|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

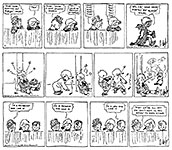

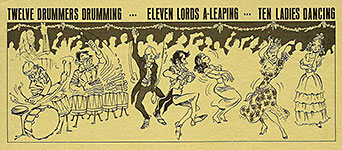

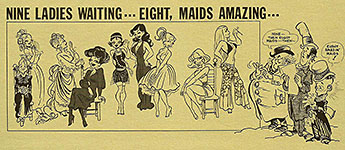

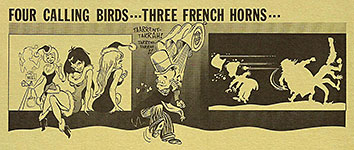

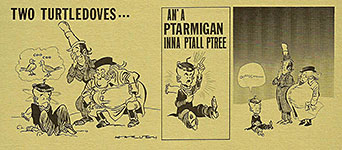

Opus 334: The Anyule Xmas List Edition (December 27, 2014)—and, as usual, too late to be of any practical use as a guide for spouses looking for a last-minute Christmas gift for their other half. We aim for this purpose every year, but we’re always just a trifle too late, arriving, alas, only a couple days before the holiday. This year, we have a Monster Roster of some sixteen reviews (including four graphic novels) plus a list of 43 new scholarly tomes, but we’re later than ever. Still, not too late, perhaps, for you to use the list yourself as a guide for ways to spend the money your Favorite Aunt Louise sent you for Christmas. Arriving between Christmas and New Year’s Day, this opus falls handily into the fabled Twelve Days of Christmas time slot—the fortnight between December 25 and January 5, Epiphany— and so instead of accompanying this posting with the usual wish for Merry Christmas, I’ve unearthed an Antique Artifact from the Happy Harv Archives that precedes that customary wish with a rehearsal of the song that celebrates the period. Starring in this ancient effort is my comic strip character, the little hobo Threadbare, and his mentor Fiddlefoot (the tall guy), accompanied by a pudgy seasonal coachman/caroller without a name. Let the fun commence.

In the spirit of the season, we have omitted our usual review of editorial cartoons because they typically revel the machinations of our government at its most rancorous; instead, we offer a selection of good-humored gag cartoons. And those book reviews I mentioned; see the listing below. Before we get to them, however—as is our usual practice—we begin by acknowledging and correcting an error in our last outing, Opus 333. CORRECTION. When citing the relative weights of Darren Wilson, the white Ferguson police officer who shot and killed black teenager Michael Brown, I got it wrong. I said Wilson weighed 120 pounds; Brown, 190. That’s about 100 pounds off. Wilson weighs about 220 pounds; Brown, 292. Wilson is 6-foot-2; Brown, 6-foot-4. (Or both are 6-foot-4; accounts vary.) Wilson is no skinny guy, but even at his dimension, a 292-pound angry kid had to look threatening if he was comin’ at him. My son-in-law is 6-foot-4 and says he weighs about 240 pounds; I’m 5-foot-11 and weigh 190 pounds, but he looks like a giant to me. And now, onward to Opus 334. Here’s what’s here, in order by department—:

NOUS R US Breyfogle Stroke All-New Archie Jack Davis Retires Significance of Zap Comix

Schulz’s Peanuts and Wilson’s Nuts

EDITOONERY Gag Cartoons

RANCID RAVES GALLERY: ABOUT FACE How the Happy Harv Was Censored

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Peeing, Smoking, and Sex in the Funnies Plus Word Play and Awful WuMo

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews of—: Vip’s Christmas Cookie Sprinkle Snitcher The Art of Robert E. McGinnis Frank Robbins’ Johnny Hazard —plus the end of the War in Caniff’s Terry & Cranes Buz Sawyer Shorter Xmas List: 43 Scholarly Books on Comics Death, Disability and the Superhero in the Silver Age and Beyond Alex Toth’s Zorro Classic Phantom Lady (not by Matt Baker it seems) Matt Baker’s Canteen Kate, 2 different volumes of it Bob Powell’s Cave Girl Sheena Queen of the Jungle The Alluring Art of Margaret Brundage, Queen of Pulp Pin-up Art

BOOK REVIEWS Long Review of—: Percy Crosby’s Skippy

LONG FORM PAGINATED CARTOON STRIPS Graphic Novels Reviewed—: Silent Partner Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? Woman Rebel: the Margaret Sanger Story The Beats: A Graphic History

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Deadpool The Wake Starlight Ms. Marvel Tuki Chaykin’s Satellite Sam Chaykin’s The Shadow: Midnight in Moscow

Those Who Passed Through in 2014

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

Fundraiser for Breyfogle Comic artist Norm Breyfogle, 54, suffered a stroke last month, and after a week in the ICU he was discharged to a nursing home. His left side (he’s left handed) was affected and he will require daily therapy to try to bring back his ability to function on that side. Family members have organized an online fundraiser for his expenses. Breyfogle had no medical insurance, has major hospital bills, and faces the cost of the nursing home as well. The fundraising goal is $200,000. Breyfogle is best known for his runs on the Batman character in Detective Comics, Batman, and Shadow of the Bat in the late 80s and early 90s, and the recent digital-first title Batman Beyond.

THE ALL-NEW ARCHIE It had to happen. The signs and portents have been gathering on the horizon for the last several years. Archie, the iconic American teenager for generations of funnybook readers, is getting a major make-over. The excuse, partly, is that the new Archie will help celebrate Archie Comics’ 75th anniversary (it began as MLJ in 1939). But publisher and co-CEO Jon Goldwater has been quietly—and often not so quietly—brewing changes ever since he ascended to the Archie Comics throne in 1999, following the death of his father, John L. Goldwater, one of the founders of the company. (For the biography of Goldwater pere and the history of Archie’s creation, see Harv’s Hindsight for the summer of 2001.) “I found Archie to be dusty, irrelevant and watered-down,” Goldwater said of his first impression upon taking his seat at his father’s erstwhile desk. Talking to Gregg Vigliotti at the New York Times, Goldwater added: “It has taken me a while to really wrap my hands around where we are as a brand.” The wrapping (or unwrapping) began with Archie marrying both Veronica and Betty, an exciting “dream” sequence that evolved into an alternate universe with a 37-issue run of Life with Archie, in which the Riverdale Redhead is married to one in the first part of the comic book; to the other, in the last part. Then, to end the series, Archie was killed, sacrificing himself to save the local congressman, Kevin Keller, who showed up a couple years ago as Archie Comics’ first openly gay character. And as if that wasn’t revolutionary enough, the publisher launched Afterlife with Archie in which the Riverdale gang turns into zombies. And finally, the most recent evolution, Sabrina the happy teenage witch of yore is now having realistically rendered chilling adventures as a real witch. All these adjustments have paid off. According to the company, direct market sales of Archie titles have increased 226 percent; bookstore sales, 736 percent. So

it can’t come as any surprise that now, after 662 issues dating back to 1942,

Archie will start over with a brand new No.1 in early 2015. And with the fresh

numbering, the characters acquire fresh new appearances by Fiona Staples,

whose frisky line gives the cast an authentic-looking adolescent aura. The new Archie books will be written by Mark Waid, who promised a more modern take on the characters. "Over the years, some of the sharp edges have been sanded off," he told the Times. "They are kids, and they should act as kids." But Goldwater promised that the title would retain its "lighthearted and family-friendly tone,” he said, “but we have to do it in the present times, and that forces us to change. These changes are crucial to keep the brand relevant and vibrant.” With artist Staples, the Archie reboot will have a visual identity far from the classic Archie house style, and with Waid, a more modern storytelling sensibility—together intending to reclaim an edgier sense of humor found in Archie's early appearances. Staples is on board to draw the title for at least the first three issues. After that? Well, Archie Comics has become the official House of Surprises, so who knows? Not content with a mere makeover of an American icon, Goldwater has even bigger ideas for Archie Comics, including revitalizing the Red Circle line of superhero comics under the heading Dark Circle Comics, plus a movie, an animated tv series and theme park rides. “I want us to be a global sensation, to be as big as Marvel and DC,” he said. “Other publishers have superheroes, but no one has Archie.”

SHREDS & PATCHES Eddie Campbell says he’s working on a book about San Francisco sports cartoonists, who, like Bud Fisher and Rube Goldberg, littered the landscape of the City by the Bay in the early years of the 20th century; he says he’s finished the first draft at 70,000. “I’m currently restoring old pictures,” he told Chris Arrant at robot6.comicbookresources.com. “It’s full of drama and odd twists and turns. There are race riots and somebody being shot in the head. This is no dusty academic tome.”... Parade, the weekly newspaper supplemental magazine, ran cartoons in the first two December issues, then left them out of the Christmas edition. ...

ANOTHER ICON CHANGETH From Wired Jack Davis, the legendary EC artist, Mad cartoonist, magazine illustrator and movie poster artist, is finally hanging up his pencils. It’s not that the iconic 90-year-old cartoonist can’t draw anymore—he just can’t meet his own standards. “I’m not satisfied with the work,” Davis says by phone from his rural Georgia home. “I can still draw, but I just can’t draw like I used to.” Davis has probably spent more time in America’s living rooms than anyone. Mad was a million-seller when Davis was on the mag, and when he was doing TV Guide covers in the 1970s, the publication boasted a circulation of over 20 million. Yet, Davis is largely unaware of his massive cultural significance. “I never really thought about that, but I guess I’m very blessed,” he says. “I’ve been very lucky.” But his luck paled in comparison to his skill. Davis started his career in 1936, when he was only 12; he won $1 as part of a national art contest and saw his work published in Tip Top Comics No.9. While still a teen, his cartoons were published in The Yellow Jacket, a humor magazine at Georgia Tech University, where his uncle was a professor. After a stint in the military, Davis caught on with EC Comics in 1950, where he was part of the artistic wave that revolutionized comics with titles like Tales from the Crypt, Two-Fisted Tales, and Mad. Whereas Norman Rockwell’s images represented Americana of the 1940s and ’50s with his Boy Scouts and pigtailed girls, Davis’ work epitomized the sixties and seventies—the smirking, sardonic face of the emerging counterculture. By the time the Beats and the Hippies (who came of age reading Davis cartoons) took over, he was doing movie posters for Woody Allen’s Bananas, The Long Goodbye, American Graffiti, and others. “Jack Davis is probably the most versatile artist ever to work the worlds of comic books, illustration, or movie poster art,” Scott Dunbier, a former art dealer and current director of special projects at comic book publisher IDW. “He can work in a humorous style or deadly serious style, historical or modern, anything. His work transcends that of almost any other cartoonist.” But Davis is done producing new work. “I’m just gonna sit on the porch and watch the river go by,” Davis says. “And maybe go fishing once in a while.”

ZAPPED ON THE CUSP OF MODERN COMICS Interviewed by Dan Nadel about the new Fantagraphics tome, The Complete Zap, publisher Gary Groth said he saw Zap as a turning point in the history of comics: “It wasn’t just Zap as a model, but the entire underground comix publishing ethos, of which Zap was probably the most prominent example. For the first time in the history of comics, there was a community, a movement, a collective —however you want to characterize it— of artists who took it for granted that they would own their own work, function as autonomous creative artists, and wrote and drew comix as a form of personal expression. And there were publishers who sprung up who instinctively honored this principle (Last Gasp, Rip-Off, Print Mint).” He continued: “It’s important to know that it’s quite probable that there wouldn’t be literary graphic novels today if it weren’t for the artistic terrain the Zap artists and the other underground cartoonists pioneered. This is the first time in the history of comic books that there was a critical mass of artists who insisted on their work being an expression of themselves — their sensibilities, values, and ideals. Every independent cartoonist today who’s doing work of great personal meaning owes a debt of gratitude to them for breaking this ground. “God knows, there were vast numbers of awful underground comics written and drawn by kids who were inspired by Crumb or Wilson or Shelton but who didn’t have the talent or commitment to pull it off, and published by publishers who were not discriminatory and were cashing in. But, the best work done between, say, ’67 and ’75, stands the test of time, and the artists in Zap were among the best cartoonists to come out of the underground scene. There were other important artists, of course (Bill Griffith, Jack Jackson, Art Spiegelman, Kim Deitch, Greg Irons, Vaughn Bode, et al.), but every artist in Zap was a devoted craftsman, stylistically unique, with a distinct point of view. Zap was a creature of its time, but the artists never flagged, and continued doing outstanding work throughout the run of the title — including in the last, 16th issue, that’s published in the Complete Zap.” He went on: “Zap was obviously part of the sixties counter-cultural zeitgeist —it couldn’t have happened without the larger cultural shift that it epitomized— but I tend to think the whole underground comix revolution was too singular to compare tidily with the stylistic and attitudinal shifts in the other arts in the sixties (and seventies). ... [I]n terms of visual art, I don’t see much connection to other artists emerging in the sixties. Surely the Zap artists had little in common with (and I bet most were even fundamentally opposed to) Warhol (who showed his first comic strip painting in 1960) or Litchenstein (who did his first comic strip painting in 1961) or Claus Oldenberg or Gerhard Richter or Ed Ruscha, whose ascendancy parallels the underground artists. ... And maybe Rock was as huge a break from previous pop music as Zap was from previous industrial comics production, but the explosion of Rock seems more like a continuation or culmination of musical trends, whereas underground comix was a decisive break from the past — a deliberate, incendiary reaction to the censored blandness of comics over the previous 15 years. So it seems to me that the Zap crew was somehow part of but apart from their countercultural brethren in the other arts.” By the time of this interview—roughly December 3—The Complete Zap was sold out, non-returnable, to retailers and there was no stock left in the usual Fantagraphics distribution channels. Groth allowed however that a less expensive printing might eventually be available.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS T-Shirts for Our Times Earth without Art is just “eh.” Before you judge me, make sure that you are perfect. I wonder if clouds ever look down on us and say, “Hey, look! That one is shaped like an idiot!” I believe in a balanced diet—a glass of wine in both hands. I’m dreaming of a white Christmas—but if the white runs out, I’ll drink the red. If guns kill people, then pencils misspell words, cars make people drive drunk, and spoons make people fat.

PEANUTS AND ACTUAL CHILDHOOD Gahan Wilson did a comic strip for National Lampoon. The strip was entitled Nuts. The title is inspired by Charles Schulz’s iconic strip. In his book I Only Read It For the Cartoons about some New Yorker cartoonists, Richard Gehr says: “Wilson admires and appreciates Schulz’s work, but he considers Peanuts a deceptively anodyne depiction of childhood.” Gehr goes on to quote Wilson: “I always respected what Charles Schulz did—which was religious teaching. He was doing a kind of medieval religious pageant. His strips were little moral fables. It’s fine and dandy, but it has nothing to do with children, and that’s all there is to that. But he did exactly what he set out to do, and it’s quite extraordinary stuff. It did piss me off that he was pretending it was about cildren and it wasn’t. “Childhood,” Wilson went on, “is a terrifying world. The little critters are so alive and so perceptive. They’re all scared to death but so delighted when something works out. Children are intensely alive and complicated. The thing that made me angry at Schulz is that he sentimentalizes the idea of childhood, which has really done a lot of harm.” In

his Nuts, Wilson drew everything “down” to scale. “It’s like the kid is

being crushed and confined in this box. The frame is kid-sized, and you only

see parts of the huge people and world that surround him. That’s all a kid

apprehends: giant projections in his immediate vicinity and everything else far

away. Doors “So Nuts was saying, ‘This is the nitty-gritty, folks. This is what it’s like being a little kid.” To devise adventures for his kid, Wilson just “racked” his brain to remember things that happened to him as a kid that were so awful. “The Kid is trying to figure it out. The Kid never had any name at all, also very much on purpose. I didn’t want to nail him down.” Wilson’s Kid was every kid, terrified of the looming world around him. Here are a couple of his adventures.

MORE T-SHIRT WISDOM If God wanted me to touch my toes, He would’ve put them on my knees. Fight Organized Crime: Vote Them Out! It doesn’t matter if the glass is half empty or half full—there is clearly room for more wine. Don’t take life too seriously: no one gets out alive. Despite the high cost of living, it continues to be very popular. If all is not lost, where is it?

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy NO EDITOONS THIS TIME, kimo sabe. In an effort to promulgate good tidings and cheer in the spirit of the season, we focus herewith on another brand of single-panel cartooning, the strictly humorous kind (with only occasional sidelong glances at social customs and mores that richly deserve ridicule).

In our first specimen, we have a couple of Christmassy efforts, after which, we continue in a Biblical mode with a glimpse of a heretofore unreported incident about Noah and the Flood. The article is from Faux News (or some similar title; I’m not sure I have that right). Finally, a sample of Dan Piraro’s Bizarro, of which we have more in the next visual aid just at its elbow. First, several superhero gags, which Piraro loves to do, and then a couple clown jokes. The first one comes close to being a peeing joke, one of the verboten topics of yesteryear but no more. Next, we have a cartoon plug for Funny Times, a monthly newspaper that publishes cartoons and humorous columns.

The description of hippies was too good to let go. Being formerly one, I recognize the breed fondly. And the BerkeleyNews.com strip was also a gem, taking Van Gogh a logical step further. I looked at the site, expecting more off-the-wall comedy, but, alas, this one is the best I saw. Back to Piraro for one more gag, another like the Van Gogh joke, a logical step gone awry. In the adjacent exhibit, three cartoons by Flash Rosenberg, culled, I think, from the Lilith site, “Independent Jewish and Frankly Feminist.” Rosenberg’s elegantly frilly style intrigued me—turns every cartoon commentary into an elaborate design. Unusual. Then we have a sampling of Cornered by Mike Baldwin.

His cartoons are frequently verbal gags, but when he deploys pictures as punchlines (as he does in three of these), he’s a good laugh. The other two are more of the skewed perspective comedy breed, also usually good for a laugh. In the same spirit on the next exhibit, here’s Mick Stevens on “fast food,” then cartoons by two of my favorite cartooning stylists— Bob Vojtko (“voit-ko”), a grocer who freelances cartoons in the off hours, and Randy Glasbergen, champion nose-cartooner. Vojtko’s spare style, usually unrelieved by any solid blacks or gray tones, is stunning in its simplicity. Finally, we have an unusual appearance by editoonist Mike Luckovich in The New Yorker in December 2008 with a comment on the a-borning financial crisis that led immediately to the Great Recession and, simultaneously, on the extortion tactic of the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm. Hence, a cartoon that continues, inexorably, to be apt to the day. (Sorry: a little unseasonal political rancor just escaped.) Merry Christmas indeed.

READ AND RELISH Some sheerly perceptive person said that Kim Kardashian’s oiled naked booty looked like glazed Krispy Kremes. Right.

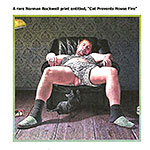

RANCID RAVES GALLERY: ABOUT FACE Pictures Without Too Many Words AS SOME OF YOU

ALERT READERS KNOW, I’ve been posting to my Facebook page for a couple years

now. Some of the postings have been recycled here; but mostly, I put up on

Facebook some of my old cartoons and various other images that inspire my

comment. One of them was REMOVED from the page earlier this

month; I’ve posted it near here. Despite the inherent fetters, I understand the need for something like “community standards” at a site like Facebook; I’m not saying The Face ought to dispense with them. But anything approaching “community standards” is inherently highly subjective and ought, therefore, to result in only temporary chastisement. My Facebook page was reactivated after I’d been stood in the corner for 3-4 days. This isn’t the first time in my cartooning life that I’ve been censored. But it’s the first time I’ve been censored for a picture I didn’t produce myself. It seems, now that I reflect upon it, that I’ve gotten into hot water in nearly every venue I cartooned in, beginning my freshman year in college when that year’s second issue of the campus humor magazine, The Flatiron, resulted in the publication being banned forever. The

reason given for banning the magazine was that it over-emphasized “sex and

alcohol.” My cartoons weren’t mentioned at all, but, beginning with the cover

of the magazine (displayed near here), most of the content in that issue

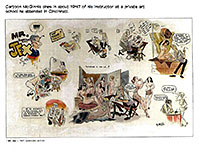

consisted of my cartoons. Another of my cartooning sins was committed when I was editing the base newspaper at the Navy’s Supply Corps School in Athens, Georgia, in 1960. I also produced a comic strip for the paper, and in one of them, I used the word “bitching” as slang for “complaining.”The base commander directed that this issue of the newspaper not be sent off base in the exchange program with other Navy base newspapers thereby effectively “censoring” it. “Bitching” was somehow a nasty word. Who knew? The

strip was entitled Beau Sandy, an approximation of the buzz word for

Bureau of Supplies and Accounts, BUSANDA, the branch of the Navy under which

Supply Corps officers like me operated. The eponymous Beau Sandy was a would-be

lothario; he is the character pouring coffee down his throat in the first

panel. Nonfat is the little guy with the strange hairdo. Four-way B. The second strip perhaps explains some of the first one. The commander of the base had a large German shepherd that roamed the campus, sometimes after dark. And job of the JOOD (junior officer of the day) was to patrol the premises a couple times a night to catch malefactors (if any) in the act. So the JOOD might very well run into the captain’s dog, as, in this case, Wild Bill evidently did. That’s a caricature of the captain walking the dog.

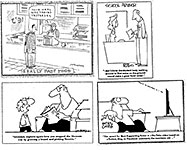

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping CONTINUING,

with watch-dog ferocity, our monitoring of contemporary comic strips to see

what sins they’ve been committing lately, we come upon two in which the jokes

turn on our recognizing that peeing is funny. And in the next strip in our visual aid, Stephan Pastis’s Pearls Before Swine uses a common euphemism for peeing—whizzing. Again, not in those fond days of yesteryear. Below that, we have another of Peters’ strips, this one without Grimm or Mother Goose (as is sometimes Peters’ wont). The gag here is about sex, another of the verboten topics in ancient times. To get the joke, you have to remember an old Mae West quip: encountering a likely-looking male, she says, “Is that a carrot in your pocket or are you just happy to see me?” And Peters got away with it. Ahhh, these modern times. Next, we encounter another of those completely baffling WuMo strips. What’s the joke here? At the far left, there’s a picture of a tiny fish smoking a cigarette. Is that what strikes fear in the hearts of the larger fish? Smoking a cigarette? Does smoking a cigarette signal that the smoker as a tough guy? So it seems here. Or am I missing something? (Not unheard of.) (Smoking is, apparently, a great New Fear, responsible, I ween, for my being banished from Facebook for posting a mock Norman Rockwell picture in which a man was depicted falling asleep while smoking a cigarette. The anti-smoking faction responded, as is their wont, fiercely, and the Facebook door slammed in my face.) The next WuMo down the page is a little better. At least, the core of the comedy is evident. It seems the owner of the vehicle emerging from the car wash didn’t read the car’s washing instructions, and as a result, his car shrunk. Okay: that’s vaguely funny. I get that one. Feeble but funny. But at the right, Bill Whitehead’s Free Range leaves me cold. The whole joke is that in Roman times the number 27 was written XXVII? That’s it? That’s the hysterical comedy? Not very. Another WuMo, if you ask me. But then, you didn’t, did you? Finally, to rise again to the top—at the right, Marc Hamilton’s Dennis the Menace makes a good case for comic strips being in newspapers. What ever happened to that profound rationale?

HEREWITH a few

word games plus a couple things possible only in comics. More word play in Mother Goose and Grimm. This time, about prepositions. In a famous anecdote, Winston Churchill was once edited by a conscientious soul who changed one of Winnie’s sentences to avoid ending it with a preposition. Churchill responded with a classic, saying: “That is an imposition up with which I will not put.” And then there’s the somewhat less famous story whose last sentence ends with five prepositions. A kid was in bed, preparing to fall asleep but asked his father to read to him first. The dutiful father went downstairs to get a book and brought it up to his son’s room, and when the kid saw the book, he expressed dissatisfaction: “Awww—why’d you bring that book I don’t want to be read to out of up for?” In Close to Home, John McPherson engineers another gag that can most easily be accomplished in a cartoon. And then we have another lame specimen of WuMo. Those appear to be socks on the ledge, and the empty drawer the guy inside is holding would be, then, a sock drawer. So the socks all escaped the sock drawer. Soon they’ll be, as one says, “free.” The strip seems to be an explanation for why your sock drawer is always missing the requisite socks. What’s funny about that? Is the comedy of this strip just sort of whimsical? Is that all? Probably. I’ve been following the strip for weeks now, and it never gets much better

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv.

Plastic in the Oceans From the Washington Post: Thanks to humans, there are more than 5 trillion pieces of plastic weighing more that 250,000 tons, floating in water around the world. With global population of about 7.2 billion, that’s nearly 700 pieces per person. ... Plastic gets into oceans by being blown there (bags) or floating there via rivers emptying into the oceans. ... Plastic then breaks into smaller pieces and circulates, traveling in five major ocean gyres, which spiral in large circles, winding the trash inward. ... The ecological consequences are severe. Marine animals might not only get entangled in plastic but might ingest this long-lasting material, thinking it is food. That’s not only bad for fish, it could ultimately be bad for humans who consume fish that have consumed plastic. ... It is becoming increasingly imperative that the use of plastics include a 100 percent recovery plan—or have a 100 percent environmentally harmlessness in choice of material.

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews and Proclamations of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we do here, starting with—:

The Christmas Cookie Sprinkle Snitcher By Robert Kraus, illustrated by Vip

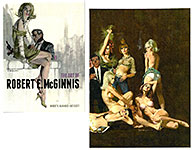

The Art of Robert E. McGinnis By McGinnis with Minimal Text by Art Scott 176 giant 9x12-inch pages, gorgeous color; 2014 Titan Books hardcover, $34.95 NO ONE READING THIS needs to be told that Robert McGinnis is the premier painter of those sultry sleek beautiful, often sexily clad women on the covers of detective paperbacks—Mike Shayne, Carter Brown, Perry Mason, and Shell Scott. Starting in 1958, he has painted more than 1,000 such covers, his style, as Art Scott says, defining the look of paperback books. But if you somehow missed seeing any of this species, I’ve scattered a few near here.

Many of the images in this happily-sized volume are reproduced from original art, including a few preliminary pencil sketches and color roughs. Surprisingly, McGinnis turned down a gig at Playboy. After the death of Alberto Vargas in 1982, Hugh Hefner approached McGinnis to take over the magazine’s pin-up page. But McGinnis wasn’t interested, Scott tells us, “in part because he felt the magazine’s attitude toward women was ‘immature, adolescent.’ Also, he wasn’t in sympathy with Playboy’s concept of ideal feminine beauty either, as expressed by their centerfold playmates, which he said were ‘too zaftig, too tan, too young.’” McGinnis women are not Playboy voluptuous: they are slender and long legged, but otherwise normally proportioned. And achingly beautiful. Surprisingly, McGinnis also illustrated stories in Good Housekeeping as well as in men’s magazines. And the periodical for which he did the most work is Guideposts, a small format monthly magazine of inspirational stories. Another

surprise: McGinnis is an accomplished cartoonist and caricaturist. Right after

high school, he went to work for Disney, a promising career in animation cut

short by his service in the Merchant Marine during World War II. In excerpts from an interview with Scott in January 2014, McGinnis calls illustrator Howard Pyle “a giant—I can’t get near him.” But Andrew Wyeth is “without equal in history.” McGinnis

is still alive at 88 and painting—mostly, now, for the joy of self- And if you don’t get enough McGinnis in the volume at hand, try Tapestry: The Paintings of Robert E. McGinnis (Underwood Books, 2000) and The Paperback Covers of Robert McGinnis (Pond Books, 2001). But the reproduction in The Art of is the best of the lot.

Frank Robbins’ Johnny Hazard Volume One: The Newspaper Dailies, 1944-1946 By Frank Robbins; Introduction (one page) by Daniel Herman 240 6x10-inch landscape pages, b/w; 2011 Hermes Press hardcover, $49.99 ROBBINS WAS THE MOST FACILE of those who drew in the Sickles-Caniff chiaroscuro manner. He also burned up story material faster than anyone else working in the continuity strip genre, often jamming two cliff-hangers into a single daily release. Robbins started his comic strip career on the iconic aviator strip, Scorchy Smith, which launched March 17, 1930, capitalizing on the fame of Charles Lindbergh, who had made his spectacular non-stop solo crossing of the Atlantic, May 20-21, 1927. Robbins was the fifth artist on Scorchy, following the creator John Terry, who did it until he became too ill with tuberculosis to continue; Noel Sickles took it over December 4, 1933, thinking he would do it only until Terry recovered. But Terry died, and Sickles inherited the strip and started signing it on April 2, 1934; he also began changing the drawing style, moving from Terry’s hayey pen scratching to the shadowy manner that Sickles’ studio-mate, Milton Caniff, would emulate and make famous in Terry and the Pirates. Sickles did Scorchy until October 24, 1936, then Bert Christman followed until July 30, 1938; then Howell Dodd, August 1, 1938-May 20, 1939. Robbins left March 11, 1944 to do Johnny Hazard. In his admirably succinct Introduction, Herman says Robbins had been offered Secret Agent X-9 but chose to do his own strip rather than continue another cartoonist’s creation. Another aviator strip with a protagonist in the army air corps like Caniff’s Terry, Johnny Hazard debuted June 5, 1944, with Hazard and a couple of buddies at a Nazi air base in Germany on “the last leg of their escape.” After just one adventure in the European skies, Hazard and his squadron are transferred on September 11 to the Far Eastern Theater, where the strip remained until the end of the war. Hazard looks somewhat like Scorchy—with short, black curly hair, graying at the temples (a sign of maturity in the otherwise sometimes foolhardy Hazard). But Robbins was also inspired by a minor character in Caniff’s Terry. Caniff’s Dude Hennick was based upon a college friend of Caniff’s, Frank “Dude” Higgs, who had spent the War in the vicinity of Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers in southwest China. Robbins borrowed Higgs’ eyebrows via Hennick. Said

Caniff of his friend and inspiration Higgs: “He had eyebrows that went straight

across his forehead. In China, that’s a sign of great Fu Manchu kind of evil.

Higgs loved it. He’d glower at the Chinese and get ’em all to do things. He had

a ball.” And

Robbins’ borrowings did not end at Hazard’s eyebrows. In addition to the

Sickles-Caniff drawing manner, Robbins appropriated an even more conspicuous

element—Burma, the blonde bombshell bad girl, who, with the Dragon Lady, was

one of Caniff’s signal creations during his Terry years. In Hazard’s

first adventure, he meets a stunning blonde photojournalist named Brandy (like

Burma, she has only one name, and it begins with a B). As the strips in the book at hand show, in the first years of Johnny Hazard, Brandy is on camera almost as much as her beau: the continuity sometimes focuses on her, with Hazard off on the sidelines for a week or so. Every page of the volume presents two daily strips, a generous allotment of space that showcases Robbins’ crisp, bold chiaroscuro manner. Reproduction, probably from pristine syndicate proofs, is clean and clear, a collector’s dream. The first two years of Johnny Hazard end with the end of World War II, and the last strips in this volume reveal a hazard other than Johnny. The war in the Pacific ended quicker than anyone anticipated. When the U.S. dropped two atomic bombs on Japan—first on Hiroshima on August 6; then on Nagasaki on August 9—the unprecedented massive destruction persuaded the Japanese Emperor to surrender almost at once. The abrupt ending surprised everyone. The war in Europe had been over since May, and everyone had been gearing up—logistically and psychologically—to invade Japan. Few knew about the atom bomb. But now there would be no invasion of the island homeland.

ADVENTURE STRIP CARTOONISTS whose strips were set in the war were, like everyone else, caught unaware. Unlike everyone else, their unawareness had to play out in public. As everyone reading this knows, syndicated comic strips are prepared 4-6 weeks in advance of their publication dates; Sundays, up to 10 weeks before publication. And when Japan’s surrender was announced on August 14, the comic strip armies of Caniff and Robbins and Roy Crane were still at war. And because the strips’ continuities were well into the pipeline for distribution, they’d all be at war for several more weeks until the cartoonists got up-to-date strips into that pipeline. Caniff’s characters were on an island, not far from the hostilities but, for the time being, not engaged in them. Through July 1945, Caniff had watched reports of daily saturation bombing over Japan. It didn’t take a military genius to know that the home islands of the Empire were being softened up for an invasion. The cartoonist continued to play for time, prolonging the sojourn on the island for Terry and his buddy, Hotshot Charlie. Caniff involved them in a plan to expose a Japanese spy in their midst, a plot sufficiently detached from military operations to be impervious to the vicissitudes of the actual War, and he prepared for the return of Terry’s mentor, Flip Corkin. In writing the Sunday strips leading up to Flip’s arrival on the island, Caniff was purposefully vague about why he was coming there. If the invasion of Japan were to take a long time (as everyone expected it would), Caniff planned to use his island airfield in conjunction with the airborne operation. Corkin could be there as the advance man. Or (as it turned out) he could be on the island to mop up when the fighting was over. With both daily and Sunday strips, Caniff delayed deliveries to his syndicate as long as he dared, falling deliberately behind in his deadlines in order to keep his published story close to current developments. He was waiting specifically for the news that the long-awaited invasion of Japan had begun. That news never came. Instead, Japan surrendered. But Caniff was poised to make use of the news. By early August, his daily strip submissions were only two weeks ahead of their publication dates. Consequently, in the dailies for the week of August 27—the first strips sent in after the atom bomb fell on Hiroshima—he could have Hotshot make vague reference to “overshadowing events” taking place outside the island story, either invasion or surrender. In the week’s Saturday strip, Caniff guessed that the atom bomb would end the War: he led up to Corkin’s Sunday arrival by indicating a post-war policing operation was in the offing. Thus, the daily strips, drawn closer to current events, made the Sunday page, drawn weeks earlier, seem equally current: the more specific topicality of the former effectively filled in the blanks left in the latter’s generalities. In his next dailies for the week of September 3—the first strips Caniff drew after the announcement of Japan’s surrender—his marionettes talk about the end of the war and the forthcoming mopping up operation. Terry was again as current as the day’s headlines. Caniff accomplished the transition from war to peace so deftly that naive readers might be justified in assuming that the cartoonist plotted the War as well as the strip. The well-advertised tenacity of Japan’s militaristic die-hards provided more than one cartoonist with a handy explanation for the war’s apparent failure to end in their strips until several weeks after Japan had actually called it quits. Towards the end of the Johnny Hazard volume at hand, we can see how Robbins managed the time warp. Like Caniff, he must’ve been running behind his deadlines: he was able to allude to the war’s end in his release for August 31. In occupied China, his pilot hero is far away from the shooting war, and when, on August 31, Johnny runs into a fugitive Japanese general and the real War is over, Johnny makes a wry comment about “Nip old-outs” in China “who don’t know when to quit.” This sort of rhetorical slight of hand was a common enough explanation that Caniff a month later in Terry could joke about comic strips in which Japanese were still fighting because they were on remote islands where they hadn’t heard the war was over. Roy Crane wasn’t so lucky. He allowed himself and his Navy pilot protagonist to be caught center stage in his own full scale, all out Pacific War in Buz Sawyer at the very instant the curtain went up on peace. Like Caniff, Crane had watched the bombing of Japan in July. But unlike Caniff, Crane decided to plunge his hero into the very thick of the action. For Crane, who pursued realism and authenticity with the same passion as Caniff did, the consequences of this decision were excruciatingly embarrassing. On the day Americans concluded their street dance in celebration of Japan’s surrender, Buz is being briefed for a dawn strike at Tokyo. For the next agonizing week-and-a-half, Crane undoubtedly squirmed as his hero bombed “the sacred earth of Japan” and fought off the kamikazes that attacked his aircraft carrier. But Crane was also working with the shortest lead time he could engineer, so he was able to bring his strip out of its time warp the same week Terry emerged. In Buz Sawyer, the war ends as definitively on August 28 as it had on August 14 in real life. The ship’s squawk box screams the announcement: “This is official! Japan has surrendered! The War is over!” After the war, Hazard went on to become one of those footloose trouble-shooters for a variety of unnamed quasi-governmental agencies; the strip ended August 20, 1977. Hermes has already produced two more volumes in the reprint series.

Shorter Xmas List I assembled this list from a “Pop Culture Books” catalog manufactured by McFarland & Company, P.O. Box 611, Jefferson, NC 28640-0611; or you can order from the website, mcfarlandpub.com. I list here the title, author, and price; the catalog doesn’t say much more. All are paperbacks unless otherwise noted.

It Happens at Comic-Con: Ethnographic Essays on a Pop Culture Phenomenon, Ben Bolling and Matthew J. Smith, eds.; $35 The Ages of Wonder Womana: Essays on the Amazon Princess in Changing Times, Joseph J. Darowski, ed., $40 The Ages of the X-Men: Essays on the Children of the Atom in Changing Times, Joseph J. Darowski, ed., $40 Riddle Me This, Batman: Essays on the Universe of the Dark Knight, Kevin K. Durand and Mary K. Leigh, eds.; $40 Chester Gould: A Daughter’s Biography of the Creator of Dick Tracy, by Jean Gould, $25 Graphic Details: Jewish Women’s Confessional Comics in Essays and Interviews, Sarah Lightman, ed.; $49.95 Anti-Foreign Imagery in American Pulps and Comic Books, 1920-1960, by Nathan Vernon Madison, $40 American Toons In: A History of Television Animation, by David Perlmutter, $55 The Batman Filmography, 2nd Edition, by Mark S. Reinhart, $45 Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels: A Critical Approach, by Julia Round, $40 Arthurian Animation: A Study of Cartoon Camelots on Film and Television, by Michael N. Salda, $45 Graphic Novels and Comics in the Classroom: Essays on the Educational Power of Sequential Art, Garrye Kay Syma and Robrt G. Lweiner, eds.; $45 Souls of the Dark Knight: Batman as Mythic figure in Comics and Film, by Alex M. Wainer, $40 Tales of Superhuman Powers: 55 Traditional Stories from Around the World, by Csenge Virag Zalka, $29.95 Horror Comics in Black and White: A History and Catalog, 1964-2004, by Richard J. Arndt, $55 Mapping Smallville: Critical Essays on the Series and Its Characters, Cory Barker, Chris Ryan and Mye Wiatrowski, eds.; $40 Punch and Judy in 19th Century America: A History and Biographical Dictionary by Ryan Howard; $35 Comics as a Nexus of Cultures: Essays on the Interplay of Media, Disciplines and International Perspectives, Mark Berninger, Jochen Ecke, and Gideon Haberkorn, eds.; $39.95 Art in Anime: The Creative Quest as Theme and Metaphor, by Dan Cavallaro, $35 Sexual Ideology in the Words of Alan Moore, Todd A. Comer and Joseph Michael Sommers, eds.; $40 The Ages of Superman: Essays on the Man of Steel in Changing Times, Jim Daems, ed.; $40 War, Politics and Superheroes: Ethics and Propaganda in Comics and Film, by Marc DiPaolo, $45 Teaching Comics and Graphic Novels: Essays in Theory, Strategy and Practice, Lan Dong, ed.,; $45 Buffy Meets and Academy: Essays on the Episodes and Scripts as Texts, Kevin K. Durand, ed.; $35 Buffy and the Heroine’s Journey: Vampire Slayer as Feminine Chosen One, by Valerie Estelle Frankel, $35 Buffy in the Classroom: Essays on Teaching with the Vampire Slayer, Jodie A. Kreider and Meghan K. Winchell, eds.; $35 The 21st Century Superhero: Essays on Gender Genre and Globalization in Film, Richard J. Gray II and Betty Kaklamanidou, eds.; $75 Encyclopedia of Weird Westerns: Supernatural and Science Fiction Elements in Novels, Pulps, Comics, Films and Television by Paul Green, $25 Imagination and Meaning in Calvin and Hobbes, by Jamey Heit, $40 Crossing Boundaries in Graphic Narrative: Essays on Forms, Series and Genres, Jake Jakaitis and James F. Wurtz, eds.; $40 Super-History: Comic Book Superheroes and American Society by Jeffrey K. Johnson, $40 Classics Illustrated: A Cultural History by William B. Jones, Jr., $55 V for Vendetta as Cultural Pastiche: A Critical Study of the Graphic Novel and Film by James R. Keller, $35 The Flash Gordon Serials 1936-1940: Heavily Illustrated Guide, Roy Kinnard, Tony Crnkovich and R.J. Vitone, eds.; $35 Southeast Asian Cartoon Art: History, Trends and Problems, John A. Lent, ed.; $40 (Lent is the only name I recognize in this list; he’s been doing this sort of thing for as long as I have.) The Humanism of Doctor Who: A Critical Study in Science Fiction and Philosophy by David Layton, $40 The Doctor Who Franchise: American Influence, Fan Culture, and the Spinoffs by Lynnette Porter, $35 Doctor Who in Time and Space: Essays on Themes, Characters, History and Fandom, 1963-2012, Gillian I. Leitch, ed.; $45 Conan Meets the Academy: Multidisciplinary Essays on the Enduring Barbarian, Jonas Prida, ed., $35 Watchmen as Literature: A Critical Study of the Graphic Novel, by Sara J. Van Ness Learning from Mickey, Donald and Walt: Essays on Disney’s Edutainment Films, A. Bowdoin Van Riper, ed., $40 Comic Books and the Cold War, 1946-1962: Essays on Graphic Treatment of Communism, the Code and Social Concerns, Chris York and Rafiel York, eds.; $40 I’ve posted this list partly for Seasonal Reasons, as I mentioned at the beginning of this opus, but also as a gauge of the growth of academic interest in comics over the last decade or so. Judging from the encyclopedic subtitles on all of these works, they all appear to be of the scholarly ilk. The names of the authors are almost entirely unknown to me—which indicates, I suppose, how rapidly the field of comics scholarship has grown because I have thought, until now, that I keep up on such matters fairly religiously. Clearly, there’s a lot happening out there with me all unaware. My guess is that, upon closer inspection, the authors and editors of these tomes have all graduated from college within the last ten years and that the works themselves are remnants of PhD dissertations.

Death, Disability and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond By Jose Alaniz 276 6x9-inch pages, mostly text with a few b/w illos; 2014 University Press of Mississippi hardcover, $65 ANOTHER IN THE SEEMINGLY UNENDING flood of scholarly treatments of comics, the argument of this tome is suggested in the fragmentary notes I took upon scanning the introductory chapter and the book’s conclusion; to wit—: Superhero erases normal, mortal flesh in favor of quasi-fascist physical ideal of strength and control unbounded ... seemingly denying death and disability ... erotically potent but emotionally immature alter ego ... dual identity creates tension, disparity between dreams and achievements ... fantasies of dominance “veil a core castration angst” in the Oedipal drama—dread over powerlessness that forms a central tenet of the book. Costume is the obligatory identity marker: costume is the alchemical element of the transfiguration: one becomes a superhero when one dons the costume ... and the body helps: superior physiques signal superior beings ... this study examines Marvel, in particular, for its increasingly complex depiction of disability and death ... the personalities of Marvel heroes are not without flaw; they are disabled ... the Marvel heroes are “wounded,” hence, more real heroes ...their powers separate them from the rest of society and thus complicate their interpersonal dynamics, driving a wedge between the hero and his society and hence bringing him more misery than contentment and satisfaction. Alaniz claims to shed light on the structuring principle of the super-body and thus of the superhero genre itself ... that it comes about through an always-erased though always-implied disabled/dying/dead body ... Superheroism cannot co-exist with disability and death or dying ... The emerging complications of modern life (feminism, postwar uncertainties, aspirations of marginalized groups, questions of masculinity) made the disabled and dying figure a potent symbol for this transformative time. ... They strived to do right, regardless of their flaws, their disabilities. Still, a crisis in manhood lurked—brought on by the emerging feminism, rise of youth culture, stalemate in Korea and reverses in Vietnam (both proving grounds for manly behavior), civil rights marches—loss of belief in male adequacy ... The disabilities heighten a sense of realism but also threaten the notion of traditional male power, thus constituting a “direct assault on the white phallocratic order in the U.S. of this period.” While this line of thought seems to move in the direction indicated in the last statement, Alaniz’s argument spirals off in different fragmentary directions at the end. Although we cannot escape the threat to masculinity nor dread of death, superhero comics “become reflective objects that help us think about our own irreversible flow toward death” ... Moreover, “disability in the Silver Age is a crucial element of being a hero,” thus affirming the human worth of those with disabilies. But it also dehumanizes the disabled as represented in such villains as the Joker and the Green Goblin ... their mental instabilities make it easy in popular culture to pigeon-hole mental disability as so freakish as to justify locking up the mentally disabled. On yet another hand, disability in superheroes “signal the return of history—the return of story—to Superman’s flesh. If so, then I would say the trajectory of the superhero tracked in these pages casts into relief an aspiration. Not us aspiring to them. They aspiring to all our diversity, incompleteness and humdrum reality. An aspiration to the frail, the mortal, the interdependent, the human. To us.” And that’s where Alaniz leaves it.

Alex Toth’s Zorro: The Complete Dell Comics Adventures By Alex Toth; Introduction by Daniel Herman 240 7½x10-inch pages, color; 2013 Hermes Press hardcover, $49.99 TOTH WAS A PAST MASTER at storytelling in comics, and in this compilation, we see him operating under the most inhibiting of conditions—and yet still producing exemplary stories. His talent surmounted the obstacles. Following his 1956 discharge from military service (which he performed in Tokyo, editing the base newspaper and drawing a comic strip, The Adventures of Jon Fury in Japan), Toth went to work for Western, where he was soon producing the comic book version of Disney’s tv show, “Zorro,” which had debuted in October 1957. Toth’s assignment was to illustrate adaptations of the tv show’s scripts, light-hearted action frolics that pitted the handsome but seemingly ineffectual Don Diego de la Vega in his secret guise as the swash-buckling Zorro against fiendish California overlords whose agent, the paunchy soldier, Sergeant Garcia, served as both threat and comic relief. But Toth was unhappy working from adaptations, Herman tells us in the Introduction: “The show’s scripts had too much dialogue and not enough action. In order to tighten up the storytelling, he deleted unnecessary dialogue and cut redundant captions wherever possible, which did not go over well with the editor. When he was called on the carpet, in classic Tothesque indignation, he informed his boss, ‘Since you won’t control your writers’ use of superfluous copy and static dialogue, don’t expect anything outstanding from me anymore, because I won’t give it to you, not with those scripts and your bloody incompetence.’” Or, one supposes, words to that effect. Toth, by all reports, was a classic crank as well as a comics genius, but it’s still a strain to believe that he used exactly those words and still held his job at Western. In any case, with the Zorro stories in this volume as evidence, it’s clear that Toth was able to pare the prose and deploy the pictures to tell stories in ways that usually embody his storytelling standards. Usually but not always.

Herman quotes Toth about comics storytelling: “It’s a picture medium; let the pictures tell the story. Too much verbal exposition demonstrates a distrust of the viewer’s intelligence.” For Toth, Herman goes on, “comic books were just like a silent movie: the pictures were primary, only augmented by a necessary, not superfluous, use of text.” Although the Zorro stories do not show Toth at his refined and distilled best—which he soon became—they are nonetheless exemplary. And they are a pleasure in themselves. Herein Toth deploys a finer line than will distinguish his later work, and he feathers more, too. But the drawings are still a dramatic distillation of visual resources. Toth reportedly once said that during his early career, he spent creative energy putting visual detail into his drawings; then for the rest of his career, he studied how to take most of that out of the drawings without destroying their storytelling effectiveness.

The Classic Phantom Lady, Volume 2 By “Matt Baker”; Forewords by Jim Vadeboncoeur and Roy Thomas 312 7x10-inch pages, color; 2013 Roy Thomas Presents PSArtbooks slipcased hardcover, $69.99; paperback, $49.99 THE SECOND IN A PROPOSED 3-VOLUME project from PSArtbooks under Thomas’ watchful eye, this book reprints the Phantom Lady’s appearances from June 1948 through July 1955, dates that embrace her adventures as recorded in Fox Feature publications— Phantom Lady, Nos.18-23; All-Top Comics, Nos.8-17—and Ajax-Farrell Publications, Phantom Lady, Nos.1-4 and Wonder Boy, Nos.17 and 18. The first PSArtbooks volume in this series (reviewed here in Opus 320) reprinted the scantily-clad crime-fighter’s debut in Quality Comics books (Police Comics, Nos.1-23 and Feature Comics, Nos.69-71). This volume continues the project by ostensibly celebrating the work of the renowned good girl artist, Matt Baker, who began producing the iconic nearly naked Phantom Lady in the Fox books. Except that he didn’t. And that ain’t the only glitch in the cartwheel. A

red-faced Thomas introduces Vadeboncoeur, who claims, not without considerable

authority and reputation as a spotter of art styles (and therefore of artists)

in unsigned work of the Golden Age, that Baker drew almost none of the Phantom

Lady stories for which he has become famous. The most iconic of the

scandalously undraped PL pictures, the cover of Phantom Lady, No.17

(seen near here at the upper left, with other samples of Baker art), was,

Vadeboncoeur says, most likely drawn by Al Feldstein. The tip-off, “the

size of the breasts,” Vadeboncoeur says, “—Baker drew sexy women, but he didn’t

draw deformed ones. And he never drew hair like that. Nor eyebows.” Vadeboncoeur’s claim rests not just on his reputation as a superior spotter of art styles: he also reviews Baker’s alleged workload during the critical period and finds that if Baker produced all the pages attributed to him, he’d be penciling 70 pages a month. Clearly more than any artist could do and maintain any quality at all—and Baker was a quality artist. At his peak, Jack Kirby, renowned for his ability to produce pages, did about 25 penciled pages a week. To explain the 70-page workload he envisions for Baker, Vadeboncoeur reviews the history of Phantom Lady. The character was owned by Jerry Iger and produced by his shop, beginning with her Police Comics appearances. When Victor Fox wanted PL for his titles, requesting also that the drawing be done by Baker (who was already doing 22 pages a month for Fiction House characters, Sky Girl, Tiger Girl, Kayo Kirby and occasional others), Iger arranged to deliberately “fake it,” tricking Fox into thinking he was getting Baker Phantom Ladys. Baker may have done some penciling, Vadeboncoeur concedes—and he did do three stories (one each in Phantom Lady, Nos.14-15 and All-Top Comics, No.9)—but most of the actual drawing was done by Iger shop assistants and artists Feldstein, Jack Kamen and Alex Blum (who Baker had “touched up” since joining the Iger shop in 1944, making the female characters look sexier than Blum could). Then at the end of 1947, Baker left the Iger shop and was working directly for Fiction House—ergo, all of the Fox Phantom Lady stories in this volume are done by others. Not Baker, who was no longer working at Iger’s shop, producing pages for Fox. Thomas wipes some of the egg off his face with a prefatory note: “Well, we’re showcasing Phantom Lady, not Baker per se—still, it behooves us to suggest at this point that you take the credits as printed in Volume 1 with a grain (if not a whole shaker) of salt.” The

Phantom Lady of this volume is a lot better looking than the Phantom Lady of

Volume 1. Herein, she is spectacularly sexy—lots of leg and bosom—but some of

the poses are so lasciviously extreme as to be laughable, scarcely the work of

an artist known for drawing beautiful women. But the absence of Baker on Phantom Lady in a book ostensibly devoted to the Baker PL is only the first of two egregious bumbles in the book. The other is that the iconic Baker PL cover doesn’t appear in the book at hand. The problem is that PSArtbooks produced both hardcover and paperback editions of the Phantom Lady books, but the content varies from hardcover to paperback. In the hardcover volumes, Phantom Lady, No.13 (the first) to No. 17 (with the scandalous cover) appear in Volume 1; in the paperback, those issues appear in Volume 2. I, alas, bought the paperback of Volume 1; hardcover for Volume 2. So in the aggregate, my books are missing Nos.13-17. So if I want the complete thing, I now must go out and buy either the paperback Volume 2 or the hardcover Volume 1. Apart from the front matter and the comic book content I listed at the outset, Volume 2 of the hardcover (the one at hand) includes three of Baker’s unsold Flamingo comic strip about an exotic dancer—all, I assume, drawn by Baker. And the volume ends by reprinting an unused Phantom Lady story in b/w, not by Baker. This same story appears in color, Roy Thomas tells me, in the paperback Volume 2. There’s a third volume of this series, but its content varies from hardcover to paperback, too. Fox stories after Phantom Lady No.23 and the Ajax-Farrell material appear in Volume 3 of the paperback; they appear in Volume 2 of the hardcover. Keeping track of all this shifting ground is driving me nutty. The best course, if you’re a Phantom Lady connoisseur, is to purchase all paperback editions or all hardcover; don’t mix or you’ll get as thoroughly scrambled as I am.

But for genuine Matt Baker pulchritudinous femininity, we have the next volumes—:

The Lost Art of Matt Baker, Volume 1: The Complete Canteen Kate By Matt Baker; Introduction by Steven Ringgenberg; edited by Joseph V. Procopio 160 8½x 11-inch pages, color; 2013 Lost Art Books hardcover, $19.95; paperback, $14.95 Canteen Kate By Matt Baker; Introduction by Bob Burden 160 7x10-inch pages, color; 2013 Canton Street Press hardcover, $28.99 THE HEROINE of these Matt Baker tales gets her name from her occupation: she runs a canteen, a sort of diner, on or near a Marine base. And her habitual costume derives from this military association: her wardrobe is an olive drab Marine uniform, and she rolls up the legs of the trousers to make them shorts, and she wears her shirt untucked and unbuttoned by a couple buttons. If this were Phantom Lady, the unbuttoning would proceed through several more buttons to reveal cleavage and a navel. But this is not Phantom Lady. This is Canteen Kate. And she’s cute but not at all lascivious, leggy but wholesome.

Her bosom is generously proportioned but it’s not on display. The accent is on dimpled knees and well-turned ankles, not bulging boobs. Not Phantom Lady. Not imitation Baker. And like Sky Girl, Kate’s adventures are comedic rather than life-threatening. As Ringgenberg says in his Introduction, “the hijinks in Canteen Kate plots could easily be transposed into an Archie comic book. ... The stories always focus on the humorous scrapes Kate and her [male] pals [not lovers] get into on base and not on the horrors of [the Korean War, which is transpiring at the time].” Good clean fun. No sex. The content of these two volumes is nearly identical. The Canteen Kate part is identical: both reproduce all 22 Canteen Kate stories, beginning in Fightin’ Marines No.2, cover-dated October 1951, and ending, after three issues of her own title, with an appearance in Anchors Andrews No.1, cover-dated January 1953. If the Kate content is identical, why buy one over the other? Depends upon what you’re looking for and upon your taste. The Canton Street book includes an 8-page non-Kate story starring Leatherneck Jack from Fightin’ Marines No.1 (which is No.15 on the cover, taking over the numbering of The Texan) in August 1951. Drawn by Baker and appearing two months before Kate’s debut, it features a leggy babe, which the editors allow is “not exactly a Canteen Kate prototype.” She is cute and leggy but doesn’t appear all that often in the story. This volume’s Introduction by cartoonist and comic book writer Burden is a nearly pointless rambling about Burden’s encounters with various personages associated with Matt Baker. In sharp contrast, Ringgenberg’s preamble in the Lost Art book briefly covers Baker’s life and work and Canteen Kate’s history, including a couple of never-before-reprinted illustrations from Baker’s career as art director for Nugget, a Playboy imitator of the 1950s. No rambling. The Canton Street book prints all the Fightin’ Marines Kate first, then the Canteen Kate stories; Lost Art prints the stories in the order of their publication, but dates of publication are easier to find in the Canton Street book, which gives dates in the table of contents. The greatest difference is in the quality of reproduction. Both publishers shot from the pages of the comic books, but the Lost Art book reproduces Baker’s heroine about 20% larger than the original comic books. The percentage is slight enough that the linework doesn’t suffer (lines aren’t noticeably fatter, for instance), but it’s great enough to enhance detail by making it clearer—details sometimes lost in Canton Street’s re-coloring attempt.

The Canton Street book seems to be a one-shot enterprise. The Lost Art book is the first of three volumes devoted to the “good girl” art of Matt Baker. The second volume will collect Baker’s contributions to Wartime Romances, and Volume 3 will sample his war, western, and suspense stories. Where Sky Girl (with her dress always blown aloft enough to reveal luscious legs) fits into this, I dunno. But I live in hope.

The other great Golden Age limner of the curvaceous gender was Bob Powell, whose oeuvre was so varied and expansive that his women are often overlooked so it’s nice to see that neglect being corrected in—:

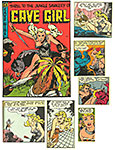

Bob Powell’s Complete Cave Girl Written by Gardner Fox and drawn by Bob Powell; Introduction by Mark Schultz with an essay by James Vance and John Wooley 168 6 ½ x 10-inch pages, color; 2014 Kitchen Sink imprint of Dark Horse hardcover, $49.99 THE OTHERWISE NAMELESS Cave Girl, whose adventures appeared in Thunda and in her own title from 1952 to 1955, was the last of the jungle queen genre. Inspired, doubtless, by the success of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan stories, both in print (since 1912) and on film, the jungle heroine also owes something to H. Rider Haggard’s 1887 novel She, whose protagonist, Ayesha, is the immortal priestess of a lost jungle city. But regardless of origin, the genre flourished through the 1930s and 1940s due, obviously, to the adolescent appeal of pictures of a healthy woman running around in a state of near undress. By Cave Girl’s time, however, the Comics Code Authority, tut-tutting disapproval over displays of the female epidermis since 1954, had worked its magic, shutting down Powell’s comic book. The scantily clad jungle adventuress survived briefly in the 1955-56 tv Sheena series starring the impressive figure of Irish McCalla. Vance and Wooley supply the historical details of the genre as well as tracing Powell’s career up through Cave Girl (but nothing about his subsequent work). Cave Girl’s last appearance was in the oddly entitled one-shot, Africa, Thrilling Land of Mystery, No.1, which, startlingly enough, carries the CCA seal of approval, achieved, according to Powell expert Ed Lane (quoted by Vance and Wooley), by adjusting her costume and deleting all sharp pointy spears. But the approved content included, as Schultz observes, “caricatures of African native peoples ... as either children requiring protection, slavering monsters, or comic buffoons. ... While Cave Girl can be admired for its forward-looking portrayal of a strong female lead (swimming against the tides of a post-World War II American that was conscripting pop culture to help strong-arm women out of industry and back to domesticity), its vision of Africans represents a stupid goose step down the wrong side of history.” While Powell was a master of the medium, manipulating its resources—camera angle and distance— to produce pages that pulsated with visual energy, he also captured masterfully the attributes of the rounded sex. He is, for example, one of the few—perhaps the only—comic book artists who treated the female bosom as two anatomical entities rather than a single double bulge: as they do in their natural state, breasts by Powell move individually, often stretching the fabric of blouses out of their tailored shape in sometimes awkward contradictory directions.

In Cave Girl’s case, Powell’s proclivity for animating her protrubences is emphasized, as Schultz says, by the design of “her off-the shoulder sheath” that “looks like it was only barely held together by an assortment of thongs and knots. Wardrobe malfunction always seemed one acrobatic leap away.” Adding to the fantasy of an erotic adventuress who is strong and capable is Cave Girl’s notable independence. Cave Girl, Schultz says, is “fiercely independent, self-sufficient, and unconcerned with male approval.” Unlike most jungle heroines, she is not perpetually accompanied by a male companion who does all the heavy lifting. And, as we’ve just seen, she actively resists any male attempt to tame her. The reproduction in this volume is superb, the best I’ve seen yet in reprint projects. In general appearance, the pages evoke the best memories of their original publication—except that all evidences of out-of-register coloring have been meticulously removed by retouching experts Ken Cooper and Mike Kelleher.

But the most famous was of the jungle heroines was undoutedly Sheena, “Queen of the Jungle,” who set the fashion for all the rest, as detailed in—:

Sheena, Queen of the Jungle; Volume One Collected Works, Spring 1942 to Fall 1948, Issues 1-4 Edited by Roy Thomas; Foreword by Bill Feret and Bill Black 290 7x10-inch pages, color; 2014 Roy Thomas Presents PSArtbooks slipcased hardcover, $xxx ALTHOUGH SHEENA’S inaugural run was in Jumbo Comics, starting with No.1 in September 1938, this volume reprints the first four issues of the character’s own title, which debuted in September 1942. Sheena was probably invented by Will Eisner, Feret and Black assert, despite a counter-claim by Eisner’s partner, Jerry Iger, who was more businessman than creator of characters. Eisner said he took the name from the H. Rider Haggard novel, She. Sheena started as a “Sunday” comic strip, manufactured by the Iger-Eisner Studio expressly for sale to overseas publications, which were using up syndicated American-created strips in Sunday format at a faster rate than they were being produced. To fill the void, Eisner concocted several “Sunday” format comic strips (Hawks of the Sea was another) that were distributed to foreign markets by Editors Press Syndicate which sold them to such publications as Wags, a weekly British and Australian periodical. Eisner and Iger also founded Universal Phoenix Features, their own syndicate, to distribute these Sunday format strips to American weekly newspapers. As far as I know, Sheena was never sold to American weeklies; instead, it re-appeared (after foreign circulation) in Fiction House’s tabloid-size Jumbo Comics, where it ran until the comic book ended in March 1953. Sheena also appeared in 18 issues of her own title, quarterly until it ceased with the Winter 1952 issue; the rest of the run will presumably appear in subsequent issues of this PSArtbook series. The only printed credit assigned to Sheena was that of “W. Morgan Thomas,” a house name that appeared on many of the Iger-Eisner productions. The first Sheena “Sundays” were drawn by Mort Meskin; he was followed by other Iger-Eisner shop artists. Starting with Jumbo Comics, No.28, the drawing was done by Robert Hayward Webb, who reportedly drew everything except Sheena herself; she was drawn by others who were more adept at rendering female shapes than Webb, a shortcoming he himself acknowledged. Webb also drew all of the Sheena stories in the book at hand. Sheena’s inaugural appearance not as flamboyant as later, when page layouts were adjusted to permit a display of her figure at full, seductive length; but that’s much later. Layouts start as routine grids in the first issue of Sheena (and, judging from the reprints of her first appearances in this volume’s front matter, Jumbo Comics); later issues show some variation, but Sheena still isn’t on display as a seductive figure drawing. But by the fourth issue in the fall of 1948, her costume has been modified to close up the decolletage a little (lest it offend, I assume). By then, her figure has filled out somewhat; at first, she was lithe rather than voluptuous.

In the second issue of Jumbo Comics, the third Sheena page (which is actually the ninth, counting the six pages in the first issue) introduces a young explorer named Bob. Bob will accompany Sheena for her entire publication life; a presumed romantic interest, he’s ever-ready to do the heaviest physical work. Sheena, as Feret and Black assert (and I wouldn’t doubt them), is the first successful female adventure character—heroine—in comics. And this volume is an appropriately careful introduction to her history. The Feret-Black introduction, recycling a portion of an article they wrote for AC Comics’ book about Irish McCalla, TV’s Original Sheena, is profusely illustrated with photos of the various writers and artists involved in the character’s history and actors in film versions, plus pages of the earliest Sheena “Sunday” pages.

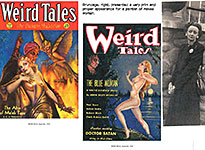

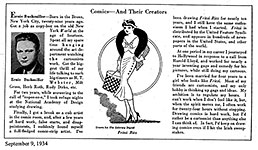

The Alluring Art of Margaret Brundage, Queen of Pulp Pin-up Art By Stephen D. Korshak with J. David Spurlock 184 9x12-inch pages, color; 2013 Vanguard Publishing paperback, $24.95; hardcover, $39.95 ALTHOUGH THE RAISON D’ETRE of this book is to print pictures of Brundage’s pulp cover paintings, a respectable quantity of text lurks within. After a Foreword by Rowena, the pictures are interspersed by several essays by friends and/or admirers, including the transcript of a 1973 interview with the artist, and ending with a 60-page biography with the intriguing title, “The Secret Life of Margaret Brundage,” who, it sez on the cover flap, was, with her husband Slim, in on the birth of the American counterculture. That may be a stretch, but Brundage and her husband, a hobo and Wobblies enthusiast, were clearly nonconformist habitues of the Bohemian hangouts in Chicago, particularly that which fermented at the Dil Pickle Club, a notorious hangout for “revolutionaries” and other advocates of counter culture. In

short, the text in this volume is as fascinating as the pictures. Perhaps more

so. Kelly Freas once told me he went into science fiction illustration because it was the only publishing enterprise at the time that permitted him to draw seductive women in various states of undress. The tradition may not have begun with Brundage, but her work certainly embodied it. Brundage

was not only first female cover artist of the pulp era, she was also the first

Conan cover artist. The book reprints all of her Conan covers plus the whole

Brundage inventory of Weird Tales covers (it

AND WHILE WE’RE ON THE SUBJECT of “good girl” art and while it is still the festive season, I can’t resist the temptation to insinuate into these proceedings a remnant of my own dabbles in the genre.

PERSIFLAGE AND BADINAGE Eddie Campbell, musing on his career: I am where I always wanted to be, but the comics medium is still ass-backwards. I would have wished it to have advanced differently. In my ideal universe the superhero would have disappeared by now. An intelligent world would have realized that this wish-fulfillment fantasy is absurd and would have rejected it. Instead it has been glorified and is now the foundation of the film industry. And yet he did some superhero comics—Hellblazer and Captain America in 2004. My first thought would be to say these are examples of not sticking to the plan. I didn’t go looking for any of these things. they all arrived by accident. But I used to have another rule about not turning down any work that comes along. One day you’ll be without work and you’ll be cursing yourself for all the ones you turned away. Asked what interests him these days about the medium and about the works coming out: I don’t really follow what’s coming out. The medium didn’t go quite the way I wanted it to go and I stopped paying attention. My interest in comics and cartooning tends to lead me into the backstreets of history. The world of any era, present or past, is only interesting to me when you get behind the facade, the pretense of what life is really supposed to be about. The main streets of history interest me no more than the main streets of today. The real story is always happening elsewhere. Nothing is what it at first seems to be.

BOOK REVIEWS Critiques & Crotchets

Percy Crosby’s Skippy: Daily Comics, Volume 1, 1925-1927 By Percy Crosby; Introductory Biography by Jared Gardner 330 8.5x9.5-inch landscape pages, b/w with some color; IDW Library of American Comics hardcover, $49.99 IF EVER THERE

WAS a cartoonist whose work deserves the enshrinement that IDW’s elegant

reprint series provides, it’s Crosby, possessed of one of the most

individualistic pen techniques in the history of cartooning. His famed

newspaper comic strip kid started in a magazine, not a newspaper: it debuted in

the pages of the old humor magazine Life in 1923. The March 15 issue

announced Skippy Skinner's imminent advent; the next week, March 22, the kid

arrived in all his spunky impudence on the first of his many full-page

adventures in the magazine as we see hereabouts. Crosby's sketchy, unlabored line has a ferocious energy, the vitality born of pen tearing breakneck across paper, and Crosby's subjects were imbued with that energy even if drawn in repose—which, with Skippy, was surprisingly often: he was frequently depicted in deep philosophical discussion with a friend, both seated on the curb. And the cartoonist's distinctive style of drawing is as much a part of his nine-year-old protagonist's character as the gags that gave him personality. Strangely, Skippy's anachronistic costume belies his character: attired always in an English schoolboy's gown (smock-like jacket), high Eton collar with flaring bow-ribbon tie, and short pants, Skippy should be a well-behaved momma's boy. Only his shapeless hat, tilted rakishly—provocatively, almost belligerently—over his eyes and his down-at-the-ankle socks betray him as a boy's boy, rowdy and roguish and just a trifle quarrelsome, who swaggers into view with his hands jammed deep into his pockets, strutting his neophyte machismo.

Skippy proved so popular that Crosby, who owned the copyright on the character, syndicated a daily strip version, starting June 22, 1925. Distributed at first by bush league syndicates, Skippy was eventually taken up by Hearst, beginning with the Sunday page in late 1926; then in 1929 on April 1, the dailies. The

volume at hand, the first of three that are presently available through IDW, is

an impressive package: the “dust jacket,” in the design by Lorraine Turner,

takes the form of a board fence across the bottom third of the cover. The board

fence was so much a part of the Skippy ambiance: Skippy and his cohorts often

conducted their deepest conversations in front of or hanging over the fence,

and it was the fence that the Skippy peanut butter people stole—without payment

or permission—along with the name of the protagonist, for the label of jars of