|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 364 (March 31, 2017). This posting of Rancid Raves, like all the others, is all just talk, talk about comics and cartooning. Stuff I dote on. So if I wax on at great and unforgiving lengths, well—that’s just that much more talk about comics, and if you, like me, like to talk about and contemplate comics and cartooning, then the feast laid out here won’t be a groaning board but a joyous celebration. There is, perforce, a lot, a lot of talk and a lot of pictures. But maybe you won’t be interested in all of it, right away. We encourage you to scan the listing that follows this preamble, choose the topics you want to spend time with and then scroll down until you get to them. A couple flags, though. Four great cartoonists died over the last month—Jay Lynch, Skip Williamson (within 11 days of each other), Bernie Wrightson, and The New Yorker’s James Stevenson, plus Howard Shoemaker, a long-time Playboy contributor. We eschew the sadness usually associated with pall-bearing in favor of appreciative memorials for them all, with a generous sampling of their work, which is sometimes jocular to the point of iconoclasm. We also contemplate Jack Cole’s cuties and do lengthy reviews of two great graphic novels—Corto Maltese, back in a new translation, and Dieter Lumpen, at least Corto’s equal in the adventuring game. For the legendary European favorite Corto, we do a virtual history of the character and his creator, Hugo Pratt. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Health Care Fiasco Reuben Nominees Tom the Dancing Bug Gets Herblock Sack Gets Thomas Nast Award from OPC Mad Westbound? Archie Into the Movies Malaysia Stops “Beauty and the Beast”—Briefly Bell Wins Berryman Garfield’s Sex Affirmed

Odds & Addenda Guest Appearances in Dick Tracy Bob Mankoff Retires The Pro on the Big Screen? Stan Lee Better FCBD May 6

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE First Issues Reviewed are—: The Old Guard The Visitor Black Road

Also—: The Assignment, Nos.1-3

And Up-dating—: Kill Or Be Killed Wonder Woman 75th Anniversary DC Universe Rebirth Lady Killer

EDITOONERY Appreciating Some of the Best Editoons on— Health Care Debacle The Trumpet’s First Month

ED IS BACK The Return of Editoonist Ed Stein (Who Couldn’t Stand It Silently Anymore)

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Lost Spillane Is Found

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Strange and Wonderful Events in the Funnies

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Reviews of Neglected Books of Interest, Namely—: Classic Pin-Up Art of Jack Cole 1000 Pin-Up Girls

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST Pop Tarts and the Justice League

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews of—: How About Never—Is Never Good for You? My Life in Cartoons Sh*t My President Says: The Illustrated Tweets of Donald J. Trump

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOONS STRIPS Er, Graphic Novels The Adventures of Dieter Lumpen Under the Sign of Capricorn: A Corto Maltese Graphic Novel Exquisite Corpse: Dying To Be An Author

PASSIN’ THROUGH Appreciative Obits for—: Jay Lynch Skip Williamson Bernie Wrightson James Stevenson Howard Shoemaker

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:. Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

The BIG NEWS of the week is that the GOP blew it, demonstrating beyond question the acuity of its nick-nom de guerre, the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm. The Party of No proved that it is only the Opposition Party: it can obstruct and oppose but it cannot legislate. It cannot govern. And on the Other Side of the $ubscribers Wall, we have a short collection, a quartet, of editoons on the subject of the spectacular failure to repeal and replace Obamacare. Until you get there, here’s PBS Newshour’s liberal commentator Mark Shields at the end of that catastrophic Friday, March 24, condemning the Republicons’ colossal fumble in a blistering rant. I’ve never seen him so unreservedly irrate. So angry and disgusted. For so long a diatribe. Here he is—: “Speaking in general—the Republican Part is an opposition party. It’s a protest party. We have a protest President. We have a protest party. It’s not a governing party. It showed itself unable to accept the responsibility in the accountability of government. This bill was not a bad bill. It was an abomination. There was no public case to be made for the bill. There was no public argument to be made for the bill because nobody knew what was in it. There was no public campaign for the bill. No organization—every organization involved in medical care, they were all against the bill. It was a terrible bill. The only organizing principle was that it was against Barack O’Bama. “Paul Ryan, a very earnest policy wonk, showed himself to be an inept political leader. He couldn’t even lean on the safest seats in his party’s caucus. These are people whose re-election is not at all threatened. He could go to them and say, I need you. I need your vote. But he didn’t even do that. “Donald Trump showed he has no understand of the legislative process. He used a lot of colorful words—it’s a wonderful bill, a fantastic bill. But he had no idea what was in it. The art of the deal just collapsed. This is a man who gave away the store to the Freedom Caucus, and he got nothing in return. He didn’t even get their votes. “It was a disaster in public policy and for the country. In no way was this anything but a disaster.” In short, no one—not the Trumpet, not Ryan, not the GOP, not the protest movement, and certainly not the so-called “Freedom Caucus,” the party’s most obstructionist element—came out of this debacle unscathed. In fact, they were all scarred for life. Their action in every sense was, as Nancy Pelosi observed, a “rookie” performance, something attempted by people so grossly unfamiliar with the terrain that they were lost from the very beginning. On Monday, after the intervening weekend’s strife and finger-pointing—a veritable “festival of recrimination,” as E.J. Dionne Jr at the Washington Post put it— back on the PBS Newshour, Amy Water, another of the program’s commentators, noted that the famous Trump style may have worked during the campaign, but it didn’t work in legislation. She mimicked Trump, mocking him: “I can’t tell you about it. But it’s a wonderful bill. Vote for it because you like me.” But that wasn’t enough, she concluded. But it’s enough for now. More later, down the scroll to the Editoonery Department.

REUBEN NOMINEES National Cartoonists Society members have nominated the top five finalists for the 2016 NCS Reuben Award for Cartoonist of the Year. Ballots are now being cast by all voting NCS members, and the results will be announced when the Reuben is presented to the winner at the 71st Annual Reuben Awards Banquet on May 27th in Portland, Oregon. This year’s line-up of nominees is historic in at least two ways. First, it includes more than one token woman cartoonist. And there are more women nominees than men. Finally, two of the five are not syndicated newspaper comic strip cartoonists. Wonders never cease. Cynics among us will frown, saying three women on the ballot will split the “woman vote” and necessarily result in one of the two men winning. So much for cynicism. The nominees and their credits are detailed at the NCS website: Lynda Barry is a cartoonist and writer. She’s authored 21 books and received numerous awards and honors including an Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from University of the Arts, Philadelphia, two Will Eisner Awards, the American Library Association’s Alex Award, the Washington State Governor’s Award, the Wisconsin Library Associations RR Donnelly Award, the Wisconsin Visual Art Lifetime Achievement Award, and was inducted into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame in 2016. Her book, One! Hundred! Demons! was required reading for all incoming freshmen at Stanford University in 2008. She’s currently Associate Professor of Interdisciplinary Creativity and Director of the Image Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison were she teaches writing and picture-making. Lynda was nominated for Cartoonist of the Year for 2016 and will be the recipient of the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award at this year’s meeting in Portland Oregon. You can follow Lynda on Twitter at @NearSightedMonkey. Stephan Pastis is the creator of the daily comic strip Pearls Before Swine, syndicated by Universal Uclick. Stephan practiced law in the San Fransisco Bay area before following his love of cartooning and eventually seeing syndication with Pearls, which was launched in newspapers beginning December 31, 2001. NCS awarded Pearls Before Swine the Best Newspaper Comic Strip in 2003 and in 2006. Stephan is also the author of the children’s book series Timmy Failure. Stephan lives in northern California with his wife Staci and their two children. This is his ninth nomination for Cartoonist of the Year. Visit Stephan’s blog and the Pearls Before Swine website. Hilary Price is the creator of Rhymes With Orange, a daily newspaper comic strip syndicated by King Features. Created in 1995, Rhymes has won the NCS Best Newspaper Panel Division four times (2007, 2009, 2012 and 2014). Her work has also appeared in Parade Magazine, The Funny Times, People and Glamour. When she began drawing Rhymes, she was the youngest woman to ever have a syndicated strip. Hilary draws the strip in an old toothbrush factory that has since been converted to studio space for artists. She lives in western Massachusetts. This is Hilary’s fourth nomination for the Cartoonist of the Year. You can visit Rhymes With Orange online. Mark Tatulli is a syndicated cartoonist who produces two daily newspaper comic strips, Heart of the City and Lio, which appear in 400 newspapers all over the world. He currently has written three books in a children’s illustrated novel series entitled Desmond Pucket, which has been optioned for television by Radical Sheep. He also has two planned children’s picture books coming from Roaring Book Press, an imprint of McMillian Publishing. Lio (a sample of which appears below) has been nominated three times for the NCS Best Comic Strip, winning in 2009. Lio was also nominated for Germany’s Max and Moritz Award in 2010. This is Mark’s third nomination for Cartoonist of the Year. You can follow Mark on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/mtatulli/ and find his Lio strips here http://www.gocomics.com/lio. Ann

Telnaes creates editorial cartoons in various mediums— animation, visual

essays, live sketches, and traditional print— for the Washington Post.

She won the Pulitzer Prize in 2001 for her print cartoons. Telnaes’ print work

was shown in a solo exhibition at the Great Hall in the Thomas Jefferson

Building of the Library of Congress in 2004. Her first book, Humor’s Edge, was published by Pomegranate Press and the Library of Congress in 2004. A

collection of Vice President Cheney cartoons, Dick, was self-published

by Telnaes and Sara Thaves in 2006. Other awards include: the NCS Reuben

Division Telnaes worked for several years as a designer for Walt Disney Imagineering. She has also animated and designed for various studios in Los Angeles, New York, London, and Taiwan. Telnaes is the current president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC). This is Ann’s first Cartoonist of the Year nomination.You can visit Ann’s website, http://www.anntelnaes.com, and follow her on twitter at @AnnTelnaes.

COMIC STRIP GETS THE HERBLOCK The Herblock Foundation's press release: Ruben

Bolling, pen name for

Ken Fisher, has been named the winner of the 2017 Herblock Prize for editorial

cartooning for his weekly page-size comic-strip format cartoon Tom the

Dancing Bug, a free-format cartoon that uses varying types of humor,

artistic styles and formats. It’s an unusual strip in that in any given week,

it could feature a spoof, a multi-panel sketch, political or absurdist humor,

recurring characters or caricatures of real people. But during 2016, political

subject matter was at its heart, as it mostly dealt with the election and the

rise to power of Donald Trump. Judges for this year’s contest were Mark Fiore, editorial cartoonist in animation and winner of the 2016 Herblock Prize; Matt Wuerker, editorial cartoonist for Politico and 2010 Herblock Prize winner; and Martha Kennedy, curator of Popular and Applied Graphic Art at the Library of Congress. Fiore said: “Ruben Bolling’s cartoons are consistently sharp, funny and incredibly original. His use of recurring characters, like Hollingsworth Hound and Lucky Ducky, add a wonderfully inventive richness to his masterful satire. Bolling’s deft skewering operates under the cover of silly cartoon fun.” Said Wuerker: “Ruben Bolling created his own unique style of political cartoon, one that’s full of sly allusions and clever twists. Tom the Dancing Bug pushed the form into new territory with imaginative tropes, deft imagery and provocative allegory. He makes his political points with a humor and writing style that’s fresh and singularly his own.” In his strip, Bolling repeatedly demonstrates his concern about the power of large corporations, saith St. Wikipedia, and satirizes the way government has been corrupted by money. Particularly since 9/11, Bolling's work often concerns war. Many of his strips admit no political interpretation, instead featuring absurdist humor or parodying comic strip conventions. Bolling's lampoons of celebrity culture, such as in the parodic series of comic strips labeled "Funny, Funny, Celebs," can be scathing. It was while attending Harvard in the mid-1980s that Fisher came up with the idea for Tom the Dancing Bug and his pseudonym, Ruben Bolling (which is a melding of the names of two favorite old-time baseball players, Ruben Amaro and Frank Bolling). The strip originally ran in the Harvard Law School Record. St. Wikipedia quotes Bolling: “I started Tom the Dancing Bug in 1990 in a small New York newspaper. It was called New York Perspectives, then it was called New York Weekly, then it was called ‘bankrupt.’ But before it went bankrupt, I was able to sell the strip to a few other papers. For seven years, I was sending packages out and following up with phone calls, trying to get editors to run the strip. I ended up selling it to about 60 newspapers [under the name Quaternary Features]. I was surprised at the success I had, especially in selling to daily newspapers. I didn't think it would be my market. “Then in 1997, the Universal Press Syndicate approached me and asked if we could work together. That came at just the right time, as I was starting a more serious day job, and I was about to have my first baby. I just didn't have the time and energy to devote to the selling of the strip. I decided that whatever job they did would be better than whatever I could put forth at that time.” You can see more examples of the Bug that Dances by Googling “Tom the Dancing Bug.” Happy hunting. This

year’s Finalist (runner-up) is Marty Two Bulls Sr., a freelance Oglala

Dakota cartoonist who has drawn editorial cartoons for the Indian Country Today

Media Network since 2001. He will receive a $5,000 after-tax cash prize. Fiore

commented: “The cartoons of Marty Two Bulls, Sr. take a hard-hitting look at

issues impacting native peoples. His bold style screams with powerful messages

that have been overlooked by much of society. Two Bulls’ strong work

exemplifies a courage and ferocity that is the lifeblood of a good political

cartoon.” On his blog, Bolling said: “I'm very honored to have won the 2017 Herblock Prize. I thank the Herblock Foundation and the judges. And thanks to all the very kind congratulatory words from folks all around social media. I'm proud to share the award (but not the prize money) with my partners and absolutely essential friends: Boing Boing, which premiers Tom the Dancing Bug on the Web every week, Andrews McMeel Syndication, which distributes it to my great and valued newspaper clients, plus Daily Kos and GoComics... and of course, that motley squad of the greatest heroes, ne'er-do-wells, gamblers and outlaws ever assembled, the Proud & Mighty INNER HIVE, without whom, truly, none of this would be possible. “And congratulations to the Herblock Finalist Marty Two Bulls Sr., an Oglala Dakota artist and cartoonist who does fantastic and very diverse work.” The Herblock Prize is awarded annually by the Herb Block Foundation for “distinguished examples of editorial cartooning that exemplify the courageous independent standard set by Herblock.” The winner receives a $15,000 after-tax cash prize and a sterling silver Tiffany trophy. Bolling will receive the Prize on March 29th in a ceremony held at the Library of Congress. Representative John Lewis, the U.S. Representative for Georgia's 5th congressional district, will deliver the annual Herblock Lecture at the awards ceremony. Tom the Dancing Bug, distributed by Andrews McMeel Syndication to many newspapers across North America, also appears on: BoingBoing.net, one of the most linked-to websites in the world; DailyKos.com, the U.S.’s largest progressive blog; and Gocomics.com, the largest comic strip website. Ruben Bolling was the Finalist for the 2016 Herblock Prize, the 2014 winner of the Society of Illustrators Best Cartoon Award in its Art Annual, and in 2011, Bolling won the Sigma Delta Chi Award from The Society of Professional Journalists, for Editorial Cartooning. Tom the Dancing Bug has been twice-nominated for the Harvey Award for Best Comic Strip or Panel, and has won the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies Award for Best Cartoon five times.

THOMAS NAST AWARD GETS SACK On Tuesday, the Overseas Press Club announced that the Minneapolis Star Tribune’s Steve Sack is this year’s recipient of its Thomas Nast Award for editorial cartooning. Sack, whose work won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize, says he is “immensely honored” to be recognized by the OPC, even as he emphasizes the role of the press in 2017. “Technology may be shrinking our world, but without the work of professional journalists to sort out what’s truly of value, we’d be left with nothing but gibberish, commercial pablum and government spin,” Sack tells Michael Cavna at the Washington Post’s Comic Riffs. “The press is my window to the world. To have my cartoons recognized by those whose efforts I depend on every day,” he adds, “is most gratifying.” The OPC judges said that “Sack successfully harnessed all the cartoonist’s tools — caricature, composition, biting wit and solid journalism — in his impressive portfolio.”

The OPC also awarded a finalist (runner-up) citation to Adam Zyglis of the Buffalo News. “I was extremely happy to see Steve Sack win the top prize,” says Zyglis, who won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize. “He is a true master of the craft, and is at the top of his game right now. To be a finalist behind someone of his caliber is humbling.”

MAD FOR THE COAST? Mad caricaturist Tom Richmond pondered the fate of Mad magazine on Wednesday, March 22, to wit—: A week or so ago Bleeding Cool broke the news that Mad was apparently following the rest of DC Comics out to Burbank “soon.” Back in 2013 when DC announced they were moving out of NYC and to Burbank, I wrote this post speculating on what would happen with Mad. The short version offers four possible scenarios: 1. Enough current Mad editors and art staff make the move that Mad remains the Mad we know and love. 2. DC bankrolls a small, separate Mad office in NYC, and Mad remains the Mad we know and love. 3. DC forms a new editorial and art staff to continue Mad out west, and we have no idea if Mad remains the Mad we know and love. 4. DC cancels Mad magazine. Turned out that No.2 was what happened. Now it seems we will see one of the other options take place. Several people have written to ask me if I will still continue to draw for Mad, if the editorial staff will make the move, or what in general will happen. I have no answers. My general sense is that, of the three remaining possibilities above, No.3 is the most likely. I do not foresee many or any of the current staff pulling up stakes from the city most have lived in their whole lives and moving to the world of bean sprouts, infused water, and suntans, but as far as I know, no one on the current staff has made any official decisions. Mad is a valuable brand for DC Entertainment and that brand is much more viable with a magazine in production, so I do not think No.4 is likely. As for what kind of changes will take place if scenario No.3 is indeed what takes place, your guess is as good as mine. I think we will see some big changes, though. Mad has always had a distinct New York flavor to its voice, from the Yiddish slang it’s always incorporated to just a general NYC sensibility, I do not see that flavor continuing on. A new staff will bring new voices and new directions. My work may or may not have a place there. Lots of unknowns. Time will tell.

ARCHIE INTO MOTION, BIG TIME In the wake of the launch of “Riverdale” on tv at CW, Archie Comics has signed an exclusive deal with Warner Bros Television to develop more of the publisher's properties for television and original content. As Archie CEO Jon Goldwater tells The Hollywood Reporter, the deal extends beyond the traditional Riverdale crew of Archie, Betty and Veronica as seen in the current CW series. It could include lesser-known properties, including "America's Queen of Pin-Ups and Fashions" Katy Keene, as well as the superheroes of the company's Dark Circle imprint. Said Goldwater: “Archie is unique in that we have a huge library of characters that are not only recognizable, but they’re successful and entertaining. Everyone knows Josie and Sabrina. Beyond that, we have an entire pantheon of heroes and villains that are perfect for tv or movies. Not to mention Black Hood and Sam Hill, just to name a few. The possibilities are endless, and I can’t wait to start talking about what we have coming up.” “Riverdale” creator Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa told reporters last month he was interested in creating a whole Archie world. The series, with its dark tone and sexy new murder mystery plot, has been a critical hit. The deal is similar to Warner Bros tv’s pact with DC Comics, which has seen it put a whole stable of series on the air, including CW's Arrow, The Flash, Legends of Tomorrow and Supergirl, as well as Fox's Gotham and NBC's Powerless. “Riverdale's” success and the tv pact marks the latest stage in Goldwater's push to modernize Archie as a company, which started with the 2010 introduction of Kevin Keller, the first openly gay character in the publisher's long history, and continued with the launch of a series that featured an adult Archie struggling with life post-marriage (to both Betty and Veronica; the series ended with his death). Coinciding with news of the Warner Bros deal, Archie revealed that Mark Waid, the writer of flagship comic book series Archie, will be expanding his relationship with the company later this year by signing up to co-write a number of series, as well as mentoring upcoming writers, with the overall aim of growing the current stable of talent at the company. Goldwater, asked if he is experiencing a “sense of vindication” in seeing the success of his drive to get the characters accepted once again by a mainstream audience, said: “Yes, there’s a huge sense of vindication. This deal with Warners is in many ways a culmination of the work, along with the amazing staff and freelancers who work at Archie, to bring these characters forward into the present day. To show that Archie is an iconic brand that is flexible, relevant and energized. It’s still Archie, and people want more of him and his friends. In the same way Batman can be dark, bright and funny or off-kilter, Archie can, too. He’s part of a pantheon of select characters and brands that are part of America. They’re part of the consciousness, so there’s a built-in knowledge there. “We knew we could widen the scope a bit, and show people that Archie could be Archie in a variety of settings. We could have an older Archie dealing with job woes and marital problems, we could bring Archie into alternate realities and face off against things like Predator or Sharknado. We could be fun again. “The moment where I could finally sit down and say “Okay, now we’re ready to roll,” Goldwater continued, “was [2015's] Archie No.1, by Mark Waid and Fiona Staples. This was ground zero for the company. This was a rebirth. This was an Archie for today’s reader. Obviously, we still cherish and respect the classic Archie stories — we still produce them because that audience is hugely important to us. But the ‘Death of Archie’ was more than a publishing stunt. It was a metaphor for the company. That Archie had to die, saving Kevin Keller, the face of the new Archie brand, to ensure the company would continue. “As long as the story is good,” he went on, “—and as long as the characters are true to themselves — you can do anything with them. The Archie in Afterlife and in the new Archie series is the same Archie you see in other comics. Sure, the content can change, but at its heart, that’s Archie. Same goes for ‘Riverdale’ on tv. And that’s what unites fans. There was a time when Archie Comics only produced a certain kind of book. So, once you grew out of those books, you had nowhere to go. So you’d move on to different stuff from different publishers. That’s not the case anymore.”

GAITY IN MALAYSIA IN “BEAUTY AND THE BEAST” Malaysian censors recently ruled that a brief, gay-themed scene in the movie involving two male characters dancing promoted homosexuality, but Walt Disney Studios refused to cut the scene, meaning the film did not open there on March 16 as scheduled. The sequence, reported Reuters, is said to be three seconds long. “The film has not been and will not be cut for Malaysia,” Disney said in a statement on March 14 without elaborating. The film, starring Emma Watson and Dan Stevens, is a live-action remake of Disney’s 1991 animated blockbuster of the same name. The film’s director, Bill Condon, confirmed that the scene in question — involving a character named LeFou, manservant to the villain, Gaston — is an “exclusively gay moment.” Oddly (as either John Oliver or Bill Maher—forgot which—observed), the Malaysians have no objection to bestiality—a woman falling in love with an animal. THE FILM IS PROMOTING HUMAN-ANIMAL SEX! Where’s the outrage? Geez. Abdul Halim Abdul Hamid, chairman of the Film Censorship Board, argued Wednesday that Malaysia was not preventing the movie from being screened. “It is in our guidelines that we don’t allow LGBT activity in movies in Malaysia,” he said in an interview. “They are the ones not allowing the movie to be shown. We approved it with a minor cut.” He said the movie would have been shown with a PG-13 rating had Disney agreed to cut the scene. Malaysia is a Muslim-majority country, and sodomy is illegal there, although the law is seldom enforced. The capital, Kuala Lumpur, has a thriving gay community. With about 30 million people, Malaysia is a small part of Disney’s overall audience. “The Jungle Book” last year had $967 million in global ticket sales, and Malaysia represented $5.7 million of that total. In 2015, “Cinderella” took in about $540 million globally, with Malaysia contributing $4.5 million. Russia agreed last week to let “Beauty and the Beast” be shown there, but it barred children under 16 from attending unless accompanied by someone over 16. A Russian lawmaker had called for it to be banned entirely, saying it was “blatant, shameless propaganda of sin.” Kuwait, another Muslim-majority country, pulled the film from cinemas after it had been showing for almost a week. Again, the cause was concern over the gay scene. Nobody minds that this bimbo is fucking a horny buffalo. Right: no one really minds. Brooks Barnes at nytimes.com reports that “Beauty and the Beast” achieved “an astounding $170 million in ticket sales at North American theaters over its opening weekend (March17-19). That total broke multiple Hollywood records, including one set last year by ‘Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice’ for the biggest March opening.” Back in Malaysia, the authorities ultimately overturned the Film Censorship Board’s earlier ban against “Beauty”: the movie opens, nation-wide, on March 30. Perhaps tourism played a part in the reversal: Tourism Minister Nazri Aziz, reports Richard Paddock at nytimes.com, objected to the prohibition, calling it “ridiculous. ... You don’t ban a film because of a gay character,” he said. “All these years even without the gay character in the ‘Beauty and the Beast,’ there are also gays in the world. I don’t think it is going to influence anyone” (to become homosexual). Meanwhile, in the ensuing days, another American-made movie, “Power Rangers,” has apparently escaped B&B’s fate: the movie is the first big budget superhero movie to have an LGBT protagonist, but it got a green light from Malaysia’s censors until they found out that the Yellow Ranger, Trini, may be lesbian. The censors wanted to have another look. But, perhaps cowed by international outcry over the B&B censorship, they let “Power Rangers” slip into the country’s theaters, unscathed, reports Patrick Brzeski at hollywoodreporter.com.

