|

|||||||||||||||

Opus 332 (November 8, 2014). Most of this posting was written in October, and October is a big month in Pogo lore. I once, in feverish moment of questionable acuity, called the month Pogoctober in recognition of the months’ importance for Walt Kelly’s strip. Pogo the comic strip started in October 1948, but in Pogo’s first appearance, in Animal Comics No.1 (December 1942-January 1943), Pogo is looking at a calendar for October and declares it’s his birthday. But Pogoctober is unpronounceable, so I was quickly persuaded to give it up. Notwithstanding, this posting is full of Pogo—four new Pogo books are reviewed, three of them in copious detail. We also report on the San Francisco “Satire Fest” convention of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) and on Wonder Woman’s dirty little secret, and we view some of the earliest post-Midterm Election editorial cartoons (plus some about ebola and the White House intruder), and we review reprints of Ripley’s Believe It Or Not, a couple 75th anniversary books (Marvel and Batman), and a spectacular book of Puck color cartoons, and observe some comic strip landmarks in Luann, Mother Goose and Grimm, Hi and Lois, and Dick Tracy, plus reviews of comic books Men of Wrath, The October Faction, Batgirl No.35 and Detective No.35. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Annual “Great Pumpkin” Show Ends in Steamy Sex Superhero Movies Glut Turkish Cartoonist Wins First Round Dirty Little Secrets About Wonder Woman

EDITOONIST CONVENTION: A SATIRE FEST Report on the San Francisco Convention of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC)

EDITOONERY Some of the best editorial cartoons on— Ebola White House Intruder and the Meaninglessness of the Midterm Election

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Mutt and Jeff Immortalized and Immutalized

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Anniversaries and Celebrations Luann’s 18th (and Surprises) Mother Goose and Grimm’s 30th Hi and Lois’ 60th Metaphysical Ending for Freshly Squeezed Dick Tracy Finds Little Orphan Annie after Five Months

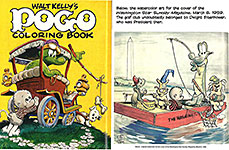

BOOK MARQUEE Short Reviews of— Zap Comix Reprint Marvel 75th Anniversary Magazine Marvel’s 75th Television Celebration Batman’s 75th What Fools These Mortals Be: Puck Cartoons Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Complete Pogo, Volume 3

BOOK REVIEWS Longer Reviews of— Walt Kelly’s Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics, Volume One Walt Kelly: The Life and Art of the Creator of Pogo We Go Pogo: Walt Kelly, Politics and American Satire

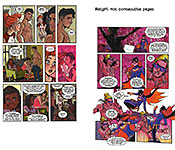

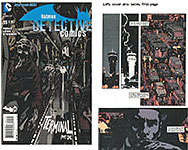

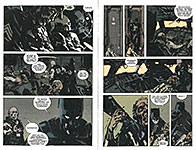

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Men of Wrath The October Faction Batgirl No.35 Detective No.35

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of the News That Gives Us Fits Before this year’s October 30 airing of the Peanuts Hallowe’en special, “It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown,” had stopped glowing on the tv tube, viewers—including all those eager-eyed moppets whose parents thought they’d treat their offspring to a nice kids program—found themselves confronted by the opening scene in “Scandal” in which Olivia Pope having a very explicit dream, reports Emily Yahr at the Washington Post — “reminiscing about sleeping with President Fitz (along with the other guy in her love triangle, Jake). It’s all set to ‘Summer Breeze,’ and there are glimpses of lots of bare skin.” The watchdog group Parents Television Council understandably went ballistic, unleashing an angry statement at ABC condemning the abrupt shift in kid-centric programming to eroticism. “After all, families are known to gather around the cartoon every year and may not have anticipated that they needed to quickly change the channel. Shame on ABC for putting a peep show next to a playground,” PTC President Tim Winter said.

SUPERHERO MOVIES GLUTTING UP From Brooks Barnes at the New York Times: On October 28, Marvel Entertainment announced a lineup of nine new movies that will reach theaters between now and mid-2019. The coming attractions include an entire films devoted to a female character, Captain Marvel, and to an African superhero, the Black Panther. After revealing the roster of films, that includes a two-part “Avengers: Infinity War,” Kevin Feige, president of Marvel Studios, told a packed El Capitan Theater here, “As you can see, we have a hell of a lot of work to do.” Shares of Marvel’s owner, the Walt Disney Company, promptly climbed 2 percent, closing at $89.93. Investors like long-term film-franchise building because it greatly lessens the risk of fluctuations in studio financial results. Marvel’s announcement came two weeks after DC Entertainment, a division of Warner Bros., unveiled its own roster of nine new superhero films (with single films for Aquaman, Wonder Woman and Green Lantern). Add the Marvel and DC slates to plans by other studios to keep mining the comic book genre, and Hollywood is on track to deliver 29 superhero movies in the next six years. Can the marketplace absorb the glut? Some media analysts warn that superhero fatigue is already setting in, but Feige brushed aside concerns. “If the movies deliver in terms of quality, they will succeed,” he said. The new Marvel movies for 2016 are “Doctor Strange,” which is expected to star Benedict Cumberbatch, and “Captain America: Civil War,” which will co-star Robert Downey Jr. as Iron Man and introduce Chadwick Boseman as the Black Panther. Following, in 2017, will be “Guardians of the Galaxy 2,” “Thor: Ragnarok” and “Black Panther.” In 2018, Marvel will release the first of the two “Avengers: Infinity War” movies; “Captain Marvel,” based around a not-yet-cast superheroine named Carol Danvers, who has cosmic powers; and “Inhumans,” a film that Feige said would introduce “tons” of new characters and is envisioned as “a franchise and perhaps a series of franchises.” Feige said a version of this splashy announcement event — taking the stage were Downey, Chris Evans, who plays Captain America, and Mr. Boseman — was supposed to have happened at Comic-Con International in July. But Marvel decided to wait in part to see how audiences responded to the unknown characters in “Guardians of the Galaxy,” which arrived in August. It now ranks as the year’s No.1 domestic movie.

TURKISH CARTOONIST WINS FIRST ROUND From Milana Knezevic at indexoncensorship.org: Last time (Op.331), we reported that Turkish cartoonist Musa Kart went to trial October 23, facing the prospect of spending nine years behind bars, simply for doing his job—which, in this case, involved making a critical (alleging criminal conduct) caricature of Turkey’s President (and former Prime Minister) Recep Tayyip Erdogan that was “insulting and slanderous.” Commenting on Erdogan’s alleged hand in covering up a high-profile corruption scandal, the cartoon depicted him as a hologram keeping a watchful eye over a robbery. Almost at once, Kart was acquitted, due in no small part to the swift reaction from colleagues around the world who gave Kart’s situation international headlines. “In the online #erdogancaricature campaign initiated by British cartoonist Martin Rowson, his fellow artists shared their own drawings of the president. With Erdogan reimagined as everything from a balloon to a crying baby to Frankenstein’s monster, the show of solidarity soon went viral.” “This campaign has showed me once again that I m a member of world cartoonists family. I am deeply moved and honoured by their support,” Kart told Index in an email. The rest of the Index article follows in italic): Kart has been battling the criminal charges since February. His defiance was clear for all to see when he told the court on Thursday [perhaps October 30; it’s not clear in the Internet dispatch] that “I think that we are inside a cartoon right now,” referring to the fact that he was in the suspect’s seat while charges against people involved in the graft scandal had been dropped. He remains defiant today: “Erdogan would have either let an independent judiciary process to be cleared or repressed his opponents. He chose the second way,” Kart said. “It’s a well known fact that Erdogan is trying to repress and isolate the opponents by reshaping the laws and the judiciary and by countless prosecutions and libel suits against journalists.” This isn’t the first time Kart has run into trouble with Erdogan. Back in 2005, he was fined 5,000 Turkish lira for drawing the then-prime minister as a cat entangled in yarn. The cartoon represented the controversy that surrounded Turkey’s highest administrative court rejecting new legislation that Erdogan had campaigned on. “I have always believed that cartoon humour is a very unique and effective way to express our ideas and to reach people and it contributes to a better and more tolerant world,” Kart explained when questioned on where he finds the strength to keep going. It remains unclear whether the story ends with this latest acquittal decision. While the charges against Kart were dropped earlier this year, an appeal from Erdogan saw the case reopened. “Erdogan’s lawyers will…take the case to the upper court,” Kart said. Kart’s experience is far from unique; free expression is a thorny issues in Erdogan’s Turkey. In the past year alone, authorities temporarily banned Twitter and YouTube and introduced controversial internet legislation. Meanwhile journalists, like the Economist’s Amberin Zaman, have been continuously targeted.

DIRTY LITTLE SECRETS About Clean Living and the Wonders of Woman Power Jill Lapore, a writer who sometimes appears in The New Yorker, has written a book with the seductive title The Secret History of Wonder Woman. Melissa Maerz, a writer who appears, in this case, in Entertainment Weekly, reviews the book in the October 24 issue. She thinks the book is “a great read. It has nearly everything you might want in a page-turner: tales of S&M, skeletons in the closet, a believe-it-or-not weirdness in its biographical details, and something else that secretly powers even the most ‘serious’ feminist history—fun.” But there’s a sneaky element of snark in parts of Maerz’s review. William Moulton Marston, the creator of WW, had a secret life that he never revealed to the public. “Lepore,” says Maerz, “is particularly savvy at pointing out Marston’s contradictions. He invented the lie detector test but was also a liar who claimed that his girlfriend, Olive Byrne, was a blood relative. He considered women to be mentally stronger than men but insisted that they’re happiest when they’re submissive. (There’s the reason Wonder Woman always gets tied up: Marston had a thing for bondage.) His comics showed her calling for her mortal sisters to fight off their male oppressors, but in his more scholarly publications, he may have taken credit for research conducted by his wife, Elizabeth Holloway. “After he forced his wife to let his mistress move in with them,” Maerz goes on, “Holloway passed off the child rearing to Byrne and forged a career as a lecturer [on feminist issues mostly] and editor at a time when women were discouraged from working.” Well, not quite. Lapore got her innings in The New Yorker’s September 22 issue, where she provides a condensed version of the book, or, at least, some of the juiciest bits of it. Wonder Woman, Lapore asserts, has a backstory that “is taken from feminist utopian fiction,” and she was inspired by Margaret Sanger, a crusading feminist and birth control advocate who opened the first birth control clinic in 1916 and who, “hidden from the world, was a member of Marston’s family.” Marston married Holloway in 1915 and, while teaching at Tufts in 1925, met and fell in love with a student, Olive Byrne, daughter of Ethel Byrne who, coincidentally, was Sanger’s sister (and another feminist). Marston, Holloway and Byrne began attending an avant garde sexual “clinic” at the Boston apartment of Marston’s aunt, where they learned about “Love Units” formed by a Love Leader, a Mistress, and a Love Girl. (Sexual adventurousness was apparently a family trait: Olive’s uncles were female impersonators on the vaudeville circuit.) In 1926, Byrne, then 22, moved in with Marston and Holloway, and they lived as a threesome, “with love making for all” as Holloway put it. Four children were born of this array, two by Holloway and two by Byrne. But Holloway was scarcely “forced,” as Maerz has it, to accept Byrne into the household. For Holloway, Lapore writes, “the arrangement solved what, in the era of the New Woman, was known as the ‘woman’s dilemma’: hardly a magazine was sold, in those years, that didn’t feature an article that asked, ‘Can a Woman Run a Home and a Job, Too?’ ... The question is no longer should women combine marriage with careers, but how? Here’s how,” Lapore continues: “Marston would have two wives. Holloway could have her career. Byrne would raise the children. No one else need ever know.” The three assiduously kept their domestic arrangement a secret. The two women were apparently not only friends but colleagues in feminist enterprises. After Marston’s death in 1947, “they lived together for the rest of their lives. In the fifties and sixties, they often stayed in Tucson, taking care of Sanger. Byrne worked as Sanger’s secretary.” In 1937, the year the American Medical Association finally endorsed contraception, Marston, who was mostly unemployed through the decade (and even when employed, it was never for very long at any of the universities he taught at), held a press conference, Lapore reports, at which “he predicted that women would one day rule the world.” His prediction made headlines all across the country. In

1940, M.C. Gaines, whose DC comics published Superman, Batman and a host

of other colorfully costumed superheroes, read an article by Olive Byrne in Family

Circle magazine, wherein Byrne reported that, contrary to some popular

criticism of the day, Marston found comic book superheroes “pure wish

fulfillment” of the most beneficial sort. Gaines soon hired Marston as a

consultant, and Marston convinced him of the need for a female superhero. Enter

Wonder Woman. “Drawn by an artist named Harry G. Peter, who, in the nineteen-tens, had drawn suffrage cartoons, Wonder Woman looked like a pinup girl. She’s Eleanor Roosevelt; she’s Betty Grable. Mostly, she’s Margaret Sanger.” And, possibly, Olive Byrne. Saith

Lapore: “In 1974, when a Ph.D student asked Holloway about Wonder Woman’s

bracelets, Holloway replied: ‘A WW’s costume didn’t last even that long before various tinkerers began tinkering. And I reacted as you see here.

Fascinating Footnit. Much of the news retailed in the foregoing segment is culled from articles eventually indexed at rpi.edu/~bulloj/comxbib.html, the Comics Research Bibliography, maintained by Michael Rhode and John Bullough, which covers comic books, comic strips, animation, caricature, cartoons, bandes dessinees and related topics. It also provides links to numerous other sites that delve deeply into cartooning topics. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

QUOTES AND MOTS It is often said out here in these Western parts that owning a gun is a way of life. Not so. It’s a way of death, West or East.—RCH Home is where the fart is: only in your own home, can you fart at will and as loudly as you want without apology.—RCH If you’re looking for absolute complete freedom, do exactly as the authorities and social mores and morals of the times dictate. You’ll be completely inconspicuous and therefore free to do whatever you want.—RCH

EDITOONIST CONVENTION October 9-11, in San Francisco For three days, the SF in San Francisco stood for “Satire Fest,” editoonist/organizer Mark Fiore’s happy contrivance aimed at opening up to the general public all aspects of the annual convention of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC). Online promotion urged interested ordinary citizens to “celebrate the power and fun of visual satire.” The AAEC showcased of some of the best satirical talent at a time when, from the “Daily Show” to traditional print political cartoons to Congress and city hall, “satire is everywhere. Events,” the website continued, “will range from Pictionary-style ‘draw-offs’ to hands-on tips about making a living doing something as unique as visual satire. There will be performances, pictures and politics from left, right, center, up and down. And it must’ve worked. Registered attendance by AAEC members totaled 71 (the usual total lately), and other fans of satire from the civilian population added another hundred or so to the crowd, enough to make the Marine’s Memorial Theater meeting site on Sutter Street look nicely populous. On stage, the parade of presenters included several nationally-known cartoonists who weren’t first and foremost editoonists but who were crowd-pleasing satirists nontheless— Pearls Before Swine’s Stephan Pastis, political satirist Will Durst, The Knight Life’s Keith Knight, etc. AAEC

prez Fiore filled the schedule with program sesssions from 9 am until 5 pm

daily, allowing only a few minutes for a stand-up “light lunch” to be picked up

at the bar in the Theater foyer. Presenters so eagerly embraced their

assignments that every session ran long, and by noon every day, the program was

at least 30 minutes behind schedule; by the end of the day, we were behind an

hour. But we were all having such a good time that no one complained. The program included a healthy dose of sessions that introduced to traditional paper-and-ink-in-print cartoonists new ways of making a living with satire in the digital age. To poach from Fiore’s program notes: Matt Bors from the online Medium where he edits the cartoon section, The Nib, and Zach Weinersmith, who has build his own cartoon empire, discussed their enterprises. Unhappily, Bors left his cartoons on the screen for too short a time: they were unreadable. Bors was ill and perhaps wanted to get off the stage as quickly as he could manage. Weinersmith, who had no excuse, mumbled a good bit and fussed with his shoulder-and-longer-length hair. But this session was the sad exception to the general run of engaging and informative presentations. Funding Internet entrepreneurial efforts was the subject with Patreon’s Tyler Palmer, Weinersmith, and Susie Cagle (and Keith Knight, who joined them briefly before Skype skipped out). Several achieve incomes by crowd-funding—asking regular Web viewers to “subscribe” or to make donations to keep their projects going. Knight Fellow, Gus D'Angelo, showed a way to tailor editoons to mobile platforms. Smart phones, he said, offer too small a display space for fitting a static visual square into a mobile hole, so he opts for interactive animation by incorporating into political commentary the kind of suspense fostered by game-like features that propel a storyline. In one sequence (which can be seen at comigama.com, Uncle Sam is standing guard at the border while little kids run across the dotted line. The viewer can manipulate Sam, moving him up and down the border so he can catch a kid every now and then. And when he does, he kicks the immigrant back across the border into the land from which he was fleeing. The unending cycle suggests that Sam’s solution here is no solution at all. In another (by Pulitzer-winning Mark Fiore), we learn “how to find a terrorist in your neighborhood.” In a succession of Arab-looking faces, all looking like fierce terrorists, we find a cab driver, a doctor, and other ordinary workers before seeing one face labeled “terrorist.” The satiric comment: you can’t tell terrorists by their appearance. At

the same session, Dan Archer, a fellow at the Reynolds Journalism Institute and

ongoing pusher-of-interactive-boundaries, created a 3-D playlet of the Ferguson

tragedy in which the viewer is “there” on the street where Michael Brown was

killed and left dead for hours. Back to Fiore’s program notes, we learned “survival skills” in the social media landscape from Jeff Lakusta, a comic book author who works for Google and is an expert in all things social, and Reza Farazmand, who makes a living drawing his webcomic, Poorly Drawn Lines. Under the heading “Graphic Journalism, Cartoon Reporting, Comics Journalism et al,” we heard from Susie Cagle, Dan Carino, Jack Ohman, Andy Warner, Stephanie McMillan, Dan Archer, and Patrick Chappatte. Chappatte, born in Pakistan to a Lebanese mother and Swiss father, was raised in Singapore, lives in Switzerland and is published twice weekly in the International New York Times. His most recent cartoon reportage covered the war in Gaza (2009), the slums of Nairobi (2010) and gang violence in Central America (The Other War in Guatemala City, 2012). He went to southern Lebanon in 2009, where people still live with the threat of actual time bombs, producing a report in comic-book format, Death in the Field, later released in 2011 as an animated documentary. Warner reports statistics through visuals, and McMillan often covers protest movements, sometimes in graphic novel form. Ohman, who considers himself more a writer than a cartoonist, produces a weekly commentary comic strip on current events and political shenanigans for his paper, the Sacramento Bee, where, the rest of the week, he draws editorial cartoons of the typical one-panel sort. In a session called “Off the Walls: Cartoon Satire and Social Commentary in Museum Exhibitions,” we got a glimpse of museums where cartoons festoon the walls from Jenny Robb (Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum), Andrew Farago (Cartoon Art Museum), and Corry Kanzenberg (Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center). Robb spoke of two current exhibits at the Billy Ireland: “The Long March: Civil Rights in Cartoons and Comics” presenting the story of the civil rights movement through original editorial cartoons, comic strips, and comic books, including artwork from Congressman John Lewis’ bestselling graphic memoir, March, about his experiences as a civil rights leader; and “Will Eisner: 75 Years of Graphic Storytelling,” which, in addition to sampling his iconic Spirit strip also features art from several of his graphic novels as well as selections from his student days and his early work as a commercial artist. Both exhibitions run through November 30. And Hollywood joined us for a session with “The Simpsons” director David Silverman and Lalo Alcaraz, creator of the syndicated comic strip La Cucaracha who now writes for Seth MacFarlane's new Fox show, “Bordertown.”

THE FESTIVITIES were not without moments of high comedy, among them—political satirist Will Durst interviewing Stephan Pastis and vice versa. Pastis told stories about his various run-ins with his strip’s readers, whom he seems (albeit without intending it) to insult or outrage regularly. Part of Pastis’ inspiration for such assaults on civilized sensibility comes from the traditional, hide-bound stodginess of newspaper editors, who have dedicated their professional lives to preventing comic strips from offending readers. Cartoonists can’t say “sucks” in a comic strip. Nor can any strip character say “screw.” Until, that is, October 5 this year, when Pastis induced one of his characters to say, to another, “Screw you.” Newspapers

were given a choice, Pastis explained: he offered an alternative, “Nuts to you,”

which, he reported, most papers chose. My hometown paper, the Denver Post, thankfully eschewed nuts for screw. But the most excitement Pastis provoked was when he named a llama Ataturk, only vaguely realizing that Ataturk was the founder of modern Turkey and is regarded as a saint by his countrymen. Pastis wanted to make fun of the fact that llamas spit when they get angry, and, to enhance the comedy, his llama was cast as a diplomat. Ataturk the llama initially escaped unscathed, but when Pastis confessed via e-mail to a reader that he didn’t know much about the Turkish hero and had selected the name Ataturk just because it sounded funny, he made the front page of the largest Turkish-American newspaper in the country. Making fun of Ataturk, Pastis found out, is a crime in Turkey, punishable by ten years in prison. Pastis was flooded with e-mails—among them, one from the Turkish ambassador to the United States, who, in a six paragraphs, demanded that Pastis apologize. Pastis did, after the usual manner of saying “sorry” without actually apologizing : “I said I was sorry for the offense, but there was no harm intended.” Crowning

the evening of the first day was another episode in the notorious Literary

Death Match, which, under the watchful eye and verbal goad of founder Adrian

Todd Zuniga, pits competing cartoonists against each other in performing a

reading or telling a joke—or some such. Judges, which this year included Ron

Turner, founder of Last Gasp, the infamous Will Durst and dry witted standup

comedienne Clara Bijl, rated the competitors on literary merit, performance,

and “intangibles.” Except an appearance that evening by Sikh cartoonist Vishavjit Singh, who talked about (and illustrated with photographs) his adventures impersonating Captain America in Time Square, where he appeared in the proper uniform except for his turban and long, straggly beard (Sikh uniform).

THE PROGRAM WENT INTERNATIONAL several times. At one session, several Cuban cartoonists—Adam Iglesias Toledo (who signs himself Ada), Humberto Lazaro Mirando Ramirez (Laz), Carlos Alejandro Falco Chang (Falco) and Gustavo Rodriguez (Garrincha, now editooning in Miami)—and one from Pakistan, Sabirnazar Sabir, told of their adventures and misadventures under repressive governments with no senses of humor. Sabir reviewed some of the obstacles to straight-forward cartoon commentary in his country—both government and religion frown on comedy that pokes fun at their institutions, and blasphemy laws inhibit much satiric content. One

session spotlighted Canadian cartoonists. Terry Mosher (who signs his work

Aislin) did most of the talking, but he was accompanied on stage by Guy Badeaux

and Dan Murphy (author of 101 Uses for a Severed Penis), whose work was

often displayed on the screen behind them as Mosher discoursed about

beautifully cruel but laughably insightful caricatures and cartoons that barely

got into print. Australia

took a turn on stage, too—with cartoonists David Rowe of Australian

Financial Review and Rod Emmerson of the New Zealand Herald, joined

by Chappatte. With the local audience in mind, another session spotlighted California cartoonists—Jack Ohman of the Sacramento Bee, Dave Horsey of the Los Angeles Times, Tom Myer of the San Francisco Chronicle, and Ted Rall, who cartoons for the LA Times from New York. An aspect of the Bay Area’s “long and colorful history of comic album art and rock posters” was featured in a session with famed underground cartooner Paul Mavrides, co-creator (with Gilbert Shelton) of the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, Dan Perkins (aka, Tom Tomorrow of This Modern World), who created the album art for Pearl Jam's "Backspacer" release, punk rock poster artist Paul Imagine and the prolific John Seabury. This session was followed by a blast of rock music from a three-“man” band of what looked like 10-12 year-olds, who were astonishingly professional and suitably loud—accompanied at two easels by a contingent of their youthful colleagues and, at the other easel, a clutch of grown-up visual pranksters, who tried to interpret pictorially what was assaulting their ears. No

convention of editorial cartoonists could be complete without a session devoted

to the fine arts of caricature. Master caricaturists included Kevin Kallauhger

(KAL) of The Economist, Zach Trenholm, and Ed Wexler. In the same vein, every day’s program included sessions with cartoonists at easels, competing for laughs and applause. On the first day, left-leaning editorial cartoonists Rob Rogers and Ted Rall were pitted against Scott Stantis and Chip Bok, representing the Right. Emcee Mike Capozzola proposed a situation, and the cartoonists were given 60 seconds to produce a cartoon. On the second day, Cubans faced American cartooners Lalo Alcaraz, David G. Brown and Dave Horsey tackling the relationship between the two countries. In the third session at easels, Capozzola simply offered a contemporary political situation, and Cullum Rogers, Joel Pett, and Jack Ohman (among others, whose names, alas, I neglected to jot down) unsheathed their markers.

It was great fun watching cartoonists thinking on their feet, no small feat. Sometimes one cartoonist would start to draw, and another, picking up on the idea, would chime in, adding detail to the drawing even as the first cartoonist continued drawing. The convention’s grand finale was Saturday evening’s “Cartoonapalooza!” during which a notable gaggle of cartoonists showed off their wares—Tom Meyer, longtime San Francisco Chronicle cartoonist, Dan Perkins (aka, Tom Tomorrow), creator of This Modern World, Keith Knight of K Chronicles fame, award-winning cartoonist Jen Sorensen, cartoonist and author Ted Rall, Chicago Tribune political cartoonist and syndicated comic strip artist Scott Stantis and Pulitzer Prize-winning political animator, Mark Fiore—emceed occasionally by standup comic, Johnny Steele. The

evening concluded with award presentations. The Cartoonist Rights Network

International presented its Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award to two

cartoonists this year— Indian Kanika Mishra and Palestinian Majda

Shaheen, the first women ever to win the award; see Opus 329 for more about

each winner. Only Mishra was able to attend to receive the Award in person. The college cartoonist receiving the John Locher Memorial Award for outstanding creativity, Andrew David Cox of The Appalachian at Appalachian State University, expressed his gratitude, and Jenny Robb expressed her utter surprise—and gratitude—when presented with AAEC’s Ink Bottle Award for dedication to the spirit of the profession. The convention wandered the San Francisco landscape from time to time. The opening reception on Wednesday took place along Fisherman’s Wharf at Pier 39's Aquarium of the Bay with finger-food and drinks and music amid large glass tanks of water containing fish and otters and various other under- and over-water creatures. Thursday ended at the Cartoon Art Museum with more finger food and drinks (and the Literary Death Match). On Friday, everyone boarded a boat to cruise San Francisco Bay at sunset while finger-fooding and drinking. I didn’t go on this one: after two days of buffet dining, I needed to sit down and eat, and to that end, I returned to one of my favorite San Francisco restaurants on North Beach. The next morning, reports about people being thrown overboard during the sunset cruise seemed greatly exaggerated. It was also rumored that Fiore leaped into the freezing water and led a contingent of the like-minded on a swim to Alcatraz. But because they haven’t been seen since, the rumor can not be verified. On

Sunday, many of the survivors of the previous three days boarded a bus, which,

after a 25-minute delay to permit Dave Horsey (who overslept) to pack his

suitcase and check out of the hotel, motored to Santa Rosa, where, at the

WHEN I GO TO

SAN FRANCISCO, I always do four things. I may do more than four things (I

usually do), but these four things are sacred. I take the Powell/Hyde cable-car

to the end of its line and enter the Buena Vista Café right across the street.

There, I have at least two Irish coffees while gazing out over the Bay. The

“BV” (as it is known among the cognoscenti) opened in 1886, and since then, it

has survived the 1906 earthquake, the Great Depression, and (significantly)

Prohibition. The BV claims to have introduced Irish coffee to this country in

1952. I wouldn’t dispute it. Particularly after imbibing a couple samples

(which, as I say, I always do). That’s two things: ride a cable-car, drink

Irish coffees at the BV. The third thing I always do is visit Kayo Books on Post Street. It specializes in vintage paperbacks and magazines. I browse. I buy. I go home happy. The fourth thing is to “follow my nose to the Stinking Rose,” a garlic restaurant on North Beach. “We season our garlic with food,” they say. And it always comes out delicious.

BEFORE WE

WANDER OFF in another direction, here are three more cartoons by participants

in the Satire Fest. Across the top, a comic strip that was part of Visha’s

Sikhtoons’ assault on the Indian government for failing to react to suppress or

control murderous riots that killed Sikhs in the wake of the assassination—by

her Sikh bodyguards—of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1984. “While Sikhs were

being hunted and killed,” Visha writes, “the political and security leadership

had a long conversation about when to call the army in to put an end to this

organized game of revenge.” The long conversation is cannily depicted in the

cartoon (“long” assuming a double meaning). Below Visha’s cartoon is one of Jack Ohman’s weekly specials—a long-form (comic strip) editorial cartoon discussion of some current event or political personality. Or, in the case at hand, a political poseur. Then we have a cartoon by Garrinhca (Cuban Gus Rodriguez), which, characteristically with his work, makes potent use of visual materials.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST From The Week: Australian swimming legend (winner of nine Olympic medals) has finally come out as gay. For years, he maintained he was straight and had a long-term, long-distance relationship with fellow swimmer Amanda Beard. But now he’s fessed up. Her name is Beard? Really?

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, the highly touted and otherwise meaningless midterm election will be over. And we’ll know—what? Here (in italics) is what Slate columnist John Dickerson said about it a few days before it commenced (and what he says remains true even after it’s over): Republicans are going to pick up seats in both houses of Congress. They may even take control of the Senate. Those victories will provide an unequivocal mandate for support of one proposition: widespread dislike of President Obama. That’s it. More than $4 billion will be spent on the 2014 campaign and, when it’s over, that will be the message on the little slip of paper that emerges from that huge machine of activity. This year’s contest is a no-mandate election in which the winning side will succeed with no great animating idea other than the fear (or avoidance) of the Obama nightmare. Republican debates, speeches, and advertisements have been so thoroughly concerned with the president and how much the Democrat on the ballot agrees with him, there is no other message that competes. ... In Arkansas, Republican Senate candidate Tom Cotton said Obama’s name 74 times in his 90-minute debate against Senator Mark Pryor. ... In North Carolina, [Karl Rove’s] Crossroads is running an ad where a child is asked to spell the name of the Democrat incumbent, Senator Kay Hagan: “Hagan, O-B-A-M-A,” says the little girl. “Close enough,” say the three judges. ... That’s a smart political strategy, but it’s not a governing strategy. Republicans may take control of Congress, but it will have been by clobbering a president they’ll then have to work with at a time when a majority of Americans say they want leaders in Washington to compromise. Syndicated columnist Kathleen Parker, a conservative-leaning pundit, said about the midterm election when it was still forthcoming: “There’s nothing like a few beheadings to put things in perspective. Thus, I suspect that a ballot cast in the midterms is less a vote for a person or policy than it is a vote against the void so many perceive in the presidency. When two of the four horsemen of the biblical Apocalypse come galloping out of Hell’s gate—Death/Ebola and War/Islamic State—one can hardly rely on the hopers to sort things out. It’s doer time. Or, Dewar’s, if you please.” With “hopers,” she evokes memories of Obama’s “hope and change” platform of 2008. She’s right, though: Dewar’s is what we all need but not because of Bronco Bama. Meanwhile, as of this writing (Friday, October 31—the night of spooks and ghouls), the contest ensues without pause, full of little more than rancor and groveling self-interest. Nothing else is on the agenda. And when it’s over, as Dickerson says, the bi-annual convulsion will have proved nothing, established nothing, and changed nothing. There’ll be no indisputable winner—except the gasbags and political pundits whose livelihoods depend mostly on how much viewership they can generate by stirring up endless controversy. Regardless of the outcome of this election—that is, which party winds up in control of the Senate, the only real consequence the election offers—nothing is likely to change in Washington. Gridlock is a way of political life there, and both parties are living it. Obama’s non-role in the election—his being the target of all GOP attacks without any shred of support from his own party—is shameful, disgraceful and disgusting. Sadly for the sake of American democracy, for too many people this behavior in opposition is noble and principled. And, often, racist. Obama’s treatment also speaks to how timorous the Democrats have become: they’re afraid to run on their record. No surprise: the Dems have accomplished little in a Congress holding the record for the least activity of any Congress in history. And it won’t do much more in the time remaining to it: it has been in session for only 8 days since the end of July, and it isn’t going back to work until mid-November, just in time for a Thanksgiving recess. But the Democrats, instead of denying Obama, could have run on his achievements, which, surprisingly (but only if you are listening only to the pundits and prognosticators) are considerable. New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, one of Obama’s most notable critics, assessed the Prez’s performance in a special article in Rolling Stone (October 23). “Obama faces trash talk left, right ands center—literally—and doesn’t deserve it. Despite bitter opposition, despite having come close to self-inflicted disaster, Obama has emerged as one of the most consequently and, yes, successful presidents in American history. His health reform is imperfect but still a huge step forward—and it’s working better than anyone expected. Financial reform fell far short of what should have happened, but it’s much more effective than you’d think. Economic management has been half-crippled by Republican obstruction, but has nonetheless been much better than in other advanced countries. And environmental policy is starting to look like it could be a major legacy.” On national security—“Even if Obama is just an ordinary president on national security issues, that’s a huge improvement over what came before and what we would have had if John McCain or Mitt Romney had won. It’s hard to get excited about a policy of not going to war gratuitously, but it’s a big deal compared to the alternative. ... “Am I damning with faint praise? Not at all. This is what a successful presidency looks like. No president gets to do everything his supporters expected him to do. FDR left behind a reformed nation, but one in which the wealthy retained a lot of power and privilege. On the other side, for all his anti-government rhetoric, Reagan left the core institutions of the New Deal and the Great Society in place. I don’t care about the fact that Obama hasn’t lived up to the golden dreams of 20008, and I care even less about his approval rating. I do care that he has, when all is said and done, achieved a lot. That is, as Joe Biden didn’t quite say, a big deal.” And Krugman isn’t the only one tallying up Bronco Bama’s achievements. Time says: “Obama has enacted much of his agenda. He engineered a massive stimulus bill, record investments in clean energy, ambitious school reforms and sweeping Wall Street reforms. And his Affordable Care Act became the law of the land, a major step toward the long-standing Democratic dream of universal health insurance.” Well, Krugman said it all before. But it bears repeating, especially since it refutes the lies that Republicons have been routinely telling. But enough. Let’s get to the jokes. The election jokes are at the end.

APART FROM REPORTING with deadening regularity the continuing (and, bit by bit, successful) attempts to enlist other countries in the war against the Barbarian Califate in Iraq and Syria, the news of October was confined, more-or-less, to three general areas: whatever the polls said about the midterm election, the ebola outbreak in the United States (four cases, one death), and, with a dedication that would be enviable were it devoted to, say, raising the minimum wage, Omar Gonzalez’ successful invasion of the White House by jumping the surrounding fence and eluding a sleepy band of Secret Service agents. We’ve disposed of the first with our opening rant in prose. Cartoonists seemed too bored by it to draw pictures about it; and, indeed, there was about it a paralyzing monotony. Steve

Sack’s cartoon at the upper left on our first visual aid gets us into the

ebola fiasco. Going clockwise, Jack Ohman gives us a short lesson in the evils of news media enthusiasm, and Cam Cardow continues in the same vein just below Ohman’s acute reading of the communication airwaves. So-called daily journalism did not perform well. The first stories about Thomas Duncan’s hospitalization in Dallas reported that he had sought medical aid and had been told to go home just a few days before he become so ill that he returned at which time the facility admitted him. Terrible. Wasn’t it enough of an alert during his first visit that he was recently in West Africa? Shouldn’t someone he talked to have picked that up? Yes, but subsequent reporting (I watched Scott Pelley on “60 Minutes”; he interviewed several of the nurses) revealed that Duncan had failed to make it clear that he had just left an ebola-infected country. And his temperature, at first high, had soon subsided, indicating that he wasn’t ill. So the hospital wasn’t as incompetent as the news reporting. Still, Nate Beeler at the lower left had sufficient justification for depicting CDC with its pants down, a classic and highly laughable image of unpreparedness. But I can’t leave the topic without quoting Michael Che, who said, during “Weekend Update” on “Saturday Night Live”: “According to officials at the CDC, the first case of ebola in the U.S. has been diagnosed in Texas. And according to WebMD, you already have it.” The

laxity of the Secret Service security at the White House is the topic in our

next round of visual aids. Next on the clock, Steve Benson produces a different version of the same dotted line—this time as a sort of map, an image direct and unencumbered and unmistakable. And Cam Cardow resorts to one of the most familiar dotted lines in comics, borrowing Billy from Bil/Jeff Keane’s Family Circus cartoon. All good clean innocent fun so far, and then we get to Jerry Holbert’s offering. The imagery in his cartoon turns the implicit threat of the White House interloper on its head, making the menace ludicrous: here’s the invader, taking a bath in the presidential bathroom. But when Holbert added words to his image, the cartoon turned unexpectedly toxic. The association of watermelon with an African American conjures up racist notions of black plantation populations that were so simple-minded that they were kept happy (and enslaved) by providing them with such unpretentious pleasures as eating watermelon. Saith Wikipedia: “The stereotype was perpetuated in minstrel shows that often depicted African Americans as ignorant and workshy, given to song and dance and inordinately fond of watermelon.” In short, to associate watermelon with African Americans is to invoke slavery and to suggest that African Americans are as simple-minded as uneducated slaves (and probably would be better off back on plantations). The floodgates of protest opened at once as soon as the cartoon was published on Wednesday, October 1, and, as Alan Gardner said, the use of the watermelon “placed Holbert in an awkward position of either admitting he created a cartoon with a historically racist reference OR plead ignorance of the connection between watermelon and African Americans such as President Obama. Jerry went with ignorance.” Holbert’s newspaper, the Boston Herald, issued a statement expressing its regret but standing behind Holbert as a cartoonist of “utmost integrity. ... His cartoon satirizing the U.S. Secret Service breach at the White House has offended some people and to them we apologize,” the statement went on. “His choice of imagery was absolutely not meant to be hurtful.” Then Holbert went on Boston Herald Radio to explain himself. The idea to use watermelon as the flavor of the toothpaste came after he looked through a cupboard and discovered someone had left “a kids Colgate watermelon flavor toothpaste tube” there. He simply failed to recall the racist stereotype. "I didn't think people thought like this anymore. I am just thinking about the flavors, and I love watermelon," Holbert said. “It’s been a very long time [since I’ve heard the stereotype usage]. ... Maybe when I was a kid? It’s been so long—it has to be forty years since I’ve heard that.” He went on: “I also apologize to anyone I offended. It was not my intention at all. I don’t think along the lines of racial jokes. I never do. Naive, stupid—those kinds of things I understand. But racist, I am definitely not.” But the Boston branch of the NAACP was not amused. President Michael A. Curry said ignorance was no excuse: “That’s unacceptable in 2014 that someone doesn’t know American history or culture enough to be a cartoonist or a reporter and avoid those stereotypes.” And State columnist Donnell Probst heaped sarcasm on Holbert’s head: “It seems as though Holbert expects his readership to accept that he, a political cartoonist who has spent the better part of three decades working for one of the oldest daily newspapers in the country and presumably stays abreast of current events as a requirement of his position, failed to see any media coverage of watermelon references made about Obama, as well as other African-American officials over the past decade. “What about the story of a California mayor who sent out an email showing Obama’s White House lawn covered in watermelons? This story was covered by Fox News, NBC News, CBS News, Huffington Post and the Los Angeles Times, as well as numerous local news outlets. Yet somehow a Boston Herald editorial cartoonist scouring daily news developments to feed his political commentary missed this story altogether?” Still, Holbert had at least one highly visible defender. Whoopi Goldberg on “The View” allowed as how the cartoonist could, indeed, have been momentarily ignorant of the racist stereotype that watermelon suggests. I agree. I don’t go around thinking about watermelon as a way of denigrating African Americans. Probably Holbert doesn’t either. But then, he’s in the business of making public statements—ones that make extensive use of visual symbols— so he ought to have been more aware. But even if we give Holbert the benefit of the doubt, it turns out that he had been warned before the cartoon went into print. Holbert is syndicated by Universal Uclick, and his editor there, Reed Jackson, phoned him about the unfortunate watermelon as soon as he saw the cartoon. Later, Jackson, interviewed by Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs, elaborated: “When I saw the cartoon, the ‘watermelon’ flavor immediately stood out to me, for two reasons: first, the racial subtext that the line unintentionally introduced distracted from the cartoon’s point; and second, watermelon flavoring is only available in children’s toothpaste, so it would be a weird thing for adults to brush their teeth with.” For both those reasons, Jackson suggested to Holbert that he replace the flavor. The veteran cartoonist’s email reply made one thing evident to the editor: No racist slur had been intended. “Yes, he made it very clear via [email] that the racial element hadn’t occurred to him,” Jackson told Cavna. “He’d recently seen a tube of watermelon toothpaste and thought it was an odd flavor, and it stuck with him, so he included it in the cartoon. He was happy to change it. “I suggested something like ‘lime spearmint zest,’ but Holbert went with the simpler and more elegant ‘raspberry.’ ” And so in the cartoon as distributed nation-wide by Holbert’s syndicate, the intruder recommends raspberry-flavored toothpaste. Only in the Boston Herald was the toothpaste watermelon-flavored. “I feel awful about the perception that it was racist, but it was nothing of the sort,” Holbert said when Cavna phoned him. “I wanted another flavor of toothpaste for the cartoon, and we had a bottle of Colgate kids’ toothpaste that was watermelon-flavored … watermelon seems to be a big flavor these days, so…I went with it. It was a completely innocent attempt at humor, but it did not come across that way to some people. “I have said I am sorry for offending anyone,” he continued, “— I never intended to do that. I never even thought about the racial element. I wish I had, but I did not. A bit dumb on my part — I should have thought it through more.” And, once alerted to the watermelon bomb in his cartoon, he should have alerted his editor at the Herald. But he didn’t. I don’t know for sure about the timing of all this, but apparently Jackson phoned Holbert on Tuesday night, and the cartoon was in the works for Wednesday publication in the Herald. Holbert could have stopped it. But he didn’t. Perhaps he thought Jackson was being overly sensitive to the use of an “odd flavor” of toothpaste. “It was stupid on my part,” Holbert said. “But, you know, racism is sort of innately stupid, and I do not participate in that.” To compound the disastrous debacle, it turns out that none of Holbert’s editors saw the cartoon before it was published. Probably any of them, like Jackson, would have seen the racist implication of watermelon. Editorial page editor Rachelle G. Cohen explained that the normal process is for a final page proof of the editorial page to go “up to the 6th floor where a desk editor will read the editorials, make sure we haven’t made some obvious error of fact and in the event a topic has been overtaken by breaking news events will pick up the phone and advise me that we need an update. On the night in question — the night the cartoon appeared on a page proof, the proof was not left in the proper bin.” Big mistake, small explanation. Or, as Cohen writes, “So there you have it. The remarkably simple way in which bad stuff can happen.” So persistent was the protest over the cartoon, that Cohen offered another apology about two weeks after the event. And this effort was more heartfelt than pro forma: “A little over a week ago and just days after the cartoon appeared, it was Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, and so surrounded by friends I stood in temple and prayed for forgiveness. But there’s a footnote to all of those traditional prayers. It is that God can forgive for offenses committed against God — but not for offenses committed against another human being. For that we must seek forgiveness from those we have wronged. That is what I most humbly do now with all my heart.”

WE ABANDON

UTTER SERIOUSNESS for the next exhibit. Chad Lowe continues in somewhat the same manner with a cockamamie image of the GOP elephant trying to attract gay voters. After that, we abandon contemporary politics for the shame that it is and turn to more worthy subjects. Like Signe Wilkinson’s heartfelt farewell to her colleague Tony Auth (whose obit we posted in Opus 330). Finally, here’s an old (2007) cartoon by the late Etta Hulme that I’m posting because (1) I love the drawing and (2) it shows how persistent are some of the ailments that plague government: I can image the same scene among today’s White House lawyers. I particularly like the old bearded guy. He’s supposed to be someone, I’m sure, but the only face I recognize is GeeDubya’s Attorney General Alberto Gonsalez, the boyish visage on the opposite side of the table. More

chuckles confront us in the next display. Next

around the clock, mostly more gag cartoons that made me laugh, a tendency

prolonged in the next batch. Down the left-hand side, however, is a multi-panel extravaganza from Dan Wasserman, laced liberally with satiric pokes and jabs. With this, Wasserman proves that Dave Horsey (see Editoonery in Opus 328) isn’t the only editoonist to occasional expand from one panel to page-size arrays. Otherwise, this visual aid offers only jokes worth heeding and giggling at. Next,

however, we get some big laughs over the results of the midterm so-called

election. Editoonist Mark Streeter puts himself, Punk-like, as a

miniature painter in the corner of all his cartoons. One of his post-election

cartoons (not shown here) proudly displays the “I Voted Today” sticker, and the

little painter says: “A badge of honor after casting your ballot for something

... against something ... to make a difference ... or just to make it stop.”

But, alas, it isn’t stopping. The gasbags are now having a bacchanal of blather

doing post-election analysis of what happened and why. (Yes, I realize that

with the ensuing paragraphs of pitiless prose, I’m doing exactly the same—only

more astutely.) Daryl Cagle at the left gets us started with an image that represents what the punditocracy has been saying all year long and saw no need to stop saying even after the election it was prognosticating about. The Democrats were held down because of Obama’s fallen approval rating. And immediately to the right, Luojie of the China Daily offers yet another image—a wilting sabre—proclaiming the same thing. On Fox News on election night, Karl Rove was ecstatic: “It was a wave year for Republicans.” But neither of the two pundits I consulted, Ryan Lizza and John Cassidy, both at The New Yorker—and both eminently sober, unhysterical commentators—was willing to call it a Republican wave. Said Cassidy: “If a ‘wave election’ is one that signifies important changes in the underlying dynamics of the American electorate, then this wasn’t a wave election.” The Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm gained—what was it?—fifteen seats in the House and seven in the Senate. And even the pundits had been saying, all along, that in midterm elections, the party of the President loses seats. And that’s what happened. No surprises. At least, none of the magnitude to justify Rove’s jubilant “wave year.” (He was doing what he has made a career of doing—playing the Goebbels gambit, telling the Big Lie over and over again until many people start to believe it. It worked in Nazi Germany; and it’s been working wonderfully here.) “In retrospect,” said Cassidy, “it was a fairly familiar midterm story. A ruling party went into a campaign with an unpopular President and a discontented electorate, and, on an Election Day, characterized by low turnout among the general population, and by intense excitement among activists in the opposition party, it got trounced.” Lizza likewise concluded that nothing much had changed on the political landscape: “The dominant trends in American Politics were mostly reinforced ... the low-turnout midterm electorate benefits Republicans; the Senate will remain closely contested for the foreseeable future; the House will remain the anchor of the Republican Party; Democrats have a demographic advantage in presidential elections.” Below the wilted sabre on our visual aid, Mike Keefe accurately captures the GOP campaign strategy, putting Rove at the center of the plot. The Republicons ran by scaring the electorate—fear of the Barbarian Caliphate, fear of ebola, fear that Obama would take our guns away, fear that the Affordable Care Act was actually working thereby depriving the Pachyderm of political ammunition to use against the feared Obama. By almost universal acclaim, the campaign was marked by a nearly complete absence of discussion of substantive issues—gun control (of course), climate change, gerrymandering success in elections (the cause of all our problems), rebuilding infrastructure and so on. The list is long (add your own issue), but it was not visible. Voter turn-out was at a historic low, reflecting, doubtless, a lack of interest by the body politic in electing anyone campaigning for office by saying nothing that matters. At The New Yorker, Margaret Talbot summed it up: “While fears of ebola—a disease from which one person in the United States has died—clouded the campaign like one of those imaginary miasmas to which doctors once attributed illness, real dangers seemed to slip from view. The latest school shooting on October 24, in Washington State, generated almost no discussion on the campaign trail, especially not of gun control. Just a week earlier, researchers affiliated with the Harvard School of Public Health had published findings showing that mass shootings in the United States—those in which the shooter did not generally know the victims and in which at least four people were killed—have tripled since 2011. Over the past three years, a mass shooting has occurred, on the average, every sixty-four days; over the previous twenty-nine years, one occurred every two hundred days. “Gabrielle Giffords, the former Arizona congresswoman who became a gun-control advocate afer she was wounded in a shooting in which six people died, toured the country in the run-up to the elections, calling for tighter legislation in order to help save lives. Not a single candidate joined her.”

RETURNING TO THE EXHIBIT AT HAND, at the upper right, we have the very best editorial cartoon about the much touted winner of the election—Time magazine’s cover portrait of Mitch McConnell on the magazine’s post-election issue, November 17. As the most conspicuous victor of the contest, now at the pinnacle of his life-long ambition, McConnell winds up on the cover of Time, doubtless the most coveted accompaniment to his victory at the polls. It may be the only time in his life that the Kentucky senator will ever be on the cover of Time. And so what does Time do? It produces an ironic portrait of the arch rival of the Prez styled in the manner of Sherpard Fairey’s famed 2008 campaign poster of Obama. To credit Time, for the moment, with serious journalistic purpose, the magazine was probably pairing the two ostensible rivals according to the captions: if Obama was Hope, then McConnell is surely Change. But I like an alternate interpretation. For McConnell, his moment in Time’s bright spotlight has been forever dimmed by being commemorated in the visual terms of his political foe, the man he plotted fervently to make a one-term President. And failed. Now that I ponder it, I wonder if the magazine was being all that journalistically serious. Perhaps a satirist lurks in the corridors of Time. Below Time (in both location and circulation), Rancid Raves offers our own portrait of the election’s big winner. The most disappointing aspect of the election for me is that now we have to contemplate at least two years of watching Mitch McConnell speaking on tv on behalf of the Republicon-controlled Senate. And I’m sure McConnell will take every possible opportunity to stand there in the glare of the lights. For years now, I’ve thought of McConnell as a mealy-mouthed asshole. In his post-election remarks, he burnished that image. He promised he and his “gang” (he didn’t call it a “gang,” but that’s what he meant) would be happy to “work with the President” —but even as he spoke, he was plotting more scorched-earth obstructionism. We’ve heard this “work with the President” mantra before; and it always means more road-blocking. Reasonable people might suppose that McConnell will be reasonable, now that he’s achieved his long aspiration to be the Majority Leader in the Senate. He’ll have an eye on his party’s winning the White House in 2016, this sort of thinking goes, and so he’ll be willing to “work with the President” in order to pass legislation that the GOP can point to as affirming its superior ability to govern, to get “something” done that the Democrat-held Senate was unable to do. But McConnell has long passed the “reasonable” stage in his political life. He entered politics as a center-leaning, pro-environment, pro-choice Republican in a Democratic state. Then “year by year, he has marched to the right in step with his party,” as New Yorker writer Evan Osnos said. “If McConnell has a deep instinct to rise above it all now, in a bid for comity and history, he hides it well.” Osnos continues: “McConnell has told big donors that he will ‘work at every turn to thwart the Obama agenda, and use appropriations and the budget process to force the President to roll back key elements of Obamacare, to water down Dodd-Frank, to tilt toward coal ... to move forward on Keystone XL, and to stop Environmental Protection Agency action on climate change.” Pretty clearly, to McConnell “working with the President” is likely to happen only if Obama supports every outlandish GOP plan that McConnell lets loose. McConnell’s song is the same song he’s been singing for the last six years. So I have no hesitancy in calling him a genuine horse’s patoot, the south end of a politician going north. And I decided to caricature him as a big butt, with his tightly pursed lips the sphincter between the cheeks. The sphincter, as everyone knows, is the muscle that controls the flow of crap; if it relaxes, the shit spews forth. Seems a perfect metaphor for what happens when McConnell opens his mouth. John Boehner (pronounced “blather”) joined in the GOP chorus calling for Obama to work with Congress. He, like McConnell, cautioned the Prez against acting unilaterally, by executive order, to alleviate the problems in our immigration policy. This is the same double-dealing Speaker of the House who, a scant three months ago, sent the House off on its summer vacation without taking any action on immigration, saying as he turned out the lights, the Prez would have to fix what was wrong on his own. House GOP leaders issued a statement that President Obama could address the crisis “without the need for congressional action,” a statement tinged with some irony given that just the day before, House Republicans had slammed the President with a lawsuit claiming executive overreach. Despite which, they affirmed: “There are numerous steps the president can and should be taking right now, without the need for congressional action, to secure our borders and ensure these children are returned swiftly and safely to their countries.” Geez—make up your mind. Hypocrisy, thy name is Boehner (pronounced “bullshitter”). No,

my McConnell caricature isn’t that good an evocation of his actual appearance.

But I drew it so I could write about “his tightly pursed lips being the

sphincter between the cheeks” with all that image suggests (see above). And now

that I’ve done that, we’ll move on to our second exhibit. Tom Toles at the upper left creates a metaphor about the cost of the campaign, reputedly the most expense off-year campaign in history. The cartoon evokes the old story about the five-year-old boy who was an incurable optimist. Taken to a room piled high with horse shit, the kid yelled delightedly, grabbed a shovel, climbed to the top of the pile and began enthusiastically digging, throwing manure into the air joyfully. Asked why he was so happy, the kid answered: “There’s gotta be a pony in here somewhere.” George F. Will, another conservative asshole whose tightly pursed lips betray his identity by being a sphincter, occasionally makes a telling remark, like his post-election comment about the $1 billion spent on ads during this election cycle: “Considering the enormous consequences the political class has as it sloshes trillions of dollars hither and yon, it is strange that in selecting the 2015 members of this class (i.e., Congress), Americans spent less than half the $2.2 billion they spent last month on Hallowe’en candy.” I think Will might be exaggerating—on the low end. Or, rather, he’s leaving out costs other than tv ads. The latest figures show it cost almost $4 billion ($3.7) to send the scalawags back to Washington this time. But we spent $7.8 billion on Hallowe’en (counting costumes and what all in addition to candy). Next around the clock, Dave Granlund provides a memorable image of the “real winners,” the ones going to the bank most often. Here, then, another reason that the so-called “news” media don’t expose the lies in the ads they run: the sponsors of the ads would stop placing them with media that revealed their essential mendacity, and the media would suffer a devastating loss of windfall revenue. Next, J.D. Crowe offers the best visual metaphor I’ve seen thus far for the ever-predictable outcome of midterm elections. When over 90 percent of the incumbents are re-elected, our elections are best represented by the symbol for recycling. And, finally, Mike Luckovich’s turkeys speak to the astounding capacity of the American voter to vote against self-interest. In a midterm election, the number of seniors voting typically outnumbers all other age groups; this year, it was twice the number of 18-29 year-olds. People older than 65 tend to vote Republicon. That means they’re voting to repeal Obamacare and to cut the Medicare budget and Social Security. Does this make sense? Only if you believe suicide is popular because it’s centrally located. In Kansas in another version of the same suicidal tendency, voters re-elected Governor Sam Brownback, who, when elected for the first time four years ago, announced that he would turn the state into a laboratory test of right-wing policies, particularly those favored by one of his most famous constituents, Charles Koch (pronounced “kook”), whose family company is headquartered in Wichita. He began by eliminating his opposition: he drummed moderates out of the state legislature by mustering extremist conservatives to defeat them in primaries, and then, with the legislature acting as his rubber stamp, he reduced taxes and cut spending drastically. Brownback led the charge to privatize Medicare, curb the power of teachers’ unions, and cull thousands from welfare rolls. He signed bills exempting Kansas gun manufacturers from federal firearms regulations and helped install some of the nation’s strictest anti-abortion rules. He rejected the Medicaid expansion in the Affordable Care Act and approved a law that made sure his successor can’t overturn the decision. But it was cutting taxes and spending that have brought Kansas close to bankruptcy. Brownback began with a $700 million budget surplus, which is projected to dwindle to a $238 million deficit. Both Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s have downgraded the state’s credit rating. Brownback’s grand tax experiment was once hailed by conservatives as a prototype worthy of replicating everywhere. In an interview last year, he said: “My focus is to create a red-state model that allows the Republican ticket to say, ‘See, we’re got a different way, and it works.’” But it ain’t working. The Wall Street Journal recently dubbed Brownback’s approach “more of a warning than a beacon.” And yet, voters want this fiscal maniac to continue to destroy the state. Does this make sense? His victory was a narrow one, but it was still a victory for idiocy. On the other hand—to edge off in the direction of idiocy’s opposite—Jerry Brown was re-elected in California. It’s his fourth term, counting two consecutive terms a few decades ago. He inherited a broken state, and he fixed it. He deserves to be re-elected. Hell: he deserves to be elected President. But back in Washington, what, do we imagine, is the future for the federal government with McConnell in the catbird seat and Republicons crowing about their “wave”—what some will undoubtedly call a “landslide victory.” Bill Mahr made a prediction: “The Republicans say they’re going to cutt off the balls of the Democrats,” he observed, “—good luck on finding them.” In his short post-election remarks, Obama said he would look for ways to work with Congress, particularly on the issues he and the GOP are close to agreeing on. He also “noted that two-thirds of those eligible did not vote Tuesday, suggesting the lack of a broad GOP mandate, and he reminded reporters that the policies he has championed, including an increase in the minimum wage, were endorsed by voters in multiple states” (Associated Press). One of those states is Arkansas where voters elected Republicans as senator and governor while approving, by a two-to-one margin, a raise in the state’s minimum wage. The Republican “wave” doesn’t exist anywhere but in Karl Rove’s bubbling brain. Said Cassidy: “It would be premature to call the 2014 election a major turning point. There’s little evidence that the country has taken a big swing toward the Republican Party’s ideology or policy positions. ... The same exit poll that showed fifty-nine per cent of respondents were dissatisfied or angry with the Obama Administration found that sixty-one percent of respondents were angry or disappointed with Republican leaders in Congress. It found that fifty-three percent of Americans have an unfavorable opinion of the Democratic Party and that fifty-six percent have an unfavorable opinion of the Republican Party.” And in Washington, the government will remain split—fragmented—for a long time, said Lizza: “Rather than either party dominating the Senate for a long stretch of time, it is much more likely that the chamber will remain competitive, with the parties alternately surging and receding from election to election. In two years, it will be the Democrats turn.” The House is likely to remain in GOP possession for a long time. But the Senate, where a third of the members are up for re-election every two years, is likely to see-saw back and forth, first Republican then Democratic. Those running this year were from more Romney red states than otherwise; the dice were loaded to begin with.

BY THE WAY, the best source of editorial cartoons not printed in your local paper is the Santa Cruz Comic News, which has been coming out once a month for thirty years. A one-year subscription is $29; two years, $54. Order online at thecomicnews.com or send your check to Comic News Subs, P.O. 8543, Santa Cruz, CA 95061.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS “The great asset of marvels movies like ‘Guardians of the Galaxy,’ ‘Iron Man,’ and ‘Captain America’ is there sense of humor. Warners’ superheroes lean much more somber.”—Stephanie Merry at the Washington Post

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words Whilst wandering lonely as a cloud across the wilds of Indiana a month or so ago, I visited my favorite antique mall and there—lo, and behold—I found Mutt and Jeff. Two smallish figurines—Mutt is 9 inches tall; Jeff, 5 inches. Made by Mark Hampton Inc., they’re copyrighted 1911 by H.C. Fisher (ol’ Bud hisownself) but dated 1909-1910. Mutt is the more endearing of the two (if I recall aright, Fisher admitted to liking Mutt better than Jeff, who came later to the strip, at first entitled “A. Mutt”): he has his hand to his chin in a habitual pose, and his feet are slightly pigeon-toed. Could barely wait to share them with you.

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping AUTUMN, OCTOBER in particular, was a great time for anniversaries and similar historic celebrations tied to the calendar.

Greg Evans’ Luann celebrated her 18th birthday not in October but close: during the last week in September (that’s

the character, not the strip; the strip is 29), and Evans celebrated by

importing a “guest artist” for the festivities. But that’s not all there is to the surprise: until 1998, Jonathan didn’t know he had a cartoonist grandfather. But, as Evans once opined, Jonathan had the “cartoonist gene”: he had been drawing all his life and even at the age of 12, he knew he wanted to be a cartoonist. Jonathan discovered his cartoonist grandfather when his mother, Rhonda, discovered her birth parents, Greg and Betty Evans. At the time of Rhonda’s birth, Greg and Betty were art students and not married. When they learned Betty was pregnant, Evans said, they decided they were not ready to settle down; they chose to give the baby up for adoption. Rhonda had known the names of her birth parents since 1990, and she knew that they had been art students. She noticed Evans’ name on the Luann comic strip, and wondered if the cartoonist was the Greg Evans who was her father. She wrote Evans, pretending to be asking questions about cartooning for her artistically inclined son. Evans’ answer convinced her that he was her birth father, and soon thereafter, she wrote him, saying, “I think I may be your daughter,” adding various aspects of her life that led her to that conclusion. Evans wrote back, saying, Yes, we are your parents. In the summer of 1998, Rhonda and her family went to California to meet the Evans—Greg, Betty, and their two children, Karen and Gary. They’ve been in friendly contact ever since. Last year, Greg invited Karen to help him write the strip. They brainstorm storylines together, and Karen sometimes blocks out weeks of dialogue, which Greg then hones into final form. At the time, Greg mused about his legacy—leaving the strip to his children to continue, with Jonathan doing the drawing (since neither Karen nor Gary draws much). And now that Jonathan has his foot—er, pencil and pen—in the door, who knows? Luann’s

birthday party ended on Sunday, September 28, by which time Greg had resumed

the art chores—and had become the secret punchline. Yes, that’s his

self-portrait in the first panel; and he’s standing next to his daughter Karen. IN CASE YOU MISSED IT —which would be hard to do because Mike Peters’ dog strip is in almost everyone’s newspaper—this month Mother Goose and Grimm celebrated its 30th anniversary, and the festivities consisted largely of a two-week continuity (October 6-18) in which it is revealed how Mother Goose acquired her contrariwise canine companion.

The conceit turns pet adoption on its head: Mom goes to the Happy Hill Dog Farm to adopt a dog, but Happy Hill, if we are to judge from Grimm’s behavior, is not so much a kennel for stray dogs up for adoption as it is a juvenile detention center for four-legged miscreants, of which Grimm is a persistent example. For two weeks, we are treated to visions of Peters’ big-nosed mutt as a misbehaving nut dog if not an outright criminal. At the end, however—just as Grimm seems bent on escaping from Mom’s place, he turns dog instead of delinquent, and we learn why he stays on. A happy anniversary indeed.

YOU COULD SCARCELY MISS THE CELEBRATION at Hi and Lois, which turned sixty on October 18.

Mort Walker and Dik Browne performed the delivery sixty years ago, but the celebration this year was conducted by writers Brian and and Greg Walker (sons of Mort) and artists Chance Browne (son of Dik) and Eric Reaves. The week ending on the birthday was spent comparing life sixty years ago to life today, which offered opportunities for some gentle satire on the fleeting nature of fads and other daily foibles.

BUT ONE OF THE

MONTH’S MILESTONES was not so festive. Ed Stein ended his Freshly

Squeezed strip on October 19. As he explained when, several weeks ago (see Opus 329), he announced the impending doom, the strip wasn’t going Here’s the last week of dailies, October 13-18, which present a rarity in comic stripdom—an actual conclusion. (The final strip, a Sunday, wasn’t part of the “conclusion,” so I’m not posting it here.) As you can see, Stein waxes increasingly, stealthily, metaphysical for five days, and then, at the end, the pictures embody the conclusion of the philosophical discourse young Nate is having. A conclusion and a metaphysical whimsy all in one. Profound work, Ed.