|

|||||||||||||||

Opus 346 (November 30, 2015). In the hopper this time, Rabbit Habiteers, we have reviews of works by and/or about comics icons— “The Peanuts Movie,” a new Peanuts book by Chip Kidd, Stan Lee’s graphic memoir, books about Will Eisner, plus the new Jughead and the latest masterfully done work by Sean Murphy, Tokyo Ghosts—just in time to make your Christmas Wish List that you’ll give your spouse. We also report on the Playboy purge, political correctness and racism in editoons, war cartooning, The System graphic novel by Peter Kuper, Flannery O’Connor’s cartoons, and recent comic books— Call of Duty: Black Ops III; Joe Golem, Gravedigger, All Star Section Eight, Citizen Jack and some editoons—and more, much more. We’ve listed all this posting’s content below. It’s a lengthy posting, and you doubtless don’t want to read it all in all its majesty. The ensuing list is intended to assist you in finding your way through Opus 346 so you won’t have to read it all in order to find topics that interest you. Instead of wading through the whole swamp, just scroll down the list, noting topics you’d like to read about, and then continue scrolling into the opus itself, stopping at those topics you noted that you wanted to spend some time at. Now, here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US The Playboy Purge Is On Filthy Underpants No More Understanding the Mess in Mess-o-potamia Political Correctness Strikes Again: Campus Newspaper Over-reacts More Racist Nonsense from the Right— Another Cartoon Willfully Misinterpreted Iranian Cartoonist Imprisoned Women’s Boutique Comique Mile High Is High Again Thinning the Ranks of Editoonists Some More Charlie Financially Vibrant, Spiritually Exhausted Death in the Funnies: Kit ‘n’ Carlyle & Dinette Set

Odds & Addenda Zunar Gets His Books Back Record Wimpy Kid Sales Rob Rogers Gets Berryman Brenda Starr Making a Come-back

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Reviews of—: Tokyo Ghost James Bond 007 Call of Duty: Black Ops III Joe Golem: Occult Detective New Jughead Debuts (Plus No.3 of New Archie) Gravedigger Dr. Strange All Star Section Eight Citizen Jack

PEANUTS GALORE Review of “The Peanuts Movie”

EDITOONERY Reviewing Some of Last Month’s Best Editorial Cartoons

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews & Coming Attractions, To Wit—: Cartoons for Victory When Comics Went to War (British) Another Eisner Biography Will Eisner and P.S. Magazine

BOOK REVIEWS Longish Critiques of—: Only What’s Necessary: Charles M. Schulz and the Art of Peanuts Flannery O’Connor: The Cartoons

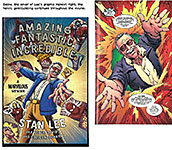

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Reviews of Graphic Novels—: Amazing Fantastic Incredible: A Marvelous Memoir (Stan Lee) The System by Peter Kuper

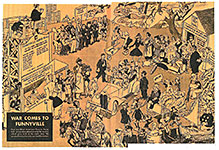

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE King Features’ Funnyville Endpapers

PASSIN’ THROUGH Just a Fond Note about Maureen O’Hara

Annual Report November 2014 - October 2015

QUOTE OF THE MONTH If Not of A Lifetime “Goddamn it, you’ve got to be kind.”—Kurt Vonnegut

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

THE PLAYBOY PURGE IS ON The December (“Christmas”) issue of Playboy arrived last week, and my dire imaginings at our last meeting seem to have materialized. While the number of full-page color cartoons is about the same as always (eight, this time, in a 130-page issue), there are none of the smaller cartoons that used to crop up in the back of the book. None. Nada. Just like the November issue. One of December’s cartoon women is naked, however, but that scarcely bodes well. The most represented cartoonist in this issue is Gahan Wilson, who scores two full-pagers this time, but he seldom pictures women, naked or otherwise. And there’s no Dean Yeagle this time. There are 8 small cartoons but they’re not in the back pages of the magazine: they appear in a Yuletide roundup, a two-page spread of “Classic Cartoons of Christmas Past”—a regular feature of the December issues, which, in the past, ran in addition to another dozen or so small cartoons in the back. Sadly, this issue looks to me as if Hugh Hefner is cleaning out his inventory of paid-for but unpublished cartoons in preparation for a new format in which cartoons do not play a part. Perhaps as some sort of fanboy compensation, this issue has an 8-page “graphic novel-ish” sequence. Written by move-maker Quentin Tarantino, it’s a “preview” of his new movie, “The Hateful Eight.” Illustrated by Zack Meyer, who, judging from these pages, has never done a graphic novel, it’s mostly talking heads, and the heads spout several speech balloons per appearance. Not exciting or even engaging. Hef may not understand how graphic novels are supposed to work.

FILTHY UNDERPANTS NO MORE With the

publication in September 2015 of the 12th Captain Underpants book,

author Dav Pilkey exacted some playful revenge upon those cranky

do-gooders who demand that his Underpants books be removed from school

libraries and classrooms. Those demanding an end to Underpants are usually

well-intentioned parents who wish to protect the purity of their offsprings’

lives by preventing them from encountering any of the actual world in which

they may, someday—but always too soon for some of their mothers and

fathers—find themselves. Although according to the American Library

Association, parents may seem to be the culprits in this regard, how can we

fault them for taking an interest in what their children are doing? Captain Underpants books are among the most frequently “challenged” books, ALA said in a September 29, 2015 article in Parade magazine by Heather Thompson. “Challenged” is an ALA euphemism meaning “ban this book.” The reason usually given for removing the excitable Captain from school bookshelves is “offensive language.” In Chapter 2 of Captain Underpants and the Sensational Saga of Sir Stinks-a-Lot, the aforementioned 12th, Pilkey vows that henceforth, “you won’t be reading any more words like heck, or tinkle or fart or pee-pee” in his books. Says he: “Those words are highly offensive to grouchy old people (GOP) who have way too much time on their hands.” In

supplying abbreviated initials for grouchy old people, Pilkey connects

(correctly) those who annoy him to a political party, and he goes on to list

various topics that he has included in the book “especially for them”:

references to “health care, gardening, Bob Evans Restaurants, hard candies, FOX

News, and gentle-yet-effective laxatives.” The end of the book, though, concludes with an outcome sure to irritate his foes—at least one same-sex couple. So take that, GOP. Alas, the gaiety is just one more provocation that gets Pilkey’s books in trouble. A Michigan school (whose motto declares “Preparing Students for the Changing World”) banned the book from its book fair because Harold, one of the series’ protagonists, grows up to be an artist who lives with his domestic partner Billy. Caitlin McCabe at Comic Book Legal Defense Fund noted: “Although it has been reported that most of the school’s parents were in favor of having the book removed from the fair, others have pointed out the absurdity of the action. ‘If you’re in this world, they should know about that regardless. I mean (parents) should have that conversation before it’s brought up,’ retorted parent Kimbery Rose. Just another day in the life of author Pilkey. Pilkey, the odd spelling of whose first name is the result of a typo on the name badge he wore while working as a teenager at a Pizza Hut (even though it is spelled Dav, it is pronounced as if it were spelled Dave) (what? how is Dave with an ‘e’ pronounced any differently than Dav without an ‘e’?)—Pilkey, as I started to say before being destroyed by parentheses, invented Captain Underpants while in second grade. “I got in trouble constantly for making my friends laugh,” he told Nick Mag Aabye at nick.com. “To punish me, my teacher would send me out into the hallway. Before long, I was spending so much time in the hall that my teacher moved a desk out there for me. I had a lot of spare time there, so I began drawing pictures, writing stories and making my own comic books. Quite a few of them were about a superhero named Captain Underpants.” The name of his superhero was inspired by the same second grade teacher. “She used the word underpants during class one day, and everybody laughed,” Pilkey explained. “She got mad and said, ‘Underwear is not funny!’ This only made us laugh harder. At that moment, I discovered that underwear was a powerful thing. It could make my friends laugh, and it could make my teacher very angry.” But the teacher was right: underwear is not funny. Underpants is funny. And Pilkey has made a career out of realizing just that. It’s a career the self-righteous Grand Obstructionist Pachyderm and others of that ilk would just as soon end. But Captain Underpants is not their only target. The most “challenged” book of the past year was The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie. Would-be censors gave ten reasons for its unsuitability, including “anti-family,” “offensive language” and “unsuited for age group.” The last two plus “sexually explicit” are the most popular reasons for challenging books. The “top” banned/challenged book from 2000 to 2009 was the entire Harry Potter series—because of its cast of witches and wizards, supernatural beings who aren’t mentioned in the Bible.

THE MESS IN MESS-O-POTAMIA Off the subject (sort of). If you are as puzzled and frustrated by Bronco Bama’s so-called “strategy” in Syria and the rest of the Middle East, pick up a copy of Time magazine’s double issue, November 30-December 7. In it is a longish article by David Von Drehle which goes further in explaining it all in a cogent, rational, unhysterical nonpartisan manner than I’ve seen anywhere. He describes all of the conflicting cross-purposed plans and goals of various entities in the region, beginning by saying that “ISIS is a particularly difficult problem because it starts with this distressing fact: the forces closest to it aren’t sure they want to solve it.” For Von Drehle, Obama isn’t a flawless leader. He’s made mistakes. And he continues to make mistakes. But his plan, flawed though it may be, might be the best possible way to deal with the pervasive problems. Speaking now as an Obama partisan, I’m glad we have a President who isn’t rushing in half-cocked to do something forceful and spectacular. After reading Von Drehle, I’m thankful that Obama’s strategy is “the antithesis of the ‘shock and awe’ approach to Middle East dysfunction adopted by the previous administration.” End of sermon.

POLITICAL CORRECTNESS STRIKES AGAIN It doesn’t take much to set them off these days. As “political correctness” regenerates itself across the nation’s campuses, college kids (tomorrow’s leaders) have become excessively inhibited about offending anyone. And since almost everyone is capable of being offended by something, we are probably approaching an era of total silence and abstinence. Jerry Seinfeld announced last summer that he won’t accept gigs at college campuses: because of what he calls “that creepy PC thing,” kids can’t take a joke anymore. Chip Rock and Bill Maher have expressed similar reservations. PC has even spread beyond campuses into the current presidential race, the carriers of the epidemic being The Trump and Ben Carson. Trump has lately been attempting to slander Muslims by citing an imaginary instance of whole New Jersey populations of them depicted on tv at the time cheering the 9/11 disaster. Trump persists in this incendiary delusion even when reporters interviewing him tell him it never happened. To ABC’s George Stephanopoulos, Trump resorted to what syndicated columnist Eugene Robinson calls “a familiar dodge,” quoting what Trump said to Stephanopoulos: “I know it might not be politically correct for you to talk about it, but there were people cheering as that building came down.” Carson, Robinson says, is even “fonder of the political-correctness allegation—so much so that it could be considered a central theme of his campaign. It is unclear whether he actually knows or cares wht political correctness means. The phrase is just more verbal romaine to add to the word salad that is Carson’s discourse.” But to return to PC on campus, Bill Maher remarked recently that advocates for political correctness do so because it makes them feel better: it’s a substitute for actually doing something about the alleged offense you mouth off about. Probably more than a modicum of truth in that. But the PC movement is potentially dangerous. S.E. Cupp in NYDailyNews.com agrees that the prohibition against offending aggrieved groups now borders on the tyrannical. Mona Charen in NationalReview.com agrees: the new student radicals are tyrants— “though it is couched in the language of safety, what these little snowflakes want is repression.” At the Atlantic’s September issue, the article was entitled: “The Coddling of the American Mind.” The subhead declared: “In the name of emotional well-being, college students are increasingly demanding protection from words and ideas they don’t like, and seeking punishment of those who give even accidental offense.” Authors Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt elaborate: “A movement is arising, undirected and driven largely by students, to scrub campuses clean of words, ideas, and subjects that might cause discomfort or give offense.” They add ominously: “A campus culture devoted to policing speech and punishing speakers is likely to engender patterns of thought that are surprisingly similar to those long identified by cognitive behavioral therapists as causes of depression and anxiety. The new protectiveness may be teaching students to think pathologically.” In short, politically correct students are driving themselves crazy. Evidence abounds. At the University of California at Berkeley some months ago, students protested against a classical philosophy course because Plato, Aristotle and other Greek philosophers were all white men. At Yale recently, students announced themselves offended that a student affairs professor cautioned them against wearing Hallowe’en costumes that would offend anyone. All witches, for example, would no doubt be offended by witch costumes not to mention green face paint. So the students were offended by being told not to be offensive. How PC is that?

BUT A STUNNING

INSTANCE OF IGNORANCE OVER UNDERSTANDING occurred around Hallowe’en at the Daily

Illini, the student-run campus newspaper at the University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign, when the paper issued an apology letter on October 27 for

publishing a Hallowe’en-themed political cartoon that upset several students on

campus. The cartoon in question depicts three trick-or-treaters on their

rounds, one of them wearing a hoodie and a baseball cap and climbing over a

fence. Syndicated by Cagle Cartoons, Rick McKee’s cartoon pretty clearly plays upon the fear of immigrants that has been ambitiously stoked by Donalt Rump and his ilk mouthing off about it. If, as The Trumpet has loudly proclaimed, immigrants are criminals and rapists, they are to be feared—like witches and hobgoblins— and if a kid wants to frighten people on Hallowe’en with his/her costume, he/she should dress up as an immigrant. McKee’s point, in other words, was a slap in the face of fear-mongers like The Trumpet: it shows how ridiculous, how childish, that fear is. The Daily Illini editorial staff, however, suddenly, after publishing the cartoon, discovered another fear—fear of reader response and student body protest. Some addled students protested McKee’s cartoon, seeing the portrayal as belittling immigrants. The DI promptly reacted with a lengthy letter to its readers—parts of which, including grammatical and syntactical blunders and stumbles, we post herewith—: “The Daily Illini would like to issue its sincerest apologies for the running of this syndicated cartoon. The cartoon was run with frivolous regard, and in no way represents our ideals as an organization, company or the individuals who work for the Daily Illini. … In the future, we will place cartoons for editorial review earlier in the production process to ensure that every inch of our product reflects the mission of our organization.” Then the paper bends over backward to make amends: “The individual who selected the ‘syndicated’ cartoon to be published in the newspaper was suspended from the Daily Illini due to ‘regrets on the oversight.’” Additionally, the editorial staff said, “This choice was made out of carelessness, not out of malice. This student has learned an important lesson about carelessness. “We unfortunately cannot go back and erase it from yesterday’s paper, yet we hope this serves as a wake-up call in our decisions as an editorial staff. We apologize again, and hope that we can earn back the trust and confidence of our readers with each issue of the Daily Illini from here on. “We have reached out to the directors of the Native American House, La Casa Cultura Latina, Bruce D. Nesbitt African American Cultural Center and the Asian American Cultural Center and invited them to come in and talk with the staff about mindfully reporting on issues pertinent to underrepresented communities. “We recognize that a statement can not recognize the hurt that this cartoon may have caused and we apologize for the perpetration of this disgusting stereotype.” I am probably more cartoonist than I am a corrector of political attitudes (no matter that I try harder at the latter than at the former), but I don’t see any disgusting stereotypes in McKee’s cartoon. The stereotypes are the two kids carrying jack-o-lanterns. The kid climbing over the fence is no stereotype at all. If he were a stereotype, he would be wearing clothing that suggests his nation of origin or something similar. But, back to the DI statement, which next, after saying the cartoon had been supplied by Cagle Cartoons, goes on to announce that the has cancelled its contract with the syndicate—in other words, they punished the distributor for the mistake the DI made in publishing the cartoon. (The DI is also five months behind in paying its bill with Cagle Cartoons. Convenient.)

SEVERAL HOURS AFTER The Daily Illini issued its apology statement, according to USA Today’s Walbert Castillo, La Casa Cultural Latina, the Latino/a cultural center at the U. of Illinois, published a statement; to wit—: “The issue is that an artist, a wire service, and newspaper staff all at some point thought that a cartoon denigrating human beings who have sacrificed so much for a better life and for more opportunities could be seen as funny. It is not funny at all. It is offensive, tasteless, and above all, racist. This cartoon depicts not only ignorance but lack of understanding about basic human rights. We have failed somehow to recognize that more than 11 million undocumented people who are in this country have left everything they have — their families, their belongings, their country, their pride in many instances — to find a better life for their family and themselves. … Today, we stand with them, their friends, their families, and their allies to voice our anger and frustration. This is unacceptable, and an apology does not take away the hurt this caused to them and us.” I may be too immersed in the editooning bubble, but I don’t see anyone in the cartoon being “denigrated.” The writers of this statement have chosen the cartoon as a launching pad for their usual tirade on the subject. Fine, they can do that; but none of us should see their statement as an endorsement of the accuracy of the wholly erroneous interpretation already thundering across the U. of I. campus. In fact, McKee’s cartoon is campaigning on the immigrant side of the issue, ridiculing the notion that immigrants are to be feared or imprisoned or shot on sight as The Trumpet would authorize. But La Casa Cultural Latina is scarcely alone in being unable to see the point of the cartoon. Bianca Rodrguez, junior studying biology at the University, told USA Today that the cartoon showcases the ignorance and prejudice toward the sensitive issue of undocumented immigration: “It made me feel like my immigrant heritage is a joke, something to make a Hallowe’en costume out of and share it with the other tens of thousands of students who walk the campus alongside me,” Rodriguez says. “I understand there was an apology issued, and I appreciate the Daily Illini for doing so. But that doesn’t change the fact that someone, somewhere on staff was editing the paper and thought this was okay to post.” Thankfully, not every student shares the same views as Rodriguez. Junior Alex Villanueva, a senator in the Illinois Student Senate, says he believes the Daily Illini should not apologize or punish any staff members for promoting the “free flow of thought, politics, and the advancement of any conversation on key issues of the day. By censoring political cartoons, you are censoring a voice,” he continued. “Political cartoons should be treated the same as editorials. They are meant to induce thought-provoking conversation and a dialogue with meaningful ends. They are designed, often, to be offensive, and this cartoon did that, using offensive tactics to raise the issues of stereotypes, racial or ethnic representations and the national crisis of immigration.” In short, Villanueva recognizes that an editorial cartoon is sometimes intended to be more than funny. Unfortunately, too many people see only the intellectually easy equation: cartoon = funny. And that’s all. The comedy in the best editoonery is supposed to provoke thought, even insight, as well as laughter. Walbert Castillo, by the way, is a former member of the Daily Illini staff and a USA Today web producer.

DARYL CAGLE, owner of Cagle Cartoons and an editorial cartoonist himself, responded: “The Daily Illini cancelled their subscription to the 50-plus cartoonists in our CagleCartoons.com syndication package this week in response to protests against a Rick McKee cartoon that they chose to publish. ... Our cartoon package includes cartoonists with a range of views from conservative to liberal, and it isn’t unusual that we get complaints from editors about cartoons they disagree with. Often the complaints come with threats to unsubscribe if we don’t remove content that the editor doesn’t like. Sometimes we get demands that we ‘fire’ the cartoonists that editors or readers disagree with. “With a wide range of content, we have something new that everyone can disagree with, every day. Since editors receive about a dozen cartoons a day to choose from, they can easily choose cartoons that meet their preconceived world views and they always have cartoon choices available that will not challenge their readers. It is usually the conservative editors who complain about liberal cartoons that offend them. In the case of the Daily Illini, the complaints, and the subscription cancellation, come from the liberal side of the spectrum —which fits the conservative narrative about ‘politically correct’ colleges stifling conservative ideas. “Our experience is that the liberal editors are usually the ones who print left vs. right columns and cartoons, while the conservative editors prefer only to reassure their conservative readers by reinforcing the views their readers already hold. “As a liberal cartoonist who runs a business that includes conservative cartoonists and columnists, [I am fascinated] to see the change in attitudes among editors and readers as both ends of the spectrum become less tolerant and seek to punish those who hold opposing views who offend them. “Rick McKee’s response (in italics) made me smile:” I think it’s a sad day for journalism whenever a newspaper feels it has to apologize for something they knowingly published. But I don’t blame the students. They’re just kids and they’re learning. I blame the politically correct atmosphere they find themselves in that exists on most U.S. college campuses. Our institutions of higher learning are supposed to be safe spaces where differing viewpoints are tolerated, but that no longer seems to be the case. There’s nothing racist about the cartoon and the notion that people should come into this country legally is an opinion that is widely held by many Americans. I’d also like to add that if you hated this cartoon — or if you loved it — my new book is filled with much of the same and can be pre-ordered at a discount right now at mckee.cartoonistbook.com !” Cagle then goes on to quote some of the “interesting comments” he’s received from cartoonists: Jim Engel: “I think every political cartoonist should apologize every day.” Aaron Hill: “Makes me wonder if they published it on purpose to stir up controversy to get out of settling their bill…!” [The Daily Illini is five months behind on their payments for our cartoon package.—Cagle] Gary McCoy: “If you look up ‘gutless-wonder’ in the dictionary, you’ll see a picture of the Daily Illini.” Jim Phillips: “Isn’t that like blaming the grocery store because you didn’t like the new cereal you bought? After you ate the whole box.”

CAGLE ALSO QUOTES Joe Gandelman, who runs The Moderate Voice website, who “wrote a long and interesting response to my column about the Daily Illini dropping CagleCartoons.com over the Rick McKee Illegal Immigrant Trick-or-Treater cartoon.” Here (in italics) are parts of it: I have to add to this. I started The Moderate Voice in December 2003 and it became a group blog by 2004. I’ve written for The Week online and for nearly five years did a syndicated column for Cagle Cartoons. Not a WEEK goes by when I don’t get some emails or facebook messages from someone trying to ban an opposing view or taking great exception to a post or a comment. I know that some will now sic The False Equivilancy Police on me, but the fact is left, center, right are now almost all the same when it comes trying to remove a viewpoint or limit it, in so many areas. ... In the case of Cagle Cartoons, I have a large number of columns and cartoons I can choose from. Many do NOT reflect my view and I run some of them. If I really don’t like one, I can pass on it. And that’s no big deal (some people prefer fish to meat). But so many cartoons are offered from all around the world. Cancelling a service because an editor chose to run a cartoon out of a huge number is puzzling. But not surprising (these days). ... I need to add that I run some other syndicated materials. I CHOOSE what I put up. And if readers were upset over one of the syndicated pieces I CHOOSE to put up from a service, I could let it stand or remove it. But I wouldn’t cancel using the entire syndicate when it had been MY choice to use it or not use it. Bravo. Now that sounds sensible to me. But there is no accounting for the ways that readers misinterpret cartoons. Take, f’instance, editoonist Joel Pett’s encounter with Kentucky’s Governor-elect, who called one of his cartoons “racist”—:

MORE RACIST NONSENSE FROM THE RIGHT Kentucky

Governor-elect Matt Bevin has come out in opposition to resettlement of

Syrian refugees in his state. Like many timorous Americans, he imagines

terrorists lurking in the displaced multitudes. In response, Lexington Herald-Leader editorial cartoonist Joel Pett did a cartoon depicting Bevin as

scared of his own adopted children who are from Ethiopia. With my liberal bias, I see Pett’s cartoon as taking Bevin’s so-called “thinking” to its logical extreme: Bevin is being ridiculed as so fearful of Islamic hooligans infiltrating the ranks of Syrian refugees that he quakes even at photographs of his own adopted children from a Muslim country. (He has nine children, four of whom are adopted.) Bevin chose to respond to the cartoon by accusing Pett of racism: “They say a picture is worth a thousand words,” Bevin wrote. “Indeed, today, the Lexington Herald-Leader chose to articulate with great clarity the deplorably racist ideology of ‘cartoonist’ Joel Pett. Shame on Mr. Pett for his deplorable attack on my children and shame on the editorial controls that approved this overt racism. Let me be crystal clear,” he added, “—the tone of racial intolerance being struck by the Herald-Leader has no place in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and will not be tolerated by our administration.” Jack Brammer at the Herald-Leader said that Bevin did not elaborate about how his administration’s intolerance of the newspaper’s racism might be manifest. I suspect that Bevin’s anger was inspired as much by Pett’s invasion of his children’s privacy in the cartoon as by any political comment inherent in the ridicule—even though Bevin has used his children as political props when running for office. And Bevin is also seizing the opportunity to make a few political points about his administration’s posture on racism while attacking an opponent, Pett. Even if I understand his motivation, I don’t approve of it. In a telephone interview, Pett said he was not a racist. “When Bevin has time to think about it—and there will be recurring criticism of his administration—I think he will view things differently.” He said he would “chalk up Bevin’s reaction to inexperience on his part.” Then the Herald-Leader published Pett’s full response, to wit (in italics)—: “Tasteless.” “Reprehensible.” “A new low.” “I’ll never buy your so-called paper again.” “You owe (whoever) an apology.” I’m sure it will surprise nobody that this kind of mail goes with the territory for political cartoonists. Thanks to all of you who have contacted us, the insults and name-calling notwithstanding. Did I push the envelope by chiding Governor-elect Matt Bevin for jumping on the anti-Syrian refugee bandwagon? Sure, and I did so deliberately. I think he and the rest of the crowd who are demagoguing what happened in Paris for political gain deserve it. Did I attack his children? Of course not. Was the cartoon racist or critical of adopting children, as some are suggesting? The fact that he adopted children from Africa, a continent whose promise and challenges I routinely draw about, is the thing I admire the most about Bevin. I did use the fact that he has children from another country in a piece designed to express outrage over a legitimate hot-button political issue. (Bevin used them in photo-ops and on TV commercials over the past two campaigns, but that’s another story.) I did this with my name signed to it, in a newspaper with a long history of tolerating and publishing opinions of all persuasions and on a page labeled “opinion.” I understand that, for many readers, this cartoon may have been a bridge too far. But here’s an idea: Suppose we just use the means at our disposal here, while we still live in a country where freedoms are cherished, to discuss political issues? Like whether cracking down on Syrian immigration to the U.S. is a proper response to a terror attack in Paris carried out by young people born and raised in France. We can play it straight, or use sarcasm and humor, or irony, whatever. And maybe we could make an attempt, some tiny attempt, to understand other positions, and not poison free debate with a morass of shrieks, hurt feelings and calls for silence. As it happens, I am in our nation’s capital [at the time of writing this], attending a fund-raiser which benefits cartoonists who labor in countries where political cartooning isn’t quite so appreciated, shall we say. Where calls to silence dissent are serious, where people’s reactionary impulse to quiet their perceived enemies has deadly consequences. This is a great job, in a great country, where freedom of speech is celebrated and satire and ridicule have deep roots, upheld at every turn by a broad and thoughtful Constitution and an open-minded court system. Unlike, say, Iran or Syria, where questioning the leadership is met with fury and worse. Thanks for reading the paper. I welcome your feedback. No question, Pett’s letter drips with sarcasm. And sarcasm is sometimes not the best weapon to use in attacking a notion one disagrees with. But Pett wrote it while away from his drawingboard—in a hurry, distracted by other obligations at the moment. Still, it rings with both indignation and common sense.

IRANIAN CARTOONIST IMPRISONED For Producing a Cartoon Sympathetic to Parisians Cartoonist Hadi Heidari was arrested November 16 in Tehran and sent to the notorious Evin prison, his lawyer told Reuters in a telephone interview from Tehran. A prominent Iranian cartoonist, Heidar has been in legal trouble before for expressing unapproved attitudes. “He was convicted two years ago for his cartoons and was sentenced to one year in jail. The authorities had a different interpretation of his cartoons than he had,” said the lawyer, Saleh Nikbakht. Heidari had served about a month of the original sentence, Nikbakht said. According

to Rick Gladstone at nytimes.com (compiling information from several sources),

the Tabnak news site, a Persian-language service in Iran, reported that Heidari

was taken into custody for “unknown reasons” while at work at The Shahrvand,

a daily newspaper in Tehran. It soon developed, however, that the cartoonist

was probably arrested because of the cartoon posted hereabouts that betrayed

sympathy for the secular West. Iranian rights activists, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for protection, said they had learned of Heidari’s arrest from his colleagues at The Shahrvand, who described the arresting agents as members of the intelligence unit of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Gladstone’s report continues in italics. The arrest had not been reported in the official news media as of Monday night. It came after the publication of a cartoon by Heidari depicting tearful solidarity with the people of France over the attacks Friday that left at least 129 people dead [at last report, 130]. The Islamic State has asserted responsibility for the attacks. Heidari, whose drawings are well known, also posted the cartoon on Instagram. Iran’s hard-line conservatives, who control the state news media, police and judiciary, have denounced the Paris killings, and like most of the rest of the world consider the Islamic State a terrorist group. At the same time, they are wary of any perceived expression of friendly overtures to secular Western countries, which they might have thought the cartoon conveyed. Heidari has faced trouble before. He was jailed for a few weeks in 2009, when political turmoil was convulsing Iran over a disputed presidential election, for having participated in a religious ceremony to free political prisoners. He also was summoned for questioning in 2012 for a cartoon that conservative critics said had insulted Iranian soldiers by depicted them as entering the eight-year-long war with Iraq wearing blindfolds. Shargh, a reformist-minded newspaper that published that cartoon, was ordered closed. Heidari’s latest arrest occurred in the midst of a new crackdown, partly inspired by warnings from Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader, against Western infiltration of Iran’s economic, culture and politics in the aftermath of the nuclear agreement signed in July with major foreign powers. A number of Iranian journalists have been arrested in the last few weeks, accused of collaborating with the United States and its allies. Last month, two prominent Iranian poets were sentenced to long prison terms for work deemed to be insulting and subversive. Their punishment included flogging for having once shaken hands with an unrelated member of the opposite sex at a poetry festival in Sweden.

Despite some hostility towards the West in some Muslim countries, many Arab cartoonists responded to the Paris shootings with cartoons expressing a sense of shared grief, reported Carol Hills at pri.org. Here are some of the cartoons.

WOMEN’S BOUTIQUE COMIQUE ComiqueCon, the first ever convention “for women, by women,” packed the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, on November 7, reported Dave Herdon at pressandguide.com. Designed to celebrate women in comics and cartooning, nothing like it had ever been organized, and founder Chelsea Liddy decided it was time for a change. She was tired of seeing “women in comics” as a single panel at shows. “It

was time that we had a space of our own to show off what women are capable of,”

she said. “There are a lot of talented women out there in the field, people

need to know about all of them.” Some of the main stage guests included: Leila Abdelrazaq, graphic artist and author of Baddawi; Nancy Collins, author of Vampirella; Marguerite Dabaie, author of The Hookah Girl; Alex de Campi, author of Smoke/Ashes, Archie vs. Predator, Sensation Comics featuring Wonder Woman and No Mercy; Nicole Georges, author of Calling Dr. Laura and Mikki Kendall, co-author of Swords of Sorrow.

MILE HIGH IS HIGH AGAIN Denver’s Mile High Comics plans on selling its warehouse for a hoped-for $1.6 million, reported the Denver Post. Like a lot of undistinguished-looking old warehouses in the Mile High City, its market value has increased with the growth of the recreational marijuana industry, which, by law, can’t grow its product outdoors and needs the indoor acreage. Owner Chuck Rozanski finds it all hilarious. His business wasn’t christened Mile High Comics just because it’s in Denver, he said. “The whole thing was tongue-in-cheek. I was a massive stoner when I was in college. And here we are 40 years later, and it turns out the pot law spins it all around.” Rozanski started the business in 1969 when he was 13, selling comics out of the basement of his parents’ house. Now he operates three retail stores in the Denver area, plus the warehouse. He’s owned the warehouse since 1986 and can now sell it for triple what he paid to buy it. At present, he and his staff are preparing to move more than 6 million comic books and shelving—around 375 tons, Rozanski estimates—from the 22,000-squarefoot warehouse into the largest of his stores, with 60,000 square feet. To thin the inventory a little, he’s started a fire sale that ought to make collectors happy. And the influx of fresh capital into Mile High Comics will enable Rozanski to resume one of his favorite pastimes—making buying trips, that is, not toking.

THINNING THE RANKS SOME MORE Editoonist Bob Englehart, who has been at the Hartford Courant for nearly 35 years, has announced he’s taken a buyout and his last cartoon ran on Thanksgiving Day. Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist quoted Englehart’s announcement: “The rumors are true. I’m taking the buyout from the Hartford Courant. I’ve read the tea leaves and consulted smarter people than I inside and outside the company. The stars have aligned and it’s time to go. However, I’m not retiring from drawing editorial cartoons, although I will be taking a brief hiatus. My cartoons will resume Monday, January 4 on my website Bobenglehart.com, my syndicate’s website caglecartoons.com, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn. Also, I will continue to draw STUCK, my occasionally recurring comic strip for smart phones, and I will be writing on social media during my short break.”

Here’s a sampling of Englehart. With Englehart’ departure from a full-time staff editoonist position, there remain only 50 in that situation in the U.S.

CHARLIE

FINANCIALLY VIBRANT, SPIRITUALLY EXHAUSTED The tragedy brought the remaining staff members together at first, said Traci Tong at pri.org. There was a real determination to keep going, added Williamson. Nine months in, Tong said, it's a very different picture. Two long-time and high-profile figures at the paper have announced their resignations. One of them, Renald Luzier, is the paper's senior cartoonist (signing himself Luz), who designed the cover response just after the attacks. "Luz has said he won't draw the Prophet Muhammad anymore, because he was no longer inspired by him." Luz left the magazine in late September, saying that “spending sleepless nights summoning the dead” was exhausting. The camaraderie and boisterous mutual sense of mission faded fast in the absence of so many of the satirical conspiracy. Columnist Patrick Pelloux, who has been with Charlie for more than a decade, will leave at the end of the year. “I feel very diminished. Worn out,” he told Nicola Clark at nytimes.com. “The magazine that I knew is finished. I respect those who have the strength to continue, but for me, it is no longer possible.” The malaise includes questions about editorial direction that have arisen and squabbles about what to do with the money. "The idea of who controls that money, who decides how much goes the victim's families, how much goes to the paper," explains Williamson, “— it's a perfect storm." Laurent Sourisseau, the cartoonist who signs his work Riss, now owns 65 percent of the magazine. He survived the January attack but was wounded and contributed to the first post-attack issue from his hospital bed, drawing with his left hand because his right hand was injured. He is drawing with his right hand again and has succeeded his slain cohort Stephane Charbonnier (Charb) as editorial director. He told Clark that the magazine has suffered a double punishment. “When I left the hospital, I thought naively that we would all go back to working together as before. I had no idea that there would be so much chaos.” Some staff members urge that Charlie, which has always been owned by a handful of employees, become officially a nonprofit cooperative. “Other staff members have chosen to leave the magazine, saying that carrying on in the absence of their fallen friends had become too difficult,” reported Clark. After the massacre, Tong said, Charlie Hebdo's staff worked out of the offices at another magazine, Liberation. They've recently moved into new offices, but staff members are still on edge. "They're not free to come and go as they want," Tong quoted Williamson. "Even at home, they never open their curtains. They live in the dark because they’re afraid of becoming targets." For now, Charlie Hebdo will continue, says Williamson, because it's financially secure. But some people feel it's been fundamentally changed. "The old hierarchy, the camaraderie, the old naiveté, the innocence is gone."

DEATH IN THE FUNNIES Two niched cartoon features ended in November. Kit 'N' Carlyle, a popular single-panel comic by Larry Wright, ended November 7. Wright, who created the comic in 1980, announced his retirement and his intent to end the cat-lover's panel, reported indexjournal.com. The cartoon reflected the lives of a single working woman, Kit, and her spunky, mischievous kitten. “Together, the pair has found humor in the daily rhythms of feline/human existence.” Carlyle is more of a cat than the most celebrated cartoon feline, Garfield. Garfield embodies the seeming arrogant indifference of cats toward their owners; Carlyle, while also indifferent, is not at all arrogant. Carlyle is bemused by humans and sometimes does cat things like play with a ball of yarn. Ever see Garfield play with a ball of yarn? Or with anything else? Wright

began his career in editorial cartooning with a civilian daily newspaper while

in the Army, stationed on Okinawa, Japan, in 1961. After returning to the

United States, he began as an editorial/op-ed page cartoonist at the Detroit

News in 1976, where he continued until retiring from the paper in 2009.

Well-recognized for his editorial work, he has been honored with two National

Cartoonists Society awards (1980 and 1984). Fans can access the Kit 'N'

Carlyle archive through GoComics, a comics aggregate website owned by

Universal Uclick, at gocomics.com/kitandcarlyle. The Dinette Set, a single-panel cartoon with a quirky insight into the petty misguided preoccupations that wholly absorb the average consumer-culture driven person, ceased on November 29. Created in 1990 as Suburban Torture by Julie Larson, it was initially intended for distribution to alternative newspapers, but she got it syndicated in 1997, changed the name, and it went national, where it’s been, now, for almost 20 years, reaching a peak circulation of about 70 newspapers. Subscribers had dropped to about 20 papers these days, and Larson, 55, decided she was ready to retire, bringing down the curtain on Burl and Verla Penny, Verla’s sister Joy and her hirsute boyfriend Jerry. Larson, who grew up and lived in the Midwest (chiefly Illinois), gave her readers a good glimpse of the Midwestern mindset — big on buffet restaurants, dollar stores and yard sales. It was satire, of course, but ridicule of a peculiarly sympathetic kind. "She kind of captured consumerism America, not in a finger-pointing way but with a warm embrace of who Midwesterners are as a caricature ... kind of laughing at ourselves," said one of Larson’s daughters, Genevieve Neal, who announced her mother’s retirement. Larson provided laughs not only through the caricatures’ talk, but little extras like a related title on the tv in the background, or Joy's posted to-do list. "Joy will brag about something she has to 'make' for dinner. Usually it's Stouffer's (frozen meals)," Larson said in a 2001 interview. "She has to write 'Lay down and watch tv between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m.' (And) she rinses her bra a lot. There's a lot of things there (on the list) that shouldn't be seen by other eyes." Neal said her mother could make comments on people and society through her comic rather than in person. "All filters are removed, so things she would not ever say in public she can say through the comic," Neal said. "It's definitely her voice, her unfiltered voice, through Burl especially." Despite the inherent ridicule Larson leveled through her caricatures, it’s also clear she was fond of them and their puerile passions. She’s gathering Tortune and Dinette cartoons for a compilation book which she hopes is released next year. Dinette Set fans can also get their fix in the archives at GoComics.com. And if you want to know more about the cartoon and its creator, visit Harv’s Hindsight for January 2010.

