|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 353 (June 5, 2016). SEVENTEEN YEARS! Yup, we’ve been hoppin’ down the rabbit trail for 17 years, at least twice a month without fail. Who woulda thunk it? We’re amazed. And we hope you are, too. We don’t do anything special for the occasion, just the usual LAVISHLY ILLUSTRATED casserole of news and reviews (some comics from Free Comic Book Day, half-a-dozen books), highlighted by Bobby London’s firing revisited, Complete Peanuts completed, Ted Rall’s Bernie graphic novel examined, and recent editoons, cartoons in Playboy again! The New Yorker zoo, appreciating Darwyn Cooke and Mell Lazarus, and, just in time for the election season, a startling proposal on campaign finance reform that will revitalize American politics. And more, of course—much more. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order—:

Our 17th Year Completed Bob Hall’s Batman Revisited

NOUS R US Black Panther Movie (Of Course) The Latest Playboy

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Free Comic Book Day Harvest—: Suicide Squad Lady Mechanika The Censored Howard Cruse Loose Ends Peter Panzerfaust, No.23

EDITOONERY Some of the Month’s Best Editorial Cartoons Dixon Diaz, Another Internet Parasitic Imposter

PERSIFLAGE & FURBELOWS Cutthroat CalipHATE and the Crusades

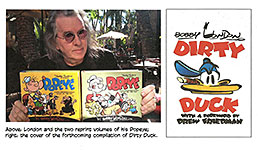

BOBBY LONDON AND POPEYE Dirty Duck Omnibus Forthcoming

PITHY PRONOUNCEMENTS On the Effectiveness of Editorial Cartoons

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Sex and Potty Humor in the Funnies Jake Tapper Guests on Dilbert

BOOK MARQUEE Reviews of—: America in Cartoons: A History in Pictures Dictators in Cartoons: Unmasking Monsters and Mocking Tyrants Black Hand Comics

GAGGING WE SHALL GO Single-panel Gag Cartooning New Yorker Zoo New Yorker Spots Chartoons

BOOK REVIEW The Complete Peanuts—: Volume 25 and President Barack Obama’s Introduction Volume 26, Ephemera The Constant Renewal of the Strip When (Exactly) Did Charlie Brown Become a Loser? Designer Seth’s Insights

MOTS & QUOTES Adam Hughes on Betty and Veronica

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOONS TRIPS Review of—: Ted Rall’s Bernie

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Trumperies PASSIN’ THROUGH Darwyn Cooke CAMPAIGN FINANCE REFORM A Workable Radical Proposal

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

Our 17th Year Is Completed This Month! That’s right: we’ve been posting these reports and folderols twice a month for SEVENTEEN YEARS, kimo sabe. Unbelievable, now that I think of it. And here, to celebrate stamina, a review that we ran in our second outing, May 22, 1999. All Hail, Hall. Bob Hall. In Batman: I, Joker, Hall created superhero mythology. Batman: I, Joker is an Elseworlds Batman story told by the Cowled Crusader's arch enemy. But the plot is laid far in the future by which time Batman is a god-king called "The Bruce." The Bruce is maintained in power by the faith of the populace, and the faith of the people is sustained by regularly enacted feats of violence against a recurring cast of villains—the Penguin,Two-face, the Riddler, Ra's al Ghul, and the Joker. Once every year,volunteers are invited to capture or kill one of this bunch— and, if successful, to challenge the Bruce to personal combat to the death. If victorious, the successful citizen will become the new god-king. In addition to incorporating elements of the Fisher King myth, Hall has constructed (as I trust you can tell from the foregoing) a clever parable that parallels the relationship between the comic book hero, Batman, and his faithful readers, before whom (like the Bruce), Batman re-enacts periodically the ritual conquest of a litany of arch villains. Having set up the resonances of this situation, Hall then proceeds to explore its implications. And I'll not say more about that in deference to your undoubted desire to find out what happens on your own. Hall's artwork and storytelling abilities are well displayed here. He renders anatomy in chips and chunks like raw meat, making dramatic use of solid blacks and deep shadows, and he paces the tale with breakdowns that create the story's atmospherics in flashes of consciousness. Nifty stuff, deftly done. Look for your copy in the back-issue bins at the summer cons.

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

BLACK PANTHER MOVIE (OF COURSE) I shoulda known: the new Black Panther comic book is the harbinger of the movie, which is due to appear in 2018. The comic book, meanwhile, is being written about all over the place, as if celebrating the 50th anniversary of the character’s debut. With every article, the comic book’s writer Ta-Nehisi Coates —a genuine literary talent, not just a funnybook scribe—gets interviewed. In Entertainment Weekly (May 13) he says: “People like the kind of badassery inherent in T’Challa. I mean, who doesn’t? People have this hero that is black and isn’t compromised in any sort of way. He’s powerful; he’s the king of his country.” The question Coates is exploring is whether an advanced society like Black Panther’s Wakanda needs—or wants—a monarch. Artist Brain Stelfreeze chimes in: “Every character needs something as their foundation. Superman’s is hope. And with Black Panther, his foundation is pride. To the black audience, that really resonates.” Other black heroes remain beloved, says EW, “but there is a different kind of fervor surrounding Black Panther. He doesn’t just have fans; he has disciples.” What about the Moon Knight movie, then? Another recently resurfacing Marvel superhero, but this one’s nuts.

CARTOONS AND PLAYMATE OF THE YEAR Whoop! The June issue of Playboy has two full-page cartoons in it. I think they’re cartoons. They seem to be funny in a deliberately effete way. Or not. The wolf and the damsel doesn’t seem very amusing. Could be me, of course. Is the wolf passing around a reefer? How’s that funny? Still, maybe these two cartoons are the thin edge of the wedge. Maybe Hugh Hefner’s minions are re-thinking the most criminal part of their re-design and re-branding. Maybe they’ll start publishing cartoons again. Cross your finger.

See what you think from the evidence we’ve gathered near here.

ODDS & ADDENDA “Captain America: Civil War” led in North American box office receipts again May 13-15, the fifth straight weekend at Number One. The Disney movie is now among the biggest superhero movies ever, having generated weekend sales of $72.6 million in the U.S. and Canada.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment and in the scroll to follow is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics

FREE COMIC BOOK

DAY HARVEST. Among the five free funnybooks that my comic book store allowed

its FCBD visitors to carry off, I picked up Suicide Squad, the cover of

which purports it to be No.1. The drawing (by a trio, Federico Dallocchio,

Randsom Getty and Scott Hanna) is attractive enough, but Adam

Glass’s story is flat-out repulsive. We watch while members of the Suicide

Squad are tortured—disgusting, painful and sadistic tortures with bloodshed

galore and generous bruising all around—for over half the book. Then we find

out the torturing was a test that qualifies them as agents of Task Force X. And

the whole time, I can identify only three of the victims—Harley Quinn,

Deadshot, and the character with the shark head, “the Shark,” I presume. This

is terrible stuff, kimo sabe. Too awful to waste more words on. I also picked up a copy of Joe Benitez’s Lady Mechanika. The steampunk fashion has fascinated me ever since it started some years ago. It seems essentially satiric: the foundation garment garb of its women represent an assault on Victorian sensibility. But inside the book, I was soon disappointed: the coloring rendered the art too dark to discern. And the story, starring a woman who is “the sole survivor of a mad scientist’s horrific experiments that left her with mechanical limbs” and who is making a new life for herself as a private investigator, seemed little more than a series of physical encounters between the PI and various unappealing bad people. Loose

Ends by Jason Latour as rendered by Rico Renzi looks to me

like a revival of a title I tried to find years ago. I found a couple issues

but never could locate the first. It’s distinguished (in both meanings of the

word) by wildly differing drawing styles that Renzi adopts for different facets

of the story. Nicely done. Another

item on the stack of FCBD trophies is The Censored Howard Cruse from

Boom!

WHILE COLLECTING Free Comic Book Day trophies, I also picked up the most recent issue of Peter Panzerfaust, No.23. I didn’t like this title when it first arrived a couple years ago, but on the chance that I was wrong then, I decided to give it another try. No good. It’s still lousy. This issue involves Nazis killing a couple of doctors after the two have saved Nazi lives, followed by a long conversation among Panzerfaust’s followers about things I (a mere dilettante visitor to the premises) can make no sense of (references to the Hook and the Croc—Peter Pan?), then Peter P shows up and broods about whether to undertake a new mission, “The Final Battle.” We also meet Peter’s pregnant wife, Wendy. Peter and Wendy? Peter Pan again. There must be a connection, but I fail to see it in this single issue, which is otherwise a waste of time. Except for Tyler Jenkins’ eccentric drawing. Okay: I haven’t been a regular reader, so how can I expect anything in this book to make sense? True. But shouldn’t periodical literature like this be arranged in such a way as to encourage readers to jump on at any time and feel at home? Maybe a little puzzled but not completely baffled, eh?

Quotes & Mots “It is useless to hold a person to anything he says while he’s in love, drunk or running for office.”—Shirley MacLaine

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy IF YOU BELIEVE the so-called “news” media, particularly cable news and the associated commentariat, nothing much happened in May except Trumperies. Editorial cartoonists once again proved themselves incapable of resisting Trump. And who can blame them? He’s a cartoon character incarnate—the hair, the mouth, the outrageous and often insulting utterances, the misogynism, the xenophobia, the bigotry, the unbridled ignorance. He’s a creation of his own overweening narcissism and a salivating, conscienceless pandering news media that will do anything to amp readership. Responsible journalism in this day and age? Forget it. The

Trumpet made the cover of The New Yorker, one of those frail linear

treatments by the magazine’s duty political cartoonist, Barry Blitt. We

resume the Trumpery in our next visual aid, starting with Matt Davies at

the upper left, who deploys a memorable image to suggest that Trump’s foreign

policy is vague: the outline is made with dashes. But it’s great, right? Next around the clock, David Horsey creates the scene I conjure up in words at the end of this posting under The Spreading Punditry. The best analysis of the Trumpet yet (naturally—it’s mine, too): he’s the barstool bullsitter, a familiar character in every neighborhood saloon. Next, Nick Anderson highlights the wonderful irony in North Carolina’s governor saying the federal government is “over-reaching” in declaring his new law unconstitutional. And what about the over-reach of his law? And finally, we have Dan Wasserman demonstrating another colossal irony in four panels that advance the argument to the point of utter collapse. We

take a break from Trumperies in our next exhibit. To make a stab at fair and balanced, here’s Mike Lester’s comment on the other “presumptive” candidate. Conservatives like Lester are not likely to let us forget Hillary’s dire situation with the FBI demonstrating its dogged dedication. But the thing that I admire in this cartoon is the Hillary caricature. Two

more editoons finish us off for this outing. Below Diaz is another Matt Davies effort, three panels that set up for the political punchline—one of those conversations in which Trumpsters reveal their essential ignorance. And

with that, we return to Dixon Diaz. Not knowing the name, I googled him and

found more of his “cartoons” at conservativepapers.com, where he lobs his bombs

at unsuspecting readers who actually think he’s a cartoonist. Notice the four strips stolen from Aaron McGruder’s Boondocks. These appear in a line-up of13 identical strips. All of them look exactly alike. Diaz offers apologies to McGruder, but if he’s sincere, he’d quit photocopying McGruder’s work. Or at least he’d change strips so the line-up is not so obviously a rip-off. He steals from Charles Schulz’s Peanuts, too—but no apology this time. Ditto his theft of Archie. He’s absolutely shameless. An unabashed disgrace and an insult to actual cartoonists everywhere.

PERSIFLAGE & FURBELOWS Pondering, more often than I’d like to, the atrocities committed by the Cutthroat CalipHATE, I wondered if there has ever been a more depraved and gruesome perversion of religious beliefs. And then I remembered the crusades of the 11th and 12th centuries, and I turned to Will Durant’s Age of Faith to find out more. The crusades (there were half-a-dozen or more of them, depending upon how you count) were in effect “commissioned” by the Pope to rid the Holy Land of infidels (Muslims) who might pollute the holy sites or prevent earnest pilgrims from visiting them. The First Crusade (1096-99) perhaps set the tone by massacring Jews in Germany as the pious passed through the country en route to the Holy Land. Jerusalem fell in June 1099 after a 3-year siege. Reported the priestly eyewitness Raymond of Agiles: “Numbers of Saracens [Muslims] were beheaded ... others were shot with arrows, or forced to jump from towers, others were tortured for several days and then burned in flames. In the streets were seen piles of heads and hands and feet. One rode about everywhere amid corpses of men and horses.” “Other contemporary witnesses,” Durant goes on, “contribute details: women were stabbed to death, suckling babes were snatched by the leg from their mother’s breasts and flung over the walls or had their necks broke by being dashed against posts; 7,000 Muslims remaining in the city were slaughtered. The surviving Jews were herded into a synagogue and burned alive. The victors flocked to the church of the Holy Sepulcher, whose grotto, the believed, had once held the crucified Christ. There, embracing one another, they wept with joy and release, and thanked the God of Mercies for their victory.” During the Third Crusade (1189-92), its star performer, Richard the Lionhearted, who dazzled with his courage and military know-how, paraded 2,500 Muslim prisoners before the walls of Acre and had them all beheaded because the defeated defenders of the city were slow in carrying out the terms of their surrender. So the Cutthroat CalipHATE, sadly, is not unique.

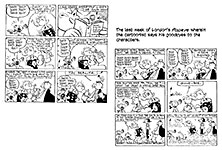

BOBBY LONDON AND HIS RUDELY IMPOSED DEPARTURE FROM POPEYE As we noted in November 2014 (Opus 333), Bobby London was fired in July 1992 as the cartoonist producing the King Features comic strip Popeye. London is a noted underground cartoonist, a member of the notorious Air Pirates gang, famous in later years for creating Dirty Duck, a character he drew for more than 40 years in the pages of various publications, including National Lampoon and, lately (until the recent purge of cartoons from the magazine), Playboy. A longtime fan of Popeye and of the strip’s legendary creator, E.C. Segar, London was invited to take over the strip when Bud Sagendorf retired in 1986. And then, six years later, he was fired. At the age of 42, he was suddenly unemployed. London may be the only syndicated cartoonist to be fired from his feature. Other cartoonists may have quit, leaving their feature to another cartoonist. But as far as I know, London is the only one to be fired. And on the face of it, King Features’ firing of London seems shameful. And gutless. The cause of his termination was a sequence, entitled “Witch Hunt,” that he began July 6. The presumably offensive part of the sequence begins at the end of the second week when Popeye suspects Olive of having an affair—and an illegitimate child—with Bluto. From there, it plunges on into the abortion issue. And hence to religious questions. Near here, I’ve posted some of the supposedly offensive strips.

On the issue of abortion, the sequence seems to be in favor of it. Popeye, after all, recommends that Olive “get rid” of the “baby” that she doesn’t want. (Actually, it’s a robot doll that she compulsively ordered through a shopping channel.). On the religious matter, London is pretty clearly ridiculing organized religion. One of the clerics who shows up is named “Nosebest.” And he is depicted as motivated by issues other than moral ones: without Satan, he proclaims, “we’re out of a job.” Which of these dubious matters got London fired? We’ve always assumed in was abortion. But the near-blasphemy is also pretty severe. In a 2014 interview at Comic Book Resources, London claimed the priests were not villains. “The tall priest was the same one administering last rites to Popeye in ‘Return Of Bluto,’ so he was definitely not a villain,” London insisted, “— and at no time and in no place did I depict either of them doing anything villainous.” Maybe not villainous, but they were both satiric targets, which makes them less than admirable men of the cloth. The priests may not be the reason London was canned, but they are no doubt part of the reason. Still, my guess is that London’s take on abortion is the main issue.

TWO WEEKS AFTER LONDON WAS FIRED, he was interviewed at comic-art.com by Steve Ringgenberg, who asked the cartoonist to explain how the firing came about. At the time, London said he had no warning that he would be treading forbidden ground and risking his gig at King; in fact, a previous mention of Roe v. Wade in the strip had lead him to believe the topic was acceptable. He’d done a gag where the Sea Hag uttered the words: “Drat! There goes Roe v. Wade.” Said London: “I didn't hear a peep out of the syndicate and since I always heard from them whenever they objected to any kinds of punchlines or other nonsense that I might have injected in the strip— which was seldom, but it did happen occasionally—I automatically assumed that Roe v. Wade was considered fair game by them and I proceeded to prepare a full-length story about the subject.” Then, all of a sudden, he was fired. Said London: “It happened very briefly and very abruptly. They just, the editor, Jay Kennedy, just called me up and told me that they were unhappy with the storyline and I was fired. It was as simple as that.” Kennedy, incidentally, was an acquaintance from before he became comics editor at King. London knew him from Kennedy’s days at Esquire when London was drawing for “slick magazines” in the late 1970s. London admitted that he’d heard rumors about King executives being not all that pleased with his Popeye work: “There was a rumor that I heard from somebody there that they'd been considering dismissing me for quite some time because they had other plans for Popeye, but I just sort of, I just kind of ignored that. I was continually ignoring rumors like that because they're just rumors, and to concentrate on my work, and see that it improved. I just, uh, I think the only serious argument I had up there with somebody was one particular individual who no longer works there, who was the former head of the licensing department.” The sequence in Popeye just before “Witch Hunt” was “Stupid Little Hat,” ostensibly about the merchandising value of Popeye’s little dixie-cup sailor hat, which London hated—preferring the billed cap of the legendary Segar’s creation. The sequence was an outright satire of licensing and merchandising. The next thing we knew here at Rancid Raves is that, over two years ago, on November 26, 2014, London was interviewed at Comic Book Resources by staff writer Alex Dueben, and during this interview, London’s memory of his final months at King proved somewhat clearer than it was when he was talking to Ringgenberg. Dueben asks London if there had been any indications before he was fired that King officials were unhappy with what he was doing. To which London responded: “I think taking my name off the strip as early as 1990 is a mild indication that they were not amused.” And it develops (as we’ll see in a trice) as Dueben and London talk that the cartoonist had been working in an undercurrent of syndicate disapproval for some time before he was fired. “Witch Hunt,” in effect, was the straw that broke the cartoonist’s pen. Was London lying then, when he was interviewed by Ringgenberg? (You can see the entire interview at comic-art.com/interviews/london.htm ; I quote pertinent parts at Opus 333.) Frankly, I don’t think so. Ringgenberg talked to him just two weeks after he was fired, and London was doubtless still in shock, however mildly. He was also (as we’ll see when I quote some of the interview with Dueben) probably still drawing Popeye strips in order to comply with the terms of his contract. He may also have been a little flustered over the incident. Understandably. And Ringgenberg’s question wasn’t all that pointed. Here’s his question and London’s reply (which, when quoted in full, shows London struggling with how to respond)—: Ringgenberg: Okay, so why don’t you run down, as briefly as you want, exactly how did the syndicate notify you that your work was unacceptable and that you were being terminated? London: Well, in, you know, uh, they, I can, I can just tell you very briefly because it happened very briefly and very abruptly. They just, the editor, Jay Kennedy, just called me up and told me that they were unhappy with the storyline and I was fired. It was as simple as that. London was answering the second part of Ringgenberg’s question—how were you notified that you were being terminated? The first part, being informed of the syndicate’s unhappiness with his work, London didn’t respond to. The conversation then wandered off into related matters, Ringgenberg trying to find out what, other than the abortion storyline, might have led up to the firing. Did subscribing papers complain? No. Was the client list growing or shrinking? A little of both, apparently.

THE CAUSE OF THE DISCONTENT at King Features was rooted in conflicting ideas about what the strip should be, and that was present at the beginning of London’s stint on the strip. With Dueben, London recalled how it all began (in italics)—: I was tapped by Heavy Metal magazine in 1980 to illustrate the Heavy Metal comic book version of the Robin Williams movie, a script by Jules Feiffer, and no one to tell me how to draw, but the movie bombed and that was it. I knew all the Westport-area cartoonists, including Bud Sagendorf. When I got the call from [King Features comics editor] Bill Yates, he said, “I hear you know all about Popeye, how about coming down and trying out?” You see, they had a problem: they couldn't find anybody who knew all the characters. My first sample was rejected because they looked too much like E.C. Segar. The second was drawn too big and the third was the charm. I was ready to pick it up wherever Sagendorf left off, but somewhere in between tryouts, they told me they were changing it into a gag-a-day strip and I balked. I didn't see how that could work. Then Yates said Elzie Segar was his instructor in a mail order cartooning course, he and Sagendorf were close friends and he was choosing me because my stuff had "a lot of heart" and he didn't want Popeye to "go the way of all the others." The flinty look in his eye disappeared when he said that, and I thought, okay, maybe I can do this. Later, King relented and let London tell stories. London’s first Popeye was dated February 24, 1986; before the year was out—starting in mid-August—London was into short continuities, telling a story that continued from one day to the next for a week at a time. Said London (in italics)—: I think they were getting bad feedback about their gag-a-day concept and eventually relented. Writing a gag-a-day Popeye strip was a total game-changer, I must say. I had to rethink my whole approach fast, and come up with something that would maintain at least a shred of continuity. I remembered my couple of years at Disney Licensing in New York where they would dress Mickey Mouse up as Michael Jackson or have him skateboarding, and all that pseudo hipster stuff, trying to update his image. I thought, what if I lampoon that whole approach with Popeye— only keep Popeye the same and have the other characters freaking out and trying to keep up with the times? It sounded good to me, and obviously it sounded good to Bill Yates because he okayed it. London said he wasn’t worried about the appearance of the strip as he took over from Sagendorf: “I wasn't concerned about the style changing radically because my drawing style was already in that neighborhood to begin with. However, I had been drawing Disney characters for two years previous to that, so I almost forgot what my own drawing style looked like. It took a while for me to draw like myself again, but it did happen.” London’s first few months on Popeye look a lot like Sagendorf; after a couple of months, though, authentic Londonish renderings were coming through, radiating a somewhat more slap-dash antic energy than Sagendorf’s. But two undercurrents were running through London’s tenure on the strip. The first—and the reason King wanted Popeye to be gag-a-day—was the animated tv series being developed as London took over the strip. Called “Popeye and Son,” in it Popeye and Olive Oyl are married and have a son named Popeye Junior, who has Popeye's ability to gain superhuman strength from eating spinach but Popeye Jr. hates the taste of spinach (preferring hamburgers like Popeye’s lazy lout buddy Wimpy), much to his father's disappointment, although he eats spinach to boost his strength. The show aired September-December 1987, and it was obviously being developed in 1986 when King hired London. Eager to make the newspaper strip dove-tail with the animated version—just as DC and Marvel want their superhero comic books to look like the movie versions of the characters—King thought the strip could move in that direction if it was gag-a-day rather than adventure stories. London told Dueben that he was being “pressured to redesign the entire series to look like ‘Popeye & Son’" But London wouldn’t go along, he said (in italics)—: And refusing to do so probably cost me my job. I defended the sanctity of that strip, I didn't destroy it. I was twenty years old when I created Dirty Duck, and I stuck with him because I knew he was this timeless character -- he had one foot in the past, one foot in the present and his butt in the future. That sort of equals timelessness. I knew I could bring that same quality to Popeye if I could just overcome all that ill will. Popeye was very much of his time. He talked about the Depression, fascism, unions, gangsters, short skirts, politics. I wanted the average reader to relate to him again. I certainly wasn't afraid to draw a cell phone or ATM machine, because the way I would draw a cell phone or an ATM machine would look exactly like a Popeye version of a cell phone or an ATM machine. He was in good hands because I left him alone. I had him walking around in that same old suit, and the party girls would say, "He's so punk!" There's no difference between what I did and having him fight gum card monsters from the 1950s, but, no—they hated it. They would rather have had him in a Hawaiian shirt, a baseball cap and little blue shorts. You cannot change Popeye, kids. He is the one constant in an ever-changing universe. His credo is "I yam what I yam, and tha's all that I yam"— how can he go against his own credo?! Sure, you can put him through costume changes for story purposes, but take away his pipe forever? Even his bloody theme song has a pipe. Well, they can all rejoice. I'm not in the Popeye business anymore. They can do whatever they want with him now, it's all the same to me. But as long as I was the proprietor of Elzie Segar's newspaper strip, that wasn't gonna happen. Not on my watch. No, sir. “Popeye and Son” lasted only thirteen episodes. But King Features’ effort to make the comic strip echo the animated version poisoned the relationship between the syndicate and London. Said London: “The Popeye daily died the day they ordered me to make it look like ‘Popeye & Son.’" But that wasn’t the only poison pill in the stew. London wanted to do the Sunday Popeye and felt he had been promised the opportunity—and then King reneged. London was understandably resentful, as he explains (in italics)—: When I first went up there, [London told Deuben], I had asked for an option on the Sunday page when Bud retired; they told me that if I behaved and proved my worth, I would get it over time. That was the promise my first editor had made to me; when I brought the subject up again five years later, the second editor reneged on that promise, in a very insulting and passive-aggressive fashion, I might add. I was stunned and I didn't know what to do at first, so I did nothing for a long time. [Sagendorf was only semi-retired: while London did the dailies, Sagendorf was doing the Sunday Popeye and would continue doing it until he died in 1994.—RCH] People who really know me know that deep down inside, I'm an honorable person who's as good as his word, depending upon what that word is, of course; but their promise had been broken and all bets were off, so I wrote the "Stupid Little Hat" story. When they called and said stop writing stuff about a licensing execs and go back to Popeye punching Bluto, I said, Okay, I promise I won’t write about the licensing guy anymore— then I turned around and wrote "Witch Hunt." The rest you know. Years later, I read somewhere online that they had no intention of ever giving me the Sunday— that they promised it to Hy Eisman before they even hired me, so my instincts were correct. To stay on board after all those years of hard work and not be chosen to draw the Sunday page would have been far more humiliating to me than getting fired on a slow news day and being all over the media for 24 hours. And, then, of course, there were the financial losses in being denied the Sunday page.

FOR THE REST OF THE STORY (plus some other, interesting asides), I’m quoting some of the Deuben/London interview verbatim—Deuben’s questions/comments in bold face; London’s in everyday roman type. Deuben begins by asking about the last six weeks of the strip that are published for the first time in the second volume of IDW’s London Popeye reprints, Thimble Theatre Presents Popeye: Classic Newspaper Comics, 1989-1992.

In the last batch of strips that were never before published and that people are seeing here for the first time, you wrap up "Witch Hunt" and end like you did with Jeep saying goodbye— did you know that would be your last strip? Well, sure. Of

course. I had already been dismissed, and they said you have four more weeks to

fill out, so I knew they would be my last strips. I wrapped up the Roe v. Wade

story as best as I could according to my original outline and said my goodbyes.

Those strips were flatly rejected, and they've been sitting in my files ever

since.

I'm sorry. They fired you—publicly— and then said you're still under contract for four more weeks of strips? Yes. They fired me and said, Oh by the way, you have four more weeks of your contract to fill out, and you're gonna do these strips whether you like or not.

[Laughs] And then they rejected those strips, which they made you draw. Yes, Kafka-esque, ain't it? I said, so what? You already fired me! What are you going to do, fire me again? [Laughs]

I'm laughing because it's a different experience from most of us who have been fired or laid off. I've been through worse. At least it makes for a very nice book.

It does. The book reads well and it ends nicely. Looking back at the strips, 20-25 years later, how do you feel about the work? I think they hold up great. It really doesn't matter if people don't remember who Milli Vanilli was. I mean, so what? Go look it up. For every Milli Vanilli reference in there, there's a Pete Townsend or Willie Nelson reference. Those people are forever! If Harpo Marx can be in a Popeye cartoon, why not the Beatles? I guess I knew that there wouldn't be a Mount Rushmore-type monument to poor Milli Vanilli anytime soon, but I was trying to be absurd. I try to go for the absurd as much as I can— the same way Segar did. The way Stan Laurel did! Like Cervantes! Jonathan Swift! Rabelais! Willy Elder! When I first took the strip on, there were people who said, who do you think you are? E.C. Segar created what is arguably one of the greatest comic strips in the history of newspapers. Who do you think you are to try to top him? Well, I know who I am— at least part of the time— and I wasn't trying to top E.C. Segar. I figured the only way I was going to get through it was to be myself. And may I say, I got as close to the original with that final story as anything I'd ever written by being myself. I think they proved they'd have fired E.C. Segar if they had half the chance. When you consider the lengths the Reagan Administration went to in those days to to demonize liberals in the media, and the unfortunate results on the evening news for even children to see, my little cartoon story had the Lubitsch Touch by comparison. All of it, from start to finish, was first rate. I have no regrets and clearly, neither does King Features, otherwise they wouldn't have published it all in two delightful volumes. Of course, they had twenty years to think it over.

You've had some strange experiences as a cartoonist, and you'd been working as an artist for many years by that point, but after being fired like that, was it hard to get back into things and draw again? No, I kept drawing all the way through it. I drew myself getting kicked out of King Features for Time magazine, and I was back drawing for the Op-Ed page of the New York Times. The publicity got me a lot of offers. My friends at Disney gave me work. My face was on television, so people recognized me in restaurants for a while. I became a gym rat, working out three days a week. But my mother was sick, she went into a rapid decline not long after that, and I spent most of my time looking after her in her last days. When that was over, I went back to work full time. I called the offices of MTV and they said come on up— we don't have anything for you, but maybe someone else does. Chris Duffy, who was comics editor of Nickelodeon magazine, picked up a family strip I originally created when I was 12. I had used the characters in my New York Times illustrations, but the strip version had been rejected by the syndicates long before and then immediately after I did Popeye. Chris Duffy and the editors of Nickelodeon liked it and ran it on a fairly regular basis until they ceased publication a few years ago.

Is there a chance that we'll see a new collection of Dirty Duck or some of your other work one of these years? If you don't, you'll know who to blame.

What are you doing now? Well, as you know, in 2000, I went West, young man, and drew storyboards for Cartoon Network and character concepts for the first Spongebob movie. It was cool with all of those generous, open-minded folks in Hollywood for me to do that between Dirty Duck strips and Nickelodeon assignments. Unfortunately, one particular producer at Disney chose to pressure me to quit Playboy before I could work on his show. That would have meant quitting my own characters, and I just couldn't do it. I've been with Playboy since 1976. It was funny how there were other comic book artists they didn't ask that of.

People have issues with Playboy for many reasons, but I've heard a lot of very good things from cartoonists over the years. Obviously, people like Harvey Kurtzman and others worked there, Gahan Wilson has had a great working relationship with the magazine, and Jules Feiffer called Hefner one of the smartest editors of comics he's encountered. Hefner saved the Dirty Duck strip from an ignoble fate back in the 1970s, so I'll always be thankful to him for that. The blogs say he left me "high and dry" during the Reagan Era, but that's simply not the case. They offered me a full page but I took a half. It was my decision. I'm just amazed at the things people say. About ten years ago, they had a general manager who wanted to get rid of all the cartoons and make it look more like Maxim. They fired him pretty quickly. They chose their artists over a suit. I couldn't very well leave them after that. I don't understand the problems that people have with Playboy at all, and I don't want to get into first amendment issues, okay? I don't wage wars, I draw funny pictures.

RCH: I remember that guy who wanted to make Playboy into Maxim. Yes, they fired him. But then they hired another guy who, to judge from the recent demise of Playboy, finally did the conversion.

Another fitnoot: I ran into the late Jay Kennedy in the fall of 1992, months after the London firing, and I asked Jay if he wanted to add anything to the prevailing reports. King Features had been portrayed pretty universally as the corporate bad guy; so did he want to do anything to set the record any straighter? What was the syndicate’s side of the story? Kennedy declined to elaborate beyond the official statements that had been made at the time of London’s firing. He was fired because his work was no longer acceptable. Given the timing, it was assumed that the Bluto baby episode was the cause. And Kennedy said nothing to correct that impression. I had the sense, though, that Kennedy—whose involvement with underground and alternative press cartoonists was long and cordial—was a little embarrassed and very much wanted the whole thing to go away without further ado. If the abortion sequence were to run these days, probably nothing would come of it. Syndicated comic strips today have joked about a number of previously taboo’d matters. These are simply freer times. But in 1992, as London discovered, the leash had not yet loosened much.

BY THE WAY,

that collection of Dirty Duck alluded to in the foregoing? It’s happening

this summer. IDW is bringing out

GOSSIP & GARRULITIES Adam Minter, a columnist for Bloomberg View, reports (May 12) that the federal transportation security apparatus, TSA, found 25,000 security breaches at U.S. airports between 2001 and 2011. That’s 2,500 a year or seven (7!) every day. And last year, Homeland Security investigators achieved a 95 percent success rate in smuggling mock explosives and weapons through TSA checkpoints. Makes you wonder, as we do frequently about Congress, why we have it—and why we continue to take off our shoes to get clearance to board an airplane.

EVERYBODY got all wee-wee’d up at the news that United Healthcare, the nation’s largest health-care insurer, is leaving most of 34 states in which it offers plans on the Affordable Care Act’s public exchanges—citing the $650 million it is projected to lose on those exchanges in 2016. Doom-sayers predicated UH’s departure as the canary in the mine signaling the end of Obamacare. No one mentioned that another insurer, Cigna, plans to expand its Obamacare offerings into more states in 2017.

AS FOR THE BATHROOM BROUHAHA, Frank Bruni in the New York Times said “it’s a tempest in a toilet,” going on to observe that transgender people have been going to the restroom of their choice for years without incident. Without telling anyone, either, I’d say. Potty pandemonium indeed.

PITHY PRONOUNCEMENTS Warren Bernard, an avid collector and longtime lecturer on the history of editorial-political cartoons and editor of Cartoons for Victory (reviewed in Opus 346), was asked recently at historynet.com how “effective cartoons are in shaping wartime public opinion. To which Bernard said: “The history of the United States is full of examples in which cartoons played a big part in mobilizing support for war. During the Civil War, Thomas Nast’s cartoons in Harper’s Weekly, especially his Christmas cartoons, put a bright light on the sacrifice of soldiers. President Abraham Lincoln called Nast ‘the best recruiting sergeant the Union ever had.’ “In the 1890s newly developed color Sunday cartoons in the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer drummed up support for what became the Spanish-American War and gave us the term ‘yellow journalism,’ for the color of Hearst’s comic character the Yellow Kid. “In World War I, the Woodrow Wilson administration created the Committee on Public Information to influence the American public’s view of the war, with a separate cartoon division that sent out ideas for the nation’s cartoonists to incorporate. During World War II the War Bond Division of the Treasury Department syndicated its own cartoons about war bond drives to the nation’s newspapers, while the Office of War Information had cartoonists create syndicated works on such topics as rationing, scrap drives and women in the armed forces. “In neither world war, as a rule, did the nation’s political cartoonists criticize the war itself. But the Vietnam era brought a different tone to the political cartoon world, as a number of prominent cartoonists—such as the widely syndicated, Pulitzer Prize–winning Herblock—did not support the war.”

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

POTTY HUMOR, as we’ve been at great pains to demonstrate for several years, is now fully accepted in newspaper comic strips. The once tabooed topic is pooping up everywhere (and we’ll look at some more instances in a trice). Sex, however, hasn’t made comparable inroads. Although it’s working at it. In Francesco

Marciuliano and Jim Keefe’s Sally Forth, the eponymous

heroine goes on a “date” with her husband, Ted. Maybe it’s their wedding

anniversary. I’ve forgotten (or wasn’t paying attention). In the uppermost

strip in our first visual aid, table talk at the conclusion of their dinner

veers off in the direction of the bedroom—but subtly enough that only adults

and dirty old men (like moi) get it. In the next Sally Forth, we have mere romantic whisperings on the couple’s way home. Sentimental and romantic. And nice. Then, once they’re home and walk into the house, their connubial plans go awry immediately when faced with a daughter and her plans. In Rhymes with Orange, Hilary Price alludes to the feverish disrobing that once accompanied a dash upstairs to the bedroom: the couple is reminded of their lost lust by seeing their children’s duds strewn all over the stairs. Finally, in Tom Batiuk’s Funky Winkerbean, Cindy is climbing into bed with her current beau (whose name, like that of most of the characters in this strip, evades me) who is a movie actor. Is she promising a roll in the hay? “Fireworks”? Looks like it. But even if not, these two sharing a bed seems risque. They aren’t even married, are they? Is this pre-marital canoodling? If so, probably a first. (No—second. In Doonesbury, Garry Trudeau had an unmarried couple in the sack a few centuries ago. It was a famous sequence taking two or three days as a camera moved in to a building, a window in the building, and then into the bedroom. Or so I remember, without checking.)

WITH OUR NEXT

EXHIBIT, we’re back to potty humor. (Just to demonstrate that it hasn’t gone

away.) In Mike Peters’ Mother Goose and Grimm, Grimm is licking

his balls (or his butt), something no comic strip dog would do in decades past. In Scott Adams’ Dilbert, Dilbert and an office pest go into the men’s room and apparently wind up in the same stall. Not as risque as licking your balls, I realize; but restroom stalls were on the verboten list for years, too. In Frazz, Jef Mallett has the kid use a word that sounds and looks at good deal like “farted.” Means the same, too. And in One Big Happy, Rick Detorie’s Ruthie corrects her friend’s misunderstanding of the meaning of “windbreaker.” (Farded and breaking wind both having to do with flatulence. Oh, you knew that, right?) Potty humor all around.

STEPHAN

PASTIS (who is up again

this year, for the 8th time, for the Reuben Award as “Cartoonist of

the Year” for the National Cartoonists Society; to be determined this coming

Saturday at the Reuben Banquet) has a well-deserved reputation for constructing

elaborate puns (the lowest form of humor as one wit saith) and other forms of

wordplay in his The last strip at the bottom of the display is the only one in which visual content acts to provoke the laugh. Wordplay isn’t the essence here. I’m including it because it’s another example of how Universal/Uclick’s comics editor, John Glynn, gets his name in the papers. Oh—the lowest form of humor is that which is the foundation upon which all other jokes depend. So puns ain’t bad, aristotle.

OUR FINAL

DISPLAY begins with more unmentionables, starting with Mike Peters’ Mother

Goose and Grimm, which depends for its comedy on our knowing that dogs

“read” trees and other such objects for “signs” of other dogs’ presences. The

signs are a residue of canine urine, remember? At the bottom of this exhibit are two Dilbert strips not drawn by Scott Adams. They’re drawn by Jake Tapper, chief Washington correspondent for CNN and host of “The Lead” on tv. Adams wrote the strips but Tapper drew them. Adams has had “guest artists” on the strip recently so maybe another one isn’t a surprise. We may not be surprised, but Adams was. He was appearing on Trapper’s tv show where Tapper expected to have an interesting discussion about Donald Trump. What happened next is described in the Charleston Gazette-Mail. “We were chatting during the commercial break,” said Tapper, “and I let it slip that I was a failed cartoonist.” Adams, who has been resting his drawing hand of late, pounced on the admission and invited Tapper to draw a week’s worth of Dilbert. Adams would write the strips; Tapper would draw. Before Tapper found success as a journalist, he drew cartoons for the Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Philadelphia Inquirer, Roll Call and Washington City Paper. He once demonstrated his caricature chops by drawing Bronco Bama on an easel in front of a gaggle of editorial cartoonists at the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. Not bad. (I was there.) Tapper’s interpretation of Dilbert is running the week of May 23 through Saturday, May 28, a significant date in the year’s cartooning. That night, members of the National Cartoonists Society will award their Reuben trophy to the person deemed “Cartoonist of the Year,” during a banquet at the NCS meeting in Memphis. Tapper will not get the Reuben: he wasn’t a well-known failed cartoonist until this week, too late to enter the competition. “I think readers will enjoy seeing [Tapper’s] take on the art, which came out great,” said Adams. “He’s way better than I expected!” But his rendering of the Dilbert cast is, as you can plainly see, deeply at variance with the way Adams draws. It may even be an improvement. More lines anyway. The one-of-a-kind strips will be auctioned off to raise money for Homes for Our Troops, an organization that builds mortgage-free, specially designed homes for the most disabled veterans from Afghanistan and Iraq.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv.

A 10-foot-high statue of Hercules in the French town of Arcachon has been fitted with a removable penis to thwart vandals, who’ve been stealing the hero’s member with alarming regularity since the statue was, er, erected in 1948, saith The Week (May 6). To prevent future episodes of castration, town officials commissioned a removable prosthetic that will be attached to the statue’s groin for special ceremonies in the part—and removed right after. The very thought of a removable dick makes me cringe. A prosthetic pecker? In this day and age? When some enterprising doctor has just managed the first penis transplant?

BOOK MARQUEE Previews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we do here, starting with—:

America In Cartoons: A History in Pictures Edited by Tony Husband 192 7x10-inch pages, b/w; 2015 Arcturus hardcover, $16.95 ($5-10 Amazon) HUSBAND, the

editor of, now, a 3-volume series of history books of editorial cartoons, is a

British cartoonist, whose works are sampled just at the elbow of your eye. But the historical aspect of the work is admirable. Every cartoon is captioned with background information that explains the context and therefore the original purpose of the cartoon. A few British cartoons are included for their peculiar awareness of facets of American history, but by far most of the work here is by Americans. The first half of the volume covers the colonial era through the 1800s, which lends the book a 20th century emphasis because that’s the focus of the remaining half of the book. There is, alas, no index. With his British perspective, Husband brings up matters that are not likely to be discovered in American histories of this sort, offering thereby insights we otherwise lack. A cartoon about Mark Twain and copyright law, for instance—and Oscar Wilde’s visit to the United States, Thomas Edison’s greed, a horse-drawn traffic jam in New York City, the Gold Rush to California. He includes some fascinating minutiae. In the caption for a cartoon about college football, he observes that in 1905, there were 18 deaths on the gridiron. On the other hand, he doesn’t include much about the Civil War—or about President Lincoln, one of the most caricatured personages of the 19th century. A few of Husband’s observations are questionable. In one caption, he says that the experience of the Salem witch trials “led Americans to be wary of including religion in the Constitution.” There were other contributing factors to this Constitutional decision even though the tendency of religion to foster zealotry is doubtless one of them. Husband offers Betty Boop as a “symbol” of the Depression era. And he repeats the etymological canard that “blue laws” acquired their characteristic hue because they were printed on blue paper. Or in books bound in blue. Not true. The origin of the expression “blue laws” to disparage laws enforcing rigid moral codes is cloudy. Some say “blue laws” derive from “blue nose,” a term denoting a person who advocates extreme moral rigor. The term was first used in reference to Connecticut’s laws. The northeastern states were colder than many others, so residents in that vicinity might have “blue noses” because they were cold. Others say “blue-stocking” is the seed from which the noxious plant grew: in Britain, Oliver Cromwell’s “little Parliament” of 1653 was sometimes called a “blue-stocking” Parliament, but that referred to its common rather than aristocratic members (who wore white stockings), not so much to moral attitudes. My guess is that “blue” became a euphemism for “bloody,” a term of disparagement. “Bloody laws” referred to laws that many disliked, but “bloody” was a socially unacceptable allusion to “by Our Lady,” a possibly blasphemous oath alluding to the Virgin Mary, so “blue” was substituted for “bloody.” But I find no support for this theory among the etymologically adept. Many of the cartoons are not, strictly speaking, editorial cartoons, and many of the artists included are not, strictly speaking, editorial cartoonists— Frederic Remington, Harrison Cady, Rea Irvin, Oliver Herford, Winsor McCay (his Little Nemo). But the book, after all, is “history in pictures,” and artists like the aforementioned provide insights into that history. The work of Thomas Nast is among the most frequently displayed, but not many of his cartoons herein are the more familiar ones. Joseph Keppler, Clifford Berryman, Daniel Fitzpatrick, and Bob Englehart, are represented by more than one cartoon. But there’s only one by Homer Davenport and none by J.N. Darling (“Ding”). For all its minor flaws, however, the book makes a valuable contribution to understanding American history and to the history of editorial cartooning. It’s also fun to look at the pictures, some of which are posted nearby.

Dictators in Cartoons: Unmasking Monsters and Mocking Tyrants Edited by Tony Husband 192 7x10-inch pages, b/w; 2015 Arcturus hardcover, $16.95 ($5-10 Amazon) THE FOCUS is on 20th century dictators with chapters on Mussolini, Stalin, Hitler, Franco, and Mao Zedong, but a 38-page introductory chapter dips deeper into history, beginning with Roman emperors Caligula and Nero and continuing through Vlad the Impaler and then skipping ahead to Napoleon and czars of Russia and World War I’s Kaiser Wilhelm III, and including Charles Philipon’s pear-shaped caricature of the face of French king Louis-Philippe (without, sadly, explaining that the portrait was a visual pun: the French for “pear” meant “imbecile” or “simpleton” as well as “pear”). As in previous Husband books of cartoons, many of the pictures (particularly in the first chapter of ancient history) are reproduced by half-tone, a maneuver that sometimes grays and blurs an otherwise crisp black-and-white line drawing. In this book, however, lots of the pictures are “drop-out” half-tones, a process that eliminates the graying of otherwise white background. Most of the cartoons are allotted a full (or at least a half-) page, which displays even half-toned drawings in sufficient detail; but one or two cartoons are reproduced at the disappointingly diminutive dimension of a postage stamp. Why include such tiny pictures at all? We can’t see enough to make sense of them. Captions explain every cartoon by giving them their historical context; and many are dated (by year, at least). But the book lacks an index. As in Husband’s Cartoons of World War II, many, but not all, of the cartoonists are British or European. The most frequently represented are Bernard Partridge, E.H. Shepard, and Arthur Szyk, and Americans Clifford Berryman, Daniel Fitzpatrick, and Herblock (with several cartoons I’ve never seen before despite the numerous books devoted to reprints of his work). Apart from the scraps of history Husband imparts, the pleasure the book affords is chiefly in the ingenuity of the cartooning, a few samples of which are posted herewith.

Black Hand Comics By Wes Craig 104 6x10-inch landscape pages, b/w and color; 2014 Image hardcover, $19.99 THE TITLE REFERS neither to African or African-American art nor to some branch of the Italian Mafia but to tales of supernatural horror—exactly the sort of thing that usually turns me off before I get fairly going. And here it isn’t the stories that engage me but the artwork from the co-creator of Image’s Deadly Class, who has taken three of the stories from his webcomic (blackhandcomics.com) and bound them together between hardcovers, a presentation that might tempt one to think this book could qualify as a graphic novel except that the content isn’t one narrative but three: The Gravediggers Union, Circus Day, and The Seed. In the first story, gravediggers’ duties extend into the night so they can make sure the bodies they’ve interred during the day stay dead; in the third, a man is running from something inside himself until it finally breaks out, Alien-style. Neither of these particularly engages me, but the third tale, “Circus Day,” isn’t supernatural at all: it concerns a boy’s experiences at a circus. The attraction in Craig’s work is in the inventiveness of his artwork. All the tales are drenched in black, which he accents with flashes of white or color. The panels appear against a black background. Black black black. And the format of the book dictates the size of the artwork—mostly tiny. Tiny images but inventively concocted and deployed. A treat for the eyes, as the accompanying excerpts might, I hope, convince you.

PERSIFLAGE AND BADINAGE France’s Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games, said: “The important thing at the Olympic Games is not to win but to take part; for the essential thing in life is not to conquer but to struggle well.” Admirable sentiment. Too bad it has been so completely overshadowed by the monetary and drugging issues that have so thoroughly corrupted the Olympic ideal.

GAGGING WE SHALL GO Single-panel Gag Cartooning NOW THAT PLAYBOY has deserted single-panel gag cartooning in favor of—what? Short articles in front of the magazine? Better white space?—The New Yorker is the only remaining reliable venue for magazine cartooning. And over the last few years (five to ten), the New Yorker cartoons have gotten better. For what seemed like decades, the cartoons were inert: the captions didn’t illuminate the pictures or vice versa. The captions were simply snatches of overheard conversation uttered by “typical” New Yorkers, who were of the self-satisfied pseudo sophisticate sort. If they were funny at all (rather than simply snide), they were funny without the pictures (if you like that sort of “sophisticated” humor, a staple in The New Yorker for generations). But then, once we were safely into the new century, we started getting cartoons of the “classic”—i.e., fundamental—sort: cartoons in which neither the pictures nor the words made the same comedic sense alone without the other. Here’s a culling from the May 23 issue.

In these cartoons, the pictures “explain” the captions and vice versa. In other words, good cartooning. But this gleaning reveals another new trend in the magazine—a growing number of cartoons with anthropomorphic animals in them. In the issue these come from, fully a third of the cartoons feature animals—these four out of a total of twelve cartoons. And in this issue’s Cartoon Caption Contest, two-thirds of the cartoons involve animals. What’s going on in cartoon editor Bob Mankoff’s head? Does he see a blend of words and pictures more often in cartoons about creatures that don’t usually talk than in cartoons about his fellow human (sic) sapiens? Who knows? Dunno. But we’ll keep on the alert for more symptoms.

NEXT, WE SAMPLE

ANOTHER of The New Yorker’s visual aspects—the spot drawing. The

magazine has always scattered throughout every issue random black-and-white

drawings that have nothing to do with the text columns in I picked these specimens because they struck mine eye as pleasing combinations of black-and-white (with accents of color in Laban’s case). No other reason. Nothing more to see here, so move along.

WITH ALMOST NO OUTLETS for single-panel gag cartoons among America’s magazines, I rejoiced a few opuses ago at the arrival at Time of “chartoons.” These are cartoons because they make amusing sense by blending words and pictures in the definitive manner. But their creator, John Atkinson, claims an additional function for them: they are also like “charts” that impart graphically some scrap

of information that is made more evident by reason of the combination of the visual and the verbal. Here’s a collection of his Chartoons that I clipped from Time lately.

I’m not sure the “chart” part of Atkinson’s formulation is all that illuminating: the information we gain is not of the same order of clarity in revelation as, say, pie charts. But the interdependence of words and pictures is undeniably present. So maybe there’s a future for magazine-type cartooning after all?

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets WHAT FOLLOWS is not, strictly speaking, just a “review”: I’ve included several sidebars of possible interest. So here we go—:

The Complete Peanuts: Volume 25, 1999-2000 By Charles M. Schulz 312 7x8½ landscape pages, b/w throughout; 2016 Fantagraphics hardcover, $28.99 THIS LONG AWAITED VOLUME completes the reprinting of every single one of the almost 18,000 strips created by Schulz between 1950 and 2000. When this project was launched in 2004, proposing to publish two volumes a year until the end of the strip’s run, I crossed my fingers in the hope that the goal could be met. Given the vicissitudes of publishing in the comics arena, I feared it never would. And now it has been. I can uncross my fingers. This volume begins with an Introduction by President Barack Obama (quoted here in full, in italics)—: Like millions of Americans, I grew up with Peanuts. But I never outgrew it. Wherever I lived, wherever I travelled, I could find those three or four panels in the paper each morning. And Charlie, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy, Franklin and the gang brought childhood rushing back. That’s what made Charles Schulz so brilliant – he treated childhood with all the poignant and tender complexity it deserves. He gave voice to all its joys and anxieties – a spectrum of emotions that run from the start of a new baseball season to the anguished “Augh” that comes with losing the big game. He explored the emotions that we too often forget kids feel until we’re reminded that we once felt them ourselves. Hope. Doubt. The exquisite pain of unrequited love. The self-exploration of what it means to be different. The comfortable knowledge that it’s all going to be okay – even if Lucy’s advice isn’t very good. For decades, Peanuts was our own daily security blanket. That’s what makes it an American treasure. In his final strip, Charles Schulz wondered how he could ever forget the Peanuts gang. Thanks to this groundbreaking series of books collecting all of Schulz’s Peanuts strips, the rest of us never will—and we can share our love for the gang with our children and grandchildren for decades to come. The book includes all of Peanuts for 1999 and 2000 (the last strips, too, wherein Schulz says a painful goodbye to his readers), but in the year 2000, Peanuts stopped on Sunday, February 13, the day after Schulz died in his sleep. (The dailies, produced with a shorter lead, ceased on January 3; Schulz stopped working on the strip in December or thereabouts, but he was a couple months ahead on the Sunday production schedule.) Filling out this volume—as well as providing as complete a history of Schulz’s Peanuts and Peanuts-related work as possible— is the complete Li’l Folks, the weekly series of one-panel cartoons that Schulz produced for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, beginning June 8, 1947 as Sparky’s Li’l Folks, and continuing (starting June 22) as just Li’l Folks, ending January 22, 1950. More strips than it’s generally supposed—137 of them. The creative precursor to Peanuts, its inclusion in this volume brings The Complete Peanuts full circle. And Fantagraphics is going beyond the circle, too: a surprise 26th volume is announced for October 2016, collecting all of Schulz’s non-strip related Peanuts art: storybooks, comic book stories, single-panel gags, advertising art, book illustrations, photographs, and even a recipe. Schulz’s widow Jean Schulz will write the Foreword to Volume 26, capping the final volume in a star-studded lineup of contributors to the series with a personal reminiscence of her life with the famed cartoonist. Volume 25 comes with the usual Index at the end. (If you want to know when Tarzan is mentioned in the strip, the Index leads you to September 9 and September13, 1999.) And in place of the short Schulz biography that appears in each of the previous volumes, this one includes a history of Li’l Folks by Gary Groth.

A FEW OF THE CARPERS and belittlers who are never quite content until they’ve pointed out that the gods among us all have feet of clay—a few of these malcontents have delivered their opinions that Schulz’s work in the last decade or so wasn’t as good as it had been before that. He slipped, they maintain. The strip wasn’t so brilliant anymore. One sign of its slippage was that it was the same old formula, day after day. Nothing new. Well, as you might expect, I beg to differ. Without doing exhaustive research, the “library” of The Complete Peanuts permits us to isolate a few new developments over the years. New characters, for instance. Each new character ushered in another strain of comedy. Peppermint Patty offered humorous insights into America’s flawed educational system, beginning August 22, 1966—sixteen years into the 50-year run of the strip. And Patty’s buddy Marcie enhanced Patty’s comedic persona when she showed up two years later, June 18, 1968. Rerun came along March 26, 1973, and Spike, Snoopy’s lonely brother in the desert, arrived on August 134, 1975. And there were numerous other characters who arrived after that—and even into the 1990s. The fresh crop of jokes that could be harvested from each new personality may not seem like all that much difference: Peanuts has always been a character-driven strip, so a new character may not change the essential ambiance much. But in 1988—38 years along the Peanuts-strewn pathway—Schulz effected differences of a sea-change sort. In early 1988, he abandoned the strip’s rigid adherence to a four-panel daily format. He started doing 3-panel strips. And on April 2, 1988, he did the first one-panel strip. Then two weeks later, on April 16, he did the first two-panel strip. The scoffers and belittlers may scoff and belittle, pointing the finger-bone of scorn and saying such changes were minor and of little consequence. Again, I beg to differ. Changing the number of panels changes the pacing of the humor. The comedy in a one-panel strip is different than the comedy in a four-panel strip. Schulz’s one-panel strips tend to be more thoughtful. Or, perhaps, more puzzling. And when Snoopy is among the characters assembled, a note of poignance is stuck. He doesn’t seem to understand the situation the other characters are discussing. Typical dog behavior, perhaps, but a different kind of humor. A new kind of humor. And once Schulz had broken the four-panel mold, he seldom returned to it. And he varied the formats, switching back and forth from three panels to one to two and then three for several more days. Hereabouts are samples from The Complete Peanuts for 1988 and 1998 and a few from 1999.

THE DESIGNER for The Complete Peanuts, the Canadian cartoonist Seth (whose actual name I’ve forgotten but “Gregory Gallant” sounds right), agrees with me. Peanuts never got tired or worn out. It constantly renewed itself, he says. What became clear to Seth as he pored over the decades of the strips is “how the strip morphed over its five decades,” says Michael Cavna, who interviewed Seth at Comic Riffs. “Each decade, he almost reinvented the strip,” Seth said of Schulz, who launched the strip while in his 20s. “There were the same characters, but he could have retitled it [at different points]. There were very distinctive flavors. The last 10 years and the first 10 years are tremendously different, and the last 10 years and the ’70s are different. “Schulz was a different person and he was getting older,” Seth continued, noting that the latter strips had a somberness that was less leavened by a younger man’s buoyancy and pacing. And that evolution — that ever-changing nature of Peanuts as an honest organic creation resonating with its own “life” — is crucial to the brilliance of the strip. “If Peanuts had been frozen in time” creatively, Seth says, “we wouldn’t still be talking about it.” The adventure for Seth began shortly after Schulz died in 2000. Seth started right away longing for someone to publish all of Peanuts. Once when working with Gary Groth, Fantagraphics publisher, Seth voiced a wish: if anyone ever published the entire Peanuts, he’d like to design it. Then one day the phone call came from Groth, and soon he and Seth were traveling to Santa Rosa to talk with Jean Schulz, the cartoonist’s widow, about the forthcoming project. Says Cavna: “A nervous Seth worked up a talk to convince her that he was just the man to design this Peanuts set — that he had ‘deep respect for the work’ and that he thought of the Peanuts creator as an inspiration. He was soon assuaged by Jean and their smooth meeting of the minds, which he calls ‘a really meaningful experience.’ “Also a profound experience has been designing the set’s final volume,” Cavna continues, “for which Jean will write the Foreword.” “This volume is basically an appreciation of what the strip meant to me — and how meaningful it’s been for me to be connected to it — to get the work, and the series, in print,” Seth told Cavna. “It’s been a tremendously important thing for me.”

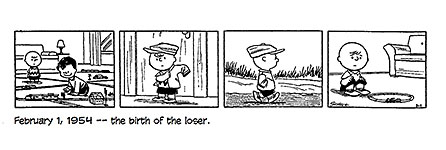

AND WHILE WE’RE

OUT SURVEYING the goober harvest, we finally came across the strip that Stephan

Pastis says is the watershed Peanuts. This strip—the release for

February 1, 1954—is the one that inaugurated the “loser” aspect of Charlie

Brown’s personality.

MOTS & QUOTES The next revamped title from Archie Comics is Betty and Veronica, which will be written and drawn by renowned good girl artist, Adam Hughes. He was interviewed in the most recent issue of Previews; excerpts—: “Archie Comics inquired if I wanted to be involved with the new Betty and Veronica, and I asked if I could write and draw the book. After they got up off the floor, they agreed. “All I care about on Betty and Veronica is making people have some kind of emotional response. Mostly laughing, maybe one or two tears. Whatever I need to do to pull that response from the readers—nostalgia, uncharted territory—whatever!” Asked how he got “into” the heads of Betty and Veronica to “hear their respective voices,” Hughes said: “I get into Betty’s head by blindly trying to see the best in people, no matter what. I get inside Ronnie’s head by wondering what they’re really up to, the sly devils. ... I approach their relationship this way: to me, Betty would never admit to hating anyone; she just can’t. Veronica would find it hard to tell someone that she loves them: she’d show it, but the words would catch in her throat.” There’ll be about 25 alternate covers when the book debuts with No.1 in July.

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Called Graphic Novels for the Sake of Status

Bernie By Ted Rall 208 5x7-inch pages, color; 2016 Seven Stories Press paperback, $16.95 IN THE AFTERWORD, Rall says, “After a person is radicalized, whether they’re motivated by disgust at unfairness or a strong desire to fix a problem, they’re presented with a choice between two roads: the way of the rebel and that of the reformer.” In his previous tome, Snowden, Rall extolled the way of the rebel; here, he champions the way of the reformer, Bernie Sanders. We reviewed Snowden in Opus 348, so it’s no surprise to discover that here again, with Bernie, Rall recasts history to fit his own perceptions of how the world is wending. I don’t fault him for this maneuver—we all do exactly as he does here: we see events of the past through the eyes of our experiences, and that can’t help but give an otherwise objective history a tilt it probably doesn’t actually have. The book is divided into two sections: the first third rehearses political history in this country since 1973; the last two thirds presents us with Rall’s idea of Bernie, a politician the cartoonist admires. The year 1973 is pivotal, Rall says: that was the year after the Democrat candidate for Prez, George McGovern, lost to incumbent Richard Nixon in “the biggest landslide in American electoral history.” Holding a post-mortem on the Election—just as the Republicons did after losing to Bronco Bama in 2012—the Dems decided that they lost because the country was leaning right, not left. Unlike the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm in the years after 2012, the Dems actually followed their own prescription for future victory: they turned right. In his hawkishness, Jimmy Carter is more conservative than liberal, but when he loses to Reagan in 1980, the Dems decide he was still too liberal: “We need a conservative Democrat,” they decide. And, ipso facto, Rall says, “ostracized by the party leadership, lefties are out in the political wilderness.” (Rall himself is a leftie, crying in the wilderness.) That is an understandable view of the political landscape 1973-1980. But when Rall says that when “Carter ignores the threats of Iranian revolutionaries” and admits the ailing Shah of Iran to a hospital in New York, his action “prompts radical students in Iran to take over the U.S. Embassy in Tehran” and hold Americans hostage for 444 days, methinks Rall is simplifying history just a tad. Surely, it wasn’t just Carter’s treatment of the Shah that caused the take-over; surely, there were other factors—chief among them, the Shah’s absence from the locale. The students would presumably not have dared so defiant an act if the U.S.-supported Shah were present in the country to impose his will. Maybe that’s what Rall is saying, too, but it also seems as if he’s saying that Carter’s action not the Shah’s absence provoked the take-over. The Iran hostage situation makes Democrats “appear weak on foreign policy, traditionally their political Achilles’ heel. Carter’s popularity erodes,” and he loses the 1980 election to Reagan. Liberalism has been ousted from the Democratic Party. Political debate in this country, Rall maintains, is thereafter between center-right and right-right. The GOP rules right-right for 12 years; when Bill Clinton wins in 1992, he does so by being pro-business and by leaning “right.” Leftie Rall doesn’t like Clinton, whom he calls DINO—Democrat In Name Only. Nor does he like Obama, who, he says, broke his promises—among them, his pledge during the 2008 campaign to create a “single payer” option for health care; instead, we have Obamacare. And when the Occupy Wall Street movement gets going, “Obama’s Department of Homeland Security coordinated a simultaneous series of violent police attacks to eradicate the Occupy movement” (Rall’s emphasis)—a leftie movement that, because of the traitorous Democratic Party, has no political home. I don’t remember the law enforcement reaction to the OWS movement being all that violent. Yes, the use of force—or the show of force—was sometimes necessary to remove Occupiers from the places they occupied. But “violent attacks”? Is any use of force—any appearance of force—necessarily “violent” to Rall? Well, no matter. Once you grant Rall the license to distort history to suit his rhetorical purposes—which, you’ll remember, I did at the beginning of this disquisition—you can’t complain. And I’m not complaining: I’m merely pointing out that Rall, as a historian, indulges his own biases and beliefs to the neglect of certain unattractive facts. As do we all.