|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

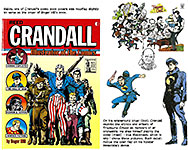

Opus 370b (September 11, 2017). Here’s the second half of Opus 370, the first of which was posted a couple weeks ago as Opus 370a. I thought this would be shorter, but, as usual, my mouth ran away with itself. But the happy result is a cornucopia of news and reviews galore—cartoons debut at Esquire (a critique), Playboy landmarks in comedy, Archie’s new comics, editoons that offend, Cartoon Bank gyping cartoonists (?), graphic novel problems in libraries; reviews of first issues of comic books Divided States of Hysteria, Dark Days—The Forge; and of books, Behaving Madly (Mad imitations), Trump Tweets Illustrated, The Spectacular Sisterhood of Superwomen, Reed Crandall biography, and graphic novel Rolling Blackouts; various notes and comments on Jefferson MacHamer, Beetle’s birthday, Charlie Hebdo’s new offense, the Lone Ranger mystery, obit for Tom Eaton, and more, much more. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order—:

NOUS R US Beetle’s Birthday Alt-Right Pepe Suppressed Comic Characters In Court Image Is Twenty-five But Savage Dragon Is Older The Return of Superheroes of Color Archie’s New Comic Books Editorial Cartoons Draw Complaints Charlie Hebdo’s New Offense Caniff Biog Sold Out

Odds & Addenda Air Guitar Championship The Lone Ranger Mystery Nurses Caught Ogling Big Dick Disney Will Stream Marvel Movies and Star Wars

THE NEW YORKER AT ESQUIRE A Critique

Cartoon Bank Gyps Cartoonists

PLAYBOY LANDMARKS IN COMEDY

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE The Divided States of Hysteria Dark Days: The Forge

EDITOONERY Sampling Last Month’s Mischief

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL What’s Happening on the Funnies Pages

GRAPHIC NOVELS ARE POPULAR— But Problematic in Libraries

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews Of—: Behaving Madly (Mad Imitations) Trump Tweets Illustrated Three New Scholarly Tomes And Some Old Harvey Mischief

BOOK REVIEWS Longer and Opinionated Reviews Of—: The Spectacular Sisterhood of Superwomen Including Sally the Sleuth Reed Crandall: Illustrator of the Comics

GRAPHIC NOVEL Review Of—: Rolling Blackouts: Dispatches from the Mideast

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Jefferson MacHamer’s Glamor Girls

PASSIN’ THROUGH Tom Eaton Obit

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:. Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

Happy Birthday, Beetle Mort Walker’s comic strip about a lazy private was 67 years old September 4. When Walker devised the strip in 1950, the title character was in college; he was based upon a character Walker used in magazine gag cartoons whose name was Spider. When King Features bought the strip, they dropped the name because another of the syndicate’s features was using it. Instead of Spider, they called Walker’s college kid Beetle. Good choice: as everyone knows, spiders are icky but beetles are intriguing. Walker gave his new creation a last name that gestured gratitude to John Bailey, the cartoon editor at the Saturday Evening Post who had advised the young cartoonist that if he wanted to do a comic strip he should do it about something he knew well—in Walker’s case, college life. However

deep Walker’s insight into higher educational shenanigans, the strip didn’t

sell. King was thinking of dropping the strip. Then inspiration struck. The

Korean War was going on at the time, and since men of Beetle’s age were being

called up left and right, it seemed logical to take the kid out of college and

put him in uniform. So Walker did just that: on March 13, 1951, with the strip

barely six months old, Beetle enlisted. Due to the interest in the military

during the war, a hundred papers promptly picked up the strip. Thanks to his

own military experience at the end of World War II (particularly being in

charge of a German POW camp in Italy), Walker knew army life as well as he knew

college life. Walker still draws the strip (he pencils; son Greg inks), making him an uncontested record-holder: he’s drawn the same comic strip longer than anyone else on the planet has drawn the same comic strip. When the strip started, Beetle was probably around 20 years old; so now, he’s 87. Walker was born on the day before Beetle first appeared in syndication, September 3, 94 years ago. And I’m a mere broth of a boy at 80. Happy birthday, Mort. Ditto Beetle. Onward.

ALT-RIGHT PEPE SUPPRESSED The creator of Pepe the Frog, a cartoon character initially created in the 2000s as a fun-loving post-college grad but eventually designated as a hate symbol by the Anti-Defamation League (see Opus 366), has forced the removal of a children’s book from distribution because it featured the frog, reported Sopan Deb at nytimes.com. The legal team representing cartoonist Matt Furie, Pepe’s creator, said that the book, titled The Adventures of Pepe and Pede, “espoused racist, Islamophobic and hate-filled themes, included allusions to the alt-right movement.” The book, released earlier this summer, was written by Eric Hauser, who lost his job as an assistant principal at Rodriguez Middle School in Denton, Texas, as word of the book spread on social media. As the Washington Post has noted, Deb writes, “the villain in the book is an alligator named Alkah, which many took as a reference to Muslims, and the farm where the story takes place is Wishington, a play on Washington. In recent years, the protagonist, Pepe, became a symbol of the so-called alt-right and white supremacy.” So whatever confrontation takes place, it pits the alt-right against Islam—with a predictable victory for the former. Hauser, like many right-wingnuts, claims he and the book are innocent of any such conspiracy (saith RCH). Deb reports that Hauser “said that his book was merely meant to be a children’s book with a conservative viewpoint.” Oh, sure. “I’m not concerned with using those characters because there is nothing wrong with those characters,” Hauser told the Dallas Observer. “They’re not bad characters,” he said, adding, in reference to allegations of links to the alt-right, “I disagree with the label. I think that label was put on Pepe in an attempt to silence conservatives. That’s not what Pepe was about.” Furie disagrees about the innocence of Hauser’s book. Furie has vigorously fought against the co-opting of his creation, even starting a Kickstarter campaign in June to “to resurrect Pepe the Frog in a new comic book reclaiming his status as a universal symbol for peace, love and acceptance.” Furie threatened legal action against Hauser’s book, citing intellectual-property infringement, and the threat was enough. As part of a legal settlement, Hauser must donate his profits from the publication of his book to the Council on American-Islamic Relations, an advocacy group for Muslims. Boy, I bet he likes that.

MORE LEGAL ACTION ON COMIC CHARACTERS News on two intellectual property lawsuits was revealed in mid-August, and Milton Griepp rounds it all up. The more boring of the two is the Hasbro vs DC Comics-Warner Bros confrontation over “Bumblebee,” which is the name of a Transformers character and of a character DC is currently using in Super Hero Girls. The suit, according to Hollywood Reporter, focuses on the Super Hero Girls action figures (made by Mattel), which Hasbro alleges infringes on their Bumblebee mark for the same category. The Bumblebee character from DC pre-dates Hasbro’s first use, but Hasbro produced the first Bumblebee toy. The more interesting of the two suits is the litigation over rights to Buck Rogers, the fabled godfather of space adventuring in comics. Buck Rogers isn't quite as well-known as Luke Skywalker, Captain James T. Kirk or Flash Gordon, but people are more familiar with Buck Rogers than John Carter, Hal 9000 and the Doctor from Dr. Who. How do we know that? asked Eriq Gardner at the Hollywood Reporter. Because, he avers, a survey was taken as part of the ongoing legal action. The lawsuit is between descendants of author Philip Francis Nowlan, who created the fictional space explorer in Armageddon 2419 A.D., the novel where the property originated the 1920s, and descendants of John F. Dille, whose newspaper syndicate once distributed a Buck Rogers comic strip based upon Nowlan’s book. The legal issues are complex and subtle and too convoluted to briefly describe here, where our less complex and un-subtle brain is focused mostly in the tussle. Simply put, at issue is who owns Buck Rogers and can therefore profit from a “Buck Rogers” feature on the Syfy network. “The genesis of this dispute,” says Gardner, “dates back to Nowlan's death in 1940. Afterwards, his widow brought a lawsuit against Dille alleging that the author had been underpaid. This settled in 1942, and in exchange for $1,750, the widow released claims and assigned rights.” Her heirs have conveniently disregard this settlement, but that doesn’t matter. The real issue is who was first to claim Buck Rogers. Neither Nowlan nor Dille it turns out—but their respective trusts. However apparently there is no paperwork to back up either claim. Hence, all the legal maneuvering. The Dille faction points to the way it continued to license “Buck Rogers” for vintage merchandising and role-playing game. If it hadn’t the right, how could it license anyone? Everyone just presumed, I suppose. By way of establishing their right, the Dilles put forward various pieces of evidence among them a survey that showed 63 percent of respondents recognized Buck Rogers. In comparison, Gardner notes, 91 percent recognized Captain America, 87 percent recognized Luke Skywalker, and 5 percent recognized a made-up character known as "Frederick Johnson" (perhaps showing that one can get 1 in 20 people to respond yes to practically anything.) Dunno what all that proves, and a judge agrees, asserting near irrelevance for a claim that the success of the Buck Rogers character owed more to the syndication of the comic strip than to Nowlan’s book. I’d agree with that, but as I say, the judge said it doesn’t matter as far as determining who has the rights to Buck Rogers is concerned. The judge says the results "fall far short of the recognition of other marks held to be famous," also shrugging at a Buck Rogers show at the Smithsonian and insubstantial royalties for old movies and commemorative statues. “Maybe,” hazards Gardner, “a Buck Rogers reboot would bolster the space explorer's name recognition, but it appears that won't happen until some of the issues surrounding ownership get sorted.” And that leaves us where we started: there’s this law suit. ...

Image Is Twenty-five BUT SAVAGE DRAGON IS OLDER Eric Larsen, one of the original founders of Image Comics, is the only one of them who is still doing the comic book he started out with—Savage Dragon, 225-plus issues. And still going strong. None of the other seven founders are still doing comics for Image. Some aren’t even doing comics anymore. Larsen’s dedication and perseverance is all the more notable when we realize that he invented the character when he was nine years old— 45 years ago. Interviewed in Image+ No.10 (April 2017), Larsen recalled Dragon’s earliest manifestation: “I just knew that I loved comic books and wanted to create comic books. The Dragon at that point was a total rip-off of Batman, only instead of long ears he had this fin on his head. But he had a utility belt and a cape and all the rest. He drove around in Speed Racer’s car because I was a big fan of that show. It was pretty wild stuff, but there wasn’t a grand scheme behind it. I was a child and I just wanted to create stuff.” The Image reincarnation of Dragon “was very much a new beginning for the character,” Larsen said. “He had evolved over time. That culminated in a fanzine that I self-published when I was 19 years old. When I started Savage Dragon at Image [in 1992], my big idea was to work toward those [early] stories. So I started in a very different place—I didn’t want to repeat all my nonsensical childhood stories—but chose a direction that could end where I’d left it. More than anything, I just wanted to do a more realistic version of Marvel Comics, to take the kind of things I read as a kid and use that as a jumping-off point. “I wanted to do a book that was somewhat more mature,” he continued, “—where characters went through real life situations, got old, got married, had families, and went through all of life’s changes. Plus, more realistic dialogue and language. More of an R rating. But real time means little until kids start showing up and people start showing serious signs of aging. Now that I’m 25 years in, it’s really starting to show. Now Dragon’s a grandfather, and his son is the lead character. It really hits home that people go through a lot of changes over time. Contrasted with the comics I read as a kid, I’m decades ahead of where they were.” Larsen has no plans to end the saga. “Ideally, it’d go on for the rest of my life,” he said, “but I don’t know that I can bank on that.

All there and still a-comin’. Hats off to Eric Larsen, who, in doing what he loves doing, is doing it with greater dedication than anyone else. And he’s making comic book history as he goes.

SUPERHEROES OF COLOR ARE MAKING A COMEBACK Joe Illidge is back with superheroes of color, which is where he began in 1993 as an intern with Milestone Media, working with classic black comic book characters such as Icon, Rocket and Hardware, reported David Betancourt at washingtonpost.com. “Illidge learned under the leadership of the Milestone co-founder, the late Dwayne McDuffie, as they embarked on a publishing journey meant to give black superheroes their place in comics with roles that were more than sidekicks and stereotypes.” Today, Betancourt continued, Illidge is a senior editor at the Lion Forge imprint Catalyst Prime, a job he got in June 2016 to oversee a new superhero/sci-fi comic book universe featuring diverse characters — “and, just as important to Illidge, diverse creators — with stories taking place all over the world.” Catalyst Prime’s comics include Noble, featuring a black astronaut who goes missing on assignment in space and resurfaces with superpowers, though he’s on the run in Latin America while his wife and a Latina-led secret organization track him down. The series Accell centers on a Latino character who runs faster than the speed of thought after exposure to an alien object (see our review, Opus 369). Cosmosis, a character with down syndrome, is featured in the series Superb. Illidge has assembled some of the top writers in comics, including David Walker (Luke Cage), Christopher Priest (Black Panther) and Amy Chu (Poison Ivy: Cycle of Life and Death). The rest of Betancourt’s report follows, verbatim—: Despite efforts at major publishers like Marvel and DC Comics to introduce new, diverse heroes — at times taking existing mantles (Spider-Man, Thor, Green Lantern) and placing them on minorities — Illidge feels a void has been apparent in the comic book industry since Milestone ceased publishing in 1997. Most importantly to Illidge, McDuffie’s influence at Milestone guides him to this day. “The biggest lesson I learned from Dwayne that I’m able to bring to this job is that story is the most important thing,” Illidge said. “Creative ego has to go in back of the story. Every person in the process, from myself as senior editor, the writer, the penciler, inker, letterer, colorist, everyone’s primary job is to tell the story. If we at the Catalyst Prime team can give you that, then I feel like we’re fulfilling our promise to the readers and our fans.”

ARCHIE CONTINUES TO PUSH THE ENVELOPE Jon Goldwater lit a fire under Archie Comics several years ago when he approved the publication of funnybook in which Archie marries both Betty and Veronica. And Goldwater’s never stopped exploring new possibilities. At Hollywood Reporter, Graeme McMillan interviewed Goldwater about new directions, beginning with this observation: “Archie Comics has changed significantly over the last few years, both in terms of the company and its output. From 2014's ‘Death of Archie’ comic book storyline through the tv debut — and success — of the CW's “Riverdale,” the very idea of the Archie characters have gone from pop culture curiosity to something that feels contemporary and exciting for a whole new audience.” Naturally, CEO and publisher since 2009 Goldwater, son of original Archie co-founder John L. Goldwater, agrees:"It took longer than I thought, but with a lot of work, we made Archie relevant. We made it a vibrant, living thing as opposed to a retro concept." This sort of self-congratulatory effusion is standard with Goldwater. And we must say, it’s not all hype: there’s fact and justifying history behind it. As the company readies a number of new comic book launches — including The Mighty Crusaders and B&V Vixens, McMillan asked Goldwater if Archie and the gang can tell any kind of story that the writers conjure up. “Archie can do anything,” Goldwater said. “It’s not just one kind of comic, show or concept. You can do a horror Archie story, you can do a superhero Archie story, you can do a drama or comedy. ... As long as the story feels true to the spirit of the characters, it can be anything. Archie fights zombies, has powers, tours the world — there’s no limit to what you can do with these amazing characters. We’ve finally gotten to the point where the world is seeing that, too. “One of the things I’m most proud of,” Goldwater continued, “is that, as a company, we’re not afraid to take risks. We’re not scared of trying something that pushes against where the industry is going. The Black Hood, the first Dark Circle title we launched under the imprint, is a perfect example of that.” And in December, another new superhero title will join the Circle, The Mighty Crusaders. "We wanted to create a book that’s accessible, not mired in a million crossovers and part of a bigger, unfolding story," Goldwater said. "For that, we enlisted [writer] Ian Flynn, who’s done a lot of marvelous work for us and has a history with the Crusaders. On art, we have Kelsey Shannon, who did some nice work on the Josie and the Pussycats book recently and has a really clear, modern and welcoming style.” The result, McMillan said, “is something squarely aimed at contemporary superhero readers — and maybe some fans who have been scared away from other publishers because of the amount of knowledge needed to follow a story. Goldwater called the series ‘a lynchpin book that we hope will lead to more spinoffs and expansion for the Dark Circle universe,’ promising, ‘You don’t need a PhD in comics to hop onboard. Everything is explained in the first issue. These are beloved, iconic characters and it’s time we dust them off and let them shine for what they are — amazing superhero properties that deserve a bigger spotlight.’” Another new title is B&V Vixens, a Betty and Veronica expedition. Said Goldwater: “I’ll be frank here, because it needs to be said: Betty and Veronica are icons. They are beloved. They are hugely important to what we do at Archie and they deserve to be treated on the same level as Archie. Like Archie and Jughead, B&V are flexible if they're treated honestly, which this book does. It’s fun, edgy, different and something so unexpected I think fans will love it. It’s an exciting new chapter for the characters and I’m thrilled [writer] Jamie [Rotante] and [artist] Eva [Cabrera] are the ones telling it. They are names to watch.” Goldwater also spoke about the revival of Cosmo, “a genuine blast from the past,” said McMillan, adding, “The original version of this — Cosmo the Merry Martian, about a Martian astronaut on his way to Earth — only lasted, what, six issues in the late 1950s?” “With Cosmo,” Goldwater said, “we see a lot of opportunity to tell a fun adventure tale, featuring one of our classic concepts. Cosmo as a character and universe really lends itself to the serialized stories and world-building Ian Flynn is great at, and we're excited to hand him the keys and let him cut loose when this debuts early next year. It fills an important space for our line. “I feel like the tv ‘Riverdale’ really kicked a door down,” Goldwater reflected, “—and presented to the world an idea that was already common knowledge in comics — that Archie Comics has a wide, diverse and multifaceted library of characters. From Katy Keene to Cosmo to Dark Circle to Josie and the Pussycats — we cover a lot of ground and we have decades and decades of great storytelling to support that. Now that the show is on the air, is a hit and is gaining so much momentum as we head into the second season, I feel like people outside of our industry are starting to take notice — and they’re interested. It should be a very fun few years. “I think we’re in a transitional phase, in terms of publishing,” he went on. “We’ve cycled through some titles — books like Josie and the Pussycats and Jughead have gone away for the time being to be replaced by other books, like The Archies or Jughead: The Hunger. We’re trying new things with our IP in order to keep fans engaged but also keep our top-of-list titles in the mix. So while we continue to keep our publishing lineup diverse and attention-worthy, I think you’ll also see us re-entrench a bit in terms of our core properties, like Sabrina, Betty and Veronica and those kind of titles.”

EDITORIAL CARTOONS DRAW COMPLAINTS Political

cartoons, almost by definition, make some people angry—all those people who

don’t agree with the editoonist. Among those who complain are often some whose

sense of propriety is offended. In the last few weeks, three editoons ruffled

these feathers of sensitivity. This sort of brouhaha arises often—too often for

us to remark about every instance of it; but we thought we’d report on these

three complaints by way of illustrating what editoonists face nearly every day.

They usually apologize for offending everyone who’s offended—but without

retreating from the position taken in the cartoon. At the Omaha World-Herald, Jeff Koterba’s cartoon, at the top of our line-up, was a comment on the frequency of U.S. Navy warship accidents—four this year. In the latest, ten sailors died. Ironically, the cartoon ship rams the U.S. Naval Academy because the service school apparently hasn’t taught the sailors how to operate a ship at sea. Offended readers thought the cartoon lacked compassion. One reader wrote: “It’s a tragedy. Lives were lost. Their families are going through unimaginable pain. I will never ‘like’ the cartoon, but I believe you have the right to publish whatever you want. I just wish you’d have waited a little while before you published this.” Editorial page editor Cate Folsom responded on behalf of Koterba and the paper, stating, “I want to make it clear that we do not perceive any factual error on Jeff’s part, nor do we view this as an ethical breach. Beyond that, we think Jeff’s note speaks for itself.” Koterba noted: “I drew the cartoon because I’m on the side with the kids. So that no sailor should have to die in an accident.” Koterba added, “It’s my job to shine a light on problems so they don’t persist. The cartoon comes from a place of compassion.” But the cartoonist, who has been with the World-Herald for 28 years, also realized how the cartoon could offend, and he subsequently apologized: “To anyone who has been hurt or offended by my cartoon regarding recent U.S. Navy warship accidents, I would like to offer my sincere and heartfelt apology.” Koterba added that he always tries to bring “compassion and humanity” to his work, as well as provide social commentary on “darkness, to point out that which needs fixing.” He explained, “when innocent sailors die, not in battle, but in yet another naval accident, I believe it’s my job to put pen to paper. I thought I was helping the cause. But clearly, with this cartoon, I failed. And for that I am deeply sorry.” The Matt Wuerker cartoon at Politico, next down the line-up, also riled some readers, who felt it was “a slap in the face to a group of people who are still reeling from unimaginable tragedy.” The Washington Post’s Aaron Blake argued that problems with the cartoon include its “crassness,” “stereotypes,” and “a needlessly vast oversimplification of a very complex issue at a very sensitive time.” Wuerker responded to a few tweets, writing that his cartoon is “making fun of the Secessionist movement. Not at all aimed at all Texans.” He added that the cartoon is “very pro Coast Guard and doesn’t take away from all heroic private individuals who are also doing so many rescues. ... Just trying to point out in times like this we’re lucky to have rescue services,” he tweeted. “Don’t see how this takes away from private individuals heroism.” In a subsequent statement to the conservative-leaning Washington Examiner, Wuerker defended the cartoon as a general commentary on Texas secessionists: “As a political cartoonist, I try to get people to think – to consider the ironies and subtleties of the world we live in. This cartoon went with an extreme example of anti-government types— Texas Secessionists— benefitting from the heroism of federal government rescuers. It of course was not aimed at Texans in general, any more than a cartoon about extremists marching in Charlottesville could be construed as a poke at all Virginians,” he added. “My heart is with all the victims of Hurricane Harvey’s destruction and those risking their lives to save others.”

MEANWHILE, IN CHICAGO, conservative editoonist Eric Allie did an online cartoon for the Illinois Policy Institute that seemed to be racist (at the bottom of our stack of questionable cartoons). Eric Zorn at the Chicago Tribune explained: “Chicago’s public school student population is 46.5 percent Hispanic, 37.7 percent African-American, 9.9 percent white and 5.9 percent ‘other,’ according to the most recent data posted to the Chicago Public Schools website.” That would seem to justify Allie’s choice of a black kid to represent the school kids in Chicago, but it was a provocative and risky choice, Zorn acknowledged. And he continued (in italics): As another white male, allow me: The cartoonist erred in drawing an African-American child to represent a student population that’s more than 62 percent non-black, and he erred in giving that child exaggeratedly large lips, even though exaggeration of physical attributes is quite common in cartooning. This made the cartoon racially inflammatory, even if, as I’ll assume, there was no racist intent behind it. How inflammatory? I can’t say. ... White males are ill-situated to gauge the degree of hurt or to critique the reactions of those for whom racial slights are more than just theoretical. Bottom line, the cartoonist’s choices were regrettable. They hurt people’s feelings and distracted from the point he was trying to make, that tax increment financing “districts rob Illinois children — including children of color — of the funds necessary for their education,” as Illinois Policy Institute CEO John Tillman put it in a statement. [Not included here.] But about that point … It’s wrong. It misrepresents how property taxes are levied and how schools are financed — both rather convoluted subjects that are easily demagogued. The annual tax revenue allotted to CPS is capped by the law that limits increases in property taxes, and is already at the legal maximum. TIFs have their flaws, no question. But to portray them as pocket-bulging slush funds that local fat cats could easily tap to pay for the day-to-day operation of schools if only they cared about minority children is false. And then Zorn added: “Portly rich Caucasians should be offended as well.”

AAEC Defends Allie. The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists came to Allie’s defense—: Last week, a few Illinois lawmakers made news by accusing an editorial cartoon of being racist. The cartoon, created by Eric Allie for the Illinois Policy Institute website, showed a child representing school children appealing for funds from a man who displays an empty pocket while hiding wads of cash in the other. The cartoon's critics apparently take issue with the fact that the child holding a "Need money 4 school" sign is black. Choosing to draw a dark-skinned child to represent a school system that is 80 percent minority on its face seems like a reasonable choice. But was the depiction disrespectful? Did it recall an era when cartoonists regularly used exaggerated features to demean African Americans? The answer is "no" to both questions. Allie's child is charming, and the dubious expression on his face perfectly captures the message of the cartoon. Rather than argue the merits of the point made in the cartoon—that school funds should not be diverted into developers' pockets—critics found it easier to turn the issue onto the explosive topic of race. The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists is well aware that depicting ethnicity in cartoons can be problematic, but in this case Allie handled it with skill and sensitivity. Accusations of racism can unfairly demean opposing viewpoints and undermine the spirit of free speech. What's more, baseless attacks undercut attempts to fight real racism when it rears its head.

AND THEN THERE’S CHARLIE HEBDO No cartoonist

in the world offends as regularly as the Parisian satire magazine, Charlie

Hebdo. And its front-page cartoon in the wake of Hurricane Harvey was a

beaut (at the upper left in the adjoining exhibit). Leading the charge was Sebastian Gorka, late of the Trumpet’s White House staff, who said: “Americans—including Texans—died to librate the supine French from the Nazis. This is the thanks we get? A disgrace.” Someone pointed out a submerged historical gaffe: the French saved America during the Revolution before America saved the French in World War II. But no matter. One Tweeter’s response (in italics): Don't get me wrong, I recognize why this cover is so offensive to those suffering from Hurricane Harvey, to southerners, and to America. ... [Particularly] Americans from southern states. ... Charlie Hebdo can publish whatever it wishes, and we have the right to like or dislike it. Yet while we should articulate why we dislike it (as I just did above), we shouldn't react with rage. For a start, by doing so we play to the magazine's raison d'etre: its cultivation of controversy and rage! As its masthead explains, "Charlie Hebdo c'est un coup de poing dans la gueule. Contre ceux qui nous empêchent de penser." Translation: "Charlie Hebdo is a punch in the face against those who prevent us from thinking." ... After all, arguably the most important conservative cause today is our opposition to censorship and anti-free speech sentiment. And our credibility will be crucial if we're to convince others to resist the Left's ideological prison. But when conservatives resort with rage to a cartoon, we delegitimize our credibility. It suggests that we're all for free speech, just not all the time. We also look hypocritical. Consider that just one week ago, Charlie Hebdo published a cartoon attacking Islam after the Barcelona attack. [The cover to the right of the Nazi cover.] How many American conservatives smiled at it and how many American Muslims were saddened? That cover uses a victim of the Baracelona terror attack to mock Islam as the “religion of peace” when some of its adherents ran down innocent civilians walking along the Ramblas in Barcelona. Miqdaad Versi of the Muslim Council of Britain chimed in with this (in italics)—: Because rage is the sword of those who seek chilled speech. As evidenced on college campuses, the Left revels in using abuse and authoritarian morality to chill the honest contemplation of others. ... And whether they know it or not, their endgame is a dominion of drones displacing a society of speakers. But consider one final point, Charlie Hebdo's mission statement: "Pour être heureux, Charlie Hebdo dessine, écrit, interviewe, réfléchit et s'amuse de tout ce qui est risible sur terre, de tout ce qui est grotesque dans la vie. C'est-à-dire de presque tout." "To be happy, Charlie Hebdo draws, writes, interviews, reflects and enjoys all that is laughable on earth, and of all that is grotesque in life. That is to say, almost everything." By their own words, Charlie Hebdo's first priority is self-amusement! And just as they have the right to be happy, it's in our society's interest to not overreact. Evidently, Charlie Hebdo has more than one mission statement.

CONSERVATIVES MUST HAVE THEIR DAY—and their chance to slander the Left as both Tweeters quoted above do so casually, as if everyone agreed with them. Oddly enough, just below the Charlie Hebdo covers is a cartoon by America’s Matt Davies that makes somewhat the same point as Charlie’s Barcelona cover. To the best of my knowledge, no one objected to it. Although, undeniably, American Muslims must have been discouraged.

CANIFF SOLD OUT This may not be worth the headline—maybe only a sentence (maybe two); so here goes: my biography Meanwhile: The Life and Art of Milton Caniff Creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon is virtually sold out. The publisher, Fantagraphics, has no copies of the book in its warehouse; if you order one, Fantagraphics will send off to England, where a distributor has a few copies left—or to Diamond, which reportedly has a couple dozen left. I have four copies left. After that, it’s completely sold out. Congratulate me. This has happened before, of course. Two of my books published by University Press of Mississippi—The Art of the Funnies and The Art of the Comic Book—have been sold out for some time. But “sold out” in these cases doesn’t mean “no longer available.” If you order one of those from UPM, they’ll perform an instant printing and send you a copy almost at once. I have a couple copies in the Rancid Raves Book Grotto, but UPM has none in its warehouse. I suspect, however, that they have copies of Accidental Ambassador Gordo: The Comic Strip Art of Gus Arriola. The other titles had such small press runs that it was easy to sell out; but Gordo was published in almost twice the number that UPM normally prints. And Insider Histories of Comics still has plenty in stock at UPM because it’s only three years old.

ODDS & ADDENDA An American, Matt “Aristotle” Burns, proved once again to be the best at pretending to play guitar at the 22nd Air Guitar World Championships in Oulu, Finland. He successfully defended his previously won title in the finals against 15 competitors, reported the Associated Press. “The Air Guitar World Championships started as a joke, but has grown into an annual celebration of guitar-miming chordeographers that draws people to Finland from around the world.” The Lone Ranger was a mystery to its 1938 fans, according to a report in Radio Mirror magazine, September 1938. Starting in 1933 on radio with three linked 15-minute programs a week, “The Lone Ranger” became the surprise box office hit of 1938 when a 15-chapter serial was launched by Republic Films, which, to perpetuate the mystery of the mystery man, refused to disclose the identity of the actor who played the character. On the radio show, actor Earl Grasser played the part. But fans didn’t know who acts as the Lone Ranger in the film. At the Denver Health Medical Center, five nurses were suspended recently for opening a body bag to admire a man’s genitals. “Genitals” is, of course, a polite word for pecker, dick, peter, and, anatomically, penis. The guy was, at first, just incapacitated by his illness; by the time he died, word about his endowment had spread among nurses, so some of them visited his body bag to verify the rumor. Then they talked about it and were overheard. They were suspended for inappropriate leering. And they say size doesn’t matter. “Soon the day will come when each and every tv show and movie will be available exclusively on its own stand-alone streaming service,” proclaims Esquire. Now that Disney has announced its own streaming service, come 2019, that’s the only place we can find the Marvel universe and Star Wars movies.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO The Latest Alarm results from the discovery that tattoos clog up sweat glands. That means nature’s air-conditioning system can’t work with tattooed people. Instead of sweating to get cool, they just do a slow burn. And where does the sweat go? It just builds up in the body until—presto!—it suddenly explodes out of the person’s ears and nostrils. Poof.

THE NEW YORKER AT ESQUIRE Bob Mankoff, erstwhile cartoon editor at The New Yorker, has been listed as “Cartoon and Humor Editor” in the last three issues of Esquire, June/July, August and September. As we reported in Opus 365, Mankoff signed on with Esquire the day after he left his office at The New Yorker. Esquire heralded Mankoff’s arrival with editorial flourishes in the June/July issue: “From its inception to the mid-1960s, Esquire published thousands of cartoons, as well as many humor pieces. Dry wit, droll takes, good jokes, dripping irony—that’s us. In an effort to amp up the fun, Bob Mankoff joins the staff this month to help us reintroduce and reinterpret that legacy.” But neither that issue nor the next had any cartoons in it. Humor maybe but no cartoons.

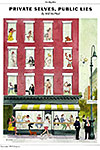

Despite the cartoon void in the June/July issue, Mankoff continues to advertise: “It’s time for another great American magazine to have great cartoons,” he says in that issue. Right. It’s been time, now, for several months if not years. But no cartoons in the August issue either. Then in the September issue—at last!—we get cartoons! Across the top of the cover, the announcement screams, with the two o’s in cartoon acting as Esky’s eyes. (Nice that Esky, the bulbous-eyed old roue mascot of the magazine, should be used in this manner: he was invented by a cartoonist, namely E. Simms Campbell; see Harv’s Hindsight for May 2013, “Withdrawing the Color Line.”) Inside, two cartoons—both full-pagers, both in color. No—wait: then there’s a two-page “essay” in a vaguely cartoony format. Four pages of cartoons! (We’ll show you in a trice.) Not to mention various random stabs at humor in the opening pages, which we’ve re-positioned just below the cover announcement in the accompanying display. I’m not sure these specimens live up to the billing Mankoff had been flaunting in the months before. In anticipating his role at his new home, Mankoff said, “It’s important to use these editorial muscles that I’ve developed over all these years.” Esquire editor-in-chief Jay Fielden was wholly on board: “What he’s going to do is invent an entirely new look and sensibility in cartooning by upping the aesthetics and embracing a wide set of fresh voices.” “Mankoff will edit humor stories, pitch ideas, draft cartoons and recruit a new generation of humorists to Esquire and Esquire.com,” said Alexandra Steigrad at wwd.com Ambitious goals. “I want to try something new,” Mankoff said. “I’ve had this idea for a long time, but in the New Yorker context, it didn’t make sense.” His new idea: what if he were to work closely with a handful of different cartoonists every issue, in a process that he says would “feel less hierarchical” and “more productive”? What if? “Combining different skill sets could be very powerful in … heightening the quality of humor,” Mankoff says. “That’s my ambition through collaboration. ... “I look forward to working with new talent, too,” he went on. “It will be a commission process, essentially, like working together on an article. We will all have skin in the game, writers can be emboldened — and my door is open.” His goal is to spotlight each humorist’s voice by helping them to develop their material. He imagined his new approach could “reinvigorate the ecosystem of magazine cartoons.” But on the surface, his new approach looks awfully like what he did at The New Yorker, where he often worked with cartoonists, particularly new ones, to sharpen their drawings or captions.

JUDGING (admittedly, unfairly) from the four pages of cartoon features in Esquire’s September issue, this new generation so far consists of five New Yorker cartoonists—Will McPhail, Bob Eckstein, Matt Diffee, Paul Noth, and (that small cartoon signed Dd), Drew Dernavich. These are relatively new New Yorker cartooners, but, still, they’re scarcely fresh talent.

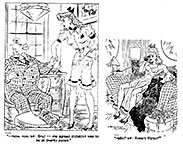

So to start with, Mankoff raided the stable he’d been working in for nearly 20 years, recruiting for Esquire assignment some of the newer faces at The New Yorker instead of finding genuinely “new” talent. Well, what did we expect? One must begin somewhere.... What about “heightening the quality of the humor”? All four of the cartooning attempts are, well, amusing. But amusing ain’t necessarily funny, and we’re accustomed to the sort of funny that can provoke a laugh. Not always, not every time maybe, but potentially. None of Mankoff’s new generation cartoons seems particularly provocative. Take McPhail’s “Private Selves, Public Lies,” that full-page picture of apartments over a coffee shop. McPhail shows us the private lives of some of the citizens by turning us into Peeping Toms, watching through the windows what the apartment residents are doing when they don’t think anyone is watching. Then he shows what those same people do when they go outside for a cup of coffee. At the upper left, a woman is yelling at her baby; but out in public at the lower left, she’s smiling and playing with her baby. Nothing startling about that. It’s just human nature. All mothers yell at their babies who they otherwise love. On the second floor at the right, a naked woman is throwing a lamp at a man; they appear below in the coffee shop, kissing. They’ve made up. Two of those we spy on are shaving their pubic regions; in the coffee shop, they’re drinking and laughing. Was the shaving preparation for anticipated canoodling? The woman using the bong on the first floor turns out to be a cop on her beat. The bearded guy gorging himself with pizza is a jogging health nut. And the fat bald guy watching porn on the top floor is, when in public, a preacher, pitching the Bible next to the lamp post. What fun, eh? Amusing as an expose of human nature and individual hypocrisy, but, amused though I am, I ain’t laughing yet. Bob Eckstein’s “Game, Set ... Naptime” is not as amusing as McPhail’s expose. Maybe the devices he suggests would speed up the game of tennis. Interesting as a satirical comment on tennis as televised, but no big laughs here. And Diffee and Noth’s two-page cartoon essay on barbecuing is similarly amusing in a mildly sarcastic way. But not all that funny. No boffo laughs here. Not that all cartoons should go for boffo laughs. But some of them, surely, should aim at more than being simply “amusing.” Doubtless, this harangue is premature. It took Mankoff two issues with no cartoons to reach a third issue with three (maybe four) cartoons. Overnight results is not his forte. So we must reconcile ourselves to waiting a little longer. Maybe by the October issue.... And

there is a whole 3-page section of humor in the September issue—short amusing

essays with comical illustrations. So Mankoff is doing his Humor Editor job,

too.

MEANWHILE, hereabouts we’ve posted ten cartoons of the more time-honored single-panel cartoon sort, the humor of which is somewhat higher on the scale of funny than merely amusing. Elucidation through contrast.

What do all ten have in common? In all of them, the comedy comes as a surprise: the captions explain the otherwise puzzling pictures—or vice versa—and the revelation, suddenly exposed, bursts in the brain as a small explosion—i.e., laughter, or something close to it. No such fireworks go off in Mankoff’s first batch of Esquire cartoons. They’re a lot calmer.

But more pertinent to our comparison, the comedy in most of these cartoons involves taking a slice of everyday life—sometimes just a cliche expression—and exaggerating a little. Nothing like the situations depicted here will you ever see in real life. And the exaggeration is at the core of the comedy. The three Esquire cartoons do not exaggerate—and if they do, not as much as our crop of ten. The Eskytoons are portraits of actual life, closely observed. They are, perhaps, more authentic because they are not as extreme. But more whimsy than whamsy. We may conclude, then—for the time being—that Mankoff’s idea of a new ecosystem of cartoon comedy finds humor in everyday situations without exaggerating. The humor is there—everywhere—waiting to be uncovered by close observation. And cartoonists will do the observing and uncovering. It’s not a bad idea. The objective is to make people smile at themselves rather than to laugh at themselves. And we could all do with some of both.

FitNOOt. In one of several recent articles about Emma Allen, the 29-year-old who replaced Mankoff as cartoon editor at The New Yorker, it emerged that Mankoff left the magazine with the express purpose of taking a position as cartoon editor at Esquire. Before that intelligence dribbled out, we all assumed that (a) Mankoff simply retired from his New Yorker post after 20 years or (b) was fired (or invited to resign) and subsequently leaped to Esquire because he didn’t feel he was done with editing cartoons yet. So now, we just don’t know.

CLIPS & QUIPS “What do you think is the meaning of true happiness? Is it money, cars and women? Or is it just money and cars?”—Bill Watterson A grammatically fascinating statement regarding a research assistant and where she parks: “She comes and parks in whoever’s not here’s space that day.” “I don’t feel I am getting older; I feel I am getting closer.”—novelist Rachel Cusk

CARTOON BANK GYPS CARTOONISTS Bob Mankoff invented the Cartoon Bank, and it immediately proved to be a substantial source of “passive income” for cartoonists by marketing their cartoons that had been rejected by The New Yorker (which receives 500-1,000 submissions a week but publishes only 14-17 in each issue of the magazine), selling originals and licensing cartoons for use in corporate newsletters and the like. Conte Nast, which owns The New Yorker (which owns the Cartoon Bank), took over management of the Cartoon Bank in 2008, and since then, cartoonists’ income from the Cartoon Bank has dwindled sharply because, says Seth Simons at pastemagazine.com, of poor—virtually nonexistent—business practices. What follows is mostly excerpts from his article. The Cartoon Bank was a windfall for cartoonists, who in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s witnessed the market for single-panel gag cartoons dwindle from a handful of publications to virtually only The New Yorker. At first, says Simons, “some cartoonists received monthly checks as high as $8,000; others regularly saw one or two thousand dollars. Today, even those who saw the highest royalties receive only a few hundred dollars per month.” Mankoff, a cartoonist for the magazine since 1977, founded the Cartoon Bank in 1992. It was the early days of the internet, which he had a feeling might prove a game-changer for his fellow cartoonists. Mankoff recalled: “I said, let’s make a business out of the all the cartoons that were rejected.” He secured a small business loan, hired employees and deployed technologies new and old to create a database of thousands of cartoons. Under Mankoff’s leadership, the company sold first-time publication rights, reprint rights, online rights and original cartoons. The market was individual consumers as well as businesses; if you ran a dental association, for instance, you could easily find dental-themed cartoons for your monthly newsletter. Fees, which ranged from $100 to over than $1,000 for a single cartoon, were split 50-50 with cartoonists. Mankoff reported $200,000 in revenue that year; by 1998 that number reached $1 million, and $2 million the following year. In 1999, the Times noted that the Cartoon Bank’s website received 100,000 hits a day, “with the average lasting ten minutes.” The business was successful enough that The New Yorker bought it from Mankoff in 1997, the same year he succeeded Lee Lorenz as Cartoon Editor. “At the height of the Cartoon Bank,” Mankoff he said, referring to the mid-2000s, “it had revenues of seven million dollars. The cartoonists were receiving over two million dollars.” The company had nine full-time employees, including one dedicated to sales of original cartoons and two dedicated to licensing. Another oversaw the creation and sale of custom books to trade associations and other enterprise customers. Mankoff, who had a bird’s-eye view of the company’s financials, spoke of cartoonists receiving residual income to the tune of $30,000 to $40,000 annually. In 2008, Mankoff handed off leadership of the Cartoon Bank to Condé Nast, who, it quickly became apparent, planned to operate the business with a lighter touch. “I consulted with them for many years after I left, urging them to support this business and commit to this business,” Mankoff said. “For their own reasons they decided that they’re not supporting it. There aren’t really any employees left. And those people who used to do those things”—licensing, custom books, original art sales—“have been let go. The people there are absolutely well-meaning, but they have no real idea of what this business is, who the cartoonists are, how you might leverage and maximize it.” Over the following years, the well dried up. The cartoonist who described an $8,000 check he received early on said he now sees at most a few hundred a month. Simons says he spoke to several cartoonists, none of whom thinks Condé Nast willfully stripped away their residual income. What they see instead is a typical story of corporate mismanagement and neglect. The website has become confused and difficult, almost impossible, to order cartoons from. Executive churn might be cause of the problem. When Mankoff gave up the reins, he was succeeded by a string of executives who generally did not last long in the role. None were cartoonists. This effect was compounded by a diminished sales staff. The Cartoon Bank isn’t actively working to make sales.

NEW YORKER CARTOONISTS ARE PAID IN TWO TIERS. More established artists receive $1,450 for a cartoon, while the rest receive $700. The sales of original artwork bring cartoonists some of their largest one-time payments, often as high as $2,000 or more. Until January 2017, sales made through the Cartoon Bank were split 70-30 between cartoonists and Condé Nast. In December, cartoonists were sent a contract revising that split to 50-50. Condé Nast also recently stopped warehousing original artwork, leaving that responsibility to the cartoonists themselves. “They just, like, fired all their archivists,” said one cartoonist. “There was no place to put it. People who were trying to reclaim their archived cartoons were being told that they had been lost. So now we’re at a place where it’s just, ‘Make your own high-res scan at home, email in the high-res and that’s what we’re going to run in the magazine. You’re responsible for storing and archiving your own artwork. We will let you know if a collector wants to buy your cartoon.’” “That’s fine,” this cartoonist said. “You’re streamlining your production pipeline or whatever. But then to be told, ‘By the way, the privilege of being told that a collector is interested in your work is 50% of the sale price, and you have to package your own artwork and mail it off yourself,’ was offensive.” These factors, in tandem with the company’s diminished focus on marketing and sales, mean cartoonists today receive noticeably fewer of those large, and meaningful, paychecks. Through a spokesperson, Condé Nast described the revised revenue split as “reflective of industry standards.” Mankoff said this isn’t quite accurate: “That is the standard provided you actually have personnel selling original art, but they fired those people. In other words, it’s standard when you have an agent, who is knowledgeable in the field and actively contacting potential customers for the product.” This is no longer the case at the Cartoon Bank. “We had an original art salesperson,” said the former staffer, “but they were let go, and we just took incoming calls after that.” But the dwindling revenues from original artwork pales in comparison to the near-disappearance of licensing fees. Mankoff, sympathetic to the plight of the cartoonists, for whose benefit he’d invented the Cartoon Bank, offered to buy it back—and guarantee Conte Nast is current cut. But they weren’t interested, he said. Through a spokesperson, Condé Nast emphasized that it is committed to growing the Cartoon Bank. But the company declined to offer any specific reason as to why the Cartoon Bank’s revenue has fallen so dramatically. The cartoonists, meanwhile, are prepared to take matters into their own hands. “I’ve told Condé that I am certainly exploring alternatives for the cartoonists,” said Mankoff, who recently joined Esquire as that magazine’s first Cartoon and Humor Editor (he’s also developing a humor robot, Botnik, with Clickhole founding editor Jamie Brew). “Neither The New Yorker nor Condé own the material—the cartoonists own the copyright for the material,” he said, qualifying that he’s not trying to poach the site for Esquire’s parent company, Hearst. “We’re still hammering out the details,” said New Yorker cartoonist Tom Toro, who’s involved in the discussions, “but whatever it ends up being, this re-envisioned entity will aggressively market our work, simplify the customer experience, and compensate artists fairly.” Simons’ complete article, from which I’ve poached almost all of the foregoing, can be seen at https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2017/09/how-conde-nast-put-the-squeeze-on-new-yorker-carto.html

TICS & TROPES As a regular reader of this picayune prose, you are doubtless aware of my rampant liberalism, so you will be astonished to learn that the Republican Party routinely sends me various communiques accompanied by requests for donations. Last week, I received another “Survey Questionnaire,” this one on the “Trump Agenda.” Naturally, I filled it out and returned it (albeit without making any donations). I do this every time I get one of these questionnaires. I answer all the questions guided by my flamingly progressive attitudes. Asked to rank a series of agenda items, I gave no rank at all to any of them, beginning with “Reverse President Obama’s unconstitutional executive orders.” All of the listed items are phrased in this way; scarcely neutral statements, they all contain within themselves the Trump Agenda posture. “Unconstitutional” tells us what we are supposed to think about Bronco Bama’s executive orders. Cute stuff. So why do I bother? Sometimes it’s because the response envelope is franked, so when I respond, I’m costing the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm money. But even if I have to use my own stamp, I rub my hands in glee, thinking I’m making the computer scoring mechanism at GOP headquarters hiccup a little. It has no category for my answers. All for the good of the Cause.

PLAYBOY LANDMARKS “Playboy is legendary,” Tony Sokol begins at denofgeekcom. “The magazine transformed publishing, changed mores and challenged social and sexual boundaries. And it did it with a Mad Men flair and a sexy foldout.” That’s the introduction to an interview with author Patty Farmer, whose new book, Playboy Laughs, focuses on the comedy, comedians and cartoons of Playboy. Mostly, judging from the interview, she focuses on Playboy Clubs. Says Sokol: “Hugh Hefner transformed live comedy by starting an international circuit for standups with his Playboy Clubs. Hef stole comic artists from Mad magazine for one of his own called Trump. His tv shows, ‘Playboy Penthouse’ and ‘Playboy After Dark,’ broke funny new voices as well as racial barriers in the pre-Civil Rights days of segregated entertainment, and glass ceilings contemporarily with the feminist movement.” Among the things Farmer says: “Hefner opened the Clubs in 1960, but he had the tv show in 1959. I really think Hugh Hefner is one of the most colorblind people you’d ever meet. He, over and over, hired the best talent. As the great comedian Dick Gregory said, Hef didn’t care if you were black, white, or purple, if you could sing a song or tell a joke or swing an instrument. With the tv show, he integrated. This was all pre-1964 Civil Rights Act. He had Nat King Cole on, sitting down talking to a white woman, and the phones just exploded. Networks threatened to pull the show. Sponsors threatened to pull their advertising because he had done that. He was shocked that people would be so small-minded. “He was constantly shocked,” she goes on. “When he opened the Clubs in 1960, he had Dick Gregory, a great, young black comedian. He went on in front of an all-white audience and even the audience was shocked. Not only were they white, they were a bunch of meatpackers from Alabama. But once Dick went into his routine they wouldn’t let him off. The head of the Club actually went up to the Playboy Mansion to get Hugh Hefner and said ‘You have to come over to the Club because history is being made.’ By the time they got back, Gregory had been onstage for three hours. Comedians are a bunch of hams. You give then a stage and an audience and nobody’s telling them to get off and they’ll stay on forever. But the audience really loved him.” The first comedian on the tv show as Lenny Bruce. “Hef loved him and put him in the Clubs. He took him out of the Clubs when Lenny went over the top and started making a lot of enemies, mainly the police. They threatened to close down clubs where Lenny performed. Hef went on to support him in other ways. He helped financially and legally. Hef is first amendment all the way, free speech. He sent attorneys around the country to defend Lenny. But you couldn’t protect Lenny from himself. We lost him way too young, what was he 42? But Hef tried his best. “But people like Richard Pryor, who started out clean cut and collegiate, and George Carlin with a tie and short hair and a sweater. He was playing the Playboy Clubs, and then he got into the seven words you couldn’t say on tv. Hef had to tell him, ‘George I love you like a brother. I will go and watch you wherever you are when I’m in town, but you can’t play at my clubs anymore.’ Because, believe it or not, the Playboy Clubs were very clean. You had to stick to innuendo, maybe, but no cursing, you had to dress up. You had to be very respectful. Hef ran a club that he wanted the martini culture set to be able to come to during the day but he wanted the guys to be able to bring their wives and girlfriends at night, be well-entertained, but not be embarrassed by anything.” Sokol wondered about the mob influence: “Almost all clubs have some kind of mob influence. How did Playboy get around that?” Farmer’s answer: “The two main clubs were in Chicago and New York, but if you owned a nightclub in almost any city in the U.S. at that time, the mob was there in some form or another. Hef did have members of a certain family sit down in his office and say they really thought they should do some business together. Hef, in his laidback manner, said: ‘I have the eyes of the Catholic Church and federal and local government constantly on me. Do you really think I’m the right partner to be in business with?’ Even though they were mobsters, they were smart enough to realize it wasn’t anything they wanted to push because they were trying to stay out of trouble themselves.” Farmer talked to “hundreds” of comedians. They were always serious. They were forever worried that their talent for comedy would leave them. Cartoonists, on the other hand, “were hysterical. They reminded me of old kids, teenage boys who got older but never grew up. They were funny, all of them.”

Fitnoot. Dick Gregory died August 19, and Elahe Izadi at the Washington Post said Gregory had desegregated comedy, quoting Kliph Nesteroff, author of The Comedians: “Prior to Dick Gregory, stand-up comedy was segregated. There was a separate nightclub circuit for black comedians and another circuit for white comedians.” After Dick Gregory, there was only one circuit, black and white, and black comedians played white clubs just like white comedians. “Never before had white America let a black person stand flat-footed and talk to white folks,” Gregory said in 2006. “When I started, a black comic couldn’t work a white nightclub. You could dance and you could stop in between the dance—Pearl Bailey could talk about her tired feet or Sammy Davis Jr. could tell a joke—but you could not walk out and stand flat-footed and talk with white America—then the system would know how brilliant black folks was.” Gregory’s success opened the nightclub door for Bill Cosby, Godfrey Cambridge and Richard Pryor and others. Gregory was not just a comedian, Izadi noted: “As an activist in civil rights, he marched in Selma, was shot in the leg in Watts, jailed in Birmingham. He ran for Mayor of Chicago, then president. Sometimes he had to cancel gigs at the last minute because he was in jail. And he spent hundreds of thousands on civil rights causes.” Playboy asked him: “Can you afford to keep up this kind of outlay on the income from your irregular nightclub appearances?” “Can’t afford not to,” Gregory said. Another comedian just died. Jerry Lewis. At the age of 91. He died the day after Gregory left us. Many eulogized his brilliance as a manic comedian. I think he was better as half the Martin (Dean) and Lewis team. They broke up in 1956 after about ten years together, but I don’t think Lewis ever quite got over himself. In later years, he did an annual Labor Day Muscular Dystrophy Telethon, but I can’t help thinking he did it for himself—for his own celebrity—not for, as he always said, “my kids.” Lewis always had to be the one in the spotlight. That’s why he was always “showing off”—telling jokes and making funny faces.

RAGGED AND FUNNY The Trumpet, who has been bugling about wiping North Korea off the face of the planet but hopes, he says, to resolve the dilemma diplomatically, has yet to nominate people to be the U.S. ambassador to South Korea, the assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs and the assistant secretary for Asian and Pacific security. As I mentioned before, this may be part of his deliberate attempt to reduce the federal bureaucracy, but if so, he’s picked particularly sensitive areas to start with. Moreover, his failure to fill the agency jobs that require Senate approval—namely, relatively senior positions—is sabotaging his own agenda. Without senior leadership, the minions run things, and many of those minions are Obama people, who aren’t likely to act enthusiastically for the Trump program. Ha. Gotcha.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

HOWARD CHAYKIN is back with The Divided States of Hysteria, a story, he tells us, that he concocted when he still expected Hillary Clinton to win the White House. His concerns then—“as the book indicates”—were “fear of international and domestic terrorism and an aversion to identity politics.” Now, with the Presidency in the grip of “right-wing ignorance and hypocrisy-drive rage ... the book seems almost naively cheerful and filled with hope. Go figure.” As the first issue opens, the Prez and most of the Cabinet were assassinated a month ago. And that is about as straightforward as this title ever gets. We meet the ostensible protagonist, a shamelessly philandering security agent named Frank Villa, but his having wife and family and a mistress is about all we learn about him. Most of the book is given over to the lawless behavior of a quartet of would-be bad guys, who are arrested and jailed. We don’t see much of Villa. And the second issue is more of the same—namely, long stretches of description and political rant in captions accompanying pictures of airplanes in flight and buildings on the ground. At the end, we learn that Villa has been recruited to perform some sort of world-saving mission, and he needs the help of the four bad guys from the first issue, who, as the second issue ends, are leading a riot in the prison. The captions and the speeches of an endless stream of characters are laced with the vilest profanity and racial bigotry—signals of authenticity, we assume— but we can’t tell if we’re supposed to remember these people or not. As usual with Chaykin, some of the pictures depict sex being deployed as a weapon. But

these distractions are of little consequence: the giant distraction in the

title is in Chaykin’s use of computer-generated imagery for all the

backgrounds, buildings and equipage. Not photographic but linear. This maneuver

creates impossibly detailed pictures—impossible to view and comprehend. The

only pictorial elements In short, Chaykin’s considerable ability as a storyteller is being undermined by the digital devices he resorts to. He is being defeated by the machinery he has adopted and deploys so deftly. He has created a showcase of CAI that is so compulsively utilized that it smothers the story—as we can readily observe in the pages at hand.

IN DARK DAYS: THE FORGE No.1, writers Scott Snyder and James Tynicn IV manage to do everything that our criteria suggest they ought not to do in a first issue. This seems to be a Batman title, but others of the DC universe get more air time than he does—Green Lantern chiefly, but also Aquaman and at least two others who are not named and whose appearance, modernized and slicked-up, I don’t recognize. Mr. Terrific? Hawkman? There are several completed episodes but none of them prove much about the characters (except maybe the one involving Mr. Miracle, proving he’s stronger than Superman). And it ends with the Joker doing his hysterical giggle. The entire ensemble goes muttering along with narrative captions about “something coming—something big, something mysterious. ... A message from the gods, perhaps?” And on every page, we are reminded that this menace lurks. In short, it’s too cryptic and therefore incomprehensible. If we didn’t already know all the characters, not much happens here that makes us care about them. Brilliantly drawn by a congress of pencilers and inkers, but too mysterious to engage me. Brandon

Thomas’ Noble No.1 from Lion Forge is no better. None of the

characters are named. In the opening sequence, we meet a woman and her

children, and she says she’s going to get Daddy. Then the rest of the book is a

flashback in which we see an unnamed character in an iron mask getting beaten

up by other unnamed characters. He fights back. Page after page of wordless

combat. Lots and lots of hitting and some shooting of small arms. Flickering in

and out of the fisticuffs are panels depicting a kid yelling “Daddy.” If we

consider each successive Who or what is Noble? Don’t know. The guy in the iron mask? Maybe. The woman, who shows up again on the last page, vowing to go get Daddy? Too much mysteriousness. Cryptic and therefore incomprehensible. Roger Robinson’s art is crisp and forceful, and Juan Fernandez’s colors add modeling in the same chiseled manner. But the pictures aren’t enough to bring me back.

SEAN MURPHY returns with the October release of Batman: White Knight, which he both wrote and drew. It will be a treat to watch him at work again. He may be the best comic book cartoonist (that is, someone who writes and draws his own stories) around. Shirtless Bear-Fighter is back with a second issue. I was initially attracted by Nil Vendrell’s crisp drawing. I still am. That and the character’s name. But Jody Leheup and Sebastian Girner’s story has continued to deteriorate into improbable fantasy. Somehow Shirtless became enraged against bears (the implication is that they killed a little girl he was fond of); and the bears became super-powered. Only Shirtless can defeat them. And with that, the tale goes beyond my ability to tolerate unlikelihoods. The third issue is a little better but the fantasy is still highly improbable. We do, however, have the dubious pleasure of watching the villain of the piece take a crap in a gold-plated toilet. Oh, and Shirtless walking around naked again with pixels covering his crotch. Exciting, eh? I

bought all four issues of the latest Shaolin Cowboy series. Upon

reaching the end of the fourth issue, I’m no wiser than I was before. The

Cowboy engages in endless violence, fighting I know not what. Someone thinks

there’s satire in this—in the things the Cowboy attacks perhaps—but there’s too

much of it. Geof Darrow’s art is too much—too copious, too overwhelming.

We can’t see the trees for the forest. Here are two pages from the last issue.

Yes, there’s lots of detail, lots of spewing blood, lots of violence. Lots to

look at. But the pictures make no particular sense beyond showing violence,

blood, and detail. And the second issue of Jimmy’s Bastards has fallen far away from the James Bond lampoon it began as. No action in this issue. Just talk, and Jimmy leering. Jim Mahfood (another cartoonist who draws and writes his own stuff) is up to No.4 of his Grrl Scouts, and the book is increasingly manic and freeform. It’s wonderful to watch. The pictures are marvelously inventive, but the story is carried almost entirely by the speeches characters make in their balloons. With all the antic art on every page, though, I don’t mind at all the verbal dependency.

QUOTES & MOTS The Trumpet was the subject of 1,060 jokes by late-night tv hosts in his first 100 days in office. Bronco Bama was the target of 936 jokes during the same time period; GeeDubya, 456; Bill Clinton, 440. So it’s not just the personality of the Prez that sparks all the fun-making: instead, joke-making is just getting more profuse as time warps on. “When I was young, I used to think that wealth and power would bring me happiness. I was right.”—Gahan Wilson “The most courageous act is still to think for yourself. Aloud.” —Coco Chanel

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy SINCE WE

SATURATED the digital ether with political cartoons and other rampant ravings

about governmental mischief last time, just a week or so ago, we don’t have

much left for this time. Not that there haven’t been shattering events worth

noting. So we’ll note them, beginning with our first visual aid (but we won’t

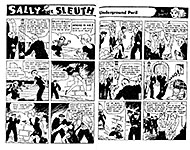

rant on too long this time, I promise). Apart from the Trumpet’s self-promotional visits to hurrican-torn Houston, his announced intention to shitcan Bronco Bama’s executive order to Defer [Deportment] Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)—immigrant kids who came here with their undocumented parents, the “Dreamers” who’ve assimilated into the American way of life, including, for some, service in the military—was among the most upsetting of the news events of the last couple weeks. Clay Bennett at the upper left of our display memorably captures the sense of impending doom that Dreamers must have been feeling in the days before Trump actually made his predicted announcement. Appropriately, Bennett chose a bedtime metaphor for his message about Dreamers. Next around the clock, Gary Varvel offers a telling metaphor for what Trump did: when he announced his intention to cancel Obama’s executive order, he said it wouldn’t go into effect for six months in order to allow Congress to concoct legislation that would do the right thing by the Dreamers—in effect, abandoning the Dreamers on Congress’ doorstep in the classic image about abandoned babies. Only the most hopeful of observers expect Congress to do anything: the lawmakers have been facing the same situation for at least 16 years and have done nothing—and the concept of the Dreamers was, if I remember, in the bill that was introduced by the Republicons’ own GeeDubya. But the Trumpet, seeking to cover his ass both ways, announced a few days later that the Dreamers shouldn’t worry. They’ll be safe, he assured them. If Congress does nothing, Trump promised to revisit the situation. It was a stupid maneuver. While it assuaged the Dreamers, it took the pressure off Congress—pressure Trump himself had engineered. The Trumpet apparently does not recognize political pressure when he creates it. His effort to cancel out the offending executive order was made solely to appease his “base,” to whom he’d promised he’d throw out the Dreamers. He had no other purpose—no genuine intention to force Congress to do anything. Once he’d assuaged his base, his job was done. At the lower right, Lalo Alcaraz in his comic strip La Cucaracha dismantles the contention that undocumented workers are taking the jobs “genuine” Americans who are out of work would do—if the jobs weren’t already being done. Lalo frequently takes political positions in the strip; here, he does so with stark white (blank—empty) space making the case. Next Scott Stantis provides an image for the Trumpet’s latest “victory”—his joining the Democrats in opposing the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm’s plan for increasing the debt ceiling limit. The GOP wanted to postpone a decision for 18 months so that the debate about it would take place after the crucial 2018 mid-term election, thereby avoiding this contentious issue during an election year when they’d be particularly vulnerable. The Democrats wanted a short-term increase (three months until December) in order to stage the debate just before Christmas when shutting down the government in the event of a stalled process would exert the most pressure on the GOP. Shutting down the government would be a lump of coal in the nation’s Christmas stocking. No one wants that. But the Dems got their way because the Trumpet, suddenly, and without any advance discussion with his Treasury Secretary, deserted “his” party, stabbing them in the back, as Stantis puts it. The debt ceiling increase, which effectively funds the government for the rest of the year but no longer, was tied to releasing money to help survivors of hurricane Harvey. Clearly, common sense suggests that with Texas and, now, Florida victims of horrendous hurricanes and in need of all kinds of help including government money, this was no time for more of the GOP’s usual idiocy about the debt ceiling. Pundits give the Trumpet credit for doping all this out and making a maneuver that ought to spur his ostensible party to behave more in ways to his liking. And so it would appear. The Trumpet’s dodge here may ultimately serve the country by increasing political pressure on the Congressional GOP to start working with the Democrats (and vice versa), as the framers of the Constitution intended. If that happens, I’ll be happy to tip my hat to the Trumpet. But I think Trump’s surprise maneuver was governed more by his instinct as a dealer than by any patriotic or political motive. He’s proud of his reputation as a deal-maker. And what he did here was make a deal. Making a deal was the important thing, not what the deal itself might be or portend. Making the deal means to Trump that he won, and he’s all about winning, not governing. It doesn’t even matter what he wins. Winning is the ultimate purpose in the Trumpet’s life. In any case, he shocked the hell out of Republicon leadership—which I think is a good thing in itself. And he made friends, however temporarily, with Democratic leaders. From this episode, the Republicons ought to take a lesson: they can’t depend on Trump. All year, the GOP leaders have refrained from castigating the Trumpet whenever he richly deserves it: they want to preserve an amiable relationship so he’ll sign into law whatever legislation they conjure up and send to the White House. Surely now they realize how foolish that scheme is: the Trumpet is unreliable. They shouldn’t depend on him. And they should castigate him whenever he deserves it (which is often). Foreign