|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 399 (December 17, 2019). Play the oboe and bagpipes merrily—it’s time for our anyule extravaganza, for which we include a wildly illustrated celebration of Popeye’s 90th birthday. We also contemplate Playboy-like covers of comicbooks (the end of the year signaling, as it used to, the emergence of a fresh crop of calendar girls) and editoonery coverage of The Impeachment and Alan Moore’s beard and hair. We review the end of Mad and the start of Crazy, Peanuts Papers, the awful finale of tv’s “Watchmen,” graphic novels Corto Maltese: The Early Years and Stumptown, and IDW’s Dick Tracy, plus long, appreciative obits for Howard Cruse, Gahan Wilson, and Tom Spurgeon. Here, cryptically, is what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Back Issue Biz Booming Lendelof’s “Watchmen” Ends Awfully Clifford Starts a New Television Adventure Mankoff’s New Gig Zapiro Gets French Award Lynda Barry in Family Circus Alan Moore says He’ll Be Voting This Time Drag Show at Comics Store Heroes in a Paper Bag

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Trees: Three Fates

Short Ribs Jughead the Hunger vs Vampironica Gunning for Hits Dying Is Easy Yondu Moonshine Pretty Deadly: The Rat Dick Tracy (Two Versions)

ANNIVERSARIES Berlin Wall Bonanza

TRUMPERIES More Antics of the Chief Idiot

EDITOONERY Surveying the Political Cartoons of the Past Month

THE FROTH ESTATE Shepard Smith Retires

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Odd, Profane, and Obscene Content in Today’s Funnies

POPEYE IS 90 And Thimble Theatre Is 100

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Previews Catalogue and Playboy Pinups Sexual Adventures on Comicbook Covers and Inside Moran Pinups BOOK MARQUEE Reviews of—: Peanut Papers End of Mad; Start of Crazy The Serious Goose by Jimmy Kimmel Kent State Killing in Graphic Novel

BOTTOM LINERS Gag Cartoons

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Graphic Novels Reviewed—: Corto Maltese Early Years Stumptown

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Impeaching the Trumpet Some More

PASSIN’ THROUGH Howard Cruse Gahan Wilson Tom Spurgeon Lew Little

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

BACK ISSUE BIZ IS BOOMING "Back issues sales are definitely up, and have been a growing piece of our business for the last 2-3 years running, after a long lull," Joe Field of Flying Colors Comics in Concord, California told Jim McLauchlin at ICv2.com. But the traditional, gotta-have-’em all collector seems to be a dying breed. "There is more activity in first appearances of characters, of maybe collecting specific artists or writers," Field continued. "But in terms of collecting things to have a complete collection— I really think the publishers have blown that market up by constant restarts and doing 'seasons' rather than long-running series." The scene looks the same to Carr D’Angelo, who owns the two Earth-2 stores in Los Angeles. "There's still that classic guy with his list out there, and he’s buying only the issues he needs to fill in his run, and I love that guy," D'Angelo said. "But I think there are more people buying back issues just because it brings them joy." "There is the return of speculators," D'Angelo continued. "There are day-traders dedicated to the idea of flipping comics, literally flipping them in a day. They want to buy Once and Future from BOOM! Studios for $4 that day, and sell it for $10 on eBay that night. I dunno. You can't even buy lunch with what you made after eBay fees and all, but there are definitely those speculators." That very word "speculative" is a dirty one to some retailers. But collector Nick Coglianese thinks those people are fighting the wrong enemy. "A lot of people shit on speculators, but I kind of look at the comic industry as this giant, three-pole tent," he says. "Your poles propping it up are the readers, the collectors, and the speculators. They're all contributing to the industry. They're all holding up their part of that tent. And if one goes… no one wants to see that. People might say, 'I hate speculators; I want to see them go away.' Well, if they went away, that's one big chunk of comics revenue that goes away with it."

WATCHMEN ENDS—AWFULLY I watched the last installment of Damon Lendelof’s “Watchmen,” hoping the finale would tie together all the loose ends of the series and somehow thereby rescue the whole muddling- through production. Alas, that didn’t happen. The last chapter was as disappointing as the first and all those in between. Nothing that we now know or think we know makes any of the meandering menace of twist upon twist any clearer at the end than it was at the beginning or anywhere along the way. Throughout, we don’t have a clear notion of who the good guys are and who the bad guys are. At times, Lendelof’s “Watchmen” seems to incorporate some sort of racial warfare complete with Ku Klux Klanners of its own. But what happened to the Seventh Kavalry? Dunno. The only constants are Regina King as Angela Abar, aka the hooded Sister Knight, and Jeremy Irons as Adrian Veidt aka Ozymandias, who seems a sort of villain. But Veidt is still standing at the end. Dr. Manhattan, who hovers over the whole series as a blue super-powered good guy, finally shows up only to dissolve with a bang, leaving Abar pondering her fate and Veidt still smirking, knowingly (but without letting us in on the secret). The end is fraught with this sort of smirking. Louis Gossett, Jr., seems to know why he’s smirking, but he doesn’t tell us. “To make an omelet,” he murmurs, cryptically, “—you have to break some eggs.” Now, there’s a brilliant observation. How did Lendelof come up with that one? So the meaning of his production rests on a tired old piece of folk wisdom? Then we are treated to a few choruses of “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning” from “Oklahoma” (ironic because this story is set in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where the nation’s worst race riot took place in the 1920s). I know the songs in “Oklahoma” better than I know anything. My father bought a 33 rpm record player when I was about ten (that would be in about 1947), and for some time thereafter, the only long-playing record we had (the only one we could afford for a while) was that of the songs of “Oklahoma.” But my grasp of these timeless lyrics shed no light on the ending of Lendelof’s “Watchmen.” Then Abar breaks the only egg that has somehow survived the smashing of a carton of eggs, eats it raw (because Gossett told her “you are what you eat” or some such snatch of wisdom), and then, to see if eating raw egg will enable her to walk on water, puts her foot out over a swimming pool. She’s about to step down when—. Poof. The whole thing ends and credits crawl up the screen. We are left in ignorance about whether Sister Knight can walk on water or not. “I’ve got a beautiful feeling, everything’s comin’ my way.” I’m majorly baffled. Smart people and knowledgeable critics all think Lendelof has produced a masterpiece. I can’t see it. Instead, what we get is a lot of looming allusion, motif after motif, and twist upon twist until the whole narrative is knotted beyond unraveling. The thing about allusions is that they must be made to mean something: it’s not enough to just sing songs from “Oklahoma” during the racist 1920s in Tulsa. So what? Is that good or bad? What are we supposed to think about it? Or is the whole point just irony? And the connection to Alan Moore’s “Watchmen” is likewise beyond my keen. Apart from a few characters—Dr. Manhattan, Ozymandias—there is no obvious connection in theme or plotline. But people will be talking about this thing forever. “I’ve got a beautiful feeling, everything’s comin’ my way.” Phooey.

CLIFFORD STARTS A NEW TELEVISION ADVENTURE Scholastic Entertainment is debuting a brand-new Clifford the Big Red Dog tv series, based on the Norman Bridwell books. It premiered on Amazon Prime Video on December 6, reported Karen Raugust at publishersweekly.com, and on PBS Kids on December 7. The new series is the third for Clifford, after the original Clifford the Big Red Dog, which aired on PBS from 2000 to 2003, and the spin-off Clifford’s Puppy Days, which PBS carried from 2003 to 2006. The new series consists of 39 22-minute episodes over three seasons, each featuring two 11-minute stories, and will be doled out in two drops per season of six to seven episodes each. The new show differs from the original in several ways, according to Caitlin Friedman, senior v-p and general manager of Scholastic Entertainment and co-executive producer on the series. “Emily Elizabeth and Clifford can speak to each other, which they never did before,” she said. “And Emily Elizabeth drives the action this time, along with Clifford. They’re in it together.”

MANKOFF’S NEW GIG Reveals That He Was Fired Bob Mankoff, once cartoon editor at The New Yorker, is now peddling cartoons through CartoonCollections, where interested parties can buy cartoons off the Web. The operation is an invention of Mankoff’s, who introduced it under another name—Cartoon Bank—before becoming cartoon editor at The New Yorker. (In fact, he agreed to sell Cartoon Bank to the magazine if he’d be made cartoon editor there.) In a news release describing his new version of the service, Mankoff reveals that he was fired at his previous job: “Another lifetime ago, actually just back in 2017, I was cartoon editor of The New Yorker,” he says. “I really liked that job but not so much that I wanted to stay on, especially after I was asked to leave. I really had to go then or I would have been arrested. “But why was I asked to leave? I like to think it was for appropriate behavior: selecting the cartoons that I thought were the best regardless of the identity of those who did them. I still think that’s the best way to increase diversity without sacrificing quality.” Mankoff was followed into The New Yorker’s cartoon editor gig (he was “followed” not replaced) by Emma Allen, a young woman who has absolutely no aptitude for the job. She thinks cartoons are cute designs that break up the pages gray with type. Her selections of cartoons betray a predilection for silliness, often in the form of talking animals. By appointing her to the job, editor David Remnick effectively ended his magazine’s reign as the most prestigious venue for single-panel cartooning in the nation. Having disposed of The New Yorker, Mankoff went on about his new job: “Now this might sound like sour grapes, but it’s not, anyway not now, because leaving that great job has given me the opportunity to do something I could have never done while there. So those grapes are turning out to be quite sweet. “That something was to launch, one year ago, CartoonCollections.com ... the Google of the single-panel cartoon. That’s Google when its motto was ‘Don’t Be Evil’ rather than ‘Give Us All Your Money.’ “Google’s original stated mission was to ‘organize the world’s information.’ Ours is to organize the world’s great cartoons, and that means many more than just cartoons from The New Yorker (although we’ve got the best of those— thousands of them). We also have thousands of great cartoons from Esquire, The Wall Street Journal, National Lampoon, Weekly Humorist, Narrative, The Rejection Collections, Wired, Air Mail and many exciting collections to come. “This is the first of many missives to come from my desk so stay tuned or, if you like lame wordplay, ‘tooned’. Now go and support us and our cartoonists by giving us all your money.”

ZAPIRO GETS CHEVALIER DES ARTS ET DES LETTRES South African editoonist Zapiro was presented with the Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres, one of France's highest cultural honors. Zapiro, aka Jonathan Shapiro, was given the award in recognition of his contribution to international culture. Making the presentation was the French Ambassador to South Africa, Aurélien Lechevallier, who said: “What a great honour to bestow today upon Zapiro the award of knight of the order of arts and letters. In him France wants to give recognition to an artist, a friend, but also a freedom fighter who shares the values of the French. Everywhere in the world, we are looking for the shape of truth. And from time to time, in the silence of a closed room, in the mystery of an inspired mind, a gifted-woman or a gifted-man decides that the shape of truth should be... a cartoon." Established in 1957, the Order of Arts and Letters is awarded by the French ministry of culture “in recognition of significant contributions to the enrichment of the arts and literature in France and abroad.” Zapiro is well known for his political cartoons, particularly those celebrating former president Nelson Mandela and those satirizing later president Jacob Zuma. His work regularly features in the nation's press. The 61-year-old cartoonist was ranked by Jeune Afrique magazine as one of the 50 most influential personalities on the African continent. It was a drawing on the anti-apartheid movement that made him famous. "It provided a springboard for my career,” Zapiro said. “I tried to reproduce the excitement of belonging to the anti-apartheid movement of the 1980s. And then, you see, I used to draw policemen as pigs. When they saw this, they came to get me, and they asked me: 'Why are you drawing us as pigs?' I said I was drawing what I was seeing. They put me in isolation for that," he explains. Former President Nelson Mandela is his favorite. "I had the idea of using Mandela's face, instead of the rising sun, to symbolize renewal," says Zapiro. The artist developed a special relationship with Mandela. But not all subsequent presidents appreciated his sense of humour. Jacob Zuma particularly resented that Zapiro always depicted him with a shower faucet on his head. "He was asked what he had done to protect himself after he had consensual sex with an HIV-positive person,” Zapiro said. “He replied that he had taken a shower to reduce the risk of infection. So then I started drawing a shower faucet on his head. And this idea had a success that I would never have imagined.” For more in this vein (including the shower faucet cartoons), see Opus 263 (June 2010); scroll down to “Thorn in the Side” for biography and a few representative cartoons.

AT THE PRESENTATION CEREMONY, emotion was palpable in the air, partly because of the memory of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists who lost their lives during the January 2015 attacks and to whom Zapiro paid homage; partly because of the threats to his life he personally often faces, a glaring reminder that true freedom of speech remains a distant dream even in 2019. This was a celebration of cultural and artistic excellence, as well as a nod to the complex, demanding and at times dangerous work done by satirical cartoonists, and the “fire” of laughter – or anger – they spark with their ink. Lechevallier is quoted forthwith. “They play with fire. And when I say fire— I refer to all its meanings. One mistake and a bonfire is lit. One step across the border and the dragon of censorship is awake. One step back, you burn the idea. One step aside, and the anger of the mob bites you. Three steps away from the politically correct and you may unleash the fury of the government and the faithful servants of the moral laws. If you are too harsh, you create pain. Too blunt, you cause suffering. Too clear, you are not funny anymore. Too ambiguous, too vague, you miss the point. “Cartoonists are like an archer, an arrow that can never miss the very centre, the dark spot of the target, a long distance away. Every day, they walk on the tightrope. But when they walk, like Zapiro, on the ground, they really play with a good type of fire. The kind of fire that ignites laughter when you would think you are no longer able to laugh. The kind of fire that heals the pain, that lifts the suffering. It is the light of a sun that shows the true face of the beauty or, on the other hand, the ugliness of a human soul. A fire that spreads to the mind and sparks a series of thoughts and new ideas. A fire that we can share with friends, with colleagues, with strangers in the street. A fire that is at the heart of Art, at the essence of what we call literature or Letters in French.” Just one level below the Legion of Honour, the Order of Arts and Letters is a symbol of cultural and artistic brilliance; it was awarded to Susan Sontag, Patti Smith and Steven Spielberg, to name but only a few. Zapiro was bestowed the order because he shares “the values that define and guide [the French] Republic: the trilogy, equality, liberty and fraternity, resonate perfectly with who you are, what you believe in and what you stand for,” explained Lechevallier. He added: “What is the shape of truth? What is the shape of freedom? What are the shapes of independence, sovereignty, nation-building? What is the shape of Ubuntu? Is it a sculpture? Is it a painting? Is it a photograph? Is it the sight of the people demonstrating and walking down the streets? Is it an architectural structure, a temple with five columns supporting the antique roof and a strong, large gate made of bronze? “Everywhere in the world, we are looking for the shape of truth, the shape of liberty, the shape of justice. In Afghanistan, in Mali, in Haiti, in Burundi, in Syria, in Israel, in Palestine, in France, in South Africa, people are looking for the shape of the truth. And from time to time, in the silence of a closed room, in the mystery of an inspired mind, a gifted woman or a gifted man decides that the shape of truth should be actually… a cartoon.”

BORN IN CAPE TOWN in 1958, Zapiro studied architecture before enlisting in the army while refusing to bear arms. In 1983, he joined the United Democratic Front, and later obtained a Fulbright scholarship to study caricature at the School of Visual Arts in New York, for two years. During a trip to Paris, he recalls looking for French comic book artist and scriptwriter – and the man behind Astérix et Obélix – Albert Uderzo’s home, in the hope of meeting him. Slightly lost, he managed to find the place at past 10:30 in the evening, and in spite of the tardiness, knocked on the door. A few hiccups (Uderzo didn’t speak English and Zapiro barely any French) and many questions and answers later, Zapiro had decided: he’d be a cartoonist. He has published close to 20 annual bestsellers as well as The Mandela Files, VuvuzelaNation and Democrazy; he has won numerous awards, “including the Mondi Shanduka Journalist of the Year award, an honorary Alan Paton Award and two honorary doctorates.” The Chevalier award acknowledges the fight he continues to fight for freedom of expression, equality and dignity. “In a time of inequalities all around the world, in a time of divided societies in Europe… and in Europe, where sometimes people forget about values and principles, you go to all places, talk to people from all walks of life, rich or poor, black or white, with the same passion for truth and humankind. And you always stay true to your core values, the core values that some kind of fire ignited a few years ago, not very far from here, during your school years,” said Lechevallier. “Today, we honour the activist, the freedom fighter, and also the messenger, the passer on, the one who shows the way and carries the values of the struggle to pass them through generations, without rest, and without borders.”

LYNDA BARRY IN FAMILY CIRCUS From Evan Chung at Studio 360 Since 1960, the newspaper comic strip The Family Circus has delivered cutesy malapropisms and observations from its cast of adorable kid characters according to my anonymous source on the Web. And for just as long, that source continues, it’s been relentlessly mocked as cloying and sentimental. But cartoonist Lynda Barry is willing to get into fisticuffs with anyone who says a bad word about the strip. Recently, Barry explained how she found deliverance in The Family Circus as a small child, before she even knew how to read. The circular panel in the newspaper comics page offered an alternative to her own troubled family life. “I

used to just love to look within that circle,” she says. “And within that

circle there was a family that just looked like they were having a really happy After becoming a cartoonist, Barry eventually met Jeff Keane, the son of the man who created The Family Circus who now produces the feature — and burst into tears. “When I shook his hand, part of the reason I was crying so much was I realized I had crossed into the circle,” explains Barry. “I’d stepped into it.” And in 2017, she actually did show up in the circle.

ALAN MOORE SAYS HE’LL BE VOTING THIS TIME ON HIS OFFICIAL FACEBOOK page for November 20, 2019, Alan Moore railed on as follows: Here’s something you don’t see every day: an internet-averse anarchist announcing on social media that he’ll be voting Labour in the December elections. But these are unprecedented times. I’ve voted only once in my life, more than forty years ago, being convinced that leaders are mostly of benefit to no one save themselves. That said, some leaders are so unbelievably malevolent and catastrophic that they must be strenuously opposed by any means available. Put simply, I do not believe that four more years of these rapacious, smirking right-wing parasites will leave us with a culture, a society, or an environment in which we have the luxury of even imagining alternatives. The wretched world we’re living in at present was not an unlucky turn of fate; it was an economic and political decision, made without consulting the enormous human population that it would most drastically affect. If we would have it otherwise, if we’d prefer a future that we can call home, then we must stop supporting – even passively – this ravenous, insatiable conservative agenda before it devours us with our kids as a dessert. Although my vote is principally against the Tories rather than for Labour, I’d observe that Labour’s current manifesto is the most encouraging set of proposals that I’ve ever seen from any major British party. Though these are immensely complicated times and we are all uncertain as to which course we should take, I’d say the one that steers us furthest from the glaringly apparent iceberg is the safest bet.

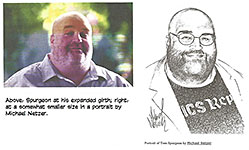

A world we love is counting on us. RCH: Last time, we reported that Moore was mildly upset that his notoriety resulted in strangers recognizing him and staring at him as he navigated the streets in his hometown, Northampton, England. I noted that maybe it wasn’t his fame that prompted stares but his appearance, which we now post an instance of right here.

DRAG SHOW AT THE COMICS STORE If you missed our earlier report, here’s more detail on the subject—: Denver’s Mile High Comics hosts a monthly all-ages drag show that affords kids and their families an opportunity to celebrate themselves in a safe environment. Owner Chuck Rozanski told reporter Avery Kaplan that, given the resources available to the store, they feel compelled to provide a space for the event to take place. “I believe that transgender and gender-questioning kids suffer more bullying and discrimination than any other youth demographic,” Rozanski said. “Providing them with a safe space for 3 hours each month to just be kids and enjoy each other’s company is a very heart-warming endeavor. I own a huge building, banquet tables that seat 400 for events, and a full-size performance stage, so it only makes sense for us to let the kids put on their monthly shows.” Rozanski, who comes in drag himself as Bettie Page, says the store has received a huge amount of positive feedback, from those within the community and from the public at large. “People actually stop me on the street to thank me for having the courage to resist the neo-Nazi’s,” he/she said. Attendance at the monthly show, which carries a suggested donation of $5 and provides free snacks, has only grown since it began earlier this year. “Our first show had about 175 attendees, last month’s show was over 400, which makes our show the single-largest drag event in the entire state of Colorado. The Denver community loves and supports us.” But response hasn’t been entirely positive, Kaplan observes: alt-right protestors have taken to regularly gathering outside of the store during the monthly performance. “We have had nasty alt-right protestors harassing attendees of our shows since day one,” explained Chuck/Bettie. During the seventh all-ages drag show, which took place on September 29th, the situation outside grew so tense that it earned coverage in the Denver Post. Fortunately, Mile High Comics has some innovative methods of circumventing noisy hate groups like the “Colorado Proud Boys.” “To

provide a safe passage for families to our store from our parking lot we cut

through an old chain link fence, and then installed our beautiful rainbow

bridge over the abandoned rail tracks in between the parking lot and the store.

The bridge has been a huge hit!” In addition to the rainbow bridge, a group of volunteers that have been dubbed the “Parasol Patrol” hold up rainbow-colored umbrellas to shield those entering the store from the vitriol spewed by the groups outside. Mile High Comics has lost some patronage as a result of hosting the drag show. “I have forever lost about 10% of the people who shopped with us,” wrote Chuck/Bettie. “On the flip side, however, those who love what we are doing are actively replacing all of those lost sales, and much more. Frankly, I truly prefer to not do business with people whose hearts are filled with hate… “As the International Court System Imperial Crown Princess of the Americas, I am blessed to be among the leaders of our national LGBTQ world,” explained Chuck/Bettie. “As such, I feel that I need to lead by example, so I try to help out as much as I can at events all around the nation. I travel pretty much every week.” Asked about his favorite comics, Chuck/Bettie said: “The Desert Peach is one of my favorites, as is Castle Waiting, and Strangers in Paradise. Harold Hedd was my bisexual hero, while Gay Comix was all over the place.”

HEROES IN A PAPER BAG One of my ritual annual adventures is setting up a table of my wares at the Rocky Mountain Con, which was held this year on the first weekend in November. Among the treasures I encountered while roaming the room was Matt Barclay’s Lunch Bag Lab, wherein Barclay draws cartoon characters on brown paper bags and sells them for five bucks each. I told him last year that he was criminally underpricing his work, and I repeated myself this year. These are original art, I explained—waving my hands helplessly over the display of bags at his table. “There are only one of each of these. They’re rare. You should price them accordingly.”

Frustrated and exasperated, I naturally committed five bucks to buy one of his bags, seen nearby. You can tell Matt what you think at lunchbaglab @gmail.com, and you can see a vast array of his bags and his subjects at his Facebook page for Lunch Bag Lab where they’re displayed one one-of-a-kind bag at a time. As for keeping his prices within the range he imagines kids can pay, I didn’t bother reminding him that comicbooks cost at least $4, and kids seem to collect them even at that rate.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO

And Cep’s article was accompanied by Tom Gauld’s full-page illustration you see near here. It’s not exactly that universal symbolizing of an idea by putting a light bulb in a thought balloon, but it’s close enough for government work. And I like it.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium. WARREN ELLIS’ Trees: Three Fates is an almost perfect example of failure on most of the criteria outlined above. I’m up to No.3 of Trees, and I still can’t tell you what’s going on. In the first issue, a giant tree (or is it two? or three trees?) plops down vertically in the wilderness—straight up, as if it had grown there— crushing a cabin (and its inhabitants? not sure). The trees lurk through all three issues, but nothing happens in connection with them. They’re just there, lurking. We meet several characters. Klara and Sasha, Nina, Mik, Lev, Tim and Pavel, Marsh, President Caleb Rahim (who provides a not-at-all-helpful lecture on the Puntland Tree), Darya, Oleg. I could go on. I think I missed a couple. But it wouldn’t matter. We don’t find out anything about any of these folks except that they quarrel a lot, and maybe someone tried to kill Oleg. Why? Dunno. There is, in other words, too much mystery and not enough explication, or, even, hinting. The first issue contains a murder victim and a police officer investigating. But this circumstance isn’t pursued in subsequent issues. I think. I’m not sure because I’m not sure I’m seeing the same characters from one issue to the next. Jason

Howard’s drawing is sharp, pointed, angular—the perfect grit, you’d think,

for Ellis’s grinding story. Except that Howard’s rendering of individual facial

features isn’t clear. His work is too stylized. Beautiful, gritty. But not

distinctive enough from character to character. They don’t all look the same,

but the pictorial individuality isn’t clear from one to the other. The central episode in No.1 is finding the murdered man. But it goes nowhere. And it shows only how unfeeling the police officer is, how methodical. And then she doesn’t show up again. I think. So. What are the trees? How many are there? Who are these people? What are their relationships? Is there a hero? Heroine? Protagonist of any description? Which of them should I get invested in? Too much mystery after three issues. Admittedly, Ellis’ purpose is to be mysterious. And he’s dropped enough provocative notions that he keeps me hooked. But it’s really too much. Somewhere along the line, he should have singled out one character to focus on, to let us get to know. Something engaging. Mystery is engaging, but not enough by itself. By itself, it’s just baffling.

SHORT RIBS In Jughead the Hunger versus Vampironica, the traditional Dan DeCarlo art style has all but evaporated. Throughout are simple, bold lines reminiscent of DeCarlo but attuned to more realism in rendering by Pat and Tim Kennedy and Joe Eisma. And the storyline by Frank Tieri is a couple notches above the usual competition between Betty and Veronica. I checked in to No.5 and found these pictures.

Still following my instinct for art rather than story, I grabbed Jeff Rougvie’s Gunning for Hits, a “music thriller,” a daring theme—music in the age of self-reflecting superheroes? sound in a visual medium? Yeh, daring— about big-time music and weapons in the hands of nutso singers. This issue ends a story arc: the nutso guy falls to his death after just barely hitting the headliner singer he was shooting at. The singer survives; the nutso doesn’t. Moritat draws mostly with a simple, bold line albeit somewhat more realistically than the Kennedys/Eisma. Here are a couple pages showcasing his style in rendering as well as his manner of laying out pages and deploying panel composition.

To

better appreciate what Moritat does with a page, contrast the first of his

pages just posted with this page from Dying Is Easy by Joe Hill (words) and Martin Simmonds (pictures). Not

since the late 1990s have we had a character so crude and brutal (not to

mention powerful) as Lobo, invented, they say, at DC to mock Marvel’s Wolverine.

Now, twenty years later, Marvel is getting even with the eponymous Yondu, every

bit as ugly in physique and manner as Lobo. Written by Zac Thompson and Lonnie

Nadler and forcefully drawn by John McCrea, the tale quickly

introduces us to the title character, who eeks out a living by stealing. The

chief Yondu thread here is his finding a precious object, the Herald’s Urn, and

scheming to sell it for a fortune. The universe Yondu lives in is populated by

refugees from that memorable bar Han Solo wandered into in the first “Star

Wars”; Yondu is the most recognizably humanoid in the book. Brian

Azzarello’s Moonshine is up to No.13. It doesn’t come out all that

frequently, it seems to me, and so I’ve lost track of the story. But that’s all

right: I don’t read it for the story (which is about hillbilly werewolves and

big city gangsters and Southern prison chain gangs): I read it for Eduardo

Risso’s pictures. His pictures and his pages. His pages are designs into

which he floats panels across mini-panoramas. And the pictures within the

designs—sometimes making the designs themselves—are delicious deployments of

solid blacks. Here are a couple of exquisite pages to ponder. On

the left is a page on which all of the discernable shapes and figures are

etched in solid black. The panels are the bottom are suspended in the black of

the livingroom scene at the top. In the livingroom, notice such details as the

framed pictures on the wall at the right, and the delicate design of the

tablecloth at the upper left. On the page at the right, the scene-setting

picture is tilted; then at the lower left, we see a cat on a Emma Rios’ pictures in Kelly Sue Deconnick’s Pretty Deadly: The Rat No.1 are also fascinating. But many of her pages, wonderful to look at, are designs without narrative impulse. Risso’s pages tell the story; Rios’ pages entertain without plot or point.

DICK TRACY FOREVER. After several issues of its Dick Tracy comicbook, IDW evidently wearied of artist Rich Tommaso’s awkward stylings (see Opus 385) and switched to Michael Avon Oeming, who wrote as well as drew the 4-issue run of Dick Tracy Forever and did an

absolutely bang-up job of it. Oeming’s art is light-years better than Tommaso’s. The pages—from individual panels to over-all design—are lively and energetic: if the characters aren’t moving violently, the camera is, changing distance and angle constantly. Halfway through, Oeming turns a big-city nighttime skyline into a crossword puzzle that fits right into the continuity. And one of the covers seems to me a sly response to my criticism of Tommaso’s art —that he couldn’t draw Tracy with his hat on in a way that convinces me that Tracy is actually wearing a hat. The second issue is more of the same—but moreso in wild composition—as Tracy battles the Brow and Pruneface and a new criminal, Broccoli Rabe. He also picks up an African-American sidekick named “Bricks” Walker because of his brick-sized hands. (And Oeming is great on hands.)

Quotes & Mots For nearly a century, Turkey has oppressed the Kurds, who make up nearly a fifth of its population of 80 million. And the Turkish prez is one of the Trumpet’s best buddies.

ANNIVERSARIES This year seems to be an anniversary year for dozens of events. It’s the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo Da Vinci, who died in France, oddly, not in Italy, his native country. “Bonanza,” which debuted 60 years ago on September 12, was the first Western to be televised in color and lasted 14 seasons, making it the longest lasting tv Western after “Gunsmoke.” The stars of “Bonanza,” the Cartwrights, were unlucky at love: Ben (Loren Greene) was three times a widower, and his sons didn’t fare much better: their wives or fiancees regularly died or ran off. Little Joe (Michael Landon) proposed to 11 women, four of whom died. They were luckier with their six-shooters: Ben and his three sons killed 170 owlhoots—Joe leading the pack with 67 solo kills and he had help with four more. Is it any wonder we’re a gun-tootin’ shootin’culture.

TRUMPERIES More Antics and Idiocies of Our Self-Championing Leader A MONTH DOES NOT GO BY without the Trumpet getting himself on the cover of one sort of magazine or another. This month, however, we focus on comicbook manifestations of His Assholiness.

Our first exhibit dips into the past for a Mad cover with Alfred E. Neuman imitating Picasso or some other master of abstraction, wherein the Trumpet is abstracted into high comedy, his natural habitat. And then, right next to that, a vivid contrast: Fred Ray’s classic Tomahawk in an actual heroic pose, just so we don’t forget in the Age of Trump, what an actual hero looks like. (I just picked up this comicbook at a recent comic con and I like it so much that I had to use it somewhere in Rancid Raves, so I manufactured a reason herewith.) The next, adjacent, visual aid gets us to the heart of the Trumperies this time—his appearance as a superhero on the covers of one-shot comicbooks. Pondering these masterworks, we can easily realize how appropriate it is that the Trumpet should be the star of four-color heroics. He seems, in fact, to be conjured up expressly for this purpose. The stories within are somewhat less masterfully achieved than the covers. Oh, there are plenty of pictures of the bare-chested muscled Trumpet, but the stories themselves are scarcely more than page after page of pokes at Trumpian mannerisms and misfits. In one issue, he goes on a diet, grows muscles and talks like the Hulk, making references to North Korea, habitual lying, and friendship with Putin. Then he has a fight with Putin who’s wearing superhero togs. In another title, walls are the chief preoccupation. Barack Panther knocks down a wall, Trump arrives and objects, eats Cheetos and swells up like Hulk, and yells “you’re fired.” In another misadventure, Ms Maralago, also a supperhero, sprinkles covfefe dusk. Lots of one-page pinup-style pix throughout these books; even two-page spreads depicting giant bare-chested Hulk Trump. Our last illustration (with Trump at a desk in the Oval Office) is extracted from a somewhat less extravagant adventure. All in good fun, right? Fun to draw, but so exaggerated are the manifestations of Trump in real life that putting him in a comicbook story seems a letdown. The

Trumpet’s trumperies are also, as always, the subject of editoonists lavish

attentions. And we’ve included a sampling, beginning at the upper left of our

first exhibit. Next around the clock is Dave Granlund’s concoction. Again, the speeches directly quote Trump; and the image of him in a straight jacket and padded cell creates a different reality, one more in the spirit of the idiocies he’s uttering. Below Granlund, Clay Bennett works one of Trump’s more sensational utterances—the one about shooting someone on Fifth Avenue and getting away with it because his supporters are so steeped in blind, obedient loyalty to him. The casualties at Trump’s hands have heaped up sensationally over the years; they include the Statue of Lady Liberty and Lady Justice. But, as we can tell from the morning’s tweets, Trump’s still alive and blurting things out. At the lower left, Jim Morin’s portrait of the Trumpet reeks of the Prez’s criminality—his distorted facial features and his growl about the hoax that everyone knows about. Continuing

in our gallery of Trumpet portraits, Daryl Cagle starts us off in the

next exhibit with a classic image. Tom Toles takes up the topic of Trump’s tax returns, suggesting that we’ve already seen enough of Trump. We don’t need to see his returns: we’ve seen him stripped of all pretense. Morin returns with a visualization of that famed axiom about throwing your enemies “under the bus.” Judging from Morin’s picture, Trump has more enemies than a bus can readily accommodate. But enough Trumperies. Onward, to the real stuff.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy THE

IMPENDING IMPEACHMENT has been all over the news for the last month. The New

Republic magazine is the first that I’m aware of to demand the Trumpet’s

impeachment on its cover. Inside, the magazine begins a 13-page article explaining their decision with another full-page text indictment of Trump (on the right in our visual aid). The New Republic then sets forth three Articles of Impeachment, one more than the House of Representatives voted for. Article I cites Trump’s “violation of his constitutional oath to execute faithfully the Office of President ... by employing the powers of the Office to advance his own political interests rather than the interests of the nation.” Article II is about Trump’s obstruction of justice. Article III accuses him of “enriching himself in violation of the Foreign Emoluments Clause” of the Constitution. “President Trump has repeatedly made it clear that he views the Presidency as a tool to benefit himself rather than the American people.” In violating the Constitution, Trump has been “depriving the American people of assurance that when he makes critical foreign policy and national security decisions, he is doing so with undivided loyalty.” The portrait of Trump that emerges during the 13-page examination is that of exactly the sort of person that the framers of the Constitution feared might get himself into the Presidency—and then behave like a reigning monarch, above the law. The article also explains what is meant by “high crimes and misdemeanors”: “offenses which are rather obviously wrong, whether or not ‘criminal,’ and which so seriously threaten the order of political society as to make pestilent and dangerous the continuance in power of their perpetrator.” Sounds like the Trumpet to me. Even without the formality of a trial, the testimony of witnesses has established that the Trumpet in his conduct towards the president of Ukraine is guilty of bribery, extortion, and usurpation of Congress’s power of the purse. (He withheld the duly appropriated payment of military aid funds to Ukraine until that country’s President Volodymyr Zelensky would announce an investigation of Biden corruption; if that’s not extortion, then it’s bribery. That Trump eventually released the money and Zelensky never announced an investigation are immaterial facts: in the attempt, Trump is guilty.) These are crimes. Moreover, he abused his office and violated his oath. Relying upon the status and power of the Presidency of the United States, he sought personal political gain rather than the welfare of his country (which is what he’s supposed to be doing in the conduct of his office). These are “high misdemeanors.” And that’s not all. He is clearly guilty of obstruction and contempt of Congress. Because most of the White House staff has obeyed his order not to testify before a legitimately constituted investigative Congressional committee, we may safely draw a negative inference from their refusal to show up: what they would testify to would be damaging to the Trumpet. So he’s covering up as well as obstructing Congress. What we have in the life and conduct of Trump is part of a pattern of lawless behavior not an isolated incident on the telephone to Zelensky. Trump has disregarded law whenever obeying it would inconvenience him in the conduct of his business or personal life.

ON HIS TELECAST “The Last Word” on November 21, Lawrence O’Donnell read from a communique sent to him by director Barry Levison, who, in a fine-tuned rant, asked the one question no one has yet asked of Trump’s behavior. Actually, he asked a series of questions, beginning: How is it possible that Trump was looking into corruption in Ukraine [as Republicons allege]? Suddenly, he is a crime fighter? Has he ever sought to end corruption anywhere at any time in his life? Over the years, he has been found guilty of stealing from his own charity, running a fake university and taking money from people who believe in him, and paying off women because of his sexually aggressive behavior. Now out of the blue, he wants to clear up corruption in Ukraine? Not in Russia— where Putin has killed off his opposition players, poisoning them in far off countries? Trump has no real problem with the Saudi prince MBS having his butchers chop up a Washington Post reporter? Not a real problem? Turkey’s aggression against the Kurds—not a big problem? But corruption in Ukraine—that needs to change. Are we supposed to believe this? Donald Trump wants to clean up corruption in Ukraine, starting with Biden’s son? The Democrats have not yet emphasized this absurdity at the heart of the Republican defense of Trump, saying it wasn’t Biden’s son’s corruption that was at the heart of Trump’s “favor” but the general, over-all corruption in Ukraine. Sorry: it won’t wash. And even if it washed, it doesn’t matter. Trump is guilty of precisely the behavior this country’s Founders sought to guard against when writing the Constitution: he acts like a monarch, above the law, and after a century or so of British rule, the American colonists wanted no more of that. And we don’t want any of it either. But that doesn’t stop the nation’s editoonists, who found themselves nearly overwhelmed with possibilities for cartoons in an unending flood of impeachment news. (Trump is also insane—as fully demonstrated in his December 16 letter to Speaker Nancy Pelosi.)

EDITOONS

ON THE TOPIC of Impeachment scarcely approach the intellectual maneuvers of the New Republic’s valuable essay. But they capture some of the moments and

impulses day-to-day. GOP denial goes on, unabated. Michael Luckovich takes it a step further: the Trumpet can’t have his hands in the cookie jar because, as evident in the picture, his whole body is in there, skimming for himself. So the Pachyderm can be entirely candid in saying Trump’s hands aren’t in the cookie jar. Tom Toles shows us the “Impeachment Debate.” No debate is possible if one of the debaters declines to use any evidence. Trump’s defenders have resorted throughout to denial rather than facts. “Schmevidence.” And the little Toles-man in the bottom right corner takes a shot at the news media, which, he says, “will report these as roughly equivalent.” Ouch. At the bottom left, Jim Margulies offers an apt image. Like the ostrich of legend and lore, the Pachyderm has his head in the ground where he can’t see anything. And then he implies that the “surface” (which he can’t see) is fraught with error. Down where he is, his head buried in the ground, he can’t see anything. We’re back where we started. And

when the righteous GOP stormed the committee meeting room where closed-door

hearings were being conducted, Bill Bramhall shows us in the next array

that they behaved exactly like a street mob, assaulting their surroundings with

pitchforks and torches—the ancient image of mob rule by fear. The purpose of this department of Rancid Raves is to examine the ways editoonists deploy images to convey their opinions thereby enriching our appreciation of the form. Bramhall’s cartoon affords us a useful opportunity to demonstrate our purpose. Bramhall compares two images. At the chalkboard, the Democrat jackass makes the case for impeachment with diagrams of facts; the Pachyderm makes his case by scraping his nails across the chalkboard, creating a screeching sound. To no avail, of course. All that we can acknowledge is a screeching sound. No discernible details. And the screeching assaults our ears and makes us turn away. So much for the effectiveness of the GOP method. Steve Sack offers an overview of the processes in use comparing two images. On the left, an orderly meeting; on the left, a screaming Trumpet, calling names. Nick Anderson brings the Fifth Avenue metaphor back again: whatever the results of the Trumpet shooting somebody on a major thoroughfare in New York City, those results are completely incongruous. Shoot somebody and arrest Hunter Biden. The latter does not follow logically from the former, which is another way of saying the Trumpet is getting away with it. Again. Dana

Summers in our next visual aid makes a case for the Republicon side of the

dispute. I include this editoon in a misguided attempt to display my impartiality and objectivity. But, like Mitch McConnell, I’m scarcely impartial. But you knew that, right? This maneuver permits me to rail on, briefly, about a standard ploy of the Pachyderm this season. The GOP (and Trump) maintain that the Democrats want to undo the results of the 2016 Election because they lost. But they didn’t lose: they actually won the vote but lost in the Electoral College, a cumbersome and frustrating invention of the 18th century which ought to be abandoned as no longer applicable in the Age of the Internet and instantaneous communication. That conviction, however, has little to do with the Donkey’s desire to rid the American democracy of a would-be monarch. Lisa Benson offers a great image for the present state of the impeachment process. The House’s impeachment progress is headed toward the machinations of a trial in the Senate, which they will no more prevail over than the ship Lisa depicts will survive an encounter with that iceberg. Meanwhile, waiting in the Senate, is majority leader Mitch McConnell, who Ed Wexler depicts as sitting, without acting, on 250 “bipartisan” bills sent to the Senate by the House. (The number is constantly changing: at last report, there were 300 bills languishing; 270 of them, bipartisan.) Inaction is McConnell’s specialty. And he promises to put his dubious skill to work once the Impeachment reaches the Senate: he wants to push it through as quickly as possible; no witnesses. Get it done. The conclusion is foregone. Trump will not be ousted. Why waste more time and money? But the Trumpet wants witnesses to be called. They will be chosen to polish his image. He’s thinking of history. (Just as he claims to be thinking of history by sending a wildly ranting letter to Nancy Pelosi, urging her to abandon the whole sordid scheme. Right.) My favorite on this page is Bob Englehart’s picture of a relaxing Trumpet, playing with his cellphone. He’s apparently just returned from that surprise Saturday visit to his doctor for an examination a few weeks ago. The exam produced no information. No headlines. What’s next? Trump’s answer is pure Trump: “Fake a heart attack.” Ha. Just as he fakes everything else.

THE

PLIGHT of the Republicon Party during all of Trump’s charade is not, I would

think, a matter for joyful celebration. Bill Bramhall offers an explanation with a deft and wonderfully cute metaphor. All the elephants are drinking the kool-aid, a metaphor for sharing, however dubious the outcome, the drink the leader has concocted for them. They are all united in their thirst and quenching it. This is an old reference to the crazed religious enthusiast named Jim Jones who persuaded all his followers to drink poisoned kool-aid. And then Michael Luckovich offers another explanation for the docile Pachyderm behavior. Surrounded by the Trumpet’s most disastrous error, deserting the Kurds, they take comfort in what they’ve accomplished—conservative judges on federal benches and more money in their pockets. To hell with the Kurds. The

Trumpet’s latest venture into foreign affairs, his meeting with NATO

representatives on the 70th anniversary of the organization’s

founding, produced mixed results. The Trumpet was also miffed that Time magazine didn’t choose him as Person of the Year. God knows, he’d done enough to attract their attention. But instead, Time chose Greta Thunberg, a sixteen-year-old Swede who embodied protest against nations of adults doing nothing about climate change. Time seems to me to have slipped a cog here. Or, more likely, they’ve changed the criteria by which they choose the Person of the Year. Used to be the criteria were fairly simple: that person who, for good or ill, had the most impact on the year’s news. So in1941, Japan’s Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was Man of the Year for masterminding the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7. Joseph Stalin was named twice in rapid succession,1939 and 1942, and Nikita Krushchev in 1957, but it was Charles de Gaulle, savior of France, the next year and the year after that, Dwight Eisenhower (who’d been Man of the Year at least twice before). By that criteria, Trump is the clear winner. He was in the news nearly every day; and at least once a week, he’d do something that would affect the nation or the world (for good or ill). But Time probably doesn’t want to give him any more bragging rites than he presently enjoys. So they chose Greta, probably as a symbol of the Youth of the World protesting the incompetence of their elders. Pat Bagley’s portrait of Greta with Time looming behind depicts her overshadowing the tiny Trump in the corner, working his cellphone and complaining that he wasn’t picked. Chris Britt goes in another direction and shows us the cover of Time would look like had the magazine picked the Trumpet—“Criminal of the Year,” “Liar, Cheater, Bully, Racist.” Those attributes, indeed, seem to suit him.

FOREIGN

AFFAIRS is our topic next. Daryl Cagle depicts the German Shepherd hero of the slaying of ISIS leader Abu al-Baghdadi, whom Trump dubbed “the wonderful dog” (name not yet declassified). The animal was slightly wounded, so, of course, Cagle puts him in a hospital bed like any other American wounded soldier. Nick Anderson sides with the Kurds at their recent neglect at the hands of the Trumpet: as the picture shows, if the Kurds were oil-rich, they’d get protection from the U.S. One family is shown is tied to the oil pump which they seek out for protection. Bob Gorrell gives us a progress report on the War in Afghanistan. A report just made public shows that government and military officials have been lying to the American public about Afghanistan, claiming things are better there than they are. As Gorrell’s familiar shape as the “I” in the middle of the name reminds us, it’s Vietnam all over again. The

Democrats are still running for Prez. Gary Varvel must’ve had fun

caricaturing all of them for his cartoon at the upper left. Sure, as soon as the medical profession decides to accept a 70% cut in income. Why aren’t they talking about real problems instead of blue-sky stuff? Here are a few that I wish were top priorities. Veterans’ Administration. Better care for vets. For that, we need more money for doctors so they won’t opt for private practice. Student loans. Do away with student loans altogether by reducing the cost of college. College is the biggest unregulated racket in the country. Tuition fees go in disproportionate measure to “expert” researchers who never do any teaching. Homelessness. It’s a national disgrace that the wealthiest country in the world has such a large homeless population. Thank goodness some judge ruled that homeless people who have to sleep outdoors because there’s no other choice can’t be arrested or criminalized in any way. Big Pharma. What’s the cry? If you cut our profits, we can’t afford to do research any more. Oh, sure. C’mon: in a capitalist society, if there’s a way to make money, we’ll find it. And medical research is a way to make money. Research won’t stop. Immigration. People want to come to the “land of the free.” We can’t stop them. But the process for asylum-seekers must be streamlined so they can be free to wander the country as soon as possible. Putting them in pens isn’t right. David Hitch, at least, shares my view that so much campaign rhetoric and so many themes of politicians running for office are so much “flapdoodle, codswallop, piffle and traces of leg hair.” Hitch’s crisp black-and-white drawings are a treat to watch. I’ve only just discovered him. And I’m delighted. Next around the clock, Nate Beeler assesses Joe Biden’s progress on the campaign trail. By detaching Biden’s head from his body, Beeler gives another meaning to being “a head in the polls.” Gaffes, yes. Oh—and are those loose screws on the ground around Biden’s head? Tom Toles gets a couple Democrat jackasses together to assess the field of Democrat candidates. None of them may be “perfect,” but the Pachyderm points out that having settled on one candidate is no guarantee of perfection. It takes two panels to pull this off. And Matt Davies uses two panels to present his view of the chances of any

government taking action on climate change. The little girl (Greta? Or one of

her surrogates?) has listed meaningful horrors, but grown-ups know better:

rather than disrupt the economy, they’ll put up with rising oceans. Jim Morin strikes a blow for stricter gun laws with a picture of a bunch of kids returning home from school, responding to their mother’s question with a recitation of gun and other violence that has taken place that day at school. “No biggie,” says one, ironically no doubt. Slightly off-topic, Daryl Cagle constructs a vivid picture of police life in these days of police violence. The miscreant at the left fears the cop’s club; but the cop fears the cell-phone photo that will convict him. And then we have NRA’s CEO, Wayne LaPierre, explaining to the Trumpet why no action is needed after another day’s mass shooting. It’s a “common occurrence.” “Nothing out of the ordinary.” That’s David Granlund’s cartoon, I believe; his signature got lost in the editing at the publication from which I siphoned off the cartoon.

IN

OUR NEXT VISUAL AID, Pat Bagley has drawn a haunting picture of the

world distressed that a third of the world’s birds have disappeared. And I just read this in the Person of the Year issue of Time: in his final years, Charles Lindbergh, Time’s first Person of the Year (who was, then, a “Man” of the Year), became an environmentalist. “If I had to choose,” he said, “I would rather have birds than airplanes.” John Darkow gets at two of my pet peeves into a single pictorial lecture. Homelessness and veterans in need. Of course, we’re grateful for their service—until the service is completed; then it’s de riguerur to forget them. Then Daryl Cagle is back with another of his silent sermons. In his acute picture of a national conversation about race, the races are separated and are not talking to each other. Not a way to get anywhere. Steve Sack looks at the Hong Kong protestation, and finds visual kinship with another protest in Tiananmen Square thirty years ago. It, too, was about democracy. For

our last lecture, we get back to the Trumpet, who, adept at creating

controversy with himself at the center of it, is never much out of our minds

these days. Trump is also in favor of reducing food stamp allowances, particularly for those who don’t work. Another cartoonist elsewhere had a food stamp recipient respond by saying, “I work.” Yeah: but they don’t earn enough to live on, hence, food stamps. But Trump’s solution is to take food stamps away. What’ll that solve? Maybe the crime rate will go up. Finall, here’s Adam Zyglis, commenting on Trump’s weighing in on behalf of a marine who’d killed a captive and then had his photo taken with the corpse. This was a violation of good manners and military decorum. But Trump negated all the punishments, restored the guy’s rank and special ops pin. Without the military’s insistence on good (i.e., humane) behavior by our troops, we might lose that behavior. War is savage enough even when controlled. Without any semblance of control, we’re back in the middle ages. But maybe the Trumpet prefers it there. After all, he’s insane.

PERSIFLAGE & FURBELOWS When Gayle Novak, the 2018 Ms. Senior America, died on October 13, 2019, her obit included her musings about her life, which, she said, had been like a melody: “There have been high notes and there have been low notes ... yet I learned to persevere to the end of each song. I am grateful for the music, and I am looking forward to the rhapsodies yet to come.” Her death, at just 61, was accidental. Feeling congested at bedtime, she took Theraflu with her Ambien. And died as a result. But the poetry of her musical metaphor lives on.

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged “News” Institution SHEPARD SMITH, who did the evening news (as opposed to the evening opinion) broadcast at Fox News since the launch of the network in 1996, resigned in October, removing thereby the network’s last claim to any sort of journalistic objectivity. Smith stood for truthful analysis and fact checking. In his absence, Fox is the simply Trumpet’s personal propaganda machine. For years, Fox management pointed to the highly respected Smith whenever the network was accused of being a “condit for fervid conservative agitprop.” Smith was, in short, an actual journalist. Smith insists he left his $15 million-a-year contract on his own, without being pushed. He had long endured a simmering tension with the opinion branch, and that came to a boil once the network fell into line with Trump. Last month, Tucker Carlson called Smith “a partisan” for supporting the notion that soliciting election help from a foreign power is a crime. When the network didn’t back Smith, he decided that “he had simply had enough.” In his sign-off, Smith alluded to his reasons for leaving. “Even in our currently polarized nation,’ he said, “it’s my hope that the facts will win the day. That the truth will always matter. That journalism and journalists will thrive.” Just not on Fox.

READ & RELISH “Beauty is only skin deep, but ugly goes clear to the bone.”—Dorothy Parker

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping BLONDIE

is perching on the cusp of an anniversary: this year, the strip is 89 years

old. And one of the things remarkable about the strip is that it has retained

its appearance—its drawing style and visual mannerisms—almost intact for its

near-9-decade run. That would suggest that the strip is monotonous, boring, and

stultifying. But it isn’t. It has somehow retained its essential liveliness and

attraction. Even more remarkable is how satisfying it is to study the strip and

appreciate its various low-key achievements. In the strip atop the lineup in the accompanying visual aid, we have a recurring situation between Dagwood and his barber about Dagwood’s celebrated cowlicks. They have a conversation about his hair every other month or so. It’s a regular routine. Fifty years ago, I doubt (without checking) that the creators of the strip would have joked about such a thing. Such gags take Dagwood and his hair out of their natural habitat, the world of the comic strip, and make them cast characters instead of the real people they otherwise seem to be in the world of their comic strip. In the next strip down the line, notice the “take” lines at the heads of Dagwood and Blondie as they react to the waiter’s remark. The lines indicate a very slight motion of the heads. Very restrained. Below that strip is one of the many in which Dagwood finishes the day’s adventure by looking out at us. He’s breaking the fourth wall. He clearly knows we’re out here. Silently, he looks askance at us as if saying: Have you ever seen such silliness. Usually, he’s silent when he stares out at us; here, he even talks to us. We are, in effect, fellow cast members in the strip. In the next strip, John Marshall (the artist of record) has drawn almost an entire automobile. Remarkable simple details. In the old days, automobiles were not depicted in such a full-scale manner. There might be a window that we look into in order to see and hear a conversation among Dagwood’s car pool mates. But we didn’t see the whole car. But these days, any modification in routine is possible. Finally, to drive home a contention about the strip’s enduring visual appearance, Dagwood’s shoes have been rendered in the manner we see here for almost all of the strip’s nearly 90 years. Other unchanging elements here: Blondie’s hair-do (always the same), the button in the middle of Dagwood’s shirtfront, and Daisy the family dog always following her masters around. I’m not sure the gag makes sense, though. Tootsie is saying Herb takes no more time to buy a shoe than Dagwood does. Where’s the laugh in that? Now go back and look at all the visual detail in nearly every panel of every strip. As a part of this impressive drawing exercise, notice that the characters are almost always depicted at full length. No shortcutting by showing them only from the waist up. A remarkable comic strip, as I said.

NEXT,

WE HAVE OUR USUAL FORAY into the once verboten potty humor that has begun to

infect newspaper comic strips, thereby proclaiming a fresh new liberty for us

all. In Jef Mallett’s Frazz, “hot dog flatulence” is a somewhat more dignified version of “toot” simply because it has more syllables. But in Mallett’s Sunday Frazz, we have in full color perhaps the most elaborate verbal construction I’ve seen yet for permitting a character to use the expression “breaking wind,” a timeless euphemism for “farting.” Mallett

is a dedicated cyclist; but that doesn’t explain anything here except perhaps

that his experience breaking through the wind resistance prompted the

penultimate speech balloon. If so—whatever—Mallett has won my undying gratitude

for arranging for this And for the lead sled dog notion, too. Every other dog in harness is looking at another dog’s asshole, right? SOMETIMES we look for peaceful simplicity and find a quiet message as we sit back and enjoy the mild comedy of a picture. Patrick McDonnell did some in this vein last summer.In the top strip, he celebrated his strip’s 25th anniversary with a simple roll call of Mutts’ cast. Next down the page Earl the dog and Mooch the cat go for a quiet cruise. But their enjoyment, while undisturbed by what we see below the surface, masks a message about how we’re treating our environment. Then we visit the jungle and see more than one king. A quiet, delicate scene for us to savor. Finally, McDonnell tips the strip on its side to emphasize the length of the giraffe’s neck, and Mooch passes along a little of his feline grasp of the nature of things.

POPEYE IS 90 Popeye is 90 this year: his anniversary, strictly speaking, was last January. But as we pause to celebrate the occasion, we must celebrate, too, the strip in which the one-eyed sailor made his debut. The strip was Thimble Theatre, and it first appeared 100 years ago this month. Yup: it ran for 10 years without Popeye. Thimble Theatre was supposed to parody movies and stage plays, and Segar cast the strip with "actors" who would take parts in the lampoon productions: Willy Wormwood, a moustache-twirling villain akin to Desperate Desmond; the pure and simple heroine with a hysterical scream in her throat, Olive Oyl; and her stalwart (if not overly smart) boyfriend, Harold Hamgravy (who would soon lose his first name and become Ham Gravy). But after a few short weeks of daily or weekly productions along the intended line, Segar abandoned the original plan and focused instead on his actors and their real (as opposed to "reel") adventures. And with the introduction shortly thereafter of Olive's brother, the pint-sized Castor Oyl, the strip found its footing. Castor Oyl was, in Segar's words, "Olive's foolish brother, not exactly half-witted but exceedingly dumb. Just this dumb: when Olive's pet duck fell into a deep hole and no one could extricate it, Castor came by with a water hose and floated the duck to the top. He was clever in his own inimitable way. He even invented coal that would last forever, and he fireproofed safety dynamite so it couldn't explode." But Castor wasn't merely kooky. He was maniacally ambitious. He wanted money and success, women and power. Having almost no special abilities that would enable him to achieve these ends, he pursued his aims with no more than single-minded, dogged determination. As an obsessive seeker after wealth and power, Castor was the perfect 1920s protagonist— a caricature of the materialistic go-getter, the icon of the age. He soon emerged as the star of the strip. Castor's greedy ambitions motivated the strip throughout the decade, one get-rich-quick scheme after another. Daily installments ended with comic punchlines, but the story of one day's installment did not end with the last panel's laugh: Segar strung the dailies together, stretching stories out for a week or more. Soon the stories meandered on for months, but such was Segar's comic inventiveness that people enjoyed the ramble. One of Segar's devices for creating suspense and maintaining interestingly comic continuity was to introduce wildly eccentric characters into his stories. The strip would focus for days— even weeks— on the Dickensian quirks and foibles of some minor character. As this character kept us entertained, Segar could, at the same time, inch his story along, day by day. Popeye was one of these characters. In one of his get-rich-quick plans, Castor turns gambler. But not before he has a sure-fire system: his uncle has given him a Whiffle Hen, a good luck bird that guarantees winning at games of chance for anyone who rubs the three hairs on the bird's head. Castor decides to take the Whiffle Hen to an offshore gambling hell called Dice Island and use the bird to fleece the gamblers. Castor buys a boat, but the boat has no crew, so Castor goes in search of one. And that's what he hires: one–namely, Popeye. On January 17, 1929 (just ten days after Tarzan and Buck Rogers debuted), Castor approaches a one-eyed tattooed barnacle of a seadog with a corn-cob pipe standing on the dock, and he hires him. "Hey there!" says Castor, "Are you a sailor?" Confounded by Castor's inability to perceive his occupation from his nautical garb and demeanor, the sailor replies with biting sarcasm: "Ja think I'm a cowboy?" "Okay—

you're hired," says Castor. For the rest of Popeye’s origins, consult Harv’s Hindsight for March 2004. Here, we prolong our festivities by examining Popeye’s obsession with spinach.

IN POPEYE, readers saw a force for good that could not be defeated. And because he represented many of the country's traditional values, his triumph in every encounter with evil reassured readers: if Popeye could win, those values were not bankrupt. However battered the economic and social institutions of the nation during the Great Depression, the fundamental values of its people remained viable. Thus, in this pragmatic comic sailor's victories, Americans found immediate comfort and, perhaps, a prophecy: surely his successes foreshadowed the eventual return to happiness and prosperity of the society that subscribed to the time-tested values of small-town America. Segar showed masterful skill in keeping his readership engaged with this concoction of comedy and morality, but it is likely that he enjoyed assistance from an unexpected quarter in initially enlisting the attention of much of his audience. According to the late Bill Blackbeard, curator (and founder) of the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art, Thimble Theatre was not a widely published comic strip until the mid-thirties. Until then, Blackbeard says, it ran almost exclusively in Hearst papers. Yet by the end of the decade, Popeye was as widely celebrated a popular icon as Mickey Mouse. The circulation of the strip clearly increased dramatically during the latter part of the thirties. Much of the credit for that growth can be assigned to Segar's genius in the practice of his craft, but some of the impetus to increase may be found in another medium altogether— the animated cartoon. The first Popeye cartoon from the Fleischer Studios appeared in the summer of 1933, more than four years after Popeye’s arrival in the comic strip. If Blackbeard is correct about the limited circulation of the strip at the time (and his experience in searching out comic strips in thousands of old newspapers suggests strenuously that he is), then it is probable that it was the Fleischer Popeye that introduced the character to much of the American public. And Americans liked what they saw on the screen. Popeye was an immediate hit, and the Fleischer brothers knew what to do with a hit: they produced more Popeye cartoons as fast as they could. Beginning in 1934, Fleischer Studios cranked out a Popeye cartoon every month for the next nine years. Cartoons starring either Popeye or Betty Boop comprised virtually the entire output of the studio for the rest of the decade. The comic strip had surely been growing in circulation before the Fleischers started producing their Popeye cartoons: the Fleischers would not have been interested in such a property had it not demonstrated some kind of appeal. But the animated cartoons must have accelerated the dissemination of the strip. They catapulted Popeye smack into the public eye all across the nation— even in places where he didn't appear in the newspaper. And the immense popularity of the cartoons created a demand for more Popeye. Salesmen from King Features undoubtedly moved with alacrity to supply that demand with the syndicated Popeye, and the client list of newspapers running Segar's strip increased apace. After that, it was up to Segar. And he proved equal to the challenge: once before the reading public on the funny pages of the nation's newspapers, Segar captured and held the interest and loyalty of his readers. Popeye's popularity was scarcely due entirely to the Fleischers. The Popeye on the screen attracted public notice, but it was the Popeye in the papers that sustained it. Segar's Popeye and Fleischer's are not exactly the same character. They are not identical. But they are so similar that the differences are complementary rather than contradictory. For one thing, the animated cartoons champion spinach as the source of Popeye's strength. Popeye's passion for spinach is supposedly born out of one of history's easiest mathematical errors, according to dailymail.co.uk.com. In 1870, German chemist Erich von Wolf was researching the amount of iron in spinach and other green vegetables. When recording his findings in a new notebook, he misplaced a decimal point, making the iron content in spinach ten times more generous than in reality. While von Wolf actually found out that there are just 3.5 milligrams of iron in a 100g serving of spinach, the accepted number became 35 milligrams thanks to his mistake. From that error arose the popular misconception that spinach, exceptionally high in iron, makes the body stronger. If that were true, eating a generous serving of spinach would be comparable to munching on a small piece of paper clip. Popeye’s animated cartoon creators, casting about, no doubt, for some novelty for the character, decided that spinach’s reputed ability to foster great strength would be the secret to Popeye’s strength. Every time he needed a burst of strength, he’d eat a can of spinach. It is believed that Popeye is responsible for boosting consumption of spinach in the U.S. by a third. But in his newspaper comic strip incarnation, Popeye ate spinach only occasionally and evidently didn’t like it because he never made a habit of consuming it. Still, the Fleischers may have picked spinach because Segar once used it. Segar had forced Popeye to consume a bowl of spinach on February 28, 1932, in preparation for a encounter with an iron-jawed braggart; the von Wolf factor supposedly gave Popeye enough iron to overpower the guy. And that week's episode concludes with a note from Popeye to mothers everywhere: "Please tell yer youngstirs I said they should eat spinach an' vegebles on account of I wants ’em to be strong and helthy." This may have been the origin of the spinach mythology that was taken up and magnified in the animated cartoons. But the erroneously high iron-content of the leafy vegetable doubtless established its viability as a strength enhancer. Spinach figured more often in the strip's stories after the advent of the animated Popeye, but the invigorating vegetable was seldom as integral to Popeye's success in the strip as it was in the Fleischer cartoons. Segar's forte in the daily strip continuity was prolonging Popeye's idiotic predicaments; Popeye punched people out only after agonizing delay. On Sundays, the sailor took up prize fighting as an avocation and was often in the ring, socking his opponents. In the movies, however, Popeye's very existence was defined by his pugilistic feat aided by spinach. And it was the animated Popeye that made Popeye famous, not Segar’s strip. But it’s the strip’s anniversary that we’re celebrating here this month. And the National Cartoonists Society joined in the festivities. NCS celebrated the Popeye’s jubilee with an auction of original artwork by its members that will benefit the NCS Foundation. Last winter, in the days leading up to the inaugural NCSFest in Huntington Beach, California, NCS members were asked to create original works of art in tribute to Popeye and his cast of characters for a special group exhibition at the Huntington Beach Art Center. The response was overwhelming and the exhibit was one of the highlights of the festival. Members were also asked if they would be willing to donate their original art for this special auction, and many agreed. Among the artists who donated original Popeye pieces are Patrick McDonnell, Jim Davis, Garry Trudeau, Lynn Johnston, Bobby London, Jeff Keane, Luke McGarry, Ann Telnaes, Mike Peters, Rick Kirkman, Jerry Scott, Jim Borgman, and many, many more! To complete our celebration here in Rancid Raves, we’re reproducing some of the Popeye images herewith.