|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 369 (August 9, 2017). This time down the rabbit hole, we have a monstrous whopper of a posting. Too much to read at one sitting, kimo sabe: so browse the list that ensues and choose your poison. We have long segments on three of the traditional venues for cartooning— comic strip cartooning with Tina’s Groove’s Rina Piccolo (including some very unconventional early cartoons), editorial cartooning with Pulitzer-winner Jim Morin (plus surveying the editoons of the last month or so), and magazine gag cartooning with Tom Toro of The New Yorker. We also examine the state of the cartooning industry, the emerging surreal weird at The New Yorker, a list of words that should be banned, and the untold history of Uncle Sam. And we review first issues of Jazz Maynard, Jimmy’s Bastard, Normany Gold, and Accell, plus reviews of three books, 20th Century in Cartoons, Hitler in Cartoons, and Cartoons Against the Holocaust. We conclude with affectionate obits for Joan Lee, Bob Lubbers, and “Fabulous Flo.” Yes, it’s too much. Lots of talk about comics. But that’s what we dote on—talk about comics. And here we do enough of it to satiate your appetite for a few days. So scan the following list to find topics that you are most interested in. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Houston Chronicle Fires Editoonist AAEC Denounces Chronicle and Hearst Sales of Graphic Novels and Comics Still Growing Comics No Longer a Security Threat Trump Quotes in Superhero Comic Conservative Economic Policy Fails

Tina Loses Her Groove Piccolo at Rhymes Vintage Piccolo Toons

IN THESE UNITED STATISTICALS Facts

ODDS & ADDENDA No Comics in EW Report on Comic-Con Pooh Banned in China Spider-Man Art on Display

WORD POWER List of Words That Should Be Banned

Twump and Pooty: New Comic Strip

PULITZER WINNER REFLECTS

Tangled Tale of Uncle Sam

THE STATE OF THE CARTOONING INDUSTRY

SURREAL WEIRD CARTOONS AT THE NEW YORKER The New Regime Sets In

The New Yorker’s Tom Toro Interviewed With Sampling of His Cartoons (Particularly anti-Trumpet)

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE First Issues of—: Jazz Maynard Jimmy’s Bastard Normandy Gold Accell

EDITOONERY The Month’s Antics in Political Cartoons

THE FROTH ESTATE What Roger Ailes Wrought

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Transpirings of the Last Month Or So

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews Of—: The Saint: The Man Who Was Clever The 20th Century in Cartoons Hitler in Cartoons Alan Moore’s Last Comic Book Two More Harry Potter Books

BOOK REVIEW Long Analysis and Verdict On—: Cartoons Against the Holocaust ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Mass Murder Stats

PASSIN’ THROUGH Appreciative Obits for—: Joan Lee Bob Lubbers Fabulous Flo Steinberg

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:. Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

HOUSTON CHRONICLE FIRES THE LAST STAFF EDITOONIST IN TEXAS Pulitzer Prize winning editorial cartoonist Nick Anderson was fired in mid-July as a cost-cutting measure by the Houston Chronicle, where Anderson had been the full-time staff editoonist since 2006. The year before, while cartooning at the Louisville Courier-Journal, he was awarded the Pulitzer, credited for his “unusual graphic style that produced extraordinarily thoughtful and powerful messages.” My recollection is that the Texas paper went looking for a cartoonist to replace Clyde Peterson, who was retiring after 41 years with the Chronicle—and Anderson, the most recent Pulitzer-winner, looked like a good replacement for the paper’s popular veteran. Anderson, 56, is taking this reversal of fortunes remarkably well. “The odds caught up with me,” he wrote on Facebook, alluding to the decades-long thinning of the ranks of full-time staff editoonists in America. With his departure, only about 48 editorial cartoonists work full time on the staffs of daily newspapers; that number was 101 just 9 years ago. “Ironically,” Anderson continued, “thanks to social media, my cartoons are seen more widely than ever. While the Internet and social media help spread my work widely, they also have made it harder for anyone in the news business to make a living. I was able to drive significant traffic to my employer’s website at times, but not on the same scale as the Facebook traffic. And traffic alone isn’t enough anymore. Newspapers are moving to a subscriber/paywall model. Unfortunately, the powers-that-be decided a full-time cartonist was not going to be a part of that model at the Chronicle. “I’ve had a good run,” Anderson finished, “and I’m grateful to have been a political cartoonist for so long. I’ve been extremely fortunate in my professional career. I really want to thank my readers for their encouragement, comments, and feedback. Even the insults and disagreements have been appreciated.” He will continue to draw editorial cartoons for his syndicate, the Washington Post Writers Group, which distributes them to more than 100 newspapers. But the resulting income is scarcely a living wage. Anderson began editooning at Ohio State University. While majoring in political science, he cartooned at the campus newspaper, the Lantern. In 1989, he won the Charles M. Schulz Award for best college cartoonist. He interned one summer with the Courier-Journal, which immediately recognized his talent. The newspaper created a position for him as an associate editorial cartoonist and illustrator after his 1991 graduation from OSU. “I didn’t want Nick to get away and get ensconced someplace else because he just seemed to fit us,” says David Hawpe, editorial director of the paper. “I think he has the kind of tone we want for our page – it’s a tone that’s not disrespectful, but it is provocative.” Anderson was promoted to chief editorial cartoonist in 1995. In

addition to the Pulitzer Prize, he won the Society of Professional Journalists'

Sigma Delta Chi Award in 2000, the 2011 National Press Foundation's Berryman

Award, and two-time winner of the John Fischetti Award from Columbia College

Chicago in 1999 and 2012. And he also earned recognition for his drawing style. Anderson has pioneered a method of coloring his cartoons. Using an advanced computer program, he creates digital paintings characterized by subtle textures and striking images. Because of his innovative use of the program, its manufacturer, Corel Corporation, has designated Anderson a "Painter Master." Anderson was president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists in 2007-2008. And his AAEC colleagues have scarcely forgotten him at this turning point in his career—:

AAEC Denounces Chronicle and Calls Anderson Firing Misguided As soon as Anderson’s lay-off became known, the Board of Directors of the AAEC released a statement on Nick Anderson and his firing—: The firing of Pulitzer Prize winning editorial cartoonist Nick Anderson is a misguided, short-term cost-cutting maneuver by the Houston Chronicle and Hearst Communications. The elimination of his position now means there isn't one on-staff newspaper editorial cartoonist in the entire state of Texas to provide local visual commentary and hold the state government accountable to its citizens. Editorial cartoonists are a historically important and powerful component of American journalism. Editorial cartoons are very popular with readers; they look to their local cartoonist to provide satirical observations of their representatives and government officials. Especially in these times where our country's free press is under attack by the current administration, the work of editorial cartoonists resonates with Americans and provide a vital component of the political dialogue that our democracy needs in order to thrive. While we acknowledge the financial challenges publishers face with the online market, eliminating original content is not the answer. We denounce the actions of Hearst Communications in their short-sighted cost cuts at the expense of the health of the editorial cartoonist profession and journalism in general." The statement was signed by AAEC President, Ann Telnaes; President-Elect, Pat Bagley; Vice President, Nate Beeler; Secretary-Treasurer, Monte Wolverton; and Immediate Past President, Adam Zyglis and Board Members 2016-2018: Edd Hall, Keven Siers, and Signe Wilkinson (a list that includes several Pulitzer winners.)

SALES OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS STILL GROWING By Calvin Reid, publishersweekly.com Combined graphic novel and comics sales in North America grew 5% to $1.085 billion in 2016, a $55 million increase over the $1.03 billion reported last year, according to a joint estimate by industry news sites Comichron and ICv2.com Led by the continuing sales growth of book-format graphic novels (which rose to $590 million, from $350 million in 2015), the $1.085 billion figure represents the combined sales of book-format graphic novels, traditional comics periodicals ($405 million), and digital download-to-own comics ($90 million). Physical sales of graphic novels sold through the book trade rose 16%, to $405 million. While total sales of both comics and books through the comics shop channel were about $570 million, the increase was driven by periodical sales. Sales of graphic novels in the comics shop market were flat in 2016, according to the joint report. Milton Griepp, CEO of pop culture new site ICv2.com, cited the ongoing growth of graphic novels as key to the increase: "This represents growth in the broadest part of the market, where increased variety of content is being found by new audiences for comics, including kids and women."

COMIC BOOKS NO LONGER A SECURITY THREAT The Transportation Security Administration has ended tests of a new requirement for passengers to remove books and other paper items (including comic books) from their carry-on luggage during security screening, reported Maren Williams at CBLDF. Rules demanding this sort of search may be instituted at a later date, but, said an agency spokeswoman, “at this time, [we] are no longer testing or instituting these procedures.” The TSA says that the pilot test simply ran its course, but the announcement came shortly after alarm bells started ringing among intellectual freedom and privacy advocates in the past week—particularly at the San Diego International Airport to which thousands of comics fans were flocking with their bags loaded with comic books purchased during the San Diego Comic-Con. Turns out to have been a misreading of some obscure directive somewhere. Separately in a public-facing blog post, the agency said that pilot tests had been conducted and subsequently ended at only two airports. It then made some curious attempts at humor in dismissing privacy concerns (in italics): [O]ur adversaries seem to know every trick in the book when it comes to concealing dangerous items, and books have been used in the past to conceal prohibited items. We weren’t judging your books by their covers, just making sure nothing dangerous was inside. In any case, the TSA says that as of today there is no systematic requirement for books to be scanned separately in any U.S. airport, nor does it currently have plans to implement any such procedure. And where’s the funny part? I guess you had to be there.

TRUMP QUOTES TO BE USED IN NEW SUPERHERO FUNNYBOOK The Unquotable Trump comic book, due for November publication, was briefly displayed at the San Diego Comic-Con a couple weeks ago by its creator, Robert Sikoryak, who has made a reputation for himself doing comic book mockeries of famous literary and/or actual personages. “He’ll take a famous novel, such as Crime and Punishment, and draw it in the style of Batman artist Bob Kane,” reported Peter Larson at ocregister.com. “The resulting mash-up was Dostoyevsky Comics.” Now

he’s given Trump the treatment in a comic book of comic book covers. For it,

Sikoryak pulled actual quotes from Prez Trump on the campaign trail and in

office, using them to create parodies done in the style of vintage comic book

covers. On one the cover of which looks like a Wonder Woman comic book, below the Nasty Woman logo, Wonder Woman is shown knocking Trump off the top of a wall, and as he tumbles head over heels, he utters his famous utterance about nasty woman, his cell phone flying. The Trump quotes are sourced at the back of the book. “I usually work with found text,” said Sikoryak, “—and I’d been confounded and outraged by everything he’d said during the campaign. I used only things he said out loud. None of his tweets.” Has he considered send a copy to the White House? asked Larson. Said Sikoryak: “I guess we should send one to Sean Hannity—that way Trump might see it.”

THE ACTUAL RESULTS OF IMPLEMENTING THE CONSERVATIVE AGENDA From The Week “The nation’s most aggressive experiment in conservative economic policy is dead,” said Russell Berman at TheAtlantic.com. In 2012, Kansas Governor Sam Brownback put the theory of supply-side economics into action, making sharp reductions in the state’s income tax rates and virtually elminiating taxes on small businesses. Like all supply-siders, he was convinced deep tax cuts would accelerate economic growth so much that they would pay for themselves. But that didn’t happen. Growth rates in Kansas have lagged way behind national levels, the budget has a $900 million two-year shortfall, and education spending was cut so badly that parents rebelled and the state Supreme Court ordered funding restored. The state’s Republican lawmakers finally rebelled and overcame Brownback’s veto to raise taxes by $1.2 billion. Supply-side economics “never works,” said Eugene Robinson in the Washington Post. Before this debacle, Republicons “could at least argue” that their theory had never been fully tested. Now “that excuse is gone.” Excuse-makers, however, presisted. As they always do. Here we go again, said Pat Garofalo in USNews.com. Conservatives always try to explain away supply-side failures by saying the reforms weren’t quite right [or the timing was wrong or...]. “No amount of evidence is enough to shake the belief that America is just one good rate reduction away from an economic renaissance.” The big question is whether national Republicons will heed the lessons of Kansas, said Jordan Weissmann in Slate.com. Prez Trump is being advised by the same economists who engineered Brownback’s disastrous scheme, and he has proposed a similar program of massive income tax cuts and pass-through exceptions for businesses. “Kansas has admitted its mistake”—but Republicons “may try to repeat it anyway.”

TINA LOSES HER GROOVE Rina Piccolo’s syndicated comic strip, Tina’s Groove, ended a 15-year run on July 2. Debuting on March 4, 2002, the strip struck a blow for single women. It chronicled “the personal and workplace adventures of a single, smart, attractive waitress who worked at Pepper’s Fine Dining restaurant,” said King Features at its website. “Shrewdly self-aware, Tina refuted cliched notions of single women as neurotics obsessed with career or marriage. Tina found her groove and empowered herself by embracing life and everyone she met head-on. She’s happy being Tina, living life rather than waiting for it to begin. She is described as ‘smart, funny and real,’ an everywoman in her 30s who ‘struggles to deal with her job, dating and the ups and downs of day-to-day living.’" In contrast, Suzanne, Tina’s best friend and a fellow waitress, “is always looking for a good time and enjoys casual relationships with a large number of men.” Said Piccolo of Trina and Suzanne: “Tina’s imperfections, if she has any, are of the kind that are quirky, and therefore endearing. This is good for a cartoon character. I believe the main character of a comic strip should be one that’s likable. But does that mean the main character should be flawless? It’s the weaknesses, or fixations, that make characters interesting. The other characters of the strip all have fixations that make them imperfect. The chef Carlos, known for his ego and his outdated views on gender and romance, is a sack of testosterone who must prove himself to be the manliest at any cost. Suzanne is a spoiled 30-something flake who has so many weaknesses she’s created a personality out of being less than perfect.” Tina has a boyfriend, Gus, whom she met in 2012; but she displays no eagerness to join the ranks of marital bliss. She’s just self-sufficient unto herself. But Piccolo, although abandoning Tina, hasn’t given up syndicated strip cartooning. In an online blog post, Piccolo laid out how it came together: "Every now and then, it happens. You reach a point in your career at which big decisions need to be made, a sort of crossroads, I guess you’d call it. This point came to me about two years ago. At the time, I was in my 13th year of Tina’s Groove. I was working on other things as well: completing my co-authored book Quirky Quarks, drawing cartoons for my Wednesday slot of the single panel daily Six Chix, and also, I was writing some gag ideas for Hilary Price, for her comic strip Rhymes With Orange (while occasionally filling in for her as a Guest Cartoonist). “It was around this time that Hilary approached me with an idea of her own. That idea — a tiny pebble that took 24 months to develop into a boulder— changed my life. Basically, Hilary asked if I would join her in drawing and writing Rhymes With Orange. And I said yes." The week of July 3 marked the official launch of that collaboration. In 15 years, Piccolo wrote, she produced more than 5,700 Tina’s Groove strips. For 16 years, she also has contributed a regular daily installment to the unique strip, Six Chix, through which six women cartoonists rotate, each doing one strip a week. Piccolo withdrew from that arrangement last year.

TRINA’S GROOVE LEAVES THE DAILY FUNNY PAGES of the nation’s newspapers with a quirky flourish. Piccolo teased her readers: “Have I failed in giving enough hints? Maybe you suspected that something was up, but then maybe you didn’t ... until today,” she added on July 2. “To all of you who have said goodbye to Tina, whether on social media or to me directly, I just want to say that I very much appreciate your kind words and warm wishes, and am sending virtual hugs to each and every one of you,” Piccolo wrote. “For those of you who have not been so kind towards my decision to end Tina’s Groove, well, what would you like me to tell you? I’m sorry that I’ve made a career change that doesn’t sit well with you. In my next life I will try to make decisions catered more to your liking. (Sheesh.)” For the last several weeks, Tina’s Groove has been an unusual strip. Piccolo explained: “With the knowledge that these were to be my last months of writing and drawing the strip, I went a little crazy toying with it, and decided to break some walls and have some fun with themes that would’ve been out of place if I’d done them before.” We’ve posted a selection of these odd-ball dailies next down the scroll. I enjoyed Tina’s Groove, but I enjoyed Piccolo’s earlier work better. When I first met her at the San Diego Comic-Con years ago—before Tina’s Groove—she was selling a little booklet of cartoons at a table in the small press area. The cartoons were sharply witty and off-the-wall. Tina’s Groove, in contrast, was wholly conventional however pioneering its approach to working single women was. I always thought that syndication had blunted the cutting edge of Piccolo’s sense of humor—as if she had to hold something back in order to appear in a daily newspaper. Hilary Price often ventures into areas Tina never wandered—and the times are more permissive now for off-beat comedy. I’m looking forward to seeing that early side of Piccolo in Rhymes with Orange. And now, a selection of the strips of Tina’s farewell bow. And several of Piccolo’s first week on Rhymes. Then we’ve posted samples of Piccolo’s outrageously funny iconoclastic single-panel cartoons from three pre-syndication collections: Stand Back, I think I’m Gonna Laugh (1994), Kicking the Habit: Cartoons about the Catholic Church (1996), and Rina’s Big Book of Sex Cartoons (1997).

IN THESE UNITED STATISTICALS ◆ Ten times more people work in clean energy in California than mine coal in the entire country reports the New Republic (August/September 2017). So by reviving the coal industry, the Trumpet effectively ignores the direction that the development of clean energy growth is taking us. ◆ Since January, nine states have passed major new voter restrictions that will hit minorities and students hardest; again, the aforementioned issue of the New Republic. ◆ In a survey of Americans in small towns and rural areas, 68% of respondents say that their values are different from those of people in urban areas; 56% of rural Americans believe that the federal governments aids people in cities more than them, and 78% of rural Repbulicans said Christian values are under attack (Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation). Most of these folks are likely consumers of Fox News. (Sorry: that’s just moi—RCH.)

ODDS & ADDENDA The August 4th issue of Entertainment Weakly carried its post Sandy Eggo report: nine (9, count ’em) pages about movie stars; nowhere in this so-called “coverage” were “cartoonist” or “comics” mentioned, except the latter in the singular form of “Comic-Con.” ... Images of Winnie the Pooh have been blocked on social media sites in China because bloggers are jokingly comparing the plump bear to China’s president. ... The Society of Illustrators clubhouse at 128 East 63rd Street in New York has mounted the first ever exhibition of original Spider-Man artwork by John Romita and other significant artists including Steve Ditko, Todd McFarlane, John Buscema, Ross Andru, Gil Kane, Ron Frenz, Keith Pollard, John Romita Jr. and others. The exhibit runs from June 6th through August 26th, 2017.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO “He has so many questions that trying to follow his thoughts is like trying to follow a bag of spilled marbles.”—Time profile of Michael Keaton Woody Harrelson has led a life that is often full of trouble—mostly of his own making. But he doesn’t have many regrets: “It’s like my buddy says, ‘If you’re not living on the edge, you’re taking up too much room.’”

WORD POWER Annual List of Banned Forever Words The wordsmiths at Lake Superior State University have taken their best "guesstimate," and early in 2017, they released LSSU's 42nd annual List of Words Banished from the Queen's English for Mis-use, Over-use and General Uselessness. As a user of words myself, I find the ensuing report fascinating—and highly amusing. Skip this if you’d rather look at pictures (which is usually my choice, but, in this case ...). "Overused words and phrases are a 'bête noire' for thousands of users of the 'manicured' Queen's English," said an LSSU spokesperson, who released the 'historic' list during a town hall meeting. "We hope our modest 'listicle' will figure 'bigly' in most 'echo chambers' around the world." LSSU's word banishment tradition is now in its fifth decade, according to the University’s press release [which is responsible for all of this verbiage]. Through the years, LSSU has received tens of thousands of nominations for the list, which now includes more than 850 entries. This year's list is culled from nominations received mostly through the university's website. Word-watchers target pet peeves from everyday speech, as well as from the news, fields of education, technology, advertising, politics and more. A committee makes a final cut in late December. Compilers hope this year's list is "on fleek." Herewith, the 2017 list: You, Sir - Hails from a more civilized era when duels were the likely outcome of disagreements. Today, we suffer on-line trolls and Internet shaming. Focus - Good word, but overused when concentrate or look at would work fine. See 1983's banishment of, We Must Focus Our Attention. Bête Noire - After consulting a listing of synonyms, we gather this to be a bugbear, pet peeve, bug-boo, pain, or pest to our nominators. Town Hall Meeting - Candidates seldom debate in town halls anymore. Needs to be shown the door along with "soccer mom(s)" and "Joe Sixpack" (banned in 1997). Post-Truth - To paraphrase the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, we are entitled to our own opinions but not to our own facts. Guesstimate - When guess and estimate are never enough. 831 - A texting encryption of, I love you: 8 letters, 3 words, 1 meaning. Never encrypt or abbreviate one's love. Historic - Thrown around far too much. What's considered as such is best left to historians rather than the contemporary media. Manicured - As in a manicured lawn. Golf greens are the closest grass comes to being manicured. Echo Chamber - Lather, rinse, and repeat. After a while, everything sounds the same. On Fleek - Anything that is on-point, perfectly executed, or looking good. Needs to return to its genesis: perfectly groomed eyebrows. Bigly - Did the candidate say "big league" or utter this 19th-Century word that means, in a swelling blustering manner? Who cares? Kick it out of the echo chamber! Ghost - To abruptly end communication, especially on social media. Is it rejection angst, or is this word really as overused as word-banishment nominators contend? Either way, our committee feels the pain. Dadbod - The flabby opposite of a chiseled-body male ideal. Should not empower dads to pursue a sedentary lifestyle. Listicle - Numbered or bulleted list created primarily to generate views on the Web, LSSU's word-banishment list excluded. "Get your dandruff up . . . " - The Committee is not sure why this malapropism got nominators' dander up in 2016. (I love this one.—RCH) Selfie Drone - In what could be an ominous development, the selfie— an irritating habit of constantly photographing and posting oneself to social media— is being handed off to a flying camera. How can this end badly? Frankenfruit - Another food group co-opted by "frankenfood." Not to be confused with other forms of genetically modified language. Disruption - Nominators are exhausted from 2016's disruption. When humanity looks back on zombie buzzwords, they will see disruption bumping into other overused synonyms for change.

THE BANNISHED WORD LIST BEGAN on New Year’s Day in 1976 when LSSU Public Relations Director W.T. (Bill) Rabe released the first one. The international reaction was so enthusiastic that Rabe was sure the annual listing “would go on forever." So it seems. People from around the world have nominated hundreds of words and phrases such as "you know," "user friendly," "at this point in time," and "have a nice day," to be purged from the language. The tongue-in-cheek Banishment List began as a publicity ploy for little-known LSSU. In 1971, Rabe realized that Lake State was still largely thought of as a branch of Michigan Technological University, if it was known at all. To combat this image, he established the mythical Unicorn Hunters, along with events such as the annual Snowman Burning to welcome the first day of spring and, in 1976, the nefarious list of words. In order to gain the most media coverage possible, the Banishment List is released each year on New Year's Day. This is attributed to former newsman Rabe's knowledge of the press. New Year's Day is traditionally a slow news day so newspapers and tv news and the lot will publish almost anything to fill columns and air time. The first list was dreamed up by Rabe and a group of friends at a New Year's Eve party in 1975. Though he and his friends created the first list from their own pet peeves about language, Rabe said he knew from the volume of mail he received in the weeks after posting the first list that the group would have no shortage of words and phrases from which to choose for 1977. Since then, the list has consisted entirely of nominations received from around the world throughout the year. After Rabe retired in 1987, the University copyrighted the concept and continued the tradition. For the sake of one more footnote— LSSU’s burning of a massive paper snowman at high noon on the first day of Spring is a ceremony that welcomes the seasonal change. Members of the student government barbecue hot dogs and serve them to the students and guests as part of the celebration. The first spring snowman burning was held in March 1971 by the Unicorn Hunters, a former campus club that is another of Rabe’s inventions. Traditionally it has been held on the first day of spring to bid good-bye to winter and welcome spring. LSSU's snowman has taken on many shapes over the years. During the 1970s, when women's liberation was a news issue, a "snow person" was burned. In the 1980s, when clones and "cloning" were first in the news, a "snow clone" was torched. The Unicorn Hunters also burned a Snow Ayatollah Khomeni during the Iran hostage crisis. In the late 1980s, the snowmen began to take the form of a Lake State rival hockey team, usually whichever team the Lakers were playing that weekend. This was dropped after a few years when many complained that it brought bad luck to the team. Snowmen are made out of wood, paper destined for the recycling bin, along with some straw, wire and some paint. They are usually husky and stand 10 to 12 feet tall.

TWUMP AND POOTY: THE STORY TO DATE

FAX & SMACKS ◆ Donald Trump is the first U.S. Prez without a pet since Andrew Jackson, who left office in 1869, reports The Economist. Well, that figures: how could our most narcissistic Prez have any room left in his yuuuge self-regard for affection for anything outside himself? ◆ The American Psychoanalytic Association has abandoned a long self-enforced custom. It has informed its members that they are now free to publicly offer their opinions on the mental health of the Trumpet, “since Trump’s behavior is so different fro anything we’ve ever seen.” ◆ The only arguably major legislation passed by Congress on the Trumpet’s watch was when Congress agreed to a $1 trillion spending package in early May, but the package did not include most of the Trumpet’s policy initiatives, reported The Week (May 12; I’m a little late with this, but I’ve been saving it up). The only loser was Trump.

PULITZER WINNER REFLECTS ON HIS CARTOONING CAREER By Jim Kanak at seacoastline.com For most

journalists, winning a Pulitzer Prize is a crowning lifetime achievement.

Ogunquit resident Jim Morin, editorial cartoonist at the Miami Herald since 1978, reached that goal in 1996, winning his first Pulitzer. Then, in

April of this year, he won his second, based on a juried review of a portfolio

of 20 cartoons he selected and submitted from his work in 2016. (See Opus 365.) “This one was really unexpected,” Morin said in an interview at his home. “Coming at the end of a career, it’s really rewarding, an acknowledgment that you’re still doing good work.” Morin began his political cartooning in his days at Syracuse University working on the student newspaper. “I went to art school at Syracuse,” Morin said. “I took figure drawing and painting classes. I loved cartooning, but saw that you needed an art background to pull it off.” Morin’s interest in politics blossomed during the Watergate scandal that resulted in President Richard Nixon’s resignation from office in 1974. Morin was in London as the scandal unfolded and noted that the British people he met all expressed interest in what was happening in the United States. When he returned to the states, Morin said he attended some of the trials “to get a real look at what was going on.” He decided to see if the student newspaper had any interest in his doing editorial cartoons. “My mom was really nervous about my making a living with an art degree,” Morin said. “She said ‘why don’t you do what (political cartoonist) Herblock does?’ I looked at some of it and started to do it. When I returned to Syracuse, I was going to ask if I could draw political cartoons for the student paper, but before I could, the editor asked if I wanted to. I started at two a week and ended up at five. That was a stroke of luck. I learned how to cartoon by looking at other cartoonists. Duncan McPherson of the Toronto Star was an amazing artist. I never stopped and still look at other people.” Morin’s interest in cartooning and art began early in his youth, and was influenced by an acquaintance with iconic cartoonist Al Capp. “I came from a political family,” said Morin. “My dad was involved in the Republican Party in Massachusetts. The Republicans wanted someone to run against (Democratic Senator) Ted Kennedy, and they came up with Al Capp. My dad was his campaign manager. It didn’t last long. Capp went down to register (as a candidate) and he was a day late.” Despite the campaign ending prematurely, Morin’s father had arranged for him to spend some time with Capp. “I went to his studio on Beacon Street and went to lunch at the Ritz Carlton,” Morin said. “He asked (what artists) I followed and I said Daumier, the French caricaturist. Capp said that’s a good one to be influenced by. I was into caricature at that point, and followed people like Edward Sorel, David Levine, and Ralph Steadman.”

ARMED WITH HIS PORTFOLIO from his days at Syracuse, Morin pursued a professional career in the early 1970s. He spent at year freelancing and then landed a job with a newspaper in Texas. He left after a story and cartoon about a local business caused the business to pull its advertising from the paper, resulting in the editor’s departure. “That was my first lesson in newspapering,” Morin remembered. He spent a brief time with the Richmond (Virginia) Times Dispatch, where he worked with editoonist Jeff McNelly, who also did the comic strip Shoe. Morin heard of an opening at the Miami Herald and was hired there in 1978, a position he’s maintained ever since. He and his wife, author Danielle Flood, moved to Ogunquit four years ago, and he’s been working from his office there since. “The Herald moved its offices from Biscayne Bay inland to a smaller building,” Morin said. “I decided to work from home. Myriam Marquez was the editor, a wonderful one. She said it was fine for me to work from home. I’ll never forget her for that.” Morin produces roughly 350 cartoons each year, dealing with national as well as statewide issues. “I like cartoons that have legs, that are understandable now and even years from now,” he said. “I don’t particularly like election years, dealing with personalities. I like dealing with issues that mean something.” At this point in his career, Morin said he’s winding down, looking to retire in 12 to 18 months. That doesn’t mean his days as an artist will end. He’s also been painting since he was young, primarily working in oils and, more recently, watercolors. “I’ve been doing it since I was a kid, but always in addition to something else,” Morin said. “I look forward to doing it in retirement. Watercolors are really a different thing. It will take me a number of years to get them where they’re good. It’s a challenge, like being young again.”

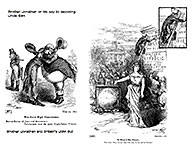

THE TANGLED TALE OF UNCLE SAM The history of the cartoon figure who represents the United States of America is, itself, a sort of symbolic encapsulation of cartooning: Uncle Sam evolved by blending the verbal and the visual like any good cartoon. First came the verbal, which emerged during the War of 1812. The story, though disputed, is that the term “Uncle Sam” referred, at first, to a businessman in Troy, New York, Samuel Wilson, who was affectionately known as “Uncle Sam” Wilson. He inspected beef and pork purchased for the government during the War. The barrels of meat were stamped “U.S.” to indicate government property. They were also stamped “E.A.,” the initials of the contractor, Elbert Anderson, who purchased provisions. His workmen understood what “E.A.” meant—the name of their boss— but wondered who “U.S.” was. Some wag supposedly supplied a facetious explanation: the initials stood for Uncle Sam, from whom Anderson bought the meat. “Uncle Sam” meaning the United States appeared in newspapers from 1813 to 1815; in 1816, he appeared in a book in that symbolic role. By the 1820s, “Uncle Sam” was often being used as a term for the United States. The Sam Wilson connection seems a little shaky to me, but Congress passed a resolution in 1961 that recognized “Uncle Sam” Wilson as the namesake of the national symbol. The visual representation of Uncle Sam, a tall man with a white goatee wearing a top hat, swallow-tail coat and striped trousers, evolved from pictures of an earlier symbolic figure—Brother Jonathan.

UNTIL THE CIVIL

WAR, goateed Brother Jonathan, in striped pants and top hat, often stood for

the United States even though the cartoon character initially represented just

New England. The term Brother Jonathan originated during the English Civil War

(1642-1651) between the Parliamentarians (“Roundheads”) and the Royalists

(“Cavaliers”) as a somewhat derogatory name for the Puritan Roundheads, and

then the name was also applied to the New England colonists, who were also

mostly Puritans who also supported the Parliamentarians in the mother country.

By this route, Brother Jonathan became a stock character that good naturedly

lampooned Yankee acquisitiveness and other crafty peculiarities attributed to

citizens of the region. A weekly newspaper called Brother Jonathan was first published in 1842 in New York, exposing the character to parts of the country outside New England. And in 1852, a humor magazine, Yankee Notions, or Whittlings of Jonathan’s Jack-Knife, gave the character additional visibility. According to St. Wikipedia, about this time, the New England-based Know Nothing Party, which Yankee Notions lampooned, was divided into two camps—the moderate Jonathans and the radical Sams. Eventually, over the course of the late 19th century, Uncle Sam displaced Brother Jonathan by assuming his customary garb— top hat, tails, striped pants plus goatee. According to an article in The Lutheran Witness of 1893, Brother Jonathan and Uncle Sam were two names for the same person. “When we meet him in politics, we call him Uncle Sam; when we meet him in society, we call him Brother Jonathan.” I suspect that such a fine distinction had a very short life—if, in fact, it survived anywhere outside the pages of The Lutheran Witness. At Harper’s Weekly through the 1870s, we can watch the evolution of Brother Jonathan into Uncle Sam under the pencil of Thomas Nast. In May 1871, the character, named Jonathan in his encounter with Britain’s John Bull, seems somewhat scruffier in appearance than in his Uncle Sam incarnation. By April 1876, Uncle Sam (dubbed “U.S.” by Nast) has acquired a rather dignified aspect, which he will retain thereafter.

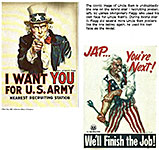

Some sources say that Yankee Doodle Dandy is somehow incorporated into Uncle Sam, but I don’t agree: Yankee Doodle Dandy appeared only in the lyrics to a song—no pictures— and neither Brother Jonathan nor Uncle Sam reflect any of his lyric personality. Brother Jonathan had long since disappeared by the dawn of the Twentieth Century, and when famed illustrator James Montgomery Flagg (using his own face as a model) painted Uncle Sam’s portrait for a recruiting poster during World War I, Uncle Sam was firmly established as a symbol for the United States. The Flagg interpretation and numerous other renderings of Uncle Sam conclude this foray into the patriotic past. All the pictures posted near here come from a collection of Uncle Sams owned by a Florida editorial cartoonist Bob Meagher (1913-1994). They were assembled and published in 1998 in America’s Favorite Uncle: Cartoonists Draw A Legacy (Calm Publications, Milton, Florida). If you keep an eye on the signatures as you browse this gallery, you’ll see some names famous in the history of cartooning—Zim, for instance, and editoonists Fred O. Seibel and Cecil Jensen, and the founder of the Landon Correspondence School of Cartooning not to mention the creator of Pogo. How many others do you know of?

MOTS & QUOTES So leaders in the Republicon Congress continue to support the Trumpet and tolerate his uncooth and ill-considered antics in the belief that, as Prez, he’ll sign into law whatever wild-eyed right-wing legislation they pass. Party loyalty. Right. Like Trump is reliable. He’s always done whatever the GOP expects him to do, right? And he always keeps his promises. Right. Are those guys all nuts? Well, yes. But we’ve known that for years, haven’t we?

THE STATE OF THE CARTOONING INDUSTRY The Internet is clearly one of the futures of cartooning. But since at present there are no gatekeepers (like feature syndicate cartoon editors), the quality of the work is iffy. Some excellent stuff is being done. Sinfest, a daily strip by Tatsuya Ishida, has been regaling us with its quirky humor since January 2000. And there are a few others. Mostly, however, web comics are pretty sad graphically speaking, and the humor evades me more often than not. (More my problem than theirs, no doubt.) Still, the web is a good place to train, and it’s lively in that apprentice function. Magazine cartooning has been fading ever since the collapse of the Saturday Evening Post as a weekly publication in 1963. Other great venues for gag cartooning—Collier’s, Look, Saturday Review, etc.—joined the SEP at about the same time, late 1950s–1960s. And when Playboy stopped publishing cartoons in March 2016, that left only The New Yorker as a major market for gag cartooning. Other markets exist (consult Gag Recap website to get a start at a list; also Google magazine markets for freelance cartoons), but the pay is so low I doubt anyone can make a living cartooning for magazines. The liveliest place for good cartooning these days is comic books. And it’s not just superhero antics by overwrought anatomies in tighty whities. All sorts of grim adventuring and light-hearted joking and wild fantasizing is going on, and new titles on different milieux pop up every month; some don’t last long, but other new endeavors quickly take their places. And the artwork is usually superior—take, f’instance, the exquisitely detailed and realistic rendering by Sean Phillips (colored masterfully by Elizabeth Breitweiser) in Ed Brubaker’s Kill or Be Killed, or any of the comic books reviewed below in Funnybook Fan Fare. The gratifying growth of the graphic novel has further stimulated the print medium in both art and story. As for the newspaper comic strip, its fate is tied to the fate of newspapers, and while the prospects at present don’t seem, offhand, very encouraging, the situation is better than it seems. I inveighed against the fake death of newspapers in Opus 318 (November 2013), so I won’t repeat myself here. But there are a couple more things I can add to that. First, new comic strips continue to be created. Not as many as in the fond days of yesteryear, but new strips signal that there is life left in the medium. Second, newspaper circulation, which has been declining alarmingly since the advent of the Web, is reviving and doing better than supposed. Oddly, the election of the Trumpet has resulted in a surge of newspaper subscriptions. In the week after the election, the New York Times netted 41,000 new subscribers, according to a Huffington Post report; in the two days after Election Day, the Times website got record traffic, and readers spent five times longer on the site than they normally did. The Wall Street Journal had similar experience: the day after Election Day, new subscribers spiked with a 300% increase. By the end of the month, the Times had 132,000 more subscriptions in its print and digital editions. And the Washington Post reported that it experienced a steady increase in subscriptions through 2016; ditto the Los Angeles Times. At the end of last year, the Washington Post expected to hire more than 60 journalists this year. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos bought the Post in October 2013 and invested $50 million in the company last year—an investment, it turns out, that’s paid off. At npr.com, Post’s publisher Fred Ryan said that the paper is now “a profitable and growing company.” He said the Post’s online traffic has increased by nearly 50 percent in 2016 and new subscriptions have grown by 75 percent, more than doubling digital subscription revenue. By the end of 2016, the New York Times had added 276,000 new paid digital subscriptions, and digital advertising revenue rose almost 11% to $77.6 million in 2016's last quarter. The phenomenon seems to be a direct result of the Trumpet’s casual regard for facts. People subscribe to newspapers in print and in the digital ether in order to find out what’s really going on—rather than believe, as an article of faith, whatever the Trumpet blurts. Termed “the Trump bump,” the increase has enabled the New York Times to pass the 3 million subscriptions threshold in the first three months of 2017. By the end of March, saith thestreet.com, the Times will have “added 500,000 new net subscribers over a six-month period, unprecedented in U.S. history.” The Washington Post is seeing “double digital subscription revenue in the last 12 months, with a 75% increase in new subscribers.” Other large regional papers report similar growth. And magazines are doing well, too. The New Yorker sold 250,000 new subscriptions between Election Day and the end of January 2017, “up 230% compared with the same three-month period a year ago. ... The magazine now has its largest circulation ever, at more than a million.”

THE REPORTED INCREASED READERSHIP at newspapers includes paid subscriptions both to the publications’ Internet editions and to the print versions. Clearly, the daily newspaper is not in its death throes just yet. And if newspapers are doing well, so will comic strips. Advertising revenue is still the chief financial support of newspapers. Subscriptions never produced enough revenue to do more than pay for printing. With the surge in subscriptions, newspapers become more viable as advertising vehicles: more people see the ads. But there’s more good news buried in this phenomenon. As subscriptions increase, newspapers become more dependent upon subscriptions—that is, readers. Advertising is still important, but readership assumes a new importance, and with that, newspapers must necessarily pay attention to what readers want. And readers want comic strips. Readership surveys consistently show that comics rank among the top four newspaper ingredients in popularity—front page, sports, obits and/or comics. So if newspapers wish to maintain and/or increase subscriptions/readers, they’ll attend to the things readers enjoy most. Comics. This line of reasoning is fraught with fallacious so-called logic, no doubt; but I like the conclusion, so I’m sticking with it. Newspapers know the value of the comics to their bottom lines. They’ve always known. And that knowledge has not faded. Recently, my hometown paper, the Denver Post, provided a vivid demonstration of this prevailing wisdom. To witness it, revisit Newspaper Comics Page Vigil in Opus 367.

THE STATE OF SATIRICAL COMEDY Notes from Emily Nussbaum at The New Yorker In theory, the current political moment provides a brilliant opportunity for zingers. In practice, we’re living through a glut, in which no joke feels original and few feel sufficient. ... Under an absurdist regime, intensified by the digital landscape ... all jokes become “takes,” their punch lines interchangeable with CNN headlines, Breitbart clickbait, Facebook memes, and Trump’s own drive-by tweets, which themselves crib gags from “Saturday Night Live.” (“Not!”)

At The New Yorker SURREAL TRUMPS REAL The New Yorker established the single-speaker captioned panel cartoon as better for provoking laughter than the multiple-speaker captioned cartoon that prevailed for decades through the 19th Century and until the late 1920s. In the single-speaker cartoon, the caption “explains” the picture and vice versa: with the explanation comes understanding and surprise—both of which cause laughter. But The New Yorker did more than establish the form for magazine cartoon comedy. The magazine’s cartoons usually made fun of the pseudo sophisticate of its urban environment. But in a very low-key way. “With The New Yorker,” Russell Baker wrote, “American humor began to master the arts of understatement, to refine the crudities of old-fashioned burlesque into satire, to treasure subtlety and wit.” As

the new cartoon editor of the magazine, Emma Allen, 29, has become a

steward of this tradition. “I don’t feel beholden to finding the next Benchley or a Benchley knockoff,” she said. “I like things that are witty. I also like dumb fart jokes. The high-low spread is much more interesting than trying to mummify a thing and keep presenting it all over and over again.” Allen has “a sprawling set of responsibilities,” Zinoman said. “She also edits the daily cartoons for The New Yorker online; works on video and radio humor pieces for the magazine; runs its humor Twitter account; and for three years has edited Daily Shouts, comic essays that have become one of the most popular features on the site. (According to the magazine, in the past three months, traffic to those essays is up 60 percent from last year.) “Her ability to find new voices for Daily Shouts is what first drew the attention of The New Yorker’s editor, David Remnick. ‘She was bringing in people and things that I hadn’t heard before, and sometimes you need to reinvigorate parts of the magazine,’ he said by phone, adding, ‘We need to have a deeper exploration of the web, as far as cartooning.’”

ALLEN, WHO GREW UP ON THE UPPER WEST SIDE, has in some ways been preparing for this job her whole life. As a child, she cut out The New Yorker cartoons and filed them with “an archival drive” matched only, she said, by her collection of photos of Leonardo DiCaprio. She attended Brearley School in Manhattan, where, she joked, her comic career was born. “For 13 years, I went to an all-girls school whose mascot is the beaver,” she said. “You cannot come out at the other end of that without a sense of humor.” After graduating from Yale — “where her humor column masqueraded as an advice column for the school newspaper” — she worked in media, often covering the art world. She wrote a funny feature for The New York Observer recapping the reality show “Work of Art,” and started at The New Yorker as an assistant to the articles editor Susan Morrison (who is currently working on a book about Lorne Michaels), occasionally writing, then editing Talk of the Town pieces. Finding new voices for cartoons is challenging, because there are so few outlets publishing one-panel cartoons, but also because readers and artists have come to expect something very specific from The New Yorker cartoon, “the gently observed comedy-of-manners-style that ‘Seinfeld’ lampooned in an episode in which Elaine confronts an editor who can’t explain the joke of a cartoon.” Asked how her taste in comedy differs from that of her predecessor, Bob Mankoff, Allen said: “I think I have a slightly weirder sense of humor,” adding later, “As much as I like observational gags, I also like things that are more surreal.” Allen said that she hoped to expand the kinds of cartooning online, including trying more work with multiple panels and pairing joke writers with cartoonists on some projects. She has “catholic taste,” she says, but she also has pet peeves. “I do think there’s a type of regressive — that old nagging wife — sitcom humor that persists somehow,” she said, adding that they have a shorthand in the cartoon department when they see a joke like that. “I’ve never really watched ‘Everybody Loves Raymond’ but whenever there’s a joke about a nagging wife or whatever, we’re like, “Raymond!” Then she added: “And I like Ray Romano.” I’ve noticed in the last couple issues of The New Yorker that the number of cartoons in the magazine is slightly—ever so slightly—more than previously. The July 3 issue has 14 cartoons, close to what I suppose is the maximum—something like 15-17. A third of them, I’d say are “surreal”: their comedy has nothing to do with the outside, real, world. And the remainder, the reality-based cartoons, connect to reality only vaguely, tangentially: the caption employs a current catch phrase but makes of it something much less overtly satirical than the New Yorker cartoon of yesteryear. I’m posting 8 of them here, at the elbow of your eye.

The first exhibit displays what I call the “Allen surreality” cartoons; the second page, a few of her selections that are a little more connected to our world. The third-page exhibit consists of New Yorker cartoons from the magazine’s early years when it was making its reputation by satirizing prevailing attitudes among New Yorkers. Most of the captions refer to some contemporary expression or situation. The cartoons in magazine for July 31 totaled 19. Of those only 5 involved the customary sensibility; 14 were of the new weird Emma Allen sort. And the following issue (August 7) had 17 cartoons, including a delicious antique by George Booth. Again, most of the cartoons reflect the new surreal comedic ambiance. Although I fear that the new emphasis on “surreal weirdness” will undermine The New Yorker’s historic role as a commentator on our culture’s self-absorption, I applaud the increase in the number of cartoons being published in each issue. And if that signals Allen’s influence, I’ll stand as I applaud.

A NEW YORKER’S VIEW OF A FORMER NEW YORKER (Well, a Queens native) Not all New Yorker cartoonists work exclusively in pages of the print The New Yorker. Tom Toro is a Bay Area-born cartoonist who’s worked for The New Yorker since 2010. It took him 609 submissions over three years to finally break into the famously selective magazine; his first sale appears in a display down the scroll. Just about the time the Trumpet was inaugurated, Toro took a stint at The New Yorker’s online Daily Cartoon, and he was so upset with the Trump triumph that most of his cartoons zero’d in on New York/Queens’ most famous yellow-coiffed blowhard. Said Toro: “While I was on the ground [for the inaugural] in Washington, soaking up the funereal atmosphere, The New Yorker posted my Trump cartoons on social media and they went viral. I was caught off-guard by how ravenous people were for political satire, especially at that terrible moment with Trump actually taking the oath of office. It was sobering but also invigorating. I’d been given a mission. I could use the Daily Cartoon to hit back at Trump’s reign of terror. And he certainly never failed to provide ample comedic fodder. Danny Shanahan [another New Yorker cartoonist] is right — drawing Trump is like working with a gag writer. But a gag writer who comes up with wildly inappropriate material, so your entire job is to take what’s heinous and to make it hilarious. I think I speak for all political satirists when I say that we’ll be glad when our awful coworker is finally fired.” “It’s no easy feat,” observed Priscilla Frank at HuffingtonPost.com, “translating Trump’s ridiculous moments into even more absurd scenarios and getting people to laugh at circumstances that can feel, in actuality, quite dismal”—if not genuinely menacing. Frank marveled at the Trumpet’s first address to Congress, surreal for “Americans still struggling to come to terms with his exclusionary policies. Perhaps even stranger was the shift in tone that Trump delivered, devoid of the exaggerations, insults and non-sequiturs that often comprise his speeches. Pundits soon responded, praising Trump’s ‘presidential’ tone and calling the address Trump’s ‘most effective speech yet.’ “Yet many were alarmed by Trump’s subdued and civil demeanor, which made his false and misleading statements ― especially those meant to rouse fears about out-of-control immigrant crime ― seem all the more credible.” All those feelings and fears, Frank opined, Toro had crammed into a single, black-and-white cartoon —“a succinct and totally gutting image,” said Frank—that appears at the upper left in the first accompanying visual aid.

Frank reached out to Toro to learn more about the story this cartoon, along with the challenges of making jokes at the expense of our new Prez. Asked about his initial reaction to the Trumpet’s now famed “presidential” first speech to Congress, Toro said: “My initial reaction was disgust. Disgust paired with a deep sadness almost like mourning. I felt woozy from woe. Which is probably a common condition that progressives, or anyone who’s awake to the reality of our political situation, must cope with constantly nowadays. Donald Trump is president of the United States. That unbelievable calamity hit home as I watched him stroll down the aisle like a gloating groom toward I, the viewer, and viewers all across the world, as we wait like unwilling partners at the podium-slash-altar. “I felt personally threatened but helpless, trapped, transfixed, and my despair gradually gave way to anger. Here we have a charlatan, a pathological liar, a confessed sexual predator, a hatemonger, a racist ― let’s not mince words — professing to speak on our behalf in an endless stream of hollow platitudes, and doing so with that phony, wincing gravitas that Trump uses to try to conceal his desperate ignorance. Yes, I was disgusted.” Said Frank: “How do you go about finding the right balance of humor and gravity in your work?” “It can be difficult because Trump, as a subject of satire, has flipped the usual equation on its head. Instead of revealing the absurdity in what a politician has the gall to present to us as serious, we must now expose the seriousness of a politician’s galling absurdity. It’s bizarre. “Trump is actually, literally, a clown,” Toro continued, “—no disrespect to clowns. He’s a buffoonish showman who traffics in wild fantasies. Some of this might be intentional, for the purpose of distracting the media and hiding his nefarious deregulation schemes, but I tend to believe it’s an outgrowth of his genuine stupidity. Trump is a 70-year-old adolescent who’s virtually illiterate and has now suddenly been tossed into most high-stress job in the world where he must act like he’s in total control. Of course it’s ridiculous. It’s raw comedy ― it’s the very plot of Charlie Chaplin’s ‘The Great Dictator.’ “So what can a humorist do when reality itself mimics satire?” Toro asked rhetorically. “Or almost puts satire to shame? Especially when the culprits are acting with such brazen hypocrisy ― thus plucking another arrow from the comedian’s quiver, who’s job it normally is to skewer hypocrites? It’s an unprecedented challenge. In my own work, I aim to bring the facts to bear on Trump’s behavior, on his policies and statements, to hopefully highlight their gross divergence from anything resembling normalcy, and to make it amusing for readers by condensing the whole idea into a single frame, a single moment, a spark. Friction is funny. Cartoons are best when combustive.” Frank: “Do you feel a social responsibility as a cartoonist living in the era of Trump?” Said Toro: “I think all of us have a social responsibility to resist Trump’s destructive agenda in every way we can. Artists and comedians might get a lot of attention because we have a ready-made platform to express our views, but the creativity and humor of the spontaneous protests happening all across our country are far more powerful. It’s been so inspiring to see the witty, withering signs that people draw up, the eviscerating Twitter quips that get circulated, the imaginative forms of resistance people use to block the Republican bulldozer. I’m just trying to do my small part. “Humor is empowering because it’s connective,” Toro went on. “It’s associative. It binds together disparate ideas and thereby fashions new ones. It multiplies possibilities. While at the same time, by that same token, it undermines the opposition’s attempts to divide and isolate us. There’s a reason why Donald Trump is a singularly joyless and mean-spirited troll, why he has bald antipathy for the First Amendment, why he’s more thin-skinned than a molting serpent and he can’t take even a mildly critical jest: because humor is lethal to tyrants. “Humor is the heartbeat of a healthy democracy. And, well, as we’re soon going to show our so-called president, the joke’s on him.”

IN FACT, the joke is him, I’d say. And Emily Nussbaum seemingly agrees in her recent New Yorker article (July 31). She remembers that the Trumpet came to fame in a reality tv show. “If ‘The Apprentice’ didn’t get Trump elected, it is surely what made him electable. Over 14 seasons [fourteen years of Trump in your livingroom!], the tv producer Mark Burnett helped turn ‘the Donald’ of the late 1990s—the disgraced [and bankrupt four times] huckster who had trashed Atlantic City; a tabloid pariah to whom no bank would lend—into a titan of industry, nationally admired for being, in his own words, ‘the highest-quality brand.’” Before that, the Trumpet was “the Donald,” that blowhard arrogant New York rich guy playboy, luxuriating in headlines quoting beautiful women certifying his sexual prowess. Red tie, yellow hair, “less an icon than he is a retro cartoon.” And now he’s in the White House, an even bigger fake.

TOM TORO displayed his considerable wit a few weeks ago in an Ink Spill Interview conducted by another New Yorker cartoonist, Michael Maslin; excerpts follow—: It took Toro 609 submissions over a three-year period to finally gain acceptance and sell a cartoon to the magazine. “Since I was a newbie,” Toro elaborated, “—and I had no publishing track record up to that point—I drew finished cartoons, not just pitches. Painted, touched-up, the whole shebang. My style is fairly intricate, dare I say artful, so it took an incredible amount of time and energy. When I reflect on how difficult those years were and how hopeless it felt at times, I have to close my eyes and think of something more pleasant like dying of thirst. I only know that it took 609 tries because I save scans of every cartoon organized and dated on a hard drive. Immediately after landing my first sale I went back and tallied all the rejects. Maybe it was masochism. Or maybe it was a roundabout way of acknowledging those failed ideas that had brought me to this moment of triumph, and to say thank you, losers. “It’s an endless struggle,” he continued. “You grow so accustomed to failure as an artist that it can become difficult to appreciate the successes. I find myself distrustful of boom times. Because, on balance, rejection is the rule and acceptance is the exception. Hey, I’ve got a business proposal for you: it’s an amazing new product that only works 1% of the time. Care to make an investment? That’s basically what being a cartoonist means; you almost never hit the mark and you only get rewarded for an insanely small fraction of the work you do. No wonder we take victory with a grain of salt. There’s a quote from Samuel Beckett, who, by the way, won the Nobel Prize in Literature: ‘I’ve experienced success and failure in my career, and I’ve always felt more at home in the latter.’ (Paraphrasing.) I’m not as addicted to misery as Beckett, or as brilliant at mining it for gems, but I do share his sentiment. “My decision to pursue cartooning for The New Yorker is very much tied up with my process of coping with depression. I had just dropped out of NYU Graduate Film School, which I’d gotten into straight out of Yale, and then suddenly, after suffering a nervous breakdown and attempting suicide, I found myself back at home without a single ounce of self-esteem. Slowly rebuilding myself from the ground up, both as a person and as an artist, became inextricably tied with finding my voice as a cartoonist. It might sound crazy to say this, knowing what I know now, but cartooning seemed modest. It seemed achievable. What can I draw on this 8.5x11-inch piece of paper that communicates something in an amusing way? “I was also trying to excavate my sense of humor, which had been buried under an avalanche of self-doubt. Luckily I didn’t come to the task totally unprepared. I’d drawn comics as a kid. For a while I’d even toyed with the idea of being a Disney animator. In college I’d contributed cartoons to the weekly paper. There was precedent. But The New Yorker hadn’t entered my peripheral vision until I landed back at home. The magazine was never part of our family culture. We were very poor for a long time and most of the literature in our household came from what my dad would forage at the local recycling center. But then I encountered an issue of The New Yorker in the waiting room of my therapist’s office, appropriately enough, and seeing the cartoons was a real eye-opener. In that context they were special, noble, smart. And very, very funny. I wanted to be a part of that world.” Maslin brought up Toro’s forthcoming memoir: Yes, The Planet Got Destroyed (Or: How I Learned to Cartoon Through Catastrophe), due out from Dock Street Press in 2018. Said Toro: “It deals with my struggle to break into The New Yorker while battling suicidal depression. I tried to kill myself back in 2007, at what was obviously a very low point in my mid-twenties, but the attempt failed and instead I found myself living back at home, in the same house where I grew up, totally clueless about what to do next. So like any reasonable person in those circumstances, I started cartooning. My publisher tells me that for all the juicy details you’ll need to buy the book. But my point is, I’m manic-depressive. I go on productive sprees but then I have trouble enjoying the fruits of my labor. Is this a good year? Sure. Am I happy? Hell no. “We’re all flagellants to a certain degree,” he went on. “I think the rejection and suffering is a perversely attractive part of the job. If anything, it forges a community of survivors. We’re all pushing that boulder up the hill together, shoulder to shoulder, over and over and over again. Which is why I think it’s important that The New Yorker maintain the most rigorous, virtually unattainable standards of quality. The title ‘New Yorker cartoonist’ only means something if the cartoons are the absolute best. However, it’s also necessary for the contributing artists to get cut a little slack now and then. You simply can’t restart your career at Square One every single week. It’s unsustainable. Once you’re in, you’re in. You’ve proven yourself. You won’t get lost in the mix of thousands of new submissions that pour into the department. I will say this: doing the Daily Cartoon, including the Trump ones featured in my new book Tiny Hands (let’s not forget to plug the book!), was no less gratifying because what I drew was guaranteed to be published the next day. In fact, it was pretty damn liberating.” Tiny Hands is an unusual collection of cartoons in that Toro publishes the rough sketches for his finished cartoons on the facing pages. “If I recall correctly,” he said, “my thinking was something like, I need to pad out this book! But seriously, I love seeing the creative process. I believe most people do. On Instagram I post short videos of the progress of my cartoons from sketch, to pitch, to finish, instead of just showing the published drawing. Those have been pretty popular. So that’s what gave me the idea. But with these Trump cartoons in Tiny Hands there’s an added bonus of getting to see early drafts that were too risky for publication. For example, the one in which Secret Service agents are pouring over a map marked KGB and saying, ‘We mapped out the Trump motorcade route to the White House,’ the sketch on the facing page shows that my original idea was for the route to spell KKK. Which is equally valid, in my opinion. But it’s unlikely to pass editorial muster. For me that was the trickiest part of lampooning Trump: dialing it down. Toeing the invective line. He’s such a revolting human being who does such unforgivable things and provokes such a visceral response — I had to constantly remind myself to go with the cleverest joke, not the cruelest. In other words, to do what Trump himself is incapable of doing. “In political cartoons,” Toro continued, “the public figures need to be identifiable at a glance, so I had to adjust my drawing style to make a recognizable Trump, Spicer, Bannon, or Elizabeth Warren. Thank goodness for Google images. The Daily Cartoon is unique because it’s a hybrid of political cartoons and, of course, New Yorker cartoons, which means that they’re more topical and pointed than what appears in the magazine but they still hew to the same standards of artistry. For example, there are no name tags or labels. You won’t see a ‘Corporate CEO’ stepping on the neck of a ‘Labor Union.’ Everything has to be communicated through the image in a naturalistic way, as if the scene might actually happen in reality. Well, sort of. “Could a bowl of mushy oranges and dead canaries resemble Donald Trump, and would his advisor accidentally debrief it in the Oval Office? Probably not. But the way I drew it makes the situation believable, if only for a nanosecond, without the aid of explanatory labels. I also used color to boost the humor, taking advantage of Trump’s clownish orange spray tan and his urine-dyed hairdo. (That’s why his comb-over is so yellow, right? It’s saturated in pee-pee?) Traditionally the magazine doesn’t allow cartoonists to use color, although that’s changed in recent years, and I found it amusing to make Trump stand out like a sore thumb. “He’s a pariah, after all. Whether this marks a change in my cartooning style, I’m not sure. My typical character remains a deadpan bystander, cat-like in their lack of facial expression, because it makes the joke funnier. Readers aren’t told how to interpret the moment by the character reactions. Rather, the readers’ own reactions are imprinted upon the scene. I do want to continue to evolve as an artist and I’m always on the lookout for techniques to shamelessly rob from the masters of the craft, but it’s always in the service of humor. Whatever makes the cartoon funnier, I’m all for it. “I should probably be more strategic with how I improve my skills as a cartoonist, but right now it’s left to chance. Whatever collection I happen to discover in a used bookstore, whoever’s work I stumble across and take a shine to, that sort of thing. I tend to make alterations when I get bored with my own work. The same faces, bodies, outfits, living rooms, Medieval dungeons can only stare back at me from the page for so long until I’m desperate for a change. Then I’ll grab a book of Shel Silverstein’s work, for instance, and pilfer his style of drawing a bare foot. It’s important to not get stuck in a stylistic rut. William Steig changed enormously during his time at The New Yorker. So did Charles Addams, actually; his very first cartoons were pen-and-ink, minus the iconic dark wash. “Now, on the other hand, there is value in having a recognizable brand. Readers know immediately that they’re looking at a Bruce Eric Kaplan cartoon, or a Roz Chast. Very few people bother to read the masthead, or even the signatures on the cartoons, and yet they can pick out their favorite artists at a glance. I want to evolve, but I also want to retain (or rather strive to attain) a consistent presence in the magazine. Maslin brings up a story he’d heard Toro tell about their late friend and colleague, Jack Ziegler (who passed away in March). They were browsing in a bookstore and found a collection of George Booth cartoons at the bottom of a stack of books. Said Toro: “Yes, that story about Jack is true. We found a Booth collection, Pussycats Need Love, Too, on the bottom shelf and we both got down on our hands and knees to extract it. Jack quipped, ‘This pretty much describes our relationship to George.’” Recognizing the recent unveiling of a new cartoon editor at The New Yorker, Emma Allen, Maslin observed: “There was a lot of hand-wringing among our colleagues. Were you, are you a hand-wringer? Or are you more a go-with-the-flow kind of person?” “Was there a lot of hand-wringing?” Toro said. “That’s understandable. Being a contributor from the hinterlands of Missouri, I’m not privy to the palace intrigue that goes on at 1 World Trade Center. ... Looking ahead, I’m sure Emma will do a wonderful job. The importance of having a female editor cannot be overstated. Cartooning has been a boy’s club for far too long. I will admit, however, that I’m a little uneasy at my own prospects going forward. Each editor elevates their favorite artists, and reshuffles the roster, and early indications are that I’m not among the preferred group. But who knows. Things are still in flux. Besides, plowing ahead in the face of adversity is my favorite pastime.” To conclude this expedition into NewYorkerland, here is a scan of the cover of Toro’s new book, Tiny Hands, and five of his favorite cartoons, plus his first sale to the magazine.

QUIPS & QUOTES Here’s the Trumpet on his son’s contact with Russians, which he’d effectively denied all along by saying (or implying) that no one on his campaign had any contact with Russians: “I, of course, had nothing to do with Russians. I had no contact with them. And I have never condoned or supported any such illegal activity: I was out on the stump the whole time, making speeches that encouraged my supporters to punch people in the face, which—as I understand it—is not illegal.” Okay: I made that speech up. If he can do it, so can I. Besides, it’s true.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

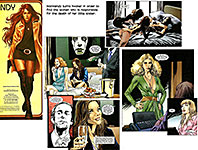

IF YOU THINK comics are better drawn than ever but they’re still all about the spandex set, these next reviews will, I trust, change your mind. The title character in Jazz Maynard, written by Raule and drawn by Roger, is a skilled trumpet player, and he also wields a devastatingly accurate hand gun. The book opens on Jazz and his longtime buddy Teo tied to chairs whereupon they are regularly beaten by their captors. The rest of the book is mostly a flashback, explaining how they got into this predicament. In one of the book’s two completed episodes, Jazz auditions for a chair in the band at a nightclub, plays beautifully, and gets the gig. In the other episode, he storms a brothel, killing all the thugs and guards on his way in, looking for his sister, Laura, who is a victim of sex trafficking. He finds her and takes her home. The underworld, however, is not about to let him get away with this revolt: they find him (and Teo, who is accidentally with him) and tie him to a chair. These episodes prove Jazz to be very talented in two wholly unrelated endeavors, and we also learn he cares about his sister (and, incidentally, other misfortunates). Next, we want to know if he escapes—or, rather, how: I half expected him to shed his bonds with a single bound and gang up on his captors at the end of this issue, No.1. But he didn’t. Raule

tells his tale tautly, but it’s Roger’s pictures that wow. His style elongates

faces and anatomy, and he deploys a I’ll be back.

THE FIRST ISSUE OF Garth Ennis’ Jimmy’s Bastards is intended to introduce us to James Regent, the Jimmy of the title, a James Bond type except, this being Ennis, a little cruder. In the opening sequence, launched in media res, Regent sends jihadists to their flaming death in a crashing blimp, killing most of them en route but rescuing the passengers before being pulled from the plummeting wreck by a bosomy partner helicopter pilot, Olga Trolltunnel (a variation of “toll hole,” slang for prostitute), and after an exchange of double entendre, they go to her place “and shag like rabbits,” as Regent puts it. From this completed episode, we learn that nothing phases Regent, he smirks massively throughout while demonstrating an impressive mastery of gunplay, wholesale destruction and casual seduction. Next comes the Bond-movie interlude during which Regent is introduced to new technology to assist in his next assignment. He also acquires a new Olga, a young and beautiful black woman, and the two banter about his reputation for bedding every woman he sees and her inclination, in his case, not to go along with the program. Then we are transported to a hotel room where Regent is being fellated by one of the two naked voluptuous damsels who are joyfully servicing him. James Bond, as I said—only a little more blatantly sexist. The

book concludes in London’s St. Paul’s cathedral where an army of red-cloaked

zealots has gathered to Russ Braun’s pictures are impressive. He’s captured Regent’s characteristic insouciant smirk perfectly, an expression that virtually defines the character. His work is not stylistically distinguished: it’s pretty much what any thoroughly competent artist would do. He and Ennis know what they’re doing and produce effective and varied visuals for storytelling. And he draws beautiful sexy women. I’ll be back.