|

|||||||||||||||

|

Opus 396B (September 19, 2019). Open Access Month continues for just a couple more days—long enough for you to enjoy our celebration of Stonewall Inn’s 50th Anniversary with a review of a gay graphic novel in this posting of Rancid Raves. Art Spiegelman’s history of Marvel Comics’ Golden Age is also featured, as is my reaction. And we have reviews of first issues of a couple sterling comicbooks, a dozen or so editoons on the events of the last two weeks—and more, much more, as you can tell by rolling an eyeball over the ensuing list of what’s here, by department, in order—:

Editor’s Note: The longest articles are marked with an asterisk (*) to help you decide which ones to visit right away and which ones to postpone to another day. Excessively long pieces get two asterisks (**).

NOUS R US Fillmore No More: Duck Strip Dropped Alan More No More Watchmen on TV Drag Show Gets Nasty Protest Feige Off Spider-Man Flicks A New Wimp Book Death in Funky Winkerbean Cute Chick and Fat Broad Get Names Infowars Loses Pepe and $15,000 Pepe Welcomed in Hong Kong Jews Invented Superman To Fight Anti-Semitism

ODDS & ADDENDA Frazz Booze DC’s Bad Covers: Destroy or Collect?

**GUN CONTROL The Happy Harv’s Fulmination

EDITOONERY On Fires in the Amazon Trump’s Gaffe with Dorian and Alabama 9/11 Remembrances Third Democrat Prez Debate —And More

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews Of—: Space Bandits Wyrd

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Mutts at Sandy Eggo Con Cranky Assessment of Funky Winkerbean Smokey Bear Needs a Shirt; Donald Duck, Some Pants

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Loose Ends, Nos. 1-4

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews & Coming Attractions Garden of the Flesh Life and Times of Gardner Fox Chaykin’s Blackhawk Returns in Reprint Volume Ditko’s Mr. A to be Collected

BOOK REVIEW Long Opinionated about—: Mad No.9

**CELEBRATING STONEWALL INN’s 50th History of Stonewall Riots Review of Comrades, a Gay Graphic Novel

SPIEGELMAN WITHDRAWS *Essay on History of Marvel’s Golden Age Comics Jews Invented Superheroes to Fight Anti-Semitic Nazis **Harv’s Footnotes: Mild Disagreement

PASSIN’ THROUGH Lee Salem, Editor Extraordinaire

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of the News That Gives Us Fits

CONTROVERSIAL DUCK STRIP DROPPED The

San Diego Union-Tribune dropped the comic strip Mallard Fillmore for

using ‘hate speech.’ I saw this one coming when we posted the strip’s August 12

release in the Editoonery Department last time (Opus 396A). At the time, I was

tempted to say that strip would get its creator, Bruce Tinsley, in

trouble. And, sure enough, it did. In San Diego at least. The August 12 strip may not be anti-Semitic, but it is close enough. At the least, it is dangerous in these days fraught lately with violence directed at Jews. U-T readers e-mailed and phoned the paper to complain. It’s difficult to ascertain Tinsley’s intent in depicting Representative Ilhan Omar complaining about Trump insulting her—“Who does he think I am—a Jew?” Does Tinsley mean that racist anti-Semitic Trump is accustomed to insulting Jews? Not likely. Since Trump is determinedly a right wing-nut, Tinsley, a right wing-nut himself, probably wouldn’t attack the Trumpet. So what remains as a target? Omar herself. Tinsley has characterized her as a little thin-skinned in the strip for August 11, and he continues in what he believes is the same vein in August 12. But the word “Jew” screams out, calling attention to itself and to Jews in dubious tone of voice. “We don’t want hate speech in the Union-Tribune,” said Editor and Publisher Jeff Light, who belatedly decided that the strip was anti-Semitic. “Here’s a definition: targeting people, particularly marginalized people, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, color or sexual orientation. The Mallard Fillmore strip was a blatant violation. “In our news columns,” he continued, “we often have to cover upsetting events or ugly ideas. Then we face a dilemma about how much of the offending material to share with our readers. When does the harm from repeating hateful ideas or words outweigh the clarity that comes from complete, detailed reporting? We take these issues seriously. This is not something we will allow to be treated glibly or ironically on the comics pages.” Two emails from the readers’ rep seeking comment from the strip’s syndicate, King Features, went unanswered, reported Adrian Vore at the U-T. A description of Mallard Fillmore by King Features in 2009 to mark the strip’s 15th year said it “continues to be one of the most highly contentious and celebrated comic strips, providing a unique conservative viewpoint to the funny pages. Mallard Fillmore has been a lightning rod for controversy ever since its launch in June 1994.” The description is clearly intended to make the strip appear attractive to editors looking to add something to their comics page: it’s “celebrated” as well as being “highly contentious” with a “unique conservative viewpoint.” It’s uncertain what will replace the strip and when the last strip will appear, Vore said. “The comics pages are set up about a week in advance of their actual publication day.” Mallard Fillmore arrived at the U-T through the back door. The strip had been running in the North County Times, then owned by the U-T, and when Tribune Publishing acquired the U-T in May 2015, it consolidated the strips in both papers. Mallard Fillmore was dropped at the time, but some North County readers loudly objected. In response, the U-T conducted a poll on the comics. Almost 3,500 readers cast votes for their favorites, and Mallard Fillmore received enough votes to remain, although at the low end. It began in the U-T in July 2015. Over the years, said Vore, many U-T readers have indeed found the strip controversial. The August 12 strip received the most complaints in the five years the current readers’ rep has been at that desk. Editors throughout the newsroom also took calls and emails. “Using that language so callously when we have hate crime happening seemed so tone deaf to be insulting,” said Shana Charles, a Ph.D. in the department of public health at California State University Fullerton, who emailed the U-T. Charles said her mother in Sorrento Valley alerted her to the comic. “It’s playing with fire when there is violence in the air,” she told the U-T readers’ rep in a phone conversation, adding that the strip is “way too political for the funny pages.” Editor/Publisher Light said the two remaining strips that often deal with political themes, La Cucaracha and Doonesbury, will be moved under a political heading on the comics page.

MORE NO MORE Alan Moore is retiring, Sam Thielman reports at theguardian.com. “Alan Moore has promised that the (extremely late) final issue of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen will be his last comic, and his final contribution to an art form he utterly transformed, sometimes to his chagrin.” Moore’s work in the 1980s on Miracleman, a deconstruction of the superhero myth, inspired so many imitators to darken formerly kid-friendly heroes that Moore has apologised more than once for it, said Thielman, who goes on—: A brainy pop writer whose style veers between Stephen King and John le Carré, Moore’s influence can be felt everywhere – in our literature, on our screens, in our politics. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, quoted Watchmen’s Rorschach on Twitter, in response to reports that she was agitating the Democrats. (“I’m not locked up in here with YOU. You’re locked up in here with ME.”) Writers as diverse as China Miéville and Ta-Nehisi Coates have cited him as inspiration. HBO’s great post-Game of Thrones hope is yet another adaptation of Moore’s most popular book, Watchmen, which (co-authored with illustrator Dave Gibbons) has sold millions of copies since it was first published in 1987. He’s played himself on “The Simpsons,” seen his work adapted into a number of films – none very good – and even inspired an activist collective: the Anonymous group wear Guy Fawkes masks as a tribute to V, the anarchist hero of Moore’s and illustrator David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta. More is famous for his scripts, which go on at punishing length. They can run to hundreds of pages, describing every layer of background and every tertiary character.... Describing Batman’s home city to artist Brian Bolland in the script for The Killing Joke, Moore wrote: “The lower and seedier levels of Gotham are more inclined towards a territory somewhere between David Lynch and The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, all patches of rust and mould and hissing steam and damp, glistening alleyways. I imagine this strip as having an oppressively dark film noir feel to it, with a lot of unpleasantly tangible textures, such as you habitually render so delightfully, to give the whole thing a really intense feeling of palpable unease and craziness.” And Moore’s collaborators have always risen to his challenges, turning this overwriting into eye-popping set pieces. RCH: Alas, the movie version may not, as we see forthwith—:

And at Television’s Forthcoming Watchmen? HBO's series adaptation of Watchmen by David Lindelof has so far divided critical reaction. The first episode, the only part of the nine-episode season HBO made available to critics, introduces the story's ostensible protagonists: Tulsa's Police Force. And the enemy? asks Elanie McFarland at salon.com: “It’s a white supremacist organization whose members wear masks inspired by the iconic Watchmen character Rorschach.” That seems entirely foreign to Moore’s conception. Lindelof explained: “What, in 2019, is the equivalent of the nuclear standoff between the Russians and the United States?” he asked rhetorically during a press conference, referring to one of the key political flashpoints examined in the original comic. And he answered: “It just felt like it was undeniably race and policing in America.” Until the end of July when the press conference took place, HBO has kept the details of “Watchmen” cloaked in mystery, teasing audiences with disconnected snippets. Reporters assembled for HBO’s press conferences at the Television Critics Association’s summer press tour screened a preview of the first episode on the condition that we refrain from posting reviews until the drama’s scheduled premiere in October. RCH: But then, we have the review that we started with just above, which proves ...

MILE HIGH DRAG SHOW DRAWS NASTY PROTESTORS By Patricia Mastricolo at CBLDF (with a little tinkering by RCH) Since February, Mile High Comics in Denver, Colorado has been hosting an all-ages Drag Show one Sunday each month to raise money for a local scholarship fund. In addition to drawing crowds of fans interested in supporting the store and raising money for a local nonprofit, it has also drawn a crowd of protesters, including a group called Proud Boys, who the Southern Poverty Law Center has listed as a hate group. In reaction to the hatred shouted at attendees, a volunteer Parasol Patrol has been organized to shield people as they enter the Drag Show. Back in July, according to Mile High’s owner, Chuck Rozanski, in a post on the store’s website, the protestors at an event began to get out of hand, going out of their way to “provoke a confrontation.” There were only 18-20 protesters at that event, and nearly 50 volunteers for Parasol Patrol, plus two off duty Denver cops for security, and it still wasn’t enough to handle the volatile group. Said Rozanksi: “Suddenly (just as we were seemingly about to be overrun) fifteen Denver police officers materialized out of nowhere. They set up a picket line between our families and those awful bigots, frustrating those nasty people beyond words.” Rozanski, as his Drag alter ego Bettie Pages, came down (dressed tastefully for the evening in a lovely ivory gown with matching opera gloves) and stood shoulder to shoulder with the police in front of the store, to absorb the hatred being shouted by the protestors. Specifically worried about the children on their way to the event, Rozanski stood there for an hour listening to the nonsense, but wasn’t impressed, writing later on the Mile High blog, “Honestly, those people are dumber than rocks.” After that, protests escalated and drew a notable appearance by alt-right group Proud Boys. Proud Boys are a male-only group founded in 2016 that advocates political violence. Rozanski wrote: “Their militaristic attire, and the masks and hoods of several other protestors, absolutely appeared to be threatening.” Rozanski took to the blog and spoke about the night, noting that despite the 30-plus screaming, it was the most successful drag show to date, with over 400-plus happy attendees helping to raise nearly $3,000 for a local scholarship fund. Some of the real heroes that night were the 75-plus parents and friends who volunteered for the Parasol Patrol, where brightly colored umbrellas are used to help shield attendees from the noise and negativity being shouted at them. This Parasol Patrol was organized by Eli Bazan and Pasha Eve, and anyone interested in joining that volunteer group can learn more on Facebook. But, as Rozanski wrote, the Patrol isn’t a perfect fit for everyone: “Only apply if you can always maintain a sense of peaceful decorum, even under duress. We do not want anyone in our group to engage (or attack) the neo-Nazi, alt-Right, and Fundamentalist Christian protestors. As much as we may disagree with their nastiness and vile insults, their right to their opinion (and free expression thereof) is enshrined in our national Constitution. Simply put, we cannot seek to silence them without putting ourselves at risk for being silenced if we (at some point) express an equally unpopular opinion. That’s how a free society works. “It’s difficult not to want to silence those that offer negativity and hate, but to protect a free society by protecting free speech is a lofty goal but one that is well within reach for this Denver comics community.”

FEIGE OFF SPIDER-MAN FLICKS Deadline.com apparently resolved the question of whether Marvel Studios president Kevin Feige is leaving future Spider-Man projects with Sony. At first, the studio downplayed the idea he might be leaving; then insiders pinned his exit on added responsibilities from the Fox acquisition of the X-Men franchise, though they declined to make a statement. All this was reflected as factors in Deadline’s break of an important and widely regurgitated story. Sources maintain that Feige’s exit was about money: Feige won’t produce any further Spider-Man films because Disney and Sony Pictures couldn’t reach new terms that would have given the former a co-financing stake going forward. Disney sought the 50/50 co-fi stake as the price for Marvel and Feige’s continued guiding hand that resulted in the delivery of Sony’s biggest grossing film ever. Sony declined to meet those terms. It was an aggressive stance by Disney, which already owns the merchandise on Spider-Man, and a tough nut for Sony to swallow, giving up half of its most valuable franchise. But swallow it did. This comes at a moment when the last two films Feige produced broke all-time records — Disney’s “Avengers: Endgame” became the highest grossing film of all time, and “Spider-Man: Far From Home” surpassed the James Bond film “Skyfall” to become the all-time highest grossing film for Sony Pictures.

WIMPING CONTINUES Some years ago, Jeff Kinney announced that his most recent Wimpy Kid book would be his last. The series was then up to maybe four or five titles. Since swearing off, he’s produced another ten or so, the latest, Diary of a Wimpy Kind: Wrecking Ball, will be released on November 5. As part of the launch, Kinney will hit the road with “The Wrecking Ball Show,” reports Emma Kanto at publishersweekly.com— “an interactive performance inspired by the book’s construction theme. The show will offer fans the chance to build their own cartoons, face off in trivia, bust out their dance moves, and more. “Touring the Midwest in a Wimpy Kid bus, Kinney will stop in Austin, Houston, Oklahoma City, Minneapolis, Omaha, St. Louis, and Wichita, in partnership with local indie bookstores.” Said Kinney in a statement: “I am thrilled to be going back on the road in November to revisit the Midwest. This year, our interactive stage show is going to be over the top, with an exciting demolition theme. I look forward to building new memories by sharing this year’s show with fans new and old!” Kinney is no stranger to the stage. Last November, he trod the boards with “The Meltdown Show” on the East Coast, a live performance based on Diary of a Wimpy Kid 13: The Meltdown.

FUNKY CHARACTER TO DIE LATER THIS FALL Tom

Batiuk’s Funky

Winkerbean is “the rare comic strip that allows its characters to grow and

age,” writes George Gene Gustines at nytimes.com, and it is now a few weeks

into a 10-week storyline that ends in tragedy. “Fans of the long-running strip

who would like to be surprised by what happens to a The current continuity concerns sports-related concussions, which, in extreme cases, can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a form ofdegenerative dementia. The idea for this storyline started close to home. “The symptoms of CTE really kind of mimic a clinical depression: the confusion, the anxiety, the agitation,” Batiuk, 72, said during a telephone interview. He said he had been through a couple of bouts of depression himself, which gave him some insight into what will befall one of the strip’s recurring characters, a onetime high school football star, Jerome Bushka, who is known as Bull, and his wife, Linda. Near here are a couple strips from the story.

CUTE CHICK AND FAT BROAD NO MORE John Hart Studios Inc., seeking to end pejoratives represented in the names of two important characters in Hart’s B.C., announced via PRNewswire that the names Grace and Jane will replace 'Cute Chick' and 'Fat Broad' in the strip, effective immediately. "We work hard to keep the strip fresh and relevant for all fans and audiences," says Perri Hart, the strip's letterer and colorist. "And it just seems like the right time for 'the girls' to have names." The Hart's comic strip business, which includes perennial classics B.C. and Wizard of Id, is run by the daughters of the late Johnny Hart, Patti and Perri. B.C. is written and drawn by Hart's grandsons, Mason Mastroianni and Mick Mastroianni. "Since my grandfather's death, we've strived to be culturally inclusive and preserve the timeless appeal of the strip by focusing on universal human themes. We're all in this together, and we want B.C to connect with every audience," says Mason.

INFOWARS LOSES PEPE AND $15,000 Matt Furie, the creator of Pepe the Frog, a cartoon amphibian adopted as a far-right mascot during the 2016 presidential campaign, has successfully sued in recent years to keep his creation from appearing on white nationalist websites, alt-right Reddit forums and the neo-Nazi website The Daily Stormer. The conspiracy website Infowars became the latest online venue to say goodbye to Pepe, when it settled a lawsuit filed by the cartoonist over a poster it sold in 2017 and 2018 that featured the frog alongside images of President Trump and Alex Jones, the founder of Infowars. Under the terms of the settlement, Liam Stack reports at nytimes.com, Infowars agreed to give Furie all of its profits from the poster — which amounted to $14,000 — and an additional $1,000 that the cartoonist said he would donate to an amphibian conservation charity, Save the Frogs. In the through-the-looking-glass world of the internet, Stack said, Infowars— a site known for airing conspiracy theories that the Sandy Hook school shooting was a hoax— cast itself as the victor on Monday. “They thought we wouldn’t fight,” Robert Barnes, a lawyer for the site, said in a statement. “They thought we wouldn’t win in court. They thought wrong.” Neither side won in court, Stack points out: Infowars settled the lawsuit, the case never went to trial. Pepe began life in the early 2000s as a laid-back frog with stoner eyes and a crew of anthropomorphic roommates in a comic that Furie drew from 2005 to 2012. The artist has described Pepe as a “peaceful frog-dude” with a “blissful” attitude whose catchphrase was “feels good, man.” In a Trumpian attempt to save face, Barnes, the Infowars lawyer, described the $15,000 payment to Furie as “a licensing fee.” Later, he said he considered it to be “equivalent to a licensing fee for prior use.” Tompros said that view of the settlement was “just incorrect.” “This is not a licensing agreement, it is a settlement agreement,” he said. “They can characterize it however they want to characterize it, but it is very clear that they are not allowed to sell anything with Pepe on it unless they have a license. And they have no license.” Tompros continued: “The point of this case against Alex Jones and the point of all of Mr. Furie’s enforcement regarding Pepe the Frog is no one should think they are going to make money based on hateful Pepe merchandise. All the money Infowars made, they don’t have it anymore. They had to turn it over.”

Pepe, meanwhile, has returned to life in Hong Kong, where he shows up on posters and stickers in support of his new role as a pro-democracy freedom fighter in the Hong Kong protests, siding with the people in their struggle against an authoritarian state, reports Daniel Victor at nytimes.com. The protesters there hold signs with his image, use stickers of him in messaging apps and discussion forums, and even spray paint his face on walls. None of the people deploying the frog in this way know anything about his history as an alt-right symbol. They just think he’s cute. Pepe’s creator, Matt Furie, has said that Pepe, perpetually stoned, was meant to be positive, happy-go-lucky. When he couldn’t get the alt-right to abandon Pepe, he killed him off in 2017.

JEWS INVENTED SUPERMAN This headline will be fully explained further down the scroll of this opus. Here’s a summary from Rob Salkowitz at ICv2: the Folio Society commissioned Art Spiegelman to write an introduction for its new collection of Marvel Golden Age comics. Spiegelman complied, offering up a standard historical narrative of the sociological and economic origins of superhero comics, which is inextricably entwined with the experience of first and second generation Jewish creators and publishers during the era when Nazism stalked Europe and anti-Semitism was commonplace in the U.S. In pointing out the widely-acknowledged role that anti-fascism and social justice sentiments played in the development of characters like Superman and Captain America, Salkowitz says Spiegelman drew an obvious parallel to the current political climate in the U.S., using a reference to the "Orange Skull" currently presiding in Washington. This was a relatively innocuous line in an otherwise straightforward essay. But Marvel/Folio Society objected to it, and Spiegelman, as we explain later on, withdrew his essay rather than delete the reference.

We go into all this in vast detail anon. Here, however, I pause to ponder a couple of Salkowitz’s statements: “standard historical narrative ... which inextricably entwined” the creation of superhero comicbooks with Nazism and anti-Semitism then stalking Europe; and “the widely-acknowledged role that anti-fascism and social justice sentiments played ... etc.” The connection between anti-fascism and the creation of comicbook superheroes wasn’t made until recently in mainstream America, so it could scarcely be a “widely-acknowledged role” in “standard historical narrative.” That connection will surely be made in histories of the medium over the next few years; but it isn’t widely known yet. Salkowitz is jumping the gun a little here.

ODDS & ADDENDA Jef Mallett draws the comic strip Frazz about a songwriter turned elementary school janitor. At the end of August, Mallett wrote on his Facebook Page: It’s here! Old Ox Brewery, in Ashburn, Virginia, just released a special-edition Frazz IPA, “A Hoppier Place.” Long-time Frazz devotee and even longer-time friend Jon Brandt, who not only has great taste but lives in the right place, describes it as “… hazy, not terribly bitter and just 5.5% ABV. It’s that dry-hopped style that emphasizes the fruitiness of the hops rather than the bitterness. So nice, I had two!” Getting a beer named after you—now there’s a goal for a lifetime. DC Comics has asked retailers to destroy copies of Supergirl No.33 and Superman No.14 because the covers do not reflect the contents, says Rich Johnston at bleedingcool.com.. Replacement copies, DC saith, will be provided “at no cost.” Now there’s a deal. First, no law says you have to destroy comicbooks, and since these are likely to be instant collectors’ items, no destruction is likely. Second, stores get free comicbooks for their shelves. Who can lose?

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO You have to experience Saturday night in order to know what Sunday morning in church is all about.—Someone on Ken Burns’ Country Music series Chickens one day; feathers, the next.—Ditto; about a poor family’s diet

GUN CONTROL I dashed off the following squib last time, and because it was done in haste, I left out some key elaborations of the arguments. So let’s revisit the whole enchillada and fine tune it as we go.

HEREWITH I OFFER MY WORKING PROPOSITION for solving the gun problem in the U.S. Let’s begin by agreeing that, as a general attitude, no law is going to eliminate gun violence in this country: there are simply too many guns to control and too ingrained a propensity for gun violence. But a collection of laws might work together and separately to affect the culture of violence in which we live. Such laws might whittle away at that culture and reduce its influence. In a less violent culture, children might not grow up admiring their father’s gun collection. So here goes. To start with, I recall a woman who had just completed shooting an AK-47 at targets on a firing range. It was her first experience with an assault weapon. After discharging the weapon, she turned to her friend and exclaimed, “God that was fun!” We need to keep that in mind. Guns can be fun. It’s fun to hunt, and it’s fun to shoot guns at targets. And that may be closer to the reason people have guns than the reason they often give—self-defense. So one question underlying all the rest is: how much are we willing to risk in order to have fun? Keep that in mind as we forge ahead. First, we should outlaw AK-47s and all other weapons of war. Make it illegal to manufacture, sell, buy, or own one. If someone wants to turn his weapons in to the authorities, the government will pay him/her for them—buy them back. The penalty for owning one, confiscation without compensation. And make it illegal to manufacture, sell, purchase or possess the ammunition for these weapons. Also outlaw the “8m3 bullet,” which has a cult following because it expands and fragments when it hits human flesh, causing catastrophic wounds. When this kind of ammo is paired with semi-automatic rifles that fire bullets at triple the velocity of most handguns, the effects are especially gruesome and lethal. Surgeons who’ve treated people who’ve been shot with this kind of bullet say organs are so badly shredded that there is nothing left to repair. Why are we selling hyperlethal guns and bullets designed and marketed to make sure victims can’t possibly recover? Some idiot recently said that guns with large-capacity magazines are important for self-defense and can help when there are multiple attackers in a home. What? “Multiple attackers in a home”? When has that happened? Ever? Only in the fevered imagination of paranoid alt-righters. If we outlaw weapons of war, we won’t need to ban high capacity magazines because they only fit the weapons we’ve outlawed.

Yes, maybe banning AK-47s is the first step down a slippery slope that ends with all guns being banned. Maybe if we don’t have guns, we won’t need them. Loss of Second Amendment rights? Maybe. But sometimes we give up some rights in order to guarantee others—freedom to live, f’instance. Sometimes we forfeit some kinds of fun in order to retain others. It’s against the law to drive an automobile down a city street at 90 miles an hour because innocent bystanders might be hurt if the car goes out of control. Or if people, kids, walk in front of it while crossing the street. So we have speed limits. And we have cars. Outlawing assault weapons is the speed limit on the Second Amendment. Will it work? Franklin D. Roosevelt controlled the proliferation of guns in the age of the tommygun killer (John Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd, Machine Gun Kelly) with the National Firearms Act of 1934. But it didn’t outlaw machine guns. Instead, it placed a $200 tax on the purchase of machine guns and sawed-off shotguns—equal to about $3,800 in today’s dollars (which would effectively outlaw the weapons). Congress passed the law in June 1934, and by 1937, federal officials reported that the sale of machine guns in the U.S. had practically ceased. For our second step towards national sanity, make background checks universal. No one can buy a gun legally without a background check. No, it won’t, probably—at least at first—keep outlaws from finding guns to purchase. But the caution will begin to establish a new culture about guns, a culture in which guns are viewed as dangerous. Not toys. Not the means of having fun. Instead, guns are serious stuff, and we should treat them seriously. Like we do driving an automobile for which we must have a license. Third, let the Center for Disease Control conduct research and do studies on gun violence and mass murderers. CDC has been forbidden by Congress to do any such vital research. The National Rambo Association wouldn’t approve. While this agency should determine what sorts of research to do, I recommend working on “power” rather than “hate” as the emotional driver for most mass shootings. I just watched “John Wick 3.” It’s an almost non-stop action flick in which Wick is constantly fighting several foes at once, battering them and shooting them in the head. For all the continuous violence, the movie is actually about power, not violence. Or hatred. It’s about Wick’s ability to overpower all his opponents. My guess is that most of the mass shooters have felt powerless (probably because most of them are young); holding a powerful weapon and firing it at people gives them a sense of being powerful. We should look into it. class=WordSection5>Fourth, pass red flag laws that permit temporary confiscation of weapons belonging to mentally unstable persons or people who’ve demonstrated a desire, real or imagined, to commit murders. “Temporary” means you get it all back after having established your mental stability. This, our fourth step, is the weakest. People do crazy if harmless stuff. Teenagers particularly. Such craziness can be misinterpreted. That’s the risk. But the law should not be permitted to apply to anyone for more than a specified period of time unless dangerous mental disorder is diagnosed by recognized psychological authorities. Two weeks? A month? But teenagers shouldn’t be deprived of their freedom just because they do crazy stuff. And that’s the risk with red flag laws: teenagers, because they do crazy stuff, are vulnerable. It’s the weakest of our recommendations, but it’s also the least necessary in one aspect. It’s been well established that mentally ill persons are not prone to violence. The neighborhood bully is. The wife beater is. But neither of those is necessarily, officially mentally ill. Mental illness is what the National Rambo Association (NRA) says is the cause of gun violence. Gutless politicians agree. But blaming gun violence on mental illness is a cheap escape route. It permits the NRA and Mitch McConnell and his ilk to represent themselves as reasonable persons, acting in good faith to reduce gun violence by passing laws about the mentally ill. But they all know—or ought to know—that mental illness is not, as proven by many statistical analyses, the cause of gun violence. To say it is if you’re a politician is to lie, famously and senselessly. As I said, these measures won’t, in and of themselves, stop gun violence. But they’ll begin to bring our gun culture under quiet assault. They’ll set limits. Not big ones but reasonable ones. Over time, such measures will make guns less desirable, less romantic, less fun— and maybe, after a decade or so of cautionary gun control, we’ll have fewer mass killings. The gun culture we live in is like a fog, hanging over our lives. Laws limiting the availability and use of guns will act like bright, warm sunlight that will burn away the fog. We’ll be able to see clearly and we’ll enjoy peaceable living without fostering cultural attitudes that enable or excuse gun violence.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy WE WEREN’T GOING TO DO editorial cartoons in this opus, having exhausted ourselves in the last one (Opus 396A). But too much happened, and editoonists got their pens all sharpened up and dripping with well-reasoned vitriol, so we’ll skim over the tops. We won’t be doing Trumperies this time; but next time, we have some doozies culled from the work of Mike Peters (whose efforts I so often forget to consult on these monthly forays into Trumpery nonsense; and Peters is better at Trumpery nonsense than anyone). The major events of the last week or so include fires burning out-of-control in the Amazon, called the lungs of the planet because the trees manufacture oxygen; the Trumpet’s gaffe in predicting Dorian disaster for Alabama, 9/11 remembrance, and the third Democrat Prez Debate. And a few other matters. We’ll try to be brief. But

as Signe Wilkinson shows in our first visual aid, the most shameful of

the Trump administration’s many shameful posturings was in announcing in the

wake of Dorian’s disastrous hit on the Bahamas that it would deny entry into

the country to Bahamian refugees who didn’t have visas. The terrible irony in this announcement is that it would make the U.S. slam the door in the faces of the people whose islands Americans are so fond of visiting. The ties between the U.S. and the Bahamas are so close that Bahamians do not usually need visas to visit their relatives in the U.S. Besides, there’s a law governing such matters, and according to the law, refugees from natural disasters and wars and the like are to be admitted without paperwork. Fortunately, as it quickly emerged, the Trumpsters were way off base. The acting commissioner of Customs and Border Protection, Mark Morgan, had already begun admitting refugees without papers. A next logical (and compassionate) step would be to grant temporary work permits so hurricane survivors could sustain themselves in the interim until they can rebuild their lives on the islands. But the Trumpet’s claim that many of the refugees were drug lords and “very, very bad people” pisses me off. (Probably because we spent our honeymoon in Nassau.) (Yeh, well—that brevity we promised hasn’t shown up yet.) Next around the clock, Clay Jones shows us how the Trumpet arrives at his decisions by exaggerating his dependence upon the National Rambo Association (NRA). And below that, John Darkow’s image of a burnt out Amazon landscape suggests that the next generation will have one hell of a time restoring those vital forests. Then Bulgarian editoonist Christo Komarnitski supplies a visual metaphor that captures the essence of a dispute that raged in the news columns for days hereabouts while important matters languished unattended to. Was John Bolton fired? Or did he resign, as he claims. Trump the Mouth as a canon and Bolton as a canonball seems just right for each of the belligerent disputants. We

return, briefly, to the Amazon fires in our next exhibit. Next, we do what we usually do in this Department—compare several treatments of the same issue, in this case, the Trumpet’s silly attempt to claim he was right in predicting that hurricane Dorian would hit Alabama. Dutch editoonist Hajo de Reijger produces the hilarious image of Trump’s Sharpie extension of the hurricane’s path on a weather map to show it arriving in Alabama as if it were the hurricane not just a diagram of a hurricane’s path. The laconic demeanor of the two Alabamians completes the joke. Dave Whamond reminds us of the aid the Trumpet customarily extends to survivors in the aftermath of a hurricane’s devastation, here even more pointless because the hurricane never reached Alabama. And Steve Benson offers an image of the Trumpet under a huge storm cloud of facts, leading the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration by the nose. (The letters NOAA are, alas, barely visible on the little man in the picture; sorry, Steve.) When Trump announced that Alabama might be hit by the hurricane, the National Weather Service in Birmingham, Alabama, reacted quickly to Trump’s prediction to assure Alabamians that there was NO danger of Dorian hitting their state. Later, the NOAA, apparently acting on directions from the White House, attempted to discipline the Birmingham NWS, forcing it to “admit” that Trump’s prediction had been correct. Even though it wasn’t. The issue is still be adjudicated by feverish adherents to the opposing views. On

our next display, Gary Varvel creates a bravura demonstration of his

caricaturing skill by picturing all ten of the Democrat presidential candidates

that made the stage on the third debate. I don’t know if Varvel’s caricatured candidates are speaking their actual views on climate change, but Varvel has not only caricatured them all, he chose the worst possible angle to draw them from: full front face caricatures are very difficult to do compared to profiles or three-quarters views. Biden and Booker lean in that direction, but the other eight are straight on. The only weak renderings are Harris and Klobuchar. Next around the clock, Joe Heller looks slightly askance at the debate rules, ridiculing only the rules but those of us who watch the debates. My criticism of the debates is the same as Biden’s, the only candidate to voice his view: it’s not possible to explain the nuances of the politics on any issue in 45 seconds. In the first debate, attacked by Harris for his ostensible work years ago with two segregationists in the Senate, Biden tried to explain, and then gave up, saying only, “My time’s up.” It was nearly a satirical remark: there wasn’t enough time to explain his views and actions. His time was up before he started. Alas, with a lifetime in politics, Biden has a lot of complexities to explain, and our system of campaigning won’t give him the time he needs. Fortunately for him, people vote on personality not policy, and he’s a likeable guy. I am also amused but slightly angry at the moderators who shape the whole experience, trying, at every turn, to convert a boring few hours into something exciting by egging the candidates on to argue with each other. And the candidates, bless their little noggins, go right along with them. Is this presidential leadership that we’re witnessing? Dana Summers supplies a vivid image of Congressional Democrats returning to “work” after the summer recess (vacation): they’ll debate endlessly about whether to impeach the Trumpet or not all the while ignoring “real issues.” And Steve Benson finishes this page with an image of “eleven”—two upright arms—in remembrance of 9/11. The

same “eleven” image is deployed by Jose Neves at the start of our next

visual aid, this time, stark and stunning—two candles (lit in memory of...)

sending shafts of light upwards. “Me ‘n’ Flo never discuss politics. To be fair, it’s quite hard to bring it up while she’s bellowing at me for being drunk or accusing me of spending too much time with my pigeons. As for the protest I took part in against the Brex thingy, I’ve got to be honest: I don’t remember much about it. It came after a long lunchtime session.” And then—just to demonstrate how antic Mike Peters’ comedy is—we have one of his editoons from several weeks ago on the effect of the Mueller Report on the Trumpet: he uses it as a fan dancer uses a fan—to conceal as much as to reveal.

QUIPS & CLIPS Our dreams are big, our hopes high, our goals long-term, and the path is difficult. But the only failure is not to try. ... As long as people live in unacceptable conditions, I will continue to wage peace, fight disease, and build hopes.—Jimmy Carter

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

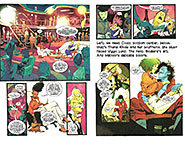

AS I’VE SAID BEFORE (or if I didn’t, I should have), it’s the artwork that attracts me to a comicbook. Not the story. Well, you can’t “see” the story when you pick up a comicbook at the comics shop and thumb through it: all you have as a basis for buying is what you see—the artwork. The writer and the artist are also helpful. If you’ve read and enjoyed their previous work, you’re already seduced to like whatever of theirs is on the bookstand. But for me, it’s mostly the artwork. Space Bandits No.1 is a good example. I’ve read writer Mark Millar’s work before (don’t remember what, but I remember his name), but Matteo Scalera’s art is new to me, and it’s exquisite. I like a line that fluctuates, waxes fat and wanes thin. But Scalera’s line is nearly inflexible—thin and delicate. So what appeals so to me? It’s the quirkiness of the visual itself: his characters, particularly their faces, are mildly distorted in the manner of cartoons everywhere, but everything else is realistically rendered. His page layouts and panel compositions are also distorted, extremely so. He regularly deploys a rigid grid layout but varies it for dramatic long distance perspectives. Close-ups emphasize aspects of the action, focusing narrowly on either the emotion of the moment or the essence of the movement. And he frequently uses extreme long shots when setting the scene. And Marcelo Maliolo’s colors play a defining role. Typically, foreground figures are darkly colored, the darkness framing the panel’s action which is in bright hues. And he sometimes reverses this process. The story in this inaugural issue is a little confusing—mostly because it seems to be about two different casts. In the opening sequence, we meet Cody, the female boss of a gang of five bandits. She and her gang are about to rob a bunch of people on their honeymoons at a space resort. Cody has a pet lizard named Cosmo who excretes a sleeping gas that knocks everyone out so they can be robbed without incident. But after the robbery, Cody’s minions turn on her, and one of them kills her so the rest of the gang can split the loot four ways instead of five. Then we meet Thena Khole and her boyfriend and cohort with a blue face, Viggo Lust. She’s a wanted criminal, and their dodge is that he turns her in for the reward, then helps her escape. And they do it all over again elsewhere in space. They appear to be in love, and Viggo suggests that they have enough money to retire after just one more job. It’s in the performance of that job that he betrays her: this time, he doesn’t get her freed, and she remains a prisoner. Taken to a notorious sentient prison planet, she meets—Cody and her lizard. So she wasn’t killed? End of No.1. No.2 went on sale in August, and I’m going back to the comics shop to buy one. I want to see what happens next. And to luxuriate in Scalera’s artistry. The first issue has completed episodes enough to reveal the personalities of the principal characters—Cody, Thena and Viggo. They are all unrepentend thieves. But we like the two women because they are victims (which naturally makes them favorites). Mysteriousness abounds: what motivates the betrayals? And how did Cody escape death? She sure looks dead when last we saw her before seeing her in prison. But the two females have personality enough to prevail over mysteriousness and provoke our interest. And near here are a couple samples of the skills of Scalera and Maiolo.

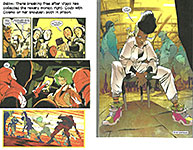

THE TITLE CHARACTER in Wyrd No.1 is an assassin, a professional hitman who works on assignment for some governmental (?) agency. But we don’t find that out about him right away. In the opening sequence of the book—“Now”— we see a guy jump off a high structure (a parking garage, I think), land in the street, and get hit by a car. Next, we’re in bed with a black guy and his wife when he gets a phone call, summoning him. His wife asks what the phone call is about, and he says: “It’s Wyrd. It happened again.” Based only upon a sequence of events—we next meet the guy the phone call is about, so, logically, he’s Wyrd— the “it” is the jumping and being hit by a car. But that’s never mentioned again. Not directly. Wyrd is in a kind of cell, the back end of a covered van, sitting there, with his trouser legs rolled up to his thighs. That’s never explained either. In short, so far, the book is well on its way to being a thoroughly mysterious mystery with no explanation, nothing making sense. But then, the black guy gives Wyrd a file folder and an assignment: go to Crimea and clean up a biological “weapon” (a giant) that’s on the loose. Before he gives Wyrd the assignment, he say to him: “When are you gonna stop with this shit? Anytime soon?” And Wyrd says: “When it works. Or I get bored. Whatever comes first.” I suspect they’re talking about his jumping off buildings and getting hit by the passing traffic. Apparently he does this as a kind of bizarre test. But it’s not referred to again. Wyrd goes to Crimea and soon encounters a giant with no shirt, who, after a fight, Wyrd kills. Standing over the giant’s body, Wyrd says: “I don’t break.” It’s his response to the giant’s having said, just a page ago, “I’ll break you.” Next, we watch as Wyrd returns to the U.S. Then, apropos of nothing, we have a three-page sequence set in 1942. A man and woman debate whether to have a child in this terrible world. They decide that since “a child is hope, a child is love, a child is the dream of a better future,” they’ll have a child. In Crimea, Wyrd encounters a child, a girl, who has been abandoned by her parents, and he sort of adopts her, takes her with him until he can turn her over to someone to look after her. He never sees her again. And she’s too young to be the child the couple was talking about in 1942. Another mystery. While too much mystery undermines a story, this one is rescued by the focus on Wyrd—on his “test” and on his Crimea assignment. He holds enough story that we can tolerate inexplicability throughout. The completed episodes—his getting hit by a car, his subsequent meeting with the black guy, “adopting” the girl, completing his assignment by killing the giant—are enough to acquaint us, slightly (but enough), with Wyrd, who he is. He seems like a good guy. With some sort of problem. He also seems invulnerable. We’d like to know more about him—why is he invulnerable? Is that what the test was about? Testing his invulnerability? Why would he want to do that? Who’s the girl? What about the agonizing couple? There are enough questions to bring me back. Curt Pires and Antonio Fuso are listed as “storytellers”; Fuso drew it. His drawing style is quirky: lines are clotted with black patches, some of which model the forms, some of which go nowhere and do nothing except add a black patch to a drawing. In rendering faces, this technique can undermine recognizability. And he likes to work in as much black as he can. He varies page layouts and panel composition wildly. In a fight sequence, parallel actions taking place somewhere else echo the main event. And in the opening sequence, inset boxes show bones breaking (?) as Wyrd falls to the street. Some pages have completely silent panels as if to make the action more memorable by pausing in the middle of it. Here are a couple sample pages.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS The Denver Post’s Megan Schrader reports: Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents deported 61,000 people between Trump’s inauguration and the end of fiscal year 2017. That’s a 37 percent increase over the same non-Trump time period in 2016, the website boasts. U.S. Customs and Border Protection meanwhile reported the lowest level of illegal cross-border migration on record following Trump’s inaugural address. Still, an incredible 303,916 people were apprehended at the southern border, trying to cross illegally. RCH: What’s illegal? If an immigrant steps across the border and asks for asylum, that’s the legal way to gain asylum. It’s legal. The illegal immigrants are the ones who cross the border and don’t ask for asylum; instead, they seek to disappear in the multitudes.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping I DIDN’T MAKE IT TO Sandy Eggo this year, but Mutts, apparently, did. Patrick McDonnell spent the week of July 17 (which includes the Comic-Con dates, July 18-21) showing how various of his dogs and cats would look dressed up as familiar superheroes.

They looked just fine.

OLD GAFFERS like me have a right to be cranky on occasion, and this is one of those occasions. I must confess, first of all, that I try to follow Tom Batiuk’s Funky Winkerbean, but I’ve been lost for at least a year. I barely recognize the characters—usually only by name: Batiuk leaped forward by about 30 years a while back, and all the familiar characters disappeared into their middle-ages. Les, I recognize Les; but that’s about all. He has a distinctive moustache and beard. In

the first strip at hand, I don’t know who’s speaking; nor do I know who Butter

Brinkel is. The storyline was explaining who murdered Valerie Pond (who’s she?), and it ended with a monkey pointing what we assume is a prop ray gun at the guy telling the story. That’s it. That’s the end of that continuity. So who killed Valerie Pond? Who’s Butter Brinkle? Who’s Valerie Pond? The next strip in my line-up, also an installment of Funky, drops another name that almost no one today will recognize—John Darling. So the character we see here (who’s she?) is John Darling’s daughter. But who’s John Darling and why should we care? We can’t care unless we know the characters. The title character in another Batiuk strip, John Darling was a somewhat dim-witted talk-show host who began his cartoon life as a supporting character in Funky, then spun off into a strip of his own on March 25, 1979. A decade later, Batiuk bumped into a contractual dispute with the North American Syndicate that distributed Darling, so he out-maneuvered the syndicate by killing off Darling on August 3, 1990. Ha! This left North American with “a largely unusable property,” as Wikipedia puts it. Darling was shot by an unknown assailant in the next to the last strip. Later, Batiuk revealed that Darling’s killer was Peter Mossman, a looney guy who dresses up like a plant to become Plantman. Before that revelation, Darling’s daughter, Jessica, showed up in Funky and became a regular character, as she is in the strip at hand. The “butt is buttered on” line probably (but who knows for sure?) refers to the aforementioned Butter Brinkel. Sally Forth is here as another instance of my being cranky. I’ve seldom, since Steve Canyon ended, seen a comic strip with more verbiage in its speech balloons. It’s a good thing this Sunday strip takes place at darkest night because the speech balloons leave no room to draw anything. So blot everything out with night.

SMOKEY

BEAR, who heads the longest-running public service campaign in the nation’s

history, turned 75 on August 9. He was born in 1944 when the U.S. Forest

Service and the Ad Council agreed that a fictional bear would be the symbol for

a fire prevention campaign. So we celebrate the occasion (lately passed) by

reprinting Chad Carpenter’s Tundra panel featuring the Bear. The remainder of this week’s lesson derives from various kinds of witticisms that we found in the funnies. I like Grimm’s explanation for avoiding exercise in Mike Peters’ Mother Goose and Grimm. It reminds me of MarkTwain’s comment to a friend who recommended exercise: “The only exercise I get,” said Twain, “is walking to the funerals of friends of mine who exercised regularly.” Jim Davis’ Garfield Sunday is a perfect example of why rolls of toilet paper should be inserted into their holders with the loose end in back rather than in front. In front permits mischievous cats and small children to indulge their curiosity by patting (or “batting” as we have it here) the roll in its holder when they discover the paper unrolls when patted a certain way. In the heat of discovery, they successfully unroll the whole roll, as Garfield has done here. If the loose end is in back, no amount of patting or batting in the discovered manner can unroll it. It’s a safety measure against mischievous cats and small children. At the bottom of our line-up, Drabble (the name connotes the kind of drawing skill deployed here) demonstrates, with the title character’s father, the supreme heights to which stupidity can aspire. The eyes again prove problematic for Kevin Fagan to render. Sigh.

MENACING MEMOS The Southern Poverty Law Center is tracking more than 1,700 hate groups, a record number.

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Books In Need of Good Reviews THE RANCID RAVES Book Grotto is littered, literally, with books and comics that we acquired with the intention of reviewing them. Alas, they’ve piled up over the years, and it has become increasingly apparent that we’ll never give most of them the kind of intensive examination they deserve. So rather than let the accretion be entirely in vain, we’ve started this new department wherein we’ll briefly describe books by way of urging them upon you; herewith—:

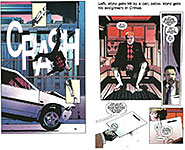

From 2017 Loose Ends 4-issue “Southern Crime Romance” Comicbook By Jason Latour (story), Chris Brunner (art), Rico Renzi (color) THE STORY, which is mostly about people bullying and shooting each other and dying, is fairly straight-up in its sordid events, but Latour has scrambled the narrative so we get sequences in a roadside bar mixed with military sequences in the Middle East then jumped back to a racial dispute in town somewhere and then flashbacked to yet another evening in that bar long ago. The central character is Sonny Gibson, who might be smuggling dope but who certainly is still in love with a barmaid named Kim, who is shot and killed in the first issue. The voluptuous chic who shoots up the bar (and accidently kills Kim) accompanies Sonny on the rest of his travels and travails. By the end of the fourth issue, she’s the only one left alive. But the reason for pondering this comicbook series is the inventive way Latour and Brunner, abetted by Renzi, achieve their narrative. The visual aspect of comics gets full play in this title, and not only are whole sequences nearly wordless, but Brunner even changes his drawing style from one sequence and scenario to another. It’s gratifying to see pictures manipulated so flagrantly, so gorgeously, so spectacularly, to tell a story. Herewith, a few of the varieties of Brunner’s treatment.

CLIPS & QUIPS “The meaning of the world lies outside the world.”—David Berman, poet “If you don’t know where you are going, you’ll end up someplace else.”—Yogi Berra, legendary baseball player and composer of numerous bon mots (such as this judgement about a famous restaurant: “Nobody goes there anymore; it’s too crowded”). A clear conscience is usually the sign of a bad memory.

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. And that’s about what you’ll see here, beginning with—: Garden of the Flesh By Gilbert Hernandez 100 4.5x6-inch pages, color; 2016 Fantagraphics hardcover, $12.99 IN THIS TINY TOME, Beto, known (and revered in these parts) for Luba and other residents of Palomar in the Heartbreak Soup series of Love and Rockets, undertakes to retell some Biblical stories, giving them a fresh modern interpretation. He begins with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, where events appear to be driven entirely by Adam’s hard-on. In fact, everything that happens in this book is about someone’s hard-on except Cain killing Abel and Noah’s ark. In Beto’s revised Bible, men punctuating eager women (rendered in explicit detail) explains a lot of what happens in the Bible and most of what is depicted herein. These happy encounters usually end with fellatio and women with cum on their faces, the least attractive visual aspect of this book. Herewith, a few exemplary episodes.

The Life and Times of Gardner Fox New book: The Forgotten All-Star: A Biography of Gardner Fox, by Jennifer DeRoss (240 5x8.5-inch pages, 2019 Pulp Hero Press paperback, $27.95). Someone else promoting the book said: Fox wrote over 4,000 comic book stories, and co-created such enduring heroes as the Flash and Hawkman. He wrote dozens of novels. He inspired a generation of comic book writers. And yet his story has never fully been told. From his youth in Brooklyn, to his decades as a pulp fiction and comic book author, to his lasting legacy, Jennifer DeRoss tells the timely tale of forgotten all-star Gardner Fox. I haven’t seen it yet, but itLi’s on my list to buy as soon as cheap second-hand copies show up at AddAll.com.

Blackhawk’s Back. DC Comics is collecting Howard Chaykin’s controversial run on the Golden Age-Bronze Age legend Blackhawk, reports ICv2. The hardcover volume collects Blackhawk: Blood & Iron Nos.1-3, plus stories from Action Comics Weekly Nos.601-608, 615-622, and 628-635 and Secret Origins No.45. The 384-page collection hits comic shops on December 11, 2019 at $49.99 MSRP. Chaykin’s original miniseries, Blackhawk: Blood & Iron No.1-3, ran in 1988 to generally good reviews, saith ICv2, but some outrage over changes to the character. The mini was popular enough to gain Blackhawk a slot for three eight-issue runs in the revamped Action Comics Weekly. In Chaykin’s storyline the Will Eisner/Chuck Cuidera character is accused of Communist leanings. Disgraced, he stumbles across a plot to overthrow the U.S. government and bomb New York City concocted by former Nazis out for revenge against the United States. RCH: Okay: that’s a cosmic thumbnail for Blackhawk—enough to remind me of him; but I missed the Chaykin series when it came out, so I’ll probably buy this reissue as if it were new. Because it is, to me.

And so’s Mr. A. IDW will publish Steve Ditko’s Mr. A in hardcover volumes beginning in 2020 despite Ditko’s having made it plain in a letter to a fan that he was against having his Mr. A stories collected, reported Mark Siefert at bleedingcool.com.

SOMETHING TO REMEMBER Humor is the universal solvent against the abrasive elements of life.—Whoever “For what do we live but to make sport for our neighbors and laugh at them in our turn?”—Jane Austin in Pride and Prejudice “There is nothing more atrociously cruel than an adored child.”—Vladimir Nabokov in Lolita

BOOK REVIEW Somewhat Longer and More Critical

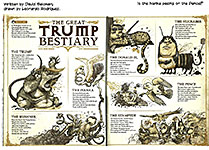

The Penultimate Mad Mad No.9 (West Coast numbering) is now out. It’s the next-to-the-last issue with new material in it; after No.10, it’s all reprint. I haven’t dug into Mad for years. I’ve picked up an occasional issue that had some sort of milestone significance—like West Coast No.1, No. 549 because of the lusty Trumpet golfer cover, and No.550 because it is advertised on the cover as “Landmark Final Issue” (i.e., the last New York Mad). “Collectors’ issues,” all of them. But I haven’t actually read one lately. While acknowledging that ignorance, I persist in thinking that No.9 is more and more fake advertising and diagrammatic games and the like—and less pictures in cartoon format. A chart that shows how Fox fits into Disneyland is amusing; ditto a feature called “Netflecchs!” But its pictures are not cartooning. So it leaves me cold. On the other hand, illustrated poetry from “The Great Trump Bestiary” is fun. The pictures are comical, and so is the poetry. Here’s one, entitled “The Trump”: The Trump says he’s a mighty bear Who frightens all he meets. He’ll try to awe you with his roars, And yet they’re only tweets. He may not be a bear at all, He’s not that strong and potent. Is he a scary predator Or just a bloated rodent?

And if you can’t read on the accompanying reproduction of the verses the one entitled “The Kurshner,” here it is:

“I love this beast,” the Trump declares. “I’ll give him lots to do. I’ll give him half the world and then Toss in my daughter, too. He’s just a dumb, entitled brat, Inept as he can be. So why do I adore him so? Because he’s just like me!”

The

verses are by David Seidman, and while they’re wonderfully comical, I

also like Leonardo Rodriguez’s pictures; so here’s the two-page spread

of the whole feature. Cartooning is present. Stalwart Tom Richmond illustrates two movie take-offs, plus the cover. I’m happy to see the original Mad title lettering (with tiny figures gamboling through the letters), and there are a couple more lampoons.

Sergio Aragones, whose “marginals” have decorated the pages of Mad since 1962, is still present. Only eight marginals in 56 pages, though. But he’s got a 4-page pantomime feature on vegetarians. He also wrote and drew the Popeye page strip that we see in the accompanying visual aid. It’s not a tribute. Except that it is a Popeye strip in the spinach-eating sailor’s 90th year. Most of the artists except those I’ve mentioned are skilled professionals, but since I’ve seen so little of their work, I haven’t had time to get attached to it. But I like Pete Woods’ treatment of Batman in Arie Kaplan’s story. Nice crisp inks and angular anatomy and lyrical lines. And at least, we’re spared, this time, the monotonous linework of Luke McGarry and his ilk, who never saw a flexible line that they couldn’t destroy.

CELEBRATING STONEWALL INN’S 50TH ANNIVERSARY

Sorry, but that’s what it looks like. I’m a little surprised Cooper agreed to it: it’s such a blatant sexy pose. But our Stonewallish surprises aren’t over yet; consider—:

Two gay male penguins at the Berlin Zoo adopted an abandoned egg and will hatch a chick in early September. The penguins, Skipper and Ping, are inseparable, and they take turns keeping the egg warm, saith a zoo spokesman (reported in The Week, August 23). How’d they know the two penguins are gay?

What’s Stonewall Inn? A generation or so ago, Stonewall Inn was a gay bar in New York’s Greenwich Village on Christopher Street across from Sheridan Square. It and other gay bars in the Village were periodically raided by the police, who would round up the patrons and put them in jail overnight and then let them go. It was official harassment of a then-outlawed sexual orientation. Then on June 28, 1969 the patrons of Stonewall Inn objected to the harassment. It started out being just another police raid on queers, but this one went wrong. As they were being ushered outside the bar, the gays objected and began to push back, shoving the cops and yelling at them. The cops retreated into Stonewall Inn for their own safety. Some queers were still in the Inn. So both cops and their quarry were shut up together for hours until, as I imagine it, early morning, when everyone gave up and went home. Some gays wound up in jail, as usual. But the rioting continued for the next several days (or nights). The cops tried again at Stonewall Inn and, again, the queers objected vociferously. Pushing and shoving and yelling and getting taken away to jail. It went on all week. Finally, I suppose, the cops got tired and gave it up for the time being. As far as I know, that wasn’t the end of police raids. But for gays, it was the beginning of publicly objecting to being treated like undesirables. Within two years, there were gay rights groups in every major American city. Hence, the landmark status of the Stonewall Inn: it was the most important event leading to the gay liberation movement. For the history of an earlier gay rights effort, Mattachine, see Opus 388. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots (as they are now termed), Rancid Raves is reviewing herewith a gay graphic novel. And “graphic” is a good word for it, as you’ll soon see. Here goes—:

Comrades By Dale Lazarov and Enrique Nieto 64 6x9-inch pages, color; 2018 Sticky Graphic Novels hardcover, $18.60 PDF at StickyGraphicNovels.com or (easier to find) classcomics.com in traditional print (sorry: no price I could find, and I forgot what I paid for it) THE SECOND MOST CONSPICUOUS ASPECT of this novel is that its story is told entirely without words—no speech balloons, no captions. Wordless. The story is sheer simplicity. Two muscular young men meet at the railway station in what I take to be Moscow. The arriving party joins the other on a tour of the miracles of cooperative workers’ endeavors. They bicycle by various famous structures and also visit a factory (where all the workers seem to be muscular males) and watch a rocket launch. Although they are hesitant at first, by the end of the second day of touring, they’ve plunged into a lustful brawl of love-making, which continues, page after page, for the remaining two-thirds of the book. And that brings us to the most conspicuous aspect of the book— the seemingly endless number of ways Lazarov and Nieto have found to depict two men enjoying sex with each other. But

that’s not all of their relationship: the last pages of the book are devoted to

showing them sight-seeing again, lounging in a park, and talking (without

words)—just enjoying each other’s company. It finally ends, however, and the

two part and go their separate ways. But the last page of the book shows them

together again as much older men, holding hands as they walk by the remnants of

the Berlin Wall (1961-1989). All at once, the tale achieves a satirical

message. The writer, Lazarov, is known as the Stan Lee of gay comics— writer, art director and licensor of Sticky Graphic Novels, “wordless, gay character-based, sex-positive graphic novels for an international audience that are considered a joyous expression of male/male sexuality that, while erotic, is neither grubby nor tasteless” (The Novel Approach). The artist, Nieto, a Spaniard, “has always loved drawing the human body in action.” He admires Burne Hogarth, Joe Jusko, and Frank Frazetta among others. He’s done work for Charlton, and has illustrated many romantic, horror and adventure comics. Lazarov’s other co-creators include artists such as mpMann, Reinhardt Logan, Foxy Andy, Si Arden, Michael Broderick, Martin Chan, Amy Colburn, Dustin Craig, Drub, Yann Duminil, Adam Graphite, Chas Hunter, Jeff Jacklin, Janos Janecki, Jean-Paul Jennequin, Bastian Jonsson, Kardyman, Steve MacIsaac, Sebas Martín, Mauro Mariotti, Player, Jason A. Quest, Bo Revel, Alessio Slominsky, TJ Wood, TheAmir, Enrique Nieto, Captain Nikko and William O. Tyler. Just to be exhaustive. As you can tell, he’s been busy. Straight people like me are likely to suffer from a kind of mild revulsion at the thought of gay men poking their peters into every available orifice—which is done with wild abandon in this book. And mine is probably a normal heterosexual reaction. But gaiety is normal, too—just another of the accidents that happen to the human embryo while still in the womb, male and female being two of the other accidents. Sexual relations among differing normals, however, remain somewhat repugnant to anyone not in the same sexual normality. But if we think about it from a considerable distance, all sexual relations, regardless of their category of normal, are vaguely obnoxious to persons of another persuasion of normal. Just to create that psychological distance and thereby to get you in the proper mood for the pictures you are about to see, there’s a story about two teenage girls, neither of whom has experienced sexual intercourse yet. One of them, eventually, does, and her friend asks her: “Well, how was it?” “Greasy” says her now experienced friend. A reminder, kimo sabe, about one of the most overlooked aspects of sexual relations by way of setting aside our heterosexual cringe at some aspects of homosexual sex.

THERE ARE LOTS OF PICTURES OF BIG DICKS in the book. We may find that excessive, but even heterosexual men when enthralled by their lusty turgid member think their dick is the largest dick in captivity, and this book portrays dicks in moments of sexual excitation; hence, in fantasy, huge, swollen with passion— and power. And

no one buying this book expects anything less, given the pictorial orientation

the cover illustration performs. Nothing in Comrades is unusual in gay graphic novels. Here’s a another Lazarov gay novel as reviewed by Brian Cronin at CBR.com: “Greek Love is the banner image for this piece. It is about two Greek warriors who get their hearts pierced by Eros' arrow, causing them to fall in love (or at least lust) with each other. Eventually, Eros gets jealous and joins in himself. Adam Graphite drew the issue from Lazarov's script and it is pretty much exactly what you would expect from the banner image above. Two muscular warriors have a lot of sex. And then Eros joins in and they have some more sex. Graphite has an interesting Adam Hughes-esque style to his work. His colors are quite lush, as well. Lazarov and Graphite certainly come up with a number of interesting ways for these two warriors to go at each other.” As Lazarov and Nieto do in Comrades. Nieto’s pictures must, necessarily in a word-superfluous tale, carry the story. And they do, not only on the endless pages of forthright sexual activity but in the early pages of the book where the two men bulge with sex appeal as they furtively eye each other in developing mutual desire.

Nieto’s drawings, while carrying the emotional content of the book, were not invented out of whole cloth. Lazarov had a hand in this part of the novel, too. How, I wondered, does he “write” what happens in a wordless story? In response to my question, he wrote: “It was a full script. I draw with words,” he said, continuing: “My scripts break down the page into panels with descriptions of the actions, expressions, and ‘choreography’ of interactions, both emotionally and physically, both in the foreground and background of the image. They also connect moments to reference I submit either as hyperlinks or folders of image files. “The artist interprets the script with his or her art and I art direct (give editorial notes) based on the interpretation’s delivery of the script’s images, ideas, actions and feelings. I give artists a lot of leeway unless their interpretation leaves out or replaces something crucial to the story or it doesn’t come through as clearly as it could.” Apart from the homosexual sex in the book, the story it tells is satirical. The book’s title is a giveaway. “Comrade” is a well-worn term for a member in the Communist Party. But Lazarov’s satire goes further, and deeper, than the name. Russia has laws against gay visibility, and yet, its propaganda art is often homoerotic: it features male workers with bulgey physiques—gay pinups, so to speak— that may be assumed to be attractive to gays. In effect, the art promotes forbidden behavior. Lazarov and Nieto’s book demonstrates the contradictory message of these two aspects of Soviet life. As one reviewer put it: “Comrades wallows in the unabashed romanticism and the muscular, unintentional homoeroticism of Soviet-era propaganda art!” And that’s not all Lazarov achieves. Pop Matters took notice: “By abandoning political screeds or stories about shame, secrets, family acceptance, and all the other storylines that are used over and over again, Lazarov makes a powerful political statement: this is normal.” Admirably put. I couldn’t help wondering, though, as I watched these cartoon men fucking each other in the ass, what the effect of their ejaculation might be. Not the immediate effect, but the shortly thereafter effect. Is it like taking an enema? So then there’d be more than one mess to clean up? There’s a joke here, but I’m not quite at it.

More? Try the novel Tricks (St. Martin’s Press) by Renard Camus, a Frenchman who presents twenty-five homosexual encounters—pick-ups at bars by cruising, mostly. From the dust jacket: “Camus captures the immediacy of his sexual experiences with French farm boys and businessmen, New York ‘cowboys,’ California intellectuals ... in explicit narratives filled with wit and affection. Camus does not justify, plead or interpret; he simply tells all—scenes and partners of the moment, from the first interested glances and small talk to the details of physical intimacy and final partings. ... The first book to chart this one aspect of contemporary gay life directly and objectively without the distortions of sentimentality, sensationalism, or fantasy.” But no pictures.

BEEFS & BOFFOS “I have nothing but contempt for anyone who can spell a word only one way.”—Mark Twain, Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, G.K. Chesterton, W.C. Field Yes, this tart utterance has been attributed to all the aforementioned. But no one’s been able to prove that any one of them coined the witticism or any of its variants. (I like: “Pity the man who can spell a word only one way.”)

SPIEGELMAN INDIGNANTLY WITHDRAWS If He Can’t Get It His Way, Then No Way The article that follows came to me over the Internet transom thanks to Mike Rhode, whose Comics Research Bibliography is a kind of clipping service covering news about comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics—without which, Rancid Raves would be decidedly poorer in the Nous R Us Department. The missive was headlined with a short smattering of the kind of headline that usually gets the adrenalin pumping, to wit—: Art Spiegelman: golden age superheroes were shaped by the rise of fascism

AND— Created in New York by Jewish immigrants, the first comic book superheroes were mythic saviours who could combat the Nazi threat. They speak to the dark politics of our times. News: Spiegelman’s Marvel essay ‘refused publication for Orange Skull Trump dig’

The explanation for the fuss: the Folio Society is publishing a compilation of golden age Marvel Comics and invited Spiegelman, the guru of comics in the provincial culture of New York City, to write the book’s introduction. Spiegelman produced the essay that we’ll get to in another moment. But the Folio Society—or, more properly, Marvel Comics— didn’t like one of Spiegelman’s sentences in the essay and asked him to remove it—or the essay wouldn’t be published in the proposed tome. Spiegelman, behaving somewhat like the guru he is, refused to make the change and, instead, withdrew his essay. I’m sympathetic: I’ve been in somewhat the same situation with a publisher, and after writing about comics and cartooning for over forty years, I was aggrieved that an editor in his twenties once presumed to tell me how to write. I’d been writing about comics for longer than he’d been alive. But I managed to choke down my ego and do as directed; Spiegelman did not. More power to him, I say. Spiegelman is a careful writer, conjuring up his allusions with a poet’s sensitivity about language, including puns and metaphors. To properly appreciate his technique, consider the phrase at the end of this sentence, which is about a new televison series, The Righteous Gemstones, “a famous televangelist family with a long tradition of fleecing their flock.” “Fleecing” has two meanings here, as does “flock.” The writer could have written “swindling their followers of their savings,” but he/she didn’t, choosing, instead, to substitute “fleecing” for “swindling” or “robbing.” And “fleecing” suggested “flock,” a flock of sheep, which is “fleeced” once a year when its wool is harvested, and flock is a common term for a congregation. Spiegelman’s prose is laced with this kind of word play. And his word play is usually infected with an acerbic undercurrent that has the effect of mocking itself. That laminates his written work with a sense of fun that makes reading it enjoyable. See what you think when you read his essay. You’ll encounter as you go some parenthetical numbers; these are footnotes, which are explained at the end. Here we go—: