|

|||||||||||||||||||

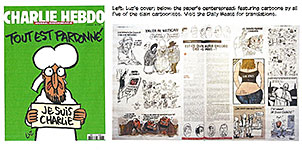

Opus 335: (January 16, 2015). This time, we review of the tragic killing of cartoonists in Paris last week, a rage-fueled attack on freedom by barbaric Islamist Hooligans, who, in their bloodthirsty assault on the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, unwittingly attest to the power of cartoons, their universal value affirmed and validated by the world-wide outrage that the attempted murder of freedom provoked. Accompanied by a selection of cartoons that illustrate the provocative high-spirited iconoclastic perversity of the paper’s satiric comedy, the report also includes an international collection of cartoonist reactions to the murders—both in visual and verbal forms, cartoons of anger and sorrow, and discussions of the role of cartoons in free societies. A slightly shorter version of this report appears at The Comics Journal online (tcj.com); this version offers more detail and discussion, plus many more cartoons. It all begins here—:

FREEDOM UNDER ATTACK Je Suis Charlie BLOODTHIRSTY ISLAMIST HOOLIGANS swatted at a persistently annoying gadfly on Wednesday, January 7. But the slap was deadly. Two black-masked gunmen shouting "Allahu akbar!" stormed through the Paris offices of a provocative satirical newspaper, killing 12 people, including its editor, before escaping in a black Citroen, one of them yelling as they came back through the building, “We have avenged the Prophet Muhammad. We have killed Charlie Hebdo!” Charlie Hebdo, as everyone reading this now knows, is the name of the newspaper, a weekly publication of cartoons and articles. The shootings rank as one of the deadliest attacks in Paris in decades, said the Associated Press report, surpassing the death toll from a 1995 bombing at the Saint-Michel subway station that killed eight. The assault, which began about 11:30 a.m., proceeded methodically with near military precision. Dressed in black, the butchers knew exactly what they were about. At the entry of the building, encountering the only obstacle they faced, a locked door, they threatened an arriving cartoonist (Corinne Rey, known as Coco) and her daughter accompanying her, and Rey opened the door with a security code. Then, following the thugs into the building, Rey and her daughter crept under a desk as the hooligans fired their AK-47s randomly at people in the lobby then went directly upstairs to the Charlie’s second floor newsroom. The barbaric mad dogs knew their mission and went about it without hesitation. Asking for Charb, the pen-name of the newspaper’s editorial director and one of France’s best-known cartoonists, Stephane Charbonnier, the murderers found him in an editorial meeting with seven staff members and his bodyguard. Going straight for Charb, they shot him first, then his bodyguard, and then turned their weapons on the rest of the people in the room, killing them all, including three of the paper’s other celebrated cartoonists. (Later accounts reported that the killing was done “execution style” by lining up the victims. But I doubt that: the butchers were in the building less that five minutes, Rey said, which doesn’t allow much time for execution squad formalities.) Strolling calmly out of the building, one of the savages said to a man he passed, “You can tell the media that it’s al-Qaeda in Yemen.” They left behind them four critically wounded and two more dead—a maintenance worker and a visitor. Just outside the building, they shot and wounded a police officer and then one of the goons calmly dispatched him with a shot to the head as the cop writhed on the sidewalk. Then the hooligans got into the waiting car and sped off. Within a few hours, authorities knew the names of the two attackers—brothers Said and Cherif Kouachi, in their thirties. Both were well-known to counter terrorism agencies: in 2008, Cherif’d served 18 months in prison for terrorism activities, funneling fighters to Iraq’s insurgency. Initial reports said a third hooligan accompanied the brothers—or was the driver of their getaway car. This was 18-year-old Mourad Hamyd, but he surrendered to police in a small town some distance from Paris, saying he was not involved: he’d been in school at the time of the attack, an assertion quickly supported by his classmates. The brothers drove away, crashed the car, stole another, drove away some more and ran their vehicle into a ditch 220 miles northeast of Paris. By the next day, they’d found refuge in a printing plant, where the police cornered them. Friday evening, they came busting out of the building, guns blazing, like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The police answered fire and killed them both, providing them with the pointless martyrdom they aspired to. In an odd quirk, at the same time, the police killed another terrorist who was holding hostages in a kosher grocery store in another part of Paris. He killed four and then declared he’d kill the rest if the authorities pursued the brothers. For a while, the supposition was that the brothers and he collaborated in a joint operation. Don’t think so: although the loner knew the brothers, served time in prison with one of them and had a cache of weapons and ammunition in his apartment, I think he was simply a terrorist opportunist, taking advantage of the brothers’ momentary notoriety to garner a little bloody glory for himself. And, he would allege, for Allah. Early reports said he was accompanied by his so-called wife, who may have killed a policeman on the way into the grocery; maybe he did. Later reports said she’d left the country before the attacks. She was still at large by the end of the week—in Turkey or Syria. As the week wore on, the brothers’ connection to other radical Islamists in France surfaced, and the news media, ever eager to make a good story more sensational, have doggedly pursued the idea that all three of the terrorists were part of a “cell” of Islamic extremists, secretly planning to blow up France. Authorities are now looking for the other members of the cell. Such a group may exist. I believe, however, that such rationales imagine radical Muslims as members of a coherent organization instead of loosely-affiliated believers in worldwide jihad with little to unite them except their belief in violent vengeful actions against civilized persons whose apparent beliefs the jihadists do not approve of. If a “cell” exists, it is more likely the coagulation of accidental acquaintanceship than any deliberate organizational effort. The brothers were well-known to French intelligence agencies. One was a sometime pizza delivery man; the other, an unemployed zealot. If they were known terrorists, would-be trouble-makers, why weren’t they being constantly watched? By one estimate pronounced by a CNN gasbag, there may be worldwide as many as 15,000 jihadists like the brothers—all having served in the holy wars in Syria or elsewhere in the incendiary Mideast and now back in their home countries. Even if the actual number is only half that, it’s too many to keep under surveillance by police forces living on budgets.

THE VICTIMS at Charlie Hebdo that ghastly morning included four of the country’s most revered and iconoclastic cartoonists, celebrated for their critiques of all forms of authority, from government to religion to the military. None were what we’d call young firebrands; three were senior firebrands, peevish elderly satirists with a lively sense of the absurd born of years of living with it. Georges Wolinski, 80, a famous cartoonist who also worked for Paris Match magazine, was awarded the Legion of Honor, France’s highest decoration, in 2005. Jean Cabut, 76, known by his pen name Cabu, had since the 1960s embodied a deep French tradition of no-limits mocking of public and political figures. “Wolinski and Cabu were the tenors of the libertarian wish to establish the greatest liberty of expression,” Patrick Eveno, a professor for media history at the Sorbonne, told the Wall Street Journal. Bernard Verlhac, 57, aka Tignous, was a member of Cartoonists for Peace and Press Judiciare, an association of French journalists covering the courts. The youngest of the quartet of renowned cartoonists was editor Charbonnier, 47, a staunch defender of the paper’s provocative approach, who was receiving light police protection after earlier incidents. Nearby, we’ve posted a short gallery of sample cartoons by each of the four.

The rest of the dead staffers were Bernard Maris, an economist who was a contributor to the newspaper heard regularly on French radio; Philippe Honore, a staff artist; Elsa Cayat, a psychiatrist and writer; and Mustapha Ourrad, a proofreader. “It is too much. It’s unbearable, abominable, inhuman,” cartoonist Maurice Sinet, who worked for more than 20 years at Charlie Hebdo, said by email. “I have no words to describe how devastated and sad I am.” The slain maintenance worker was Frederi Boisseau; the visitor, Michel Renaud; Charb’s bodyguard was Franck Brinsolaro; the other cop, the one killed on the sidewalk outside, was Ahmed Merabet. Merabet was a Muslim; so was Ourrad. So, protestations of high religious purpose to the contrary notwithstanding, the killing was not about religion. “This is yet another reminder of what we are facing together,” said UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. “It should never be seen as a war of religion, for religion or on religion. It is an assault on our common humanity, designed to terrify and incite.” Heartless Islamist hooligan stunts of this sort are more likely to be about unemployed and penniless and therefore desperate people, who see no future for themselves—no wife, no children. Why live? And so they lash out at an unfeeling world, using Islam to justify their rage. And many of France’s large Muslim population live in near squalor, jammed into crowded ghettos that grew even more depressing economically during the recent recession. Why rise up now? Why the hooligan attacks in the Mideast as well as in Paris and elsewhere? Poverty and hopelessness have been conditions in the dictator-infested Arab world for decades, even centuries. But now, thanks to the Internet and smart phones, the disenfranchised know about a better world beyond their dusty mud enclaves and villages. And they’re increasingly bitter about not being able to enjoy any of it.

THE DEATHS OF FOUR of the paper’s notable cartoooning talents is a blow, but at Charlie Hebdo, the blow is more than the sum of its parts and will be felt even more than it would be at other publications. Cartooning at the paper is a collaborative process: each cartoonist contributes to the work of the others, and together they orchestrate the satiric comedy in each issue. Francoise Mouly, The New Yorker’s art director, grew up in France, and Charlie Hebdo’s cartoonists were the idols of her youth. She visited the paper’s offices when she was young, and again, years later, when she went to Paris with her husband, cartoonist Art Spiegelman. She was struck by how they practiced their craft, she told Michael Cavna at the Washington Post’s ComicRiffs. Most cartoonists work in relative solitude, she said, but these artists, as they shared bread and ideas, fed off each other’s company. “These cartoonists really worked together,” Mouly recalls. “We went on the day of the week when they did the drawings. They were sitting around an enormous table, passing around drawings, and there were ample amounts of red wine and baguettes, and they had Magic Markers and blank paper, and they were making doodles and passing them on to each other. “It was seeing creation,” Mouly remembered. “It was the process of creation, which is always arduous and seldom a social time. But those cartoonists were getting together and needling the ideas out of each other. And it encouraged a kind of breaking of boundaries and taboos. They were primarily each other’s audience.” Mouly has distinct memories, too, of Wolinski and Cabu, who even when she knew them when she was a young and politically active artist, were, she said, among the scene’s “old guard.” Wolinski was one of the founders of Hara-Kiri, the satirical paper out of which Charlie Hebdo grew. At Charlie Hebdo, Wolinski “was ubiquitous,” Mouly remembers. “He was really the inventor [there] of this kind of vulgar and provocative humor. Even when I was a kid, it was so clear. … He was a sexist pig, even during the [rise of] feminism. … There were no off-limits for him—whether it was religion or sex or the government.” Writing in The New Yorker the week after the massacre, Adam Gopnik, an American who lives in Paris and knew the cartoonists, described a poster Wolinski created to promote early retirement: it “showed a happily retired man grabbing the rear ends of two apparently compliant miniskirted women. ‘Life Begins at Sixty’ was the jaunty caption. “Wolinski,” Gopnik continued, “for all his provocations, was a life-affirming and broadly cultured bon vivant, who became something of an institution.” He was impressive, Mouly said. “He was fast and casual in his drawing. He insisted on not slowing down and being careful. It was cartooning as a joy manifest.” That almost wanton glee inspired other cartoonists. “Because when somebody pushes the boundaries so far open, you can’t help but notice,” Mouly told Cavna. “He kept the field from ever feeling pompous or self-righteous or even safe.” Cabu, by comparison, was more controlled. “His personality was less abrasive—he was sweeter,” Mouly recalls. And on the page, “he was more of a [textured] social commentator—and more of an individualist.” Together, they were crucial parts of an artistic scene in which everybody knew everybody. These artists challenged each other, pushed each other—and saluted each other when one would get censored, offering a hearty and sincere “lucky you!” It was, Mouly said, like an intellectual “demolition derby.” Another cartoonist, India’s Vishwajyoti Ghosh, remembered for BBC her inaugural visit to Charlie Hebdo. At the center of her memory was of a big round table, generously spread with paper and black markers. “The editorial meeting was underway early in the morning. Some of the artists had arrived; some were on their way. “Ideation had begun.” As the cartoonists began thinking aloud, the editor stood by a white board, noting ideas and themes for the coming issue. ‘So this is how it works,’ I said to myself, ‘—a 12-pager with only political cartoons, strips and a small editorial.’ “As the meeting progressed, more ideas and jokes were tossed back and forth across the table. Some of the cartoonists had already begun their day, doodling furiously ... drawing, poking at both sides of a debate. ... In no time, the cartoons were finding their way to the display board from where the best would be picked to be in the paper. The editor and the senior staff would discuss the pieces and then long debates would follow. Highly democratic and typically French. ... Looking through many issues of the paper, it was clear that no one would be spared—the god men, the institutions, the homophobes, religions. ...” The light-hearted communal comedy was infected with rank irreverence, a noisy anarchist Rabelasian spirit that yielded in handmade drawings, as Gopnik put it, “the living sign of an ornery human intention, rearing up” against misbegotten piety. And henceforth, the high spirited verbal and visual debate out of which each issue of Charlie Hebdo grew will be a little muted—not silenced, as it turns out, but perhaps not as boisterous and vociferous as before.

REACTION France’s president Francois Hollande called the slayings a display of extraordinary “barbarism”—“without a doubt,” an act of terrorism. He appealed to citizens not to see the violence as the product of Islam but rather as the acts of “fanatics” that “have nothing to do with the Muslim religion.” And he declared Thursday a day of national mourning. At noon Thusday, Paris’ famed Metro came to a standstill and a crowd stood silently near Nortre Dame cathedral. That evening, the lights on the Eiffel Tower went out “in tribute to the dead from the elegant iron lady that symbolizes France to the world,” as the Associated Press put it. Hollande vowed that the terrorists would not win: “There is no barbaric act that will ever extinguish the freedom of the press.” Former French president Nicolas Sarkozy said the assault was a “direct and savage attack against one of our most revered republican ideals: the freedom of expression.” In a condolence letter addressed to President Hollande, Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany said: “This horrible act is not only an attack on the lives of French citizens and the domestic security of France, it also stands as an attack on the freedom of expression and the press, a core element of our free, democratic culture that can in no way be justified.” Other world leaders condemnned what U.S. President Barack Obama called the “cowardly, evil attacks” and pledged solidarity with France. “The fact that this was an attack on journalists, an attack on our free press, also underscores the degree to which these terrorists fear freedom of speech,” Obama told reporters in brief remarks in the Oval Office. “Time and again, the French people have stood up for the universal values that generations of our people have defended. France, and the great city of Paris where this outrageous attack took place, offer the world a timeless example that will endure well beyond the hateful vision of these killers.” The next day, Obama elaborated: "In the streets of Paris, the world has seen once again what terrorists stand for. They have nothing to offer but hatred and human suffering. We stand for freedom, hope, and the dignity of all human beings and that’s what the city of Paris represents to the world," he finished, adding that the U.S. stands ready to "provide whatever support our ally needs in confronting this challenge." Even Russian President Vladimir Putin condemned the attack, calling it a "cynical crime," and pledging cooperation in fighting terrorism, And the Muslim community was not silent. Dalil Boubakeur, the rector of the Grand Mosque in Paris, one of France’s largest, expressed horror at the assault on Charlie Hebdo. “We are shocked and surprised that something like this could happen in the center of Paris,” he said, according to Europe1, a radio broadcaster. “We strongly condemn these kinds of acts and we expect the authorities to take the most appropriate measures,” he said, adding: “This is a deafening declaration of war. Times have changed, and we are now entering a new era of confrontation.” Mohammed Moussaoui, president of the Union of French mosques, condemned the "hateful act," and urged Muslims and Christians "to intensify their actions to give more strength to this dialogue, to make a united front against extremism." Saudi Arabia’s leading body of Muslim clerics condemned the attack and said it could have no acceptable justification. (But on Friday, the Associated Press pointed out, the Saudis sent a contradictory message: a young Saudi was whipped 50 times in a public square for insulting Islam in his blog; the flogging will be repeated for the next 19 days, and then the youth will go to jail for ten years.) An American journalist, Claire Berlinksi, who happened to be in Paris and near the offices of Charlie Hebdo within hours of the attack, wrote about it for Time: “This was an attack on France. It was an outright declaration of war. It was an attack on press freedom in particular—on journalists, writers, cartoonists and intellectuals who were as well-known here as Jon Steward and Stephen Colbert are to Americans. They were known above all for their willingness to say whatever they damn well pleased—no matter whom they offended or how many death threats resulted. “While their publication was best known for its parodies of Muslm extremists,” Berlinksi continued, “they were more than happy to say whatever they pleased about Jews and Catholics too—and never were that respectful, either. But only radical Islamists thought the proper rejoinder was simply to kill them all.” At his blog at Cagle Cartoons, the syndicate owner/editoonist Daryl Cagle wrote: “Terrorists have no sense of humor. Cartoons loom large in the Arab world [but not to make people laugh; their caricatures foster hatred]; they’re typically on the front pages of Arab language newspapers. It is no wonder that our cartoons seem to bother the terrorists more than our words. Sitting behind a beer with Charlie Hebdo cartoonists [as Cagle has done on occasion], the talk often turned to Islamic extremists and their assaults on press freedoms. No one can doubt that editorial cartoonists are leading the fight for press freedoms now.” He continued: “Today we are grieving, but as we move forward, I hope that our cartoons won’t be chilled by these murders and that the cartooning community will step up to this challenge with even more brilliant and insightful work. I’m sure the French cartoonists will do that; they are my heroes.” In France on Saturday, the Washington Post reported, prime minister Manuel Valls heeded Berlinski’s call, declaring that France was “at war” with radical Islam—“a war against terrorism, against jihadism, against everything that is intended to break fraternity, liberty and solidarity.” I wonder what such a war will look like. More airport security? More armed guards in the lobbies of newspapers and government buildings? A proper war against radical Islam would not give the extremists what they want. It would not reduce freedom—even in the name of security. Instead, it would increase freedom. It would immediately do away with airport security; we would no longer have to remove our shoes in order to board an airplane. By remaining free, we defeat the enemies of freedom—i.e., the radical Islamists, the Cutthroat CalipHATE and all its ilk. Conversely, by beefing up security—which inherently limits freedom—we admit to being fearful, and we become hesitant. And the radical Islamists win.

NOT EVERYONE is supportive of the satirical newspaper. Bill Donohue, president of the Catholic League, a U.S. organization that "defends the rights of Catholics," issued a statement titled "Muslims are right to be angry." In it, Donohue criticized Charlie Hebdo’s history of offending the world's religiously devout, including non-Muslims. The murdered editor Charbonnier "didn’t understand the role he played in his [own] tragic death," the statement reads. "Killing in response to insult, no matter how gross, must be unequivocally condemned. That is why what happened in Paris cannot be tolerated," says Donohue. "But neither should we tolerate the kind of intolerance that provoked this violent reaction." The statement says Charlie Hebdo has "a long and disgusting record of going way beyond the mere lampooning" of religious figures. "They have shown nuns masturbating and popes wearing condoms," Donohue says. "They have also shown Muhammad in pornographic poses." Among the covers is a racy depiction of the Christian Holy Trinity locked in a three-way homosexual orgy (as part of a critique of French religious leaders' opposition to gay marriage) and a whole array of images mocking pedophilia by priests. Charlie Hebdo doesn't pull its punches. But some critics say it goes too far, specifically with Muslims. The newspaper, after all, fired a cartoonist who published an article deemed anti-Semitic in 2008. But when it comes to depicting Islam, writes the Financial Times' Tony Barber, the publication has no qualms specifically "mocking, baiting and needling French Muslims." Donohue, clinging to a defense of religious sensitivities bound to infuriate free-speech advocates and secularists, pins the fault of a terror attack on its victims. The statement ends with a quote from U.S. founding father James Madison: "Liberty may be endangered by the abuses of liberty, as well as by the abuses of power." In other words, we may be free to speak, but we have to appreciate the value of that right. On social media, supporters of militant Islamic groups praised the attack. One self-described Tunisian loyalist of al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group tweeted that the attack was well-deserved revenge against France, which has the largest Muslim population in Europe (mostly refugees from former French colonies in west and north Africa). An al-Qaeda tweeter who communicated Wednesday with AP said the group is not claiming responsibility, but called the attack "inspiring."

THE ATTACK comes as thousands of Europeans have gone to join jihadist groups in Iraq and Syria, further fueling concerns about Islamic radicalism and terrorism being imported when jihadists return to their native countries. Those concerns have been particularly acute in France where fears have grown that militants are seeking to target French citizens in retaliation for the government’s support for the United States-led air campaign against jihadists with the Cutthroat Caliphate group in Syria and Iraq. On the Internet, the hashtag #JeSuisCharlie (“I am Charlie”) was trending as people expressed support for the paper and for journalistic freedom. As news of the attack spread, an outpouring of grief mixed with expressions of dismay and demonstrations of solidarity for free speech. By the evening, not far from the site of the attack in the east of Paris, an estimated 35,000 gathered at Place de La République—young and old, and various classes—some chanting, “Charlie! Charlie!” or holding signs of solidarity reading, “Je suis Charlie”—the message posted on the newspaper’s website. Spontaneous vigils of hundreds and thousands formed in other cities around France and elsewhere in Europe. Cartoonists worldwide reacted with their pens—and pencils.

The pencil quickly emerged as a powerful symbol, an icon of defiant cartooning more potent than a blood-spattered drawingboard. The Atlantic asked its artists for their reaction; we’ve posted several at the end of the adjacent exhibit, on the same page as The New Yorker cover. At The New Yorker, one of the last bastions of magazine cartooning in the U.S., Francoise Mouly chose for the cover of the issue the week after the massacre the stark and stirring picture by Madrid-based artist Ana Juan—a pencil and the Eiffel Tower bonded into a single soaring image of defiance, a scornful middle finger of French resistance. Said Mouly: “When I saw this image, I felt the sobriety and the simplicity. I felt that kind of ‘hit’ that reaches into your brain and realigns [you]. It ‘reads’ right away.” Plus, Mouly noted as she spoke with ComicRiffs, “It was ambiguous. It’s not a good idea to put words to pictures that are so powerful. It hits you in a visceral way. … There is the bloodbath [at the bottom of the frame] and the picture comes to the lead of the pencil. As if to say: What happens next?”

ON THE DAY OF THE TRAGEDY, the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) posted a statement at 10 a.m. EST: The gruesome attack on the Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris today reminds us that freedom of expression in cartooning is not a given in many parts of the world. Charlie Hebdo was also attacked in 2011, and continued to publish. The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists condemns this revolting act of violence, and stands with the international cartooning community in mourning the loss of twelve people, including police officers who were murdered. President Hollande has called this an act of terrorism, and whether it was the work of those merely inspired by ISIS or those given direct orders doesn’t matter. Cartoonists and journalists around the world should be permitted to express themselves freely without fear of reprisal. These types of attacks merely serve to illustrate how important the free spirit of cartoon commentary is, and how cartoonists make a difference in helping to expose hypocrisy. Furthermore, newspapers should not hesitate to publish material from the magazine that allegedly incited the incident. More freedom of expression and not less demonstrates courage in the face of attacks. Shrinking from a newspaper’s watchdog role only encourages more terror. The AAEC board and membership expresses its sincere condolences to the innocent victims at this tragic moment, and calls for international solidarity with the cause of cartooning and freedom of artistic expression. The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund added its voice to the chorus of solidarity. “The attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices is tragic,” said CBLDF executive director Charles Brownstein, “but it is also proof of just how powerful cartoons and cartoonists can be. Despite threats and prior attacks, the publishers, editors and cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo never relented in using satire to question the world around them. CBLDF stands with Charlie Hebdo and their dedication to free expression. Our thoughts are with the victims and their famileis and colleagues.” CBLDF’s official statement ends: “After the 2011 firebomb attack [on Charlie Hebdo offices], French prime minister Francois Fillon called freedom of expression ‘an inalienable right in our democracy’ and that ‘all attacks on the freedom of the press must be condemned with the greatest firmness.’ “That commitment—in France and anywhere else—should not waver in the face of today’s brutality. The National Coalition Against Censorship and many other organizations committed to the fundamental value of free expression condemn these hideous and barbaric attacks, which represent a chilling and extreme assault on freedom of speech. The failure to stand up for free expression emboldens those who seek to attack and undermine it.”

THE LEGACY Charlie Hebdo is no stranger to controversy for its lampoons on an array of subjects, including Christianity. But what it's done on Islam has gotten the most attention and garnered the most vitriol. “We’re a newspaper against religions as soon as they enter into the political and public realm,” editor-in-chief Gérard Biard told the New York Times in 2012, adding that religious leaders, and Islamic leaders in particular, have manipulated their followers for political purposes. Charlie Hebdo was founded in 1970 by journalists from the defunct satirical Hara-Kiri, which had been banned that year for mocking the death of former President Charles de Gaulle. The paper’s name is a tribute to Charlie Brown in the Peanuts comic strips that were reprinted in Charlie Hebdo’s pages in the early years— plus being “a mockery of Charles de Gaulle,” according to Gopnik. “Hebdo” (short for “hebdomadaire”) means “weekly.” Under its sometime subtitle “Journal Irresponsable,” the paper earned its reputation with “garish front-page cartoons and incendiary headlines,” the BBC reported. "Drawing on France's strong tradition of bandes dessinees [comic strips], cartoons and caricatures are Charlie Hebdo's defining feature." Charlie Hebdo has often put France’s secular dogma to the test, printing caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad on several occasions. Pictures of the Prophet are viewed as insulting or even blasphemous by many Muslims (but not, contrary to popular belief, by all). But the paper is an equal opportunity offender: past covers showed retired Pope Benedict XVI in amorous embrace with a Vatican guard, former French president Sarkozy looking like a sick vampire, and an Orthodox Jew kissing a Nazi soldier. Gopnik described the cover of a special Christmas issue entitled “The True Story of Baby Jesus”; it was “a drawing of a startled Mary giving notably frontal birth to her child.” Charlie Hebdo published violent or sexually explicit drawings of nuns, politicians of every stripe, and the police that are guaranteed to offend the public. "Anything to make a point," the BBC averred. Denver Post editorial page editor Vincent Carroll acknowledged (January 11) that the U.S. is hardly devoid of provocative, insulting commentators, but he claims (and I agree) that Bill Maher may be the “big name entertainer closest in spirit to Charlie Hebdo: a militant atheist who flails all religion while singling out Islam for special critique. For anyone who doesn’t share his utter contempt for religion, Maher is a hard guy to warm up to. Still, you have to praise his courage—now more than ever.” Carroll quotes Maher’s comment recently to Jimmy Kimmel: “I’m a satirist who deals with this subject particularly,”Maher said. “It’s kind of scary that some people say you cannot make a joke.” Said Carroll: “Very scary, actually. So whether you admire their work or not, let us wish a long life to satirists willing to mock the very theocrats who would kill them if they could.” Charlie Hebdo probably began stoking controversy and earning the ire of the Muslim community in 2006, when it republished satirical cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad that had appeared in a Danish newspaper, Jyllands-Posten, in the fall of 2005. The reprinted cartoons prompted a lawsuit by two French Muslim groups, which accused Charlie Hebdo of slander. The magazine was later acquitted. The next year, one of Charlie Hebdo's covers depicted the Prophet covering his eyes, next to the words "Muhammed overwhelmed by extremists," and thinking to himself, "It is hard to be worshiped by idiots." The Grand Mosque of Paris and the Union of Islamic Organizations of France filed slander charges, but a French court cleared the paper. In 2011, the office of the weekly was badly damaged by a firebomb the day after it published a spoof issue “guest edited” by the “Profit” Muhammad to salute the victory of an Islamist party in Tunisian elections; inside, the pages were blank. It also announced plans to publish a special issue renamed “Charia Hebdo,” a play on the word in French for Shariah law, promising “100 lashes if you don’t die laughing.” Editor Charbonnier was unfazed by the bombing. “This is the first time we have been physically attacked, but we won’t let it get to us,” he vowed. But after the bombing, Charlie Hebdo moved to a nondescript building in a different area of Paris, and for a time, the offices were guarded by police. The week after the bombing, the paper was back with its usual bag of defiant, disrespectful tricks, publishing one of its most famous covers, the one called “the kissing cover” in the following discussion. Writing at vox.com just after the January 7 attack, Max Fisher elaborated on the paper’s philosophical stance (in italics). It would do a profound disservice to Charlie Hebdo and its leading cartoonists, many of whom were murdered in the attack, to describe it as an anti-Islam or anti-religion magazine or to portray it as having provoked just for the sake of provocation. The Charlie Hebdo cartoonists were making a substantial point with their cartoons. That point is perfectly summed up, albeit in ways more subtle than first meet the eye, in one of its most famous covers, from November 2011, that depicts Charlie Hebdo (with a pencil behind his ear) kissing a generic Muslim man. In the background are the smouldering ashes of the Charlie Hebdo office. The magazine was not criticized just by Islamist extremists. At different points, even France’s devoutly secular politicians have questioned whether the paper went too far. French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius once asked of its cartoons, “Is it really sensible or intelligent to pour oil on the fire? It is, actually. Part of Charlie Hebdo’s point was that respecting these taboos strengthens their censorial power. Worse, allowing extremists to set the limits of conversation validates and entrenches the extremists’ premises—that free speech and religion are inherently at odds (they are not) and that there is some civilizational conflict between Islam and the West (there isn’t). These are also arguments, by the way, make by Islamophobes and racists, particularly in France, where hatred of Muslim immigrants from north and west Africa is a serious problem. And that is exactly why Charlie Hebdo’s kissing cover with the title “Love is stronger than hate” so well captures the magazine’s oft-misunderstood mission and message. Yes, the slobbery kiss between two men is surely meant to get under the skin of any conservative Muslims who are also homophobic, but so too is it an attack on the idea that Muslims or Islam are the enemy rather than extremism and intolerance. Laurent Leger, a Charlie Hebdo staffer who survived the January 7 attack, told CNN in 2012 that “the aim is to laugh. ... We want to laugh at the extremists—every extremist. They can be Muslim, Jewish, Catholic. Everyone can be religious, but extremist thoughts and acts we cannot accept.” That this mission had gotten the magazine attacked in the past, and may have contributed to the terrorists’ motivation in murdering its staff today, should show us all just how important it is, and how high the stakes are for all of us.

IN 2012, CHARLIE HEBDO RESPONDED to the Muslim protest in the Middle East over an insulting internet video mocking Muhammad, publishing several crude caricatures of Muhammad, some of which depicted him naked. The French government condemned the decision to publish the pictures as “irresponsible at a time of violence and unrest across the Islamic world” and urged the magazine to reconsider. When the paper’s editors refused, the French government closed embassies, consulates, cultural centers, and schools in about 20 countries and enhanced police protection at the magazine’s office. President Obama’s spokesman at the time questioned the publication’s “judgement.” Both governmental responses, said Charles Lane at the Washington Post (January 11), were ill-advised: “To be sure, both officials quickly added that Charlie Hebdo had a right to publish what it wanted and that no mere publication or video could justify violence.” Yet the message was mixed, “unavoidably implying that the rioters had a valid point—which is something you never want to imply, at least not if you understand how dangerous it is to give violent extremists a veto over what your citizens can and cannot say.” Obama would do better when Sony knuckled under to North Korean threats: “If somebody is able to intimidate us out of releasing a satirical movie, imagine what they start doing once they see a documentary that they don’t like or news reports that they don’t like.” Or cartoons they don’t like. At about the time of the government’s 2012 cautioning, in an interview with Le Monde newspaper, Charbonnier gave little indication that he planned to change Charlie Hebdo's ways. "It may sound pompous," he said, "but I'd rather die standing than live on my knees." Charb was ever a stout defender of the paper’s rights. "I don't blame Muslims for not laughing at our drawings," he told Reuters in 2012. "I live under French law. I don't live under Quranic law." In an interview with ABC News, Charbonnier said Charlie Hebdo wouldn't bend to threats or attacks. "We are provocative today. We will be provocative tomorrow. I do this because it's our job to draw about actuality," he said. He said his job was not to defend freedom of speech. "But without freedom of speech we are dead. We can't live in a country without freedom of speech. I prefer to die than live like a rat." Besides, he once said, extremists bent on violence will seize on any excuse for their actions, implying that if he changed Charlie Hebdo’s approach, the paper’s foes would just manufacture another reason to attack it. The Denver Post’s Carroll admires the “unforgettable daily courage of the Charlie Hebdo victims. They were on notice. ... They had been warned, in effect, by the murder of the Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh, the riots and threats over the infamous Danish cartoons, the beating and house-burning of a Swedish cartoonist, and multiple other incidents [including Muslim reaction to the internet video]. ... And yet they never flinched. Our expressions of solidarity with these free-speech martyrs are embarrassingly feeble by comparison.” At the Washington Post, Lane came out loud and clear in support of Charlie Hebdo: “If freedom means anything, it means freedom of expression—to include expressions that some might find irresponsible, offensive or even blasphemous. In the realm of art and ideas, pretty much nothing is, or should be, sacred, lest we head down the slippery slope to censorship or self-censorship.” And Lane admires Charbonnier’s “routine bravery ... practiced in the exercise of his fundamental human right to make fun of all religions. He did this in spite of constant death threats, one bombing and not-so-subtle official pressure to cool it, so as not to inflame the extremists.” Lane quotes Charbonnier: “Everyone is driven by fear, and that is exactly what this small handful of extremists who do not represent anyone want—to make everyone afraid, to shut us all in a cave.” Lane continued: “Charbonnier persisted in acting on those beliefs right up until last Wednesday, when he lost his life for them.”

BOTH AL-QAIDA AND THE CUTTHROAT CALIPHATE have repeatedly threatened to attack France. Just minutes before the attack, Charlie Hebdo had tweeted a satirical cartoon of the Islamic State's leader giving New Year's wishes. Another cartoon, Chard’s last, released in the issue of the week of the attack, featured an armed man who appeared to be a Muslim fighter with a headline that read: “Still no attacks in France. Wait! We have until the end of January to give our best wishes.” In the winter 2014 edition of the al-Qaida magazine Inspire, a so-called chief described where to use a new bomb, saying: "Of course the first priority and the main focus should be on America, then the United Kingdom, then France and so on." The year before, the magazine specifically threatened Charb and included an article titled "France the Imbecile Invader,” adding: “Yes, we can. A bullet a day keeps the infidel away.” Charb’s death, and those of the other staffers, spurred a wave of support for their publication and its practices around France and the world. In Paris on Sunday, the Washington Post reported, “an extraordinary chain of 1.5 million people, led by a group of world leaders linking arms, marched down the Boulevard Voltaire in a show of force meant to illustrate the power of unity and freedom over fanaticism and terror. ... French president Francois Hollande arm-in-arm with German chancellor Angela Merkel and flanked by the likes of Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Palestinian Authority president Mahmoud Abbas and a host of European and African leaders.” (But not President Obama, who was immediately faulted by his knee-jerk Republicon opposition for sending the relatively low-ranking American ambassador to France in his stead. And then the White House did something unexpected, something White Houses don’t do: it admitted it’d made a mistake. Unprecedented.) “Authorities called the Paris march the largest mass rally in French history. An estimated 4 million people nationwide—more than a third of them in Paris—mobilized, with sister demonstrations of support erupting from Ramallah to Sydney to Washington.” In Germany, about 18,000 people gathered at the French Embassy next to Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate. In London, historic landmarks such as the Tower Bridge were lit in the red, white and blue of the French tricolor flag. In Washington, 3,000 people marched silently. In Rome, thousands demonstrated, holding pencils, candles and placards reading “Je suis Charlie.” Adam Gopnik was impressed—in an absurdist fittingly Charlie Hebdo way: “A small irreverent smile comes to the lips at the thought of the flag being lowered, as it was throughout France last week, for these anarchist mischief-makers, and they would surely have roared at the irony of being solemnly mourned and marched for by Sarkozy and Hollande,” both so often targets of the paper’s Rabelaisian wit. “The right to mock and to blaspheme and to make religions and politicians and bien-pensants all look ridiculous was what the paper held dear,” Gopnik finished, “and it is what its cartoonists were killed for—and we diminish their sacrifice if we give their actions shelter in another kind of piety or make them seem too noble, when what they pursued was the joy of ignobility.” Rallies elsewhere took a different, ominous tack. In another part of Paris, xenophobia prevailed as marchers advocated an end to immigration of Muslims and other “foreigners.” In Dresden on Monday, 25,000 marched under the banner of a group calling itself Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the West. Despite official warnings against linking French Muslims with terrorists, incidents of Islamophobic attacks increased in the days since the attack—firebombs, pig’s heads thrown into mosques, and veiled women insulted on the street.

CHARLIE’S FUTURE AND OURS First reports in the hours immediately after the killings suggested that disaster lay ahead for Charlie Hebdo. A note of determination was sounded in some accounts: “How Charlie Hebdo responds to Wednesday’s attack remains to be seen. But if the past is any indication, the magazine will stick to its mission of skewering a wide range of targets: from French politicians and police to religious leaders and historical figures. Charlie Hebdo prides itself on upholding France’s venerable tradition of unfettered mockery in the name of free speech and expression. It also considers itself in opposition to religious backwardness of all faiths.” Right

away, the paper declared that it would continue and would print an astronomical

million copies of its next issue. And the future looked determined if not

exactly bright. Two days later, the press run had been upped to 3 million in

response to numerous outpourings of support. Published the Wednesday after the

attack, the cover is a drawing by Renald Luzier (aka Luz), who reprised his

“100 lashes” caricature of Muhammad, tearful this time, holding a sign that

read: “Je suis Charlie.” Over his head, the words “All is forgiven.” But all was not forgiven. The cover was unruly rejection and high-spirited resistance all over again. It was, Luz explained at a press conference, a continuation of the usual Charlie Hebdo satirically perverse sense of humor: terrorists would expect something quite different, and Charlie Hebdo was not about to give them what they wanted. Charlie was still free. Luz said he’d wept after he drew the cartoon. “Muhammad again,” he said. “I’m sorry. But this Muhammad is above all a fellow who is crying.” We’ll have the story of the production of this memorable issue of Charlie Hebdo in the next R&R, Opus 336. Paris made Charlie Hebdo an honorary citizen, a distinction seldom extended and usually reserved for “distinguished great resistance fighters against dictatorship and barbarism.” According to Reuters, the mayor of Paris told the city council that “by granting citizenship to Charlie Hebdo, Paris—our city—shows a heroic newspaper the respect due to heroes.” Still, Swedish artist Lars Vilks, who lives under police protection after drawing caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad, questioned on NBC online whether Charlie Hebdo would survive the attack. "This will create fear among people on a whole different level than we're used to. Charlie Hebdo was a small oasis. Not many dared do what they did. I don't know what's going to happen to them. Can they continue to publish the magazine?" With a weekly circulation of only about 30,000—and steadily declining in recent years—the future didn’t look rosy. And “Charlie Hebdo has never been a top seller,” reported the Christian Science Monitor. “It stopped publication from 1981 to 1992 for lack of resources and has recently issued appeals on its website for financial support.” Some accounts speculated that the paper would find that its current plight taps a wider vein of sympathy. Happily, that proved to be the case almost immediately. Media organizations Radio France, Le Monde and France Télévisions issued a joint statement pledging to help Charlie Hebdo by supplying the "human and material resources" needed to keep the magazine alive. The trio invited other French media to join the effort to "preserve the principles of independence and freedom of thought and expression." The newspaper Liberation offered office space. Others climbed on the band wagon as it began to roll. French Culture Minister Fleur Pellerin said the government was ready to grant the struggling newspaper one million euros ($1.18 million) “so it can continue next week and the week after that and the week after that.” Within days, Reuters could report that various publishers have contributed 250,000 euros (about $300,000), and a new media fund partly backed by Google said it would do the same. In London, editor-in-chief Alan Rusbridger tweeted that his Guardian Media Group would pitch in 100,000 pounds ($152,410). And Albert Uderzo, the 87-year-old cartoonist who co-created famed Asterix the Gaul with Rene Goscinny, announced that he would come out of retirement to lend a hand in illustrating the weekly. Admitting that Asterix and Charlie Hebdo have nothing in common, Uderzo said: “I just wanted to show my friendship for the cartoonists who paid with their lives.” Meanwhile, French media reported that subscriptions for Charlie Hebdo have soared—with over 80,000 coming in the day after the killings. The mayor of Paris said the city would buy subscriptions for all its 163 council members, and the public bank BpiFrance took out 50. Suddenly, Charlie Hebdo’s future didn’t seem so bleak.

ON THIS SIDE OF THE ATLANTIC, American editorial cartoonists reacted at first in anger and sorrow, as we’ve seen in their cartoons. But they also reflected upon their craft and its power. “Cartoons are incredibly powerful,” said provocateur Ted Rall on the day after the murders. “Not to denigrate writing (especially since I do a lot of it myself), but cartoons elicit far more response from readers, both positive and negative, than prose. Websites that run cartoons, especially political cartoons, are consistently amazed at how much more traffic they generate than words. I have twice been fired by newspapers because my cartoons were too widely read: editors worried that they were overshadowing their other content.” Comics historian and commentator Jeet Heer joined in with a special to the Globe and Mail in Canada. “Wednesday’s murderous attack on the offices of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo is a reminder not only of the horrors of tribalist political violence but also the enduring power of images to both inspire and offend. In his thoughtful 2013 book The Art of Controversy, Victor Navasky convincingly argued that political cartoons are a uniquely potent art form because images impact the human mind more quickly than almost any other form of communication.” And cartoons bother politicians more than most, Navasky maintains, because no one, particularly someone who thinks him/herself important, likes to be laughed at. Cartoons are powerful, Heer goes on, because they are immediately understood. “Images travel at the speed of light, words travel at the speed of sound.” Heer continues in italics: Apart from the power of imagery, in France, there is a specific tradition of shocking and scurrilous visual mockery. Even before the French Revolution, underground prints circulated showing the clergy and nobility performing all sorts of demeaning actions. Pornographic images of Marie Antoinette were particularly popular. The subversive impact of cartoons was a major concern for the authorities. In 1829, the French interior minister François Régis de la Bourdonnaye, comte de la Bretèche, complained, ‘Engravings or lithographs act immediately upon the imagination of the people, like a book which is read with the speed of light; if it wounds modesty or public decency the damage is rapid and irremediable.’ The following year, the French government outlawed attacks on ‘the royal authority’ or ‘inviolability’ of the King’s person. In 1832, this law was used to arrest the cartoonist Charles Philipon, who drew a cartoon (now legendary) showing the King’s jowly face metamorphosing into a pear (‘la poire’ is French slang for ‘fathead’). Facing the court, Philipon asked, ‘Can I help it if His Majesty’s face is like a pear?’ The same year as the trial, Philipon’s friend Honoré Daumier, France’s greatest cartoonist, drew an image of the King as a Rabelaisian giant, sitting on a toilet and eating the food of the poor as he excretes wealth for the nobility. Daumier was jailed for that cartoon, and an 1835 law specifically targeting caricature was introduced, on the grounds that ‘whereas a pamphlet is no more than a violation of opinion, a caricature amounts to an act of violence.’ The law remained in place for decades, leading to at least 15 prosecutions for the crime of cartooning. There is a strand of French cartoons so over the top they have no North American counterpart, aside from the underground cartoons of Robert Crumb (who now lives in France, not surprisingly). Part of what’s going on here is the clash of two ancient traditions— a subset of fundamentalist Islam with its long-standing iconophobia in battle with France with its long-standing tradition of aggressive cartooning. The power of images is at the heart of this story, yet many newspapers and magazines will be afraid to reprint those very images. Heer refers to the 2005 Danish caricatures of Muhammad, which, when circulated in 2006, so infuriated Muslims (mostly extremists but not exclusively) that violence erupted in numerous countries, and people died in riots. Although most newspapers covered these events, few published the cartoons that caused them. Some American papers said they were afraid their correspondents in Muslim countries would be at risk—and, in the editors’ view, needlessly. Pleading a reluctance to insult any religion gratuitously, editors “ decided that it was sufficient to merely describe the cartoons and not necessary to reprint them. But this position,” Heer points out, “is based on the idea that words and images are interchangeable. Yet we have every reason to believe that images are not just a proxy for words, but have their own unique potency.” Not only that: failure to post any of the Danish cartoons deprived the newsstories about the episode of the visual evidence essential for readers to fully understanding the implications of the event—an outright abdication of journalistic responsibility. Some U.S. papers avoided a similar mistake this time. Learning, perhaps, from the ridicule Sony brought upon itself last month by cancelling domestic distribution of “The Interview” out of fear of reprisals from North Korea, some newspapers published a few samples of some of Charlie Hebdo’s scabrous covers. (Not, though, the timorous New York Times.) Alas, many newspapers played right into the terrorists’ hands. “The terrorist knows what scares us,” wrote Stephen L. Carter at Bloomington News. “There is a logic to terrorism, a coldly calculated ends-means rationality. ... In short words, they believe [murder, violent protest] will get them what they want.” Carter continued: “Many news organizations, in reporting on the Paris attack, have made the decision not to show the cartoons that evidently motivated the attackers. This choice is sensibly prudent—who wants to wind up on a hit list?—but from the point of view of the terrorist, it furnishes evidence for the rationality of the action itself. Killing can be a useful weapon if it gets the killer more of what he wants. “Our short-run task,” Carter went on, “is to prove rather than assert him wrong. In the long run, however, the only true means of deterrence is the creation of a new history in which the terrorist is always tracked to his lair and never gets what he wants.”

“IN THE UNITED STATES, in important ways, mainstream political cartooning has long been conducted within certain rules of decorum,” said Christopher Goffard and Maria L. LaGanga in the Los Angles Times. “Cartoons in major publications here rarely approach the deliberate offensiveness of a publication such as Charlie Hebdo, with its seeming delight in provoking offense about taboo subjects such as religion. It is hard to think of an equivalent publication in America — or an equivalent atmosphere of fear.” Goffard and LaGanga talked to David Horsey, a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist at the Los Angeles Times. “He said that he once received a death threat in response to his work but that nobody had confronted him in person.” People who disagree with him, Horsey said, are often his most loyal followers. "They're back every day just to tell me what an idiot I am," he said. "There's not much hate behind it. It's, 'Boy, you're an idiot,' not, 'I'm gonna come get you.'" On the other hand, he said, editorial cartooning is "a very dangerous job in most parts of the world," citing examples from Russia to Sri Lanka. "We're pretty protected because of the nature of our society. In many parts of the world, doing political cartoons about religious groups or about the government lands you in jail or gets you shot or beat up." Pat Bagley, who’s been the editoonist at the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 35 years, makes a big distinction between threats against editorial cartoonists in the United States and those in other parts of the world. "One thing that is different is that in Europe and the Middle East, they take cartoons deadly seriously," said Bagley, who had met several of the slain artists at a cartoonists' salon a couple years ago. "In the U.S., we're more entertainers, and we don't get quite the respect or the response.” Bagley told Goffard and LaGanga that he couldn't remember when an American cartoonist had been assaulted or killed for his or her work. "It happens all the time in the Middle East, and it happens way too often in South America and sometimes in Europe. It's really depressing." "Terrorism really doesn't strike at physical structures as much as it strikes at ideas, and its main fear is ideas," said Jack Ohman, president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists and editoonist at the Sacramento Bee. "And cartoonists are particularly effective at distilling ideas. I find it fascinating that cartoonists who sign their names to their ideas are murdered in cold blood and terrorists ran away from the scene of their ‘statement’ anonymously." Clay Bennett, Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist at the Chattanooga Times Free Press, thinks he understands why cartoonists elicit more threats than writers do. The writers have "a thousand pebbles to throw every day. A cartoonist has a brick. So when you really hit hard, it really does just pop them right in the nose,” he said. "But it still doesn't explain why recently we've seen so much retaliation. That may be a product of an increased amount of extremism." Satire "is the fault line between East and West," said Kevin Kallaugher, editorial cartoonist for The Economist of London and the Baltimore Sun. He told Goffard and LaGanga that he has served as a cultural ambassador in 10 countries through the U.S. Embassy, including Lebanon, Jordan, Azerbaijan. The trips usually entail a week's visit, an exhibit of his cartoons and lots of conversation. "One of the things everyone asks me with regards to the whole Prophet Muhammad issue is, 'Why do you hate us so much? Why do you want to do something satirical about our religious leader? The only reason is to denigrate and hurt us,'" he said. Horsey and others said their first reaction to the news of the massacre was to try to find a way to respond in a cartoon. "It's the only weapon we have, the only tool we have," he said. "This can't go unnoted. So right away, [we think], 'What's the image? What can I say?'" He added, "I think cartoonists all over the world are probably thinking that. 'These people cannot shut us up.'" To Joel Pett, Pulitzer Prize-winner at the Lexington Herald-Leader, the massacre in France serves as a reminder for cartoonists not to squander their opportunity "to draw about something that matters." "It's so tempting to pick the low-hanging fruit — today's infotainment story or joke about John Boehner crying or something that has absolutely no importance," said Pett, chair of the board of directors of Cartoonists Rights Network International. "People are dying out there for free speech. Those of us who enjoy it owe it to them to use it in a responsible way." Writing in The New Yorker online, George Packer said: “The murders in Paris were so specific and so brazen as to make their meaning quite clear. The cartoonists died for an idea. The killers are soldiers in a war against freedom of thought and speech, against tolerance, pluralism, and the right to offend—against everything decent in a democratic society. So we must all try to be Charlie, not just today but every day.” And do it for its own sake not for any societal reward. “Political cartooning in the United States gets no respect,” Ted Rall wrote in his column at the Los Angeles Times. “I was thinking about that this morning when I heard NPR's Eleanor Beardsley call Charlie Hebdo ‘gross’ and ‘in poor taste.’ (I should certainly hope so! If it's in good taste, it ain't funny.) It was a hell of a thing to say, not to mention not true, while the bodies of dead journalists were still warm. But these were cartoonists, and therefore unworthy of the same level of restraint that a similar event at, say, The Onion— which mainly runs words— would merit. “But no matter,” Rall went on. “Political cartooning may not pay well, or often at all, and media elites can ignore it all they want. (Hey book critics: graphic novels exist!) But it matters. Almost enough to die for.” Ironically, the Paris massacre and outraged reactions to it attest to the power of cartoons while in the U.S., editorial cartoonists are an endangered species. Newspaper editorials condemned the attack as an unabashed assault on freedom generally and freedom of the press particularly and proclaimed solidarity with Charlie Hebdo, extolling the power of cartooning, but continued to lay off their full-time editorial cartoonists—the latest, even as the news of Charlie Hedbo swirled, is Chan Lowe at the Sun Sentinnel, laid off after 30 years. The ranks of full-time staff editoonists in the U.S. have thinned dramatically: down to 50 from 102 in May 2008. At the Denver Post (the daily newspaper where I live), the lead editorial on the day after the tragedy at Charlie Hebdo’s spoke of cartoonist/editor Charbonnier and his cartooning and journalistic colleagues as producing “brash, biting, provocative, sometimes juvenile and offensive” material. “But it was also in the proud tradition of the brutally satirical and outrageous journalism that is the birthright of everyone who lives in a free society. ... They died as martyrs for free speech and Western values.” But for all the indignation and pride in this lip service paid to journalists and cartoonists, the Denver Post hasn’t replaced its full-time staff editoonist Mike Keefe since he retired in November 2011. And although the paper runs a daily selection of editorial cartoons on its website, none appear regularly in print except in the Sunday edition. Recognizing this glaring incongruity almost as soon as the gunsmoke faded at Charlie Hebdo’s, Signe Wilkinson, editoonist at the Philadelphia Daily News, began stumping for an AAEC campaign to— HIRE A CARTOONIST! “The Charlie Hebdo attacks are, in their own perverse way, an affirmation of our power,” she wrote on the AAEC-List. “If American newspapers want to show solidarity with Charlie, they should hire cartoonist or at least run more cartoons. There are plenty of us on both sides of the political aisle from which to choose.” She even offered a slogan for the campaign: “You, too, can boost your sagging influence by hiring a cartoonist, attracting death threats, and occasionally being massacred all of which will attract attention you never dreamed could be yours!”

***** In 2005, the Los Angeles Times laid off its editorial cartoonist, Michael Ramirez. Aimed at reducing expenses in order to improve the paper’s bottom line, it was a purely business decision. In a triumph of irony over budget, Ramirez was promptly hired by Investor’s Business Daily, which, we assume, was also guided by business considerations about the kind of investments to make. Long live satire—standing upright on its feet, head high, loud mouth open, pencil aloft in proud defiance. Je suis Charlie!

Sources. Although I’ve credited sources at various intervals, I also quoted verbatim some of them, sometimes without credit. This quoted material is usually of the mundane, ordinary sort of factual recitation, no flights of stylistic brilliance. For all such information, I am grateful to the Associated Press and the online reports of Wall Street Journal, Christian Science Monitor, New York Times, Washington Post (and its ComicRiffs), Reuters, CNN, ABC, NBC plus print media, Denver Post, The Week, and Time.

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |