|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Opus 347 (December 31, New Years 2015-16). Christmas, you may have noticed, has slipped over the horizon. It came earlier this year than I planned, and before I knew it, it was gone. No matter. Here at Rancid Raves, we celebrate all year long— merrily with oboe and bagpipes.

We begin this post-holiday holiday outing with a hare-raising discussion of Ted Cruz’s self-serving spew about an editoon that correctly castigated him for exploiting his young daughters and then we celebrate the Christmas season with Charlie Brown and vintage Xmas strips, after which come profusely illustrated reviews of nine first issues of recent funnybooks— Miller’s Dark Knight III: The Master Race, Fourth Issue of the New Archie, New Daredevil, Superman: Lois and Clark, Captain America White, Huck, Goddamned, New Shield, New Hawkeye, New Wolverine— plus Womanthology Heroic, Will Eisner: Champion of the Graphic Novel and some graphic novels (Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage; Ann Tenna: A Novel; and The True Death of Billy the Kid) and The Life and Art of Wesley Morse of Tijuana Bible fame, all of which should help you decide how to spend the money Aunt Hazel gave you for Christmas. And we also have our usual survey of recent editorial cartoons and some antics in comic strips lately. Here’s what’s here, by department, in order (a listing that begins right after we post a couple correksions)—:

CORRECTTING ERRORS We always admit our most recent mistakes in the most conspicuous place just before committing new ones. Under the heading Collectors’ Corniche last time, Opus 346, I posted a copy of the Funnyville endpaper with scores of comic strip characters in it, alleging that it appeared in a history of King Features, King of the Comics, which I reviewed in Opus 345. Not true: Funnyville was the endpaper in Cartoons for Victory, a survey of wartime cartoons from World War II, which was reviewed in that very posting. And in reviewing Stan Lee’s graphic autobiography, the third illustration included a full-page portrait of Lee, which I indicated had been drawn by the superlative Colleen Doran. Not so: that portrait is apparently from Foom No.17, drawn by someone else entirely. Sorry about that. Er, those.

NOUS R US Ted Cruz Spews about Editoon Scoring Playboy Lang Syne with Christmas Strips Comic Book Movies Frank Sinatra Birthday Edge City Ends

Odds & Addenda Facts about Gitmo, Wealth, Gun Violence

FUNNYBOOK FANFARE Reviews of—: Miller’s Dark Knight III: The Master Race Fourth Issue of the New Archie New Daredevil Superman: Lois and Clark Captain America White Huck Goddamned New Shield New Hawkeye New Wolverine Doc Savage Savage Dragon No.209

EDITOONERY Surveying the last month’s editorial cartoons —with a special emphasis on The Trumpet

The Froth Estate

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAG VIGIL Antics on the Funnies Pages

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews of—: Charlie Brown’s Christmas Stocking The Joy of a Peanuts Christmas: 50 Years A Charlie Brown Christmas: The Making of a Tradition Twelve Terrors of Christmas (Edward Gorey) The Life and Art of Wesley Morse Womanthology Heroic

BOOK REVIEW Long Review of—: Will Eisner: Champion of the Graphic Novel The Lost Comics of Will Eisner (announcement)

GRAPHIC NOVELS Reviews of—: Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage Ann Tenna: A Novel The True Death of Billy the Kid

Onward, the Spreading Punditry Don’t Call ’Em ISIS

PASSIN’ THROUGH Blaze Starr The Hug Lady

ANOTHER ANYULE GREETING With George Booth

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

CRUZ MAKES A MONKEY OF HIMSELF A week or so before Christmas, Republicon prez candidate Ted Cruz released a self-glorifying tv campaign ad in which the Texas senator and his wife sit on the family couch while attentive, loving father Ted reads Christmas stories to his two daughters, ages 5 and 7, from books with such parody titles as How Obamacare Stole Christmas and Rudolph the Underemployed Reindeer and The Grinch Who Lost Her E-mails. At various intervals during the ad, viewers are invited to send in donations to obtain their very own copies of the books. At the end of the bedtime reading, the older of the two daughters speaks up, gesturing and pointing and turning her head dramatically from left to right and back again and again, calling Hillary a grinch and attacking her about her e-mail server. The words she speaks are clearly not her own: she’s reciting lines written for her (perhaps by her doting father?). Hers is a Shirley Temple imitation, but, as one viewer reported, the girl looks more like she’s auditioning to be the next Money Boo Boo. A

few days later—on December 22—the Washington Post’s Ann Telnaes, a Pulitzer-winning cartoonist, posted the cartoon displayed hereabouts,

depicting candidate Cruz as that old time entertainer, the sidewalk organ

grinder, whose monkeys are trained to dance in tune with the music the organ

grinder grinds out—a virtuoso image of precisely what Cruz does in the tv ad. Cruz, of course, did not see it that way. To him, Telnaes was ridiculing his daughters, not their father. He began at once frothing at the mouth with protective paternal rage —while at the same time rubbing his hands with mercenary glee. He was outraged, he said as loudly as he could, that his kids would be used as political fodder by an editorial cartoonist. Telnaes acknowledged that the children of politicians are typically off-limits, but in this case, since the politician had used his kids as political commentators, satirists even, not just as members of his family, depiction of the girls was fair. Cruz didn’t bother to disagree: he was busy sputtering outrage and then, in an ingenious effort to turn lemons into lemonade, asking his supporters to donate a million dollars within 24 hours so he could send the Post a message. He sent them all an e-mail with Telnaes’ cartoon in it, calling it evidence of the liberal bias of the news media. Tea Baggers lapped it up. Suddenly, Telnaes’ editor, Fred Hiatt, yanked the cartoon, offering this lame explanation: “It is generally the policy of our editorial section to leave children out of it. I failed to look at this cartoon before it was published. I understand why Ann thought an exception to the policy was warranted in this case, but I do not agree.” The news of Hiatt’s action spread quickly through the small but vociferous editooning community, inspiring a host of reactions—all supporting Telnaes. I do, too, in case it’s not obvious by now from the tone of my voice. I count myself a friend of hers, and I think this cartoon, like most of hers, is brilliant. The visual metaphor is apt for depicting what Cruz is doing and thereby is perfect for criticizing Cruz’s sleazy campaign tactics, exploiting his children for political advancement—not only with the original parody ad but in the subsequent solicitation for funds to attack the Post.

EDITOONISTS AROUND THE COUNTRY quickly came to Telnaes’ defense. (She, meanwhile, cannily aware that whatever she might say in the immediate aftermath would supply Cruz with more fodder, maintained a strategic silence.) Right Wing-Nut vitriol reached poisonous levels, with assorted (a sordid) cries for Telnaes to be raped or murdered. Or both. (What have we become in the extremities of our political posturings?) At the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC, of which I am not only a member but a former officer), reaction was swift. AAEC issued the following statement (in italics)—: The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) stands in support with Ann Telnaes and her right to call out presidential candidate Senator Ted Cruz for politicizing his daughters in a campaign attack ad. While it would be in bad taste to arbitrarily go after a public figure's family, it is fair journalism to criticize the senator for using his own children to attack a political opponent. And that's precisely what Ann's cartoon has done. It does not stray from the time-honored tradition of cartoonists using satire to speak truth to power and protect the powerless – in this case, children. Cruz ventured into new territory when he had his 7-year-old play an active attack role reading from a script in a campaign ad criticizing political opponents. The media should draw a distinction between this and when elected officials merely use their family in photo ops and positive campaign promotion as has historically been the custom. Cartoons speak in metaphor, and the monkey image is integral to the age-old organ grinder symbol. Taken in full context, Cruz was clearly the target, but he and his supporters deflected the message by claiming his children were the victims. This is a technique many employ when in the crosshairs of satire, and the media must be careful not to fall for this argument hook, line, and sinker. While the editors at the Washington Post are free to edit how they see fit, in our view it would have been best to defend the cartoon once it had been published. Retracting it risks the appearance of caving to political pressure.