ODDS & ADDENDA In Malaysia, the apex court recently upheld the Court of Appeal’s decision to overturn the Home Ministry ban on political cartoonist Zunar’s cartoon books, and told the government to return 33 copies of the books seized, reported the Malaysian Islander. Said Zunar (Zulkiflee Anwar Ulhaque): “This is a victory for all cartoonists, it tells the Home Ministry and the government that drawing cartoons is not a crime.” He told the police to stop raiding his office and said the court ruling should extend to all 16 of his titles. In view of the ruling, Zunar, who is awaiting trial for sedition, also said the authorities should not take action against him under the Sedition Act, nor arrest or detain him for his work. ■ Following its simultaneous 90-country-wide release on Tuesday, November 3, Jeff Kinney’s 10th Wimpy Kid volume, Old School, has sold more than 1,000,000 copies in its first week, publishersweekly.com reported. There are currently 6.8 million copies of the volume in print worldwide. Each book in the series has topped sales charts, with a series total of 164 million copies in print worldwide. ■ Rob Rogers, editoonist at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, won the Berryman Award for Editorial Cartooning given by the National Press Foundation. The prize is named after Clifford K. and James T. Berryman, father and son successor at editorial cartooning for the Washington Star. The judges said: "The winning portfolio included cartoons about police facing cellphone video cameras, the Charlie Hebdo killings in Paris, the campaign between Hillary Rodham Clinton and Bernie Sanders for the Democratic presidential nomination, the stand of Pope Francis on climate change and the proliferation of gun sales in the United States,” adding: “Rogers has a vivid visual style that invites you in. He tackles really heavy issues with a light-handed visual touch. He leaves no confusion about his point of view; he knows what he wants to say.” ■ Brenda Starr, that glamorous and feisty redheaded reporter and her mysterious lover with an eye-patch and a laboratory full of black orchids are making a come-back, saith biffbampop.com. For 70 years, the melodramatic romantic adventures of Brenda Starr, Reporter, Dale Messick’s sometimes frilly fashion adventure strip, captivated comic strip readers. “This time around, America’s favorite comic strip heroine (at its peak, the strip appeared in 250 newspapers and drew 60 million fans) will headline a new mystery novel series created by USA Today bestselling author J.J. Salem. The first title, Black Orchid Murders, is set for publication in Spring 2016.”

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com/comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

T-SHIRT WISDOM Earth without ART is Eh. Go to heaven for the climate; hell for the company.—Mark Twain The truth will set you free, but first, it will piss you off.—Gloria Steinem Whenever there is a huge spill of solar energy, it’s just called a nice day. Over 25% of human genes are the same as those of a banana. Get over yourself. Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy.—Ben Franklin Is it really drinking alone if the dog is home too? Life is short. Dance often.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue.

SEAN MURPHY is back, crowding the pages of his and Rick Remender’s Tokyo Ghost No.1 with intricately rendered action and architecture in post-apocolyptic Los Angeles circa 2089. But the book is not only superlatively drawn: it is also a scathing satire and biting social comment on our present world of technological dependency and trivial pursuit. Calling the Internet “our collective opium den,” Remender explains in a page of text at the end of this issue: The book is “a look at the effect tech has had on modern society and where we are going as a civilization addicted to distraction and entertainment. Think of the social norms smart phones have changed in just six years; when was the last time you had lunch with someone and they didn’t look at their phone in the middle of a conversation? Our impulse control is gone, our attention spans are shorter, and it’s only getting worse. Now multiply exponentially as the decades pass and you have the world of Tokyo Ghost.” The protagonists in this tale of doomed love in a hedonistic fun-seeking extra-digital world where murder and warfare are forms of entertainment and everything is adversarial are Debbie Decay (nee Jacobs) and Led Dent (aka Teddy Dennis), her giant boyfriend, love of her life since their childhood together. Says Remende: “They are constables—‘nano-juiced thugs,’ the ‘only thing between the sheep and the wolves’—for the Flak entertainment conglomerate that rules the putrid squalor of the Isles of Los Angeles. All of society centers on distraction, everyone trying desperately to flee from the harsh reality of the noxious sewer the world has become. Led and Debbie are the law, whatever Flak Corp happens to say the law is that day.” The book opens on Debbie and Led bullying a minion of one Davey Trauma for the location of his boss—spectacular, high-speed flesh-peeling action. Davey is intimately associated with the “body pirating, clone incest, snuff prostitutes, Hong Kong suicide slots, clown torture” of 2089's entertainment world. Then in the issue’s completed episode, they encounter Davey and, after several pages of hot pursuit and crowd-pleasing wholesale mayhem, apprehend and stop him. The book concludes with a salvation fuck as Debbie tries “intimacy” to reach and revive the boy she loves inside the brute of a technocrat man he has become. A deliciously inspired maneuver. Murphy’s

delicate linework creates massive scenes of action and architecture, cluttered,

in the manner of a diasporic future, with tiny details exquisitely rendered, a

display of visual invention beyond imagining. In the second issue, we learn more of Debbie’s dilemma and her plan for escape. She is the only person in the Isles of New Los Angeles who is “tech free.” As such, Remender tells us, “she is the perfect counterpoint to Led, who is a walking distraction. At any given time, he’s engrossed in a dozen different reality shows, and porn clips, a dozen more social network feeds, blood sports, death races, and on and on. He is the natural, exponential end that we are all facing with our phones, the Internet, and the fifteen different blogs we all run. He dials into it all to the point of being unaware of what he’s doing.” Debbie and Led Dent will perform one more assignment as constables, then they’ll disappear into the paradisiac Garden of Tokyo, “the last tech-free nation on earth.” At the opening of No.2, we meet Mister Flak, the master of all he surveys, bathing in a pool surrounded by ministering young women, who eagerly drink his pee-polluted bath water. He and Debbie converse about the world he’s made. “I didn’t create the problem,” he says, “—robotics do the farming, mining, manufacturing, construction—everything. Left an unemployed population with a lot of free time. So I keep them entertained.” To which Debbie says: “You drown them in idiocy, or worse, echo chambers designed to reinforce their misinformed opinions.” (Just a trace of criticism here of our contemporary polarized politics.) “People don’t change their minds anymore,” says Flak. “I didn’t win the ratings war by fighting human nature. People pick a tribe and fall in line. So I gave them each their own channel, told them what they wanted to hear—I make them comfortable. When human life became worthless, I gave it value. Every show watched is a purchase. Those purchases move industry and create jobs. Consumption gives human life meaning.” (More of our current Biblical chapter and verse. Uncanny how that happens, eh?) Flak ignores a previous agreement that will free Debbie and Led after their encounter with Davey Trauma. Instead, he sends them on one more assignment, and if they successfully compete it, then they’ll be free. He sends them to Tokyo to kill the warlord whose plan threatens Flak’s world and his rule thereof. Debbie, seething with resentment at their being betrayed by Flak’s reneging on their previous agreement, vows that they’ll never return from Tokyo’s paradise. We last see Led in pursuit of a mysterious figure—and Debbie, unconscious on the ground with the mysterious figure, whence she arrived by pursuing Led. The issue brims with more exquisite art from Murphy.

I’ll be back for more (and I’ll be hoping for even more of Murphy’s splendid art).

THE FIRST ISSUE of Warren Ellis’ James Bond 007 series, “Vargr,” reads like a James Bond movie. And that’s appropriate to its promotional purpose, arriving in comic book shops just as the new Bond movie opens. The comic book begins with a 10-page silent sequence that depicts a bearded man fleeing from something. By the fifth page, the “something” is another man, who engages the bearded man in a life-and-death struggle. On the ninth page, we learn that the pursuer, who is so far victorious in the struggle with the bearded man, is “007.” On the tenth page, he kills the bearded man. On the next two pages, we go to a squalid apartment in Brixton in London and see a couple apparently taking drugs, surrounded by other people who’ve either o’d or dropped off to a happy happy land. Then we see a bloody-handed guitar player in an unmade bed who says something we can’t understand. That’s all of that. Next, we’re at the headquarters of MI6 and James Bond is arriving and flirting with Miss Moneypenny before going in to see M, who, in three pages of nearly motionless pictures, gives Bond his assignment: go to Berlin and dissuade a small-time drug dealer from expanding his business to England. The issue concludes with a page introducing an emotionless Mr. Masters, probably a synthetic professional assassin, who is assigned the job of killing Bond. As a first issue, this installment has all the requisite elements of a good example. The opening sequence, one of several complete episodes, shows Bond to be a ruthless and dedicated agent; at MI6 headquarters, he displays his penchant for womanizing, his sense of duty with M, and his weakness for a well-tailored wardrobe. And the last page leaves us dangling on the edge of a cliff, fully aware that a lethal danger lurks in Bond’s future. In a jolting surrender to political correctness, both Moneypenny and M display an African racial heritage. In Moneypenny, that’s believable; in M, not—not in the customary hierarchies of British life. Jason

Master’s drawings are adequate but not particularly distinguished. Like

many artists drafted into drawing comics these days, he draws well enough but

can barely render his characters recognizable from one page to the next. Bond

has a scar on his right cheek, which helps in this regard, but not much.

Master’s style is pristine, and his depiction of Bond’s meeting with M is so

visually sterile that it’s boring. Directed, no doubt, by Ellis, Masters gives

the sequence a modest pictorial interest by having Bond fidget in his chair. On

other pages—layouts again probably directed by Ellis—Masters gives us

meaningless close-ups of weapons or establishing shots with focal points at

such a distance that superfluous close-ups are distractions. And the layered

anatomy of a naked Mr. Masters is a visual joke. The opening wordless sequence, however, is well-done. The panels present instants of the action rather than links in a continuous chain of motion, an episodic treatment that works pretty well. Guy Major’s colors are a little dark, though, which makes finding telling details difficult. I’ll be back but not for more Master-work: it’s Ellis, whose twisted but well-crafted plotting and invention appeals.

IN SHARP CONTRAST

to the Bond book, we have first issues of Call of Duty: Black Ops III and Joe Golem: Occult Detective, both comic book versions of forthcoming

flicks. Call of Duty is very nearly an instruction booklet on how not to

do a first issue. Marcelo Ferreira’s drawings do not clearly identify

the characters, who, to compound the mess, all look too much alike whenever

they’re close enough for us to make out their features; too much of the

time,they’re tiny figures in the distance. And his page layouts, aiming to convey

the feeling of ratchetting-up action, are, as a result, jumbled and confused.

But the central problem is Larry Hama’s story, set in some

post-apocalyptic world. Full of snappy patter and technical black ops argot, neither speech balloons nor captions convey with sufficient clarity what the action is all about. It took me a second reading (for a comic book?) to realize that the operatives, the good guys, are looking for somebody named Timur Abulavey, who they are supposed to find and waste. Much of the first half of the book is devoted to the operatives’ search for enough weaponry to fulfill their mission. Here’s a sample of the kind of talk they engage in: “I only need a few boxes of jacketed hollow-points and AP for the locus sniper rifle, three boxes belted for the LMG, maybe fifty mags for the KN-44's, and a few boxes of 9mm subsonic.” Their leader, Jacob Hendricks, doesn’t show up until halfway through the book. But all along the way, violence bubbles continually, foes are shot, stabbed, dismembered (maybe not this last; hard to remember, the slaughter being so relentless). One of the operatives is killed in Abulavey’s lair, but since we haven’t gotten to know him very well, his death doesn’t have much impact on us. There’s more along these lines, but it’s too much for me. Too much blood, too many killings, too much confusing lingo and upside-down layouts. Hama thinks he’s writing a movie, but comic books achieve story clarity by means different than movies, and he seemingly doesn’t know that. Joe Golem, on the other hand, is better but still requires a second reading to sort out the different elements of converging plot lines. We begin in the canals of lower Manhattan in the office or apartment of a detective, Simon Church, who reads to us out of his diary, but it’s all mysterious allusion to things we know nothing of. And there seems to be some sort of clay creature lurking in the darkness. A golem? Had to say: it’s pretty dark on these pages. Next, we see three boys commit a petty crime, snatching a woman’s purse, but as they gloat over their fortune while making a getaway in an outboard motor boat, a monster arises from the water and carries off one of the boys. Then we meet a slumbering man, who, we later determine, is having a nightmare about a golem, a nightmare that goes on for four pages before the sleeper awakens. He’s asleep in Church’s study/apartment, apparently Church’s assistant; he does Church’s legwork. In this role, Joe Golem, for this is he, goes to visit the orphanage where the three boys live, and when he persuades the two who remain to take him where the other boy went missing, the monster shows up again, and takes one of the two boys into the water with him. Joe Golem sheds his jacket and jumps in after them. End. Even counting Joe Golem’s visit to the orphanage as a completed episode, we still don’t know much. And that’s the problem: Mike Mignola and Christopher Golden, dwelling on the mysteriousness, haven’t given us enough to whet our appetites. Church’s opening soliloquy is too cryptic. The boys’ connection to Church isn’t clear; perhaps they have no connection. Joe’s nightmare seems to allude to the medieval mythological golem, but we aren’t told for sure. Only after Joe awakens does the plot seem to hold together and start to make sense. But it’s too fragmented.

As I said, once Joe Golem gets on the scene, the story begins to make sense. But there’s a lot of mysteriousness to wade through before we get there.

THE FIRST ISSUE of Archie Comics’ revived Jughead concentrates on food. I suppose that’s okay: it’s familiar ground with Jug, but I hope they come with some other identity formula for the long haul. In this issue, Riverdale gets a new principal who revises the menu in the cafeteria, replacing Jughead’s comfort food with healthy stuff. Jughead, smitten to the core, faints and dreams himself back into the Middle Ages for a “Game of Jones” in which hamburgers somehow play a role. Jughead and Archie find a dragon who gives them the seed for innumerable burgers, so they win. I’m not sure, exactly, what they’ve won. But it doesn’t matter because Jughead wakes up and learns how to make hamburgers so he can sell them in the cafeteria, thus defeating the new principal’s scheme. Or something like that. The book also includes a “classic Jughead” story from the old Jughead No.1 of 1949. It makes more sense. The

confused story is by Chip Zdarsky. Erica Henderson handles the art in

the rejuvenated title, but while she produces a suitably simple linear drawing

and captures Jughead’s visual essence, the other characters aren’t quite up to

the same snuff. Archie barely looks like the Archie of that title; ditto Betty,

who seems to have gained a few pounds since the Dan DeCarlo days.

Henderson’s treatment of the mouths of characters is distinctive but wrong.

This is not a successful revival. Before we leave the realm of the Archies, let’s take a quick look at the third (and final) Fiona Staples version of the flagship title. As usual, exquisitely drawn—somewhat simple but with a more complex line than the classic Bob Montana/Dan DeCarlo manner. In Mark Waid’s story, Archie encounters Veronica for the first extended time following their disastrous meeting in No.2 at the scene of the collapse of the Lodge manse—precipitated, so to speak, by Archie’s chronic clumsiness. Archie is smitten and a slave to “Ronnie” immediately. And she, a thoroughly self-aggrandizing snooty snob, tries out her beckoning and calling at every opportunity. And Archie swoons and grovels appropriately. Fortunately for our sense of justice, Veronica, whose snootiness extends to a preference for fancy food, eats of the school cafeteria fare and promptly hurls, getting a healthy sample on her designer dress. Betty, witnessing all this and fuming at the way the besotted Archie is behaving, decides to join Jughead in bringing Archie back to reality, and the next issue (drawn by the new artist, Annie Wu) promises to revisit the “lipstick incident” that resulted in Betty shunning poor Arch since No.1 of the reincarnated title. For the sake of ancient history, this issue concludes with another vintage Archie tale done in the Bob Montana manner (by Bob Montana)—the alleged first appearance of Veronica from Pep Comics No.26 in 1942. Archie makes a fool of himself here, too, but not in quite the obsequious way he adopts in the newest version of their first encounter.

I DON’T KNOW

WHO, Mills or Burchett, drew Gravedigger No.3, “The

Scavengers,” but whoever did, did an eye-treat job. The entire issue is in

black-and-white with gray tones, heavily shadowed but crisp and clear. Elegant.

And the other achievement is in rendering the starring anti-hero, “Digger,” to

look like actor Lee Marvin. Easy enough in full painted color on the

cover, but requiring great skill during the inside pages. But Mills or Burchett

manages it with panache. The story is a predictable tale of betrayal and betrayal, with Digger offing most of the traitors in the last pages. Will there be a No.4? Were there Nos.1 and 2? Who knows. But this issue is a delight. After typing the foregoing paragraphs, I found Nos.1 and 2 of the title, offering a two-part story called “The Predators” —more betrayal, sexy wimmin, and acts of violence. And in No.1, Christopher Mills concludes with an editorial that traces the history of the title and identifies Rick Burchett as the artistic one of the pair who gave visual life to his conception. In No.2, Mills wonders if they didn’t make a mistake using Marvin as a model for Digger “because every time I red a Facebook or Twitter post that reads ‘Hey, it looks just like Lee Marvin!’ as if we didn’t know that.” Mills admits he gave Burchett a nudge when, in describing Digger to him, he said he should be hard but not superhuman, tough but distinctive ... “perhaps a little offbeat looking ‘like Lee Marvin or someone like that’ and Rick obliged.” They tried to create a character that Marvin would have played, Mills says. And his regret is only momentary: “Now I can’t imagine Digger looking any other way.” And neither can I. Expertly done, kimo sabes. Oh—looks like there will indeed be a No.4.

JASON AARON and penciler Chris Bachalo and a legion of inkers must be having a great time. Their revival of Dr. Strange is both strange and wonderful. Highly ornate but crisp artwork, and the story and art betray the creators’ jolly agenda: they’re not quite serious about Strange’s various dilemmas. I’m up to No.2, and it’s evident that they are treating his mystic maneuverings with just the right tongue-in-cheek touch. Dunno how Stan Lee and Steve Ditko felt about the good Doctor—and I never read their work, creating the character—but I suspect they weren’t altogether serious about the title either. I don’t suppose that Garth Ennis is altogether serious with his new All Star Section Eight either, but his tale is much less entertaining than Aaron’s in Dr. Strange. Ennis’s story is a hodge-podge of antic hysteria pitting an absurdly supposedly comic band of would-be superheroes against—what, exactly? The whole point of whatever passes for “story” here seems to be to gross us out. The characters are physically repulsive and the action, ditto. The big attraction for me, as I thumbed copies on the newsstand, was John McCrea’s juicy art. I was so smitten that I bought the first two issues. Unfortunately, McCrea was required to render grossness in the extreme, and not even his energetic renderings with bold feathering, appealing though it is, could overwhelm the nastiness of Ennis’ storyline. Too bad. I might keep these for the artwork but I won’t go on to buy Ennis’ No.3 “Section

Eight,” by the way (and perhaps entirely irrelevant), used to be the part of

military law or regulation in the old compulsory service era that provided a

reason for discharging a person before his enlistment was up: Section Eight

described habitual behavior that was physically or psychologically

inappropriate for a serviceman/woman. And it surely applies to this book. The first issue of Sam Humphries’ Citizen Jack introduces us to Jack Northworthy, who sells snowblowers in a northern clime, but when the new mayor installs snow-removal equipment for the city, Jack is out of business. Nothing daunted, Jack attempts to regain his monopoly by threatening snow-removal truck drivers with a pistol. Bloated and sloppy, he spends most of this issue wandering around in a terrycloth bathrobe, drinking Jack Daniels from the bottle. Having been mayor of the town once before during the corrupt regime (his) that insured his snow-removal monopoly with blowers, he decides to re-enter politics, launching his campaign by jumping through a hole in the ice into an icy lake to demonstrate that he had the “stones” for a campaign, then emerging nude and shouting: “It’s time for America to get jacked!” Yes, he’s running for President of the U.S.A. In the issue’s second completed episode, Jack is approached by an attractive young woman, Donna Forsyth, who has been sent by a foundation to run his campaign. She presents irresistible arguments, but Jack, probably half in the tank, hesitates. She leaves her contract with him should he decide to sign. After which, adding suspense to suspense, we see a red-eyed monster glowering over Jack. So it’s a monster book. It would be good election-year entertainment except, for me, there are two disqualifiers. First, that supernatural being lurking in the shadows here; I don’t go much for intergalactic spook stories. Second, artist Tommy Patterson’s artwork is sprayed too much with fine fragments of his fineline technique, imparting to some of the drawings a hesitant appearance. And as many of those reading this probably realize by now, I dislike any art that betrays a lack of confidence. But this quirk of mine is, as you must all realize, a personal quirk, not an objective aesthetic fact. You have your quirks, too. And you’re welcome to them; just don’t try to defend them in an objective factoid manner. Despite my quirk, I might buy the next couple issues just to see how Humphries handles it: can he produce satire in a supernatural ambiance?

Quotes and Mots “If you don’t stick to your values when they’re being tested, they’re not values: they’re hobbies.”—Jon Steward “Most of the time, I feel entirely unqualified to be a parent. I call these times being awake.”—Comedian Jim Gaffigan “Life starts out with everyone clapping when you take a poo and goes downhill from there.”—Essayist Sloan Crosley College football coaches now rank above governors as the highest-paid public employees.—Gilbert M. Gaul in his book, Billion-Dollar Ball: A Journey through the Big-Money Culture of College Football

PEANUTS GALORE And the Movie

I DROVE A HALF-AN-HOUR into nearby Brighton to see “The Peanuts Movie” yesterday. It’s been out a week, and in box office receipts, it’s second to the new James Bond movie. Not bad. (Even though the new Bond movie, “Spectre,” didn’t do as well as its immediate predecessor in the series, “Skyfall”: 8-day totals, $105,500,181 vs $132,089,864 for “Skyfall.” The 8-day total for “Peanuts” is merely $63,899,181. Scarcely a blockbuster by this measure, but, as I said, not bad.) I’d

seen samples of the “Peanuts” visuals, so the film’s appearance was no great