BELL WINS BERRYMAN—AND MORE Darrin Bell of the Washington Post News Service and

Syndicate is the winner of the 2016 Clifford K. and James T. Berryman Award for

Editorial Cartoons. He went to Washington to receive the award and reported on

a memorable experience there, visiting the Smithsonian National Museum of

African American History & Culture. He began by admitting that he was nervous about his pending speech before thousands of journalists. He and his wife and daughter planned to visit the Lincoln Memorial before the presentation ceremony, but en route, they stopped at the Smithsonian’s African American Museum. “I won’t describe what we witnessed in that museum. I’m sure you can find descriptions elsewhere, but I think it’s something that’s so powerful, and so personal, that it shouldn’t be spoiled. There is something in there that’s going to stop you in mid-step and make you feel more than you thought you would. And that something is different for everyone. ... But I will say this: there comes a point, after you’ve literally risen through the centuries of struggle, persecution, and contributions of slaves and their descendants, where there’s a reflection room. You sit by a fountain that rains down from the high ceiling and come to terms with everything you’ve just seen. … Or you try to. “I’m

the great great great grandson of slaves whose contributions to America were

ignored and lost to history. And here I was in the nation’s capital, about to

accept an award for my contribution to the national conversation. One of the

least important realizations I experienced in that reflection room was that

compared to everything I’d just seen, standing up before thousands of people

and saying a few words was nothing at all.”

GARFIELD IS A BOY Wikipedia’s editors have apparently be arguing about the orange cat’s sex. The controversy, saith the Associated Press, began a couple years ago after Garfield’s creator Jim Davis told a viral content site Mental Floss that as a cat, Garfield is “not really male or female.” By which he meant, I think, that as a cartoon character, Garfield, like all cartoon characters, “is not perceived as being any particular gender, race, age or ethnicity ... so the humor can be enjoyed by a broader demographic.” But that was enough to send fans off into the outer reaches. Davis has now set the record straight, telling the Washington Post that Garfield is male and has a girlfriend named Arlene.

ODDS & ADDENDA ◆ Mike Curtis and Joe Staton keep bringing into their Dick Tracy more and more walk-ons by characters from other strips. The current adventure, which has Will Eisner’s the Spirit partnering with Tracy, has also seen the arrival of Daddy Warbucks and Mr. Am from Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie, and Hotshot Charlie and the Dragon Lady from Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates. There are so many guest appearances that the plot has wandered off into a weedy vacant lot next door, a typical outcome when a parade of secondary characters takes place because each requires some background explanation or a few minutes in the spotlight alone. ◆ Bob Mankoff, the cartoon editor at The New Yorker, is stepping down at the end of April after more than 20 years at the job; Emma Allen, another editor at the magazine, will assume his position, but Mankoff won’t be leaving the magazine’s pages: he plans to contribute his own cartoons regularly, and he’s also editing a new anthology, The New Yorker Encyclopedia of Cartoons, scheduled for publication in 2018. Harv’s Hindsight of a couple weeks ago has all the details—his life, career, impact on the magazine, etc., including ample evidence that New Yorker cartoons are meant to induce knowing chortles rather than guffaws. ◆ Paramount Pictures has picked up rights to The Pro, a graphic novel with a comically sleazy heroine by Garth Ennis and Jimmy Palmiotti, lovingly drawn by Amanda Conner. Erwin Stoff of 3 Arts is producing and Zoe McCarthy has been hired to write the screenplay. She is best known for her script “Bitches On A Boat.” ◆ Stan Lee got fans all in a swivet over the past few weeks. He has cancelled appearances at a few conventions, including Big Apple Comic Con and Salt Lake Comic Con FanX, due to health issues. But, at 95, he’s bound to have some off-days. In any event, he has taken to Facebook to let fans know his health is improving: “Been feeling almost back up to snuff,” he posted. “So time to send out the battle cry: Excelsior!” ◆ This year’s Free Comic Book Day (FCBD) is May 6, as usual, the first Saturday in the May. Go to your local comic book shop and see what you can get for nothing; most shops set a limit—say, 4 titles to a customer. But four free is better than no free.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles indexed at https://www.facebook.com/comicsresearchbibliography/, and eventually compiled into the Comics Research Bibliography, by Michael Rhode, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO One-liners for the day—: I try to take one day at a time, but sometimes, several days attack me at once. All I want is a warm bed, a kind word, and unlimited power. How can you tell a macho woman? She rolls her own tampons. Current death rate: one per person.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

GREG RUCKA tells us on the inside front cover of The Old Guard No.1 that “this is a fairy tale of blood and bullets. It is the story of one woman and three men who cannot die. Mostly. Their names are Andy, Nicky, Joe and Booker. It is a story about time, and age, and ages, and about friendship, and love, and regret.” From poetry, we jump immediately into scenes of violence—then a bedroom, where Andy, the woman in Brubaker’s quartet, arises and dresses and leaves the man in bed, not wanting to know his name. The opening episode reveals Andy hard-nosed character—her passion and her longing for something better (“Will this time be the one?” she asks herself) and also her stark and stoic realism: no, it won’t be. Andy and her cohorts are given an assignment to rescue 17 girls who have been kidnaped in North Africa. They accept the assignment, and as they pack up to leave Barcelona, where they are at the moment, the story shifts to Afghanistan, where we meet Nile and Stacy, two American women marines who are trying to find a local bad guy. They find him and shoot him, and as he lies there, bleeding, Nile tries to administer First Aid; he pulls a knife and stabs her. Then we’re back with Andy and her crew, raiding the compound in North Africa where the 17 girls are supposed to be. They get liberally bloodied as they kill lots of bad guys, but the girls are nowhere to be found. It was, they decide, a setup. All the action was filmed and sent off to some other bad guys. “They saw the whole thing,” says Booker, “—we’ve been made.” Then we’re back in Afghanistan where Stacy and Dizzy go to the sick bay and find Nile awakening and in fine fettle. But Stacy has just told us that Nile died in her arms of that knife wound. So what’s going on? The next issue, we are promised, will reveal a “new immortal.” My guess—Nile. And the reason Andy and her pals survive the blood bath in that compound is that they are the immortals Brubaker talks about inside the front cover. We finish with two mysteries—two cliffhangers: who (or what) set up Andy and her crew and why; and how did Nile survive dying? There are, altogether, five complete episodes in this inaugural issue. And each one gives us information vital to understanding the episode as well as abbreviated character studies of the principals; the mysteries do not cloud the action, making it incomprehensible. We also gain a little insight into whatever mcguffin Brubaker is pursuing. His storytelling is deft, but Leandro Fernandez’s pictures are breathtaking. His breakdowns advance the story quickly— sometimes, in the action sequences, breathlessly, shifting focus rapidly from close-ups of weapons firing to long shots showing dropping bodies. His page layouts are inventive, panels overlapping. And everywhere, solid black molds figures and establishes setting and mood. Heavily shadowed scenes are sometimes shot through with stark beams of light.

There are virtually no storytelling captions—the few that are sprinkled across the pages are Andy’s first person narrative, not an omniscient observer’s. Fernandez’s pictures—panel compositions and page layouts—carry the story, often silently. This is comics the way it ought to be, kimo sable. I’ll be back.

JUST AS I THOUGHT HE WOULD, Paul Grist proves a perfect illustrating partner for Mike Mignola’s newest undertaking, The Visitor: How and Why He Stayed, as much about Hellboy as it is about the Visitor. Assisted by Chris Roberson, Mignola tells the story of Hellboy’s early years, beginning with his arrival December 23, 1944, when he pops into view in front of some soldiers in World War II Europe, one of whom is actually an alien visitor who possesses the mysterious Prism, a card-like iphone-looking object that he almost deploys against the infant Hellboy. But he stops just as “Archie” shows up to plead for Hellboy’s life. The soldiers put their guns down, and the alien wanders off into the forest where he communicates with his commander aboard a space ship hovering somewhere in the upper atmosphere. The alien explains that he decided not to kill “the destroyer” (i.e., Hellboy) because he was “just a child.” “He is his mother’s son as well as his father’s, after all. The future is still in motion. There is still hope for him. Hope for redemption. He is an innocent. He cannot be blamed for the circumstances of his birth.” The alien decides to remain on Earth and monitor the child’s progress. His commander’s space ship scoots off into space, leaving the alien behind. For the rest of the book, we have glimpses of Hellboy as he is growing up—in 1947, 1948, 1950 (by which time, he’s broken off most of his horns), 1953 (by which time he’s joined the paranormal investigative agency), and 1954, when he goes into the woods and kills a dragon. The panels of these pages are laid out against black solids which accent an increasing number of drops of blood, falling across the scenes. All this time, a trenchcoated figure lurks in the background, watching. It’s the alien. And as he watches lilies growing out of the dragon’s blood, he marvels: “It never occurred to me until this moment that the child might grow into a force for good in his own right. ... I shall watch how he progresses.” And we’ll watch with him for the next 4 issues of this 5-issue run. Mignola’s story is the usual constipated narrative, pregnant (to mix a metaphor) with lurking unknowns and half-explained knowns, exactly the sort of mysteriousness-clogged tale that could annoy more than it entertains. But completed

episodes reveal the storytellers’ competence—the opening gambit, the vignettes of Hellboy’s life through the years, and the final triumphant encounter with the dragon—and the tale moves forward, promising some sort of resolution ultimately. And for that, we’ll return. Grist’s pictures, like those of Mignola, are drenched in solid blacks and are often mute, their silence—their noncommittal presence—underscoring the unexplained by not explaining, lending to the entire enterprise a haunting atmosphere, the sort of thing at which Mignola is so expert. We’ll be back. Wouldn’t miss it. Especially since it promises to tell us more about Hellboy.

A GIANT HULK OF A MAN named Magnus—“Black Magnus”— is the protagonist of Brian Wood’s Black Road No1. He takes a job escorting a priest to the northern country, protecting the cleric against attacks from thugs that lurk along the Black Road to the north. But they are attacked and the priest is brutally killed, impaled by three huge swords. Magnus is badly beaten, but he survives because he is nursed back to health by the priest’s “guardian angel,” a young woman named Julia, who is the priest’s adopted daughter. She asks Magnus to take her north, and he, having accepted pay already for the priest, agrees in order to fulfil his contract. One

of the complete episodes is the recruiting of Magnus, a short scene in which a

friend tells him of a contract opportunity; another, longer, is the fight

between Magnus and the roadside thugs—four pages of silent swordplay. In both,

Wood proves adept. But not without the storytelling authority of Garry Brown,

whose rugged bristling drawing style adroitly conveys the brutal ambiance of

the story, etching forms with tiny fragile lines and then deeply shadowing

them, turning them into crude but deft images that evoke the primitive time and

place. Magnus narrates the tale, laminating his recitation with commentary as he goes. His country is being invaded by Christians, who seem, unexpectedly, to be the villains: “They preach peace and love in the midst of performing incredible violence,” Magnus says. He hasn’t decided whether he will “go to war for the Christians or against them.” The book opens with a page of straight text that tells of a small fleet of cargo ships delivering their cargo and then being attacked and sunk—seemingly, by the Christians. The next two pages are silent, devoted to picturing a bleak country side into which Magnus stalks, carrying a dead body on his broad shoulder. Then he buries the body under a pile of rocks. None of this is explained. We next see Magnus in town, being recruited to escort the priest northward. Apart from Brown’s appealing pictures, the attraction of the tale for me is in the casting of Christianity in such unfavorable light. Magnus is the witness whose testimony paints the Christians so villainously. Is he wrong? Possibly. But if he’s right, Wood’s book will be a startling deviation from the norms of the society in which it is produced.

VIOLENCE, SEX and revenge are the boundaries within which Matz (aka Alexis Nolent) adapts one of the strangest stories in comics by Walter Hill and Denis Hamill. Drawn in a wispy but thoroughly confident realistic manner by Jef (Jean-Francois Martinez), The Assignment tells the story of killer-for-hire Frank Kitchen, who takes one assignment too many. One of the people for whom he regularly kills, Gleason, turns on him, selling him off to a perverted plastic surgeon, who, over several months, performs an operation upon the unconscious Frank without his consent. When Frank wakes up after this long sleep, he removes bandages from his face and sees—the face of a woman. He then looks at his body and sees—the body of a woman.

In the first of the 3-issue run, we see Frank at work—killing one of his assignments—then accepting Gleason’s next assignment, which turns out to be a trap. The issue opens on a two-page sequence during which we see Frank’s bandaged face and hear him, as the narrator of the tale, vow vengeance. At the end of this issue, we see the female Frank in all his (her?) naked glory. In the second issue, we follow Frank as he comes to grips with his new body, finds a way to temporarily make a living, and tries to figure out what has happened to him. And why. In the third issue, he goes after Gleason. Frank has given up none of his tough-guy abilities by having a woman’s body: he kills his way through body guards and snitches until, at last, he finds his target. Gleason tells him why he sold him to the surgeon, a woman. And we learn that the surgeon turned Frank into a woman to avenge Frank’s having killed someone close to her. Frank then goes after the surgeon, but he doesn’t kill her. His revenge is somewhat sweeter. After that, Frank becomes a vigilante, killing the men who make sex slaves of young women. Sex scenes are as plentiful in the series as killing sequences. Each of the three issues has an explicit scene (explicit nudity, not explicit copulation), each serving the tale’s larger narrative purposes. Interviewed in No.2, Matz says the parts of the story he likes best are those where Frank, with his woman’s body, attracts the attention of thugish guys “who assume she’s weak and think that they can take advantage of her—and who are ultimately headed for a world of pain.” Jef says: “The sex scenes were the ones I enjoyed drawing.” I suspect he grinned as he said it. Leered even. Poised against Frank’s first-person narrative are a series of episodes of a psychiatrist interviewing a woman in prison. The woman, it eventually develops, is the surgeon, and it is during the last of these interviews that we come to know Frank’s revenge, the last twist in an ingeniously twisted tale of many parts, all artfully woven together. In sum, an accomplished piece of writing. Hill, a Hollywood screenwriter-director, took the story from Hamill and turned it into a movie script and then a graphic novel story that he gave to Matz to adapt. After breaking the story down, Matz turned it over to Jef, who drew The Assignment. Jef’s illustrative manner bristles with tiny lines and is crammed with detail. The books’ coloring gives every picture a gray haze; we watch as if through a scrim, a provocative effect. Much of the modeling is accomplished by careful smudging, which has the same visual value as the graying. The storytelling—narrative breakdown, panel composition—is expert: Jef and the writers/adapter let pictures tell the tale in much the manner of a motion picture—action and dialogue combine to achieve dramatic impact; Frank’s narrative captions filling in the blanks. The book, the accomplished execution of a shocking premise, is published under the Hard Case Crime imprint of Titan Comics, and there are several other titles in the same mode—Peepland and Triggerman (the latter conducted by the same creative team as did The Assignment).

Riffling Pages. When we last left Dylan, Ed Brubaker’s deranged protagonist in Kill or Be Killed, he had just killed another of the deplorables—some sort of sexual predator—that he’s determined don’t deserve to live, and just as he turns to leave the scene of his crime, he’s confronted by a cop with a pistol drawn and pointed at him. In No.6, the next issue, he escapes, miraculously, and then the narrative shifts as he tells us about a police officer named Lily Sharpe who has apparently figured out that four recent murders are the work of one vigilante killer. Dylan, who is the book’s first-person narrator, explains his knowledge of Sharpe’s thinking with a single bound: “Obviously,” he says, “I didn’t know that was happening at the time—call it artistic license.” Reminds me of one of Louis L’Amour’s books, To the Far Blue Mountains, in which the first person narrator, Barnabas Sackett, dies on the last page. (Well, think about it: how’d he manage to write that whole book while expiring there in the woods?) The

presence of Lily Sharpe means that Dylan will eventually get his just desserts,

a happy prospect. Meanwhile, Sean Phillips continues to produce

wonderfully detailed New York street scenes like the one at the left at the

bottom of the page posted near here. One of the remarkable aspects in that

picture is that not all the buildings have the same facade: in particular, one

on the left seems to be an older, more elaborately designed building.

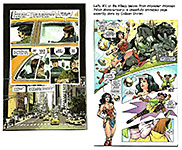

Wonderful. Wonder Woman 75th Anniversary No.1 exists only to celebrate the Amazon’s anniversary by providing as many visual interpretations of the character as can be crammed—often without a story to tell—into its pages. There are 10 pin-ups and as many short narratives, some of Brian Bolland’s covers and unused sketchkes from 1992-1995, and a faux interview with Lois Lane. The interview, staged on the celebrity-journalist-encounters-another-celebrity model, is insightful in the frilly manner of the genre; not much more. The perennial problems with Wonder Woman are on display—the boring preoccupation with the Amazonian life on the island of Themyscira and whether WW is a sex symbol or a warrior. Riley Bossmo goes much too far in the direction of the warrior, producing a Wonder Woman more masculine than feminine. But I was happy to see Fabio Moon’s too brief interpretation of the character and Jill Thompson’s. Collen Doran’s version is the best, combining both sex appeal and lively action. DC Universe Rebirth is an extravagant “deluxe” hardcover edition published in 2016. A lot about the Flash and Wally West, but the real hero seems to be Batman. The book offers pages and pages of swirling vapor and lightning bolts that are intended, doubtless, to signal a cosmic significance. Pages are jammed with close-ups of grimace and cramped gesticulating hands like claws. The tale begins with images of the face of a watch being deconstructed and ends with images showing the watch being reconstructed, resulting, finally, in the Watchmen smiley face with a drop of blood on it. The accompanying captions repeat some of the last words in Alan Moore’s Watchmen— hence, this book heralds the impending arrival in the DC Universe of Moore’s universe. Or so we suppose. At

the end are several pages showing costume designs for various of the DC roster

of superbeings, including one of Wonder Woman. Her skirt now seems vaguely

Grecian but more practical and warrior-like than the bikini bottom of recent

years; but the eagle on the neckline of her bodice has always baffled me: its

pointy beak, presumably metal, is pecking away at her bosom right where the

cleavage starts. Wouldn’t that be terribly uncomfortable for a woman in

action? In Lady

Killer 2 No.4, Josie Schuller has decided that Irving, her erstwhile

clean-up man, is too lethal to keep around. He keeps killing people that he

believes she wants dead—like her huband’s boss, f’instance, whose body he stows

in the Schuller family freezer. Meanwhile, Josie’s

The Funniest Vulgar Line of All It happened on the March 9th tv broadcast of ABC’s “The Catch.” The scene opens and the screen fills with a picture of an Adonis of a man, flexing his muscles with a smirk of a self-satisfied smile on his face, naked from the waist up (and, as we soon conclude, from the waist down, too). The camera pans to the right where we see a bed upon which Margot Bishop, Ben’s criminal mastermind sister, reposes in a frilly gown, studying a sheaf of papers in her hand. She glances up long enough to see what her Adonis is up to (pardon the expression), and she reacts: “Careful,” she says, looking back to her papers, “—you’ll poke someone’s eye out.” I had to get this written down. The funniest vulgarity of all. So funny, it ain’t vulgar anymore. Quotes & Mots The Southern Poverty Law Center reports that the Trumpet’s election has electrified far-right extremists and ushered a white nationalist agenda into the White House. White supremacists were ecstatic on election night. Many expressed the belief that they finally had a friend in the White House. Immediately after the vote, the SPLC exposed a wave of hate crimes and other bias-related incidents that swept the country. It documented a surge of classroom bigotry spawned by Trump’s xenophobic rhetoric—and then created resources to help teachers protect vulnerable students from harassment. And it played a role in helping the media and public understand the extremist ties of some of Trump’s appointees and closest advisors—including Stephen Bannon, who helped nurture a growing white nationalist movement. The SPLC also began pushing back in the courts against a White House that appears set on rolling back decades of progress. “Our country hasn’t seen this kind of extremism in the White House in modern times, if ever,” said SPLC Prez Richard Cohen. “But at the same time, our country’s ideals of equality and justice are deeply rooted and our democracy is resilient.” —From the SPLC Report, Spring 2017

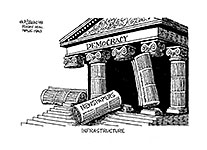

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy

When Trump says words, what do the words mean? —Quoted from John Oliver’s “Last Week Tonight”

You’d think, judging from the nation’s editoons last month, that nothing except Trump was happening in the world. No war in Syria. No refugees in Europe—or drowning en route from North Africa. No wholesale starving in South Sudan. (And the Trumpet wants to cut back on foreign aid.) Nothing. It’s all Trump. El Trumpo is everywhere on the covers of the nation’s magazines.

No surprise as progressive (or, at least, left-leaning) magazines turn their covers into political cartoons with him as the butt of the jokes—not how he imagines himself as a cover subject—but even Time, ostensibly an objective news organ, ridicules him. He appears as a Roman emperor in mid-tantrum, a revolutionary with an evil counselor at his ear, a comic strip character (in Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury), and a phallic symbol (by Massimo Calabresi). For the second time, Time has deployed its cover as a political cartoon, poking fun at the holder of the nation’s highest office. Letters to the editor in the next issue of the magazine complained about it (March 27). Not about making a joke of the Trumpet, though—but about making him the cover subject too often (three times this year) or missing the point: Trump constructs rather than destructs, saith one reader. Another reader, noting the condition of the Washington Monument, asked: “Is Trump causing D.C. to crumble or is he keeping it from collapsing?” Shrewd observation. But these comments miss the point. Or points. With his nefarious red necktie pointing to Trump’s proudest achievement, he stands erect but leaning slightly on the nation’s most famous phallus, which is cracking and crumbling due to the proximity of childishness instead of machismo. The other point is ironic: the Washington Monument commemorates the man who, in legend, was the nation’s first abject failure: he could not do what Trump does so blithely every day. And then came Friday, March 24, and with it, the most confounding moment in the history of the majority Republicon party in decades. Given the opportunity to govern, the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm simply flopped. It could not get up for the task. It failed on every front, a vivid demonstration of its ineptitude. Bringing forward the bill that would repeal and replace Obamacare, the GOP proved itself, as House minority leader Nancy Pelosi said, to be rookies, rank amateurs. Neither politicians nor leaders. And certainly not statesman of any description. Theirs was a staggering failure, and on the sidelines, astonished criticism burst forth from virtually every quarter almost immediately. (I’m propounding another of my notorious rants here, so if you want to skip the vituperative contumely, scroll down to the paragraph that begins with ALL CAPS. Thank you.) Syndicated columnist Kathleen Parker dripped sarcasm: “In a week that felt like a month, Americans got a clear view of Donald Trump’s governing style and also of his fabled deal-making approach: Do as I say or you’re dead to me. ... “Trump, who promised to repeal and replace (as has nearly every Republican the past seven years), has no patience with process [of legislation]. As the chief executive of his own company for most of his life, and notwithstanding his reverence for his deal-making skills, he prefers quick results. And, hey, if things don’t tumble his way, well, there are other greens to sow and mow. And, certainly, a 30-foot wall to build. “He gambled on his own power to persuade (or bluff), the result of which could leave him holding Obamacare and conceding failure. [And it did just that.] What, then, do Republicans tell their base? And what would this say about the party in power? After years of harping on the collapsing health care plan installed by President Obama and the then-Democratically controlled House and Senate, they had their opportunity to govern responsibly. “You’d think seven years would be ample time to cobble something together that could replace Obamacare. The fact that Republicans didn’t confirms that such an overhaul requires the time and patience Trump and Co. haven’t been willing — or able — to spare. What we saw these past several weeks, meanwhile, was a frantic race to pass something virtually no one recognized as a workable piece of legislation, and which the Senate would probably reject. “Back in 2010, when then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said that Obamacare had to be passed so that we could find out what was in the bill, Republicans guffawed — and never let her forget it. At least, one observes, the Democrats had a bill. GOP legislators have been racing to pass something that isn’t fully written yet. “While Democrats [in constructing Obamacare] solicited input from experts in the medical, pharmaceutical and insurance industries, Republicans have spent most of their time fighting among themselves. The resulting bill was a patchwork of margin scribbles and crossouts, even including instructions to the Senate to figure out ways to make certain parts work. “Once the deadline for voting passed, Trump began acting like a child who didn’t get to have his birthday party on the precise day of his miraculous delivery into the glare. Forget it. I don’t even want a party now. “The truth is, many Republicans never seriously thought Obamacare could be repealed and replaced, probably for the good reason that it’s nearly impossible to do. The most sensible solution was to fix what was already in place until the inevitable day, coming soon, when we become a dual health care system: single-payer for the majority of Americans and concierge health care for the wealthy. It’s just a matter of time.” At the Washington Post, E.J. Dionne, Jr had more of the same to pile on. “There are many reasons the Republicans’ health proposal failed (beyond the fact that it was an awful mess of a bill). They include Trump’s breathtaking contempt for policymaking ... Trump once again revealed himself to be a fraud who really doesn’t care about the lives of those who voted for him. As recently as January, he said in an interview with the Washington Post: ‘We’re going to have insurance for everybody. There was a philosophy in some circles that if you can’t pay for it, you don’t get it. That’s not going to happen with us.’ But then Trump fought for a bill that would have done just what he said he wouldn’t by throwing 24 million Americans off health insurance. [Evidently, he didn’t even look at the bill to see if it would, as he promised, provide insurance for everybody. What towering cynicism.—RCH] “This is Ryan’s mess, too. He was equally unconcerned about the suffering his bill might create. He thought he could slap together old ideas pulled off the GOP policy shelf and not face any pushback from his colleagues. “And there was the inspiring citizen mobilization that forced Republican legislators to confront the reality that millions of Americans have benefitted from a law that Ryan, Trump and company, with a stunning indifference to fact, falsely insist is a failure. Trump’s opponents learned that they can win. This will only energize them more. “But the bill’s collapse was, finally, testimony to the emptiness of conservative ideology,” Dionne said. And no Pachyderm proved itself emptier than the so-called “Freedom Caucus,” which met every concession they were granted with a new set of demands that made the legislation increasingly unpassable. “The House Freedom Caucus has made itself irrelevant,” wrote columnist Marc A. Thiesssen. Dionne continued his analysis: “Democrats can celebrate, but they cannot be complacent. They will have to expose and fight any efforts by the Trump administration to sabotage the Affordable Care Act through regulation. They should propose a package of improvements to make the ACA work better and dare Trump — and the dozen or so non-right-wing Republicans who helped block the Trump-Ryan bill — to join them. “But above all, the GOP needs an appointment with its conscience. In every other wealthy democracy, conservative parties think it’s heartless to leave any of their citizens without health insurance. Do Republicans really want to be the meanest conservatives in the world?” The Denver Post editorial began by noting that the week of the debacle was not a good week for Trumpery. The week began “with the directors from the FBI and the NSA stating in congressional testimony that Trump can’t be trusted regarding his claims that President Barack Obama illegally had his phones tapped.” And: “Federal investigations into Trump campaign contacts with Russian officials continue.” And: “Neither of Trump’s Muslim bans made it through the courts.” Still, Trump was uncowed and unbowed: after all, he had asserted on the campaign trail that he alone could fix the nation’s problems, and he ranked repealing and replacing Obamacare a top priority. “But as the world watched last Friday, Trump’s strongman approach to reforming Obamacare failed spectacularly, even in the now Republican-controlled Washington, where House Republicans had been waiting for seven years to do the deed. “This was so much more than a bad beating for Trump and for the Grand Old Party. This was an epic, self-inflicted humiliation for the new president and an enormously costly setback for Republicans. There is no other way to view the collapse. ... “The irony is supreme. For seven years now, the narrative from the hard right has been that passage of the Affordable Care Act represented the pinnacle of runaway government overreach that must be neutered and tamed. The ACA fueled the Tea Party rebellion that led to a Trump presidency. During that time, House Republicans voted to repeal the ACA more than 60 times. “Yet somehow, the Republicans didn’t actually have a plan the party could rally behind. And, somehow, Trump wasn’t keen enough to realize the one thing that the hardliners in his party won’t do is say ‘yes’ to anything they don’t fully agree with.” Fully. Every jot and tittle. No compromising. “If Trump the dealmaker hopes to have much success with his ambitious agenda,” Dionne continued, “he will need to ... finally admit, at least to himself, that he needs to start acting presidential and learn — no matter how much he dislikes it — how Washington works. “Now Trump’s enemies are emboldened. For much of the early days of his young presidency, Trump still enjoyed the element of surprise. There was a power in the cloud of confusion he created by trying to rush through big changes. That fog is lifting now. If Trump wants to right the ship, he ought to look within.”

STRANGELY,

given the provocation, cartoons on this shameful GOP maladroitness were slow in

coming. Perhaps the Republicon failure was so astounding that everyone’s breath

was taken away and their pens dried up. More likely, the disaster’s occurring

on a Friday helped delay a predictable uproar: most editoonists draw their

weekend cartoon for the Sunday paper on Friday, and Trump and Ryan didn’t pull

the bill until late in the day, after those cartoons had gone into

production—and the cartoonists had gone home for the weekend. By the time they

were back at their drawingboards, the next cartoon they’d draw would be for

Tuesday’s papers. I’m typing this on Wednesday, and not many cartoons of ire

have appeared yet. But a few brave souls recovered enough to be suitably

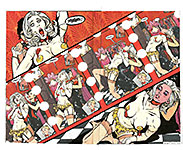

caustic. Clay Bennett gets us started at the upper left with a devastating image revealing the cause of the failure to pass the legislation: the cutting edge of the repeal movement fell off at the last moment. The GOP (the Grand Old Party) disappeared. Next, Nick Anderson resorts to a typographic device that may have been used elsewhere in the wake of the catastrophe, but it is no less telling. And, deliciously, it labels the Trumpet with his own most belittling tag. Nate Beeler’s metaphor captures the shameless arrogance of the Trumpet. The plane is going down in flames, but instead of taking some of the blame for the calamity, Donalt Rump simply ignores it as if he has no accountability, turns his back on whatever is transpiring, and moves on to the next thing. That wall, perhaps. And then Rob Rogers offers another, somewhat more devasting, image of how the Trumpet and the GOP are reacting to the bomb that just went off. And with that, we leave the health care fiasco and turn to other evidence of how the Trumpet’s first month in office went. Derisive

portraits continue to show up on our next visual aid. Jack Ohman offers laughable imagery of the paranoid Trumpet, confiding in Steve Bannon about some wholly imaginary characters that he thinks are following him. Bannon is the subject of the final portrait on the page—an excellent image by an accomplished caricaturist whose name, alas, I neglected to record. He’ll doubtless show up again in the magazine from which I clipped this picture, and when he does, I’ll jot his name down so I can correct my lapse here. (I also failed to record the names of the perpetrators of two of the four covers; drat. Sorry.) The

Trumpet’s relentless tweeting is the topic of the next few editoons. Finally, Clay Bennett shifts the subject to the other great preoccupation of recent weeks—the Trumpet’s possible allegiance to or collusion with the Kremlin, deploying the lengthy red tie with emblematic effect. Red is the color of Communism, remember?—the Russia of yesteryear? Which brings us, circuitously—incidentally— to the Senate confirmation hearings on Trump’s nominee for the Supreme Court, Judge Neil Gorsuch, a Coloradan. Colorado’s Democrat governor, John Hickenlooper, opined the other day that Democrat senators would be justified in blocking or delaying the appointment of Gorsuch in retaliation for the Republicons’ refusal to give Bronco Bama’s nominee, Merrick Garland, a hearing. But it wouldn’t be simple revenge. The GOP stance was that the appointment of a new justice should await the election of a new Prez in order that the American people would have a say in the matter. (By this reasoning, no SCOTUS appointment would be confirmed until after the next presidential election, a clear perversion of the meaning of the Constitution.) Following a kindred line of thought, confirmation of Trump’s nominee should await the outcome of the investigation of Trump’s possible ties to Russia. Said Hickenlooper: “We’re already beginning to hear people say, ‘Hey, if this is a legitimate cloud about the legitimacy of this president, should he be appointing the next Supreme Court until we get this resolved?’ Somehow it was okay to wait ten-and-a-half months without having a candidate stand for the Supreme Court. Maybe we should wait another four or five months and see what this investigation proves.” Now, back to our regularly scheduled appreciation of the art of editorial cartooning, which we resume forthwith.

TRUMP’S

UNFLAGGING EGOTISTICAL INTEREST in the news media’s coverage of him is suitably

conveyed in Jim Morin’s cartoon at the upper left of our next

exhibit—with a picture of a Trump-approved newspaper front page. But the big news of the last couple weeks is about (a) the new Republicon health care concoction and (b) the Trumpet’s budget. Our opening gambit a few paragraphs ago exposed the folly and ineptitude of the GOP effort to bring the former into being. Here, we’ll look back a little further to the editoons that contemplated Ryancare on the precipice, before it went down to ignominious defeat. Our

next display takes up (a), beginning with Lisa Benson at the upper left. Next around the clock, Matt Davies reports on the alleged “paid” town hall protesters that confronted GOP congresspersons whenever they held town hall meetings. In Davies’ view, the only paid participant in these meetings is the congressperson. Next, Nate Beeler provides a visual metaphor for what happened to the Pachyderm when the bipartisan Congressional Budget Office examined the GOP replacement plan, which would result in 24 million people losing their health insurance coverage: 14 million the result of freeing Americans from the despised individual mandate so they could choose not to buy insurance; but the remaining 10 million are likely to be poor and elderly people who will suffer when the proposed caps on Medicaid go into effect in 2020. Dubbed Ryancare (after its chief architect, House Speaker Paul Ryan, a devotee of Ayn Rand, the “virtue of selfishness” guru), the GOP plan most benefits the young and middle-income urban elites but, saith Eric Levitz in NYMag.com, “hammers the older, rural working-class voters who backed Trump.” Ryancare uses tax credits to ease the insurance premium burden, but the perennial problem with tax credits is that to avail yourself of them, you must pay income taxes, and those most in need of this kind of assistance are the poor and the elderly, whose incomes are so low they do not pay income taxes. Hence, a solution that’s no solution. It’s all GOP window-dressing. According to the Wall Street Journal, “in Nebraska’s Chase County, a 62-year-old currently earning about $18,000 a year could pay nearly $20,000 annually to get health insurance coverage under Ryancare.” The New York Times estimated that an average 64-year-old earning $26,500 a year would have to shell out $14,600 under the GOP plan, up from $1,700 under Obamacare. Once this kind of analysis emerged in evaluating Ryancare, the gutless Republicons retreated post-haste from their own plan, as Scott Stantis so vividly visualizes at the lower left, bringing about the aforementioned ignominious defeat. In

our next visual aid, Nate Beeler offers a hugely amusing image showing

how badly the GOP has managed a replacement plan after 7 years of

practice. Trump’s budget shows a ready inclination to inflict kindred cruelties upon the poor and vulnerable. Funding for Meals on Wheels is to be cut because the program shows no results. (!!! Does that mean those served by the program didn’t eat?) Herewith, another of my compulsivse rants begins. To skip to editoons, just scroll down to the next paragraph that begins ALL CAPS. President Trump doesn’t want to spend federal dollars on after-school programs, meals for poor people, or heating assistance that helps keep folks alive. But he has no problem wasting more than $3 million a pop to spend weekends at his private Mar-a-Lago club in Florida. Trump has already made four trips there since becoming president on January 20, and he recently confirmed that he’s headed there for a fifth weekend. The Trumpet’s weekend trips to his Mar-a-Lago resort in Palm Beach, Florida probably cost taxpayers more than $3 million each according to Politico. The estimate is based on a 2016 Government Accountability Office report detailing a similar three-day trip by former President Obama in 2013. During the trip, Obama left Washington for Chicago and later flew to Palm Beach, Fla. The report pegged the cost of that getaway at about $3.6 million. (But Obama didn’t do it every weekend.) About $770,000 of that cost was borne by the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees the Secret Service, while the other $2.8 million was billed to the Defense Department, primarily for the use of Air Force One and its accompanying support. CNBC says that the Trump family's costs go well beyond the Mar-a-Lago trips. Police officials estimate that they spend $500,000 a day on security for Trump Tower in New York, where first lady Melania Trump and son Barron live. (Recently, a petition has begun to circulate demanding that Melania move to the White House to save money.) The Secret Service also protects Trump's eldest sons Donald Jr. and Eric when they travel for Trump Organization business. The Washington Post reported that Secret Service and U.S. Embassy officials paid almost $100,000 for hotel rooms when Eric Trump went to Uruguay to promote a Trump-branded property. Despite vowing during his campaign that he “would rarely leave the White House because there’s so much work to be done” and “would not be a president who took vacations” because “you don’t have time to take time off,” Trump has visited Trump-branded properties eight of his first nine weekends as Prez according to a report from Medium Daily Digest. Trump’s repeated trips to Trump-branded properties aren’t just problematic because they embody how he’s profiting off the presidency and breaking campaign promises (his Secret Service entourage pays for the rooms it occupies; one of his campaign promises was that he wouldn’t take vacations but would stay in the White House and work). They also represent Trump’s selective austerity when it comes to spending taxpayer dollars. As Quartz reported recently, after the sixth weekend, Trump will have already spent about $16.5 million on trips to Mar-a-Lago. For that amount, Meals on Wheels could feed 5,967 seniors for a year and after school programs could feed 114,583 children for a year. Office of Management and Budget director Mick Mulvaney defended the draconian cuts included in the Trump administration’s proposed budget by arguing that the federal government can’t ask “a coal miner in West Virginia or a single mom in Detroit to pay for” programs like the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. But one wonders whether those struggling Americans would rather have public radio or dole out their share of the $3.3 million a self-proclaimed billionaire is spending each weekend to mingle with his ludicrously wealthy club members down in Florida.

THE BUDGET Trump sent to Congress shifts the nation’s financial resources from helping those at home who are in need and fostering friendships abroad to improving our ability to make war, and Jeff Danziger’s image adroitly depicts the situation with War stuffing himself with the Trump budget money. At the lower left, David Fitzsimmons offers a comment on the Republicons’ foot-dragging in initiating an investigation into the Trump-Russia connection. Perhaps not so vivid a visual as some we’ve looked at this time, but Fitz’s style is worth a look anytime—and his caricatures of the congressional leaders are wonderfully deft. But

let us not leave our gallery of past fumbles and stumbles without taking a

moment to smile. But the alternative does not make you popular—as all the little Trumpeteers now can attest.

GOLDEN TRUMPET

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS The number of hate groups in the U.S. rose for a second year in a row in 2016 as the radical right was energized by the candidacy of the Trumpet according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. The most dramatic growth was the near-tripling of anti-Muslim hate groups—from 34 in 2015 to 101 last year. The growth has been accompanied by a rash of crimes targeting Muslims, including an arson that destroyed a mosque in Victoria,Texas, just hours after the Trump administration announced an executive order suspending entrance to the U.S. by travelers from some predominantly Muslim countries. The hate group increase was fueled by Trump’s incendiary rhetoric, including his campaign pledge to bar Muslims from entering the United States, and anger over terrorist attacks such as the June massacre of 49 people at a gay nightclub in Orlando.—From the SPLC Report, Spring 2017