|

||||||||

Opus 330 (September 20, 2014). Out of the rabbit hole this time, we review some of the best editorial cartoons on the mess in Mesopotamia (including a long disquisition on Bronco Bama’s response last week) and on Ferguson, plus obitoons on Robin Williams, Lauren Bacall and Joan Rivers and an obit for veteran editoonist Tony Auth. When I was a boy in the early 1940s, I was fascinated by the villains in Popeye: they were all dressed black frock coats and wide-brim hats, and they had beards, full beards—bristly, wiry beards. Now, 70-some years later, thanks to the Barbarian Caliphate, real-life villains have beards and dress in black. They would doubtless not be amused to learn that I liken them to comic strip villains. And so, perforce, I do exactly that.

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy Newspaper editorial page editors identify their precious opinion columns by running an editorial cartoon at the top of the page. Thus, the most serious section of today’s newspaper is identified by a flag of comedy: every newspaper in the U.S. except the fustian New York Times publishes a cartoon on its editorial page. And the desperate Denver Post increased the ranks of noncompliance last year by dropping the editoon from the weekday paper, retaining it only for Sundays, when it also runs a weekly round-up—and promotes its website editoon collection. So even a defector sees the value in editorial cartoons. On the other hand, Tom Cavanaugh at the conservatively bent National Review has no use for editorial cartoons. He hates them because most editoonists are liberal, and on August 15, he laid into the Washington Post’s Tom Toles, beginning with a categorical assault on editorial cartooning generally, toting up its vices in a litany of vituperative contumely seldom seen in captivity: “cheap and half-baked premises; labeling of grossly obvious figures and concepts for the benefit of the irredeemably ignorant; unfunny gags; barnacle-encrusted cliches; a totally predictable point of view; glancing-at-best familiarity with issues in the news.” What Cavanaugh says about Toles is similarly intemperate so I won’t mention it here. I quote Cavanaugh’s invective because it anoints editoonery with acclamation of achievement: such monumental rage and bad-tempered frustration can be inspired only by something that is profoundly, powerfully, effective. And just how, we might ask, does the humble editorial cartoon accomplish its mission? Finding answers to that question is the mission of this department, wherein we examine the ways in which editoonists wield their rapier-like pens. Our first visual aid to this purpose takes up the matter of the unrest in the Mideast—Iraq chiefly, but also Syria and the rest of that tumultuous region. But first, a prefatory admonition. We ought to stop dignifying the dubious status of the bloodthirsty thugs who have ostensibly “conquered” a third of Syria and a third of Iraq. We should stop referring to them as the Islamic State, thereby lending brute viciousness a name that gives it a standing it scarcely deserves by implying it belong to the international family of nations. Barbarism is not a nation. Instead, we should call ’em as we see ’em: the Barbarian Caliphate of Murdering Muslim Thugs—“Muslim thugs” distinguishing them from other Muslims who are not thugs. In Egypt, the country’s top Islamic authority, revered by many Muslims world-wide, is calling the brutes the “al-Qaeda Separatists in Iraq and Syria.” Still a little too dignified for me. I’ll stick with Barbarian Caliphate. And

now, on to our first gaggle of cartoons. Next around the clock, Clay Bennett presents a memorable image of the centuries-long feud between the Sunni Muslims and the Shiites: they are effectively destroying each other in a bitter, mindless conflict. Stantis returns at the lower right with another dark and threatening metaphor—laced with an ironic reference to the lies of the George Dubya regime. And then Rick McKee poses the dilemma that all Westerners are pondering: how can a religion ostensibly promoting peace also espouse such vaunting destruction and heartless cruelty as we’ve witnessed in recent years? McKee’s multiple-choice quiz dramatizes the gross incongruity. We

aren’t the only witnesses to Barbarian cruelty who find it heartless. We begin Going from left to right, then top to bottom, we next encounter Nate Beeler, who shows what one of the outcomes of Barbarian Caliphate violence is: they got Barack Obama off a dime. He has been reluctant for months to take an action that will plunge a war-weary America back into the conflicts of the Levant neighborhood that we have just about extricated ourselves from. But the brutality of the Barbarians has forced him—digging in his heels—to confront ISIS. On the cusp of announcing a strategy for the Mideast, Obama said he didn’t have a strategy. While some of the so-called news media overlooked this gaffe in order to comment on his tan suit’s insuitability for the occasion—a faux pas that Beeler points out as we move down the display in a cartoon that contrasts the trivial with the momentous by giving the latter the largest letters in the picture— the ravening Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm pounced, saying Obama had admitted what they’d always known: he doesn’t know what to do. But the image that John Cole deploys in the cartoon to the right suggests that devising a strategy is about as easy as juggling chain saws as they’re running (—er, chaining?). “Up in the air” is a better way of describing what Obama meant. When he was campaigning for Prez the first time, one of the things he strenuously implied (and even, on occasion, said) was that governing requires compromise. And he clearly believed that he could sit down and talk with any group of people, discover what they had together in common, and then devise a policy that would address all the concerns in the room—at least in part if not entirely. From the beginning, Obama was a great believer in and champion of negotiating for a consensus. Alas, he couldn’t make it work domestically. The rabid GOP—comprised of fanatic Tea Baggers, racist Southerners, frustrated and angrily resentful Republicon party operatives, and traditional (well-meaning but misguided) conservatives—launched immediately a campaign to deny Obama a second term, which program they implemented (and continue to implement even while he’s in the midst of his second, and last, term) by defeating every plan he puts forward (thinking, so to speak, that no one will like him if he doesn’t do anything). Overseas, however, Obama sought to put the philosophy into effect. And that was and is his strategy. Despite what he said, Obama surely had a strategy. He announced the strategy in the next day or so: by consensus to build a coalition that will work to degrade the Barbarian Caliphate’s capability until the gang of Muslim thugs can be defeated outright on the ground by the Iraqui troops and others of the region. And do it without putting any American soldiers on the ground in Iraq or Syria. The degrading tactic he has already exercised in places like Somalia and Yemen, where drones, intelligence, and limited special operations have surgically chipped away at enemies without exposing ground troops to the risks of conventional warfare. So why did he say he had no strategy? How would it have sounded had he said: “Beginning now, our strategy is to jaw-bone other nations into joining our effort. As their big brother, we hope to cajole them into putting their boots on the ground while we glide safely overhead in drone attacks.” Negotiations always work best when the negotiators approach each other as equals. Announcing a plan to pressure other nations into joining us scarcely presents the U.S. as an equal. And Obama surely knew all this. So he kept his mouth shut and pretended we had no strategy—a ruse that would permit him to engage potential partners in negotiation ostensibly to develop a strategy that all would agree to. Could he have done that if his potential partners believed that he’d already made up his mind—that he had a strategy and the purpose of the negotiation was to coerce them into following it? I doubt it. They probably knew it anyhow, but Obama’s manner of approaching the issue let them and the rest of the watching world think that they were all working together to develop a strategy. (And to some extent, that was, indeed, what they were doing—working together to devise a plan all would participate in.)

I WATCHED THE OTHER NIGHT the movie “Seven Days in May” about the fictional threat of a military overthrow of the U.S. government by General James Matoon Scott (played by Burt Lancaster). It was made in 1964, but when Jordan Lyman, President of the United States (Fredric March), having foiled the plot, makes a speech at the end, it struck me as remarkably a propos our current situation. He says: “There’s been abroad in this land in recent months a whisper that we have somehow lost our greatness, that we do not have the strength to win without war the struggles for liberty throughout the world. This is slander. Because our country is strong, strong enough to be a peace-maker. It is proud, proud enough to be patient. The whisperers and detractors, the violent men, are wrong, we remain strong and proud, peaceful and patient. And we will see a day when on this earth all men will walk out of the tunnels of tyranny into the bright sunshine of freedom.” War is not the only way to peace. What a concept. Obama, as I imagine he is, could have made that speech. In fact, he has made it from time to time. He came close in the closing remarks of the speech he gave on September 10: “Abroad, American leadership is the one constant in an uncertain world. It is America that has the capacity and the will to mobilize the world against terrorists. It is America that has rallied the world against Russian aggression, and in support of the Ukrainian peoples’ right to determine their own destiny. It is America – our scientists, our doctors, our know-how – that can help contain and cure the outbreak of Ebola. It is America that helped remove and destroy Syria’s declared chemical weapons so they cannot pose a threat to the Syrian people – or the world – again. And it is America that is helping Muslim communities around the world not just in the fight against terrorism, but in the fight for opportunity, tolerance, and a more hopeful future. “America, our endless blessings bestow an enduring burden. But as Americans, we welcome our responsibility to lead. From Europe to Asia – from the far reaches of Africa to war-torn capitals of the Middle East – we stand for freedom, for justice, for dignity. These are values that have guided our nation since its founding. Tonight, I ask for your support in carrying that leadership forward. I do so as a Commander-in-Chief who could not be prouder of our men and women in uniform – pilots who bravely fly in the face of danger above the Middle East, and service-members who support our partners on the ground. “When we helped prevent the massacre of civilians trapped on a distant mountain, here’s what one of them said. ‘We owe our American friends our lives. Our children will always remember that there was someone who felt our struggle and made a long journey to protect innocent people.’ “That is the difference we make in the world. And our own safety – our own security – depends upon our willingness to do what it takes to defend this nation, and uphold the values that we stand for – timeless ideals that will endure long after those who offer only hate and destruction have been vanquished from the Earth.” The usual political hogwash, you might say. Or you might say it has the ring of poetry. And poetry inspires.

OUR LAST TWO CARTOONS in this vicinity are both by Steve Sack. In the first, Obama is dipping Uncle Sam’s toe into the quagmire that is the Mideast. Boots are left behind, but quicksand will suck you in. And then how do you get out? Obama’s strategy isn’t terribly clear about that last part. And negotiating a mutual strategy among different nations with varying agendas isn’t easy, as Sack indicates in his next cartoon. Some have signed on already but others have not. As of this writing (September 15), Turkey is hovering on the edge: the Barbarian Caliphate holds a couple dozen Turkish diplomats hostage, and the Turks, understandably, don’t want to do anything to anger the Muslim thugs enough to make them start beheading. Kicking

off our next visual aid at the upper left, David Fitzsimmons’ dramatic

rendering of the American eagle looming severely over a Barbarian beheader is

vivid visual shorthand for the unintended consequence the Muslim thugs hadn’t

the wit to prepare for. And below Benson, here’s Tom Toles, taking a poke at Congress, too timid—too desirous of being re-elected indefinitely—to have an unequivocal position on whatever action we should take in the Mideast. The image of a cowering Congress is persuasive. Even if it doesn’t quite fit into the national mythology. (And here, I’m about to veer off into another of my periodic diatribes only tangentially related to the editoons we’re ostensibly viewing; but you can skip all this fulminating verbiage by scrolling down to the next time I deploy ALL CAPS.) American foreign policy is governed by one of two philosophies; it vacillates back and forth between them. One is the bully-boy philosophy: we’re the biggest, strongest, healthiest kid on the block, so everyone is well-advised to do as we say. The other is conciliatory, collaborative: we, like all nations, want peace and prosperity for our country, so let’s talk together about how we can all achieve that. Just because you’re the biggest doesn’t make you right—as GeeDubya and Darth Vadar Cheney proved by getting us into the mess in Mesopotamia to begin with. They probably forgot that the people who live there have wishes and opinions of their own that might not coincide with those of the most powerful nation on earth. Others of the bellicose battalions of the GOP make these same mistakes, John McCain most conspicuously. Obama clearly espouses the second of the two philosophies. And it’s one I agree with (but, then, you knew that, eh?) Still, announcing a policy, a strategy, however vague it may be in its developmental stage, is not the same as pulling it all off as planned. Our offensive against the Barbarian Caliphate is unlike any other operation we’ve ever undertaken as a nation. And that’s because the Barbarians are unlike any foe we’ve ever encountered. In announcing a re-invigorated caliphate, the Barbarians reveal their fanatic adherence to a long-lost Islamic state. In the September 15 issue of The New Republic, Graeme Wood describes the notion that drives the Barbarians: “The entire self-image and propaganda narrative of the Islamic State is based on emulating the early leaders of Islam, in particular the Prophet Muhammad and the four ‘rightly guided caliphs’ who led Muslims from Muhammad’s death in 632 until 661. Within the lifetimes of these caliphs, the realm of Islam spread like spilled ink to the farthest corners of modern-day Iran and coastal Libya, despite small and humble origins. Muslims consider that period a golden age and some, called Salafis, believe the military and political practices of its statesmen and warriors—barbaric by today’s standards but acceptable at the time—deserve to be revived. Hence ISIS’s taste for beheadings, stonings, crucifixions, slavery and dihimmitude, the practice of taxing those who refuse to convert to Islam.” Obama said the “operation” will be long and difficult. Our patience will be tried. But in saying this, Obama did not flesh out the meaning of his words. The Barbarians are religious fanatics. Aflame with their belief, they will not be easy to defeat because they have no place to go in defeat. They can’t just lay down their arms and go back to farming or banking like our foes of yore. They’ve never been farmers or bankers: they are full-time crusaders who want to re-establish a 1,400-year old social and religious order. And they will still want to do this even if they’ve been beaten on a battlefield. They won’t go back to farms and banks. They’ll go into caves and start planning the next jihad. They’re zealots, fanatics, and they won’t give up. They’ll keep on until there’s no one left. Or until someone imprisons and thereby renders inoperative their bodies—or changes their minds. Ever try to change a zealot’s mind? We’re in for a century or more of intermittent “special ops” against a tenacious foe who won’t give up. Obama gave his speech on the eve of the 13th anniversary of the tragedy of September 11, 2001. An unsettling coincidence. In the last cartoon of the display at hand, Signe Wilkinson shows us with heavy-handed irony what we have to celebrate, the pictures undermining the joyful tone of the words on the sign.

UNREST IN THE

MIDEAST does not end at the borders of Muslim countries. Israel is part of the

conflagration. Signe Wilkinson’s paring of Israeli and Palestinian scholars makes the plea of each ironic and self-defeating. Any dispassionate reading of the history of their conflict won’t give either side a right to the territory that the other does not also enjoy. And the hands of both are bloodied by atrocities each has committed throughout the region’s history. Clay Bennett is back at the lower right with a metaphor for how Hamas is conducting the “war”: this rabid terrorist group, sworn to destroy not only Israel but all Jews, is using Gaza, its unarmed citizenry, as its defense against the lion (Israel) that it thinks must be tamed (destroyed). The lion tamer of yore used a chair for the purpose, but here, the chair is occupied by what seems to be a young kid, signifying the slaughter of the innocent unarmed civilians, including women and children, as Israel bombs and invades. Israel’s

invasion of Gaza is something that editoonists must draw about carefully. Every

cartoon on the subject has the potential to inspire protest from American Jews.

And several cartoonists have raised Jewish ire lately with drawings of

characters with big noses— even when all of the characters the cartoonist draws

have big noses, as is the case with Rob Rogers. The critic goes on to say the local Jewish community is “appalled by this display of anti-Semitism” and faults the accuracy of Rogers’ depiction: “one sees Israeli missiles aimed at Gazans when, in fact, it was Hamas which aimed its missiles at Israeli civilians. Israel’s response is to target the terrorists.” All true—about the aiming of missiles—but also illustrative of sensitivities that can find offense where none is intended. Editoons by their very nature don’t nuance well. Here, the chief message is ironic: given the conditions of life in the blockaded Gaza, Israel should scarcely be surprised that Gazans hate them. That message, however, is lost on the critic, who sees only racial and ethnic slurs in the picture. But the situation in Gaza is horrendous enough that even Art Spiegelman felt obliged to comment, which he does, just below Rogers. And coming from the cartoonist whose career is built upon a graphic novel about the horrors of the Holocaust, the comment is incendiary. Designed for a recent issue of The Nation, his cartoon is, properly speaking, a collage: he deploys a Biblical-style picture of David confronting the giant Goliath in the first panel; then in the second, he manipulates the images, shrinking Goliath so that David appears the larger. Captioned “Perspective in Gaza (The David and Goliath Illusion),” the cartoon clearly indicts Israel as the new bully on the Palestinian block. Writing to his Facebook followers, Spiegelman excused himself by saying he has spent “a lifetime trying to NOT think about Israel,” adding that “Israel is like some badly battered child with PTSD who has grown up to batter others.” It remains to be seen whether Spiegelman will suffer the kind of criticism that others who’ve taken sides on the issue have suffered. To shift conflicts and to return to the fourth cartoon at the lower left of our previous visual aid, we have the Ukraine dilemma, in which Daryl Cagle characterizes Putin as the bully beachboy who kicks sand on the hapless girlfriends of 90-pound weaklings—a reference to an antique advertisement in comic books for body-builder Charles Atlas’ program for fitness (and muscles, that’s what we all fell for—the muscles we’d get by doing the exercises in his books that we were urged to buy). In the vintage ad, the weakling buys the books, builds muscles, and returns to the beach to punch out the bully in the last panel and regain the affection of his fickle girlfriend (who had deserted him for the embrace of the bully). Here, Cagle gives the role to Bronco Bama, who, instead of building up his own body so he can tackle the bully, urges the victim to help herself. Scarcely the Charles Atlas way.

SHIFTING

AGAIN, this time to the home front, we come upon Ferguson. Just below McKee, Mike Keefe continues an assault on the excesses of militarizing municipal police forces, a subject that is now being discussed far and wide. In Keefe’s imagery, the force of law and order is clearly much out of proportion to the threat it seeks to control. At the lower left, Jim Morin brings the gun control issue into the Ferguson focus, and the issue is by no means one in which one side is clearly right. Jonathan Thompson, editor of the High Country News in Durango, Colorado, took the side of the police—and then extended the predicament: “That law enforcement officers are afraid is understandable. The sale of assault rifles and ammunition has escalated in recent years, meaning there are more, increasingly deadly weapons out there that could be used against cops. And as the Cliven Bundy debacle in Nevada demonstrated, some members of the public are perfectly willing to wield those weapons to stop law enforcement from doing their jobs. No wonder the cops want armor. “And yet,” he goes on, “my local sheriff, like many in the rural West, is a vocal critic of laws intended to keep the most potent, military-style weapons out of the hands of criminals, and he is one of more than 50 Colorado county sheriffs—many of whose departments area also stocking up on guns and armor—who refuses to enforce new state gun laws [requiring background checks and limiting the capacity of magazines]. Something here doesn’t make sense.” What does make sense, however, is that police are increasingly at risk in facing armed and dangerous citizens bred with a new kind of zealotry. (Diatribe warning.) In the Bundy episode in Nevada in April, the Bureau of Land Management was forced to stand down by a mob of heavily armed rabidly anti-government “sovereign citizens” who did not happen spontaneously upon Bundy and his plight in the desert. Bundy had gone online to declare a “range war” after BLM agents had arrested his son, who was filming the round-up of Bundy’s cattle, which the BLM planned to sell in order to retire some of the debt in back fees that Bundy refused to pay for grazing his cattle on government land for the last 20 years. His message reached hundreds of Tea Baggers, Libertarians, Oath Keepers, and others of this paranoid macho ilk, who immediately mounted up and rode off to Bunkerville by the truckload, angry, armed, and ready to fight. One of their number, Ryan Payne, whose Operation Mutual Aid he formed to lead militias nationwide in responding to federal “aggressions,” toured the lands Bundy was using, looking for ways to defend them if necessary. He determined where to put snipers, and on the day of the final confrontation, militia snipers lined the hilltops and overpasses with their weapons trained on federal agents (a felony punishable by 20 years in prison). Understandably, BLM backed off rather than risk wholesale bloodshed. Payne and his cohorts trumpeted victory: “The feds were routed!” they exclaimed, over and over. The Bundy battle started a contagion. According to the fall Intelligence Report from the Southern Poverty Law Center, tense encounters between the BLM and anti-government activists have occurred in several states—Utah, Texas, New Mexico and Idaho—since the Bundy episode. The most spectacular evidence of the spread of the contagion took place in June when two anti-government supporters of Bundy, Jerad and Amanda Miller, took their hate for the police to Las Vegas where they gunned down two police officers at a pizzeria before killing a bystander who attempted to stop them. The murderers draped one officer’s body with a “Don’t Tread on Me” flag, the same banner that had been waved at the BLM in Bunkerville. The Bundy adventure has “reinvigorated a temporarily faltering militia movement,” said Ryan Lenz in his SPLC report. But even when supposedly faltering, the movement has grown spectacularly since Barack Obama was elected Prez, “growing from about 150 ‘Patriot’ groups, or militias, in 2008 to more than 1,000 last year. There have been 17 shooting incidents between law enforcement officials and anti-government extremists since 2009. ... Since the mass murder of 9/11, homegrown extremists have killed more Americans than Muslim jihadists....” No wonder police departments want the accouterments of the military: they’re facing a sometimes savage fringe element—armed with military weaponry.

IN OUR NEXT

VISUAL AID, we’re still in Ferguson, where, as everyone surely knows by now, an

unarmed but very large African American teenager was shot to death by a white

policeman. That’s enough to turn the shooting into a racial incident. And in

Ferguson, where African Americans are about 67% of the population but have only

three or four of their race on the police force, the incident quickly became

provocation to demonstration and, soon enough, near riots in the streets and

looting of stores. David Fitzsimmons’ comment at the lower left comes as a sort of aside about the racial prejudice that has hamstrung the Obama administration almost from the start. Remember Jim Wilson?— the congressman who, during Obama’s first State of the Union message, shouted “You lie!” to the President of the United States. Wilson is from South Carolina, which was in the Confederacy during the Civil War (fought, you remember, to free the African slaves—or to keep them enslaved). I don’t want to paint with too broad a brush here, but a man of Wilson’s vintage (he was born in 1947) spent a good portion of his childhood in the segregated South before the Civil Rights movement achieved its most glamorous goal in 1954, desegregation of public schools. I suppose it’s therefore reasonable to suppose that Wilson partook of the long-lingering racial prejudices of his childhood. If so, it’s equally reasonable to suppose that his “You lie!” was a less obnoxious version of “You uppity nigger.” Fitzsimmons’ cartoon, in addition to alluding to the White House’s probable sympathy with the black population of Ferguson, also reminds us all of the bigotry that doubtless infects much of the congressional opposition to Obama, a bigotry that gets political reinforcement by its attachment to conservative resistence to everything Obama hoped to achieve. The

questions about racial justice raised in our previous exhibit are re-iterated

and emphasized in the next. To say the problem is our inability to communicate in any meaningful way is a step in the right direction. The next step is blunt candor—for instance: as a white man, I’m afraid of black people. Not always but whenever I’m alone on a street at night and encounter a few teenage African Americans. And that fear colors (pardon) my interactions with African Americans whenever and wherever I am with them. Until I can somehow overcome my fear, racism will no doubt endure. What a black man would say to match my confession I have no idea of. But any conversation about race, it seems to me, ought to include his blunt candor as well as mine. At the annual Comic Arts Conference during the 2014 San Diego Comic-Con, I had a glimpse of what a black man might say. At a session about the future of race in comics, a member of the audience asked how the good-and-evil stereotype of white hats and black hats should be dealt with, and Jeremy Love, author of Bayou, said he was not much concerned about white and black. What he focused on was identity. Suddenly, it dawned on me: racism destroys individual identity. Of course. Why I’d never realized this before I can’t say. But there it was. Maybe the national conversation about race ought to be about identity. At the lower left, Chan Lowe may not be dealing with the issues of race in America, but his allusion to “stand your ground” and the weaponry of a militarized police force seems somehow connected. But mostly, I like his drawing.

IN OUR NEXT

VISUAL AID, we return to the usual ping-pong of national politics in which, at

least here at the Rancid Raves Intergalactic Wurlitzer, the Grandstanding

Obstructionist Pachyderm is a perennial butt of every joke. Finally, at the lower left, we have resurrected Daryl Cagle’s charming picture of Ted Cruz, drawn during Cruz’s infamous fililbuster, about which Cagle said: “When Ted Cruz was doing his useless filibuster, reading from Dr. Seuss, and the other cartoonists were all making Dr. Seuss metaphors, I was rather more annoyed with Cruz so I drew him as a monkey thrown his poop. ... a homage to the great British cartoonist Steve Bell, who drew a famous image of George W. Bush in a similar pose. I’m a big Steve Bell fan.” Steve Bell is the Joan Rivers of the United Kingdom: nothing is too sacred or too outlandish when making a point, a humorously, and, hopefully, as grossly as possible—without any regard at all for decorum or convention. I’m included Cagle’s cartoon here because I think we all need to remember that monkeys love throwing their own poop, and they are, therefore, the perfect metaphor for politicians. Thanks, Daryl. Our next two visual aids are multi-panel cartoons, which I include here for two reasons: first, I agree with what the cartoonists say; second, they each demonstrate, in separate ways, the way multi-panel editoons function. The first, The Modern World by Tom Tomorrow (aka Dan Perkins), takes the form of the traditional comic strip—except that there is actually no succession of action, which is what happens in the usual comic strip.

One thing doesn’t happen and then another thing, usually the next thing in a succession of events or actions. There isn’t even a succession of speeches by the same speaker. Instead, Perkins gives us a list of Republicon “positions” and uses the form simply to heap up his indictment of the “anti-party.” Each of the GOP positions is more absurdly extreme than the previous one, and it all culminates in a blindingly myopic endorsement of GeeDubya’s dubious reign as Prez. David Horsey’s “Guide to Red & Blue” doesn’t present a succession of actions in the usual comic strip form either. In fact, there is no “strip” here. Instead, we have vignettes in pairs, each vignette comparing differing attitudes on the same topics. All the pairs belong together under the rubric of comparing Red and Blue attitudes—conservative and liberal. Horsey could have done the same in a series of individual pair cartoons, but by lumping them altogether, he achieves what Perkins achieves—a heap that accumulates and condemns as it piles up. By the way, Horsey, when he was a full-time staff editoonist at the now defunct Seattle Post-Intelligencer, sometimes did full-page cartoons of the kind we see here for a special section of the paper’s Sunday edition. All beautifully complicated artwork like “Red & Blue”; you wonder where he got the time. With

our next display, we begin to drift off into other realms of political

malfeasance, beginning with the immigrant predicament. With Tony Auth at the lower left, we shift our attention to the VA mess. The congressmen in Auth’s little drama pretend outrage at the failures of the VA—failures caused mostly by a huge influx of veterans to care for—ignoring what Auth makes sure we can’t: the vets need medical help because Congress keeps sending American troops into wars. The meat grinder metaphor is murderous—and memorable. We’re

back to multi-panel cartoons in our next exhibit—all about some of the Supreme

Court’s recent decisions. But it’s Pat Bagley who deploys pictures most effectively in this display. Playing upon the word evolving, he invokes “evolution,” depicting Justice Scalia as an ape-like primitive on the first rung of the evolutionary ladder—which, in the cartoon’s logic, explains why Scalia has such a low opinion of women that he opts to deprive them of an opportunity to make a decision for themselves, bowing to the wishes of the Hobby Lobby religious fanatics. In

our last visual aid, we resort to simply enjoying the comedy in cartoons, the

first two of which are not, strictly speaking, editoons at all. The next two are editoons, both dealing with the new seating arrangements on airplanes. Patrick Chappatte supplies an image that just might be too true to be good. And Ed Hall’s image explains the reason for cramping leg room. By exaggerating the situation, Hall turns a tortuous experience into hysterical laughter. But it appears that the sardine can is our next blueprint for aircraft interior design.

Obitoons: The Eulogy of Editoonery One of the rituals that editoonists engage in is drawing a cartoon to recognize and remember famous people when they shuffle off this mortal coil. In the last month, three notables left us, inspiring obitoons. Robin Williams, the country’s class clown, hanged himself and died on August 11, and the nation went into mourning immediately, splashing obituaries and career appreciations on the front pages of newspapers and magazines. William’s face was on the cover of Entertainment Weekly for August 22/29; inside, a 6-page summary of his career, including a full-page photograph. But it was Time, the serious news magazine, that went all out with Williams on the cover and, inside, 16 pages of coverage (a biography by Richard Corliss, an essay by Dick Cavett) including 4 full page photos and one gigantic two-page mood shot. The New Yorker offered several articles in its online incarnation—by Anthony Lane and Andrew Solomon, among others. They all extolled the enchanting magic of Willliams’ appeal, his manic “ricochet riffs on politics, social issues, and cultural matters both high and low” (as the New York Times had it). “He is a human radio,” said Lane, “—spinning the dial in his own head and spewing out all the voices into which he happens to tune, and they follow his remorseless lead ... his shtick—headlong, half desperate, heavy on accents, and mentally elastic to the very brink of madness.” Lane added: “He admitted to [being nervous for a solo performance at the Met in 1986] yet it was the same nerves, plucked like strings, that were making his brand of verbal music, in all its profanity and zeal.” For Richard Corliss, Williams’ mind was “a Whac-a-Mole game housing a million critters of all species and shades, each ready to pop up unbidden.” All of those who wrote about Williams attempted to explain why a man with such gifts would choose to take his own life, to remove himself from the milieu that he so obviously enjoyed. All referred to his troubled psychic life—his addictions, his perpetual depressions. Decca Aitkenhead, writing in the Guardian in 2010, said: “His bearing is intensely Zen and almost mournful, and when he’s not putting on voices, he speaks in a low, tremulous baritone—as if on the verge of tears—that would work very well if he were delivering a funeral eulogy. He seems gentle and kind—even tender—but the overwhelming impression is one of sadness.” Solomon wrote: “Robin Williams’s suicide was not the self-indulgent act of someone without enough fortitude to fight back against his own demons; it was, rather, an act of despair committed by someone who knew, rightly or wrongly, that such a fight could never be won.” Solomon also noted that “the same qualities that drive a person to brilliance may drive that person to suicide.” Highly successful people tend to be perfectionists, “constantly striving to meet impossible standards.” And celebrities are often hungry for love, for the adoration of audiences. “No perfectionist has ever met his own benchmarks, and no one so famished for admiration has ever received enough of it.” Williams was a child in a well-to-do household, but his parents were usually somewhere else. His childhood was lonely. It is not surprising, then, to suppose that his career grew out of an compulsion to provoke laughter: he sought adoration, the applause and laughter of an audience, as a substitute for companionship. Said Solomon: “He played an alien so well because he was an alien in his own mind, permanently auditioning to be one of us. Suicide is a crime of loneliness, and adulated people can be frighteningly alone. Intelligence does not help in these circumstances; brilliance is almost always profoundly isolating. Every suicide warrants mourning, but the death of a figure such as Robin Williams makes larger ripples than most. The disappearance of his infectious glee makes this planet a poorer place.” More than that: “Williams’s suicide demonstrates that none of us is immune. If you could be Robin Williams and still want to kill yourself, then all of us are prone to the same terrifying vulnerability. ... A great hope gets crushed every time someone reminds us that happiness can be neither assumed nor earned; that we are all prisoners of our own flawed brains; that the ultimate aloneness in each of us is, finally, inviolable.” All

true, no doubt. And in more than one of the obitoons produced at Williams’

death, editoonists alluded to the comedian’s essential self: his funny Mr.

Punch face and outlandish comedic gyrations were a kind of mask, behind which

he hid his real self, a lonely somewhat desperately longing sadder self. And that stark portrait on the cover of Time—look closely: is he about to laugh or to sob? As close as many of the eulogistic comments came to explaining Williams’ suicide, they didn’t get it quite right: all missed an important element, perhaps the trigger that set him off. It wasn’t until several days after the shocking announcement of his death that his wife, Susan Schneider, revealed that her husband was in the early stages of Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinson's disease is a "progressive disorder of the nervous system," according to the Mayo Clinic, that primarily affects a patient's movement. It often starts with a small tremor in the hand or muscle stiffness and gets worse over time. Early in the course of the disease, the most obvious symptoms are movement-related; these include shaking, rigidity, slowness of movement and difficulty with walking and gait, a loss of balance and slurred speech. Cognitive disturbances can occur in the initial stages of the disease, and sometimes prior to diagnosis, and increase in prevalence with duration of the disease. Fluctuations in attention and slowed cognitive speed are among other cognitive difficulties. And a general rigidity develops, including an inability to display facial expressions. Think about that. The funny man loses his antic physicality and his ability to make the faces that make us laugh. Williams’ knowledge of what lay ahead, combined with his habitual depression, doubtless tipped the scale. Other performers with Parkinson’s—Michael J. Fox, cartoonist Richard Thompson—have elected to live with the disease, to fight it, to crusade for the research that will defeat it. But these other performers do not define themselves—find their own salvation—in their performances as Williams did. He probably saw that his life with Parkinson’s was life without shtick, and that, for Williams, was no life at all. A Williams friend and admirer noticed that when just he and Williams were together, the comedian was quiet and almost reserved. But add another person for an audience of two, and Williams was “on.” Comedy flowed. In her New Yorker piece, Adrian Nichole LeBlanc reports what comedians usually said when she asked them what they’d be doing if they weren’t doing comedy. “I’d be dead,” most answered. Williams, faced with an end to the capabilities that made him funny, knew he was dead.

THE DAY AFTER WILLIAMS DIED, the last of the Golden Age of Hollywood legends, Lauren Bacall, died. But her death, despite her legend, was so overshadowed by the sadness of Williams’ final terrible choice that it was almost not noticed. In the same issue of Time that carried that 16-page tribute to Williams, Bacall got a single full-page color photograph and three paragraphs. And almost no editorial cartoonist eulogized her passing. That was too bad. And it seemed to me a gross miscarriage of decorum to accord so large a figure so small a tribute.

So I’ve tried here to make up for the slight by collecting some of the iconic pictures of Bacall, pictures that remind us with her famous sultry look of her husky voice—and of her marriage to Humphrey Bogart, another larger-than-life actor. Theirs was THE Hollywood love story: a beautiful young ingenue on the cusp of her career falls in love with her leading man while making a movie with him, and they marry into happy ever aftering. Bogie, as Bacall invariably calls him, died too soon: they were married only a dozen years, and yet her 1978 autobiography, By Myself—written at least 20 years after Bogie’s death—is almost all about her and Bogie. THE Hollywood love story. But Bacall was more than that sultry siren. She survived Bogie’s death, raised three children, and made a great career for herself on Broadway. Richard Brody recognized an aspect of her life that deserves remembering: “For all the mighty figures who populated Hollywood studios, almost nobody else could stand up to her. She was meant to play Presidents and C.E.O.s, editors-in-chief and visionary directors. ... Bacall was bigger than her career. She started young and stayed ahead of her time, and her greatness—her mighty personal presence and her diverse body of work—carries a shadow of unfulfillment and even tragedy.” The last paragraph of her book gives us the Lauren Bacall who survived and triumphed: “I’m not ashamed of what I am—of how I pass through this life. What I am has given me the strength to do it. At my lowest ebb, I have never contemplated suicide. I value what is here too much. I have a contribution to make. I am not just taking up space in this life. I can add something to the lives I touch. I don’t like everything I know about myself, and I’ll never be satisfied, but nobody’s perfect. I’m not sure where the next years will take me—what they will hold—but I’m open to suggestions.” Open to suggestions. Life goes on. I realize that it’s scarcely fair to compare the grossly different extents of the news media’s coverage of these two deaths. Lauren Bacall died just a month shy of her 90th birthday. She’d led a full and mostly happy and accomplished life: she was old, and old people die. We were, so to speak, expecting it. On the other hand, Williams, whose achievement was more spectacular—more the stuff of sky rockets and roman candles—was only 63 and presumably had many years before him. On the basis of age alone, his departure was therefore stupefying, and the manner of his going augmented the shock. Still, on the face of it, the treatment of Williams’ death seems excessive. Particularly in a week’s context that includes the death of another legend. Unfair, perhaps, to make the comparison, but Bacall did not give up. Ever. Still, I’m not sure that Williams did. I think he’d decided that with Parkinson’s, he was already dead.

AND THEN we

have the irrepressible Joan Rivers, who achieved repression by dying

September 4, almost a month after our other two celebrities. Rivers was another

show-biz legend, a pioneer whose vaulting success as a female comedienne paved

the way for a generation of funny women. Except none of them were like Rivers.

In her rapid-fire delivery—in her endless invention—she was very nearly a

female version of Robin Williams. Can we talk? Because she was mistress of the comedic insult, let’s remember her by citing some of her more memorable lines—the ones that didn’t insult anyone but herself: I hate thin people; 'Oh, does the tampon make me look fat?' Grandchildren can be so f-cking annoying. How many times can you go, ‘And the cow goes moo and the pig goes oink’? It’s like talking to a supermodel. I now consider it a good day when I don’t step on my boobs. My best birth control now is just to leave the lights on. I’ve had so much plastic surgery, when I die they will donate my body to Tupperware. All my mother told me about sex was that the man goes on top and the woman on the bottom. For three years my husband and I slept in bunk beds. Women should look good. Work on yourselves. Education? I spit on education. No man is ever going to put his hand up your dress looking for a library card. I wish I had a twin, so I could know what I'd look like without plastic surgery. People say that money is not the key to happiness, but I always figured if you have enough money, you can have a key made. I don’t exercise. If God had wanted me to bend over, he would have put diamonds on the floor. The first time I see a jogger smiling, I’ll consider it. I’m no cook. When I want lemon on chicken, I spray it with Pledge. At my age, an affair of the heart is a bypass. Half of all marriages end in divorce—and then there are the really unhappy ones. You know you’re getting old when work is a lot less fun and fun is a lot more work. I’ve learned to appreciate landmark moments like the Emmy I won in 1990, one of the best moments of my career. Unfortunately, when I went to pawn it, it turned out not to be gold. But her insults of others were just as funny—: Elizabeth Taylor fat? Her favorite food is seconds. Boy George is all England needs—another queen who can’t dress. I’ve never seen a 6-month-old so desperately in need of a waxing. (About North West, daughter of Kanye West and Kim Kardashian) Ted Rall, who didn’t do a cartoon about Rivers’ death, made a statement: “Joan Rivers is dead, and you have to make fun of her because if you don’t, she’d be mad.” But some were not in the mood. To them, Rivers’ comedic insults were mean-spirited and nasty. Maybe. I asked a friend of mine, cartoonist and comedy writer Karyl Miller, what she thought, and she said: “I say it was cruel, bad taste AND funny. And that's acceptable now, in these nasty no-holds-barred times.”

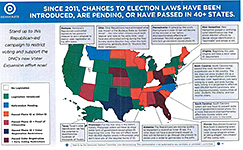

FINALLY, in our tireless effort to inform and elucidate, here are some maps that show where we stand on various issues—the battleground states in the forthcoming election, voter registration, health care, and Russia’s invasion of eastern Europe (formerly, the western edge of the Soviet Union).

Print them out and tape them to your forehead for future reference.

WE’RE ALL BROTHERS, AND WE’RE ONLY PASSIN’ THROUGH Sometimes happy, sometimes blue, But I’m so glad I ran into you— Tell the people that you saw me, passin’ through

Tony Auth, 1942 - 2014 Auth’s cartoons have often been among those reviewed at this website; one appears in this posting, too. At the website of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, Auth’s colleagues posted the following:

Farewell, Tony Auth Tony Auth’s colleagues and friends in the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists are profoundly saddened by his death. Tony was one of a small handful of that magnificent generation of 1960s and 1970s cartoonists who re-created what we do today. A brilliant, original editorial cartooning voice is gone. Tony’s drawing style was unique. The fluidity, grace, and simplicity of his line was a marvel, and his strong editorial positions stood out for four decades. There was no mistaking an Auth cartoon for others, ever. A master of irony and juxtaposition, Tony won the 1976 Pulitzer Prize, along with many other national awards during his long tenure at the Philadelphia Inquirer. He was generous with his time with younger cartoonists, and pursued many different artistic avenues of expression, from comics to books, with an enviable grace and ease. Tony’s style flowed from his very loosely constructed roughs, which he tried to keep as close to the original drawing as possible through a light table. The result was an inimitable look admired universally by his peers. The AAEC family extends its deepest condolences to Tony’s wife Eliza and his two daughters, to whom he was devoted.

The following appreciation of Tony Auth was written by Bonnie L. Cook, a colleague of Auth’s at the Philadelphia Inquirer. Tony Auth, 72, of Wynnewood, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist and mainstay of the Inquirer's editorial page for four decades before resigning in 2012 to become a digital artist, has died. Auth had been under treatment for brain cancer, and earlier this month was placed in hospice care, his family said. He died Sunday, September 14, just days after his friends announced a fundraising effort for a Temple University archive devoted to his work. Auth's remarkable career began in 1971 when the fledgling artist from California flew in to Philadelphia to interview for the position of editorial cartoonist. Over the next 41 years, Auth would use his rapier wit in thousands of carefully rendered drawings to kindle discussion on the political and cultural currents of the day. Few could view an Auth cartoon and stay mute. “As a cartoonist, he was a gem - a journalist who could evoke reactions from readers ranging from anger and indignation to elation and illumination," said Inquirer Editor William K. Marimow. Auth drew cartoons about world affairs, national issues, sports, Philadelphia politics - there was no one better at piercing the veils of self-righteous politicians. "Depending on the occasion, his work might be whimsical, feisty or festive," Marimow said. Auth's impressive portfolio - he produced five cartoons a week - was a Philly staple when breakfast meant coffee, bacon and eggs, and the morning paper. As the fortunes of the newspaper industry waned, he still reached a national audience through syndication. Perhaps more than any other Inquirer journalist, Auth's distinctive voice defined the paper's soul and crusading spirit, said Stan Wischnowski, the Inquirer's editor in 2012 who is now Interstate General Media's executive vice president for news operations. "His passion for standing up to those in power - including eight American presidents and seven Philly mayors, as well as his voice for the powerless - were trademarks that set him apart," Wischnowski said. Outside Philadelphia, Auth was the face of the Inquirer for 41 years, said Rick Nichols, a friend and former coworker on the paper's editorial board. In 1976, Auth, then 34, won the Pulitzer Prize for cartoons published in 1975. Among those Auth cartoons cited by the Pulitzer committee was one showing Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev singing in the midst of a vast American wheat field, "O beautiful for spacious skies, For amber waves of grain." The July 22, 1975 cartoon skewered the United States for becoming the dupe of the Soviet Union in an unpopular grain deal that raised prices on the home front. Auth was a Pulitzer finalist in 2010 for his 2009 work. He also earned the Thomas Nast Prize in 2002, the Herblock Prize in 2005, five Overseas Press Club Awards, and the Sigma Delta Chi Award for Distinguished Service in Journalism.

A vanishing breed When Auth joined the Inquirer in 1971, there were about 200 editorial cartoonists working in American daily journalism. By 2010, three-quarters of them had disappeared, dismissed as luxuries in a cost-cutting age. Auth produced some of his best work during that period. In 2009, for example: ■ When Sonia Sotomayor was nominated to the Supreme Court, Auth depicted white male lawmakers within the clubbiness of Congress, sniffing that in ruling, she might favor "those who share her background." ■ When the Pope said that prophylactics were not the answer to Africa's AIDS crisis, he set the pontiff amid a sea of the afflicted, saying, "Blessed are the sick, for they have not used condoms." ■ And when suburban Philadelphia swim club owners abruptly showed a group of African American children the door, Auth drew a sign that read: "No running, diving, food, beverages, blacks." But in March 2012, tired of the daily grind [and the turmoil involved in a change of the paper’s ownership, the Associated Press reported] and citing the need to try different kinds of projects, Auth took a buyout. He joined WHYY's NewsWorks.org, the website directed by Chris Satullo, a former Inquirer editorial page editor. "It's going to be a work in progress," Auth said. "But I will be continuing to do iPad movies and two or three political cartoons a week for syndication. I'm going to be really busy." William J. Marrazzo, WHYY president and chief executive, called Auth "a class act," and said that even as he grew gravely ill, he maintained an amazingly positive attitude and always seemed to have a "twinkle in his eye." "Tony Auth was a great cartoonist, a fine journalist and an even better friend," Satullo said. Auth's departure shocked the Inquirer's news staff. "Tony's insight and perspective are valuable to the editorial board. His decision to leave represents a great loss that the paper will feel for a long time," said Harold Jackson, current editor of the Inquirer's editorial page.

Retrospectives In recognition of his body of work, a retrospective was assembled and shown from June through September 2012 at the James A. Michener Art Museum in Doylestown. More than 85,000 attended. The 150 items—cartoon drawings, paintings, sketches and children's book illustrations—mapped the life and times of an illustrator in late 20th century and early 21st century America, guest curator David Leopold wrote. As he went through Auth's drawings, Leopold was struck by their optimism. "I think the common idea people have of a cartoonist, is that they have a lot of bile at the world," he said. "Tony is not full of bile; he is a very happy, nice guy. He might not show us, or our leaders, at our best, but there is always his hope, that we will all be better." Gwen Shrift, writing for phillyburbs.com, attended the show. "I kept hearing chuckles in customarily sedate galleries at the Michener. Even old cartoons still hit the mark," she wrote, and concluded: "In newspapering at its best, the editorial cartoonist got to the point ahead of everyone else. The Michener exhibit reminds us that Auth never squandered the opportunity." Outside the newsroom, and even in it, few knew how Auth managed to come up with a clever idea each weekday and translate it into a cartoon. Jules Feiffer, a friend of Auth's and a 1986 Pulitzer Prize winner for editorial cartooning, said that for each cartoon that was published, Auth drew four or five rough sketches to show his editors. "He loved being part of the newspaper experience, the journalistic gestalt. Five days a week, five ideas a day, that's 25 a week. Tony did it just about as well as anybody ever did. He never never stopped doing his homework. He was always gathering information. An important part was his own personal politics. His ideas came out of his own attitude and politics, and his great humanity and compassion," Feiffer said. When working, Auth would assume the perspective of "a bemused, often angry comic historian," Feiffer said, adding: "Irony, never a favorite form with Americans, is his meat and potatoes. He is not smug, and though he can be mean, he is never mean-spirited." Auth attended daily Editorial Board meetings, listened to colleagues debate the day's news, watched tv, listened to public radio, read widely, searched online, and talked on the phone. Later, he would disappear into his airy office and begin to draw. "He would show me and a couple of other people his rough drafts. Basically he wanted you to applaud them," his friend Rick Nichols recalled with a chuckle. "He would come up with these wonderful visuals that were so arresting. He always said, 'If you don't get it instantly, it's not a strong work.' " In the afternoon, Auth carried the finished cartoon to the paper's composing room and laid it on the engraver's table. He invited the printers to comment. They did, loudly. He smiled and listened. Once the cartoon became public, reaction poured in. Readers phoned and wrote letters to the editor. They e-mailed and commented on The Inquirer's website, philly.com. Some of the responses were glowing, others downright profane. ■ "Just wanted to give you a big thanks, a high-five, and giant hug for your cartoon . . . You are brave, very brave," wrote Susan M. in 2009. ■ "Sir, that is a brilliant cartoon. Any chance that I could get it on a t-shirt?" Nick H. wrote. ■ "Your willful and partisan ignorance is truly astonishing," wrote John F. the same year. "Auth, you are such a useless --," Louis F. wrote.

An Ohio native Born William Anthony Auth Jr., in Akron, Ohio, Auth was raised there and in Los Angeles. He was bedridden for eight months at age 5, and during that time, he began drawing, he wrote on his website, www.tonyauth.com. He was especially intrigued by comic strips, children's books, and radio dramas. Auth graduated from the University of California-Los Angeles (UCLA) with a bachelor's degree in biological illustration in 1965. While there, he worked on the Daily Bruin, the college newspaper. After graduating, Auth became a medical illustrator at Rancho Los Amigos Hospital, a teaching hospital affiliated with the University of Southern California. He began drawing political cartoons, initially doing one a week for an alternative weekly newspaper. Then, after receiving encouragement from cartoonist Paul Conrad at the Los Angeles Times, he worked his way up to drawing three political cartoons a week for the UCLA Daily Bruin.

A mentor As he became famous, Auth did not close himself off to other cartoonists. He enjoyed mentoring them. Signe Wilkinson was an art student in the late 1970s when she was invited to visit Auth in his office on the fifth floor at 400 N. Broad St. She would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize in 1992 for her work at the Philadelphia Daily News. "On a hot summer day, I arrived and was parked on a director's chair underneath an intimidating row of his framed cartooning awards, dripping from nerves as well as heat. He kindly greeted me and talked as if I already was a cartoonist. He treated all the other cartoonists in our tiny fraternity the same way," she recalled. Auth published two collections of his political cartoons, and illustrated 11 children's books. He learned to make movies with a $5 iPad application. "He always had a radio voice, and he narrated them so that the listener could be part of the drawing of the cartoons," Leopold said. He was married to Eliza Drake Auth, a realist landscape and portrait painter. The couple settled in Wynnewood and had two daughters. Auth loved spending time at the family's Shore house at Ocean Gate, tinkering on a sailboat, or mixing "dark-and-stormy cocktails for friends," said Paul Nussbaum, an Inquirer reporter. "The sea seeped into many of his cartoons, which often featured shore scenes, sailboats, or his all-time favorites - pirates and Vikings," Nussbaum said. Surviving, besides his wife, are daughters Katie and Emily. Funeral arrangements were pending. Contributions may be made to the Tony Auth Archive Fund, c/o the Philadelphia Foundation, 1234 Market St., Suite 1800, Philadelphia, Pa. 19107, or via: http://bit.ly/1qORq5o

To find out about Harv's books, click here. |

||||||||

send e-mail to R.C. Harvey Art of the Comic Book - Art of the Funnies - Accidental Ambassador Gordo - reviews - order form - Harv's Hindsights - main page |

1.jpg)

2A.jpg)

2B.jpg)

3.jpg)

4.jpg)

5.jpg)

6.jpg)

7.jpg)

8.jpg)

9.jpg)

10.jpg)

11.jpg)

12.jpg)

13.jpg)

Williams.jpg)

Bacall1.jpg)

Bacall2.jpg)

JoanRivers.jpg)