|

|||||||||||||||

Opus 340 (May 30, 2015). With this hoppy posting, our 340th, we finish the 16th year of Rancid Raves. That’s right: we’ve been doing this for sixteen years. HOOrah! That probably makes us one of the longest-running websites on comics. In fact, if we add a few qualifiers—we are definitely the longest-running website of comics news and reviews, cartooning history and lore being operated by two cartoonists. Amazing what a few qualifiers can do for one’s ego. And the other cartoonist, our webmaster, Jeremy Lambros, and I are on the cusp of adding a new feature to the enterprise—about which, more when we get closer. In the meantime, we celebrate this anniversary with an opus that rambles conversationally from one topic to another as we think of them. The longest ramble takes us through the thicket of issues prompted by Garry Trudeau’s reaction to the Charlie Hebdo murders—whether freedom of expression should be limited by ordinary politeness to reduce or eliminate offensiveness. Cartoonists reaction to Trudeau’s remarks had barely died down when PEN revived the foofaraw by planning to give Charlie Hebdo an award for courage that some PEN members objected to, saying it would “valorize” offensive cartooning. Isn’t satire inherently offensive—to someone? What, then, of the future of satire? And before the award could be given, a Muslim hate group’s Draw Muhammad cartoon contest was attacked by Cutthroat CalipHATE hooligans of the home-grown sort, who were killed in their attempt. Engaging as such a discussion on the nature of cartooning and free expression is, that’s not all we offer in Opus 340. In fact, it’s a whopper of a posting. We encourage you to scan the list of topics and articles that comes next in order to pick those that interest you—rather than trying the impossible, reading the whole enchilada at one sitting. So here’s what’s here, in order by department—:

NOUS R US Summer Super Flicks Archie Kickstarts then Kickstops Denver Comic-Con Passes 100,000 Maus Banned in Moscow

Anniversaries—: Fantasia Tom and Jerry Born Loser

EDITOONERY Roundup of the Month’s Crop

THE QUESTION OF OFFENSIVENESS PERSISTS Trudeau’s Punching Up and Down Charlie’s Hate Speech Dozens of Cartoonists Describe Their “Red Lines” Charlie’s Luz Quits Cartoonists Draw Their “Red Lines” Trudeau’s Response on “Meet the Press”

THE HYPOCRISIES OF PEN Members Oppose Giving Charlie an Award for Courage 200 Sign a Petition Others Protest the Protesters Charlie Hebdo Jabs at PEN The Myopia of the Writing Class Art Spiegelman Musters the Opposition Alison Bechdel, Neil Gaiman, Gene Luen Yang, Jules Feiffer

ANTI-MUSLIM GROUP SPONSORS MUHAMMAD CARTOON CONTEST Two Cutthroat CalipHATE Hooligans Killed at Cartoon Exhibit Sponsor’s Pamela Geller Triumphant Cartoonists React in Cartoons

PEN’s Courage Award Given Spiegelman Comments on the Role of Cartoons

What I Think About Hate Speech and Offensive Cartoons

PAT BAGLEY REDUX How Editooning Fares in LDS Country

AAEC Condemns Shootings at Contest Exhibit Pamela Geller Marches On with Ads for Buses in D.C. Iran Runs Anti-Isis Cartoon Contest

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL A Selection of Comic Strips that Amaze and Amuse

BOOK MARQUEE Goodbye God? by Hunt Emerson Weird Al’s Mad

BOOK REVIEWS The Mythology of S. Clay Wilson, Vol. 1 Howard Chaykin’s Black Kiss XXXmas in July

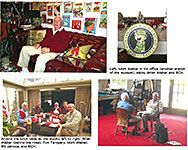

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Unusual Mutt and Jeff (not by Bud Fisher) Caricatures by Milton Caniff RCH Interviews Mort Walker, Brian Walker, and Jules Feiffer

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE The Big Con Job Tales from the Con Daredevil Resists Donning TV’s Duds Red One by Terry and Rachel Dodson

PEN Letters Quoted in Full

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

THE SUMMER’S OFFERINGS of superhero flicks got off to a spectacular start April 30-May 1 with the opening of “Avengers: Age of Ultron,” which pulled in $84.5 million, besting the $80.8 million debut of the first Avengers film in 2012, according to Disney estimates, which predict the “Ultron” movie will eventually beat the first Avengers’ all-time record of $207.4 million. The summer’s supers schedule resumed on May 15 with “Mad Max: Fury Road,” to be followed by “Jurassic World” (June 12), “Disney/Pixar’s Inside Out” (June 19), “Terminator: Genisys” (July 1), “Ant-Man” (July 17), and “Fantastic Four” (August 7).

ARCHIE KICKSTARTS THEN KICKSTOPS Riding the crest of a wave of fan enthusiasm about the forthcoming revamped Archie, the first issue of which is due in July, Archie Comics decided to catapult that popularity into revamps of other characters, scheduling three new titles: a new Kevin Keller-starring series from Dan Parent and J. Bone (Life With Kevin), a new Jughead-oriented series with Chip Zdarsky writing and an artist to be named later (Jughead), and a Betty and Veronica-oriented series by the creator Adam Hughes (Betty and Veronica). Co-publisher Jon Goldwater wanted to get the new books onto the newsstands fast in order to hitch onto the success of the new Archie, written by Mark Waid and drawn in an entirely different style by Fiona Staples. Goldwater, who has overseen other revamps and new directions in his company in the last few years, was eager to continue to get attention “for the company and our creators, to celebrate our 75th anniversary and to really jazz our audience.” But Archie Comics had just signed a deal to supply Wal-Mart and Target with digest titles, and that project sucked up financial resources. So to fund the new titles, Goldwater launched a Kickstarter campaign. “Normally, we could put these books out over time,” Goldwater explained to Tom Spurgeon at comicsreporter.com. “We'd just have to sprinkle them out over a few years, as opposed to fast-tracking them. The Kickstarter allows us to build on the expected success of Archie No.1 in a more meaningful way while also offering some cool rewards for our fans who choose to back the Kickstarter. ... The idea is to make them happen faster because we know fans want them faster.” Makes sense to me. And Goldwater is bubbling over with excitement and hype. The plan was to raise $350,000. The rewards for donors to Kickstarter consist, it seems, mostly of copies of the new titles when they come out. Maybe a few sweeteners, too. It all seemed a grand way to celebrate Archie’s 75th anniversary. Problem was: crowdfunding is usually launched by entrepreneurs “in need,” not major publishing houses like Archie Comics. Goldwater assured Spurgeon that the company was not in financial difficulty. He just wanted the new books out fast in order to feed and foster the kind of fan interest that the new Archie has stimulated. Goldwater said over and over again, his company was a bold, innovating company, and resorting to Kickstarter was just more evidence of the “new Archie”—the Archie Comics that had married Archie to both Betty and Veronica, then killed the redhead, introduced the first openly gay character, and launched a zombie title in Afterlife with Archie. Bold. Try anything once. But as soon as the Kickstarter program started, Archie Comics was assaulted with questions and concerns from fans and retailers. The company has only just begun to get into comic book shops, and the shop owners wondered about how the Kickstarted titles would feed into their system. It looked as if they’d be cut out of the equation as the publisher began distributing titles directly to readership via the Kickstarter rewards system. And there were other concerns, on all hands. At first, Archie responded by revamping and expanding the rewards. But that didn’t quell the concerns. Finally, it was too much. Archie Comics cancelled its Kickstarter. The decision to pull the Kickstarter, Goldwater told comicbookresources.com, came after the Internet conversation was no longer about the books themselves. Instead of talk about the new titles and writers and artists, social media brimmed with criticism of crowdfunding products by a major publishser. "Once that happened,” Goldwater said, “we decided it was time to stop. While we don’t mind putting ourselves under the microscope or answering questions, the creators involved didn’t deserve that level of negative attention. Though we fully expected to get funded, we felt it was time to step back." The new books will still be published, said Goldwater. “It’ll just take a beat, and we won't be able to create this movement or wave of comics over the next year and change.” Jughead No.1, for instance, was originally scheduled for September, and has now moved back at least a month. "Very broadly, Jughead will come first, sooner than you'd think," Goldwater told CBR News. "Probably October. Then we'll take a pause, figure out the rollout of the other two and how to best position them in the market. It's going to take longer than we'd hoped, obviously, but these titles are top priority for us, and we want to make sure our fans get the best books possible." Meanwhile, the company will thank the donors who jumped on board with a special thank-you gift.

