|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 400 (February 1, 2020): With this posting, our 400th, we have arrived at a big, fat round number towards which we’ve been trending for over 20 years. But it’s never been a goal. We’ve never been aiming for it. We just kept plugging along until we finally arrived at it, a milestone. And we pass it just as we embark upon another year, 2020, a fresh beginning with the dawn of a new decade. Or does Opus 400 come at the end of a decade? At year’s end, all the media were celebrating the end of a decade as 2019 drew to a close. But decades don’t end with number nines; they end with zeroes. The first decade is numbered 1 to 10. A decade. So the end of 2019 does not mark the end of a decade, popular commentators to the contrary notwithstanding (and no matter what various of the ensuing reports claim). We won’t get to the end of a decade until a year from now. At the same time, we’ll start off on a new decade with 2021. Meanwhile, here at Rancid Raves, we mark the end of the fourth 100 postings. But other than being a nice round number (with the persistence it signals), Opus 400 is no different than the 399 postings that preceded it. We offer this time the same array of reviews and news that has always inspired us to continue. Our major focus this time is on the cartoons of The New Yorker. In one essay, we look at the revived Cartoon Issue, returning after nine silent years, and compare it to its predecessor which debuted in 1997; the other essay discusses the present cartoon editor, Emma Allen, her lack of preparation for her role and the kinds of cartoons she favors and how that is destroying the last bastion of single-panel cartooning in the country. We also review more than half-a-dozen books, including a couple of disgraceful graphic novels. In order to assist you in wading through all this plethora, we’re listing Opus 400's contents below so you can pick and choose which items you want to spend time on. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order, beginning with the news of the day—:

NOUS R US Decade’s Top Five Censored Comicbooks Politics in Comicbooks Biggest News of the Year: Children’s Graphic Novels Fake Graphic Novels Person of the Decade Comic Parody of the Constitution Teaching Comics in Schools and Colleges Far Side on the Web At Last Is the Fabled Skippy Fight Over? Abe Martin Recognition Jerry Craft Wins Newbery Nancy Drew Dead? No Best of the West Award this Year Wordless Book Celebrates the Daily Newspaper

ODDS & ADDENDA Non Sequitur Restored, Jim Morin Retires Yellow Kid Comicbook Dogpatch To Be Sold Deputy Sheriff Hulk Historic Persons in New Graphic Novels Series Women’s Stories in Graphic Novels Graphic Novel Library from IDW and Smithsonian

THE NEW YORKER’S CARTOON ISSUE A Return After Nine Years

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Mad No.11

TRUMPERIES Antics and Idiocies of the White House Buffoon EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy The Trial

THE FROTH ESTATE Trump’s Attack on the Press

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL What’s Odd and Vulgar in the Funnies

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Books In Need of Good Reviews Mauldin’s Willie & Joe: The World War II Years

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Wonder Woman, Popeye

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews & Coming Attractions Barney Google for President The Complete Pogo, Volume 6

BOOK REVIEWS Longer & Opinionated Mac Raboy: Master of the Comics “A Very Stable Genius” @realDonaldTrump The Art of Nothing: Patrick McDonnell and Mutts

BOTTOM LINERS Emma Allen and the Deterioration of the New Yorker Cartoon

GRAPHIC NOVEL REVIEW The Mueller Report

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY The Democrats

PASSIN’ THROUGH Steve Stiles

Yearly Report: For the Record

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

THE DECADE’S TOP FIVE CENSORED COMICS By Patricia Mastricolo at Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (CBLDF) As 2019 came to a close, we looked back at the past decade of comics censorship. In the last ten years [2010-2019], comics have experienced a meteoric rise in popularity, unprecedented inclusion in schools, and a subsequent increase of censorship attempts. A look at the annual lists produced by the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom of the most frequently challenged and banned books demonstrates this well. Before 2010 it was rare for a comic to appear on the list, but since then, the quantity of challenges and bans to comics have consistently climbed, due in part to their increased inclusion in academic settings. With more challenges comes more opportunities for CBLDF to fight for free expression and the inclusion of these important graphic novels. So take a look at these five comics that not only changed the medium, but continue to demonstrate the importance of free expression on a regular basis. Two of CBLDF’s brightest victories this year both involve Alison Bechdel’s game-changing graphic memoir Fun Home, and the state of New Jersey. Following 2018’s very public challenge to Fun Home in New Jersey, two more high schools quietly removed the comic from their library shelves without following proper policies. CBLDF and National Coalition Against Censorship went to bat immediately for the important memoir, and eventually the schools relented and returned it to the shelves. Then, a lawsuit was brought against school district employees in Watchung Hills about the inclusion of Bechdel’s Fun Home exactly a year after the graphic memoir had been retained in 2018, in spite of parental challenges to the comic. ... Earlier this year, Nonprofit Books to Prisoners (B2P) released a list on Twitter highlighting the vast illogical nightmare that was the Kansas Department of Corrections (KDOC) log of censored books. The list demonstrated that for decades KDOC has been infringing on the First Amendment rights of its inmates by arbitrarily limiting their access to the “marketplace of ideas.” Michelle Dillon, an organizer at Books to Prisoners tweeted the list, calling the list “unbelievable” and pointing to the fact that Kansas has 10,000 incarcerated individuals, and more than 7,000 books have been banned. Among them is Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons critical darling, Watchmen. In 2017, Fun Home and Art Spiegelman’s Maus were both listed in a widely circulated piece advocating against comics in classrooms as they “advance political agendas.” This article came from a think tank and was published in a popular conservative paper, and press like this often effects teachers inclusion of comics in curriculum, causing a pervasive type of self-censorship that is almost impossible to combat. Maus had popped up a couple years earlier in 2015, when, despite a lack of formal complaints, several major bookstore chains in Russia began pulling Maus off shelves and internet sites because of the swastika on the cover. According to a then-recent law, all Nazi propaganda was forbidden from being displayed in retail shops, including on the cover of a book whose overall message is completely anti-Nazi. It came as a shock to many that the book would become the victim of a law designed to separate modern Russia from the history of Nazism inflicted upon the world during World War II. Spiegelman spoke out about the larger implications of these reactionary efforts to purge a portion of Russian history from the consumer marketplace: “I don’t think Maus was the intended target for this, obviously. But I think [the law] had an intentional effect of squelching freedom of expression in Russia. The whole goal seems to make anybody in the expression business skittish … “A tip of the hat for Victory Day and a middle finger for trying to squelch expression.”

ON JUNE 2015, Brian K. Vaughn’s Y: The Last Man was one of four graphic novels that a 20-year-old college student and her parents said should be “eradicated from the system” at Crafton Hills College in Yucaipa, California. After completing an English course on graphic novels, Tara Shultz publicly raised objections to Persepolis, Fun Home, Y: The Last Man Vol. 1, and The Sandman Vol. 2: The Doll’s House as “pornography” and “garbage,” saying that Associate Professor Ryan Bartlett “should have stood up the first day of class and warned us.” Crafton Hills administrators responded with a strong statement in support of academic freedom, although President Cheryl Marshall did note that future syllabi for the graphic novel course will include a disclaimer “so students have a better understanding of the course content.” CBLDF joined the National Coalition Against Censorship to protest this attack on academic freedom, and the district backed away from the proposed disclaimer plan. The previous year, marked Brian K.Vaughan’s and Fiona Staples’ epic sci-fi adventure Saga’s first year on the ALA’s 2014 Top Ten List of Frequently Challenged Books. In 2012, Saga was released and it became immediately apparent that this comic was redefining genres and comics with each monthly installment. It’s over-arching themes of diversity, inclusion, family, and love resonated with new and veteran comics fans alike. With the immediate critical success, it is no wonder it quickly became one of the most challenged comics in just two years. One of the first years a comic appeared on the American Library Association’s List of Most Frequently Banned and Challenged Books, in 2013, out of 307 challenges recorded by the Office for Intellectual Freedom, comics series Bone by Jeff Smith ranked 10th for political viewpoint, racism, violence. Smith responded to this by saying: “I learned this weekend that Bone has been challenged on the basis of ‘political viewpoint, racism and violence.’ I have no idea what book these people read. After fielding these and other charges for a while now, I’m starting to think such outrageous accusations (really, racism?) say more about the people who make them than about the books themselves.” This wasn’t the first controversy Bone faced. In 2012 Bone was relocated from a Texas elementary school to a junior high school in the same district because of another “unsuited for age group” complaint. Finally in 2013 it was challenged twice more in Texas schools, at Colleyville Elementary School in Colleyville and Whitley Road Elementary in Watauga. In the latter case the unidentified complainant said that Vol. 2, The Great Cow Race, was “politically, racially, or socially offensive,” while the parent in Colleyville complained of “violence or horror” in the entire series. Both school districts reviewed the books and opted to keep them where they were.

POLITICS IN COMICBOOKS The past year has shown a pattern of writers giving overt voice to their political opinions through superhero comics, or for controversies where they were prevented from doing so says Tom Speelman at polygon.com. Marvel and DC, the most visible publishers, are at the center of the ideological debate. Based on the decision-making, the two companies appear to have distinct approaches to talking politics in their paperbacks. In DC’s Lois Lane No.1, our heroine at a press conference faces off with a Trumpian press secretary and mostly wins. Says Speelman: “What all this says to me is that, when it comes to certain creators and certain books, DC Comics is happy to allow political subtext become text. This sits in contrast to Marvel Comics.” Twice in 2019, Marvel found itself embroiled in political controversies. The first came last August, when Maus author and Pulitzer Prize-winner Art Spiegelman went public with the news that his introduction to a limited edition hardcover of Golden Age Marvel comics published by the Folio Society was refused because he made a snide remark likening the Red Skull to the Orange Skull (see Opus 386B). That same month, in the lead up to Marvel Comics No.1000, Marvel altered the work of Mark Waid, a long-time writer for the publisher. Waid had characterized American values as a little shy of satisfactory execution (see Opus 398) but still functional. Controversy over “politics in comics” — or lack thereof — isn’t a new phenomenon by any means, Speelman goes on. For one memorable example, in 2009’s Action Comics No.900, DC film screenwriter David S. Goyer had Superman renounce his American citizenship. After being admonished by the US government for joining in a nonviolent protest in Iran, given that he is, to them, a symbol of American policy, the Man of Steel said that “Truth, justice and the American Way [...] it’s not enough anymore.” And this wasn’t Goyer turning Superman into a political figure: the character has been that way since the very beginning. In the first issue of Action Comics, published in 1938, Superman beats up a wife-beater, saves an innocent woman from execution, and forces a corrupt senator to confess that he’d stirred up a South American war because he was in bed with the arms industry. But DC isn’t alone in taking political stances despite Speelman’s seeming contention that it is. Yes, Marvel hesitated over Spiegelman’s Orange Skull and Waid’s poetic view. But Marvel isn’t always hesitant. If we return to1961 and the dawn of the Marvel Age of Comics with Fantastic Four No.1 by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, we encounter a flashback to the origins of the superteam in which Ben Grimm angrily points out to Reed Richards that he has no idea what the cosmic rays of space could do to them. To which Sue Storm melodramatically replies, “Ben, we’ve got to take that chance ... unless we want the Commies to beat us to it!” Comics have always gone there, both DC and Marvel. Balking at a few political references in the name of preserving corporate standards sits in contrast to the history of superhero comics, an industry that came to life thanks to two Jewish kids from Cleveland in the ’30s. When the Big Two lean into the political aspects of their creation instead of running away, says Speelman, “we all benefit.”

BIGGEST NEWS OF THE YEAR: CHILDREN’S GRAPHIC NOVELS And —Person of the Decade From the Beat—: ● Biggest Story of 2019: The massive explosion in children’s graphic novels across the book publishing industry ● What will be the biggest story in comics in 2020? The trade war with China, and how it affects the massive explosion in children’s graphic novels across the book publishing industry ● The Beat’s Person or Comic of the Decade: Tom Spurgeon ● The Person of the Year: While Spurgeon was much on the minds of people, 2019 was without a shred of a hint of a doubt the year of the kids comic, and no one triumphed like Dav Pilkey, who had not one but TWO behemoth sellers. Pilkey had a year that only a tiny handful of authors at their very peak could match. Dog Man: Fetch 22 had a five million copy first printing, and sold more than 500,000 copies in a few weeks; his previous book, Dog Man: For Whom the Ball Rolls – which only came out in August – has sold more than a million copies, according to Bookscan and was the third-biggest selling book of any kind in 2019. Since its debut, the eight Dog Man books have sold more than 26 million copies, and have excited kids reading like nothing else happening. Pilkey was also named Publishers Weekly’s Person of the Year, and he shows no signs of slowing down. ● Two syndicated comic strips have retired so their creators can write children’s books. After a little more than 14 years, Norm Feuti ended his comic strip, Retail. The final installment will run on Sunday, February 23, 2020. Feuti plans to pursue a slightly different career creating children’s books. Must be something magic (or tragic) about 14 years: Terri Libenson bid her strip, The Pajama Diaries, farewell on January 4 after a run of similar length. She will focus on her series Emmie & Friends for middle grade readers.

But Not All Graphic Novels Are Graphic Novels The invention of graphic novels as a genre has made comicbooks respectable. But in the dash to cash in on this new publishing opportunity, publishers are producing lots of fake “graphic novels” that are an offense to the medium. Many are merely picture books in which the pictures just illustrate a text that carries the narrative perfectly well without pictures. Pictures in these “fake” graphic novels perform no narrative role. For a couple outrageous examples, see the Mueller Report graphic novels reviewed in our Long Form Paginated Cartoon Strips department ’way down the scroll.

SIKORYAK’S COMIC PARODY OF THE CONSTITUTION R. Sikoryak, who has made a career out of mimicking the styles of other cartoonists when he tackles literary classics or other nearly well-known works, is presently at work on what may become his magnus opus: he’s turning the U.S. Constitution into a comic. “I’m not editing the text in any way,” he said, “—I’m reproducing it verbatim, but each of the comic’s hundred pages is drawn in a different style, so I’m always looking for new connections between the visuals and the words. And I’m trying to represent a cross-section of American comics styles from the past century, which has led to a lot of research—even for me. I’m taking the content a lot more seriously than when I adapted the iTunes terms and conditions into a graphic novel.”

TEACHING COMICS IN SCHOOLS AND COLLEGES In the photographs

posted just at the elbow of your eye, poached from a publication of the

National Council of Teachers of English, we have a phalanx of nine English

teachers who have donned the costumes of their favorite superheroes in order to

celebrate the success of superhero comicbooks in revitalizing their subject. The English classroom in high school and college has almost always been plagued by “the soul-sucking vortex of student disinterest.” Who, after all, finds grammar and the Elizabethan language of Shakespeare at all interesting let alone gripping? Almost no one except teachers of English. So this gaggle of English teachers, all of whom have been fans of comics in an earlier life, found that they could revive that interest and put it to pedagogical use in the classroom. One of them started it off by offering a class in comicbooks at Indiana University of Pennsylvania in 2001. The timing was propitious: Michael Chabon’s novel about the early days of the comicbook industry, The Amazing Adventures of Cavalier and Clay, had just won the Pulitzer Prize, and because the novel was a serious literary achievement, it opened the door for the genre to be taken more seriously. And to be studied! Students perked up. They took interest in English courses that had previously bored the shit out of them. But there is a hidden downside. Bringing comicbooks into the classroom signals an admission of defeat by English teachers. Teachers of English tend to be introspective personalities, studious, interested in punctuation, subject-verb agreement, Chaucer and Shakespearian blank verse. The successful classroom teacher in public schools and colleges has always been as much performer as scholar: you gotta keep ’em awake, and you do that with jokes—a little song, a little dance, a little seltzer down your pants. If you can’t do that stuff—if you’re an introspective personality, not a performer— then, in desperation, you scratch around for something that will keep students entertained. Ah, ha—graphic novels! Comic books! Who knows what’s next. Studying movies?

**** NOT EVERYONE AGREES that using superhero comicbooks to teach Shakespeare or composition is a good thing. Ryan Craig at forbes.com for one. Says he: “In attempting to give students the superheroes we think they want—likely in a misguided effort to increase or at least sustain enrollment— we’re leading them down a primrose path of suboptimal skill development and under employment.” Moreover, such practices lead to “the legitimization of infantilization and cultural deterioration that may also contribute to political extremism.” Superheroes, Craig maintains, are for grade school. In middle school, we graduate to sports heroes. In high school, romantic heroes. By college, we should have intellectual heroes “who demonstrate remarkable creativity and original thinking.” To chase after student engagement by offering them course work incorporating superhero comicbooks delays maturation. We need intellectual heroes, Craig says. Heroes we can grow into, I say.

FAR SIDE ON THE WEB AT LAST After decades of eschewing the internet, creator Gary Larson is at last releasing daily batches of his classic strip, The Far Side, reports Dan Schindel at hyperallergic.com. In the decades since the strip ended its 15-year run in 1995, Larson has been highly reticent to put any of it online and has been outright hostile to people uploading his comics. He was insistent that the only way to read the comic would be either through the books or whatever newspaper clippings fans had preserved. But on Tuesday, December 17, a batch of classic strips was posted on the official Far Side site — the first of many such updates. Going forward, The Far Side will be posting a “Daily Dose” of different comics culled from throughout its run, as well as pairs of weekly collections of comics that share common themes. (One inaugural collection is “Hands Off My Bunsen Burner,” featuring comics about scientists at work.) There are also selections of Larson sketches available to peruse. New strips and other material will also be periodically appearing, which is certainly the most exciting prospect for fans of the comic. In a letter on the site, Larson explains two primary motivators for finally putting the strip online. First, he wants to take a new approach to corralling the sharing of his work on the internet: “Trying to exert some control over my cartoons has always been an uphill slog, and I’ve sometimes wondered if my absence from the web may have inadvertently fueled someone’s belief my cartoons were up for grabs. They’re not … So I’m hopeful this official website will help temper the impulses of the infringement-inclined.” The other is that the quality of web visuals has drastically increased since he initially dismissed it as a medium for his comics. (And indeed, the color comics posted so far look excellent on the site, far better than any fan scan, Schindel says.)

SKIPPY FIGHT MIGHT BE OVER If So, Too Bad Joan Tibbetts, 87, who as the administrator of the estate of her father, cartoonist Percy L. Crosby, fought a lifelong battle over the copyright and trademark name of his cartoon character Skippy, died October 26 at a hospice center in Severna Park, Maryland. The cause was lung cancer, a son, Waldo Tibbetts, told the Washington Post. Tibbetts was born Joan Crosby in Washington. Her father’s cartoon character Skippy was a fifth-grade schoolboy, whose adventures were featured in a popular eponymous comic strip from 1923 to 1945. In the 1930s, a peanut butter manufacturer adopted the name Skippy without permission from or compensation to Crosby. The graphic on the label of the peanut butter jars used a board fence upon which “Skippy” was lettered—an obvious steal from Crosby’s strip in which a board fence was almost a character. For decades, Tibbetts led the fight contesting the use of the name of her father’s creation. Some of the stages in the fight are detailed in Opuses 70, 136, 172, and 272. But you can get the whole story at once in Harv’s Hindsight for April 2004.

ABE MARTIN RECOGNITION

For the life story of Abe Martin (and Kin Hubbard) see Harv’s Hindsight for March 2013.

CRAFT WINS NEWBERY WITH NEW KID By Raina Telgemeier When Jerry Craft became the very first graphic novelist to receive a Newbery Medal, he shattered a glass ceiling for cartoonists, who have long been looked at as producing “lesser” literature than their prose-writing siblings. I am so proud of him. The January 27 announcement that the prestigious prize for American children’s literature will go to his New Kid, the story of a seventh-grader who doesn’t fit in at his mostly white private school, is a victory for Jerry and for the art form of comics. Jerry’s win (after many, many years of hard work) proves once and for all that comics and graphic novels are real books, real reading, and really and truly deserve shelf space front and center. It has been a joy to watch sequential art evolve and to see the warm reception graphic novels have received from young readers and awards committees alike! How joyous that when children read New Kid in decades to come, they will feel the tactile merit of the golden sticker on its cover. Telgemeier is the Eisner Award–winning author of the best-selling graphic novel Guts among others.

NANCY DREW DEAD? A new comicbook series from Dynamite Entertainment pictures the Hardy Boys standing over Nancy Drew’s grave. The beloved teen detective, who has survived countless scrapes, cliffhangers and close calls for 90 years, is dead — or so it seems, carefully notes Michael Levenson at nytimes.com — killed while pursuing a high-stakes investigation of organized crime. And it’s up to the Hardy Boys to solve the mystery of her murder. The forthcoming Nancy Drew & the Hardy Boys: The Death of Nancy Drew! hitting the stands in April, is intended to commemorate the publication in April 1930 of the first Nancy Drew book by putting a noirish spin on the classic tale of the roadster-driving, truth-seeking sleuth from River Heights. But the possibility that Nancy — whose pluck and valor have helped her triumph over villains since the Great Depression — was murdered has unsurprisingly drawn strong reactions, reports Milton Griepp at ICv2, both from those who are concerned about their beloved character disappearing to those who see the story as a diminishment of a strong female character in favor of the male characters, the Hardy brothers, who are tasked with solving Drew’s murder. Said Griepp: “Some criticism of the storyline uses the term ‘fridging,’ a term evolved from writer Gail Simone’s reaction to a 1994 story in which a female character was killed and stuffed in a refrigerator as a way to advance a male character’s storyline.” The Drew storyline, beyond the brief description in the original announcement, is not yet known, although writer Anthony Del Col promised "twists and turns that all fans— new and old— of Nancy, Frank and Joe [Hardy] will enjoy." But he was very surprised by the blowback, Levenson said. Del Col said he had envisioned the story as a continuation of a previous series he wrote for Dynamite in which Nancy and the Hardy brothers team up to solve the murder of the boys’ father, Fenton, a crime that the boys themselves stand accused of committing. As in that series, he said, the gritty settings and dark themes in the “The Death of Nancy Drew!” were inspired by the conventions of film noir. “What we tried to do is create one of the ultimate mysteries of Nancy Drew,” Del Col said. “How did she die? Who killed Nancy Drew?” Perhaps the bigger question on the minds of fans: Is she really dead? Del Col refused to say. The Nancy Drew character has been getting high visibility recently, driven by the new television series on the CW, which debuted in October. “We’ve had incredible success with Nancy Drew,” said Dynamite CEO Nick Barrucci of the property, “— not only through initial release as periodicals but then as the collections thorugh comic stores, bookstores, and libraries. And with the tv series doing so well, the awareness for Nancy is at an all-time high.” Nancy has captivated readers since she first sprang to life as the brainchild of Edward Stratemeyer, the head of a children’s literature syndicate who also created the Hardy Boys in 1927. Stratemeyer gave the plotlines for the first Nancy Drew stories to Mildred Wirt, a young newspaperwoman, who fleshed out the books, which were published under the pseudonym Carolyn Keene. Wirt, later Mildred Wirt Benson, wrote Nancy Drew books off and on for two decades. Fitnoot. Dynamite seems to be in the killing off fan favorites mode: Red Sonja is slated to die soon in a “companion limited series” about the Hyborean Age redhead.

NO MORE AWARD The Best of the West journalism awards program has discontinued the Editorial Cartooning category because of a lack of entries in recent years. Seems too bad. The entry fee is only $15 for 5 cartoons. Maybe the Best of the West isn’t the most prestigious award program on the planet, but it promotes interest in editooning and therefore ought to generate enthusiastic participation among the few editoonists still practicing their art. That’s about forty full-time staff editoonists on newspapers, plus former staffers who now are practicing freelancers. Both groups are eligible.

New Wordless Book Celebrates the Daily Newspaper The Paper is a wordless book, said Steven Heller at printing.com—“a tribute to the most important safeguard against tyranny we’ve got: journalists.” Heller quotes the book’s creator Christoph Niemann: “The series started when I was asked to do the daily drawings for the ‘A’ section of the New York Times (AD Andrew Sondern). I had done a lot of extra ideas, and even after we were done with the month I just kept going.” He published the book, designed by Ariane Spanier, through his publishing arm, Abstractometer Press. All proceeds go to Reporters Sans Frontieres (Reporters Without Borders). As Niemann writes: “The world is facing countless pressing issues. I don’t know how to solve them, but I’m convinced that in order to find out, we need a press that can ask the relevant questions, without fear of threats, persecution and violence. We need to protect reporters who take risks to shine light into the darkest corners of the world and bring us the truth about sensitive subjects involving our health, our safety and our geopolitical environment. RSF [has been] fighting for this since 1985.” To learn more and support them further, visit www. RSF.org.

ODDS & ADDENDA The Oregonian has restored Wiley Miller’s Non Sequitur; the paper was among those that cancelled the strip when Miller inadvertently buried a vulgarity in a Sunday strip. ... Editoonist Jim Morin has retired from the Miami Herald where he’d worked since 1978; his departure from the ranks of full-time staff editoonists reduces the number to 41-45 (depending upon how you count). ... ■ Writer and comics fan Chris Yambar has partnered with editoonist Randy Bish to bring the Mickey Dugan back to life in a comicbook, out in February. Dugan, you’ll remember (won’t you?) enjoyed a 4-year run in the 1890s as the Yellow Kid, often mistakenly dubbed the protagonist of the first comic strip. Yambar slyly observed: “Here’s a bit of timing — the Yellow Kid’s official 125th birthday comes in February. So here we go.” ■ The abandoned Dogpatch theme park in Arkansas will be sold at auction on March 3 if the current owners don't come up with $1,031,885 before then, reports the Akansas Democrat Gazette. Constructed in 1967 for $1.33 million (about $10 million in today's dollars), Dogpatch originally featured a trout farm, buggy and horseback rides, an apiary, Ozark arts and crafts, gift shops and entertainment by characters from Al Capp's Li'l Abner comic strip. Amusement rides were added later. ■ The Incredible Hulk’s Lou Ferrigno, 68, became a sheriff’s deputy in New Mexico’s Socorro County the week of January 13. Ferrigno has served in similar roles elsewhere: as a reserve sheriff’s deputy in Los Angles County and as a member f the volunteer sheriff’s posse in Maricopa County, Arizona. Officials say he will bring decades of law enforcement experience to the department and his presence will doubtless help in recruiting. ■ BOOM! Studios has announced Seen: True Stories of Marginalized Trailblazers, an all-new graphic novel series debuting in September 2020 from a group of acclaimed comics creators, including Birdie Willis, Rii Abrego, Anthony Oliveira, and Killian Ng. This new series illuminates the triumphs and struggles of important historical figures who aren’t found in traditional textbooks, but deserve to be remembered for their contributions to humanity and their inarguable strength and courage in the face of impossible odds. In the first graphic novel of the series, writer Jasmine Walls and artist Bex Glendining present the true story of Edmonia Lewis, the woman who changed America during the Civil War by becoming the first sculptor of African-American and Native American heritage to earn international acclaim. ■ Drawing Power: Women’s Stories of Sexual Violence, Harassment, and Survival, edited by Diane Noomin with an introduction by Roxane Gay, published by Abrams ComicArts, is a comics anthology featuring the work of more than 60 artists. Although the organization of Drawing Power was sparked by the #MeToo movement, it follows a diverse history of primarily women comic artists and authors realizing traumatic autobiography via graphic narrative, including Alison Bechdel, Marjane Satrapi, Ellen Forney, and Thi Bui. In Graphic Women: Life Narrative & Contemporary Comics (2010), Hilary L. Chute argues that comics and graphic novels are a particularly fruitful medium as an autobiographical model due to its dialectic visual-verbal form, which, by its very design, can be a powerful tool for self-representation and (re)imagining trauma. ■ IDW Publishing and the Smithsonian Institution have announced a multi-year global publishing program, which will create an unprecedented library of graphic novels built on the cultural and scientific knowledge of the world’s largest museum, educational, and research complex to launch in the fall of 2020. Among the planned product lines are: Time Trials, a middle-grade graphic novel series inspired by the National Museum of American History video series; original graphic novels focused on landmark events and individuals, in the tradition of IDW’s acclaimed March and They Called Us Enemy; coloring books in both the youth and adult categories.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO Stray paragraphs from a newsstory— It’s astonishing that humans are expected to make our way in the world with language alone. “To speak is an incomparable act / of faith,” the poet Craig Morgan Teicher has written. “What proof do we have / that when I say mouse, / you do not think / of a stop sign?”

THE NEW YORKER’S CARTOON ISSUE TWENTY-THREE YEARS AGO, The New Yorker, which has always depended upon cartoons for a healthy slice of its content, celebrated that aspect of its 94-year history by publishing a “cartoon issue” in December 1997. The Cartoon Issue was, initially—apparently—a success, and so the magazine published a second celebration a year later. And the Cartoon Issue was thus established as an annual venture. Alas, it didn’t last long. The Cartoon Issue began in 1997 and ended in 2011. But (hooray) the Cartoon Issue has been reincarnated at the instigation, doubtless, of the current cartoon editor, 30-year-old Emma Allen. The revived Cartoon Issue, Dated December 30, 2020, is 74 pages long and offers 63 cartoons, including a 10-page cartoon essay on “How To Draw A Horse,” probably the dullest 10 pages The New Yorker has ever published. Although a one-page feature entitled “Hammurabi’s Code of Manners”—a list with marginal doodles—is this issue’s close second. Taken together, these two features exemplify the editorial acumen of the current cartoon editor. Emma Allen’s professed fondness for the comic strip format yielded 16 pages in that manner. Two of those pages are entitled “Lines” and feature the daily doings of an African American woman, slice-of-life and otherwise pointless. Another three of those strip-format pages are about parenting, a thoughtful occasionally poignant venture. Then we have the “Horse” and “Hammurabi.” Two pages feature Edward Steed’s portraits of contributors, but the portraits do not seem to represent any aspect of any contributor’s personality or talent. Sort of pointless, in other words. Another page is devoted to biographical aspects of Roz Chast, accompanying a long text article on her life and art. Most of the single-panel cartoons are grouped under two headings: cartoonists’ favorite cartoons (15 cartoons) and non-cartoonists’ favorites (14). In other words, nearly half (29) of the cartoon content slipped in without embodying Emma Allen’s various preferential quirks. (For an examination of those, scroll down to Bottom Liners.) Hereabouts, we’ve posted examples of this Cartoon Issue’s offerings, plus the magazine’s cover.

In contrast, the 2019 issue’s predecessor in 1997 at 166 pages was 45% larger, and with 102 cartoons, it was 61% funnier. Most of the cartoons, 51, were scattered through the magazine. Some appeared under various headings: non-cartoonists’ favorites numbered 8; encores, 10; “Tomorrow’s Specials,” 12; Christmas, 6. And there was a section of both text and cartoons (6) on desert island cartoons.

Only 2 comic strips appeared in 1997: one, a single tier strip across the bottom of a page; and a 2-page appreciation of Charles Addams by Roz Chast. Like its predecessor, this year’s Cartoon Issue featured several text articles on or by cartoonists and on humorous topics. The longest article this year is about the life and career of Roz Chast. Another piece is about Wiley E. Coyote’s trial; the 1997 issue had a short piece entitled “Wile E. Cartoonist” about animator Chuck Jones, which ended by quoting Rudyard Kipling’s daughter, who said: “I hate Walter Disney.” And another article focused on early animation. Yet another essay this year, “Lost Art,” reprinted John Updike’s 1997 essay on his aborted career as a cartoonist, most of which happened while in college for the campus humor magazine. This essay, credited to the 1997 Cartoon Issue, is actually a chapter, “Cartoon Magic,” from Updike’s book, More Matter: Essays and Criticism. The 1997 Cartoon Issue had fewer prose pieces. In addition to the Updike article (which included 4 more cartoons than are used in the 2019 issue), there’s a long essay on Thomas Nast, “The Man Who Invented Santa Claus” (this issue came out just before Christmas), and Roger Angell’s memoir about cartoonists he came to know as a child; his mother was Katharine Angell/White, the magazine’s fiction editor, and his stepfather was humorist E.B. White, and there were cartoons all over his home, “with the captions typed on the back.” A long biography of William Hogarth finishes the inaugural Cartoon Issue, his standing in the art world lending status to this issue by reason of the cartoony nature of some of his works (“Rake’s Progress,” “Harlot’s Progress”). Born poor, Hogarth achieved success through his art. “There was a desperate edge to his will to succeed, and the upper classes, who were in any case suspicious of this man with a common touch, never forgave him for it.” In 1764 at the age of 67, Hogarth died suddenly, soon after boasting that he’d “eaten a pound of beef-steak for his dinner.” By

the last of the previous generation of Cartoon Issues (in October 2011), the

text pieces about cartooning and cartoonists had disappeared In a special “The Funnies” section, 8 pages were devoted to single-panel cartoons, 19 of them (one of which was picked up and rerun in the revival issue this year); the rest of the section was filled with comic strips—two-pages by Roz Chast, another two by Zachary Kanin, two more by B. Blitt, and another two by Mark Alan Stamaty (tiny cramped drawings in the panels). And two one-page strips. Six more single-panel cartoons were sprinkled throughout in the usual fashion; total, 25 cartoons. Altogether, a pretty poor showing for a “cartoon issue.” No wonder it was the last.

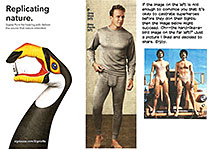

SO WHAT CAN WE SAY WE LEARN by comparing the two Cartoon Issues? This year’s Cartoon Issue copied some of its features from the 1997 issue—the Updike article, cartoonists’ and non-cartoonists’ favorite cartoons, and Wiley Coyote as an inspiration. Most of the cartoon content of the 1997 issue was selected by cartoon editor Bob Mankoff; most of this year’s cartoon content was selected by cartoonists and non-cartoonists picking their favorites. The cartoons picked by Emma Allen are mostly in comic strip form—and they include the absolutely vacuous “How To Draw A Horse” article, 10 pages of it, 14% of the entire magazine. Ghastly. Apart from Emma Allen’s dubious ability to pick funny cartoons, this issue also demonstrates her puerile cliche-ridden writing ability. She develops the conceit that the entire “Cartoon Department” was accidentally locked in the office during “the winter break.” “Finding ourselves trapped in here ... we banged on the doors and called for help, then collapsed onto the floor, weeping and rending our clothes. ... Finally, we decided to give the cocktail-party people what they deserve: a cartoon-takeover issue. ... “Read on. There’s some old stuff and some new stuff, all aimed at keeping you smiling into the New Year, which, we have on good authority, will be funnier than its predecessor.” So juvenile and feminine is this manifestation that I half expected to see little hearts dotting the i’s in her text. I have it “on good authority” that they were surgically removed before publication, weeping and rending their clothes as they went. If you have not yet become persuaded that I don’t like her editorial skills, you may be convinced by our Bottom Liners department this time; for which, scroll down. In short, by comparing the two issues, I reveal my strenuous bias in favor of Mankoff as cartoon editor. Mankoff is also a cartoonist, which gives him insight into the medium. Insight and enthusiasm. Emma Allen, I suspect, has neither. Picking cartoons for her is probably like doing embroidery: it keeps her fingers busy. For a final glimpse into the cartoon acumen displayed by each of the two cartoon editors, take another look at the covers of the two Cartoon Issues. Mankoff’s cover is a two-page fold-out. He judiciously selected representative examples of the work of New Yorker cartoonists and carefully arrayed them in a montage that suggested they were all assembled for a party. Mankoff’s array was an exhaustive attempt to represent all of the cartoonists whose cartoons appeared regularly in the magazine’s nine-decade history. (There were short text biographies in the “Contributors” section.) And Mankoff did the arraying himself and signed the work (lower right-hand corner). Emma Allen, on the other hand, left the design of the cover to the magazine’s art editor, Francoise Mouly, who picked R. Sikoryak to do the honors. Sikoryak has gained some notoriety in parodying other cartoonists by copying (exactly) their work in some foreign context. For his cover, Sikoryak copied (left to right) Saul Steinberg, George Booth (the dog), William Steig, Emily Flake, Edward Steed, and, of course, Roz Chast. (Of course.) He was shooting for “a mix of the classic and the contemporary, the refined and the doodled.” And I think he hit it. He wanted to include a desert island somehow, but couldn’t manage it. “Mimicking styles is always a little tricky,” he said. “I find it especially hard to capture the more spontaneous ones. In this case, I probably struggled most with Edward Steed’s line and design sense. His work feels so wonderfully improvised that it’s hard to boil down into a style.” He was asked what draws him to parodying literary classics. He answered: “I love working with preexisting texts and formats, and seeing what new mutations can come from combining them. Also, research is one of my favorite parts of the creative process, so studying different classic stories and styles keeps things fresh.” Nearby,

you’ll find an array of clippings that inspired Sikoryak’s cover art. And what have we learned by comparing the two Cartoon Issues? While I applaud The New Yorker’s decision to publish a Cartoon Issue again, Emma Allen’s effort, compared to Mankoff’s, reveals her weakness as an editor of cartoons: when she doesn’t rely upon others (non-cartoonists et al), her choices seem trivial and silly and nearly meaningless (Hammurabi, Horse). Mankoff’s, on the other hand, are usually edgier, more satirical than simply amusing. If you’d like some insight into the life and work of Mankoff as The New Yorker’s cartoon editor, you can find it in a documentary, “Very Semi-Serious, A Partially Thorough Portrait of New Yorker Cartoonists” (2015), which you can find by searching Amazon. Despite all of my small-minded nitpicking about the Cartoon Issue and Emma Allen, I’m glad to see this issue. It reaffirms what Harold Ross, the magazine’s founding editor, came quickly to believe about his new magazine: the cartoons were the best part.

YOU’LL DOUBTLESS NOTICE that the name Roz Chast crops up frequently in both Cartoon Issues. This stuns me. I think her drawing style is monotonous and stilted. All her characters have a pop-eyed look of astonishment. And the humor almost (but not quite) evades me altogether. A cartoonist friend explained to me Roz Chast’s appeal to him: he admires her sensibility. That’s doubtless the secret. So when it comes to cartoons, The New Yorker elects with Roz Chast to publish sensibility rather than comedy. Well, it’s their magazine, and they can do with it whatever they want. But they leave me in the lurch whenever Roz Chast shows up. The next issue of The New Yorker, by the way, was also different from most of its predecessors. It contained 11 pages of full-page photographs. These were pictures of the new cast members for a “West Side Story” revival coming in February. The New Yorker didn’t publish any photographs for almost all of its first ninety years. So times do change after all. In case you were wondering.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics

Mad No.11 is out. This is the first issue of the “new” Mad which will consist entirely of reprints of cartoons and stories from the previous half-century’s issues. I wondered how this would be possible: the satiric content of Mad has always originated wholly from current events; in a reprint, the events would no longer be current. And if you eliminate current events, you are eliminating most of the magazine’s satire. So what’s left? No.11 consists mostly of short articles and pages of cartoons. No parody of a movie or tv show. Sergio Aragones has a 4-page new year’s resolutions piece. Peter Kuper’s Spy vs Spy is here. Al Jaffee’s Fold-in is the inside back cover, as usual. But no Tom Richmond, the magazine’s resident caricaturist for many years. The cover article, “The 20 Dumbest People, Events, and Things of 2019,” is a sly enterprise. Each of the 20 items could be a reprint of something the magazine did over the past year. But with the umbrella title, they appear to be a current effort. So what can Mad do next time? Hereabouts, scans of some of the pages.

QUOTES & MOTS “In New York, the years that you spend as a nobody are painful but golden because no one bothers to lie to you. The moment you’re a somebody, you have heard your last truth. Everyone will try to spin you.”—Writer Peter Schjeldahl in The New Yorker (December 23, 2019).

TRUMPERIES The Criminal Antics and Highflying Idiocies of the White House Buffoon COINCIDENTALLY ENOUGH, the year of the Trumpet’s impeachment trial is the Year of the Rat in the lunar calendar. The rat is the first sign of the zodiac and is said to bring new beginnings, productivity and activity, especially in the realms of tech, IT, and health. So I guess the sneaky and traitorous character of a rat is not applicable, which leaves the Trumpet unscathed. But he’s being scathed enough in the trial by the House managers.

**** The Trumpet has moved to roll back the school nutrition standards championed by Michelle Obama, reports Lola Fadulu at the New York Times—a modification “long sought by food manufacturers and some school districts that have chafed at the cost of Obama’s prescriptions for fresh fruit and vegetables.” Food companies applaud the proposal and nutritionists condemned it, predicting “starchy foods such as potatoes would replace green vegetables and fattening foods such as hamburgers would be served daily as ‘snacks.’” The proposed rule change was announced on Michelle Obama’s birthday. A typically mean-spirited maneuver by the Trumpet. Officials deny it was a plot, but who’re they kidding?

***** OTHERWISE, the

nation’s editoonists have spent at least part of the last month in portraying

the Trumpet personality, exactly the sort of editoon that we file here, under

Trumperies. Signe Wilkinson provides a vivid image of the Trumpet administration: it consists mostly of the Trumpet preventing the truth from emerging. And finally, here’s Keith Knight whose picture of the Trumpet reveals that he is the Victim-in-Chief, belly-aching about everything that happens around him. And then Keef gets in a dig at racism in the lower right-hand corner. Compared to the Trumpet’s everlasting harangue, a little fusing about how racial minorities are treated in this country doesn’t amount to much. Moreover, unlike Trump’s whining, it’s justified by a couple centuries of history.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy The Trial As of today, January 19, I know how the trial of the Trumpet in the Senate will go before it gets there. Democrats will present certain “facts” which they assert show Trump unfit for the job and a danger to the nation. The Republicons will say all the so-called “facts” are rubbish—lies and gross misrepresentations. The Trumpet is innocent and should go on serving his country from the White House and at pep rallies for himself around the country. The essence of the dispute, then, is whether the case against the Trumpet is factual or fictional. To settle the argument, we must determine whether the allegations against Trump are true or not. Are they facts? Did the Trumpet make a phone call to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and urge him to announce an investigation into the Bidens in exchange for military aid and a visit to the White House? Did the Trumpet issue an order forbidding all White House staff from complying with subpoenas from the House of Representatives committees? The authenticity of the first collection of “facts” can be debated I suppose; but the second, obstruction of justice, seems patently obvious. This is a fact. It cannot be explained away by craven Republicons. And it’s another set of facts that call for the impeachment of Trump and for his removal from office before he can do further damage. He has no respect for the office he occupies, the people he represents, or the country’s ethics. He’s a danger to the country—its values, its political and governmental traditions, and its standing in the world. Ergo, get him out of there.

**** Well, now it’s the 20th, and the Trumpet Defense is emerging. They’re going to say, simply, that none of what Trump did was illegal. If there’s no crime, there’s no criminal. So he can’t be thrown out of office. There are almost four things wrong with this strategy. First, impeachment does not require that the scoundrel do something illegal. He must be guilty only of committing “crimes and/or misdemeanors.” Emphasize “misdemeanors.” Traditionally, political misbehavior is sufficient reason for impeaching someone. And the Trumpet is surely guilty of misbehaving. The 15,413 lies (as of December 10) that he’s told from the bully pulpit alone constitute misbehaving on the grandest scale we have ever seen. Second, he did, actually, commit a crime. By threatening to withhold military aid to Ukraine until Zelensky does as Trump asks, Trump is extorting Zelensky. Extortion is a crime. Third, Trump has failed to live up to the oath he took when assuming the office. Among the things that oath requires is that he “faithfully execute the office of the President.” The office of the President requires that he do as Congress directs with respect to the spending of appropriated money. Congress appropriated nearly $400,000 in military aid for Ukraine, and Trump withheld that. In so doing—no matter for how long—he failed to execute the duties of his office. If not a crime, it is surely a giant misdemeanor, ample justification for impeachment. And fourth, by harping on the Ukrainian caper, anti-Trumpsters are ignoring the more obvious of the offenses he has committed. He has, without question, obstructed justice by ordering that no one who works for him should obey subpoenas for documents or testimony before Congress. If that’s not obstruction of justice, I dunno what could qualify.

**** THE TRUMPET

BEING TRIED IN THE SENATE has supplied editorial cartoonists with a wealth of

issues to cartoon about. And since the trial isn’t over yet as of this writing

(February 1), I’ll refrain from posting too much on the topic. The Trumpet’s defense lawyers, as I indicated above in my essay, haven’t got much of a case either, and Bill Bramhall shows us that it is full of holes—the entire Republicon party, in fact, is a sieve. Wiley Miller, who was a full-time editoonist before launching his comic strip Non Sequitur, sometimes plucks a political dart from his quiver and flings it at those he finds objectionable. His imagery here accurately reflects the situation in the Senate trial: there are facts as they are, and the truth as some see it. And very often, the two are at odds as much as the image here suggests: an irresistible force meeting an immovable object. Finally, Tom Toles is back with the Trumpet’s final pronouncement on his impeachment. Nancy Pelosi is, of course, absolutely correct: whatever the outcome of the trial, Trump has been impeached. And his impeachment will be forever part of the history of his presidency. The Trumpet, of course, has the perfect response. And we’ll stop there. We’ll be back with a more complete menu of editoons next time, Opus 401—on all topics, not just impeachment. And we’ll be able to finish off the impeachment episode by reporting on the Senate’s verdict. It will undoubtedly be acquittal. And I’m not at all upset by that verdict. I’m bothered by the way partisanship has infected the proceedings rendering the trial itself a mockery, but the verdict is a relief. If the Senate had kicked the Trumpet out of office, the polarization in the country would reach new levels of severity—involving physical violence, doubtless— and recovering from it would take much longer—perhaps the rest of the 21st Century. How’s that? Not the “American Century” as the 20th has sometimes been dubbed, but the “Trumpet Impeachment” Century. This morning’s Denver Post carries an article that suggests that while the Senate will acquit Trump, it may also pass some sort of resolution chastising him for the inappropriateness of his behavior with Ukrainian President Zelensky. It may not have been an impeachable offense, but it was very bad form with highly questionable imagery—on the whole, damaging to the international standing of the United States.

PERSIFLAGE & FURBELOWS Mike Bloomberg sent me a letter. Me and millions of other registered Democrats, I assume. But he didn’t ask me for money. He just explained why he was running for Prez—: As a three-term mayor of the biggest and one of the most diverse cities in the country, I know how to get things done. ... If we’re going to beat Trump, we have to do it right. That’s why I never have and never will take a dime from special interests. We’re not just going to win in 2020—we’re gong to win clean. Then, the real work begins.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged “News” Institution A LEADING HOST ON FOX NEWS, a conservative network notorious for its loyalty to the White House, has lambasted Donald Trump for mounting the most direct attack on press freedom in American history. Chris Wallace, widely admired for breaking ranks from Fox colleagues by putting tough questions to administration officials, delivered his most stinging critique yet of the US president at an event celebrating the First Amendment (and reported over the Net, where we picked it up and are repeating it, verbatim, below—). Are Fox News and Donald Trump falling out of love? “I believe that President Trump is engaged in the most direct sustained assault on freedom of the press in our history,” Wallace said to applause at the Newseum, a media museum in Washington, on Wednesday night. “He has done everything he can to undercut the media, to try and delegitimize us, and I think his purpose is clear: to raise doubts when we report critically about him and his administration that we can be trusted. Back in 2017, he tweeted something that said far more about him than it did about us: ‘The fake news media is not my enemy. It is the enemy of the American people.’” Wallace recalled that retired admiral Bill McRaven, a Navy Seal for 37 years, had described Trump’s sentiment as maybe “the greatest threat to democracy in my lifetime” because, unlike even the Soviet Union or Islamic terrorism, it undermines the U.S. Constitution. The veteran broadcaster added: “Let’s be honest, the president’s attacks have done some damage. A Freedom Forum Institute poll, associated here with the Newseum, this year found that 29% of Americans, almost a third of all of us, think the First Amendment goes too far. And 77%, three quarters, say that fake news is a serious threat to our democracy.” Wallace is a rare dissenting voice at the Rupert Murdoch-owned Fox News, where opinion hosts such as Sean Hannity and Laura Ingraham are fiercely pro-Trump. Longtime anchor Shep Smith, who was also praised for his independence, stepped down in October and warned that “intimidation and vilification of the press is now a global phenomenon. We don’t have to look far for evidence of that.” Wallace, son of distinguished journalist Mike Wallace, conducts some of the sharpest grillings of any of America’s long running Sunday politics shows. When he recently took House minority whip Steve Scalise to task, Trump responded with a tweet that called Wallace “nasty” and “obnoxious”. But at Wednesday’s event, a farewell to the Newseum which is closing down after nearly 12 years at its current location, Wallace also warned the media against overreach. “I think many of our colleagues see the president’s attacks, his constant bashing of the media as a rationale, as an excuse to cross the line themselves, to push back, and that is a big mistake,” he said. “I see it all the time on the front page of major newspapers and the lead of the evening news: fact mixed with opinion, buzzwords like ‘bombshell’ and ‘scandal’. The animus of the reporter and the editor as plain to see as the headline.”

***** FREEDOM OF THE

PRESS is being attacked on another front where it’s a question of sheer

financial survival. Corporate owners want profits, and since

READ & RELISH In Texas, Mars Wrigley displayed a 12-foot long Snickers bar, the largest ever. Of course in Texas. Where else?

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL

WE HAVE A MIXED BAG to start with this time.We’ll begin with my faulty memory. I don’t remember Snoopy’s “friend” Poochie. She probably appears somewhere other than in this Sunday strip; I just don’t remember her. With Earl’s plugged nasal cavity in Brian Crane’s Pickles, we flip to unappetizing topics. Not repulsive; just not appetizing. And then with Rick Detorie’s One Big Happy, we return to the verboten. “Leaks” can refer to actual leaks, of course, but it’s pretty clear that in the last panel, Nick is referring to the urinary kind. Mentioning Oktoberfest and its presumed sports of imbibing gives him away. And then there’s Grimm in Mike Peters’ Mother Goose and Grimm. It’s Mother Goose’s admirable ingenuity that creates the comedy here—the sheer logic is unavoidable— but Grimm’s expression in the last panel is the frosting on the comedic cake.

HARDLY ARE THE

WORDS OUT OF MY MOUTH than Poochie shows up in Peanuts—the very

next Sunday. Bill Keane’s Family Circus, now conducted by son Jeff, sometimes can’t seem to make up its mind about whether it’s a single-panel cartoon with a caption/speech underneath or a comic strip with speech balloons. Or, in this instance, both. Jeff accomplishes this manipulation of form every once in a while, and the oddest thing about it is how persuasive the means are to the end: we know exactly who is speaking every time. No confusion at all. And the punchline is always underneath. And here comes Rob Armstrong with an ambitious fable for our time in Jump Start. The characters are the sun, earth, and the moon. And while it seems a comment on warming climate, it finishes with pure flatulent comedy. What a gas.

AND HERE’S A

MUSEUM PIECE—namely, a previously unpublished, never-seen-out-of-captivity set

of comic strips produced by yrs trly in the distant days of his long-lost

youth. Maybe I was older. Seventeen maybe. Some of the visual elements in these strips look like I was imitating Gus Arriola’s Gordo treatments—the round panels, the cross-hatch shading and irregular borders—and I didn’t get into Arriola’s great strip until about 1953-54. But I can’t say for sure, and the strips themselves don’t carry dates. The gags are pretty lame, I admit. As an editor, I had a lot to learn. But some of the visual aspects of the strips are interesting. (Or so they seem to me.) In the first panel of the first strip, Smitty’s “hum” is strategically placed to finish the sound of “museum” (musehum), and the “hum” indicates boredom, which is probably how I felt in those adolescent days about visiting museums. The fourth panel’s insertion into a larger panel, which divides them into two panels, looks like something I must’ve borrowed from Arriola. The bottom strip (which I signed twice just to be sure everyone knew who did it) offers in the last panel a nice visual touch of reality: Smitty is handing the barber a coin to pay for his haircut. It looks like I traced the “Smitty” logo from strip to strip: they are so identical that none of them could have been drawn separately. And this was long before xerox machines made such copying routine. But changing the colors in the word is doubtless another borrowing—probably from Arriola but I’m not sure. Ah, memory lane.

Tics & Tropes A bank robber pulls out his gun, points it at the teller and says, “Give me all the money or you’re geography!” The puzzled teller replies, “You mean history?” “Don’t change the subject.”

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Books In Need of Good Reviews THE RANCID RAVES Book Grotto is littered, literally, with books we acquired with the intention of reviewing them. Alas, they’ve piled up over the years, and it has become increasingly apparent that we’ll never give most of them the kind of intensive examination they deserve. So rather than let the accretion be entirely in vain, we’ve started this new department wherein we’ll briefly describe books by way of urging them upon you, beginning, this time, with—:

Willie & Joe: The World War II Years By Bill Mauldin; edited by Tod DePastino Two-volume Boxed Set, 2008 Fantagraphics Harcover, $95—: Vol.1, “Homefront,” October 25, 1940 - August 8, 1943 (including “at sea” going to the European theater of war); 306 8x10-inch pages Vol.2, “Overseas,” August 15, 1943 - July 30, 1945; 386 8x10-inch pages I PROBABLY MADE REFERENCE to this landmark publication when it came out in 2008, but it wasn’t until last month that I had occasion to consult it. Surprise! Until I opened Volume 1, I had supposed its content (and Volume 2's) was Mauldin’s famed Willie and Joe cartoons. It’s that, but it’s more. The cartoons in Volume 1 include a couple samples of Mauldin’s work in high school and for Arizona Highways, but most of this volume’s content comes from the newspaper published by the 45th Division, Mauldin’s regimental home in World War II. Mauldin did cartoons for it for years before joining the Stars and Stripes staff, where Willie and Joe made regular appearances from August 1943 through the end of the War. Joe was a walk-on character in the early years—a hook-nosed American Indian (the Indian population of the 45th Division was high; Mauldin gave them something to relate to). Willie was occasionally mentioned, but soon after the 45th landed in Sicily in 1943, Mauldin decided that the hook-nosed character was a better Willie than he was a Joe, and he switched names, creating an iconic duo for the duration. Mauldin’s distinctive trap-shadow drawing style didn’t appear until he was in Europe—i.e., Volume 2. He fashioned a bold-lined style because the printing equipment commandeered to publish The 45th Division News was either primitive or damaged and couldn’t be relied upon to reproduce fine-line drawings. Edited by Todd DePastino, author of the only Mauldin biography I know of: Bill Mauldin: A Life Up Front (2008 Norton hardcover, 370 6x9-inch pages, b/w cartoons plus text; $27.95; which I haven’t read either), the book is designed by Jacob Covey, who made the DePastino’s text pages look like a type-written government report.

Mauldin wrote the only genuinely insightful book about war—Up Front—ostensibly a collection of his WWII cartoons but the pictures are embraced by prose that tells another aspect of the story. For the whole history of Mauldin and a generous sampling of his cartoons, both wartime and post-war, see Harv’s Hindsight for February 2003. In order to make sense of the conclusion of that piece, here’s a Willie and Joe cartoon that’ll properly top it off.

CLIPS & QUIPS Giving money and power to government is like giving whiskey and car keys to teenage boys.—P.J. O’Rourke I don’t know what people have against the government—they’ve done nothing.—Bob Hope It’s easy being a humorist when you’ve got the whole government working for you.—Will Rogers

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words DUNNO WHO drew

this exquisite picture of Wonder Woman (it just wandered in over the Internet

transom), but I don’t want to lose sight of it, so I’m posting it here. Next, we have a couple sketches that we should have posted when we did Popeye’s 90th anniversary. But we’d lost track of them. And in this case, we didn’t even know we had them: they were buried under piles of paper on my desk (five piles, each at least four inches tall), and this week, in a frenzy of housekeeping, I am organizing my desk—and in the process, found these Popeyes.

Dunno, for sure, who drew them. There’s a note in my handwriting on the second one (the grid)—Tom Neely. So he did that one. And he may have done the other one, too. Looks like his work with only the other Popeye sketch as a guide. And while we’re at it, nearby are scans of some Popeye comic strips produced by Popeye fans (and cartoonists). Not part of the commemoration by the National Cartoonists Society that we annotated last time (Opus 399); but expertly done nonetheless. JEREMY: INSERT PopeyeStrips1 and 2 HERE; THEN DELETE THESE CAPITAL LETTERS. These are part of The Cartoon Club’s display of 52 Popeye strips at ComicsKingdom.com (the King Features site). Go there and see some more.

PITHY PRONOUNCEMENTS It was the Epicurean outlook on happiness that Thomas Jefferson was thinking of when he enjoined Americans to cherish “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness in the Declaration of Independence. As the Epicureans saw it, happiness is merely the lack of physical pain and mental disturbance. It was not about the pursuit of material gain, or notching up gratifying experiences but instead was a happiness that lent itself to a constant gratefulness.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST

And then (it’s about time) we have a vivid demonstration of why superheroes are all castrated before donning their skin-tight costumes.

Gunman Shot by Church Members. At first blush, it was the National Rambo Association’s dream come true. A good guy with a gun beat a bad guy with a gun. When an armed man began shooting at congregants on Sunday morning at the West Freeway Church of Christ in the little town of White Settlement near Dallas, members of the congregation stood up, took out their guns, and fired away, killing the gunman. This incident would triumphantly make the NRA’s point: bad guys with guns can be beaten by good guys with guns. And this church seemed fully populated with armed members who carried their weapons to Sunday worship, ever at the ready for the bad guys who might show up. That’s how the story originally broke on Sunday. But as time passed, more details surfaced. The gunman was a mentally unstable person who’d been in trouble numerous times. The church had repeatedly given him food; and he got angry when his demand for money was refused. On the Sunday morning in question, he showed up at church in a wig and false beard and a long black coat. Security cameras showed him talking briefly with a man next to the back wall then taking out a shotgun and starting to shoot. As soon as shots rang out, several of the congregation who were armed stood up and drew their weapons. But it was a member of the church’s volunteer security team who fired his weapon and shot the guy dead. Two other people were dead, one, another member of the security team. The volunteers regularly train in the use of firearms. So the incident was not quite the NRA’s dream. The good guy was not just any old good guy, one of several armed, open-carry Texas cowboy Christians in church that Sunday. He, along with other volunteer members of the congregation, had been trained in the use of firearms to defend against renegade shooters. Still, the situation did little to reduce the violent tendencies of Americans. If it was not a full endorsement of the NRA’s position, it was close enough. We should all get ourselves armed and carry our weapons on our belts. Not a vision of America that I enjoy contemplating. Armed people tend to resort to gunfire to solve their problems. Most of the civilian killing in the Old West happened in saloons where inebriated tempers flared. I’d been hoping we’d moved away from that by now. Guess not.

PEEVES & PRATFALLS

Kaylen Ward, an online sex worker and model who sells photos of herself naked, decided to put that effort to better use. Agonizing over the fate of wildlife in the wake of the wildfires in Australia, she tweeted out to her followers that she’d reward anyone who sent proof that they’d donated at least ten bucks to any one of several charities pledged to help in Australia: she’d send a nude photo of herself. At last reported count, she’s raised over $1 million. And if you gaze fondly over the accompanying illustrations, you’ll doubtless understand why. But all is not unalloyed joy in Mudville. “The Naked Philanthropist” had her Facebook account shut down because “offering nude images is not allowed.” And her family disowned her, and her boyfriend isn’t speaking to her. But, she says, “Fuck it. Save the koalas.”

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. And that’s about what you’ll see here, beginning with—:

Barney Google for President And Other Classic Comics from the Roaring Twenties By Billy DeBeck; Foreword by John Rose; Introduction by Brian Walker 353 4x11-inch landscape pages, b/w; 2019 IDW hardcover, $29.99 ANOTHER IN IDW’S Library of American Comics books that print one daily strip to each page, a format, the publisher believes, that will seem like reading the strip, one day at a time, in the newspaper. Nice idea. The Foreword is by the man who presently produces the Barney Google strip, now entitled Snuffy Smith and focused on hillbilly antics. Walker, who has supervised one other collection of DeBeck’s masterwork (Barney Google and Snuffy Smith: 75 Years of An American Legend) provides biographical information on DeBeck and historical insights on the strip he invented, plus plot summaries on the four sequences this volume reprints: The Million-Dollar Cross-County Marathon, May31 - October 1, 1926 Spark Plug Swims the English Channel, October 2 - December 7, 1926 Mysterious Order of the Brotherhood of Billy Goats, October 7, 1927 - February 8, 1928 Barney Google for President, February 9 - April 26, 1928 The first two sequences properly reflect the competitive enthusiasms of contests of all sorts, and swimming event concludes in Paris, where Barney buys a few of those “nifty” postcards. (We never see any of them: he throws them all away when threatened by the scrutiny of a menacing gendarme.) The Billy Goats sequence ridicules secret brotherhoods and “orders” with members who wear goat-like headwear and run around chanting their slogans—“Horsefeathers” and “okmnx” (okay ham and eggs; I suppose the translation is the “secret” word of the order). Barney is soon the chief angora goat, and with the membership behind him, he runs for President. Ultimately, he retires from the race before he could win it. Barney Google began life in his strip as a normal-sized man, but he was so henpecked by his wife that he shrunk until he was only knee-high to her. Subsequently, she disappeared from the strip, and Barney began pursuing all the beauteous femmes he ran into. While his divorce was never formally announced in the strip—divorce was taboo in comic strips—“I think for the most part Lizzie Google just disappeared,” John Rose told me. “Barney was free to roam the country and flirt with pretty girls, but his marital status was left unclear,” Rose went on. “There probably were future references to his ‘sweet woman’ but she was never a regular character again.” But Rose recalled that the popular song “Barney Google with the Goo-goo-googly eyes” had a verse that settled the matter:

Barney Google—with the goo-goo-googly eyes, Barney Google—had a wife three times his size; She sued Barney for divorce, Now he's sleeping with his horse! Barney Google—with the goo-goo-googly eyes!

DeBeck, Walker notes, was a meticulous craftsman. He sketched constantly in notebooks and carefully reproduced details, from folds in clothing to architecture, in his renderings. And when Barney goes into the hill country and meets Snuffy, DeBeck studied the lingo of the hillbilly community and kept detailed lists of picturesque expressions. “Most cartoonists have strengths and weaknesses,” Walker writes, “but DeBeck could do it all. He drew gorgeous women and goofy-looking men. His characters were distinctive and memorable. He alternated scenes between violent action and peaceful repose. He had an excellent sense of design. ... His rural settings evoked an appreciation of natural beauty. He could be dramatic, poetic, or romantic and still retain a sense of humor.” The strips reprinted herein are from what many believe is the pinnacle of Barney Google’s life and adventures, when DeBeck was at the top of his form. We conclude with a smattering of strips from this volume.

Fitnoot. In addition to Brian Walker’s survey of 75 Years of Barney Google, Craig Yoe has published another collection—a few scrapbooky items and the 1922 sequence (from May to December) that includes Barney’s acquiring Spark Plug and their first adventures together.

Pogo, Clean as a Weasel The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips: Volume 6 By Walt Kelly; Foreword by Jim Davis; Annotations by R.C. Harvey 350 9x11-inch landscape pages, b/w and color Sundays; 2019 Fantagraphics hardcover, $45 THE LATEST VOLUME in the Fantagraphics reprint project covers 1959 and 1960, daily strips and Sundays. The kind of political satire that so distinguished the strip when Kelly attacked Joseph R. McCarthy (Volume 3) is nearly absent in this volume. Instead, as Kelly said, “normal lunacy burst upon us,” and Pogo and his friends go unabashed about their usual untrammeled nonsense, which consists mostly of taking too many ordinary utterances literally, leap-frogging haphazardly from one misapprehension to the next, and otherwise going off in all directions at once, littering the swamp with bad puns and mistaken identities and other wholesale hilarities everywhere they went. The threat of Russian communism and of Cuba under Castro hangs over the proceedings in the strip, and Khrushchev shows up twice as a Russian bear, but Kelly is just fooling around. As Mr. Wasp says, “I’ve heard coughin’ fits what had more sense in ’em.” The Presidential Election Year is the major preoccupation of Pogo in 1960, but neither candidate is impersonated in the strip. And, given the nature of American politics at the time, we must agree with Howland Owl when he says: “It’s hard to think of nothin’ to say.” But Kelly does it—joyfully, exuberantly. Although celebrated for his political allegory and satire, Kelly laced Pogo with allusions to other aspects of contemporary life in America, plus literary references and snatches of poetry. In our less than literate society of 280-character communiques, many of Kelly’s nods at literature and history are obscure to the point of irrelevance, and the targets of much of his satirical sniping are no longer visible: six decades after the fact, the events he so gleefully mocked have long been forgotten. My annotating assignment at the back of the book is to pull back the veil that the passage of time has drawn over the Pogo proceedings, thereby to remind us of some of those things we’ve lost sight of. For Pogo fans, this volume—like the five that preceded it—is indispensable. For the few pitiable souls who aren’t, yet, Pogo fans, this book is as good as any place to start.

PERSIFLAGE & BADINAGE

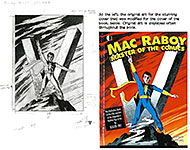

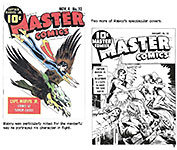

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets