|

||||||||||

|

For a hare-raising post-Thanksgiving treat, we have Bill Watterson’s latest artwork, Batman postage stamps, Glasbergen’s Better Half (and more), celebrations of the Wizard of Id’s 50th anniversary, the PC of Zombies and evidence of Marvel’s growing diversity, and reviews Joyce Babner’s new graphic novel, Alice in Comicland, Scott McCloud’s Best American Comics, Bobby London’s Popeye (with a report of his firing in 1992 for attacking anti-abortion advocates), a book about New Yorker cartoonists, Bob Powell’s Terror Comics, Masterful Marks (Cartoonists Who Changed the World), Kim’s booty, and another end, that of Jonah Hex, editoons on post-election shenanigans, Bill Cosby and Ferguson, with an obit for editoonist and collector Art Wood and a radical plan for campaign finance reform. And the world’s funniest joke. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Watterson’s Angouleme Poster More Endorsement for the CGI Peanuts Cavna Now Full Time on ComicRiffs Marvel Worth More than DC Book Two of John Lewis’ March No More BECY Joyce Brabner’s Graphic Novel Batman Stamps Marvel Getting Diverse Glasbergen Retires the Better Half Zunar Still Harassed by Government Woodring Honored Palm To Get New Wall Scrawls

THE PC OF ZOMBIES

EDITOONERY Post-Election Dances Bill Cosby Ferguson Again Booty Call

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Wizard of Id’s 50th WuMo’s Not Funny Racist Editoon in Indy

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST The World’s Funniest Joke

BOOK MARQUEE Popeye: The Classic Newspaper Comics by Bobby London, Volume 2 London Interviewed after Being Fired over Abortion Strips Alice in Comicland The Best American Comics 2014 I Only Read It for the Cartoons: New Yorker Cartoonists Bob Powell’s Terror Comics BOOK REVIEW Masterful Marks: Cartoonists Who Changed the World

COLLECTOR’S CORNICHE Literary Digest Mini-bios of Cartoonists of the Thirties

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE War Stories The New and Wholly Unsatisfactory Lobo The End of Jonah Hex

PASSIN’ THROUGH Art Wood

A Radical Plan for Campaign Finance

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

BILL WATTERSON AT ANGOULEME The creator of

the beloved Calvin and Hobbes comic strip has stepped out of seclusion

once again—this time, to produce the poster for the 2015 Angoulême

International Comic Art Festival held every winter in France. So it was all a surprise to Watterson, who didn’t even know the award existed. “Nobody asked me anything,” he told Cavna at ComicRiffs. “I wasn’t even aware I’d been nominated. My syndicate sent me an email saying I’d won this award, and I literally had to Google it. People started talking about all the obligations that went with the prize, so I thought the whole thing was bananas, but Angoulême assured me there were no strings attached and they’d work with whatever I’d be willing to do. Drawing the poster sounded fun, so I agreed to do that.” Watterson said he wouldn’t be attending the event, but the recent show of Calvin and Hobbes originals at Ohio State’s Billy Ireland museum will travel to Angoulême for the festival. He talked about the poster with Cavna: “This is a comic strip about newspaper comics, presented as if it were a newspaper comic strip. But in all that circularity, I hope the drawings convey the fun and pleasure of cartoons in the largest sense. I still read newspaper comics, but without much hope for their future. As a small joke on myself, I deliberately set the story in a non-digital world, where the guy gets his morning newspaper in the yard, and the lady next door uses a big phone with a cord. For me, the anachronism evokes the distant heyday of the medium, and razzes how long ago my career was. “For this idea,” Watterson continued, “I wanted something simple, exaggerated, and silly—i.e., very cartoony. In that regard, I always think of Popeye and Barney Google as quintessential comic strips in that old rollicky, slapstick way we’ve sort of lost. So older comics were in the back of my mind, although I wasn’t trying to mimic anything specific. And to tap into one of comics’ great strengths, I chose to tell the story visually [without words], so that anyone of any age, from any country, could understand it. In this way, I was trying to connect the poster to my American newspaper comics background and acknowledge the international flavor of Angouleme’s festival.”

CGI PEANUTS ComicRiffs’ Michael Cavna stoutly (or at least circumspectly) maintained skepticism about the CGI Peanuts animation that’s a-borning with a debut date about this time next year. He says he has “two looming concerns” about a new 3-D feature film: “The first concern was that Schulz’s idiosyncratic line and visual style would become lost in the oversaturated tints of so much antiseptic CGI animation – a victim of the souped-up pixel. And the second concern was that the deeply familiar personalities, so crisply drawn out and layered by Schulz over a half-century, would be bent toward the narrative needs of a 2015 film that surely hopes to open to a holiday box office north of $40-million domestic, conservatively speaking. In short: would the masterfully modulated depths of various characters fall prey to the too-frequent tendency to play down to the kiddies by relying on snark instead of soul?” My concerns are somewhat the same—although I also am apprehensive about the too-polished look of the characters in faux three-dimension. But Cavna had a two-minute peek in mid-November, and felt “another balm for the diehard Peanuts brain. With each release of footage, my skeptical side keeps expecting the cinematic football to be pulled away at some point (blame the big-screen ‘Garfield’). Instead, though, my hopes are raised – and with the new trailer, we achieve serious elevation.” He was “absolutely assuaged” on his first concern and “considerably comforted” on the second. He likes the visuals, “which require paying homage to Schulz’s supple kinetic line while giving subtle dimensional shape and shadow to the iconic characters. Somehow, the filmmakers have solved the riddle of how to avoid the clinical, too-cool feel of much CGI – a trick that is so much more essential when the characters are imbued with true psychological dimensions (as opposed to, say, the intentional stock-comedy shallowness of Yogi Bear and Scooby-Doo). Assuaged, I became curious whether Team Peanuts was as satisfied with the results as I was. Comic Riffs reached out to both coasts involved in this creative high-wire act. They both echoed my sentiments.” On the West Coast at Peanuts Central in Santa Rosa, Cavna spoke with Paige Braddock, creative director at the Schulz Studio. Said Braddock: “I was talking to the director [Steve Martino] yesterday and I was complimenting him on the renderings of the characters. In terms of Charlie Brown, Steve took a character that already had a lot of depth and gave him even more. The lighting on his simple features, the nuances in movement of his simple eye shapes. Steve’s interpretation of Charlie Brown is completely endearing, and I think it will make fans fall in love with him all over again. “I know Snoopy is a fan favorite,” Braddock added, “but I really think Charlie Brown is going to steal some scenes of his own in this movie.” On the East Coast, Cavna got reaction from Neil Cole, the CEO of Iconix Brand Group, which owns 80-percent of Peanuts Worldwide. Cole said: “It’s great to see the incredible animation from Blue Sky Studios and Twentieth Century Fox come to life in today’s all-new ‘Peanuts’ movie trailer. The look is fresh and new, but at the same time, it’s clearly the ‘Peanuts’ characters that Charles Schulz created. Next year is sure to be a banner year for ‘Peanuts,’ which will also be celebrating its 65th year.” Sorry: I’m not convinced. Not yet.

CAVNA RIFFED? Not exactly. He’s not being forced to retire: he’s moving to full time on his ComicRiffs blob covering comics. According to Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist, Cavna started his comics blog for the Washington Post in 2008, working part-time, the rest of his obligation being as the Post’s tv/theater editor. A cartoonist himself, Cavna’s first allegiance is clearly to comics. He told Gardner: “The Post has been highly supportive of ComicRiffs since it launched, and while I enjoyed my run as the Post’s tv/theater editor, this has been a natural evolution as readers increasingly came to Comic Riffs. The Post has also been very supportive of my cartooning career, so it’s a natural. It also speaks to the tremendous changes in kids’ publishing, superhero films, webcomics and everywhere else visual storytelling is thriving.” As you’ve surely noticed, we quote from Cavna’s riffs here at Rancid Raves very often. And we’re happy to be able to continue to poach from him.

MARVEL WORTH MORE THAN DC This story first appeared verbatim n the November 21 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Much has been made of the arms race between Disney's Marvel Studios and Warner Bros' DC Comics to create superhero movies through 2020. Less debated is a key financial underpinning of the war: licensing revenue generates tens of billions of dollars for Hollywood companies, and DC needs a heroic effort to catch Marvel in licensing profits. On October 15, Warners CEO Kevin Tsujihara said that if he can close the current gap by half, the studio could earn an additional $150 million a year in profits. How big is the gap? In May, License Global placed Disney first among licensors with sales of about $41 billion in 2013; Warners was seventh with $6 billion. Both have strong properties: the Licensing Letter listed Marvel's Spider-Man global retail sales at $1.3 billion and Avengers at $325 million in 2013, compared with DC's Batman at $494 million and Superman at $277 million. "Marvel has a big head start," says Ira Mayer, publisher of the Licensing Letter, adding, "It's not that Warners can't do it, but it is going to take a lot of time and money and energy to make it happen."

MARCHING AGAIN Book Two of John Lewis’ autobiographical adventures in the civil rights movement continues his story. PreviewsWorld interviewed Lewis, his co-author Andrew Aydin and the artist, Nate Powell. “Nate and I joke about this sometimes,” said Aydin, “but it’s really pretty accurate: If Book One is Star Wars, then Book Two is our Empire Strikes Back. The stakes are higher, the heroes are stronger, more prepared, and the danger is more lethal. Book One focused on the congressman’s childhood and coming of age, studying and rehearsing in nonviolence workshops with the Nashville Student Movement, launching a sit-in campaign that successfully forced the city to integrate lunch counters, and eventually the formation of SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee). Now with Book Two, we show how these young people became a truly national force, and one of the key elements of the broader Civil Rights Movement.” Congressman Lewis chimed in: “So we talk about the Freedom Rides: a group of us, about a dozen people, black and white, young and old, set out on a Greyhound bus and a Trailways bus to ride through the heart of the deep South, to test the Supreme Court decision prohibiting segregation on buses. We were attacked several times, beaten, left lying in a pool of blood. One of the buses was set on fire. We knew that we might die. But we continued the Freedom Ride. More and more riders joined the movement. It became front-page news. Attorney General Robert Kennedy got involved, the governor of Alabama got involved, we were arrested several times, we spent weeks in Parchman State Penitentiary … but we dramatized the issue to the nation, and around the world, to see the reality of segregation in America.” Lewis continued: “Book Two also shows the March on Washington on August the 28th, 1963. I was 23 years old — I had just been elected chairman of SNCC a few months earlier, and after about a week I was invited to the White House along with representatives of several other organizations to discuss plans for the march. And it worked so beautifully. It was an unbelievable day. So many people worked so hard to organize a peaceful, orderly, nonviolent march. It really represented the best of America. Hundreds of thousands of people coming together to say ‘we want our freedom and we want it now.’ I spoke number six that day. Dr. King spoke number ten, when he said ‘I have a dream.’ And out of everyone who spoke that day, I’m the only one still around. So we tell the story.” Said Nate Powell: “I could tell how much our collaborative method had found its stride within just a few pages of breaking down the script for Book Two. After getting to know each other on Book One, we were able to come out of the gate swinging with the second, and that gave some much-needed room to allow for all the other considerations that go into the visual process for this story. I certainly had a better sense for the kinds of daily research and reference I’d have to do, the degree of double-checking along the way, and a sense of when some issues would give us problems down the road. Overall it’s been a much more natural and efficient process.” “To paraphrase something Dr. King once said,” Lewis finished, “there is no sound more powerful than the marching feet of a determined people. This book March is not just my story, it's the story of so many of us who stood up and spoke out, who studied the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence, who organized and made ourselves impossible to ignore. It is my hope that a new generation can read it and be inspired to march again.”

NO MORE BEST EDITORIAL CARTOONS Pelican Publishing announced that it is discontinuing the Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year series. The 2014 edition, available since last March, is the final volume in the 42-year run of the title. So unless some enterprising publisher picks up the series, we won’t henceforth have any more history on the hoof in ironic visual terms.

DALLAS BUYERS CLUB ON SECOND AVENUE By Michael Sangiacomo at the Plain Dealer in Cleveland Joyce Brabner, best known as Harvey Pekar's widow and collaborator (Our Cancer Year), released a graphic novel about early efforts in a New York gay community to fight the AIDS epidemic. Despite a weak, unwieldy title, Second Avenue Caper: When Goodfellas, Divas, and Dealers Plotted Against the Plague (Hill and Wang, $22) is a solid piece of work. And at 145 four-panel pages, it's a quick read. A graphic novel is only as good as its artist, and Brabner found a worthy partner in Mark Zingarelli, who faithfully translated the words into pictures. His artwork is well-done, consistent and makes the story easy to follow. The story opens with Joyce interviewing a friend, Ray Dobbins, who was horrified to watch his friends die slowly and in agony from a mysterious disease in the early 1980s, then believed to be an illness confined to the gay community. Dobbins learns of a treatment developed in Mexico, but not approved for use in the United States. Much of the book is about his successful efforts to run an underground smuggling operation to buy the drug in Mexico and sneak it across the border. Where do he and his friends get the money? From selling marijuana.

BATMAN STAMPED

MARVEL’S DIVERSITY DODGE As Marvel celebrates its 75th anniversary, it is working to take its growing catalog of characters into a future with a more diverse audience – and to use talent and staffing that better reflect the increasingly female and ethnically varied crowd at comic conventions, said Blake Hennon at herocomplex.latimes.com. Shorthand for that effort—a woman becomes Thor, and a black man becomes Captain America. Hennon continues: “Such dramatic changes coming simultaneously to two of the publisher’s classic marquee brands – names that front blockbuster film franchises at its sister company Marvel Studios – were celebrated by many people as positive progress, but others decried the decisions: ‘This is political correctness run amok,’ ‘Affirmative Action Man’ and ‘PC Avengers, Assemble!’ read parts of some readers’ reactions posted on Hero Complex stories about the announcements. “Whether they’re meeting fans or foes,” Hennon concludes, “— the new Captain America and Thor represent two ongoing concerns for Marvel and the comics industry’s growth: minorities and women.” Other recent inroads into the white male redoubt include Ms. Marvel, a young Muslim girl, and Captain Marvel, who is now female. Not everyone is keen on these innovations. Hennon quotes one skeptic—Christopher Priest, a former Marvel staffer who in the 1980s became the publisher’s first black editor (under his former name, Jim Owsley) and has written a Falcon miniseries and Captain America and the Falcon series in which the Falcon is Cap’s second banana. “It feels like a stunt,” he told Hennon in an email interview. “It would have felt like a stunt had I done it.”As he understands the development, Sam Wilson, the black guy who is the Falcon and who dons Captain America’s costume, wouldn’t become Captain America permanently. “Putting the black sidekick in the suit, when everyone knows sooner or later you’re going to switch things back to normal, comes off as patently offensive,” Priest said. Adding that he’d be “delighted” to be wrong about the Cap change being a stunt, Priest laid out what his former employer is facing: “Marvel’s challenge is to deliver something so affirming and positive that the work overcomes that cynicism. I assure you, Black America will be watching: Does this have real depth, or is it just surfacey costume-switching?” And he had some other advice for Marvel: “Hire some actual black people.” Tim Hanley, who wrote “Wonder Woman Unbound” and keeps statistics on female and minority workers at Marvel and DC in a column at Bleeding Cool, counts Marvel’s percentage of women working on its comics as varying between 8% and 15% in the three-plus years since he began keeping track, with ethnic minority numbers lower. “I don’t think Marvel’s done well diversifying its creators yet,” he told Hennon in an email, “but there are people inside the company who are very committed to doing so. I’m optimistic about Marvel in 2015; I wouldn’t be surprised to see their numbers for women and people of color grow significantly.”

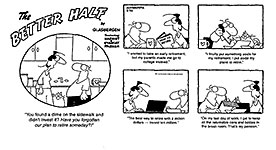

THE OTHER HALF DISAPPEARS Randy Glasbergen is retiring from the syndicated cartoon The Better Half he told Alan Gardner at DailyCartoonist.com. Glasbergen took over the panel in 1982 from Vinnie Vinson. Said Gardner: “He tells me that with his decision not to renew his contract with King Features Syndicate, the syndicate has opted to retire the panel completely. He says that his freelance business has been doing really well and consuming more of his time and the effort needed to produce The Better Half was becoming disproportionally larger than the financial return.” Glasbergen, the past master at comic noses, will still produce his other cartoons Glasbergen Cartoons and Thin Lines. In this vicinity, we’ve posted the final Better Half (for November 30), which is all about Harriet and Stanley’s “retirement,” and a short sampling of Glasbergen’s other cartoons. Although I think he’s a visualizing genius when it comes to cartooning anything, I’ve always been slightly disappointed that the jokes in so many of his single-panel cartoons are essentially verbal gawfaws. The pictures identify the speakers but otherwise don’t function in the gag itself. But in our third exhibit near here, the pictures do a little more of the comedy work.

I admit this is an almost pointless cavil: regardless of the gag—the combination of picture and words—Glasbergen’s pictures are always hilarious by themselves. There may not be verbal-visual blending in his cartoons—an aspect of all cartooning that I look for—but his cartoons are still rampant comedy, thanks to the pictures.

AND THE THREATS CONTINUE IN KUALA LUMPUR For a long time, cartoonist Zunar has been systematically harassed by the police and the Home Ministry for producing cartoons that were purported to be “detrimental to public order.” More than 400 copies of his books were confiscated and five of his books were banned by the Home Minister from 2009 to 2010. Government's determination to persecute Zunar has extended to printers, vendors and bookstores around the country: their places were raided and they were warned to not print and carry any of Zunar's book in future. In 2011, Zunar received the Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award from the Cartoonist Rights Network International, a cartoonists' rights NGO based in Washington, D.C. And in October 2014, one of Zunar's book, Pirate of the Carry-BN was accepted into the Library of Congress in Washington. Most recently (as of November 20), Zunar was questioned at length in local police stations. He refused to answer any questions. Meanwhile, the police have asked the online payment gateway that handles his book sales to list those who have purchased his books. Three of his assistants were detained for fie hours for selling his books. And the webmaster of the website selling his books was summoned to be questioned.

WOODRING HONORED Jim Woodring is the 2014 winner of the Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize—$2,500 and the two-volume set of Ward’s six novels published by the Library of America (plus a “suitable commemorative”). Sponsored by Penn State University Libraries and administered by the Pennsylvania Center for the Book, an affiliate of the Center for the Book at the Library of Congress, the Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize is presented annually to the best graphic novel, fiction or non-fiction, published in the previous calendar year by a living U.S. or Canadian citizen or resident. [Press release]

MERRY MURALS WILL REAPPEAR When the new Palm Restaurant in Los Angeles opened November 7 in Beverly Hills, its walls were bare. Still are. Mostly. They’re awaiting a fresh influx of caricatures of the Hollywood mighty. The Palm has its origins in New York on Second Avenue, where Pio Bozzi and his partner John Ganzi opened a restaurant in 1926 that became a speakeasy. Close to midtown syndicate and newspaper offices, the place became a hangout for journalists and cartoonists, and the latter started drawing their characters on the walls. Most of those pictures are still there: whenever the place needs a coat of paint, the management hires portrait painters who carefully outline and paint around the antique comic characters. The Palm became famous enough that a second edition opened across the street—Palm Two. Then in 1972, another Palm opened in Washington, D.C. After that, they sprouted up everywhere. There’s even one here in Denver. And in every one, caricatures adorn the walls. (The Palm in San Diego applied copies of the original Palm pictures to its walls, using some ultra-modern method of duplication.) In Washington, the caricatures are of politicians. In West Hollywood where the first L.A. Palm opened, the caricatures are of actors, actresses and movie moguls. But the new Palm has bare walls. “glaringly portrait-free slates that have caused a ripple of anxiety in moviedom over revoked statuses and set up a subtle new immortalization competition,” saith Brooks Barnes at nytimes.com. “The hand-wringing over the caricatures has taken years off my life,” said Bruce B. Bozzi Jr., great grandson of the co-founder and the executive vice president of the Palm Restaurant Group, which has 26 locations. “Do we move the old ones? That wasn’t possible. There were 2,300 of them. Do we pick 100 to move? The most powerful? No, I would be a dead man.” So he decided to start over, even though he knew some traditionalists would be unhappy. Only one image, to his knowledge, had ever been removed from the West Hollywood location: O.J. Simpson. (The restaurant covered him up after somebody — following his 1995 murder trial — stuck a steak knife in his portrait forehead.) Bozzi noted that none of the old West Hollywood caricatures were thrown in the trash. Instead, each picture was sawed off the wall and offered as a gift to the person who inspired it. Steven Spielberg and Brad Grey, Paramount’s current chairman, were among the others to request the images, Bozzi said. In the end, he did move a few of the old caricatures to the new restaurant. Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson, for instance, occupy a spot next to the front door. Farrah Fawcett and Lee Majors, painted as a pair, also made the cut. “I wanted to pay homage to the ’70s, when we first put down roots,” Bozzi said. So far, Bozzi has authorized five new power portraits: Amy Pascal, a co-chairwoman of Sony Pictures Entertainment; Sue Mengers, a talent agent who died in 2011; Sherry Lansing, the former chief executive of Paramount; Steven Tyler of Aerosmith; and the Bravo television personality Andy Cohen. Why them? “Because they’re fabulous,” Mr. Bozzi said, flashing a smile. (And at least a couple are his friends, added Barnes.) But none of them are characters from the comics. Beginning with Palm Two, that tradition was slowly eroded until, by Washington’s Palm, it was gone.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS The following is excerpted from excerpts of the oral history section of The Complete Zap, to be released by Fantagraphics this month. A longer version of excerpts can be found at tcj.com/zap-censorship-and-suppression/ The first underground comix backlash came from the usual suspects opposed to smut and licentiousness. America at mid-twentieth century was chock full of self-appointed, blue-nosed guardians of good taste who tried to control what could be shown in popular media and insisted that everyone follow their rules. Movies couldn’t be released without facing the Motion Picture Production Code. Books like Naked Lunch were banned in Boston and elsewhere, because they depicted perverse relationships. Race music was not played on the radio, and religious groups burned Elvis Presley records. A United States Senate subcommittee investigated juvenile delinquency in 1954 and accused comics publishers of contributing to it. The Comics Code Authority quickly stepped up to police the industry and quash the offenders. Magazine publishers like Ralph Ginzburg went to jail for trying to exercise free speech in print. For a long time, the most conservative elements of American society held sway over everything that could be read, watched, or heard in the media. The underground press found a way to bypass all these barriers by creating an alternative production and distribution system. Newspapers and comic books could be printed cheaply in small runs of ten thousand or less and spread around through a network of hip businesses and street entrepreneurs. Nobody in those networks cared about censorship.

And whilst we’re on the topic of horror, we cannot, any longer, overlook—: THE PC OF ZOMBIES Zombies and the rest of the undead are at today’s terminus of a trend toward political correctitude that began before any of us were born. Comics—of the newspaper ilk—had been criticized by Concerned Citizens almost from the beginning. And the criticism lurked, sometimes shouting and sometimes merely growling, ever since. With the advent in 1954 of the Comics Code, we learned specifically what the Concerned Multitudes were so concerned about. It was a long list. Prohibited were: glamorizing crooks, detailed plans for crimes, the words “horror” (and “crime”) on comic book covers, gruesome pictures, vampires, walking dead, cannibalism, profanity, smut, obscenity, attacks on religion, nudity, divorce, sex perversions, liquor and tobacco and fireworks advertising, scenes of violence—and more, much more, but all in the same Victorian vein. Mainly, Concerned Citizens objected to any affront to a nineteenth century sense of decorum. They didn’t like sex or ghoulishness or violence. Particularly, they didn’t like people killing people. The publishers and creators of comic books reacted accordingly. They skirted sex, avoided ghoulishness, and took all the weapons away from heroic characters. Batman couldn’t have a pistol. And even if he got one by disarming a foe, he couldn’t use the pistol against his opponent. No killing. In Westerns where wholesale gunfire is common, no one is ever killed. Gunfighters shot the guns out of the hands of the bad guys. No one died. Meanwhile, back at the superhero shops, the good guys in tights acquired new offensive armament. Force fields. Lighting bolts from the finger tips. These vibrations could render enemies unconscious or harmless. But nothing fatal or disfiguring. And no blood was shed. Simultaneously, the bad guys were no longer members of the human (sic) sapien species. They were alien beings—with force fields in their fingertips. So the superheroes were, at last, evenly matched. Their foes were not just crooks of the same species. They were superpowered aliens. So the superheroic good guys couldn’t be accused of bullying (which, in his inaugural appearance, Superman certainly could be), of beating up on ordinary, unpowered humanoids. Perforce, it was okay to pound non-human aliens—to dismember them, to blow them full of wholes. Admittedly, the stories told under these restraints quickly became dull. The trend reached its apotheosis in the movie “Man of Steel” wherein Superman and his similarly superpowered opponent, neither of whom, regrettably, has force fields under his fingernails, must resort to pure, unadulterated power: they run at each other and crash headon like a couple freight trains. After a couple of these, boredom sets in pretty quick. And the same kind of thing was transpiring in comic books. Then, to the rescue, we have the walking dead. At last, our heroes have opponents they can dismember and dispose of without killing them. Because they’re already dead. Hence, the ultimate in politically correct violence—superheroes battling and bloodily disintegrating zombies and similarly no-longer-alive beings. No one, apparently, objects to desecrating animated corpses.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy NO, WE’RE NOT FINISHED with the machinations of the Midterm Election. Before getting to that, however, return with us now to the days of the run-up to it, when Will Durst had this to say: “The country is abuzz with the same kind of anticipation normally reserved for marathon sock sorting. ... Midterm elections have always been the run of the balloting litter.” Because of the overwhelming lack of interest, he goes on, “we might be forced to merge the midterms with Hallowe’en. Why not? Same week. Besides, they have a lot in common. Lboth events highlight tricks and treats. Everyone wears costumes to disguise their true identities. All the real action occurs in the dark. John Boehner looks like a pumpkin. And, not infrequently, the face under the mask is the scary one.” As usual, we now take up a selection of the best editoons of the last month to explore the different ways cartoonists have deployed images and visual metaphors to comment on the passing political (and sometimes social) scene. In the wake of the recently interred Election, the punditariat has been up to its usual tricks—:

When in danger, when in doubt, Run in circles, scream and shout.

The gasbag fraternity has wasted no time in calling the victory of the Republicons “a trouncing! A tsunami! A shellacking!” Even, on hysterical occasion, “a landslide!” “A mandate!” But it is none of those things, as Juan Williams so pointedly observed in The Hill.com. The Republicons enjoyed a clear victory, but during off-year elections like this one, the opposition party historically picks up an average of 29 seats in the House and six seats in the Senate. By this yardstick, then, this year’s fiasco at the polls was no different than most Midterm Elections. In fact, a little worse: the Republicons gained only 15 seats in the House albeit 8 in the Senate. It was certainly no turning point in American politics as so many of the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm would have us believe. Nor was it a whole-hearted endorsement of the GOP posture, Williams observed. A CNN poll found that only 40 percent of Americans have a positive view of the Republicon Party, compared with 44 percent of the Democrats. And 80 percent, taking both parties together, have a negative view of Congress. Most other countries (as we’ll see, again, Under the Spreading Punditry below) can’t understand how the Republicons “won” the Election. In France’s Le Monde, Alain Frachon, quoted in The Week, noticed that the GOP won by conducting an entirely negative campaign alleging that everything wrong with the world is Obama’s fault. The Republicons offered no vision of their own, other than to slash taxes and gut environmental protections. Why would American voters reward such a message? Most of them didn’t; they stayed home. The vote was effectively won by the “omnipresent, unlimited, corrosive” impact of money—donations by big business to the GOP. And that party refuses to participate in democracy, which requires compromise for the good of all instead of insisting on its way or nothing. True. In fact, the GOP intransigence amounts to treason. The ingeniously contrived checks and balances built into the U.S. Constitution require compromise; those who refuse to compromise are ipso facto effectively traitors. Incidentally, in most European countries, the government funds political compaigning so the vested interests of plutocrats don’t control the outcome as easily as they do here. In

any event, in assessing the alleged Republicon victory, Steve Sack’s image

at the upper left in our first visual aid is bitingly accurate. And Sack continues in the next cartoon around the clock to drub the GOP for what it is—resoundingly hypocritical. They rig the election and then claim “the people have spoken!” In the next two cartoons, the wave metaphor is dismantled. In the first, Clay Bennett depicts the boat of Democracy about to be swamped by a wave of Dark Money, an image that vividly acknowledges another ingredient of the GOP recipe for victory. And Tom Toles at the lower left gives the wave another meaning, showing the Pachyderm about to be overwhelmed by the elements responding to climate change. With typical myopia, the poor li’l elephant doesn’t understand that the voters cannot vote climate change out of office. To take Toles’ imagery another step, it shows that for the GOP, wining elections is all that matters. But we knew that, eh?

IN THE NEXT

EXHIBIT, we take a few peeks at the future of the life in official Washington,

post-election. Finally, Sack returns again, this time deploying the “lame duck” description of Bronco Bama’s last two years in the White House to produce a vivid picture that contradicts the notion that the Prez will not be able to function. Clearly, this is a duck that doesn’t know the meaning of the word lame. The

relationship of Obama and Congress continues to preoccupy the editoonists in

our next display. In the grip of its customary self-contradictory mode, the GOP describes Obama as a dictator issuing laws without legislative approval and on the other hand as a milk-sop Prez who is too weak to hold and wield the office. Can’t be both, kimo sabe. So which is it? Neither, of course. Each GOP extremity extends the party’s “big lie” policy when it comes to Obama. Although both Reagan and George H.W. Bush issued executive orders about how to implement the nation’s immigration laws, neither of them, the GOP claims, went as far out on a limb as Obama. But the Associated Press disagrees, citing White House officials who released statistics showing that Bush’s order protected about the same percentage of immigrants that Obama’s action is projected to protect, though far fewer in raw numbers because there were only 3.5t million immigrants living in the country illegally in the early 1990s. To steer away from rabid politics for a calmer conclusion, take a look at the lower right for Bill Day’s telling combination of two issues in one picture—the White House intruder and the ebola intrusion. Nifty. While it’s clear that, like the security for the White House, the security at places of entry to this country from Africa was somewhat feeble, ebola is not as fatal a disease in the U.S. as it is in Africa. About 70 percent of the 13,000-plus cases in Africa are fatal; in this country, only two of ten cases have resulted in death (20%). So ebola is not an automatic death sentence despite what we hear in the “froth estate.” Why not? We’ve heard there’s no cure, so how do people survive here in the U.S.? In this country, we have many hospitals, extensive staffing and lots of sophisticated equipment. All assure attentive treatment. Vital bodily fluids lost (up to 5 gallons a day) through vomiting and diarrhea are replenished via an IV-drip to prevent the organ failure and shock that lead to death. Doctors monitor and adjust electrolyte levels in the blood. In Africa, IV lines, saline solution and monitoring equipment are in short supply. And Africans, knowing that people die in treatment facilities, don’t seek treatment until they are too sick, their organs already failing. No cause for panic, whatever you may have heard in the public prints. And then we come to the hapless Bill Cosby. It’s a mark of the esteem in which the comedian is held that no editoon I’ve seen so far shows him caught with his pants down around his ankles. And in our exhibit, Joe Heller’s paired images merely mirror us shaking our collective head in amazement and sad surprise—like Cosby over Charles Manson, and Manson and the rest of us over Cosby. We are angered as well as saddened to witness an icon brought low. Did Cosby do it? Of course. He doubtless had sex with many young women—many many more than the dozen or so who have thus far come forward with their stories of seduction, assault and rape. The accusations of even a half-dozen women suggest that Cosby experienced great success in his pursuit of random sex. If he hadn’t had success, he wouldn’t have continued, and if he didn’t continue, we wouldn’t be hearing from even the relatively “few” who’ve been speaking out. Nothing but success could have persuaded him to continue the same pattern of behavior. So I have no doubt that he was guilty as “charged.” But his guilt is not being determined in a court of law. It’s the social media that is accusing him—and convicting him. No trial. No lawyers. No cross-examination or procedural rules designed to protect even the accused. He’s being ganged up on. And all the outcry in the social media is based upon the testimony of accusers some of whose stories might collapse under cross-examination in a court of law. Moreover, he’s being “convicted” for violating today’s sexual mores when, for much of his career, other standards prevailed—particularly in the entertainment industry. The social media are convicting him without a trial. And they have very little actual evidence. That’s what gets my wattles in an uproar. One of his accusers wasn’t actually raped: she was assaulted but escaped before Cosby could do the deed. Another of the accusers was, by her own testimony, raped more than once. Okay: the first time, the 17-year-old girl could plead that she didn’t know what she was getting into when he invited her to his room. But “multiple times”? So when does it stop being rape and start being consensual (or contractual: you do this, and I’ll help you in your career)? Lest it look like it, I’m not defending Cosby. He was a shameless womanizer, taking advantage of his fame and power to overwhelm young women. Despicable behavior in anyone, but in a beloved funny man and a national father figure, more than despicable. Indicted and tried by the social media, Cosby is now humiliated and shamed. There is a certain rough justice in that: the accusing social media have now brought about the only punishment possible, destruction of his public personna. And that’s probably what he deserves.

JUST AS I WAS PUTTING THE FINISHING TOUCHES on this posting, Ferguson erupted again. More than any of the many aspects of “Ferguson,” the rank stupidity of the authorities stands out. Why, for instance, wait until nightfall to announce the results of the Grand Jury deliberation? After dark, all kinds of civic disobedience and mischief are possible—more than during daylight. Why encourage riot by waiting for the cover of darkness? And then the national guard, diligently on stand-by in case it would be needed, was not called up in time that night, so a dozen commercial buildings burned down, other businesses were looted, and 12 vehicles were torched. Authorities made 61 arrests, many for burglary and trespassing, and an additional 21 were arrested in nearby St. Louis. All this “demonstration” happened because the African American population of Ferguson didn’t agree with the Grand Jury decision. And that, too, was predictable. In fact, I suspect mobs would’ve filled Ferguson’s streets no matter what the Grand Jury decision: it’d be an angry mob or a joyful one. As

a white man, I can scarcely make a decision on the matter that is any more

accurate than a black man’s. The family of the slain Michael Brown held a press conference and claimed the Grand Jury process was rigged to clear Darren Wilson, the white officer who shot the teenager to death. Prosecutor McColloch has been strenuously criticized for adopting an a-typical process for the Grand Jury’s deliberations: he arranged for it to see all the evidence, hear all the witnesses, instead of aggressively pressing for indictment. And yet, reading John Cassidy’s report of Wilson’s testimony at The New Yorker online, I did not conclude, as he did, that Wilson wasn’t subjected to sufficient cross-examination. Wilson’s account of what happened seemed plausible; and the prosecutor’s analysis, offered as he announced the Grand Jury’s finding, found that Wilson’s testimony was for the most part supported by the physical evidence. Wilson’s story was that he stopped Brown and Brown’s friend and asked them to walk on the sidewalk instead of in the middle of the street. Brown responded with an obscenity and kept on walking. (My wife remembers that Brown’s mother, interviewed last August very soon after the killing of her son, admitted that the kid had “attitude.”) Wilson then realized Brown was carrying some cigars and wore clothing that matched that of a reported shoplifter; he backed up and stopped the teenagers again, but when he tried to get out of his vehicle to talk to them, Brown approached and slammed the SUV’s door on the cop, keeping him in the vehicle. They had a little tug of war over the door, and Brown reached in through the open window and punched Wilson in the face. Wilson tried to pull his gun, threatening to use in on Brown; Brown asserted with another obscenity that the officer didn’t have the nerve to do it. They struggled over the gun; Wilson finally freed the gun and got off a shot, hitting Brown in the hand. Then Brown ran. Wilson gave pursuit. Cassidy, reviewing this testimony, wonders, in effect, why Wilson went after Brown: “What stands out is that once the second shot had been fired and Brown had started to run, he no longer represented a deadly threat to the officer or to anybody else. He was a large, bleeding, unarmed man running down the street in an attempt to get away. Wilson, who chased after Brown, was the one with the deadly weapon.” Well, yes. But police always have deadly weapons. And Brown’s attempt to get away is the action of a guilty person. My guess is that Wilson went after Brown because the kid had demonstrated criminal behavior: he refused the lawful order of a policeman to stop walking in the middle of the street, he looked suspiciously like the shoplifter, he assaulted the officer, and he was fleeing from a policeman who wanted to question him about a crime. What would we expect a police officer to do in these circumstances? Let the suspect escape? And Brown was no longer a deadly threat to anyone? That, it seems to me, is a matter of interpretation. Running after Brown, Wilson called for him to stop. And when Brown did, he turned around and came toward Wilson. Maybe he was charging; maybe just walking. But he didn’t drop to the ground as Wilson ordered him. And so long as Brown kept coming, Wilson felt threatened. Wilson is 6-foot 2-inches and weighs, it is said, 120 pounds. Tall and skinny. Brown is 6-foot 6-inches and weighs 190 pounds. He’s comparatively formidable physically. And he’s obviously angry. And this neighborhood in Ferguson is a high crime area. All of which makes the “teenager” a considerable threat not just a mischief-maker or a harmless runaway. Wilson fired several shots at Brown, most of which hit the kid in the right arm. Perhaps because he had his right arm ahead of him as he was charging Wilson; perhaps because he was holding his arms over his head in surrender. The latter doesn’t sound as convincing as the former; but, again, I’m a white guy. Wilson finally stopped Brown by shooting him in the head. Whether Wilson’s account is objective and not self-serving is immaterial. As I said, no matter what decision the Grand Jury reached, there was a mob a-borning in Ferguson that would have rampaged through the downtown once they knew the decision, whatever that decision was. And Wilson’s testimony is immaterial on yet another score—the larger issue of the distrust and animosity that prevails between American law enforcement, mostly white, and a black citizenry wherever it resides. Given that animosity, Wilson’s behavior as an officer of the law, Brown’s behavior as a big black teenager with attitude, and the inevitable outcome made the episode a proxy for longstanding race relation problems in this country. David Fitzsimmons’ cartoon, second from the upper left, is as accurate and forceful a depiction of this unhappy state of affairs as any in our exhibit. Ferguson is all over the map, everywhere in the country. And that’s the fundamental problem: our slave-holding heritage, not the conduct of a policeman in a suburb of St. Louis and the teenager he accosted there. As for the riot itself, there were clearly people in the streets who wanted to wreak havoc. Brown’s “step father” was filmmed yelling “Burn the place down, burn the place down” repeatedly, whipping the crowd into a destructive frenzy. But even without him, there are a-social elements in any crowd, as cartoonist Nease shows us at the lower left. My guess is that a considerable number of the rioters and looters were simply neighborhood hoodlums for whom wholesale destruction of property is their idea of a good time. Surely no other group of Ferguson’s black population would condone the destruction of local businesses that provide jobs to the community. And in fact, it is hard to find anyone interviewed on the omnipresent “news” media who said he/she thought destroying buildings and property was a good idea. Another fact not widely reported: there were a considerable number of young African Americas trying to stop the destruction. Ferguson should be a learning experience for America, white and black. Chances are, though, it, like so many other Michael Brown/Trayvon Martin episodes, will fade from memory and the public agenda. And we’ll continue to have a society in which black mothers, like the one in Pat Oliphant’s cartoon from last summer, have a grimly distasteful job to do in raising their children. “Don’t look suspicious,” she tells her son, “—or the police gone shoot you.”

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS The following is excerpted from excerpts of the oral history section of The Complete Zap, to be released by Fantagraphics this month. A longer version of excerpts can be found at tcj.com/zap-censorship-and-suppression/ MOSCOSO: Crumb and Wilson were using

[Will] Eisner’s technique. The story had a beginning, middle, and an end.

Griffin and Moscoso weren’t doing that. Our stories had no beginnings, no

middles, and no ends: a non-linear story. That’s interesting. And not only is

it interesting, it’s more lifelike. When you get up in the morning, and you go

out in the street, you don’t have a linear day. You don’t know who you’re going

to WILSON: My idea is not to entertain them but to enlighten them. Or to make them sick. One or the other. Sometimes it happens simultaneously.

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words IN CASE you hadn’t noticed, T&A is passe; with-it dudes refer to B&B—boobs and booty. On November 12, Joseph Pisani at the Associated Press wrote: “Gym classes that promise a plump posterior are in high demand. A surgery that pumps fat into the buttocks is gaining popularity. And padded panties that give the appearance of a rounder rump are selling out. The U.S. booty business is getting a big bump.” The padded pantie entrepreneur notes, “People just want more booty.” Well, not “people.” Women. Women want more booty. “Every girl wants a booty,” says the operator of a gym class in Boston. And Pisani can’t resist an opportunity for double entendre: “Some businesses that specialize in butts say pop culture has had a direct impact on their bottom line.” Ouch. It

all started with Kim Kardashian, Pisani says. And the same day I read

his report, Kim’s big booty, polished to a high sheen with oil, appeared online

in a copy of the cover of the winter issue of Paper magazine. On the very

same day. Seldom have I been on the crest of a wave of popular culture.

So I’ve savored the experience, and to enable you to do the same kind of

savoring—albeit not on the day the wave broke—here’s an assortment of Kim’s

booty. Paper magazine, it seems, has two Kim kovers [sic]. The second one, it avows, is

just as “bootylicious, but is safe for work. Kim is posing in an evening dress

shooting champagne out of a bottle into a glass that’s resting on—her

backside.” About which, Kim is alleged to say: “And they say I didn’t have a

talent. Try balancing a champagne glass on Not to be bested in booty, the mischievous Craig Yoe rounded up another assortment of famous booty—those by Frank Frazetta, R. Crumb, Paolo Elenteri Serpieri, and Tom of Finland. Then I added one of my own confections—and we’ve augmented our rump fest with the accompanying display of the whole enchilada.

READ AND RELISH “Gay people have a different role than other minority groups. Very few black kids have ever had to worry about telling their parents that they were black.”—Barney Frank “See what the boys in the backroom will have, and tell them I died of the same.”—Marlene Dietrich sang it, and I just wanted to store it away somewhere—here—so I’d have it handy next time I need it. “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”—F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping DAGWOOD’S

DILEMMA here immediately conjures up the White House fence jumper, who

penetrated far into the Executive Mansion before being reined in. In the next strip, Mike Peters at Mother Goose and Grimm continues to explode the limits of traditional taboos in newspaper funnies. My guess is that the gag began with the expression “fixed” that is often used to describe neutering surgeries. (But you knew that, too, eh?) As for the other two Grimms, which happened on successive days, I enjoy seeing a comic strip playing with its medium and with visual symbols. It’s like breaking the fourth wall in movies or on stage. Jeff Parker’s perfect capturing of Beetle Bailey and Linus and Lucy is frosting on the marshmallow.

YOU’D THINK,

LOOKING at these four consecutive Mutts strips, that Patrick

McDonnell was scrimping on “Oops” is a perfect punchline for the second day. And a magic wand that’s invisible is a next logical development. On the fourth day, I got a bang out of Linus showing up—surprise! And all this time, I thought he’d be diligently awaiting the arrival of the Great Pumpkin.

COULDN’T HELP but notice that The Wizard of Id passed the 50 years mark on November 17: half-a-dozen strips in the Denver Post (the local press) celebrated with congratulations.

According to the GoComics website, cartoonist Johnny Hart, creator of B.C., came up with an idea for a second comic strip while flipping through a deck of playing cards. In other words, it wasn’t the court magician that struck his fancy: it was the king (whose playing card image shows up in the celebration in Patrick McDonnell’s commemorative Mutts). Hart enlisted longtime friend and mentor, Brant Parker to help co-produce and draw The Wizard of Id. To help celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Wizard, GoComics launched Wizard of Id Classics to reprint some of the strip’s hijinks moments wherein you can meet again the Wiz, Blanche, Bung, Rodney, the King “and all the other ‘ID-iots’ from the very beginning!” Meanwhile, as we see on the accompanying visual aids, several comic strips helped celebrate the anniversary: McDonnell’s Mutts, Marc Hamilton’s Dennis the Menace, Mort Walker’s Beetle Bailey, Blondie, Mike Peters’ Mother Goose and Grimm, Jim Davis’ Garfield, and, in the next exhibit, Gary Brookins and Susy MacNelly’ Shoe, Jack and Carol Bender’s Alley Oop, and both the Hart-inspired strips. B.C. is now produced by Hart’s grandsons, Mason and Mick Mastroianni; and the Wizard, by Brant Parker’s son Jeff and his wife, plus the Mastroiannis. Other

celebrations took place in strips not pictured here: Jerry Van Amerongen’s Ballard Street, Ralph Hagen’s The Barn, Mark Parisi’s Off the Mark, Brian Crane’s Pickles, Mark Buford’s Scary

Gary, and Dave Coverly’s Speed Bump.

HELP ME. WHAT’S FUNNY about these WuMo strips? In the next one—about a beauty pageant—we find a sow competing. And after losing several recounts, the sow admits defeat. That’s no surprise. You’d expect that outcome—if a sow ever competed in a beauty pageant. Is that the funny part? A sow competing? (It certainly isn’t that the sow is Miss Colorado, which, I take it, is entirely gratuitous.) Or are all contestants in beauty pageants sows? If so, how’s that funny? Satirical maybe, but not funny satirical. In the third strip, a woman is complaining to her “husband” that his conversation is repetitive. He’s a parrot, so what do we expect? Is the core of the joke the predictability of a spouse? From that, we spring with a single bound to the highly unlikely situation that a woman might marry a parrot. So predictable spouses are parrots? I’m not laughing. Finally, here’s Hallowe’en. The little monsters in Monsterland are dressed up like people? We know it’s Monsterland because the person at the door is a monster. And, upon close inspection, we see that the kiddies are all monsters, too, encased in human masks. Mildly amusing, but also somehow predictable. The whole joke idea of trick-or-treaters being monsters is worn out. It’s been done. I’m sure. Over and over. From the GoComics site, we have this tout about WuMo (named, as you’ll see, for the first letters in its two author’s last names, a contrivance as opaque as the comedy in the strip)—: WuMo celebrates life's absurdity and bittersweet ironies, holding up a funhouse mirror to our modern world and those who live in it. Thanks to its delightful artwork and irreverent humor, this hilarious comic by writer Mikael Wulff and illustrator Anders Morgenthaler has grown from an underground sensation to one of the biggest and most popular strips in Europe. WuMo's inventiveness is reminiscent of their countryman Hans Christian Andersen—if Andersen's fairy tales had been populated by sadistic pandas, disgruntled office workers, crazy beavers, Albert Einstein, Snoop Dogg and Darth Vader. With hype like this, I’d expect to encounter roaringly hysterically funny stuff. Not this lame recitation of the obvious and the obtuse. Ahhh, those Europeans—a tricky lot. Whimsey. Maybe that’s at the heart of WuMo’s comedy. But I’ve seen better whimsey. Mutts, f’instance.

FINALLY, to end

on historical notes, we have the eponymous Dilbert displaying a mouth, which,

as we all know, he seldom does. Incidentally, here Dilbert is wearing his customary necktie, which stands erect below his chin. But in other episodes lately, I’ve noticed the tie is gone. Instead, there’s a tiny square thingy on a string around his neck. Is this a name badge? Or is it some sort of electronic device? And just to prove that Dagwood isn’t the only comic strip character who dabbles in politics, here’s Baldo with a sarcastic display of campaign signs. Alas, not true. But should be. And here’s a left-over from the Editoonery Department—a Gary Varvel cartoon published in the Indianapolis Star on the day after Obama’s immigration speech. It prompted immediate protest from some readers, who said the cartoon was racist. To them, the immigrant leading the invasion through the window is Hispanic: after all, he wears a ball cap and has a bushy moustache. The protestors evidently didn’t see that they were employing the same kind of racist imagery that they accused Varvel of using. But it didn’t matter. Newspaper editors these days quake in fear of reader protest, and as Latino population approaches 17% of U.S. citizenry, they quake at 7.8 on the Richter Scale at the thought of offending any portion of the Latino population. So the editors, caving, as usual, to what ever smattering of protest hits the window, reacted: they eliminated all racist innuendo by removing the guy’s moustache. Now he couldn’t possibly be a racist caricature. But he was, if we use the remarks in the speech balloon as a guide, an immigrant. What’s the word for prejudice against immigrants? Immigrantist? Varvel is clearly against Obama’s immigration policy, but he claimed (and his editors supported him) that he harbored no racist intention with the cartoon. Executive Editor Jeff Taylor said that Varvel did not intend to be “racially insensitive” or for the cartoon to be read literally. “He intended to illustrate the view of many conservatives and others that the President’s order will encourage more people to pour into the country illegally,” Taylor explained. From my point of view, the cartoon was tasteless whether it was racist or immigrantist or not. And some readers didn’t like the cartoon with or without moustache. One noted that Thanksgiving was first celebrated by undocumented pilgrims who sat down to a meal with the native-born indigenous people of the “new world.” Next, the Star removed the cartoon from its website without explanation. Then the following day, Taylor explained, saying: “This action is not a comment on the issue of illegal immigration or a statement about Gary’s right to express his opinions strongly. We encourage and support diverse opinion,” Taylor wrote, but in this case, “We erred in publishing it. The depictions in this case were inappropriate; his point could have been expressed in other ways.” The non-cartooning population can be depended upon to say “it could have been expressed in other ways.” Maybe. But the non-cartooners never offer another way. Varvel did, though. He published several cartoons in response to the Prez’s immigration actions, which are expected to grant up to five million unauthorized immigrants protection from deportation. One cartoon showed the President’s car driving over the United States Constitution. Another showed the President dressed as a king for deciding to take action on his own. As for the offending cartoon, Taylor went on, “I was uncomfortable with the depiction when I saw it after it was posted. We initially decided to leave the cartoon posted to allow readers to comment and because material can never truly be eliminated once it is circulating on the web. But we are removing the cartoon from the opinion section of our website, as well as an earlier version posted on Facebook that showed one character with a mustache.” Among editoonists, while all agreed that publication decisions rest with newspaper editors not their cartoonists, many voiced disgust that editors respond to reader criticism of a published cartoon by, first of all, apologizing for it, and second, censoring it after they have published it. Said one: “It's incredibly creepy to toss art down the memory hole because a few people have complained. More than that, editors ought to stand by what they publish after they have published it. Once it’s out there, the cartoon is the responsibility of both the cartoonist and the editors who approved it. It's incredibly cowardly to throw the cartoonist under the bus for a cartoon that the editors have signed off upon.”

AND THEN

THERE’S THIS, the Blondie strip accompanied by R.L. Crabb’s Roadskill, about which Crabb

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. SEVERAL CENTURIES AGO in the raw months of my Long-lost Youth, I heard of a survey conducted in England to discover the “funniest joke in the world.” I looked it up, and this is it—:

Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson go on a camping trip. After a good dinner and a bottle of wine, they pitch their tent and go to sleep. Some hours later, Holmes wakes up and nudges his faithful friend. "Watson, look up at the sky and tell me what you see.” "I see thousands and thausands of stars, Holmes,” replies Watson. “And what do you deduce from that?” said Holmes. After thinking for a moment, Watson replies: “Well, astronomically, it tells me that as there are billions of galaxies and potentially billions of planets, others may now be looking at their sky. Astrologically, I observe that Saturn is in Leo. Horologically, I deduce that the time is approximately a quarter past three. Meteorologically, I suspect that we will have a beautiful day tomorrow. Metaphysically, I can see that we are a small and insignificant part of the universe. What does it tell you, Holmes?” Holmes is silent for a moment. "Watson, you idiot!” he says. “I deduce someone has stolen our tent!”

Not content with having discovered the world’s funniest joke, the surveyors also determined the second funniest joke, to wit—: Two hunters are out in the woods when one of them collapses. He's not breathing and his eyes are glazed, so his friend calls 911. "My friend is dead! What should I do?" The operator replies, "Calm down, sir. I can help. First make sure that he's dead." There's a silence, then a loud bang. Back on the phone, the guy says, "OK, now what?"

You may or you may not be gratified to know that in recent times, the relative positions of these two jokes has changed. Sherlock and Watson’s camping trip is now the second funniest joke in the world, and the murdering hunter is the funniest. Must have something to do with the National Rambo Association.

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews and/or Previews of Coming Attractions This department works like a visit to the bookstore. When you browse in a bookstore, you don’t critique books. You don’t even read books: you pick up one, riffle its pages, and stop here and there to look at whatever has momentarily attracted your eye. You may read the first page or glance through the table of contents. All of that is what we do here, starting with—: Popeye: The Classic Newspaper Comics by Bobby London, Volume Two, 1989-1992 By Bobby London 340 8.5x7.5-inch pages, b/w; 2014 IDW hardcover, $39.99 THIS VOLUME of the London Popeye, the second of two, includes the 3-week sequence that got London abruptly fired in 1992. According to the IDW blurb about the book in Diamond’s Preview: “King Features pulled ... three weeks of strips, and daily newspapers began running reprints. Now, 22 years later, thanks to the kind cooperation of the good folks at King Features, those three weeks—plus an additional six weeks of never-before-seen strips—will be included in this volume.” Our “short review” ends here; what follows is history and wild but educated guessing. The three weeks at issue (July 6 through July 25, 1992) were what ended London’s Popeye gig. I’m not sure about the “additional six weeks”—were they part of the sequence that got him fired? or were they an entirely separate sequence that King had declined to distribute at some earlier time, asking London for new strips? Dunno; we’ll find out when the book arrives here. But the three weeks that King “pulled” weren’t pulled everywhere: they actually got into print in one newspaper. In my current dotage, I can no longer recall the name of the paper, but it was a weekly that printed nothing but a week’s worth of all sorts of comic strips. I subscribed, and the news about London’s firing broke just about the time the issue containing the questionable strips arrived in my mailbox. So I clipped and saved the damnable things. Here they are—:

As any fool can plainly tell (I can tell), the questionable part of the sequence begins at the end of the second week here when Popeye suspects Olive of having an affair—and an illegitimate child—with Bluto. From there, it plunges on into the abortion issue. And hence to religious questions. On the issue of abortion, the sequence seems to be in favor of it. Popeye, after all, recommends that Olive “get rid” of the baby she doesn’t want. On the religious matter, London is pretty clearly ridiculing organized religion. One of the clerics is named “Nosebest.” And he is depicted as motivated by issues other than moral ones: without Satan, he proclaims, “we’re out of a job.” Which of these dubious matters got London fired? We’ve always assumed in was abortion. But the blasphemy is also pretty severe. And not even London knows whether the latter was any part of the thinking that got him canned. A few days after London was fired, he was interviewed at comic-art.com by Steve Ringgenberg, who asked the cartoonist to explain how the brouhaha came about. Turns out London had no warning that he would be treading forbidden ground; in fact, a previous mention of Roe v. Wade in the strip had lead him to believe the topic was acceptable. He’d done a gag where the Sea Hag uttered the words: “Drat! There goes Roe v. Wade.” Said London: “I didn't hear a peep out of the syndicate and since I always heard from them whenever they objected to any kinds of punchlines or other nonsense that I might have injected in the strip— which was seldom, but it did happen occasionally—I automatically assumed that Roe v. Wade was considered fair game by them and I proceeded to prepare a full-length story about the subject.” Excerpts for the rest of the interview—: Ringgenberg: That's the storyline that they recently found objectionable with Olive Oyl wanting to send back the baby she'd gotten? London: She didn't get a baby, she got a baby robot that she did not remember ordering from the Home Shopping Network. ... It was an allegory designed specifically to keep Olive Oyl's innocence intact, and it was designed primarily to lampoon all the misguided good intentions of all the characters concerned. Ringgenberg: Oh, so was it specifically, in your mind, a veiled reference to the whole abortion issue? London: Well, of course, but I knew that, I respect Olive too much to sully her reputation or her good nature, or anything else about her and I would never directly, I would never be that blatant where she's concerned. I've known her for many years and she's a fine woman, and a good Joe. ... Ringgenberg: Okay, so why don't you run down, as briefly as you want, exactly how did the syndicate notify you that your work was unacceptable and that you were being terminated? London: Well, in, you know, uh, they, I can, I can just tell you very briefly because it happened very briefly and very abruptly. They just, the editor, Jay Kennedy, just called me up and told me that they were unhappy with the storyline and I was fired. It was simple as that. Kennedy was an acquaintance from before he became comics editor at King. London knew him from Kennedy’s days at Esquire when London was drawing for “slick magazines” in the late 1970s. Ringgenberg: Now the strips in question, with this storyline, the syndicate just notified you that this stuff was unacceptable. Had they had any complaints from their client papers? London: Not that I know of, no. I never got anything but positive fan mail. Ringgenberg: So this was just the execs at King Features deciding they didn't like it? London: Well, yes. There was a rumor that I heard from somebody there that they'd been considering dismissing me for quite some time because they other plans for Popeye, but I just sort of, I just kind of ignored that. I was continually ignoring rumors like that because they're just rumors, and to concentrate on my work, and see that it improved. I just, uh, I think the only serious argument I had up there with somebody was one particular individual who no longer works there, who was the former head of the licensing department. At issue was the matter of royalties from a St. Martin’s Press reprint of London’s Popeye. London was not paid royalties. And although he acknowledges that King Features was within its rights not to pay him, he thought, since St. Martin’s had specifically asked for “a Bobby London book,” he was entitled to royalties. It was his name that was selling the book. Ringgenberg: Well, prior to this whole thing with the Olive Oyl storyline was Popeye doing all right in syndication? Had your work attracted more papers? London: It was, I'll tell you the truth, it was beginning to attract new clients when this dismissal happened. However, it was due more to word-of-mouth than any effort that the syndicate would make to promote it, and it had been. ... It's a strip that's slowly been losing papers since the creator died. That's pretty much the natural chain of events. You can look at Pogo or any other old strip where the creator passes away and that's bound to happen. And even when Bud Sagendorf left the daily because he had been with it so many years, people were used to seeing him. So naturally I expected some amount of readership loss, but I also expected new readers to be gained if enough people heard that I was doing it. And I think that that was beginning to happen. I think that I didn't underestimate my draw, my drawing power. No pun intended. There've been, in fact, a number of the papers, a number of existing client papers have already dropped it because I've left, so. ... Ringgenberg: Well, that's good. About how many papers is it running in, you think? London: They never told me, and I can only guess that it's about twenty-four, which is what they're telling the press, but I don't really know. This whole thing started when a client newspaper in Chicago insisted on running the cartoons in question, and a reporter called me and asked me what the story was and I had just been freshly fired at the time, so I just told him, and then all off a sudden I found, I found seven networks at my doorstep. Ringgenberg: So, what day did you actually find out you were fired? London: Friday the seventeenth. Ringgenberg: Okay, so it's about two weeks ago. London: Yeah, it all happened very fast. Ringgenberg: What's your opinion of King Features right now? London: No comment. (Laughter) Ringgenberg: Okay. London: You can just say, I'll be eating neither spinach nor fried chicken for some time to come, you know. I recommend going to comic-art.com/interviews/london.hm for the rest of the interview, which shifts to London’s Playboy cartoon, Dirty Duck (who Hugh Hefner insisted have a sex life; London complied and came to regret it). I ran into Jay Kennedy in the fall of 1992, months after the London firing, and I asked Jay if he wanted to add anything to the prevailing reports. King Features had been portrayed pretty universally as the corporate bad guy; so did he want to do anything to set the record any straighter? What was the syndicate’s side of the story? Kennedy declined to elaborate beyond the official statements that had been made at the time of London’s firing. He was fired because his work was no longer acceptable. Given the timing, it was assumed that the Bluto baby episode was the cause. And Kennedy said nothing to correct that impression. I had the sense, though, that Kennedy—whose involvement with underground and alternative press cartoonists was long and cordial—was a little embarrassed and very much wanted the whole thing to go away without further ado. If the abortion sequence were to run these days, probably nothing would come of it. Syndicated comic strips today have joked about a number of previously taboo’d matters. These are simply freer times. But in 1992, as London discovered, the leash had not yet loosened much. Okay: a little long for a “short review”; but the review part is short—the rest is history.

Alice in Comicland By Various; edited by Craig Yoe with an Introduction by Mark Burstein 176 8.5x11-inch pages, color; 2014 Yoe Books/IDW Publishing hardcover, $29.99 THE CRAFT OF MAKING BOOKS has lately undergone a sea change, inspired, as far as I can tell, by Chip Kidd (or Kidd Chip). Since what used to be “books” are now so widely available digitally in non-book form, the book publishing industry has become increasingly desperate to find ways to sell books. And, presto, Kidd and his entourage came up with a way: turn the book itself into an objet d’art, something conversation-inspiring to sit on your coffee table when having visitors. Used to be, a book was important for its content; now, it’s important for its package, which is an artifact to be admired and fawned over. When Kidd first started producing books with fancy cover-designs, I carped about it, saying the package was detracting from the content. More the fool me. I was harboring a decidedly old fashioned notion about what a book was. Nowadays, the idea is to make books to sell, and if the package will do it, lead on McDuff. The

volume at hand, like several recent Yoe Books, has a cute cut-out cover in the

Kidd manner: on display is that classic picture by John Tenniel of Lewis

Carroll’s celebrated Alice parting a curtain to get into Wonderland, but

through the parted curtain we see a cartoony Alice, not, as in the Carroll

book, the door to Wonderland that Alice holds the key for. Inside the book, Yoe has assembled a sprawling selection of the variety of Alice’s appearances in comic books. We see cartoon interpretations of Carroll’s work by George Carlson, Chad Grothkoph, Harvey Kurtzman and Jack Davis. Alice is given up-to-date adventures by Dan DeCarlo, illustrator George Muhlfield (“Alice on Monkey Island,” the longest story in the book), Dave Berg, and Alex Toth (for a little taste of terror). A contemporary Alice meets Superman, drawn by Sam Citron and Stan Kaye, and Little Max from Joe Palooka, drawn by Warren Kremer. In a couple Peanuts strips, Charles Schulz has Snoopy doing his Cheshire Cat’s grin trick. And Walt Kelly is represented by Albert giving a hysterically physical interpretation of “Jabberwocky” and by a five-page poem enacted by Humpty Dumpty, reproduced here for the first time from original art in Mark Burstein’s collection. And there’s a section reproducing the covers from many Alice comic books. The content is not encyclopedic: it’s a selection, judicious and appealing. Burstein, President of the Lewis Carroll Society of North America, supplies a learned introductory essay that connects Carroll’s Alice to the history of comics, starting with England’s William Hogarth and Thomas Rowlandson and passing through Switzerland’s Rodolphe Topffer and Britain’s Ally Sloper and Germany’s Wilhelm Busch with stops at Richard Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley (although he perpetuates the myth that the Yellow Kid acquired his name through an accidental application of yellow ink in printing one of his weekly adventures early on). “Carroll,” Burstein contends, “was very much alive during the time of the development of proto-comics and can himself be considered a progenitor.” Yoe then offers an orientation to the book’s contents with notes about some of the cartoonists represented. Among them, the aforementioned Muhlfield, who, after a short comics career, went on to become “a noted sports illustrator, poster artist, and painter.” And his Alice story was written by Serge Sabarsky, who graduated to become “an internationally known art dealer and leading authority on German and Austrian Expressionism. ... Because of his interest in Expressionist art, he may have influenced Muhlfield’s approach to Alice”—which he rendered in a expertly slap-dash manner. Yoe also observes the most direct connection between Carroll and comics by quoting Alice’s comment in the first paragraph of Alice in Wonderland: “What is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?” Saith Yoe: “Absolutely nothing.” The volume is sprinkled throughout with rare and wondrous pictorial fragments of Alice’s experiences in comics—altogether, an impressive volume for comics fans but especially for Alice enthusiasts, of which, no doubt, there are legions.