty helps him look, and the picture tells us that Trump’s big mouth has a lot to do with the fall. That, perhaps, is enough scalawaggery for the nonce. Onward to the rest of our editoon posting.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy

JUST FINISHED WATCHING the second Presidential Debate, Thursday, October 22. And at the moment, the prospect of having many editoons on the Debate in this opus seems remote. We have a posting imperative to obey (get it up in the digital ether as soon as we can; it’s been a month since the last posting). And most editoonists are finished for the week and won’t have any fresh published cartoon response to the Debate until Tuesday (their deadline, Monday), by which time, we hope to have wrapped up this posting. So we’re left, alas, with my own verbal response and assessment of the event. Mostly. Not many pictures. (And yet....) (... before we actually nailed this one down, we found a few, which we’re posting below.) First, it was a much better debate. Actual issues were discussed. Not in specific terms, alas. But the candidates talked about the issues and gave their opinions about them. And we got a chance to hear them and compare their views. All that was made possible by a somewhat better behaved Trump, who, instead of interrupting Biden, restricted himself to talking over the moderator, NBC’s Kirsten Welker, whenever she wanted to move on to a different topic or question. But the issues Trump discussed were not the same as those discussed by Biden. Trump’s issues all took place in a fantasy world he’s constructed over the years. As one of the pundits said afterwards, Trumped lied a lot and he made stuff up. He’s been doing that for four years, and are we any better off? Not likely. Welker did a pretty good job keeping the event on track—despite Trump’s failure to respond promptly to her urging to move on to the next question. He always wanted to respond to whatever Biden had just said even if it wasn’t his turn anymore. He just kept talking about his imaginary kingdom. But she would eventually outshout Trump and move on. (Well, she didn’t shout; but she kept on, persisting, until he shut up.) Many early reports on the event gave her higher marks than either Trump or Biden. But Biden did a good job, too. He didn’t allow himself to get pissed off at Trump. He grinned at every fantasy his opponent trumped up to ruin him. And Trump kept needling him—why didn’t he do all the stuff he’s now proposing when he was vice president? And—you’ve been in Congress and our government for 47 years, why didn’t you accomplish all these things over that period? Asked that same question about something Trump alleged Biden and Obama should have done—why didn’t you...? —Biden resorted, finally, to a blunt truth: “Republican Congress.” End of debate. Despite a cramping timetable, we have a few editoon responses to discuss. In

our first visual aid, R.J. Matson shows how Trump’s twitterpated

reaction to the “new rules” would frustrate the “mute mic” that will otherwise

stiffle him during Biden’s responses to the introductory questions on each of

the debate topics. That, of course, did not happen: no bluebirds hovered over

the event. But Trump doubtless wishes they had been permitted. Next around the clock, Steve Breen offers an image that characterizes Trump’s usual tactic in debates: attack your opponent (and ignore the question). But that was more Trump’s behavior in the first Presidential Debate than in this one. Matt Wuerker’s image presents the Trumpet as master of all he surveys—but what he surveys is not this world; he has his own private fantasy planet. And Henry Payne, a devout Republicon, conjures up an image of the debate as a wrestling match with Trump flinging his hapless opponent all around the ring. Most observers, however, while granting that the Trumpet was better behaved this time, don’t believe he won. Payne’s imagery is as fanciful as Trump’s world. In

our next exhibit, we join editoonists in pondering other recent developments,

but we begin with one last look at the Debate, this one by Mike Luckovich who

shows the two candidates saying what they’ve said before albeit with somewhat

different implications or purposes. Next is Dave Whamond’s imagery for the Trumpet’s persistent chant “we’re rounding the corner” in the fight against coronavirus. In short, no fight at all: rounding the corner of a mortuary and heading for the entrance is a long parade of hearses. The picture gives Trump’s words a different meaning, one closer to the truth than his perpetual lie. Just the day before we wrapped up this opus, the appointment of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court was confirmed by a senate vote with all Republicons voting for her (and almost no one else—certainly no Democrats). David Fitzsimmons’ cartoon is almost entirely verbal: seizing on the philosophy of originalism that Barrett swears by (read the Constitution as the Founders would), Fitz extends the logic. And with that, he demonstrates just how wrong—how out of step, how backward and out of time—the originalist is. Monte Wolverton makes his point by blending words and picture: his picture of the Supreme Court building shows it “listing.” “Starboard” is on the right as one looks forward to the front end of a ship. But “listing” is as significant to the meaning of this editoon as the Court’s predicable rightward tilt: it’s nearly impossible to steer a ship that’s listing. The implication, then, is that the Supreme Court will not make much progress in any direction, starboard or port. (But what progress it is able to make will be towards the right.) Colorado’s senior senator, Michael Bennet, made a longish call-to-arms speech about the confirmation of Judge Barrett. Nothing much against the Judge. Bennet talks mostly about the flaws in the system and how democracy seems to be deteriorating. We’ve posted an excerpt in our Onward, the Spreading Punditry segment. And now, we’ll go beyond the Debate and Barrett, the most recent comment-worthy political events of the last month, and take up various other matters as illuminated by the nation’s editoonists. Or, rather, we’ll take up their illuminations. Forthwith.

THE

DREADED PROGRESS of Covid-19 has haunted every one of the past eight months,

and the failure of our national government to address this national issue is a

disgrace and a crime, both of which are correctly attributed to the Trumpet’s

ineptitude or indifference. The most compelling image of recent weeks, however,

is a photograph not a cartoon—20,000 empty chairs, a mere fraction of the

pandemic dead, on the lawn facing the White House. Below that haunting image is another haunting image: Mike Luckovich’s picture of the presidential desk and chair in the Oval Office. The sign on the chair—that Trump “slept” there—correctly implies that he wasn’t paying attention to the pandemic and his inattention resulted in the 200,000 deaths referred to in the memo on the desk. The

plague continues to engage the attention and imagination of editoonists. At the

upper left of our next array, Steve Sack uses two panels to condemn the

Trumpet’s campaign maneuvers, all of which are accomplished without masks or

social distancing—the “something” that the observer in the second panel draws

our attention to. Walt Handelsman is next with a compelling visual

metaphor for Trump’s phoney reassuring message that the pandemic is almost

over: we’re not turning a corner; we’re about to crash. Rob Rogers supplies an image of our Prez uttering his famously ridiculed “it is what it is” remark—while standing on a pile of skulls representing the Covid-19 deaths. The image conjures up recollections of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, who, while wandering a cemetery, comes upon the skull of the king’s late jester, picks it up, looks at it as Trump does here, and says, “Alas, poor Yorick: I knew him well.” Trump, however, knew none of the dead. The irony is doubtless deliberate. (Or if not, it should be, delicious as it is.) Scott Stantis shows us where the Trumpet gets his medical advice about Covid-19—another of “Don’s home cures,” the beneficial effects of light, comes right out of his ass. Lovely image. Recording

attitudes and events associated with the pandemic is without question the big

preoccupation of the last month—of the last six months. And our next visual aid

shows editoonists up to the task of commenting on the passing scene even as

they have for many previous months. Next around the clock, Mike Smith takes two panels to reveal the true nature of our Prez’s concern about the Covid-19 dead. Below Smith, Joe Heller shows one of those independent “rights” advocates discarding his mask, prompting sarcastic comment by two bystanders who observe his action. And in the next editoon, Heller anticipates the haul this Hallowe’en—all the goodies associated with preventing the spread of the disease. Not

that we can’t have a little fun with the pandemic and mask-wearing and the

lock-down generally. We can. And we can without lessening the import and its

impact on civilization. I can’t read the signature on our first example of

comedy in the midst of Covid-19, but it proves that mask-wearing can inspire

laughter. At the lower left, Dave Granlund’s imagery contradicts the verbiage issuing from the White House (aka, the Trumpet). Trump emerged victorious from his encounter with the disease because he had legions of medical personnel attending him—and semi-trailer trucks loaded with new medical treatments. Hardly the experience of the ordinary citizen. Trump’s

subsequent behavior—removing his mask with a flourish of defiance when he

returned to the White House and going to rallies that encouraged thousands of

people to mingle without masks or social distancing—has apparently stimulated

an up-tick in numbers of infected people, including White House staff, who, as Steve

Sack shows us at the upper left of our next display, are tested going to

work and upon leaving the building, when they are now infected. Thanks to the

Trumpet. Despite all of this, Trump and his avid supporters clamor for the country to open up again—open the bars, the restaurants, schools, everything. Sack’s visual metaphor of a skeletal Death’s Head representing a “second wave” of infection resulting from opening up again argues against relaxing the lock-down. Mike Smith deals with opening up schools again, a thorny proposition at best. Remote schooling is not as effective as in-person education. But opening up in-person schooling risks infecting teachers and students. Keeping kids at home prevents parents from returning to work and, thereby, helping to revive the economy. Smith’s editoon gives us a little laugh but scarcely takes sides on the matter. Still, we need to laugh a little, too. Walt Handelsman offers a pictorial analysis of the gradual return to normal tactic. Moving through three phases, we end at Phase Three, which is that familiar visual conundrum, more illusion than fact. And now, we need to take a break from all this serious visual lingo.

************************* AND SO let’s do. With a few pictures that either puzzle or amuse or both.

************************

BACK

TO WORK. In our first visual metaphor, Lisa Benson comments on the state