DENVER COMIC-CON GETS ANOTHER BIG NUMBER It was a heppy heppy weekend (May 23-25) at the Denver Comic-Con, which, according to BleedingCool.com, broke the 100,000 attendance mark, the number that had been anticipated due to enthusiastic advance registrations. The official announcement, made by DCC factotum Jason Jansky, pegged the final number at 101,500 (up from last year's 86,500, which, in turn, topped the previous year's attendance). In a mere four years, DCC is within striking distance of unseating the record-holder, the San Diego Con. BleedingCool also reported that the programming was “the most extensive” he/she’d ever seen—and 400 tables in Artists Alley (which is dubbed “Artists Valley” here due to the proximity of the mountains). Like most comic-cons in recent years that are not devoted to movies and tv shows, the DCC is part “craft show” (the artists in Artists Valley sell jewelry and t-shirts, buttons and bows, not just drawings of comic book characters) and part “costume parade.” But the DCC is determinedly a family show and has aggressively discouraged costumes that show too much skin. Still, the real world has started invading cosplay. For the first time I realized it, I saw several alleged men dressed as women. Transgender is on the moves, kimo sabe.

MAUS BANNED IN MOSCOW “Art Spiegelman's Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, Maus, has some very memorable cover art,” said Robert Siegel at npr.org: “It pictures a pair of mice — representing Jews — huddling beneath a cat-like caricature of Adolf Hitler. Behind the feline Hitler is a large swastika. That last element has become a problem for Maus this spring. For Russian observances of Victory Day, the holiday commemorating the Soviet Union's defeat of Nazi Germany, Moscow has purged itself of swastikas. In an effort to comply, Russian bookstores cleared copies of Maus from their shelves.” Asked what he thought of this development, Spiegelman replied: “I think it's rather well-intentioned stupidity on many levels. I'm afraid that this is a harbinger of the new arbitrariness of rules in Russia. And the result will be like what happened in the obscenity rulings that closed down a lot of theater plays. It's arbitrary rulings that make playwrights and theater owners afraid to put anything on that has an obscenity in it. ... Be very careful if you're writing about anything else we decide is the red line this week. So this is a way in which I fear that Maus has been instrumentalized to ends I don't approve of.” This isn’t the first time Maus’s swastika cover has caused trouble, Spiegelman said. When the book was offered to a German publisher—“way back when Maus was not a known entity”—the publisher cited a German law against displaying the swastika on the covers of books. But the publisher found a loophole: the government can make an exception for “works of sserious scholarly import.” Siegel wanted to know just how important the cover can be. Said he: “As we all know, you can't judge a book by its cover.” So what’s the big deal? To which Spiegelman said: “Well, the whole point of what we're calling graphic novels is the melding of visual and verbal information—to sound professorial for a second. And part of that information starts with the first thing you see.” He recalled that Pantheon didn’t want to give him the right to do the cover back 1986 when the first volume was published. “I was sputtering,” Spiegelman continued. “How can you do that? The cover's part of the book, of course. And then my friend up at Pantheon, Louise Fili, the superstar art director of Pantheon at the time, said shut up and don't worry about it. You'll do the cover. It goes through me. So I did. I got a separate paycheck on top of the relatively small advance. And when the second book came out, they insisted that I do the cover so I don't get any extra money,” he finished with a laugh. But in Moscow, you didn’t see Maus covers for a while.

ODDS & ADDENDA Animated cartoons on prime-time tv rank as the longest-running sitcoms: “Family Guy” racked up 250 episodes recently, saith Time, and “The Simpsons,” with 574 (and a two-year renewal in hand) will easily pass 600. The nearest competitor is the vintage 1950s live-action “Ozzie and Harriet” with 435 episodes; “Cheers” lasted for 11 seasons but achieved only 275 episodes. ■

Scholastic has lately secured a grant from the Herb Block Foundation to start

an editorial cartooning category in the Scholastic Awards. ... In 2013, a

musical adaptation of Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel, Fun Home, was

mounted at the Public Theater in New York with book and lyrics by Lisa Kron and

music by Jeanine Tesori. In March 2015, “Fun Home” moved to Circle in the

Square Theatre and opened to rave reviews on April 19th.

ANNIVERSARIES Disney’s much acclaimed attempt at turning animated cartoons into film artistry, “Fantasia,” is 75 this year. According to John Wenzel at the Denver Post, “The 1940 film, which interprets eight different pieces of classical music through lush, hand-drawn animation, arrived as flagship character Mickey Mouse was slumping in popularity.” The inspirational heart of “Fantasia” was, then, “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” segment in which Mickey stars: this would, it was hoped, revive the character’s standing among fans, who’d been slowly won over to Donald Duck since the quacker’s first appearance in “The Wise Little Hen” in 1934. The eight-part “Fantasia” grew out of Mickey’s appearance. But the “Fantasia” we see today is not the “Fantasia” of 1940. It has been modified, tweaked, and changed here and there as it aged. Says Wenzel: “For esxample, early versions of the segment for Beethoven’s ‘Pastoral Symphony’ featured black centaurettes polishing the hooves of white centaurs. These scenes were removed in the late 1960s for fear of perpetuating racist stereotypes.”

MGM’S TOM AND JERRY are 75 this year, too. The first of the duo’s 163 adventures on the screen arrived February 10, 1940. Entitled “Puss Gets the Boot,” the debut cartoon features Tom and Jerry but Tom is called “Jasper” and Jerry has no name. (He was called “Jinx” around the studio, but the name isn’t used in the final film.) No one attached any special significance to the one-shot cartoon until, later that year, it was nominated for an Academy Award for Short Subjects, Cartoons. Producer Fred Quimby promptly pulled creators William Hanna and Joseph Barbera off other projects and put them to work making more Tom and Jerry cartoons. The Tom and Jerry cartoons have been de-racistized in later years: the only human in the series was “Mammy Two Shoes,” a heavy-set African American maid. Although her face is never shown (we see only her chubby body below the neck—and, of course, her shoes), by accent and the color of her hands and harms, she’s clearly identified as black. Because the mammy stereotype is now regarded as racist, her appearances in the televised cartoons have been edited out—or she has been re-animated as a slender white woman. Saith St. Wikipedia: “She was restored in the DVD releases of the cartoons, with an introduction by Whoopi Goldberg explaining the importance of African Americn representation in cartoon series, however stereotyped.”

ART SAMSON’s Born Loser is 50 this month, having debuted May 10, 1965. Since Art’s death in 1991, his son Chip has been running the misadventures of Brutus Thornapple, the hapless loser of the title.

Herewith, the Sunday anniversary strip and a daily (May 6) from the run-up week. The anniversary is being celebrated and Universal/Uclick’s website, GoComics.com, where you can enter a contest to win a “high quality” print of the strip if you’re one of the lucky contestants. You can also print out a “Born Loser” certificate, which has a blank spot for you to insert your name. Or you can print out the one that accompanies this announcement. Here’s Chip’s account of his career as his father’s successor—: “My career as a cartoonist began in 1977. My dad, Art Sansom, created The Born Loser in 1965 and by 1977, he was looking for an assistant so he could ease up his heavy workload, especially with the gag writing. I had started a career in the business world immediately after I graduated from college four years earlier, and by this time I had become disenchanted with that career path and was looking for something more creative. Sounds like a perfect match, right? Except I never dreamed I could be a cartoonist, because I believed I was a terrible artist. I think I was intimidated by the fact that both my mother and father were fabulous artists. There was no way I could live up to the high bar they had set, so I decided at an early age not to try. This is not to say they did anything to make me feel this way: it was all in my head. “Believe it or not, I never took an art class in college, high school or even junior high school. In retrospect, I think if I had taken art classes, I probably wouldn’t have been all that bad and certainly would have learned many things that I would find helpful to this day. On the other hand, I was an English major in college and had loved creative writing from an early age, so I was confident I could help my dad out with the writing on the strip. I started by submitting a series of gags to him, as had multiple other professional writers. They were all talented, but they didn’t know The Born Loser like I did. I grew up watching my dad create the strip in his studio in our home. I knew it so well, my gags worked better for the strip than those of the other writers. “Dad offered to hire me as an apprentice and teach me the art side of things while I was writing gags for him. I accepted under the condition that I work for free on a trial basis for one year, while still working my other job. I passed the audition to the satisfaction of both of us and started my official apprenticeship one year later. “Dad taught me every aspect of producing the comic strip exactly as he did. The artwork progressed slowly but surely. I found that even though I was unable to quickly draw the characters, my eye was trained to know what they should look like and I would keep working on my drawings until they passed my eye test. By the time Dad passed away in 1991, I was able to take over the complete production of The Born Loser by myself. I still felt I wasn’t a great artist, but I believed I could produce The Born Loser better than any other living person. I have made a conscious effort to continue the comic strip in the style Dad taught me. As a tribute to him, I still sign both of our names to every strip.” Chip said that “at a very young age,” he was a fan of Dennis the Menace. Maybe that accounts for Hurrican Hattie, the juvenile terror of The Born Loser. Chip was never into comic book superheroes, but when he discovered Carl Barks, everything else took a back seat.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS “I don’t judge people based on color, race, religion, sexuality, gender, ability or size. I base my judgement on whether or not they’re an asshole.”—A. Nonymous “The rich are not the job creators. The job creators are the vast middle class and everyone aspiring to join them, whose money businesses need in order to justify expanding and hiring.”—Ex-Secretary of Labor, Robert Reich “If Obama came forward with a cure for cancer, they [the everlasting GOP] would oppose it.” —Joseph Cirincion in The Washington Spectator

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy STACKED UP WITH BOOK REVIEWS last time, we skipped over this department in order to finish a posting within readable range. I’m not sure, upon reflection, that we accomplished the latter goal, but we’re back with Editoonery again this time anyhow. Surprisingly, we’ve missed little in terms of developments worthy of the editoonist’s pen. Jon Stewart says that he’s quitting “The Daily Show” because, among other things, of boredom with American politics. Every day, it’s the same old shit. And as I look back over the crop of editoons from the last two months, I see a lot of familiar events: the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm is still hypocritically attacking Obama over and over again for doing exactly what the GOP would do were it in the White House, the House has voted—pointlessly, again, for the 59th time?—to repeal Obamacare; otherwise Congress does nothing, “failing to govern” (in the favorite GOP phrase) in all directions at once; racism continues to roil in American streets, the Cutthroat CalipHATE persists, with cartoonists still the targets. The only thing that changes is the contortions the Prez must perform in order to execute the laws he’s obliged to execute. Despite

a certain sameness, editorial cartoonists persist in exploring the resources of

their visual medium to expose pettifoggery and other kinds of political

mummery. Next around the clock, Jeff Danziger gives us a hysterically comical image of “Israeli Leadership,” ludicrously leading the way to suicide—as if the only way to combat terrorism is to blow oneself up by “lousing up” the Iran deal. Immediately below, Matt Davies manages to ridicule both Netanyahu and the GOP in a single image. Bibi, revealed on the eve of the Israeli election as motivated only by crass political self-interest, stakes his future on the supposed support of the American GOP-controlled Congress, which, in a single comment, reveals itself to be as naive about Middle Eastern politics as Bibi is about American politics. Who is being “played” is a good question. At the lower left, Pat Bagley gives GOP’s pecksniffering hypocrisy the spotlight it deserves. The cartoon is more verbal than it is a blend of word and picture, but the pictured “mess” gives the words their ironic satirical edge. Galumphing

GOP folly is Joe Heller’s subject, opening our next exhibit at the upper

left. As for Hillary’s supposed criminality in dodging government e-mail mechanisms, she joins a number of GOP presidential aspirants in the practice: Chris Christie, Marco Rubio, Scott Walker, and Jeb Bush (not to mention former Secretaries of State Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice) who have all admitted trying to avoid government oversight by conducting business through private e-mail accounts. As Will Durst put it: “It’s become such a boring predictable dance, Lady Gaga will probably write a song about it soon.” But it’s Jeff Danziger’s imagery for the infamous letter to the mullahs that best captures, for me, the nature of the “crime”: the 47 senators who signed the letter did not, exactly, commit treason (although there are enough of the political opposition who say they did to make the charge seem momentarily credible), but they did usher in a new era of American foreign policy-making, one that is about as guaranteed of success as wading off into the ocean is both uncertain and unproductive. There’s a reason that the writers of the Constitution left foreign policy to the Prez: he speaks with one voice, while the Senate, in this instance, speaks with 47 of the 100 possible voices. Below Danziger, Nick Anderson provides an apt visual metaphor for how the Iran deal is being viewed from two American perspectives: for Obama, it’s the happy ending of an Easter-egg hunt; for Congress, it’s just another meal, waiting to be fried out of existence. Finally, Tom Toles at the lower left reveals—as if it needed revealing—the GOP policy with respect to the Prez. But this time, the irony—mostly verbal—reverberates across both domestic and foreign affairs. Next

up, images of the Congress. Chan Lowe shifts to another subject—the emerging U.S.-Cuba relationship—at the lower right with his imagery of American tourists invading the island nation. And at the lower left, Bennett is back with one of his potent images, this time vividly showing us where the “path to citizenship” goes. The

fate of the GOP, its plans and other obscene behaviors, is the topic in our

next display. Next, Clay Bennett invokes a standard cultural image of horror to remind us of just how the Republicons’ bid for minority support must look to the minorities whose lives the GOP policies affect. And below, Chan Lowe’s metaphor of a hairy, big-footed cave man suggests how primitive (and therefore transparent and crass) the GOP’s attempt to garner women’s votes is. Finally, we have Tom Toles, who, in four panels, presents the ludicrousness of the GOP lie about Obamacare. It’s a circular argument that goes nowhere, but, laughably enough, the Republicons behave as if they don’t see the illogic in their repeated lies. Iconoclastic comedian Bill Maher, interviewed in the May issue of Playboy, calls these effusions “zombie lies—lies that live forever even though they’re not true. They’re the undead of politics. I noticed Iowa Republican senator Joni Ernst referring to the Keystone jobs program in the Republican response to Barack Obama’s State of the Union address this year. Okay, we’ve proved for a couple of years now that the Keystone jobs program would create only 35 jobs. As one senator said, you’d create more jobs by opening a single McDonald’s. Trickle-down economics is another zombie lie: give the rich tax breaks and the poor will thrive. Sam Brownback, the governor of Kansas, destroyed his state’s entire economy selling that zombie.” Meanwhile,

