|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 351 (April 30, 2016). We finish the month with a list of the nominees for NCS’s Reuben and Silver Reuben awards, Jack Ohman’s Pulitzer, Nick Sousanis’s Lyn Ward win, banned graphic novels, and reviews of first issues of New Black Panther, New Moon Knight, Waid/Samnee’s New Black Widow, and an essay on Comic Books Corrupted by Movie Versions and book reviews of Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics, Vols. 1-3; Mandrake the Magician: Sundays, 1935-37 (with Sidebar on The Phantom); Balls of Fire: More Snuffy Smith Comics; and graphic novels Drama, Indeh: The Story of the Apache Wars (out in July), and Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen and more — plus the usual appreciation of the month’s editoons and farewells to The New Yorker’s William Hamilton, Dick Hodgins, Jr., Paddington’s Peggy Fortnum, and Mad’s Lenny “The Beard” Brenner. And more, much more. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order, beginning with the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists’ plan to assault North Carolina’s Restroom Law by going to North Carolina—:

NOUS R US Political Cartoonists to Meet in North Carolina (just to stick it to the restroom law) THE AWARD SEASON—: NCS Reuben Nominees plus Silver Reuben Nominees Jack Ohman Wins Pulitzer Ditto The New Yorker Lynd Ward Winner: Thinking Visually Zunar’s Case Rejected Two Graphic Novels Make Top Ten Banned Books Lynch at the Ireland Clay Geerdes Website

ODDS & ADDENDA Free Comic Book Day Megyn Kelly to Interview Trump Playboy’s May Issue—Another Dud Fantagraphics Nominated for 17 Eisners —More Than Anyone Else Garfield’s Jim Davis, Adjunct Professor at Ball State New First Folio Found

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE First Issues Reviewed—: New Black Panther New Moon Knight (Comic Books Corrupted by Movie Versions) American Monster Waid/Samnee’s New Black Widow Mockingbird Gwenpool Power Man and Iron Fist Rough Riders

EDITOONERY An Appreciative Look at the Month’s Political Cartoons —including The New Yorker Monthly Political Cartoon Newspapers Tom Toles Talks Shop

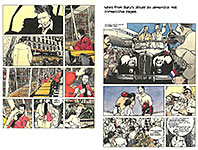

ACCRETION OF INTENTION DEPARTMENT Road to America graphic novel

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Notable Events in the Funnies —and Taboos Broken, Willy Nilly

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews of—: Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics, Vols. 1-3 Mandrake the Magician: Sundays, 1935-37 Sidebar on the Phantom Batman Noir: Eduardo Risso Balls of Fire: More Snuffy Smith Comics Forthcoming—: The Fun Family (aka “Family Circus”) Nobody’s Fool (by Bill Griffith)

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Graphic Novels Reviewed—: Drama Indeh: The Story of the Apache Wars Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Bill Holman’s Smokey Stover (a single magnificent panel)

ONWARD, THE SPREADING PUNDITRY Building Trump’s Wall

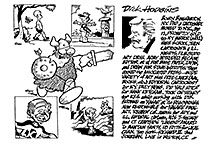

WE’RE ALL BROTHERS PASSIN’ THROUGH The New Yorker’s William Hamilton Dick Hodgins, Jr. Peggy Fortnum (Paddington’s “Mother”) Mad’s Lenny “The Beard” Brenner

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Political Cartoonists to Move Forward with North Carolina Convention DURHAM, NC — Amid the wave of job losses and high-profile concert cancellations in North Carolina, there is finally some good news for its beleaguered governor and state legislature. One group has decided not to pull its upcoming convention in the wake of the controversial law HB2: Political Cartoonists. Pat McCrory and the GOP-controlled legislature will be gladdened to hear that the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists is standing firm in their commitment to hold their 2016 Convention and Satire Festival at Duke University in September. "Other groups and companies are boycotting because that is the only way they can express a political opinion," said Adam Zyglis, the 2015 Pulitzer Prize winner for Editorial Cartooning, and current president of the AAEC. "Expressing an opinion is precisely what we do, so I say we should go to the heart of the controversy and speak out on this issue." The upcoming confab, scheduled for September 21-24 on the Duke campus, will gather together a hundred political cartoonists from across the United States and Canada to join with nationally-known comedians and satirists for four days of panels, exhibits and public shows. "Cartoonists and comedians don't shy away from controversy — they embrace it. They run toward it," said festival co-host JP Trostle. "I'm sure Pat McCrory and politicians in Raleigh will be happy to hear we're bringing an entire convention of these people to their doorstep." Zyglis added, "We will be gathering Association members' work on the HB2 issue, and finding ways to showcase these cartoons to the public. [For an indication of what might be displayed, scroll down to Editoonery and watch for Restroom pictures.] We're also talking with the North Carolina Humanities Council on a joint event discussing the different angles and historical relevance of the recent controversy." House Bill 2, also known as "the Bathroom Bill," has generated a nationwide backlash against North Carolina, and state-wide protests both for and against the measure. A reaction to a Charlotte city ordinance that would have allowed transgender people to use public restrooms based on their gender identity, the new law is seen by many people as discriminatory against the LGBT community. It also blocks municipalities across the state from establishing their own anti-discrimination laws or increasing the minimum wage, and strips all workers of their right to sue an employer for discrimination in state courts. HB2 was added to the books after a rare special session of the state legislature, when it was written and signed into law by the governor in less than 12 hours. Legislators were given five minutes to read the bill in its entirety and discuss its merits.

Fitnoot (this one from ABC News)—: Raleigh, NC — At a press conference today, April 21, North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory took further steps to ensure that his controversial bill, HB2, will be upheld when it comes to law enforcement. McCrory announced that his office has setup a 24-hour hotline for individuals to call if they witness someone not abiding by the new law ,“If you see a woman, who doesn’t look like a woman, using the woman’s restroom, be vigilant, call the hotline, and report that individual.” McCrory told reporters. “We need our state to unite as one if we’re going to keep our children safe from all the sexual predators and other aberrant behavior that is out there.” Enforcement by snitching. Well, it worked in Hitler’s German.

***** The Award “Season” is upon us. *****

AMONG CARTOONIST OF THE YEAR NOMINEES, TWO WOMEN The National Cartoonists Society announced five finalists for Cartoonist of the Year, and the list includes two women. NCS also announced the finalists in its division award categories— among them, several women (see the ensuing report, Silver Reuben Nominees). At Comic Riffs, Michael Cavna paused in his reporting to compare the NCS honors to France’s Angouleme Festival, which “tied itself in knots last January when attempting, in response to a ballot backlash, to try to find a female cartoonist it deemed worthy of its Grand Prix lifetime achievement award.” Well, yes. But NCS hasn’t always been so gender sensitive: in its 70-year history, no woman cartoonist won the coveted Reuben trophy, emblem of Cartoonist of the Year, until 1985 when Lynn Johnston won it with her comic strip For Better or For Worse. And then NCS went another six years until Cathy Guisewite won for Cathy. After that, nothing until last year, two decades later, when Roz Chast won. Three women Reuben winners in 70 years—not a record to be inordinately proud of. And for the first several years of its history, NCS was a men-only club. So by recognizing women in this year’s lists of finalists, NCS is launching the merest beginning to make up for past neglect. Other organizations, similarly afflicted with male-centricity, have also recently betrayed better manners, Cavna observed. “The voting window just closed on the Eisner Hall of Fame Awards, for which one-fourth of the 16 inductees and finalists are women.” But ethnic and racial diversity are, alas, in even shorter supply across the landscape of cartooning as well as in various winner circles.

THE FINALISTS

for the Reuben are Lynda Barry (Ernie Pook’s Comeek), Hilary

Price (Rhymes With Orange), Stephan Pastis (Pearls Before

Swine), political cartoonist Michael Ramirez, and Mark Tatulli (Lio and Heart of the City). “I’m really happy about it!” Barry told Cavna in an interview. “And I’m honored and surprised to be in the same category with the other kicka-- nominees. They are real cartoonists — the ones who do the impossible,” said Barry, whose feature ran for decades in alternative weekly papers, “—because doing a daily comic strip actually is completely impossible, and yet they are doing it, which means they must be part magical being, part Time Lord. I love making comics and I love showing other people how to make comics and I’ve been so lucky to have this be a big part of my life.” Here’s a summary of her cartooning career—followed by similar reviews of the work of the other Reuben nominees—:

■ LYNDA BARRY, a cartoonist and writer, has authored 21 books and received numerous awards and honors including an Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from University of the Arts, Philadelphia; two Eisner Awards, the American Library Association’s Alex Award, the Washington State Governor’s Award, the Wisconsin Library Associations RR Donnelly Award and the Wisconsin Visual Art Lifetime Achievement Award. Her book, “One! Hundred! Demons!” was required reading for all incoming freshmen at Stanford University in 2008. She’s currently Associate Professor of Interdisciplinary Creativity and Director of The Image Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison were she teaches writing and picture-making. ■ STEPHAN PASTIS, creator of the daily newspaper comic strip Pearls Before Swine, syndicated by Universal Uclick, practiced law in the San Francisco Bay area before following his love of cartooning and eventually seeing syndication with Pearls, which was launched in newspapers beginning December 31, 2001. The National Cartoonists Society awarded Pearls Before Swine the Best Newspaper Comic Strip in 2003 and in 2006. Pastis is also the author of the children’s book series Timmy Failure. Stephan lives in northern California with his wife Staci and their two children. This is his eighth nomination for the Reuben award. ■ HILARY PRICE is the creator of Rhymes With Orange, a daily newspaper comic strip syndicated by King Features Syndicate. Created in 1995, Rhymes With Orange has thrice won the NCS Best Newspaper Panel Division (2007, 2009 and 2012). Price’s work has also appeared in Parade Magazine, The Funny Times, People and Glamour. When she began drawing Rhymes With Orange, she was the youngest woman to ever have a syndicated strip. Hilary draws the strip in an old toothbrush factory that has since been converted to studio space for artists. She lives in western Massachusetts. This is her third nomination for the Reuben award. ■ MICHAEL RAMIREZ, two-time winner of the prestigious Pulitzer Prize (1994 and 2008) and a three-time Sigma Delta Chi, Society of Professional Journalism Award winner. is a Senior Editor and the editorial cartoonist for Investor’s Business Daily. Ramirez is a Lincoln Fellow, and an honorary member of Pi Sigma Alpha National Political Science Honor Society. He has won almost every major journalism award in America including the 2005 National Journalism Award, the 2008 Fischetti Award, the H. L. Mencken Award and is a five-time National Cartoonists Society editorial cartoon division winner. Michael is the recipient of the prestigious UCI Medal from the University of California, Irvine. Two books of his editoons have been published: Everyone Has the Right to My Opinion and Give Me Liberty or Give Me Obamacare. His work is seen world-wide in over four hundred newspapers and magazines through Creators Syndicate and has been featured on CNN, Fox News, and Fox Business and seen in USA Today, the Washington Post, the New York Times, the New York Post, Time magazine, National Review and US News and World Report. (His caricatures are rendered so thin that their facial features cannot be discerned, but his wit is sharp.—RCH) ■ MARK TATULLI is best known for his two comic strips, Heart of the City and Lio, which appear in 400 newspapers world-wide. He has written three books in a children’s illustrated novel series entitled Desmond Pucket, which has been optioned for television by Radical Sheep. He also has two planned children’s picture books coming from Roaring Book Press, an imprint of McMillian Publishing. The first, Daydreaming, will hit bookstores in September 2016. Lio has been nominated three times for the National Cartoonists Society’s Best Comic Strip, winning in 2009. Tatulli was also nominated for Cartoonist of the Year in 2014, and he was nominated for Germany’s Max and Moritz Award in 2010. The winners will be announced May 28 at the NCS Reuben Awards ceremony in Memphis.

Silver Reuben Nominees. NCS has never quite escaped its status as a drinking club for cartooners rather than as a serious professional organization. It waited for a decade before realizing that the Reuben award wasn’t enough: by recognizing only one “cartoonist of the year” every year and always a syndicated cartoonist, it failed to recognize the work of cartoonists in the other, non-syndicated venues they labored in—magazine panel cartoons, advertising illustration, animation, editorial cartooning and so on. In the mid-1950s, NCS started giving awards in these areas, calling them “division awards”—magazine cartoon division, animation division, editorial cartooning, and also newspaper comic strip division, etc.—and sprouted other divisions as time dribbled by (television animation, sports cartooning, and, eventually, comic books—then graphic novels, then online cartooning). Winners of Division Awards, who receive a silver-looking plaque, are often referred to, casually, as “Reuben winners” even though Reuben winners have always been exclusively Cartoonists of the Year, not Division Award recipients. Division Award winners are “Reuben winners” only in the sense that they receive their plaques at the annual Reuben Award banquet. But it has been confusing. Last year, the NCS leadership decided to incorporate the misnomer into formal language and decreed that Division Award winners should henceforth be termed Silver Reuben Award winners, thereby perpetuating the confusion. This year, 46 cartoonists and titles in 14 categories have been named 2015 Silver Reuben nominees as part of the NCS’s Reuben Awards, which, as Michael Cavna at Comic Riffs says, some consider “the Golden Globes of comics.” (By comparison, Cavna goes on, “many now consider the Eisners the Oscars of the comics industry. That nickname could bode well for Pixar’s ‘Inside Out,’ which is nominated in NCS’s Feature Animation category; earlier this year, the Pixar film won the Golden Globe, as well as the Oscar.”) Some

nominees are finalists in more than one division: Australia artist Anton

Emdin, for instance, is nominated for Newspaper Illustration,

Advertising/Product Illustration and Magazine/Feature Illustration. And he

undoubtedly deserves all three: in MHO, he is the world’s most thorough-going

cartoonist, expert—highly skilled—in any cartooning endeavor he puts his hand

and pen to, including caricature, strip, gag cartooning and illustration—and

always in the spirit of highest exuberance. His style most often evokes Jack

Davis of yore, but he can (and does) vary the way he draws to suit the venue.

Stunning samples of some of his work, including caricatures of some of the

actors in Marvel superhero movies, appear in this vicinity. Said Emdin: “I’m amazed, overwhelmed and most of all totally honored to be nominated in three [Silver] Reubens categories — especially considering the high quality of work over all the categories.” Dave Kellett is nominated twice, both in online comics—long-form (Drive) and short-form (Sheldon).“It’s a huge honor to be listed among cartoonists I know and respect as working at the top of their game,” Kellett told Cavna. “And to have both of my strips … be nominated at the same time is such fun! Now I need to throw a shiv between them, and make my two strips fight for my love.” Also nominated in two categories is Glen Le Lievre, for Newspaper Illustration and Gag Cartoons. Here is the complete list of “Silver Reuben” nominees:

NEWSPAPER COMIC STRIPS Lio —Mark Tatuli Pajama Diaries— Terri Libenson Pearls Before Swine—Stephan Pastis

POLITICAL CARTOONS Mike Luckovich Michael Ramirez Ann Telnaes

NEWSPAPER PANELS Bizarro— Dan Piraro The Flying McCoys— Glenn and Gary McCoy Reality Check— Dave Whamond

FEATURE ANIMATION “Boy and the World” “Inside Out” “The Peanuts Movie”

TELEVISION ANIMATION “Tumble Leaf” (Amazon) — Drew Hodges “Puffin Rock” (Netflix) — Maurice Joyce “Zack & Quack” (Nick Jr.) — Gili Dolev and Yvette Kaplan

GAG CARTOONS Glen Le Lievre Benjamin Schwartz David Sipress

ADVERTISING/PRODUCT ILLUSTRATION Ray Alma Anton Emdin Luke McGarry

GREETING CARDS Jim Benton Scott Nickel Robin Rawlings

COMIC BOOKS Giant Days (Boom Box) — Max Sarin Prez (DC Comics) — Ben Caldwell Squirrel Girl (Marvel) — Erica Henderson

GRAPHIC NOVELS “Nanjing the Burning City” (Dark Horse) — Ethan Young “New Deal” (Dark Horse) — Jonathan Case “Two Brothers” (Dark Horse) — Gabriel Ba

MAGAZINE FEATURE/ILLUSTRATION Anton Emdin Rich Powell Julia Suits

ONLINE LONG FORM COMICS (Graphic Novel) Drive— Dave Kellett The Creepy Casefiles of Margo Maloo— Drew Weing Octopus Pie— Meredith Gran

ONLINE SHORT-FORM COMICS (Strips and Panels) Bouletcorp—Boulet Kevin & Kell— Bill Holbrook Sheldon— Dave Kellett

BOOK ILLUSTRATION “Smick” — Juana Medina “Sidewalk Flowers” — Sydney Smith “The First Case” — Gitte Spee

■ The winners, as I said before (but in case you’ve forgotten), will be announced May 28 at the NCS Reuben Awards ceremony in Memphis.

THE BEE’S OHMAN WINS PULITZER Celebrations

erupted on Monday, April 18 at the offices of the Sacramento Bee for its

editorial cartoonist, Jack Ohman, who had just been awarded the Pulitzer

Prize for editorial cartoons for 2015, a recognition that includes $10,000

prize money. Ohman, 55, had submitted a portfolio of 20 of his 2015 cartoons

that explored topics that included gun violence, marriage equality, terrorism

and the state of the American political system. The Pulitzer citation noted

“cartoons that convey wry, rueful perspectives through sophisticated style that

combines bold line work with subtle colors and textures.” Near here, we’ve

posted a couple cartoons from his submission. Runners-up for this year’s Pulitzer include Matt Davies at Newsday and Steve Sack at the Minneapolis Star Tribune. Davies had won the award in 2004 when he was working at the Journal News in White Plains; and Sack won in 2013. Ohman watched the announcement on an Internet live stream in “The Hive,” a third-floor conference room in the Bee where he was surrounded by colleagues. As the announcement was made, reported the Bee’s Sam Stanton, Ohman’s co-workers broke into sustained applause and gave him a standing ovation. Minutes later, standing at a lectern amid a champagne celebration, Ohman said he “could not be prouder to work for the Sacramento Bee and the McClatchy Company.” He recalled breaking into cartooning in 1978 and noted the giants of that era who had won Pulitzer Prizes for their work, including legendary cartoonists such as Bill Mauldin and Herbert L. Block, or Herblock, as he signed his cartoons. “To win an award that they had won is truly overwhelming to me,” Ohman said, adding that winning the Pulitzer is “hallucinogenically fun.” Ohman, who has practiced his craft professionally for more than 35 years, says that he especially values the response today from his cartooning colleagues. “I’ve been very close with those folks and love them,” Ohman told Michael Cavna at Comic Riffs, “and to get that kind of support means a lot.” Ohman came to the Bee in 2013 from the Oregonian in Portland. He was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2012 for that newspaper. Since arriving in Sacramento, Ohman has established himself as a prominent voice on politics and social issues through his cartoons, a weekly humor column, a blog and via his alter ego, fictional California politician Joe King. [Ohman occasionally takes to tv to make spoofing political speeches as King, whose name, when you say it fast, comes out “joking.”—RCH] Ohman began drawing in 1978. He was signed to a syndication contract while drawing for his college newspaper at the University of Minnesota. His work is syndicated in about 200 newspapers nationwide. Ohman came to the Bee after the 2012 death of his close friend Rex Babin, the newspaper’s editorial cartoonist since 1999. Upon learning he had won a Pulitzer, Ohman said, “the first thing that came to my mind was Rex.” [At the time of his move to Sacramento, Ohman may have seen handwriting on the wall at the Oregonian, which may have been contemplating eliminating the editorial cartoonist job.—RCH] In addition to the Oregonian, Ohman previously worked at the Detroit Free Press and the Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch. His other honors include the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, the Scripps Howard Foundation Journalism Award and the national Society of Professional Journalists award. “I started winning awards when I stopped thinking about winning awards,” Ohman said.

THE NEW YORKER WINS PULITZER In a recent issue of the magazine, Conde Nast, the owner, took a full page to “congratulate The New Yorker, the first magazine to win a Pulitzer Prize for its writing—two, in fact.” Then saluted the writers: Emily Nussbaum for her television reviews, affectionate without compromise; and Kathryn Schulz for her scientific narrative about the Cascadia fault line, “a masterwork of enrionmental reporting and writing.”

THINKING VISUALLY WINS LYND WARD PRIZE Penn State’s University Libraries and the Pennsylvania Center for the Book are pleased to announce that Unflattening by Nick Sousanis, published by Harvard University Press, has won the 2016 Lynd Ward Prize for Graphic Novel of the Year. “Unflattening,” the jury noted in the press release, “is an innovative, multi-layered graphic novel about comics, art and visual thinking. The book’s ‘integrated landscape’ of image and text takes the reader on an Odyssean journey through multiple dimensions, inviting us to view the world from alternate visual vantage points. These perspectives are inspired by a broad range of ideas from astronomy, mathematics, optics, philosophy, ecology, art, literature, cultural studies and comics. The graphic styles and layouts in this work are engaging and impressive and succeed in making the headiest of ideas accessible. In short, Unflattening takes sequential art to the next level. It takes graphic narrative into the realm of theory, and it puts theory into practice with this artful presentation of how imaginative thinking can enrich our understanding of the world.” Sousanis showed me a few pages that represented his thesis several years ago at the Denver Comic Con. His premise is that we think in pictures as well as in words. At the time, that seemed to me a commonplace observation. It still does. But Sousanis takes the idea and runs with it to new and unexpected lengths. The press release continues: The Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize honors Ward’s influence in the development of the graphic novel and celebrates the gift of an extensive collection of Ward’s wood engravings, original book illustrations and other graphic art donated to Penn State’s University Libraries by his daughters. ... Between 1929 and 1937, Ward published his six groundbreaking wordless novels: Gods’ Man, Madman’s Drum, Wild Pilgrimage, Prelude to a Million Years, Song without Words and Vertigo. A $2,500 prize and a two-volume set of Ward’s six novels published by The Library of America will be presented to Nick Sousanis at a ceremony at Penn State in the fall.

ZUNAR’S CASE REJECTED Malaysia’s High Court turned down satirical cartoonist Zunar’s legal challenge to the Sedition Act, clearing the way for a lower court to set his trial date on nine counts of seditious speech. Zunar, 53, and his legal team were challenging the legality of the 68-year-old colonial-era law, arguing that the Sedition Act contradicted the new nation’s constitutional guarantee of free speech. Zunar, aka Zulkiflee Anwar Ulhaque, could face 43 years in prison if tried and convicted of alleged sedition stemming from tweets he had sent out that criticized last year’s jailing of Malaysian opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim on sodomy charges. Eric Paulsen, one of Zunar’s lawyers, told BenarNews that his client would now try to persuade the Court of Appeal to overturn the High Court’s decision.

TWO GRAPHIC NOVELS MAKE BANNED BOOKS LIST By Maren Williams at Comic Book Legal Defense Fund Every year, National Library Week starts off with a bang: the release of the American Library Association’s Top Ten List of Frequently Challenged Books from the previous year. The list is compiled by ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom from librarians’ confidential reports of requests to restrict or ban certain books in their collections. Two graphic novels landed on the 2015 list: Fun Home by Alison Bechdel and Habibi by Craig Thompson. Fun Home is certainly no stranger to challenges— it was at the center of South Carolina legislators’ 2014 attempt to cut funding for a summer reading program at the College of Charleston— but it actually had not made the Top Ten List in previous years. On the other hand, the presence of Thompson’s book on the list was completely unexpected. CBLDF has not heard about any challenges to the book via news reports, but we are looking into it further. In any case, we are pleased to already be featuring Thompson’s art on our 2016 membership card and t-shirt!

LYNCHED AT THE IRELAND Legendary underground cartoonist Jay Lynch’s personal collection of original art, comics, correspondence, magazines, press files, and other ephemera has been acquired by the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum (BICLM) at Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio. A press release from the Ireland reports that Lynch, an integral figure in the underground comix movement, is the creator and editor of Bijou Funnies (home to his creations Nard n’ Pat) as well as a frequent guest writer for Mad magazine and the Topps Company, for whom he contributed to the iconic Bazooka Joe, Garbage Pail Kids, and Wacky Packages. He is also the creator of children’s books for Françoise Mouly’s TOON Books series.. “I knew my collection would be given the greatest care and respect at the BICLM as the home to the largest collection of comic art in the world,” Lynch said. “My interest in comix goes far beyond just my work in creating them and this collection is representative of my lifelong interest in satire, as it applies to comics as well as other aspects of the popular culture spectrum—from satirical publicity campaigns, letters from key figures in satire and the underground movement, and much more.” The collection totals to nearly 250 cubic feet of manuscript materials, original art, underground comix, merchandise from Lynch’s work at Topps, and letters from R. Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Lenny Bruce, Woody Allen, and other icons of the popular culture dating back to 1956. Additionally, the collection is home to an extensive number of fanzines and college humor magazines, often offering the earliest look at work from Harry Shearer, Art Spiegelman, Gilbert Shelton, and more. Also in the collection are some famous (and infamous) publicity campaigns, including groundbreaking satirical work such as Oingo Boingo’s anti-clown movement, Ed Sachs’s Irreverent Newsletter, Alan Abel and Buck Henry’s Society for Indecency to Naked Animals press releases, and early press kits from Jay Ward Productions. Said BICLM Curator and Associate Professor Jenny E. Robb: “We’re honored that Jay is entrusting his extraordinary collection to us. It would be impossible to overestimate the value of these materials for research into the underground comix movement. The collection not only documents Jay’s career, but also provides rich insights into the last half century of popular culture.” Associate Curator Caitlin McGurk adds: “One of the most exciting facets of the Lynch Collection is the astounding amount of juvenilia, saved from the time of creation, from artists like Art Spiegelman, Skip Williamson, R. Crumb, and Jay himself – making this collection a sort of ground-zero for what would become the underground comix movement.”

GEERDES’ RECORDS WEBSITE Clay Geerdes,

one-time college English teacher and sometime cartoonist, spent the last

quarter of the 20th century around San Francisco Bay as a freelance

street reporter and photo-journalist, covering the hip scene. But it was as

champion of creative self-expression and passionate promoter of cartooning that

he made his mark in the history of comics. Clay was a friend of mine, and some

time after he died in the summer of 1997, I devoted a posting of Harv’s

Hindsight to him (October 2013, an expansion of the piece I’d written

for The Comics Journal shortly after he died). Hereabouts is a caricature

I did of Clay. In the ensuing years, others who knew and valued Clay have constructed memorials and remembrances. Among them is Clay’s nephew, Bill Kossack, who has built a website dedicated to Clay, claygeerdesinfo.com The web site showcases the majority of Clay's photography, newsletters, mini-comix, and biographical information of his life. Here’s Kossak’s list of the site’s departments and their contents—: ■ The Biography area will feature a detailed listing of Clay's life events, personal photos, and audio/video clips. Some of the photos will include childhood pictures, Navy military tour, and assorted pictures of family and friends. ■

The Newsletters category has all of the Comix World / Comix Wave issues listed

and arranged by year and title. Every issue has been reproduced in its entirety

along with the date and issue number. [I, like numerous others, contributed a

name plate logotype for several issues; a few of them are near here.—RCH] ■ The Article section will list any article written by Clay that was published by magazines, newsletters, and newspapers. The main Photography section lists Clay's work with subjects such as the early comic conventions in the 1970s, people in the comic book industry, and many other miscellaneous themes. ■ The Anderson Valley Advertiser section lists all of the articles published by Clay in the newspaper Anderson Valley Advertiser from 1995-1997. The full articles are revealed in text format for everyone to read. The full articles Clay did not submit for publication are now released.

ODDS & ADDENDA The first Saturday in May, May 7, is Free Comic Book Day at most comic book shops nationwide. It’s the 15th year of this carefree give-away day. Comic shops must buy the books they give away for nothing, so some shops restrict freebies: you can have three but not four. Some publishers have turned the event into a promotional enterprise: they publish special editions of a selection of their comic books, a sampler that serves as a tease, hoping you’ll return for the full measure when it’s published. ■ Political sensation: Megyn Kelly has landed that interview with ratings magnet Donald Trump for her Fox broadcast network primetime special “Megyn Kelly Presents” on May 17. Extended bits of the interview will air on Kelly’s Fox News Channel show “The Kelly File” the next night. The broadcast, however, is not likely to feature fireworks. Kelly approached Trump herself, and they had an hour-long discussion in Trump Tower, resolving differences and paving the way for the interview. Kelly described Trump as “gracious with his time.” She asked him to consider doing an interview, and he did. And he agreed to do one. ■ Playboy’s May issue, the third in the suicidal re-branding of the

magazine, is out, and it is as uninteresting as its two predecessors. I thumbed

the issue and almost nothing I saw caught my eye long enough to read it. Lots

of white space, and layouts are nearly identical from page to page. Most

articles are but a page in length. Posted near here are the only things that

attracted my attention. ■ Fantagraphics Books has been nominated for 17 Eisner Awards, the Oscars of the comic-book world, the most nominations of any publisher. The publisher, which began in 1976 with just The Comics Journal, has won so many awards in the Eisner’s 28-year history, said associate publisher Eric Reynolds, that they don’t even know the exact total but guess it is “close to 100. ... I don’t think we’ve ever taken the time to quantify how many we’ve received over the years,” he said. “Now you have me curious!” In comparison, Dark Horse Comics chalked-up 12 nominations. ■ Garfield’s creator, Jim Davis, will be teaching at his alma mater, Ball State, starting the fall 2016 semester as an adjunct professor, reports Kara Berg at the Daily News. Davis won't start off teaching a specific class, said Arne Flaten, director of the School of Art. It will be more of a series of workshops, lectures, hands-on demonstrations, focus groups and master classes — some of which will be open to the public, some only available to drawing or animation students. Davis’s studio is in Marion, Indiana, a short commute from the Ball State campus. ■ A previously unknown First Folio of William Shakespeare’s plays was found a few weeks ago in the library at Mount Stuart House on the Isle of Bute off the Scottish coast. The find brings the worldwide census of First Folios to 234 from an estimated 750 copies published in 1623, seven years after the famed playwright’s death. Ardent readers of Rancid Raves will doubtless remember our essay on the Bard in this month’s installment of Harv’s Hindsight. Incidentally, when I wrote about Shakespeare therein, asserting that playwrighting was akin to comic book writing, I didn’t know that the Grand Comics Database (GCD) lists 511 stories attributed to the Bard. Something he wrote inspired them, I assume. “Perchance to dream,” for example, is the name of a story. Big THANQUES to Ray Bottorff, Jr., who keeps an eye on GCD.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

TICS & TROPES Donald Trump is not a serious candidate for Prez. He’s a symptom. Bill Maher, rapping on Ted Cruz: “Do you know that he named the stick up his ass Hank.”

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue.

The New Black Panther; Then the New Moon Knight FROM MY POINT OF VIEW—necessarily the point of view of a white American male pretending he’s not racist—Marvel’s Black Panther character was from the beginning in 1966 a blatant attempt to exploit racism in this country by producing a comic book hero that would champion Africans and African-Americans, appealing thereby to liberal white readers on college campuses and, possibly, to urban black readers. It was blaxploitation in four colors. The Black Panther first appeared in Fantastic Four No.52, July 1966, written by Stan Lee and drawn by Jack Kirby. He is the first black superhero in mainstream American comics, launched several years before other blaxploitation characters—the Falcon, Luke Cage, Tyroe, and Black Lightning. The name, Black Panther, predates the October 1966 founding of the Black Panther Party. Stan Lee said his inspiration for the name was a pulp adventurer who had a black panther as a helper. The Black Panther is the king of an African nation, Wakanda, the most technologically advanced society on Earth. Black Panther is the ancestral, ceremonial title of the country’s monarch, who, in the current incarnation, is named T’Challa. Following his debut in Fantastic Four, the Black Panther guested in a couple Marvel titles, and then in 1968, he joined the superhero team in The Avengers with No.52, and he stayed with them for several years. He achieved his first starring role in Jungle Action No.5, July 1973, saith St. Wikipedia (the source for all this history). His stint in this title lasted for the next 18 issues, his adventures falling into two story arcs: “Panther’s Rage” (Nos.6-18) and “Panther vs the Klan” (Nos.19-24). “Panther’s Rage” is considered by some to be Marvel’s first graphic novel. Writer Don McGregor wrote the 13-issue adventure as a single self-contained multi-issue story. African-American writer-editor (and one of the founders of Milestone Comics, a line of racially diverse books) Dwayne McDuffie said of Jungle Action’s Black Panther feature: “This overlooked and underrated classic is arguably the most tightly written multi-part superhero epic ever. ... It’s damn-near flawless, every issue, every scene, a functional, necessary part of the whole.” But Jungle Action didn’t sell all that well. The Black Panther was re-launched in his own series, which ran 15 issues (January 1977-May 1979) before it was cancelled. And the Black Panther disappeared for almost a decade until 1988, when a 4-issue mini-series Black Panther (dubbed Volume 2) was published. Then came “Panther’s Quest,” 25 8-page installments published in the bi-weekly title Marvel Comics Presents (Nos.13-37, February-December 1989), followed by another 4-issue mini-series, Panther’s Prey (May 1991- October 1991). Then the Black Panther disappeared for seven years. He returned in the 1998 Black Panther series, Volume 3, which ran 62 issues (November 1998-September 2003). In the last 13 issues, T’Challa was relegated to a supporting role for a multi-racial New York cop named Kasper Cole. Two years later, Black Panther returned, Volume 4, to run 41 issues (April 2005-November 2008). Volume 5 began in February 2009 and ran for 12 issues until March 2010. In 2011, T’Challa accepted an invitation from Matt Murdock (aka Daredevil) to become the new protector of DD’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood in New York. With No.513, Daredevil was temporarily retitled Black Panther: The Man Without Fear, through 11 issues (February 2011-November 2011), followed by Black Panther: The Most Dangerous Man Alive for 7 issues (November 2011-April 2012).

CONSIDERING THIS SPOTTY on-again off-again history, the character probably hasn’t done what Marvel hoped it would do: it hasn’t become a first-tier superhero of the Captain America/Superman/Batman species. The character hasn’t failed exactly; it just hasn’t performed at the upper echelons on the newsstands or in the imaginations of readers. Still, as Michael Cavna said at Comic Riffs, the Black Panther is “arguably the most important and well-known black superhero of all time. ... What excited black comic fans [at his debut], in part, was the fact that Black Panther, who didn’t have superpowers, could take on the Fantastic Four and win.” So the Black Panther always seemed like a good idea. And now the publisher is back with another attempt, a six-issue series written and drawn by African Americans, Ta-Nehisi Coates and Brian Stelfreeze. Stelfreeze is a veteran comic book illustrator whose resume begins sometime in the 1980s; Coates is doing his first comic book work in the current iteration of Black Panther. And he ain’t your ordinary comic book scribe. Coates, a writer for The Atlantic, is a “race man” known for his 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations” and his 2015 National Book Award winning Between the World and Me, a musing, as African-American journalist and comics author Darryl Holliday says in the May issue of In These Times, “on blackness in America that led Toni Morrison to compare him to James Baldwin.” Coates is listed in Time’s 100 Most Influential People issue, May 2, for “his timely, provocative and well-researched writings about race and this nation’s shameful history of inequality. ... He navigates the complexities and burdens of race in America compassed by a father’s love for his son.” Coates rejects any suggestion that he should be doing more serious work than writing a comic book. “In my heart, I’m a comic book writer,” he said, quoted in The Week (April 29). “No, he’s never written one before Marvel invited him to last year, just before his treatise on race in America helped win him a MacArthur ‘genius’ grant. But he has loved comic books since childhood, and he jumped at the chance to give a black superhero new life.” “When I was a kid,” Coates said, “Spider-Man was right under Malcolm X for me in terms of heroes. I would like Black Panther to be some kid’s Spider-Man.” He continued: “This isn’t my chance to talk about Black Lives Matter. This is supposed to be fun to read. The politics are in the background. What’s in front is people punching each other.” Holliday’s article, by the way, is entitled “Black Radicalism in Panels and Ink,” which led me to think something revolutionary was coming on the scene. But after reading the comic book, I think Holliday might be right but not in the way that headline suggests. About Coates, Stelfreeze said: “Ta-Nehisi is still evolving as a comic book writer. It’s really cool to see him not only learn the language of visual storytelling but also create new ways of doing it. I think Marvel brought me on to help him learn the ropes, but I find he’s teaching me quite a big as well.” Coates previewed the advent of this series on Twitter by deploying the phrase “black as hell” in describing the star character. But he also “cautions against didacticism in fiction,” said Holliday, “and has promised that the comic will contain ‘no policy papers on the slave trade nor any overly earnest, sepia-tinged Black History Month style of storytelling.’” Instead, Coates told Holliday, “he seeks to hone in on a simpler question: ‘Can a good man be a king, and would an advanced society tolerate a monarch?’” Holliday seems disappointed that he can find no overt parallels in the book to “the black diaspora” or to today’s Black Lives Matter movement. Indeed, the first issue is something of a downer and, thereby, a disappointment. T’Challa has just returned to Wakanda, which has just suffered a series of setbacks—a flood of Biblical proportions that killed thousands (a machination of Namor, the Submariner?), a coup orchestrated by Doctor Doom, and an invasion by the villain Thanos that resulted in the death of T’Challa’s sister Shuri, who had been sitting in for her brother on the throne. Grieving over his sister’s death, T’Challa finds his people strangely restless, raging against him in their agony at their recent humiliations. In the opening sequence, T’Challa is thrown into a rage- and hate-filled mob of his people, who leer at him with jade-green eyes, calling him the orphan king. He extracts himself from their hands, his physical prowess enhanced by the tech-assisted Black Panther costume. He vows to find out what has infested his people and to restore their allegiance. This is one of the two complete episodes in the book: it shows T’Challa to be powerful but thoughtful and dedicated to his country. In the other complete episode, two women, lovers, Aneka and Ayo, both erstwhile members of Dora Milaje, the elite female royal guard, are reunited: Ayo rescues Aneka, who has been imprisoned and sentenced to death because she murdered a chief who abused the girls of his village. While sympathetic to T’Challa and his dilemma, they vow to save their country—whatever T’Challa might think or do. Says Aneka: “No one man should have that much power.” This episode reveals the womens’ passion for each other and their determination to alter (for the better, they think) their situation and that of their country and its people. Hovering in the background are two other women—T’Challa’s mother, the power behind the throne who refuses to pardon Aneka; and the mysterious Zenzi, who seems poised to lead a revolt. Her name, Holliday tells us, “is a nickname of South Africa’s Zenzile Miriam Makeba, aka Mama Africa, a freedom fighter in her own right who was also married to none other than Stokely Carmichael, the former honorary prime minister of the Black Panther Party.” In the book’s closing moments, we see T’Challa brooding, sadly wondering “how long” he must be separated, divided, from his blood, his people. And from the ghost of his departed sister. The ending is scarcely a robust cliff-hanger. We may be sympathetic to T’Challa in his grief and sad longing. But is that enough to bring us back to the second issue? For me, it is, but mostly because I fancy myself a chronicler of the medium and therefore feel duty-bound to see how this turns out. But the ending is more downer than it is a resounding call for re-convening at the next issue. I feel as if we’re standing at the edge of a newly dug gravesite rather than a newly launched life for Black Panther. If nothing else (and there is a felt duty, as I said), Stelfreeze’s art will bring me back. Most of the pages, even the brightly lit ones, are dipped in black. But the black is not shadowing. His stylized treatment of black-skinned people is stunning: instead of highlights, we have darklights.

In Stelfreeze’s commanding treatment of the Black Panther costume, muscles and forms are etched by black modeling in solid shapes, not feathering. And as a final fillipe, the high-tech micro-chip mechanism of the suit is indicated by spidery wire-lines whenever T’Challa activates it; ditto, the uniforms of Aneka and Ayo. Says Stelfreeze: “I’ve always liked the simplicity of the Black Panther costume. I’ve never liked when people give him flashy capes and other adornments. Perhaps if he was called the Black Lion, those accouterments would make sense, but ‘Black Panther’ suggests a sleek efficiency so I’m staying simple. I’m adding small touches to make him feel more aggressive and catlike, but just keeping it simple.” Going beyond costuming, he continues: “Ta-Nehisi’s script feels very African, so I wanted the art to reflect this. I’m pulling from cultures all over the continent to establish the look: Masi tribesmen, Ancient Zulu warriors, and even modern Kalashnikov-wielding rebels will all influence the look of Wakanda.” Unfortunately, Laura Martin’s coloring suffers from the usual flaws often seen in computer-coloring: the colors are too dark and often obscure the drawing. This fault is caused by the light being behind the color on the computer screen: back-lit colors seem brighter than they are, and so the colorist darkens them slightly to make the screen image look like what the colorist imagines. Alas, when printed, the colors are too dark, and they overwhelm the rest of the art. Too bad. But Stelfreeze is still worth looking at.

AS AN AFRICAN-AMERICAN WRITER, Holliday likes Black Panther because his, Holliday’s, race isn’t side-lined as it usually is in superhero comics. But he also cheers the integral presence of “strong, dark-skinned” women and applauds the inclusion of “voices historically left out of the conversation.” Holliday notes that pre-orders for Black Panther No.1 totalled 300,000, which he sees as an indication of the current status of comics and graphic novels “as serious literary art.” In conclusion, he says: “The comic book also has the potential to mark a watershed in another kind of inclusion: that of artists, writers and readers of color in the comics canon.” He sees in the configuration of the plot vague references to contemporary America—specifically, echoes of the Black Lives Matter movement, at least, in the uprising of the people against the authority of government. But if T’Challa manages to quell the rage and hate of his people, thereby reinstating the monarchy, what of Black Lives Mattering? The answer will be found in T’Challa’s manner, how he performs and by what values he leads. I, on the other hand, see in this issue the shadows of polarized America: the confrontation being set up between T’Challa and the women and the enraged populace seems to me to evoke the kind of polarization we experience when opposing political parties hold uncompromising positions. This book may not be about Black Lives Mattering: it may be about the decay of culture akin to that of our own, when huge segments of society reject gay rights as well as black lives. I’m looking forward to seeing what remedy Coates proposes.

“SUPERHEROES HAVE STOOD ASTRIDE the American pop-culture landscape for eight decades,” said Michael Cavna at Comic Riffs, “but racial diversity has largely been left in the margins. So while we have had black superheroes for much of that time now, in the movie adaptations their roles have often been secondary. That’s why 2016 feels like a watershed year. May’s ‘Captain America: Civil War’ is the first mainstream movie to co-star three black superheroes: War Machine (played by Don Cheadle), the Falcon (Anthony Mackie) and the Black Panther (Chadwick Boseman). That same month, ‘X-Men: Apocalypse’ will spotlight Storm (Alexandra Shipp); and in August, DC Comics’ ‘Suicide Squad’ will be led by Viola Davis and Will Smith. “The quintessentially American art form that is superhero comics is embracing fictive worlds that look like America itself. And in 2016, black capes matter,” Cavna concludes. *****

MOON KNIGHT is another on-again off-again second- or third-tier Marvel character. And he, like Black Panther, is back again for another try, written by Jeff Lemire and drawn by Greg Smallwood. The character showed up first in Werewolf By Night No.32 in April 1975. He popped up on other titles for a couple issues each until 1980, when he got his own title, running for 38 issues until July 1984, followed by a 6-issue series, Moon Knight: Fist of Khonshu. In 1989, Marc Spector: Moon Knight showcased the character for the longest time, 60 issues, ending in March 1994. There were two 4-issue series in January 1998 and January 1999, then nothing until April 2006, when Moon Knight was revived for 30 issues, ending July 2009. A 10-issue series ran the rest of 2009 and into 2010, followed by a 12-issue series in 2011-12. In March 2014, a 17-issue series started. Then this spring, another Moon Knight debuted. In his civilian guise, Marc Spector was at first a mercenary, who stumbles upon an archaeological dig where the Egyptian moon god Khonshu is unearthed. Trying unsuccessfully to avenge the murder of one of the archaeologists, Spector is left to die in the desert but is found by roaming Egyptians who carry him to their temple, where Khonshu appears to him in a vision, offering him a second chance at life if he becomes the god’s avatar on Earth. Spector returns to the U.S. and decides to fight crime and assumes a couple of alternative identities: to separate himself from his mercenary past, he takes the name Steven Grant, who is a millionaire (Spector having invested his savings accumulated while a mercenary); to keep in touch with the street and crime, he becomes a taxi-cab driver named Jake Lockley. And that’s the beginning of the troubles. From the alternative identities, Spector understandably develops a multiple personality disorder and other symptoms of mental instability. And he’s been killed a few times. All of which comes to a head in Lemire’s debut issue: Lemire “embraces that aspect of the character,” said Sean Edgar in Playboy’s May issue. The entire first issue is devoted to depicting Spector’s struggles in a mental hospital, where he’s brutalized by a couple of attendants, Bob and Billy, as he attempts to convince them that he isn’t mad. Two or three incidents of this sort constitute the complete episodes in this issue—and they convince us, almost, that Spector isn’t quite sane. Bob and Billy are sadistic, but we can’t tell whether that’s a fact or Spector’s delusion. Said Lemire: “He’s the only superhero who overtly addresses schizophrenia and multiple personalities. When most superheroes were created, mental illness was seen as a weakness, a flaw, whereas now, people are much more aware that the brain, just like any part of your body, is something that can be sick and treated.” In his mind, Spector appeals to Khonshu, but by the end of this first issue, he is no longer convinced that the Moon Knight is real or that the adventures he remembers actually happened. Since we know there is a Moon Knight who has had crime-fighting adventures, we’re on the affirmative side of the dispute in Spector’s mind. And we probably have hopes that he’ll re-establish his sanity in future issues. According to St. Wikipedia, Lemire intends this series to “focus on the psychological issues, the mental scarring and multiple identity crises suffered by superheroes [who necessarily have alter egos], what being a superhero entails, and the difficulty of maintaining a normal life as a member of society.” I suppose this means there’ll be no fisticuffs in the this evolution of Moon Knight. But we will be treated to the inventive artwork of Smallwood, who, in this debut issue, draws in two different styles and varies page layout dramatically. Wide page margins, for example, give the visuals an suitably antiseptic clinical feel. I’ll be back—for the pictures alone if necessary; but Lemire’s agenda is provocative, too, and I’m interested to see where he goes with a deranged (maybe) superhero, suffering from all the mental problems you’d expect him to have.

WHY THE RESURRECTION of all these second- and third-tier characters? Easy: movies. Riding the surge of Hollywood’s and the public’s apparent fascination with movies about comic book superheroes, Marvel and DC need more superheroes than their rosters of first tier characters provide. How many more Batman movies can be manufactured out of Bruce Wayne’s poignant history as the haunted surviving witness of his parents’ death by murder, which scarred him psychologically as the only witness. You can do only a few Avengers movies before invention flags and public interest fades. So, you need more characters. Rather than invent some new ones—who would have no built-in fan base—it’s cannier for eventual marketing to excavate the past for heroes no longer exactly on everyone’s mind, but, at least however vaguely remembered, more familiar than new strangers. Admittedly, neither Black Panther nor Moon Knight are relics of the distant past (like, say, the Shield?), so they have some sort of fan base out there—enough that they can be recruited to join other, more visible characters, in a new movie. Or, even, soloing like Doctor Strange. But bringing them back first via comic books is a cunning gesture at creating a fresh crop of fans in preparation for the debut of a movie appearance. Superheroes are on the cover of Entertainment Weekly’s “Summer Movie Preview” issue April 22/29, demonstrating, once again, the rise of skintights from four-color pulp to celluloid status: thus, movies have validated the cultural worth of superheroes. If you’re in the movies, you have arrived, culturally speaking. In the last 25 years, 138 movies have been made of comic book heroes, more—at the rate of several a year—in recent years. Most of the earliest ones simply perpetuated the existing comic book adventurer mythos. But lately, movies of comic book superheroes are corrupting their four-color source. Cultural success—moving out of the subculture of funnybooks onto the big screen—is changing funnybooks and not necessarily for the better. In the olden days, movie superheroes had to look like their comic book selves. That’s changed. Comic book characters now must look like their movie versions, so their appearance—even their physiognomy— changes as different actors perform the roles. And the changes don’t end there. In the movies, Lois Lane now knows Clark Kent is Superman. That’s a profound alteration of the Superman myth; and now the comic book version must conform. Costumes change, too. And this is where the greatest corruption occurs. Back at the dawn of time, the movie version of a superhero wore tights just like the funnybook version. But that was the weakest link in the connecting chain: the success of the celluloid incarnation depended entirely on the physique of the actor playing the part: if he didn’t have a muscular body, his interpretation was lame. (And if he had the requisite body, his performance was likelyk to be lame.) Hollywood’s solution to this dilemma was to re-design the costume to mask the physical shortcomings of the actors.

Figure-drawing is no longer good enough in a medium that was built entirely on figure-drawing. Sigh.

**** On to Other Recent Comics ****

THE FIRST ISSUE of American Monster begins with the kidnaping of Marjorie and Gerald, man and wife, and it ends with their perverse murder. They’re tied to chairs facing each other, each training a pistol on the other, and their arms are taped together so they can’t change the aim. Their kidnaper tells them he’s going to do a count down, “an’ if one of you ain’t dead at blast-off, Imma shoot you both.” At the count of nine, Gerald pulls the trigger and kills his wife. Then the kidnaper shoots and kills him. The kidnaper prefaces his action by complaining that Gerald and Marjorie have conned him out of a large sum of money, so his murdering them is seemingly an act of justice. This bizarrely heartless scenario is the invention of writer Brian Azzarello, who has concocted the whole notion of the book. And it is one of two completed episodes. In the other, a huge scarred and burned-red man, a traveler, comes into a bar, looking for a mechanic to fix his car. It’s late in the evening so no mechanic is around. On his way to a motel, Big Red stops at a diner to eat, and the man at the other end of the counter wants to buy his dinner as gesture of thanks to a veteran, which, judging from his scarred appearance, Big Red probably is. But he belligerently refuses the generous offer, saying he’ll buy his own and putting a wad of bills on the counter on top of a newspaper headlined “Bank Heist.” In the distance, his car blows up. The kidnaper/murder episode shows us a heartless thug at work; the Big Red episode shows us a rude thug who at least begins by asking the right questions about a mechanic’s availability and, subsequently, where he can eat and sleep overnight. Despite his ugliness, he seems otherwise ordinary. In a third episode, we see several young people gathered around a seesaw, and the girl, Snow, on one end of the seesaw bares her tits on command several times, apparently accepting payment each time from the man on the other end of the seesaw. The group is having a completely irrelevant conversation about whether the girl is a vegetarian. Three pages midway through the book depict an incident in a war, ending with a close-up of one of the soldiers, perhaps Big Red, looking in horror at something we don’t see. Yet. The second issue doesn’t unravel much of this tangle. The central incident, which is not exactly resolved, is the discovery of a dead dog by the sheriff and his deputy. The deputy goes to report the death to the dog’s owner, who turns out to be the kidnaper of the first issue. The deputy also visits Big Red to find out why his car exploded. We see that both the kidnaper and Big Red have the same brand on their backs, double S’s like the insignia for the Nazi Schutzstaffel (“protective squadron”). In another incident, Big Red lies on the road, paying dead, and when someone comes along, he rolls over and aims a gun at the interloper and apparently shoots him. At the end of the issue, the deputy goes home to attend to his invalid mother, who suffers, perhaps, from Alzheimers and has soiled herself. In other words, after two issues, we still don’t know what’s going on. But Azzarello is skilled at keeping us interested regardless. And he is ably assisted in this title by an artist who is listed as Juan Doe; since that’s Spanish for John Doe, I assume it’s not the artist’s real name. But he is expert at dousing his pictures in black and dim shadows, and the dim lighting within the panels is augmented by solid black throughout where typically white margins separate the panels. He also occasionally uses white silhouettes to good effect as visual accents.

I’ll come back for a third visit just to see more Juan Doe.

THE NEW BLACK WIDOW is a visual and visceral treat. The first issue is all action, constant movement—and mostly, without dialogue or captions. Just the Black Widow in motion. On the first page, we see her walking through an office as a public address system announces: “Effectively immediately, Agent Natasha Romanoff, code-name Black Widow, is to be considered an enemy of S.H.I.E.L.D. She is to be stopped at any cost.” She breaks into a run, and thereafter, we see Black Widow in continual combat with her would-be captors, all agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., as she fights her way to freedom, leaping free of the agency’s giant hovercraft and falling to Earth through a series of lucky landings. And why is she an enemy? Because, we learn later, she stole some top secret data. What and for what reason, we don’t know yet. But with visual excitement like this in store, we’ll come back next issue to find out. Artist Chris Samnee is credited with Mark Waid as half the writing

team—and with good reason: the “writing” in this issue is mostly Samnee

depicting the escape of Natasha. His bold linear style is on full display,

clearly showing every step of her progress. And he had to invent and

choreograph every step. His imagining and visualizing of physical action is a

marvel to watch. Near here, we’ve posted the second and third pages of this

issue. There is no compete episode nestled in this book: it’s all a complete

episode, from beginning on the first page to ending, victorious, on the last

page. This is great superhero comics, kimo sabe. Those skin-tight costumes are meant to make movement easy, and here we have non-stop movement. In No.1's letter page, Waid explains how he and Samnee work together: they co-plot the the book “with Chris handling the way the story is told and me adding final dialogue.” In No.2, there’s a little more verbiage—speeches by characters, no captions. But the action continues pretty steadily. And the mystery persists.

BARBARA MORSE, aka Mockingbird, is entirely too beautiful. And all the other women in the first issue of this eponymous 5-issue run are likewise. They all look entirely too much alike—except for color and styling of hair. That’s artist Kate Niemczyk’s fault, and it’s not a bad one: we all like to look at beautiful women (like those in the preceding visual aid). Her drawing style is clean and uncluttered; bold lines where necessary, contrasting nicely with finer lines. Background details ruled rather than free-handed. But it’s all so cleanly done that this shortcoming is scarcely noticeable. Through this entire issue, Mockingbird returns repeatedly to the S.H.I.E.L.D. medical facility to be checked for symptoms of unanticipated side-effects due to ingesting a couple of experimental drugs. Writer Chelsea Cain gives the character plenty of sarcastic witty remarks. “You guys have totally ruined the thrill of peeing in a cup for me,” she says. And then: “I’ll get all the urine back at some point?” Not much else happens. On occasion, she manifests symptoms that the check-ups are supposed to discover, but she doesn’t admit to them. Only one action sequence: she breaks down a door. In what might be regarded as the completed episode, she manages to move a ping-pong ball with her mind. Still, Mockingbird shows promise. Apart from Niemczyk’s beautiful pictures, there’s this prediction from Cain: “Each of the next three issues will fill in what happened between appointments and then the fifth issue will pick up where this one leaves off. ... My goal is that you will read this issue, read the next four, and then come back and read this one again, and it will be a completely different experience. It’s like two for one.” Sounds good to me. I’ll be back.

EVERYONE WANTS

TO BE DEADPOOL, apparently: here comes writer Christopher Hastings with Gwenpool. This

POWER MAN AND IRON FIST are back; there’s probably a movie being made somewhere that needs the publicity. (Right: a Netflix flick; see below.) Danny Rand (aka Iron Fist) wants to revive their team-up but Luke Cage (Power Man) doesn’t. That’s the on-going joke, and it lasts for both of the two issues out so far. The adventure gets underway when Jennie Royce, former office manage for Heroes for Hire, gets out of prison and wants them to retrieve her grandmother’s necklace that was taken from her by Lonnie Lincoln (aka Tombstone, boss of organized crime north of 110th Street), who (she says) mistook the necklace for some of the late Eugene Mason’s stash which Lonnie took because Eugene owed him money. But Jennie is lying. The necklace is a mysterious and powerful trinket (containing the supersoul stone) that Jennie gives to Mariah Dillard (aka Black Mariah), who plans to use the necklace to take over Lonnie’s operation. By the second issue, Lonnie is sending his goons after Iron Fist and Power Man to recover the necklace. And fisticuffs ensue. (Again. They were required in the first issue to extract the necklace from Lonnie.) Because the title characters are old timers in the Marvel stable, we scarcely need a first issue that acquaints us with them—even though under the new rubrick, neither Power Man nor Iron Fist are quite the same serious personages they once were. The running joke about teaming up or not defines their personalities: Luke resists Danny’s insistance, and Danny tries to be irresistible, joking and grinning all the way. David Walker is telling the tale here, but it’s Sanford Greene’s drawing that gives the title panache. His linework is scratchy, which lends the visuals a happy loose feel. And in rendering Luke Cage, he produces a massive figure, a colossus of a man, massive muscles on the cusp of overweightedness. That’s a satisfying visual appeal, and the scratchiness enhances it all. The title is a step away from Deadpool/Gwenpool nonsense, but I can’t help feeling that the jokey dialogue between Luke and Danny is an attempt to mimic the fun time atmosphere of those titles.

ABOUT THE IRON FIST MOVIE: It’s a Netflix series with “Game of Thrones” actor Finn Jones in the title role. Entertainment Weekly reports that he is training for the role, his daily routine “consists of hours of martial-arts practice (kung fu and wushu mixed with a bit of tai chi) followed by lifting weights (“to bulk me up”) and meditation and Buddhist philosophy studies. Says Jones: “I’ve always dreamed of a role that bridged spiritual discipline and badass superhero. There’s a contradiction I those elements that’s going to be very fun to play.”

THE FIRST ISSUE of Aftershock’s Rough Riders sets up the series’ premise right away. On the eve of the Spanish American War, New York police commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, dressed as some sort of trouble-shooter, saves some women from fiery death as a dirigible explodes. TR is an action hero! Later, TR is recruited by four wealthy men (Morgan, Carnegie, Vanderbilt, and Rockefeller) to make a secret expedition to Cuba in advance of America’s invasion of that country. TR says he needs to recruit a team to help him—“a phenomenal” team “with special skills.” From

the cover of this issue, we know that the team will consist of TR,

prize-fighter Jack Johnson, inventor It’s a promising concept from writer Adam Glass—why has nobody thought of Teddy Roosevelt as the hero of a comic book before?— and artist Patrick Olliffe is more than competent, a first-class storyteller. I wish his linework was a little less tightly controlled—his characters look a little stiff even when in motion—but that’s a matter of personal taste, not an objective critical judgment.

MEANINGLESS SPECULATION Okay, so when you come indoors from outdoors where you've been wearing your shades, you take the shades off and tuck one temple (one of those armatures that hooks over your ear) of the spectacles into the neck of your t-shirt. That keeps them safe because they're close enough to your body that they won't be harmed unless your body is. So who invented this maneuver? What genius? My guess is that the first guy doing this was a flamboyant athletic type who wore tight t-shirts and pants. No pockets to put his specs in— or to store a glasses case if he had one. But he could squeeze the armature of the glasses down the front of the neck of his t-shirt. What's your version?

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy IN THE NEW

YORKER dated April 25, which hit the newsstands in New York a day or so

before the primary, all 17 cartoons were Trump cartoons. In all of them, Trump

or something he said is being ridiculed. And yet the Trumpet won hugely in the

Republicon primary. Go figure. (What?—you think people who vote for Trump read The

New Yorker?) Roz Chast, whose drawing, depicting a faux newspaper front page, I needn’t post here for the humor: the headlines read—It’s Still April Fool (the biggest type), Trump Comes Clean—“Just a Joke, Folks!”, All a Big Put-on, Apologizes for Confusion, Amazed Anyone Believed He was Serious, Trenton Man Says “I Knew It All Along.” And Shannon Wheeler’s cartoon shows two people at the rear of a huge audience with Trump at the podium in the distant front; one of the people says to the other, “With great ignorance comes great confidence.” (Which shows just how far into popular culture the Spider-Man mythos has penetrated.) None

of these cartoons are editorial cartoons, but they pack as much punch in their

own way as any of the editorial cartoons we have in our first visual aid. Next around the clock is David Horsey, who has assembled the Trump Constituency—Guys with Attitude, Guys with Comb-overs, Guys with Trophy Wives, Schoolyard Bullies, and Reality TV Fans. The combined imagery is incriminating enough even though as a visual metaphor, it hasn’t the punch, say, of Jeff Darcy’s cartoon immediately below in which Trump’s famous hair has been reconfigured as a jester’s cap and balls, strenuously implying that the candidate is a joke. To the left, Henry Payne, a staunch conservative, is apparently no friend of Trump’s: he reminds us that Trump, who has railed against manufacturers who take their industries out of the country—depriving American workers of jobs—gets some Trump products from overseas factories, betraying just a little of the hypocrisy for which he is famous. Below Payne, Keith Knight’s (th)ink provides the Trump campaign with a model bumper sticker—the burning cross and pointy hat denominating the Trump supporter at the wheel of this vehicle as a member of the Ku Klux Klan. At the immediate right, Nate Beeler’s excellent caricature of Trump shows us just how small the candidate’s hands are while also framing his position on abortion with a wire coat-hanger, the symbol of the olde-tyme alley abortionist who plied his trade with dangerously unmedical methods. And across the bottom, here’s one of Scott Stantis’ Prickly City comic strips in which the GOPachyderm reminds heroine Carmen of the 2000 presidential election in which Al Gore lost to GeeDubya by one vote on the Supreme Court, proving just how little the voter populace means to the GOP.

WE CONTINUE

bashing the Trumpet in our next exhibit. Below Ramsey is Chan Lowe’s characterization of the Trumpet as a Nazi: instead of putting his hand on the Bible, Trump raises it in the memorable “heil Hitler” salute. Ouch. Finally, Matt Wuerker has some fun showing us how Trump prepares his hair every day. I’ve wondered why none of the so-called “news” media haven’t given us photographs of the Trump attendant who must accompany him everywhere to do touch-ups on the knit-wig. For

our next display, we change the subject to something that actually amounts to a

genuine public concern—North Carolina’s resistance to transgender progress. Below Toles is a cartoon by Glenn McCoy, whose rabid right-wingery is so extreme I usually have trouble just deciphering his meaning. And this cartoon is no exception. He’s pretty clearly bashing liberal attitudes. On the left, he depicts the whiney liberal politically correct college student “victim,” complaining about his “safe space” being invaded. On the right, he shows us an innocent little girl whose complaint about transpeople invading her “safe space” is labeled bigotry by those whiney liberals. The comparison accomplished by assuming a “liberal” perspective in the second panel reveals the essential hypocrisy of the left. Or so I guess McCoy means. He inadvertently shows what the anti-transgenderite really fears. Using the image of a little girl, McCoy activates the fear that motivates the protestation: we don’t want men disguising themselves as women in order to enter women’s restrooms with sexual assault on their agendas. This law will protect our innocent daughters! At the lower left, Nick Anderson offers a grisly albeit unforgettable metaphor for the restrooms that the North Carolina law would reserve for transgender people. North Carolina’s restroom law raises a fascinating question: How will they enforce it? If a transman (born male, identifying female) enters a woman’s restroom, how will anyone know she’s a he on her birth certificate? Dressed in feminine apparel, she’d enter the restroom and go to a stall to do her duties. No one would know which kind of apparatus she’s using for alimentation. Ditto for transwomen: clearly, they wouldn’t stand at a urinal; they’d go to a stall. Nope: this law won’t work. The only way to make it work is to have a cock-and-balls/pussy check at the door: before being allowed to enter the restroom, a person must display his/her genitals to a gate-keeper. Not a very practical solution. And it violates the very sense of privacy that the supporters of the law say the law seeks to preserve. Impractical

or not, at the upper left of our next visual aid (wherein we continue the

hilarious comedy of the restroom law), Steve Sack pictures just the

solution I’ve described—a “hoohoo” inspector at the door of every woman’s

restroom. (Dunno where “hoohoo” comes from or its etymological origin, but it

seems perfect for the occasion.) Notice, as a final hysterical fillip, the

little mirror on rollers that can be shoved under a person to look up his/her

dress to see that he/she is properly equipped to enter a woman’s rest room. Lalo Alcaraz, aiming in about the same direction, resorts to those abstracted symbols that designate men’s and women’s rooms, adds another abstracted symbol to represent the hoohoo inspectors, and then indicates what will be inspected. Ingenious. Snaking back and forth across the page, we go down to Mike Luckovich, who has a simpler, less egregious solution—just use those body scanners we walk through in airports. “Welcome to North Carolina” indeed. Changing the subject to less inflamatory matters as we move to the left, here’s R.J. Matson with a re-designed Form 1040 for declaring your income for tax purposes. He’s mocking McConnell and the rest of the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderms on the issue of confirming Antonin Scalia’s replacement on the Supreme Court. Snake down next to Chan Lowe’s anticipation of the Republicon Convention to which loyal members of the National Rambo Association delight in the prospect of “open carry,” a new policy at the Convention based upon the NRA’s conviction that the more people who are openly armed, the less the likelihood of any actual shooting taking place. The ruling Pachyderm, however, seems less than convinced: he’s wearing armor. Probably a good idea, considering the prodding that the Trumpet does to provoke violence at his rallies. And then here’s Bob Englehart, who playfully (albeit accurately) combines two issues—the Trumpet’s complaints about rigged primaries and African-American assertions about a rigged system. Not a memorable image, perhaps, but a statement of undeniable truth withal.

IN OUR NEXT

EXHIBIT, we continue to attend to other matters—no less rollicking—beginning

with Jen Sorensen’s playful dissertation on the unequal treatment women