EDITOONISTS reacted individually too: John Backderf: “Now, Teddy is wrapping himself in his family and sticking his kids in ads, so he really can’t squawk much when satirists call him on it. But, of course, he is. Today he’s howling in outrage and exploiting the now-yanked cartoon as evidence of the…. queue scary music… LIBERAL MEDIA! ... So, in other words, the Post editor walked face first into that one. All he did was give Ted a giant gift-wrapped media blast for Christmas. Well done.” Clay Jonz: “Ted Cruz is upset and very angry. I know that's not breaking news and he's usually upset and angry, but this time it's for an interesting reason and an extremely stupid reason. OK, that's not unique either and I'll try again. Cruz is mad at the ‘liberal media.’ Ah, screw it. ... [Telnaes] did not caricature the daughters or name them. ... The cartoonist didn't expose them [to political commentary]. Daddy did. Daddy is a hypocrite. Daddy is upset that someone exploited his children to make fun of him exploiting his children. How dare a cartoonists attack his children and draw them as monkeys. He said this was typical of the ‘liberal media.’ ... “Ted Cruz put his daughters out there. He gave them lines to call Hillary Clinton a Grinch. ... The Senator and his family were not attacked by the liberal media. Ted Cruz, not his children, was attacked by a cartoonist. The cartoonist is NOT the media. We're just a part of it. “Also, the cartoon is an opinion piece. It's not news coverage or reporting. Journalism, yes. But this is not the ‘liberal media’ coming out to get you. To state the entire media is represented by one cartoonist would be like me saying that because of Ted Cruz, every politician is a creepy, icky, awkward-goose-stepping, whiny, crybaby, friendless, Grandpa Munster looking, fascist pig. But I'm not gonna say that. “Other people have pointed out that you can't draw Obama's children as monkeys. Well d'uh. But there is a difference and it's quite bizarre that it needs to be explained to you. The president's children are black. [And blacks are often portrayed derogatorily as monkeys and apes.] Ted Cruz's children are not. It's a false equivalence. Stop being stupid. ... “Anyone who's half objective can see the cartoon is pointing out that it's Cruz who's treating his children like monkeys. The girls are not caricatured or named. It's a sharp poke at the candidate, sure, but watch the Cruz video where he uses his girls to take cheap political shots and tell me the cartoon isn't making a fair point. “Hiatt was lame and did Ann wrong when instead of backing her up he pulled the cartoon— and in the process helped Cruz raise a bunch of money. He succeeded in making himself look incompetent and spineless at the same time. Stupidity all the way around.” Steve Benson: “What a joke: The last line in the Cruz tv political parody has one of his own daughters parroting his right-wing political propaganda to advance his presidential carnival tour. Put another way, Cruz the Calculator used—and abused— his own kids by setting them up as commercially-designed pipelines for spouting his pre-programmed, pre-junior high parroted talking points. It’s like used car dealers trotting out cute kids to sell their clunkers on late -night cable tv ads. “Spare me the cries of the ‘wounded.’ With huge dollops of faux outrage oozing out his ears, Crazy Cruz asserts that no one beats up on little girls. Even crustacean Cruz is at least momentarily smart enough to know that Ann wasn’t going after his kids. She was going after Terrible Ted’s shameless and manipulative employment of his minor daughters to lay the way for his road to the White House. As definitive proof of cash-in Cruz seizing this controversy to gin up donations, his campaign HQ has now sent out a fund-raising letter begging for $1,000,000 to fight off cartoonist evildoers. Meanwhile, some bobblehead on FOX Booze is claiming that ‘The Media’ should not be attacking political candidates. Hello??? This joke of a talking deadhead should attend an AAEC panel specially designed for elementary school children so as to help conniving Cruz internalize the basic ABCs of editorial cartoons—namely, that they are signed personal opinion pieces, appearing on the viewpoint pages, not in the news section. This is nothing more than typical, far-right, uninformed frothing—another gimmick to inflame the mob against the ‘liberal, lamestream media.’ “Ann, you did a great ’toon— even if your delete-buttoned supervisor claims otherwise—a convenient come-to-Jesus move that followed the Washington Post’s initial positive impulse to defend your work, before shortly giving way to the social conservative cave thug crowd.” Tom Spurgeon: “This is kind of a mess, the unfortunate parts of it coming from the Washington Post. The esteemed, award-winning cartoonist Ann Telnaes made a cartoon about Ted Cruz using his children in a campaign by portraying the surging presidential candidate as an organ grinder and his kids as the organ grinder's trained monkeys. Cruz responded with the typical ‘leave my children alone’ rhetoric that's been a part of every modern presidential campaign. ... Conservative media ran with that message and criticism for the choice of depicting the girls as monkeys, as if the point of the cartoon were ‘Look at those monkey-children’ rather than Cruz's cynical deployment of them as props. “I'm seeing a lot of headlines and articles stating the cartoon is about Cruz's kids rather than the candidate's use of them, so I'm guessing any reasonable distinction being made there is 100 miles in the rearview mirror at this point. It's a different world for editorial cartooning with campaigns leveraged by social media against not-really-trusted-by-anyone mainstream organizations. Everyone please be careful.” And

words alone didn’t satisfy some of the brethren. At the corner of your eye, a

few editoon responses. At

the lower left, John Cole’s cartoon addresses a different matter altogether,but I can’t resist using it here to capture the essential sliminess of Cruz.

Cole has Cruz’s slime spelling out the fear the candidate is fostering with

terrifying characterizations of Syrian refugees. That makes the fear itself a

form of slime. But I rejoice in the vision of Cruz as a slime-spreading worm. I

would like to do something similar, but all I have so far is the preliminary

sketch of a caricature you see here. SCORING PLAYBOY The

January-February 2016 issue of Playboy is, they claim, a double-issue,

but with only 148 pages compared to the usual allotment of 125-140 pages, it’s

scarcely twice as large. It does have two Playmates, though—plus the roster of

the year’s damsels lined up pictorially for Playmate of the Year and Pamela Anderson in all her naked glory, revisiting Hef’s mansion in California.

All naked. All nude. In defiance, as it were, of the forthcoming no-nude

regime, to which the last page in this issue refers (seen here at the left of

the Pamela cover). Cartoons, however, did not fare so well. You’ll recall our alarm hereabouts at the last two issues which were barren of the small cartoons in the back of the book. Only full-pagers in those issues, and not many of them. This issue’s full-pagers number a paltry 6, but that’s within the usual range. And the small cartoons are back. Not many of them—just 5—but they’re here. The ratios: 1 full page cartoon for every 25 pages in the magazine; 1 small cartoon for every 30. Disgraceful. The usual ratio of small cartoons to page count is in the range of 1/15 - 1/20.

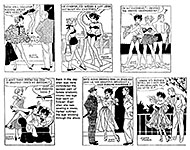

SOME LANG SYNE And a Cup O’ Nog for the Season TIS THE SEASON FOR CHESTNUTS by the fire. In song and custom, chestnuts by the fire are roasted. But we’ve convened this meeting not to roast chestnuts but to warm ourselves before the freshly kindled flame of fond recollections of them. For these chestnuts, old and not-so-old, are the stuff of anyule memory, and all of those are the best kind. Or they should be. In one of syndication’s older traditions, the Newspaper Enterprise Alliance has every year served up to subscribers to the NEA package a special holiday comic strip that ran for the three weeks just before Christmas, ending on Christmas Day. When I first took notice of this Yuletide ritual in December 2001 (Cartoonist PROfiles, No.132), I said that Ernest L. “East” Lynn, who was dean of comic art at NEA from 1924 to 1964, claimed the Christmas Strip had started before his time. By that reckoning, the NEA ritual was then in at least its 78th year. But maybe not. In the earliest years anyone else can remember, the Christmas Strip was not, apparently, a strip at all but a comical drawing advising how many shopping days remained before Christmas. Later, then, it developed into that three-week continuity of fond if imprecise memory. The Christmas Strip was usually produced by NEA cartoonists who ladled out this cup of seasonal cheer in their so-called spare time while also doing their own features. Walter Scott, whose regular gig was The Little People, probably brewed more Christmas Strips than anyone else: his byline was on the feature for about a decade, beginning in the early 1950s. Mad cartoonist Wally Wood is one of the rare outsiders to produce the strip: in 1967, his offering was entitled Bucky’s Christmas Caper and, typically, was mulled in space ships seasoned with the sf gadgetry the cartoonist was so adept at depicting. In the visual aids hereabouts, we revisit a few moments in these strips by way of decking the halls at your house with festive images of Christmases past.

EVER SINCE I WAS A KID, I’ve enjoyed the special strips cartoonists produced for Christmas. Some of their motivation was sheer good will. But in most cases, that was supplemented by a less sentimental fact about syndicated cartooning. Many newspapers in those days did not publish on Christmas Day, so storytelling (or “continuity”) strips faced a dilemma: how could they maintain the continuity of their stories if the Christmas Day installment was missing? The solution was simple. All the storytelling strips interrupted their stories on Christmas Day and inserted a special “Merry Christmas” strip. The readers of papers that published on Christmas Day got the special holiday greeting strips; the readers of papers that didn’t publish on that day didn’t feel that they’d missed some key element in the strips’ stories when the stories resumed on December 26—because there was no December 25 story element. Over the years, as sensitivity to readers who were not Christians increased, the special Christmas Day strips slowly disappeared. Some cartoonists no longer produce anything special for the holiday. But many do. For years, I’ve clipped out memorable Christmas Day strips and filed them away, never again to see the light of day or the gleam in my eye. I did it again this year, but this time, I’m showing here some of the ones I clipped. I begin with the more-or-less conventional seasonal greeting strips and progress to the less conventional—even unconventional or off-the-wall—albeit still attuned to the holiday.

I particularly like the reindeer poop gag in Over the Hedge by T Lewis and Michael Fry—and Robb Armstrong’s racial delight in Jump Start, with which we conclude the festive part of this posting.

MOVIES Once again, a funnybook superhero made the cover of Entertainment Weekly, the “Special Double Issue” of January 8/15, devoted to “sneak peeks at 2016's hottest movies, tv shows, and more.” Right there on the cover—Benedict Cumberbatch as Doctor Strange. I haven’t been particularly fond of Cumberbatch’s portrayal of Sherlock Holmes lately, but as Doctor Strange he may do very well. I should have expected that something was afoot for Strange when Marvel started yet another new title devoted to the Sorcerer Supreme. The book is clearly intended to pave the fan road to the movie, due in theaters next November. And the movie is undoubtedly going to be an over-the-top feast of special effects—an attempt, I suppose, at reproducing in motion what artists Bachalo, Townsend and Vey have done so expertly in the comic book. EW also takes a peek at the Batman v Superman flick due in March; “X-Men: Apocalypse,” May; the new season on Netflix’s Daredevil, March; and “Deadpool,” February—more of which, anon: ■ “Deadpool,” the movie based upon the Marvel comic book anti-hero, is coming to a theater near you, saith Stephen Rebello in Playboy. “Are you ready for an r-rated, deeply twisted X-men spin-off in which the disfigured ex-Special Forces hero lets you know he’s aware he’s a character in a superhero movie and blurts out whatever is on his sardonically funny mind?” Co-star T.J. Miller says: “Rather than water down the comic book, they ramped it up and went for it. It’s a complex, dense film with comedy so far left of center that it makes fun of comic-book movies. At the same time, it’s a satirical superhero comic-book movie itself.” ■ A movie based upon Jules Feiffer’s Playboy cartoon, Bernard and Huey, is en route to the big screen, with an original script and new drawings by Feiffer. Production of the Kickstarter backed comedy starts in the spring.

BLUE-EYED BIRTHDAY Frank Sinatra was born 100 years ago on December 12, and various of the media have taken notice, celebrating the occasion. I was not a Sinatra fan until after he died, which occurred on May 14, 1998. I heard the news on my hotel room tv. I was in Detroit, attending the Motor City Comic-Con. Sinatra wandered into my life only once before that. It was in New York in the Number One Bar at the foot of Fifth Avenue, just a block north of Washington Square; since, defunct. It was in the fall of 1959, and I was in New York, hoping to crash into the magazine cartooning biz before the draft spirited me off to army life. One evening, I sought solace in the Number One Bar. I had a martini and sat, by myself—I wasn’t with anyone during this Big Apple adventure—and heard Sinatra on the jukebox. My recollection is that he was singing “Strangers in the Night,” but that couldn’t have been the song because he didn’t sing it until several years later. Whatever the song was, it seemed appropriate to my forlorn state of mind (I wasn’t yet successful at crashing, or even seeping, into the magazine cartooning biz). All the rest of my memories of Frank Sinatra came along, as I said, after he’d died. Ditto my appreciation of his music. And here are some of the non-singing memories—the ones in which he is quoted. Or someone is quoted about him. ■ Once challenged by his doctor, Sinatra admitted to consuming three dozen drinks a day. The doctor, horrified, asked how he felt each morning. “I don’t know,” said Sinatra. “I”m never up in the morning. And I’m not sure you’re the doctor for me.” ■ The witticism that knocked Sinatra off his chair in spasms of laughter is the old Joe E. Lewis gag: “You’re not drunk if you can lie on the floor without holding on.” ■ Tony Bennett, reminiscing about Sinatra after his death: He’ll miss ol’ blue eyes, he said, but for those who love Sinatra from afar, “there will be no void. You see, it’s not that way with musicians. They leave behind the music, which will live forever. We’ll never lose Sinatra.” He paused, then went on: “I’m reminded of the day Gershwin died. One of his best friends was told about it, and he just stared. ‘Gershwin died,’ he said. ‘Gershwin died?’ And then he said, ‘I don’t have to believe that.’” ■ Sinatra’s last song performed in public: “The Best Is Yet to Come.”

EDGE CITY ENDS Terry LaBan always wanted to do a syndicated comic strip. "That was my childhood fantasy," he told Samantha Melamed at philly.com."And I got to do it,” LeBan went on. “But I got to do it just when everybody had stopped paying attention." And now, LeBan has stopped appealing for attention. The comic strip he and his wife Patty produced for the last 15 years, Edge City, stopped on Saturday, January 2. LaBan, who has freelanced as a cartoonist and illustrator since 1986, gave several reasons for ending the strip: the work was exhausting, the circulation of the strip was not enough to make it financially rewarding for either its creators or King Features, which distributed it (to only a few dozen newspapers), and comic strips as a medium no longer have the cultural influence that he, all his life, had expected his work to have if it were published in a newspaper. Next time (Opus 348), we’ll take an extended look at LaBan’s reasons for ending Edge City, and we’ll post the strip’s last week, a unique sequence: the LaBans wrote a special finale, and most comic strips do say farewell when they leave.

ODDS & ADDENDA Holding a single prisoner at Guantanamo Bay costs $3.3 million per year, more than 40 times the cost of holding a prisoner in a “supermax” prison in the U.S. ... The combined wealth of the world’s richest One Percent will overtake that of the other 99 percent of the world’s population this year. The same study found that the richest 80 people in the world have collected the same amount of wealth—$1.9 trillion—as the 3.5 billion people in the bottom economic half of the global population. ... The average American woman now weighs 166.2 pounds, about the same as the average American man weighed in the early 1960s; since then, he has gained nearly 30 pounds, now weighing 195.5 (exactly what has happened to me; I must be the average American male). ... We have endured at least 351 mass shootings in the U.S. during the first 334 days of 2015, at least 12 during the first week in December. To qualify as a “mass shooting,” at least four persons must be killed or injured by gunfire. ... Holiday shoppers bought a record number of guns on Black Friday: the FBI processed 185,345 background checks that day, up 5 percent from last year—and the most ever in a single day. ... From 1977 through 2014, there were an astonishing 6,948 attacks on abortion providers, including 8 murders, 17 attempted murders, 42 bombings, and 182 acts of arson. ... Since 9/11, about 30 Americans a year have been killed in terrorist attacks worldwide—roughly the same number as are crushed to death each year by collapsing furniture. Incidentally, a gun-owner friend of mine tells me that “assault weapons” are outlawed in the U.S. The weapons of choice now for mass murderers are semi-automatic “assault-style” weapons, not actual assault weapons.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

MOTS & QUOTES “All we can do is travel hopefully.”—Line in “Downton Abbey”

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue.

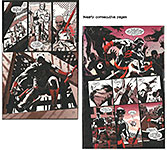

FRANK MILLER’S highly touted and long-awaited reprise of his Dark Knight vision has now launched with Book One (of an unspecified number of books), DKIII (Dark Knight Three) The Master Race. Sporting a stunning black-and-white cover, co-written by Brian Azzarello and penciled by Andy Kubert with inks by Klaus Janson, the book is an extravagant—i.e., expensive—production with glossy thick paper, a few pages that are nothing but shadowy photographs of dark, cloudy nights, and the astonishing inclusion of a comic-within-a-comic, a mini-comicbook bound into the larger enterprise—all an elaborate testament to Miller’s market value in the industry. No comic book artist that I can recall has ever been given this kind of treatment. So the question is: Is it worth it? Hard to say. I had to read Book One twice to make any sense of it, and what sense I can find is ambiguous at best. The opening gambit depicts a man running, fleeing the cops, who are about to shoot him down when they are attacked by a caped and cowled figure—all caught on camera and dissected by the news media, which now ponders the implications of the “return of Batman.” We are next transported to a jungle (probably in South America) where we see a man-bull on rampage and we watch as Wonder Woman, with a papoose on her back, breaks the bull’s neck, killing him. She then nurses the babe on her back and returns to her domicle, apparently a city or temple of an ancient civilization. Next we see what might be Superwoman floating over a frozen landscape. One page. Then comes the mini-comic, which is mostly about the Atom, who is musing about his fate as a superhero, addressing “Bruce” with his monologue. Superwoman then shows up, carrying the city in a bottle, Kandor, whose residents, she tells the Atom, are tired of being small. Then we’re with Lara, Superwoman, up North again as she contemplates a giant frozen Superman and hears Kandor citizens plead for help. Presumably, this sequence happens before the mini-comic encounter with the Atom. Finally, in the book’s closing sequence, Batman on a motorcycle is pursued by the police in several squadcars. When they catch up to him, a battle ensues. Batman is nicked by a bullet and downed. The cops then gang up on him, beating him to a bloody pulp. But

when one cop approaches the prone body, Batman seemingly revives and attacks

the cops surrounding him. At this point, police commissioner Yindel shows up,

pointing a pistol at Batman and telling him to stop. She bends over the

bleeding Dark Knight and asks: “Where’s Bruce Wayne?” And as Yindel pulls the mask off Batman, we see that Batman is—a woman. Who says: “Bruce Wayne is dead.” In this hodge-podge, we can discern, vaguely, a theme. The entire issue is a setup for the story to come. We see a police force somehow corrupted and diverted from its traditional purpose. And we see various superheroes who’ve given up their functions. (Wonder Woman a nursing mother?) And Bruce Wayne is “dead.” The stage is now set for his return. The artwork, by two seasoned veterans, leaves nothing to be desired. The pictures are models of clarity and competence. The storytelling echoes Miller at his best—alternating, as needed, between vast vistas and quick-cut fast-moving sequences, focusing on telling aspects of the action.

IN HIS PENCILS, Andy Kubert deliberately tried to evoke Miller’s technique in the previous Dark Knight books. “It was pretty harrowing,” he said in a “conversation” published in the back of several DC books. “Trying to come up with the spotting of blacks and getting more graphic, from what I’m used to doing. ... It was a lot of fun to do.” Klaus Janson, who inked Miller on the memorable run of Daredevil and worked with him on other projects, was both “incredibly happy and incredibly intimidated” to be working with him again, having hoped “secretly” that he would again someday. “There’s one reason why Dark Knight Returns was such a success, and that’s Frank Miller,” he said. “The wonderful thing about what Andy is doing,” he continued, “is that the pages are so recognizably Dark Knight. It takes place in the Dark Knight world, the pacing, the rhythm, the use of blacks as Andy mentioned—it’s all very reminiscent of Dark Knight. It looks like no other comic except Dark Knight. It’s a continuation of what Frank had established.” He went on: “It was the most nerve-racking job I’ve ever done. Because you want to make Frank happy, you want to make DC happy, you want to make everybody happy, and I really was sweating bullets on this one. It was the first time Frank and I worked together in 30 years, so there was a little pressure involved. I would ink a panel or two and look at it and think that it looks like Dark Knight, it looks like our stuff, and I was happy to be able to get to that point. But when I handed in the pages, I was very relieved!” Frank Miller told Abraham Riesman at vulture.com that it wasn’t his idea to return to the Dark Knight again. “That was not my call,” he said. “That was generated by them [DC].” But he’s glad to have had the opportunity to “play with the toys” again. “Batman in particular,” Miller said, “is such a versatile, fun toy. There are many different ways to play with them. They’re irresistible. We come along with new ideas and places to take them. So why not have another go-around? This is the third, and I intend to do a fourth. There’s endless fun to be had with [these characters]. Batman and Superman and the rest are such good ideas that they’ve lasted for generations and will last for many generations more.” The project got him so excited again, he said, that he wants to get back to it and do a fourth (and final?) book in the series. Why call the book “the master race”? “That’s an intense thing to put in the title of your story,” Reisman said. Said Miller: “Part of my job is to provoke. That means I’m getting your interest. And what else would you call a race of thousands of people with the power of Superman? If they were unleashed on the world, what would you call them? They certainly wouldn’t be a bunch of loyal servants.” Miller believes that many readers misinterpret his Dark Knight. “People thought I’d cast Batman as an anti-hero, when, in fact, I’d intended him as the purest of heroes. The idea was that he was, like Robin Hood, a character introduced in a time when the established order was wrong and had to be overturned. So he is, politically, a radical and a revolutionary out to overthrow a corrupt police state. It’s a very patriotic and loyal-to-the-law kind of story, but the established authorities were doing the wrong thing, so it took an outlaw to bring justice.” Miller has re-read the earlier Dark Knight stories, and he told Reisman that he was surprised at how “pissed off” he was when he wrote the first one. “I was extremely angry,” he said. “I was immersed in Dirty Harry movies, and I made Batman as angry as he could conceivably be. It’s fun to revisit because I’m still really angry, and I’ll see where that takes me now.” In addition to doping up the fourth issue in the series, Miller is reading a lot of children’s books these days. He wants to write and illustrate one—probably something in ancient Greek mythology. “But before that,” he said, “there’s a children’s book I’ve really wanted to do more than anything. I want to do a—this is a weird combination because it features my version of Robin [from the Dark Knight series], Carrie Kelley, but it’d be her cast as a Nancy Drew character in an illustrated mystery novel for children.”

IN THE FOURTH ISSUE of the new Archie, we learn what the “lipstick incident” is and how it somehow caused a deep rift between Archie and Betty, who, until then, had been boon companions since early childhood. In the incident, Betty dresses up—glamorizes herself by putting on a sexy gown and lipstick—and Archie is put off because he expects her to be his buddy, his sexless playmate of yore.

In other words, S-E-X has arisen, as it usually does when a member of the species is passing through puberty, and S-E-X makes the old buddy relationship impossible. Nicely conceived and evolved by writer Mark Waid. This issue marks the debut of the new Archie artist, Annie Wu, whose drawing style jars. She doesn’t draw in the customary Bob Montana/Dan DeCarlo manner any more than Fiona Staples did, but Wu’s style is uneven, her lines inconsistent from panel to panel. Sometimes, she deploys a heavy, bold line; other times, a wispy fine line. Her manner works passably in rendering close-ups; but for distance shots (like panels 3 and 4 on the left-hand page of our visual aid), it limps badly, especially in contrast to the boldly lined pictures. To further compound the error of selecting Wu to draw Archie, her lines are ragged, sketchy, as far from the traditional smooth manner as it is possible to imagine. This issue includes a vintage story from Archie Comics No.36 (1949). The contrast is startling. But the contrast between Staples and Wu is even sharper, as we hope to convince you by including Staples pages next to Wu’s in the accompanying illustration. There is no comparison: Staples seduces; Wu assaults.

ANOTHER BOOK in which the visuals have changed violently is the new Daredevil. In Charles Soule’s story, DD is back in New York, this time as an assistant district attorney. In the opening sequence of No.1 of the relaunched title, Daredevil saves the life of a star witness in a forthcoming trial involving one of the top lieutenants of the Chinatown crime boss, Tenfingers. The encounter with Tenfingers’ thugs ends with all of them prone and DD victorious—DD and his trainee, Blindspot, an Asian fighter, who, we see on the last page of this issue, may be Tenfingers’ agent. We also learn that somehow (unspecified) Daredevil has arranged for the entire world to forget that he and Matt Murdock are the same person. Everyone has forgotten except Murdock’s partner Foggy, who resents Daredevil involving him in his plans. But

it’s Ron Garney’s drawing that enlivens this issue. His style is in

sharp contrast to the liquid line of Chris

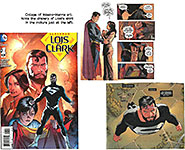

DC COMICS has just finished re-tooling their entire funnybook line in order to eliminate the innumerable parallel universes with their compounding confusions, and then here comes Superman: Lois and Clark in which we find our title characters married, with a newborn son, living on a different Earth, Telos, where Superman flies with a full albeit neatly trimmed beard but no cape. The narrator is Lois, written by Dan Jurgens, and most of the issue is devoted to acquainting us with the Kent family’s new circumstance. Fairly tame stuff, and since the principal characters are known to us, we don’t need to apply the usual criteria for a first issue—although the cliffhanger here, the final page that introduces a new, threatening villain, is a cliche. The

thing to remark about in this production is the exquisite artwork of penciller Lee

Weeks and inker Scott

HAVING READ THE

FIRST THREE ISSUES of Captain America White, I remain unimpressed. Jeph

Loeb’s story takes us back to the action of World War II and focuses on

Cap’s training of Bucky and their bickering with Sgt. Fury,

HUCK’s eponymous hero is a big hulking strong

guy who goes around doing good deeds for the sheer pleasure of it—he pulls a

neighbor’s truck out of the ditch, removes a stump that another neighbor’s

tractor can’t budge, takes out the trash for the whole town, buys lunch for

everyone in line behind him, and he goes to North Africa and frees 200 girls

taken captive by Bobo Haram. The first issue opens with a prolonged silent

sequence during which we see Huck dive off a cliff into the ocean or a big lake

where, underwater, he finds a woman’s necklace that she thought she’d lost in

the garbage. We meet a couple women, one a new arrival to the town; and the

other is telling her about Huck, The book is a series of completed episodes—each of Huck’s good deeds. Thanks in part to RafaelAlburquerque’s supple line and Dave McCaig’s modeling colors, we like Huck, a perpetually cheerful fellow. And Mark Millar’s story both introduces us to the character, his personality, and brings us to the cliffhanger that ends the issue. I’ll be back.

IN THE GODDAMNED, r.m. Guera draws Jason Aaron’s novel conception—a comic book version of the life of a character from the Bible’s Book of Genesis. In the opening sequence, we see a naked man arise from a mudhole, and then, for the next seven mostly silent pages in this first issue’s completed episode, he decimates a mob of “cave men” who have tried to kill him by throwing him in the mudhole. Although he is occasionally wounded during this confrontation, he is instantly regenerated and kills all of the thugs and then constructs a wardrobe for himself from the shreds of their animal-skin clothing. He goes wandering off, muttering to himself about his life: “I had a family once, but it didn’t work out.” He remembers getting angry too easily. He remembers killing his brother. And we realize the page before Aaron’s captions reveal his name that he is Cain—“son of Adam, the man who invented murder, the man who cannot die.” The full title of this first issue, “Before the Flood: Part One, The Mark of Cain,” isn’t given until the end of this book in order to preserve the mystery of the naked killer’s identity. But just before the last revelatory page, we meet Noah, “lumberjack, trapper, shipbuilder—man of God,” who is scouring the countryside for pairs of animals. Aaron has taken hints from the Bible story and elaborated on them. If Cain invented murder and is condemned to wander the world, what will he be doing as he wanders? More killing perhaps. And if his condemnation lasts, as is intimated in the Good Book, forever, then he must be impervious to disease and the kinds of disaster that would kill him. He may very well be the world’s first superhero. In his juicy drawings, Guera pulls out all the stops, deploying every graphic device possible to portray the primitive world Cain wanders in and the brutality of its population (yes, brutal—it’s before civilization, and these are the people who are so evil that God decides to drown them all and begin again; and by the looks of things, Noah is not much better than the rest). Guera’s gritty pictures are soaked in blood and coated with the grime of living in a desert. His layouts strain and break free from a regular grid during Cain’s assault on the thugs; then pages return to a regulated normal as Cain wanders off, muttering to himself. Delicious as the pictures are, it’s Aaron’s story—his elaboration on the hints in the Bible story—that fascinate and will bring me back.

ARCHIE’S SUPERHERO LINE, Dark Circle Comics, introduces us in The Shield No.1 to the new bearer of that mantle, who, in keeping with the convention-shattering mode of the company’s present editorial direction, is a woman, Victoria Adams. The storytelling mode is episodic, alluding to the various adventures that the Shield has had through history, starting with the Revolutionary War, as narrated by Adams herself, as she remembers events in her life while, in “today’s” Washington, D.C., she escapes from police custody, where she wound up after causing an auto accident in order to capture a purse-snatcher. Her flight across the city is interrupted when she stops to foil a home invasion, the only complete episode in the book. She suffers somewhat from amnesia, due perhaps to the trauma of the auto accident, but as she flees, and when she reaches the momentary refuge offered by a reporter interviewing he at the police station, she begins to remember. She has been reborn as the Shield the reporter tells her. Hovering over the entire issue is a plot to capture her being run by a goateed extra-agency operative. His armed and menacing minions catch up to her just as she remembers who she is. The

concept and story by writers Adam Christopher and Chuck Wendig is

novel, and their execution is Over-all, worth another look.

THE ALL-NEW

Hawkeye continues in the mode established by Matt Fraction and David Aja Ramon Perez draws in much the same bold-line manner as Aja

for about half the story, the “now” part, which takes place 15 years after the

Fraction-Aja series. That “now” part alternates throughout this first issue

with “twenty years from now,” when Clint Barton, the first Hawkeye, has a beard

and long hair in a ponytail and wears a hearing aid. For this period, Perez adopts

a sketchier, fineline style through which pencils occasionally show. The “now” strand relates how Clint and Kate Bishop, the other Hawkeye, split; in the “twenty years from now” strand, we learn that Clint retired from superheroing to live a reclusive life in his brownstone while Kate continued the fight. The split narrative is the issue’s complete episode; it shows that they split because of what is essentially a conflict of personalities. Twenty years later, Kate reaches out to Clint, saying they must reunite in order to “fix” a disaster in China that came about because of what they’d done when they were a team. They go to China and, on the last page of this issue, are attacked by the Mandarin, whom they presumed to be dead. Kate is knocked out, and Clint holds her in his arms as an image from twenty years before—an image of their split—hovers in the background. At the end of this issue, in other words, writer Jeff Lemire manages to bring both strands of his narrative together in a touching last-page finale. With the Mandarin looming over Clint and Kate, we have the cliffhanger that should bring us back. Nicely done.

THE ALL-NEW WOLVERINE is a woman, Laura Kinney, who was cloned from Logan, the original Wolverine, who has “fallen,” so Laura takes up the mantle. This first issue is almost all fight scenes, with which writer Tom Taylor no doubt intends to establish Laura’s fighting bonafides. The issue opens with Laura in the midst of some sort of street confrontation in Paris; midway through the issue in its completed episode, she jumps from the top of the Eiffel Tower in pursuit of a masked baddie, is caught by the X-man Angel, who then drops her on a drone, which Laura knocks out of the sky. In both battles, Laura is injured and must sit still afterwards to let her healing factor kick in. The baddie she’s been pursuing is dead, and Laura, removing the baddie’s mask, says, “She was me.” Then she and Angel take off to find the rest of “them,” whom Laura wants to save. It’s an action-packed tale, proving Laura’s mettle, but it includes a dream-like interlude with Laura talking to Logan about her function as Wolverine, and when Angel shows up, it’s clear theirs is a wannabe romantic relationship as well as an X-man bond. The issue is, in other words, jammed with story—and “history.” Contributing

to this excellent “debut” is the muscular artwork of David Lopez and David Navarrot—“old school” stuff, flexing line, waxing thick and waning

thin, figures modeled with shadow rather than feathering; layout grid distorted

for scenes of violent action but also paced for dramatic impact when needed. All of which is in sharp contrast to the second issue of James Bond, wherein the pristine artwork of Jason Masters prolongs the impression that the adventures of Ian Fleming’s super spy are taking place in a sterile hospital. Even as Bond is surviving an assassination attempt, the scene is clean as an OR. And then we have another in the long line of attempts to revive Doc Savage. The original pulp Doc Savage (as I understand it from hearsay, having never actually read any of the inaugural tales) was surrounded with able specialists, each capable of headlining his own book. All of the comic book revivals I’ve encountered try to preserve that ambiance but usually fail. Maybe lifelong Doc Savage fans feel differently. But there’s nothing in the current revival that appeals to me. And Cezar Razek’s artwork is another of the prissy style that renders every wrinkle with no attempt at emphasis. It’s too “realistic” in a rendering sense: it visualizes everything but the result is diagrammatic rather than photographic. The best plan with Savage is to abandon all the accouterments of the original and let the man stand on his own, a solo act with a torn shirt and brawny arms. And show him in action rather than sitting in the boardroom in a three-piece suit running his operation as if it were a government bureaucracy. Erik

Larsen’s Savage Dragon No.209 (probably setting a longevity record

for the production of a comic book title by a single cartoonist) includes one

of the most horrific sequences I’ve ever seen. In this issue, Malcolm Eugene

Jackson Dragon (Savage’s son) marries his girlfriend, Maxine Jung Lai, who is

pregnant with (presumably)

QUOTES AND MOTS “Sin boldly: the Lord loves a sinner.”—Attributed to Luther E.B. White, according to George Will, reportedly said that “the most beautiful sound in America” is “the tinkle of ice at twilight.” Poetry.

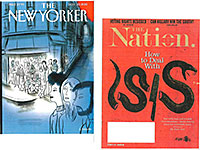

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy WE PONDER HERE,

whenever we meet under this rubric, the power of images to make pithy comments

on the passing scene. Usually, that means looking at and appreciating the

verbal-visual artistry of editorial cartoons. But this time, we start with the

images on the covers of recent issues of two magazines, The New Yorker and The Nation. At The Nation, for its December 14 issue, the editors picked a symbolic representation of ISIS—a serpent, sliced into pieces. It evokes the old superstition that even if a snake’s head is severed from its body, it won’t die until sunset. It will, however, die. And that’s the point: cut into pieces, the snake will die.

CONGRESS WAS IN

THE NEWS a couple weeks ago when it passed the “spending bill.” Although the

new Speaker of the House, Paul Ryan, was given credit for shepherding the law

into being, the retiring Speaker, John Boehner (pronounced “banal”), according

to report, actually engineered its passage before he vanished over the horizon.

In our first visual aid, we start off with Randy Bish’s much earlier

superlative caricature of Boehner, which, oddly—even with its shimmering glow—

seems appropriate today. Continuing in a clockwise rotation, Matt Davies supplies an image that reveals the contradiction in Ryan’s insistence on having weekends at home with his family in Wisconsin—a condition of his taking the Speaker’s job. He apparently values family life for himself while persistently opposing bills that would address the needs of other families. Finally, changing the subject somewhat, we have Mike Luckovich depicting Congress’s purposeful reaction to the latest mass shootings. The image here is not the potent element: the circumstance and the utterance tells the tale. In

our next exhibit, Matt Davies is back at the upper left, addressing the

stunning contradiction in funding social welfare programs. Finally, at the lower left, Pat Bagley launches for us this month’s attack on the wholly irrelevant Republicon Party with a telling metaphor showing the GOP as a hot-air balloon that’s lost its moorings to reality. Apt. Not only the Right Wing-Nuts. The so-called “news” media has also lost something—all perspective, all sense of reality and objectivity. In less than two months, three of the nation’s least representative state populations will contribute hugely to determining the presidential nominations of the two political parties: Iowa, a largely rural and highly evangelical population; New Hampshire, a rock-ribbed self-reliant population, leaning more conservative than not; and South Carolina, for whose citizens race is still, as it was when the state was first to succeed from the Union, a major preoccupation. The Confederate Battle Flag may have been removed from the statehouse grounds, but the overweening sense of white supremacy that it embodied no doubt remains. And so nut cases of three dimensions will determine the future paths of those running for the dubious honor of being Prez. Those who show poorly in these primaries will drop out of contention. They’ll lose funding; donors will evaporate. And some of the drop-outs might make much better presidents than those who remain. The drop-outs did not attract the votes of rural evangelicals, tight-lipped New England conservatives, or racists of the die-hard Old South. And those who did attract the votes of these retrograde populations will go on—through the rest of the primary season until they are nominated. And then one of the religious zealots, backward-looking conservatives, or racists might be elected Prez. Sad. But the “news” media persists, covering every known or imagined aspect of the carnival of the GOP primary season even though most of the festivities have nothing to do with practicalities of governing in a country that has managed to profoundly divide itself. As Eric Alterman has it in The Nation (December 7), the Republicons “have allowed their party to be captured by an irrational, irredentist faction with virtually no concern for public opinion, honest governance, or even empirical reality. ... In the hopes of appealing to angry, ill-informed and xenophobic primary voters, Cruz, Rubio, Bush and Fiorina are all adopting positions that are not only beyond the boundaries of the beliefs of the vast majority of Americans but also contrary to the laws of physics, economics, and, of course, common sense.” Even members of the mainstream news media “run interference for—and therefore legitimize— the same dangerous nonsense in the guise of allegedly objective reporting. The mainstream media’s coverage of every Republican debate so far as had the effect of subordinating reality to fantasy.” Then Alterman quotes Damon Linker, former editor of the theocon magazine First Things, who said: “How could any well-read man or woman, regardless of ideological commitments” observe the “unprovoked and petty anti-intellectualism ... nonsensical, conspiratorial musings ... xenophobic promises,” and “dumpsters full of dubious assertions” that characterized the Republicans recent debate “and not come away disgusted”? “No doubt,” Alterman continues, “many Republicans are privately wondering the same thing. And yet it works: the crazier these guys sound, the more popular they become.”

IN THE NEXT

VISUAL AID, David Fitzsimmons gets us off to a rollicking start with a

generous sampling of his superlative caricatures, each one a triumph of design. At the lower right, Gary Varvel tackles the same theme with another Star Wars line-up of the Grand Obstructionist Pachyderm candidates. Left-to-right, the names on the podiums are: Yoda Kasich, Princess Fiorina, Rubio Skywalker, Carson 3PO, Darth Trump, Cruz Solo, Jeb-Bacca, Christie the Hut, and Rand2-D2. Insight, yes—but more fun than profundity. And it’s satisfying to see Varvel’s caricatures, tweaked slightly to make them fit the Star Wars molds. Then Tom Toles does something he rarely does: he supplies a actual caricature of a politician to make his point: in this case, he shows how Carson’s comments on shootings reveal him to be an escapee from some nearby asylum with his keepers rushing to take him off the streets. In the aftermath of the shooting at Oregon’s Umpqua Community College, Carson no doubt endeared himself to gun enthusiasts and the National Rambo Association by saying that if facing a gunman aiming to kill him, he wouldn’t just stand there: he’d attack the gunman. Carson went on to say that the Holocaust of Jews in World War II-era Europe might have been averted if the Nazis hadn’t taken guns away from all their opponents, leaving them defenseless. Jews did fight back, though: they mounted at least 100 acts of armed resistance in Warsaw and throughout Europe, but individual Jews with guns could do little to stop the Nazi juggernaut—millions of soldiers and special police, mechanized Panzer divisions, and Luftwaffe airplanes. The parallel to some gun nut beliefs in this country is inescapable: many gun enthusiasts maintain that they own guns in order to be able to defend themselves against a rogue government, which, the gun nuts believe, will someday turn on us citizens and impose a dictatorship. And just how effective will these lone wolves, armed to the bicuspids, be against massed tanks and an air force, guided missiles and bombs? As European Jews proved, not very. Just another foolish delusion held by too many ignorant people. Our

next exhibit starts with a critique of the Republicon debates. At the lower left, Henry Payne comes close to explaining The Trump phenomenon. Depicting Trump and Hillary sharing the host job at “Saturday Night Live,” Payne characterizes Trump’s debating skills by recalling a scrap of vintage SNL dialogue. Trump rudeness, however, doesn’t explain his role in this presidential season, a role which nonetheless Payne’s choice of venue subtly reveals.

THE PUNDITARIAT, THE GASBAG CLASS, is having an absolutely unmitigated ball. The Big Blowhard Donalt Rump gives them something to ponder over endlessly. And so they oblige. They all wonder at his staying power. Why is he still a factor at all? Because gasbaggery gives him airtime, the most valuable commodity a performer can have: it is the breath of life to his candidacy. Still, on all sides, the commentariat is aghast. Not by any means speechless but aghast. They call him names. “A misguided missile ... subject to farcical fits.” Whatever the Trumpet is, he is not a stirring example of cogency at the podium. He doesn’t make statements, or even sentences. He has outbursts, campaign flatulence. And, yes, it stinks. Ruth Marcus at the Washington Post writes of his “overweening sense of entitlement, the conflation of money and intelligence, and the belief that wealth is a virtue in itself. The obsessive flaunting thereof. These qualities are not incidental to Trump’s presidential campaign. They are integral to it. The campaign is predicated on the notion that with great wealth comes great entitlement. His trumpeted billions constitute the primary evidence of his qualification for the presidency.” She goes on, quoting Trump announcing his candidacy: “‘I’m really rich. I’m proud of my net worth. I’ve done an amazing job.’” Even the imperturbable George Will falls into the Trumpery Trap and talks about him—in this instance, offering perhaps the most insightful of analyses (in italics): If you look beyond Donald Trump’s comprehensive unpleasantness—is there a disagreeable human trait he does not have?—you might see this: he is a fundamentally sad figure. His compulsive boasting is evidence of insecurity. His unassuageable neediness suggests an aching hunger for others’ approval to ratify his self-admiration. His incessant announcements of his self-esteem indicate that he is not self-persuaded. Now, panting with a puppy’s insatiable eagerness to be petted, Trump has reveled in the approval of Vladimir Putin, murderer and war criminal. Makes perfect sense to me. The Trump needs love. Donalt Rump, as E.J. Dionne at the Washington Post reminds us, is not “broadly popular.” Yes, he’s leading in the polls, as The Trumpet continually reminds us while talking about his favorite subject, himself. But “he leads only in a minority subset of the population—depending on the survey, (1) projected Republican primary voters or (2) Republicans combined with Republican-leaning independents. Neither of these groups represent a majority of Americans.” But the self-absorbed blow-hard thinks everyone loves him—because he needs them to. Everyone except, doubtless, Muslims. And Mexicans. And—? Calvin Trillin, bless his heart, “deadline poet” at The Nation, offers a new Trumpery poem, entitled “Trump Explains His Muslim Registration Project in Detail”:

Good management is what it’s called. No reason to be vexed. We’ll round up all the Muslims here, And then we’ll see who’s next.

All those pondering endlessly, fruitlessly, Trump’s candidacy think he’s a serious candidate. But no—Trump is an entertainer. He’s not a serious candidate: he is, rather, a serious satirist. His every remark—his exaggeration, his bigotry, his fear-mongering, his ignorant bloviating, his tireless narcisicism, his braggadocio, etc.—all at a satirist’s extreme for the purpose of emphasizing how idiotic modern political campaigning has become. Candidates will do anything—as The Trump repeatedly demonstrates—to keep their names in the news, a sound-bite-a-day. The more outrageous his pronouncements, the more headlines he gets—and his headlines elbow his competitors off the front page and into oblivion. Other candidates and their affiliated PACs have spent millions on expensive tv ads, according to Jill Colvin at the Associated Press. But “Trump’s campaign has reported spending just $300,000 on a sprinkling of radio ads. Instead, Trump has logged a whopping 22 hours and 40 minutes of free airtime from May 1 to December 15 on Fox News alone. ... That’s more than twice as much as any other candidate.” He gets attention by being outrageous, by being the spectacle that television dotes on. The Trump is the clown prince of candidates—and with a purpose. Everything he says and does ridicules the techniques and tirades of the political campaign in today’s jumbled politics. And as our next pages of editoons show, editoonists are playing along. The Trumpet has provided them with ample ammunition, something for them to throw at him every day. But the greatest gift is The Trump himself. His outlandish hair-do and his self-congratulatory wind-baggery. The Trump is made for caricature. In fact, he IS a caricature (another of his satirical jabs).

And Steve Brodner has been having a field day producing Trump caricatures—one of the best, Trump as hot air balloon. Given The Trump’s personality and the raging success of his satire, it is no wonder that he winds up on the cover of Mad—drawn by Mark Fredrickson and accompanied by Alfred E. Neuman, who, eager to get into the campaign himself, has adopted the sure-fire symbol of candidacy, the Trump comb-over. Inside this issue (No.537, February), we get the 20 dumbest people, events and “things” of the year, among which, Hermann Mejia’s delicious caricatures of the Republicon candidates at their Last Supper, The Trump (of course) presiding as the Party’s savior, hogging all the foodstuffs at the banquet. An image we’re not likely to forget. And its blasphemy alone will doubtless endear it to all Right-thinking Republicons. In

the last of this handful of visual aids on The Trump, we resume our usual round

of critique. So how are we going to keep Muslims out if we follow The Trump’s policy? Easy. When they try to enter the U.S., the customs official, after looking at their passport (which, if it’s like mine, does not declare the owner’s religion), asks: “Are you a Muslim?” If the hapless traveler says, “Yes,” he/she is barred from entering the country. If, desiring above all else to be admitted, he/she says, “No,” then he/she will be admitted. What could be simpler? Or more simple-minded. In short, typical Trumpery. The last two cartoons in this visual aid have some fun with The Candidate. In his comic strip La Cucaracha, Lalo Alcaraz creates a meaningful relationship between The Trump’s hair and his conduct. And at the lower left, Jeff Danziger deploys the final image from “Dr. Strangelove” to show just how self-destructively extreme The Trump is—at the same time, giving new suicidal significance to Trumper’s bellicose foreign policies.

TURNING NOW TO

OTHER ISSUES, those having significance rather than decibels, we have Matt

Bors turning in one of his bitterly but insightful ironic comments. Next around the clock, Tom Toles takes up the issue of global warming and reveals its consequences for future Christmases, which may well have to forego visits from Santa Claus if his North Pole headquarters melts away. As a second bounce, Toles makes Mitch McConnell, ever watchful for the welfare of his coal-producing home state, the “bad boy” who will get only lumps of coal in his stocking. He’s been bad, we assume, because the motive for his policy and utterances on climate change are self-serving—or, rather, serving his voting and donating constituents, the coal-mining industry of his state. Matt Wuerker turns to the Paris climate change talks and, borrowing an image from Thomas Nast, provides a comment about the international conference on the issue. And his national representatives, notice, are up to their knees in the water that’s melting from the planet’s icier regions. Finally at the lower left, we have Jen Sorensen, poking fun at a recent effort in New York City to reduce the threat of the naked female bosom. Toplessness is legal in the city, she tells us, but apparently authorities are discovering heinousness in the licentiousness and are objecting to nakedness. In reaction, various concerned parties resort to body paint to cover up the offending parts of the anatomy. Sorensen suggests a practical application of the Fear of Naked Bosoms syndrome. Along the way, she takes a poke or two at other absurdities in urban life. In

our penultimate exhibit from the last month or so, we begin at the upper left

with Drew Sheneman who provides a memorable image to illustrate the

consequences of a failure to tax enough to restore failibng infrastructure. In La Cucaracha, Lalo Alcaraz gives new meaning to the anyule greeting “feliz navidad”: the silhouetted Holy Family evokes memories of road sign warnings about, say, wildlife crossing the road. And in the context of our recent alarms over Mexican immigrants, the warning has a satirical bite, honed to a cutting edge with the reminder that the Holy Family was turned away from hotels that had no empty rooms and therefore might be depicted as “fleeing” (“feliz” almost sounds like “fleeing”). In sum, “feliz navidad” here is ironic: how is happiness possible if you and you family are not welcome anywhere? And you and your family are not welcome because we are warned against you —as if you are only so much wildlife on the highway. Next, Tom Tomorrow (aka Dan Perkins) examines the “war on Christmas.” As always, the comic strip format permits him to dwell on the subject, heaping up sarcasm after sarcasm as he goes, each addition serving to increase the exaggeration (and therefore the ridicule) of the severity of the claim that the “war on Christmas” is an assault on freedom of religion and undermines morality in general. Jack Ohman at the lower left turns the attack on the “war on Christmas” into an attack on the morality of Trump and Carson, both of whom have demonstrated a heavy-handed disregard for human rights (contrary to Christian charity) in their pronouncements about immigration. The “war on Christmas” is a huge joke, a concoction whipped up by Faux News and Bill O’Reilly for the sake of drumming up more viewers by picking something that the Religious Right can get all lathered up in opposition to. As a purely historical matter, the “war on Christmas” can be seen as originating with the Puritans, who fled England (and the Church of England) in order to pursue a better morality on this side of the Atlantic. The Puritans, America’s first fundamentalists, were firmly opposed to celebrating Christmas because (1) Christmas is not celebrated in the Bible, (2) many aspects of Christmas were adapted from Pagan holidays, (3) it was celebrated by the Church of England, which the Puritans rejected, and (4) Puritans felt Christmas should be commemorated by piety rather than merriment and fellowship. The Reverend Increase Mather, a prominent figure in early Massachusetts, wrote in 1687 that the way Christmas was being celebrated was “dishonorable to the name of Christ ... [spending the occasion] in Revellings, in excess of Wine, in mad Merriment.” Considering the Puritan opposition, it is no surprise, writes Simon Brown in Church and State (December), “that celebrating Christmas was forbidden in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In fact, from 1659 until 1681, anyone found to be celebrating Christmas there was fined five shillings (about $40 today).” Christmas continued to be neglected if not outright opposed until the 1800s. It wasn’t until the 1830s that some states made Christmas an official holiday. And the federal government was slow in recognizing the holiday: it was officially in session on Christmas every year but three between 1789 and 1857. Congress finally declared Christmas an official holiday in 1870. But the “war on Christmas” is no longer raging. No less a crusader for Christmas than Bill O’Reilly his own self declared that he had won the war. Last year on NBC’s “Late Night with Seth Meyers,” O’Reilly said: “I’ve been doing this for about ten years, and this is the only year we have not had a store that commanded its employees not to say ‘Merry Christmas.’ It’s over. We won.” Merry Christmas, kimo sabe.

FINALLY, ONE MORE ROUND OF SHOTS at Trumpery. He’s simply so rich a resource that he’s

endlessly inspired cartoonists to comment—on his outrageous policy

proclamations or his hair or both. It’s hard to ignore such comedic treasure

when it’s so conspicuously lying around. Steve Sack at the upper left unveils the hypocrisy inherent in GOP attitudes about immigrants and wages, using The Trumper as spokesman. Nifty caricatures. At the right, Steve Breen finds a new way to make fun of Rump’s hair style. Just for laughs. Below, Tom Toles engages in a little name-calling. “Huckster” is good. Trump is more that than he is anything else. And then at the lower left, Milt Priggee provides the only telling metaphor in this exhibit: Trump, kept aloft by wings labeled “racist, bigotry, scape-goating, fascist, xenophobic and demagoguery,” is likely to suffer the same fate as his mythical inspiration, Icarus, whose wings, once he got close to the sun, melted away, sending him crashing earthward. Nicely imagined.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS “All my life, my parents said, ‘Never take candy from strangers.’ And then they dressed me up and said, ‘Now go beg for it.’”—Rita Rudner about Hallowe’en “Baseball is what we were; football is what we have become.”—Political journalist Mary McGrory Missouri State Rep. Stacey Newman wants the same kind of restrictions for guns that Republicans have for abortions. She said the gun lobby has "purchased the Republican Party."

THE FROTH ESTATE The Alleged News Institution From Jenk Lloyd Jones, an editor of the Tulsa Tribune and one of the founder’s sons: “The best way for a newspaper to survive is to be loved. If you can’t be loved, be respected. If you can’t be respected, be feared. If your editorial page is so colorless it can’t arouse any of these emotions ... then you’d better watch out.” In Time, spring 1956.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping KING FEATURES

SYNDICATE is 100 years old this year, which may be the justification for the

muster of King Features characters in Blondie on October 25. Unfortunately for my theory, not all the characters are King characters. When I posted this on Facerbook, Charles A. Brubaker rattled off the non-King comics: Luann (Universal), B.C. (Creators), Jump Start (Universal), Arlo and Janis (Universal), Dilbert (Universal), Rose is Rose (Universal), Pickles (Washington Post), Garfield (Universal), Lio (Universal), Pearls Before Swine (Universal), and For Better or For Worse (Universal). Any more? Another historic moment in comic strips appears below Blondie. Paul Anderson’s farewell to his father Brad, who created the Marmaduke comic strip. We did an obit in Rants & Raves, Opus 344.

ZITS ONE DAY LAST FALL was beyond me. What’s

the joke? Who’s Kevin? His identity is clearly at the core of the comedy.

Tennis player? Sorry: I don’t keep up with any sporting event except the

Broncos football contests. Just don’t get it. And then we have a recent Close to Home by John McPherson. It’s an example of how a poorly conceived drawing can destroy the joke. The joke depends upon our seeing someone—ostensibly a person who’s just jumped out of the window of a burning building into a fireman’s net—bouncing up and down on the fireman’s net as if it were a trampoline and executing a series of wonderfully acrobatic stunts as he/she bounces. But because McPherson put a window just behind the bouncer, we can’t make out the bouncer, whose delineation is mashed into the window delineation to the visual confusion of both. If McPherson had left the window out of the picture, we could clearly see what is transpiring; as it is, we have to use a magnifying glass. Why did he feel compelled to put the window in there? Just to pair-up with the other window on the first floor at the right? The building is structurally sound without the second first-floor window. In Pluggers at the right, we have the answer to a question that has plagued mankind since the invention of the refrigerator light. A stunning instance of logical reasoning run rampant. Finally, at the bottom, a strip that made me laugh out loud: Jerry Scott and Jim Borgman’s Zits—which is always funny, but not always enough to make me break loose. It’s a gag that deviates wildly from the setup. Nothing in Pierce’s mathematical dilemma in panel 2 prepares us for his report of the answer to which his math apparently led him. What a hoot.

WHEN I POSTED

the aforementioned Kevin Zits on my Facebook page, Mark Fleck and

several others explained it all to me by saying Kevin was the name of the fly. The confirmation of Kevin’s identity continued in the next day’s strip, in which Pierce is flushing the deceased Kevin down the drain. But the strip is also historic: it is one of only two or three strips recently to depict a toilet. In a family newspaper!! We’re shocked. Shocked. Now, with three or four depictions, the taboo against showing this part of domestic plumbing has been thoroughly unhorsed. More toilets to come, no doubt. But how to explain the graffiti on the wall behind the toilet? What position did the wall scrawler have to assume to scrawl on the wall where he scrawled? Sitting backwards on the toilet? The scrawl is pretty low down on the wall. Maybe the scrawler was lying on the floor next to the toilet? On the remainder of this visual aid, we have instances of cartoonists’ playing with the medium, which I always rejoice about when I see it. In Garfield, Jim Davis gives the speech balloons actual comic strip substance, something Jon can push around instead of something simply “invisible” in the panels. In Frazz, Jef Mallett refers pictorially in the second panel to another strip, Chip Dunham’s Overboard, which features vintage pirates in anachronistic situations. But how effective an allusion is this? I don’t think Overboard is a widely circulated strip, which means that not many of Frazz’s readers are likely to make the association. The gag doesn’t need the connection to be funny, but the extra layer of humor is doubtless lost on most readers. But Mort Walker and friends in Beetle Bailey top the list of favorites in this posting (even though the strip is at the bottom of the stack here): two bad puns in one strip. Whoop!

AND SPEAKING of Mort Walker and Beetle, here’s an anomaly. The gray toning—called Ben Day in the olden days—is applied at the syndicate, not in Walker’s studio; so he was as surprised by the “measled” gray as I was. JUST BEFORE THE

PERTINENT HOLIDAY, Tom Batiuk took up the “war on Christmas” theme in Funky. I struggled with that song once, years ago. I did a Christmas card depicting a group of carolers who, in my initial plan, were singing “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen.” In a fit of politically correct sensitivity, I removed “God” from the caption because I suspected atheists would be offended; then I took “Gentlemen” out because women might be offended. My carolers, then, were singing “Rest Ye Merry.” Not bad, I suppose, but still ludicrous.