|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Opus 327 (July 16, 2014). Down the rabbit hole this time, we ponder the current state of what has become the comic-con “industry,” report on the recent success of the Denver Comic-Con and look forward to the San Diego Comic-Con July 23-27. We also celebrate the careers of two giants who died last month, The New Yorker’s Charley Barsotti and Etta Hulme, first lady of editooning. And we review the horrors of the last month as seen through the eyes of some of the best editorial cartoonists, plus reviewing Southern Bastards, Dicks, and United States of Murder and a few other recent funnybooks. And more, much more—including a report that Dick Tracy is on a four-month search for Little Orphan Annie. Astounding. Here’s what’s here, in order, by department—:

NOUS R US Watterson’s Pearls Appearance Stirs the Multitudes Michael Uslan Says Farewell to Betty and Veronica Mister Magoo Is Back PlanetPOV Website Caught Stealing Editoons Dick Tracy Searches for Little Orphan Annie Neil Gaiman Visits Syrian Refugee Camps Playboy Publishes a Lame Graphic Narrative

Ted Rall Fired Stephan Pastis Maintains Exacting Schedule Parade Magazine Briefly Produces a Small Comic Book Funky Winkerbean Promotes San Diego Comic-Con Comic Book Artists Create Faux Comic Book Covers for Batiuk Terrible Cartoons: Cyanide & Happiness, Nameless NY Times Strip

MORE ABOUT OTTO SOGLOW’S LITTLE KING

COMIC-CONNED The State of the Comic-Con Industry Denver Comic-Con Report (amply illustrated)

EDITOONERY Rounding Up Some of the Best of the Month Religious Freedom Teeters More Guns Won’t Help

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Marvel’s 75th Anniversary Logo Scott McCloud’s Cover for The Sculptor

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL Sex and Other Taboos Broken in Today’s Strips

Civilization’s Last Outpost Redskins

BOOK REVIEW Cartoon Monarch: Otto Soglow & The Little King

Collectors’ Corniche Carl Barks Self-portraits

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Southern Bastards Five Ghosts The Massive Dicks Time Lincoln Continental Sandman Overture No.2 United States of Murder, Inc.

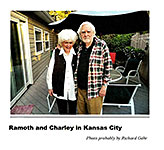

PASSIN’ THROUGH Charles Barsotti Etta Hulme Frank Cummings

Our Motto: It takes all kinds. Live and let live. Wear glasses if you need ’em. But it’s hard to live by this axiom in the Age of Tea Baggers, so we’ve added another motto:.

Seven days without comics makes one weak. (You can’t have too many mottos.)

And our customary reminder: don’t forget to activate the “Bathroom Button” by clicking on the “print friendly version” so you can print off a copy of just this installment for reading later, at your leisure while enthroned. Without further adieu, then, here we go—:

NOUS R US Some of All the News That Gives Us Fits

BILL WATTERSON’S SURREPTITIOUS RETURN to the funnies pages of the nation’s newspapers by invading the stick-figure precincts of Stephan Pastis’ Pearls Before Swine the first week of June created an unprecedented uproar. A clamour among millions, it quickly became that most desirable of occurrences in the entertainment world: it was an “event,” saith Michael Cavna at ComicRiffs.com. Pastis, Watterson’s dupe in the enterprise, was aghast. “It’s just massive,” Pastis told Cavna on Saturday, June 7, the last day of the Watterson Week, “—the biggest thing I’ve ever been a part of. I mean, I knew there would be a big reaction but didn’t know it would be this big.” “As

of Saturday morning, Pastis had set the digital world ablaze,” Cavna wrote:

“His blog account of how the collaboration came into being was the No.1

blogpost worldwide on WordPress, buoying him to the morning’s top blog overall. Update: Pastis tells me his personal blog’s

Watterson post has been viewed more than 3-million times.” And his syndicate’s website, GoComics.com, “was barely holding up beneath the sudden flood of visitors. (Universal Uclick is the syndicate for both Pearls and Calvin and Hobbes.) Update:On Saturday, June 7, the GoComics site received 6.1-million page views, syndicate chief John Glynn told ComicRiffs — a spike of 4-million more than the previous Saturday.” Rocking the entertainment world just a month after the New York Post dropped its entire comics section (admittedly, just a measly seven comic strips)—creating what some of us saw (and still see) as an unhappy harbinger for the rest of the daily newspaper fiefdom (see Opus 326)—Watterson Week was, we trust, welcomed throughout the syndicate business as a vivid—astonishing, stupendous—demonstration of the enduring appeal of newspaper comic strips. Every syndicate salesman on the planet ought to be out there, visiting feature editors and waving the Internet statistics in their faces.

ODDS & ADDENDA Michael Uslan, who has already wreaked havoc in the Archie Universe by getting the Riverdale redhead to marry both Betty and Veronica, says in Comic Shop News No.1407 that he’s about to do it again: “I’m doing Farewell Betty & Veronica which is going to change the dynamics of those comic books and Riverdale itself.” In 53 theatrical animated cartoons in the 1950s, near-sighted (well, almost blind) Mister Magoo bumbled into vast acreages of trouble because of his poor eyesight, and now he’s back: voiced in a cheerful adenoidal mumble by Jim Backus, you can find him in a 4-DVD box, “Mr. Magoo: The Theatrical Collection (1949-59).” A website called PlanetPOV was posting editorial cartoons by the bucket but doing it without getting permission from the cartoonists—and without offering payment. Members of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists protested, and PlanetPOV started asking permission but offering no recompense. Dick Tracy is only partway through the longest continuity that any strip has foisted off on us in several decades (except 9 Chickweed Lane, which a year or so ago ran a story for nearly a year; expertly done, too). Writer Mike Curtis and cartoonist Joe Staton started the story on June 7, and it will last through September. The special dispensation for length in this age of 4-week continuities is doubtless because in this story, Tracy goes looking for Annie Warbucks, the famed heroine of Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie, a strip that ended in June 2010 (albeit not very definitively: she was missing in Guatemala in the last strip, with a caption that was open-ended enough to permit the orphan redhead to return, should the stars be reconfigured. She’ll show up in Tracy, but, as yet, without any hint that her own strip might be revived.) The continuity will feature several other LOA fugitives—Daddy Warbucks, the Asp, Punjab, even the mysterious Am (rumored, in some fanatic parts, to be Gray’s version of the Almighty Himself). And Staton will alter his drawing style to mimic Gray’s. Meanwhile, Curtis is hoping this cross-over will inspire another—namely, a meeting between Tracy and Batman. “Having America’s two greatest crime fighters meet each other would be fun,” he told George Gene Gustines at the nytimes.com, “—in fact, we have a plot if it happens.” We can hope. Under the auspices of the United Nations Refugee Agency, author Neil Gaiman traveled to Jordan in May and visited Syrian refugee camps to see for himself the situation faced by Syrians who’ve fled the war in their native land. He writes: “I am struck by how fragile civilization is. Even if the war was over, many people couldn’t go home immediately because home isn’t there. Sometimes the house that people lived in isn’t there. Sometimes the town or district isn’t there. Things that you think of as being so permanent are fragile and permeable. And I’m as struck by the things that you think of as fragile, like people, being so tough and so resilient. These people have endured tragedies and ordeals that are almost unthinkable. And yet they are smiling. ... How incredibly fragile are the systems within which we exist. And how proud I am of being human.” And Time magazine’s June 9 issue has a devastating report, with searing photos, “Has Assad Won?” Subtitled “In Syria, Victory Is Written in Ruin,” the report details some of the wholesale destruction in “rebel” areas in bitter contrast to “life as usual” in sumptuous Damascus and includes a short but impressive history of how it all came about. The July/August issue of Playboy (another of its fraudulent “double issues” with only 30 percent more pages than usual allotment) contains a 6-page graphic narrative. Written and drawn in black and white by David Lapham based upon artist Joe Andoe’s so-called autobiography, the story, such as it is, concerns a drunken ride Joe took with a couple friends which got him thrown in the tank for wrecking the car and trying to beat up a local citizen. Joe gets out of jail and promptly screws his girlfriend in the back seat of the wrecked car while thinking, at the same time, of the unsanitary behavior of one of his cellmates. The juxtaposition of present and memory is competently done, but the story is otherwise wholly undistinguished. Hugh Hefner has published a couple other efforts along these lines, similarly undistinguished. Makes me think he doesn’t really understand graphic narratives.

RALL OUT ON THE STREETS AGAIN Less than a month into his new job at the Web’s PandoDaily, Ted Rall, the ever-outspoken gadfly of editorial cartooning and Internet columning, was fired. His PandoDaily gig was the first regular job with a predictable paycheck that the notorious freelancer has held in his cartooning career (see Opus 324). No reason was given for the termination, but Rall’s dismissal was accompanied by another, that of columnist/reporter David Sirota, known, like Rall, for his aggressive journalism. According to Nitasha Tiku at valleywag.gawker.com, “Sirota recently broke a big story about Chris Christie's administration awarding pension contracts to hedge funds, private equity groups, and venture capital firms whose employees donated to the governor's reelection.” Rall had similarly ruffled feathers by reporting that “some Uber drivers made less than minimum wage, contrary to the company’s claims.” The general supposition swirling around the news was that PandoDaily’s investors were uncomfortable with the direction these two were taking in their reporting. Pando factotums denied any such thing. And Tiku quotes Rall as saying: “"I loved working for [editor] Paul Carr. I had complete editorial freedom. When I wrote stuff that he disagreed with, he not only posted them without comment, he promoted them. I thought, 'Here's a guy with a lot of integrity.'" Neither Rall nor Sirota had any advance notice of their impending dismissal. Rall told Tiku that the decision was “really truly out of a clear blue sky. I literally never got anything but A-triple-plus reviews.” At first, neither of the newly unemployed would comment on their firing. Later, Rall reportedly said: “Reason given was my work was too political, strayed from core mission, covering tech.” But, said Tiku, “that complaint about the lack of tech coverage seems tenuous considering that Sirota and Rall both cover the intersection of tech and politics, taking a broader perspective than your standard press release reblog, which is what the NSFWCorp acquisition [by Pando] promised. The flow of tech money into politics is an increasingly vital topic. Earlier this month, for example, Chris Christie traveled to Silicon Valley for fundraising.”

THE STEPHAN PASTIS MACHINE Stephan Pastis seems a glutton for work. Not only does he do a daily comic strip—traditionally a recipe for destroying one’s spare time—and collaborate with the profession’s most reclusive retiree, he also writes books. Inspired, no doubt, by Jeff Kinney’s Wimpy books, Pastis has published three hardcover books about Timmy Failure, “a comically clueless boy who runs the Total Failure detective agency with a 1,500-pound polar bear named Total,” reports Sally Lodge at publishersweekly.com. The first book in the series, the 2012 debut title Mistakes Were Made, “ spent more than 20 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and has 350,000 copies in print in North America.” In addition to producing the strip and its reprint tomes and the Timmy Failure books, Pastis spends hunks of time traveling around the country doing signings and otherwise promoting his products. Lodge reveals how Pastis balances his workload: the secret is rooted in his carefully structured creative regimen. “Each week, Pastis creates 10 Pearls Before Swine comic strips between Monday and Thursday, thereby producing three extra strips per week, or more than 150 a year. ‘That’s buying me five months when I can do all the other things – write the novels, do the tours and other promotion for the books and strip, and have a life,’ he explained.” Lodge continues: Pastis’s success at switching mindsets between Pearls and Timmy Failure depends on just that: for him, it’s a total switch. The endeavors are so different from each other, the author said, that he “totally separates them out,” writing his novels full-time in six or seven weeks. “I write the books in one run and then return totally to Pearls,” he said. “When you do anything creative, you really have to live entirely in that world. I think my ability to do that is what makes me such a bad dinner guest. I’m always looking over someone’s shoulder, taking in stuff around the room, immersed in the world of whatever I’m writing about, and keeping the characters completely in my head.” Does Pastis agree that he’s firmly on Team Kid? “Oh man, I totally am!” he said. “I’m 12 years old in my head. With the Timmy Failure books, I write what makes me laugh, and as it turns out, what I find funny, 12-year-olds find funny. And the other thing is, though I didn’t set out to do it, when I step back and look at my books, I realize that in many ways Timmy is really me as a kid. I didn’t do that on purpose. When I began the first book I just sat down and wrote, and decided I’d figure it out later.” Pastis remains committed to both Timmy Failure and Pearls. “I feel that they are in my blood, and I’d do both even if nobody paid me,” he said. “I never feel burdened or overwhelmed by my work. People tell you to find something you love for a career, and I have. That makes me feel very lucky.”

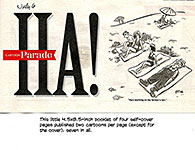

SUPPLEMENTAL REVIVAL OF NEWSPAPER CARTOON The

Sunday supplement magazine Parade has been remiss considerably in the

last year or so— reducing the number of cartoons it runs, sometimes to nothing.

Weeks go by with no "Cartoon Parade." I've been keeping score and

posting the shameful results for a couple years. And just this month, my

protest has apparently borne fruit: July 6's Parade contained a small

4.5x8.5-inch booklet of four self-cover pages, printing two cartoons on every

page (except the cover, seen hereabouts) for a grand total of seven cartoons! HOOOrah! They've found a way to publish cartoons without reducing the magazine's interior capacity for publishing such world-changing articles as what sort of hot dog to serve on July Fourth. This is clearly an advance for Western Civilization as we know it. And we should encourage newspapers to think along similar lines. Newspapers, always jealous of the amount of space they must poach from “covering The News” to print the comic strips that are more popular with readers than The News, could satisfy both their journalistic impulses and reader interests by publishing a daily comic book of each day’s funnies. What a concept! Update: Alas, no Cartoon Parade booklet the next week. Back to one dinky cartoon at the bottom of an interior page. Sigh. But we could dream. And still do!

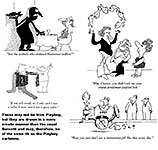

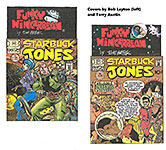

FUNKY PROMOTES THE CON Just in time to join in the general rush to promote the San Diego Comic-Con, Tom Batiuk devoted a two-week continuity in his Funky Winkerbean strip to comic books as treasures. Running the two weeks before the Con, the story regales us with a search for a long-lost comic book. “It started,” said Batiuk, “with the fact that in the strip, Funky's stepson Cory is in Afghanistan. I had done some stories with him over there and I wanted to continue that but I also wanted to do a homefront story about what it was like for the parents. I was casting about for ways to get into this story when I thought of what if Holly—Cory's mother—discovered that he had a comic book collection and there were some comics missing. As a way of staying in touch with him and feeling like she was doing something, she would go out and collect the missing comics for him.” The comic book in question concerns the adventures of Starbuck Jones, a space-traveling hero that Batiuk invented when he was in the fifth grade. One thing led to another, and Batiuk realized that the erstwhile fictional comic book had to appear in the strips. So he contacted several cartoonists, beginning with Joe Staton, to see if they’d draw a suitably spectacular Starbuck Jones cover. And they did— Bob Layton (his cover is pictured near here), Neil Vokes, Michael Gilbert, Mike Golden, Norm Breyfogle, and Terry Austin (whose cover joins Layton’s in our exhibit; the other covers can be found somewhere at web.mail.comcast.net). Batiuk

gave them complete freedom—“draw what you want”—with the unexpected consequence

that Austin’s Starbuck Jones is a monkey. In

the course of her quest, Cory goes to the Sandy Eggo Con and rummages through

bins of old comics looking for the one issue of Starbuck Jones that will

complete Cory’s collection. Although he spilled this many beans to Alex Dueben at web.mail.comcast, Batiuk also promised that there’s more to come. Turns out that he invented a lot more characters while in the fifth grade—among them, The Amazing Mr. Sponge. Stay ’tooned.

TERRIBLE CARTOONS DEPARTMENT Previews, the Diamond catalog,

listed in its May issue a new 200-page book reprinting a webcomic called Cyanide

& Happiness that will be released in August. The comic strip is

produced by Kris Wilson, Rob Denbleyker, Matt Melvin and Dave

McElfatrick. It takes four guys to produce a stick-figure comic strip. Wow.

Here’s a portion of the ad. But

the minimalist art in C&H at least doesn’t hurt your eyes. In fact,

it is almost a symphony in simplicity (but then, it should be with a whole

orchestra to produce it). The comic strip cranked out weekly for the New

York Times’ Week in Review section by David Rees (who writes it) and Michael Kupperman (who claims that what he vomits onto the page is

“artwork” of some sort) makes my head hurt it’s so badly drawn. It’s a

genuinely painful experience as you’ll soon (if you’re not careful to avert

your eyes) suffer. The one we’ve reproduced here at your elbow was actually rejected

by the Times. But not because of its execrable artwork. No, it was the

strip’s “message,” which the Times deemed “too sensitive” to publish.

The issues addressed: men’s rights activists, infantile misogyny, Internet

harassment and pissing in your pants, according to Salon.com. In an e-mail to Salon, Kupperman said he was “genuinely shocked” that the comic was rejected. “What really blew my mind this week was that they didn’t just reject the script; they declared that the subject itself was too sensitive to be prodded at with humor. Frankly, I genuinely believe they didn’t understand it, and that made them nervous.” Maybe. Maybe the Times editors found the notion of raping feminists as an act of revenge to be repulsive. Dunno. But the most astonishing aspect of this episode is that it reveals what the Times thinks comic strips are—namely, monumentally bad drawing. No wonder the Times doesn’t run comic strips: it can’t recognize the artistry of the medium. We’re in bad shape, kimo sabe, if Cyanide and Kupperman are passing themselves off as examples of the cartoonist’s art.

Fascinating Footnit. For even more comics news, consult these four other sites: Mark Evanier’s povonline.com, Alan Gardner’s DailyCartoonist.com, Tom Spurgeon’s comicsreporter.com, and Michael Cavna at voices.washingtonpost.com./comic-riffs . For delving into the history of our beloved medium, you can’t go wrong by visiting Allan Holtz’s strippersguide.blogspot.com, where Allan regularly posts rare findings from his forays into the vast reaches of newspaper microfilm files hither and yon.

Quotes and Mots “Be wise because the world needs more wisdom. And if you cannot be wise, pretend to be someone who is wise, and then just behave like they would.”—Neil Gaiman “Problem of the world: fools and fanatics are always so full of passionate certainty.”—Television show Congress manages to avoid a recall despite being filled with faulty air bags.—RCH, revising someone else’s quip (sorry: forgot whose).

LITTLE KING REDOUX It was bound to happen: my legendary ineptitude with mechanical and electronic appliances resulted in my posting a week or so ago an incomplete history of Otto Soglow’s Little King. I was unable to give the date of the rotound monarch’s first appearance in The New Yorker. And I should have been able to supply this vital information: some years ago in my continuing crusade to make my Book Grotto the most complete print-based reference library on comics and cartooning, I bought the Complete New Yorker Cartoons tome, which included on CDs the entire cartoon content of the magazine from its birth in 1925 until the publication date of the book, 2004. The first Little King is not in the print volume. So I tried the CD. Alas, there I met my digital Waterloo: I needed Adobe 6, but my new computer has a more recent version that couldn’t read the disk. I could have tried the website the CD recommended, but, as any inept septuagenarian can tell you, I was reluctant. Frozen with fear of the unknown, actually. So I didn’t go online. But then a few days latter, I descended to my studio wherein my old computer languishes. It, antique that it is, had Adobe 6, so I was able to activate the CD and find the first of Soglow’s Little Kings. But since the CD is programmed to prevent me from printing any of the cartoons, I must resort herewith to verbal description of this historic event; to wit—: In the opening panel of the first, published June 7, 1930, a footman tells the King: “Your bath is ready, your majesty.” Followed by one footman, the King follows another one to the palace swimming pool. At the edge, one footman helps the King off with his robe while the other footman jumps (fully uniformed) into the pool, creating a splash that sprays the naked King. That’s his bath. Shower, rather. The footmen towel the King dry; then they hold his robe for him, he slips it on, and all three leave in the reverse of the procession that brought them to the pool. The Little King did not appear again until the next year. On March 14, his minions tell him that the cornerstone laying is imminent, so he goes there—in his carriage with an accompanying parade of footmen, bands, and marching soldiers. At the site, King takes off his robe to reveal workman’s garb underneath, and he approaches the cornerstone with a trowel in hand. He will lay the cornerstone. The

King then appears just about every other week for the rest of the year.

Reprising a couple illustrations from our Hindsight essay on Soglow, here is

the third and the eighth Little King. As I mentioned in Hindsight, Harold Ross, the editor and founder of The New Yorker, clearly liked Soglow’s silent sovereign: he asked for more, but, as I said, he was picky about his selections, so it evidently took ten months for Soglow to produce another Little King that Ross liked—namely, the cornerstone cartoon. Since the King began at that point appearing biweekly, we may assume that Ross let a little inventory build up before re-launching the feature on March 14. In the meantime, Soglow cartoons without recurring characters appeared in virtually every issue of the magazine during the interim. In subsequent 1931 appearances: the Little King is importuned by two heavily uniformed and extravagantly gesturing factotums after which, he buys life insurance; finds mice in his carriage; sets up a scarecrow, dressing it with his own royal robe; is visited at the end of a lengthy tour of the palace by a gaggle of sight-seers; returns the champagne toast of some noblemen by raising a stein of beer; visits a zoo where a pelican eats his crown; takes the crown prince for an airing in an elaborate four-poster bed on wheels rather than a stroller or baby carriage; reviews the troops whereupon his arm gets stuck in a saluting position; slides down a bannister; goes dancing and gives his partner all the medals off his chest; dresses as an admiral for a cruise on one of his battleships and goes water skiing; visits a toy fair and plays with the toys; and meets another monarch with whom, upon arguing, he dons boxing gloves. By the end of the year’s run—the bannister episode, water skiing, playing with toys—the fundamental childlike personality of the Little King has emerged. But before sliding down the bannister, The Little King shows his diminutive majesty in adventures with simply incongruous conclusions that do not, in most instances, reveal his personality. The cartoon in which a busload of tourists visit the palace, successive panels show them ogling various rooms, including the royal kitchen and the royal bathroom with its royal tub, accompanied throughout by an elaborately gesturing tour guide. At the end, he brings them into the throne room and, with another elaborate gesture, shows them the King on his throne. Then they all depart, leaving the King alone on his throne. Such episodes do not necessarily puncture the grandeur of royalty. The operative spirit of the cartoon is not satire but playfulness. Down the scroll, we have a review of a new book reprinting vast stretches of The Little King. From IDW.

COMIC-CONNED Report on the DenverComic-Con and Elsewhere WE

ARE RAPIDLY APPROACHING—and perhaps are already deeply into—an era in which

every major American city has a comic-con, but the term “comic-con” seems

applicable only to the Comic-Con International in San Diego. And that

application of the term has become itself nearly meaningless. The themes adopted for the Sandy Eggo Con this year commemorate various anniversaries—Batman’s 75th, Daredevil’s 50th, Marvel Comics’ 75th, Usagi Yojimbo’s 30th, and Hellboy’s 20th. All comics milestones. But 2014 is also an anniversary year for many of the most historic, precedent-setting newspaper comic strips, some of which set the pace for comic book adventuring. With 80th anniversaries are Terry and the Pirates, Flash Gordon, Jungle Jim, Secret Agent X-9, Mandrake the Magician, and Li’l Abner; 90th anniversaries—Wash Tubbs (and Captain Easy, a model for Superman, who came along in 1929, 85 years ago) and Little Orphan Annie. And other 85th anniversaries are those of Buck Rogers and Tarzan—and Popeye in Thimble Theatre. But I’m willing to bet that you won’t find any program sessions in San Diego that recognize the signal contributions these comic strips made in the field that the Comic-Con is supposedly celebrating. Comics are not being celebrated some more at comic-cons in New York, Washington D.C., Chicago, Denver, Salt Lake City, Seattle, Portland, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Philadelphia, and, last I heard, Atlanta and Dallas and who knows where else Wizard World plans to invade? Wizard World, once a comics magazine publisher and now a pop culture convention chain, doubled its offerings to 16 cons this year, and its CEO, John Macaluso, says, “There is probably not a city in the country we are not looking at.” Wizard World has a tendency, according to Joel Warner at wired.com, “to enter a new city by scheduling its event right before a pre-existing con.” Said Steve Menzie, general manager of Fan Epo Canada in Toronoto: “They have a predatory model. They find somewhere that has a good show in a strong market and try to take it over.” Macaluso denies the accusation, saying Wizard World is merely an unwitting victim of the event schedules at city convention centers. But the scheduling conflict has been repeated with Wizard World’s debut in too many cities to be entirely accidental. Heidi MacDonald, comics editor at the Internet news site The Beat, estimates that there are 600-700 popular culture conventions being held around the world each year. Newspaper reports on comic-cons usually emphasize the colorful costumes on parade at these events but seldom mention comic books or comic strips. Or cartoonists. But the news articles are awash in the names of movie stars and other pop culture notables. At nytimes.com, George Gene Gustines observes the change: “Its name may emphasize comic books, but New York Comic-Con [scheduled for October] at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center also celebrates film, television and video games. ReedPop, which organizes the show, is making that appreciation of all things pop culture more official by declaring October 3-12 ‘New York Super Week,’ a citywide festival that will include gaming events, lectures, concerts, comedy shows and more.” Most of the new crop of comic-cons report record-breaking attendance year after successive year. The Denver Comic-Con, which I’ve attended since its inaugural three years ago, jumped from about 27,700 the first year to 61,000 the second and, this year, to 86,500. Comic-cons are apparently growing in popularity, but they’re also growing further and further away from the comics that inspired them.

Denver

Comic-Con. Official promotional materials for the DenComCon usually describe its programming as featuring comic books, tabletop and video games, anime, manga, cosplay (costumes), science fiction, webcomics, movies, television and literature. Comics are mentioned, but the emphasis has shifted—in Denver as well as everywhere else comic-cons are held—led by the San Diego extravaganza into the larger entertainment world. In

one respect, DenComCon has surpassed Sandy Eggo. I didn’t see any

horrendous around-the-block long lines to get through registration and

badge-pickup. Apparently, Denver has solved this persistent annoyance by

creating several pickup locations around the city. Otherwise, the Big Blue Bear

standing outside the Convention Center is still peering inside to catch a

glimpse of the proceedings. My daughter (a massage therapist and organic farmer’s wife by profession and an artist with a cartooning gene by accident and inclination) helped out at my table in Artists Alley (called “Artists Valley” in deference to the predominant peeks in these parts). It was her first comic-con, and when I asked her afterwards what she thought, she said it looked as if people were all having fun. And I agree: it’s a fun event, and fun-loving people come in droves to have fun. But there’s a slight downside, slight but perturbing. “It’s a casual crowd,” one of the comic shop exhibitors told me. “These are not comic collectors looking to complete their runs of particular titles.” Knowing this, he doesn’t bring to his exhibit booth any “high end” comic books—no collector treasures. As comic-cons drift away from comics and become bigger, they become businesses, and since businesses must make money, the cons are inherently competitive. And the more of them there are, the greater the competition and the bigger the financial risks. John Warner at wired.com interviewed Joe Parrington, Emerald City’s former PR director. Since Wizard World set up shop in Portland, Parrington says that for the first time, several celebrities booked at nearby Seattle’s Emerald City Con haven’t made enough selling autographs to meet their event guarantees, meaning the convention has had to pay them the difference. Warner wonders how independent non-chain conventions can stay afloat as the comic-con phenomenon turns from a convening of collectors to a gaggle of geeks, from a hobby to a business. One option, Parrington believes, is to turn professional, become a business in order to be competitive. “A lot of these conventions have fanboys and girls running their shows,” he says, “—they are not business people.” So the operation of a con could be turned over to professional convention management firms that are, perhaps, better equipped to compete with interlopers like Wizard World. But, says Warner, “some longtime convention organizers say there’s another option: Get back to basics. According to lead organizer Nick Postiglione, attendance at this year’s SpringCon in Minneapolis was up 25 percent despite Wizard World Minneapolis occurring two weeks earlier, plus SpringCon didn’t have trouble meeting celebrity autograph guarantees—since it doesn’t book celebrities.” “We are a comic con. We don’t do media guests,” Postiglione explains. “We are kind of purebred in that way. We are here to provide the comics industry opportunities to interface with the public. There is kind of a fight going on for the heart and soul of the whole thing. A lot of conventions have forgotten the girl who brought them to the dance, so to speak, which is the comic geek.” I suspect comic-cons have gone too far in the other direction: we can’t go back, however fondly we may wish to. Meanwhile, as the “con wars” are brewing beneath the glittery pop culture surfaces, comic-cons, now pop culture phenomena not collectors’ conclaves, are undeniably fun. No question. And here are some of my photos of the funsters.

(A couple of the accompanying photos salivate over Stan Yan’s zombie caricatures; he’s got a book of them that you can find at his website, http://stanyan.me/caricatures/zombicatures/201206catalog_frontcover/#main ) Augmenting my photos are excerpts from Tales from the Con, a comic book from Image. Written by Brad Guigar and drawn by Chris Giarrusso, the book offers single-panel comic-con gags sandwiched between comic strips of three or four panels, all taking fun potshots at the peculiarities and proclivities of the comic-con culture. Probably a better glimpse of the comic-con milieu and experience than my photos.

I

haven’t run across Giarrusso’s work before, but he’s been drawing comic books

since about 1999, when he created the Mini Marvels at Marvel, writing and

drawing dozens of crisply rendered comic strips and short stories for the

company. Displaying a deft and sure hand at cartoon comedy, he created a brand

new character for the Marvel Universe, Elephant Steve. These days, Giarrusso is

perhaps best known (everywhere, apparently, except here at Rancid Raves, where

we remain resolutely ignorant of many of the day’s most persistent fads) for

writing and drawing G-Man, an all-ages series featuring a young

superhero who gains the powers of super strength, super endurance, and flight

when he wears a magic cape; now available in two graphic novel volumes. Here’s

the way Giarrusso treats the traditional superhero realm. All of which ought to be sufficient come-on to get you to the San Diego Comic-Con, poised on the Left Coast to begin July 23, lasting over the ensuing weekend. I’ll be there, hanging out occasionally at the National Cartoonists Society booth (Thursday, 1-3pm; Friday, 5-7pm; Saturday, 5-7pm; and Sunday, 10am-Noon). I’m also on the program twice: once on Friday, 3-5pm, “Origins of the Comic Strip: The Untold Story of Artists and Anarchy, 1895-1915" (put together by Peter Maresca to celebrate his newest spectacular book of vintage newspaper comics, Society Is Nix; reviewed in Opus 315); and again on Sunday, Noon-1:30pm, “Strips and Pin-ups, Race and Politics” where I’ll be talking mostly about a pin-up, namely Bill Hume’s Babysan (see Harv’s Hindsight for September 2010). Hope to see you somewhere along the line.

QUIPS & QUOTES Helen Mirren on the social media: “It reminds me of a stinky old pub. In the corner would be this slightly disgusting old man who sits there all day, every day. If you went up and talked to him, you’d gt the kind of grumpy, horrible, moldy old meaningless crap that you read in Twitter.”

EDITOONERY The Mock in Democracy WAR,

HISTORIC AND CONTEMPORARY, was a preoccupation in June. A war of the past and

wars of the present. On June 6, the United States and its World War II allies

celebrated the 70th anniversary of D-Day, the day that changed the

course of the war in Europe, and editorial cartoonists also commemorated the

occasion. Starting at the upper left and going clockwise, Mike Streeter depicts the time-honored battlefield marker of a death in combat, and the words with which he accompanies the picture are ironic: D-Day made a difference in the history of the 20th century, but it also changed—by ending—the lives of thousands of soliders. Bob Englehart thinks of those who went ashore that day as supermen; and, indeed, in terms of their aspirations, they were. Bud Plante shows us from one of the hundreds of landing craft the view of the formidable beach before the invaders, a picture repeated by many of his colleagues (some of whom doubtless found exactly the view depicted here on the Web). Jeff Danziger deploys his D-Day image—soldiers wading ashore as seen from the beach—to take a poke at one of our sillier politicians. But I like best the stark image at the bottom of the page by a cartoonist whose name I failed to jot down. An empty, upside-down helmet. A somber reminder. As I watched the television reports of this year’s D-Day commemoration, I thought it less a celebration than an act of contrition—a gesture of apology from today’s officialdom for the decision of yesterday’s officials to send thousands of young men ashore in the face of withering German gunfire that would be certain death— certain death—for many. About 24,000 fought their way onto the beaches of Normandy that day; casualties numbered over 9,000, almost 4,200 were killed. One out of every six soldiers died. And so we stage periodic remembrances as a way of saying, We are profoundly sorry to have ordered you to die. While

on the subject of death, we contemplate with a growing sense of horror the

conduct of health care services for those soldiers who’ve managed to survive

the battlefields since D-Day. The Veterans Administration scandal grows apace,

a new shameful disgrace surfacing day-by-day. And finally, Mike Luckovich deploys the familiar looped ribbon symbol as a noose to suggest the fate that awaits so many of the vets who suffer from PTSD. With Chip Bok at the lower left, we change the subject to the Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision that permits corporations to evade some of their responsibilities under the Affordable Care Act. Citing religious beliefs, a business can opt out of supplying certain kinds of health care to its employees—in the Hobby Lobby case, four of the twenty mandated forms of contraception. The four in question are deemed by Hobby Lobby’s owners to be forms of abortion, and their religious belief is that abortion is murder. They understandably do not want to be accomplices in committing murder. Bok’s interpretation of the dilemma is not as straight-forward as it seems. The logic of the words seems irrefutable, but the “boss” carrying the corporate slogan is the Pointy-Haired Boss from Scott Adams’ Dilbert, a notoriously idiotic and uncomprehending character. By employing this image, Bok sabotages the logic of the sign the “boss” carries. Or does he? Some of his readers are doubtless of the pointy-haired persuasion, and they will applaud the boss’s sign. I don’t think Bok tried deliberately to have it both ways with this cartoon, but I think he got it that irregardless. Our

next exhibit continues to address the topic of the Supreme Court decision,

beginning with Rob Rogers, who has taken the Court’s claim that the

decision is a “narrow” one (i.e., not broadly applicable to all corporations in

all aspects of the Affordable Care Act’s mandates) and shows that, narrow or

not, the decision affects the well-being of women. At the lower right, Kevin Siers deploys the abstract fish symbol of Christianity to make his point: the Hobby Lobby decision is not a victory for religious freedom; instead, it makes it possible for employers to force their employees to behave in ways that the employer’s religion dictates. The large fish devours the smaller ones. And finally, John Darkow gives us a comically nightmare image fostered by the Supremes’ decision. An unforgettably rude image, surely, and one that every woman is haunted by, insulted by. This image gives real bite to the complaint of many women in the wake of the Supremes’ Hobby Lobby decision: they thought, with no little justification, that by the 21st century, we, as a society, had left hang-ups about abortion behind long ago. At least as long ago as the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. But it wasn’t just women’s rights that were put in jeopardy.

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM was dealt a serious if not fatal blow on June 30 when the Supreme Court found in favor of Hobby Lobby’s contention that it ought to be exempt from Obamacare’s contraception mandate because four of the 20 forms of contraception mandated are deemed forms of abortion, and abortion is contrary to the religious convictions of the evangelical Christian owners of the company, David and Barbara Green. The company was willing to offer 16 of the 20 mandated, but to offer the other four would offend the Greens’ consciences thereby threatening their religious freedom. Not true. The only real threat to liberty and religious freedom in this case takes the form of business owners who want to impose their religious beliefs upon thousands of employees. The Court’s ruling applies, they say, only to closely-held for-profit corporations. But according to Marci Hamilton of Yeshiva University—who apparently wants to raise a ruckus—more than 80 percent of U.S. corporations are closely held, and they could “now be able to discriminate against their employees.” Not quite true: all but 2 percent of those corporations employ fewer than 50 people and thereby evade the ACA mandate. In her dissent, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said the decision “discounts the disadvantages religious-based opt-outs impose on others, in particular, employees who do not share their employer’s religious beliefs.” Said the Denver Post editorially, the way is now open for companies whose owners object to blood transfusions, antidepressants, medications derived from pigs, vaccinations “and who knows what else” to demand waivers, too. While it is true that the Obama administration will doubtless find a way to provide contraception by other mechanisms, the larger issue pertains to the role of government in the religious lives of its citizens, which, with this decision, has seemingly altered enough to encourage the kinds of spectres the Post imagines. Not quite, as it turns out, but enough to give us pause. Despite the obvious implications for the religious freedom, the Hobby Lobby decision was not based upon the First Amendment. The justices, in fact, seemed determined to avoid the First Amendment. They based their decision upon the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. This law was intended to address certain inequities that had surfaced when a couple of Native Americans were fired and denied unemployment benefits because they used peyote as part of their religious ceremony. Peyote, tagged a drug, was illegal in the state’s law, hence the culprits lost in court, which held that state law trumps their religious practice. The RFRA was passed in order to correct this situation. The applicable part of the RFRA requires governments to refrain from limiting (or “burdening”) religious freedom unless they have a compelling societal reason for doing so; and to select the least intrusive method to achieve their goal if they need to restrict religious freedom for a compelling reason. The Supremes felt that the government had a compelling reason for the ACA contraception mandate but that there are less intrusive means of achieving the law’s objectives. In fact, as one of the justices pointed out in his decision, the Obama administration has already put such a less intrusive means into practice by letting non-profit enterprises opt out of the contraception mandate and requiring insurance companies to cover the cost. This means of excepting compliance could be applied, saith the justices, to for-profit entities. According to the Rancid Raves legal advisory council (my daughter is a lawyer), if the RFRA did not exist, the Supremes might have been forced to ponder the case in the context of the First Amendment, and the outcome might have been different. The RFRA might be considered unconstitutional itself. In fact, in a 1997 case, it was so deemed if applied to state governments; it is apparently still regarded as constitutional for federal cases, which the Hobby Lobby case was. But the whole proposition is on shaky ground, it seems to me: it looks suspiciously like making a law about religion. The First Amendment in prohibiting Congress from making any law “respecting the establishment of religion” was not only guaranteeing “the free exercise” of citizens’ religious beliefs, it was also strenuously preventing the establishment of a state religion. The Hobby Lobby victory in this case effectively establishes a state religion—that is, a governmental mechanism that can force citizens to live by religious beliefs not their own. The way out of this dilemma is supplied by Christ himself in a maxim apparently overlooked by the strenuously religious who seek to impose their beliefs upon others. “Give unto Caesar what is Caesar’s,” Christ said when asked about paying taxes to Rome. From this admonishment, we can derive the principle that since we live secular as well as sectarian lives, we must therefore find ways to live in both, in the sectarian as well as the secular world—the latter, the world the founding fathers sought to establish with the First Amendment—which we do by giving in to secular requirements now and again, giving to Caesar. Incidentally, the Greens’ assault on the ACA contraception mandate is only one part of a much larger plan to inflict their religion on the nation as a whole. Reports Time: “The Greens are beta testing a high-tech Bible-study curriculum for public schools this September in an Oklahoma district. They hope to see it adopted in thousands more districts within three years. A draft copy suggests it will be a wonderland of technological pedagogy but will raise church-state issues that could end up before the high court.” They ain’t done yet making good Christians of us all.

GUNS

AND THEIR CAPACITY TO KILL were in the news again in June. As time goes

by and we endure mass murder after mass murder, we have become inured to

bloodshed. Apart from the initial expressions of outrage and grief at each new

outburst, we take no more notice than we do of deaths on the highway, and Tom

Toles in our next visual aid has found a perfect and memorable way to

assert this sad fact. Next around the clock, Dave Horsey goes to another extreme, a comedic one, intending to ridicule the National Rambo Association for its ceaseless and unquestioning allegiance to “America’s True Religion.” If we can’t beat them (and we apparently can’t), perhaps we can laugh them out of existence. (Oh, sure: dream on.) Despite what the NRA would have us believe about the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun being a good guy with a gun, it ain’t true. And we have a recent example to cite, namely John Wilcox, a good guy who was armed when Jerad and Amanda Miller, brandishing weapons, rushed into a Walmart where Wilcox was moments after they’d killed two police officers. Wilcox, a dutiful good guy, pulled out his legally concealed weapon and moved toward Jared, only to be shot and killed from behind by Amanda. In Hollywood, Wilcox would have triumphed. In real life, not so much. A 2009 study by the University of Pennsylvania found that assault victims carrying firearms were 4.5 times more likely to be shot than those who were unarmed. Another statistic to refute the claims of the NRA: in states where background checks on all gun sales are in place, there are 39 percent fewer law enforcement officers killed by individuals armed with handguns compared to those states that allow some gun sales to go unchecked. Meanwhile, the bodies pile up. Slate reports that since the 2012 mass murder at the Newtown school, at least 9,901 gun deaths have been reported in the U.S. But that’s a low number: it doesn’t count suicides, which make up about 60 percent of the likely actual number of gun deaths in America. But they are only rarely reported. A more accurate tally, then, of people killed by guns—some 28,600, according to an estimate by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. More guns, as the NRA prescribes, will not solve the problem. In fact, the ready availability of guns is a huge part of the problem. Here’s Mark Morford in SFGate.com: Deeply embedded in the American psyche is a fetishized worship of firearms—the icon of “bogus virility.” In the 70-plus mass killings over the last three decades, every perpetrator has decided that the only way to prove he’s a man, to get back at women, the boss, the world, “is to buy a firearm and start shooting.” Until American men realize that relying on a gun makes you less of a man and that authentic masculinity doesn’t involve violence, we face even “more unimaginable pain, and nearly all of it at the hands of men.” It’s a cultural problem, and carrying a weapon is part of the masculine pose. Mike Luckovich revives the lasting image of Tiananmen Square in 1989 China to characterize “open carry” as overt intimidation—to which Starbucks and Target and other retail operators have assented so far as to discourage customers from wearing weapons when then enter their stores. At the lower left, Gary Varvel changes the subject to the Supreme Court’s decision about Obama’s ability to make appointments during Senate recesses. The image effectively catches Obama’s seemingly imperial aspirations by portraying him in a king’s costume, and Varvel provokes a laugh, too, by showing the king’s cloak getting hung up by the Supreme Court. In the context of Bronco Bama’s everlasting struggle with a thoroughly recalcitrant (not to say obstructive; but then, I usually do say it) Congress, his resorting to recess appointments seems appropriate. Besides, the Senate’s claim that it was in session, not in recess, because one senator showed up every three days to gavel a non-present body of lawmakers into order (and then promptly gavel an adjournment) is clearly a dodge intended to prevent the President from making appointments during what anyone else would call a recess. For much the same reason, I find Obama’s alleged expansion of executive power wholly understandable. Even appropriate. Obama, I hasten to point out, was elected and then re-elected, both times by more than 50 percent of the voters (a percentage no president of recent vintage has recorded); no member of Congress can claim any electoral victory even close to that. Obama, then, would seem to be a more accurate reflection of the population’s wishes than anyone in Congress; Obama would not have been elected let alone re-elected were this not the case. So Obama more accurately reflects the wishes and inclinations of the American public than any member of Congress, who, by diligent pandering, represents only the biases of his district, a minuscule population compared to the nation’s as a whole. But then, I’m not a Republicon, and I can’t even think like they do.

OUR

NEXT EXHIBIT contains several examples of the Grandstanding Obstructionist

Pachyderm’s so-called “thinking”—the stuff of real comedy. The strategy is transparently to manufacture some seemingly scandalous but overlooked aspect of everything Obama does or proposes and to build that faux criticism into a thunderous chorus, overwhelming with distraction the actual matter being considered. Exactly what happened when Obama asked Congress for $3.7 billion to begin to address the crisis on our southern border of unaccompanied children invading the country in droves by the thousand. The first thing GOP Senator John Cornyn of Texas said was: “If it’s serious enough for him to send a $3.7 billion funding request to us, I would think it would be serious enough for him to take a hour of his time on Air Force One to go down and see for himself what the conditions are. I think it would be instructive for him.” No doubt. But wouldn’t it be instructive for Cornyn too? Sorry: that’s playing their distraction game. There’s no denying the crisis exists, and for the GOP to cobble up a criticism of Obama instead of attempting to address the problem is malfeasance of the first order. And subsequent attempts to blame the flood of illegal child immigrants on Obama’s policy of deferring action on undocumented young people assert that this policy invites them to come. But the law that makes possible a child’s attempt to successfully infiltrate American society was a law signed by GeeDubya Bush at the end of his presidency—a law that established a lengthy legal process in order to prevent sex trafficking. The length of the process makes it possible for a child to elude the long arm of the law by disappearing during the proceedings into the bosom of a family of relatives already here. But let’s not make the mistake of expecting rational thought processes from politicians. (Actually, we don’t have politicians anymore: we have panderers seeking everlasting re-election.) Horsey is with us again at the lower right with helpful congeries of insight into the so-called Republicon mind. To caption the scene a “fishing expedition” implies that the fishermen have no discernible purpose—but they hope to “catch” something by fishing the pond. The pond here is a mudflat with no water to keep the boat afloat. Labeling the mudflat “Benghazi” effectively points us towards the House’s latest investigation of the event, which hopes (against hope, given how often it has failed in the past) to find “something” to hang Hillary with. (You know about Hillary, right? She’s the evil genius who masterminded the most elaborate cover-up in U.S. history and is also a frail old woman with brain damage. Boy, those Pachyderms must have fascinating nightmares.) The fishermen are the GOP, Fox News and the Tea Party. And Fox gives us the rationale for the entire enterprise. (And he might’ve added—“and that will keep the viewers coming back for more of the same.”) Nick Anderson takes another tack at the lower left, depicting the cruel irony of the GOP’s hysteria over the deaths of four Americans in Benghazi compared to the death of thousands in the war that Dick Cheney invented—about which no Republicon has yet expressed equivalent outrage. In

our next display, the GOP continues in much the same headlong fashion over

Obama’s trading five Guantanamo prisoners for one American soldier, Sgt. Bowe

Bergdahl, who’d been a prisoner in Afghanistan for five years. At the lower right, Jim Morin takes up another hypocrisy of the GOP, deploying a revealing image to depict the party’s “outreach” to minority voters. And finally, Dan Wassserman reveals just how convoluted Republicon reasoning is, jumping from one cause celebre to another and linking them in a grand crescendo of finger-pointing so feverish and nonsensical that it reveals the hollow desperation of the pack of Pachyderms in Congress. More

evidence of the Pachyderm panic ensues in our next visual aid. Boehner’s latest grab at headlines is his scheme to sue the President for failure to faithfully execute the laws Congress has passed. This from a Congress that has failed to govern. The Speaker’s maneuver is, as Obama correctly points out, “a stunt.” The Constitutional remedy for an elected official’s failure to do his job is impeachment. But Boehner knows that (1) he hasn’t the votes to impeach and (2) even if he had, the last time the GOP impeached a president, the president’s popularity soared (Clinton, remember?). So he resorts to this shred of theatrical fraud. So hideously ludicrous (except among the Tea Party base, no baser a group in politics known) is this maneuver that Mike Luckovich nails it at the upper right: Boehner’s next stunt will be that whoopie cushion he’s putting on the chair. But enough Washington nonsense. Next around the clock, we have a cartoon by Dutch cartoonist Tom Janssen, who’s been doing this kind of work since 1976. His image deftly captures part of the Ukrainian problem: Ukraine may want to join the European Union, but the red carpet the EU has rolled out for it lacks any kind of substantial support. Then we have John Darkow’s adaptation of Delacroix’s famous painting “Liberty Leading the People”— all for the sake of a joke at the expense of the Russian bare, Putin. But the joke has a point: Darkow’s Putin hopes to ridicule the Ukranian revolution out of existence. And if he does, Liberty will lose.

THE

APPALLING SITUATION IN IRAQ is the next subject of editoon attention. A funny picture, as I said, but it has a sharp edge, too, making a point about Halliburton’s war profiteering. Pat Bagley’s next, and he conjures up a similarly laughable portrait of Obama’s predecessor, who, having rubbed the neo-con magic lantern, finds that it has summoned up horrors he never anticipated. So he runs away, carrying his paint brushes. Jimmy Margulies offers a nicely ironic analysis of the Iraqi situation: just as help for Iraq depends upon somehow unifying the feuding sects of Islam, so does the functioning of America depend upon somehow joining together in common purpose the polar opposites in today’s politics. Then Steve Breen at the lower left provides a dynamite metaphor for the explosive situation in Iraq that finds the U.S. sharing an interest with Iran in suppressing the Iraqi revolt. The

revolt itself and the ISIS that has provoked it fall victim to editoonists’

analysis in the next display. Next on the clock is another of Jeff Danziger’s. Without any particularly compelling imagery, he accurately states the case: ISIS is able to achieve its objectives because it is armed by the United States, which had supplied weapons to the Iraqi forces that left them all behind when they fled. Hence, the folly of our sending arms to forces we only vaguely understand—in Syria, for example. The last cartoon in this exhibit is by another Dutch cartoonist, Joep Bertrams, who characterizes the ISIS movement as snorting caliphate, a nasty but vivid metaphor. We

go to Gaza for the next collection of war cartoons. To be fair, however, the Israelis often telephone civilians housed in their targets, warning them to leave the premises or risk being bombed. The present warfare was prompted, as best I can sort out, by the killing (burning alive) of a Palestinian teenager by some Israeli youths; that, in turn, was revenge for the Palestinians’ kidnaping three Israelis and killing them. And on it goes. But the reactions in Israel and in Palestine to the killings are strikingly different. According to report, the Israelis are much more humane. The uncle of one of the slain Israeli boys went to the home of the slain Palestinian boy to offer his condolences. And Netanyahu phoned the Palestinian boy’s father, calling the killing “abhorrent” and saying that whoever murdered the youth “must be resolutely condemned in the most forceful language.” Netanyahu also referred to the killing as shameful. And Israeli security forces tracked down and arrested at least one of the suspects in the killing of the Palestinian kid. But, as columnist Greg Dobbs said on July 8 in the Denver Post, “have you read a single word of condemnation from the Palestinian side about the abominable murders of the three Israeli teenagers?” No. And we haven’t heard anything about how diligently the Palestinian police have been in looking for the murderers of the Israeli kids. And even if those killers are caught, Dobbs avers, they’ll doubtless be praised as martyrs among their people. I’m quite willing to allow that Israel routinely enjoys favored treatment in the American news media. In fact, if you judge by news reports alone, all the Israelis are saints (assuming Jews have saints) and never are at fault. From the beginning, the Palestinians have been the villains and the Israelis, the victimized heroes. And maybe Dobbs is another of Israel’s secret journalistic agents. But other sources tell us that the official Israeli policy with regard to bombing for terrorists in civilian enclaves is to issue warnings that bombs are about to fall. And Jonathan Tobin in CommentaryMagazine.com reports that “Palestinians openly celebrated the death of the Israeli kidnapping victims” while Israelis “largely condemned the revenge killing” of the Palestinian youth. The humanity I’ve alleged in the foregoing paragraphs cannot all be propagandist hogwash. Can it? Maybe it can. But how are we to know? At the very least, the Palestinians need better public relations. Yaakov Kirschen, whose Dry Bones strip is next on the clock, is an Israeli cartoonist, so his perspective is predictable. But it’s also worth pondering. Ed Gamble, an American ediltoonist who supplies the next cartoon in our sequence, is, as far as I know, neither Palestinian nor Israeli—although his sympathies, like those of most Americans, have been nudged to lean toward the Israelis. Moreover, working at the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville, he is in a state with a vibrant Jewish population whose interests he is likely to be conscious of. In his cartoon, he shows Hamas hiding behind women and children and then accusing the Israelis of attacking women and children. The image is blunt. But if Israelis seek to kill Hamas agents in crowded Gaza, aren’t they likely to hit civilians and women and children? Maybe Hamas is not, exactly, using women and children as shields, but the effect is the same as if they were. There are no answers here in these cartoons. The Israelis and the Palestinians have been at each other’s throats for so long that assigning blame one way or the other is an impossible task. The animosity goes back further than the United Nations partition resolution of 1947, the immediate cause of the war between Jews and Arabs that resulted in the Arabs being driven from their homes in what was quickly proclaimed Israel. Ironies abound. The UN plan called for the creation of two states. The Jews accepted the plan; the Arabs rejected it, seeing the Jews as interlopers in Arab precincts. The ensuing war settled the issue for the moment—but perpetrated the animosity that continues to plague both populations. And now, for the last dozen or so years, both parties have agreed to a “two state solution”—exactly what the UN proposed 67 years ago. And so it goes. The ridiculousness of Brady’s Netanyahu urging Israeli troops to try not to kill civilians, while seeming to indict Israel, actually implies also the opposite. Upon this contradictory circumstance—which haunts all of that region—I’ll leave this discussion, as incapable of resolution as ever. But if you wish to examine some of the sources of the modern effusion of ethnic animosity in that region of the world, you may want to visit Opus 190 and scroll down towards the end, where I attempt a version of the history of the area by way of sorting out the hatreds and their probable causes.

FROM GAZA, WE ROTATE TO ANOTHER BORDER, ours with Mexico. Mike Keefe uses the crisis at the border to comment on violence abroad and at home. His image serves a narrative rather than symbolic purpose, but his message is bitterly accurate. And Joe Heller, at the lower left, tells us the cause of the predicament we now face. And we’ll continue to face it, I suppose, because Congress is more concerned about assigning blame than about fixing problems. Sad—even criminal—but true. One

last visual aid—this one, prolonging the indictment of our do-nothing Congress. John Cole just below Ohman’s strip says the same thing, but adds the complication that results from comparing Obama’s handful of jokes with various punchlines to Boehner’s single issue gag. And so, gagging all the way, we ponder the last of our visual aids this time—Mike Davies’ deft indictment of Republicon opposition to immigrants “stealing jobs from American workers”: the GOP, friend to business everywhere, is too myopically hypocritical to see that the business practices that it implicitly endorses explicitly do the same thing that the Grandstanding Obstructionist Pachyderm condemns in immigrants. Gagging all the way.

READ AND RELISH Thoughts by Charley Barsotti—: Someday I’m going to write a “How to Be a Cartoonist” book. It won’t have anything to say about drawing but will tell you how to dress casually without being picked up as a bum. I will reveal the true history of cartooning from the earliest times when cartoonists drew on air. This was known as the Golden Age because no one could prove the drawings weren’t as funny as the artists claimed they were. Eventually, of course, editors came along and messed things up by passing gas through the air cartoons. Since then, things haven’t changed that much. I will also include a few of the hard truths I’ve learned about the business over the years. For example: Talent is okay, but denial is critical. It’s been written that creative work is the hardest work of all. It goes without saying that this was written by artists, not ditchdiggers. And if you don’t know who Charley Barsotti is, skip to the Passin’ Through Department down the scroll.

RANCID RAVES GALLERY Pictures Without Too Many Words Marvel

Comics has devised a logo to promote its celebration of 75 years in the

business. Very attractive, don’t you think?

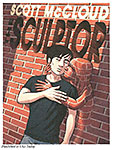

AND,

SPEAKING OF SPECTACULAR DRAWING, here’s the cover for Scott McCloud’s new book, The Sculptor. David, the eponymous hero of the piece, makes a

deal with the Death to be remembered by posterity but then he falls in love.

The cover had to communicate three things, said McCloud to USA Today,

which published the art: the supernatural way David shapes the world around

him, the love story that forms the book’s emotional center, and their

surroundings in New York Whatever else the picture may be, in its treatment of Meg as part of the brickwork, it is an outstanding example of McCloud’s command of his medium. Dang: the man is good, better than ever. And he was no slouch to begin with.

PERSIFLAGE AND FURBELOWS “I’m one of those people who’s not really turned on by baseball. My idea of a relief pitcher is one that’s filled with martinis.”—Dean Martin “Good pitching will beat good hitting any time—and vice versa.”—Bob Veale “Baseball is accused of being too slow. Here’s something that would not only speed up the game but also provide a welcome opportunity for serious injuries. Like most good ideas, it’s uncomplicated: if the pitcher hits the batter with the fall, the batter is out. That’s it. A simple idea but it would make quite a difference.”—George Carlin

NEWSPAPER COMICS PAGE VIGIL The Bump and Grind of Daily Stripping

Strange

and Sometimes Risque Stuff in the Funnies. In this Sunday Zits, I noticed

that Jeremy has no feet. Sara does; but not Jeremy. It cannot (can it?) be mere coincidence that the signatures of Greg (who inks) and Mort (who pencils) Walker appear where they do in this Beetle Bailey. They’re just over—on the very cusp of going in—the bowl Beetle holds. And Cookie says acorns (nuts) keep failing into the cereal (bowl). That makes Greg and Mort the nuts, right? In Darby Conley’s Get Fuzzy, Satchel confesses to an urge that once couldn’t be mentioned in the comics. Mores change, as we’ve noted here from time to time: what was once verboten is now permitted. But I bet if the mutt had said “piss,” it wouldn’t have escaped the censor’s scalpel. And speaking of the forbidden, we have a single panel cartoon depicting a wedding cake on which those little groom and bride figurines have impulsively cast their clothing aside in order to enact the wedding day’s customary concluding ritual right there, on top of the cake. Can’t read the name of the cartoonist, though; sorry. (Ham?) Finally, Crankshaft is getting an idea in Tom Batiuk and Chuck Ayer’s strip of the same name. But I doubt that this is the first time the cartoon symbol of having an idea has confronted the change from bulb to corkscrew shape.

More

Sex in the Funnies. In Greg Evans’ Luann, Tiffany, the strip’s self-proclaimed

gorgeous sex symbol, suggests that she’s not wearing any underpants. Pretty daring

stuff even for today’s funnies page where all other manner of sexual innuendo

is transpiring.

It

Must Be Contagious. Nothing earth-quaking: no taboos being broken; no sexual innuendo being

exploited. Just cartoon skylarking in the funnies. In Beetle Bailey, Mort

and Greg Walker continue to exploit the comedy inherent in their joint

signature. And now, Blondie joins the ranks of comic strips doing cross-overs—or, rather, drafting characters from other strips to do cameos. Characters from other strips visited Blondie over a 2-3 month celebration of the strip’s 75th anniversary in the summer of 2005, but that was a special occasion. The cameo in the strip at hand is without any justification other than comedic effect. Justification enough, but, as with similar guest appearances in other strips, the risk is that the strip furnishing the cameo may not run in the same paper. Hasn't stopped anyone yet, but you'll notice that the cameos all come from top circulation strips. Where will it all end? Who knows? Certainly not Stephan Pastis, who’s made a specialty of importing into his strip the characters of others. This time in Pearls Before Swine, however, he resorts to another of his tried-and-awful word play productions. This one is so wonderfully awful that I saw it coming in the first panel. As soon as I read “Juan,” I knew that “futon” would somehow wind up in the penultimate punchline. And it did. But the actual punchline, in the last panel, is as wonderful a pun as any other Pastis has perpetrated.

CIVILIZATION’S LAST OUTPOST One of a kind beats everything. —Dennis Miller adv. “Amanda Blackhorse, a Navajo who successfully moved a federal agency to withdraw trademark protections from the Washington Redskins because it considers the team’s name derogatory, lives on a reservation where Navajos root for the Red Mesa High School Redskins.”—George F. Will In the Denver Post, a retired newspaper editor, Dick Hilker, ranted on in the same vein, reporting that the school board in LaVeta, Colorado, voted 3-2 to keep the Redskins as the high school’s mascot. “The Political Korectness Kops are so inane with much of their never-eneidng outrage over school mascots and various words and phrases (see “sissies”) that it is enjoyable when someone tells them ‘enough.’ “If Redskins are obliterated, where does the PKK strike next, Chippewas? I can’t figure it out. For instance: “Why is it perfectly fine for Florida State to be the Seminoles and Utah to be the Utes, but not okay for the University of North Dakota to be the Sioux? Why is it noble to name teams Vikings, Prospectors, Miners, Azltecs, Spartans, Trojans and Irish but not Indians? If no teams were named for Native Americans, would the PKK then be equally steamed and demand to know why the nation’s early settlers are being discriminated against? Likely so.” But then Hilker makes his best point: “We should assume that intentions are the highest when school nicknames and mascots are chosen. Ironically, LaVeta was once known as the Cowboys before adopting Redskins. No teams are named Wimps, Weasels, Nazis, Thieves or Hornswogglers.” But we forget such things.

BOOK REVIEWS Long Critiques

Cartoon Monarch: Otto Soglow & The Little King Edited by Dean Mullaney, Introduction by Jared Gardner, Foreword by Ivan Brunetti 428 7.5x9-inch landscape pages, b/w plus 95 in color; 2012 IDW hardcover, $49.99 SOGLOW’S FAMOUSLY silent pint-sized red-robed monarch is given an ample display case with this volume, another exemplary IDW production (including the now-familiar sewed-in ribbon bookmark), generously reproducing one strip per page and scrupulously dating them all. The color reprint section begins with The Little King’s predecessor, The Ambassador, and continues with a selection of strips from the first Little King syndicated (September 9, 1934) through the 41-year reign, samples from every year—all in black-and-white except for the first 95 pages. Also represented are examples of Sentinel Louie, topper to The Little King, and samples of Soglow’s early “ashcan school” cartoons, about as far from his characteristic minimalism as possible. In his brief Foreword, Brunetti appreciates Soglow’s artistry, analyzing one strip featuring a long phallic automobile that emphasizes the King’s interest in a female jogger. Gardner’s Introduction is a much more ambitious undertaking: a copiously researched essay, it offers without question the most complete biography of Soglow available (except perhaps the one we posted lately in Harv’s Hindsight —but it poached a lot from Gardner’s). Very little has been written about Soglow and his Little King, so the detail Gardner has been able to uncover is impressive. In the absence of actual biographical material, Gardner has resorted in a few instances to deducing facets of Soglow’s life from the milieu in which he moved. An entirely acceptable practice, it occasionally leads to mildly misleading assumptions. Yorkville, the Upper East Side of Manhattan where Soglow grew up, is not the same impoverished and crowded kind of neighborhood that the Lower East Side was in the early years of the 20th century; Soglow’s early left-leaning political views speak of an urban population, not a slum population, even though Gardner sometimes seems to suggest that the German Jewish ethnicity of parts of Yorkville implies otherwise. But to quibble over such a teensy blemish risks overlooking Gardner’s persuasive achievement in mustering biographical meaning from episodes in Soglow’s life—his leftish instructors at the Art Students League, for instance, “ashcan school” artists like John Sloan and Robert Henri. Gardner has also assembled an authoritative gallery of non-monarchical Soglow art—book covers and illustrations (Soglow drew pictures for over 30 books), advertising illos, spot drawings, photographs, and several of the early Little King cartoons (alas, undated) from The New Yorker, where the character debuted. Soglow’s mastery of pantomime and minimalist visuals in cartooning is the most significant aspect of his long career, and while I don’t see Soglow as defining the “post-war style and sensibility” of the form in quite the pace-setting way that Gardner does, this book—the reprinted Little King strips and Gardner’s essay—is a worthy monument to the cartoonist’s distinctive style and unmatched achievement.

BEEFS & BOFFOS FROM HARPERS: Percentage of Americans in 1992 who believed gun laws should be stricter: 78 Percentage who believe so today: 43 Percentage of U.S. government contracts intended for small business that went to large corporations in 2011: 37 Percentage of U.S. veterans from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan seeking disability: 45 Percentage of African countries in which it is illegal to practice homosexuality: 69 Number of college graduates currently working as astronomers, physicists, chemists, mathematicians, or web developers: 216,000 As waiters and bartenders: 216,000 Percentage of American households made up of just one person in 1950: 93 Today: 27 Chances a Republican believes today that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction at the time of the 2003 invasion: 2 in 3. Average number of times each week U.S. surgeons operate on the wrong patient or body part: 40

COLLECTORS’ CORNICHE Welcome to our sentimental section where I muse and marvel about antique volumes on the shelf and rare finds in old bookstores and the like. Nothing major. Skip over this if you’re busy.

THE TELL-TALE SYMMETRY of these two Carl Barks self-portraits smote me in the eye, so I thought you'd like to see them together, too. Although for the sake of poetry, I’d like to think they were drawn years apart—and in chronological order—various comments on this pair of drawings suggest they were actually drawn at almost the same time, give or take a year either way.

ANDY ROONEY ON SEX When I was born, I was given a choice—a big pecker or a good memory. I don’t remember what I chose. A wife is a sex object. Every time you ask for sex, she objects. Impotence: nature’s way of saying, “No hard feelings...” There are only two four letter words that are offensive to men: “don’t” and “stop,” unless they are used together.

FUNNYBOOK FAN FARE Four-color Frolics An admirable first issue must, above all else, contain such matter as will compel a reader to buy the second issue. At the same time, while provoking curiosity through mysteriousness, a good first issue must avoid being so mysterious as to be cryptic or incomprehensible. And, thirdly, it should introduce the title’s principals, preferably in a way that makes us care about them. Fourth, a first issue should include a complete “episode”—that is, something should happen, a crisis of some kind, which is resolved by the end of the issue, without, at the same time, detracting from the cliffhanger aspect of the effort that will compel us to buy the next issue.