|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 356 (August 20, 2016). Back to the old Rabbit Habit routine. Open Access Month is over, and the doors at Rancid Raves have slammed shut again except for $ubscribers. (But if you liked what you saw over the last month, consider joining us as a $ubscriber for a paltry $3.95/quarter after an initial $3.95 introductory month fee.) On the other side of the barricade, we report the first interview in the West with Iran’s Atena since her release and why Frank Cho quit his DC project drawing alternate covers for Wonder Woman. We round up some of the editoons committed during the politically fraught July and we review Adam Hughes’ Betty & Veronica, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s Mycroft Holmes, Garrett Price’s unique White Boy, and a clutch of barenekkidwimmin comic books, one of which veers off into sadistic eroticism . We ponder cartooning at The New Yorker and deliver our final report on attending the San Diego Comic-Con (this one’ll be my last one). And we explain why superheroines won’t work in a politically correct environment. We also bid farewell to cartooning giant Jack Davis and the antic cartooning talent Richard Thompson. This posting, you’ll see, is huge. We just can’t shut up. But that’s what it’s all about, eh? Talking about comics. That’s what we do here. But every time we get ready to post, the Trumpet blasts a new outrage and editoonists leap to their drawingboards, and we have even more to say. So we admit: there’s more here than can be read at a single sitting. We recommend using the contents listed below as a shopping list: scan the items listed and pick those that interest you; then scroll rapidly down to the ones you’ve picked, skipping over boring stuff. Politics and editooning spirals nearly out-of-control this time because of the political conventions and the Prez Election shenanigans; but if you’re not into politics, skip all that and go on to what you like Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Iran’s Atena Interviewed LA Times Wants $300,000 in Advance Fees from Ted Rall Frank Cho Quits DC Comics Pearls Yanked Because of ISIS Joke Ramirez Finds Work Captain America Statue Not Welcome in Brooklyn Superheroines and Violence Politically Incorrect Joe Giella Retires from Mary Worth

REPORT ON MY LAST SANDY EGGO CON Sergio Gets Icon Award David Siegel Gets Alter Ego Cover Story FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Adam Hughes’ Betty & Veronica Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s Mycroft Holmes Black Hammer Barenekkidwimmin and Sadistic Comics

EDITOONERY The Political Conventions Presidential Campaign Trump and Hillary —July Was a Fun Month

Cutting Off Trump’s Tweeter Explaining the Trumpster Trumpster Dumpster: What’s In a Name?

THE FROTH ESTATE Journalism Fails —And Succeeds at Time’s 240 Issue

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL What’s Happenin’ On the Funnies Pages

BOOK MARQUEE Masters of American Illustration — including some cartoonists Garrett Price’s White Boy in Skull Valley

Jules Feiffer’s Next Graphic Novel

A-GAGGING WE GO Magazine Cartooning at The New Yorker Michael Crawford’s Puzzler Unpuzzled

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY

PASSIN’ THROUGH— Richard Thompson Jack Davis (With an Aside for Aussie Jim Russell)

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

IRANIAN ARTIST SPEAKS TO THE WEST Maren Williams at the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund provides an introduction (in italics) to the interview Atena Farghadani gave in mid-July to the Washington Post’s Michael Cavna—: Just over two months ago, Iranian artist and activist Atena Farghadani was freed from prison after her draconian prison sentence of 12 years and 9 months for mocking her country’s parliament in a cartoon was shortened to the 18 months she’d already served. (See Opus 355 for a succinct recitation of her story.—RCH) Evin Prison, the Tehran lockup where Farghadani spent most of her incarceration, is almost invariably described in Western media as “notorious.” But in fact, she tells Cavna that the women’s prison at Gharchak where she was initially detained is even worse. It was there that she went on a prolonged hunger strike which resulted in cardiac arrest before she was moved to Evin. Last month, she gave an exclusive interview to Cavna about her time in prison, her plans for the future, and her conviction that she is obligated to keep making art in Iran, no matter the consequences. Here’s Cavna—:

OF THE THOUSANDS of artists I have interviewed over the years, few have been as demonstrably brave as Atena Farghadani. Today, Atena vows to continue to make political art from within Iran, where her voice may have the greatest effect. This is an exclusive Q&A with Ms. Farghadani, in her first interview with the Western press since winning her release. The interview was conducted via email with the help of Nikahang Kowsar, the Iranian-born cartoonist and board member of the Washington-based Cartoonists Rights Network International, who himself was jailed in Iran in 2000 for his art. This interview has been edited for clarity and length. MICHAEL CAVNA: First off, Ms. Farghadani, let me just say, now that the opportunity finally provides: congratulations on your freedom. We heard reports about the difficult conditions while you were imprisoned. How are you feeling, and doing? And how does one even recover from a mental and physical ordeal such as yours? ATENA FARGHADANI: I appreciate all the efforts you and your colleagues have made so far. My feelings at the moment are not very pleasant because it’s like I’m stuck in a limbo. Obviously, the mental weariness of imprisonment is more serious than the physical problems caused by it. At the moment, since I’ve arrived at the certainty that there is miracle lying in the art of drawing and painting, I’m more determined to continue doing it than ever. MC: You, of course, have become an inspiration to so many around the world, Atena — a beacon of creative and political resistance. While you were in prison — Evin and elsewhere — how aware were of you of the degree to which the outside world knew and was following your story? Was Mohammad Moghimi [her lawyer] able to provide you with news in that regard during your case? AF: When I was in prison, I wasn’t aware of outside events and the news about me, especially in 2015, when I was on a hunger strike in the gruesome Gharchak prison. At that point, I was absolutely hopeless and thought I would die there, without my voice ever being heard. But I kept going with the strike, constantly thinking that even if I die, I have a clear conscience for I’ve died for my beliefs and goals. After my appeal to be transferred to Evin prison was approved and I ended my hunger strike, my attorney, Mr. Moghimi, gave me all news in two very short visits, boosting my morale and giving me hope. MC: One aspect of the ordeal of being in an Iranian prison was not knowing one’s fate — feeling as though you are in the legal hands of a system that might not practice justice as you, the prisoner, might understand it, and all the uncertainty. Could you talk about what was hardest for you about your long detentions and imprisonment — and whether you thought you might actually spend more than 13 years behind bars for your outspokenness and artwork? AF: When I heard my sentence of 12 years and nine months imprisonment, I thought it was unbelievable and very unjust. Since I was 29 at the time, I calculated that I’d have to be in prison till I’m 42. At first, I had a hard time accepting the sentence, but then I thought I could use this time, as much as possible, to draw and have an opportunity to put an exhibition of my works after my release. I considered prison my home for the next 13 years. My family could not accept this new attitude of mine towards prison and my beliefs, and at times they were frightened by it and wept. At these times, I had no choice but to make faces for them from behind the glass in the visitation cabin to make them laugh. These were the hardest and most bitter days I had during my incarceration. MC: Why do you think you were ultimately awarded your freedom? What swayed the legal system? AF: As the results of the efforts made by my family and my attorney, Mr. Moghimi, and pressures from the international community and human rights organizations, my sentence was reduced from 12 years and nine months to 18 months and a three-year suspended sentence for insulting the supreme leader of Iran. I am grateful to all those whom I don’t know and to whom I owe my freedom. MC: Is there anything about your case [including the reported “virginity test" after shaking your male attorney’s hand] that we should know about that we might not know? AF: Yes, that’s … caused lots of confusion: Considering the fact that my family had refuted that I was tested for virginity and pregnancy because of shaking hands with my lawyer, people wanted to know the truth. The truth is that my family was in denial at the time because of the dominant traditions and the Iranian culture and fear for more pressure from the judiciary on me. But the tests were actually made, which led to my three-day dry hunger strike in objection. The Islamic Republic of Iran later confirmed this event. It is noteworthy that both my attorney and I were exonerated from the adultery accusations and I owe this to the judge of this specific case, who issued our exoneration verdict independently and neutrally in spite of the sensitivity of the case and security pressures. MC: What art are you making now — and will your art remain political, or might you steer your art and activism in a different direction? AF: Right now, I’m painting and making a collection of artwork with political and social contents, and I intend to have an exhibition within a year, but I’m afraid I can’t hold this exhibition in Iran, and thus I’m even thinking of having a street gallery, though it wouldn’t be without consequences. I believe that “criticism” serves art. So, I have decided to use my art to challenge social issues as I have done before, like the cartoon I drew after I was released as an objection to the dean of Al-Zahra University, who expelled me and many other students. [See Opus 355.] MC: Do you feel safe now in Iran, and can you see ever coming to visit America? AF: Of course, I could be more successful in developed countries, but when I witness the problems Iranians are dealing with, such as economic and cultural poverty and various limitations, I cannot leave them alone to live in another country in a better situation, despite all the constraints and issues I would possibly face. Many Iranians, though, have had to leave their homeland because of these constraints and have been active outside their country to improve human rights in Iran and are successful, too. But I don’t see it in me to be able to leave my country because of my emotional attachments, which is perhaps a weakness of mine, but as long as I live, I will stay here, even if I have to go to prison again. MC: Are you comfortable with being a symbol for artistic resistance and political freedom of expression? AF: I don’t consider myself a symbol. I simply acted on my thought, beliefs and principles, and I think all people have an individual and social task to fulfill. MC: Is there something I didn’t ask that you would especially like to tell readers? AF: Yes. One of the things that has had [a] destructive impact on me after my release was the incarceration in the gruesome Gharchak prison, which is for prisoners with all sorts of non-security crimes. What bothered me the most was to see inmates — many of whom were victims of the economic and cultural poverty in the Iranian system — who were not treated like human beings; their most basic rights were violated. I consider Gharchak prison as a graveyard of time … where time dies. I sometimes see those inmates in my nightmares. Once, I saw one of them collecting and braiding my fallen hair! I see myself as a reflection of other people, and to respond to this question of yours, I would like to reflect the wishes of other women imprisoned in Gharchak — most of them longed for cool drinking water, instead of the salty lukewarm water they had to drink from the tap. There were only four showers in each chamber for 189 inmates, with the same salty water for only an hour a day, so many of them missed a hot shower! Many of them [condemned to] death sentences wished to plant something that wouldn’t wither from the salty water and [to] see that plant — to leave a living mark before departing from this life.

ADDING INSULT TO INJURY Editoonist Ted Rall is currently suing the Los Angeles Times for defamation, blacklisting, wrongful termination and breach of contract; see Opus 350 for details. According to a press release from Rall’s attorneys, Shegerian & Associates, Inc., a Santa Monica-based litigation law firm specializing in employee rights, the newspaper’s initial response to Rall’s suit is its demand that Rall pay in advance $300,000 in “legal fees” to guarantee the Times’ attorney fees in the event they should win their anti-SLAPP motion. S&A characterized this maneuver as a “bully move against a freelance cartoonist by a corporation that is egregiously inverting the very anti-SLAPP statute designed to protect employees from big corporations.” The court has since ordered the Times to lower its request to $75,000. Said Rall: “It feels almost like they are forcing me to ‘pay to play’ if I am to see my day in court. You’d think after what happened, they would be issuing an apology and offering me my job back, not trying to bankrupt me after wrongfully firing me.” Rall was originally hired by the Times as an editorial cartoonist in 2009 and published approximately 300 of his cartoons and more than 60 of his blog posts in the paper between 2009 and 2015. At no time during his employment was Rall disciplined or written-up and he was consistently praised for his work. Then in the summer of 2015, Rall was summarily and publicly fired by the paper, which alleged that in a blog that May, Rall had posted untruths about his run-in with the Los Angeles police. Said S&A: “The Times' suspicions about the veracity of Mr. Rall’s blog post were unfounded in that they failed to properly investigate the accusations and refused to acknowledge proof that Mr. Rall’s blog post was, in fact, accurate. The public defamation and subsequent blacklisting of our client following blatantly wrongful termination should be enough of a slap in Mr. Rall’s face, but the demand now for this freelance cartoonist to pay the Times’ legal fees in advance of a trial demonstrates that not only does the LA Times not play by its own rules employment-wise, as we will demonstrate in court, it behaves in a vindictive and unfair manner as well.” The story of Rall’s adventure with the Times is detailed at Opus 342a.

CHO QUITS DC OVER ATTEMPTED CENSORING OF HIS WORK New Creation in the Wings Famed limner of the curvaceous gender Frank Cho made it through only six of the 24 Wonder Woman covers DC Comics had commissioned him to draw before he quit, fed up with would-be art critics and censors. In a statement to Bleeding Cool, he wrote (in italics): All the problem lies with Greg Rucka [Wonder Woman writer]. EVERYONE loves my Wonder Woman covers and wants me to stay. Greg Rucka is the ONLY one who has any problem with covers. Greg Rucka has been trying to alter and censor my artwork since day one. Greg Rucka thought my Wonder Woman No.3 cover was vulgar and showed too much skin, and has been spearheading censorship, which is baffling since my Wonder Woman image is on model and shows the same amount of skin as the interior art, and it’s a VARIANT COVER, and he should have no editorial control over it. (But he does. WTF?!!!) I tried to play nice, not rock the boat and do my best on the covers, but Greg’s weird political agenda against me and my art has made that job impossible. Wonder Woman was the ONLY reason I came over to DC Comics. To DC’s credit, especially [Art Director] Mark Chiarello, they have been very accommodating. But they are caught between a rock and a hard place. “Cho’s no stranger to cover art controversy,” said Jessica Lachenal at themarysue.com. “—he’s been at the center of more than a few firestorms regarding the overtly sexualized covers that he draws of female comic book heroes. In one particularly egregious example, his ‘sexy cover’ of Spider-Gwen is especially skeezy because, well, she’s a teenager, but there she is, sexualized anyway.” “It was a parody,” Cho said during the brouhaha over Spider-Gwen [see Opus 339]. “I was aping the infamous Manara Spider-Woman pose that sent some of the hypersensitive people into a tizzy.” Cho was pursued by bloggers seeking interviews, but he didn’t bite. “Instead

of me wasting my breath and precious time by replying to non-issue, I’ve drawn

another cover sketch in a response that will, hopefully, answer all the

questions. Enjoy, everyone.” “That aside,” Lachenal resumed, “Cho’s drawn more than a few other cheesecake pieces, some of which [like the second sketch of Spider-Gwen] feel like very pointed jabs at folks who ‘overreact’ to such pieces. The Wonder Woman art in question hasn’t been released, and after this controversy, it doesn’t seem likely that it will be.” Bleeding Cool reached out to Cho and Rucka for comments, but so far, only Cho has responded, to wit (in italics)—: Since you’re asking me a straight question, I’m going to answer honestly as possible from my point of view. Wonder Woman was my dream job at DC Comics. I love and respect the character very much. When I was invited by DC to draw the 24 variant covers for Wonder Woman, I was ecstatic. I was told that I had complete freedom on the variant covers and the only person in charge of me was the senior art director, Mark Chiarello, who I greatly respect. Win-win for everyone. Now the variant covers are handled by entirely separate editorial office than the rest of the books. I was given assurance that I would not have to deal with the Wonder Woman book writer or editor at all, and was told I would only be dealing with Mark Chiarello. So I came onboard and started working right away. Everything went smoothly at first. I turned in my first batch of cover sketches and Chiarello approved them, and I started finishing and inking them ASAP since these were biweekly covers and we had limited time. Then Chiarello started getting art notes from Greg Rucka ordering him to tell me to alter and change things on the covers. (Remove arm band, make the skirt longer and wider to cover her up, showing too much skin, add the lasso here, etc.) Well, Chiarello and I were baffled and annoyed by Greg Rucka’s art change orders. More so, since the interior pages were showing the same amount or more skin than my variant covers. (For example: Issue No.2, panel one, etc.) I requested that Greg Rucka back off and let me do my variant covers in peace. After all, these were minor and subjective changes. And let’s face it, being told by a non-artistic freelancer what I can and cannot draw didn’t sit too well with me. Then things got ugly. Apparently unbeknownst to Chiarello and me, DC, for whatever reason, gave Greg Rucka complete and total editorial control on Wonder Woman including variant covers by contract. My promises of creative freedom were verbal. I think this is a case of complete miscommunication and things falling through the crack during the post-DC headquarters move to Los Angeles. Had I’ve known Greg Rucka had complete editorial control over the variant covers, I would have never came onboard Wonder Woman. Since we were on the same team with the same goal – making great Wonder Woman comics— Mark Chiarello and I tried to reason with Greg Rucka to back off and let me do the variant covers in peace. But Rucka refused and tried to hammer me in line. Things escalated and got toxic very fast. The act of a freelance writer art-directing me, overruling my senior art director, altering my artwork without consent was too much. I realized after Rucka’s problems with my Wonder Woman No.3 variant cover, my excitement and desire for the project had completely disappeared, and I decided to bow out quietly after I finish my Wonder Woman No.4 variant cover. (This was around end of May.) But DC wanted me to stay and finish out Nos.5 and 6 covers to give them some time to find my replacement.

CHO HAS MORE than Wonder Woman to occupy him. In a month or so, Cho’s solo comic book enterprise, Skybourne, debuts. In July Previews, Cho, responding to questions, described the new venture: “The Skybourne story is something I thought of over ten years ago. It’s the story of Thomas Skybourne, an immortal tired of his everlasting life, who goes on a search for a mystic weapon, Excalibur, that could kill him. In the opening sequence, Skybourne is seen falling from the sky (he jumped out of a plane without a parachute), his latest attempt at ending his life. So the name Skybourne has a double meaning: it describes his divine origin and the opening scene of the story. ... The whole series is a cross between Indiana Jones and Highlander. ... This is one of the few stories I’ve written that has a concrete beginning and end. This story came to me fully formed. And it’s also one of the most cinematic stories I’ve envisioned.

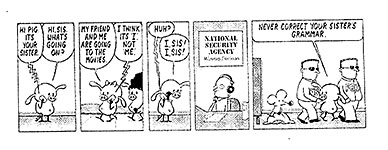

ISIS ON THE FRONT PAGES —BUT NOT IN THE FUNNIES Stephan Pastis

has made a cottage industry out of trying to see how far he can go in making

jokes about topics that the hyper-sensitive daily press deems “offensive.” And

he gets away with it more often than not. Almost always, in fact. Until July

27, when his syndicate pulled the strip you see nearby. “The strip’s humor results from a clever pun,” explained Josh Zuckerman at the National Coalition Against Censorship: “Pig is not, in fact, yelling ‘ISIS’—thus [the strip in which he is arrested is] mocking inept government officials. The strip can also reasonably be interpreted as a work of political protest and a condemnation of perceived violations of Fourth Amendment Rights.” Pastis told Zuckerman that the strip “seems harmless to me, but I guess these are sensitive times.” His Facebook post on the issue was less apologetic. “As you will see,” he wrote, “it’s not offensive at all. At least not to me.” Odd—astounding, in fact—that a newspaper syndicate censored the strip simply because it uses the name of a terrorist organization that undoubtedly appears in print each day in every newspaper in the nation. Pastis, who told Katy Waldman at slate.com that he’s never had a re-run in 15 years, files completed strips weeks or months ahead of their publication date. As a rule, Pastis’ syndicate doesn’t censor him. Typically, if he does a questionable joke, a syndicate factotum cautions him about it but doesn’t demand that he withdraw the potentially offensive strip or rework it. “After he submitted the ISIS strip,” Waldman said, “a representative of his syndicate contacted him to warn that if some kind of terrorist event occurred on or near the day that the strip was slated to appear, he’d become a ‘lightning rod for readers’ anger and sadness.’” Working in this environment, Pastis envies Web cartoonists for their freedom. “I wish I could have a fraction of the edginess of the online guys,” he admitted. “Internet writers don’t realize how extraordinarily tame newspapers can be. You reference Lincoln’s assassination, and readers shout, ‘Too soon!’ It’s a different world, and it’s inhabited by your parents and grandparents.” Univesal Uclick’s John Glynn confirmed to Waldman that “there’s lots of sensitivity—the strip would have caused serious problems if it had been coupled with a terrorist event.” Though Universal has never outright rejected a Pearls strip, the syndicate has sent advisory notes back to Pastis to remind him of newspapers tendency to shy away from themes of “drugs, drinking, sex—for lack of a better word, anything beyond PG-13,” Glynn said. Well, okay. But in our Newspaper Vigil department, we’ve highlighted Pastis’s strips that tred on all those sensitive toes. Rat, f’instance, is a regular beer drinker and does nothing to hide his addiction. So Pastis evidently plunges ahead, despite syndicate warnings. Still, comic strips are ticking bombs, waiting to offend someone. Speaking to the Columbia Journalism Review, author of The Art of Controversy: Political Cartoons and Their Enduring Power, Victor Navasky says that a comic strip can provoke particular ire because “it’s a form of public humiliation, and people receive it differently than they receive words.” The CJR continues—: “At least some of the ire stems from the visual nature of the medium, which makes cartoons both striking and accessible. They sow discomfort for subjects and their followers, with no recourse for the aggrieved, Navasky says. ‘The response to these things is disproportionate.’” Pastis, however, is not interested in fighting his editors’ decisions. “That’s how it works,” he told Waldman. “What I think is great is how this story has taken off on Twitter, how it’s generating discussion and allowing the online world to see what the world of traditional media is all about.” After all, “this was simply one of my dumb plays on words,” Pastis added. “I wasn’t trying to say anything more. I heard the words and realized I could make a pun.” Okay. This is all very plausible and sane, said Waldman. But could it be that Universal Uclick bagged the strip because it’s not, well … because it, ah, it, you know, it’s not … Did they kill the strip because it’s not funny? She asked Glynn. The syndicate does not monitor comics for quality, Glynn insisted. “We’re too busy.” Really? You can tell us. “Yes, really.” Off the record? “We’re too busy saying how good they are.”

RAMIREZ FINDS WORK Michael Ramirez, a Pulitzer-wining (twice) conservative editoonist who was laid off last spring when his newspaper, the Investor’s Business Daily, went weekly, has been hired by the Daily Signal to produce an exclusive cartoon each week with a conservative perspective on the hottest issues affecting the lives of Americans. Before joining the Investor’s Business Daily, Ramirez produced edgy conservative cartoons for Los Angeles Times. “As a constitutional conservative, my editorial cartoons are a good fit for the Daily Signal,” Ramirez said in an email, quoted by Ken McIntyre of the Daily Signal. Ramirez added: “We are in an industry where conservative thought and opinion are hugely outnumbered; at least, that seems to be the case in most newsrooms and presidential convention halls that I have visited. When I worked for the Los Angeles Times, it sometimes felt like I had to wear a Kevlar vest and a helmet just to walk through the newsroom, and use bomb-sniffing dogs to open my mail because I represented a vastly different point of view than [that of] my predecessor, Paul Conrad [a liberal wild man—RCH]. I think the readers of the Daily Signal will find my editorial cartoons to be a good philosophical fit.” As a senior editor at IBD, Ramirez co-managed the editorial pages of the Los Angeles-based paper for 10 years, until the publication’s daily print edition converted to weekly in May. In his email to the Daily Signal, Ramirez said: “I believe in the purpose of editorial cartoons as a persuasive means to impact the political dialogue and to be the catalyst for thought. In this crazy and confusing political climate, I think people are looking for a conservative voice of reason. I look forward to filling that void. In our current state of politics, if we can actually restore some thought into the process, that would be an achievement in itself. “There is a trend in modern editorial cartooning and in politics,” he continued, “—because of the fusion of news and entertainment—where they now substitute humorous anecdotes and jokes, the kind of ‘Tonight Show’ monologue, for serious political discussion. I am a serious journalist who uses images to convey serious and substantive messages. People are drawn to the visual medium and want real news. I hope that I can deliver substantive point of view and have an impact through the Daily Signal.” Ramirez won his first Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1994 at the Commercial Appeal in Memphis, Tennessee, after which the Los Angeles Times hired him. He won the Pulitzer again in 2008 at IBD.

CAPTAIN AMERICA NOT PARTICULARLY WELCOMED When that 1-ton, 13-foot high bronze statue of Captain America made its first stop after crossing the country following its initial appearance at the San Diego Comic Con (see Opus 355 for details), it enjoyed a somewhat luke-warm reception at Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. Installed at the Children’s Corner near the carousel to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Brooklyn-born Steve Rogers character, it provoked criticism, reported Rachel Petty at the New York Post. “Green activists say the space was designated ‘commercial free’ by the city, and Marvel’s billion-dollar franchise is as commercial as it gets.” Protesters apparently prefer “serenity” and the natural beauty of the green space to the star-spangled superhero. But, no worries: the statue will move to another location after its two-week stint in Prospect Park.

THE INHERENT CONTRADICTION IN FEMALE SUPERHEROES Among the enthusiasts for comic book superhero movies are numbered a few heedlessly carping devotees who persist in demanding a superhero movie with a superheroine headlining the feature. Lately in the Denver Post, professor (at Colorado Mesa University) Michael Conklin discussed this oddity at some length. He began by listing several female lead comic book movies from 1984 through 2005 (“Supergirl” through “Elektra”) that were failures at the box office—and among fans. None of them compared to the financial success of what he calls “the Marvel Cinematic Universe.” Marvel, he notes, “is a fairly progressive company” in terms of representing diversity: “Their current best-selling comic book features a hero of color, the Black Panther. Another major character in comics, Ms. Marvel Kamala Khan, is a Muslim-America.” And Thor is presently a woman. And “there are so many LGBT characters in Marvel Comics that you can find top 10 lists of people’s favorites.” But heroines won’t become a mainstay in movies unless they are profitable, Conklin continues. And he goes on to provide this devastating analysis—: “Ironically, a recent controversy brought on by people purporting to protect women lends support to the diminished roles for female superheroes. A billboard promoting the new X-Men movie features Jennifer Lawrence’s character, Mystique, going up against the main villain, Apocalypse. Instead of praising the advertisement for featuring a female hero, [activists] attacked [it] for portraying violence against women because the main villain is male [sort of] and Mystique is female [sort of—they’re both mutants of some kind]. “Not surprisingly, superhero movies depict violence against the hero. If movie studios are put on notice that this is unacceptable for female characters, that perpetuates the role of men as the superheroes by creating a strong incentive to instead use women in traditional, damsel-in-distress roles.” So putting female superheroes on screen will be “an even greater uphill battle if activists groups attack studios for promoting women in traditionally male roles”—which, ipso facto, will necessitate violence against women. Sigh. You can’t win.

ODDS & ADDENDA Colorado, the first state of the Cannabis Union, is introducing Willie Nelson’s brand, Willie’s Reserve, “for the first time in Colorado.” ... July was the 50th anniversary of the bikini. ... A copy of Action Comics No.1, Superman’s debut comic book, sold at auction recently for $956,000; it was CGC graded only 5.5 on a scale of 10, and was expected to sell for only about $750,000. ■ Joe Giella, veteran Silver Age comic book artist who left funnybooks to

draw the syndicated Mary Worth comic strip for the past 25 years,

retired the last week in July. The new artist on the strip is June Brigman,

who drew the last 15 years of Brenda Starr. Brigman joins writer Karen

Moy, and for the first time since 1942 (when the first artist, Dale

Connor, left the strip), Mary Worth is being drawn by a woman; for

the first time ever, the strip about one of the most enduring women in American

culture is in the hands of a nearly all-female team. Brigman’s husband, Roy

Richardson, letters, inks, colors and digitally formats the strip. “He

keeps me grounded,” said Brigman, “so I don’t think [the strip’s] going to

become a complete estrogen fiesta.” ■ Roz Chast, the New Yorker cartoonist whom the editors apparently cannot get enough of, had a two-page spread color comic strip in a recent issue of the magazine. These pages provide an Epilogue for her best-selling critically acclaimed graphic biography, Can’t We Talk About Soemething More Pleasant, about her life with her elderly and dying parents. In the two pages, Chast decides, at last, to bury the cremains of her mother and father after learning where her unnamed older sister, who died one day after being born, is buried: her parents are now buried in the same cemetery, with a view of their deceased first-born’s grave. Unlike the excerpt of the book published in The New Yorker, this two-pager reflects none of the comedic sensibility which is Chast’s stock in trade. Or so it seems to me. (Although the idea of keeping your parents’ cremains in a bag in the closet is the kind of oddity Chast revels in.) So permitting Chast to consume two pages in the magazine in order to tie up a stray thread from her story is an act of editorial generosity not judgement. ■ Whatever You Want. A catalog with the unlikely name of WhatOnEarth

offers some nifty comics-related

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FURTHER ADO Halls cough drops come individually wrapped in small scraps of paper that each bear several messages like this: A pep talk in every drop. Don’t give up on yourself. You can do it and you know it. The show must go on. And these are on just one such wrapper. Here are more from another wrapper: Don’t try harder: do harder. March forward. Keep your chin up. You got it in you. So as you medicate for a cough, you get these happy pep talks to help you on your way. Obviously, it costs to manufacture the little wrappers with printed messages. But the Halls people evidently think it’s worth it. Good for them.

SANDY EGGO ONE MORE TIME July was a coagulation of conventions this year. Two of them, the Republicon Convention and the Comic-Con Interational San Diego, overlapped; the other, the Democrat Convention, took place a week later. We’ll attend to the political shenanigans in their proper place—under the fun-loving heading Editoonery; here, we’ll say a few words about the Sandy Eggo Con. It

was, as you can tell from the adjoining visual aid, exhausting. Barring an unlikely event (like being nominated for an award), I concluded a 25-year stretch of continuous attendance with this year’s Comic-Con. No more hereafter. I’ve given various reasons at various times for ending with the 25th—it’s a nice round fittingly final number; it’s no longer as much fun as it used to be. Both are true. The fun has drained out of it over the years as the growth of Hollywood increased while the presence of comics withered unto death. But my real reason for jumping ship after 25 years of fidelity is that the hotel room rates in San Diego during the Con week are simply beyond the reach of a normally financed human being. I stayed at the Hilton Gaslamp, where rooms went for roughly $300 a night (including taxes and fees). Really? $300 for a place to sleep, go to the toilet, and shower? And who, avid Comic-Con attendees all, would spend any more time in his/her room than those perfunctory activities require? Even evening time is spent at the Con, not in one’s hotel room. Hotel room rates are out of control. Instead of offering discounted “convention rates” during the Con, hotels seem to have inflated their usual rates in order to cash in on the Con. As I explained in my report last year (Opus 342), you can get hotel rooms for $50-60/night cheaper the weeks before and after the Con. Over the years, the Comic-Con has lost whatever leverage it ever had in negotiating rates. But it doesn’t seem to matter to either Con management or those who attend. In the usual post-Con critique session on Sunday afternoon, July 24, most of those commenting complained about long lines to get into rooms featuring their favorite movie stars. No one, seemingly, is bothered by sky-high hotel room rates. And why would Con management complain? As long as it gets what it wants—people coming in droves and paying registration fees—why bother with hotel room rates? In short, nobody cares. Except me. And I’m registering my objection in the only way left to me: I’m walking away and not returning.

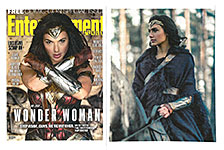

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY did its post-Con report in the August 5 issue (the one with Jeffrey Dean Morgan on its Walking Dead cover). It devoted 7 pages to the topic. Every page featured a movie or movie star. Comic books are not mentioned anywhere in the article. Not even Adam Hughes’ first issue of Betty & Veronica, which debuted during the Con. You’d think his luscious ladies would get a mention. Nope. Most of the movie stars at the Con are in movies inspired by comic books. But still—no comic books mentioned at all in EW articles about the nation’s largest convention built around comic books? You’d think U.S. House of Representatives John Lewis, the last living reminder of the Civil Rights movement, would get a mention. He was, again this year as last, leading a march through the exhibit hall, promoting the third book in his March graphic novel trilogy. At the session featuring him, Lewis said: “It doesn’t matter if you are African-American or Latino or white, if we are straight or gay. We are one people.” EW included a report on its own Con site, set up off-campus at the normally quiet harbor-side Embarcadero Marina Park South, a ten-minute walk away from the Convention Center. Admission is free—as were numerous give-aways: t-shirts, water bottles, souvenir photos and Krispy Kreme donuts. You could have your photo taken with Jabba the Hut, get a free shave (jaw or legs, depending on your gender or preference), and recharge your phone. You could make your own candy. Lines were almost non-existent. Besides the give-aways, Con-X (as it is called) featured two stages of live entertainment with music and celebrity panels. The music, necessarily loud, disturbed the normally peaceful ambiance of a walkway along the waterfront—and at sidewalk cafes, where I often repose to regain sense and sensibility. News originating at the Con abounded (albeit little of it reported in EW afterwards). A “Justice League” trailer was screened; ditto “Luke Cage,” “Iron Fist,” and “Wonder Woman.” Marvel confirmed that its “Guardians of the Galaxy” is getting its own ride at Disneyland. Ben Afleck will direct solo a Batman movie, and Brie Larison will be a star in the forthcoming “Captain Marvel” flick. I

also picked up a copy of the numerous promotional magazines being handed out

hither and yon, and based upon the cover illustration of EW’s Comic-Con

Special Issue, I’m happy to report that the star of “Wonder Woman,” Israeli

actress Gal Gadot, is more than photogenically beautiful: there’s a

discernible hard edge to her facial beauty—just what we hope to find in a

fist-swinging superheroine. It’s in her eyebrows and square jaw. Other 75th anniversaries commemorated in this program include those of Aquaman, Green Arrow, Archie, Captain America, and Plastic Man. I contributed the article about Jack Cole’s rubbery creation, a reworking and shortening of my Hindsight entry, “The Mystique and Mysteries of Jack Cole” (November 2003). Other anniversaries represented in the program were the 50ths of Conan and Frazetta, the Black Panther, Silver Surfer, John Romita’s Spider-Man, the Batman tv show, Star Trek, and 25 years of Bone, Deadpool and Palookaville.

I SPENT SEVERAL MORNING HOURS every day at the booth of the National Cartoonists Society, where I flogged my newest book, Insider Histories of Cartooning: Recalling Forgotten Famous Cartoonists and Their Comics (one of whom, by the way, is Playboy’s Hugh Hefner, who began his publication career as a cartoonist; betcha knew that, eh? but my book includes some of his alleged cartoons). I sat next to Jason Chatfield on a couple mornings. He’s moved from his native Australia to New York, but he continues to produce the Aussie favorite comic strip, Ginger Megs. Ginger Meggs is Australia's oldest and most widely syndicated comic strip, appearing daily in 120 newspapers in 34 countries. The title character, a red-haired prepubescent mischief-maker, first appeared in James Bancks’ Us Fellers strip on November 13, 1921. Within a year, Ginge (as he’s known Down Under) had emerged as the star of the show, but the strip retained its original title until 1939. When Bancks died on July 1, 1952 from a heart attack, Ron Vivian took over the strip (1953-1973), followed by Lloyd Piper (1973-1982), James Kemsley (1983-2007) and, since 2007, Chatfield. A peculiarity of the strip is a bit of wit or wisdom wholly irrelevant to the action at hand, lettered sideways into a panel. This tradition began with Kemsley, who told me it started one day as a message to some friends of his: he knew he’d be late to the cricket match later that day, so he warned his teammates with a note in the strip. Readers were fascinated by this mysterious seemingly irrelevant communique, so Kemsley continued by making up “sayings” and citing famous quotations for years thereafter. Chatfield

is currently celebrating the strip’s 95th year by imitating Bancks’

style in the Sunday strips. Nearby are samples of Chatfield’s daily and his

faux Bancks Sunday. Next to me on the other side sat Greg Evans, and nearby his daughter Karen hovered. She has joined her father in writing Luann for the last couple of years. At present, they are engaged in writing the wedding sequence: Luann’s older brother Brad is marrying the sumptuous Toni Daytona on December 11. “Planning for a wedding takes a lot of time and energy,” Karen told me with a straight face. (Hers not mine.) Even a fictional wedding. Greg, turning to me, said he’d been intrigued by something he’d seen on tv or read somewhere. “This fellow was saying that the worst word in the language is ‘moist.’” “Worst” meaning, I suppose, “most revolting.” “I dunno about the worst word,” I said, “but I think the best word is ‘windowsill.’” “Windowsill?” “Beautiful sounds,” I said. “The double-u’s and the l’s. Windowsill.” The next day, Karen reported on a conversation she’d had on the subject the previous evening. “‘Cellardoor,’” she said. “Someone said ‘cellardoor’ was the best word.” “Well,” I said, “it is certainly right there with ‘windowsill.’” But I’m not sure it’s a “word”: maybe it’s two words, “cellar door.”

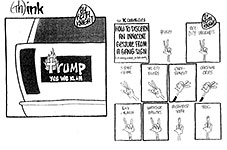

THE CON OFFERS ABOUT TWENTY “PROGRAMS” every hour, covering every aspect of comics production and featuring “fan favorite” movies and television programs. “The Walking Dead” is big this year (again), and the comic book superhero movies are likewise popular. Hollywood studios bring stars down to San Diego to amuse the fans, and long lines form at the meeting rooms where the stars will glitter. Sometimes, depending upon the popularity of the stars, lines form the day before, and people sleep all night in them, holding their places in line for the opening of the meeting room the next day. During the first evening in my hotel room, I browsed the program offerings and listed about 15 I’d like to attend. But I actually attended only six, and at two of those, I was on the panel. At one, I presented my time-worn slide show “How Not to Read Comics Like a Book,” which emphasizes the narrative role of pictures in comics. The session was one of the line-up of programs engineered by the Comic Arts Conference, which is “designed to bring together comics scholars, practitioners, critics, and historians for the dynamic process of evolving an aesthetic and a criticism of the comics art form.” The Conference started in 1992, and I was there. Over the years, participation by “scholars” has grown; participation by “practitioners” (actual cartoonists) has shrunk. At the other session, I joined Jim Davis of Garfield fame to help launch a new book, The Art of Garfield, from Hermes Press. I wrote an Introduction for the book, and I’d spent several hours with Davis years ago, interviewing him. Davis, who was making his first Con appearance, has doubtless spent hours making such presentations over the years and kept the session lively and funny. I went to a session on Crockett Johnson’s Barnaby, the famous strip about a six-or-seven-year-old boy who has an imaginary godfather named Mr. O’Malley. I’d written an Introduction to one of the Fantagraphics reprint volumes. I attended two sessions with African American cartoonist Keith Knight on the panel. One discussed “all things nerdy concerning people of color.” At the other one, Knight was spotlighted, and he showed cartoons he’d drawn that addressed the issues of “Black Lives Matter.” He insisted, rightly, that the time to address those issues is now, and he keeps doing cartoons about them, hoping to keep the issues alive, demanding solution. In addition to his syndicated daily comic strip, The Knight Life, Keef does two other cartoon features. Dunno how they’re distributed, but they appear less frequently than the strip. The oldest of the two is The K Chronicles, in which Keef himself is a major player (as he is in the strip); the other, th(ink), is a more overtly political conveyance. Here are a few samples.

At

another session, I celebrated with two old friends from my Champaign days—John

Jennings and Damian Duffy—who’d collaborated on producing a graphic

novel adaptation of Kindred, Octavia Butler’s time-traveling novel about

slavery times. Duffy adapted; Jennings drew. Here are a couple pages of

Jennings’ raging pictures from the book. These are “sketches”; the final

publication will be in color. Someone in the audience asked how Jennings, who’s African American, and Duffy, who’s not, got together. I was sitting in the audience, so they blamed me, recalling the many lunches we’d had together at Carmens and the White Horse. (But they’d been working together before we were lunching together; at this session, they were just kidding.) Among the other panels on my list were sessions on Mad magazine, comics journalism, Trina Robbins (herstorian), 40 years of Fantagraphics, Rube Goldberg, historical comics, and a session discussing Will Eisner, Harvey Kurtzman, Charles Schulz and Jules Feiffer. Many of these I missed because of schedule conflicts: they took place when I was signed up to be at the NCS booth, or I went to another session offered at the same time. I missed a program on Walt Kelly because I was elsewhere. On Saturday morning, I attended, as I usually do, the celebrated “Quick Draw” program at which Mark Evanier poses drawing dilemmas or puzzles, and Sergio Aragones and two other cartoonists (this year, Scott Shaw and Keith Knight) solve the puzzles by interpreting them visually—while we all watch their minds at work as revealed by projections on large screens behind them of their hands drawing on pieces of paper. Sergio is always the champion, coming up with a funny picture quicker than the others on the panel. In another variation of the operation, Evanier gives the cartoonists three words (Sour, Wiggle, Anger) then calls up someone from the audience. The cartoonists draw pictures that supposedly illustrate the three words in turn, and the poor hapless audience member (it’s often Peter David) tries to guess the word by deciphering the drawing. Like charades but with pictures rather than poses or motions. At this session, Sergio was given the Icon Award, presented to outstanding practitioners in the profession or in fandom. Sergio certainly deserves it: he’s been a mainstay at the Con for years, the only practicing cartoonist regularly on the premises. All of the foregoing is what I’ll be missing next year, when, for the first time in 26 years, I’ll stay home. Now here are some of the photographs I took.

AMONG THE PHOTOGRAPHS in the last display above is one of David Siegel, holding a copy of the latest issue of Alter Ego, No.142, in front of him. I was sitting at a table in the NCS booth doodling determinedly when I sensed a presence, and, looking up from my drawing, saw David, just as you see him in the photo. “I’ve never written a comic book,” he said, excitedly, “and I’ve never drawn one, but I’m on the cover of Alter Ego.” That’s how David sees the world—in terms of comics. That he should be on the cover of Alter Ego, fandom’s oldest still-published fanzine, was an achievement, a singular accomplishment. A tribute. And in David’s case, it was thoroughly deserved and long overdue. For about a dozen years, starting in the early 1990s, the San Diego Comic-Con every year had a series of sessions that featured Golden Age writers and artists. After the first few years, the “Golden Age panel” was a spotlight event. And David Siegel was largely—if not single-handedly—responsible for the presence of those Golden Agers. A taxicab driver in Las Vegas in his secret identity, David went to his first comic con in 1977. He went to his first Sandy Eggo Con two years later, and he met Jack Kirby there. Kirby came every year since the first Comic-Con. And David was smitten. He always doted on comic books, but meeting Jack Kirby started his thinking: how come there weren’t more Golden Age comic book creators at the Con? That inspired him. He began contacting friends and acquaintances in the business, scouring phone books and reaching out to informal networks to find Golden Age creators who were still alive—and where they lived. Once he had a phone number, he’d telephone them to see if they’d be interested in coming to the Con as a guest. He never promised they’d be invited as a guest. But if they told him they were interested, he said he’d see what he could arrange. At first, he went to the Con committee to see if they’d finance a Golden Age guest—air fare, hotel room and so on. If they said “yes,” he went back to the Golden Ager and closed the deal. David’s story is told in an interview conducted by Richard Arndt in that issue of Alter Ego. Full of anecdotes and stories, the article is copiously illustrated with photographs of the Golden Agers and David and reproductions of pages of the comics the guests had created in the Golden Age. For a brief time in the late 1990s, the Con fostered an organization called the American Association of Comicbook Collectors. The AACC sponsored a dinner on one of the Con evenings, and Golden Agers were honored guests. During the time the AACC was active, David worked with it to bring Golden Agers to the Con. Eventually, however, David sought freedom from the ifs, ands or buts of relying on some Con-affiliated operation. He began finding funding himself for Golden Age guests. Starting with Sheldon “Shelly” Moldoff in 1993, David engineered the guest appearances for dozens of Golden Agers, including— Creig Flessel, Vincent Sullivan, Fred Guardineer, Paul Norris; David worked with the Con’s Golden Age panel organizers, helping to secure Gil Kane, Russ Heathk, Marty Nodell. Other guests David arranged for (or helped arrange for)—Chad Grothkopf, Harry Lampert, Ramona Fradon, Irv Novick, Joe Giella, Jim Mooney, Kurt Schaffenberger, Dick Ayers, John Broome, George Tuska, Nick Cardy, Chuck Cuidera, Irwin Hasen, Alvin Schwartz, Arnold Drake, Frank Bolle, Frank Springer, and Tom Gill; Sy Barry, Lee Ames, and Jack Burnley. And these are only those David told Arndt about. In 1995, David received the Con’s coveted Inkpot Award. After 2005, Siegel quit getting Golden Agers for the Con. Too many were dying on him: he got to know them, valued the friendships, then they died. “I was losing steam,” David told Arndt. “I was getting tired of seeing people that I’d become friends with passing away from old age—more and more, it seemed, every day. It’s a natural thing, but it took a tremendous toll on me. I’d reached a point in my life where I felt very empty going to the Comic-Con.” David’s first “get” could have been Wayne Boring, the storied artist who drew Superman for so many pace-setting years. But when in 1985, he arranged for Boring’s name to be brought before the Con committee responsible for inviting guests, they inexplicably refused. Typical bureaucratic hesitancy, doubtless, in the grip of budgetary controls—or sheer myopia. Hard to say why but easy, alas, to understand. “They didn’t give a reason for their refusal,” David said. “Boring passed away in February 1987. If they’d invited him, he could at least have had the honor of being invited to the San Diego Comic Con even if he couldn’t attend.” And that persuaded David to work on his own to get Golden Agers to the Con. “Like the old saying goes,” he said to Arndt, “—‘If you want to get something done, you’ve got to do it yourself.’” A few days after I got home, I got an envelope from David. In it was the “David Siegel” issue of Alter Ego. Dunno how he got my address, but that’s what David got to be good at doing, finding addresses. Thanks, David.

READ & RELISH Donalt Rump wants to prevent violent Muslims from entering the United States. To this purpose, all immigrants will be asked a penetrating question: Are you a violent Muslim? Naturally, violent Muslims will say “yes” and therefore can’t enter the U.S. A week or so ago, the Trumpet proposed ramping up his immigration policy by incorporating “extreme” vetting in the process. In “extreme” vetting, immigrants will be asked the penetrating question a second time.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue. A completed episode displays decisive action or attitude, telling us that the book’s creators can manage their medium.

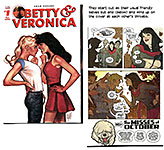

WE’VE BEEN WAITING FOR THIS ONE A WHILE. The “new” Betty & Veronica, written and drawn by Adam Hughes. A widely admired drawrer of the feminine form, Hughes proves here that he can tell a goodly tale, too. Betty and Veronica begin this issue as friends—Betty doing all the work; Veronica lounging around at her ease. They end as enemies. The mcguffin is Pop’s, the beloved soda-hamburger shop where Archie and Jughead and the rest of the gang hang out. It’s closing. Or, rather, being foreclosed. Betty passionately launches a fundraising drive to save the shop. Then she discovers (a) that Veronica Lodge’s father owns the bank that is foreclosing on Pop’s, and (b) that the new tenant for the shop is a coffee company that Veronica’s father owns. In effect, as Archie puts it, “Veronica’s father is running Pop’s out of town.” When confronted, it seems Veronica could care less, which sets Betty off on a tear. The book concludes with a fight brewing between the erstwhile friends. Hughes manages to prolong revealing the Lodge connection for most of this issue. He slowly builds suspense while at the same time deftly revealing elements of the plot as he goes along—all the while having the characters engage in teenage banter. Nicely done. The book’s “narrator” is, drat, a dog. A sheepdog by the look of him. Named J. Farnsworth Wigglebottom III, he speaks in grandiose prose. But I don’t see that he adds anything to the tale. Nothing in the story needs a narrator. We could have done just fine without him. Maybe Hughes will reveal a profound interdependence in some future issue, but in this issue, Wigglebottom’s presence is a superfluity. Cute but wholly unnecessary. But we tune in to this issue for Hughes’ pictures not his story. His portraits of Betty and Veronica and Moose’s girlfriend Midge are exquisite—beautiful girls, and (the mark of a master limner of ladies) they look like individuals not copies of one another. But that, given Hughes’ skill, was expected. Not expected is the muted color throughout the book. The toned-down intensity takes the book out of the realm of “funnybooks” and into another kingdom altogether, where the pictures border on realistic. And some details—facial features and hair— while still rendered in line, are drawn in a different hue of the same color family as the principal subject; the line strokes that indicate Betty’s blonde hair are drawn in a light shade of brown, a tint, so to speak, that delineates the layering of her hair-do. These aspects of the book’s color are the most striking of the issue.

The colorist is Jose Villarrubia, but I suspect the decision to go muted was Hughes’, no slouch of a colorist himself. The last portion of the issue reprints “a classic tale of the original BFFs,” says Jon Goldwater: “It’s time to get a sense of where things started.” Drawn by the iconic Archie illustrator, Dan DeCarlo, it’s a refreshing look back. As a bonus, we have a self-congratulatory two-page spread displaying all 24 alternative covers for this issue. I have both Hughes’ and Ryan Sook; Sook can draw beautiful women, but, alas, they all look an awful lot alike.

I WAS SURPRISED when I saw the byline over a column in Time magazine some months back— Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, all-time leading scorer of the National Basketball Association. In the magazine, he writes, usually, about some racial issue, and he always makes good sense. But I was surprised again when I saw his byline on a comic book—specifically, Mycroft Holmes and the Apocalypse Handbook, just out. From straight expository prose to fanciful fiction. And then I was again astonished —even more so this time—to learn that Abdul-Jabbar is a New York Times bestselling author, having written twelve books, including three childen’s stories (one of which won the NAACP Award for Best Children’s Book), two autobiographies, several historical novels, and the prose novel Mycroft Holmes, his first work of fiction, which he wrote with Anna Waterhouse, a professional screenwriter and script consultant. That’s a lot of writing credit for the seven-foot two-inch Basketball Hall of Famer (since 1995). And now, a comic book. Comic books require a wholly different writing sensibility than prose fiction. More like script-writing for movies or television. Again, Abdul-Jabbar had help: Raymond Obstfeld and Joshua Cassara. Roles are not specified, but my guess is that Obstfeld helped with the story and Cassar did the drawing. And they do all right. Abdul-Jabbar, an English and history graduate of UCLA, became addicted to Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories early in his basketball career and claims to have adapted Holmes’ powers of observation to the game in order to gain an edge over his opponents. “I read the Conan Doyle stories during my rookie year in the NBA,” Abdul-Jabbar says in the comic’s closing pages, “—and was fascinated by Holmes’ ability to see clues where others saw nothing. I was intrigued by his ‘older, smarter brother’ [Sherlock’s characterization] who was involved with government at the highest levels.” So high are the governmental levels at which Mycroft works that Sherlock once says the government could not function without him. The debut issue of the comic book begins with a 5-page episode in which a man in a derby hat wearing a scarf destroys a museum and, presumably, kills several people who happened to be within. None of which has any apparent connection to the tale that follows. The narrative begins in Cambridge in a philosophy class. It is there we meet Mycroft Holmes, the older brother of the more famous Sherlock. Mycroft is mentioned in only a few of the canonical Sherlock Holmes stories, and he appears in only two. In both, he is described as “strapping,” and Sidney Paget’s picture of him show him to be somewhat stout. Admittedly, the Conan Doyle tales take place some years after this comic book adventure, which is dated 1874. At that time, Mycroft was, to judge from Cassar’s portrait, a normally proportioned even somewhat muscular youth. In the only self-contained complete episode in the book, Mycroft engages in an intellectual debate with his profession—and wins. For which impudence, he is almost tossed out of Cambridge. He displays wit and towering snobbery. He’s self-satisfied, has a high opinion of himself, and he’s snooty. In these traits, he’s much like the effete know-it-all snob Philo Vance in the detective stories by S.S. Van Dine (aka Willard Huntington Wright). Not an admirable personality even if gifted. His younger brother, who shows up later on, is a much more likeable character. As if to demonstrate Mycroft’s masculinity, we see him next, naked in bed with a young woman, equally naked. They are interrupted by the arrival of a somewhat peevish Sherlock, who explains that Mycroft’s invitation to visit was arranged deliberately so that Sherlock would see a naked woman. “Lord knows,” Mycroft says, “with his personality, this will be his only opportunity [to see a naked woman].” While Mycroft and Sherlock exchange witticisms, the apartment is invaded by three men wearing masks. After a couple pages of scuffling, they kidnap Mycroft; we next seem him suspended upside down from a ceiling. In his exchange with his captors, Mycroft proves himself a gifted observer—not unlike his brother Sherlock— determining by keen observation that his chief captor is the “dean” of the Cambridge school who managed to get him reinstated after his go-round with the philosophy professor. This is something of a mis-characterization: Conan Doyle’s Mycroft was noted for his superior memory, not his powers of observation; for those, he, Mycroft, relied upon his younger brother on those rare occasions when Mycroft ventured outside the halls of government. Sherlock describes his brother this way: “He has the tidiest and most orderly brain, with the greatest capacity for storing facts of any man living. In that great brain of his everything is pigeon-holed and can be handed out in an instant.” And the departments of government rely upon Mycroft’s memory to sort out the issues upon which decisions are required. But in demonstrating his ability to discern not otherwise evident facts by observing tangential evidence—Sherlock’s speciality— Abdul-Jabbar’s Mycroft reveals, also, his courage—his imperturbability—in the face of a very threatening situation. It was probably Mycroft’s being denominated Sherlock’s “smarter brother” that attracted Abdul-Jabbar; everything done here makes that point. In contrast, young Sherlock seems somewhat (and merely) ill-tempered. Abdul-Jabbar doesn’t explore Mycroft’s fabulous memory at all. As Mycroft is explaining what observations led him to his conclusion about his captor, a door bursts open and a woman wearing a tiara storms into the room, demanding to know “if this is the young man who is willing to sacrifice his own life to save the world—and more importantly, the British Empire.” There, the issue ends. Who is she woman? Probably Queen Victoria. She’d be 55 at the time of this story, and Cassar’s visual fits. Abdul-Jabbar’s story presents a not quite acceptable interpretation of Mycroft Holmes. Although it deviates noticeably from the Conan Doyle version, we can accept Abdul-Jabbar’s Mycroft as a younger, not stout at all, Mycroft—still in college, long before his plumper self became, due to his memory for bureaucratic and other details, indispensable to the British government. His snooty demeanor, however, clashes violently with Conan Doyle’s Mycroft, who was polite and at least as verbose as Sherlock but not annoying. And he was even deferential to Sherlock’s superior talents for detection, that not being Mycroft’s forte. Abdul-Jabbar’s Mycroft, we must note, is young. And Abdul-Jabbar’s previous version of the character, in the novel, was somewhat older—23; and he, while still too self-absorbed, was not the snob he appears in this comic book. Cassar’s

artistry—his storytelling, breakdowns, panel compositions and page layouts—are

expertly bent to relate and enhance the drama in the narrative tasks before him.

We can ask for no better. I’ll probably return for the second issue. Not because Abdul-Jabbar’s Mycroft is Conan Doyle’s but just to see what Abdul-Jabbar does with his version of the character.

IN JEFF LEMIRE’S Black Hammer No.1, we meet, first, a man with a gray handle-bar moustache who seems to be a farmer. He’s slopping the pigs and milking a cow. And he’s thinking about how pleasantly quiet it is on the farm. Then we meet Gail, a young girl who the farmer chastises for smoking and wearing too much make-up. We suddenly know the book is about more than farming when she takes off like a rocket and flies away. Next, in the farmhousse kitchen, we meet a guy who looks like a log (a large piece of wood, sculpted to look humanish) and another guy who is a robot, seemingly. Gail and the logman, whom she calls Barbie, meet on the barn roof and have a serious conversation about “missing” their old life. They’ve been on the farm for ten years. We realize, thanks to an introductory scrap of prose, that we’ve met members of “the greatest heroes of the Golden Age”—(in order of appearance), Abraham Slam, Golden Gail, Barbalien (from Mars) and Walky-Talky, the robot. Later in this issue, we meet Colonel Weird, an interstellar adventurer, and Madam Dragonfly, mistress of the macabre. Slam and Gail and Barbie (assuming, for the nonce, a more humanoid appearance) go into town for supplies. Slam calls upon the woman he’s in love with, and Gail steals cigarettes, and Barbie (calling himself Mark Markz) goes grocery shopping. Slam has an unfriendly encounter with his woman friend’s divorced husband, the town sheriff, who has caught Gail with her ill-gotten loot. Mark/Barbie has a conversation with a preacher about salvation. Back on the farm, Slam and the others convene at eight o’clock, when they recall their history—their saving Spiral City, and the death of their most admired cohort, Joe Webber, whose weapon was a hammer (like Thor). Webber apparently gave his life so members of his team could escape superheroing and live quietly in the country on a farm. The concluding pages offer a captioned “history” of the superheroes, showing and identifying each of them in their proper roles. The captions, it develops, are being written by Joe Webber’s daughter, who believes her father’s friends are still alive (and we know they are) and vows to find them. This

is as nicely done a first issue as you could want. We meet the principals,

learn a little about them (partly through their actions in several completed

episodes; partly through the Webber daughter’s account, with pictures of the

heroes in costume). There are tensions in the country—Slam’s girlfriend wants

to visit his “family” on the farm, and her divorced husband doesn’t like her

friendship with Slam. And Gail is rebellious. But the cliffhanger—the

daughter’s Dean Ormston’s visuals are expert and telling, in the best traditions of comic-book storytelling. He shifts camera angle and distance, changing focus for both variety and emphasis. His line is clean and slender—all to the good. But his tendency is to fleck the pictures with a spray of little lines that add nothing to the depictions. A little annoying. But his otherwise superb storytelling overwhelms these minor annoyances.

WHAT DO I READ for my private amusement? Lately, I’ve been reading Daredevil (drawn by Goran Sudzuka), Black Widow (Chris Samnee), Moon Knight (Greg Smallwood), and American Monster (Juan Doe). Brian Azzarello’s tale in American Monster is desultory to the point of near aimlessness, but Doe’s visual storytelling is inventive, sometimes to the point of startling. Likewise, Sudzuka, Smallwood and Samnee deploy the visual resources of the medium in imaginative ways—each in his own individual style, recognizably no one else’s. In a page from Black Widow No.5 in the foregoing visual aid, we can see why Samnee is given co-writer credit with Mark Waid: the narrative on this page (and through most of the pages of this issue and the previous four) is carried by Samnee’s pictures. Comics are a visual medium, and these artists have raised “visual” to an art form. Oh—and Kaare Kyle Andrews’ Renato Jones: One% is another exemplar of the arts of visual storytelling. The drawing is energetic, the page layouts imaginative, and the leap-frogging storyline fascinating. And keep your eye on The Fix, written by Nick Spencer, which, through No.2, offers a unique concept, well executed by Steve Lieber, and The Black Monday Murders, by Jonathan Hickman with art by Tomm Coker, who deploy both text and pictures in unconventional ways to tell their story. More about them next time, no doubt; this time, I’ve run out of time.

IT WAS BOUND TO HAPPEN, sooner or later. Superhero comics began, essentially, as exercises in figure drawing. They have morphed lately into something more, but figure drawing is at the beating heart of superhero comics. And so it is a natural evolution for some of the figures being drawn in comics to be of the curvaceous sort. And once you’ve started drawing the opposing sex with any kind of seductive quality, you graduate, eventually, into drawing barenekkidwimmin. So we’ve lately been “treated” to visions of the feminine form unadorned. The most blatant of this phenomenon—and perhaps the first of this breed—is probably Zombie Tramp, which specializes in fully ripened watermelon-sized boobs; and you can order special editions with nudity flaunted on the cover (as you’ll see when we get to the visual aids in a trice). The Zombie Tramp books, now up to No.23, are vaguely amusing: at least the renditions of naked ladies have a bigfoot comedic component about them. Nothing particularly erotic (apart from sheer nudity) prevails in this title, but others who have followed along with markedly less comical rendering are eroticized to a fare-thee-well. There can be no other reason for Matt Martin’s Webwitch. It exists solely to display pictures of nekkid women—starting with the spectacular wrap-around cover of No.4, which we see in this vicinity. Every interior page displays female nudity. And even, as we see nearby, fornication (one thing leading to another). The story, such as it is, involves female demons who are trying to conceive a king. Hence, the fornication scenes. But it quickly deteriorates into gory beheadings and other sorts of dismembering, splattering naked lady bodies with blood and gore.

Lookers is another of the same breed. The title characters are apparently lesbian lovers whose mission in life is to attack and belittle men who regard women as sex objects. In the opening episode of No.0, one of the team assaults a youth who is amusing himself by watching barenekkidwimmin on the Web. In the later pages of this title, monsters and heavily breasted demons take over the narrative, joining attraction and repulsion in a fiendish mash-up.

But writer Mike Costa and penciler Ron Adrian (with attractive inks by Alex Lei) have the grace to commit a deliciously comical sequence in which, as we see in the last illustration of the accompanying visual aid, one of the Lookers gains admittance to a closed building by a maneuver that blatantly, er, embodies the book’s message. I bought the book solely to add this page to my comic book collection. Jungle Fantasy is another matter. No.1 introduces us to Kit and Lani, whose space ship blew up, leaving them stranded on an island where they have to battle dinosaurs of various sorts (which they do mostly unaided by clothing). Then the girls run into other marooned persons—all male and decidedly thuggish. They have a naked woman in tow, Sarah, and when Kit tries to rescue her, the thugs take her prisoner and tie her to the same tree Sarah is tied to. One of the thugs explains “the rules”: “We will use you how we want, whenever we want, and as long as you are pleased, you stay alive.” Then, to demonstrate the extent of his seriousness, he breaks Sarah’s neck because “she haven’t gotten into the spirit of it. Then Lani shows up, and she and Kit pretend to be interested in the sex play of the guard thugs, who fall for their trick. And then at the moment of climax, they turn on their “captors” and reverse their roles.

This is the most vile sort of sadistic sex, kimo sabe—abusing women while using them in degrading ways. Sick stuff. The publisher, Boundless, a division of Avatar Press (my old friends in Urbana, Illinois), responsible for the last three titles we examined, needs to watch its step. Nothing will inflame the censorious multitudes of “concerned parents” like a threat to the sexual innocence of their children. And many citizens, even in these enlightened Trumpish times, think comic books are for children. These books are decidedly not. And these, particularly Jungle Fantasy’s nastiness, threaten to destroy the innocence of childhood and will therefore bring out the wrath of this mob quicker than any form of graphic violence. Yeh—they’re just stories. And we wouldn’t want to stifle creativity or violate the First Amendment. But these books are just nasty. And they thereby threaten to shut down on the creativity of others. They should be marketed to a more exclusive market.

QUOTES & MOTS Talking Points Memo by Lauren Fox Former Jeb Bush campaign adviser Sally Bradshaw has left the Republican Party and has registered as an independent in the state of Florida because of Donald Trump, CNN reported Monday. According to the report, Bradshaw will vote for Hillary Clinton in November if the race is close in Florida. After years of working with the Bush family and helping author the Republican Party's autopsy report, Bradshaw told CNN she could no longer look her children in the eye and support the Republican candidate this cycle. "This is a time when country has to take priority over political parties. Donald Trump cannot be elected president," Bradshaw told CNN in an e-mail interview. "As much as I don't want another four years of Obama's policies, I can't look my children in the eye and tell them I voted for Donald Trump. I can't tell them to love their neighbor and treat others the way they wanted to be treated, and then vote for Donald Trump. I won't do it." Bradshaw told CNN that while she had seen Trump as a "bigot" and "misogynist" throughout the race, Trump's latest attacks against the Khan family who lost their son in the Iraq war in 2004, was just another reminder of why she couldn't back him. "If anything, that reinforced my decision to become an independent voter," she told CNN. "Every family who loses a loved one in service to our country or who has a family member who serves in the military should be honored, regardless of their political views. Vets and their family have more than earned the right to those views. Someone with the temperament to be president would understand and respect that." Jeb Bush has already said he cannot vote for Trump. But Bradshaw's insistence she will vote for Clinton if the race is close raises the stakes for the GOP. Bradshaw said that she will re-register as a Republican if the party returns to its values. "If and when the party regains its sanity, I'll be ready to return," she told CNN. "But until Republicans send a message to party leadership that this cannot stand, nothing will ever change." This article was written by Lauren Fox from Talking Points Memo and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy IF PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS are the vaudeville of the Republic, then Trump is the clown prince. From his outlandish appearance—knit hair to gaping maw—he is a wholly unprecedented gift to editoonists. He’s a walking talking satire of the American politician, a veritable caricature of a candidate in action—his every utterance and the manner of its delivery, a roaring ridicule of the actors at the center of the electoral process. And

so when this big mouth buffoon actually achieved the Republicon nomination, it

was hard to believe. Time magazine announced Trump’s nomination with an editorial cartoon on its cover. Depicting only Trump’s eccentric hair-knit, the magazine seemed to be saying, “Are you serious? Do you seriously believe a man with this on his head could lead the government of the world’s most powerful nation?” The same image—a little smaller but with perhaps the same message—appeared inside The New Yorker that week. Are

we electing a competent person? Or a ridiculous hair-do? Are we seriously

considering electing as President of the United States a man who cannot go

outdoors on a windy day for fear that his persona will be destroyed? If

we are to judge from the headlines and punditry and cable tv news coverage, the

only things that happened during the month of July were the Republicon and

Democrat nominating conventions in Cleveland and Philadelphia, respectively.

The Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm lumbered onstage first, and our first