the 2016 Presidential Campaign has already begun. (In fact, if you had your

head about you, you would have noticed that it began the day after the results

of the 2012 election were announced. No wonder Stewart is bored.) Tom Toles’ opening shot at the upper left of our next visual aid depends upon an

actual fact: the dome of the capital building is being renovated. Clay Bennett takes a look at Jeb Bush’s incipient campaign and anticipates the difficulty he’ll have in courting the Tea Baggers in the GOP (who look like the disease Jeb doubtless thinks they are). And then Ted Rall fires off a broadside, finding Jeb’s religious faith shallow to the point of nonexistent. Religion

is the topic in Jeff Danziger’s shocking orange cartoon that opens the

next exhibit. During his Playboy interview, Maher was asked about the Presidential campaign. “The real question mark,” he said, “is what the Repupblicans will run on because they can’t run on jobs; unemployment is too low. I suspect we’ll see the batshit campaign tactics we saw with the last few Bush runs: John McCain had a black baby; Willie Horton came out of nowhere; John Kerry went somehow from a war hero to a despicable coward in that insane turnaround. It’s going to be some made-up issue that the Republicans will harp on. Remember Jeb Bush’s father running in 1988? We had these rumors about Kitty Dukakis burning the American flag and all that shit about Michael Dukakis not cleaning up Boston Harbor. If things are still going well, we’ll have some pictures of Hillary scratching her ass at Mount Rushmore in 1975. That’s all the Republicans can run on at this point.” The fate of gay marriage is next under fire on the exhibit at hand. Chris Britt offers one of his patented hysterical panicky bigots to chastise the anti-gay crowd. David Horsey asks the question no one is asking. Would a baker forced to bake a cake for a gay couple poison the batter first? Finally, Chip Bok ponders a Supreme Court that refuses to bake the cake for a gay wedding. I’m not sure the metaphor translates into a cohesive comment but that is doubtless because of my pro-gay marriage bias. The justices seem to be adopting the attitude of bakers who refuse to bake wedding cakes for same-sex couples. What’s the answer to the question Chief Justice Roberts poses? What will happen? Nothing? What? The Court’s decision will supply the answer. Still, where is Bok on the issue? By turning the proposition on its head in this fashion, Bok seems to be making a case against forcing the populace to accept same-sex marriage. In other words, he’s against gay marriage. That anyone intelligent enough to be a editorial cartoonist could hold that opinion these days seems outlandish, and so I have trouble translating Bok’s cartoon into a statement. But maybe he’s just having a little fun, poking both sides in the eye with a stick of imponderability. In any event, Bok’s caricatures alone are worth the posting. Baltimore

is the subject of the next display. And then Lisa Benson lands on the one bright spot in the Baltimore brouhaha—the single mother of six, Toya Graham, who chased her son out of the protesting mob and back home, where, she alleged, he belongs. At least there, he’d stay out of trouble. "I was pretty much just telling him, 'How dare you do this,'" Graham said. When she first saw the video of herself, she thought, "'Oh my god, my pastor is going to have a fit.' That's it." At the end of the day, she told cbsnews.com, her intention was to bring her son to safety. She said when she saw her only son with a rock in his hand, she just lost it. “He has been in trouble before, and he knows right from wrong. He's just like the other teenagers that don't have the perfect relationship with the police officers in Baltimore City, but you will not be throwing rocks and stones at police officers," Graham said. "At some point, who's to say that they don't have to come and protect me from something, you know? ... Two wrongs don't make a right, and at the end of the day I just wanted to make sure I had gotten my son home." Graham represents the power in most African American communities where fathers are hard to find. In attempting to solve the so-called “problem” of the fatherless black family, we have undoubtedly been looking in the wrong place: we keep trying to re-engage black men, fathers; we should be looking for ways to enhance the power of the existing power structure, the mothers. Almost immediately, numerous of the saintly population jumped all over Graham for physically abusing her son. Sigh. Finally, in a bitter recognition of a reality we seem to be living with, Humor Times, leading up to its 25th anniversary, reprinted the Joel Pett cartoon it published on the front page of its first issue, April 1991. As we see, the problem of police brutality has been with us for a long time. Humor Times is a monthly newspaper printing chiefly editorial cartoons, plus a couple of columns (by Will Durst and Jim Hightower). You can get a sample copy through its website, humortimes.com, for a buck (shipping and handling charge); a year’s subscription is $24.95 for 12 issues of the print paper; $9.95 for a downloadable digital version. I recommend it, either way. Next,

a little untrammeled recreation—three cartoons by Flash Rosenberg, who

muses on everyday preoccupations in the most fanciful visuals. And

then we have a few cartoons by Patrick Chappatte, whose international

perspective gives his observations a detachment that is often bitting. Turning

next to other current issues, we come first upon Keith Tucker’s panels

about the impending Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement, aimed at

facilitating and improving trade and, hence, national revenues. Unhappily, most of the information on TPP is based upon leaked documents or fragmentary statements on matters still being negotiated; nothing is final, so it’s impossible to say whether Tucker is being reasonable or alarmist. The best alternative is Elizabeth Warren’s: let’s open up the talks and discuss it all. Negotiators resist transparency at this stage because the secrecy permits hesitant countries to confront issues that would otherwise drive them away from the table. Immediately below Tucker are two Prickly City strips by Scott Stantis, generally a conservative editoonist who grinds his axe in the strip by deploying in the desert two charming seemingly innocent characters, a little homeless girl named Carmen and her coyote buddy Winslow. Lately a pink-eared bunny rabbit has invaded the premises, and, judging from its (her?) comments here, the long-eared character is a stand-in for Hillary. Stantis’ sarcasm coupled to funny pictures is enough to amuse even me, flaming liberal that I doubtless am. Back to the top right of the visual aid, we get to cartoonists’ reactions to the most recent terrorism, this time, in the U.S. “homeland.” As usual, inspired by cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, a brace of AK-47 toting adherents of the Cutthroat CalipHATE attacked an helpless exhibit of Muhammad drawings in Texas, a suburb of Dallas. More about this incident ’way down below. Here, Ted Rall kicks off with a few snide remarks prompted by Garry Trudeau’s comment last month that the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists wandered into hate speech (quoted at some length below). Rall has turned Trudeau’s notion into raw comedy (“Marked for a Pulitzer or Marked for Death?” “Death? Or slow death?”) by depicting an imaginary “Jihadi Art Critics Circle.” Below Rall, Jimmy Margulies assumes an imaginary Muslim attitude to explain the prohibition against depicting the Prophet: Muhammad is too embarrassed by the antics of the Cutthroat CalipHATE to show his face. With that, we conclude our sermon on editorial cartooning this time—and leap, forthwith, into the latest Charlie controversies—:

Trudeau’s Charlie, PEN’s Charlie, and Geller’s Charlie THE QUESTION OF OFFENSIVENESS ABOUNDS WE HAD THOUGHT, until a few days ago, that the monstrous Charlie Hebdo issue had slipped into a forgotten past, like most matters that are urgent only as long as they sell newspapers or enhance tv viewership. But Doonesbury’s Garry Trudeau, prompted by the need to say something in accepting the George Polk Career Award (see Opus 339) in early April, said things about Charlie that created no little stir in cartooning circles. We have posted the entire speech at Opus 339, but here below we repeat those of his remarks that caused the stir (all in italics): Traditionally, satire has comforted the afflicted while afflicting the comfortable. Satire punches up, against authority of all kinds, the little guy against the powerful. Great French satirists like Molière and Daumier always punched up, holding up the self-satisfied and hypocritical to ridicule. Ridiculing the non-privileged is almost never funny—it’s just mean. By punching downward, by attacking a powerless, disenfranchised minority with crude, vulgar drawings closer to graffiti than cartoons, Charlie wandered into the realm of hate speech, which in France is only illegal if it directly incites violence. Well, voila—the 7 million copies [of the magazine] that were published following the killings [of Charlie staff] did exactly that, triggering violent protests across the Muslim world, including one in Niger, in which ten people died. Meanwhile, the French government kept busy rounding up and arresting over 100 Muslims who had foolishly used their freedom of speech to express their support of the attacks. The White House took a lot of hits for not sending a high-level representative to the pro-Charlie solidarity march, but that oversight is now starting to look smart. The French tradition of free expression is too full of contradictions to fully embrace. Even Charlie Hebdo once fired a writer for not retracting an anti-Semitic column. Apparently he crossed some red line that was in place for one minority but not another. [France has a law prohibiting anti-semiticism.] What free speech absolutists have failed to acknowledge is that because one has the right to offend a group does not mean that one must. Or that that group gives up the right to be outraged. They’re allowed to feel pain. Freedom should always be discussed within the context of responsibility. At some point free expression absolutism becomes childish and unserious. It becomes its own kind of fanaticism. I’m aware that I make these observations from a special position, one of safety. In America, no one goes into cartooning for the adrenaline. As Jon Stewart said in the aftermath of the killings, comedy in a free society shouldn’t take courage. Writing satire is a privilege I’ve never taken lightly. And I’m still trying to get it right. Doonesbury remains a work in progress, an imperfect chronicle of human imperfection. It is work, though, that only exists because of the remarkable license that commentators enjoy in this country. That license has been stretched beyond recognition in the digital age. It’s not easy figuring out where the red line is for satire anymore. But it’s always worth asking this question: Is anyone, anyone at all, laughing? If not, maybe you crossed it.

WHAT TRUDEAU CLEARLY BELIEVED was a humane and thoughtful re-consideration of the Charlie cartoons—by American standards, unusually gross and vulgar in flinging their satiric barbs—suddenly looked as if he were blaming the victims: the Charlie cartoonists brought on their own murders by drawing those outrageously offensive cartoons. Cartoonists

immediately took sides. Some supported Trudeau; others did not. Rueben

Bolling was among the latter in his Tom the Dancing Bug. So why would I draw this cartoon, attacking the position on Charlie Hebdo he presented in his speech accepting the George Polk Award? Well, I'm fascinated with the issue, and when his speech was released, I found that I disagreed with him in a way I thought was interesting. Of course, when America's most prominent cartoon satirist provocatively weighs in on a huge global story about the most important tragedy in cartooning satire history, I'd say it's worthy of our attention. I wrote a few tweets about his speech. And then, as I thought about it, I came up with this comic, using the example of America's abortion debate to show that it's not always clear whether a satirist is punching up or down, or why that should matter. In Charlie Hebdo's case, poking fun at religious authority, and violent religious fundamentalists, could certainly be seen as punching up. Anyway, once I had the comic sort-of written, I felt it would be dishonorable or even cowardly to scuttle it because I didn't want to anger Garry Trudeau, or because I wanted to be sure to be in his good graces. We're satirists, and we should be able to disagree with each other through our chosen medium (which doesn't lend itself to nuance or equivocation). Also, to be honest, once I have a comic I like in mind, it's very hard for me to shift gears and change subjects. As I try to write another comic, my mind will keep wandering back. I'm like a dog with a chew toy; I can't let it go. ... Well, I will email Garry and explain that while I disagree with him, I do so respectfully, but I suspect he won't be happy about this comic. And that genuinely bothers me. But I guess if I can write satire about newsmakers whom I don't know and respect, it's only fair that I don't back away from writing satire about newsmakers whom I do. Here's

the original opening panel, showing Trudeau's stand-in Mike Doonesbury making

the speech. I decided I needed to give the reader more background with a fuller

explanatory panel (one of the weaknesses of this comic), so I substituted in

the B.D. / Zonker panel. Editorial

cartoonist Ann Telnaes is another who disagrees with the notion of

“red-lining” editorial cartoons. At a presentation at the Library of Congress

on April 30 (reported by Sukrana Uddin at Young DC.org), Telnaes said that

limiting oneself according to other individuals’ “red line” of comfort would

eventually box in a cartoonist’s free speech and creativity. Reported Uddin:

“Adhering to stern censorship rules stifles a cartoonist’s job of provoking

thought and conversations. Rules would eventually restrict true free speech.

She had produced a cartoon as long ago as 2006 that vividly illustrates the

dangers of red-lining.” Too many red lines make that box we’re trying to avoid. Telnaes co-presenter, Signe Wilkinson (who, like Telnaes, is a Pulitzer-winning editoonist), agreed: “Each group has something sacred. The question is whether we can let each group decide for everyone else what is sacred. And if we do, we will not be drawing [editorial] cartoons.”

OTHER CARTOONISTS responded to a ComicsRiff survey conducted on April 27 by Michael Cavna, who wanted to know if any of them hold any potential targets as truly, personally taboo. Said Cavna: “In other words: If editorial cartoonists are surgeons of satire, is there anything that is off their operating table? When they cut so incisively, are there any ‘red lines’ each of them prefers not to cross? Here is how 15 of America’s leading cartoonists responded”—: Nick Anderson (Houston Chronicle): I don’t think in terms of red lines; I tend to think in terms of context, which requires judgment. What is over the line in one context might not be over the line in another. If I’m drawing a really outrageous cartoon, it is probably because I’m trying to employ a fitting metaphor for a situation that I find particularly outrageous. That being said, I can’t say I’ve ever felt the need to attack or belittle the founder of a religion — Jesus Christ, Muhammad, etc.. I prefer to attack and belittle their followers, who often willfully misinterpret the words of the founders for their own twisted ends. I agree with Trudeau that “because one has the right to offend a group does not mean that one must.” And this does not mean that criticizing the Charlie Hebdo cartoons puts one in league with the Charlie Hebdo murderers. One should be able to cross the line in a free society without fear of violent reprisal. The answer to speech that crosses the line is more speech. Pat Bagley (Salt Lake Tribune): I’ve cartooned for decades in a state that comes as close to a theocracy as any in the United States of America. Garry Trudeau said in [his] speech that “the French tradition of free expression is too full of contradictions to fully embrace” — suggesting it was impossible to grasp and there should be a role for censorship. The Mormon tradition of “freedom” and “choice” suffers from the same contradiction. When I went to BYU in the ’70s, the running joke was that the university motto was “Free Choice; and How to Enforce It.” I thank whatever Enlightenment thinker — probably French — came up with the idea of free speech, now enshrined in our U.S. Constitution. Otherwise the 90-percent Mormon, white, privileged male Utah legislature would be tempted to dictate my choices.

(RCH: Okay, Bagley doesn’t seem to be addressing the question. Does he have any personal red lines? I interviewed him years ago, and I’m posting some pertinent parts at the end of this segment under the heading “Pat Bagley Redux.” The short answer—well, there is no short answer. See for yourself down the scroll.)

Nate Beeler (Columbus Dispatch): Personally, I generally think it’s unwise to publicly set “red lines” for what you won’t draw. Every controversial cartoon idea needs to be judged on merit within its context, and that’s both a personal and editorial decision on whether to go forward. Each cartoonist must decide what type of reputation he or she wants to cultivate. I agree with much of Trudeau’s speech, particularly with the notion that “because one has the right to offend a group does not mean that one must.” But I take serious issue with Trudeau giving rhetorical cover to terrorists who murdered his cartooning compatriots. … People everywhere have the inherent right to freely express themselves in “childish” and “unserious” ways — which is lucky for Garry Trudeau. … I can tell you that you’ll never see me draw a cartoon about Garry Trudeau being savagely beheaded by free-speech absolutists. Darrin Bell (Washington Post Writers Group): I won’t blame religion for anything in my cartoons. Fanatics are fair game. People who cherry-pick from their religion in order to justify the denial of equal rights to others are fair game. People who use religion as an excuse for tribal fighting and slaughter are fair game. Holier-than-thou hypocrites are fair game. But so far I’ve never depicted an entire religion as being fundamentally flawed. I don’t draw that line because I think religions are above reproach; I draw that line because I feel blaming religion itself lets the bigots, the hypocrites and the ignoramuses off the hook. Religion is a tool. Some use it to build discriminatory laws. Others use it to build civil-rights movements. I’d rather focus on the carpenter than on the tool.

(RCH: Incidentally, if you haven’t noticed, Bell is back doing editorial cartoons, the work he did while in college. He does three a week for WPWG, plus writing and drawing two 7-day comic strips in syndication, Rudy Park and Candorville. Glutton for punishment. He also has an 18-month-old son. And he just won the Robert F. Kennedy Award for editorial cartooning. Obviously, he never sleeps. )

Matt Bors (Medium’s The Nib; Universal Uclick): Obviously, I think satirists should punch up and not down when choosing targets, including scolding dead cartoonists. I use my best judgment and try not to gauge what I do based on the most easily offended or quick-to-murder reader. Steve Breen (Union-Tribune, San Diego): I thought that what Garry Trudeau said was right on. It seems to me, from what I have read, that the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists were pushed by their editor to cross red lines…to become, as Trudeau put it, fanatics for free speech. It seems to me a good editor pushes us [cartoonists] to be as accurate, clever, clear and concise as possible. He or she should help you affect people but not intentionally enrage them. When people are enraged, they hate you — and when they hate you, they’re no longer able to be objective when they consider your point of view. I don’t operate in terms of specific red lines, but I do rely on the filters in my head, as well as the guidance of my editor to look at something and say: “Whoa, this might be a red zone we should steer away from — why not try making the same point in a powerful but less-inflammatory way?” Mike Luckovich (Atlanta Journal Constitution): Great question. I view my mission differently than the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo. I don’t set out to provoke. My goal is to get my point across. If it upsets one group or another, so be it. I’m nominally Catholic. During the pedophilia scandals, I hit the church repeatedly and was criticized for it. However, my red line is never drawing a cartoon mocking Jesus Christ or any other religious icon to make a point about a particular faith. I won’t negatively caricature Muhammad to slam Islamic radicalism. Jimmy Margulies (King Features): The question of which topics or issue I would shy away from in my editorial cartoons is somewhat difficult to answer. Personally, I try to distinguish between things which people have no control over or choice in — such as nationality, race, ethnicity, disability — and those which they do have a conscious role in, such as thoughts, beliefs, actions, policies, etc. The former in my opinion are not fair game, but the latter are. I say that the question is somewhat difficult to answer because in reality, the red lines are not set by cartoonists themselves, but by an editor who decides what is suitable for publication. Whether an editorial cartoonist is employed by a newspaper or draws for syndication, it is always the decision of the editor what gets published. So the question of what a cartoonist may decide is acceptable makes for a very stimulating discussion. Ultimately it becomes an academic exercise, since the cartoonist does not have the final say. When I was employed at the Record in New Jersey, my editor would not permit cartoons which ridiculed Governor [Chris] Christie for his weight. I never proposed any that targeted him for his weight alone — they were always in conjunction with something else for which I was criticizing him. But the mere suggestion of poking fun at his size was always an obstacle to getting approval. Jack Ohman (Sacramento Bee): I think any cartoonists who work on daily newspapers stay within what are commonly accepted parameters. Offhand, I wouldn’t say there were subjects I wouldn’t or can’t comment on. I do try not to be derogatory about a person’s religion. I will comment on a religion if I disagree with a position the leadership of that religion has taken. While cartooning is extremely reductionist, there are taste boundaries, and those boundaries are stretched constantly. One example for me was Governor Jerry Brown’s use of the word “fart,” in describing Governor Rick Perry. That was the first time I went in that particular direction. Joel Pett (Lexington Herald-Leader): Where to draw the line when drawing lines?…Okay, I personally, would never draw anything that might get large numbers of people killed. This also applies to “maimed” and “imprisoned for life at the mercy of Dick Cheney.” … Unless, of course, I could select the individuals from the ranks of corporate and government evildoers past and present against whom I harbor grievance. I would also never criticize a cartoonist of Garry Trudeau’s stature, whom I respect for many reasons. Major red line! I would graciously, but not obsequiously, concur with some of his major points, like “punching up” and that writing satire in a free society is a privilege, one that comes with attendant responsibility. I would downplay the holes in his speech, giving him the benefit of the doubt, assuming that something was lost in translation, or lack of inflection or facial expression or the like. Examples of these would be: 1) that “free speech absolutists…denounced using judgment and common sense”; and 2) the usefulness of his conclusion about “whether anyone at all is laughing.” Never one to nitpick, I’d just smile and internalize my thoughts about how “absolutists” merely defend the right of people to say dumb things, and that some idiots will laugh at almost anything. Also, small point, but the lines aren’t red at all, and in fact they have more shades of grey than “insert S&M joke.” I might mention that all of the highly publicized battles over free speech involve parties acting irresponsibly, or at least doing and saying things that most of us wouldn’t dream of. Like publishing Hustler, donning swastikas and marching in Jewish communities, picketing military funerals with signs reading, “God hates f—“, drawing the prophet for a nonprofit, or simply being Rush Limbaugh. Please do not translate this into any other language, hand-letter onto a scroll or chisel into a tablet, as something may get lost over the centuries, causing untold misunderstanding. Thank you. Rob Rogers (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette): I consider myself a free-speech absolutist in the sense that I don’t believe anyone should be murdered or even jailed for expressing themselves. I don’t think any kind of speech, no matter how offensive or “taboo,” should result in a death sentence. Once we begin to allow certain people or groups to dictate what is okay to say or draw, it is only a matter of time until those exceptions become more and more restrictive. It is a slippery slope to ultimate suppression. By criticizing the content of the Charlie Hebdo cartoons, and there is certainly plenty to criticize, we run the risk of blaming the victim. If only they hadn’t drawn the prophet Muhammad. ... If only the rape victim hadn’t worn that short skirt. … These kind of arguments only embolden the attackers and those who think their actions were justified. Also, while I would never draw the kind of shocking images found in Charlie Hebdo, I think it is also a big leap to say that by depicting Muhammad in an unflattering way, those cartoonists were attacking a powerless disenfranchised minority of Muslims. I read it as them attacking a religious taboo, not a group of people. My own personal moral code is certainly one of not punching downward. My goal is to create satire that champions justice and equality, and I try to avoid images that may undermine that purpose. I believe in going after the oppressors, not the oppressed. I attack the hypocritical and corrupt, the rich and powerful, the cruel and pompous rulers—not their poor followers. While I don’t think I have any red lines, per se, because I would never want to put those kinds of restrictions on my creativity, I probably do have some pink lines. I avoid images that could be seen as racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, etc., because they would be antithetical to my intended message. In 2014, I was called anti-Semitic for a cartoon I drew about Gaza that criticized Israel’s use of military force in the region. My particular cartoon style includes large, bulbous noses on all my characters. I don’t think my depiction was anti-Semitic, but in the future, I will be more sensitive when drawing cartoons about Israel. Jen Sorensen (Fusion and Austin Chronicle, et al.): I’ve been asked this question a lot over the past year, and I’d suggest that the phrase “red lines I won’t cross” is somewhat flawed. People crave absolutes, but there are no lines — only specific contexts and circumstances. Also, the phrase seems to imply that I’m repressing something I *should* be saying. I’ve often said that being a political cartoonist is like being a doctor; I try to heed the golden rule of “do no harm.” Will my work contribute to hatred and misunderstanding? Or does it serve to illuminate and defend the less-powerful in society? The only subject I won’t draw about is one about which I have no good cartoon ideas. Rather than follow lines, I follow my conscience. And in the U.S., I’m fortunate to have tremendous freedom to do that. I may be in the minority among my colleagues, but I greatly admired Garry Trudeau’s speech on Charlie Hebdo. Garry gets it. There are ways to criticize terrorism and religious extremism without humiliating and alienating an entire people at the bottom of the power structure. Scott Stantis (Chicago Tribune): [I have] no hard and fast “red lines.” Like the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on pornography: I’ll know it when I see it. I would also ask Garry [Trudeau] or any others defending the pretext of the Charlie Hebdo attack exactly what “punching down” the people at the kosher deli, where the attackers went next, were guilty of?… [Trudeau’s] point seemed to be that the satirist’s first obligation must be to sensitivity and not to moral outrage. Apparently, one of the Charlie Hebdo covers that really set off the attackers ridiculed radical Islam, going as far as renaming the publication Sharia Hebdo. If that’s “punching down” then more satirists ought to do it. I am also aghast at his sneering label of “free-speech absolutists.” Count me as one of those as well. Signe Wilkinson (Philly.com; Philadelphia Daily News): Different people have different lines, which is why no ONE person should be able to declare crossing a particular line to be a death-penalty offense. Personally, I work for two newspapers with general-interest audiences with wide tastes. I don’t do nudity, profanity or graphic violence. My line on religion is that when a religious group starts asking for special favors from the state — whether it’s tax privileges for their schools or exemptions from regulations everyone else must abide by — or acting in ways that affect others — abusing kids, cutting off apostates’ heads — they become part of the political process, and should be treated as the political players they are. As much as I respect Garry Trudeau, I disagree with his argument on Charlie Hebdo. Like Trudeau, I wouldn’t have drawn most of the cartoons they published, and didn’t follow their publication. However, their cartoons did not kill people. Humorless religious fanatics did. It is the assassins we should be worried about, not a bunch of cartoonists whose work was largely being ignored by non-terrorists. Adam Zyglis (Buffalo News; this year’s Pulitzer winner): As Trudeau mentioned in his speech, I, too, believe my role as a cartoonist is to “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” My goal is to express an opinion to my readers in a way that’s honest about what I believe to be right and wrong. If in the process I provoke anger or vitriol, then so be it. But to needlessly provoke is to reduce what I do to public shouting. I suppose that’s my red line: Do not be gratuitously offensive. I don’t have any topics that are off the table in my commentary. I let my editors do the editing, and I’m lucky that in my case, I’m given free rein in terms of message. With imagery, my paper used to be sensitive to depictions of the Pope and the Catholic Church [in light of the abuse scandals], but I still found ways to make my point. Free speech has its limits, and producing work for a mainstream newspaper means certain images will needlessly provoke. Religious symbols, such as the cross or a depiction of Muhammad, need to be handled with care when crafting cartoons. It doesn’t mean they’re off the table — it just means you must use them responsibly. The same is true for racially charged imagery. The cartoons of mine that have been the most controversial have been ones immediately following a tragedy. For instance, after a Buffalo plane crash in 2009, I was highly critical of the poorly trained pilot and the sub-par safety standards of the regional airline industry. The cartoons were circulated around the airline industry to many who weren’t regular consumers of satire. The reaction was overwhelming — so many people were offended because they didn’t know cartoons aren’t always like Garfield. But since then, I’m more cognizant of the timing of my cartoons.

WRITING AT HIS BLOG, Daryl Cagle, editoonist and owner of his syndicage, Cagle Cartoons, expounded even more, starting with his observations about Charlie cartoonist Rénald “Luz” Luzier, who drew for the first post-killings issue of Charlie Hebdo the now-famous cover caricature of Muhammad with a tear running down his face, saying“Tout est pardonné,” or “All is forgiven.” Luz decided at the end of April that he would no longer draw Muhammad cartoons. “He no longer interests me,” Luzier told French magazine Les Inrockuptibles. “I am tired of him, just like [former French President Nicolas] Sarkozy. I am not going to spend my life drawing them.” To which news Cagle responded (in italics): I can sympathize with Luz’s choice: since he’s now “typecast” as the premier Muhammad cartoonist, it seems reasonable that Luz wouldn’t want his career to be boiled down to being the “Muhammad cartoon guy.” I’m an editorial cartoonist; I haven’t drawn a Muhammad cartoon myself, because I haven’t been inspired to do so. I shy away from drawing cartoons that some people would find offensive. I don’t use four letter words, or the “N-word” in my cartoons. I don’t draw sexually explicit cartoons. Offensive subject matter in cartoons can be so loud that it drowns out anything else I might want to say in a cartoon, except, “Look, I have the freedom to draw something offensive.” Many cartoonists have drawn Muhammad cartoons, and racist cartoons, and dirty cartoons; that’s fine, that’s their business—but drawing offensive stuff just to draw attention to myself, or to prove that I have the right to do so, just looks like lousy cartooning to me. The Charlie Hebdo cartoonists were doing more than that; they were addressing issues in French culture that were important to them, and rejecting all religions that they felt didn’t fit with their secular society. I knew three of the five Charlie Hebdo cartoonists who were murdered earlier this year and I got to know more of them at French cartoon festivals. They have a genuine passion for their issues and our conversations always turned to a discussion of their religion-bashing cartoons. Here in America we’re not faced with the same social pressures and similar cartoons here should seem out of place. It

doesn’t matter that I personally don’t choose to draw Muhammad cartoons, or

that most cartoonists don’t care to draw offensive cartoons, all editorial

cartoonists are now being seen as recklessly poking surly Islamic beasts. My

profession is being painted with the Muhammad cartoon broad-brush. I was recently asked to speak at a local college, and I met the college president; the first thing he said to me was, “Now, don’t show any of those Muhammad cartoons.” This is not unusual. Casual conversations with editorial cartoonists often start with, “So, do you draw those Muhammad cartoons too?” Like Luz was typecast, it seems we’re all typecast now.

A MONTH AFTER GIVING UP drawing Muhammad, Luz announced that he was leaving Charlie Hebdo. According to Inquisitir.com, the stress of being Charlie’s only cartoonist combined with media pressure and a need to rebuild his life following the attack have convinced him to part ways with the publication. Said Luz: “The time came when it was just all too much to bear. There was next to nobody to draw the cartoons. I ended up doing three of every four front-pages. … Each issue is torture because the others are gone. Spending sleepless nights summoning the dead, wondering what Charb, Cabu, Honore, Tignous would have done is exhausting.” Charb, Cabu, Honore and Tignous are the pen names of the cartoonists killed on January 7. As was their custom, they and other staff members were gathered that day around a table, concocting the next issue of the paper through a group dynamic of creative contributions. On that fateful day, Luz was running late—and was therefore not in the Charlie’s Paris office when the murderous Islamic hooligans stormed in. The rest of the survivors now live under police protection, including Luz’s colleagues at other newspapers. Luz hinted that inspiration has been elusive since the tragedy and that he’s lost interest in “returning to normal life as a news cartoonist.” “We’re not heroes,” he said, “—we never were and we never wanted to be.” He stuck around, he explained, only because he survived the attack, to “continue in solidarity, to let nobody down. Except that at one point, it was too much to bear.” Leaving Charlie, Luz said, was a “very personal choice” that will help him “to rebuild, to take back control” of himself. “You don’t know anymore which Luz you are speaking for,” he said, “—the one born on Jan. 7, 1972 or the one that was born for France on the 7th of January 2015.”

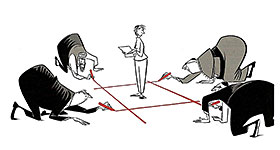

EDITOONISTS IN VARIOUS VENUES of the realm pondered Trudeau’s punching and red-lining. At The Nib, the cartooning corner of Medium.com, Kevin Moore conjured up a helpful guide to appropriate targets for punching—at the upper left of the first of the two accompanying visual aids.

And James Van Otto, next around the clock, provides a vividly visual interpretation of the red line prohibition. Immediately below, Signe Wilkinson shows the best response to offensive cartoons, a theme continued on the next exhibit. At the upper left of the second exhibit, Van Otto continues to play with the red line notion, suggesting a way a cartoonist may gauge the offensiveness of his/her cartoons. Next, John Trever offers a memorable image of the knee-jerk response of Islamic hooligans to whatever offends them, in this instance, the classic endorsement of freedom of expression. And Phil Hands’ visual shows us that while many Muslims might be offended by cartoons of the Prophet, only a tiny minority resort to violence to express their objection. In his response to Cavna’s survey, Rob Rogers alludes to a red-line caution that is probably more to the point than discussions about religious taboos. He said he “avoids images that ... could be antithetical to my intended message.” If an image so outrages readers that they focus only on the cause of their ire and therefore miss on the cartoonist’s message, then the cartoon is rendered useless. To a great extent, this is exactly the problem with Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons when being viewed by people not familiar with either the issues in France or the devices of French cartooning—as we’ll explain at painful length further on.

Trudeau’s Response IN THE ENSUING BROUHAHA, Trudeau was sufficiently embarrassed to do something he rarely does. He consented (or arranged for) an April 26 interview on tv by NBC’s “Meet the Press” moderator, a very friendly Chuck Todd, to whom the cartoonist, looking every bit as chagrined as he clearly was, explained that he was “not at all” blaming the victims and that he “should have made it a little clearer” that he was “as outraged as the rest of the world at the time. I mourn them deeply,” he said—a sentiment not apparent in anything he said in his Polk acceptance speech. (He could not have made his feelings “a little clearer” because they weren’t even slightly evident to begin with.) So

affected was he by the Paris tragedy, Trudeau continued, that he produced a

special Sunday Doonesbury, memorializing the slaughtered cartoonists. The “powerless, disenfranchised minority” on whose behalf he spoke are the millions of French Muslims who immigrated to France from northern Africa and the one-time French colony Algiers but who have not yet, for one reason or another, been assimilated into their new home. They live in abject ghettos around the fringes of large cities. Their separateness and isolation is partly self-imposed: many French Muslims wish to continue Islam’s religious practices in conduct and dress, thereby invading the French public square with religion in a way that the French have rigorously opposed. In freeing itself from centuries of Catholic Church dominance in private and public life, the French have erected an insurmountable wall to keep church separate from state. To the French, then, their Muslim countrymen threaten a hard-won tradition that the French treasure zealously. It is possible, as Trudeau has demonstrated, to see Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons as striking back at a French Muslim population’s insistence on making religion an active and evident part of daily life, something the French tradition and law strictly forbids—despite Charlie’s repeated claim that the magazine was, in Trudeau’s terms, “punching up.” Charlie Hebdo maintains that in mocking religion their aim has been not to attack religion itself, but rather the role of religion in politics and the blurring of lines in-between, which they see as promoting totalitarianism—an argument some have made about the incursion of religion into American politics. And most, if not all, of Charlie’s cartoons can be understood in that context. The paper sees itself as an equal opportunity offender: past covers showed retired Pope Benedict XVI in amorous embrace with a Vatican guard, former French president Sarkozy looking like a sick vampire, and an Orthodox Jew kissing a Nazi soldier. The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik described the cover of a special Christmas issue entitled “The True Story of Baby Jesus”; it was “a drawing of a startled Mary giving notably frontal birth to her child.” But if the pictures in Charlie Hebdo are offensive to some, they are also intended to make us laugh, to see the absurd follies of human hypocrisy running rampant through our so-called civilization. “The aim is to laugh,” said Charlie journalist Laurent Lege (quoted by Megan Gibson at time.com). “We want to laugh at the extremists—every extremist. They can be Muslim, Jewish, Catholic. Everyone can be religious, but extremist thoughts and acts we cannot accept.” “We’re a newspaper against religions as soon as they enter into the political and public realm,” editor-in-chief Gerard Biard told the New York Times in 2012, adding that religious leaders, and Islamic leaders in particular, have manipulated their followers for political purposes. As Signe Wilkinson said in Cavna’s survey: once a religious group “becomes part of the political process, they should be treated as the political players they are.” Trudeau, however, sees it differently. In his “Meet the Press” interview, he returned to the ideas in his Polk speech. (What follows is quoted from a report at TheNib.com. I could not find these remarks in either the broadcast interview or in the extended version of it streamed at nbc.com; but what I’m quoting seems consistent with those of Trudeau’s remarks I could find. Perhaps the elaboration that appears herewith came during remarks Trudeau made at the Richmond Forum in January.) “I was as outraged as the rest of the world at the time [of the Paris killing of the Charlie cartoonists]. I mourn them deeply. We’re a very small fraternity of political cartoonists around the globe. ... What I didn’t do is necessarily agree with the decisions they made that brought a world of pain to France. I think that in France the wider Muslim community feels disempowered and disenfranchised in ways I’m sure is also true in this country. And that while I would imagine only a tiny fraction were sympathetic to the acts that were carried out and the killings, I think probably the vast majority shared in the outrage. Certainly that seems to be what people are hearing in the schoolyards in France now. They’re finding common cause at least with the issue if not with the action. I think that’s bad for France, it’s unfortunate. It’s a tragedy that could have been avoided. But everybody has to decide where the red lines are for themselves.” On the one hand, Trudeau says “no, not at all” does he blame the victims; he blames only “the decisions they made.” In other words—on the other hand— he blames the victims. Writing dialogue for his Amazon Prime political tv show, “Alpha House,” has evidently equipped Trudeau with all of the argot of equivocation deployed by the pandering politician who is adept at saying one thing and then contradicting himself in the next breath in order to appeal to a different audience—or to cover his/her butt—all the while, failing to see that he/she has reduced communication to blather by committing blatant hypocrisy. Suddenly, Trudeau the master satirist is guilty of some of the sins he so deftly skewers in politicians. Then he was rescued as the journalistic spotlight turned to PEN and its hypocrisies—: