|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 392 (May 5, 2019). No, this is not the Big Extravaganza Rancid Raves celebrating our 20th year of continuous posting of something twice a month—despite what you’ve been led to believe by the arrival, a week or so ago, of the Second Big Rancid Raves Video (which you can get to by going back a page to the so-called “gateway” page with the ranting Harv in the upper right corner, jumping up and down in frustration and then inspecting the box with the insane video cameraman in it). But the festivities are coming. They’ll be conducted in Opus 393, which’ll be posted 3-4 weeks hence. Instead this is just another of our usual Monumental Accumulation of news and reviews. Chattering is a way of mattering Adam Gopnik tells us (in The New Yorker), and chattering about comics is what we do here. This time, reviews of books of or about cartooning, including a long look at Golden Age Captain Marvel, the Shazam revival, the DiNK “comic-con,” this year’s Pulitzer winner, that antique sleaze comic strip Sally the Sleuth, and a long farewell to Dwane Powell, his life and career. Edtioons this time are all about Notre Dame aflame; we return to politics with a special editoon posting in a week or so. To make it easier for you to wade through all this plethora and pick just what you want to read, we’ve listed everything that’s here, in order, by department, as follows—:

NOUS R US Non Sequitur Returns in Cleveland Ted Rall Advances! *Darrin Bell Wins Pulitzer (with Profile) Comics Achieve Respectability At Last Rob Rogers Wins Headliner *Darrin Bell’s Post-9/11 Notoriety

Odds & Addenda Popeye Is 90 Mark Schultz To Return with Zenozoic Tales Yan Cong’s Naked Body Musa Kart Back In Jail

*FOURTH ANNUAL DiNK The Story of Kevin’s Hat Caricaturing Zombies with Stan Yan Cartooning Race in America with Keith Knight Denis Kitchen’s Long Interview Keith Crossly’s DayBlack Josh Knight’s Giraffes, Dali, and the Marx Brothers

The Quiz

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Man and Superman: Excellent As Compared to—: *The Shame of Shazam The Golden Age of Captain Marvel Celebrating 75 Years of Shazam

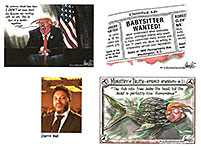

EDITOONERY Notre Dame

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Artistry and Risque Potty Humor

BOOK MARQUEE Gone with the Goof Kirby and Lee: Stuf’ Said Crumb’s Filth Bible Fifty Things from Cathy Kent State Won’t Die

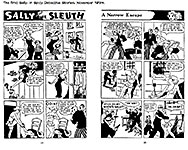

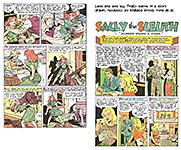

ANOTHER BOOK REVIEW *Sally the Sleuth

A-GAGGING WE SHALL GO Playboy, A Dismal Wash-Out

PASSIN’ THROUGH *Dwane Powell Greg Theakston

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em.

But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto: Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.) And in the same spirit, here’s—: Chatter matters, so let’s keep talking about comics.

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

NON SEQUITUR RETURNS IN CLEVELAND The Plain Dealer in Cleveland was among the many newspapers that dropped Wiley Miller’s Non Sequitur comic strip a month or so ago. The paper said Miller had committed a “breach of trust” by including a profane expression in his Sunday strip for February 10. When Miller wrote “to beg forgiveness,” the paper decided to ask its readers whether it should bring back the strip. The survey resulted in the reinstatement of Non Sequitur. “About 2,000 readers responded. Giving the strip another chance drew 77 percent support,” reported the Plain Dealer’s George Rodrigue. Pretty decisive in favor of the strip and Miller. Said Rodrigue: “The survey was prompted by the artist’s apology, and my question pertained, again, not to politics but to forgiveness. One reader e-mailed to say, ‘Let him back in, but if he does anything like this again, he’s out forever.’ That makes sense to me. “I’ve considered our readers’ perspective on forgiveness. It will take a few weeks, but we’ll bring Non Sequitur back. And if the artist ever does anything like that again, he’s out forever.”

TED RALL ADVANCES!!! From Ted Rall himself—: Against long odds, the California Supreme Court has granted my Petition for Review. We are asking the high court to vacate the Los Angeles Times' abusive anti-SLAPP motion against me as granted by the two lower courts. The successful Petition was drafted by my attorneys Jeff Lewis and Roger Lowenstein. Breaking precedent where newspapers are usually on the side of free speech, seven First Amendment organizations issued amicus briefs against the Times and its billionaire owner, Dr. Pat Soon-Shiong. These groups are: Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, Cartoonists Rights Network International, Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, Index on Censorship (UK), National Coalition Against Censorship, National Writers Union, Project Censored. Thank you SO much to these groups and their members for their courageous support in my struggle against censorship by the police. Both sides will file briefs in preparation for oral arguments. This is a momentous day. As many of you know, I have been fighting the corrupt Los Angeles Police Department - LA Times alliance, two billionaires (Austin Beutner and Soon-Shiong) and a media establishment that refuses to cover my case for fear of losing anti-SLAPP protections if I prevail. My first attorney bailed on me days before a key hearing, and I was forced to represent myself before finding Jeff and Roger. Both lower courts ruled against me, ordering me to pay the Times— the criminals!— hundreds of thousands of dollars. Even the LA Times Newspaper Guild refuses to acknowledge my existence— because they're sucking up to Soon-Shiong. Now all that may be about to change. No one knows how the California Supreme Court will rule, but generally speaking they don't agree to hear appeals from the Court of Appeal unless they believe something has gone seriously wrong and needs to be addressed. I have gone from believing that my case was almost lost to believing that we will probably win, and then go to trial where I will finally have my case heard by a jury. Thank you so much to those of you who always stuck by me and believed in my case. I will never forget you; I will always be there for you. Thank you.

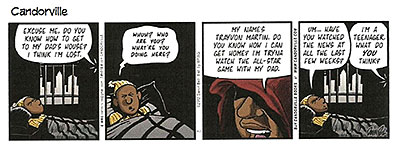

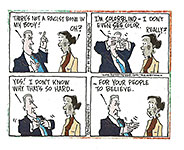

DARRIN BELL WINS PULITZER The first sentences announcing Darrin Bell’s win usually also note that he is the first African American cartoonist to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning, a category of Prizes introduced in 1922. He’s also the first Jewish African American to win. Both of these aspects of his life undoubtedly contributed to the attitude that makes Bell a sharp observer of the American socio-political landscape. But the Pulitzer announcement could also have ignored the cartoonists race and ethnicity and said, with equal veracity, that Bell is the hardest working cartoonist in the country. At one time in recent years, Bell was writing and drawing two syndicated 7-days-a-week comic strips, three editorial cartoons a week, and working on a storyboard for a “secret” project. All of which we’ll get to in a trice. But first—. As announced by the Pulitzer Board and Columbia University, Bell earned the 2019 Pulitzer Prize “for beautiful and daring editorial cartoons that took on issues affecting disenfranchised communities, calling out lies, hypocrisy and fraud in the political turmoil surrounding the Trump administration.” The Prize confers $15,000 in addition to a trophy.

“I’m honored that my work’s received this recognition,” Bell told the Washington Post. “All the nights I called home and told my wife and kids I had to stay at the office to cover something that just happened were not for nothing. I’m grateful that people think I’ve made a valuable contribution to the national dialogue, and it inspires me to keep on doing that.” Bell is no stranger to awards. In 2015, he won the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for his cartoons about race and police violence in the United States. In 2016, he brought home the Berryman Award for cartoons that addressed xenophobia and gun violence. While in college, Bell won awards, too; we list them in the appropriate place below. Trump and politics were the themes of this year’s editorial cartoon finalists. Ruben Bolling (aka Ken Fisher) and Rob Rogers, both freelancers and finalists for the Prize. Bell engages in issues such as civil rights, pop culture, family, science fiction, scriptural wisdom, and nihilist philosophy, while often casting his comic strip characters in roles that are traditionally denied them. Said Bell: “We were always minorities in every neighborhood we lived in, which I think opened my eyes a bit more to the rest of the world. I’ve always had friends who were different from me, so I have a lot of respect for diversity.” All of Bell's comic strips and cartoons come from a black/minority perspective but comment on a wide range of issues. "I

believe there's no issue of relevance that doesn't also affect minority

communities just as it does the white community," Bell says. “I cast

against type to tell dynamic stories, of people who’re bold enough and secure

enough to challenge preconceptions. I depict that as the true legacy of America,

in everything from its explorers, to its democratic-republican form of

government, to its civil rights struggle, to its injection of mankind into

space, to its musical innovations. There’s nothing more fundamentally

all-American than a square peg that insists on filling a round hole.”

BELL WAS BORN IN SOUTH-CENTRAL LOS ANGELES in 1975. His parents, both teachers, soon moved to East Los Angeles. Young Darrin, as best he can recall, began drawing when he was three years old. He remembers going with his mother while she attended classes at Cal State Los Angeles; Darrin would sit in a corner with some art supplies, quietly drawing. During most of his school years, a time when urban school districts were being desegregated, he was bused to schools as much as two hours away. Bell enrolled at the University of California - Berkeley and graduated with a degree in political science in 1999. While at Cal, he became the editorial cartoons for the campus newspaper, the Daily Californian, in 1995 when he was 20. He

also freelanced off-campus. His first sale was to the Los Angeles Times, which subsequently assigned him a cartoon every other week. He also sold his

cartoons to the San Francisco Chronicle and the former ANG papers, which

included the Oakland Tribune. His editorial cartoons have subsequently

appeared in the New York Times and several other publications, as well

as on MTV, CNN, CBS, NBC and ABC. After graduating, Bell continued freelancing (and self-syndicating, I assume) editorial cartoons and doing a comic strip he developed while at Cal. Entitled Lamont Brown, the strip started in 1993 and ran until 2003, when it was syndicated as Candorville, the first of Bell’s two comic strips; more of which, anon. On

September 11, 2001, the Twin Towers in New York and the Pentagon in Washington,

D.C. were attacked by radical hooligan Islamists flying airplanes into the

buildings, resulting their deaths and the deaths of thousands of others. Bell

drew the cartoon we’ve posted nearby. And achieved thereby national notoriety. Alas, my Internet source for the cartoon doesn’t result in a clear picture. You can doubtless make out two men with long beards, turbans and robes, standing in a huge hand with talons amid the flames of hell. You probably can’t make out a flight manual at the feet of one of them. The flight manual identifies the two men as among the perpetrators of the 9/11 catastrophe. One of the men is saying: “We made it to Paradise! Now we will meet Allah, and be fed grapes, and be serviced by 70 virgin women, and ...” All that is clear enough. But you may not be able to see that the other man is tapping the speaker on the shoulder, calling his attention to where they are—no grapes, no virgins; just flames. The Muslim notion that Islamic suicide heroes would ascend immediately to Paradise and grapes and virgins was just beginning to circulate in this country, due entirely to the 9/11 tragedy and its presumed perpetrators. Bell’s cartoon denies this notion of the afterlife: in the cartoon, people who kill others go to hell, which destiny presumably destroys some of the motivation for hooligan Islamic violence. As soon as the cartoon was published, protestors came out in force. Muslims throughout the United States were expressing mounting concern over an anti- Arab backlash after the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, for which U.S. Department of Justice and Department of Defense officials have said Islamic militants were to blame. On college campuses, the protesters mustered. "This (cartoon) is a hate crime in itself," said Abdul-Rahman Zahzah, a mechanical engineering major and a member of Students for Justice for Palestine, one of the student protesters assembled outside the offices of the Daily Californian. He said he was offended by the depiction of Muslims as ugly, conniving conspirators, as well as the suggestion that Islam preaches that violence will be rewarded. Bell

understood. More

details about Muslim protest and Bell’s post-9/11 cartoon are rehearsed at the

end of our Nous R Us section. Just keep scrolling.

MEANWHILE, Bell and Matt Richtel, a fellow Cal Berkeley graduate, were successful in syndicating a comic strip they’d been producing together since the late 1990s. Richtel, who wrote the strip for Bell to draw, adopted the pen name Theron Heir perhaps because, with a Master’s Degree in journalism from Columbia University, he thought of himself as a more serious writer (he’s authored several books of fiction). The eponymous character Rudy Park is a new technology devotee who is a barista in a coffee shop/Internet café. The strip had been running in the San Jose Mercury News and some high-tech magazines. It was picked up for syndication by United Feature Syndicate in 2001, starting September 3. Two years later, on October 19, Bell’s renamed Lamont Brown started with the Washington Post Writers Group syndicate. Lamont is still the star in Candorville, which features other African American and Latino characters living in the inner city and commenting on the passing scene. It is a much more political strip than Rudy Park, and newspapers sometimes schedule it for the editorial page rather than the comics section. Candorville has a somewhat liberal tilt even though the strip has lampooned liberal organizations like PETA and liberal politicians like Hillary Clinton, Howard Dean, and Barack Obama. The strip still appears in its birthplace, the Daily Californian, under its new title, and it is that newspaper's longest-running comic strip. Candorville appears in most of America's largest city newspapers. It also runs in Spanish-language newspapers, where it is translated by Bell’s wife, Laura Bustamante. Somewhere along the line, Bell, who was drawing two comic strips and writing one of them, stopped doing editorial cartoons. But his editor at the Washington Group, Amy Lago, had been pressuring him to pick up his poison pen ever since she arrived there in 2004. Finally, in 2012, she got her wish. That year, Richtel announced that he was taking a year-long sabbatical to explore other projects, and Bell took over writing Rudy Park. You’d think the extra work would discourage Bell from taking up editooning again. Not necessarily. Two things happened that year that provoked him enough to take up the challenge again, said Lago: “The death of Trayvon Martin [in February 2012] and the birth of his son.” In

April 2012, Bell devoted a week of Candorville to the Martin story. And when George Zimmerman, the man who killed Martin, was acquitted at a trial in July 2013, that was another provocation. Bell was outraged. He said the charged national conversation about race and criminal justice inspired him. "I think it's important that people challenge their preconceived notions. 'Why am I so quick to believe this?' That's what I try to remind people of with my work," he said. Real-life slayings of black men and teenagers in recent years, often at the hands of police, compelled Bell to continue to express himself through political cartoons. His family was part of the picture, too. Such violence is “personal,” Bell told Michael Cavna in 2014, “— because I’m going to have to have that talk with my baby boy in about seven or eight years, about how to behave when police are around, so as not to provoke them. And that’s the kind of talk a parent should only have to have with his child with regard to pit bulls.” Bell also remembers receiving “the talk” when he was young, which might have saved his life. “My mother, who’s white, had ‘the talk’ with me when I was around 6 or 7,” Bell remembered. “She was terrified because she’d caught me playing with a water gun another kid had loaned me. It looked like a real gun. She told me I’m a lot more likely to be shot by police than my friend was if they saw me with it, because police tend to think little black boys — even light-skinned ones — are older than they really are, and less innocent than they really are." His commentary on race, politics and culture — as filtered through the intensity of his experience — elevates his work, said Cavna. “Political cartoons are at their best when their authors actually display some human emotions,” Bell told Cavna in 2015. “If you can talk about people being treated poorly or denied equal rights and not be emotional or sensitive to that, then there’s something wrong with you, and you probably could use some counseling.” He went on: "One of the common retorts to my cartoons is that I’m being ‘emotional’ or ‘angry.’ And my reply to that is always, ‘You’re damn right,' There’s a time to be emotionally detached, purely objective and entirely analytical. Like when I’m doing my taxes, or playing chess — not when I’m creating political cartoons.” During a speech at the Post on Monday, April 15 after the Pulitzer had been announced, Bell said of his adding political cartoons to his output: “In comic strips, you still need to make people laugh. Some things, I don’t feel like laughing about.” When interviewed by ABC News Live, Bell said that his selection as a 2019 recipient of one of the highest honors in journalism is an important endorsement. "I

want [readers] to take away that we need to be more respectful of human

dignity," he said of his work. "That's the common thread I try to

weave through every cartoon that I draw -- whether it's about police brutality

or immigrants being separated from their children, or whether it's about Donald Bell kept on writing and drawing both his comic strips. For a period in 2017, the strips were amalgamated, running the same continuity in both, while Bell was dealing with health and exhaustion issues, saith St. Wikipedia. But he ended Rudy Park on June 3, 2018 although Rudy and other characters from that strip will appear occasionally in Candorville. With only one 7-days-a-week strip coming off his drawingboard, he has more time to draw editorial cartoons. And he’s also now producing cartoons for The New Yorker, a different sort of comment. Nearby, I’ve posted one of the latter that appeared in the magazine for April 29, which hit my mailbox just about the time the time his winning the Pulitzer was announced. Serendipity.

AFTER THE PULITZER ANNOUNCEMENT, Ailsa Chang at “All Things Considered” interviewed Bell at npr.com. She asked about the role played by Tayvon Martin. Said Bell: “Well, the trial of George Zimmerman pretty quickly turned into the trial of Trayvon Martin as far as I was concerned. It seemed like it was a criminal trial of the person who had been killed. And half the country basically decided that Trayvon Martin was responsible for his own death before the trial even started. And they didn't change their minds no matter what they saw. “And around the same time, my wife and I found that we were pregnant with my first son. And it occurred to me that if he were to grow up and something like this were to happen to him, half the country would say he had it coming. And I wanted to protect him. The only way I knew how to do that was through cartoons. That's what I do. ... “Artwork and cartoons have always been used to help us think things through. We're hardwired to respond to images. It began with the first cave paintings. Written language began with hieroglyphics. There is something called art therapy that I think a lot of people know about. And sometimes I think that's what cartooning is for me. When an issue is too hard to think about, I just start drawing and see what happens. And I just hope that if it's not funny, at least it's therapeutic. And if it's therapeutic for me, I figure it's going to be that way for readers as well. ... “I want my work to reach everyone. I was inspired to do what I did not because there was somebody who looked like me doing it. I didn't know there was. I thought everybody was white, and I thought it doesn't have to be that way. So it doesn't matter to me who's inspired by my work. I hope African-American kids are. I hope Latino kids are. I hope everyone who's underrepresented in newsrooms are inspired to pick up a pen and just start drawing their stories.”

Sources. The foregoing article is cobbled together from at least three sources, including St. Wikipedia and Michael Cavna’s Comics Riffs column at the Washington Post. I’ve tried to note the sources where appropriate, but I’m sure I’ve failed to do so everywhere I should have. And the other two or three sources, I’ve lost track of. The point of this footnote: don’t credit me with any of the best phrases in this piece; they’re all someone else’s invention.

COMICS ACHIEVE RESPECTABILITY AT LAST The April 19/26 issue of Entertainment Weakly is dubbed a “Marvelous Double Issue” and devotes 16 pages to covering “Avengers: End Game,” including six pages of interviews with co-workers on the previous Captain America films. It’s been creeping up for years, and now it’s here: comics are a respectable artform: they’ve been validated by EW. Elsewhere in the special Marvelous section, Stan Lee is remembered fondly. Robert Downey, Jr. remembers the scene where Lee was doing a cameo as a FedEx guy. “He’s like all of us. He’s really a big deal, but he’s just another schmuck and we have to get his coverage in the can, too. It’s like, ‘And roll sound—.’ and he’s like, ‘I have a delivery for Tony STANK!’ [Laughs] It went completely downhill after that.” Marvel Studio Prez Kevin Feige: “The amazing thing is, just as all of you have said, he said the right thing to the right person at all times. Every interaction was what one’s dream interaction with Stan Lee would be. He made that come true every single time. He left me a voicemail once in 2004, and I kept it for years until I think the phone disintegrated. It was: ‘Fearless Feige! Stan Lee here!’ I listened to it over and over and over. That’s what he was always like. Always supportive.” Jeremy Renner: “I aspire to be as strong-minded. The guy lived an amazing life. When you spent time with him, you just knew this guy was burning with the fire of life. He had a great sense of humor and a smart, smart mind. I hope and aspire to be anywhere half of what he was as a man. It’s really fantastic.”

ROGERS WINS HEADLINER Reported by J.P. Trostle of Association of American Editorial Cartoonists ROB ROGERS IS THE TOP HAT at this year's National Headliner Awards, winning for editorial cartooning. The judges said: "This collection of cartoons gets high marks for originality, diversity of topics, quality of artwork and clarity of message." Founded in 1934 by the Press Club of Atlantic City, the National Headliner Awards program is one of the oldest and largest annual contests recognizing journalistic merit in the communications industry. The first National Headliner Awards were presented in 1935. Since then, more than 2,600 Headliner medallions have been presented to outstanding writers, photographers, daily newspapers, magazines, graphic artists, radio and television stations and networks, and news syndicates. [Rogers’ winning is a nice slap in the face of his former employer, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, which fired him in June 2018 because he was drawing too many editoons critical of the Trumpet. But the Headliner folks liked his work for, among other things, “diversity of topics.” Ha. Rogers, by the way, had worked at the paper for more than 25 years. [Seems like everyone wants to counter the wrong of Rogers’ firing last year. He also won this year's Sigma Delta Chi award for editorial cartooning from Society of Professional Journalism.—RCH] This year’s Second Place winner in editorial cartooning is Ward Sutton, and Michael P. Ramirez took Third. Finally, a hat tip to friend of the AAEC Michael Cavna, whose Comics Riff took 2nd Place for Best Blog. Cavna covers pop culture, with a focus on cartoons and comic art, and won for “Comic Riffs: The Power of Political Art.”

DARRIN BELL’S POST-9/11 NOTORIETY The Cartoon That Stirred the Muslim Masses Christopher Heredia at the San Francisco Chronicle produced on September 19, 2001 one of the first stories about what happened when the accompanying cartoon by Bell was published the day before in the Daily Californian; herewith—: No

stranger to controversy, UC Berkeley's student newspaper today rejected Muslim

student activists' demands to print an apology for the editorial cartoon

protesters found racially offensive. Police on the campus cited and released 18 student protesters this morning for trespassing after they staged a sit-in at the Daily Californian over an editorial cartoon in yesterday's paper. At the height of the protest, 100 students assembled in the lobby of the newspaper's offices. In a brief statement issued late last night, the paper's senior editorial board said the cartoon, by a syndicated cartoonist, Darrin Bell, "solely represents the perspective of one individual. It in no way reflects the views and opinions of the Daily Californian ... staff. We maintain the cartoon falls within the realm of fair comment." The student protesters issued a list of demands, including a request for a printed apology in today or tomorrow's edition of the paper and sensitivity training for the newspaper staff, and asked that only student-produced art and cartoons be published by the paper in the future. The Daily Cal's editor-in-chief, Janny Hu, said she didn't believe the cartoon condoned violence or hatred against Muslims. She said the paper had gone to great lengths to be sensitive in its coverage of the backlash against Arab Americans. "It was a satire," Hu said. "The nature of satire is that some people will agree with it and others will not. As far as the sensitivity of this time, in a sense this is what Americans are fighting for. As our country prepares for war to protect our way of life, one of the things we are defending is freedom of speech. That's at the very heart of that." A spokesman for a Bay Area Arab American organization said his group has received hundreds of phone calls since the attacks from Muslims in the Bay Area concerned for their safety. One woman asked for an escort to the grocery store because she was afraid to go alone at night, the spokesman said. In addition, he said, Muslim parents reported that their children are being harassed at school, a business had red paint splashed on its door, and a taxi driver in San Francisco said that he was beaten up but did not report it to police because he was concerned about his immigration status. "It's fear," said Maad Abu-Ghazalah, a board member of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. "In the context of all the jingoism and anti- Islam backlash happening now, it's not the time to make a comment like that. The imagery in the cartoon is devoid of argument and debate. These subliminal messages are much harder to deal with." Campus administrators did not take sides in the protest, a UC Berkeley spokeswoman, Marie Felde, said. UC Berkeley Chancellor Robert Berdahl said through Felde that he neither condoned nor objected to the editorial cartoon. "We have to respect freedom of expression," he said through Felde, while "reminding people to be respectful and tolerant." Felde said the university held a campus-wide teach-in after the attacks attended by about 12,000 students, faculty and staff, at which the expression of tolerance for Arab Americans was a key theme.

The story, as I mentioned earlier, was quickly taken up by newspapers and other news media all across the country: everyone was concerned about the potential for backlash against the Muslim communities. But neither the Daily Cal nor Bell apologized for the legitimate coverage and comment his cartoon represented. Some years later, Bell explained his stance on apologies—:

At toontalk.com, Bell, an African American cartoonist who draws Rudy Park and writes and draws Candorville, both of which dabble playfully but pointedly in politics from time to time, is not impressed by the kind of apologies that often surface in the wake of controversial cartoons: “Personally, I don't care whether they apologize. I think there's too much demanding-of-apologies going on in this country, too many fake ‘I'm sorry you were offended’ apologies being issued, and too much mealy-mouthed back-peddling by offenders. If you didn't mean to make a racist connection, then if you're apologizing for anything, it should be for creating and publishing a poorly thought-out cartoon, not for people taking offense to that cartoon. If you think people completely misinterpreted what you were saying, just say that and don't apologize because you didn't do anything wrong. And if you did mean some sort of racial comment, be a grown up and stand behind it. But that's just me. “And that's the thing,” Bell continued: “I think people do have a choice. I went through something similar in 2001, when my cartoon depicting the 9-11 terrorists roasting in hell was condemned by Arab and Muslim groups across the country. It was on the network news, AP sent it out to hundreds of papers, there were near-riots on some college campuses, and MTV even held a roundtable discussion about the cartoon. Some people wildly misinterpreted it. “I did a few interviews. I explained what I was trying to say, but I never apologized; and to their great credit, the papers that ran my cartoon also refused to apologize. Even in the face of threatened boycotts and demands for my dismissal. Neither they nor I insulted people by saying ‘I'm sorry you were offended.’ That kind of thing would've been patronizing.” I suspect Bell’s commendable attitude still prevails and governs his work. For which he’s now received a Pulitzer and appropriate congratulations.

ODDS & ADDENDA Popeye is 90 this year. He first appeared in E.C. Segar’s Thimble Theatre on January 17, 1929. For the whole history of the one-eyed sailor, visit Harv’s Hindsight for March 2004. ... Fans of Mark Schultz’s work will be happy to know that after a 20-year hiatus, he is working on a new stand-alone Xenozoic Tales graphic novel to be published by Flesk Publications. Out next year sometime. Back in the early 2010s, Beijing comic artist Yan Cong (a pseudonym that translates to “chimney”) was told by printers that they wouldn’t wouldn’t publish any of his books with nudity in them, according to a report from theguardian.com. Both irritated and inspired, he decided to respond to the censorship with an anthology in which all the main characters were nude. Naked Body, published in Chinese in 2014, highlighted the humour, loopiness, horniness and astonishing breadth of the Chinese alternative comics scene. It is finally due to be published in English this year. Turkish cartoonist Musa Kart was returned to prison at the end of April along with five other journalists. All were charged with terrorism of one kind or another, the charges widely believed to be entirely trumped up. The case is considered to have grave implications for freedom of the press in a country now dominated by its president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has been imprisoning people he believes were supporting the 2016 coup that failed. The six were among 13 employees of the newspaper Cumhuriyet, convicted last year and given sentences of two to seven years. All were detained for nine months before the trial, but then released during an appeals process. The appeals process is now to reach its conclusion. We’ll have Kart’s story in the next Opus.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO In another sign that civilization is advancing, the famed admonition imprinted on the Crest and Colgate toothpaste tubes has disappeared. Generations of Americans were admonished “For best results, squeeze from the bottom.” It was right there, on the tube. You couldn’t miss it and make a mistake. I used to refer to this advice put on toothpaste tubes by multi-million dollar corporations as confirmation of the blissful ignorance of the American people. No corporation would waste its money on such advice if it weren’t deemed absolutely necessary. But no more. We’ve advanced beyond ignorance about toothpaste tubes. And perhaps beyond bliss.

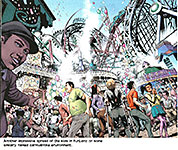

THE FOURTH ANNUAL DiNK: ADVENTURES AND REVIEWS April 13-14, Saturday and Sunday It was a great time. DiNK stands, after a fashion all its own, for Denver Independent (or “Indie”) Comic Art and Expo. DiNK. It would make better sense if it were an acronym for Denver Independent Komic-con. But, no matter. It was a great time. And attendance is up: this year, 3,957; last year, 2,992. DiNK is a kind of weedy con. It pops up in all directions. And it’s venue is similarly unkempt. It met in the McNichols building in downtown Denver. The building stands at the edge of Denver’s Civic Center park, a theatrical open space between the state capital building and the city hall 3-4 blocks away. Nothing between the two stately buildings except the grassy sward. McNicols was once the city library. When my family moved to Denver in 1944, we made regular weekly trips to the library, my parents being devout readers. The children’s department was in the basement, and my father always accompanied me there. He’d pick out books he read as a kid growing up in England—or books about knights in armor, mythological characters, and the like—and I’d check them out and read them voraciously. When I had kids of my own, I looked for books of the kind I read as a kid. I found none. Nothing about knights in armor. No books of the adventures of Greek and Roman mythological characters. Nothing. The library moved into a more spacious building in the late 1950s, and the old building, once the Carnegie Library, was re-named after a former mayor of Denver. The interior, to put it kindly, is gutted. Heating and air-conditioning ducts crisscross the ceiling, giving the venue a sort of unfinished aspect. And it’s exactly right for DiNK. Co-founded

and directed by cartoonist Charlie LaGreca, DiNK touts itself as “100

percent independent art,” said John Wenzel in the Denver Post. Actual

comicbooks are a relatively small part of the creativity on display. Small but

integral. Everywhere you look, you see cartoon characters or comics

ingredients—in zines, urban street art, tattoos, online strips, pamphlets,

booklets, graphic novels and alternative art in general, t-shirts and posters

and coasters and any and all manner of cartooning. “Independent” means privately, personally produced. No big name publishers. Several of my books are published by an academic press, and it may be the biggest name in the exhibit. And big name television and movie stars are nowhere in evidence. San Diego Comic-Con calls itself a “pop culture convention” in order to justify the massive Hollywood presence that has infected the Con for decades. But DiNK has nothing to do with big-name Hollywood. DiNK is all about individual creativity that is inspired, more or less, by comics. Its headliner this year was an experimental animation star of yesteryear. No longer the big name he once was, Ralph Bakshi was the first animator to explore the unknown realms of adult-animation with X-rated features such as 1977's “Fritz the Cat,” an immoral feline borrowed from Robert Crumb’s creation, and high fantasy like “Wizards,” the first-ever feature-length Lord of the Rings adaptation, reported Wenzel. “DiNK has always focused on the daring and edgy side of comics,” said Wenzel, “while pushing artist-friendly programming, which makes Bakshi

a spiritual cousin to the gritty-yet-earnest, socially conscious brand DiNK has developed over the past four years” of its existence. And cosplay isn’t part of the DiNK experience. I saw only a couple people in costume. Cosplay at DiNK is confined to a dog show contest on Saturday afternoon—dogs parade by in superhero costumes. As a business enterprise, DiNK was good for me. I sold well. Ran out of one of my books. Also did a couple caricatures. Sold a lapel pin. A little bit of everything. But no mugs. But the best part of any con is the conversations you have. And I had several. With Denis Kitchen, Kevin Robinette, Stan Yan, Josh Frank (and his new graphic novel about Salvador Dali and the Marx Brothers; think of that)— provoking presentation by Keith Knight. Herewith, some of those conversations and observations—:

The Story of a Hat. White-bearded Kevin Robinette is a comics historian and collector of All Things Coca-Cola. His bedroom (he showed me photos) is all Coke—shelves on every wall are laden with Coke bottles of all sorts from every land. He also collects comics and absorbs the individual histories of their titles so he can conduct a course in comics history for a university in San Francisco. Once a week for as long as he had this gig (which ended, temporarily we suppose, a few weeks ago) the school would fly him from Denver (his home) to San Francisco and pay his hotel room for a night so he could conduct the course in comics history. Kevin, wherever he goes, wears a fedora. I asked him, finally—when he dropped by my table—what is the deal with the hat. And he told me. Several

years ago when he was in San Francisco, he dropped into a hat store and when

approached by the sales clerk (who turned out to be the He disappeared into the back of the store for a few minutes, and when he returned, he was carrying a fedora for Kevin to try on. And heexplained—: This is a “Raiders of the Lost Ark” fedora, he said. The movie’s producers had bought 100 fedoras, all the same size, for Harrison Ford to wear because there was a lot of action. His hat got blown off and trampled on frequently. So for the next scene, they needed another hat, a new untrampled upon hat. They used up 45 of the 100 fedoras, and when the shooting of the movie was over, they offered the rest for sale, and the clerk/owner of the hat shop in San Francisco bought them—all 55 of them. That settled it. Kevin bought one. And henceforth, whenever he goes out, he’s wearing an Indiana Jones fedora.

Caricaturing Zombies. Stan Yan stopped by my table, and we talked about caricaturing. Stan gave up a job on the fringes of the stock brokery (as I recall) to do what he loved— to make comics. Shortly after this transition, he happened upon his present gold mine—making zombie caricatures of people. He draws a caricature then adds rotted flesh to the picture. Presto: zombie caricature.

I

do caricatures on demand at my table, putting the caricature on a figure

already in a cartoon, giving that figure the caricatured face of the customer

in front of me. Well, not nobody. One person this DiNK bought one. The “putting out to sea” cartoon. But you’d think if it was such a nifty idea, my supply of blank-faced cartoons would be sold out in a few instants. Nope. You’ll notice in these cartoons that all the figures without heads are male. Why no females? Good question. Years ago—whilst still wet behind the ears—I did caricatures of all the members of the Red Cross drive committee; they were displayed in the window of a downtown store. The women were universally unhappy with their caricatures. A couple decades later, I was talking with a woman cartoonist who hired out to do caricatures at parties. I said I didn’t envy the mine field she’d be walking through and told her about my unhappy experience with doing caricatures of women. She knew whereof I spoke, and told me how to navigate the mine field. Do a caricature of the women, she said, and when you’ve roughed it out, make two modifications: give them large eyes and long necks. They’ll love the result. I told this story to Stan, and he had one to tell me in return. A woman came up to his booth and wanted him to do a zombie caricature of her. “And make me sexy,” she said. “What? !” Stan said, quoting himself as he thought at the time—“I’m drawing you as a zombie.” Sexy too? With bits of flesh falling off and holes in the head and stitches on the cheeks? I’ll see Stan again on Free Comic Book Day: we’re both guests at the I Want More Comics Shop on May 4.

Cartooning Race in America. Comics Can Change the World. Keith Knight has three cartoon enterprises. He does a daily, 7 days a week, syndicated comic strip, The Knight Life, starring himself, his wife, and kids. Comedic slice of life stuff. His oldest effort is The K Chronicles (“K” standing for “Keith Knight” I suppose). It’s a multi-panel comicbook-page style cartoon, and I think he does one a week, distributing it to alternate papers. His third undertaking is an overt editorial cartoon called (th)ink. While race figures somewhat in the strip and in K Chronicles—Knight is African American— (th)ink is a deliberate political statement and often takes on the topic of race in America.

I’ve known Keith for years. I met him in Artists Alley at the Sandy Eggo Con one year several generations ago; we were seated next to each other for the 4-day extravaganza. A couple years ago at the Cartoons Crossroads Columbus expo in Columbus, Ohio, Keith had a display table, and after exchanging greetings, I asked him about the “conversation on race” that everyone urges Americans to have. What would that conversation consist of? I wanted to know. What would white people be expected to contribute? I didn’t get a satisfactory response at the time. He was in the middle of a tabletop exhibit, after all, and there were customers to attend to. But at DiNK this year, Keith had a presentation, and I went to it, and I got an inkling about what that conversation would be like. From one side of it anyhow—his side. The presentation was entitled “Red, White, Black and Blue—Why America Keeps Punching Itself in the Face When It Comes to Race.” He didn’t exactly answer the implied question. But he said provocative things—things that, for me, shed the light of one side of a conversation on race. Most

of the conversation about race today in America, he said, is about making white

people comfortable. We’re racially illiterate, he said. And But comics, he said, can change the world. A step in the right direction would be a requirement that everyone have at least one black teacher in his/her life. Why? Because teachers are respected, and a black teacher proves black people can do that job. Afterwards, I went to see him at his table, and asked him what a white person would be expected to contribute to the conversation. “Should I start by saying I’m fearful of black people?” I asked. He nodded but indicated that would be only the beginning. And it’s long past the time to begin.

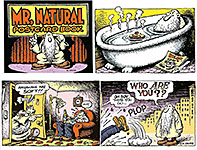

MY TABLE was on the third floor, and Denis Kitchen’s table was in the same line-up, second down the line from mine. Denis has more books to his name than I remember, so I was pleasantly surprised to see them all stacked up on his table. Everything Including the Kitchen Sink is “the definitive interview with Denis Kitchen” by Jon B. Cooke (112 8x11-inch pages, b/w with color; 2016 Denis Kitchen paperback, $17.95). The “interview” is preceded by a 20-page narrative of the Kitchen career (interviews with a score of people who knew him, Jay Lynch, Skip Williamson, Adele Kurtzman, Pete Poplaski, Milton Griepp, Howard Cruz, etc.), and that follows a 4-page cartoon introduction by Poplaski, who’s “been working with Denis since Quagmire Comics in 1970" (about the latter— “too far ahead of its time: it’s better slabbed than read”). The “interview” begins on page 26 with “Denis Kitchen, cartoonist, publisher, art and literary agent, author, historian, collector, first amendment champion, nancy & jukebox freak. ... An oddly compelling and mondo snarfo career.”

The type throughout is tiny, which allows plenty of room for hundreds of illustrative shreds and patches—photos, book and magazine covers, and excerpts from dozens of Kitchen publication projects, ending with Kitchen’s comicbook version of the life of Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss). I can’t wait to read it. Among his publications are several books of postcards. I bought the Mr. Natural book. “Nobody knows what a postcard is anymore,” Denis cracked. As you can tell from the photographs accompanying this foray into DiNK, Denis is a much more dignified personage than I: he appears attired in a suit. No tie, but a suit. I barely make it into a shirt. Just before his long-lost youth as a hippie comix creator and publisher, Denis ran for lieutenant governor of Wisconsin as a socialist. I asked him if he was still a socialist, and he said yes and no. He retained a few of the principles. But not all. He did surprisingly well in the election, he told me:

he came in fourth in a field of six. Or some such number better than last. Perhaps not so surprising. Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s largest city, has a long history as a socialist government. When I got home from DiNK, I found the April 15 issue of The Nation, which has in it an article about Milwaukee's historic socialism. A friendly article: "Many Wisconsinites know that their state has a long, rich socialist tradition, and that Milwaukee's association with it is one of the coolest things about the city." It quotes Time, saying: "Milwaukee became one of the best-run cities in the U.S." under socialist mayors. It had three socialist mayors from 1910 to 1960, the longest, from 1916 until 1940, 24 years. I never knew. John Nichols, the author of the piece, goes on to say: “Milwaukee’s socialists were so fiscally and socially responsible that historians to this day hail them as exemplars of a uniquely American form of democratic socialism. [One of the mayors, Frank Zeidler (mayor 1948-1960), told Nichols], ‘Socialism as we attempted to practice it here believes that people working together for the common good can produce a greater benefit both for society and for the individual than can a society in which everyone is shrewdly seeking their own self-interest.’ “That worked well for Milwaukee in the 20th century—so much so that ‘socialism’ ceased to be a scare word for the city’s residents. What frightens Republicans today is that ‘socialism’ is ceasing to be a scare word in our contemporary national discourse.” The occasion for the article? The Democrats are holding their nominating convention in Milwaukee in 2020. Denis and I exchanged stories about Al Capp and Milton Caniff— he, drawing upon his research for his Capp biography, A Life to the Contrary; me, drawing upon my research for my Caniff biography.

ME AND LINDA used to move in and set up the afternoon before the show opens, but over the years we learned that it takes us less than an hour to set up at these neighborhood cons, so we moved into DiNK early in the morning of the first day, Saturday. We get almost all of our goods into three boxes, which we can move from the car to the exhibit floor in one trip on the handcart we have. What remains are supplies for caricaturing and a display bulletinboard. This time, we left the bulletinboard in the back of the car because our table was in front of a window, and we enjoyed the view (of food trucks lined up outside) and didn’t want to block it with the bulletinboard.

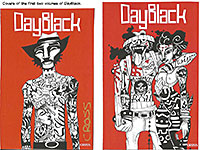

On

one side of my table, was Keith Crossly (aka Keef Cross), who was

selling the first two volumes of his graphic novel, DayBlack, and

posters thereof. Over my shoulder in the photo of me standing at my table, you

can see a portion of the cover of the first volume that Keef had reproduced as

a huge poster, and I’m posting nearby a scan of both book covers. I looked at the covers and exclaimed, “Man, that looks ‘African.’ Were you inspired by African art,” I asked Keef. “Did you see any before you did this?” “No,” he said. “Well, it sure looks African-like to me,” I said. “Must be in the blood,” Keef grinned, with a snort of a giggle. He’s African-American. I bought one book and was astonished that he handed me the second, too—a gift. Each book appears to bind into one volume about three chapters of the tale of DayBlack (100 6x9-inch pages, stunning black and white with red accents; 2015 and 2017 Rosarium Publishing paperback, $14.95 each). Back cover copy sets up the story: “DayBlack is the story of Merce, a former slave who was bitten by a vampire in the cotton fields. Four hundred years later, he works as a tattoo artist in the small town of DayBlack. The town has a sky so dense with pollution that the sun is nowhere to be seen, allowing Merce to move about freely, night or day. “Even darker than the clouds overhead are the dreams Merce has been having that are causing him to fall asleep at the most awkward times (even

while he’s tattooing someone). As he struggles to decipher his dreams, someone from his past returns with plans for him—plans that will threaten his new way of life and turn him back into the cold-hearted killer he once was.” Merce has modified his tattoo needle mechanism so that one needle sucks blood while the other needle tattoos. So his vampire hunger is sated somewhat. But the story is much less absorbing to me than the pictures. The pictures are stark psychedelic renderings, symphonies of black and white like nothing I’ve ever seen before. Take another look nearby.

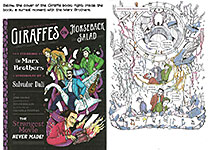

ON

THE OTHER SIDE, between our table and Denis Kitchen’s, was Josh Frank,

whose new graphic novel, Giraffes on Horseback Salad starring the Marx

Brothers in a never-made movie with screenplay by Salvador Dali, has

just come out. In fact, Frank was waiting for a shipment of the books even as

he was setting up his table. The book (224 7x9-inch pages, sepia and color; 2019 Quirk Books hardcover, $29.99) is a surreal graphic novel from page 45 to page 204. Preceding it is an essay by Frank in which he regales us with the journey of his discovery of the Dali screenplay—or, rather, the fragments that he would subsequently turn into the screenplay—and a novelized and illustrated story of the meeting of Dali and Harpo Marx and their ensuing friendship, which resulted in the Giraffes project. Then from page 205 until the end on page 224 are various ingredients—sketches for the graphic novel by its visualizer, Maneula Pertega, fragments from Dali’s Giraffe notebooks, type-written pages of a screenplay and so on. “When Dali first saw a Marx Brothers movie,” writes Frank, “it put him in a trance because he felt he was watching the human embodiment of surrealism in its purest form—all of the Marx Brothers, but specifically Harpo because Harpo was unbridled, almost animalistic, so he loved Harpo.” Harpo was in Paris in 1936 on a publicity tour for “A Night at the Opera” when he met Dali. “Even though they didn’t have a language in common, the pair clicked,” said Peter Breslow at npr.org, “and Dali decided to incorporate the Marx Brothers into the movie treatment he was working on”—i.e., the Giraffe movie. Dali and Harpo pitched the project to MGM in 1937. Dali wasn’t well-known at the time, but the Marx Brothers “were at the height of their popularity,” says Breslow. “Louis B. Mayer didn’t particularly like the Marx Brothers,” he went on, “and he didn’t know what to make of Salvador Dali, so he killed the project.” No,

I haven’t read the graphic novel yet. But at a glance, it looks like a happy

marriage between the surrealist comics, the manic Marx brothers, and the

surrealist painter, Dali. The back cover blurb teases out the tale inside. “A businessman named Jimmy finds himself drawn to the mysterious Surrealist Woman, a shape shifter whose very presence transforms reality. With the chaotic help of the Marx Brothers, Jimmy tries to join her bizarre world, but forces of normalcy seek to end their unusual romance. [‘She is eventually arrested for her surrealist crimes and winds up in court where the mayhem of the Marx Brothers ultimately liberates her. These moments are depicted in the book as the trippiest of swirling LSD experiences’ according to Breslow.] Newly scripted Marx Brothers-style antics and songs meld with Salvador Dali’s dreamlike world to create a cinematic love story that defies logic and dazzles the eye.” Frank is a life-long Marx fan. When he was twelve, he dressed up as Harpo for a Hallowe’en party. Although he’d never done anything like a graphic novel before, in college, he was a film study major, developing skills that helped as he transformed a script into a visual story. After he had a script, he went through it and highlighted the action parts and the most important plot points so the artist would have some guidance in developing the visuals. Developing the script was no easy job, Frank told me. He was working from Dali notes and various sketches—“a somewhat incomprehensible screenplay” he said— hard enough in itself, and then he’d come to a place where Dali had noted “Marx mayhem here.” No other guidelines. So Frank had to make up Marx mayhem on demand. “It was crazy surreal,” Frank says, “and totally not digestible.” He told me about how he got the rights to Dali’s story and from the Marx estate to use the famous brothers in the story. It took a while to find the Marx estate executor, but when he pitched the idea for the graphic novel, they liked it and approved it. Only two other Marx projects were approved by the estate before the operation deteriorated, once again, into turmoil. Getting permission from the Dali estate presented a unique problem: they spoke only Spanish, and Frank spoke only English. The project took six years to assemble the resources and then to develop them into a graphic novel. First, Frank had to find the Dali material. Then he had to get it translated from Spanish into English; he had a friend who did the job. Next, he found a comedy writer, Tim Heidecker, who assembled a writers’ room to produce the Marx mayhem. After that, he found an artist who would illustrate the enterprise. For that, he wanted someone in Dali’s native Spain, so he posted a want-ad online and “found Manuela Pertega, an artist from Barcelona whose work was breathtaking: lush, passionate, magical, and, of course, surreal. ... With the help of Google Translate (neither of us speak the other’s language particularly well; Harpo and Dali had exactly the same problem when they worked together some eighty years ago), we created sample pages that led us magically to Quirk Books,” the publisher of Giraffes. The collaboration worked, says Frank. “Next thing you know, I’m creating a new piece of Marx Brothers art for the world, and it’s a dream come true.” The story of Jimmy appears in the book as a duotone in sepia/gray; the surreal episodes are in full color.

You’d think that would be enough. But, no—Frank wanted songs, music, in the book. “What is a Marx Brothers movie without songs?” So he found a songwriter who was also a Marx Brothers enthusiast, Noah Diamond. Clearly, without sound, music in cold type is reduced to poetry, the song lyrics. But it’s there. And Pertega gives it a beat. “There’s a soundtrack to go along with the graphic novel— including music, complete with a faux Groucho,” said Breslow. When not attending DiNK this year or researching some new project, Frank runs “the world’s smallest drive-in theater” (in Houston)—only 25 cars at a time. He shows only classic movies. And in the summer, he moves the whole operation to Mintern, Colorado. If you think that’s a little surreal, you’re probably right.

Kevin

Robinette, whose hat we inspected up the scroll, convenes meetings of the GROUP (Greater

Rockies Organization of Ultimate Panelologists)

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics

A FRIEND READ DC’s Man and Superman and said it is the best comicbook he’s read in a long time. I’m not inclined to go flat out that far, but since I can’t remember one better, I’ll agree (provisionally). The book has an unusual and convoluted history. Writer Marv Wolfman completed the story in about 2009, he tells us in the book’s introduction; and illustrator Claudio Castellini drew it then, too. It was originally produced for a publishing project that was ultimately shelved, and so Man and Superman languished until now. DC finally opted to publish the story in big, fat 100-page “super spectacular” square-back book. It’s not really a Superman story, as Wolfman observes: it’s a Clark Kent story. It tells how he came to Metropolis and found a job on the Daily Planet, how he met and interacted with Lois Lane, and how he found himself—after a few false starts—as a super-powered do-gooder. We’re used to a confident Superman. But Clark Kent wasn’t at all confident at first. He was wracked by doubts. He’d come to Metropolis with a single suitcase in which Ma Kent had packed the costume/uniform she’d made for him. What’s the ‘S’ on the chest for? Clark wanted to know. “I don’t know,” Ma says, “but it was on the inside of that rocket that brought you to us, and it seemed important. Besides I thought it would make people look at it and not just your face.” In his ordinary street clothes, Clark flies around doing good on a couple occasions and earns the moniker “the flying man.” Getting a job on the Daily Planet isn’t easy. Clark learns that he must produce a story that’s spectacular enough to win editor Perry White’s admiration. Clark finally achieves his goal by “interviewing” himself as the Flying Man. Sensation. At the last minute as that edition of the paper heads for the printer, Lois gives the Flying Man his name, scratching that name off the penciled headline and substituting “Superman.” This summary scarcely does Wolfman’s story justice. He gives Clark’s hesitancy and insecurity nuance and thereby substance. And he makes Lois into a terror of a female journalist—a star reporter with all the ego and sass of a 21st century rampant feminist. And I haven’t mentioned the subplot involving Luther and his desire to take possession of Metropolis and how Clark frustrates his scheme. Castellini produces marvelously detailed and realistic artwork, every wrinkle and eyelash in place. Nitpicker that I am, I found fault with some of his work. Spotting of solid-black shadow seemed misapplied in some instances: instead of modeling a form, it distorts it. Some other trifling flaws are noted in the accompanying visual aid, but for the most part, his work is not only entirely serviceable but in many cases spectacular.

Meanwhile, it’s odd that in the same weeks as we find a superior Superman story we encounter a dismal failure of a Captain Marvel story. Captain Marvel rivaled Superman for a decade, outselling the Man of Steel many times over. But these days? Well, let’s take a look at—:

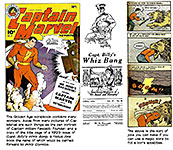

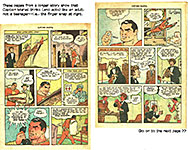

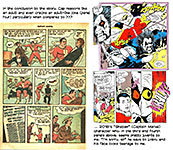

The Shame of Shazam Its Present Debacle and Abuse A Very Long but Vastly Amusing Detour That Eventually Gets to a Comicbook “Shazam” is an acronym, the letters of which stand for a roster of heroes who represent various heroic traits—Solomon, wisdom; Hercules, strength; Atlas, stamina; Zeus, power; Achilles, courage; and Mercury, speed. “Shazam” is also a magic word, which, when pronounced by a teenager named Billy Batson, turns Billy into a super-powered adult named Captain Marvel, who can fly and lift ocean liners out of the sea, and whose body is invulnerable. But at first—in the initial stages of his conception—the character was quite different. As concocted in 1939 by Bill Parker, then editor of publisher Fawcett’s Mechanix Illustrated, and artist C.C. Beck, the character was named Captain Thunder, and he commanded a team of heroes, each possessing one of the attributes later combined in “shazam.” That notion, however, was soon abandoned, perhaps because of its inherent cumbersomeness, and by the end of the year, Captain Thunder embodied all the traits of his erstwhile lieutenants. Captain Thunder was to debut in Flash Comics, but another publisher, All-American Comics, had just launched a comic book with that title, so the Fawcett editors tried again with Thrill Comics. That title, unhappily, was too close to another rival publisher’s Thrilling Comics. By the time they resorted to Whiz Comics in February 1940, Captain Thunder had been re-christened Captain Marvel. The most inspired aspect of the Captain Marvel creation was his having an alter ego, the youth Billy Batson. Young male readers would identify with Billy, who was the actual protagonist in the Captain Marvel stories: a smart, inquisitive and precocious orphan boy (who works like an adult as a radio reporter), he gets himself into trouble by investigating mysteries, and then he summons a grown-up version of himself who gets him out of trouble. For any boy reading superhero comics, it was a dream come beautifully, simply, true. Unfortunately for Fawcett, when DC Comics, the publisher of Superman, saw Captain Marvel, he saw copyright infringement (skin-tight costume with cape, invulnerability, super strength, and the ability to fly) and sued to get Fawcett to cease and desist. The law suit lasted for the entire run of a catalogue of Captain Marvel comics (which established Captain Marvel as the most popular of the super-powered heroes of the day, out-selling even Superman). The suit went on and on, back and forth, DC winning one battle, Fawcett the next. Finally, Fawcett gave up in 1953 and settled out of court. By then, superhero comics were fading in popularity, and as circulation dropped, Fawcett decided to get out of the comic book business. So Captain Marvel disappeared until 1972, when DC Comics, having negotiated the publication rights for the character, brought him back to life, thinking, no doubt, to revive not only the character but also his stunning sales record. For a complex of legal reasons, DC could not use the name “Captain Marvel” in the title of the comic book, so the book was entitled Shazam, and it has been by that name that most of the subsequent attempts at rejuvenating the character have appeared, albeit with today’s personality-driven superhero formula. The current revival of Shazam, like all its predecessors, is startlingly unsuccessful. It, like all the others, fails to capture the essential nature of the Fawcett character. By the summer of 1941, Beck and writer Otto Binder had shifted the character off the center of superhero gravity and started doing more whimsical stories. Before long, a light-hearted, tongue-in-cheek treatment prevailed. And once that set in, the similarities between Captain Marvel and Superman ebbed away into near non-existence, and Captain Marvel emerged as a unique creation, scarcely a copy. So unique that no one has since been able to satisfactorily bring him back to life. But they keep trying. And in anticipation of the arrival in theaters last month of the “Shazam” movie, DC has once again attempted to do justice to Captain Marvel.

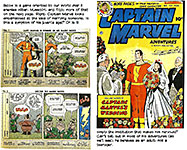

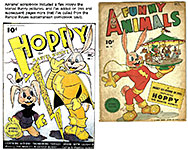

AND IT HAS, ONCE AGAIN, FAILED. But Abrams tried to do justice to Cap by producing a scrapbook, entitled, like all Cap’s appearances since 1972, Shazam, with the subtitle, The Golden Age of the World’s Mightiest Mortal (224 9x12-inch pages, color; the 2019 reissue of a 2010 Abrams hardcover, $24.99) by Chip Kidd and Geoff Spear. Kidd’s byline signals a book that is as much a design artifact as a printed source of information or entertainment. And that’s the case here: it looks like a scrapbook. The scrapbook format permits the editors to scatter hither and thither fragments of Captain Marvel’s past, all kinds of merchandise— rings, t-shirts and jackets emblazoned with lightning bolts, wrist watches likewise, figurines, Captain Marvel Club membership cards and letters to members, promotional photos for the Captain Marvel movie serial, jigsaw puzzles, coloring book covers, and on and on—all on loan from the collection of Harry Matetsky. Among the treats herein, a complete 15-page Captain Marvel story by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. Not much expository text. But pictorially, the scrapbook seems to cover all the bases. It includes information about other members of the “Marvel Family,” Captain Marvel Jr. and Mary Marvel but not much about the “fake” Uncle Marvel, the old fat geezer who goes around imitating the others in his home-made Marvel costume. When a long-lost sister of Billy Batson shows up, she’s given Shazam powers and becomes Mary Marvel. In those discrete days of yesteryear, her creators made her a pre-teen girl, which means she has no visible boobs. Probably a sound editorial decision: it enables her writers to avoid the topic of sex altogether, retaining a distinguishing feature of the Captain Marvel books—their absolute sexless wholesomeness, aimed, unflaggingly, at young readers, so young that they may not have heard about sex yet. Freddy Freeman, a crippled newspaper seller, is a little older than Billy, I’ve always thought. He turns into Captain Marvel, Jr. by saying “Captain Marvel.” We used to get a good laugh out of that: Captain Marvel, Jr. is the comicbook superhero who can’t say his name because if he does, he turns back into Freddy. And that’s not all that’s odd about this character, as the editors of the book at hand point out: “Freddy lives a drearier life than a down-and-out waif in a Victorian novel. He’s stuck with a gimpy leg that requires him to always use a crutch; he’s clad in tattered clothes; and he lives and sleeps in a drafty, forlorn attic when he’s not toiling at his job hawking newspapers on the sidewalk for pennies. ... Why on earth Freddy wouldn’t want to be Captain Marvel, Jr. 24/7 defies logic. ...” As Captain Marvel, Jr., Freddy escapes all the miseries of his daily life. But he choses to be Captain Marvel, Jr. only when evil strikes others. That’s beyond odd: it’s perverse. Even odder, we never thought of this while laughing about his name. The man who drew much of the early Captain Marvel, Jr. oeuvre, Mac Raboy, became as famous as C.C. Beck who drew Captain Marvel. But I never liked Raboy’s work: he was too fussy, laminating his drawings of the lithe Junior with far too many feathering and modeling lines. Raboy’s Captain Marvel Jr. had an almost prissy air about him, wholly out of place in an slam-bang adventure story hero. Raboy left Fawcett in the spring of 1946 to assume pictorial command of the Sunday comic strip Flash Gordon. About 30 years ago, I learned the name of another Captain Marvel, Jr. artist—Bud Thompson—whose work I admired for years without knowing his name. His art was cleaner than Raboy’s, his line was more confident, his work less sprayed with feathering. The Abrams book also includes material from the Spy Smasher’s career with Fawcett. Spy Smasher was Fawcett’s Batman, but I was never taken in by the character. I was taken in, however, by another branch of the Marvel Family. Fawcett’s Funny Animals comicbook starred a cotton-tailed rabbit, Hoppy, who, by saying Shazam, could turn himself into a much more formidible version of himself with a swelling chest, red costume, yellow cape and yellow boots. Captain Marvel of the hutch world, drawn by the redoubtable Chad Grothkopf (who drew the other stories in the books, too). But I liked two other regulars at Funny Animals more: Billy the Kid, a Western starring a goat; and Sherlock Monk, a detective chimp. I’ve posted nearby samples of the scrapbook content of the Abrams book plus a helping of Funny Animals stuff.

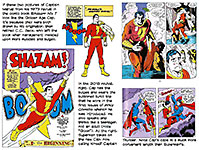

Shazam the Golden Age takes us back to those happy days of the forties, culling from the cultural detritus glistening reminders, for me anyhow, of a long lost youth with comicbooks. But DC has produced another variety of Captain Marvel’s history—reprints of landmark tales from the last 75 years.

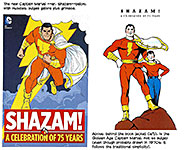

SHAZAM!

A Celebration of 75 Years (400 7x10-inch pages, color; 2015 DC Comics hardcover, $47.99) like all Captain

Marvel books these days avoids mentioning the hero’s name, but there’s a hugely

muscled Cap by Cameron Stewart on the front of the dust jacket and, for

the sake of contrast here, a classic Cap on the book cover by C.C. Beck,

the man who gave Billy Batson and Captain Marvel their appearance. Despite Beck’s formative role in Captain Marvel’s history, only 7 of the book’s 21 stories were drawn by him. The book is organized chronologically, beginning with the origin tale from Whiz Comics No.2 in 1940. The first chapter takes us from 1940 to 1953, when Fawcett gave up its copyright struggle with DC. The next chapter resumes Cap’s history by reprinting stories from the Shazam reincarnation of the 1970s. Beck drew these at first, and we all rejoiced. But DC wanted a Cap bulging with muscles, and Beck was philosophically opposed to that (he used to write articles scoffing at the muscled superheroes) and persisted in drawing Cap in the simple outline manner of his first incarnation. Beck and DC soon came to a parting of the ways, and other artists, led by Kurt Schaffenberger, took over. Before long, Captain Marvel’s physique looked pretty much like every other superhero’s. Still does. Shazam ran February1973 -June 1978, and after a brief pause, Cap resumed appearances in other DC titles, represented in the second chapter with stories from 1982 to 1991. The third chapter resumes the history in 1995 with another Shazam title and then Cap has guest appearances in other titles, ending in 2013. The fourth chapter includes the New 52 version of Cap. Each chapter has a text introduction by (in order) Richard A. Lupoff (comics historian), E. Nelson Bridwell (editor), and Jerry Orway (comics writer and artist), all reprinted from earlier publications. The stories brush by various of the classic Captain Marvel tales—Black Adam shows up, Mr. Mind (the all-powerful intellect worm who tortured Cap for more than two dozen consecutive issues), the Marvel Family, Hoppy, and Jeff Smith’s version of the Monster Society of Evil (led by Mr. Mind). Mr. Mind’s Monster Society of Evil serial with cliff-hanger endings in every chapter ran from No.22 (spring of 1943) to No.46 (spring 1945), 25 issues of Captain Marvel Adventures. That a fantasy involving an evil worm directing the criminalities of monsters would occupy so many pages of a superhero comicbook during World War II when exciting patriotic violence had broken out over half the globe may seem odd. Why not attack Nazis? But I think the fantasy was created deliberately to divert young readers’ attention from the real warfare. By the end of Mr. Mind in the spring of 1945, the war in Europe was over, and Captain Marvel could resort to other excitements involving people rather than an insect. The Mr. Mind series did not entirely displace ordinary criminals and fiends in Captain Marvel Adventures and the other Fawcett titles Cap appeared in, so the strategy, if that’s what it was, wasn’t airtight. But it seems at least possible if not probable. The most serious damage done to the Captain Marvel tradition was the alteration in his appearance, all those muscular bulges. But another change was introduced in the early 1990s. Someone at DC evidently wondered what happened to Billy Batson’s personality when he shouted “Shazam!” and turned into an adult superhero. The brilliant conclusion of this pondering was that Billy’s personality stayed right there, now inhabiting the body of Captain Marvel. So we now encountered a superhero with the mind of a 12-year-old. (Sometimes, they say Billy is 15 years old, a somewhat more believable age

for a kid with Billy’s record of harrowing exploits.) Many of today’s comics fans have assumed that Captain Marvel always had the mind and desires of a 12-15 year old kid. Not true. That’s a modification of recent times. In the olden days (when Beck was overseeing everything), Billy’s juvenile personality disappears when Cap shows up. That may seem highly illogical, but we all accepted it as normal (insofar as the world of superheroes is ever “normal”). In any event, as far as I’m concerned, that alteration is the final desecration of the funnybook hero of my youth. Phooey. All the recent publishing of Captain Marvel stuff was paving the way for the arrival of the movie.

SHAZAM THE MOVIE I haven’t seen. My grandson has, and so has his mother (my daughter), and she says one of the aspects of the character of Billy is that his personality is carried over into Captain Marvel whenever he yells “Shazam!” Too bad. That makes the whole enterprise a somewhat juvenile undertaking. I probably won’t go see it. But I have read and studied the first four issues of the new Shazam comicbook, which seem to perpetuate the ambiance of the movie. The focus of the continuing tale, so far, is on Billy Batson and five of his friends—Mary, Freddy, Pedro, Eugene, and Darla—who are all residents of a foster home run by Mr. and Mrs. Vasquez, Victor and Rosa. They are all Shazam-endowed, and when Billy says his magic word, all of the “Shazam Team” appears, each in his/her colorful costume. Captain Marvel—with Billy’s 15-year-old personality—shows up in No.1 to stop a robbery by some unruly teenagers. Then the six stalwarts go to a deserted train station and take the next train to MagicLand. Cap doesn’t appear in No.2. But Dr. Sivana, Captain Marvel’s arch enemy in the old Fawcett books, shows up; ditto, Mr. Mind, a giant worm. And Mr. Batson—presumably Billy and Mary’s father—arrives at the Vasquez’s front door. But he doesn’t appear again until No.4, and even then, we don’t know what he’s doing there. In No.3, the kids are in FunLand, being led around by King Kid, who hates adults and wants to keep all of our gang in Funland, virtually captives. So Billy shouts his word again, but only he and Pedro and Eugene are transformed; the other three are not in proximity and therefore don’t get the transformation. Next in No.4, we’re in WildLand and we meet Talky Tawny the voluble tiger in a business suit, another happy relic from the Fawcett years. Meanwhile, King Kid is still on his rampage, and Cap (shocked electrically into unconsciousness) is taken captive; ditto Mary, although she’s in a different place. Freddy and Darla are in WildLand, and Eugene and Pedro are in Gameland. And Mr. Batson is still at the Vasquez’s but is taking his own sweet time telling us why. On the last page of the book, Black Adam (another of the traditional evil-doers) shows up, muttering imprecations. I fully expect Hoppy the Marvel Bunny to arrive in No.5, but I won’t be there to see him. This title is more than mere desecration: it is a wholesale slaughter of all that Captain Marvel Club members hold sacred. And since the whole purpose of the title is to resurrect the spirit of the departed world’s mightiest mortal, I’m fairly confident in saying this re-launch is a screaming failure. And hereabouts, we’ve posted a few more specimens of the new Shazam for our Marvel Gallery.

Otherwise, if you want the complete story of the invention of Captain Marvel and the details of the law suit DC Comics served on Fawcett, visit Harv’s Hindsight for September 2006, “Captain Marvel: The Big Red Rip-off?”

Persiflage and Furbelows TRUMP HEIGHTS By Loveday Morris, Washington Post JERUSALEM - Three weeks before Israel's closely fought election, President Donald Trump gave incumbent Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu a political boost by recognizing the Golan Heights as Israeli territory. Now Netanyahu, who ended up winning another term, says he wants to repay the U.S. president— by naming a new settlement there after him. "All Israelis were deeply moved when President Trump made his historic decision to recognize Israel's sovereignty over the Golan Heights," Netanyahu said in a video released by his office. "Therefore, after the Passover holiday I intend to bring to the government a resolution calling for a new community on the Golan Heights to be named after President Donald J. Trump." So it’ll be called The Donald? Or maybe the Trumpet’s Toot?—RCH

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy None of our usual political mockery this time, kimo sabe. We’ll take our customary grimace at those disgraceful shenanigans in a special Bonus posting a few days hence. This time, we concentrate on the single most stirring event of the past month—the fire at Notre Dame. Before we get to the editoons, we pause to contemplate actualities as represented by photographs of the conflagration and its aftermant.